Abstract

The architecture of the Soviet Avant-garde represents an important part in the history of the world’s architecture. It has become and continues to be a subject of interest for numerous researchers all over the world since the second half of the 20th century. However, was it well-known before, and who was the first to spread that knowledge? This article aims to study the critical legacy of Italian artist and architect Vinicio Paladini and his role as the first disseminator of the ideas of Soviet Avant-garde architecture in Italy in the 1920s with his article “Lo spirito moderno e la nuova architettura nell’U.R.S.S.” This article provides an in-depth analysis of chosen projects and architects as well as attribution of illustrative material alongside the archival research. It establishes the origins of Paladini’s interest in the art and architecture of the USSR, surfaces his perception of the characteristics of Soviet architecture, and highlights the importance of his role in promoting Russian modernism in Italy.

1. Introduction

The history of political and cultural relations between Italy and USSR in the early 1920s and 1930s, despite certain contradictions, represents a profound problem that continues to be of major interest for different studies. The events of the October Revolution of 1917 attracted all the attention from the West. From the moment of its official establishment on 30 December 1922, the USSR was seen as a political, economic and social experiment that manifests specifically in culture. Art and, more importantly, architecture, the latter to be seen as a result of the construction of a new state, became instantly known to Western critics, artists, architects. Connected to these processes, the Avant-garde started by being tightly associated to bolshevism, which brings to the polemics in Italian cultural scene in the early 1920s–1930s.

Italian modernist architects were intrigued by the achievements of Soviet constructivism. At that time, the main resource of information about contemporary architectural processes in the USSR were the French and German professional presses, which Italian architects were subscribed to. The general critique of that period regarding Soviet architecture was optimistic (Vyazemtseva and Pistorius 2018). Even the “official” outlets were choosing to put aside political contradictions and give a fair attention to it. New social types of buildings such as workers’ club, mass theatres, and house-communes were a curiosity to the foreign colleagues.

Among different authors emerges Russian-born Italian critic Vinicio Paladini (1902–1971). A futurist artist, adjacent to the communist political movement, he studied closely the new spirit of art and architecture in the USSR and connected to the socialist revolution. His role in the artistic and theoretic scene in Italy in the early 1920s–1930s is yet to be studied. Being active between politics and art, he was overshadowed by other prominent art and architecture critics of that time as well as his artist colleagues, whose work gained more attention. As an author of numerous theoretic works, Paladini is usually seen as a theoretic and a visual arts critic, while his participation in the architectural scene is overlooked (Carpi 1981; Lista 1988). Researchers tend to study his work on Soviet photomontage and cinematography, essential parts of constructivism (Brungardt 2015). What is usually left out and is seen as a main goal for the present article is Paladini’s role as the first and the most active researcher and disseminator of the Soviet architecture ideas in Italy in that period. Moreover, it can be argued that Vinicio Paladini was a predecessor for Italian scholars, such as Vieri Quilici (Quilici 1969) or Vittorio De Feo (De Feo 1963), who from the 1960s began their unprecedented research of the Soviet architectural Avant-garde.

2. Vinicio Paladini—The First Investigator of Soviet Constructivism in Italy

Vinicio Paladini is a rather interesting figure, from some point of view defining the destiny of leftist art in terms of establishing a totalitarian regime.

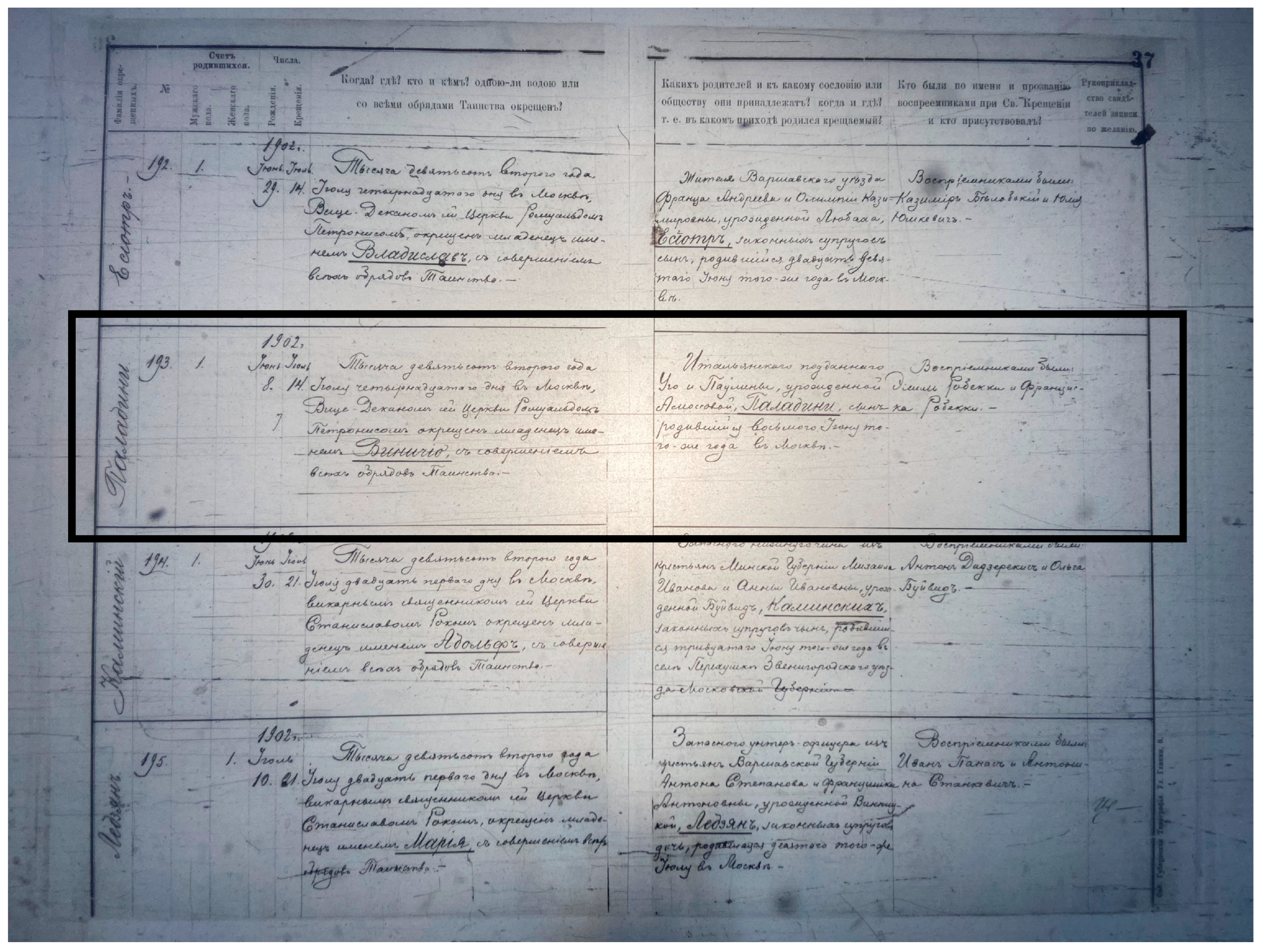

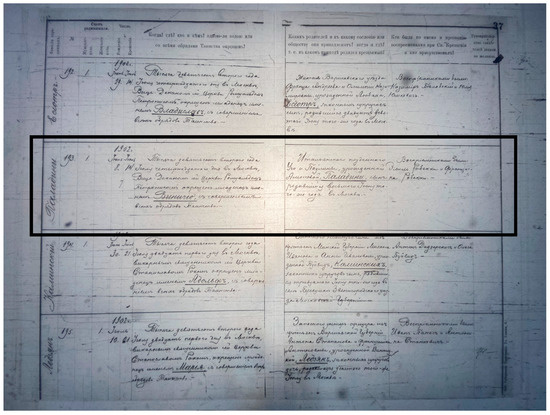

The Russian origins of Vinicio Paladini have never been a big secret. In fact, in the early 1920s, he was participating in different exhibitions signing as a “Russian” artist (Baldacci 2006), while in the annual alumni book of the Superior School of Architecture in Rome in his file is noted “da Mosca (Russia)1” (Annuario della Regia Scuola di Architettura in Roma 1926). The first author to mention the exact date of his birth is Giovanni Lista in his monographic work “Dal futurismo all’immaginismo. Vinicio Paladini” (Lista 1988). Although the fact of his Russian origins was constantly brought to attention, there was always lack of documental confirmation of his birth up until this article. In the course of research, the author was able to locate the parish register of the Roman Catholic Church of Saint Peter and Paul in Moscow State Central Archive (Figure 1). This document, published for the first time, states the precise date of birth of Vinicio Paladini (8 June 1902) as well as the date of his baptism (14 June 1902), the note on his parents Ugo Paladini and Paulina Amosov and even on his godparents, Emile and Francesca Robecchi. Some researchers suggest that Paladini’s Russian origins are the main reason for his special interest in Russian art (Lista 1988). However, by studying his diverse activities, not lacking the impact of political views, it is becoming clear that there is more to these relations than the fact of being born in Moscow.

Figure 1.

Note on birth and baptizing of Vinicio Paladini. Moscow State Central Archive. F. 609, Roman Catholic Church of Saint Peter and Paul, Moscow, cart. 2, d. 86.

What would be the right way to describe Vinicio Paladini and his activity? He was more than an artist or an architect. At first, he became a part of the art gallery “Casa d’arte Bragaglia” and worked as a theater designer at the Anton Giulio Bragaglia’s experimental Theater, where he became acquaintances with futurist artists such as Giacomo Balla. At the same time, Paladini was occupied with creating the mechanic art by experimenting with painting and photomontage. In the second half of the 1920s, Paladini became one of the founders of imaginist art. Being interested in paintings and theater, he also worked a lot with photomontage as propagandic means and studied the phenomenon of “documental realism”. At the same time, he wrote numerous articles on almost every kind of art that sparked his interest. Amongst them there is a unique brochure, dedicated entirely to the Soviet pavilion during 14th Venice Biennale in 1924 (Paladini 1925).

Supposedly, Paladini’s first interest in architecture can be connected to his years at Bragaglia’s experimental Theater, where he met futurist architect Virgilio Marchi. Later on, in 1925, Paladini enters the Superior School of Architecture in Rome. In the same year happens his first encounter with Soviet architecture when Paladini visits the International Exhibition of Modern Decorative and Industrial Arts in Paris (Lista 1988), for which architect Konstantin Melnikov constructed the world-famous Soviet Pavilion. Paladini’s position in the political and cultural context in Italy in the early 1920s as well as his views bring to understanding his constant interest in the development of contemporary Soviet art and architecture.

In fact, Paladini’s contacts with protagonists of the Soviet artistic scene were not limited to one episodic event: it is with absolute certainty that he visited Moscow at least two times. Even though there is no legal evidence in the archives of Russian and Italian Ministries of Foreign Affairs, such as travel documents or visas, there are other pieces of information proving these visits. Considering Paladini’s wide spectrum of interests, it is not surprising that this evidence relates to his passion for cinema and architecture. From the research of Christina Brungardt, it is known that in late autumn of 1927, Paladini was in Moscow, where he was studying the specifics of Soviet cinematography while visiting a film production studio “Sovkino”. In November 1927 in “Cinematografo” was published his first article sent from Moscow, while in April 1928 in “Cinemalia” were published his latest notes from his travel diary, dated and sent from Moscow to Rome (Brungardt 2015). Hence, it is possible that Vinicio Paladini has spent approximately six months in Russia, where, once welcomed to the artistic community, he could have met the protagonists of the Soviet Avant-garde in its every sphere. His second visit to Moscow finds its evidence once again in Paladini’s articles, published in “Il Tevere” in autumn of 1934 (Paladini 1934a, 1934b). This time, he describes the overall state of the USSR, its achievements, and the capacity of the architecture to present the principles of communist society.

2.1. The First Italian Article on Soviet Avant-Garde Architecture

One of Paladini’s most significant works as a critic and, most importantly, disseminator of Soviet constructivist architecture is the above-mentioned article “Lo spirito moderno e la nuova architettura nell’U.R.S.S.”, published in “Rassegna di architettura” on 15 March 1929.

The journal “Rassegna di architettura” had its own role among the professional Italian press. The first volume was published in Milan on 15 January 1929. The founder and the editor in chief was Giovanni Rocco. The mission of the journal was stated in the introduction letter accompanying the first volume: it was supposed to independently reflect the contemporary architectural scene of Italy and other countries. Despite political tension, “Rassegna di architettura” was intended to be independent from the polemics, including those about the relations between the regime and architectural language. In addition, it was not supposed to promote any architectural style. As stated in the editors’ letter, “inspired by vast and intended eclectic styles, we aspire to cover the best and the most significant architectural works, created mainly in Italy” (Rocco 1929, p. 1, author’s translation). Amongst the authors we encounter such important names as Alberto Sartoris, Pietro Bottoni, Enrico Griffini, Giovanni Muzio, etc. “Rassegna di architettura” had the role of one of the most significant architectural outlets in the first half of the 1930s until the takeover by “Architettura”, ruled by Marcello Piacentini.

One of the characteristics of the journal was a particular attention to the illustrations. Every article was filled with thoroughly selected visual materials. This particularity gave Paladini the possibility to create an image of the Soviet architectural scene by filling his article with diverse illustrations, some of which remained without accurate attribution.

Vinicio Paladini’s article “Lo spirito moderno…” for the first time in a European press provides such a vast and synthetic overview of the actual architecture of the USSR. Thirteen pages are enriched with illustrations of some of the most significant buildings and projects of the Soviet Avant-garde. Going deeper into the article, we can notice that Paladini made an interesting choice of protagonists. It is obvious that his attention is mostly oriented towards the professors and the students of the Faculty of Architecture of Higher Artistic and Technical Studios, or in other words, the famous VKhUTEMAS2. The mentioned transliteration is used in this article with the reference to the latest studies (Bokov 2020). However, other variants such as “Vchutemas” (Quilici 1991) or “Vhutemas” (Khan-Magomedov 1990) may be found in the literature. Among the protagonists of the article are Ivan Leonidov (J. Leonidoff), Vladimir Pashkov (Pashkoff), Mikhail Barshch (M. Bartsch), Mikhail Sinjavsky, Moisei Ginsburg (Ginnsburg), Mikhail Korjev (Korjeff), Sergei Kojin, Alexandr Burov (Buroff) as well as brothers Alexandr, Victor and Leonid Vesnin (Vesnine). The transliteration in brackets displays Paladini’s reproduction of Russian surnames presented in “Lo spirito moderno…”.

The article starts with an intensive metaphor, which aims to characterize the actual process of artistic renovation and the transformation of existing artistic movements of the first decade of the 20th century into the soil for new forms and ideas. Reflecting on the necessity of a change to the critical vocabulary that would respond better to the contemporary art process, Paladini introduced a new term, “formal realism”, which he used frequently throughout the article. By these “real forms”, he meant “some typically contemporary aspects of reality, caught in certain moments, which are used in their obvious forms, subjects to the overall idea of the construction to suggest certain values <…> Forms of the objects in their constancy, in their inexpressiveness, in their function, in their structure, in what they can recall in our memory as a response to the needs of our civilization, these forms are able to materialize the play of imagination in art” (Paladini 1929, author’s translation). With this complex characteristic, Paladini determines the main trait of contemporary architecture—that is, its correspondence to society’s needs.

In defining the image of new art, Paladini declares its contraposition to the “lyric futurist, cubist, expressionist art” and sees it as something “sturdy, pure, clean” (Author’s translation). He refers to the fear of standardization which was very common in previous times, and argues that every architecture has its own character even when implementing the universal language, similar manners of formal and constructive articulation. For Paladini, the beauty of the architecture consists in the coexistence of fantasy (practical and expressive motives) and imagination (the value of consistency and rhythm that awakens the spiritual harmony) (Barbaro 1973).

To confirm his point, Vinicio Paladini presents a comparison between modernist French and Soviet architecture. While both the Soviet Avant-garde and French school of Perret e Le Corbusier share “the simplicity of the form, the particular lightness of the construction, the perfect balance between rational severity and poetical gracefulness” (Author’s translation), Paladini argues that Soviet architecture has a distinguished character, defined by the tragedy of the October Revolution, and is dependent on Russian history as well as on the aesthetics of suprematism.

In his analysis of different projects, Paladini divides the article in two parts. The first part consists of the projects, defined by Paladini as technically complex and of a great financial cost. He sees them not as utopian but as practically realistic “if not now, when the actual economic conditions are difficult, then in the future, when the centralized nature of USSR will make possible the realization of these ambitious projects, that respond to the necessities of mass, about which should think the regime”. In this citation are obvious the references to the successful years of New Economic Policy of USSR in the early 1920s, that outlived itself by 1929, and to the changes towards the new course, or the first Five-year plan. One can feel Paladini’s personal affections for the Soviet state and his hope for the success of planned economy, which was an object of common interest in Italy as well.

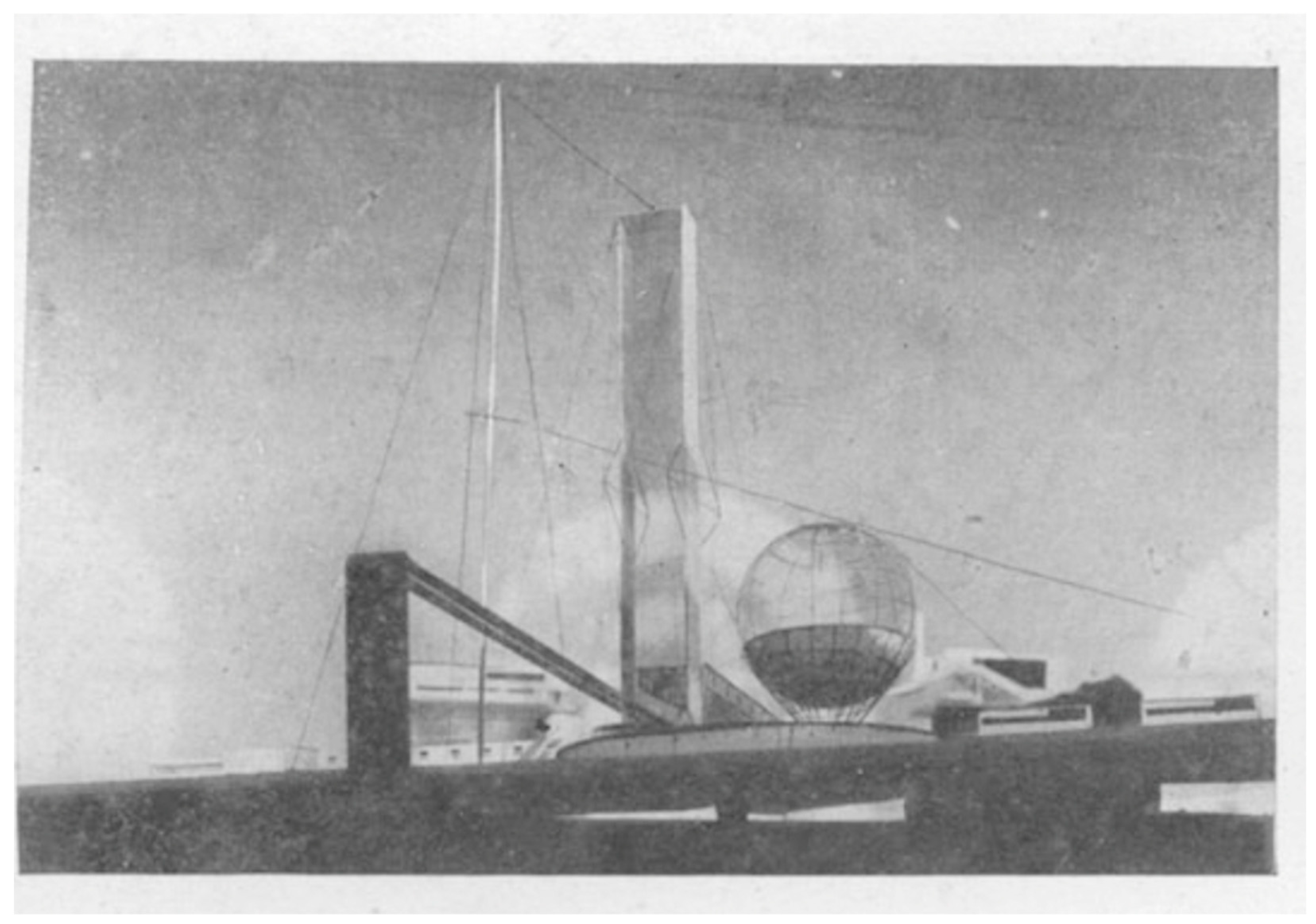

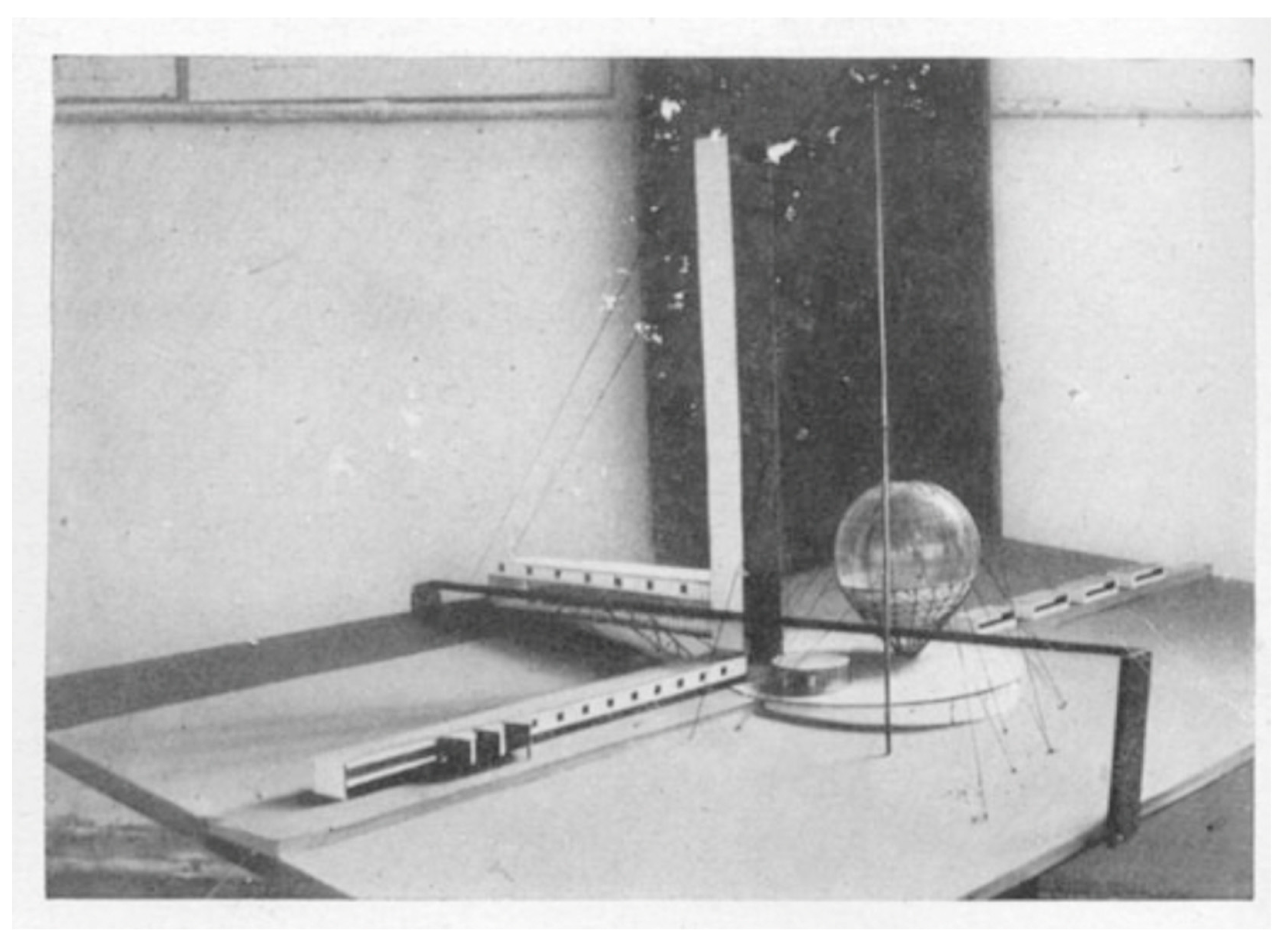

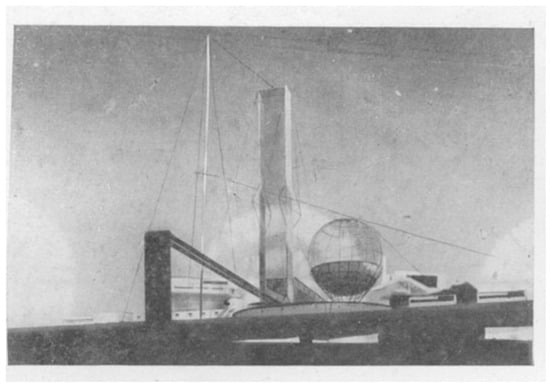

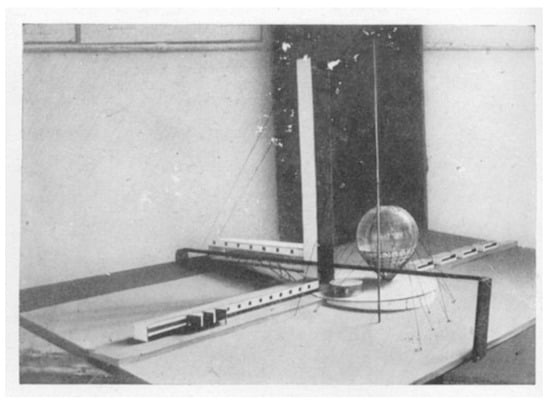

The first project in Paladini’s article is the Lenin Institute for Librarianship by Ivan Leonidov from 1927 (Figure 2). The former dedicates to it almost a whole page and recalls it frequently further into the article. Paladini attributes to Leonidov’s work the clearest expression of “exclusively Russian tendency to posing a problem of construction”. Reflecting on the Lenin Institute, Paladini refers to it as “perhaps one of the most original pieces of work” (Author’s translation). He also notices the strong connection between Leonidov’s architecture and suprematism aesthetics. Describing the beauty of rhythms and forms, surfaces and volumes, Paladini takes in consideration the ideas of Malevich’s objectless universum that reveal the true value of the library. He mentions the aesthetic nature of the project as well, in which utilitarian reasons are the basis for its abstract values.

Figure 2.

Lenin Institute for Librarianship, Ivan Leonidov, 1927. Image published in Vinicio Paladini (1929), “Lo spirito moderno e la nuova architettura nell’U.R.S.S.”, Rassegna di architettura, Anno I, n. 3,—15 March 1929. P. 110. Archaeology and Art History Library, Rome.

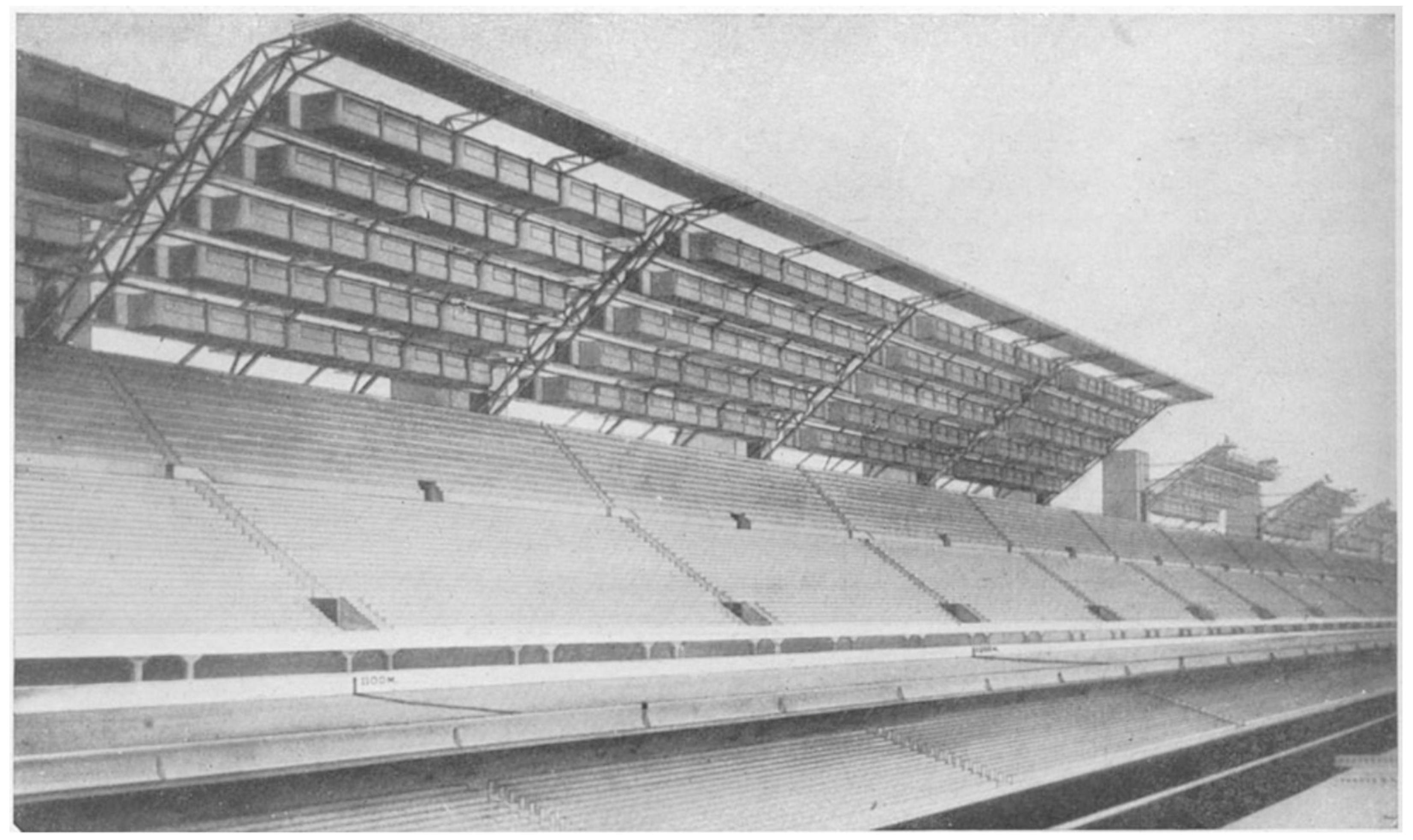

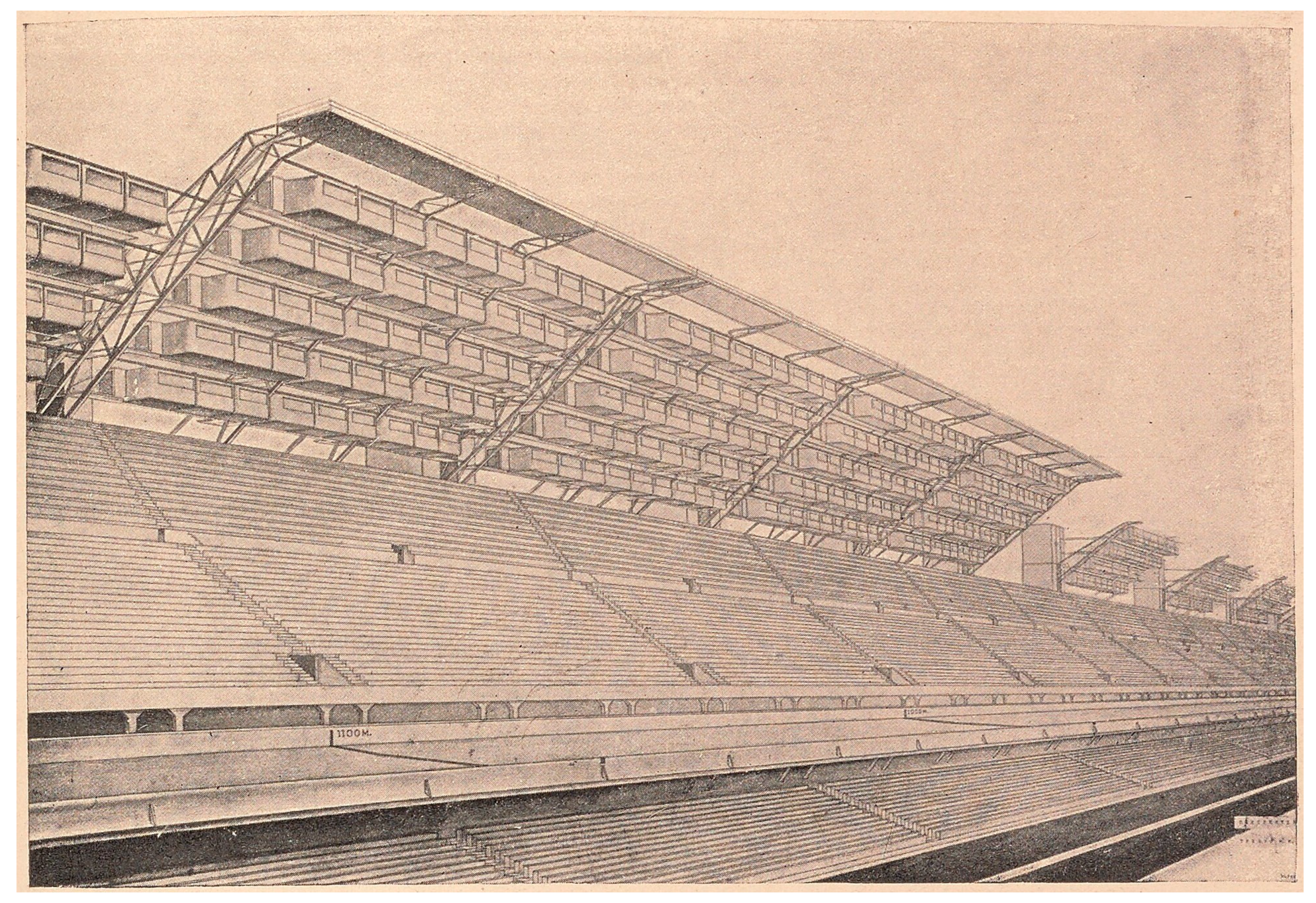

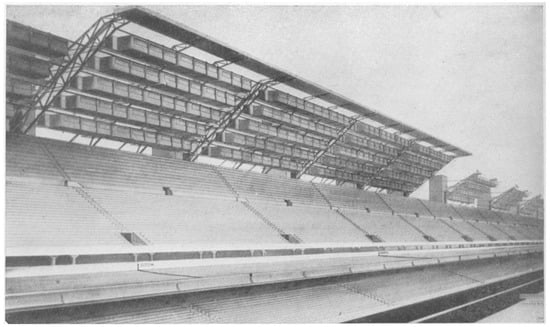

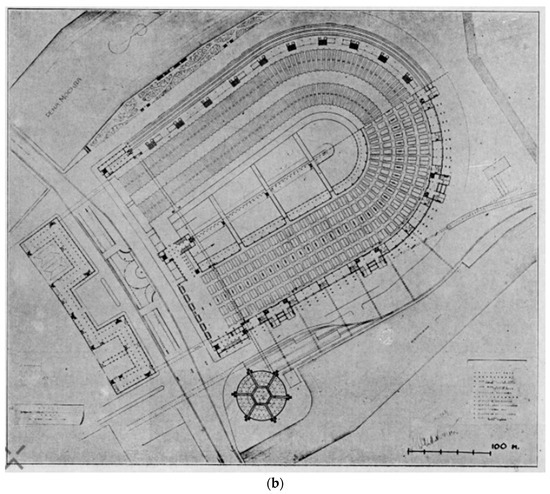

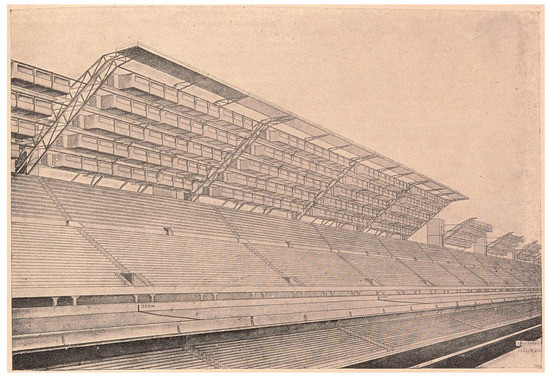

Another project, which for Paladini represents a Russian tendency, is an International Red Stadium by Mikhail Korjev from 1926 (Figure 3). This case is particularly important for the present analysis as Korjev is the only architect in the article adherent to the group of rational architects called the “Association of New Architects”—ASNOVA (Associaciya Novyh Arkhitektorov) founded by Nikolay Ladovsky in 1923. The other group of Avant-garde architects, to which belong other protagonists of Paladini’s work, is the Society of Contemporary Architects—OSA (Obschestvo Sovremennykh Arkhitektorov), headed by Alexandr Vesnin, that represented the constructivist branch. It is important to bring into focus that Paladini himself does not emphasize the role of Korjev as the only rationalist architect. Indeed, he does not even present the official division of Soviet architects into two movements: rationalism and constructivism. One of the reasons for choosing the International Red Stadium could have been the exposition of the Soviet pavilion in Paris in 1925, where this project was presented in the ideas of Korjev’s master Ladovsky. In brief description of the project, Paladini noticed the dramatic effect of the tribunes and their complete unity.

Figure 3.

Project for International Red Stadium, Mikhail Korjev, 1926. Image published in Vinicio Paladini (1929), “Lo spirito moderno e la nuova architettura nell’U.R.S.S.”, Rassegna di architettura, Anno I, n. 3,—15 March 1929. P. 104. Archaeology and Art History Library, Rome.

Asserting the rights of these projects to be constructed, Paladini puts Soviet Avant-garde architects in one line with Italian Renaissance and Baroque masters by declaring “I reckon that nobody would want to erase from the history of architecture the unrealized projects of Bernini, Michelangelo, Filarete, and Bibiena” (Author’s translation).

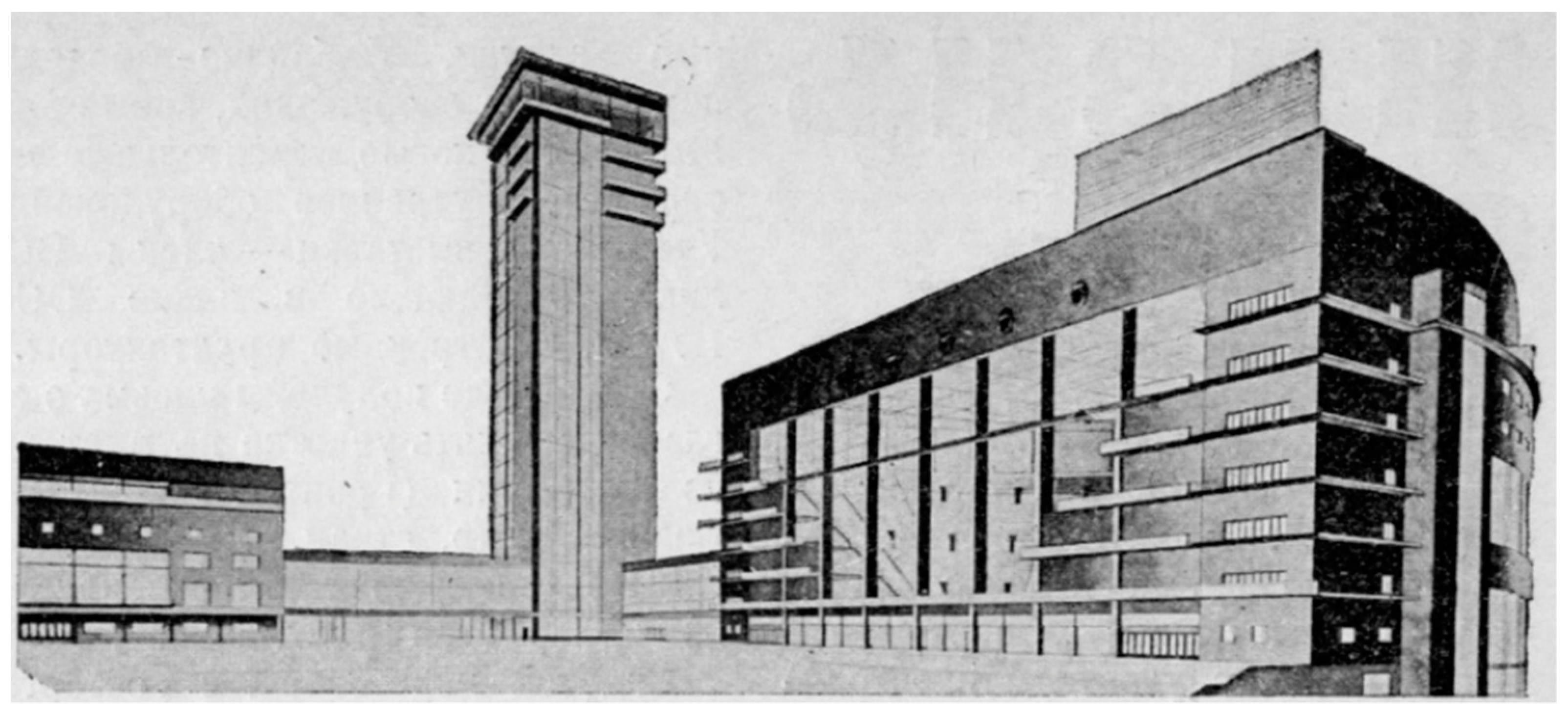

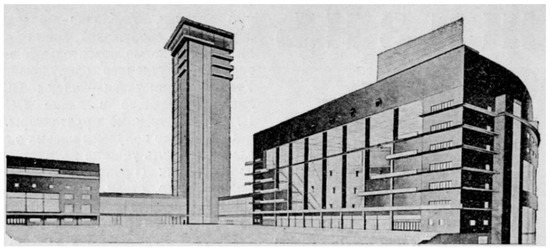

Vinicio Paladini builds the second part of the article around the easily realizable projects that respond to the reality and existing necessities of Soviet society. This chapter begins with the Palace of Labor by Sergey Kojin from 1926 (Figure 4). Paladini presents the readers with an important comment, where he defines the new problem of contemporary architecture in the USSR: “This idea to stabilize the intimate contact between the mass and the group that has decisive and administrative functions is a characteristic of the political regime in the USSR” (Author’s translation). This reflection takes us back to Paladini’s constant idea of coexistence and collaboration between leftist politics and Avant-garde architecture. Being a part of the Italian rationalist movement in architecture, Paladini notices in Kojin’s project one of the principles once declared by Gruppo 7 in their manifest (Gruppo 7 1926), which is the idea of continuity between classical tradition and contemporary architecture. This connection, according to Paladini, appears in the resemblance between the ancient Greek theater and Roman amphitheater and the Palace of Labor, where tiers of the building create a vivid movement of sunlight.

Figure 4.

Palace of Labor, Sergey Kojin, 1926. Image published in “Sovremennaja Arkhitektura (1926)”, vol. 4, p. 107. Lenin Russian State Library.

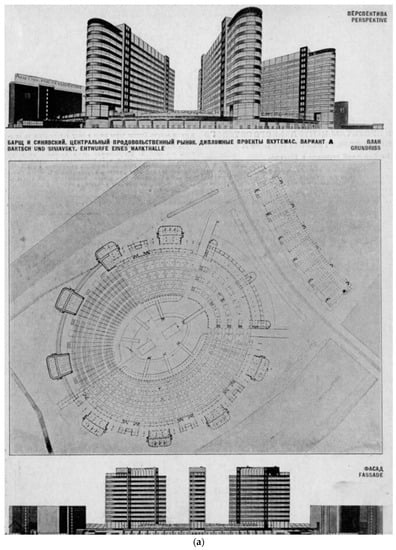

The work of architects Mikhail Barshch and Mikhail Sinjavsky for Central Market from 1926 (Figure 5a,b) represents a particular interest from the practical point of view, according to Paladini. He highlights new expressive forms in utilitarian elements of this architecture. The intended demonstration of functional and technical details is the honesty and clarity of Soviet architecture.

Figure 5.

(a) Central Market, Mikhail Barshch and Mikhail Sinjavsky, 1926. Variant A. Image published in “Sovremennaja Arkhitektura (1926)”, vol. 4, p. 95. Lenin Russian State Library. (b) Central Market, Mikhail Barshch and Mikhail Sinjavsky, 1926. Variant B. Image published in “Sovremennaja Arkhitektura (1926)”, vol. 4, p. 96. Lenin Russian State Library.

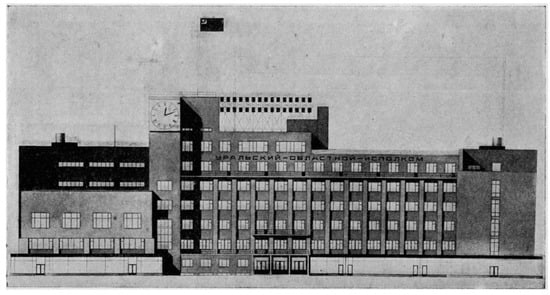

The constant dominance of plastic articulation over other principles emerges in the projects of the Vesnin brothers as well, among them the building for the regional executive committee in Sverdlovsk from 1926 (Figure 6). Their active use of realistic elements (Vinicio Paladini practically implements this term as a definition of functional and technical elements of construction) such as radio antenna, speakers, and monitors “gives to the projects the special image that recalls in memory “The Tentacular Towns”3, “Metropolis”4, Frans Masereel5, Vladimir Majakovsky6—the most exciting phenomena of contemporary life. Something gigantic, in front of which we feel ourselves small and weak” (Author’s translation). With this metaphor, Paladini once again gives the characteristic of typically Russian spirit7.

Figure 6.

Building for regional executive committee in Sverdlovsk, Alexandr, Victor and Leonid Vesnin, 1926. Image published in “Sovremennaja Arkhitektura (1926)”, vol. 5–6, p. 124. Lenin Russian State Library.

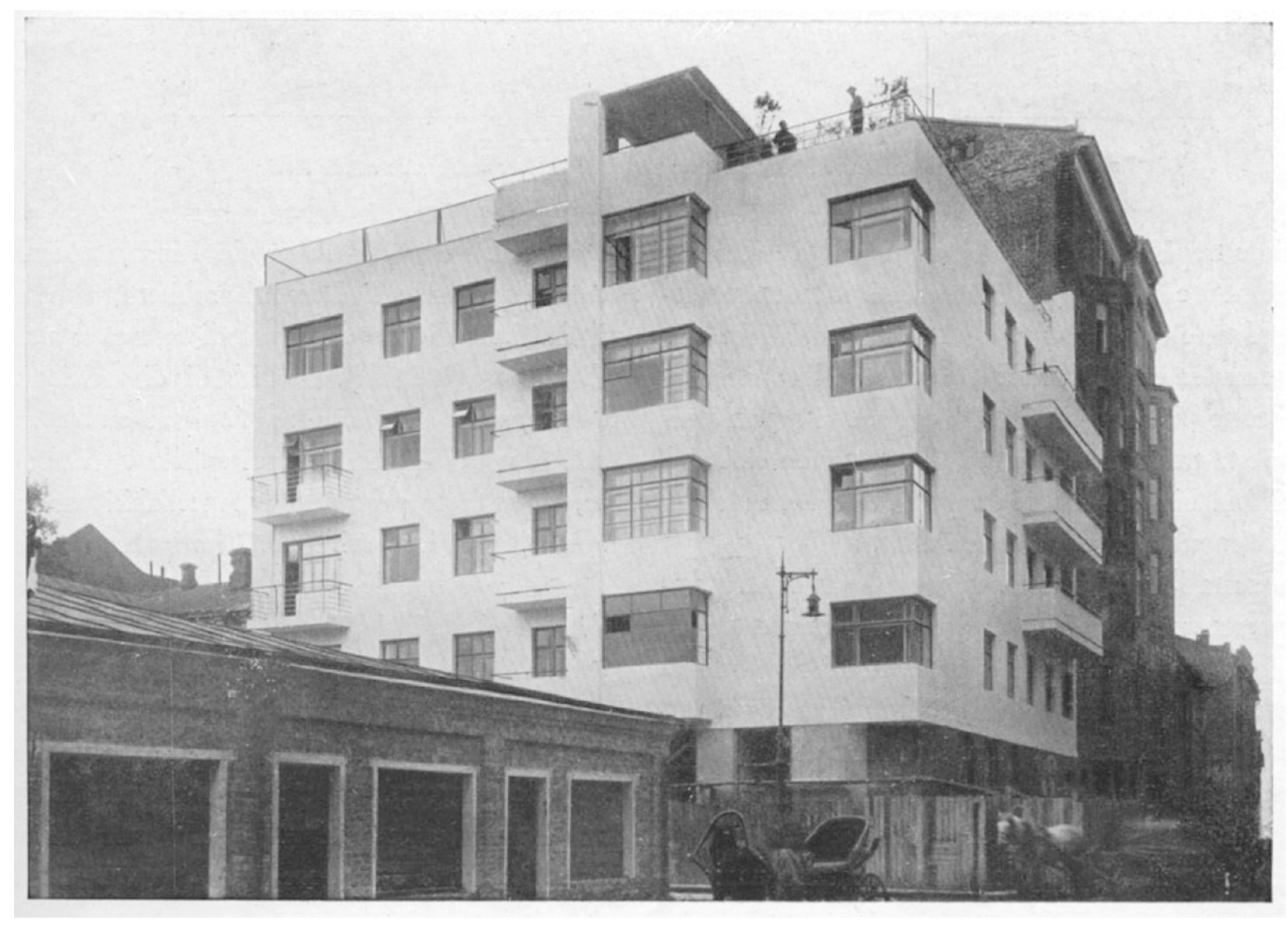

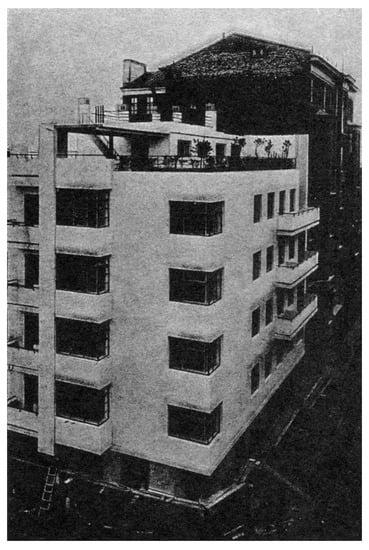

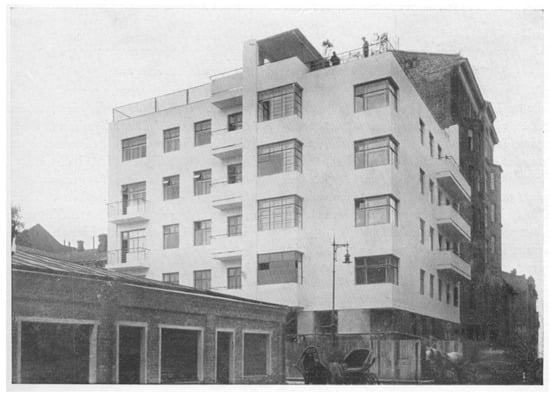

As an antithesis to the architecture of the Vesnin brothers, Paladini refers to Moisei Ginsburg and his work. One of the leaders of Soviet constructivism, he received his education in Italy, from where, according to Paladini, “he had brought the calm sense of the masses, in love with the broad surfaces and long lines; he is the closest to that feeling of order, simplicity that could be called classic” (Author’s translation). To demonstrate Ginsburg’s architecture, Paladini presents the Gosstrakh apartment complex (1926–1927) (Figure 7), which was one of the first examples of communal housing in Moscow. In the 1920s, there was a high level of interest towards the idea of collective household in the USSR. Thus, Paladini defines Ginsburg’s work as “one of the most typical examples of the architecture, dictated by the needs, emersed abruptly on the basis of the new structure of the Soviet state” (Author’s translation). He then describes meticulously the composition of the building to the European reader, while contraposing the processes in the USSR to those in capitalistic countries, where everything tends to isolate itself from one another.

Figure 7.

Gosstrakh apartment complex, Moisei Ginsburg, 1926–1927. Image published in “Sovremennaja Arkhitektura (1927)”, vol. 4–5, p. 124. Lenin Russian State Library.

In conclusion, Paladini defines a “formula” of modernist architecture in general and Soviet architecture in particular. He was able to outline the distinctive features of the Soviet architecture among other European schools, referring to its “live, ever-changing, developing nature”. The main trait and achievement of the Soviet Avant-garde for Paladini consists in “formal realism”, the enrichment of the architecture with utilitarian forms and their aesthetical value. In his conclusion, he states that “The USSR gave us one of the purest examples of what should be the instruments responding to humanity’s practical and spiritual needs, even if they were brought about by the Revolution” (Author’s translation).

2.2. Image Attribution

One of the aims of the present analysis of “Lo spirito moderno…” is to determine different sources of illustrations accompanying the article. Was it the professional Soviet press, or were the photos and designs from personal archives kindly shared with Vinicio Paladini? It should be noted that a major part of the published images could have been found in the professional Soviet press. The main resource was found to be the periodic journal “Contemporary architecture” (1926–1930)8, founded by the society of constructivist representatives OSA and ruled by Moisei Ginsburg and Alexandr Vesnin. However, illustrations of certain projects, some of them of a particular importance, are not present in any public open source. All this enforces us to conclude that direct relationships between the Italian researcher and Soviet architects seemed to be possible. Moreover, in the article, Paladini confirms his direct contacts by recalling “long and complex discussions with Russian architects, obstructed by my low level of the Russian language and their limited level of French”. In addition, in the paragraph dedicated to the Vesnin brothers, Paladini describes the atmosphere at their house, which he calls “the heart of new theories, where new artists get together to discuss and elaborate, with a glass of vodka and a slice of balyk, with a cup of tea and a piece of bread with a caviar” (Author’s translation).

Therefore, the first images in the article that illustrate the project for the Lenin Institute by Ivan Leonidov (Figure 8) were never published in any journal. Following, a building of Gosstrakh constructed by Moisei Ginsburg is presented in the article with two unknown photos (Figure 9). It is possible to suppose that, after the photoshoot for the journal, some of the pictures remained in Ginsburg’s private collection and were then shared with his Italian colleague. The same uncertainty may be found in one of the illustrations of the Planetarium project, 1927, by Mikhail Barshch and Mikhail Sinjavsky, as well as in those of Central Market project by the same architects.

Figure 8.

Image of Lenin Institute, published in Vinicio Paladini (1929), “Lo spirito moderno e la nuova architettura nell’U.R.S.S.”, Rassegna di architettura, Anno I, n. 3,—15 March 1929. P. 110. Archaeology and Art History Library, Rome.

Figure 9.

Image of Gosstrakh apartment complex, Moisei Ginsburg, 1926–1927, published in Vinicio Paladini (1929), “Lo spirito moderno e la nuova architettura nell’U.R.S.S.”, Rassegna di architettura, Anno I, n. 3,—15 March 1929. P. 103. Archaeology and Art History Library, Rome.

One of the central mysteries to that article is the image of Mikhail Korjev’s project for the International Red Stadium. That image had never been published in any known issue of the professional press before. In the existing bibliography from the 1920s until present day it could be found just a few times. The first publication, which most probably became the source of the illustration, was a part of a catalogue of projects of VKhUTEMAS students for the period from 1920 to 1927 (Figure 10). Vinicio Paladini supposedly saw it during the Werkbund exhibition in Stuttgart in 1927. Alongside the Weissenhof village, there were also other exhibition rooms, one of which was dedicated to the projects and architectural models from different countries. Taking in consideration that among the Soviet participants there were actual professors of VKhUTEMAS (Werkbund Ausstellung die Wohnung 1927), it is likely that the catalogue of the best projects was demonstrated to the visitors. In 1982–1983 at the Palazzo delle Esposizioni in Rome took place the exhibition “Architecture in the country of Soviet, 1917–1933. Art of propaganda and city construction” (Murasov 1982). One of the exhibited pieces was this exact image of the International Red Stadium, published in Paladini’s article. The show was accompanied by a catalogue; however, even in the comments to the list of works, there is no mention of its provenance or the actual collocation. In addition, in the Russian literature, this image of the project was never published even in the modern catalogue of students’ works from the collection of the Schiusev State Museum of Architecture (Chepkunova 2011); instead, it makes an appearance once in S.O. Khan-Magomedov’s monographic volume on Mikhail Korjev, once again without any details (Khan-Magomedov 2009).

Figure 10.

International Red Stadium. Tribunes for spectators. Mikhail Korjev, 1926. Image from the catalogue (Arkhitektura 1927) Arkhitektura: Raboty Arkhitekturnogo fakulteta VKhUTEMASa 1920–1927, p. 45. Lenin Russian State Library.

3. Reflections on Chosen Projects

The analysis of this first synthetical article published in western professional press about Soviet avant-garde architecture creates several questions. Putting aside the problem of a source for numerous illustrations, one of the first questions is what was the criteria to the choice of projects and architects? Among mentioned names don’t appear those of Konstantin Melnikov, obviously well-known after the International Exhibition in Paris in 1925, and of Ilya Golosov, the architect of Zuev’s Club in the process of construction in the moment of Paladini’s first visit9,10 to Moscow. Moreover, there is no project younger than 1926 mentioned in the article, even though before that time Soviet architects had already presented numerous exceptional projects worth mentioning. The main Paladini’s interest appears to have been directed to young professionals, who have just graduated from VKhUTEMAS, such as Leonidov, Barshch, Sinjavsky and Kojin. Focusing mainly on younger generation of Avant-grade architects, he doesn’t forget about their principal professors—Vesnin brothers and Moisei Ginsburg. However, regardless of their acknowledgement, Paladini doesn’t include such projects as headquarters for trading company “Arcos”(1924) and especially that for the “Palace of Labor” competition (1923), published in Walter Gropius’ “International Architektur” in 1925 and undoubtedly familiar to Paladini (Gropius and Moholy-Nagy 1925, p. 32).

One of the reasons for the chosen approach could be the time period, when Vinicio Paladini sojourned in Moscow in autumn 1927–spring 1928. In that case, the projects’ choice could be explained by their relevance and excitement from oncoming construction. Easily accessible in Moscow issues of “Contemporary Architecture” of 1926–1927 could have favored the choice.

4. Conclusions

Undoubtedly, the article in “Rassegna di architettura” has a generic nature and, according to Paladini, its goal consists in a confrontation of the Russian school with other European movements, as well as in positioning the Soviet Avant-garde architecture in a vast scene of new artistic tendencies. However, what remains unclear is why, when mentioning VKhUTEMAS as the center of new Soviet architecture, Paladini leaves out the important fact that within the school there were two independent societies, OSA and ASNOVA. Mentioning only the “S.A.” group and their journal “Contemporary Architecture”, he almost eliminates the difference between rationalist and constructivist architects when, in his analysis of the International Red Stadium of Korjev, he does not accentuate the architect’s affiliation to Ladovsky’s group. Is it possible to suggest that Paladini’s unilateral approach could have been caused by his probable direct connection with exclusively constructivist architects?

The critique of the contemporary spirit and new architecture in the USSR, offered by Vinicio Paladini in the pages of “Rassegna di architettura” embeds the common ideas, connecting the characteristics and achievements of the Soviet Avant-garde to the bolshevist politics and the consequences of the October Revolution. At the same time, the Italian researcher sees a potential for the future development of this architecture and considers it a perfect balance between functional poetics, caused by society’s needs, and national values. It is therefore recommended that Paladini’s work deserves special credit and it undoubtedly should be taken in consideration while studying the history of Western interest in the Soviet Avant-garde.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

Data sharing is not applicable to this article.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

Notes

| 1 | From it. “from Moscow (Russia)”. Annuario della Regia Scuola di Architettura in Roma. (Anno Accademico 1925–1926). Elenco degli studenti iscritti nel 1925–1926. III anno. p. 221. |

| 2 | VKhUTEMAS—Vysshie Khudozhestvenno Tehnicheskiye Masterskiye. Russian State Art and Technical School, 1920–1930. |

| 3 | In his article, Vinicio Paladini refers to “Villes tentaculaire” by Emile Verhaeren published in 1896. This piece is considered to be one of the central works of French simbolic poetry, and its author is called the pioeer of modernism. The recurrent theme of this body of work is the modern city life and the process of urbanisation in adherent territories. |

| 4 | Here is intened the film “Metropolis” by German director Fritz Lang. The story line un silent anti-utopia takes place in the future. One can say, that the city and its architecture become the protagonists of the film. |

| 5 | Frans Masereel (1889–1972)—Belgic artist, one of the representatives of expressionist art. |

| 6 | Vladimir Majakovsky (1893–1930)—Soviet poet, one of the representatives of futurist art. |

| 7 | From it.—“lo spirito tipicamente russo”. |

| 8 | The name of the journal in Russian is “Sovremennaja Arkhitektura”. |

| 9 | To recover Paladini’s notes from his first visit to Moscow see (Paladini 1927). |

| 10 | To recover Paladini’s notes from his first visit to Mosow see (Paladini 1928). |

References

- Anno Accademico. 1925–1926. (Annuario della Regia Scuola di Architettura in Roma 1926). Elenco degli studenti iscritti nel 1925–1926. III anno. Roma: Tipografia Ditta Figli Pallotta, p. 221. [Google Scholar]

- Arkhitektura: Raboty Arkhitekturnogo fakulteta VKhUTEMASa 1920–1927. 1927. Moscow: Izdaniye VKhUTEMASa.

- Baldacci, Paolo. 2006. Vinicio Paladini 1902–1971. Dipinti, collages, tempere e disegni di un protagonista dell’arte italiana tra le due guerre. Catalogo dell’Asta 32, 5 dicembre 2006. Milano: Porro&Co Art Consulting. [Google Scholar]

- Barbaro, Umberto. 1973. Razionalismo nell’architettura. Il Raduno, 14 aprile 1923. In Materiali per l’analisi dell’architettura moderna: La prima esposizione italiana di architettura razionale. Edited by Michele Cennamo. Napoli: Fausto Fiorentino Editore, pp. 160–62. [Google Scholar]

- Bokov, Anna. 2020. Avant-Garde As Method: Vkhutemas and the Pedagogy of Space 1920–1930. Zurich: Park Books. [Google Scholar]

- Brungardt, Christina. 2015. On the Fringe of Italian Fascism: An Examination of the Relationship between Vinicio Paladini and the Soviet Avant-Garde. Ph.D. dissertation, The City University of New York, New York, NY, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Carpi, Umberto. 1981. Bolscevico immaginista: Comunismo e avanguardie artistiche nell’Italia anni Venti. Napoli: Liguori. [Google Scholar]

- Chepkunova, Irina, ed. 2011. VKhUTEMAS. Mysl’ Materialna. Catalogue of VKhUTEMAS students’ works’ collection from Šusev State Museum of Architecture. Moscow: Legejn, Šusev State Museum of Architecture. [Google Scholar]

- De Feo, Vittorio. 1963. URSS architettura 1917–1936. Roma: Editori riuniti. [Google Scholar]

- Gropius, Walter, and Laszlo Moholy-Nagy. 1925. Internationale Architektur. München: Albert Langen Verlag. [Google Scholar]

- Gruppo 7. 1926. Architettura I. La Rassegna italiana, Anno IX. XVIII, 849–55. [Google Scholar]

- Khan-Magomedov, Selim. 1990. Vhutemas: Moscou 1920–1930. Paris: Editions du Regard. [Google Scholar]

- Khan-Magomedov, Selim. 2009. Mikhail Korjev. Moscow: Fond “Russkiy Avangard”, p. 78. [Google Scholar]

- Lista, Giovanni. 1988. Dal futurismo all’immaginismo: Vinicio Paladini. Salerno: Il cavaliere azzurro. [Google Scholar]

- Murasov, K. 1982. Architettura nel paese dei Soviet, 1917–1933. Arte di propaganda e costruzione della città. Milano: Electa. [Google Scholar]

- Paladini, Vinicio. 1925. Arte nella Russia dei Soviets. Il padiglione dell’U.R.S.S. a Venezia. Roma: Edizioni “La bilancia”. [Google Scholar]

- Paladini, Vinicio. 1927. Un allegro stabilimento cinematografico. Cinematografo 1: 19. [Google Scholar]

- Paladini, Vinicio. 1928. Lettere dalla Russia Cinematografi—Teatri e propaganda nella Russia sovietica. Cinemalia 2: 23–24. [Google Scholar]

- Paladini, Vinicio. 1929. Lo spirito moderno e la nuova architettura nell’U.R.S.S. Rassegna di Architettura, Anno I, n. 3. 100–12. [Google Scholar]

- Paladini, Vinicio. 1934a. Mosca 1934. Il Tevere, October 11. [Google Scholar]

- Paladini, Vinicio. 1934b. Viaggio in Russia. Il Tevere, October 3. [Google Scholar]

- Quilici, Vieri. 1969. L’architettura del costruttivismo. Bari: Laterza. [Google Scholar]

- Quilici, Vieri. 1991. Il costruttivismo. Roma: Laterza. [Google Scholar]

- Rocco, Giovanni. 1929. Avvertenza. Rassegna di architettura, Anno I, n. 1. 1. [Google Scholar]

- Sovremennaja Arkhitektura, 1926. 4, pp. 95–96, 107; 5–6, p. 124.

- Sovremennaja Arkhitektura, 1927. 4–5, 124.

- Vyazemtseva, Anna, and Elke Pistorius. 2018. Arkhitektura I gradostroitelstvo SSSR v zarubezhnoy pechati. In Sovetskoje gradostroitelstvo 1917–1941. Edited by Kosenkova Julia. Moscow: Progress-traditsiya, vol. 2, pp. 1183–215. [Google Scholar]

- Werkbund Ausstellung die Wohnung, 1927. 23 Juli–9 Oct. Amtlicher Katalog. Stuttgart: Tagblatt-Buchdruckerei. 101–15.

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).