1. Theorizing and Historicizing the High/Low Difference

Popular culture is a relational term that denotes the other side of the high culture coin (Hügel 2003, p. 9). The presumed difference between high culture and popular culture speaks to an element of modern society that could be understood as a unity as late as the 19th century: culture. One had culture or one did not. Culture designated difference from barbarism (Luhmann 1995; Werber 1995) or signified difference from nature, positioning ‘cultured peoples’ or ‘cultured nations’ in contrast to ‘primitive peoples,’ to the ‘primitives’ (Schüttpelz 2005, pp. 18–19) or to the ‘savages’ (Schiller 1962, 4th letter).1

In the 19th century, it was apparently no longer sufficient (in Western Europe) to distinguish one’s own society as a culture from the state of nature or the less civilized (‘barbaric’) neighbors; it was also deemed necessary to distinguish internally more cultured from less cultured classes or regions. This internal differentiation was aimed at stratification: what was suitable for cultural distinction was decided by the upper classes and served as a “code” in dealing with the “classes beneath” for status reproduction (Veblen [1899] 2007, p. 39). Advanced civilizations of antiquity were regarded as civilizations with a ‘high level of human development’, distinguished from ‘primitive’ peoples with a ‘low level of edification’. Similar distinctions were now made in the same society. Educated upper classes were distinguished from less cultivated classes, much as an advanced civilization was distinguished from its uncivilized neighboring peoples. And just as these neighbors could be cultivated by learning Greek or Latin, writing and poetry, so could the ‘common’ people of a country attain these skills through upbringing, education, and enlightenment.

Popular culture in the sense of a widespread culture of the ‘common’ people was asymmetrically opposed to the high culture of the educated elites. This relationship is often modeled as a complexity gradient, but it need not be fundamentally deficient, for if high culture is considered ‘decadent’, for example, then popular culture can be declared a resource of ‘authentic’, ‘healthy’ renewal. In all of these cases, however, high culture is considered more refined, erudite, enlightened, and developed, while popular culture is considered to be simpler, meaner, plain, and backward. This qualitative meaning of the term ‘popular culture’ still plays a role nowadays, when superhero comics and pop music, Hollywood films and TV thrillers, and pulp fiction and videogames are quite naturally assigned to the realm of popular culture and thus excluded from high culture. This Special Issue interrogates this qualitative distinction through a multidisciplinary set of articles that reassess the significance of the high/low difference.

In the everyday self-descriptions of society, as seen in the mass media, high culture includes works that can be appreciated in art museums, are performed by philharmonic orchestras, presented in theaters and operas, memorized in schools, and interpreted in institutions of higher education. If popular culture is said to include productions that are quickly consumed and quickly forgotten, high culture is framed as being demanding. Participating in high culture is supposed to be challenging. You have to rise up to the task, and not everyone can.

Popular culture, according to common opinion, is undemanding, open to everyone. If high culture is elitist, popular culture is not—or so many people think. To play a piano sonata requires years of training, as high culture must be cultivated. To produce a hit for the radio or Spotify, one may not need music schools and master classes, but without an appealing sound, an infectious style, and catchy hooks, chances for success are low, which means that these things need to be cultivated, too, though perhaps in a different fashion. Nevertheless, popular culture is frequently viewed as self-evident, whereas high culture requires education.

Much has been written about the social function of this distinction between high culture and popular culture since Thorstein Veblen (Veblen [1899] 2007) and Pierre Bourdieu (Bourdieu [1979] 1987). One prominent example is Lawrence W. Levine’s Highbrow/Lowbrow: The Emergence of Cultural Hierarchy in America (Levine 1988), which locates the emergence of the hierarchized difference of high and low in the United States in the second half of the 19th century.2 Yet what matters most to us here is to recall the historical tradition of the term popular culture and its function as a counter-concept. For the US-American author and cultural critic Leslie Fiedler, the asymmetry of the distinction between high culture and low culture still characterized the production of art and the communication of values to such an extent at the tail end of the 1960s that he called for the difference to be overcome: “cross the border, close the gap”! (Fiedler 1969). This discourse, which is invested in the social power of judgment and always produces new distinctions, is still stratified (de Certeau [1980] 1988): high, middle, low culture, highbrow, midbrow, lowbrow, etc. We can only speak meaningfully of “midcult” in contradiction to “high culture” (Baßler 2022).

Umberto Eco has rightly remarked about the stratification of “democratic culture” (“high, middle, low”) that these “levels do not correspond to class stratification”: “As is well known, highbrow taste is not necessarily the taste of the ruling classes” (Eco [1964] 1986b, p. 52). Even if popular culture research of U.S. provenance tends to interpret popular culture as particularly democratic and as a more or less authentic expression of the lower and middle classes in contrast to the tastes of the elites,3 it is worth noting once again that modern or, as Eco writes, “democratic” society is no longer structured by ancestry but is culturally stratified: with the “fine distinctions” (Bourdieu [1979] 1987) of social judgment (simple, good, exquisite taste), ‘gross distinctions’ (stratification, ‘classes’) are reproduced and made plausible. Although, according to a bon mot by Andy Warhol, no millionaire can drink a better Coca-Cola or eat a better McDonald’s burger than anyone else, ‘cultural capital’ is still distributed very unequally, and owning a work from Warhol’s ‘Coca-Cola Bottles’ series promises a different form of attention and recognition than ordering a meal at McDonald’s. Pop Art remains ‘high’, fast food remains ‘low’ (Eco [1964] 1986a, p. 103). Despite all the brilliantly presented objections to the “pigeonholing” of social classes and cultural levels (Maase 2019, p. 177), we can still observe the coupling of social and cultural stratification (Werber 2021). For the German sociologist Andreas Reckwitz, our society is a “cultural class society” (Reckwitz 2017, p. 276), even if the “clear separation between the popular and the high-cultural subfield” since the 1990s “no longer seems to apply in that way” (p. 170).

In fact, we may say that, at least since the late 20th century, artifacts, genres, persons, or institutions that are attributed to popular culture are not meant to be disqualified because the reason for this designation rather lies in their quantitative distribution. The fact that something is considered popular culture can now have the simple reason that it is not only familiar to a few (like the hymns of Friedrich Hölderlin or the sonatas of Paul Hindemith) but is well known to many, like the songs of the Beatles, the James Bond films, or Umberto Eco’s The Name of the Rose. What is interesting about this assignment is that it no longer implies that the Beatles, the James Bond films, or Eco’s novels must be plain, low-level, and trivial. Being popular is no longer associated per se with disqualification. On the contrary, the outstanding number of Beatles top hits, the blockbuster characteristics of the James Bond films, and the best-selling quality of Eco’s The Name of the Rose can turn into a sui generis judgment of quality: what so many people like to hear, see, or read voluntarily (without being requested to do so in schools or universities, churches, or cultural institutions) seems to deserve this attention. What is popular in a quantitative sense claims a notability for itself; its legitimacy derives from quantity—that is, a quality that could once serve as a reason for devaluing popular culture, since what appealed to the masses had to be unprofessional.4

“Being popular means getting noticed by many” (Hecken 2006, p. 85). This quantitative dimension of the term ‘popular’ is already well documented in the historical semantics of the 18th century in English and French, Italian, and German, where the many—that is, the populus—is distinct from the nobility or clergy. References to ‘popular’ aim at ‘the great mob’, at ‘numerous people’, at the ‘masses’. ‘Popular’ thus implies not only ease of comprehension or vulgarity, accessibility, or meanness, but also a quantitative dimension, which at first also has mostly negative connotations (what is addressed to many people must for that reason alone be trivial, and what many people like cannot be sophisticated), but may have lost these pejorative connotations ‘around 1800’ (Penke, forthcoming).

‘Popular’ was also used in 19th- and 20th-century practice to index wide circulation and notoriety—and what is noticed by many seems interesting. That a book finds itself at the top of the bestseller list does not necessarily have to indicate its poor quality and undeservedness of attention. “It is important to understand”, the author and critic Dwight Macdonald stressed in 1960, “that the difference […] between High Culture and Masscult, is not mere popularity. […] [S]ome very good things have been popular: The Education of Henry Adams as the top non fiction best seller of 1919” (Macdonald 2011, p. 7).

A bestseller does not have to be trivial; a book’s wide circulation can suggest qualities that make it attractive to many. Today, ‘popular’ also means to be liked by many. It means not only that ‘a good thing can be popular’, as Macdonald conceded, but that it is a good thing to be popular. The quantitative dimension of attention takes on an evaluative note, as if the fact that many know something is also already evidence of that thing’s popularity. This assessment must now no longer be due to the common ‘rabble’ or the uneducated ‘masses’, which help precisely the meanest and simplest things to become widespread and popular—but, conversely, to the popular thing, which obviously attracts notice by many, from whatever social background and of whatever education. The conceptual history of the popular is complex and multi-layered, and it is worthwhile—this is one of the basic ideas of this Special Issue—to at least distinguish the quantitative and qualitative dimensions of semantics and to observe their complex entanglements.

What changed fundamentally over the course of the 20th century was the way in which “what is noticed by many” was determined. In the 18th or 19th centuries, what is or should be popular in the quantitative sense, because it addresses the many, the rabble, the populus, the common people, or the ordinary people in a simple, plain, accessible, or also provocative, entertaining, exciting form, was usually simply assumed. In the 20th century, a cultural technique emerged that has already been tested by state and corporate administrations and that measures and counts what has received no, little, much, or even gigantic attention. We know this from popular bestseller lists, charts, ratings, opinion polls, top 10, 20, or 100 rankings, and so on. The amount of attention something has attracted is registered, totalized, compared, and ranked. These rankings, unlike internal company balance sheets, are published and themselves attract a great deal of attention from the public. For the literary and cultural studies scholar Thomas Hecken, this cultural technique is characteristic of popular culture:

“Being popular means getting noticed by many. Popular culture is characterized by the fact that it constantly determines this. In charts, through opinion polls and elections, it is determined what is popular and what is not”.(Hecken 2006, p. 85; see also Hecken 2010)

Thus, bestseller lists or opinion polls do not document the popularity of every song, movie, book, product, person, program, tweet, or university. Charts usually show only the first 10, 20, or 100 places in a ranking—the many other artifacts or performers, works, or actors are not listed as they are not popular enough to be considered by the list, poll, or charts. It is the No. 1 that counts, and looking at the other places, it is interesting to see what or who may challenge the first-place position, especially since you yourself can play a part in this procedure: by buying the product or by getting others excited about it, such as by writing letters to the editor, founding and joining fan clubs, being active on fan forums, and so on (Stein 2021; Werber and Stein 2023). Here, a new, sharp difference is established between high and highest popularity, on the one hand, and low or no attention, on the other.

From a scientific perspective, it goes without saying that a high chart position does not have to be synonymous with high quality; likewise, it does not follow from a high ranking that something is without merit. Nevertheless, the placement in charts, polls, and rankings makes a massive difference for the distribution of attention. What has received much attention will receive even more attention because of its prominent placement; what is not listed in the charts at all hardly has a chance to become noticed by many. If the social distribution of attention, which in Bourdieu’s sense (Bourdieu [1979] 1987) was still closely tied to Eco’s “levels of culture” (Eco [1964] 1986b) and allocated “legitimate cultural capital” primarily to the products and practices of “canonized high culture” (Maase 2019, p. 193), it occurs under the regime of opinion polls and attention measurement and the representation of their results in charts and rankings (Adelmann 2021), along with a new distinction between ‘head’ (very much attention for the top 10 or top 20) and the ‘long tail’ (hardly any attention for all that does not appear in the rankings at all) (Anderson 2008).

If established high culture can no longer afford to do without popularity, i.e., wanting to be noticed by many, then it must be measured in the charts against what is already enjoying high popularity without high cultural pretense. In the bestseller lists, works of the poeta laureatus appear alongside the publications of expert crime novelists. The hierarchy between high culture and popular culture, on the one hand, and the educated classes and the uneducated masses, on the other, which was stabilized in the 19th century by the distinction between high and low, loses plausibility when it is the charts and rankings that matter and not membership in the ‘legitimate’ canon. The ‘ranked society’ becomes a ‘society of rankings’ (Esposito and Starck 2019, p. 1). Who and what counts is not to be taken from the registers and tastes of the upper classes, but from the charts and lists of popular culture: “In a society and in a world that do not have an indisputable and permanent order, knowing who one is and how and where one stands is perplexing. Ratings and rankings are tools to get an orientation in such a world—at a general and at a personal level” (Esposito and Starck 2019, p. 17).

In short, it is the charts that show what is popular, and occupying leading positions in the rankings is of paramount importance for the connectability of communication. It may have been enough in the 19th and early 20th centuries to point to the traditional rank of artifacts and persons (e.g., in schools and churches, in parliament, in universities, or in clubs) to make them likely to be noticed (‘read Goethe!’, ‘listen to Bach!’). Today, however, it is far less likely for persons or artifacts that play no role in charts and rankings to achieve much notice. Since some rankings list ‘sophisticated’ works alongside ‘entertaining’ products as long as they have reached a very large audience, one must ask: why should one read (listen to, watch) something just because it is considered a ‘classic’ instead of that which is demonstrably popular? Because the classics are better, of course, but according to what criteria? If they are not noticed, then there might be good reasons to avoid these works. The problem may not arise in some cases. Yet if, for example, it might once have been easy to recommend reading The Education of Henry Adams as a canonical text, it was also because it was a bestseller and a Pulitzer Prize-winning publication (the latter a kind of seal of approval for high culture) and was selected by the Modern Library editorial board as the best nonfictional work of the twentieth century a few decades after its initial publication. But today?

From these observations, an interesting situation arises for popular culture research that we want to make productive for this Special Issue: Alongside the established differentiation of high culture and popular culture on the basis of the high/low difference comes a distinction that can build on the measurement of attention and exhibit its results in charts and rankings. Highest attention is now no longer given to persons and artifacts of ‘legitimate culture’ (canon, classics, high culture), although this attention is still recommended or even demanded by many cultural institutions (schools, museums, theaters, operas, universities, etc.). The collaboratively written article that opens this Special Issue calls this phenomenon first-order popularization (Werber et al. 2023). From this perspective, products of low culture do not deserve attention. However, the most attention is, in fact, given to a large extent to those persons and artifacts that occupy the top positions in the ubiquitous charts and rankings and receive even more notice thanks to this placement. Bestsellers and top hits accumulate attention. Under the conditions of second-order popularization (popular things are measured and ranked, and these charts are in turn popularized), a new distribution of attention (with a head and long tail) emerges that finds its legitimacy not in the traditions and institutions of high culture, but in the evidence of great attention itself (Werber et al. 2023).

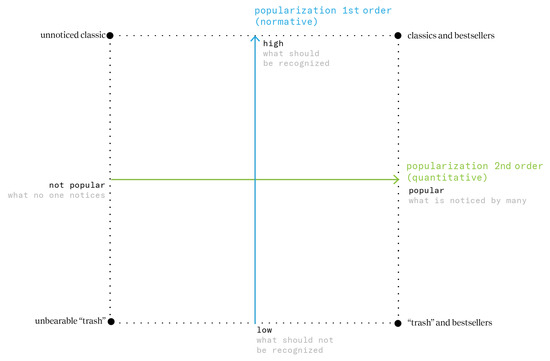

Graphically, these ‘two cultures’ can be visualized along two axes (Figure 1). The horizontal X-axis concerns the attention measured and recorded in rankings, ranging from the non-popular to the very popular. The vertical Y-axis distinguishes low culture and high culture. Both distinctions coexist. Canonical works may receive attention from few or from many—and it would be interesting to ask whether or not the lack or high popularity of a classic plays a role in society’s value communication. Artifacts that would have been assigned to low culture due to their mass distribution (trash) can claim their bestseller status due to high values on the X-axis (noticed by many) and thus find recognition—and thus also a longer shelf life, because trash is generally disposed of quickly, whereas what interests many tends to be preserved. Tensions between the two modes of popularization can be expected if persons and artifacts that should be noticed from the perspective of high culture are not, or vice versa, if persons and artifacts that should not attract attention do, in fact, appear on the charts.

Figure 1.

Matrix high/low—not popular/popular.

2. Doing Popularity/Dealing with Popularity

All of the articles in this Special Issue heed the prompt we offered in our initial call for papers, circulated in 2022. In this call, we noted that popular culture has long been identified either as the expression of the working class or the ‘common folk’, or as the lowly substratum of an idealized high culture, and that the emergence of a media-crossing pop aesthetic in the 1950s marked the beginning of a whole-scale social and cultural transformation. As an aesthetic of surfaces and artificiality, of the somatic, the serial, and mass-produced, and the “zany, cute, and interesting” (Ngai 2012), pop has amplified the ambivalence of the popular, such as its qualitative connotations of the simple and trivial or the resistant and subversive, as well as its quantitative claims of being better known, more commercially successful, and more widely disseminated than that which is not popular.

The quantitative and qualitative components of the popular inevitably intersect, our call suggested, if we assume that the simple and trivial can attract the attention of large audiences because it requires no effort on the part of the recipients. According to this approach, popular culture would always be ‘low’ culture. That this is not the case, as outlined above, becomes apparent when works of high culture enter the bestseller lists or when institutions of high culture seek popularity—when museums, opera houses, quality publishing houses, or theaters aim to attract the attention of many to justify their existence. The result of this process is the disruption of the established difference between low culture and high culture, as these institutions would not claim that their popular exhibitions, concerts, publications, or performances are trivial. With the popularization of the Internet around 2000 and with our current digital, algorithm-driven culture and its constant display of the metrics of popularity (likes, retweets, views; rankings, charts, hit-lists), the disruption of high/low distinctions has clearly intensified. In fact, pop’s popularity is putting pressure on the institutions of high culture, whose reactions range from accommodation and resilience to outright resistance (Döring et al. 2021; Werber et al. 2023).

These developments call for new approaches to the study of pop culture that acknowledge and account for the contrast between the established (and well-researched) high/low distinctions of the 19th and 20th centuries and, since the 1950s, the ever-increasing importance of charts, polls, rankings, and bestseller lists for the social distribution of legitimate attention. What becomes of the difference between high culture and low culture when it is disrupted by what we label the “metrics of popularity” (Werber et al. 2023, p. 4)?

Addressing this question, all of the articles assembled in this Special Issue connect elements of dealing with popularity with aspects of doing popularity. Assuming the high popularity of certain narratives, artifacts, or activities and ascertaining what effects this popularity may have on their evaluation constitutes the first perspective: dealing with popularity. The choice of topics can follow the traditional classification of popular culture (on the basis of the high/low distinction) but will then pose the question of how taste judgments and classifications are reformed when high attention can be legitimized in the field. The second perspective explores how a field or genre may reshape itself under conditions of second-order popularization through a process of doing popularity. Here, the thesis would be that a field or genre changes in its formation and development when first-order popularization loses weight and second-order popularity becomes a motivational and legitimizing resource in its own right.

This Special Issue begins with the translated and significantly revised version of an article originally published in Kulturwissenschaftliche Zeitschrift (Döring et al. 2021), authored collectively by Niels Werber, Daniel Stein, Jörg Döring, Veronika Albrecht-Birkner, Carolin Gerlitz, Thomas Hecken, Johannes Paßmann, Jörgen Schäfer, Cornelius Schubert, and Jochen Venus, and retitled “Getting Noticed by Many: On the Transformations of the Popular” here. The article lays out the research objectives as well as the theoretical and conceptual foundations of the Collaborative Research Center (CRC) 1472 Transformations of the Popular, funded by the German Research Foundation (2021–2024) and hosted at the University of Siegen, and it also prepares the ground for the articles collected in this Issue. Formulating the major premises of the CRC—“being popular now means getting noticed by many. Popularity is measured as well as staged, as rankings and charts provide information on what is popular while vying for popularity themselves”; “The popular modifies whatever it affords with attention” (Werber et al. 2023, p. 1)—the article outlines a theory of the popular that identifies two decisive historical transformations:

“1. the popularization of quantifying methods to measure attention in popular culture around 1950; 2. the popularization of the internet around 2000, whereby the question of what can and cannot become popular is partially removed from the gatekeepers of the established mass media, educational institutions, and cultural elites and is increasingly decided via social media”.(Werber et al. 2023, p. 1)

Moreover, the authors propose that “[t]he high/low distinction alone is not essential for understanding the transformations of the popular; rather, it is the scalable difference between what remains unnoticed and what is popular” (p. 3). This difference depends on “quantifying formats [that] compete with a wide range of qualitative judgments”. To “[a]chiev[e] success across the metrics of popularity” and to “becom[e] more popular and noticed on a greater scale”, the authors maintain further, “challenges the semantic and socio-structural difference between high and low culture” (p. 4). Today, they suggest, “high culture can no longer stand outside its relation to the popular”, which is why we must ascertain “whether and how the longstanding contrast between high and low culture will be replaced with the distinction between the popular and the non-popular” (p. 5). This involves dealing with popularity as much as it entails doing popularity.

Niels Werber and Daniel Stein’s “Paratextual Negotiations: Fan Forums as Digital Epitexts of Popular Superhero Comic Books and Science Fiction Pulp Novel Series”, our own contribution to the Special Issue, puts many of the conceptual premises and analytical parameters outlined in the initial article to the test. It turns to two immensely popular and long-running examples of serial storytelling—the German pulp novel series Perry Rhodan (since 1961) and Captain America superhero comics (since 1941)—to examine how “the quantitative-empirical metrics of attention measurement and their public display” (Werber and Stein 2023, p. 1) affect both the material we study and the methodology through which we study it. The article focuses on digital paratexts, specifically fan forums in the tradition of printed letter columns and editorials, as a space that fosters a series’ popularity by motivating its ongoing reception (doing popularity) and that shapes its public perception by facilitating legitimization as a popular narrative, genre, or medium (dealing with popularity). We develop our analytical method by “studying the evolution of popular genre narratives through the detour of digitally analyzing forum communication, which we understand as a particular form of paratextual discourse” (p. 4) that constitutes a “participatory element of popular culture […] in the interplay between series text and serial paratext and [that] can be described as a force in serial evolution that thrives on a combination of variation and redundancy and of selection and adaptation” (p. 1).

Mirja Beck’s “A Lived Experience—Immersive Multi-Sensorial Art Exhibitions as a New Kind of (Not That) ‘Cheap Images’” is also interested in forms of popular reception. Yet rather than focusing on genres and formats that were initially relegated to the realm of the low (like the science fiction pulp novels and superhero comics in the preceding article), Beck investigates the intriguing history of popularizing art beyond the realms of high culture. Her analysis centers on “the phenomenon of multi-sensorial, digital, and immersive art exhibitions of popular artists” (such as Van Gogh Alive or Van Gogh: The Immersive Experience) and examines their connection to early-20th-century photomechanical art reproductions (Beck 2023, p. 1). Beck traces reactions to these exhibitions ranging from “resistance” to the cheap and popular to “accommodation” and pinpoints “noticeable similarities between the two types of popularization of high art, positioning the new immersive exhibitions in a traditional line of technical innovative art popularization” (p. 1). In each case, the artworks and artists popularized with the help of new technologies (photomechanical reproduction; digital projection) tend to be those who are already popular, suggesting that “[p]opularity guarantees success” (p. 9). While these immersive exhibitions are obviously dealing with popularity by pondering the potential effects of their popularity on their evaluation—they attract large audiences but teach little art history; their popularity inhibits scholarly engagement—it remains unclear whether they may also be doing popularity. If art reproduction, including immersive exhibitions, “plays a major role in canonization” (p. 9), it seems that the field of art is not so much reshaping itself under conditions of second-order popularization but is rather using this type of popularization to maintain a status quo where Van Gogh can continue to be appreciated as a high artist as well as a highly popular figure.

Daniel Stein, Laura Désirée Haas, and Anne Deckbar’s “Of Auction Records and Non-Fungible Tokens: On the New Valences of Superhero Comics” also touches on the significance of high art discourses, but it uses these discourses as a foil against which new digital forms of popular validation of an already popular genre can be gauged. The article analyzes “the convergence of two widely publicized phenomena: the massive increase in value of old superhero comics, which serves as the prerequisite for new forms of digital value creation, and non-fungible tokens (NFTs), which popularize superheroes in a highly volatile digital marketplace” (Stein et al. 2023, p. 1). More specifically, it connects the spectacularized sales of well-preserved comic books, such as rare copies of Action Comics #1 (1938) or Fantastic Four #1 (1961), with Marvel’s attempts to promote their intellectual properties by selling selected items as NFTs through a collaboration with the VeVe app, artificially creating scarcity in order to highlight the continuing value of comic books in the digital age. The article traces a “transformation from a popular but devalued (‘low’) product to a popular and culturally valued (but not necessarily ‘high’ cultural) artifact” and identifies “a shift from qualitative to quantitative valuation that was driven at least in part by popular practices of collecting, archiving, and auctioning that have enabled the ongoing adaptation of these comics to new social, technological, and media demands” (p. 1). Doing popularity and dealing with popularity go hand in hand, in this case. The popularity of superhero comics—measured in terms of their ability to produce “key” issues of tremendous monetary value, the longevity of their serial existence (more than 80 years and counting), and their continuing capability to attract much notice from many (e.g., newspaper headlines about bestselling issues, public celebrations of iconic characters, transmedia adaptions across the globe)—certainly affects their evaluation as it shifts from depreciation (‘low’) to appreciation (‘popular’) and establishes them as an important element of U.S. (popular) culture. In terms of doing popularity, it is the conspicuous display of their popularity—the headlines about sales prices and NFT values, the visible metrics on the VeVe app—that indicate how superhero comics evolve under the conditions of second-order popularization.

If the first three articles of this Special Issue approach pop culture through literary, cultural, and art historical lenses, Bernd Dollinger and Julia Rieger’s “Crime as Pop: Gangsta Rap as Popular Staging of Norm Violations” takes the vantage point of educational science. Here, it is not so much the aesthetic properties of gangsta rap—the musical genre at the center of analysis—or its reception by fans or industry professionals that counts, but rather the ways in which young people in open youth work facilities relate to gangsta rap as a “pop-cultural phenomenon” and utilize it in “interactive practices of identity construction” (Dollinger and Rieger 2023, p. 1), examining practices of doing popularity in the process. Dollinger and Rieger take an ethnographic approach as they study “the reception and appropriation of gangsta rap [by] taking a look at how young people connect to motifs of the genre and integrate them into their own narratives and practices” (p. 1). They demonstrate that crime is not only measured extensively as an element of ‘low’ culture (e.g., in crime statistics), but that it is also “an ambivalent, often attractive and at the same time risky, event, in whose representation recipients are constitutively involved” (p. 1). Noting that “‘Crime as Pop’ […] hinges on attention” and that “gangsta rap also thrives on the attention and appreciation it receives” (pp. 3–4), the authors trace—through ethnographic observation and group discussions—how young people incorporate the heroization and spectacularization of gangsta rappers and the “norm violations” these performers promote into their everyday lives and make them part of their interactions with peers through a process of “narrative appropriation” (p. 6). By arguing that “‘Crime as Pop’ challenges the purely negative evaluation of crime as ‘low culture’ and focuses on crime as a phenomenon that receives attention because it is attractive to recipients” (p. 10), the authors counter another widely popular notion of crime as the cause for moral panics, underscoring possibilities of dealing with popularity.

Theresa Nink and Florian Heesch’s “Metal Ballads as Low Pop? An Approach to Sentimentality and Gendered Performances in Popular Hard Rock and Metal Songs” moves us into yet another disciplinary territory. As a musicological investigation of a conventionally devalued and feminized yet paradoxically immensely popular musical genre (a representative of “low pop”, in Nink and Heesch’s nomenclature), the sentimental ballad as performed by hard rock and heavy metal bands, the article analyzes “the sonic, textual, performative, visual, and emotional-somatic articulation of love and the generation of sentimentality in three selected metal ballads” (Aerosmith’s “Don’t Want To Miss A Thing” (1998), Extreme’s “More Than Words” (1991), Evanescence’s “My Immortal” (2003)) (Nink and Heesch 2023, p. 1). Nink and Heesch argue that sentimental ballads recorded and performed by bands from “stereotypically more masculine-connotated genres […] create friction and skepticism in their discursive evaluation, as they generate aesthetic discrepancies between concrete songs and genre conventions”. Here, “quantitative popularity contrasts with […] qualitative evaluation”, feeding on a hierarchy according to which “low pop is popular in a quantitative sense but would be considered low in a qualitative sense” (p. 11)—an “axiological devaluation” (p. 12) that opens up spaces for gendered performances beyond conventional “metal masculinities” (p. 11). While the article concentrates on processes of dealing with popularity (how the popularity of metal ballads affects their reception), it does consider aspects of doing popularity as well, for instance, by using as its corpus the commercially successful German Kuschelrock ballad compilations, which indicate the permeability of genre boundaries and show that there is indeed a market for, and perhaps an expectation of, metal bands going sentimental.

Angela Schwarz and Milan Weber’s “New Perspectives on Old Pasts? Diversity in Popular Digital Games with Historical Settings” investigates representations of diversity in digital games set in various pasts. The article adds a historian’s perspective on popular culture to this Special Issue, considering both new developments in game culture and new ways of popularizing history and thus exemplifying what we call doing popularity: “digital games have come to stage notions of history and the past for ever broader circles of recipients, thereby shaping what is understood, interpreted, and negotiated as history in popular contexts”, Schwarz and Weber observe: “Digital games with historical settings not only adopt already successfully popularized and widely mediated images of history. They also integrate current social debates into the historical worlds they construct and recreate” (Schwarz and Weber 2023, p. 1), the debate about questions of racial, ethnic, and cultural representation and the expectation to become more inclusive and diverse being rather prominent and urgent. Analyzing three games—Red Dead Redemption II (2018), the content addition to Assassin’s Creed IV: Black Flag titled Freedom Cry (2013), and Kingdom Come: Deliverance (2018)—the article identifies long-standing, frequently pernicious, but arguably popular stereotypes about historical periods and actors, as well as what the authors call “a contemporary, normatively charged discourse that is far from a consensus, which impinges upon popular notions of the past and thereby transforms and diversifies these very images without completely dissolving them” (p. 17). Schwarz and Weber show that Red Dead Redemption II (set in the Wild West of the second half of the 19th century) and Assassin’s Creed: Freedom Cry (set among Caribbean slaveholding societies in the 18th century) manage to complicate popular iterations of their respective historical periods by creating complex settings and diverse—and thus historically rather accurate—casts of characters, whereas the game world of Kingdom Come: Deliverance (2018), the European Middle Ages of the early 15th century, “confirms Eurocentric and colonialist ideas about non-European societies” and avoids “any reflection on debates about Europe’s colonial heritage” (p. 15). By noting that gaming culture is no longer predominantly white and that presenting greater historical diversity is no longer detrimental to commercial success, Schwarz and Weber indicate how some of these games are doing popularity and promoting diversity at the same time.

Grace D. Gipson’s “Now It’s My Time! Black Girls Finding Space and Place in Comic Books” ponders “how Black girl narratives are finding and making space and place in the arena of comic books and television” (Gipson 2023, p. 1). It asks how these narratives depend on the parameters of popularity: getting noticed by many, as indicated by comic book sales and the size of television and film audiences, as well as on their broader (popular) cultural acclaim, such as the appearance of one young superheroine in a student-made live-action video short for the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) Admissions department. Conceiving of the “possibilities of popular media culture” (p. 1) as a mixture of progressive intent, made manifest in the desire to increase the visibility and complexity of Black girl characters in comic books and beyond, and the commercial need to attract and maintain audiences in order to generate revenue, Gipson turns to three more or less popular Black girl characters (Marvel Comics’ RiRi Williams/Ironheart, DC Comics’ Naomi McDuffie, and Boom! Studios’ Eve) and tracks their creation and reception in terms of how they represent the experience of Black girlhood, how their creators approach racial representation, and how racialized identities are increasingly part of a larger effort to provide a more nuanced (and more intersectional) roster of superheroes and superheroines. While these efforts are commercially motivated and those characters and storylines allow Marvel to “move toward broadening their audience (tapping into the pre-teens and adolescent fanbase) and creating more diverse characters” (p. 4), they might bring about the “necessary change to the landscape of popular media culture” (p. 1) in a process of doing popularity.

This popular media culture is also at the center of Julia Leyda and Maria Sulimma’s “Pop/Poetry: Dickinson as Remix”, which looks at serial television in the age of streaming platforms and an emerging pop aesthetic called “cottagecore”, defined as “a meme aesthetic of spectacularized selfcare and self-soothing widespread in pandemic popular culture” (Leyda and Sulimma 2023, p. 9). The article adds an important perspective to the Special Issue because of its double interest in what we can understand, in the terminology of the CRC, as the first-order popularization of 19th-century poetry, especially the poet Emily Dickinson and her works, beyond the traditional realm of high culture, and in the remix approach the series takes to its subject, which draws on internet culture from memes to social media tropes (p. 4). As Leyda and Sulimma suggest, the article “explore[s] some of the narrative and aesthetic strategies the series employs through its remixing of Emily Dickinson’s life, poetry, and milieu with the archives of contemporary Internet culture and popular culture” (p. 4). Arguing that “[t]his remixing thrives on dissonance and anachronism” (p. 4), the authors conclude that “contemporary television may exceed distinctions between ‘highbrow’ and ‘lowbrow’ cultural productions—as well as previous valorizations of specific television shows as ‘quality TV’—through a particular remix aesthetic form” (p. 12) that, as critic Laura Bradley notes about Dickinson, “appears to know exactly how Twitter will respond” (qtd. in Leyda and Sulimma 2023, p. 6). Leyda and Sulimma demonstrate how a show like Dickinson is doing and dealing with popularity by using first-order popularization to paint a new portrait of a canonical US-American female poet and tapping into the powers of second-order popularization through Apple TV’s metrics and algorithms as well as the attention dynamics of Twitter and social media. As such, the series can “bring[] into conversation shifting boundaries of high and low culture across generations and engage with critical debates about the utility of the popular (and of studies of the popular) in literary and cultural studies in particular” (p. 1).

Two articles on popular music conclude this Special Issue. Ilias Ben Mna’s “This Country Ain’t Low—The Country Music of Dolly Parton and Johnny Cash as a Form of Redistributive Politics” adds a suggestive twist by revealing “how the country music styles of Dolly Parton and Johnny Cash serve as a form of redistributive politics in which ideological struggles are engaged in ways that dissolve low/high culture distinctions and instead offer a mass-accessible avenue through which cultural recognition is conferred to marginalized identities” (Ben Mna 2023, p. 1). While country music as a musical genre is certainly popular, with Parton and Cash being among its most successfully and also most iconic figures, it is often associated in the broader public with a reactionary politics that is complicated by Parton’s and Cash’s “progressive populism” (a term Ben Mna cites from Nancy Fraser on p. 4). Ben Mna usefully refers to Markus Heuger’s emphasis on popularity’s “quantitative aspects” and his understanding of “popularity as high degree of dissemination measurable for example in air play statistics or sales figures” (Heuger 1997, np) but also acknowledges the effects of popularity publicly displayed. As Heuger puts it: “It is often believed that record charts as published weekly since 1949 in the U.S. music magazine Billboard, measure popularity. In reality charts have been developed as a complex instrument to organize sales effectively and not to represent cultural reality. Thus, they effect the popularity of artists and records rather than express it” (Heuger 1997, np). This is doing and dealing with popularity in a nutshell, and Ben Mna uses this conceptualization to argue that “questions of popularity also concern questions of mass readability and mass accessibility” (Ben Mna 2023, p. 9), concluding that “the progressive layers of Parton’s and Cash’s output and self-stylization broadened the scope of country audiences and showcased the genre’s wider potential as a form of counter-cultural discourse” (p. 12).

Jörg Scheller’s “Apopcalypse: The Popularity of Heavy Metal as Heir to Apocalyptic Artifacts”, described by the author as “a door-opener in the tradition of scholarly essayism (from Montaigne through Leslie Fiedler to Donna Haraway and beyond) and what philosopher Paul Feyerabend termed ‘theoretical anarchism’” (Scheller 2023, p. 2), coins the term “Apopcalypse” to suggest that the biblical Book of Revelation (the bible being the most popular book of all time) and classic heavy metal “as a modern heir to religious apocalyptic artifacts” are connected by “a specific appeal to the popular” (p. 1), a connection that is grounded in a powerful affective and aesthetic audience appeal and their function as media of “premonition or prophecy” (p. 1). In particular, the article considers the apparent paradox between heavy metal’s popular apocalyptic visions and the genre’s emergence and prominence “in relatively (!) pacified, wealthy, liberal western consumer societies” (p. 1). Asking “[i]n what sense is classic heavy metal popular […], in what sense is the biblical apocalypse popular […], and what social function might the metal-specific combination of popularity and apocalypticism have in the context of the postindustrial, relatively peaceful and relatively (!) prosperous Western societies in which metal emerged”, Scheller combines an interest in dealing with popularity (heavy metal’s popularization of apocalyptic imagery) and doing popularity (how aspects of the music and lyrics as a cultural phenomenon offer a version of what philosopher Günther Anders calls “aesthetic resilience training” (p. 1)). In light of the ongoing climate crisis, the rise of rightwing politics across the globe, and the denial of facts in our “post-truth” age, where AI and deepfakes are eroding trust in expert knowledge, it seems rather fitting that this Special Issue ends with an article on the apo(p)calypse.

While the topics addressed in the articles assembled in this Issue are certainly not exhaustive, we are convinced that the following pages offer highly valuable new perspectives on pop culture and, taken together, test, affirm, refine, and sometimes question the basic theoretical and conceptual parameters proposed by the CRC Transformations of the Popular. They are intended as discussion starters, as a concerted impulse to reassess the gap between high and low culture, to rethink conventional notions of pop and the popular, and to acknowledge popularity’s increasing significance as a scalable force in contemporary society.

All of the articles underwent a process of double-blind (and sometimes triple-blind) peer review and benefited tremendously from the constructive responses of the reviewers, whom we wish to thank for their investment in this Special Issue and their support of the research collected here.

Funding

This publication is part of the research of the Collaborative Research Center 1472 “Transformations of the Popular”, funded by the German Research Foundation (Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft; Project ID 438577023—SFB 1472).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Notes

| 1 | We translated all originally German quotations into English. |

| 2 | Levine criticizes what he perceives as the arbitrariness of this basic but powerful categorization when he speaks of “the imprecise hierarchical categories culture has been carved into” and then asks: “How did one distinguish between ‘low’, ‘high’, ‘popular’, and ‘mass’ culture? What were the definitions and demarcation points? The arresting films of Frank Capra, one of the 1930s’ best known and most thoughtful directors, were labeled ‘popular culture’ as was the art of Norman Rockwell, the decade’s most popular and accessible American painter. But the same label was also applied to a grade ‘B’ movie produced with neither much thought or talent, or a Broadway musical comedy that closed after opening night. Why were all of these quite distinct expressions lumped together? What did they have in common? (It certainly was not ‘popularity’!)” (Levine 1988, pp. 6–7). |

| 3 | This is the case in Jim Cullen’s The Art of Democracy: A Concise History of Popular Culture in the United States (Cullen 1996). In the preface to the second edition of the essay collection Popular Culture in American History, Cullen argued with a view to the emergence of popular culture studies in the late 1960s and 1970s: “there was widespread consensus about a real and sometimes deep gulf between what was considered to be the culture of the working and middle classes […] and what was considered to be that of the elite. It was the difference between blues and opera; between slapstick comedy and foreign-language drama; between mystery novels and literary fiction”. Yet Cullen also acknowledged: “In the twenty-first century that sense of a division is a lot less sharp than it used to be” (Cullen [2001] 2013, p. xii). |

| 4 | Writing in the early 1950s, Dwight Macdonald presents the following examples of what he calls “mass culture”: “in the novel, the line stretches from Eugène Süe [sic] to Lloyd C. Douglas; in music, from Offenbach to tin-pan alley; in art, from the chromo to Maxfield Parrish and Norman Rockwell; in architecture, from Victorian Gothic to suburban Tudor. Mass Culture has also developed new media of its own, into which the serious artist rarely ventures: radio, the movies, comic books, detective stories, science-fiction, television” (Macdonald 1953, p. 1). |

References

- Adelmann, Ralf. 2021. Listen und Rankings: Über Taxonomien des Populären. Bielefeld: Transcript. [Google Scholar]

- Anderson, Chris. 2008. The Long Tail. New York: Hyperion eBooks. [Google Scholar]

- Baßler, Moritz. 2022. Populärer Realismus: Vom International Style des gegenwärtigen Erzählens. Munich: Beck. [Google Scholar]

- Beck, Mirja. 2023. A Lived Experience—Immersive Multi-Sensorial Art Exhibitions as a New Kind of (Not That) ‘Cheap Images’. Arts 12: 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ben Mna, Ilias. 2023. This Country Ain’t Low—The Country Music of Dolly Parton and Johnny Cash as a Form of Redistributive Politics. Arts 12: 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bourdieu, Pierre. 1987. Die feinen Unterschiede: Kritik der gesellschaftlichen Urteilskraft. Frankfurt am Main: Suhrkamp. First published 1979. [Google Scholar]

- Cullen, Jim. 1996. The Art of Democracy: A Concise History of Popular Culture in the United States. New York: Monthly Review Press. [Google Scholar]

- Cullen, Jim, ed. 2013. Popular Culture in American History, 2nd ed. Chichester: Wiley-Blackwell. First published 2001. [Google Scholar]

- de Certeau, Michel. 1988. Die Kunst des Handels. Berlin: Merve. First published 1980. [Google Scholar]

- Dollinger, Bernd, and Julia Rieger. 2023. Crime as Pop: Gangsta Rap as Popular Staging of Norm Violations. Arts 12: 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Döring, Jörg, Niels Werber, Veronika Albrecht-Birkner, Carolin Gerlitz, Thomas Hecken, Johannes Paßmann, Jörgen Schäfer, Cornelius Schubert, Daniel Stein, and Jochen Venus. 2021. Was bei vielen Beachtung findet: Zu den Transformationen des Populären. Kulturwissenschaftliche Zeitschrift 6: 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eco, Umberto. 1986a. Die Struktur des schlechten Geschmacks. In Apokalyptiker und Integrierte: Zur kritischen Kritik der Massenkultur. Frankfurt am Main: Fischer, pp. 59–115. First published 1964. [Google Scholar]

- Eco, Umberto. 1986b. Massenkultur und ‘Kultur-Niveaus’. In Apokalyptiker und Integrierte: Zur kritischen Kritik der Massenkultur. Frankfurt am Main: Fischer, pp. 37–58. First published 1964. [Google Scholar]

- Esposito, Elena, and David Starck. 2019. What’s Observed in a Rating? Rankings as Orientation in the Face of Uncertainty. Theory, Culture & Society 36: 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fiedler, Leslie A. 1969. Cross the border, close the gap. Playboy: The Men’s Entertainment Magazine 16: 12, 151, 230, 252–58. [Google Scholar]

- Gipson, Grace D. 2023. Now It’s My Time! Black Girls Finding Space and Place in Comic Books. Arts 12: 66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hecken, Thomas. 2006. Populäre Kultur: Mit einem Anhang ‘Girl und Popkultur’. Bochum: Posth. [Google Scholar]

- Hecken, Thomas. 2010. Populäre Kultur, populäre Literatur und Literaturwissenschaft: Theorie als Begriffspolitik. Journal of Literary Theory 4: 217–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heuger, Markus. 1997. Popularity. In Encyclopedia of the Popular Music of the World. Available online: http://www.markusheuger.de/theory/popularityepmow.pdf (accessed on 5 September 2023).

- Hügel, Otto, ed. 2003. Handbuch Populäre Kultur. Stuttgart: Metzler. [Google Scholar]

- Levine, Lawrence W. 1988. Highbrow/Lowbrow: The Emergence of Cultural Hierarchy in America. Cambridge: Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Leyda, Julia, and Maria Sulimma. 2023. Pop/Poetry: Dickinson as Remix. Arts 12: 62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luhmann, Niklas. 1995. Jenseits von Barbarei. In Gesellschaftsstruktur und Semantik. Frankfurt am Main: Suhrkamp, vol. 4, pp. 138–50. [Google Scholar]

- Maase, Kaspar. 2019. Populärkulturforschung: Eine Einführung. Bielefeld: Transcript. [Google Scholar]

- Macdonald, Dwight. 1953. A Theory of Mass Culture. Diogenes 1: 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macdonald, Dwight. 2011. Masscult and Midcult. In Masscult and Midcult: Essays Against the American Grain. Edited by John Summers. New York: New York Review of Books, pp. 7–71. [Google Scholar]

- Ngai, Sianne. 2012. Our Aesthetic Categories: Zany, Cute, Interesting. Cambridge: Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Nink, Theresa, and Florian Heesch. 2023. Metal Ballads as Low Pop? An Approach to Sentimentality and Gendered Performances in Popular Hard Rock and Metal Songs. Arts 12: 38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Penke, Niels. Forthcoming. Formationen des Populären. Heidelberg: Winter.

- Reckwitz, Andreas. 2017. Die Gesellschaft der Singularitäten: Zum Strukturwandel der Moderne. Berlin: Suhrkamp. [Google Scholar]

- Scheller, Jörg. 2023. Apopcalypse: The Popularity of Heavy Metal as Heir to Apocalyptic Artifacts. Arts 12: 120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schiller, Friedrich. 1962. Über die ästhetische Erziehung des Menschen in einer Reihe von Briefen. 1795. In Schillers Werke. Nationalausgabe. Philosophische Schriften erster Teil. Edited by Benno von Wiese. Stuttgart and Weimar: Böhlau, vol. 20, pp. 309–412. [Google Scholar]

- Schüttpelz, Erhard. 2005. Die Moderne im Spiegel des Primitiven. Weltliteratur und Ethnologie (1870–1960). München: Fink. [Google Scholar]

- Schwarz, Angela, and Milan Weber. 2023. New Perspectives on Old Pasts? Diversity in Popular Digital Games with Historical Settings. Arts 12: 69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stein, Daniel. 2021. Authorizing Superhero Comics: On the Evolution of a Popular Serial Genre. Columbus: Ohio State University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Stein, Daniel, Laura Désirée Haas, and Anne Deckbar. 2023. Of Auction Records and Non-Fungible Tokens: On the New Valences of Superhero Comics. Arts 12: 131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veblen, Thorstein. 2007. Theory of the Leisure Class. Oxford: Oxford University Press. First published 1899. [Google Scholar]

- Werber, Niels. 1995. Von Feinden und Barbaren: Carl Schmitt und Niklas Luhmann. Merkur: Deutsche Zeitschrift für europäisches Denken 9: 949–57. [Google Scholar]

- Werber, Niels. 2021. ‘Hohe’ und ‘populäre’ Literatur: Transformation und Disruption einer Unterscheidung. Jahrbuch der Deutschen Schillergesellschaft 65: 463–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Werber, Niels, and Daniel Stein. 2023. Paratextual Negotiations: Fan Forums as Digital Epitexts of Popular Superhero Comic Books and Science Fiction Pulp Novel Series. Arts 12: 77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Werber, Niels, Daniel Stein, Jörg Döring, Veronika Albrecht-Birkner, Carolin Gerlitz, Thomas Hecken, Johannes Paßmann, Jörgen Schäfer, Cornelius Schubert, and Jochen Venus. 2023. Getting Noticed by Many: On the Transformations of the Popular. Arts 12: 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).