1. Two Stories about Self-Orientalization

The date is 22 February 1933 (or somewhere near there). We are in New York City, or Atlanta, or maybe Boston. Uday Shan-kar (advertised with a hyphen) and his Hindoo Troupe (sic) are about to perform. Alternately, we are at the Santa Monica Civic Center on Saturday 20 October 1962, for the same purpose. We could also be at Shankar’s (the hyphen gone in the later tours) last U.S. performance with his troupe on 24 November 1968, at the Civic Theater in San Diego. The North American press, has been laudatory from the start:

“The most notable novelty, as well as one of the most provocative and delightful events of the dance season”.

-John Martin, New York Times 1932

“Nothing so exotically beautiful since Mei Lan-Fang”.

-New York Post, 1937

New York Public Library, *MGZB (Uday Shankar)

“Shan-Kar’s dancing in extraordinary. Blessed with a beautiful body and exhibiting the poise and detached passion of his race, he dances not only with his feet, his hands and arms, but also with his body and facial muscles”.

-Cue Magazine, 1932

“Mr. Shan-Kar is nevertheless canny and clever. He has brought the Orient to us, but he has not forgotten that the street is Broadway. His program is well built and varied, his music is calculated in the proper emotional key and the plan of his dances, while unquestionably orthodox, is always built to an effective dramatic climax”.

-Mary F. Watkins, Herald Tribune, 1932

“All you had to do was sit in your chair and enjoy the beautiful colors of the costumes and stately, pretty or delightful gestures of the performers”.

-Morning Post, Robert Resiss, 1932

The month is November 2022. We are in Santa Monica, CA in an artist’s studio (ok, the author’s studio) where the above performances and related histories are being processed, digested, and placed into a dancing guise for contemplation and reflection. We are on Zoom as Lionel Popkin presents the sketch of his ideas to a working group of process-oriented artists who identify as part of the South Asian diaspora. The show being discussed is over a year away (Spring 2024) and the air here is less presentational, and more workshop-based. Popkin traverses between multiple imageries and iconographies rooted in his diasporic upbringing, and the conversation that ensues tracks issues of expectations, questions of purpose, and structural decisions. The press has no clue this is happening.

My goal in this essay is to discuss how orientalism has operated and continues to operate within the North American artistic landscape of dance artists who identify as South Asian.

1 To do that, I start by focusing on one of the major, though often overlooked, figures over the last 100 years of South Asian (and predominantly Indian) dance performance on the concert stages of what we now call the United States. My goal is not to provide a comprehensive history, but rather to zero in on a particular example to consider how orientalism, the desire for authenticity, a nationalist agenda, religious fundamentalism, economic necessities, multi-cultural initiatives, and diversity desires all interact and coalesce to form an undercurrent of limited potentials about how and why South Asian dance can exist within the American performance discourse. Uday Shankar (1900–1977), began his career in the 1920s, touring with Anna Pavlova as part of her

Oriental Impressions suite. His own troupe flourished with extensive touring in the United States from 1932–1968. His partner and widow Amala Shankar continued to tour revivals and restagings of his work, including at the American Dance Festival in 1984. Through Shankar’s career, I will consider how social factors and personal ambitions create awkward relationships to orientalism’s manifestations. I use archival sources such as photographs, programs, publicity materials, featured essays, newspaper previews, reviews, and filmed dance footage (oh yeah, the dancing…) as a window into how Shankar navigated the diasporic U.S. landscape.

Then I will pair those events with my own artistic process for a new work, set to open in Los Angeles, CA in 2024. My project, entitled Reorient the Orient, is an eight-hour durational installation examining my own archive of 30 years of artmaking within the history of representations of South Asian performers on Western stages. The event is presented in a gallery format with intermittent performed events. One section of it, dubbed the Self-Orientalization Score is in direct conversation with Shankar’s legacy, although the whole work is in constant dialogue with multiple historical figures and theories including, but not limited to, multiculturalism, interculturalism, new multiculturalism, new interculturalism, Ruth St. Denis, Ted Shawn, La Meri, Uday Shankar, Ram Gopal, and of course me, myself, and I.

Many consider Uday Shankar to be the original modern dancer of India and there is a growing corpus on his legacy (

Banerji 1982;

Khokar 1983;

Erdman 1987;

Jeyasingh 1990;

Paine 2000;

Jost 2011;

Abrahams 2007;

Purkayastha 2014;

Khullar 2018;

Sarkar Munsi and Burridge 2011;

Sarkar Munsi 2022). To examine Shankar’s impact, specifically in a diasporic context, I think through the multiple forces—both internal and external—that framed how Shankar was viewed in the West. To illustrate those forces, below I place three excerpts of short biographies of Shankar that evidence three very different approaches to his legacy. One is from a performance brochure or ‘Playbill’ from 1934, the second from a recent biographical monograph by a scholar who extensively studied and performed his repertory, and the third is written by me to be used in conjunction with my project of reflection and reconsideration.

2. Three Uday Shankar Biographies

1. “It so happened that from his earliest childhood Master Uday showed signs of artistic proclivity and precocity. Perhaps the law of heredity had something to do with it. He was exceedingly fond of music; and nothing gave this child of artistic Udaypur more happiness than to dance in ecstasy to the tune of music played by master musicians in his home. The welcome news of the artistic precocity of Master Uday gradually reached the royal ears of the Maharaja; and the royal lover of the arts began to take a keen interest in the artistic development of the child of his dear friend and favorite companion”.

-Basanta Koomar Roy (1934) excerpt from performance program “S. Hurok Presents Uday Shan-kar and his Company of Hindu Dancers and Musicians”

2. “Uday Shankar (1900–1977) was born in Udaipur in India and travelled to England to study visual arts in the 1920s. His training at the Royal College of Arts, London, came to an end after he joined Anna Pavlova’s troupe at her request in 1923, against the wishes of his teacher, Sir William Rothenstein. After a short stint touring with Pavlova’s company, he was on his own again, trying to make a living while pursuing his interest in Indian dance. Not trained in any form of dance and yet wanting to create choreographies that would represent Indian history and culture, Shankar was at this time experimenting with available musicians and dancers, while performing as much as possible for patrons who were willing to offer him any chance to perform”.

3. Hailed as one of the founders of Indian Contemporary Dance, Uday Shankar was an avid experimentalist in his pedagogy (epitomized in his school in Almora from 1939–1943) and in his multi-media works (such as the film Kalpana (1948) and the piece Shankarscope (1970)). Shankar was part of the resurgence of Indian dance in the 1930s and onward. Much of his enormous success came in that decade as he toured, predominantly in Europe and the United States. In his early choreography one can see the desire to combine Indian conceptions of gesture, iconography, and theme alongside western conceptions of time and presentation. Many of his performance techniques such as short pieces, multiple costume changes, and staging design derived from within the western arts tradition. Shankar continued the mantle of orientalist performance styles developed by pioneers such as Ruth St. Denis and Ted Shawn. The biggest difference was that Shankar was from what is now India. Unlike his predecessors, he did not use brown makeup. Much of his press literature, in keeping with the times, emphasized his religious and social status as a Brahmin and a Hindu to the western audiences. Shanker presented a version of Indian dance that western audiences could digest by orientalizing himself in conjunction with the known.

-Lionel Popkin (2023—unpublished, until now)

These three versions of a biography show quite clearly the complex mix of hagiography, orientalism, economic necessity, self-promotion, mythologization, and criticality that have accompanied Shankar’s career with varying emphases depending on the situation, era, and purposes of how his work is being framed.

2 Even Shankar’s name was subject to reinterpretation and reframing by Western audiences. Early in his career, mostly in the 1930s, his name was often hyphenated in public announcements as Shan-kar. There are several stories to explain this, the most exciting being that without the hyphen, Shankar would be pronounced in a way that it came close to the Finnish word for penis. Erdman states that it was “to avoid confusion with a German expletive” (77). Abrahams thinks the hyphen was, “added to avoid sounding like a word for

cancre as he performed throughout Europe”, a word which means a dolt, or someone who is stupid (376). Whatever the truth was, the addition of the hyphen as a reality and a metaphor is significant. Shankar lived between worlds, making work that was viable on western stages and was also able to garner some success in India, but never really achieved the fame and recognition in his home country he felt he deserved as many considered his work inauthentic and pandering to western sensibilities, perhaps even colonial instead of Indian.

3 Regardless, Shankar was a savvy creator who was able to shift multiple times with the changing landscape of the field from his early more instinctual creations for Pavlova to his research in India with particular teachers (Kathakali in particular) and archeological sites (Ajanta and Ellora) that led to his later dances relating more consciously to the neo-classical revivalist forms of his era. Each biographical quote above, and the multiple frames within which he presented his work, projects varying degrees of orientalism onto Shankar’s work, and before I go any further, I should clarify that term in this context.

3. How Am I Using the Term ‘Orientalism’?

Edward Said’s seminal book

Orientalism (1979) brought his theoretical frame of east/west relations into focus within the larger context of cultural studies. At its root, ‘to orient’ means to face the east. The word itself presumes one is standing in the West and that there is another person or place to whom you relate standing over there somewhere. Said’s argument centers on the idea that the ‘West’ created the ‘East’ as a concept to bolster the West’s own sense of identity, superiority, and fantastical desires. The concept has proven quite resilient and adaptive with many scholars and artists building on Said’s initial dichotomous framing (

Bharucha 1993;

Appadurai 1996;

Bhabha 2004;

Ahmed 2006;

Mitra 2015, and others). For my purposes, I will focus on two scholars, Yutian Wong and Anne Anlin Cheng, who have looked specifically at how orientalism has manifested in diasporic Asian performance before turning its lens to Shankar’s work and then my own. Neither Wong nor Cheng use South Asian artists in their examples, and so in an orientalizing move of my own, by generalizing all of Asia, I am transferring their ideas from the local situations they have analyzed to the South Asian diasporic performance landscape.

Yutian Wong’s

Choreographing Asian America (

Wong 2010) looks at the legacy of the Vietnam War in performance practices with examples that range from experimental theater (the collective Club O’Noodles) to mainstream Broadway musicals (

Miss Saigon). Rather than submitting to the way, “Orientalism disappears Asian American bodies from the present by associating them within an imagined past that is both temporal and spatial” (13), Wong uncovers multiple ways in which Asian American discourse is and has been contemporizing performance practices including experimental representational practices, social dialogues, mapping techniques, and humor. Wong summarizes Said’s

Orientalism as, “a system of knowledge, a body of theory, and a practice that defined Europe and America through the study of difference. … Since the Orient is always already ‘‘ancient,’’ the relationship between modern-day ‘‘Orientals’’ and past cultures is one that is naturalized and distanced such that the ‘‘Oriental body’’ can be objectified and shelved. Orientalized culture can then be consumed as spiritual style” (12–13).

Applying Wong’s interpretation of Said to Shankar, we see a dancer evoking the whole of India and its 5000-year-old history on stage for Western eyes. Shankar’s own publicity materials emphasized his religious, spiritual, and cultural purity as a way of framing his own presence as historically contiguous, as opposed to contemporarily present. In her opening remarks at the 1984 American Dance Festival performances, Amala Shankar highlights this mode of representation, declaring, “We come from a country where there is no such a thing as modern. It is

(pause) we have

(pause) to

(pause) anything we think of we have to go back two or four thousand years” (

Shankar 1984). In 1984 we still see this conflation of orientalist tropes, framing India as not modern and eternally sourced in the ancient as a way to frame the dancing for the American audience. Despite those who claim Shankar as a pioneering contemporary artist, his mode of presenting his dances emphasized his relationship to India in a way that reaffirms his historical status. Even as he experimented and reconfigured material, he knew he had to fulfill what Wong defines as the Western audience’s “desire for seeing authentic bodies performing authentic culture [which] is also part of an Orientalist fantasy that easily substitutes costumes for actual people and cultural understanding” (219). Shankar’s own publicity materials echo this intent, declaring, that with “his holy temple dances dripping with the lore of centuries and the lushness of religious ritual, Shan-Kar overwhelms the Occidental senses with a primitive splendor which has made him an adored artist throughout Europe” (

New York Public Library 2022). More succinctly, Shankar himself states, “I dance the life of our gods and our people” (

New York Public Library 2022).

Anne Anlin Cheng’s book

Ornamentalism (

Cheng 2019) offers social and cultural analysis on our conceptions of authentic performers and how modernism’s minimalist aesthetic is part of a colonizing visual effort, but here I want to focus on her addition to the conversation of how external markers directly impact how we view other people. For Cheng, orientalism “relies on a decorative grammar” (5). Building on Said, Cheng offers the theory of ornamentalism, “as a conceptual framework for approaching a history of racialized person-making, not through biology but through synthetic inventions and ornamentations” (17). She distinguishes it from Said, stating, “Orientalism is a critique, ornamentalism a theory of being” (18). For her, “ornamentalism describes the peculiar processes (legally, materially, imaginatively) whereby personhood is named or conceived through ornamental gestures, which speak through the minute, the sartorial, the prosthetic, and the decorative” (17–18).

Cheng’s discussion of the film star Anna May Wong (1905–1961), a contemporary of Shankar’s, is useful to help understand how the ornamentation inherent in the markers of Orientalism, what Cheng calls, “the excessive sartorial elegance of Orientalism” (65), creates a persona that is less about how that person exists in the moment and more how the semiotic signifiers that accompany that human being overwhelm how they are perceived. In theoretical discourse, Cheng writes, “it is precisely at the interface between ontology and objectness that we are most compelled to confront the limits of the politics of personhood” (156). For Shankar, this manifests in multiple ways, two of which I will mention here. First, the publicity stills for his tours of America featured photos of ‘authentic’ Indian musical instruments and live music was an important part of the performances. Uday Shankar’s younger brother, the sitar superstar Ravi Shankar, had his first touring experiences as a member of Uday’s troupe. Those photographs served to familiarize and appease audiences to the ‘exotic’ sounds they would experience in the performance. Second, the publicity materials also sought to distance Shankar and his troupe from negative conceptions of bearers of melanin. Brochures from a 1938 engagement state, “All members of the company are high caste Brahmins and Hindus except Simkie. She was born in France, but has adopted the Hindu faith since her association with Shan-Kar’s company and, accordingly, wears the red mark on her forehead” (

New York Public Library 2022). Upper caste inclusion, and the “red mark” to authenticate the one European in the troupe, both serve to exoticize the performers while at the same time neutralize any threat they may pose to the American (white) viewing public.

Now that we have a sense of how orientalism is operating in this context, the term self-orientalization needs to be clarified. I am using the term to describe the action of reinforcing the stereotypes and tropes of orientalism by orientalized subjects themselves. From a performative standpoint, this could mean creating stage imagery that capitalizes on the tropes of authentic, traditional, ancient, and unchanged aesthetics. There are often very good reasons to do this. All performance opportunities are not open to all people. Despite her frequently questionable Orientalist guises, Ruth St. Denis (one of the grandmothers of American concert dance) had a set of limited options as a white female solo performer when she started her career in 1906.

4 Similarly, Shankar, who lived in Paris as a struggling performer in the late 1920s after he left Pavlova’s care, wanted to dance and make dances and the options available to him at that time in Europe were what they were.

Self-orientalization can also be unintentional, but still very real. As a marked and othered body (and I use body here specifically because Shankar and others like him were not necessarily always seen as a person), they needed to fulfill a fantasy of who they might be for their audience to show up. In her discussion of the African-American performer Josephine Baker’s success in Paris in the early 20th Century,

Cheng (

2011) writes what could easily be noted of Shankar, “The interesting question is not one of Baker’s agency (indeed, the question of her self-construction or self-representation is complex by nature, given her professional obligations and the social world in which she succeeds), but how the terms of agency and performance must be nuanced in a context where the question of consent is seriously compromised” (42).

5 Cheng’s fulsome discussion of Baker is complex and includes many important observations about how her audience jostled between racial and primitivistic frames. I raise it here not to conflate Baker’s experience with Shankar’s, but rather to draw a connection where they overlap and in how they each contended with their versions of self-representation within Europe of their era. To build on that thought, I contend that self-orientalization is as pervasive as it is insidious. The feedback loop for a successful performer in the culturally marked (non-White) genre of dance (as it is defined by the mainstream) is dependent on their fulfillment of the white gaze and its desire to witness a constructed novelty while simultaneously believing in its authenticity.

4. Actually Analyzing Shankar’s Dances

Very few of Shankar’s performances exist on film. His experimental film

Kalpana (

Shankar 1948) contains some of his early work couched within the semi-autobiographical plot of an artist struggling to express his vision and employ education as a means to uplift the masses.

Khokar (

1983);

Purkayastha (

2014); and

Sarkar Munsi (

2022) have all offered insight and analysis on the dance mechanique structures, inventive vocabulary, and innovative dance for camera techniques within this groundbreaking film which dovetails neatly with the neo-classical practices of many artists who came of age within India’s political struggle for independence from colonial Britain, achieved in 1947, the year before

Kalpana was released.

As I have mentioned, Amala Shankar, who ran the Uday Shankar India Culture Centre, Kolkata, from 1965–2015, a school based on the training techniques and repertory developed by Uday Shankar, toured to the American Dance Festival in 1984. The program contained nine dances and one musical interlude. Of the nine dances, one, choreographed by Amala Shankar, was titled Homage and was a collage of multiple works from her late husband’s repertory. Another piece, Apsara (1978), was choreographed by Uday and Amala’s daughter, Mamta Shankar. The other seven works are all attributed to Uday Shankar, with one, Harmony, from 1941 and all the rest (six if you are counting) dating between 1930–1935. As such, the bulk of the repertoire from the performance (six out of nine) gives us a strong insight into the choreographic methods Uday Shankar utilized early in his career that launched him into international recognition. The dances are a treasure trove of information on how Shankar expressed his own artistic interests when he blossomed in the 1930s, but also how he navigated the expectations of the Western audience, utilizing the performance norms known to those audiences, and judiciously employing ornamental and oriental markers to identify his work with Indian heritage.

When I watch the dances, I see three main categories of this action within the dances: (1) how Shankar crafted movements and gestures; (2) how he used costumes and props to signal meaning; and (3) his use of thematic and structural devices in ways that read as exotic and ‘oriental’ to his audience. These expectations and markers of orientalism were already associated with Indian dance within the circuits Shankar’s works toured. The venues had been primed by artists such as Ruth St. Denis, Ted Shawn, their joint company Denishawn (which folded in 1932 just as Shankar’s group emerged on the international stage), and even by Anna Pavlova’s tours with Shankar in the 1920s. I will first analyze one of Shankar’s dances before I make a list of claims regarding the techniques and orientalizing accommodations Shankar employed as his work unfolded on stage.

The year is 1984. We are in Raleigh, North Carolina. The American Dance Festival is in full swing, and this weekend’s concert offers us a glimpse into Indian culture and dance. We are about two-thirds of the way through the evening. We have witnessed stories of the gods, subtle weight shifts, undulating arms, a bare-chested hunting display, and even a musical interlude. The pieces have been short, usually between three and eight minutes in length. After each one, the audience has dutifully clapped, although often before the music has ended.

Or maybe the year is 2022. We are in New York City at the Performing Arts branch of the Public Library watching a VHS tape, pressing pause to take notes, rewinding and rewatching bits of details. In one of my coffee breaks I remember sitting in the same theater in North Carolina in 1992 watching a Kathak performance by Birju Maharajji and his group from New Delhi. In 1989 I lived in Delhi and took daily classes from him. Some of my classmates are in the show. I try and process how that work was received by those around me (although that is for another essay), and I remember the awkward backstage reunion after the performance. But I digress. Back to 2022, the VHS tape, and the viewing room to watch a 1984 revival of the 1935 piece ‘Harvest’, the eighth piece in the program.

Harvest (1935) is a 5-min work for nine dancers with three live musicians at the 1984 performance. In the piece, the men and women (and they are definitively cis-gendered in costume and action) reenact a joyful post-harvest village ceremony. They mime sowing, reaping, threshing, husking, and sifting alongside other actions of the harvest. Throughout the piece, the dancers execute a pulse, with all the choreography emphasizing symmetry and repetition. They enter in a line, feet scuffling, arms scooping, that quickly guides them into a full circle around the center of the stage. They pause their locomotion with a series of side-to-side hip thrusts that accompany a set of arm flicks to define quadrants around their bodies. Soon they scatter into groups of three and go through many of the gestures listed above, enacting with fondness their successful agricultural achievement. As the piece concludes, three women clump in the center, stamping out a rhythm, and multiple heterosexual pairs skip around them vocalizing yips of joy before they all once again form a circle and scoot their way off-stage in the same direction from where they entered. The audience responds with more enthusiasm than they have to the previous numbers. The piece is more energetic than some of the more ethereal pieces, and perhaps the boisterous sounds made by the performers toward the end of the piece gave the audience more permission to yelp in approval as well as applaud. Still, they clap after the dancers exit, but before the music ends, aurally drowning out the dance’s musical conclusion, privileging its visual summation over the conclusion of all the elements.

The five minutes of

Harvest are a collision of worlds and performative interests that encapsulate many of the crosscurrents within the full evening. Lists are inherently incomplete, but they do help to visualize our insights. What follows are a series of items gleaned from viewing the full two hours of the above video and researching Shankar’s oeuvre. I distinguish the lists into what I see as the ‘oriental’ elements and what I see as the ‘occidental’ elements in Shankar’s choreographic stagings. Orientalism as a received construct relies on a bifurcation; on the east and west as distinct categories. This dichotomy is inarguably constructed, and the reality is far more complex than a simple binary. The relationship between Shankar’s, indeed anyone’s, influences is in reality far more multi-faceted and complex than a simple dualistic reading. My lists are not meant to permanently bifurcate those influences, rather they help me lay out the information to then be further conflated and confused. I offer these lists as a way to parse the elements and see them in order to grapple with their interconnectivity.

6The movements and gestures that reoccur within these dances from the early 1930s that most closely identify them as ‘oriental’ are:

Mimetic gestures that could be and sometimes are semiotic

The stomping of feet to create percussive sounds

Arm gestures of undulation and more undulation

The side-to-side movement of the head by isolating the neck

The sculptural pose of three bends in the body known as

tribhanga7Placing the hands as fists on one’s hips with the elbows flared out

A mode of locomotion in which the weight moves down, up, down, down with the last down slamming into the earth.

The costumes and props that reoccur within these dances from the early 1930s that most closely identify them as ‘oriental’ are:

The use of the head dress as ornament

The topless men with jewels across their chests

The bright color palette in the costumes

The flowing fabric of the women’s costumes

The use of the sword in multiple dances as a symbol of rural life

The thematic and structural devices that reoccur within these dances from the early 1930s that most closely identify them as ‘oriental’ are:

Hindu themes, particularly stories of the gods

Narratives of village life in contrast to urban society

The use of live music with ‘authentic’ Indian instruments

Shankar also crafted his works using multiple staging techniques often considered to be stylistically Western. These techniques are not exclusively western, but Shankar’s audience in the West recognized them from the existing concert dance of the early 20th century and the vaudeville circuit of the era. Shankar was able to use these framing devices to reassure the audience and to give them some of what they knew in a performance context, while at the same time capitalizing on the novel and the exotic of his repertoire as listed above. His own publicity for his later tours declares that he, “has devoted his life to the task of acquainting the world with the mysterious and beautiful culture of India,” and that his main, “achievement lies in developing the highest standards of Indian arts with the proper adjustment for our [Western] theatrical stages” (

New York Public Library 2022).

These staging devices, many of which were learned in Shankar’s early visual arts training, all helped audiences see Shankar’s work as belonging on the occidental Western stages. He employed techniques such as:

Shifting group formations modeled primarily around Euclidean geometry (circles, lines, triangles)

Short pieces in the 3–7-min range

Utilizing entrances and exits as an energetic device

Multiple references to the cardinal points on the stage

Varying positions and levels in the composition in a pictorial fashion

Seeing pieces of material on their own, then combining them to create new juxtapositions

Changing of costumes for each number

Echoing of gestures within the stage composition

Using the distinction of foreground and background for emphasis

Symmetrical dancing structures and sequences

The idea of introducing Western audiences to authentic ‘Indian’ art was present from Shankar’s earliest tours. One brochure proclaimed that, “Prior to his initial tours in the Western World few have had the opportunity to sample the rich, exotic, subtle and magnificent treasury of Hindu dance and music” (

New York Public Library 2022). Also present was Shankar’s desire to maintain the connection to the vast tradition of orientalist fantasy while also being seen as someone who belonged on the stages of his era.

8 Again, I quote from a performance brochure vowing that Shankar, “will bring a program reflecting Indian culture from its most ancient to its most contemporary aspects. The three-thousand-year-old vocabulary of Hindu dance is still employed, with its use of the hands, fingers, lips, brows, neck and head as well as the body. But the dances themselves have been related to the passage of time and the succession of changing events that make up life” (

New York Public Library 2022). In Shankar’s own publicity we see the employment of a list of markers, gestures, and particular body parts as part of what it means to present a dance as ‘Indian’ while still translating it to the contemporary stage.

Shankar existed between these realms, with a hyphenated status, sourcing one set of practices while soliciting approval from another. There is little doubt that in the 1940s and 1950s he returned to India and created multiple influential projects. The Uday Shankar India Culture Centre in Almora (1939–1943) was a radical approach to dance training.

9 As a film,

Kalpana (

Shankar 1948) is held in great esteem as a landmark in dance for camera and early cinema, as filmmaker Martin Scorsese’s recent efforts to restore and digitize the film evidence.

10 Shankar’s dances, and his own publicity materials reveal a great deal of how he contended with the multiple processes of making his work both accessible and exotic, contemporary and traditional, relatable and authentic for multiple decades in a fast-changing world.

In her influential article Getting off the Orient Express (1990), the British choreographer Shobhana Jeyasingh wrote that, in his day, Shankar, “was seen as ‘the authentic voice of India speaking directly and immediately to us from 5000 centuries of civilization” (1). She goes on to criticize artists like Shankar for utilizing stereotypes of South Asia, emphasizing its ‘Oriental’ capacity to represent an ancient aesthetic with allure and wisdom while simultaneously emphasizing Western formal structures over South Asian forms of dance. Jeyasingh expressed this frustration in 1990, 30–60 years from Shankar’s international tours. I now ask, are these historical forces from the 1930s and 1960s, ranging from 60–90 years old, still with us? Of course, they are.

5. Flickering Signifiers: Reorient the Orient11

December 2022. An old friend/collaborator is visiting Los Angeles and is at my studio to help try out a few movement scores. For over 30 years I have had the pleasure of watching her dance, improvise, and create with me. She is helping me with the language, the range of possibilities, determining which words create which limits and how. We try the scores for each other, dancing our thoughts, and I realize her whiteness is unavoidable in these topics. There is a Ruth St. Denis vibe, however unintentional, to her dancing these scores. I have to decide if I want that idea, of white appropriation, to be front and center in the piece. How important is it that the performers identify as an orientalized subject for the piece to do what I need it to do?

As I have mentioned, my new project, Reorient the Orient is a durational (8 h long) and multimodal (objects, printed matter, audio guides, reading lists, and scored activities) event. The project is designed to unpack a history of inter-culturalism and orientalism within my own archive of nearly 30 years of dance-making and place it within the context of the history of presentations of the South Asian diaspora within post-modernism in the U.S. The setting for the work includes at least 5 rugs, about 6 videos, large stacks of archival matter, a huge purple sleeping bag suit, an elephant (not a real one, that would be cruel), and approximately 217 neon yellow wiffle balls. The event also has 12 kinetic scores, performed live at various times throughout the space. The danced scores vary tremendously. Some are quite precise with minute directions and minimal interpretive room. Others are wide-ranging with evocative prompts and spacious parameters. Some approach distant epochs in history, others contend with recent insights in the performance field. In this essay I want to focus on one score in particular. It goes by two names; the Self-Orientalization Score and the Stool Score. The first name denotes its conceptual basis, the second refers to the prop on which the dancer sits while performing.

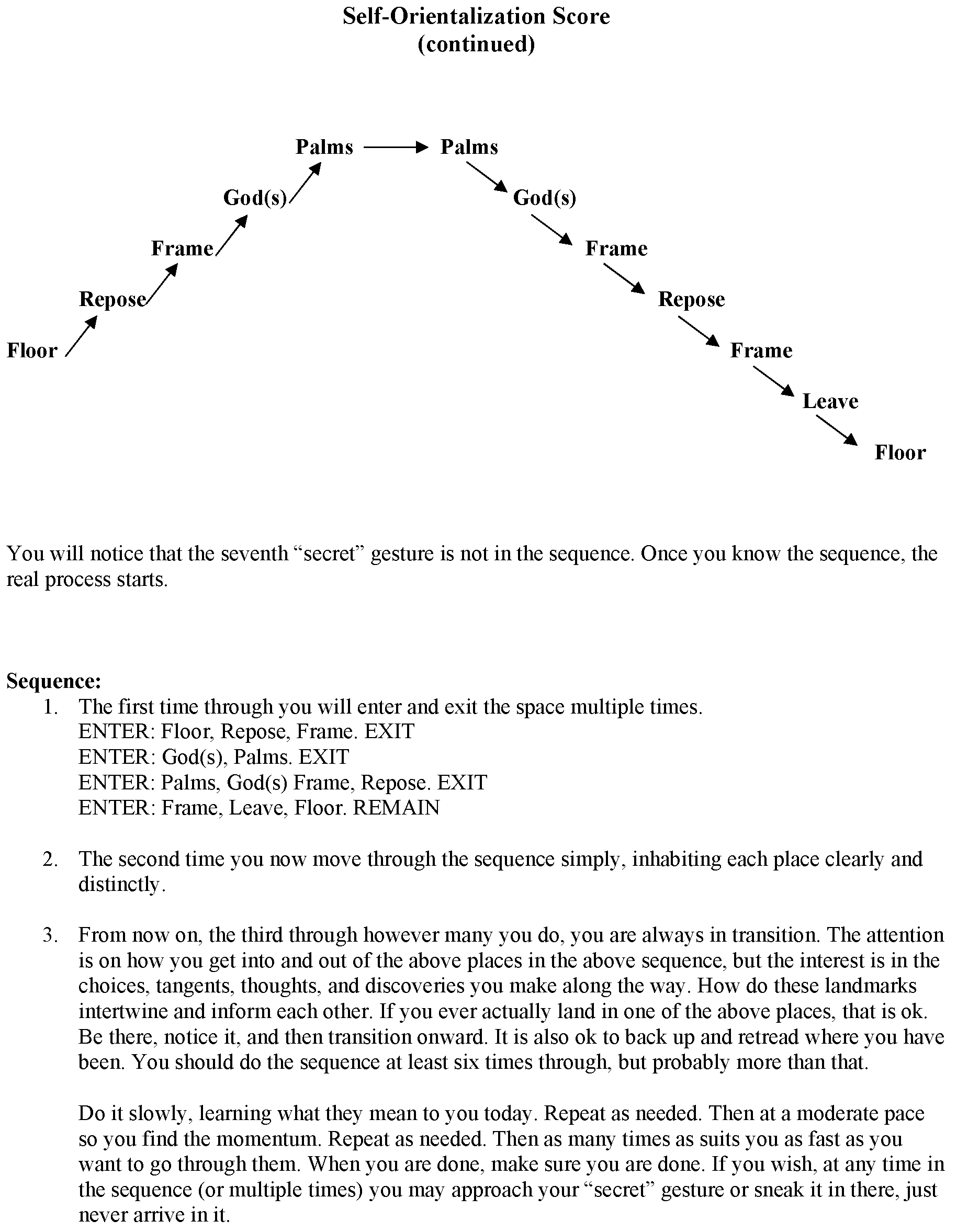

The movement score considers actions that occur when we take on others’ conception of ourselves and works through those modes of presentation in a structure of gestures and transitions that repeat and evolve through time. The score is set in a nook, with a TV and a stool to sit on (

Figure 1). On the TV is a scroll of sentences that are variations on over-eager greetings such as, “I am delighted to be here this evening,” and “It is an enormous pleasure to be with you here”. The stool is placed in front of the TV, so when a person is on the stool, the words float above and behind their head. The setup is placed in a nook of the theater/gallery, perhaps in the lobby, and as part of the preparations for the show, versions of the score are filmed in that nook that will be shown on the TV during the performance, interspersed with the scrolling text. The visual repetition of the person performing the score live along with the video version, summons ideas of present tense (the live version) and historical enactments (the prerecorded dance) and how they overlap in multiple ways in this score. Reshooting the section in each setting also reinforces the immediacy of the dance. Wherever you are watching it, this happened here.

In the rehearsal process of the whole work, the performers are sent the twelve scores as a package. They then create their response to the pages they received. Next in the process, we all meet, share our versions of the score, respond to each other’s versions, and redraft the responses with communal agreements and divergences. Each person will have their own version of the twelve dances, but with enough connectivity that the audience should be able to relate each version to each other. Below (

Figure 2 and

Figure 3) is a draft version of the

Self-Orientalization Score:

The above dancing score has many elements to it that respond to different aspects of historical and contemporary approaches to moving in modes linked to South Asia. The combination of self-generated and archivally sourced vocabulary is essential to the conversation between past influences and present entanglements which pervade this structure. The entrances and exits in the early stages of the dance are also important. They ask the performer to commit and recommit to the conceptual and actual space the dance inhabits. Each time the performer walks back to the stool, and later each time they almost leave (number six), they are agreeing to be part of the conversation about how and why we self-orientalize. These two elements (the vocabulary and the entrances) are visible to the audience and play out in front of them. The audience sees the hand gestures; they see the person walking in and out. Perhaps less evident is how the sequence converses with other structuring tools. The relationship of the five ‘ascending’ gestures and the seven ‘descending’ gestures is a direct transposition from the classical North Indian (Hindustani) Raag Bhairav. A morning Raag, often used to conclude a Kathak performance (they used to go all night and dawn was the moment of conclusion), Bhairav contains hope and contemplation in it. This structural transposition is a crucial part of thinking through how a diasporic mindset can influence cultural dialogue and how certain markers (such as the song cycles of raags) can or should be manifest in current contemplations. Some of the differences are highly visible markers, others are more subterranean, leading to a non-Western mode of laying out material. This is in distinction from the more ornamental approach with the visible source and vocabulary of the material being South Asian, but the structuring mechanisms being Western in the way Shankar’s, for example, were.

My process has a three-decade long history of relating to classical Hindustani music. A very early piece of mine,

Solos, 1 Trio (1990), was set to original music by the renowned singer Shobha Mudgal. Sixteen years later, I made the evening-length work

Miniature Fantasies (2006) that investigated how specific Ragamala Paintings (miniatures created to evoke the tone and mood of a raga) would translate into the time-based and figurative medium of dance.

12 In the context of

Reorient the Orient (2024), the looping structure of the raag lends a compositional shape to the dancing, influencing the way the body approaches a gesture, slides toward and away from it, retreats to previous thoughts before perhaps slicing through to the next idea.

The Self-Orientalization Score lays out a sequence (a scale), and then dives into it to explore how to be seen and be present whilst contending with the personal and historical poses that comprise the elements at hand. The stool, the TV, and the nook all create very different meanings which also aggregate into the dance. The stool allows the performer to rotate 360 degrees within the score, creating a rounded focus and dimensionality. The TV is decidedly two-dimensional, with its ingratiating text, and then unsettles that flatness with references to a conceptual recurrence through the pre-recorded versions. The nook, with its recognizability to the actual space, speaks to the present tense, an event that may be in an archive one day, but today it is not.

The time has come to ask an important question or three.

Why make a section of a dance on self-orientalism?

What is it about this concept that draws me, personally and professionally, into its quagmire?

When have I self-orientalized either consciously or unconsciously, in my life and in my work?

In the Oxford Handbook on Indian Dance (forthcoming 2024) I tell my story and development as an artist in an article entitled “On the Edges of Diaspora: Second-Generational Mixed Thoughts”. Much of the why asked in the above questions is contained in those pages, but here are a few highlights and additions:

Winter 2015. I have just finished touring my evening-length work ‘Ruth Doesn’t Live Here Anymore’ which undertakes an archival séance and wrestling match with the legacy of Orientalist performer extraordinaire Ruth St. Denis. The piece was well-funded and toured quite a lot by my standards. In the piece I include my mother’s saris, colorful swaths of fabric, and many other identifiable markers of Orientalism. My intention was a critique. For the next piece, I evacuated all those recognizable markers and made a domestic drama set within, around, and on top of an inflatable living room set. The piece barely toured. Maybe it wasn’t that good? Maybe those markers in ‘Ruth’ were seen as identifiable enough to program me, but not the other way around? Maybe the market needs the markers more than I knew or hoped it did.

December 2021. A café in Los Angeles. Another South Asian choreographer has reached out to me and asked to meet for coffee and a chat. I am looking forward to it. We meet. I am dressed in a hoodie, jeans, and a t-shirt. My usual at this stage in my life. She is dressed in a salwar-kameez with a chunni. Her usual, I presume, but maybe not. Chunni means scarf. As we order the barista comments on how beautiful her outfit is. She says thank you. As we carry our drinks to the back patio another customer tells her how “gorgeous” her scarf is. She says thank you. We sit down, lock eyes, and simultaneously whisper, “White people are so annoying”. Then we laugh. We have only known each other for five minutes.

January 1990. I have flown home to the States after living in Delhi and studying a classical form quite intensively for six months. I show up in Ohio to choreograph the musical Jesus Christ Superstar for a production at my college. I have absolutely no clue how or why to transfer the information I learned in Delhi to this group of performers.

A direct quote from the OUP article referenced above: “On my first day in Birju Maharaj’s class in 1989 in New Delhi, the other students were snickering quite a bit. I was holding my spine incorrectly, over-rotating my torso, and my focus was too peripheral. The diasporic privilege that put me in that room was as blatant as my naïve representation of the ingrained codes and bodily positions that my classmates, all of whom had undergone years of training in Kathak and extensive auditions just to get into that room, understood in their pores. They rightfully pointed this out to me. By the end of my time in the class, I was much better at delivering the accepted formal requirements. I had practiced rigorously. Somewhere in the Doordarshan archives, I can be seen in a row of dancers backing up the soloists for an All-India television special.13 Obedient bodies can be reshaped”.

This essay has toggled between multiple modes of knowledge: cited scholarly theories, VHS tapes, italicized remembrances, choreographic analysis, a few shards of narrative, and archivally sourced records of publicity materials and media reactions. Missing from my modes of writing has been the manifesto. Below I offer two options. First, I again turn to Wong, transferring her thoughts on Vietnamese legacies to mine, with the following paragraph. Then I close this section with a few thoughts of my own.

“The invisibility of orientalism in American modern and postmodern dance history poses a problem for Asian American choreographers. Asian Americans are not viewed as abstract bodies engaging in artistic experiments. Instead, they are seen through an Orientalist double vision in which their bodily Asian-ness must remain distanced from the modern and postmodern dance vocabularies they are using. American dance aesthetics must be wholly Westernized in order to maintain a binary between the West as continuous renewal and the East as a repository of traditional source material. While white Western choreographers can mask appropriation through accounts of inspiration, Asian American performance aesthetics are stereotyped as attempts to fuse or blend incompatible Eastern and Western sensibilities. The fact that American modern and postmodern dance are already Asian American is denied, which leads to an Orientalist reading of Asian American choreography as a reflection of deeply rooted, biological, racial truths”.

(51–52)

Manifesto for a self-orientalization proposition on how to find room in the room that leaves fewer options than they appear to provide:

-

Secret—Keep at least one.

|

-

Leave—Don’t forget to leave or ask people to leave when it is necessary. It ain’t personal. Just necessary.

|

-

Palms—Greet people. Be clear. Greet yourself. Be clear to yourself.

|

-

God(s)—Fuck the divine. The construction of mythologies is designed to manipulate. Hone your awareness and process, process, process.

|

-

Frame—They are watching. But remember you can look right back at them.

|

-

Repose—Don’t forget to rest and reflect. Being exhausted and hasty stinks.

|

-

Floor—Start from where you are. Figure out where you are. Be honest.

|

6. My ‘Authentic’ Conclusions

I am in New Orleans, or maybe Tulsa. Around 2015, maybe 2016. The performance convention is going well. A well-meaning and supportive presenter suggests I change my middle name to something more ‘Indian’ sounding so I can get more work. My response is multi-faceted. After all, they are right.

I conclude by wading into a term that has pervaded this entire article and indeed the history of cultural exchange. What does it mean to be authentic? Up to now, on these pages, I have used that word, or its variants, 16 times, including in the header to this section and the last sentence. The notion of authenticity is fraught with power imbalances. When is the moment that something authentic forms and who decides what that is? How much does the viewer’s experience and knowledge impact how authentic something is? What happens when an expert is using the term for their own purposes to coalesce resources and reputation? I return to Wong and Cheng to partially answer these questions. Wong clearly states her point of view that, “the desire for seeing authentic bodies performing authentic culture is also part of an Orientalist fantasy that easily substitutes costumes for actual people and cultural understanding” (219). The conflation of the authentic with external markers such as costumes, jewelry, and other props is endemic to the genre of Orientalist practices. Cheng writes, “This call for authenticity, social visibility, and self-making is, of course, enormously appealing … But the history of the delineation of racialized bodies that we have been studying here suggests that something more fraught is at stake here than notions of authenticity” (169). More fraught indeed. As part of her discussion of Josephine Baker and how she represented her intersectionality, Cheng adds, “The only ‘authentic’ thing we can locate in this performance-within-performance is the virtuosity of movement itself. And virtuosity, instead of signaling a language of universality, speaks instead in the language of fragmentation and hybridity. Baker’s moving body gives us neither harmony nor originality but citation and disarticulation” (159–160).

I am always dubious when the word virtuosity gets used. How are we determining what is virtuosic? What techniques of study are we taking for granted and which are we hailing as beyond the norm? Are we counting how many turns one can do as a sign of expertise, and if so, are we discussing turns on the balls of the feet as one does in ballet or on the heels as one does in Kathak? Still, Cheng’s point regarding the hybridity and citational aspects of what we can locate through the ‘performance-within-performance’ of self-orientalization is helpful. Shankar existed between worlds, sourcing India while succeeding in the West. Unlike me, he was born and raised in India, moving to London as a young adult before finding his pathway as a dancer and performer. I was born and raised in Indiana and started studying dance as a young adult in college before finding my way into a dance career. Shankar came of age as an artist in the 1920s and 1930s, a time when India was undergoing a fierce political upheaval for colonial independence and Indian dance was undergoing a viscous cleansing and rebranding of its nationalist forms. Indian dance was coalescing around the new nation’s cultural currency long before Benedict Anderson’s Reagan-era observations of nationalism as a motivating principle for identity, community, and action (

Anderson 1983). As an artist, I came of age in the post-Reagan coalescence of neo-Liberalism and identity politics, and emerged to continuously question nationalism, religion, and just about any other identitarian way of thinking.

Different eras call for different solutions. There is something to be said for believing that each era was doing the best it could. I do not set up the comparison here between Shankar and myself as a way of lionizing myself and/or denigrating him. Much can be learned from the achievements and foibles of the past. The greatest compliment I could receive would be for an artist in 2084 (if the earth is still habitable for humans in 60 years) to write about how my score on the stool was an example of how rudimentary the early 21st century’s understanding of self-orientalization was. They might even make a joke about how it was a stool sample. Or comment on how quaint it was that we were still using the term ‘Oriental’ at all. If that mythic, idealized future artist/thinker is seeing and saying that, it means progress has been made.