Knickers in a Twist: Confronting Sexual Inequality through Art and Glass

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Repeal

3. History of Knickers

‘The division between male and female dress has been and remains fundamental to clothing design, and this distinctive apparel has played a central role in constructing gender difference. Clothing thus provides a rich arena in which to explore how masculine and feminine identities take shape and change over time.’

‘Whilst literature set about exploring the psychological nuances that show men and women are different and not just unequal, dress started to illustrate the physical side of this phenomenon. In short, the Middle Ages added sex to costume.’

‘The transition from open- to closed-crotch drawers, which was completed by the end of the 1920’s, reveals how modesty and eroticism, usually paired as opposites, work together in a shifting dialectic responsive to and productive of changes in understandings about gender difference and sexuality.’

‘Although—contrary to urban legend—no bras were burned on the Atlantic City Boardwalk at the 1968 Miss America Pageant protest, participants unfurled the new critical perspective they called “women’s liberation”, and feminism has been closely associated with undergarments in the popular imagination ever since.’

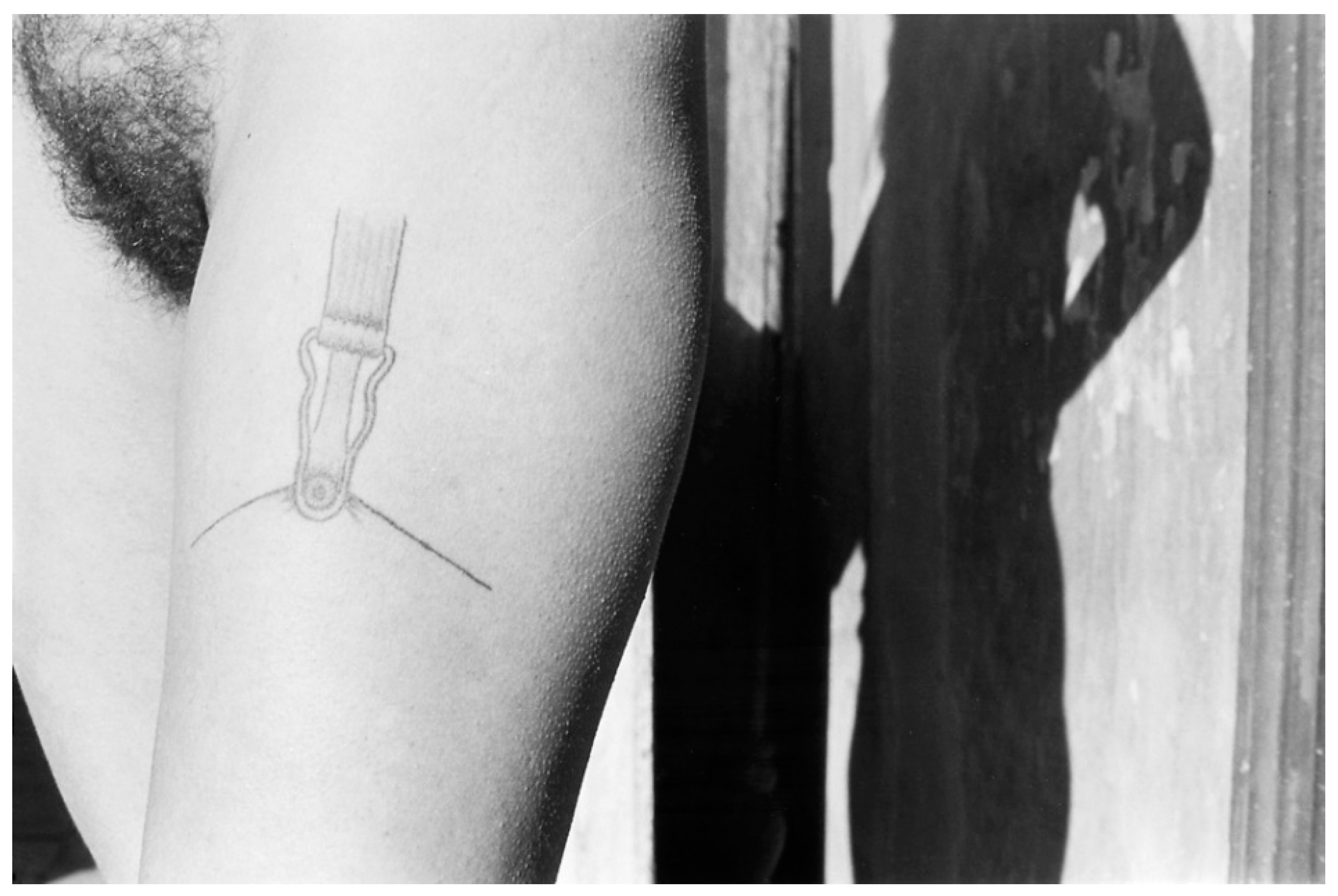

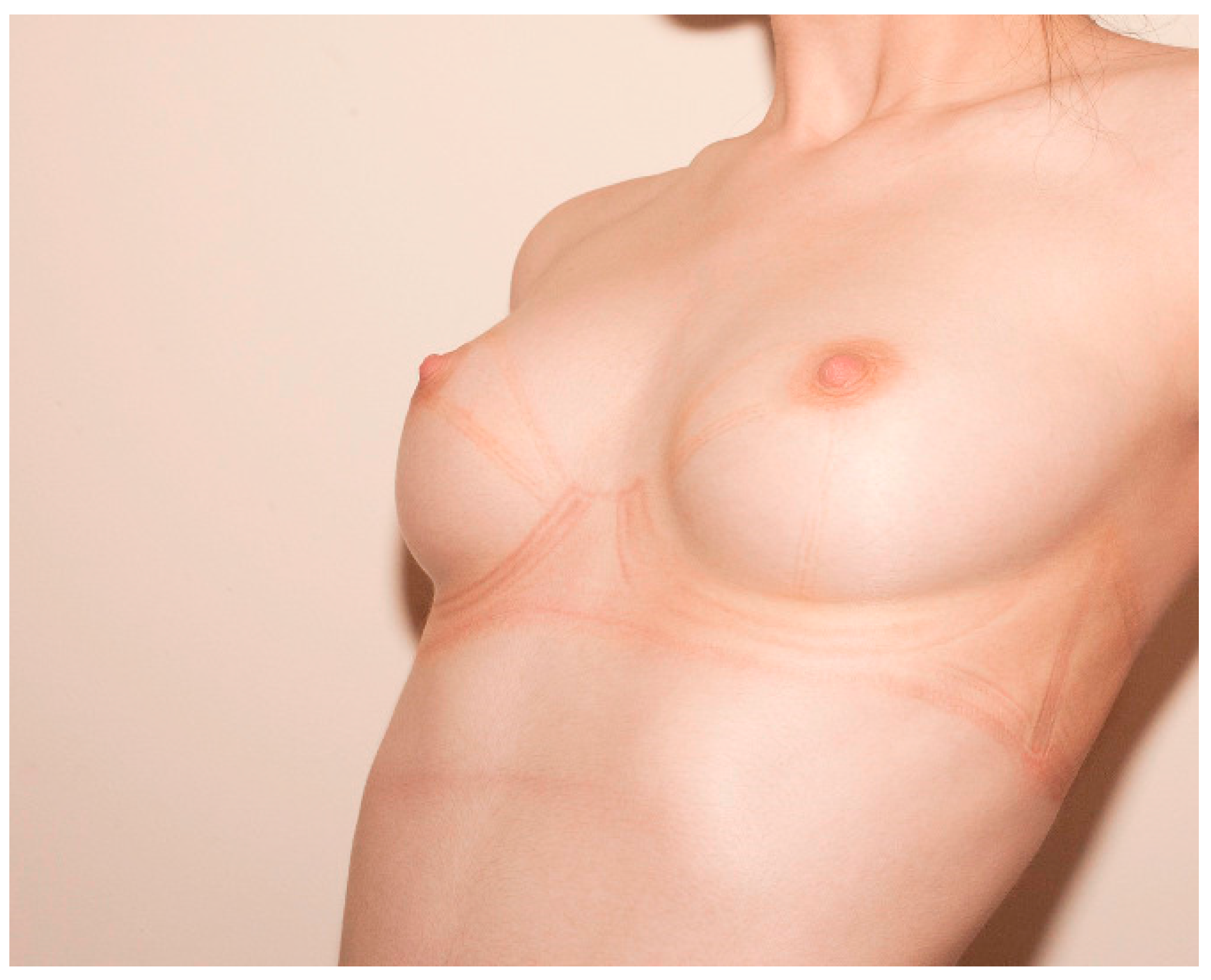

4. The Art of Knickers

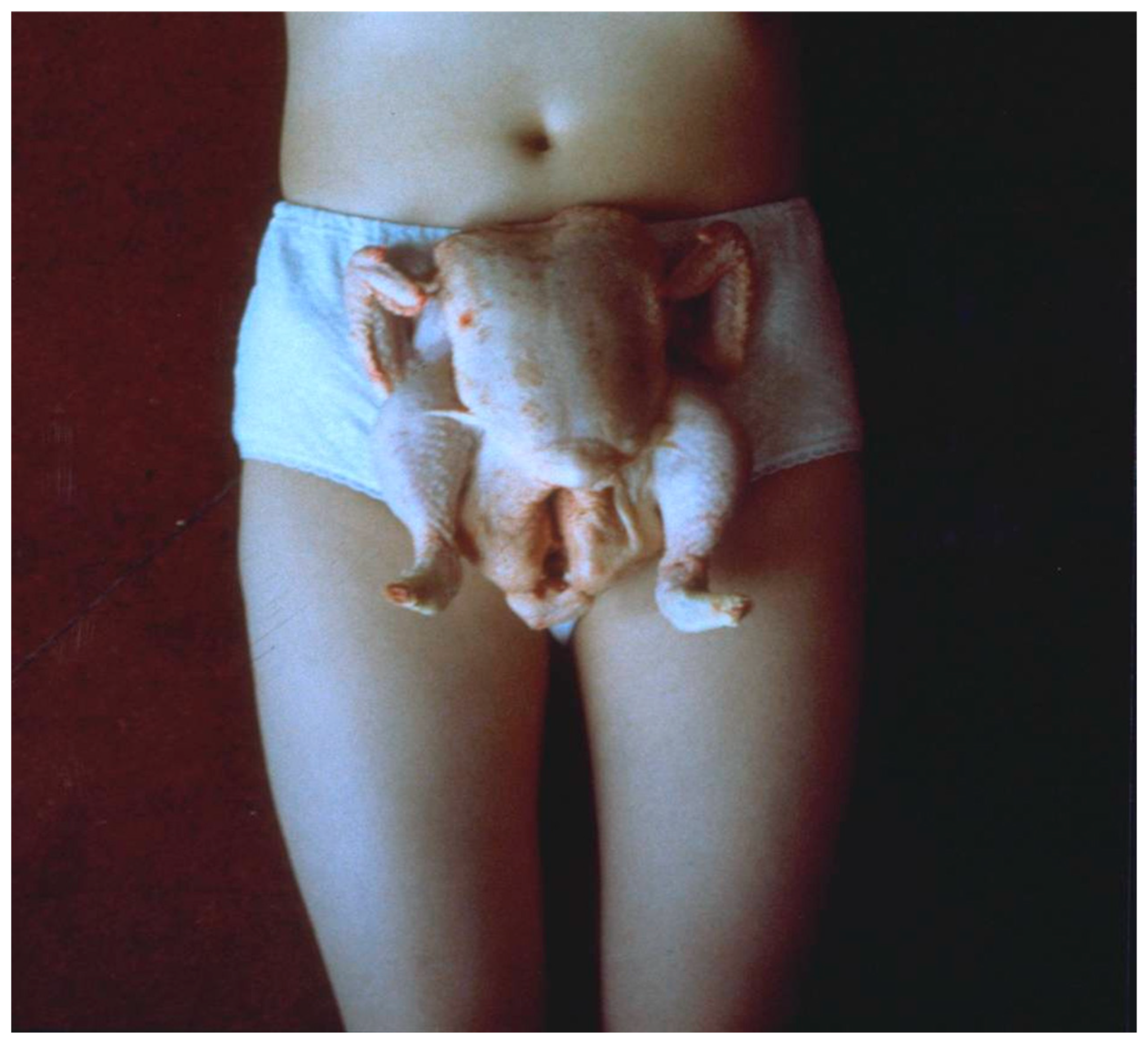

‘The presentation of the female genitals as equivalent to a chicken ready to be stuffed and cooked is disturbing and the composition of the image emphasises this narrative. The rest of the artist’s body is cut out of the frame so that the age and gender of the model is ambiguous, although the type of underwear worn suggests a young woman or girl. The body is surrounded by an intense darkness which heightens the scene.’

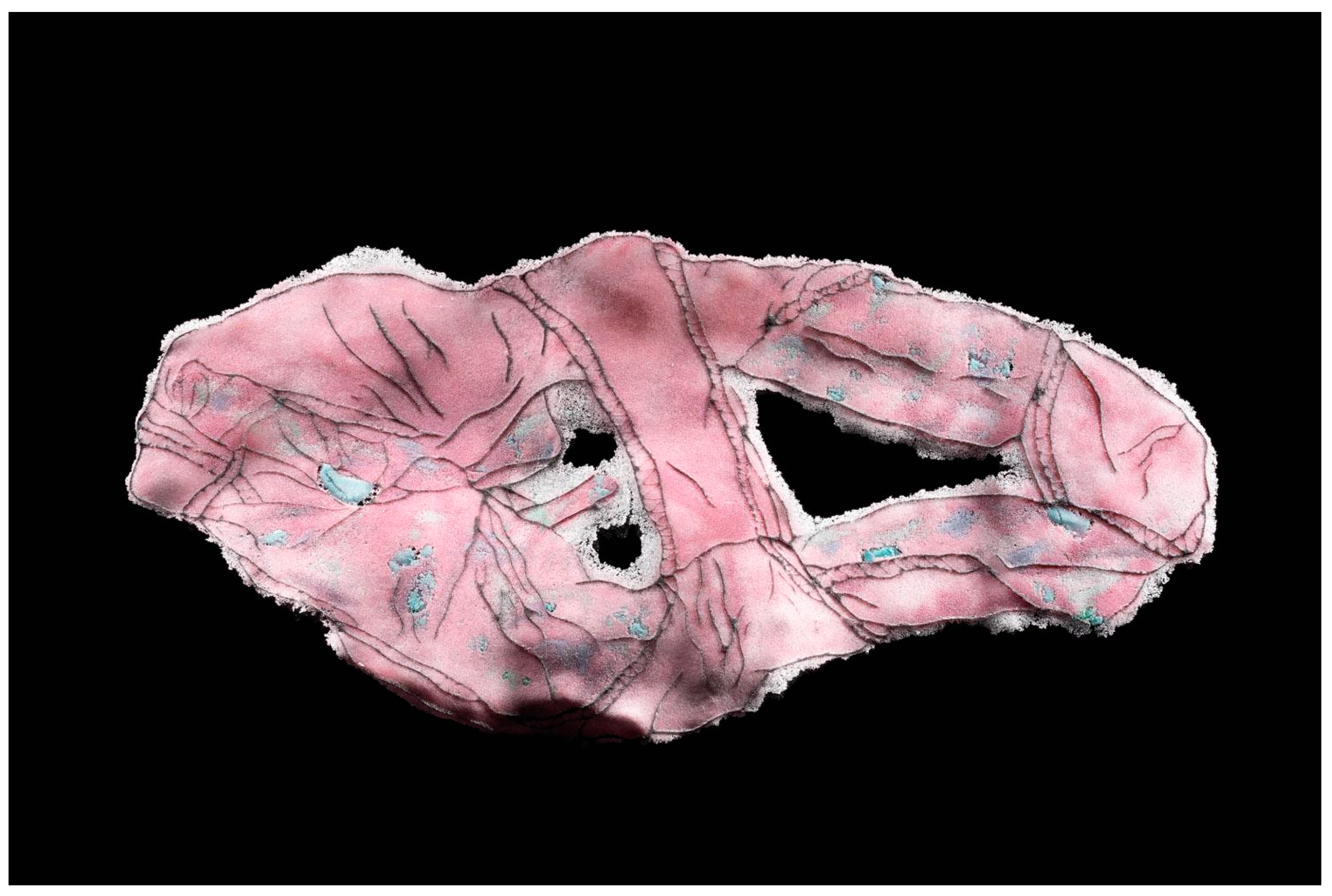

5. Material and Meaning

6. Let’s Hook Up

7. Moving Forward

8. Conclusions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- AG (SPUC) v Open Door Counselling Ltd. 1988. Bailli.org. Supreme Court of Ireland Decisions. Available online: https://www.bailii.org/ie/cases/IESC/1995/9.html (accessed on 5 May 2023).

- Bailli.org. 1992. Supreme Court of Ireland Decisions. (AG v X, 1992). Available online: https://www.bailii.org/ie/cases/IESC/1992/1.html (accessed on 5 May 2023).

- Bonfiglioli, Chiara. 2019. ArtLeaks Gazette #5: “Patriarchy Over & Out. Discourse Made Manifest”. Available online: https://issuu.com/artleaks/docs/artleaksgazette_5_w (accessed on 20 June 2023).

- Callaghan, R. Colleen. 2010. Bloomer Costume. In The Berg Companion to Fashion. Edited by V. Steele. New York: Berg. [Google Scholar]

- De la Haye, Amy, and Valerie Mendes. 2010. Fashion Since 1900. London: Thames & Hudson. [Google Scholar]

- Fields, Jill. 2007. An Intimate Affair: Women, Lingerie and Sexuality. Auckland: University of California Press. [Google Scholar]

- Gamman, Lorraine, and Merja Mackinen. 1994. Female Fetishism: A New Look. London: Lawrence & Wishart. [Google Scholar]

- Hatt, Michael, and Charlotte Klonk. 2006. Art History: A Critical Introduction to Its Methods. Manchester: Manchester University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Heller, Gallery. 2023. Available online: http://www.hellergallery.com/susan-taylor-glasgow/ (accessed on 21 June 2023).

- Irish Statute Book. 2023. Available online: https://www.irishstatutebook.ie/eli/1983/ca/8/enacted/en/html (accessed on 20 June 2023).

- Lucas, Sarah. 2015. Sadie Coles. Available online: http://www.sadiecoles.com/artists/sarah-lucas/exhibition-venice-2015/Sarah%20Lucas_press%20release.pdf (accessed on 2 June 2023).

- Manchester, Elizabeth. 2000. Chicken Knickers: Summary. Available online: http://www.tate.org.uk/art/artworks/lucas-chicken-knickers-p78210/text-summary (accessed on 25 June 2023).

- Marcoci, Roxana. 2010. Action Pants: Genital Panic. Available online: http://www.moma.org/explore/inside_out/inside_out/wp-content/uploads/2010/06/EXPORT_all.sm_.jpg (accessed on 20 May 2023).

- McDowell, Colin. 1992. Dressed to Kill: Sex Power and Clothes. London: Hutchinson. [Google Scholar]

- Phelan, Peggy, and Helena Reckitt. 2012. Art and Feminism: Themes & Movements. London: Phaidon. [Google Scholar]

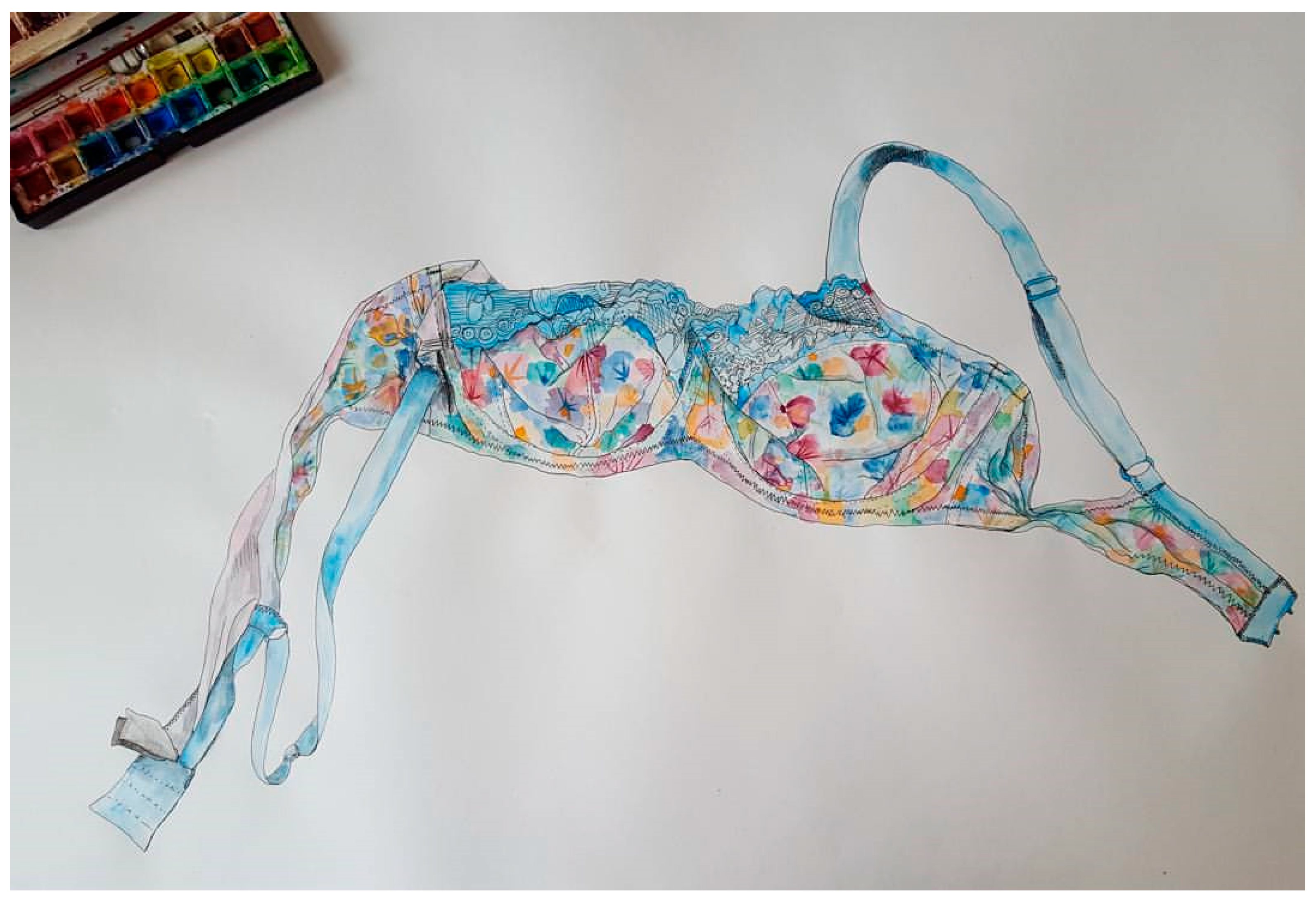

- Plunkard, Katie. 2015. Artist Statement. Available online: http://katieplunkard.com/glass-works/exhibition/unmentionables/ (accessed on 17 June 2023).

- Vanderbeke, Dirk, and Caroline Rosenthal. 2015. Probing the Skin: Cultural Representations of Our Contact Zone. Newcastle upon Tyne: Cambridge Scholars Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Saint-Laurent, Cecil. 1968. A History of Ladies Underwear. London: Michael Joseph. [Google Scholar]

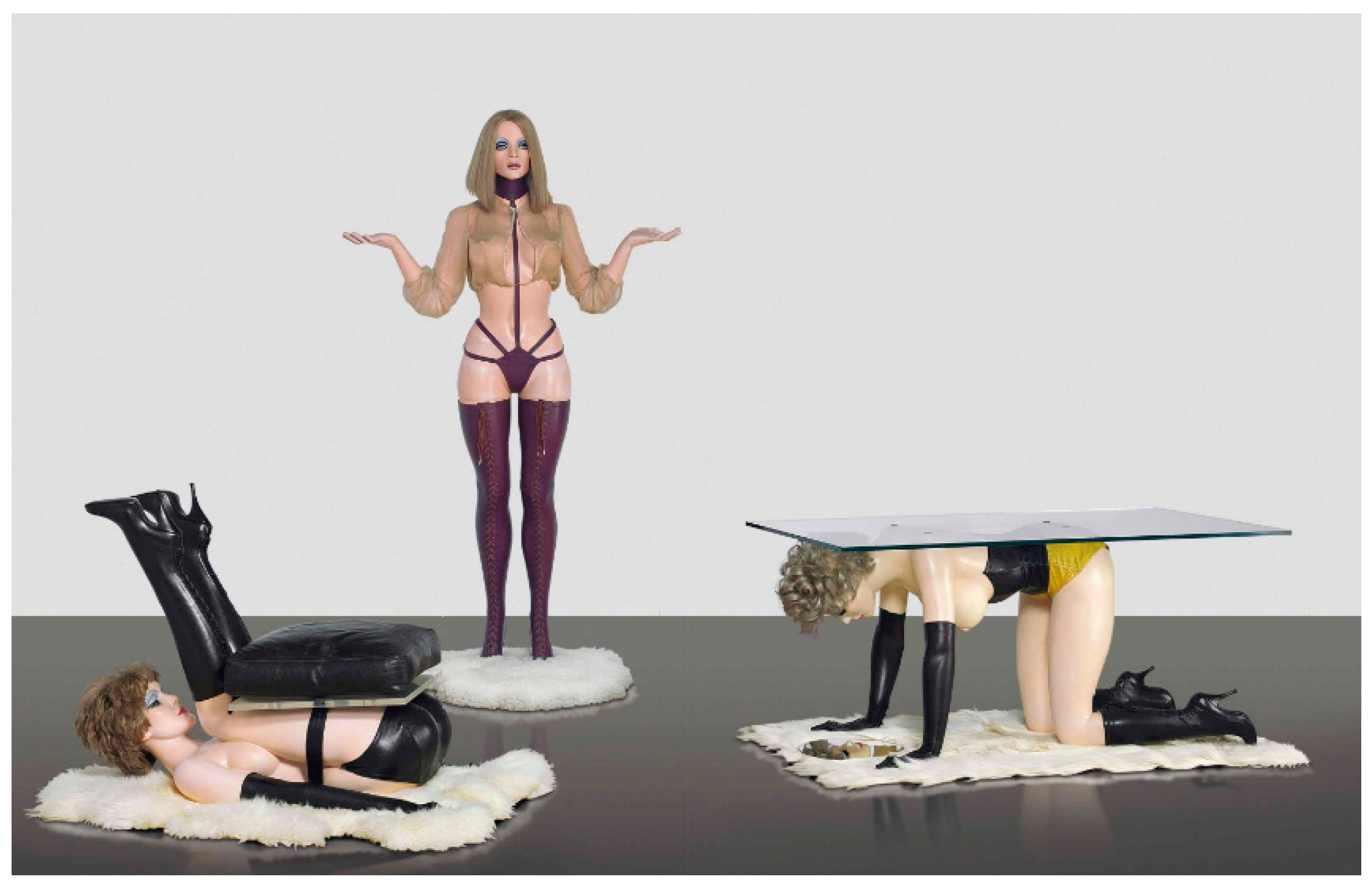

- Sladen, Mark. 1995. Available online: https://www.frieze.com/article/allen-jones (accessed on 27 June 2023).

- Speaking of IMELDA. 2023. Available online: https://www.speakingofimelda.org (accessed on 20 June 2023).

- Steele, Valerie. 1985. Fashion and Eroticism. New York: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Steele, Valerie. 2001. The Corset: A Cultural History. New Haven and London: Yale University Press. [Google Scholar]

- The Irish Times. 2014. Available online: https://www.irishtimes.com/news/crime-and-law/courts/high-court/court-clears-way-for-clinically-dead-pregnant-woman-to-be-taken-off-life-support-1.2048616 (accessed on 8 May 2023).

- The New York Times. 2018. Available online: https://www.nytimes.com/2018/05/27/world/europe/savita-halappanavar-ireland-abortion.html (accessed on 8 May 2023).

- UN. 2023. Available online: https://www.un.org/sustainabledevelopment/gender-equality/ (accessed on 2 May 2023).

- UN Women. 2023. Available online: https://www.unwomen.org/en/what-we-do/ending-violence-against-women (accessed on 1 May 2023).

- Walsh, Helena. 2020. Hanging Our Knickers Up: Asserting Autonomy and Cross-Border Solidarity in the #RepealThe8th Campaign. Feminist Review 124: 144–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Zhiyuan. 2023. Available online: http://www.wangzhiyuanart.com/3_artworks/4_artworks/4_artworks_10/4_artworks_10_1.html (accessed on 21 June 2023).

- Wroe, Nicholas. 2014. Allen Jones: I Think of Myself as a Feminist. Available online: http://www.theguardian.com/artanddesign/2014/oct/31/allen-jones-i-think-of-myself-as-a-feminist (accessed on 2 June 2023).

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Longwill, S. Knickers in a Twist: Confronting Sexual Inequality through Art and Glass. Arts 2023, 12, 160. https://doi.org/10.3390/arts12040160

Longwill S. Knickers in a Twist: Confronting Sexual Inequality through Art and Glass. Arts. 2023; 12(4):160. https://doi.org/10.3390/arts12040160

Chicago/Turabian StyleLongwill, Sophie. 2023. "Knickers in a Twist: Confronting Sexual Inequality through Art and Glass" Arts 12, no. 4: 160. https://doi.org/10.3390/arts12040160

APA StyleLongwill, S. (2023). Knickers in a Twist: Confronting Sexual Inequality through Art and Glass. Arts, 12(4), 160. https://doi.org/10.3390/arts12040160