Kafka’s Ape Meets the Natyashastra

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. The Work’s Inception

3. The Work’s Development

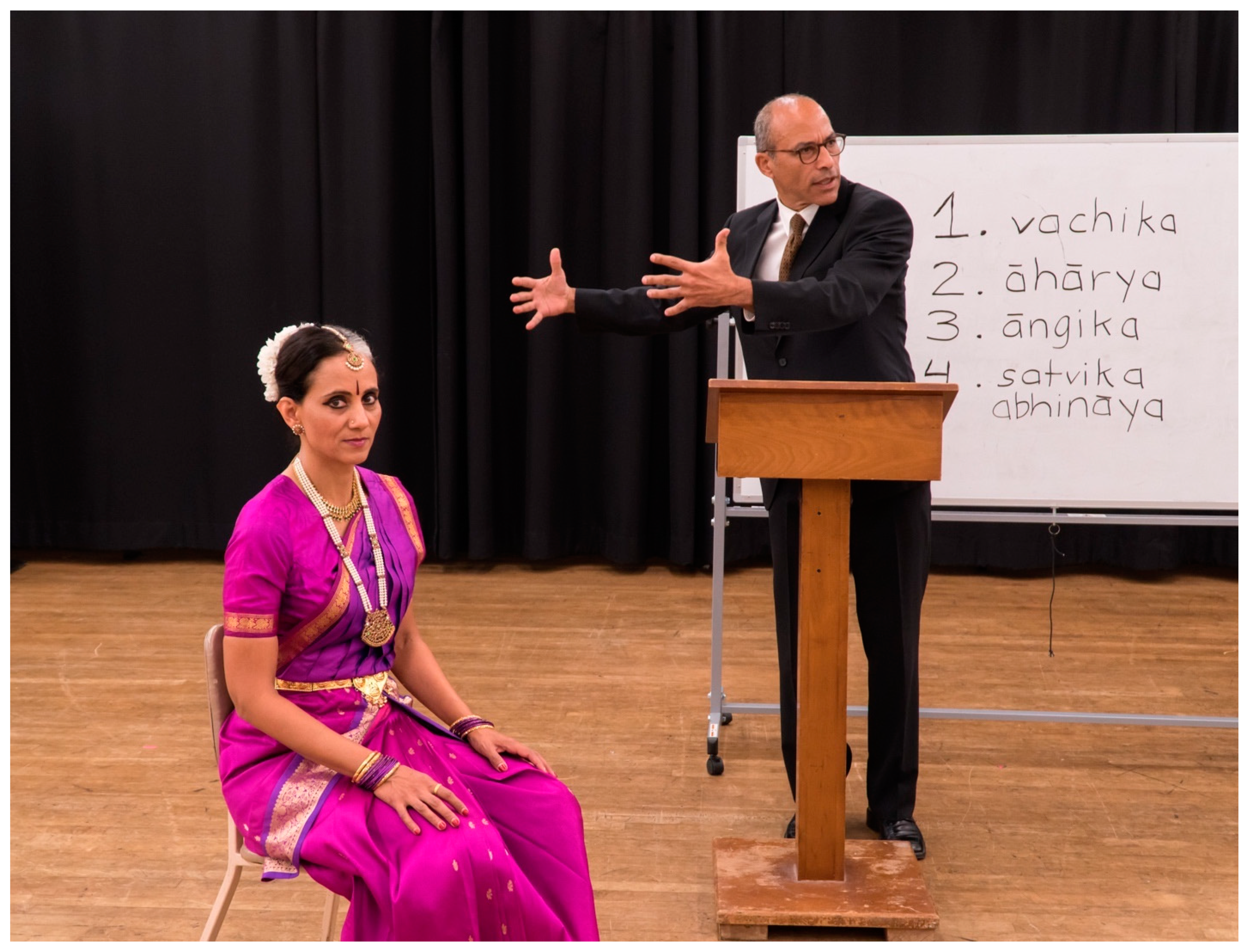

4. The Indian Dancer

The fact that a public debate about caste exclusion in the dance world has been kickstarted only very recently—largely due to hereditary practitioner Nritya Pillai’s cogent interventions into the performance arena and on digital platforms—is proof of the fact that dance continues to be disputed territory as well as a site for irreconcilable visions of the nation and citizenship (Johar 2016; Kedhar 2020; Morcom 2013; O’Shea 2007; Pillai 2020, 2022; Soneji 2011; UCLA Center for India and South Asia 2021; UCR Department of Dance 2022).The body of the Indian classical dancer is always an emblem and a problem. As an emblem, it signifies the wonders of an Indian cultural heritage. And as a problem, it signifies the wonders of an Indian cultural heritage. Inescapably, the dancing body reveals that its gift and promise is also its ballast and burden.

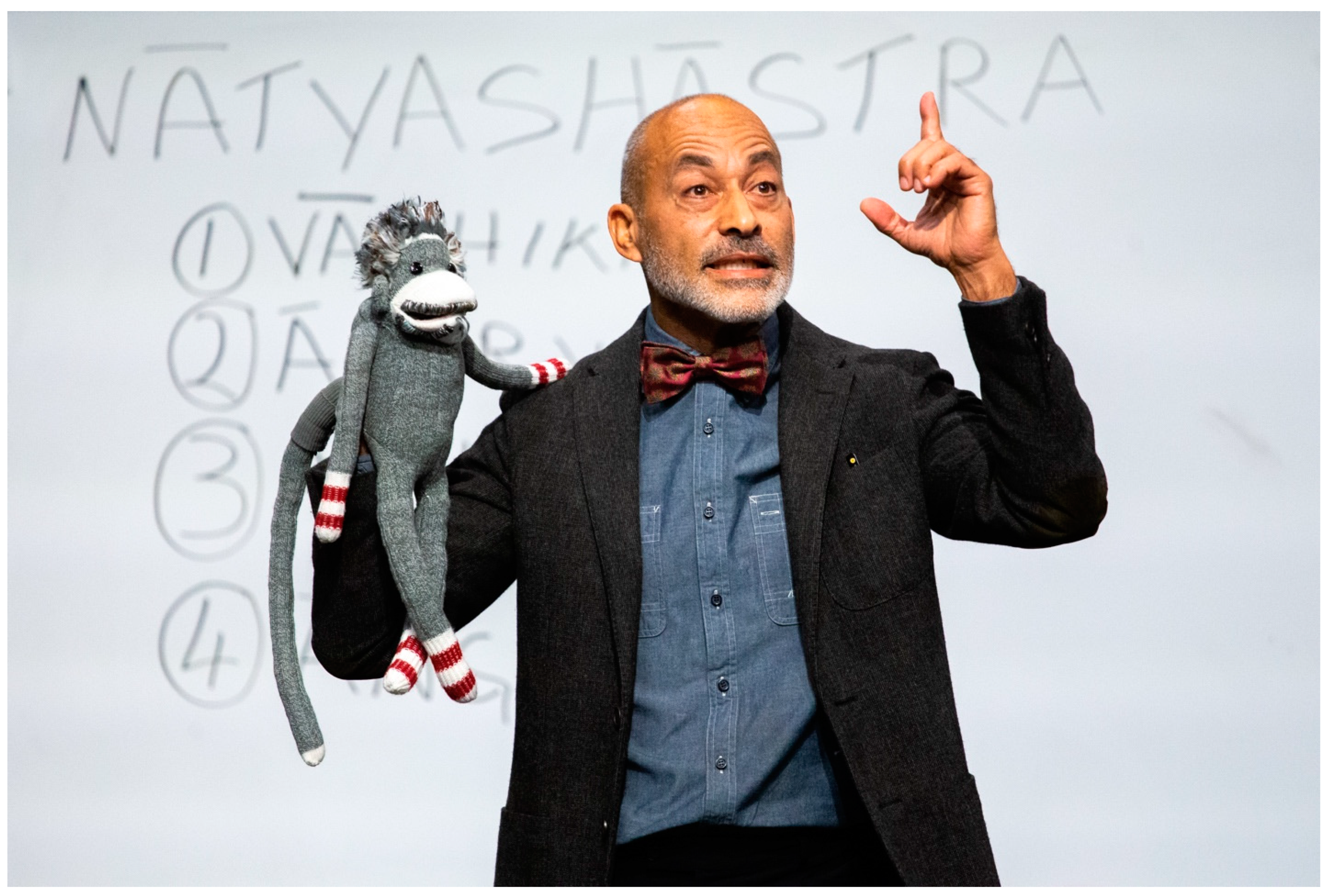

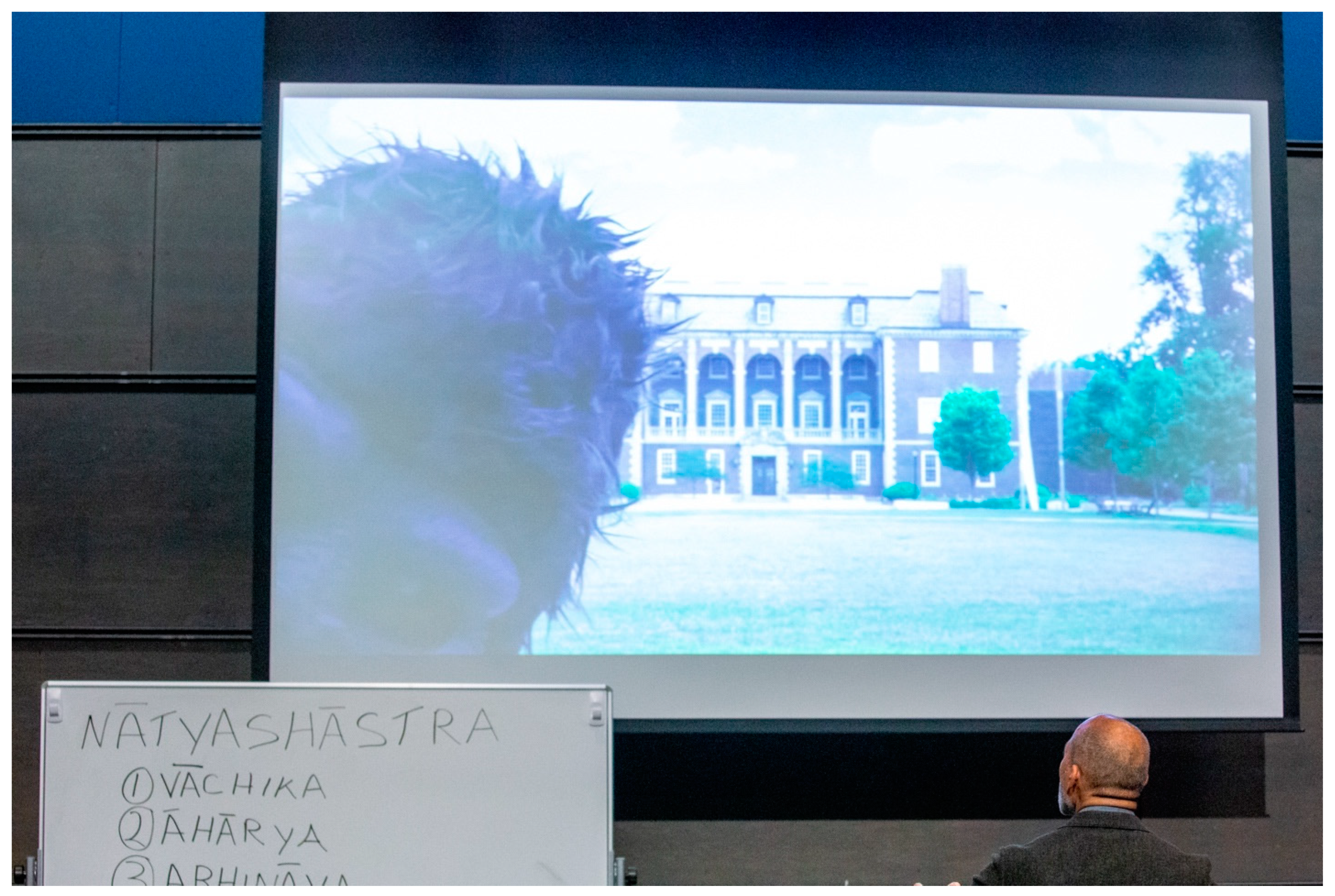

5. Referencing the Natyashastra

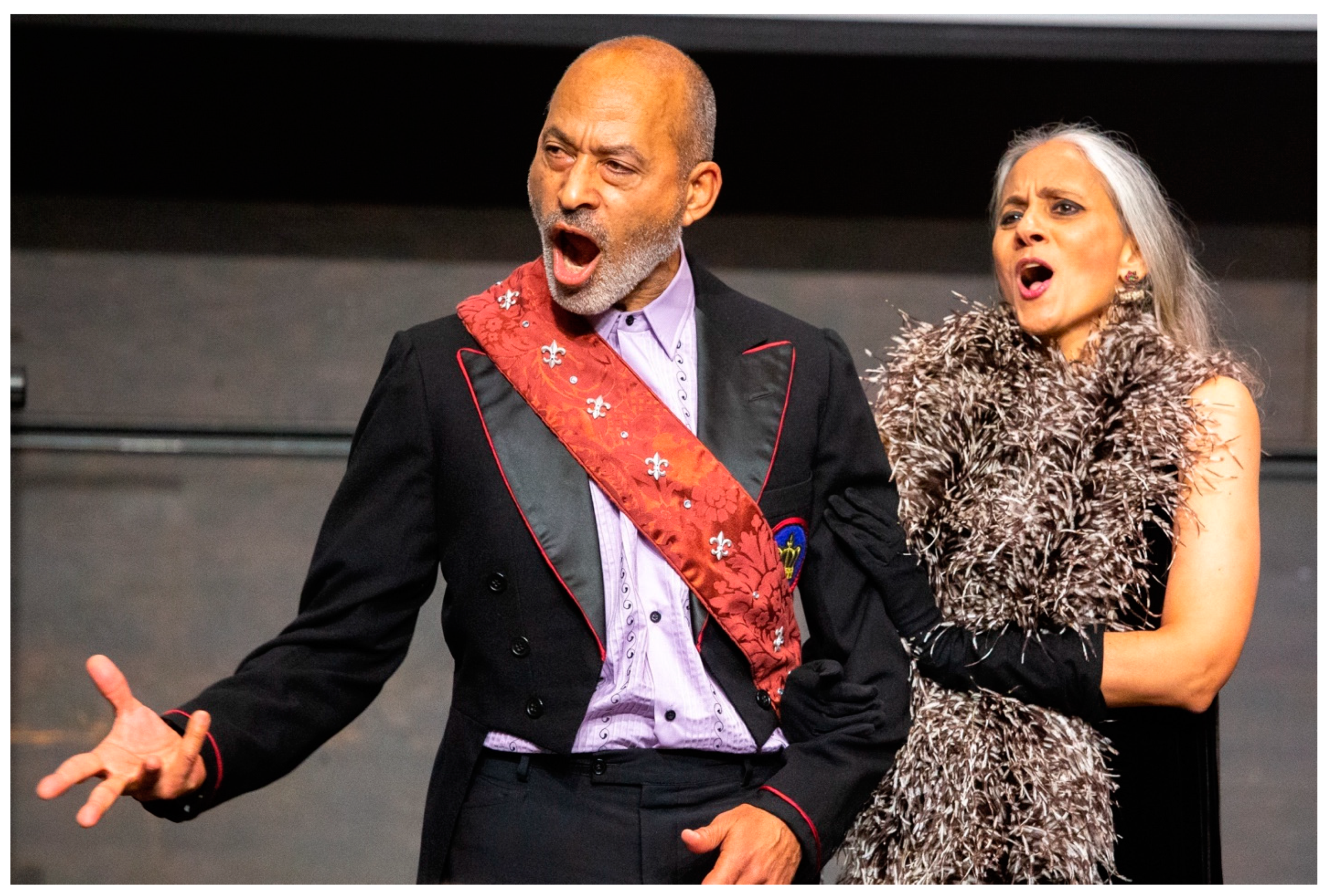

6. Ape Impersonators and Intercultural Performance

7. Towards the Next Version

There are no easy solutions to the ambivalent messages inherent in our work. The coordination of multiple narrative lines (sound, scenic, text, physical score, etc.) in live performance, as well as the multi-sensory nature of spectatorial attention, make the cognitive processing of information different from when reading an academic article or listening to a podcast. The theatre offers an unwieldy language for articulating an intellectual argument or analysis. On the other hand, it allows for affective responses more readily than scholarly writing. We do not want our work to be heavy handedly didactic, nor in the “preaching from the soapbox” model of agitprop theatre. Moreover, in seeking to build a performance piece that eventually can engage a broader audience than just students and faculty, we are mindful that while people come to the theatre to learn about social issues, they also come to be entertained. In the end, we do our best to address the questions our work raises, knowing that its message will always be contradictory, its insights only partial, and its humor enjoyed by some and lost on others.“…the dancing body of color is most often a mute or passive body—either a vehicle of cultural preservation or a clean slate upon which un-theorized instincts play themselves out—which are then credited for the artwork. These are ideologies that characteristically diminish and invisibilize the creative and political labor of artists of color and the complex processes in which they engage in working out the conceptual framework for choreography.”

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

| 1 | Viewpoints is a technique of movement improvisation based on principles of space and time that serves as a tool for performance composition. It originated in the work of choreographer Mary Overlie and later was developed by theatre directors Anne Bogart and Tina Landau to provide opportunities for actors to cultivate intuitive responses in collaborative processes (Bogart and Landau 2004). |

| 2 | Jerzy Grotowski (1933–1999) was a Polish theatre director whose intensive psycho-physical approaches to acting and performance making have been widely influential. (Grotowski 2002; Laster 2016; Richards 1995). |

| 3 | Richard Hofstadter first publicly identified a resistance to critical thought as deeply engrained in American culture (Hofstadter 1963). In recent times, anti-intellectualism has played out as a mistrust of various forms of scientific evidence (Milman 2016; Wong and Swain 2016) and is linked to political polarization (Jouet 2017; Motta 2017). Moreover, the association of a liberal arts education with elitism and the movement towards configuring higher education “as nothing more than a vocational tool” (Harvard Political Review 2012) have further fueled longer standing right-wing efforts to pit the supposed “political correctness” of postmodern academics against “values” (Bérubé and Nelson 1994) as well as the closing and defunding of humanities departments (Heller 2023; Mazzei 2023; McWilliams 2018; Townsend and Bradburn 2022). |

| 4 | Her manner correlates with what theatre pedagogue Jacques Lecoq has identified as the “neutral mask,” to identify the performer’s state of readiness, focus, and balance prior to entering into character or narrative (Lecoq 2006). Another analogue might be Eugenio Barba’s concept of the “pre-expressive” body, the performer’s trained physicality and behavior that creates a performance presence before stage action (Barba and Savarese 1991). |

| 5 | It is worth noting that Ajay J. Sinha’s recent book about the photographs produced through the transnational exchange between the Indian male dancer Ram Gopal and American male photographer Carl Van Vechten challenges common narratives about the subject-object relations of the Orientalist archive. Sinha posits a “two-way mimetic interaction between the East and West” (Sinha 2023, p. 8) and highlights the ways in which the dancer “refuses the photographic framing of abjection seen in race studies” through “photo-erotic self-fashioning” (p. 9). |

| 6 | In looking at the history of Bollywood cinema, Usha Iyer observes how dance’s cooptation by the cultural nationalism of the independence movement, as well as its conversion into a “respectable” past time by upper caste women, shifted movie stardom towards women with classical training and whose morally appropriate dances became a mainstay of early film (Iyer 2020, p. 95). Hari Krishnan traces the ways in which the social networks and artistic labor that brought Bharatanatyam to Tamil cinema popularized the ideas about classicism that organized elitist constructions of both the dance and the nation (Krishnan 2019). |

| 7 | Anthropologist Charles Lindholm identifies authenticity as “a cultural construct coincident with the rise of possessive individualism, the development of late capitalism, and the appearance of nationalism, among other factors” (Lindholm 2013, p. 390). He claims that it is here to stay in the current era of increasing anxiety about the validity of experience. Although authenticity is commonly construed as an essence, it is a social process, continuously negotiated and performed through socio-political relationships and instrumentally towards specific ends (Banks 2013). Studies of tourism have long acknowledged cultural authenticity as a performance and frequently tied to a sense of what modern societies have lost (Greenwood 1982; Kirshenblatt-Gimblett 1998; Kendall 2017; MacCannell 1976), a sentiment that leads to a commodification of the past (Cohen 1988; Goulding 2000). As a process that creatively synthesizes select cultural elements with the imagination, authenticity is often contradictory, although it grounds itself in claims of perduring truth. The intensity with which people pursue and defend the real and the authentic is tied to the role that feeling and emotion play in modern conceptions of the self and deeply held beliefs about who one really is (McCarthy 2009). |

| 8 | For a thorough discussion of cultural property from the perspectives of law, the ethics of heritage, race, and appropriation see https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/ethics-cultural-heritage/#WhatCultProp (accessed on 30 March 2023). |

| 9 | As argued by Jennifer Gonzalez, “Race, in all its historical complexity, is not an invention of visual culture but, among the ways in which race as a system of power is elaborated as both evident and self-evident, its visual articulation is one of the most significant” (Gonzalez 2003, p. 381). The visual syntax of race in the US has been studied across disciplines, in relation to various technologies that manufacture visible difference so that it can be translated into undeniable proof of the supremacy of white people and the need to control non-white bodies (Fine 2021; Kantayya 2020; Lott 2017; Nakamura 2008; Samuels 2019). |

| 10 | One noteworthy call for accountability in the arts came from the WeSeeYou White American Theatre campaign that garnered thousands of signatures in June 2020 to support a public statement that called out the retrograde nature of theatre and demanded a new social contract based on principles of anti-racism, equity, and transparency (https://www.weseeyouwat.com/ (accessed on 30 March 2023)). In the dance world, classical ballet was identified as a bastion of upper-class white privilege hiding behind the groundbreaking achievements of a mere handful of Black artists. Trenchant criticism of the tolerated racism in ballet companies included not only the treatment of black people, but also appropriative repertory, use of blackface, and the failure to consider standard colors for studio clothing (Komatsu 2020). Observers also accused ballet companies of a state of complacency in speaking out about violence against Black and brown bodies, even when claiming to be doing the work of diversity, equity and inclusion (Howard 2020). |

| 11 | In the aftermath of George Floyd’s death in 2020, presenters and companies have embraced a series of actions, beginning with producing anti-racism statements on websites and presenting land acknowledgements at the start of performances. Supporting these efforts are a growing number of consultants, operating as firms such as artEquity or individual facilitators such as Nicolle Brewer, who specialize in methods for harm reduction, the safe enactment of intimacy, sensitive representations of trauma, anti-racist work protocols, educational workshops on social justice issues, etc. Broadway producers have showcased record numbers of Black playwrights since 2020 (Weinert-Kendt 2021), regional stages have reimagined seasons after much “soul searching” (Mondello 2022), and professional organizations such as the Dramatists Guild and the Theatre Communications Group have hosted equity townhalls and workshops for members. |

| 12 | The Oscar wins were heralded as evidence of the evolving inclusivity of the film industry (Lai 2023; Macabasco 2023; Stone 2023; Subramaniam 2023). Yet they also revealed the challenges of Asian and Asian American representation. Supporting Actor Ke Huay Quan had disappeared from films after his debut as a child star because he was discouraged by the consistent lack of on-screen opportunities for Asians in Hollywood (Ordoña 2023). The dance that accompanied the live performance at the Oscars of the winning song from RRR did not feature any dancers of South Asian heritage (Jethwani and Sur 2023). The film itself, while a blockbuster, was criticized for “troubling” politics of caste and religious nationalism (Babu 2022), a matter that was absent from mainstream discussion. Moreover, Oscars host Jimmy Kimmel identified RRR as a “Bollywood” movie (a term that references the Hindi language industry) when it was actually a Telegu film (Kaur 2023). Inkoo Kang eloquently questioned whether an elite award show should even serve as the “yardstick of representational gains” to begin with (Kang 2023). |

| 13 | The Dance Studies Association hosted a series of roundtables at its annual meetings that interrogated basic terms such as “choreography” or “training,” and highlighted the field’s assumptions that wrongly pass as universal (Croft et al. 2019; Firmino-Castillo et al. 2019). The Association of Theater in Higher Education dedicated its 2022 annual conference to “Reparative Creativity.” Online platforms, such as Howlround Theatre Commons, sponsored webinars and uploaded a plethora of online resources for academic departments, performing arts presenters, companies, and funding bodies looking for anti-racist methodologies. |

| 14 | This is not surprising given the overwhelming commitment of theatre training in the US to versions of psychological realism, primarily with the aim of satisfying the demand for these skills in conventional film and television. Understanding these priorities requires understanding the history of theatre in higher education. Long relegated to English departments where drama was viewed in strictly literary terms, or departments of speech, theatre departments developed into training sites and mushroomed in relation to opportunities in an expanding Hollywood and regional theatre circuit. In so doing they navigated conversations about the relationship between theory and practice (Zarrilli 1995) and the role of skill-based learning in the liberal arts–including in developing college amateur theatre into professional companies (Berkeley 2008). The money-making capacity of programs that promote themselves as gateways to employment (and perhaps even stardom), even when statistics demonstrate that few graduates make livelihoods as actors, does not give institutions incentive to reinvent curricula significantly (Zazzali 2016). |

| 15 | Banerji discusses how the Natyashastra went from being a relatively obscure text to becoming the authoritative document during the modern period when British imperialism was countered by the Independence movement’s cultural nationalism. Questions about the morality of dance practices “energized the proponents of traditional performance, who could now justify their modern artistic pursuits through recourse to ancient evidence, and realign the political narratives in their favour by pointing to the longstanding value and praxis of dance in the Indian landscape, as attested by an eminent philosophical archive moored in antiquity” (Banerji 2021, p. 136). |

| 16 | The study of Sanskrit in European, Australian, and American universities has a long history (Tull 2015). In the past fifteen years, the authority of Western Sanskritists has been undermined by nativist, Hindutva critics in both India and abroad who decry some scholars’ critical approaches to the language and its ancient cultural world (Taylor 2015). In 2016 thousands of signatories – mostly from Indian institutions – denounced prolific and respected scholar Sheldon Pollock’s appointment as Chief Editor of Harvard’s Murty Classical Library of India essentially for his lack of “respect and empathy for the greatness of Indian civilization” (See the petition at: https://www.change.org/p/mr-n-r-narayana-murthy-and-mr-rohan-narayan-murty-removal-of-prof-sheldon-pollock-as-mentor-and-chief-editor-of-murty-classical-library (accessed on 30 March 2023)). Pollock was even accused of “demonising Hindus” in his “Hinduphobia” (Gangopadhyay 2018). Liberal voices identified the petition as evidence of a growing intolerance for intellectual inquiry (Majumdar 2016). |

| 17 | One can argue that Hindus’ claims about being victims and/or marginalized in the US, while simultaneously refusing to address issues of casteism and racism, constitutes “Hindu fragility” in ways that mirror the “white fragility” that protects white supremacy (Feminist Critical Hindu Studies Collective 2022). |

| 18 | Our concept of Red Peter parallels literature scholar Naama Harel’s assertion that the ape is not allegorical (a stand in for the history of slavery or capitalism, or for Jewish assimilation) but is a living being who is integral unto itself. Harel cites the ape’s ambiguous characteristics as corresponding to Kafka’s interest in confounding the clear demarcation between species, what she calls “humanimality” (Harel 2020). |

| 19 | I am indebted here to Harshita Mruthinti Kamath’s work on brahmin men’s enactments of female characters in the South Indian dance of Kuchipudi (Kamath 2019). Drawing from performers’ own understandings of “guising” and their vernacularizing of the Sanskrit terminology of maya, Kamath examines brahmin masculinity through the lens of “constructed artifice.” She observes that impersonating both constructs brahmin masculinity as well as exposes it as artifice. Similarly, our apes seek to educate their audiences about the fact that what is perceived as reality is the result of an ongoing, constructive process. |

| 20 | For a survey of processes and consequences of simianization in various historical and social contexts see Hund, Mills, and Sebastiani’s edited volume, Simianization: Apes, Gender, Class and Race (Hund et al. 2015). |

| 21 | Various disciplines of knowledge production have conspired over a few hundred years to entrench beliefs that equated Black peoples and others with apes and monkeys. German and British thinkers during the 18th century theorized and represented human “varieties” in relation to aesthetics and beliefs about ideal humans (Bindman 2002). With the advent of scientific interest in studying human difference in the 18th century, an area of inquiry eventually institutionalized in the late 19th century as physical anthropology even though no scientific evidence could support racist claims, economists committed themselves to the belief that the ape-like nature of some non-European peoples explained their relative lack of wealth and industry (O’Flaherty and Shapiro 2004). In the 20th century, Hollywood cinema has enacted racial hatred and anxiety in the various makings of King Kong (Rony 1996) and Planet of the Apes (Greene 1998). The trope of the ape “has maintained a pernicious grip on the American imagination” and as such has justified the subhuman treatment of Black people by the criminal justice system (Staples 2018). |

| 22 | For discussion of the belief that humans are distinct because of their unique anatomy and physical capacities see Anderson and Perrin (2018). For an analysis of the zoöpolitical logics that support views of the environment and the future see Srinivasan and Kasturirangan (2016) and Swartz and Mishler (2022). |

| 23 | The ape not only reminds the scientists of the absurdity of their human air of superiority, he makes them into the objects of his report. As Margot Norris says, “…by focusing attention on the barbaric methods of his humanization and civilization, he makes human behavior the ‘specimen’—the inexplicable object of his study” (Norris 1980, p. 1246). |

References

- Abu-Lughod, Lila. 1990. The Romance of Resistance: Tracing Transformations of Power through Bedouin Women. American Ethnologist 17: 41–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen, Matthew Harp. 1997. Rewriting the Script for South Indian Dance. TDR (1988-) 41: 63–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, Kay, and Colin Perrin. 2018. Removed from Nature: The Modern Idea of Human Exceptionality. Environmental Humanities 10: 447–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ansari, Ifra Shams. 2021. ‘Sanskritization’: A Revisit of Its Relevance in Contemporary India. Medium. February 28. Available online: https://ifrashams.medium.com/sanskritization-a-revisit-of-its-relevance-in-contemporary-india-545ba385f1da (accessed on 23 March 2023).

- Associated Press. 2023. Seattle Becomes First US City to Ban Caste-Based Discrimination. The Guardian. February 21. Available online: https://www.theguardian.com/us-news/2023/feb/21/seattle-ban-caste-based-discrimination (accessed on 20 May 2023).

- Babu, Ritesh. 2022. RRR Is an Incredible Action Movie with Seriously Troubling Politics. Vox. July 20. Available online: https://www.vox.com/23220275/rrr-netflix-tollywood-hindutva-caste-system-oscars-2023 (accessed on 24 March 2023).

- Balme, Christopher B. 1999. Decolonizing the Stage: Theatrical Syncretism and Post-Colonial Drama. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Banerji, Anurima. 2010. Paratopias of Performance: The Choreographic Practices of Chandralekha. In Planes of Composition: Dance, Theory, and the Global. Edited by André Lepecki and Jenn Joy. Kolkata: Seagull Books, pp. 346–71. [Google Scholar]

- Banerji, Anurima. 2019. Dancing Odissi: Paratopic Performances of Gender and State. Chicago: Seagull Books/University of Chicago Press. [Google Scholar]

- Banerji, Anurima. 2021. The Laws of Movement: The Natyashastra as Archive for Indian Classical Dance. Contemporary Theatre Review 31: 132–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banerji, Anurima. 2022. The Award-Wapsi Controversy in India and the Politics of Dance. South Asian History and Culture 14: 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banerji, Anurima, and Ilaria Distante. 2009. An Intimate Ethnography. Women and Performance: A Journal of Feminist Theory 19: 35–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banks, Marcus. 2013. Post-Authenticity: Dilemmas of Identity in the 20th and 21st Centuries. Anthropological Quarterly 86: 481–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barba, Eugenio, and Nicolas Savarese. 1991. A Dictionary of Theatre Anthropology: The Secret Art of the Performer. New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Beam, Adam. 2016. GOP Hopeful Not Sorry for Depicting Obamas as Monkeys. AP News. September 30. Available online: https://apnews.com/article/us-news-kentucky-barack-obama-lexington-monkeys-90ec82dfca4f45e48628e4ae45b8247f (accessed on 23 April 2023).

- Behdad, Ali. 2016. Camera Orientalist: Reflections on Photography of the Middle East. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press. [Google Scholar]

- Berkeley, Anne. 2008. Changing Theories of Undergraduate Theatre Studies, 1945–1980. The Journal of Aesthetic Education 42: 57–70. [Google Scholar]

- Bérubé, Michael, and Cary Nelson. 1994. Public Access: Literary Theory and American Cultural Politics. New York: Verso. [Google Scholar]

- Bharucha, Rustom. 1993. Theatre and the World: Performance and Politics of Culture. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Bharucha, Rustom. 1995. Chandralekha: Woman, Dance, Resistance. New Delhi: Harper Collins. [Google Scholar]

- Bindman, David. 2002. Ape to Apollo: Aesthetics and the Idea of Race in the 18th Century. Ithaca: Cornell University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Bogart, Anne, and Tina Landau. 2004. The Viewpoints Book: A Practical Guide to Viewpoints and Composition. New York: Theatre Communications Group. [Google Scholar]

- Bose, Mandakranta. 1991. Movement and Mimesis: The Idea of Dance in the Sanskritic Tradition. Dordrecht: Kluwer Academic Publishers. [Google Scholar]

- Bose, Mandakranta. 1995. The Dance Vocabulary of Classical Dance. Delhi: Sri Satguru Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Bose, Mandakranta. 2001. Speaking of Dance: The Indian Critique. New Delhi: D.K. Printworld (P) Ltd. [Google Scholar]

- Brown, Micheal F. 1996. On Resisting Resistance. American Anthropologist 98: 729–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burt, Ramsay. 2003. The Male Dancer: Bodies, Spectacle and Sexuality. New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Butler, Judith. 1990. Gender Trouble: Feminism and the Subversion of Identity. New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Cabranes-Grant, Leo. 2016. From Scenarios to Networks. Performing the Intercultural in Colonial Mexico. Evanston: Northwestern University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Capehart, Jonathan. 2011. Going Ape over Racist Depiction of Obama. Washington Post. April 19. Available online: https://www.washingtonpost.com/blogs/post-partisan/post/going_ape_over_racist_depiction_of_obama/2011/03/04/AFvrOs5D_blog.html (accessed on 19 April 2023).

- Chakravorty, Pallabi. 2000. From Interculturalism to Historicism: Reflections on Classical Indian Dance. Dance Research Journal 32: 108–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chandralekha. 1984. Contemporary Relevance in Classical Dance—A Personal Note. National Centre for the Performing Arts Journal XIII: 60–4. [Google Scholar]

- Chatterjea, Ananya. 2004. Butting Out: Reading Resistive Choreographies through Works by Jawole Willa Jo Zollar and Chandralekha. Middletown: Wesleyan University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Chettur, Padmini. 2014. The Honest Body: Remembering Chandralekha. In Voyages of the Body and Mind: Selected Female Icons of India and Beyond. Edited by Anita Ratnam and Ketu H. Katrak. Newcastle upon Tyne: Cambridge Scholars Publishing, pp. 114–18. [Google Scholar]

- Chettur, Padmini. 2016. The Body Laboratory. In Tilt Pause Shift: Dance Ecologies in India. Edited by Anita Cherian. New Delhi: Tulika Books, pp. 155–67. [Google Scholar]

- Chung, Christine. 2017. From Elvis to Iggy: Cultural Appropriation Should Not Be Used for Personal Gain. The Daily Orange. March 19. Available online: https://dailyorange.com/2017/03/from-elvis-to-iggy-cultural-appropriation-should-not-be-used-for-personal-gain/#:~:text=Indian%20culture%20has%20been%20specifically,make%20her%20video%20seem%20unique (accessed on 28 March 2023).

- Cohen, Erik. 1988. Authenticity and Commoditization in Tourism. Annals of Tourism Research 15: 371–86. [Google Scholar]

- Coorlawala, Uttara Asha. 1992. Ruth St. Denis and India’s Dance Renaissance. Dance Chronicle 15: 123–52. [Google Scholar]

- Coorlawala, Uttara Asha. 1996. Darshan and Abhinaya: An Alternative to the Male Gaze. Dance Research Journal 28: 19–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coorlawala, Uttara Asha. 2004. The Sanskritized Body. Dance Research Journal 36: 50–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Croft, Clare, Imani Kai Johnson, Anthea Kraut, Tarah Munjulika, Shanti Pillai, and Janet O’ Shea. 2019. Decolonizing Dance Discourses: Gathering 2. Paper presented at the Dance Studies Association Annual Conference: Dancing in Common, Evanston, IL, USA, August 8–11. [Google Scholar]

- Daly, Ann. 1991. Unlimited Partnership: Dance and Feminist Analysis. Dance Research Journal 23: 2–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, Crystal U. 2018. Tendus and Tenancy: Black Dancers and the White Landscape of Dance Education. In the Palgrave Handbook of Race and Arts in Education. Basingstoke: Palgrave McMillan. [Google Scholar]

- Davis, Crystal U. 2019. Laying New Ground: Uprooting White Privilege and Planting Seeds of Equity and Inclusion. In Dance Education and Responsible Citizenship: Promoting Civic Engagement through Effective Dance Pedagogies. Edited by Karen Schupp. New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- DeFrantz, Thomas F., and SLIPPAGE. 2018. White Privilege. Theater 48: 23–37. [Google Scholar]

- Desmond, Jane. 1991. Dancing out the Difference: Cultural Imperialism and Ruth St. Denis’s ‘Radha’ of 1906. Signs 17: 28–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dolan, Jill. 2005. Utopia in Performance: Finding Hope at the Theatre. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan. [Google Scholar]

- Dox, Donnalee. 2006. Dancing around Orientalism. TDR 50: 52–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dutt, Bishnupriya, and Urmimala Sarkar Munsi. 2010. Engendering Performance: Indian Women Performers in Search of an Identity. New Delhi: Sage Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Feminist Critical Hindu Studies Collective. 2022. Hindu Fragility and the Politics of Mimicry in North America. In The Immanent Frame: Secularism, Religion, and the Public Sphere. Social Science Research Council. November 2, Available online: https://tif.ssrc.org/2022/11/02/hindu-fragility-and-the-politics-of-mimicry-in-north-america/ (accessed on 24 March 2023).

- Fine, Peter. 2021. The Design of Race: How Visual Culture Shapes America. London: Bloomsbury. [Google Scholar]

- Firmino-Castillo, Maria, Jasmine Johnson, Anusha Kedhar, Cynthia Ling Lee, Prarthana Purkayastha, and Arabella Stanger, eds. 2019. Decolonizing Dance Discourses: Gathering 1. Paper presented at the Dance Studies Association Annual Conference: Dancing in Common, Evanston, IL, USA, August 8–11. [Google Scholar]

- Fischer-Lichte, Erika, Torsten Jost, and Saskya Iris Jain, eds. 2014. The Politics of Interweaving Performance Cultures: Beyond Postcolonialism. New York and London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Flåten, Lars Tore. 2019. The Inclusion-Moderation Thesis: India’s BJP. Oxford Research Encyclopedias: Politics, April 26. Available online: https://doi.org/10.1093/acrefore/9780190228637.013.789 (accessed on 23 March 2023).

- Foster, Susan L., ed. 2009. Worlding Dance. London: Palgrave Macmillan. [Google Scholar]

- Gangopadhyay, Kausik. 2018. Unmasking Sheldon Pollock’s Blatant and Unabashed Hinduphobia. OpIndia. May 29. Available online: https://www.opindia.com/2018/05/unmasking-sheldon-pollocks-blatant-and-unabashed-hinduphobia/ (accessed on 23 March 2023).

- Geary, David. 2013. Incredible India in a Global Age: The Cultural Politics of Image Branding in Tourism. Tourist Studies 13: 36–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gere, David. 2001. 29 Effeminate Gestures: Choreographer Joe Goode and the Heroism of Effeminacy. In Dancing Desires: Choreographing Sexualities on and off Stage. Edited by Jane C. Desmond. Madison: University of Wisconsin Press, pp. 349–81. [Google Scholar]

- Gledhill, John. 2012. Introduction: A Case for Rethinking Resistance. In New Approaches to Resistance in Brazil and Mexico. Edited by John Gledhill and Patience A. Schell. Durham: Duke University Press, pp. 1–20. [Google Scholar]

- Gomez-Peña, Guillermo. 1993. Warrior for Gringostroika. Saint Paul: Graywolf Press. [Google Scholar]

- Gonzalez, Jennifer. 2003. Only Skin Deep: Changing Visions of the American Self. New York: Abrams Books. [Google Scholar]

- Gottschild, Brenda Dixon. 1996. Digging the Africanist Presence in American Performance: Dance and other Contexts. Westport: Greenwood Press. [Google Scholar]

- Goulding, Christina. 2000. The Commodification of the Past, Postmodern Pastiche, and the Search for Authentic Experiences at Contemporary Heritage Attractions. European Journal of Marketing 34: 835–53. [Google Scholar]

- Govindarajan, Padmapriya. 2016. India’s New Education Policy: What Are the Priorities? The Diplomat. July 29. Available online: https://thediplomat.com/2016/07/indias-new-education-policy-what-are-the-priorities/ (accessed on 23 March 2023).

- Greene, Eric. 1998. Planet of the Apes as American Myth: Race, Politics, and Popular Culture. Middletown: Wesleyan University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Greenwood, Davydd. 1982. Cultural Authenticity. Cultural Survival Quarterly 6: 27–28. [Google Scholar]

- Grotowski, Jerzy. 2002. Towards a Poor Theatre. Edited by Eugenio Barba. New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Hall, Stuart. 2000. Who Needs Identity? In Identity: A Reader. London: Sage Publications, pp. 1–17. [Google Scholar]

- Harel, Naama. 2020. Kafka’s Zoopoetics: Beyond the Human-Animal Barrier. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press. [Google Scholar]

- Harvard Political Review. 2012. The War on the Humanities. November 21. Available online: https://harvardpolitics.com/the-war-on-the-humanities/ (accessed on 15 March 2023).

- Hawthorn, Ainsley. 2019. Middle Eastern Dance and What We Call It. Dance Research: The Journal of the Society for Dance Research 37: 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heller, Nathan. 2023. The End of the English Major. The New Yorker. February 27. Available online: https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2023/03/06/the-end-of-the-english-major (accessed on 2 April 2023).

- Hernández, Jillian. 2020. Racialized Sexuality: From Colonial Product to Creative Practice. Oxford Research Encyclopedias. February 28. Available online: https://doi.org/10.1093/acrefore/9780190201098.013.346 (accessed on 30 March 2023).

- Herrera, Brian. 2017. ’But Do We Have the Actors for That?’: Some Principles of Practice for Staging Latinx Plays in a University Theatre Context. Theatre Topics 27: 23–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hofstadter, Richard. 1963. Anti-Intellectualism in American Life. New York: Alfred A. Knopf. [Google Scholar]

- Hollander, Jocelyn A., and Rachel L. Einwohner. 2004. Conceptualizing Resistance. Sociological Forum 19: 533–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howard, Theresa Ruth. 2020. Where is Your Outrage? Where is Your Support? Dance Magazine. May 31. Available online: https://www.dancemagazine.com/dance-companies-black-lives-matter/ (accessed on 23 March 2023).

- Hund, Wulf D., Charles W. Mills, and Silvia Sebastiani. 2015. Simianization: Apes, Gender, Class and Racism. Munster: LIT Verlag. [Google Scholar]

- Iati, Marisa. 2022. Cal State Banned Caste Discrimination. Two Hindu Professors Sued. The Washington Post. October 24. Available online: https://www.washingtonpost.com/religion/2022/10/24/hindu-caste-discrimination-lawsuit/ (accessed on 20 May 2023).

- Imada, Adria L. 2011. Transnational ‘Hula’ as Colonial Culture. Journal of Pacific History 46: 149–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iyer, Usha. 2020. Dancing Women: Choreographing Corporeal Histories of Hindi Cinema. London and New York: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Jethwani, Divya, and Snigdha Sur. 2023. Naatu Naatu at the Oscars: A Cultural Triumph Gone Wrong. The Juggernaut. March 15. Available online: https://www.thejuggernaut.com/naatu-naatu-oscars-no-indian-dancers-south-asian-representation (accessed on 24 March 2023).

- Johar, Navtej. 2016. The Centrality of Caste: Dance and the Making of a National Indian Identity. India International Centre Quarterly 43: 36–50. [Google Scholar]

- Jouet, Mugambi. 2017. Exceptional America: What Divides Americans from the World and from Each Other. Berkeley: University of California Press. [Google Scholar]

- Kamath, Harshita Mruthinti. 2019. Impersonations: The Artifice of Brahmin Masculinity in South Indian Dance. Oakland: University of California Press. [Google Scholar]

- Kamath, Harshita Mruthinti, and Pamela Lothspeich. 2023. Introduction. In Mimetic Desires: Impersonation and Guising across South Asia. Edited by Harshita Mruthinti Kamath and Pamela Lothspeich. Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press, pp. 1–23. [Google Scholar]

- Kandasamy, Meena. 2022. Anti-Hindi Movement: The Grassroots Struggle for Tamil Pride. Outlook. May 29. Available online: https://www.outlookindia.com/magazine/national/anti-hindi-movement-the-grassroots-struggle-for-tamil-pride-magazine-193541?utm_source=related_story (accessed on 24 March 2023).

- Kang, Inkoo. 2023. The Oscars and the Pitfalls of Feel-Good Representation. The New Yorker. March 12. Available online: https://www.newyorker.com/culture/cultural-comment/the-oscars-and-the-pitfalls-of-feel-good-representation (accessed on 24 March 2023).

- Kantayya, Shalini, dir. 2020. Coded Bias. Brooklyn: 7th Empire Media, Film. [Google Scholar]

- Kaur, Gurpreet. 2023. Oscars Host Jimmy Kimmel Terms ‘RRR’ a ‘Bollywood Movie’; Fans React, ‘It’s Indian Cinema’. Outlook. March 13. Available online: https://www.outlookindia.com/art-entertainment/oscars-host-jimmy-kimmel-terms-rrr-a-bollywood-movie-fans-react-it-s-indian-cinema--news-269758 (accessed on 24 March 2023).

- Kedhar, Anusha. 2020. It is Time for a Caste Reckoning in Indian Classical Dance. Conversations Across The Field of Dance Studies XL: 16–19. [Google Scholar]

- Kendall, Paul. 2017. The Location of Cultural Authenticity: Identifying the Real and the Fake in Urban Guizhou. The China Journal, 77. Available online: https://www.journals.uchicago.edu/doi/full/10.1086/688851 (accessed on 23 March 2023).

- Kerr-Berry, Julie A. 2012. Dance Education in an Era of Racial Backlash: Moving Forward as We Step Backwards. Journal of Dance Education 12: 48–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirshenblatt-Gimblett, Barbara. 1998. Destination Culture: Tourism, Museums, and Heritage. Berkeley: University of California Press. [Google Scholar]

- Kliger, Robyn. 1996. ‘Resisting Resistance’: Historicizing Contemporary Models of Agency. Kroeber Anthropological Society Papers 80: 137–56. [Google Scholar]

- Knowles, Ric. 2010. Theatre and Interculturalism. London: Palgrave Macmillan. [Google Scholar]

- Komatsu, Sara. 2020. An Open Letter to the Ballet Community. The Harvard Crimson. June 22. Available online: https://www.thecrimson.com/article/2020/6/22/an-open-letter-to-the-ballet-community/ (accessed on 23 March 2023).

- Kondo, Dorinne K. 1990. ‘M. Butterfly’: Orientalism, Gender, and a Critique of Essentialist Identity. Cultural Critique 16: 5–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kowal, Rebekah. 2010. How to Do Things with Dance: Performing Change in Postwar America. Middletown: Wesleyan University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Kowal, Rebekah. 2020. Dancing the World Smaller: Staging Globalism in Mid-Century America. New York: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Krishnan, Hari. 2019. Celluloid Classicism Early Tamil Cinema and the Making of Modern Bharatanatyam. Middletown: Wesleyan University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Kwan, Sansan. 2021. Love Dances: Loss and Mourning in Intercultural Collaboration. New York: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Lai, K. K. Rebecca. 2023. Asian Actors Have Been Underrepresented at the Oscars for Decades. Here’s the History. New York Times. March 12. Available online: https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2023/03/02/movies/oscars-asian-actors-history.html (accessed on 24 March 2023).

- Laster, Dominica. 2016. Grotowski’s Bridge Made of Memory: Embodied Memory, Witnessing and Transmission in the Grotowski Work. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. [Google Scholar]

- Lawrence, Patrick S. 2021. Transnational Sexualities. In Asian American Literature in Transition, 1965–1996. Edited by Asha Nadkarni and Cathy J. Schlund-Vials. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 310–25. [Google Scholar]

- Lecoq, Jacques. 2006. Theatre of Movement and Gesture. Edited by David Bradby. New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Lei, Daphne P. 2011. Interruption, Intervention and Interculturalism: Robert Wilson’s HIT Productions in Taiwan. Theatre Journal 63: 571–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindholm, Charles. 2013. The Rise of Expressive Authenticity. Anthropological Quarterly 86: 361–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lott, Eric. 2017. Black Mirror: The Cultural Contradictions of American Racism. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Mabingo, Alfdaniels. 2019. Intercultural Dance Education in the Era of Neo-State Nationalism: The Relevance of African Dances to Student Performers’ Learning Experiences in the United States. Journal of Dance Education 19: 47–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macabasco, Lisa Wong. 2023. What ‘Everything Everywhere All at Once’s’ Oscars Win Means for Asian American Representation. The Guardian. March 13. Available online: https://www.theguardian.com/film/2023/mar/13/everything-everywhere-asian-representation-oscars-sweep (accessed on 24 March 2023).

- MacCannell, Dean. 1976. The Tourist: A New Theory of the Leisure Class. London: Macmillan. [Google Scholar]

- Maira, Sunaina. 2008. Belly Dancing: Arab-Face, Orientalist Feminism, and U.S. Empire. American Quarterly 60: 317–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Majumdar, Nandini. 2016. What the Petition against the Sanskritist Sheldon Pollock Is Really About. The Wire. March 2. Available online: https://thewire.in/books/what-the-petition-against-the-sanskritist-sheldon-pollock-is-really-about (accessed on 23 March 2023).

- Mazzei, Patricia. 2023. DeSantis’s Latest Target: A Small College of ‘Free Thinkers’. The New York Times. February 14 sec. U.S. Available online: https://www.nytimes.com/2023/02/14/us/ron-desantis-new-college-florida.html (accessed on 2 April 2023).

- McCarthy, E Doyle. 2009. Emotional Performances as Dramas of Authenticity. In Authenticity in Culture, Self, and Society. Edited by Phillip Vannini and J. Patrick Williams. Surrey: Ashgate, pp. 241–55. [Google Scholar]

- McKenzie, Jon. 2001. Perform or Else: From Discipline to Performance. London and New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- McWilliams, James. 2018. Conservative Media Is Waging a War on the Humanities, and It’s Succeeding. Pacific Standard. July 16. Available online: https://psmag.com/education/conservative-media-is-waging-a-war-on-the-humanities-and-its-succeeding (accessed on 2 April 2023).

- Meduri, Avanthi. 2008. Temple Stage as Historical Allegory in Bharatanatyam: Rukmini Devi as Dancer-Historian. In Performing Pasts Reinventing the Arts in Modern South India. Edited by Indira Vishwanathan Peterson and Davesh Soneji. New Delhi and New York: Oxford University Press, pp. 133–64. [Google Scholar]

- Milman, Oliver. 2016. NASA’s Climate Research Will Likely Be Scrapped by Trump. Newsweek. November. Available online: http://www.newsweek.com/nasas-climate-research-will-likely-be-scrapped-trump-525559 (accessed on 30 March 2023).

- Min, Susette. 2018. Unnamable Encounters: A Phantom History of Multicultural and Asian American Art Exhibitions, 1990–2008. In Unnamable: The Ends of Asian American Art. New York: NYU Press, pp. 33–84. [Google Scholar]

- Mitra, Royona. 2006. Living a Body Myth, Performing a Body Reality: Reclaiming the Corporeality and Sexuality of the Indian Female Dancer. Feminist Review, 67–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitra, Royona. 2015. Akram Khan: Dancing New Interculturalism. London: Palgrave Macmillan. [Google Scholar]

- Mondello, Bob. 2022. Across the U.S., Regional Theaters Are Starting to Transform. Here’s Why. NPR. September 21. Available online: https://www.npr.org/2022/09/21/1123177992/american-theater-is-changing-heres-why (accessed on 23 March 2023).

- Morcom, Anna. 2013. Illicit Worlds of Indian Dance: Cultures of Exclusion. London: C. Hurst & Company. [Google Scholar]

- Motta, Matthew. 2017. The Dynamics and Political Implications of Anti-Intellectualism in the United States. American Politics Research 46: 465–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mulvey, Laura. 1975. Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema. Screen 16: 6–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muñoz, José Esteban. 1999. Disidentifications: Queers of Color and the Performance of Politics. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press. [Google Scholar]

- Nakamura, Lisa. 2008. Digitizing Race: Visual Cultures of the Internet. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press. [Google Scholar]

- Ness, Sally Ann. 2008. Bali, the Camera, and Dance: Performance Studies and the Lost Legacy of the Mead/Bateson Collaboration. The Journal of Asian Studies 67: 1251–76. [Google Scholar]

- Nochlin, Linda. 1989. The Imaginary Orient. In The Politics of Vision: Essays on Nineteenth-Century Art and Society. Boulder: Westview Press, pp. 33–59. [Google Scholar]

- Norris, Margot. 1980. Darwin, Nietzsche, Kafka, and the Problem of Mimesis. Comparative Literature 95: 1232–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Flaherty, Brendan, and Jill S. Shapiro. 2004. Apes, Essences, and Races: What Natural Scientists Believed about Human Variation, 1700–1900. In Race, Liberalism and Economics. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, pp. 21–55. [Google Scholar]

- Ordoña, Michael. 2023. ‘Everything Everywhere’s’ Ke Huy Quan Wins Oscar for Supporting Actor. Los Angeles Times. March 12. Available online: https://www.latimes.com/entertainment-arts/awards/story/2023-03-12/oscars-2023-ke-huy-quan-wins-best-supporting-actor-everything-everywhere-all-at-once (accessed on 24 March 2023).

- Ortner, Sherry. 1995. Resistance and the Problem of Ethnographic Refusal. Society for Comparative Study of Society and History 37: 173–93. [Google Scholar]

- O’Shea, Janet. 2007. At Home in the World: Bharata Natyam on the Global Stage. Middletown: Wesleyan University Press. [Google Scholar]

- O’Shea, Janet. 2008. Serving Two Masters? Bharatanatyam and Tamil Cultural Production. In Performing Pasts: Reinventing the Arts in Modern South India. Edited by Indira Viswanathan Peterson and Davesh Soneji. New Delhi: Oxford University Press, pp. 165–93. [Google Scholar]

- O’Shea, Janet. 2016. Festivals and Local Identities in a Global Economy: The Festival of India and Dance Umbrella. In Choreography and Corporeality: Relay in Motion. Edited by Thomas F. DeFrantz and Philipa Rothfield. London: Palgrave Macmillan, pp. 85–102. [Google Scholar]

- Panaitiu, Ioana G. 2020. Apes and Anticitizens: Simianization and U.S. National Identity Discourse. Social Identities: Journal for the Study of Race, Nation, and Culture 26: 109–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parker, Andrew, and Eve Kosofsky Sedgwick. 1995. Performativity and Performance. New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Pavis, Patrice. 1996. Introduction: Towards a Theory of Interculturalism in Theatre? In The Intercultural Performance Reader. Edited by Patrice Pavis. New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Peterson, Christopher. 2013. Bestial Traces: Race, Sexuality, Animality. New York: Fordham University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Petrović, Tanja. 2018. Political Parody and the Politics of Ambivalence. Annual Review of Anthropology 47: 201–16. [Google Scholar]

- Pillai, Nrithya. 2020. The Politics of Naming the South Indian Dancer. Conversations Across The Field of Dance Studies XL: 13–15. [Google Scholar]

- Pillai, Nrithya. 2022. Re-Casteing the Narrative of Bharatanatyam. Economic and Political Weekly, 57. Available online: https://epw.in/engage/article/re-casteing-narrative-bharatanatyam (accessed on 30 March 2023).

- Pillai, Shanti. 2017. Global Rasikas: Audience Reception for Akram Khan’s Desh. The Drama Review 61: 12–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pollock, Sheldon. 2016. A Rasa Reader: Classical Indian Aesthetics. New York: Columbia University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Popkin, Lionel. 2021. The Complexities of Indian Dance at the Pillow. In PillowVoices. Becket: Jacob’s Pillow. Available online: https://pillowvoices.org/episodes/the-complexities-of-indian-dance-at-the-pillow (accessed on 30 March 2023).

- Prakash, Brahma. 2019. Cultural Labour: Conceptualizing the ‘Folk Performance’ in India. New Delhi: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Prasanna, Pooja. 2021. The Politics of Hindi Imposition. The News Minute Cooperative Federalism Reporting Project. YouTube. October 3. Available online: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=njmHROi40n4 (accessed on 23 March 2023).

- Prichard, Robin. 2019. From Color-Blind to Color-Conscious. Journal of Dance Education 19: 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Putcha, Rumya Sree. 2023. The Dancer’s Voice: Performance and Womanhood in Transnational India. Durham: Duke University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Richards, Thomas. 1995. At Work with Grotowski on Physical Actions. London and New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Rony, Fatimah Tobing. 1996. The Third Eye: Race, Cinema and Ethnographic Spectacle. Durham: Duke University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Rose, Tricia. 1994. Bad Sistas: Black Women Rappers and Sexual Politics in Rap Music. In Black Noise: Rap Music and Black Culture in Contemporary America. Middletown: Wesleyan University Press, pp. 146–82. [Google Scholar]

- Roseberry, William. 1994. Hegemony and the Language of Contention. In Everyday Forms of State Formation: Revolution and the Negotiation of Rule in Modern Mexico. Edited by Gilbert M. Joseph and Daniel Nugent. Durham: Duke University Press, pp. 355–65. [Google Scholar]

- Said, Edward W. 1994. Orientalism. New York: Vintage Books. [Google Scholar]

- Samuels, Shirley, ed. 2019. Race and Vision in the Nineteenth Century United States. New York: Lexington Books. [Google Scholar]

- Sarkar Munsi, Urmimala. 2010. Natyasastra: Emerging (Gender) Codes and the Woman Dancer. In Engendering Performance: Indian Women Performers in Search of an Identity. Edited by Bishnupriya Dutt and Urmimala Sarkar Munsi. New Delhi: Sage Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Sarkar Munsi, Urmimala. 2017. Buy One, Get One Free: The Dance Body for the Indian Film and Television Industry. In Performance, Feminism and Affect in Neoliberal Times. Edited by Elin Diamond, Denis Varney and Candice Amich. London: Palgrave Macmillan, pp. 175–87. [Google Scholar]

- Savarese, Nicola, and Richard Fowler. 2001. 1931: Antonin Artaud Sees Balinese Theatre at the Paris Colonial Exposition. TDR (1988-) 45: 51–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scott, James C. 1990. Domination and the Arts of Resistance: Hidden Transcripts. New Haven: Yale University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Seymour, Susan. 2006. Resistance. Anthropological Theory 6: 303–21. [Google Scholar]

- Shawn, Ted, John Henry Nash, and John Howell. 1920. Ruth St. Denis: Pioneer and Prophet—Being a History of Her Cycle of Oriental Dances. San Francisco: Printed for John Howell by John Henry Nash. [Google Scholar]

- Shay, Anthony, and Barbara Sellers-Young. 2003. Belly Dance: Orientalism: Exoticism: Self-Exoticism. Dance Research Journal 35: 13–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sholette, Greg. 2017. Delirium and Resistance: Activist Art and the Crisis of Capitalism. London: Pluto Press. [Google Scholar]

- Sinha, Ajay J. 2023. Photo-Attractions: An Indian Dancer, an American Photographer, and a German Camera. New Brunswick: Rutgers University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Soneji, Davesh. 2011. Unfinished Gestures: Devadasis, Memory, and Modernity in South India. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. [Google Scholar]

- Srinivas, M. N. 1952. Religion and Society among the Coorgs of South India. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Srinivasan, Kritika, and Rajesh Kasturirangan. 2016. Political Ecology, Development and Human Exceptionalism. Geoforum 75: 125–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srinivasan, Priya. 2009. The Bodies Beneath the Smoke or What’s Behind the Cigarette Poster. Discourses 3: 7–48. [Google Scholar]

- Srinivasan, Priya. 2011. Sweating Saris: Indian Dance as Transnational Labor. Philadelphia: Temple University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Staples, Brent. 2018. The Racist Trope that Won’t Die. New York Times. June 17. Available online: https://www.nytimes.com/2018/06/17/opinion/roseanne-racism-blacks-apes.html (accessed on 23 April 2023).

- Stone, J. R. 2023. Loud Cheers from Bay Area Asian American Community as Michelle Yeoh Makes Oscars History. ABC News. Available online: https://abc7news.com/oscars-2023-winners-michelle-yeoh-everything-everywhere-all-at-once-asian-americans/12947955/ (accessed on 24 March 2023).

- Subramaniam, Tara. 2023. Major Night for Asian Representation at the Oscars, with Historic Wins for ‘Everything Everywhere All at Once’ and ‘RRR’. CNN. Available online: https://www.cnn.com/style/article/oscars-asian-representation-rrr-michelle-yeoh-intl-hnk/index.html (accessed on 24 March 2023).

- Swartz, Brian, and Brent D. Mishler, eds. 2022. Speciesism in Biology and Culture: How Human Exceptionalism is Pushing Planetary Boundaries. New York: Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Taylor, Diana. 2001. Making a Spectacle: The Mothers of the Plaza de Mayo. Journal of the Motherhood Initiative for Research and Community Involvement 3: 97–109. [Google Scholar]

- Taylor, McComas. 2015. Tigers vs. Goats: Rajiv Malhotra’s Battle for Sanskrit. Website of the Asian Studies Association of Australia. August 14. Available online: https://asaa.asn.au/tigers-vs-goats-rajiv-malhotras-battle-for/ (accessed on 23 March 2023).

- The Hindu. 2023. Indian -Americans Stage Peaceful Rally Against Legislation on Caste-Based Discrimination. April 6. Available online: https://www.thehindu.com/news/international/indian-americans-stage-peaceful-rally-against-legislation-on-caste-based-discrimination/article66705394.ece (accessed on 20 May 2023).

- The Print. 2018. RSS Ideologue Rakesh Sinha, Classical Dancer Sonal Mansingh among 4 Nominated to Rajya Sabha. July 14. Available online: https://theprint.in/india/governance/rakesh-sinha-sonal-mansingh-among-4-nominated-to-rajya-sabha/83133/ (accessed on 30 March 2023).

- Tian, Min. 2008. The Poetics of Difference and Displacement: Twentieth-Century Chinese-Western lntercultural Theatre. Hong Kong: Hong Kong University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Townsend, Robert B., and Norman Marshall Bradburn. 2022. The State of the Humanities Circa 2022. Dædalus: Journal of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences. Available online: https://www.amacad.org/publication/state-humanities-circa-2022 (accessed on 2 April 2023).

- Tull, Herman. 2015. Whence Sanskrit? (kutaḥ saṃskṛtamiti): A Brief History of Sanskrit Pedagogy in the West. International Journal of Hindu Studies 19: 213–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UCLA Center for India and South Asia. 2021. The Arduous Arts: Caste, History, and the Politics of Classical Dance and Music in South India. Webinar, January 11. [Google Scholar]

- UCR Department of Dance. 2022. Recast(e)ing South/Asian Dance and Performance. Colloquium, January 10–February 28. [Google Scholar]

- van Nieuwkerk, Karin. 2001. Changing Images and Shifting Identities: Female Performers in Egypt. In Moving History/Dancing Cultures: A Dance History Reader. Edited by Ann Dils and Ann Cooper Albright. Middletown: Wesleyan University Press, pp. 136–43. [Google Scholar]

- Vatsyayan, Kapila. 1967. The Theory and Technique of Classical Indian Dancing. Artibus Asiae 29: 229–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walker, Ayo. 2020. Traditional White Spaces. Journal of Dance Education 20: 157–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warren, Vincent. 2006. Yearning for the Spiritual Ideal: The Influence of India on Western Dance 1626–2003. Dance Research Journal 38: 97–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weinert-Kendt, Rob. 2021. Broadway Is (Finally) Embracing Black Writers. But the Work of Diversifying Theater Is Just Getting Started. America: The Jesuit Review. December 27. Available online: https://www.americamagazine.org/arts-culture/2021/12/17/broadway-black-writers-242031 (accessed on 23 March 2023).

- Wong, Sam, and Frank Swain. 2016. What Donald Trump Has Said about Science—And Why He’s Wrong. New Scientist. August 4. Available online: https://www.newscientist.com/article/2099977-what-donald-trump-has-said-about-science-and-why-hes-wrong/ (accessed on 17 March 2023).

- Wood, Leona, and Anthony Shay. 1976. Danse Du Ventre: A Fresh Appraisal. Dance Research Journal 8: 18–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yong, Li Lan. 2004. Ong Keng Sen’s Desdemona, Ugliness, and the Intercultural Performative. Theatre Journal 56: 251–73. [Google Scholar]

- Young, Patrick. 2008. From the Eiffel Tower to the Javanese Dancer: Envisioning Cultural Globalization at the 1889 Paris Exhibition. The History Teacher 41: 339–62. [Google Scholar]

- Zarrilli, Phillip B. 1995. Between Theory[es] and Practice[s] of Acting: Dichotomies or Dialogue? Theatre Topics 5: 111–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zazzali, Peter. 2016. Acting in the Academy: The History of Professional Actor Training in US Higher Education. New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Pillai, S. Kafka’s Ape Meets the Natyashastra. Arts 2023, 12, 173. https://doi.org/10.3390/arts12040173

Pillai S. Kafka’s Ape Meets the Natyashastra. Arts. 2023; 12(4):173. https://doi.org/10.3390/arts12040173

Chicago/Turabian StylePillai, Shanti. 2023. "Kafka’s Ape Meets the Natyashastra" Arts 12, no. 4: 173. https://doi.org/10.3390/arts12040173

APA StylePillai, S. (2023). Kafka’s Ape Meets the Natyashastra. Arts, 12(4), 173. https://doi.org/10.3390/arts12040173