Abstract

This article examines a recent form of marketing superhero comics that has garnered extensive media attention and has been promoted as the next big step in comics production: the decision by companies like Marvel Comics and DC Comics to offer selections of their intellectual properties as non-fungible tokens (NFTs). Focusing specifically on Marvel Comics’ collaboration with the VeVe app, which serves as a digital auction house through which customers can buy comics and related merchandise, this article suggests that we are witnessing the popularization of an already popular product (superhero comics) in a process that is indicative of larger transformations of the popular. As an agent of such transformations, superhero comics were introduced in the 1930s and 40s as a “low medium” with mass appeal that was critically devalued by proponents of high culture, but they are now widely celebrated as a “popular medium.” We argue that this transformation from a popular but devalued (“low”) product to a popular and culturally valued (but not necessarily “high” cultural) artifact marks a shift from qualitative to quantitative valuation that was driven at least in part by popular practices of collecting, archiving, and auctioning that have enabled the ongoing adaptation of these comics to new social, technological, and media demands. The article uses the newsworthiness of big auction sales and the sky-rocketing prices that well-preserved comic books can garner as a framework for assessing the appearance of superhero NFTs and for gauging the implications of this new media form for the cultural validation of comics.

1. Auction Records: Popularity and Validation

Popular is what is noticed by many (Hecken 2006, p. 85), and “[w]hen something is declared to be popular […] and […] that attention is measured, compared to other measurements, and popularized—it is irrevocably transformed and viewed differently” (Döring et al. 2021, p. 4; see also Werber et al. 2023).1 This is the minimal definition of “popular” that grounds our argument in this article. But how can we investigate the consequences of such popularity? How can we identify changes in the appraisal and evaluation of artifacts simply because they are noticed by many? We refer to these processes as transformations of the popular and investigate their premises and consequences by focusing on the convergence of two widely publicized phenomena: the massive increase in value of old superhero comics, which serves as the prerequisite for new forms of digital value creation, and non-fungible tokens (NFTs), which popularize superheroes in a highly volatile digital marketplace.

“How Are VeVe Comic Book NFTs Changing the Collecting World[?]”, one enthusiastic commentator named Dr. Howard recently asked on the website NFT News Today (Howard 2022). Dr. Howard promoted the VeVe app, through which customers can bid for and purchase NFTs released by Marvel and other comics publishers, and which we will analyze at length below, as a “digital solution” to the “physical problems” of comic book collecting. Despite the cheerleading tone and promotional rhetoric that often dominate NFT coverage, the durability of superhero NFTs (and NFTs, more generally) is still very much uncertain. It remains unclear at the time of this writing whether they will end up as a short-lived fad, pushed for a limited time by certain companies and promoted by certain kinds of media attention, or as a stable element of digital popular culture. This uncertainty, we suggest, does not invalidate our argument about the new valences of superhero comics. The history of the genre is filled with fads and commercial failures, all of which have contributed in one way or another (as paths ultimately not taken but occasionally revived at some later point) to the successful multi-decade evolution of the genre. In fact, as popular genres face new social, media, and technological environments, adaptation becomes a necessary means of survival, with some adaptations enabling evolutionary progress and others ending up as dead ends.2

Heeding our initial premise—popularity means getting noticed by many, and the display of measurable popularity makes a difference—we begin our foray into what we call the new valences of superhero comics with a sample of spectacular headlines from major US newspapers and magazines. “First ‘Fantastic Four’ Comic Sells For $1.5 Million,” reads the headline in the online edition of Forbes Magazine on 8 April 2022 (Porterfield 2022). On the same day, the New York Times reports: “First Issue of Captain America Comic Book Fetches $3.1 Million at Auction” (Patel 2022). A year earlier, on 7 April 2021, the LA Times ran the headline: “Look! Up in the sky! It’s a stratospheric $3.25-million record sale of rare Superman comic” (LA Times 2021). We could continue this list of headlines, but the phenomenon that primarily interests us in this article can already be articulated on the basis of these examples: In all three cases (Marvel’s Fantastic Four and Captain America, DC’s Superman), we encounter a well-preserved first edition of the first issue of a popular comic book series (a so-called “key” issue3), and the millions raised are presented as a stunningly high sum.

The spectacularism of these sales, which the Superman headline simulates by alluding to the opening credits of the television series Adventures of Superman (1952–1958)—“Look! Up in the sky! It’s a bird! It’s a plane! It’s Superman!”—remains largely implicit, however. It arises from the latent tension between a pop aesthetic rooted in the promise of entertainment, which advertises the historically denigrated but immensely popular medium of comic books primarily through spectacular titles such as Action Comics, Captain America, and Fantastic Four, and the exorbitant auction prices that these flimsy floppies may fetch and that readers would most likely rather attribute to the art market.4 What was often considered trivial and inferior by proponents of high culture around the middle of the 20th century and originally reached the hands of readers through inexpensive periodicals (Action Comics #1, Captain America Comics #1, and The Fantastic Four #1 each cost 10 cents) is now garnering astronomical prices.5 It is a long way from derogatory accounts of the medium, as evidenced, for instance, by the psychologist Fredric Wertham’s essay “Such Trivia as Comic Books” (Wertham [1953] 1998) or the critic and author John Mason Brown’s tirade against comics as “the lowest, most despicable, and most harmful form of trash” in the Saturday Review of Literature (Brown 1948), to their current status as potentially valuable artifacts.6 Historical cultural inferiority and current monetary value do not seem to converge in this case; what was deemed by such older critics as part of comic books’ dangerous allure—their massive popularity, which had the potential to seduce the innocent, as Wertham announced in the title of his eponymous book Seduction of the Innocent (Wertham 1954)—now constitutes a major part of their appeal. We no longer read comic books against the high cultural grain of established public opinion but with the knowledge that we are engaging with a medium that is legitimized, instead of denigrated, through its popularity.

How is it possible that a throwaway artifact that once cost 10 cents can now, under certain circumstances, garner $3.1 million? These prices are only achieved because what had started out as individual comic book issues turned into long-running series that continue to be popular and have spawned a highly differentiated and professionalized collectors’ market (Bachman 2022). This market, we should note, was built around and structured by a number of interacting institutions, from publishing companies, trade magazines, price guides, and auction houses to comic book stores, comics conventions, and various forms of fan engagement. Premised on the ongoing financial and personal investment of comic book sellers and buyers, including collectors with more or less commercial incentives, this market has helped sustain the superhero genre through its evolution across successive “ages” (Golden, Silver, Bronze, etc.) and through technological and media changes, from the digital affordances of comics production, distribution, and reception to its shifting place in the ever-expanding transmedia environment (television, cinema, videogames, etc.).

The fact that the first issues of certain superhero comic books can be traded as “rare” and thus treated as “valuable” commodities follows from their status as “classics” and “milestones” of a genre that is still commercially successful, still subject to serial sprawl (Kelleter 2017, p. 20), and still emblematic of US exceptionalism. Rare objects that receive little or no attention have no increased cultural or economic value. If the sales success of particularly well-preserved original issues of classic comic books is exhibited in newspaper or magazine articles as proof of their importance, then we are dealing with a price-coded form of what we might call second-order popularization, defined as follows: “Second-order popularization […] refers to practices in popularization that create popularity by determining and highlighting the fact that something already has received much attention,” e.g., through charts or rankings (Döring et al. 2021, p. 13; Werber et al. 2023, p. 12).

What may look like a rather simple, perhaps even tautological observation becomes a much more complex affair when we consider its fundamental implications: It makes a crucial difference if we are aware of the fact that the comics we read are not only read by many other people but that they are no longer denigrated as trashy entertainment but revered as a commercially and culturally potent popular artifact. This has implications for how we talk about these comics, how we read them, and how we treat them (e.g., as collectibles rather than as disposables), but also for our decisions about what to read, what to buy, and what to collect. The increasing prominence of second-order popularization in our current cultural moment indicates and fosters new regimes of validation, we suggest, according to which quantified forms of popularity (sales numbers, views, clicks, comments, etc.) are used not only to further market a product but also to validate, or legitimize, its cultural value. While these processes are facilitated by people and institutions, they also possess an “inherent tendency” (Kelleter 2017, p. 19) according to which popularity seems to be supplanting, or at least challenging, older forms of cultural validation.7 Based on our understanding of popularity as large-scale public attention that is quantified and displayed as evidence of an artifact’s cultural legitimacy, superhero comics have established themselves as a fixture of US and indeed global popular culture precisely because they have been able to generate continuing and massive interest (and sales, of course) for almost a century.

There is no doubt that the content of the auctioned comic books celebrated in newspapers and magazines as well as across the internet is popular since the stories remain in print many decades after their initial release (which means that there continues to be an audience for them) and since the superheroes they introduced now dominate film, television, and, to a lesser extent, videogames (Rauscher et al. 2021).8 It is not just that these stories are still available; in fact, the so-called classics of the genre have been and continue to be reprinted in various anthology formats despite the fact that they are readily available as digital copies on places like Marvel Unlimited. Stories that are no longer popular, however, will eventually cease publication. They may still be collected by some and archived by others, and perhaps sold on occasion, but the broader public will no longer encounter them. Only specialists in comic book history will know all of the early comics Jules Feiffer (1965, p. 23) lists in The Great Comic Book Heroes: “Whiz, Startling, Astonishing, Top Notch, Blue Ribbon, Zip, Silver Streak, Mystery Men, Wonder World, Mystic, Military, National, Police, Big Shot, Marvel-Mystery, Jackpot, Target, Pep, Champion, Master, Daredevil, Star-Spangled, All-American, All-Star, All-Flash, Sensation, Blue Bolt, Crash, Smash, and Hit Comics.”

Due to the large proceeds and the spectacular exclamations of the headlines, the increased economic and historical value of the comic books, initially conceived by their producers as disposable products that are now revered as collectable artifacts, is additionally highlighted as particularly noteworthy. This means getting noticed by many—not just by fans, who can, of course, be many but who represent only a portion of the general populace, but also by those who would not necessarily buy comic books yet encounter news about the spectacular value of these artifacts in major news outlets and countless online spaces. The argument, thus, is no longer whether superhero comics are worth reading or collecting at all or whether their “low” content is harmful to their followers but rather that comic book superheroes are widely noticed and central to an increasingly global popular culture.

The superhero comic books that emerged from rapid industrial production processes in the early years of the genre, when they were assembled by creator teams with work-for-hire contracts and sold at newsstands and in supermarkets, have become big players in a globally proliferating market of serial transmedia entertainment. The enduring popularity of this genre—this is the first part of the thesis we want to propose in this article—is the most important condition for the subsequent validation of early comic books, in both a monetary and a cultural sense. Since these issues were mass-produced and sold for a very low price, the newspaper articles cited above do not report on the only existing issue of a comic, nor on its designation as an original in the classical sense. There is indeed more than one copy of Action Comics #1. In fact, it is estimated that about 50–100 copies exist today, although a total of 200,000 copies were produced in 1938 and the comic has been reprinted countless times (Roe 2014).9 This stark discrepancy between the initial circulation and the remaining copies harks back to the fact that the issues were once considered ephemeral due to their poor paper quality and their status as an easily consumable item for a primarily youthful audience, which usually purchased them without archival or otherwise preservative ambitions (Stein 2021b, pp. 15–70). Accordingly, the auctioned issues are by no means unique, but they are quite rare given the fact that not all the issues that are still available enter the market at the same time and that not all of them are in good condition. These comic books are thus not originals in the strict sense but rather industrially produced mass items that have surprisingly outlived their sell-by date.10

As mass-produced narratives aimed at a mainstream readership, Golden Age comics from the 1930s to the 1950s were the work of self-identified craftsmen, who saw themselves as skilled professionals but not always as artists in any traditional sense and who were usually paid a fixed amount per page without any claim to copyrights or royalties.11 Moreover, the final product that readers hold in their hands resulted from a collaborative production process that historically included not only the efforts of editors, authors, and illustrators but also the processing of the artwork, which was initially drawn in black and white and provided with instructions for coloring, into the printed comic book page. Some of the early original drawings and artwork have survived, but because they are only accessible to very few readers and have therefore not received widespread public attention, they are much less prominent than the iconic issues that have become “classics” and have been read by generations of fans (Gabilliet 2016, pp. 16–25). The monetary value of the few remaining first editions of these “classics” thus results from a paradoxical situation: Only extremely well-preserved floppies that show (almost) no signs of usage can fetch very high prices, and only individual copies of very popular series that were virtually unread at the time of their publication and stored in a pristine or near-pristine condition afterwards will be close to their original quality.12 This is not to suggest that only these high sellers matter. Indeed, readers, collectors, and commentators are certainly aware of the fact that older comics in less-than-ideal condition can still sell for substantial sums. However, there is a significant difference between these mid-level sales and the spectacular top-sellers because it is the latter that catapult the comics into the public limelight. When Action Comics #1 sells for $3.2 million, it is international news, and the number of people who become aware of the sale will be substantially higher than those who will notice when a non-pristine copy of a lesser superhero and a less iconic issue sells for a much smaller sum.13

Superhero comics are a form of popular serial storytelling that has largely left behind its initial status as an inferior and ideologically suspect product of low culture and is now admired as a representative of a popular culture that has attained monetary as well as cultural value.14 Since the 1990s, they have been auctioned by some of the world’s most renowned auction houses, including Sotheby’s and Christie’s, as well as on web portals such as eBay.15 Their spectacular sales, we believe, mark a transformation in the cultural appreciation of popular artifacts that are increasingly noticed by prestigious publications such as the New York Times, LA Times, and Forbes (not to mention comics blogs and websites) as well as beyond the United States (Spiegel Panorama 2022). These new valences of old comic books raise a number of questions we will address in this article: How can the rise of these superhero comics from a mass-produced disposable product to a popularly acknowledged and broadly legitimized coveted collectible be described? How may we understand the (re)validation of originally cheap print products of bygone eras in the age of digitization, where readers are ultimately just a few clicks away from an inexpensive digital version of the auctioned issues, and where purchasing the original issue is no longer necessary to access the content?16 Which popularization dynamics—which transformations of the popular—drive the emergence of the new digital valences of superhero comics through NFTs and apps such as VeVe?

2. New Digital Valences: Non-Fungible Tokens

At the beginning of this article, we mentioned two phenomena that have been attracting significant attention in the field of superhero comics (and beyond) and that are both expressive, each in its own way, of what we have termed the new valences of superhero comics. The second phenomenon, in addition to the auctioning successes of old comics, includes recent attempts by industry leaders DC Comics (Warner Bros. Discover) and Marvel Comics (Disney) to promote and sell their intellectual properties in the digital marketplace. This leads us to the second part of our thesis. We propose that while these marketing efforts contribute to the ongoing validation of superhero comics, they also raise different questions than the high-stakes auctions of now-expensive print issues. While the public commentary about the print sector tends to foreground the discrepancy between the original cheapness and lowness of comics and their current status as valuable cultural artifacts, digital formats move different issues—including copyright and ownership—as well as different conflicts—between publishers and artists—into focus. In addition, if old comic books really have to be rare (and in excellent condition) to scale the heights of auction sales, companies like Marvel and DC artificially create scarcity in the digital realm by purposefully limiting their offerings, attracting potential buyers with different probabilities of success, and at the same time presenting themselves as cutting edge, in tune with the zeitgeist.

Consider the contrast between collecting physical comic books and NFTs, which is encapsulated in the following comparison provided by the online commentator Dr. Howard:

“Imagine owning a physical Fantastic Four #1 (1961) comic book (CGC 9.6 graded has fair market value over 6 million$), there comes the liability for you in proof of authenticity, dealing 6–12 month grading timeline with grading companies (CGC, CBCS etc), insurance and trivial tips for preserving. I bet you would be too afraid to take this amazing book out of your house in case ruining the potential million-dollar ‘paper’. It is even much more tricky when it comes to selling.

With comic book NFTs:

- Worldwide marketplace open 24/7, transactions are completed within milliseconds.

- They don’t degrade, saving you efforts in preserving.

- You can own thousands of comic books without storing them in several long boxes.

- Possible language toggle to allow owners to read comics in various languages, bringing comic collecting into a truly global market.

- They are officially licensed comic NFTs from IP holders with proof of authenticity and ownership.” (Howard 2022)

This is, of course, a highly idealized comparison that ignores the pleasures of owning and handling physical items in a collection, of participating in a long-standing community of comic book collectors, of reading trade magazines, and of the thrill of acquiring valuable floppies to expand a collection. The comparison is also somewhat disingenuous because it takes the extreme cases of the physical market—the few surviving million-dollar issues, which are, however, highly significant because they attract attention to the monetary value of “old” comics and thereby shift the validation of these comics from a qualitative to a quantitative logic—as the norm against the supposedly easy-access and no-risk NFTs. Nonetheless, this comparison shows that NFTs can be regarded as an attractive alternative or addition to the print market, and their particular digital affordances have some bearing on how people engage with superhero comics.

In the following, we will analyze non-fungible tokens as a means for comics publishers to attract attention and create value in a digital marketplace, where notions of originality, materiality, and scarcity attain a very different hue than in the heyday of print.17 Non-fungible tokens, or NFTs for short,

“allow you to buy and sell ownership of unique digital items and keep track of who owns them using the blockchain. NFT stands for ‘non-fungible token,’ and it can technically contain anything digital, including drawings, animated GIFs, songs, or items in video games. An NFT can either be one-of-a-kind, like a real-life painting, or one copy of many, like trading cards, but the blockchain keeps track of who has ownership of the file.”(Lyons 2021)18

As Patrick Rosenberger points out, “[a blockchain] works like a digital journal in which all transactions are recorded” (Rosenberger 2018, p. 63). NFTs are thus the ownership blockchain and not the artwork itself, even though they are almost always used as a synonym for the artwork. The uniqueness and non-exchangeability of tokens makes it possible to distinguish originals from copies in the digital realm. In fact, it is through these tokens that digital originals become conceivable in the first place. They are sometimes traded as a “new kind of art” and seen as part of a new “art market” (Reichert 2021, p. 7). Wolfgang Ullrich even speaks of the “gamification of art” (Ullrich 2022a, pp. 10–18) to describe the lottery principle of NFTs as well as the playful practice of making NFTs compete against each other, as in a quartet game. However, the term “gamification” entails much more. As will become clear in our assessment of the VeVe app, the respective NFT platforms and apps simulate a wide variety of ludic practices and implement a broad range of serial practices that include the collecting, archiving, and public display of superhero comics.19

All of this has far-reaching implications for the legal status of copyright and ownership, but it also adds a new dimension to the question of the value of comics. According to Kolja Reichert, whose book Krypto-Kunst (Reichert 2021) takes an in-depth look at NFTs as digital property, almost everything since 2021 has revolved around the desire for the indubitable attribution of authorship and digital ownership.20 In addition, non-fungible tokens are now also being sold by major auction houses such as Sotheby’s and Christie’s, leading Reichert to speak of a race between the “stakeholders of traditional art” (Reichert 2021, p. 9).21 However, it is apparent that purchase price and appreciation do not always immediately go hand in hand. For example, Christie’s auctioned Everydays: The First 5000 Days, a collage composed of 5000 digital images by artist Mike Winkelmann, known as Beeple, for $69.36 million (Reichert 2021, p. 7). According to Reichert, at the time, it was the “third most expensive artwork ever sold by a living artist.” Headlines such as “Beeple NFT Sells For $69.3 Million, Becoming Most-Expensive Ever”; “Beeple JPG File Sells For $69 Million, Setting Crypto Art Record“; and “JPG File Sells for $69 Million, as ‘NFT Mania’ Gathers Pace” reflect the massive public attention the sale generated (Brown 2021; Weiner 2021; Reyburn 2021). However, Wikipedia has refused to include the collage in its “List of most expensive artworks by living artists” because it allegedly is not art (Dieckvoss 2022). Such a denial of a work’s art status recalls the barriers of privilege imposed by established gatekeepers in the rejection and devaluation of comics by educational and cultural institutions throughout the 20th century—now somewhat ironically erected by the self-declared “free encyclopedia that anyone can edit.”22

The new popularity of traditionally low-impact artifacts, made possible by digitization and digital forms of communication, is exemplified by the astonishing success of the NFT collaborative animation of the British author Arch Hades’s poem Arcadia, whose publication is described as “the first time poetry was sold as fine art through the medium of blockchain” (Steiner-Dicks 2021). The nine-minute animation of the work, which features auditory support from musician RAC, was auctioned at Christie’s in November 2021 for $525,000. The news coverage of this sales success indicates a profound shift from qualitative to quantitative valuation, where popularity and price instead of literary quality appear as the most important factors in the mutual validation of NFT and poetry. “The poem is 102 lines long—making each line worth more than $5000. It is 1000 words long, so each word sold for $525,” writes Katherine Steiner-Dicks on the website The Freelance Informer on November 14, 2021, expressing surprise at the astonishing value of individual words and lines. In the following quote, Arch Hades herself puts the price of the poem first and is pleased with its successful reception. Note the absence of any qualitative—aesthetic, literary, formal—criteria:

“Now having the most expensive poem ever sold is just an incredibly surreal feeling and I’m thrilled with how well Arcadia was received by everyone. I’m hoping this inspires other women and creatives to go after whatever it is they’re passionate about, nothing is too far out of reach.”23

Arcadia made Arch Hades the “highest paid living poet of all time” (Simons 2022), with critics subscribing to (and thus also legitimizing) a quantitative scale of literary valuation that already implies the next, even more-expensive, poem. Arch Hades’s ascent confirms our assumption that NFTs generate new valences and thereby change established notions of art and aesthetic value. Whether these new valences make this poem a candidate for canonical inclusion remains to be seen, however. At the very least, its monetary success shows that the developments we are tracing are neither limited to superhero comics nor to the art world; they also encompass the field of literature and, as such, speak to more general and more encompassing transformations of the popular.

Moreover, the digital is attractive because it enables new, faster sources of income and career opportunities outside of established and perhaps more tiresome paths. Arch Hades’s poetry animation, for example, resulted from her unemployment as a book tour was canceled because of the COVID lockdowns: “Suddenly we realized, fuck, we have to make money somehow” (Simons 2022). NFTs thus offer new possibilities of self-empowerment for artists, literary or otherwise, but they do not easily fit into elitist concepts of art and do not inevitably lead to success. Nevertheless, the devaluating discourse on the popular as a commercially viable but culturally inferior (or at least not unreservedly high-quality) product—familiar from the history of superhero comics—is not simply repeated in this case. Here, the popular is admired, as the value of the poem is derived less from its literary quality than from the attention Arch Hades’s work has been able to attract. Indeed, the description of the poem’s content seems rather banal and clichéd—“Arcadia explores the concepts of modern-day anxiety and loneliness as by-products of cultural and societal constructs”; she writes poems “about love and heartache”—and is followed in the very next sentence by a reference to the bestselling status of Arch Hades’s poetry collections: “The 21st century Romantic poet has penned three bestselling poetry books despite only having written professional poetry for three years” (Steiner-Dicks 2021).24

While the art market and the literary world may still prove somewhat resilient to the advances of the popular, despite the notable successes of Beeple and Arch Hades, this does not seem to be the case in the realm of superhero comics or pop culture at large. A headline in the online industry magazine CryptoPotato (7 August 2021) that is paradigmatic for the discursive connection between auction records, non-fungible tokens, and superhero comics, reads: “Marvel Enters The Crypto Space by Releasing Spider-Man NFTs” (Dzhondzhorov 2021). With a view to the competitor DC Comics, the website Screen Rant proclaims on 30 March 2022: “Batman NFTs Officially Announced as DC Promises Relevance to Future Comics” (Isaak 2022). A bit less enthusiastically, the comics news site CBR.com reports on 16 April 2021: “Marvel and DC Crack Down on NFTs Featuring Their Characters” (Cronin 2021).

According to these reports, both Marvel and DC were quick to jump on the NFT bandwagon. This seems only logical. For one, investing in an exciting technological innovation and being at the forefront of debates about the possibilities of digital marketing and production makes good commercial sense because it generates headlines and often sensationalist reporting beyond the more limited sphere of comic book culture. The broad public attention afforded to these developments produces popularity—in the sense of free advertising, of course, but also as evidence that Marvel and DC continue to be relevant media players and that their products continue to attract consumers. Secondly, superhero comics operate on an already thoroughly commercialized terrain—perhaps in contrast to artists who are trying to establish themselves in the art market, where high-cultural aspirations may be stronger, and who are dependent on income from this market. The mainstream comic book publishers do not have the same high-cultural reputations to lose and can therefore readily utilize NFTs as a way of further monetizing flagship characters like Batman, Spider-Man, or Wonder Woman.25 It is important to note that headlines include superhero-typical talk about entering “crypto space” and what these innovations mean for “Future Comics.” Rupendra Brahambhatt and Langston Thomas even speak of a turning point on the website nft now in connection with “200,000 unique 3D-rendered Bat Cowl NFTs that will go on sale starting April 26: ‘DC Comics Believes Batman NFT Drop Will Be a “Watershed Moment”’” (Brahambhatt and Thomas 2022). References to adventures (“crypto space”), time travel (“future comics”), and earth-shattering events (“watershed moments”) activate the superhero imaginary to authorize a commercially enticing technical innovation.

With the new possibilities of digitally marketing one-of-a-kind products, the notorious battle for copyrights and exploitation rights, which had been waged vehemently and prominently by authors and artists in the late 1980s and early 1990s, also takes a new turn.26 If artists initially saw NFTs as a way to sell digitally produced drawings in the same way in which they had previously sold their print sketches or pencils, the corporate crackdown followed almost immediately, as the above-quoted headline on CBR.com illustrates.27 The article itself states:

“Comic book artists are claiming that this is depriving them of the ability to make money off of their original artwork like the two companies [Marvel und DC] have always allowed with their physical artwork, except that this is digital work and not physical, during an era where much of the art being made for comics no longer exists as pencils and ink on a page.”(Cronin 2021)

Despite the media shift from physical to digital objects, the discourse of personally attributable original artwork continues in this vein. In response to this new form of potential self-empowerment for comics artists, DC Comics announced:

“As DC examines the complexities of the NFT marketplace and we work on a reasonable and fair solution for all parties involved, including fans and collectors, please note that the offering for sale of any digital images featuring DC’s intellectual property with or without NFTs, whether rendered for DC’s publications or rendered outside the scope of one’s contractual engagement with DC, is not permitted.”(Cronin 2021)

Marvel Comics issued similar statements aimed at maintaining control over the creation and sale of NFTs, seeking to put a legal stop to the rogue sale of digitally created, digitally available, endlessly distributable, and thus extremely popularizable artifacts.

As CBR.com further reports, the well-known comics artist Mike Deodato sold work he had created for Marvel as NFTs, including the cover of Amazing Spider-Man Family #2 (December 2008). After Marvel sought to prevent this, Deodato penned an open letter available on CBR.com:

“The big comic book companies are sending letters to artists asking them not to sell their digital original art because they are copyrighted. They are asking nicely, you would say, so what is the problem? Well, they are also sending DMCA’s (Digital Millennium Copyright Act) to the platforms to stop them from selling the art.

So, let me get this straight. If you are a traditional comic book artist you can sell your original art on paper. If you are a digital comic book artist you are not allowed to sell your digital original art. In both cases, there is no copyright involved. In both cases.

So WHY digital comic book artists are being deprived of their rights? Isn’t a pandemic destroying economies and making people losing their jobs bad enough?”28

Deodato’s distinction between traditional and digital comic book artists is just as relevant in the context of our argument as his statement that both forms of artistic expression—drawing on paper with pen and ink vs. digital forms of drawing—produce art originals whose copyright lies or should lie with the artists. In both cases, he is not so much concerned with the end product (the printed or the digital comic book) than with the original artwork before its conversion into commercially available superhero fare.29 Deodato’s efforts exemplify the fact that the introduction of NFTs as a new technology and marketing tool for superhero comics is not simply a corporately controlled operation but that even within the culture industry, new opportunities to popularize certain narratives, artifacts, and actors create new conflicts and raise new questions of legitimacy. This is especially so because Deodato’s move to market and sell his artwork as NFTs sought to shortchange the comics publishers, appealing directly to fans and collectors in order to generate personal revenue—either much deserved or at the expense of the copyright holders, depending on whose argument we are willing to side with.

If we follow the critical examination of the definitions of works and their value, we may get the impression that digital works are to be denied the potential to become art objects from the perspective of a rather traditional and elitist understanding of art (especially by experts). Until the second half of the 20th century, this was the dominant view of mass culture, which positioned popular narratives and artifacts as trivial (and sometimes dangerous) consumer goods produced by a manipulative culture industry. From this perspective, the conflict between copyright and trademark holders and the artists’ desire to market their own works, which has become particularly virulent in the digital realm (Koenigsdorff 2022; Reichert 2021), has remained largely invisible. We must therefore ask how the art-related discourse of devaluation and the pop-aesthetic discourse of valorization described here are shaping the public perception of digital superhero comics with NFTs and also which transformations we can trace from the old high/low distinction to new forms of popularity determined by second-order popularization.30

3. Marvel and the Marketplace App VeVe

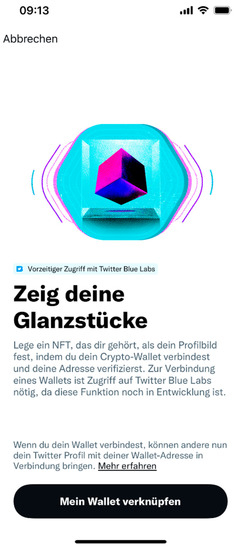

The implications of these questions are already being practically tested by some platforms. On 20 January 2022, Twitter released the feature of issuing a self-owned NFT using a cryptowallet’s31 connection through a hexagonal profile picture, as we can see in a screenshot taken from a German location (Figure 1).32 Because this was interpreted both as an experiment and as a sign of exclusivity, this service was only available to paying members of the Twitter Blue Labs service, which was, until recently, unlocked in only a few countries.33 The hexagonal avatar differs from the regular, Twitter-standard circle shape. Clicking on it will yield additional information: Designer, Owner, Description, Collection, Property, NFT Details, NFT Definition (Figure 2). Furthermore, it offers a redirection to certain marketplace platforms, where the presented NFT may be purchased by the current owner. The platform OpenSea, which is also used by Christie’s, is a good example in this context. In order to create a sense of viability, this marketplace lists its “top NFTs” according to “volume, floor price and other statistics”; like a stock exchange, it indicates the daily performance (OpenSea 2023).34 The ranking does not include individual works, only collections. As already mentioned, such rankings also represent a unique feature on Twitter. This means that the collaboration and presentation of this new form of digital trading of art not only leads to prestige and an increase in the value of artists or buyers but that it also unlocks the serial dynamics of collecting.

Figure 1.

Twitter informed all users about the new NFT feature in 2022, although Twitter Blue Labs was not yet available in Germany.

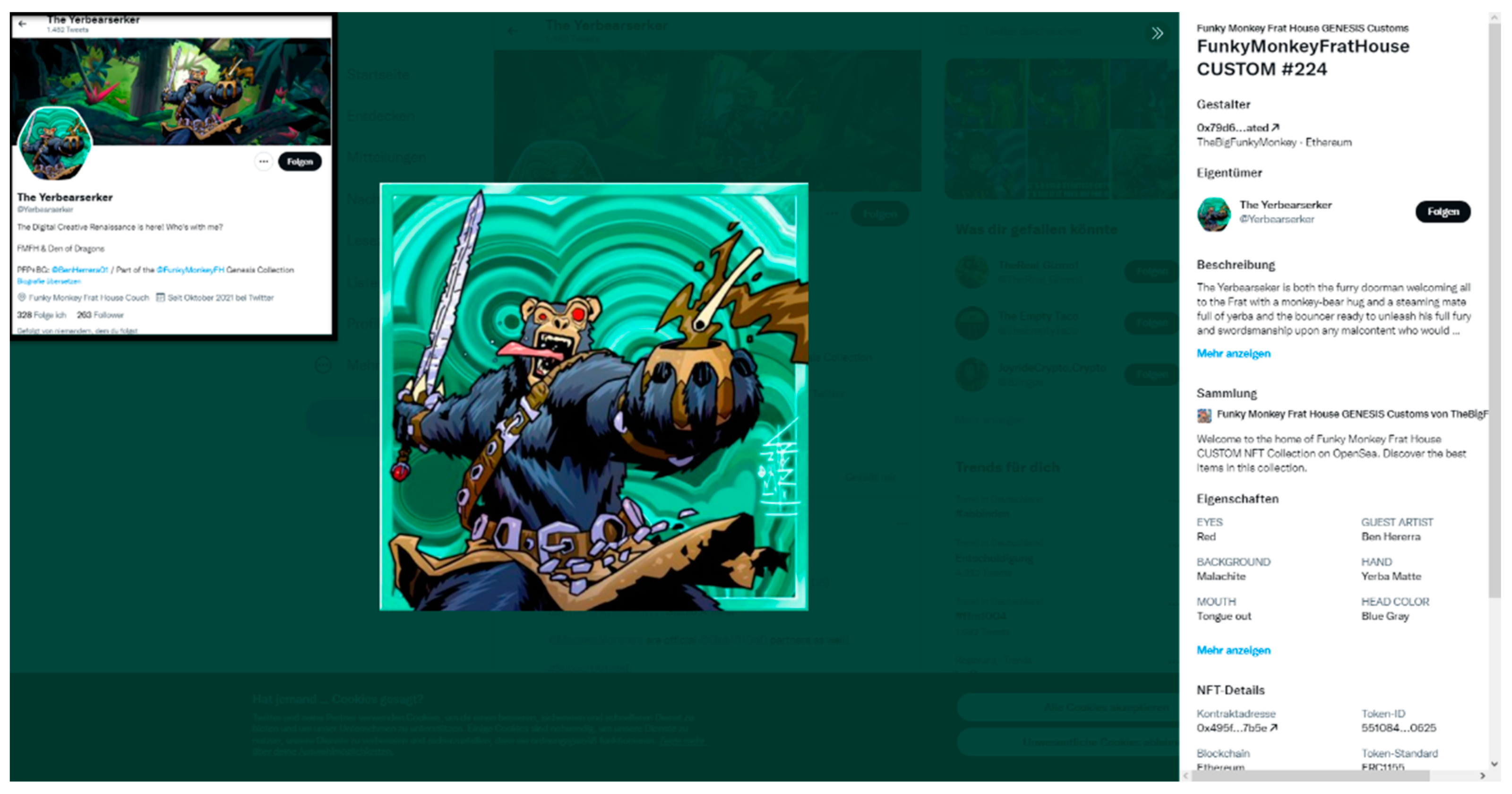

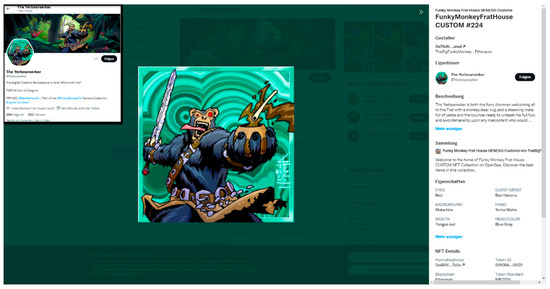

Figure 2.

Clicking on the Twitter profile picture not only enlarges the NFT but also displays information about it, as this example from @Yerbearserker shows.

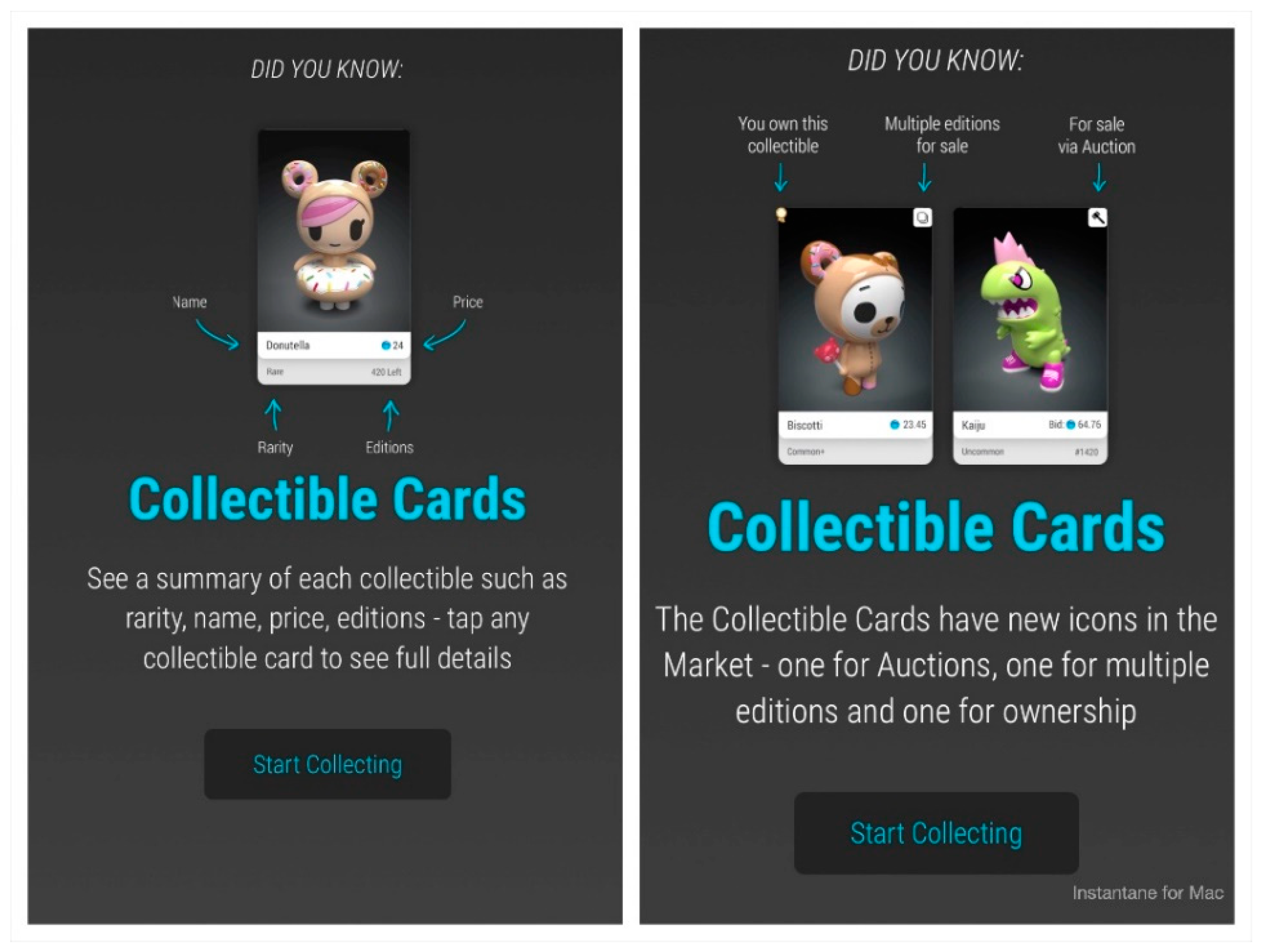

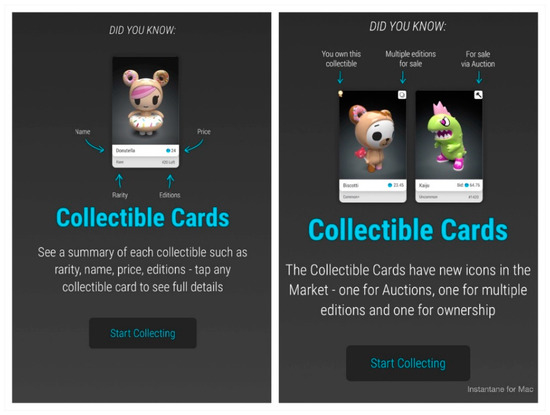

Considering the fundamental connection between seriality and collecting, it makes sense that companies like Marvel and DC are investing in NFTs.35 DC Comics offered certain NFTs to members of DC FanDome and to “all fans who share on social media” (DC 2021)36 in December 2021, while Marvel partnered with the marketplace app VeVe in August 2021 (this app could only be used on smartphones until June 2022).37 VeVe was launched in 2020 and offers the purchase of exclusive and limited comics and collectibles (pictures, figures, stamps; also of Disney, Coca Cola, or DC characters (ECOMI 2020a, 2020b) through NFTs. The name, list price, and degree of rarity of these NFTs recall trading cards in their presentation and aesthetics, and they are designated as such by VeVe itself (Figure 3). The app thus fits in with the bestsellers on the NFT market, as the success of so-called CryptoKitties trading cards shows (Fadilpašić 2020).38 Like at a swap meet, the NFTs on VeVe can be resold or auctioned off after an auction.39 Whereas readers and fans in the past flocked to flea markets, comics conventions, and the back issue bins of comic book stores to complete their collections, they now engage in online practices like offering, auctioning, and comparing digital artifacts.

Figure 3.

Logic and aesthetics of the trading cards on VeVe.

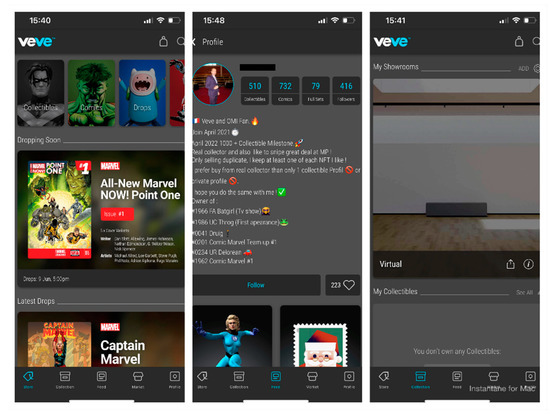

The app also has a social media-like feed where likes, comments, and follows can be assigned. Users further receive a modifiable profile that can either remain private or be made public. In addition to the avatar and the account name, the number of collectibles, comics, full sets, followers, and likes is displayed for everyone in mobile use; in the web app, comics and collectibles are combined, and the registration date and the number of follows can be viewed. This means that the app’s automated attention measurement not only records and presents the popularity of individual NFTs but also specifies the degree of their owner’s popularity. This is yet another example of what we are calling second-order popularization: Being active on the app not only means gathering collectibles and becoming a respected collector, it also creates popularity (or non-popularity for those who are not noticed or liked by many). Public profiles can also display their collection cards. The display of property and collections (full sets) is accordingly an essential component of the app—and shapes the initially primarily privately practiced prestige experience of the owner into a public event.40

This is further reflected in VeVe’s planned Master Collector Program (VeVe 2021). This program offers a reward system well known from fan forums. Every activity and every purchase allows users to visibly advance in level and rank by amassing points. They can also earn badges and receive certain privileges with each level up, such as access to drops before the official release as well as exclusive chances at limited editions.41 Complete collections and rare NFTs score more points.42 This is not just a “gamification of art” in Ullrich’s sense but also a gamification of collecting, exhibition, and advancement practices prevalent in video and online games, in the sense of adapting ludic principles in game-unique spaces.43

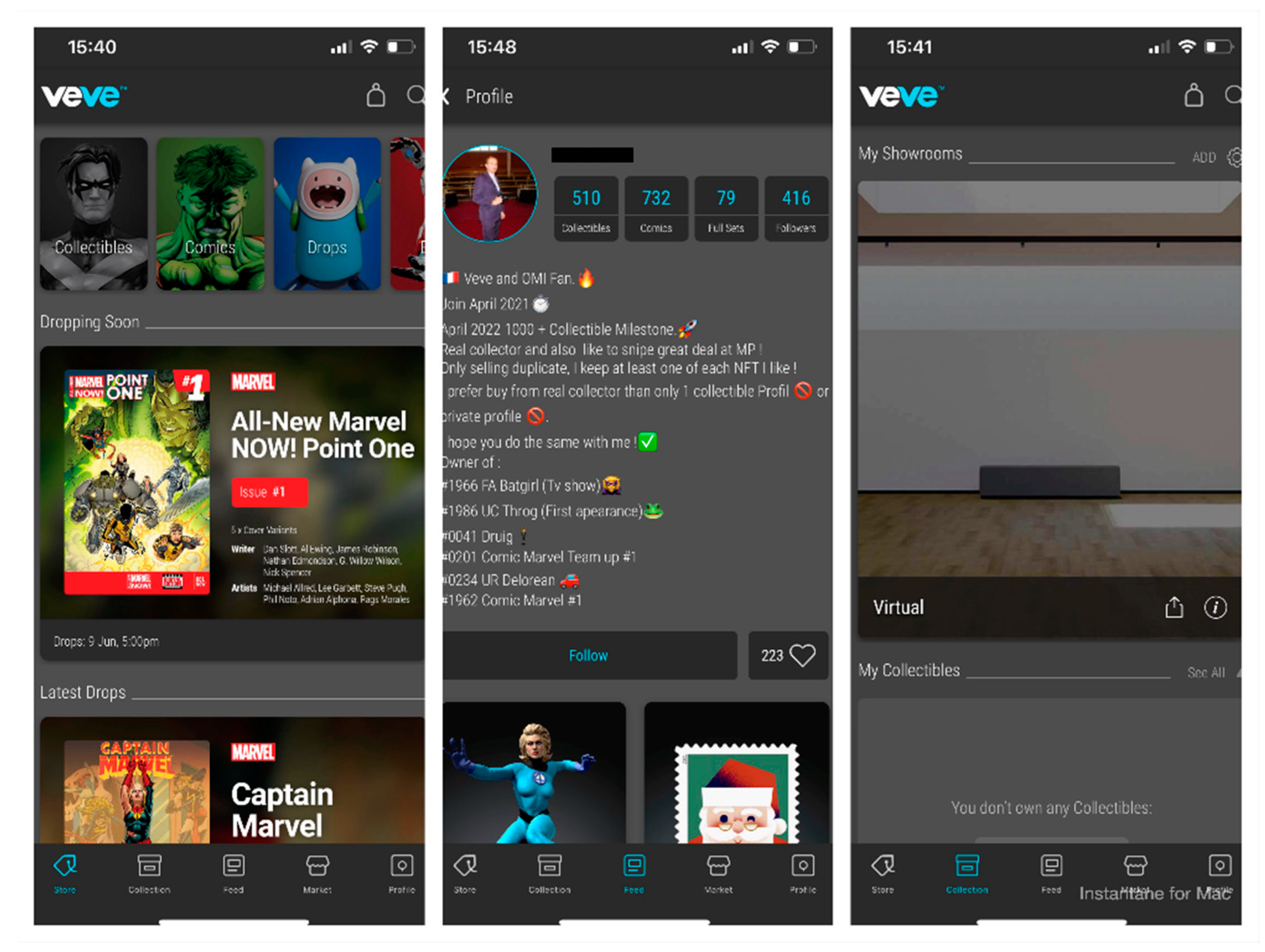

In addition, VeVe has a private “My Showrooms” feature (Figure 4). This allows purchases to be displayed in a visual space (usually a vault). By connecting to a smartphone or VR camera, these spaces can also be transferred to the “real” world and can be shared with everyone in the feed. Digital collectibles, which users previously could own only as files on their home computers and, at most, present in forums and on fan websites, are thus given the status of originals and a “physical” as well as official exhibition space (Stevens and Bell 2012, pp. 751–72; Steirer 2014, pp. 455–69).

Figure 4.

VeVe: example of the home page, a profile, and an empty collection showroom.

In its NFT offerings, Marvel mostly includes older, already published single comics44 for the price of 6.99 Gems (1 Gem equals 1 USD).45 The exclusivity of this offer (the base unit is, after all, Gems) is reflected in the fact that comics can be purchased that are hard to come by in print due to their rarity and that, should they be pristine or near-pristine copies, would auction for several million dollars (such as The Amazing Spider-Man #1, 1963; Fantastic Four #1, 1961; Marvel Comics #1, 1939).46 In addition to first or special (i.e., “key”) issues, the app features first appearances of popular characters such as Scarlet Witch, Ms. Marvel, Falcon, Loki, and She-Hulk.

The primary sale of single issues could be understood as a focus on (popular) individual works rather than a focus on (popular) series or artworks. However, each comic comes with a choice of five cover versions. At first glance, this is reminiscent of the variant covers that were especially popular in the 1990s and were intended to make comics collectible and attractive as investments, leading to a short-term speculators’ boom. The VeVe strategy is similar. Cover selection in digital comics has not been a common feature, unlike in their print counterparts today. This may be related to the fact that they are denied a collectible value, as they have had no true/aesthetic exhibition space thus far and are essentially identical mass-produced items in potentially unlimited supply. Each specimen corresponds to a “near mint”/“gem mint” condition. There is no uniqueness equal to an original, nor is there technically a need for rarity. To make digital comics attractive as collectibles, the digital transformation into a unique, non-exchangeable token is therefore of eminent importance. The VeVe app also plays a part in this transformation, as its exhibition space turns the initially disposable digital copy into a perpetually presentable mobile archive.47 VeVe also exhibits exclusivity through the first-ever collectible cover variants, which are not infinitely available but rather strictly limited. This limitation affords the comics a particular rarity value that, as we have already noted, leads to advancement in the app’s reward system.

The rarity values of the cover versions offered on VeVe are distinguished by the labels “common,” “uncommon,” “rare,” “ultra rare,” and “secret rare,” which are taken from the collectors’ market of the print editions.48 Marvel also refers to them as “classic cover” as well as “vintage,” “hero,” “vibranium,” and “true believer” variants.49 These covers are designed specifically for VeVe as “exclusive” and thus perform new paratextual work for an otherwise consistent text. According to the French narratologist Gérard Genette, the paratext serves to make the initially naked text publishable and readies it for circulation. Page numbers, chapter headings, title images, interviews, or the like, which are incorporated as peri- or epitext depending on their distance from the text, are indispensable for the publication of a work, but they are conventionally considered rather insignificant accessories to the literary text (Genette 1997, pp. 1–15). This changes with the collective logic of NFT comics on VeVe, where paratext morphs from an often-assumed interchangeability to a prestigious work of art, shifting the focus of the original text-based series to a paratextual seriality.50 It is, after all, the covers of an issue that are seen as collectible, and not the text, which is always the same.51

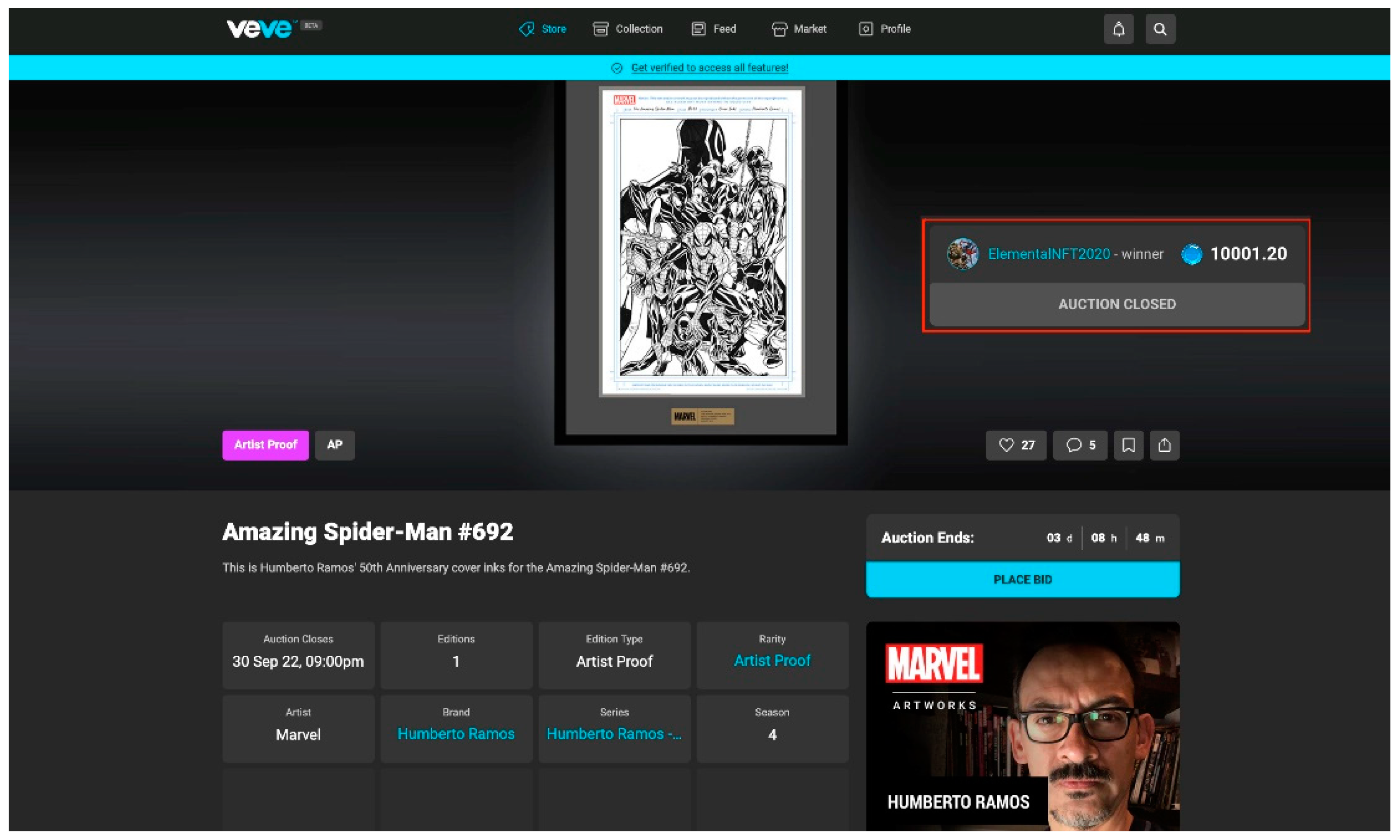

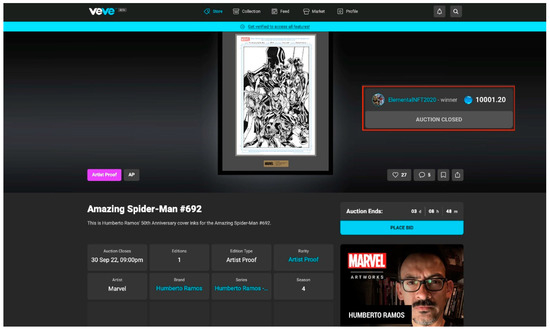

The app reinforces this impression by highlighting the collaboration with selected artists with a note that “[t]he release features VeVe-Exclusive Rare & Secret Rare covers by….” Since September 2022, this concept has been expanded with the introduction of “Marvel Artworks” in the VeVe Web App: The artworks are exclusive covers created by artists for existing comics, but not entire issues that can be purchased in silent auctions and cannot be resold afterwards.52 These are given the rarity grade “Artist Proof” (Figure 5). In most cases, the artwork is designed by the original cover artists of the respective issues and exists only as a single copy. Interestingly, the artists are not listed under “Artist” but under “Brand” as well as “Series” and listed with “Season,” as can be seen in Figure 5. As shown above, serial processes are unlocked through these forms of digital collecting. However, we may still wonder about the hierarchical structure that positions publishers versus artists, since “Artist Proof” refers to Marvel in the VeVe logic and “Marvel Artworks” frames the profile images of the designers. While artists in contrast to the publisher are given their own VeVe profile to highlight the value of their previous work, the Marvel logo is also present there (VeVe). The covers are auctioned at high prices, so this process can be compared to the well-known auctions of more traditional works of art (Figure 5). (VeVe Digital Collectibles 2022a; VeVe Digital Collectibles 2022c).

Figure 5.

Marvel artwork of Humberto Ramos’s Amazing Spider-Man #692 auctioned for 10001.20 Gems (see inserted red box at top right).

Enhancing the paratext of regular comic book purchases, VeVe also includes nearly forgotten peritextual elements such as editorials (Fallen Son: The Death of Captain America #4) or letters to the editor (Ms. Marvel #16). In digital reissues, these elements are usually omitted or included only irregularly or arbitrarily. However, such letters are crucial if we want to study a series’ evolution, its fluctuating popularity, and thus also its history before the shift to the more dynamic world of online communication. As Frank Kelleter maintains about popular serial narratives, “[l]ooking at individual texts often doesn’t make sense” (Kelleter 2012, p. 15). Moreover, due to the limited page range of the printed comic book, the publication of the letters was considered a privilege because they made readers visible within the comics community and offered them a way to distinguish themselves as critics. However, the digital invisibility of this peritextual communication erases crucial forms of “participatory culture” (Henry Jenkins’s term) and thus also delimits its value (in the sense of a decrease in “cultural capital” in Pierre Bourdieu’s sense).53 The staging of rare peritexts in digital VeVe reprints, however, gives them a new status since it is above all the exclusivity of the paratexts that endows the digital comics with a new value, which is expressed in the price and attention standards described above.

As already noted, NFT comics are strictly limited precisely because it is their artificial scarcity that makes them rare and thus potentially valuable. If they are available at auction, all interested parties can see both the number of copies in stock and the likelihood of purchasing a particular cover; after that, they only see the likelihood and the list price. However, buyers cannot choose which issues of the comic book they purchase. VeVe uses a “blind box format” that randomly distributes the covers after the payment process.54 This leads, at least initially, to an increase in the value (and exclusivity) of collectibles (or series) and their resales. Each day between 11 April and 15 April 2022, Marvel offered for sale on VeVe one issue of the five-issue miniseries Fallen Son: The Death of Captain America. Each issue inventory ranged from 20,900 common cover, 4900 uncommon, 2200 rare, 950 ultra rare, and 500 secret rare.55 The nearly 30,000 issues usually sold out in a minute (which was the norm for app offerings at the time). The demand for such offers is high and leads to an automated popularity of the respective issues, especially since there is a possibility to snatch a comic whose market value is much higher than the low price of 6.99 Gems.

In connection with the transparent rarity and the promising status of a “true believer,” acquired issues are traded at a higher price. A common cover usually sells for less than the original price of 6.99 Gems. This is largely analogous to the resale value of a common print copy (issue #1 from 4.95 Gems, #2 and #3 from 4 Gems, #4 from 3.88 Gems, #5 from 3.90 Gems). Issues rated ultra rare or secret rare are usually advertised at larger amounts (ultra rare: #1 from 50 Gems, #2 to #4 from 30 Gems, #5 from 47 Gems; secret rare: #1 from 119 Gems, #2 from 160 Gems, #3 and #4 from 95 Gems, #5 from 90 Gems). Special comics that auction for more than $1.5 million in print also receive a higher starting bid at VeVe: The Amazing Spider-Man #1 was offered in April 2022 with a common cover from 85 Gems, an uncommon cover from 130 Gems, a rare cover from 285 Gems, an ultra rare cover from 619 Gems, and a secret rare cover from 8999 Gems. However, it seems that the economic value of the NFTs decreases with an increasing temporal distance to the offer, in a somewhat counterintuitive development that we want to ponder in the concluding segment of this article. For example, an ultra or secret rare cover of Fallen Son in November 2022 is already available between 15 and 42 Gems in the Market. The covers of The Amazing Spider-Man #1 with the same rarity markings can be purchased from 145 and 1500 Gems at the same time.56 In this sense, NFTs behave almost contrarily to their print counterparts. It seems that the value of the NFTs tends to decrease, while the value of the print editions increases in relation to their rarity. This finding may initially come as a surprise because unlike the rare comic books discussed at the beginning of this article, which can only noticeably increase in value if they resist natural aging and the wear and tear of reading and storing, NFTs do not have this problem. As digital artifacts whose sales and purchases are documented in their blockchain and which thus acquire a certain historicity, they nevertheless (at least ideally) always remain pristine.57 However, unlike the print floppies, which are now considered classics of the genre, they cannot look back on a long and stable past. Whether a particular NFT work will ever prove to be particularly popular in the long run or formative for a whole generation is unclear at this point. The entire phenomenon is too new and perhaps also affected too much by the vagaries of public attention. Moreover, in the case of the artificial scarcity of Marvel offerings on VeVe, NFTs ultimately remain latently precarious—we can only speculate whether artificially scarce and thus rather valuable NFTs (e.g., variant covers) will not be devalued either by the possible fading of the current NFT hype or by new forms of subsequent duplication.58

4. Conclusions

As we have seen, the artificial exclusivity of NFTs has increased the popularity of an already popular medium in the digital space and has equally enhanced and transformed its art potential as well as its paratextual features. Our prime example, the VeVe app, has adapted and appropriated elements of gamification, such as reward and ranking systems already established in videogames, as well as practices for highlighting success (in the sense of transforming the popular). In addition, second-order popularization is enabling new concepts of artistic and commercial valence, especially in digital spaces previously associated primarily with the realm of the “high” (auction houses invested in the sale of art and rare goods). Second-order popularization is thus appealing to traditional institutions of high culture. Since NFTs, unlike their physical counterparts in the blockchain, archive all transactions and document all previous owners, artists, universities, and museums are also embracing this technology (Tonelli 2022). This is because they can invest not only in exhibitable originals but also in information of an individual, automated, digital as well as mobile archive.

Despite these developments, we must still ask what would happen to these blockchains, their exhibits, and their monetary value should the Marketplace app or the associated wallet cease its digital existence. In the case of VeVe, the merchandise cannot be downloaded, and it is forbidden to share and sell merchandise purchased there on other platforms; even the attempt is punishable (VeVe 2023a). In addition, Marvel usually does not make the paratextual exclusivity prepared there available for other formats. Based on our analysis of the VeVe app, we can conclude that the breakdown of the high/low axiology in favor of a new understanding of art and the popular as being primarily characterized by conflicts over copyright and ownership—as well as by digitally mediated possibilities of acquiring, collecting, exhibiting, and acting—enables new axiologies in what occurs to us as a more or less exclusive digital space. The app cannot be accessed without registration. Users must verify themselves in order to access all functions. Sharing materials outside the exclusive space is not integrated into the logic of the app. The digital world offers more and more opportunities to acquire, collect, and exhibit artifacts designated as originals. In the context of superhero comics, however, the affordances of the digital are primarily used to drive the second-order popularization that is attractive for the commercial development of the genre and, in conjunction with the sales records of rare comic books and the almost ubiquitous transmedia presence of the characters, to ensure getting noticed by many.

However, there is a proverbial elephant in the digital room: the recent waning of the NFT craze and of the public enthusiasm this new media form was able to generate only a very short time ago (in 2021 and early 2022). Writing before the introduction of NFTs but with a focus on more than a decade of attempts by comics publishers to utilize the affordances of the digital to increase comic book sales without hurting the more lucrative print market, Alisa Perren and Gregory Steirer remained doubtful about the impact of the digital sphere on comic books. The authors maintained that “the advent of digital distribution technology has had relatively little effect so far on how the comic book industry functions and how it is comprised” (Perren and Steirer 2021, p. 196). In light of this assessment, it may not be surprising that we are currently caught up in the midst of what seems to be an NFT blues, a moment when initially successful and popular NFTs are losing worth and when the market seems to be shrinking, rather than expanding, while the print market continues to thrive. In 2021, Stephanie Chan wrote on the website Sensor Tower that “VeVe Collectibles Leads NFT Trading Space on Mobile with More than $100 Million in Consumer Spending” (Chan 2021). The article includes a graph that visualizes the immense and rapid increase in NFT spending, showing the explosion of expenditures on VeVe from 13,000 USD in January 2021 to 34.5 million USD in November of the same year. However, writing less than a year later, the author Ariel noted on the website Appfigures that “NFT Marketplace Veve Collectibles Revenue [Was] Down 84% in 2022” (Ariel 2022), indicating that NFTs may already have become “old news.”

Looking back at the history of superhero comics, its various fads, and the general fickleness of popular markets, however, we would argue that it is still far too early to forecast the end of NFTs—popular genres have a way of maximizing attention, either through short-term efforts (which the NFTs may or may not be) or through ongoing adaptations to changing media constellations. “Is it still worth getting into Veve?”, one member of the Reddit group “VeVeCollectables” asked in spring 2022, to which another member replied: “If you believe in the value proposition of owning the first ever licensed NFTs from Disney, DC, Marvel, Star Wars etc and you have the money to comfortably purchase some of the ‘grail’ pieces and don’t mind sitting on it for the long term, I’d say sure” (VeVe Collectables 2022). It would not be the first time that fans rescued a commercial product or once-popular form from oblivion by paying lasting attention to it. If many of the buyers are fans—and will therefore continue to collect even after the craze is over—and if the artificial scarcity of the NFTs keeps prices somewhat stable, the NFT phenomenon is not all that different from the old and precious, “rare” comic books. Even if the fans do not save the superhero NFTs, it appears that these NFTs will nevertheless end up promoting the popularity of comics publishers like Marvel, as generating news stories and sensational headlines is conductive to increasing attention to the company’s latest attempts to adapt their products to the demands of a constantly changing mediascape.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, D.S., L.D.H. and A.D.; methodology, D.S., L.D.H. and A.D.; writing—original draft preparation, D.S., L.D.H. and A.D.; writing—review and editing, D.S., L.D.H. and A.D.; funding acquisition, D.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This publication is part of the subproject A01 “The Serial Politics of Pop Aesthetics: Superhero Comics and Science Fiction Pulp Novels” of the Collaborative Research Center 1472 “Transformations of the Popular”, funded by the German Research Foundation (Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft; Project ID 438577023—SFB 1472).

Acknowledgments

Many thanks to Niels Werber and to the anonymous peer reviewers for their valuable comments.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Notes

| 1 | All originally German-language quotations were translated by the authors of this article. This article emerges from our research project (with Niels Werber) “The Serial Politics of Pop Aestehtics: Superhero Comics and Science Fiction Pulp Novels,” which is part of the Collaborative Research Center Transformations of the Popular, funded by the German Research Foundation (DFG). |

| 2 | For evolutionary readings of superhero history, see Lopes (2009); Stein (2021a). Perren and Steirer (2021, chp. 6) provide an evolutionary framework for understanding the development of the digital production, distribution, and reception of comic books, which begins with an experimental/pre-market phase before 2007, continues with a market-making phase between 2008 and 2011, enters a phase of consolidation from 2012 to 2014, and culminates in the still ongoing monopoly phase from 2014 onwards. |

| 3 | Key issues, or “keys,” are, for instance, “a #1 comic, a 1st appearance, death, or other significant event)” (Comic Spectrum.com 2018). |

| 4 | We base our understanding of pop aesthetics on some of the parameters identified by Thomas Hecken, including consumerism, artificiality, and superficiality (Hecken 2013). Further reflections on the appeal of speculation are provided in Stäheli (2013). |

| 5 | Astonishment at the monetary value of older comic books is not a recent phenomenon. On 6 December 1964, the New York Times printed the short article “Old Comic Books Soar in Value; Dime Paperbacks of 1940’s Are Now Collector Items” (New York Times 1964), which inspired similar reporting around the nation. However, the prices that the coveted 1940’s comics used to fetch in the 1960s were very moderate (between $2 and $25) compared to today’s auctions. For an in-depth discussion, see Stein (2021a). |

| 6 | See also Jules Feiffer’s comment: “Comic books, first of all, are junk. Junk is there to entertain on the basest, most compromised of levels. It finds the lowest fantasmal common denominator and proceeds from there. […] Junk is a second-class citizen of the arts; a status of which we and it are constantly aware. There are certain inherent privileges in second-class citizenship. Irresponsibility is one. Not being taken seriously is another” (Feiffer 1965, p. 186). |

| 7 | On questions of cultural value, or symbolic capital, in the field of US comics, see Beaty and Woo (2016, pp. 1–4), who argue that cultural value is not intrinsic to a comic but is assigned by reading communities aiming to define excellence or greatness. In the context of our argument, quantitatification is part of this endeavor even though it is not always recognized as such. The excellence of a popular, i.e., much noticed, bestselling, creator or comic takes on a different quality when readers are aware of this popularity. Popularity might even be cited as evidence of excellence—how could thousands or millions of readers who like a certain comic book be wrong about its worth? |

| 8 | Fortune Business Insights provided the following figures in January 2021: “The global comic book market is projected to grow from USD 9.21 billion in 2021 to USD 12.81 billion in 2028 at a CAGR of 4.8% during the 2021–2028 period” (Fortune Business Insights 2022). The Marvel Cinematic Universe has grossed more than $25 billion since it was launched in 2008 (Clark 2022). |

| 9 | A total of approximately 600 million Superman comics were sold between 1938 and 2015 (Statista Research Department 2015). |

| 10 | Concerning the normative pejorative discourse around the concept of “mass culture,” for instance, in Dwight MacDonald’s “A Theory of Mass Culture” (MacDonald 1953), Thomas Hecken writes: “Mass culture is considered here above all as the lower than the bad culture. It is the negative foil of high culture […]. If one adheres to the influential art critic Clement Greenberg, the products of mass culture are the ‘kitsch’ that lags behind the ‘avant-garde’ of genuine art by a wide margin—as a poor and standardized copy” (Hecken 2010, p. 205). |

| 11 | See statements by Jack Kirby, the illustrator of the first Captain America issues in the early 1940s and later of the Fantastic Four and several other superhero comics, about the collaborative production process: “I believe we were professionals […] who had something to give to each other that culminated in a product worth selling. Joe [Simon] and I manufactured products worth selling. And they sold. They sold a lot.” And: “[A]t the time I really didn’t want to be a Leonardo da Vinci. I didn’t want to be a great artist, but I loved comics and wanted to be better than ten other guys” (Eisner 2001, pp. 197, 199). Kirby values comics as professional works but does not see them as art (yet). For detailed studies of the self-understanding of succeeding generations of comics artists, see Lopes (2009); Gabilliet (2010). |

| 12 | The problem of preservation in the case of early comic books is exacerbated by the fact that, in addition to the low paper quality with its tendency to fade and degrade fairly quickly, fans could not rely on the kind of collectors’ equipment that would have allowed them to store the comics in the best possible way. See also the advice offered in an article on “slabbing” on Comic Spectrum.com, which defines this term as “slang for getting a comic professionally graded and encased in an un-openable hard plastic shell from CGC, PGX, or CBCSthe” and suggests to the interested comics collector that, once a comic has been slabbed, “you never want to physically touch that book again. Any kind of handling could easily drop a grade” (Comic Spectrum.com 2018). |

| 13 | This includes voucher copies that did not even go on sale. Less-than-pristine copies can, of course, also fetch thousands of dollars, which means that even copies that show significant use can mark the discrepancy between their cheap original price and their current monetary value. However, the sale of such copies is not newsworthy enough for major news outlets to report on, which means that they do not quite serve as agents of second-order popularization as the highest-selling issues that are making the headlines. |

| 14 | Important introductions to the cultural history and narrative specifics of popular serial storytelling are Kelleter (2012, 2017). |

| 15 | Bart Beaty examines the inclusion of comics in the catalogs of such prominent auction houses and analyzes the resulting cultural appreciation (Beaty 2012). A near-pristine version of Action Comics #1 sold for $3.2 million on eBay in August 2014 (Roe 2014). |

| 16 | The “classics” of the genre reappear in numerous anthologies and collected editions, and they can be purchased as digital issues directly from the publishers, via online bookstores, or as a bundle with thousands of other issues on a subscription basis (e.g., Marvel Unlimited). Many of the issues are also available on more or less legal websites. However, most of the paratexts that are relevant for collectors and for us as researchers are missing, including editorials, letters to the editor pages, publication announcements, and advertisements. |

| 17 | In the 1990s, when the major auction houses offered individual comics as well as entire comic book collections, so-called pedigree collections, i.e., collections of rare and very well-preserved comics, were also referred to as “blue chip comics” and thus marked as particularly valuable (Beaty 2012, pp. 163–67). |

| 18 | See also Reichert’s definition of NFTs as “digital certificates of ownership with tamper-proof record in the blockchain” (Reichert 2021, p. 8). |

| 19 | Ullrich’s comments on the 2021 raffle of works by British artist Damien Hirst, who added NFTs to 10,000 dotted original paintings and raffled them off for $2000 each, are also relevant. Over a period of one year, buyers could choose either the (material) painting or the (virtual) NFT (Ullrich 2022a, p. 12). Ullrich therefore speaks of two markets and maintains that we cannot foresee which one of them will prevail. In the meantime, the first findings on the decisions of the buyers are already available: “5149 people exchanged their NFT for a […] painting […] 4851 [NFT are] still in circulation.” See also Hitz (2022). On these developments, see also the following lecture by Wolfgang Ullrich in the context of the CRC 1472 Transformations of the Popular: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=z11HiNhSvnM (Ullrich 2022b, accessed on 30 October 2022). |

| 20 | See the podcast “NFTs—Spiel, Hype oder gigantisches Schneeballsystem?” (Mannweiler and Kremer 2022) as well as (Meier 2021). In addition, a major event series for “NFTs in art and culture” was held for the first time in German-speaking countries in May 2022 (Vogel 2022). |

| 21 | Sotheby’s has its own platform for crypto art (Dieckvoss 2021); in September 2022, Christie’s launched “Christies 3.0 [a]s a fully on-chain auction platform dedicated to exceptional NFT-based art” (Christie’s.com 2023). The platform can be accessed at https://nft.christies.com/ (accessed on 8 February 2023). |

| 22 | The privileged position within art is also reflected in the fact that only a few can work full time as artists and be successful. Therefore, they often do not describe themselves as artists, as has already been shown in this article by the classification of comic actors as craftsmen. |

| 23 | Arch Hades mentions other artists, but again, the focus is on measurable success rather than artistic innovation and brilliance: “Then to have our work selected by the world’s leading art auction house for such a prestigious sale alongside titans like Doig and Hirst, is something I never thought was possible for me” (Steiner-Dicks 2021). |

| 24 | Arch Hades’s poetry can be categorized as an example of what Moritz Baßler labels “midcult.” See, for instance, Baßler’s observations on the most successful poetry collection in literary history, Rupi Kaur’s milk and honey (Kaur 2014). With a view to Kaur’s millions of Instagram followers and the discrepancy between literary-critical doubts about the quality of the poetry and the masses of anthemic lay reviews on platforms like Amazon and Goodreads, Baßler writes: “[S]ocial media and the interactive Web 2.0 are not only overriding professional gatekeeper functions on the reception side; something similar is already happening in production.” Kaur had initially published her poems on Instagram and found a publisher due to the attention she received there (Baßler 2021, pp. 132–49). |

| 25 | Conversely, one could argue that popular series and their aesthetics have always contributed to the legitimization and popularization of new media (Hagedorn 1988, pp. 4–12). |

| 26 | This struggle came to be known as “creators’ rights,” including coverage in The Comics Journal #137 (9/1990), which features interviews with Steve Bissette and Scott McCloud as two key representatives of this movement and reprints the transcript of a panel discussion titled “Creator vs. Corporate Ownership”. |

| 27 | Precisely because comic artists were generally not granted copyrights to their work for the major publishers until at least the 1990s, the sale of original drawings is considered an officially tolerated way of generating additional income, even though it involves protected content. This is also due to the fact that these drawings, as already noted, are not originals in any conventional sense but templates for an industrially shaped end product. |

| 28 | One solution to this problem is the time-consuming and labor-intensive creation of entirely new characters and content, as Rob Liefeld, known for his work for Image Comics, plans to do (Epps 2022). Where Liefeld envisions a whole new superhero universe, renowned comic book artist Alex Ross is invested in the establishment of “a permanent digital archive of [his] lifetime of work” (Colivingvalley.com 2021). |

| 29 | Spider-Man and other popular serial characters are trademarked intellectual properties, so this is not necessarily a copyright issue. Therefore, the artists do not have the right to sell their drawings without the consent of DC or Marvel. See also Gordon (2013, pp. 221–36). |

| 30 | It is important to stress that we are not so much interested in market analysis or investigating Marvel’s digital business models than in the ways in which the app creates new possibilities for buying, trading, and collecting digital “originals” and how the aesthetics of the app as well as the discourses surrounding the introduction and promotion of superhero NFTs indicate the transformation from qualitative to quantative regimes of valuation, including a shift from the older high/low logic to a new popular/non-popular logic. For more on these changes, see Döring et al. (2021) as well as Werber et al. (2023). For an astute and well-researched history of comic book publishers’ evolving investment in the digital distribution of comics, see Perren and Steirer (2021, chp. 6). As these authors indicate, digital distribution—for instance, via subscription-based platforms such as DC Universe or Marvel Unlimitted—has not yet surpassed the print market, which continues to dominate the sale of superhero comics. |

| 31 | In a cryptowallet, the password-like keys to the blockchains of the respective owners are stored and thus make transactions possible. |

| 32 | See Twitter Blue (2022). Instagram followed in May 2022 (Stuttgarter Nachrichten 2022). Since we are based in Germany, we sometimes reference the platforms as they appear for German users. |

| 33 | Since Elon Musk’s acquisition of Twitter, this practice has changed (Spiegel Netzwelt 2022). |

| 34 | See the collection statistics on the Opensea platform. On lists as a characteristic phenomenon of the popular, see Schaffrick (2016, pp. 109–25); Adelmann (2021). |

| 35 | For a broader context, see the chapter “Collecting Comics: Mummified Objects versus Mobile Archives” in Stein (2021a). |

| 36 | In the context of the FanDome (October 2021), DC made “selected” covers available free of charge for this period in cooperation with the Palm NFT Studio platform. Interested users had to register or be registered (on both platforms) to receive one (maximum two) random NFTs. Since mid-2022, DC has been trying to establish its “own marketplace,” also in cooperation with Palm NFT Studio (currently, however, this is still in the BETA phase). It is reasonable to assume that DC has made attempts in the context of FanDome to generate attention and gain users in advance, as well as to test the popularity or success of the NFTs first. Examples are (DC Universe 2023; Downing 2021; Ledger Insights 2022; Daz3D 2022). |

| 37 | Beyond VeVe, Marvel is also collaborating with NFT artists and creating its own comics with them (Marvel Entertainment 2022). In addition, Marvel is promoting other exclusive NFT offerings via the late Stan Lee’s account, which will be posthumously used by Marvel (Lee 2021) and BeyondLife.club and Orange Comet Launch Stan Lee’s Chakra The Invincible NFTs (BeyondLife.club 2022). |

| 38 | According to Reichert, the market is dominated by sports trading cards (Reichert 2021, p. 24). Sports trading cards and superhero comics have had a close relationship since at least the 1980s. Starting in the 1990s, the industry magazine Wizard reported on the cards and comics, among other things, as well as on movies and computer games (Beaty 2012, p. 168). The Italian company Panini is a good example, as it still publishes both comics and sports trading cards. |

| 39 | Usually, the market is closed 30 min before and after a drop so that the app can adjust to the traffic. However, with the constant software development, the time-out is more and more suspended, which could also refer to a decreased popularity of the app (VeVe 2023b). |

| 40 | It should be noted, however, that “public” by the act of registration refers to a public that is not open to everyone. In July 2022, VeVe also introduced KYC (Know Your Customer). This is a verification system designed to confirm the identity and address of users in order to protect them from “fraud, corruption, money laundering and terrorist financing.” Only after verification are the app functions available to users (VeVe Digital Collectibles 2022b). |

| 41 | Kerkmann writes: “An NFT Drop refers to the release of an entire collection of unique trading cards, objects, or artwork. Usually, new NFT collections are announced with some lead time before they are finally minted and distributed to buyers. The term ‘minted’ refers to the process of transferring an NFT to a blockchain. A drop usually includes the entire collection of an art series or specific trading cards, but can also consist of just a single NFT” (Kerkmann 2022). |

| 42 | Ullrich touches on the topic of user behavior (with reference to game theory) on the online platform Discord: “They meticulously study their sheets to discover value-enhancing features. And, of course, they observe the price development.” The users thus become art (trade)/NFT experts (Ullrich 2022a, p. 12). |

| 43 | Far more pronounced forms of this gamification can be found on the U.S. platform Comic Vine (Comic Vine 2023), which describes itself as the “largest comic book wiki in the universe,” complete with forums, reviews, videos, podcasts, and much more. In addition to a comprehensive metrification system that ranks the most popular and most active contributors, one can acquire so-called “wiki points” and thus move up in the ranking (https://comicvine.gamespot.com, accessed on 8 February 2023). Non-digital versions of such practices can be found in comics as early as the mid-1960s. There, Marvel fans were ranked by the number of letters to the editor they sent to the publisher. |

| 44 | VeVe marks such an NFT comic with the respective era of its creation (Golden Age, Bronze Age, Silver Age, Modern Age). |