Abstract

The Lisa and John Slideshow is a theatrical response to my own earlier photographic project, Pictures from the Real World. Colour Photographs, 1987–88, interrogating recurring theoretical questions that challenge the discourse of social documentary photography through an expanded practice. As a significant piece of research, devised through participation with those depicted within the image, the forty-five-minute play questions representational methods through an alternate medium. The project evokes what else was knowable from the terrain of possibilities when the sovereign images of the former project were captured, as it reaches into photographs, opening contextual focus on the social, political and relational aspects of production. This paper is drawn from my Ph.D. thesis, What the Subject Does. Lisa and John and Pictures from the Real World submitted to the University of Sussex in December 2022. The question asked within this commentary is: How can unequal power relations within photographic representation of working-class communities be renegotiated through trans-media practice and the use of theatre?

1. Introduction

This paper, drawn from my Ph.D. thesis, What the Subject Does. Lisa and John and Pictures from the Real World, submitted to the University of Sussex in December 2022, discusses a singular performance-based resolution, The Lisa and John Slideshow (Moore 2017). The play was part of the parent project, Lisa and John that also included immersive and three-dimensional outcomes. See Figure 1.

Figure 1.

The set of The Lisa and John Slideshow at The Mac Theatre, Belfast 2018.

In the early 1980s and prior to studying photography at art school, I was employed as a “Visiting Officer” for the Department of Health and Social Security (DHSS).1 As an analogous arena to consider against the practice of documentary practice and within a period of economic recession, I was let over the threshold of family homes to “assess” living circumstances as a government employee.2 I worked within a state apparatus wherein “claimants” were subjected to visual and oral verification to ascertain their deservedness for “supplementary” payments, offering me formative experiences of the lives of others through the spectacle of domestic poverty. Whilst within that employment, my own social agency was activated through a developing political consciousness, as I acted in empathy with the other, within a system that was potentially in conflict with the same social group. Whilst the fuller experiences of the unemployed, the sick and the elderly remained unavailable to me, for staff such as myself, it was commonplace to advise claimants on the most innovative approaches to securing funds as political acts of facilitation.

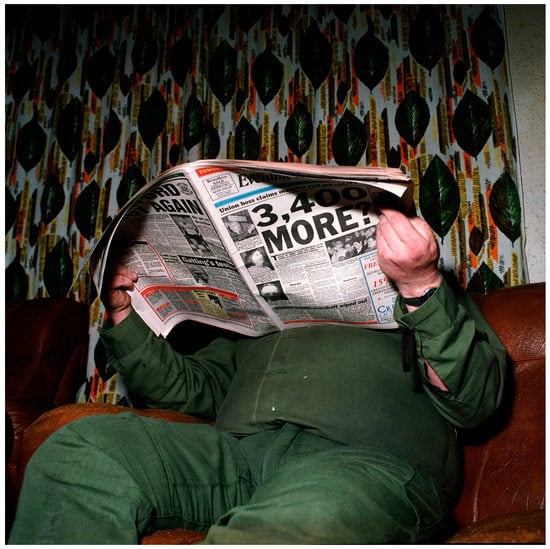

In 1985, I was accepted in the BA (Hons) Photography Course at West Surrey College of Art and Design, Farnham, England, where my experiences dovetailed within a reconsideration of my former role through photographic practice. As a series of photographs representing the lives of working-class families on the Osmaston Estate in the City of Derby, Pictures from the Real World, (Moore 2013) was made as my outgoing and final project. The first public view of the work appeared in Creative Camera, an independent photography magazine, within an editorial entitled State of the Art (Moore 1988), and later disseminated within a receptive art-photography discourse of exhibition and publication. Pictures from the Real World was published as a monograph in 2013 and continues to be widely exhibited, collected and published. See Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Untitled from the series Pictures from the Real World, David Moore 1987–1988.

The project Lisa and John (Moore 2017) had differing methodological starting points to that of Pictures from the Real World (Moore 2013). In 2015, after a chance meeting with Lisa and then John, both former subjects of the earlier project, I saw an opportunity to re-approach and reflect upon the photographs I had made twenty-five years previously, within an, as of yet, undefined platform. The couple, who were then married, but had now been divorced and with new families for over twenty years, agreed, separately, to be involved. This engendered a re-appraisal of my representation of the families, through the perspectives of those within the pictures I had made as a young photographer.

At the time of production of Pictures from the Real World, I considered that my own documentary practice contributed to a visual social history through complex and empathetic photographs of the families I worked with. Yet, I was simultaneously aware of unanswered questions around the methodologies of my production and dissemination and that the discourse the images were situated within was potentially compromised. My observations as a photographer inevitably mirrored my own interiority and were easily contextualised within discourses around social power, building on the works of Foucault and others to critique documentary practice pejoratively. Foucault’s notions of the inert body and the creation of the “fixed” subject through various processes of domination and control presented challenges within the academy that were echoed in critical theory to disassemble documentary work. Allan Sekula noted that, “for Foucault, panopticism provides the central metaphor for modern disciplinary power based on isolation, individuation, and supervision” (Foucault 1977, cited in Sekula 1986, p. 9). Within this context, we may find affirmation of signifiers of class leading to stereotyping, where the image is understood as a stable unit of fixed knowledge, within a discourse that assumes that such images, alone, may be purposeful as instruments of social change. Within these contexts, it became evident that my late actions with Lisa and John were conscious attempts to redress the previous body of work.

The premise of Allan Sekula’s view, according to which the “archive has to be read from below, from a position of solidarity with those displaced, deformed, silenced or made invisible by the machineries of profit”, became fundamental to my revisionist methodological approach (Sekula [1983] 2003). We embarked on a period of consultation. I invited the couple to review the sovereign body of work from which the book was developed, offering them a full view on everything produced, asking both Lisa and John to separately prioritise their own selections of photographs, an act that bound the entire project, becoming its eventual subject matter.

The couple’s re-evaluation of the former series eventually enabled a critical intervention, allowing for the initiating discourse that Pictures from the Real World was produced within, alongside the work itself, to be renegotiated through differing outcomes, one of which was my play The Lisa and John Slideshow, a forty-five- minute theatrical play, using actors performing a verbatim and devised script derived from the audio-recorded sessions of Lisa and John discussing their own selections from the body of work.3 See Figure 3.

Figure 3.

Performance documentation of The Lisa and John Slideshow. (Moore 2017).

The play’s establishing scene presents a momentary tableaux vivant as stage lights rise from total darkness and “Lisa and John” gradually appear within a minimalist setting of chairs, table and projection screen. Initially, both characters are still, as though within a photograph, returning the gaze of the audience from a static position that draws attention to their fixed location within the historic body of work. The “slideshow” is projected from behind the audience onto the projection screen on stage, whilst the name of its operator is acknowledged by “Lisa”.4

Throughout, the premise sees “Lisa and John” discussing their own selections of photographs with each other and the audience. As the photographs appear, called up by the couple, they catalyse memory and conflicting recollections of family life as well as relational circumstances between the family and the photographer, “David”, who is played by an actor within the audience. The Lisa and John Slideshow is cyclical; words performed at the outset are repeated at the end with differing direction and dramaturgical intent. As the last line is spoken, there is an instant cut to theatrical blackout.

2. Expanding Photography to Theatre

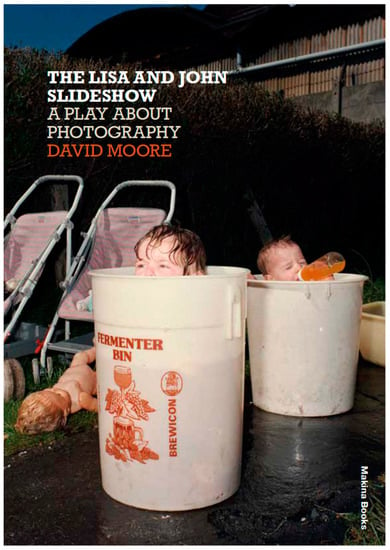

The play presents photography within theatre to explore how dialectically formed realism may manifest in performance. The play is located within an “expanded field” of photography, as described by Lucy Soutter who identifies works that explore “specific aspects of existing art forms” and are often mercurial as to their precise identity (Soutter 2018, p. 136). Soutter develops the precedents and discussion of this area, in particular George Baker’s treatise Photography’s Expanded Field that finds arguments against the “stasis” of photographic practice. (Baker 2008)5 Within my work, expanded practice can be understood as a necessary migration, using varying media and building upon theory and precedent, to speak beyond the limitations of documentary photography as a considered response to the presenting circumstances. See Figure 4.

Figure 4.

Cover of The Lisa and John Slideshow (script) David Moore (2019) Makina Books, London.

As an artist, I work intuitively and without specific outcomes in mind. I arrived at the possibility of performance through a response, in part, to circumstances, but also prior research. In 2016, during the early participatory discussions, Lisa and John both independently declined my request to present their selection of photographs from the original body of work in the public domain. This aligned with an earlier decision of my own not to re-photograph them at the outset of the project, subjecting them to a secondary and more permanent visual scrutiny. This process prompted a participatory turn in the project’s direction.

Other contexts that influenced this departure from the still image were reflexive and developed over several years. Through short courses, my own research into performance began through studying directing for stage, and then playing within small productions as an actor. From these experiences, I developed a critical interest in the performance of the subject, particularly where the use of tableaux became pertinent to a revision of content. This has been explored at various junctures in my own historical research and practice, forming a foundation supporting Lisa and John’s premise and including the facilitation of former subjects’ agency.

The Lisa and John Slideshow is significant for its use of photography as its central theme, and the play extends the works of various scholars who have investigated related performative tableaux, particularly where those within the frame were scrutinised within disciplinary contexts. Georges Didi-Huberman’s analysis of the performative display of pathologies within the Salpêtrière Hospital, France, in the 1880s described patients obliged, through coercion, to perform “evidence” of maladies, verified by photographic capture feeding back into the development of Charcot’s visually affirming his theories (Didi-Huberman and Hartz 2003). Didi-Huberman is interested in resistance within such performances, where patients failed, refused or were unable to comply. Similarly, Randall Rogers’ account of Congolese nationals, brought to the Louisiana Purchase Exhibition, USA, of 1908 for purposes of display, focused on proto-amateur photographers recording physical tableaux constructed to replicate the realities of Congolese lives (Rogers 2008, pp. 347–66). Rogers’ study reviewed performances to the camera by the Congolese; constructed displays of savagery within an index of hegemonical and racist anticipation of the other. Yet, the Congolese would consciously deny their performative obligations, instead presenting an “insubordination”, visibly ridiculing the premise using exaggerated mimicry of what was anticipated (Ibid). In both examples, the subjects responded with innate human agency to re-orientate their position within a prevailing discourse, which reveals spaces of resistance within revisionist readings of photographs where their “refusal” was significant.

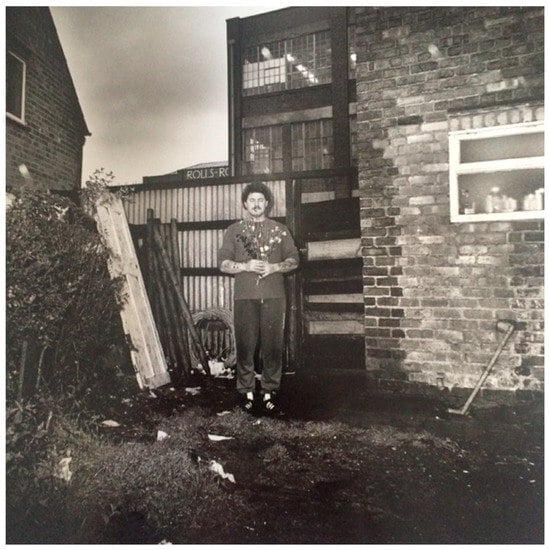

Conversely, within the histories of theatre, photography has often appeared as either metaphor or instrumental to plot. Joel Anderson has detailed numerous references to the medium within performance, citing Ibsen’s 1884 play, The Wild Duck, as an allegorical critique of photography as a commercially motivated portraitist seeks to operate within the modernity of C19th. And, more contemporarily within Robert Lepage’s The Seven Streams of the River Ota, (Lepage 1996), notions of photography are used within varying contexts, spanning years and connecting families in the wake of the Hiroshima bomb as various generations seek to retrieve fading memory from photographs that have been partially destroyed. (Anderson 2015). The Lisa and John Slideshow navigates related territory, yet stages documentary photography as the central protagonist. See Figure 5.

Figure 5.

John with Flowers from Collaborative Portraits. David Moore /John Mosley (1987–1988).

A precedent within my own visual practice is the unpublished series, Collaborative Portraits, made at the same period as the better-known colour photographs of Pictures from the Real World, which also offered opportunities to the families to formally contribute towards the construction of photographs describing their own lives (1987–88). Each tableau considered the mis-en-scene and employed trans-disciplinary methods that were part-performance and part-document. This presented a dialogue between differing methods of engagement, implicitly acknowledging colour documentary photography as one of many possible alternate representational methods to convey the families’ lives and setting a clear precedent for how Lisa and John would develop.

As culmination, theatrical performance presented as a viable apparatus allowing me to expand such research. Using actors to deliver the verbatim script would replace the requirement of the couple’s presence and maintain a focus on the vernacular in production, forming a socially orientated theatrical methodology and exacerbating the indeterminacy of the already complex layers of representation.

During the project’s progression, I was able to build upon precedents wherein performance had been used as a facilitatory tool. In 2007, I had been introduced to the contemporary works of Quarantine Theatre through their production, Susan and Darren, a two-handed performance that presented the “real” Susan and Darren, a mother and her adult son, discussing their lives and inviting audience participation in several ways, submitting themselves to a question-and-answer session at the end of the show.6 Quarantine’s facilitation of non-performers drew, in turn, on the emancipatory practice of Forum Theatre developed by theatre-maker and activist Augusto Boal. Boal’s model emphasised the significance of marginal characters within performances, moving away from classical plays to enable working-class audience members to build a more direct familiarity with the characters on stage (Boal 2008, p. 139). Realising that his actors were taking fewer political risks than local audiences were in their real lives, Boal encouraged participation to address local issues, enabling non-performers to contribute.

The Lisa and John Slideshow differs from these two examples through the participatory methods used to critically regard photography through the performance of the former subject’s agency and the associated playing out of the onstage dialectic. Within performance and led by the verbatim script, a reorientation of meaning and ownership becomes evident and new understandings are incurred for the spectator alongside responsibilities to re-orientate one’s own perception of the image. On stage, this extends the photographs potential for the audience, referring to Azoulay’s hypothesis, that through secondary and extended viewings of the image, the spectator may “watch” the photograph (Azoulay 2008, p. 14), that is, a reconsideration of the traces within it. Notably, Azoulay’s focus on such engagements and what may come of them has precedent within Augusto Boal’s Forum Theatre, where, in collaboration with the spectator, scenes are performed a second time in the same sitting and “the participant has to intervene decisively in the dramatic action and change it” (Boal 2008, p. 117). Whilst Azoulay writes that “The spectator’s work also is one of prolonged observation, performed on the margins of a particular activity or event”, within The Lisa and John Slideshow, it is also the former subjects’ response, as spectators of their own lives who direct a revision of the image (Ibid).

In this sense, The Lisa and John Slideshow eases the viewer away from an understanding of the photographic image as incontrovertible through a re-imagining that extends beyond the photograph as a “finalised determination of knowledge” (Azoulay 2008, p. 152). The Lisa and John Slideshow maintains an ambition for equity through participation. An outcome of the play is a theatrical representation of the “players”, which tells more than the photographs. To achieve this, the participatory process becomes visible in performance, reframed as theatrical action as the audience and characters verify the projected images together as they appear, live, on stage. Through performance, onstage discourse excavates latent possibilities of meaning from the images for the former subjects whilst opening a systemic and localised critique of documentary photography’s claims, re-contextualising the paradigmatic languages at play in Pictures from the Real World.

3. Theatrical Challenges to Panopticism and the “Fourth Wall”

The Lisa and John Slideshow applied Brechtian methods to disturb the certainties of representation in performance. Gestus, a Brechtian neologism, describes an action that “need not restrict itself to a series of socially significant gestures” (Barnett 2000, p. 96). As a significant but indeterminate currency with the play, gestus as a critical mechanism problematises the fixed image and positions performance as a significant response to the ways in which we perceive photographic meaning.

Whilst sitting with Lisa, and then John, recording their responses to images in the earlier stages of the project, I noticed that each occasionally implied, rather than directly stated, a criticism of the other, responding in ways that were beyond language through physical gestures or silence. My direction of The Lisa and John Slideshow engaged with the potential of such mercurial signs. As a theatrical response, the play harnessed such fluidity, understanding it as outside of the bounds of panoptic perspectives, functioning as a theoretical challenge and evasion of fixity through live acting. In performance, what is inexpressible in words becomes a flow of theatrical actions; signifiers that potentially re-orientate narrative through the natural development of physical acting. Whilst such indeterminacy may be observed optically, as within the illustrative photograph below, in live performance it passes fleetingly. See Figure 6.

Figure 6.

Rehearsal documentation of The Lisa and John Slideshow, Derby Theatre. (Moore 2017) ©Callum Beany.

Gestus also presents within the play’s oratory context. Here, “Lisa” responds non-verbally to “John’s” claim of parental efficacy:

John: … And all of the kids know where I am at the end of the day…but ‘cos I am working all the time I don’t go around and impose… they come and see me, when they like…Lisa: …(Moore 2019, p. 55)

Observed (or not) in performance, this section introduces a momentary silent gesture as speech-act that is beyond orality and written into the verbatim script. Such observations can also be located within legacies of anthropological discourse, building upon Elizabeth Edwards’ research to consider the significance of haptic engagement with material photographs by those looking at them, where “silence, the absence of voice or sound, can be equally significant” (Edwards 2005, pp. 37–38). Within the performance of The Lisa and John Slideshow, gestus represents the characters’ interiority, as unconsciously acknowledged yet mnemonically irretrievable actions.

Within the play, I produced intentional narrative anomalies or ‘alienation affect’ to work against what Brecht described as the ‘steadiness’ of narrative; the anticipation of the expected. Such anomalies offer ‘spurts’ in performance, augmenting a larger momentum to challenge perspective in ways that problematised the performance of Lisa and John’s responses. As in Brechtian theatre, gestures appear that are designed to dissolve the “fourth wall” as actors provoke eye contact and verbal communication with audience, seeking reciprocity as their characters discuss the photographs.

Other strategies encourage active viewing as a consideration of the work’s purpose. A further pertinent example finds “Lisa” articulating the uncertainty of her role on stage as she refers to (the actual) Lisa’s refusal to appear, conflating the fictional and the real as theatrical playfulness and a statement of facts asserting the literal circumstances.

Lisa: David asked me if I would do this presentation here tonight myself; there was no way… I think actors were probably better really. (sic)(Moore 2017, p. 11)

In a similar extension of theatrical reflexivity, the character, “David”, as a photographer located in the auditorium, answers a challenge from “Lisa” in an unanticipated gesture that further transforms the live experience for the audience, developing a dialectic between what is performed on and off stage, as he speaks back to answer her question.

Lisa: I like this one, it shows exactly where we were in relation to what it is now... I thought it might be a good project for David to go back and take some pictures in the same house ... but I can’t remember what you said...?David: Oh! I went and knocked but it didn’t go any further Lisa.(Ibid, p. 25)

These gestures draw attention to the artifice of The Lisa and John Slideshow, employing ‘alienation theory’ or ‘distancing affect’, as a mechanism to ‘re-see’ content.7 As well as reiterating the participatory elements of Lisa and John, the complexity of such dialogue articulates a refusal to fixed notions of representation. As with Brecht’s The Messingkauf Dialogues (Brecht 2002), where an unfinished theoretical discussion is both of itself, and a rumination of the play being performed, such dissociation in The Lisa and John Slideshow functions as an intervention that challenges the performativity of knowledge production and its representational premise from within the work. Such anomalies are furthered in the script, occasionally drawing on the verbatim of both Lisa and John, producing reveries within performance where representation takes shape from memory and the imaginary, and social actuality is interpolated by the unconscious, as an uncertain sense of recall.

These sections playfully extemporise the real in unexpected ways, whilst retaining indexical traces from the source. Here, a reminiscence by “John”, located between the real and the imagined becomes an image in its own description.

John: I like all them old pictures, back in the day, shops...the 50’s and 60’s, butchers—with all the meat hanging outside... all lined up for Christmas …Christmas fayre, at the butchers……You couldn’t do that now, health and safety, you know... something true to life... and nobody died, nobody died…(Moore 2019, p. 62)

Speaking of the world that Lisa and John’s parents grew up within, this repeated and final section of the play reveals a wider sense of family history through fragmented referencing of “old pictures” as nostalgic simulacra. The images described were held in memory and conflated into a performance that carries the “the real” as metonym, further alerting the audience to ways in which truth is anticipated from a performance of realism.

4. Performing the Real

Participatory methodologies were inherent throughout production. As part of the process, script approval was sought from the couple and granted within a process wherein actors met their “character” and small living room performances were conducted in Lisa’s home. We, myself as director/writer, the actors and the producer, were custodians of the couple’s agency and negotiations between all participants became exchanges of social and representational power. Within the project, such power was dispersed, re-negotiated and reproduced in the new works. From a personal perspective, Lisa and John was actualised after the first performance of The Lisa and John Slideshow at Derby Theatre in March 2017. Although the couple could not attend due to illness, two of their children, Clare and Nickola, both of whom featured within Pictures from the Real World, were present. By prior arrangement, Nickola joined the actors, producer, Professor Val Williams and I, for a public discussion after the performance, sharing the platform and contributing to the discussion. Her presence on-stage as former subject extended the dialogical premise of Lisa and John. See Figure 7.

Figure 7.

Post premiere panel of The Lisa and John Slideshow at Derby Theatre 2017.

Whilst this opportunity for Nickola to discuss the representation of her family’s life symbolically resolved the project, I was conscious that differing outcomes, potentially furthering a more systemic democratisation through action, had been missed. The first performances of The Lisa and John Slideshow were publicised as free events within the context of an international photography festival and, as such, found mainly a photography-art audience. My hope for a performance at the heart of the Osmaston Estate did not materialise as the momentum of funding and production opportunities presented other directions that proved both distracting and financially necessary to follow. A variation of Boal’s Forum Theatre, facilitated within the locale that embodied the content of the work, through a devising of site-specific citizen-led dialogue, presents an example of alternate community focus which may have further tested the social usefulness of The Lisa and John Slideshow with non-artists.

Regardless of location, however, through a referencing of fictional and non-fictional narratives, allowing for the use of performance to report the content of the photograph in an alternate form, the play offered perspectives on how the theatrical depiction of social agency re-affirmed representation as a contestable space. Drawing from the facilitated interventions of former subjects, The Lisa and John Slideshow developed a template through critical practice, devising responses and producing dialectical outcomes denied by the originating discourse to interrogate the original body of work. The play asserts an authority over the sovereign photographs through theatrical discussion of family memory, expanding documentary practice to publicly recontextualise the images whilst retaining social purpose. Whilst the play risks a further objectification of a working-class family, because that is what the couple were, now their own words re-orientate the photographs as an ongoing metamorphosis, offering narrative against stasis and indeterminacy against certainty. The published script of the play has enabled Lisa and John to assert an alternate representation of their younger selves within the public domain (Moore 2019). As a renegotiation, The Lisa and John Slideshow re-presents unresolved questions around representation within a template for a more democratic document.

Funding

This research was funded by CREAM at the University of Westminster, London.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all participants involved in this project.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

Notes

| 1 | The Department of Health and Social Security (DHSS) was a government department that managed “benefit” payments to the unemployed, the sick, the disabled, the elderly and other individuals in need. Due to the severe recession, unemployment rose to 3 million and the high unemployment persisted throughout the 1980s. Unemployment was particularly concentrated in the former manufacturing heartlands of the north, Wales and Scotland’ UK Economy in the 1980s. Available at https://www.economicshelp.org/blog/630/economics/economy-in-1980s (accessed on 21 March 2021). |

| 2 | I use the phrase “sovereign” throughout this paper in reference to the original body of work that Pictures from the World was drawn from, that is, my own practice that subsequentially formed the edited body book and exhibition of the same name. |

| 3 | The Lisa and John Slideshow was first performed at Derby Theatre on 25 March 2017 as part of the Format International Photography Festival. During 2017–18, the play was performed to varying audiences in professional theatres in the United Kingdom, including The Mac Theatre, Belfast, and The Regent Street Cinema, London. Additionally, a live rehearsal as a free public event was enacted as part of a series of research events at the London College of Communication, London, England. Available at https://ualresearchonline.arts.ac.uk/id/eprint/10873 (accessed on 22 August 2021). |

| 4 | Whilst the use of the noun “slideshow” has connotations of domesticity, it is also drawn from the author’s role as an educator. |

| 5 | Baker, in turn, extends Rosalind Krauss’s critique of post-modern sculpture, Sculpture in the Expanded Field (1979). |

| 6 | Quarantine Theatre, established in the UK by Richard Gregory, Renny O’ Shea and Simon Banham in 1998. Available at https://qtine.com (accessed on 14 February 2022). |

| 7 | I employ the term “distancing effect” to recognise an appropriation within Lisa and John that aligns with a larger intention to occasionally “make strange” through an apparently anomalous intervention, and in doing so alert the audience towards a critical consideration of what is before them. “Alienation effect”, another term for the same method, was developed and employed by Brecht, to encourage the audience to respond “consciously” (Willett 1964). |

References

- Anderson, Joel. 2015. Theatre and Photography. New York: Red Globe Press. [Google Scholar]

- Azoulay, Ariella. 2008. The Civil Contract. New York: Zone Books. [Google Scholar]

- Baker, George. 2008. Photography’s Expanded Field. In Still Moving: Between Cinema and Photography. Edited by Karen Beckman and Jean Ma. Duke: Duke University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Barnett, David. 2000. Brecht in Practice. London: Bloombury. [Google Scholar]

- Boal, Augusto. 2008. Theatre of the Oppressed. London: Pluto Press. [Google Scholar]

- Brecht, Bertolt. 2002. The Messingkauf Dialogues. Translated by John Willett. London: Methuen Drama. [Google Scholar]

- Didi-Huberman, Georges, and Alisa Trans Hartz. 2003. Invention of Hysteria: Charcot and the Photographic Iconography of the Salpêtrière. Cambridge: MIT Press. [Google Scholar]

- Edwards, Elizabeth. 2005. Photographs and the Sound of History. Visual Anthropology Review 21: 27–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lepage, Robert. 1996. The Seven Streams of the River Ota. By Robert Lepage and Ex Machina, Québec. New York: Brooklyn Academy of Music, Brooklyn, December 14. [Google Scholar]

- Moore, David. 1988. State of the Art. Creative Camera magazine, 1988–Issue 8/9. London, pp. 34–37. [Google Scholar]

- Moore, David. 2013. Pictures from the Real World. Colour Photographs 1987–88. Manchester and London: Dewi Lewis/Herepress. [Google Scholar]

- Moore, David. 2017. The Lisa and John Slideshow. (Theatrical Play). London: Makina Books. [Google Scholar]

- Moore, David. 2019. The Lisa and John Slideshow. (Script). London: Makina Books. [Google Scholar]

- Rogers, Randal. 2008. Colonial Imitation and Racial Insubordination. History of Photography 32: 347–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sekula, Allan. 1986. The Body and the Archive. Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press. [Google Scholar]

- Sekula, Allan. 2003. Reading an Archive: Photography Between Labour and Capitalism in The Photography Reader. Edited by L. Wells. New York: Routledge, pp. 443–52. First published 1983. [Google Scholar]

- Soutter, Lucy. 2018. Why Art Photography? Oxfordshire: Routledge, pp. 131–38. [Google Scholar]

- Willett, John, ed. 1964. Brecht on Theatre. New York: Hill and Wang. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).