Abstract

In response to the absence of a critical discussion of race within his historiography, this essay focuses on José Campeche (1751–1809) as an artist of African descent and argues that the socially and culturally inscribed constructs of race and Campeche’s lived experiences of them in late eighteenth-century Puerto Rico shaped and informed his participation in the arts. Campeche lived both as an artist and as a free man of color within a racialized colonial society, and as such, inquiries regarding how race affected Campeche’s life and artistic practice, and particularly how his immersion in the community of free people of color in San Juan possibly impacted the manner in which he was trained and worked, allow for a more comprehensive understanding of his art production. Using comparable examples of African descendant artists and artisans active in other colonial centers, such as Mexico City and Havana, this article elucidates connections between Campeche’s socioracial reality, his artistic career, and his work through an examination of the relationship between race and art making in Puerto Rico, the broader Caribbean region, and the greater Spanish Empire during the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries. This analysis of Campeche’s career and work prompts new questions about the artist that have not been asked in previous scholarship, such as how the structures of race would have defined his position and interactions within colonial society and also how his complex multiracial identity may have allowed him access to the different kinds of artistic exposure, training, and opportunities he likely had in San Juan.

Keywords:

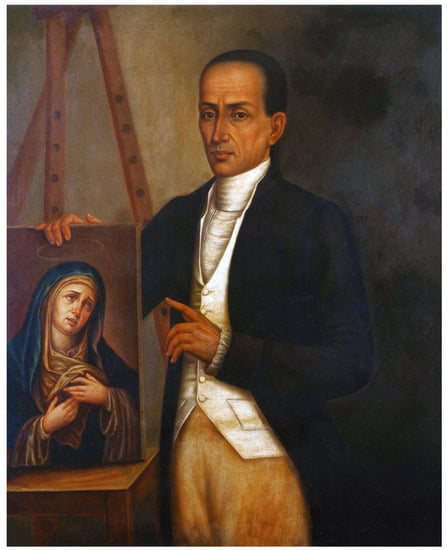

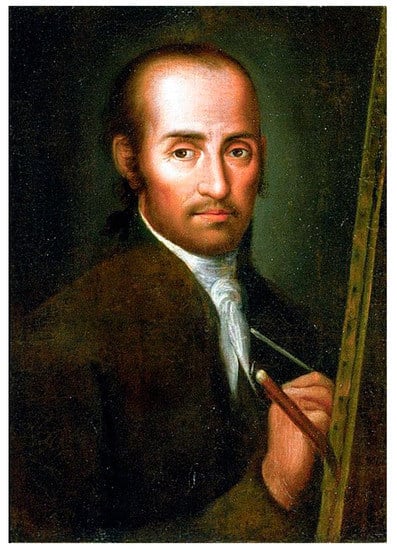

José Campeche; Puerto Rico; art history; Caribbean; race; eighteenth century; self-portraiture In 1855, two renowned Puerto Rican painters created their own versions of a now-lost self-portrait by José Campeche (1751–1809).1 Though both painters assumedly used the same work as their reference, the paintings appear quite dissimilar in their composition and style and highlight different aspects of Campeche’s artistic character. Ramón Atiles y Pérez (1804–1875) portrayed Campeche in a three-quarter view facing towards the picture plane and gazing steadily out at the viewer with an austere visage (Figure 1). In the work, Campeche supports a small painting of the Virgin of Sorrows with his right hand while gesturing to the image with his left. As the artist is positioned in front of an easel, the viewer understands that the work refers to Campeche’s accomplishments and skill as a painter and to the many religious works he created for residents and churches in Puerto Rico and across the greater Spanish Caribbean throughout his illustrious career. Conversely, Francisco Oller (1833–1917) painted his version of the portrait with a much softer compositional line.2 He omits the Virgin of Sorrows altogether and instead slightly reorients Campeche’s form towards a larger canvas which faces away from us. Campeche no longer makes eye contact with the viewer, but rather gazes contemplatively upon his own work-in-progress. Captured between brushstrokes, the artist’s right hand holds a paintbrush poised to make its next mark, and his left supports a palette and extra brushes. Oller’s portrait of Campeche, rather than presenting a finished work, showcases the act of creating a painting, demonstrating the artist’s knowledge of painting techniques as well as his originality and invention as a painter. Instead of specifically highlighting a single composition, he allows the viewer to imagine any of Campeche’s numerous religious or secular works as the subject of the painting over which he labors.

Figure 1.

Ramón Atiles y Pérez, Copia del Autorretrato de Campeche, mid-19th century. Oil on canvas. 39 1/2″ × 21 3/4″. New Jersey, Collection of Carmen Ana Casal de Unanue.

While these two portraits are distinct from one another, there is a marked and fascinating similarity between them that arguably belies a detail true to the original created by Campeche. Most significantly, both Atiles and Oller present the artist with a discernibly brown skin tone, visibly alluding to his mixed race. Campeche’s mother, María Josefa Jordán y Marqués, was a white immigrant from the Canary Islands, and his father, Tomás Rivafrecha y Campeche, was a formerly enslaved man of African descent.3 In his self-portrait, it can be assumed, Campeche chose to present himself as both a highly skilled, competent painter and a person of color in the late eighteenth-century colonial Spanish world.4 The reference to Campeche’s race within the work, however subtle, is notable, as such a representation of an African descended artist was rare in the Spanish Empire during the colonial era. In addition, this highly personal visual acknowledgement of Campeche’s racial heritage becomes even more compelling when we consider that he lived his life embedded within a racially diverse and hierarchical Spanish colonial society that generally discriminated against and disadvantaged non-white individuals, especially those of African descent. As Fray Íñigo Abbad y Lasierra stated in 1782 while writing about the societal treatment of free people of color in Puerto Rico, there was “nothing more ignominious than being a black or descended from them”.5 Campeche’s self-portrait, and further, the success and popularity he achieved as Puerto Rico’s “best painter and only physiognomist” during his lifetime, raises questions about the implications of his agency as a man of African descent within a racialized colonial society and what his race meant to his life and artistic practice in Puerto Rico at the end of the eighteenth century.6

Such questions regarding Campeche’s race and how it may have affected his lived experience and career have yet to be comprehensively examined in the existing literature on the artist. Alejandro Tapia y Rivera, the Puerto Rican poet and essayist enlisted by the Royal Development Commission of Puerto Rico to write the first biography of Campeche in 1855, never directly addressed the issue of race in his narrative of the artist’s life and seems to circumvent the topic altogether in his writing. Though he included information about Campeche’s father as well as a physical description of the artist, he did not mention any details about either figure’s life that indicated the artist’s racial designation or heritage.7 The first scholar to comment on the issue of Campeche’s race in a publication, though he did so vaguely, was Manuel Fernández Juncos in 1914, who cited the artist’s limpienza de sangre (purity of blood) as the reason he did not advance further in his career.8 In 1932, Enrique Blanco was the first historian to candidly explain that Campeche’s father was once enslaved in his genealogical research on the artist.9 Scholars working since the mid-twentieth century usually acknowledge that Campeche was a “mulatto” painter, though they refrain from engaging with questions about race and its significance to art production within their analyses of his life and career. These writers either disregard the issue altogether or emphasize how extraordinary it was that Campeche accomplished as much as he did given his non-whiteness within a hierarchical colonial society.10 While they do often mention that Campeche probably received his earliest artistic education from his father, most only consider this briefly, usually in a mere sentence, and they do not indicate that anything about this instruction was relevant to or significant for Campeche’s skill set or career, nor do they consider how Campeche’s membership in the community of free people of color in Puerto Rico may have informed the manner in which he was trained and worked as an artist. Instead, they emphasize a “great artist” narrative and promote Campeche as the island’s “first artist”, reinforcing the notion that he came from nothing and only accomplished what he did through either his alleged training by Luis Paret y Alcazar (1746–1799)—a white, European painter and academician who was exiled to Puerto Rico between the years of 1775 and 1778—or by explaining his artistic talent as being something inherent and God-given.

These interpretations of Campeche’s socioracial reality are exceedingly limited, however, as numerous studies in recent years have revealed that people of color dominated the visual arts across the Spanish colonial world.11 Moreover, such narratives of Campeche’s life and career underpin racialized nationalistic rhetoric that emerged in Puerto Rico during the nineteenth century. Prior to the end of Spanish rule in 1898, Puerto Rican writers and intellectuals began to write histories of the island from a distinctly criollo perspective, and they seized on historical figures, such as Campeche, who represented what they believed it meant to be truly puertorriqueño.12 The earliest writing that exists on Campeche is very heavily inflected with nationalistic pride, particularly Tapia’s biography of the artist, which is, as one reviewer put it, “written with patriotic fervor and enthusiasm”.13 In nineteenth-century literary circles, within which Tapia was a leader, Campeche became a “central icon of efforts to construct a Puerto Rican literary and artistic tradition”, and to be an “admirer of Campeche” came to indicate an individual’s progressiveness and devotion to the island.14 Significantly, many of the earliest histories complied by these writers also failed to acknowledge, and even intentionally obscured, the historical contributions of the island’s black population, which is highly evident in Tapia’s influential biography of Campeche and subsequent scholarship on the artist written in the late-nineteenth and twentieth centuries. Indeed, in 1934 Arturo Schomberg declared that there was a “conspiracy of silence” regarding Campeche’s race in Puerto Rico fueled by the radicalized nationalist agendas of “white Spaniards”.15 This kind of inherent racism within the writing of Puerto Rican histories persists to this day and has been discussed at length by scholars such as historian Ilena M. Rodríguez-Silva who argues that historically the Puerto Rican experience has been underscored by the white, Hispanic experience at the expense of people of color on the island.16

Not considering the subject of race within analyses of Campeche, however, overlooks a crucial component of his identity that shaped his lived experience and would have informed his career as a maker of images within his colonial milieu that should be taken into an account in the study of his art. As historians Andrew B. Fisher and Matthew D. O’Hara argue, identity for the colonial subject lies at the “nexus of categorization and self-understanding”, that is, that “…identity comprises the relationship between the categories one was born into, such as Spaniard, Indian, mulatto…and the lived reality of those categories…”.17 The colonial individual’s “lived reality” of such categories, in their argument, allows for the fashioning of identities, which in turn shapes the world or culture they inhabit, and is pertinent to an examination of a historical figure such as Campeche.18 Sociologist and historian W. E. B. Dubois further argues that the African Diaspora subject in the Americas possesses a “double consciousness”, and knows him or herself both through the dominant frameworks of white society in which they live as well as through their own local ways within their immediate communities.19 Living during the era of slavery in the Spanish Empire as a mixed-race individual, the constitution of Campeche’s sense of himself as a colonial subject was undoubtedly informed by dominant discourses coming from without as imperial imposition and locally by the dynamics of colonial society. Campeche plausibly circulated within the world of subalterns, the lower classes, free people of color, and enslaved people, which has implications for his self-understanding and thereby, his life and work. To dismiss or gloss over the issue of race in studies of Campeche diminishes our understanding of the social and cultural complexities he faced, his agency as an artist of African descent in a Spanish colonial society, and how race impacted the creation and consumption of images in Puerto Rico during his lifetime.

In response to the absence of a critical discussion of race within his historiography, this essay focuses on Campeche as an artist of African descent and argues that the socially and culturally inscribed constructs of race and Campeche’s lived experiences of them in late eighteenth-century Puerto Rico shaped and informed his participation in the arts. Just as he presented himself in his self-portrait, Campeche lived both as an artist and as a free man of color within a racialized colonial society. As such, inquiries regarding how race affected Campeche’s life and artistic practice, and particularly how his immersion in the community of free people of color in San Juan possibly impacted the manner in which he was trained and worked, allow for a more comprehensive understanding of his art production. Using comparable examples of African descendant artists and artisans active in other colonial centers, such as Mexico City and Havana, this article elucidates connections between Campeche’s socioracial reality, his artistic career, and his work through an examination of the relationship between race and art making in Puerto Rico, the broader Caribbean region, and the greater Spanish Empire during the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries. This method of approach embraces analytic strategies proffered by scholars of the Black Atlantic and Atlantic World studies who investigate how individuals of African descent exercised agency in response to their immediate, local conditions and also consider the motivating forces behind larger historical processes and systems that connect these seemingly isolated figures to a larger world of flux, trade, and the exchange of things, ideas, and people beyond the scope of national, and even imperial, historical narratives. Thinking about Campeche in these methodological terms, he ceases to be a singular example of a person of color excelling within his field in Puerto Rico, and rather becomes a member of a community of industrious figures of African descent who participated within, defined, and even challenged the expectations of the art world in the eighteenth century across the Americas.

1. Race in the Spanish Colonial World and Late Eighteenth-Century Puerto Rico

As the child of a white mother and black father, Campeche is frequently described as a “mulatto”. While on its surface this term seems to simply denote the artist’s interracial parentage, mulatto carries connotations of the complex racial history of the Spanish colonial world, and it indicates Campeche’s marginalized place within his respective society as well as the construction and experience of racial difference for people of color across the Spanish Empire during his lifetime. When the Spanish began to establish their American colonies in the sixteenth century, they transferred the social schema present in Spain to the “New World”, including the ideology of limpieza de sangre.20 While limpieza de sangre had originally been employed in Spain to ostracize those considered to lack the proper “cleanliness of blood”, which generally applied to non-Catholic peoples, in the Spanish Americas this concept was redefined and applied to the colonial populations that grew in number and in racial diversity over the centuries.21 The “colonial limpieza”, as historian Ann Twinam has called it, rather focused on legalized social stratification based on race and discrimination against those with non-Spanish (i.e., non-white and non-European) blood, specifically descendants of the native inhabitants of the Americas—“Indians”, as the Spanish called them—and Africans, who were brought across the Atlantic Ocean to provide enslaved labor throughout the colonial era.22 Over time, new categories emerged, such as mestizo and mulatto, “to address the liminal status of interracial children”, who were born as the result of the miscegenation of these populations.23 The social construction of race and the ideological machinery that is racism in Atlantic capitalist societies, driven by what historian María Elena Martínez describes as a colonial preoccupation with purity, lineage, and genealogy, operated to inscribe colonial subjects in an unequal society, composing Europeans as whites at the top of the social hierarchy as the “elite”, and people of mixed race at the bottom.24

The fear of interracial mixing played a substantial role in the constitution of Spanish colonial society. The sistema de castas emerged to classify the various mixed races, indicating their socioeconomic status and essentially disadvantaging non-white individuals by limiting their access to education and options for employment as well as placing restrictions on their behavior, customs, and habits.25 Casta paintings, which were made during the eighteenth century in New Spain and appear as either a gridded chart on a single canvas or sometimes as a series of images across fourteen to twenty separate panels, reveal the preoccupation of the upper-classes of viceregal society with the growing interracial population and their attempts to come to terms with it. Often intended to be sent back to Spain, these works provided an orderly visual representation of Spanish American society structured into clearly delineated socio-racial categories and were usually appended with descriptive texts of the specific racial permutations presented in the images. As art historian Ilona Katzew has stated, “a taxonomic current underlies casta painting”, very much associated with, or at least popularized by, the rise of Enlightenment thought and its obsession with variety and scientific categorization during the eighteenth century.26 These panels or series of panels usually begin with a representation of a Spanish (blanco) and Indian (indio) couple as the parents of a mestizo (the racial offspring of Spaniards and Indians) child and then move through various combinations of white, Indian, and black (negro) familial pairings and offspring (Figure 2). The paintings also often include clothing, flora, fauna, and other items that indicate each racial group’s socioeconomic status and professions, presenting an idealized, hierarchical view of social life in New Spain, which, Katzew has argued, served to counter anxiety fostered by the perceived threat of the castas to ordered society, and specifically, to the criollo (descendants of white Europeans born in the Americas) population.27

Figure 2.

From Spanish and Indian, Mestizo (De Español y India sale Mestizo), early 18th century. Oil on canvas, 31 1/2 × 40 3/16 in. Brooklyn Museum, Bequest of Samuel E. Haslett and Charles A. Schieren, gift of Alfred T. White and Otto H. Kahn through the Committee for the Diffusion of French Art, by exchange, 2011.86.1.

The lived realities of race in the Spanish Empire during this time were, in actuality, far more complicated than casta paintings presented. These types of works reveal more about how the upper echelons of eighteenth-century New Spanish society perceived the castas and racial mixing in general than how it was actually lived and experienced. As Twinam has explored in her extensive research on the subject, an individual’s race in the Spanish American colonies only partially corresponded to their ancestry and limpieza de sangre or skin color, as it was highly socially determined, and their skills, affluence, accomplishments, and contributions to the state could actually elevate their official, legal racial designation.28 Moreover, in the latter part of the eighteenth century, individuals of mixed race in the Spanish American world gained the ability to purchase legal whiteness through gracias al sacar rulings. This practice further complicates the notion that a person’s race tied directly to their lineage or the shade of their skin, and it additionally demonstrates that “race” was not a static concept but rather an ideology inscribed by law and made through social practices.29 In her research, historian María Elena Díaz additionally argues that the importance of race as a social determinate should not be overstated, as, “race classifications were not the sole categories at play in social life [in Spanish colonial societies]”, and, “their force could be reinforced, or attenuated and modulated, if not completely displaced, by their interactions with other categories…”.30 Generally, while race was socially significant, an individual’s calidad, or social status, was determined by a range of social factors, including wealth, social reputation, and comportment, in addition to race.31 Furthermore, an individual’s racial status was far more fluid, flexible, and complex than they are presented within casta paintings. The inherent meanings of specific racial terms in the Spanish American colonies were not stable, as categories such as indio, negro, and mestizo did not always possess the same meanings in different social or institutional settings and these meanings could also change over time.32 Martínez argues that the fluidity of the sistema de castas was due to the inconsistencies in the discourse of limpieza de sangre as well as due to the Spanish imperial structure, which failed to clearly outline regulations for the castas or clarify the status of the criollos, which she argues prompted the challenging and redefinition of racial statuses, policies, and classifications.33

The socioracial composition of the Spanish Empire varied widely based on the unique histories of each specific colonial society. While New Spain and Peru, for instance, had large native populations throughout the colonial era, and therefore more Amerindian and mestizo communities, the Spanish Caribbean was largely composed of “immigrant societies”, as it had a comparatively small native population after the sixteenth century.34 Following the establishment of the earliest Spanish settlements in the Americas on the Caribbean islands of Hispaniola in 1493, Puerto Rico in 1508, and Cuba in 1511, the native Taíno peoples were enslaved and worked to death by the Spanish and exposed to European diseases for which they had no immunities.35 When the Spanish nearly exhausted their supply of Taíno laborers, they began to import more enslaved labor from western Africa, and as the plantation economies of these islands grew in the late-eighteenth and early-nineteenth centuries, particularly following the Haitian Revolution and the collapse of Saint-Domingue’s sugar economy, the number of enslaved laborers brought to these islands grew exponentially.36 As a result of these population shifts over time, the Spanish Caribbean islands had substantial populations of African and African descended individuals, and the racial terms utilized within these colonial societies reflected a spectrum of white (Spaniards, other Europeans, and criollos) and racially mixed or black (pardo, mulatto, negro, etc.) individuals. Just as in New Spain, racial designations, especially among the free black populations, were numerous, and as Rodríguez-Silva argues, this multitude of terms should not be, “interpreted as a lack of racialized boundaries or as proof of their fluidity…this plurality of terms reflects both the attempt to catalogue racialized transgressions and efforts to resist such classifications”.37 The reasons for this resistance is clear, as people of color across the Spanish colonies were subject to specific laws that restricted their social and economic freedoms, including sumptuary laws, limited access to educational and professional opportunities, and required special tributes to be paid to the Crown.38

The paintings of Italian artist Agostino Brunias (1730–1796) more closely represent the racial and social makeup of the Caribbean islands than do the casta paintings of New Spain, though both sets of images construct racial difference within their respective colonial societies and indicate the role that images played in defining race in such settings. Between the years of 1764 and 1773, Brunias toured the West Indies as the personal painter of Sir William Young (1725–1788), a British imperial official and sugar plantation owner who served as the first governor of the islands of Dominica, St. Vincent, and Tobago from 1770 to 1773. Brunias returned to London in 1775 after Young completed his term as governor but travelled back to the West Indies in 1784 where he remained until his death on the island of Dominica in 1796. During his time in the Caribbean, Brunias completed works that captured the landscape and society of the islands. His paintings not only served as mementos for planters and government officials to carry back home to Europe, but also illustrated the manners, customs, and traditions of the people of the West Indies, specifically the African descended and native communities.39 Brunias observed the daily activities of the racially complex population of the island, including market days, festivals, cudgeling matches, and dances, which he recorded in his paintings. He labelled his figures according to their skin color and social status, rather ambiguously distinguishing between the enslaved, free people of color, and “maroons”, referring to communities of enslaved escapees that created their own societies and functioned outside of colonial law.40 In his painting Free Women of Color with Their Children and Servants in a Landscape, for instance, Brunias depicts a group strolling across the countryside of a Caribbean island (Figure 3). The varying skin tones of the individuals, combined with the quality of their clothing and the prominence of their location within the scene, seem to imply their social status and indicate that the central grouping of three lighter skinned women are the “free women of color” within the painting and that the darker skinned figures are their servants. Yet, there is no clear indication as to who the individual figures definitively are within the scene beyond the central figures, or which of the various children of different skin tones belong to which adults. Due to this ambiguity, art historian Mia Bagernis argues that Brunias’ works fail to function as ethnographic works, and she suggests that they rather highlight the constructedness of ideas of race and racial classification in the eighteenth-century Caribbean world.41

Figure 3.

Agostino Brunias (Italian, ca. 1730–1796). Free Women of Color with Their Children and Servants in a Landscape, ca. 1770–1796. Oil on canvas, 20 × 26 1/8 in. (50.8 × 66.4 cm). Brooklyn Museum, Gift of Mrs. Carll H. de Silver in memory of her husband, by exchange and gift of George S. Hellman, by exchange, 2010.59.

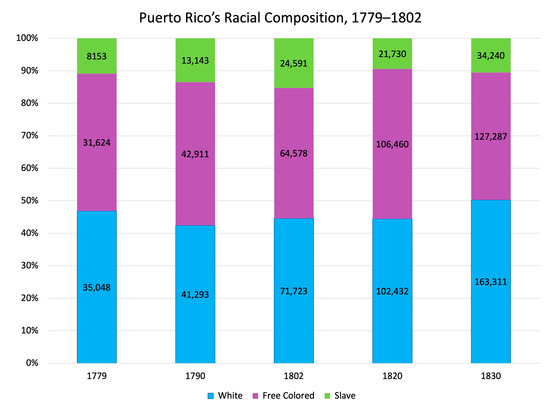

Since race was and is constituted locally as well as globally, the socioracial composition of Puerto Rico during Campeche’s lifetime deserves close attention as does its correspondence with that of the larger Caribbean region.42 The island’s large population of free people of color and small population of enslaved laborers, however, set it apart. At the end of the eighteenth and into the nineteenth centuries, white and free people of color on the island each made up roughly 40–45% of the total population, and the enslaved population made up anywhere from 10–19%, which varied greatly from the demographics of other Spanish colonies, such as Cuba where the slave population was much higher (Figure 4).43 As historian Jay Kinsbruner discusses, by the nineteenth century Puerto Ricans “recognized degrees of whiteness, generally descending from white to pardo, to moreno, to negro”, all of which are terms that appear in census documentation.44 Pardo generally referred to free people of color with the lightest skin color, moreno were those with slightly darker skin, and negro was reserved for those with the darkest skin color.45 These terms were highly fluid and flexible, however, as they might have applied to either free people of color or the enslaved, and other terms, such as mulatto, were used as well.46 The term blanco, furthermore, included people “of mixed blood” who were legally considered to be white.47

Figure 4.

Puerto Rico’s Racial Composition, 1779–1802. Based on the research of Jay Kinsbruner (Kinsbruner 1996, pp. 28–29). Graph by the author.

Racial designations employed in Puerto Rico, as observed in the broader Spanish Americas, were tied to social status, and to be “white” or blanco, in general, implied a higher position within the colonial social hierarchy whereas being a person of mixed race implied a lower position. Yet the notion of race, which operated alongside and interacted with the idea of calidad, was fluid and somewhat ambiguously shaped by both limpieza de sangre and an individual’s social accomplishments. For instance, George Dawson Flinter (d. 1838), an officer in the Spanish army who compiled a report on the island in 1832, remarked that an individual’s race in Puerto Rico generally corresponded to their social status, stating,

Flinter also reported, however, that skin color or ancestry did not definitively determine an individual’s race, as he wrote,To be white, is a species of title of nobility in a country where slaves and people of color form the lower ranks of society, and where every grade of color, ascending from the jet-black negro to the pure white, carries with it a certain feeling of superiority.

As Flinter’s account suggests, the relationships between race, ancestry, skin color, and social hierarchy on the island were highly complicated and often proved somewhat ambiguous.50 When considering how race affected Puerto Rican society during the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries, however, it should be kept in mind that it still reflected and reinforced a social hierarchy that specifically restricted the social and economic mobility of non-white individuals, and particularly those of African descent, on the island as it did throughout the Spanish American world.51 People of color, in general, were not allowed to occupy the same social spaces or positions of privilege as white individuals. For example, in his examination of Puerto Rican society in the eighteenth century, historian Ángel López Cantos discusses two men of color—Miguel Enriquez and José Concepción—who became wealthy and gained accolades through their trades. Despite their economic gains, however, they drew the ire of the San Juan elite when they attempted to exercise social privileges usually reserved for the white population. Formal complaints were launched against Concepción, who is described as a “spurious mulatto, of low trades (pulpero y regatón)”, when he requested and secured an oratorio privado, or private chapel, so that he could celebrate mass and receive the sacraments without leaving his home as his wife was chronically ill. Governor Dufresne, who wrote the complaint that was sent to the Council of the Indies, noted that the granting of this privilege upon Concepción had “caused notable scandal and grievances” for “people of noble character, to see themselves equaled with the spurious mulatto, José Concepción”.52 People of color did seem to possess a good deal of freedoms and legal protections that those in other Spanish American locales did not, including the ability to travel freely across the island, gather publicly, gain an education, acquire land, own stores, and enter most occupations.53 However, taking the example of Concepción into account, it is difficult to determine the ease or prevalence with which people of color, including the Campeche family, exercised these freedoms while negotiating the social and legal systems in which they were disadvantaged.54Although these ancient families pride themselves on their descent…they yield to the custom of the country, which considers colour in some degree a title to respect,—a kind of current nobility. Even with this prejudice, descendents of coloured ancestors, who have managed to establish proofs of nobility (called whitewashing) are not excluded from society with that inexorable severity which prevails in the French and English colonies.

2. Artists/Artisans of Color and Art Production in the Spanish Colonial World

It is arguable that Campeche, by way of his artistic talent and contributions to the church and state during his lifetime, managed to some extent to overcome the social and economic disadvantages of his reality as a man of African descent. He was assumedly welcomed as a respected artist within the highest social circles in San Juan, as evidenced by his extant oeuvre and the numerous portraits he painted of the island’s elite including Spanish officials and members of important criollo families (Figure 5 and Figure 6). However, he was still a member of the community of free people of color in San Juan. He was raised in a mixed-race family by a formerly enslaved father who worked as an artisan in various capacities around the city and would have trained his sons in his trades, and this study contends that this training was more significant for Campeche’s career than has previously been determined in scholarship on the artist. Kinsbruner and Rodríguez-Silva have demonstrated in their research that during the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries free people of color made up the majority of craftsmen and artisans on the island, as they were the population that primarily engaged in professions related to manual labor, manual trade, and that required artisanal skills, including cobblers, masons and stoneworkers, carpenters, blacksmiths, pulperos, silversmiths, and musicians.55 Rodríguez-Silva specifically discusses that official sources referred to these occupations as “despicable and petty trades”, and that the African descended communities on the island likely dominated these particular professions due to the “elites’ conflation of manual labor with blackness and slavery”.56 These findings in Puerto Rico are significant, as they are consistent with recent art historical research that examines the importance of artistic contributions made by African descendent populations in contemporary urban centers across the Spanish Americas during the colonial period. The propensity for people of color, both free and enslaved, to engage in artisan and craft professions connects Campeche and his family to a larger community of African descendent artists and artisans across the broader Caribbean and Spanish colonial world and further prompts a discussion about the relationship between race, art (and art versus craft), and formal artistic training in their respective locales.

Figure 5.

José Campeche y Jordán, Don José Mas Ferrer, ca. 1795, oil on canvas, 21 1/4 × 16 3/8 in. (54.0 × 41.7 cm), Smithsonian American Art Museum, Teodoro Vidal Collection, 1996.91.1.

Figure 6.

José Campeche y Jordán, Isabel O’Daly, 1808, oil on wood, 9 7/8 × 7 1/2 in. (25.2 × 19.1 cm), Smithsonian American Art Museum, Teodoro Vidal Collection, 1996.91.2.

In Mexico City, the politics of guild reform and repeated attempts to establish an official academy of art during the eighteenth century tied directly to issues of race and concerns about the burgeoning casta population that dominated the artisan professions. Art historians Paula Mues Orts and Susan Deans-Smith have both demonstrated that as early as the late-seventeenth century, white (criollo and peninsular, or Spanish) artists defended painting in particular as one of the liberal, and not mechanical, arts, through an emphasis on the intellectual foundations of their artistic practice. In so doing, they endeavored to set themselves apart as “artists” distinct from “artisans” or “craftsmen”, in a specific effort to elevate their social standing as well as the image of their profession.57 Their arguments paralleled those being presented in Europe during this time, particularly by writers of the Hispanic Enlightenment, such as Gaspar Melchor de Jovellanos (1744–1811), who advanced discourses about the arts that created delineations between the mechanical arts, the liberal arts, and ultimately, the fine arts. In 1781, Jovellanos wrote his Elogio de las Bellas Artes (In Praise of Fine Arts), and argued that “eminent artists are necessary for the glory of the nation and its ornament for the completion of the grand tasks of government”.58 Concurrently in Spain, prominent artists, such as Anton Raphael Mengs (1728–1779), asserted that painting was a “noble art”, that required “the superiority of the understanding and noble mind which he ought to have that practices it”.59

These contentions about the status of the artist across Europe and the Americas heralded a new era, as historian Larry Shiner asserts that prior to the eighteenth century, “artist” and “artisan” were used interchangeably, but by the end of the century these terms “had become opposites; ‘artist’ now meant the creator of works of fine art whereas ‘artisan’ or ‘craftsman’ meant the mere maker of something useful or entertaining”.60 The establishment of academies of art, which supported a neoclassical aesthetic and formalized artistic training, substantiated or gave weight to the theoretical divide between these professions, as these terms further came to imply a certain difference in the kinds of work performed. “Artist” referred to the creator of painting, sculpture, and architecture, which were the major categories of art defined by the academy, and “craftsman” or “artisan” applied to the professions which required manual labor, such as the those associated with the decorative arts. Art historian David Craven advances this notion further and claims that a primary distinction between art and craft dates to the Renaissance and the foundations of capitalism.61 He describes that the difference between a “fine artist” and a “craftsman” came to be “based on the specific form of art being used, namely, whether it was ‘decorative’ art (furniture, porcelain, tapestries, etc.) used to some extent by all classes or fine art (painting, sculpture) commissioned almost exclusively by the ruling classes”, thereby linking social class formation and status to the connotations of art and craft.62

While artists in Mexico City supported the ennoblement of the artist and the profession of painting in a similar manner as their European contemporaries, their underlying motivations were reflective of their specific cultural milieu and stemmed from concerns about their position within the diverse socio-racial hierarchy of New Spain.63 These artists sought to protect their status in society and further distance themselves from the artisan population that was “increasingly dominated by castas and thus associated with debased calidad…”.64 Deans-Smith examines how white artists constructed their status and identity in relation to the castas, resulting in the racial inflection of their identities. She argues that the artists, through their works and especially the casta paintings series that emerged in Mexico City at this time, “contributed to the production of the colonial imaginary with its objectified and idealized socio-racial hierarchies represented in their…casta paintings”.65 These works, she argues, with their clearly delineated castas, were very likely a response to these artists’ own anxieties about the encroachment of the castas into their profession. Deans-Smith also contends, however, that attempts to impose racially restrictive policies against the castas were not just about race, as these artists wanted to restrict untrained and unlicensed craftsmen whom they disparaged as the source of inferior quality artworks.66

The colonial elite’s endeavor to establish an academy of art in Mexico City, while inspired by reformist Bourbon agendas and Enlightenment philosophies about social and economic progress as suggested by Jovellanos’ quote, was also an attempt by painters in the city to distance themselves from the guilds, in which the castas were extremely active. Guilds are trade organizations found in most cities in Europe, and subsequently the American colonies, since the expansion of towns and cities in the early Middle Ages. They governed professions and controlled trade, limited outside competition, established standards of quality, and set rules for the training of apprentices in the workshops of professional masters. Membership within these guilds was usually required in order to practice a specific trade within a city and its territory.67 As art historian Rogelio Ruiz Gomar demonstrates, since the sixteenth century the profession of painting in New Spain remained open to anyone of any race, unlike most other guilds where one had to be Spanish to become a master.68 There are examples of artists of color gaining great esteem and executing important commissions in Mexico City, though named examples are few in number. Juan Correa (1646–1716), a self-proclaimed mulatto who was made a master of the painter’s guild as of 1687, and his pupil José de Ibarra (1685–1756), who was also of African descent and became a master by 1728, both led respected careers and cultivated a wide variety of clients, including colonial officials, members of the criollo elite, and various religious orders.69 Correa even signed a guild ordinance in 1693 as, “mulato libre, maestro pintor”.70 Since the end of the seventeenth century, however, white painters attempted to exclude casta artists from their workshops as well as from membership to their guild associations, which they were ultimately unsuccessful at doing.71 Beginning in the eighteenth century, white painters repeatedly attempted to form an academy of art with racially restricted admission guidelines in order to separate themselves from and elevate themselves above casta artists.72

When the Royal Academy of San Carlos was finally established in 1781 by Spanish engraver Jerónimo Antonio Gil (1731–1798), he initially staffed the academy with local artists, but soon after replaced them with Spanish academicians to ensure that the academy’s instruction “reflected peninsular rather than local” standards of taste.73 Gil disdained local artists and found them to be inferior, writing, “All of the abuses caused by ignorance…cause horror…in effigies, altar screens, and public shrines. We see nothing but our own dishonor in the hands of Indians, Spaniards, and Blacks who aspire without rules or fundament to imitate Holy Objects”.74 Moreover, the establishment of the academy resulted in the marginalization of the guilds, which further alienated artists of Amerindian and African descent. The efficacy of the academy to restrict the participation of the castas in the painting profession in Mexico City should not be overstated, however, as formal complaints were made about “intruders and offenders”, who sold paintings and sculptures to the public outside of the academy’s purview.75

In Havana, the white elite possessed many of the same concerns about the large number of people of color who participated in the visual arts as they did in Mexico City, as castas played an active role in the artistic production of Cuba through the creation of mural paintings, portraits, carved wooden carriages, and painted images of saints.76 While colonial populations in New Spain, however, included large numbers of Amerindians and mestizos, Cuba’s colonial population was primarily comprised of “Spaniards, black Africans (known as morenos/as in Cuba), and their progeny mulattos (known on the island as pardos/as)”, and by the early nineteenth century there was a growing concern among the white elite specifically over the prominence of people of color in the arts.77 Art historian Linda Rodriguez maintains that though the elite were wary that people of color dominated the artistic fields in Havana, they still continued to commission mostly black artists to create the portraits and murals that decorated their homes “as they had little choice”.78 Debates raged on the island, as they did in New Spain and elsewhere, about the nobility of the artist, as evidenced by a letter from a group of “professors of the liberal art of painting”, which protested the formation of a painter’s guild in 1770. Rodriguez argues that this letter demonstrates that this group wished to raise painting as a practice above that of a “mere trade” and separate themselves from the black artists on the island.79

The politics surrounding the establishment of the Academy of San Alejandro in 1818 likewise revealed the racial anxieties of white artists in Havana. Cultural historian Sibylle Fischer, for instance, argues in her examination of Cuban wall painting that it was an elite white institution “founded as a reaction to the African dominance of the visual arts in Cuba”.80 The academy explicitly excluded people of color from studying there, and Fischer argues that they embraced drawing, instead of painting, as its primary mode of instruction, “…not because it was more useful but because it was not contaminated by the primitive practices of painters of color”.81 She ties the white elite’s anxieties about the black population to the escalation of racial tensions in Cuba in the wake of the Haitian Revolution, which not only resulted in a huge increase in the enslaved population in Cuba but additionally heightened concerns about slave revolts on the island.82 Art historian Paul Niell, while agreeing with Fischer that racial tensions rose on the island during this tumultuous time in the Caribbean, and that white creole artists attempted to control the production of art through the academy, disagrees that the academy avoided the painting curriculum and emphasized drawing because of its association with people of color.83 Niell rather situates the founding of the academy and its related sociopolitics against the heightened implementation of the Bourbon Reforms in Cuba following the British capture of Havana in 1763, which made the opening of drawing schools part of the larger Spanish imperial project. He contends that drawing instruction in the academy can be seen, “as an attempt to inject buen gusto into the arts of Havana, a project that was a part of a long-term strategy…organized, to wrest artistic production away from the people of African descent”, and further that the academy, “served as a tool in the development of a more comprehensive representational regime of displacement, exclusion, and cultural renovation based on local conditions”.84

Comparable to Mexico City, however, denying people of color access to academic instruction in Cuba did not completely impede their participation in artistic production on the island. Vincente Escobar (1762–1834) earned great esteem as a portrait artist in Havana at the end of the eighteenth and beginning of the nineteenth centuries and continued to be successful long after the establishment of the academy. Escobar, a “pardo”, was self-taught at the beginning of his career but sought instruction at the Royal Academy of San Fernando in Madrid in 1792, making him the first artist, of any race, from Cuba to do so.85 Despite his formal training in Europe and his development of a neoclassical style, which Rodriguez attributes to his exposure to major figures in the development of Spanish neoclassical painting in Spain, there is no evidence that Escobar was ever invited to join the academy in Havana.86 Regardless, he was highly regarded for his skills as a portrait artist, and his portrait subjects ranged widely to include members from all levels of colonial society in Cuba, including the Captains General, prominent criollo families, criollo administrators, members of the royal army, as well as Spanish and criollo clergy and intellectuals, and Rodriguez estimates that more than half of the subjects of his portraits were of criollo society.87 Escobar further took on students as a master artist, including Juan del Río (b. 1748) who was also a person of color.88

Beyond the examples of Mexico City and Havana, evidence abounds that people of color dominated professions related to the creation of art throughout the Americas. In Cuzco, similar to the examples already considered, the regulations of the guild of painters and guilders from 1649 specifically prohibited the teaching of any person of color, including, “mulatos, negros, and zambos ni ostras castas”, in an effort to restrict their participation in artistic vocations.89 While Brazil lies outside of the Spanish American realm, European travelers noted the large number of “black peddlers” on the streets of Rio de Janeiro and Salvador, indicating their participation in the production of artistic wares as well.90 Historian Lyman Johnson argues that artisan and craft professions in general had a specific draw for enslaved people and free people of color due to the availability of jobs, which was a result of the white population’s general disregard for manual labor, and because it was a legitimate means by which skilled enslaved laborers could earn wages and accumulate savings.91 These trades tended to yield higher earnings, and in the Spanish colonies where the enslaved could secure their freedom through coartación, or self-purchase, enslaved artisans and their family members gained their freedom through manumission more frequently than other segments of the urban enslaved population.92 Moreover, the growth of the free black artisan class was promoted by “the clear tendency of black families, slave and free, to place their sons in artisan trades”, because they offered the highest wages and the most reliable employment opportunities.93 Artisan trades further provided what historian Matt Childs describes as “avenues of advancement” for people of color who were eager to improve their own social position, and in his research centered on Cuba he demonstrates how the success of free people of color in the skilled and artisan trades even resulted in, “a certain degree of bargaining power with the state” due to their professional success and wealth.94

In Puerto Rico, comparable to the broader Spanish Americans, free people of color and the enslaved population led the artisan and craft professions, and as has been discussed, Campeche’s father, Tomás, worked as a builder, gilder, and painter. In this capacity, he was likely employed by the colonial government on Bourbon construction projects, and it is known that he worked for religious institutions on the island. Art historian René Taylor suggests that due to Tomás’ skill set, he possibly created altarpieces or even paintings for churches in Puerto Rico, but no known works by him survive to definitively prove this suspicion.95 We may also assume, as he was able to secure his own freedom and purchase multiple properties, including the two-story house Campeche lived in his entire life on Calle de la Cruz in San Juan, that Tomás was at least moderately successful at his trades.96 As Tomás’ son, it is tenable that Campeche would have received training from his father in carpentry, building, gilding, painting, and any other skill he possessed, leading to the development of expertise required to secure future employment. The training that Campeche received from his father, in addition to evidence that suggests that Campeche worked with, and potentially trained, other members of his family, including his brothers Miguel and Ignacio, his nephew Silvestre Andino y Campeche, and his sister Juana, reveals that the Campeches ran a workshop out of their home that functioned as a center of visual production in San Juan.97 The sheer quantity of works extant from the end of the eighteenth century in Puerto Rico that can be attributed to the Campeches, particularly small religious paintings on wood panel intended for private use, and which vary in technical quality, indicates a kind of workshop-style production of these images. See, for example, the numerous copies of the Virgin of Belen images created by Campeche (Figure 7). During Tomás’ lifetime, it is plausible that he served as the head of the workshop as the senior male member of the family, training his children in his trades, and then after he passed away in July 1780, José became head of the family and the workshop. Campeche’s sisters indicated his dual role within their household, as they claimed that their brother “took charge with the functions of a father”, and supported the family through his diligent work for the church and state.98 This manner of working and the dissemination of generational knowledge through a family workshop in this way is very common in the history of Western art, particularly under the guild system, as master craftsmen often ran workshops out of their homes and would then train their sons as apprentices in their trades.99 It is arguable, therefore, that the means by which guild members are trained—via the passing of knowledge from a master to an apprentice, oftentimes from father to son—is a similar means by which Campeche received his earliest training. This supposition implies that Campeche’s artistic training by his father was not insignificant simply because Tomás was a black artisan and not an academically trained “artist”, as it ties Campeche to an established tradition of artistic and artisanal training associated with guild membership that was highly formalized and the method by which artists were educated for centuries prior to the rise of the academy.100

Figure 7.

José Campeche y Jordán, Nuestra Señora de Belén, late 18th century, oil on copper, 9 1/2 × 7 1/2 in. (24.2 × 19.2 cm), Smithsonian American Art Museum, Teodoro Vidal Collection, 1996.91.7.

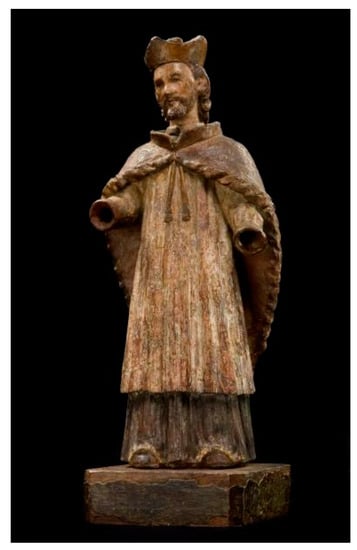

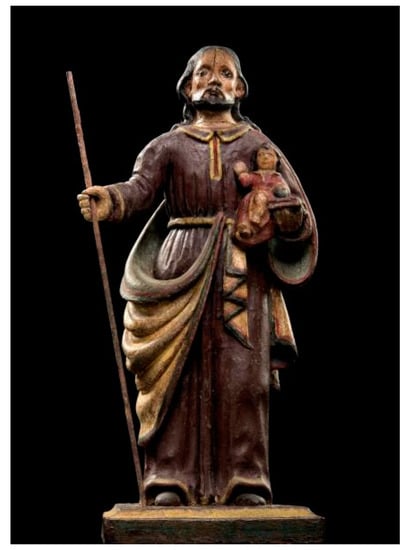

The relationship between the family workshop and the guild system is notable in our consideration of Campeche because, as has already been discussed in several examples, artisanal guilds were commonly associated with free people of color and their enslaved counterparts across the Spanish Americas. Guilds were active in San Juan at the end of the eighteenth century and into the nineteenth century, but no documentation exists or has been found about these guilds’ activities that would allow us to definitively determine the extent to which black artisans were members or not.101 Regardless of this lacuna of information, knowing that the majority of artisans in particular professions were free people of color and/or enslaved, it seems reasonable to assume that they were additionally members, to some extent, of these guilds, which would make them familiar with guild structures, practices, and methods of training. While the singular example of the Campeches might not be enough to establish a definitive relationship between the guild-structured family workshop and black artisans in Puerto Rico, the existence of another mulatto family who also worked in this way lends some weight to an argument that this may have been a common working method and business model for free artisans of color on the island. The Espadas, who lived and worked in San Germán, Puerto Rico, located in the far southwest corner of the island, specialized in woodcarving and created religious sculptures, furniture, and carved altarpieces, and they are known to have completed sacred paintings for private devotion as well as religious institutions on the island.102 Felipe de la Espada (ca. 1754–1818), who was a free man of color and possibly formerly enslaved, is renowned for his work as a sculptor of santos figures (colorful wooden images of saints that are used in private devotion) and he and his son, Tiburcio, were the most prominent santeros (santos makers) in Puerto Rico during the Spanish colonial era (Figure 8 and Figure 9).103 Felipe owned and operated a workshop at 35 de la Calle del Comercio (now Dr. Santiago Veve street), near the church and the main street of his era, and he and his family produced a prolific amount of art during his lifetime. After he passed away in 1818, his sons continued the family business.104 Parallels between the Espadas and the Campeches—free mulatto families who produced copious numbers of religious sculptures and paintings—indicates that family workshops were conventional to some extent among free artisans of color in Puerto Rico, and further research on the training and working methods of black artists and artisans in other locations could reveal this to be a broader pattern across the Spanish Americas.105 A significant difference, however, between the access free people of color or the enslaved may have had to artistic training in Puerto Rico, including the Campeches and Espadas, and that which was available to those working in other colonial centers such as Mexico City or Havana, is that there was never an academy of art established in Puerto Rico under Spanish rule, nor was there a drawing school opened in San Juan prior to 1800.106 The long-standing workshop or family workshop method of training is potentially all that was available to these communities at this point in time, or at least, all that had been modeled for them locally due to the absence of an academy.

Figure 8.

Felipe de Espada, San Juan Nepomuceno, late-18th or early-19th century. Carved and painted wood. Washington, D.C., Smithsonian American Art Museum, Teodoro Vidal Collection.

Figure 9.

Tiburcio de Espada, San José y el Nino, late-18th or early-19th century. Carved and painted wood. Washington, D.C., Smithsonian American Art Museum, Teodoro Vidal Collection.

Existing scholarship on Campeche overwhelmingly frames him as “Puerto Rico’s first great artist”, focuses primarily on his work as a painter, and leans heavily on his purported relationship with Luis Paret y Alcázar as the means by which he obtained his most important artistic education. However, these propensities within research on Campeche obscure the connection between his identity or experiences as a free person of color, within his family unit and as part of his immediate community of free people of color who generated the artistic production of the island, and the manner in which he trained and worked. None of this is to say, however, that Campeche’s work was not considered to be exceptional during his lifetime or that he did not receive accolades from his contemporaries that set him apart from the idea of being merely a “craftsman” or “artisan” in a strictly utilitarian sense. For instance, Don José Martin de Fuentes, a Spaniard present for the 1789 celebrations of the coronation of Carlos IV in San Juan, mentioned Campeche by name in a letter that he sent to Madrid describing his own, albeit highly critical, version of the festivities, stating that,

While the nature of this letter is not positive by any means, it does communicate that this visiting Spaniard knew of Campeche and his reputation as a skilled artist. His declaration that the royal portraits were “made by the son of a black named Tomás Campeche”, reveals that Martin knew who the artist’s father was and that he was a man of color. Further, by disagreeing with the notion that he should be called an “inimitable painter”, the Spaniard further conveys that Campeche was well respected by the local community. Cabildo records from 1808 discussing the commission of a portrait of Ferdinand VII for the celebrations surrounding his coronation describe Campeche as, “the skillful professor of painting José Campeche”.108 Furthermore, when the artist’s sisters, Lucía and María, appealed to the government for financial support following his death and claimed that he was “not only the best painter and only physiognomist in this city and island, but he was remarkably superior to many others in these faculties”, the Cabildo agreed with them and certified their statements about their brother.109 Following his death in November of 1809, his death certificate specifically classified him as a “patricio” (patrician, or noble), a term which indicates the respected place he had earned in San Juan society during his lifetime through his art and additional work for the church and state.110…the poor balcony [of the town hall] is so moth-eaten and old that is seems unable to hold the royal standard and the royal portraits. These were made by the son of a black named Tomás Campeche; though I cannot but say that it is praiseworthy that a young man of his dark color, quality, and class, without ever having left Puerto Rico or having had a master, and with no more ingenuity to enable him to do what little he does, it is impossible to agree that he should be called the inimitable painter José Campeche.

An issue emerges specifically in the tendency to emphasize Campeche as Puerto Rico’s “first artist”, because it overdetermines his role in San Juan society and overlooks the labor he performed outside of the bounds of the traditional definition of “artist” following the rise of the academy. As Childs argues in his analysis of Cuba during this same time, free people of color gave substantial meaning to their freedom by their own labor.111 To divorce Campeche from his mulatto identity or experiences and the consideration of its impact on or relationship to his life and career removes the evidence of this labor, resulting in an erasure that creates an understanding of the artist that fails to reflect the breadth and complexity of work he undertook within his respective milieu. To focus on him as merely a painter who accepted commissions from elite members of San Juan society and prestigious institutions on the island and who was potentially trained by Paret, predisposes scholars to neglect the issue of race in the examination of his life and work, and essentially whitens Campeche. Tapia, for instance, refers to Campeche’s father, Tomas, as a “craftsman” and “artisan”, but specifically calls Campeche an “artist” and “painter”, distancing Campeche from his father, his family, and their work.112 Based on the research presented here regarding comparable communities of black artisans in the Spanish American world, however, it is reasonable to propose that Campeche possibly got the jobs he did with the Bourbon government as a draftsman—which possibly led to introductions to colonial officials who required portraits—and with various churches—as a musician and painter of the religious artworks that make up the majority of his body of work—due to his father’s connections or even to his own as a member of this community of black artisans in San Juan who cultivated working relationships with these institutions. By and large, the kinds of work Campeche did during his lifetime, as a painter of not only portraits, but religious works for churches and private devotion; a musician; and even builder, as he designed and built the catafalques for Carlos III and Pope Pius IV and an organ for the Franciscan church, parallel the kinds of work relegated to free people of color and the enslaved in Puerto Rico, the broader Spanish Empire, and the Atlantic world: manual labor and trades commonly performed by black artisans and craftsmen. When examining Campeche, it is necessary that we consider the total extent of the work he performed, because an examination of him or his career without a consideration of his background as a free man of color, or his work that falls more under the labels of “craftsman” or “artisan” historically, proves to be reductive and fails to reveal who Campeche was within his colonial society as a maker of images and visual art.

There is additionally something to be said here about Campeche’s agency as a man of color who took advantage of the resources and possibilities available to him in his colonial setting and thereby developed skills that allowed him to raise himself up in his respective society, or gain cultural capital, though his artistic labor. We know that Campeche received his earliest artistic training from his father, as had been discussed, but he likely gained artistic knowledge from other sources as well. Campeche received some formal education from the Dominican Order and he worked for various religious institutions in San Juan, which would have allowed him access to religious prints and imagery. Based on the similarities between his religious paintings and engravings from the eighteenth century, scholars have suggested that he most likely used prints as guides or patterns for some of his religious works.113 He was also likely educated by the military engineers that came to the island at the end of the eighteenth century whom he worked alongside to complete drafting projects for the colonial government, and Paret could also have been a source of some artistic knowledge for Campeche during the late 1770s. In this manner, Campeche potentially took advantage of multiple opportunities available to him, gaining access to knowledge that allowed him to take on diverse roles as an artist and maker of images in this late Spanish colonial setting.

The history of the Campeche family in general is a history of innovation and resilience. Tomás bought his freedom from his owner—Juan de Rivafrecha, a canon of the Cathedral in San Juan—and went on to become an evidently successful businessman, running a profitable workshop that allowed him to support his large family, train his children in his trades, and purchase multiple properties. He also apparently chose to distance himself from his identity as an enslaved person, as he changed his name from “Tomás de Rivafrecha y Campeche”, following the custom of enslaved people to take the last name of their owner,114 to “Tomás Campeche y Rivafrecha”, over time, and then simply to “Tomás Campeche” by the date of his death.115 Campeche’s sisters similarly navigated the legal avenues available to them when they sought financial assistance from the government in the months after their brother died. Through their letter-writing campaign, which was ultimately successful in securing funds for their family, Lucía and María demonstrated their “colonial literacy”, or their knowledge of and ability to maneuver within the standard communicative structures of the colonial/imperial system from their place in Puerto Rico.116 They strategically composed their letters to garner sympathy for their family’s plight and to promote Campeche as a devout, moral man as well as a “faithful vassal, lover of his king and nation”, which was presumably instrumental in securing the Cabildo’s certification of their initial missive and in obtaining the endorsing testimonies of Governor Salvador Meléndez and Bishop Juan Alejo de Arizmendi. In fact, considering the copious amount of detail that Lucía and María included about Campeche’s life and career in their letters, they should arguably be considered Campeche’s first biographers, rather than Tapia, who strongly relied on the sisters’ letters for information about the artist when writing his 1855 publication. Yet, this framing of the Campeches, as industrious, savvy businesspeople of color who exercised their legal rights in support of their interests, runs counter to the established narrative of the family. Tomás is often discussed as a poor artisan, and Lucía and María are characterized as beggars, which reveals the inherent racism, and even sexism, in the way in which they have been examined thus far. However, it is clear that the Campeche family knew how to navigate the colonial/imperial systems that were imposed upon them, and they supported themselves despite the disadvantages they faced as people of color in a hierarchical socioracial society.

3. Campeche’s Self-Portrait

As this examination is driven by questions about the significance of Campeche’s race, or more specifically, the significance of his experience of the social constructs of race and how it may have impacted his life, identity, artistic agency, and prolific career as a maker of images in late-eighteenth and early-nineteenth century Puerto Rico, his self-portrait warrants further consideration. This image provides some insight into, or at least allows us to theorize about, these specific issues from the artists’s perspective. While the original painting created by Campeche’s own hand is no longer extant, the knowledge of its existence and the survival of copies made after the work, particularly Atiles’ version which has been determined to be the most faithful rendering, allow us to analyze the implications of such a representation: the self-portrait of a “mulatto” individual who depicted himself as an artist during the era of slavery in the late colonial Spanish World.

Campeche’s presentation of his mixed-race body in the form of a self-portrait presents challenges to the traditional use and understanding of portraiture during this time. Generally, black individuals did not appear as primary subjects within portraits but were rather presented in the backgrounds of portraits of white individuals.117 The inclusion of servants of African descent in portraiture was considered to be fashionable throughout Europe and the Americas during the age of slavery and colonial expansion.118 Within such works, the enslaved person or page played a supportive role and was reduced to a non-individualistic “type” that functioned to communicate something about the white subject of the portrait. Indeed, as the contributors to Slave Portraiture in the Atlantic World consider and as articulated by the editors, “it is this sort of typing, in tandem with the broader social and visual dynamics of the Atlantic slave trade, that helped to forge the still indelible link between black existence and enslavement”.119 Moreover, they argue that “our modern history of racism…has denied singularity and individuality as subjects to non-Europeans and especially to those who have been enslaved…construed as “others” within racialized Western/modern notions of personhood…”.120 The representation of a person of color within a portrait is somewhat paradoxical, therefore, as the body of the enslaved, or that of an individual of African descent by extension, “…appears as the site of the non-subject, of an entity without memory or history—the slave as a pure bodiless and immanence”, whose, “conditions of existence and visibility have been historically under erasure”.121 While portraiture, the visual representation of an individual, on the other hand, resolutely, “insists on the face as a primary site of an imagined subjectivity”, and, “[demands] that the viewer grant a subject reality to the image made visible on the canvas”.122

Additionally, as a self-portrait, Campeche engages in self-conscious visual self-fashioning that reveals a marked sense of identity contrary to the common representation of a black figure in art during this time and that he intended to convey something about himself and his identity through this image.123 In particular, he presented himself as a painter in this work, very much in the tradition of the great masters of the art historical canon who portray themselves as artists in the midst of creating a work of art. Depicted in this way, artists often presented themselves as “genius” or “creator” through the visualization and resultant substantiation of their artistic skill and sought to gain acknowledgement for their talent and intellect. An well-known example of this kind of work includes Diego Velázquez’s (1599–1660) Las Meninas (1656), wherein the artist depicts himself in the act of painting the royal family of King Philip IV.124 Rather than simply presenting himself as an official court painter and member of the royal entourage, however, he paints himself as a recipient of the prestigious Order of Santiago, an aristocratic order whose membership elevated the social status of painters to that of nobility.125 Velázquez not only insinuated his prestigious position as an artist in the court but additionally displayed his elevated status, which he achieved through his skill and talent as an artist. Interestingly, Velázquez painted the earliest known example of a portrait of a Spanish man of African descent, Juan de Pareja (c. 1606–1670), who was not only enslaved as a member of Velázquez’s household, but was also an artist in his own right, having trained in Velázquez’s workshop and worked as the master artist’s assistant (Figure 10). This painting, therefore, while not an artist self-portrait, is still a portrait of an artist, and its details, such as the attention paid to Pareja’s hand and the careful separation of his fingers, suggests the importance of the use of his hands in his work and implies his labor as both an artist and as an enslaved person.126

Figure 10.

Diego Velázquez, Juan de Pareja, 1650. Oil on canvas. 32 × 27 1/2 in. Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York. Purchase, Fletcher and Rogers Funds, and Bequest of Miss Adelaide Milton de Groot (1876–1967), by exchange, supplemented by gifts from friends of the Museum, 1971. 1971.86.

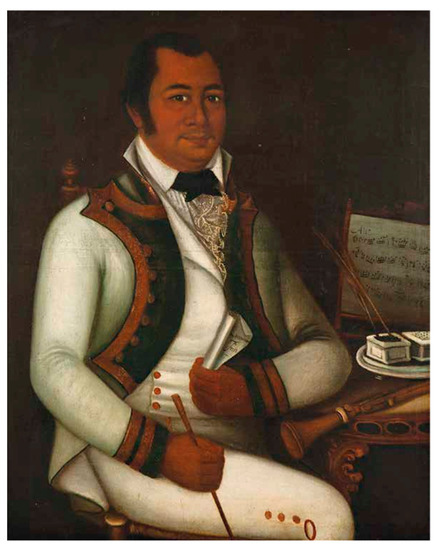

More contemporary with Campeche, artist portraits from the Spanish American colonies evidence the growing consciousness of artists as “individual masters”, set against debates about guilds and the foundation of academies, and reveal the concern painters had at the time for their status in society as well as that of their profession.127 In New Spain, artist portraits independent of a larger composition, which were extremely uncommon during the viceregal era according to Gomar, emphasized the intellectual foundations of painting and visualized it as a “noble” art.128 Juan Rodríguez Juárez (1675–1728) created the first known artist self-portrait in approximately 1719, and within the unfinished work, he presents himself in a half-length format, body turned slightly to the left to gaze out directly at the viewer, holding a paintbrush and positioned in front of a canvas (Figure 11). In the portrait, Rodríguez Juárez specifically chooses to present himself as a painter through the inclusion of the tools of his trade, and again, with an emphasis in the composition on his hand as evidence of his skill in the very work we are viewing.129 Another potential self-portrait exists from the first half of the eighteenth century and is assumed to have been painted by José de Ibarra, which, if it really is by José de Ibarra, would make it the only known example of a self-portrait by an artist of African descent in the Spanish Americas prior to Campeche’s own portrait (Figure 12). In the work, Ibarra appears in dignified dress, similar to Rodríguez Juárez, and presents himself poised at his easel with a brush in his hand in a moment of thoughtful reflection, revealing the intellectual dimensions of painting relevant to his own concerns about art making in Mexico City, which he made known through a petition that he submitted that, among other things, tried to keep individuals of lower calidad out of the painting profession.130 Through self-portraits and the inclusion of signatures that state that the artist “made” (fecit), “painted” (pinxit), or “invented” (invenit) a work of art, an evident self-awareness of the artist emerged during the seventeenth and eighteenth century in New Spain that demonstrates an understanding of the artist as an intellectual and of painting as a fine art as defined within contemporary debates about the field.131 Similar to these examples, in his own self-portrait, Campeche positions himself in front of an easel in a statement about his authorship of the work and as a testimony to his own skill and competence as a painter. Campeche also occasionally signs his works with a signature that implies his specific creation of a work of art or of a composition, staking his claim on his own intellectual property and further emphasizing his conscious creativity as an artist.132

Figure 11.

Juan Rodríguez Juárez, Autorretrato, c. 1719. Oil on canvas. 66 × 54 cm. Mexico City, MUNAL/INBAL.

Figure 12.

José de Ibarra, Autorretrato, first half of the 18th century. Oil on canvas. 57 × 42 cm. Mexico City, MUNAL/INBAL.

A discussion of what it meant for Campeche to present himself as both a free man of color and a painter in the late Spanish colonial world may additionally be situated against a portrait created by Escobar. Though there is no known example of a self-portrait by the Cuban painter, he created numerous portraits for Cuban society, including one of a free man of color, a mulatto musician named José Jackes Quiroga (n.d.) (Figure 13). In the work, Escobar portrays Quiroga in a three-quarter length composition. Turned slightly towards the viewer and clutching a conductor’s baton in his right hand, he sits beside a table on which he props his left elbow and presents the tools of his profession: sheet music, quill and ink pots, and a flute.133 Quiroga likely belonged to a social group in Havana referred to by historian Pedro Deschamps Chapeaux as a “bourgeoisie of color”, which was comprised of men and women, including Escobar’s own family, who were enlisted in the black militias and many of whom worked in trades that white Cubans “deemed ignoble and refused to pursue”.134 Moreover, both Quiroga and Escobar could be included in what Deschamps Chapeaux refers to as the “social ascension” of blacks, “into new fields beyond the manual trades” which included professions such as literature and journalism.135 Though this is not a self-portrait, the subject matter likely had personal relevance for Escobar, as considered in the online exhibition Digital Aponte, “Through his tools, Escobar marks Quiroga’s musical expertise, accomplishments that resonate with Escobar’s career as a portraitist”.136 As Rodriguez considers, Escobar sought to elevate himself socially and racially through his artistic practice, and he, “resisted Enlightenment visions of the place of blacks in the arts”.137 Specifically, she argues, “Considering artistic practice as a cultural practice, we are able to interpret different the history of art in Cuba and that of the community of free people of color…Yet, in 19th century Cuba…labor…especially that related to creative enterprise…could offer prestige and wealth to those free people of color who engaged in such work. Escobar…capitalized on this possibility of transformation”.138 An argument could be made, comparable to Rodriguez’s assertions about Escobar, that Campeche elevated himself within society through his artistic practice. His self-portrait, therefore, could be considered as a statement about his labor, made apparent in the portrait through the inclusion of an easel and a painting, which allowed him a certain amount of social mobility or versatility despite his race. This possibility is supported by the breadth of commissions and accolades Campeche received from the people of Puerto Rico above and beyond any other artist that may have been working there during his lifetime and well into the nineteenth century.

Figure 13.

Vincente Escobar, Retrato de José Jackes Quiroga, c. 1800. Oil on canvas. Cárdenas, Cuba, Museo Óscar María de Rojas.