Abstract

Photography evidences presence, but what does it present? This article explores the notion of magic in photography through Deleuze and Guattari’s concept of ‘haecceity’, Jacques Derrida’s logic of the ‘supplement’ and Jean-François Lyotard’s ‘inhuman’. The sections ‘The Zone of Photography’, ‘Ghosts in/of the Machine’, ‘The Crypt and Encryption’, ‘Affect-Event-Haecceity’ and ‘Magic, Consumerism, Desire’ consider how photography provides a ‘zone’ that encrypts the desires of its photographer and viewer. A photograph, in its various forms and appearances, from scientific instrument to personal documentation, bears our need and desire to be affected. The photographic zone can connect with the anxiety, fear, grief, and ha ppiness that are latent within the irrationality of its viewer. The photography is never past as it continually unfolds into, and is entangled with, the fabric of the present. Through consideration of photography we will consider how magic does not happen to people but people happen to magic. We desire magic to appear.

Keywords:

photography; magic; haecceity; ghosts; Jacques Derrida; Jean-François Lyotard; Deleuze; Guattari 1. Introduction

The word ‘magic’ appears in many forms across photography. Technical guides promise insights into creating the ‘magic’ of illusion and beauty; undergraduate degree applicants commonly describe an enchantment conjured from their first encounter with the medium; fine art photographer Jeff Wall described photographic ‘scale [as] a kind of magic’; Victorian spiritualists, scientists, occultists, amateurs and intellectuals all sought to harness photography’s possibilities for glimpsing hitherto unknown forces in other dimensions and forms of existence; a foremost Hollywood visual special effects company is called ‘Industrial Light and Magic’; Charlotte Cotton’s essay in the book Photography is Magic (Cotton 2015) proposed a broad equivalence of the phenomena of ‘wonder’ between the two terms of its title; the recurrence of ‘ghost in the machine’ cinematic narratives provides ongoing popular mass entertainment as other-worldly forces disrupt the seeming normalcy of suburban conventions and behaviours, manifested through glitching video and photographic images, thereby disrupting the supposed rationality and stability of digital binary code and algorithm structuring contemporary image production. The appearance of ‘magic’ in these varied examples are connected by photography’s function in the supra-, sur-, or preter- dimensions of reality and our experience of it: ‘magic’ emerges as a quality, in these prefixes, as over, above, beyond, earlier relative to rational horizons of experience. So what are we to make of this phenomena that is both elusive and present, whose appearance is outside of, but dependent upon, rational experience to appear? Photography presences something, but of what is it a presentation?

2. The Zone of Photography

Despite the reappearance of ‘magic’ in aspirations and fantasies related to photography, conventional explanation of photography’s most fundamental operations omits the word. Photography tends to be described either in scientific language—the lenticular refraction of a small bandwidth of electromagnetic radiation (i.e., visible light) recorded upon a surface such as film or a sensor whereupon a chemical or digital response produces a perspectival simulation of human perceptual experience—or as an artistic medium used to image the thought of its wielder. An etymological explanation is also commonly employed to describe what photography ‘is’: a ‘light’ (Greek ‘photos’) ‘writing’ (-graphe). This characterisation of the process, of ‘light-writing’, is suggestive of either a ‘natural’ act of light inscribing itself or of the photographer writing with light. No common description really admits and accounts for the possibility of ‘magic’ in photography, despite a long-imagined relationship with the medium. Perhaps, as we shall consider, the emergence of ‘magic’ occurs in the moment whereby one dimension of experience is encountered within another, where lived experience is re-presented within the zone of an image.

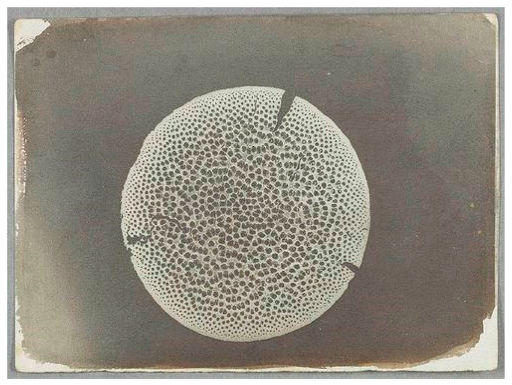

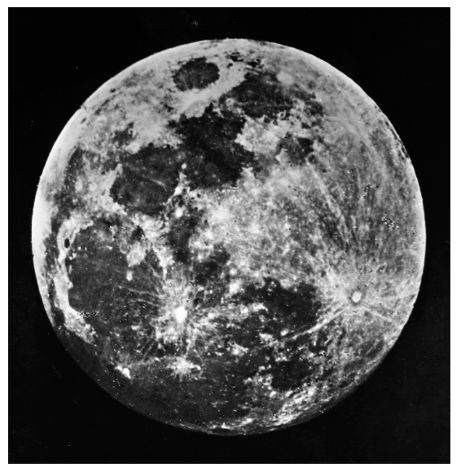

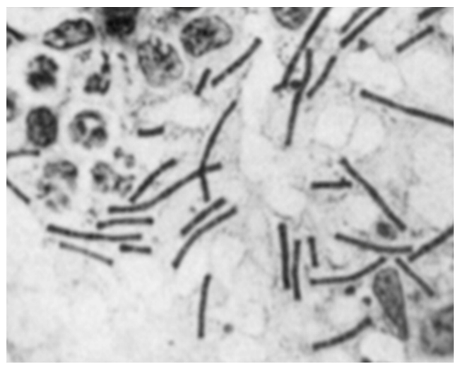

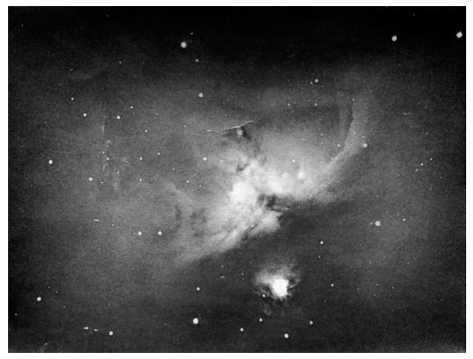

One of photography’s appeals lies in promising that which the human body cannot itself produce. It offers a prosthesis for vision and memory, and as a visual media, something that can be reproduced and seen by others. These possibilities exist in the photographic image from the Cubiculum Obscurum (Camera Obscura) to contemporary image-making. As we shall explore, photography does not simply replicate reality, but it provides a ‘zone’ of experience; it is not the experience of that which it depicts but instead a site, a zone, through which something can be experienced. In other words, it is an experience of an experience, perhaps a mediated experience of that which cannot be encountered. For example, 19th century photography, microphotography, astrophotography, and cinematographic vision machines all extended, expanded, and intensified perception to the degree that one could only experience the image since its referent (the object imaged) was either imperceptible or barely visible, from bacteria to the surface of the moon. If the definition of the word ‘magic’ is derived from its appearance in the late 14th century to describe super-natural phenomena, the very term is dependent upon what is constituted by, or what is understood as, ‘natural’. Perhaps one definition of magic might therefore be the experience of forces beyond the horizon of rational human perception. The experience of early photographic technologies occupied such a space. In the darkened chamber, the Cubiculum Obscurum set the theatrical conditions of a spectacle into which an ephemeral, expanded image of an exterior appeared within an interior. The process was optical, but the phenomena and experience of it was one of wonder. Is ‘magic’ not the process by which the world is re-presented whereby hitherto concealed dimensions of reality are revealed? This notion might help explain how entertainment is synonymous with magic: the performance of revelation recontextualises what is, otherwise, a scientific demonstration of optics through the gestures of presentation associated with theatre and spectacle.

|

| Henry Fox Talbot, Microphotograph of a plant stem, c.1840. |

|

| John Draper, Early image of the moon, 1840. |

|

| Robert Koch, Microphotograph of bacteria (anthrax), 1877. |

|

| Andrew Ainslie Common, Orion Nebula, 1883. |

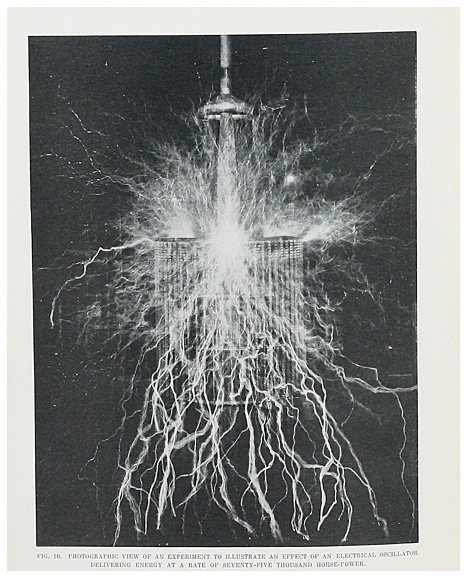

The entanglement of photographic advances across categories of science, magic and theatre reoccurs throughout photographic history. For example, the accidental discovery of X-rays by Wilhelm Röntgen in 1895 reflected the 1558 Cubiculum Obscurum in particular ways. Rather than the ‘dark chamber’ harnessing the projection of light through a biconvex lens, that imaged the exterior world into an interior vault (reflecting the meaning of the Latin word ‘camera’), X-ray photography also formed an image within the room, but without a lens. It was a profound moment in the development of science and medicine, but it was also experienced as both magic, paranormal, gothic, and entertainment (see Slevin 2022). Indeed, the Latin word ‘obscurum’ also means dark, or darkness, shadowlike, or indistinct. The first innovators of X-ray equipment were not just scientists and doctors but exhibition entrepreneurs that believed X-ray technology would be the spectacular future of visual entertainment. Thomas Edison promoted both public X-ray demonstrations and cinema screenings, whilst showbusiness trade journal advertisements evidence how exhibitors, seeking to anticipate the future of entertainment spectacles, attempted to exchange film projectors for X-ray equipment (see Gunning 2008, p. 52). Like the experience of the Cubiculum Obscurum, or cinematic projection, the X-ray provided an illuminated screen by seemingly intangible forces. It was a thoroughly modern technology whilst remaining in ‘the realm of fantasy or magic’ (Gunning 2008, p. 53). New visual technologies—from X-rays, photography, chronophotography, the stereoscope and stereograph, kaleidoscope, zoetrope, phenakistoscope, film projection, micro-, and astro-photography—produced radical modern experiences of space and time as the world-as-image was expanded, contracted, intensified, magnified, and reorganised.

|

| Wilhelm Röntgen, ‘Hand mit Ringen’ (X-ray photograph of Anne Berthe Röntgen), 22 December 1895. |

|

| Nikolai Tesla, ‘Photographic View of an Experiment to Illustrate an Effect of an Electrical Oscillator Delivering Energy at a Rate of Seventy-Five Thousand Horse-Power’ in The Problem of Increasing Human Energy, 1900. |

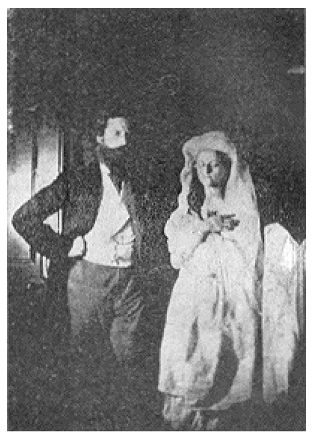

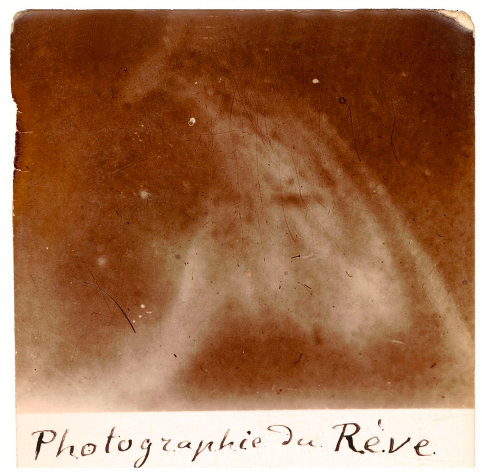

Photography’s relationship to ‘magic’ can indeed be historically located within other, early photographic cultures. Photography’s appeal to that beyond perceptual reality was clearly evident in the practice of scientists, engineers, and amateurs for whom the paranormal and parascientific was a legitimate field of research. Well-known figures included William Crookes (the ‘Crookes tube’ was instrumental in the discovery of X-rays) who attempted to scientifically validate paranormal activity, concluding the objective existence of a ‘Psychic Force’ derived from one’s soul or mind. Indeed, ‘spirit photography’ was a well-known and popular activity that synthesised, and seemingly evidenced, supernatural beliefs through modern technology. There are numerous examples that testify to the cultural entanglement of science and spiritualism, technology and magic. One such example includes the famous inventor and engineer Marconi who, whilst innovating wireless telegraphy and radio, also aspired to develop a technology that received the sounds of the dead. After the discovery of X-rays, for example, other ‘respectable’, prominent figures claimed the existence of the paranormal through photographic ‘evidence’. The French Commandant Louis Darget discovered ‘thought photography’, whereby the photographic image recorded invisible ‘V-rays’ that were projected from the human soul. The physicist Prosper-René Blondlot claimed the existence of ‘N-rays’, whilst the neurologist Hippolyte Baraduc produced photographic images of the human soul, influenced by Baron Carl von Reichenbach’s concept of the existence of ‘Od-rays’.

|

| William Crookes and the medium Florence Cook, c.1874. |

|

| Louis Darget, ‘Photographie du Rève (Dream Photography)’, 1896. |

The uses of photography to entertain the possibility, or even claim validation, of the paranormal indicates something profound about the medium. Photography has clearly been burdened by the demands placed upon it to function as a medium of evidence: photography is very rarely an image of itself, but rather is an instrument towards something other. John Tagg (1988) argued that photography has no history or identity belonging to itself. Instead, photography’s history is dispersed across the many fields, agencies and uses that instrumentalise photography: ‘Its status as a technology varies with the power relations which invest it. Its nature as a practice depends on the institutions and agents which define it and set it to work. Its function as a mode of cultural production is tied to definite conditions of existence…Its history has no unity.’ (Tagg 1988, p. 63). Photography’s appeal to its many users lies in its indexical relationship to optical perception: ‘seeing is believing’. However, the medium has a long, overemphasised affinity to ‘truth’, and to return to the question asked in the introduction—of ‘what is photography a presentation?’—we might begin to answer that it is less a presentation of that which was in front of the lens, and more to do with that lying behind, and viewing it. The above examples of spirit and psychic photography testify how the camera’s image is used to manifest dimensions of desire in both its operator and viewer. If magic is possible, it is in the desire of the magician to present and in the moment of the audience’s desire to suspend its disbelief to glimpse something ir-rational, supra-real or para-normal. Desire is projected and inscribed into photography’s zone.

3. Ghosts in/of the Machine

Towards the end of the twentieth century, the thinker Jean-François Lyotard argued that human experience had been consumed by, and reproduced, the broader cultural dominance of ‘industrial and post-industrial techno-[science], of which photography is only one aspect’ (Lyotard [1988] 1991, p. 122). As we shall see, the ‘magic’ photography seemingly offered, through the expansion and enrichment of perception and experience, has produced a different type of ghost in the machine. The human race has constructed prosthetic technologies—from written language to machines and A.I.—to provide external bodies through which to present and retain thought. Whilst these external, ‘artificial’ bodies replicate experience (photography’s relationship to vision for example), for Lyotard they are inhabited by ghosts. Images can never fully articulate the experience that they represent. As Jacques Derrida ([1972] 1991) reasoned, a sign that completely accorded with its object of representation would not be a sign but the thing itself. And, perhaps by extension, we might argue that any technology that could fully embody human experience would be human itself. Instead, the prosthetic mechanical reproduction of vision is described as ghostly, the photographic image a form of ‘techno-science’, when perceived as diminishing the fullness of embodied experience.

Lyotard reflected that culture now relied upon photography and media as fundamental to its experience and operations. He hypothesised an ineluctable posthuman world whereby all history, all experience, ‘will end up as no more than pale simulacra’ (Lyotard [1988] 1991, p. 11), and, in the face of human extinction, knowledge and experience will effectively be discontinued in its human form as it will be required to take other, post-human, inhuman bodies (i.e., machines, code, media) to survive. The moment experience loses the condition of its embodiment—the gendered human body in his example—it becomes something different. We already, arguably, live in a posthuman world: machine-thinking and technocracy are examples of structures for organisation and knowledge derived from human concepts, but significantly elide something fundamental about the very condition of being ‘human’. Lyotard’s question fundamentally asks what survives in humanity’s effort to replicate itself in forms of other media, for it is no longer itself. As we shall explore further in the next section, visual media presents a simultaneous expansion, and profound incompleteness, of perception. For Lyotard, it is the form and structure of the media that is replicated instead of its content. Essentially, without the body that created the experience, ‘thought’ is transformed into representations through another body: ‘a poor binarized ghost of what it was beforehand’ (Lyotard [1988] 1991, p. 17).

The appeal of magic and spectacle, the presence of ghosts in the machine, inhabits something of Jacques Derrida’s logic of the ‘supplement’ (Derrida [1967] 1998), whereby something adds to an existing state of things but eventually becomes an integral aspect of it: the supplément is both addition, completion, and replacement. Photography’s profound appeal lies in supplementing, or augmenting, vision. But, supplementation of experience can become supplantation. Derrida considered the example of ‘writing’ as a means of communication that first supplemented speech but took on a privileged status whereby it came to complete and guarantee what was spoken. Another example might be a fetish: for Freud, it might initially supplement desire but becomes the desired object. We could extend this notion of the supplement today to consider how smartphones have altered aspects of experiences that they, perhaps, once supplemented. As technology supplements our bodily abilities, it also affects the terms of our embodied experiences, and may also supplant it. We already rely on the technological bodies of media over our own embodied experiences. Recent psychological studies propose that the use of media impairs the very memory of the experience that it promised to guarantee (Tamir et al. 2018), through reframing and altering our perceptual attention (Diehl et al. 2016), and even ‘outsourcing’ and removing memories from ourselves as we deposit them into media storage (Sparrow et al. 2011). In other words, we don’t have to remember because it is recorded and remembered by an/other body of visual media. This is a form of ‘transactive memory’. One of photography’s magical appeals might lie in its ability remember for us, to conjure that once forgotten, but that gift may also be a curse; Lyotard clearly advocates for the memories produced by his own experiences through denigrating their existence within media. Indeed, another of photography’s ‘magical’ qualities is the ability to share the visuality and immediacy of our experience of events, even across the globe and beyond. However, it has also been shown that the intention to share an experience photographically can profoundly position us outside of the very event we are experiencing (Barasch et al. 2018). Garry Winogrand’s famous declaration ‘I photograph to see what the world looks like in photographs’, for example, is a deeply altered relationship towards experiencing.

Through photography’s condition as an external prosthesis and form of transactive memory, we remember things because photographs have evidenced them and enable a form of recall that can be profoundly affecting. I happen upon images—on social media, in forgotten computer folders, or an envelope at the back of a drawer—that both affect and disturb me. (‘How had I completely forgotten this moment?’, ‘I don’t even remember taking this photograph.’) My own powers of memory are exposed as utterly fragile given such moments are no longer otherwise recollected, although in the process of transactive memory, perhaps I do not remember because I knew the photograph would remember for me. Photographs are a supplement to memory, but they also have the potential to supplant it. Indeed, photographs can transform and generate new memories through our absorption of external images into internal memory narratives (see Garry and Gerrie 2005; Wade et al. 2002). However, to use this as a critique of photography and media is to over-privilege the coherency and constancy of our own memory. Lyotard may denigrate media as a ‘poor binarized ghost’, whereby his term ghost signifies a lack, but we should also perhaps consider how ‘poor’, inconstant and formless the very conditions of our own vision and memory are, themselves. My own embodied memories and experiences inhabit me like ghosts: I cannot recall the fullness of a past experience, nor can I even fully grasp the present moment in the moment of its passing. Whilst historical correlation seems vague, perhaps also it is no coincidence that the invention of photography emerged at a particular moment whereby the emerging 19th century human sciences turned in upon the body as the subject of its enquiry, only to discover the instability and impermanence of human vision and memory (see Crary 1990; Foucault [1966] 2007).

We might therefore argue that the ghost of the machine, whilst Lyotard frames this negatively, also contains an element of how ‘magic’ might inhabit photography. Photographs conjure. Ghosts are associated with lack, and in photography, an inability to bear fuller witness to experience. But we might also consider that the ghost embodies that which endures; it is a residue, or remainder, in the operation of transforming one regime of experience into another. In photography, it is the process of transforming embodied perception into an image—one organisation of matter (or body) into another. Lyotard’s use of the word ‘ghost’ is significant given the discussion of photography and magic’s affinity to the supernatural. Indeed, a ghost is not entirely without a body, and whilst it mirrors an anxiety around ‘lack’ when compared to living bodies, it is nevertheless a form of existence. However, the zone to which the ghost belongs is experienced as haunting or a disruption, an overflow, of the condition that formed it. Yet the etymology of ‘preternatural’ draws upon preter- for ‘beyond’ and ‘over’, which is derivative of the Latin prae- meaning ‘in front of’, ‘before’, and ‘across’. ‘Preternatural’ therefore has a quality of being before, prior, and across that understood as ‘natural’. We commonly consider ghosts to be symptoms of events, perhaps traumatic or unresolved circumstances, and occupying of a state of being ‘in between’. However, etymologically speaking, it is possible that it already exists in and through things. Perhaps the ‘preternatural’ has a quality of being prior to what we understand as ‘natural’; something psychic, or haunting, is already inscribed into our concepts of the natural. We shall consider this further as we discuss the limitations of ‘rational’ constructions of ‘nature’ to articulate human experience and the possibility that something preternatural is already embedded within it.

4. The Crypt and Encryption

It is a common choice to photograph a moment instead of experiencing it. If a photograph provided such a poor return from the ‘fullness’ of experience, its mass appeal might be more diminished. There are, perhaps, two entwined reasons, amongst others, why we choose to enframe a moment. One is, as mentioned above, produced from an anxiety over the intangibility of my experience becoming-memory. In other words, a photograph will provide a transactive body through which I can return and remember. Another reason is that the photograph is an exterior zone of encryption that I can share, and remember, with others. Therefore, I desire to store my experiences into an exterior prosthetic body to function as a more reliable, and shareable, memory. Externalising and disseminating a moment beyond myself more fully guarantees its existence since the transactive process multiplies with those who witness the photograph. Therefore, whilst Lyotard raised the spectre of the ‘ghost’ in terms of photography’s diminished form of reproducing life, photography, instead, might also represent a technological augmentation for experience and memory that appeals precisely because the very essence of human memory and identity belongs to the realm of ghosts itself: intangible, elusive, without material presence, irrational. We desire a greater permanency to our existence, even if that desire derives from anxiety.

The ‘zone’ of photography is a spatio-temporal zone. The ‘past’ can be perpetually refolded back into the stream of present experience. Consider someone revisiting old photographs in a family album in the present, or, how Facebook’s ‘On this Day’ feature repeats each anniversary of a photograph’s upload into the experience of the current day. (Almost always I experience pleasure in the revisitation of this ghost as I can barely recall taking and uploading an image that I once thought significant enough to share). One of photography’s profound appeals lies in its ability to unfold into multiple, futural, experiences. It offers another body, or zone, into which experience is reorganised. We may even mourn the loss of a photograph in some ways to the loss of a person. To lose a photograph, or a zone into which we placed experience beyond ourselves, is traumatising since, to refer to the concept of transactive memory, I have lost myself, or at least that part of me placed in another. Lyotard ([1988] 1991, p. 17) might describe this as an ‘artificial thought’. However, it is in the artifice of the image that photography elides fundamental qualities of human perception whilst extending other elements of it. The preternatural dimension of photography’s ghost is its capacity to be a simultaneously diminished and prolonged presence—its magic is to extend human experience into other forms of existence.

Therefore, whilst photography presents a form of diminishment, its zone also presents an appeal. In their editorial provocation to elicit responses around photography’s relation to magic, Baird and Hall refer to the Cubiculum Obscurum, a nascent form of photography, as a ‘staged scenario, affectively experienced as both real and magical’. Like a ‘scenario,’ the photograph does not usually draw attention to, or reference itself, as the subject. By eliding the condition of its own production, a photograph is usually an image of something that is not itself (exemptions might include fine art or ‘new’ documentary photography, for example). The photograph, however, provides a structure, an en-crypt-ion of visual experience. The word ‘crypt’ derives from the middle English ‘cavern’, and we might consider the image produced by the Cubiculum Obscurum, through to the camera, as a crypt, as a type of a cave into which an image is formed. It draws itself from the world outside, yet it can only exist through its separation from that which is outside of it. The etymology of ‘cavern’ derives from the Latin crypta, following the Greek words kruptē (‘a vault’) and kruptos (‘hidden’). As with the properties of a vault, or crypt, the ‘zone’ must be both connected to, and separated from, the world in which it exists. Vaults and crypts in stories are commonly sites of magical and supernatural significance containing something beyond, or unbearable for, the world that required such a space to exist.

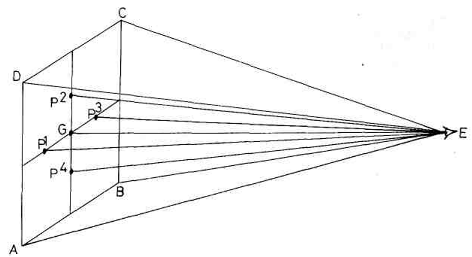

How, and in what ways, does a photograph take the form of encryption? The perspectival configuration of time and space is a pictorial encryption of vision that organises experience and knowledge according to specific structures. Immanuel Kant perhaps articulated this most succinctly: our forms of representation do not mirror reality, but reality ‘conform[s] to our mode of representation’ (Kant [1786] 1968, p. 19). We considered briefly how language obeyed the logic of the supplement; in photography, we should invert the title of Henry Fox-Talbot’s pioneering photographic publication The Pencil of Nature of 1844 and instead consider photography’s nature of the pencil. The totality of ‘reality’ is fundamentally unknowable, but our experience of it is knowable, as it depends upon, and follows, the conceptual and representational frameworks that we apply in order to create meaning. Post-structuralist thinkers have clearly demonstrated how our language provides the concepts through which we experience reality. Let us consider the dominant configuration of space within lens-based media—the ‘language’ of geometric perspective. Despite appearing as the ‘pencil of nature’, the perspectival order within photography is itself a cultural system of encoding vision; it is not reality itself. Martin Kemp discusses how the ‘classical space’ of perspectival organisation emerged from a particular cultural context of Renaissance Florentine culture and the growth of practical mathematics within a mercantile society, civic life, and Ciceronian humanism (Kemp 1990, p. 14). Essentially, the emergence of this culture aspired towards measurement and assessment, rational methods for judgement and measurement. For Kemp, the production of perspective as a method for encoding space and time ‘was deeply locked into the system of political, religious and intellectual values’ (Kemp 1990, p. 14). As perspectival systems disseminated over time, and across Europe, so it was gradually freed from theology, became secularised and embedded into what the art historian Erwin Panofsky describes as a ‘worldview’ (Panofsky [1927] 1991, p. 70).

|

| Leon Battista Alberti, from On Painting, 1435. |

In first-person perspective, space and time is orientated around the position of the ‘viewer’, presented as a disembodied optic around which the visual field revolves. The particular organisation of matter reflects Michel Foucault’s identification of ‘a general ordering of nature…[through] entire systems of grids which analyse the sequence of representations…and redistributing it in a permanent table.’ (Foucault [1966] 2007, pp. 330–31) Representational frameworks are fundamental to how humans relate to, understand, and extract from an imagined exterior reality. But it is also true that knowledge reproduces the contingent principles upon which it is generated. In other words, ‘reality’ is produced by the way we think. As Kant wrote, ‘the observation itself, alters and distorts the state of the object observed’ (Kant [1786] 1968, pp. 20–21). However, geometric perspective remains a culturally dominant system for organising and ordering matter. Artists and movements, from Leonardo da Vinci to Cubism and Futurism, have challenged the ontological validity of an image’s perspectival structure, but these critiques remain historical footnotes to its dominance.

Edmund Husserl argued that geometry is not innately natural, but has become a ‘supratemporal’ language: it orders time and space whilst existing outside of it (Husserl [1936] 1989, p. 60). We might consider this to be another example of Derrida’s logic of the supplement since it originated as a method of illustration and calculation but has supplanted experience of reality through being embedded into Western systems of thought. For Husserl, geometry ‘overcoded’ other forms of knowledge, especially as its system could be universally applied and could be reiterated. He wrote that, as a supra-temporal system, its iterability was embedded into the foundations of cultural thought: ‘what perhaps emerges with greater and greater clarity there belongs the possible activity of a recollection in which the past experiencing [Erleben] is lived through in a quasi-new and quasi-active way’ (Husserl [1936] 1989, p. 163). Panofsky similarly described perspective as ‘a rational and repeatable procedure’ (Wood [1927] 1991, p. 13). The perspective inherent in a photograph reproduces the cultural and historical logic of rational, quantitative conceptual ordering of space within time.

Panofsky argued that the ‘ancients’ purposely rejected perspective as a form of representation, believing that it introduced ‘an individualistic and accidental factor into an extra- or supersubjective world’ (Panofsky [1927] 1991, p. 71). Perspective is premised upon anthropocentrism as it organises the world around a centralised, privileged spectator. (Indeed, deconstructing the disembodied central optic of perspective was a critical principle of modernist avant-gardes.) However, not all cultures evolved perspective as a form of representation. It is a system of encryption and not something innately natural. When shown a perspectival image, the Ethiopian Me’en tribe only gradually began to decipher pictures of familiar animals by identifying recognisable fragments. A different tribe could not initially recognise a horse but began to connect pictorial elements when presented with an actual horse (Prinz 1993). It was reported that Australian aborigines believed birds, in perspectival organisation, were mutilated given the incomplete representation of their limbs (Gombrich [1960] 1968, p. 119). These examples suggest that geometric perspective is not innate to humans, but is a culturally-inculcated organisation of separate objects into a particular regime of time and space, that fundamentally relies upon the culturally-produced concepts of distance and disconnection between things. As Hubert Damisch writes, echoing the earlier quote by Kant, people ‘learn to see an image in perspective, instead of seeing’ (Damisch [1987] 1994, p. 10). Western geometric perspective, upon which its visual media is structured, conceptualises an organisation of the world upon inherent conditions of alienation, difference, and anthropocentrism.

|

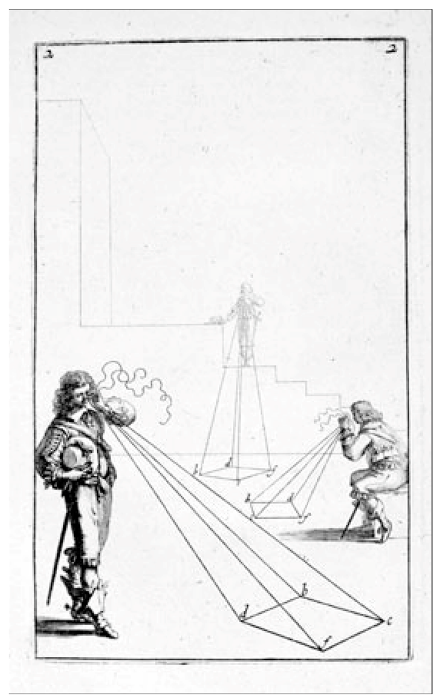

| Abraham Bosse, ‘Les Perspecteurs’ (‘The Viewers’), 1647–8. |

One final example returns us to the realm of the preternatural. Ernst Gombrich argued that Western observers could not decipher hieroglyphs because the Egyptians ‘shunned’ the use of three-dimensional representation and instead created ‘pictograms’ that depended upon a different perceptual framework: ‘We must never forget that we look at Egyptian art with the mental set we have all derived from the Greeks…. Nineteenth-century observers frequently made this mistake…. We are accustomed to looking at all images as if they were photographs or illustrations’ (Gombrich [1960] 1968, p. 104). In this example, those Western observers inculcated into perspectival regimes had to learn to ‘see’ another culture’s organisation of experience. Egyptian concepts were profoundly different. For example, the dead were depicted as simultaneously present with the living and ‘[t]he word ‘magic’ in such context explains too little’ (Gombrich [1960] 1968, p. 105). Indeed, the dead are not absent from our experience of the world but live preternaturally—existing before and across us; more generally, the past unfolds and exists as the present, it shapes the forms through which the world is experienced. Gombrich described an Egyptian image as a ‘cryptogram’, although we must understand Western perspective is also a cryptic structure of organising matter into an image. Perspective provides a pictorial system for encoding and organising matter into an exterior set of co-ordinates by which matter is disconnected to each other relative to a disembodied optic. The supra- or preter-natural, residing within human experience, has no accommodation within the projective geometry of perspective. Visual experience is an entangled, profoundly complex, and deeply evolved network of education, memory, trauma, desire, culture, hope, fear, reward, and so on. It has derived from an evolutionary history deeply responsive to its environment. Projective optical media systems hardly account for visualities that are fundamentally multi-sensory and entangled in experience and memory but it encrypts the world according to the rationality of exterior measurement and co-ordinates.

5. Affect—Event—Haecceity

Photography’s encryption of experience therefore creates a zone in which it can be recalled and enmeshed into the fabric of the present. One of the best-known accounts of this process, one is described by Roland Barthes in Camera Lucida (1980), whereby the image signifies the death of that which has passed, or ‘that has been’. Barthes’s ghost—his mother’s image as a young girl—is an example of how the zone created by photography bleed the dimensions of time; a photograph from several decades previous has a very real affect upon the present through which it is experienced. Photography’s zone entombs its subject whilst preserving a quality of it. As we have argued, rather than haunting life, or being a ‘hollowed’ form of it, a ghost endures and is sustained in the present. In fact, living can be more traumatic: as much as we try and cling to the presence of a moment, we can never fully grasp it as it is always eludes as it passes. A moment is always in the act of passing, even as we try to hold it, experience it: I can only experience it as it passes, whereupon it becomes memory. The photographic zone contains that which endured to become part of time itself by virtue of being continually repeatable in the present and future. The image of Barthes’s mother as a child provided a zone by which, in the future, it could appeal to the mourning of her 65-year-old son, despite almost a century elapsing between the creation of, and finding, the photograph. Whilst the photograph has a different pictorial structure to Egyptian hieroglyphs, a ghostly quality is nevertheless experienced in the present, brought into affect through the viewer’s desire in the present.

Photography’s capacity for recurrence of the past in the present was explored by Marcel Proust in Remembrance of Things Past (1913–1927). ‘Marcel’, Proust’s narrator, anticipated Barthes’s writing in his understanding of the photograph’s interconnection of past and present. Marcel is scornful towards his grandmother’s apparent vanity in having her portrait taken, critical of ‘the ridiculous childishness of the coquetry with which she posed for him, with her wide-brimmed hat, in a flattering half-light, [and I] had allowed myself to mutter a few impatient, wounding words, which, I had perceived from a contraction of her features, had carried, had pierced her.’ (Proust [1923] 1932, p. 115) However, following his grandmother’s death, Marcel deeply regrets his words. He learns that she had deliberately concealed being severely unwell; Marcel’s maid, Françoise, reveals that his grandmother had struggled to pose her ailing body into the desired gestures for the portrait. Marcel’s grandmother knew of her impending death, saying that ‘If anything were to happen to me, he ought to have a picture of me to keep.’ (Proust [1923] 1932, p. 127) Marcel’s grandmother wanted the portrait to be not for herself, but for Marcel after her death. Her gift was a zone whereby she could fashion her present moment as the past in Marcel’s future—an anterior future where it would be experienced after death.

Marcel’s profoundly transformed understanding of the photograph highlights a dimension of significance that the present brings to bear upon the past. The ghosts residing within the photographic zone are appropriately fluxive: meaning is not fixed as knowledge of the past can transform the present and future the present and future can recontextualise the past, which itself transforms and is transformative to that moment. To again refer to Derrida (1982), we might describe this zone as being subject to the law of différance—his neologism that describes how meaning is contingent upon context and can never be completely fixed since it is always in a state of being defined (subject to being different and meaning is therefore deferred). At its simplest, a photograph’s meaning can change depending on how it is perceived and understood. The crypt can never be fully sealed. Any ‘magic’ seemingly inherent within it lies outside of itself; magic lies not with the performer, who may create conditions for its emergence, but is instead conjured by its audience or, more specifically, an audience’s desire for magic to exist.

When Barthes exclaimed ‘There she is!’ at the photograph of his mother as a child, this, of course, meant that his grief necessitated her conjuring, her appearance. He desired an ‘affect’ from the possibilities offered by the photograph. When Proust’s Marcel returns to the photograph of his grandmother, he stares and utters ‘“It’s grandmother, I am her grandson” as a man who has lost his memory remembers his name, as a sick man changes his personality’. (Proust [1923] 1932, p. 127) Something appears, or rather, is made to appear, through the present’s appeal to that which appears to be past. To consider how ‘magic’ might be experienced in a photograph as an ‘affect’, we will finally turn to the concept of ‘haecceity’ within the work of Deleuze and Guattari ([1980] 2002).

The zone contains the latent possibility, a potential appeal to someone or something after the moment of its passing. Photographers have some degree of control and agency over the type and quality of the image’s appeal, but it must be encountered by someone to whom an appeal can be made. The overriding majority of photographs may offer a subject at a level of interest (or disinterest). The quantity of images that digital infrastructures support nurtures an inattention within its viewer, forming behaviours of viewing practice whereby we skip or scroll. Viewing and navigating images on a screen—often the handheld screen of a phone—creates encounters that are already passing. There appears little that is ‘magical’ in such encounters of images in transit, already exiting the screen and often at a size roughly equivalent to a medium-format film negative. And yet the proliferations of images are a consequence of a techno-industrial accessibility and commercial-democratisation of digital image publishing whereby a viewer’s attention, rather than the photograph, becomes the object of consumption. This is not to romanticise printed media, but to reflect upon the difference in the presentation of the image. Would Barthes have become so ‘pierced’ by the ‘punctum’ of an infant’s collar in Lewis Hine’s photograph if he encountered it whilst scrolling through social media? Would he even have noticed the ‘studium’ (descriptive detail) of the collar, let alone allowing for the small, specific detail to affect him as ‘punctum’? Barthes acknowledges that the appeal of an image, or a significant element of it, is dependent upon a quality of contemplation in comparison to the experience of cinema, whereby ‘I don’t have time: in front of the screen, I am not free to shut my eyes […] I am constrained to a continuous voracity; a host of other qualities, but not pensiveness.’ (Barthes [1980] 2000, p. 55) Indeed, the consumption of scrolling digital images is almost cinematic. Instead, the objects within a photographic print can have a different appeal, an appeal for a different, attentive, ‘pensive’ practice of observation—the appeal of which can even transform into something resembling ‘demand’ upon a viewer when received in particular contextual frames, such as its location (e.g., an institutional context) and history (position within a photographic historical canon).

The nature of Barthes’s search, however, was such that a digital image of his mother could have similarly contained the possibility of a very embodied, visceral response in the viewer—the response of an affect. Context may set the (theatrical) stage for the condition of spectatorship, but an audience must desire magic to be produced. Barthes deliberately describes photography’s possibility for affect in bodily terms: prick, wound, pierce, bruise, puncture, sting, cut. We have considered how his search for affect is symptomatic of mourning, and whilst Barthes describes how he is affected by an element ‘which rises from the scene, shoots out of it like an arrow, and pierces me’ (Barthes [1980] 2000, p. 26), of course, the photograph cannot wound: he desires to be wounded, to be pierced, in seeking to be affected. The forms within photography’s zone contain the potential of affect in the present moment. When an intensity of affectation is created, it is useful to consider Deleuze and Guattari’s term ‘haecceity’ as a way of considering it is as an event. If photography provides a zone into which desire can be projected, it accommodates the possibility of forming a haecceity whereby ‘magic’ is created – defined as a combination of elements to produce something other to, and beyond, the individual elements constituting that moment.

Deleuze and Guattari describe a haecceity as an assemblage of various elements that become something recognisable as a unique, individual entity. Originally, haecceity was a medieval philosophic term used by John Duns Scotus to propose a unique property, something akin to an ‘essence’, belonging to each particular ‘thing’ such as an object or person. Each thing has its own individual ‘thisness’ that differentiates it from others, thereby constituting it as unique. Deleuze and Guattari reformed the concept of haecceity to expand the traditional sense of what might constitute a ‘thing’. They instead proposed that forces, or energies, can assemble to coalesce into a coherent organisation of matter. Rather than the conceptual fragmentation of the world into objects in space—such as the organisation produced through linear perspective—they considered everything in terms of flows of energy, assemblages of relationships and states of matter. For Deleuze and Guattari, a haecceity might unfold from particular organisations and relationships of matter that constitute an emergence of a recognisable form, an expanded sense of a ‘body’. Examples include the unique properties of each season in forming their character; a haiku describing a coherent synthesis of matter and forces into an individual event with its own duration; descriptions in Charlotte Brontë’s writing that intercalate human and meteorological elements, whereby the synthesis of weather—people—faces—emotions form a distinct entity itself; a ‘Baked Alaska’ is a combination of degrees of heat that becomes a specific and a unique coherent assemblage; a werewolf emerges from ancient lunar cycles and the time of a particular moment in human experience. Deleuze and Guattari describe ‘things’, haecceities, according to different orders, of time and matter that form the basis for new organisations of matter to emerge.

To some extent, perhaps, Henri Cartier-Bresson’s notion of ‘the decisive moment’ elevated a photographer’s status in identifying haecceities, somehow reflecting the photographer’s ‘genius’ (or capacity to create ‘magic’): the photographer selected the moment whereby the assemblage of elements creates a ‘narrative’ signifying something greater than the sum of its components. The photographer/artist has a supposed privileged sensitivity to, or complicity in creating, moments whereby conditions converge into an event. Jeff Wall’s 1993 photograph ‘A Sudden Gust of Wind (After Hokusai)’ assembled a particular, individuated moment (‘event’) within a photographic frame, whereby different forces belonging to different non-linear qualities of time, from the existence of wind as a phenomena of air movement created by solar heating, the Earth’s rotation, and behaviour of gases, to the history of human language expressed through flying sheets of paper, and to the modernity of the telegraph poles receding into an industrial landscape. We might consider this to be a pictorial attempt to image a coherent entity, a haecceity. Furthermore, in a popular news story, Wall describes ‘Life scale [as] a kind of magic’ (PBS NewsHour 2021). His large-scale image, a photographic transparency displayed in a light box measuring 250 cm × 397 cm, echoes the experience of the Cubiculum Obscurum in creating an expanded form of perception, gesturing towards a theatrical presentation of the image.

However, in the examples of Proust and Barthes that we have mentioned, the affect created, in part, actually owes something to the lack of photographic ‘genius’ behind the camera. The image of Marcel’s grandmother later embodies a haecceity as Marcel’s transformed knowledge of the moment brings to bear a new experience of the image as an intersection of a diminishing life wishing to be remembered as fuller life, whereby the specific atmospheric (lighting) and bodily conditions (pose, attire) facilitate an individuated moment to function as a memorialised object: ‘he ought to have a picture of me to keep’. Marcel’s understanding of this moment entirely changes from perceiving his grandmother’s vanity to recognising her determination, bravery and love. An affect is created in Marcel through his grandmother’s frailty and proximity to death, therefore heightening the significance of her gift. As Barthes later described, in a photograph by Alexander Gardner of Lewis Payne (Powell) prior to being executed: ‘the punctum is: he is going to die.’ Affect is dependent upon the viewer’s knowledge and desire to be affected. Barthes’s photograph of his mother as a young girl may have remained an otherwise unremarkable image until a particular assemblage of contextual factors synergise into a haecceity as the affect of that moment created a unique, individuated event, marked by Barthes through his words ‘there she is!’ In these examples, the appeal and affectation of each image—in different ways—is created despite an innocence and ‘lack’ of a theatrical stage for magic. Photography’s ‘magic’ is possible in the most highly produced image to an utterly ‘naïve’ photograph since its affects are borne in the desires of its viewer. The condition of haecceity can be unpredictable—a ’spooky property’ whereby one may feel the rational ‘irrational’ compulsion to assign a quality of ‘essence’ or ‘spirit’ to an event or experience.

6. Magic, Consumerism, Desire

Throughout this essay, ‘magic’ has been presenced, in different ways, by having some relation to the event of an ‘affect’ that lies beyond conventional, rational, observation of images. When that affect becomes something resembling a significant event, it has the potential to resemble qualities that Deleuze and Guattari ascribe to the term ‘haecceity’. This is one possibility of the appearance of ‘magic’ relative to photography. However, like the business of magic-as-entertainment, we might also reflect that the experience of photographic affect has also become a commercially-intensified spectacular experience. As Lyotard warned, “The massive introduction of industrial and post-industrial technosciences, of which photography is only one aspect, obviously implies the meticulous programming, through optical, chemical and photo-electronic means, of the fabrication of beautiful images” (Lyotard [1988] 1991, p. 122). Imaging industries create the conditions for what Julian Stallabrass (1996) identifies as the mass consumer practice of photographing billions of sunsets. These perhaps have consumed the magic of experiencing a sunset—but clearly not the desire to capture it. As Susan Sontag wrote, ‘Photographs create the beautiful and—over generations of picture-taking—use it up. Certain glories of nature, for example, have been all but abandoned to the indefatigable attentions of amateur camera buffs. The image-surfeited are likely to find sunsets corny; they now look, alas, too much like photographs.’ (Sontag 1979, p. 85) The uniqueness of a ‘magical’ moment through the creation of affect is eroded by its ubiquity in becoming yet another image in the shared production and consumption of countless others. However, Penelope Umbrico’s 2006 Suns from Sunsets from Flickr offers space to propose a less critical, and more positive, attitude towards a global possibility of shared experience facilitated by technological democratisation. Additionally, in an age whereby every image has the potential to become ‘beautiful’, made possible through consumer technology, it has been interesting to observe the rising interest in ‘found’ and ‘amateur’ vernacular photography as offering something resembling a unique and authentic photographic experience, distinct from the daily production of mass spectacular imagery. In the age of the spectacular, the ‘banal’ offers an appeal of authenticity in contrast to the intensified marketisation of beauty, affect and attention.

Just as social media—one dominant way through which images are received today—monetises attention, we might reconsider the possibility that instead of the conventional, assumed sense that photographers create photographs, perhaps, rather, the imaging industries produce photographers. Recalling Richard Serra’s short film Television Delivers People (1973), we might propose that photography produces photographers. Lyotard argued that human knowledge became supplanted by the logic of a capitalist and industrial techno-science complex whereby, whilst a photographer chooses the subject, the image is actually produced by other forces (Lyotard [1988] 1991, p. 122). Clicking the shutter becomes an illusion of individual agency in the production of a photograph, given that very process of image-production is the consequence of intensive industrial research and development. The photographic industry has invested in the possibility of democratisation/mass consumerism of image production to the extent that Stallabrass suggests ‘Any fool could do it’ (Stallabrass 1996, p. 20). Indeed, since Lyotard’s writing in 1988, we have witnessed further mass intensification of the photographer as the product of imaging industries as both mass-consumer for, and mass-consumed in, a digital age of smartphones and social media. Lyotard had identified that ‘amateur’ photography ‘is not much more than the consumption of the capacity for images contained in the camera’ but also ‘the consumption of a state of objects and of knowledge’ (Lyotard [1988] 1991, p. 123). Whilst a conventional explanation of a photographer might be someone who uses photography to express thought about a subject, Lyotard’s argument is that imaging industries have enabled image production to the degree that the photographs virtually produce themselves. The automation of both hardware and software are responsible for image production and publication to the degree of compelling and producing photographers: photographs produce photographers. However, indeed, we are now witnessing the moment of automated photographic processes, such as facial recognition, whereby artificial intelligence selects its own images. A.I. and deepfake technology are also synthesising images that are experienced as photographs. Perhaps this is the logical end point for one of photography’s territories: some ‘photographic’ images no longer need photographers, just consumers.

Yet it might not be unreasonable to suggest that the industrial scale of research and development required to equip large proportions of populations to create ‘beautiful’ images—and share them globally—is, in one sense, quite magical in itself if ‘magic’ is defined by the elevation of human powers beyond its own capacities. Freud ([1929] 1961) described technology’s elevation of humanity to a level of ‘prosthetic Gods’, despite the difficulties of wielding such power. And yet when software filters can produce aesthetics once associated with magic, ‘magic’ itself may take other forms. The qualities of haecceity and affect are not static, nor can they be completely industrially produced given the degree of specificity involved in their appearance. One quality associated with magic is that its appearance is unexpected. A photograph, wherever it appears, still has the potential for a magic generated from an intersection with a viewer’s need and desire for affectation. The image still constitutes a zone that can connect with the anxiety, fear, grief, happiness that are potentially latent within the irrationality of the viewer.

Images therefore contain the possibility for irrational forces: ghosts haunt media, in part, because the ‘rationalist’ structure of representation elides the irrational dimensions of human perception and experience. As we have seen, technology’s fragmentation of the experience of time into a linear representational structure—although lived reality is far more entangled, as Egyptian hieroglyphs once suggested—suppress dimensions of human psychic life. The ‘zone’ of photography contains a past, but is not itself past. Ghosts dwell within the structure of the media, and its entombed subjects, their apparition and animation in the present are made possible by desire. The organisation of media may erase particular qualities of experience, but it also provides other possibilities, such as zones to be entwined with, and suffused into, the fabric of the present. However, the ’ghost’ of the photographic machine is conjured by the living. Magic does not happen to people, people happen to magic; we desire its appearance.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

Data sharing is not applicable to this article.

Acknowledgments

This article is inspired by, and dedicated to, the British academic and theorist Mark Cousins (1947–2020).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Barasch, Alixandra, Gal Zauberman, and Kristin Diehl. 2018. How the Intention to Share Can Undermine Enjoyment: Photo-Taking Goals and Evaluation of Experiences. Journal of Consumer Research 44: 1220–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barthes, Roland. 2000. Camera Lucida: Reflections on Photography. London: Vintage. First published 1980. [Google Scholar]

- Cotton, Charlotte. 2015. Photography is Magic. New York: Aperture. [Google Scholar]

- Crary, Jonathan. 1990. Techniques of the Observer: On Vision and Modernity in the Nineteenth Century. Cambridge and London: MIT Press. [Google Scholar]

- Damisch, Hubert. 1994. The Origin of Perspective. Translated by John Goodman. Cambridge and London: MIT Press. First published 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Deleuze, Gilles, and Felix Guattari. 2002. A Thousand Plateaus: Capitalism and Schizophrenia. Translated by Brian Massumi. London: Continuum. First published 1980. [Google Scholar]

- Derrida, Jacques. 1982. Différance. In Margins of Philosophy. Chicago and London: University of Chicago Press. [Google Scholar]

- Derrida, Jacques. 1991. Signature Event Context. In A Derrida Reader: Between the Blinds. Edited by Peggy Kamuf. Translated by Alan Bass. New York: Columbia University Press. First published 1972. [Google Scholar]

- Derrida, Jacques. 1998. Of Grammatology. Translated by Gayatri Chakravorty Spivak. London: John Hopkins University Press. First published 1967. [Google Scholar]

- Diehl, Kristin, Gal Zauberman, and Alixandra Barasch. 2016. How taking photos increases enjoyment of experiences. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 111: 119–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Foucault, Michel. 2007. The Order of Things. London and New York: Routledge. First published 1966. [Google Scholar]

- Freud, Sigmund. 1961. Civilization and its Discontents. New York: Norton. First published 1929. [Google Scholar]

- Garry, Maryanne, and Matthew P. Gerrie. 2005. When Photographs Create False Memories. Current Directions in Psychological Science 14: 321–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gombrich, Ernst Hans. 1968. Art and Illusion: A Study in the Psychology of Pictorial Representation. London: Phaidon Press. First published 1960. [Google Scholar]

- Gunning, Tom. 2008. Invisible Worlds, Visible Media. In Brought to Light: Photography and the Invisible, 1840–1900. Edited by Corey Keller. New Haven and London: Yale University Press, pp. 52–65. [Google Scholar]

- Husserl, Edmund. 1989. Origin of Geometry. Translated by John P. Leavey, Jr.. Lincoln and London: University of Nebraksa Press. First published 1936. [Google Scholar]

- Kant, Immanuel. 1968. Preface to the Metaphysical Foundations of Natural Science. In Philosophy of Science: The Historical Background. Edited by Joseph J. Kockelmans. Translated by Ernest Belfort-Bax. New York: The Free Press. London: Collier-Macmillan. First published 1786. [Google Scholar]

- Kemp, Martin. 1990. The Science of Art: Optical Themes in Western Art from Brunelleschi to Seurat. New Haven and London: Yale University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Lyotard, Jean-François. 1991. The Inhuman: Reflections on Time. Translated by Geoff Bennington, and Rachel Bowlby. Cambridge: Polity Press. First published 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Panofsky, Erwin. 1991. Perspective as Symbolic Form. New York: Zone Books. First published 1927. [Google Scholar]

- PBS NewsHour. 2021. How Photographer Jeff Wall’s Pictures Duplicate ‘Magic’ of Large-Scale Painting. Available online: www.youtube.com/watch?v=TqG8R6h_Q3E (accessed on 3 July 2022).

- Prinz, Jesse. 1993. Toward a Cognitive Theory of Pictorial Representation. Available online: www.uchicago.edu/philosophyProject/picture/picture.html (accessed on 15 December 2006).

- Proust, Marcel. 1932. Remembrance of Things Past, Volume II. Translated by C. K. Scott Moncrieff. New York: Random House. First published 1923. [Google Scholar]

- Slevin, Tom. 2022. X-Rays: Technological Revelation and its Cultural Receptions. In The Edinburgh Companion to Modernism and Technology. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Sontag, Susan. 1979. On Photography. London: Penguin. [Google Scholar]

- Sparrow, Betsy, Jenny Liu, and Daniel M. Wegner. 2011. Google effects on memory: Cognitive consequences of having information at our fingertips. Science 333: 776–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stallabrass, Julian. 1996. Sixty billion sunsets. In Gargantua: Manufactured Mass Culture. London: Verso, pp. 13–39. [Google Scholar]

- Tagg, J. 1988. The Burden of Representation: Essays on Photographies and Histories. London: Macmillan. [Google Scholar]

- Tamir, Diana I., Emma M. Templeton, Adrian F. Ward, and Jamil Zaki. 2018. Media usage diminishes memory for experiences. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology 76: 161–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wade, Kimberley A., Maryanne Garry, J. Don Read, and D. Stephen Lindsay. 2002. A picture is worth a thousand lies: Using false photographs to create false childhood memories. Psychonomic Bulletin & Review 9: 597–603. [Google Scholar]

- Wood, Christopher S. 1991. Intro. In Perspective as Symbolic Form. Translated by Christopher S. Wood. New York: Zone Books. First published 1927. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).