Abstract

This article examines the visual representation of pagan idols in Byzantine book illumination and investigates how such images were employed to convey a sense of geographical or ethnic distance. The main focus of this study is a group of illuminated manuscripts containing two of the most popular texts in the Byzantine world: Barlaam and Ioasaph and the Alexander Romance. These manuscripts include numerous representations of statuary that Byzantine readers would have easily recognized as being associated with the religious practices and superstitions of distant and foreign populations, thereby reinforcing their own self-identification with “civilized” characters. Through a comparative analysis of manuscripts such as Athon. Iviron 463 (Barlaam and Ioasaph) and Venice, Istituto Ellenico cod. 5 (Alexander Romance), this article explores the variety of iconographic solutions adopted by Byzantine artists to enhance the “ethnographic” function of idol images. A close examination of these solutions sheds new light on how visual narratives contributed to the construction of notions of identity, otherness, and ethnicity in Byzantium.

1. Introduction

Idolatry is a fundamental notion for understanding the principles that regulated the production and perception of sacred images in Byzantium. Beginning with the patristic arguments against the veneration of pagan cult images (Finney 1994; Bigham 2004; Jensen 2022) and culminating with the iconoclastic controversy and the Second Council of Nicaea in 787 (Brubaker and Haldon 2001; Barber 2002; Humphreys 2021), the need to establish a clear distinction between the legitimate representation of the divine (the eikon/icon) and the illegitimate one (the eidolon/idol) became a crucial aspect in the relationship between art and religion in Byzantine culture. It is not surprising that the concepts of “idol” and “idolatry” have garnered increasing attention in the scholarly literature, which, in recent years, has been further enriched by new cross-cultural and interdisciplinary approaches (Dell’Acqua 2020; Chatterjee 2021). One central topic, however, has been little explored to date, namely, the ways in which Byzantine artists were able to represent the eidolon and make it recognizable to the viewers. Aside from a few contributions on specific phenomena (Wessel 1978; Jevtić 2016; Antonov and Maizuls 2018; Kruk 2021), we lack an extensive and updated study that investigates the prototypes, appearance, and functions of idol images in Byzantine art and that would serve as a counterpart to the main reference book on the subject for the Western Middle Ages, that is, The Gothic Idol by Michael Camille (Camille 1989). To fill this gap, for the past few years I have been working on a monograph titled “They Have Mouths but Do Not Speak”, which is currently in preparation. My goal is to examine the notion of idolatry in Byzantium from an art historical perspective and provide a comprehensive overview of how idols were represented in Byzantine artistic culture from the ninth to fifteenth centuries.

For the purposes of this discussion, I define “idol image” as any representation of an object of worship that is deemed illegitimate and/or prohibited by both its creator and its viewer. Such representations were not familiar to pagan Greco-Roman art, which typically incorporated images of cult objects (usually statues or reliefs) into contexts where such objects were legitimately allowed. It was only with the emergence of Jewish and Christian subjects in Late Antiquity that it became possible to identify idol representations that meet the definition given above: depictions of cult images perceived as inferior in the presence of a new, superior deity (Gasbarri 2022). The historical books of the Septuagint provided various opportunities for the introduction of these types of images. Examples include the panel representing the fall of the idols of Dagon in the Dura Europos synagogue and numerous early Christian depictions of the three young Jewish men fleeing from Nebuchadnezzar’s statue (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Syracuse (Italy). Museo Archeologico Regionale Paolo Orsi. Adelphia Sarcophagus (detail). Nebuchadnezzar and the three young Jewish men. Photo: Davide Mauro, Wikimedia Commons (CC BY-SA 4.0).

In Byzantine art, idols began to appear regularly from the ninth century onward and were mostly depicted as marble or metal statues in an elevated position, often atop a column or a pillar, with physical characteristics quite distinct from the two-dimensional, legitimate sacred images, the icons (Figure 2 and Figure 3). These idols usually illustrated episodes from the Septuagint or hagiographical accounts and were intended to convey a sense of religious alterity, whether depicting forbidden cults in the Old Testament—especially in the illustration of the Psalter (Gasbarri 2023)—or pagan gods vanquished by Christian saints (Chatterjee 2014, pp. 60–61, 109; Jevtić 2016).

Figure 2.

London. British Library. Add MS 19352, fol. 195r (detail). Sacrifices offered to idols. Photo: ©British Library Board, all rights reserved.

Figure 3.

London. British Library. Add MS 19352, fol. 15v (detail). David venerates an icon of Christ. Photo: ©British Library Board, all rights reserved.

In this article, I will specifically focus on Byzantine book illustrations in which images of idols served to communicate a sense of geographical and ethnic alterity, displaying the religious practices of distant or foreign populations. This “ethnographic” function is not uncommon in Byzantine iconography and recurs in various contexts, sometimes with a polemical agenda. Combined with additional details, such as unusual clothing and bizarre flora and fauna, idols were used as visual devices to describe the superstitious and savage customs of faraway lands and societies, whether imaginary or real (e.g., Egypt, Persia, India, etc.). At the same time, they conveyed physical and cultural detachment from communities perceived as primitive, crude, and uncivilized. This helped reinforce the viewers’ self-perception by facilitating their identification with the “civilized” characters. Here, I will examine some significant examples of the use of idols as signs of distance and ethnic otherness, specifically those included in illustrated manuscripts containing two of the most famous “bestsellers” of the Byzantine world and the global Middle Ages in general: Barlaam and Ioasaph and the Alexander Romance. A comparative analysis of these two case studies can help shed new light on the complex interweaving of art, religion, and society in Byzantium and provide an original perspective on Byzantine perceptions of ethnic and cultural identity—a topic that has attracted considerable scholarly interest in recent years (Kaldellis 2013; Kaldellis 2019a; Durak and Jevtić 2019; Stewart et al. 2022).

2. Idols as Villains: Barlaam and Ioasaph

The hagiographical novel known as Barlaam and Ioasaph (BHG 224 et 224a; CPG 8120), one of the most successful literary works of the Middle Ages, consists essentially of the Christianization of a complex corpus of narrative materials that arguably originated in Central Asia and inspired by the life of the Buddha (Cesaretti and Ronchey 2012; Cordoni 2014; Cordoni and Meyer 2015). The Byzantine version of the text, traditionally attributed to John of Damascus (d. 749), is now believed to be a product of the late tenth-century Athonite milieu. It was likely adapted from a Georgian version, the Balavariani, by the eminent monk and theologian Euthymios the Hagiorite (ca. 955–1028: Volk 2006, 2009; Shurgaia 2019a, 2019b).

Readers of the Byzantine Barlaam and Ioasaph may find it arduous to recognize substantial traces of the Buddhist roots of the story. In fact, the transformation of the original protagonist, Siddartha Gautama/Buddha, into the Christian prince Ioasaph resulted in a deliberate reconfiguration of the plot’s setting and purpose to fit into the tradition of Byzantine hagiography (Bádenas de la Peña 2015; Hilsdale 2018). This creates a paradoxical situation: Barlaam and Ioasaph retains elements of its Indian setting but introduces readers to a land that has already experienced the consequences of Christ’s incarnation and embraced enthusiastically the new religion. Yet Ioasaph’s father, King Abenner, denies the faith in the true God and returns to idol worship, persecuting Christians and sentencing monks and priests to death. In such context, the enlightenment received by the “Christian Buddha”, Ioasaph, consists of the discovery (or perhaps rediscovery) of his faith in Christ, thanks to the teaching of the pious monk Barlaam. Ioasaph’s initiation into Christianity involves several contentious debates with his father Abenner and culminates in his choosing a monastic “transfiguration” through strict asceticism.

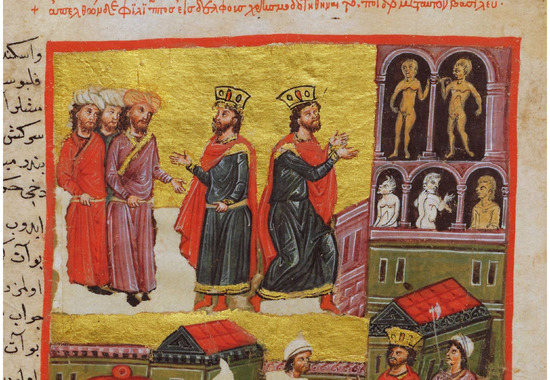

Aside from the names of some characters, the setting of Barlaam and Ioasaph rarely includes elements that convey significant geographical or ethnic distance. Most locations, such as Abenner’s palace and the desert, serve mainly as functional backdrops to re-enact tropes of early Christian hagiography, so that the battle against idols led by Barlaam and Ioasaph provides an opportunity to reaffirm the virtues of abandoning earthly goods and accepting martyrdom. This is also reflected in the miniatures of the few Byzantine illustrated manuscripts containing the text of Barlaam and Ioasaph, as they include numerous compositions clearly modeled on hagiographical prototypes. The eleventh-century Athon. Iviron 463 and the fourteenth-century Paris. gr. 1128 (Der Nersessian 1937, pp. 23–25, 26–27; Toumpouri 2017) show King Abenner with the typical attitudes of an evil ruler from hagiographical tradition, opposing the holy monks, his servants converted to Christianity, and his own son Ioasaph (Figure 4). What distinguishes the illustrations of Barlaam and Ioasaph from other hagiographical cycles is the occasional introduction of certain figurative elements that help provide a somewhat “ethnic” flavor to the visual narrative. In the Iviron codex, for example, there are some attendants with darker complexions, and almost all the male characters wear turbans, including the virtuous prince Ioasaph (Figure 5).

Figure 4.

Paris. Bibliothèque nationale de France. Paris. gr. 1128, fol. 4v (detail). King Abenner condemns some monks to death. Photo: gallica.bnf.fr/Bibliothèque nationale de France.

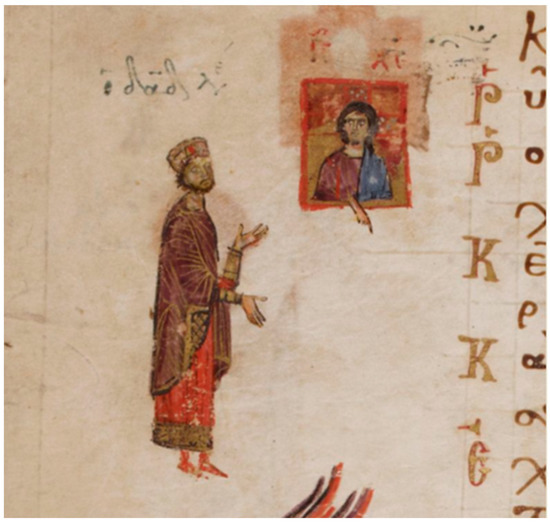

Figure 5.

Mount Athos. Holy Iviron Monastery. Athon. Iviron 463, fol. 14r (detail). Ioasaph desires to leave his palace. Photo: ©Holy Iviron Monastery, Mount Athos, all rights reserved.

There are only a few exceptions: the Christians condemned and killed by King Abenner, the monks fleeing persecution, and the protagonists of the parables told by Barlaam, which are set in a different narrative dimension. The use of turbans was not uncommon among the Byzantines and was not necessarily associated with a rigidly defined ethnic group or cultural identity, especially since turbans were part of the fashion of provincial elites from at least the eleventh century, if not much earlier (Parani 2003, pp. 68–70; Ball 2005, pp. 57–77; Kaldellis 2019b). As Cyril Mango convincingly explains, figurative arts rarely offer an entirely reliable account of the most mundane aspects of Byzantine daily life, even with regard to clothing (Mango 1981, pp. 51–52). For the readers of the Iviron codex (Pelekanidis et al. 1975, pp. 60–91, 306–22; D’Aiuto 1997; Toumpouri 2015, 2017; Egedi-Kovács 2017), acknowledging a turban as a mark of ethnicity or exoticism was not related so much to their own personal experience as it was to an established iconographic tradition that was not concerned with visualizing contemporary garments or environments in a faithful manner. In this fictional universe, clothes play an essential role in the process of building the characters’ identity, although not in a necessarily ethnic sense. This is exemplified by the miniature on fol. 123v (Figure 6), which depicts the moment of Ioasaph’s final catharsis, when the prince renounces his royal status before retiring to the desert. Ioasaph’s transformation from prince to hermit, comparable to a second birth, is emphasized by his abandonment of a luxurious robe, purple boots, and a turban in favor of a simple brown tunic.

Figure 6.

Mount Athos. Holy Iviron Monastery. Athon. Iviron 463, fol. 123v (detail). Ioasaph abandons his clothes and retreats to the desert. Photo: ©Holy Iviron Monastery, Mount Athos, all rights reserved.

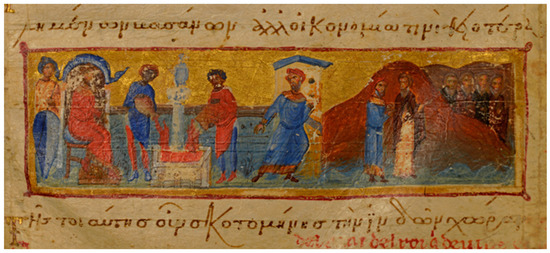

Idols are key components of the visual storytelling in most Byzantine cycles illustrating Barlaam and Ioasaph. Although their representation is usually limited to a few compositions that conform to hagiographical conventions (Jevtić 2016), their importance in the narrative cannot be overstated, as they accentuate the antagonistic relationships that bind individual characters or communities in the story. Modeled after the prototype of the merciless, pre-Christian pagan emperor, King Abenner shows a very intimate connection with idols, which constitute one of his main iconographic attributes. In the Iviron codex, idols are celebrated with especially gruesome rituals. On fol. 6r, for example, a marble statue is represented atop a column in the center of a fountain filled with fire, flanked by two dark-skinned characters (Figure 7). Abenner’s cruelty is emphasized by the direct contrast between the idol on the left and the group of pious monks on the right, who are depicted in a natural setting.

Figure 7.

Mount Athos. Holy Iviron Monastery. Athon. Iviron 463, fol. 6r (detail). King Abenner offers sacrifices to an idol. Photo: @Holy Iviron Monastery, Mount Athos, all rights reserved.

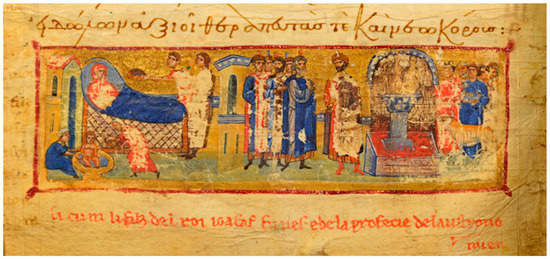

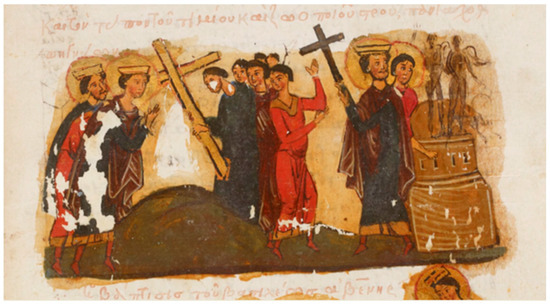

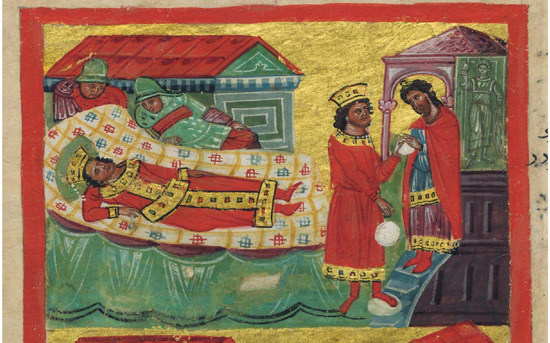

It is also worth noting that the fountain of fire on fol. 6r appears to be a corrupted version of the celestial fountain shown in Ioasaph’s supernatural vision of the city of God on fol. 99r (Cupane 2014a, p. 67; Figure 8). The elongated miniatures in the Iviron codex are particularly effective in highlighting the stark contrast between opposing themes. For instance, the scene of Ioasaph’s birth on the left side of fol. 8v is juxtaposed with the bloody sacrifice to idols ordered by Abenner on the right (Figure 9). Similarly, the destruction of the idols commanded by Ioasaph on fol. 109r is immediately followed by the construction of a church (Figure 10). While the cycles dedicated to Barlaam and Ioasaph do not generally depict idols in opposition to legitimate cult images—the icons—fol. 176r of Paris. gr. 1128 (Debruyne 2015) provides a unique variation of the traditional hagiographical motif of Christian saints annihilating idolatry. Here, after his conversion to Christianity, Abenner is shown violently destroying pagan statues with a massive wooden cross (Figure 11).

Figure 8.

Mount Athos. Holy Iviron Monastery. Athon. Iviron 463, fol. 99r (detail). Ioasaph has a vision of the City of God. Photo: ©Holy Iviron Monastery, Mount Athos, all rights reserved.

Figure 9.

Mount Athos. Holy Iviron Monastery. Athon. Iviron 463, fol. 8v (detail). Birth of Ioasaph/King Abenner offers sacrifices to idols. Photo: ©Holy Iviron Monastery, Mount Athos, all rights reserved.

Figure 10.

Mount Athos. Holy Iviron Monastery. Athon. Iviron 463, fol. 109r (detail). Ioasaph orders the destruction of idols and the building of a church. Photo: ©Holy Iviron Monastery, Mount Athos, all rights reserved.

Figure 11.

Paris. Bibliothèque nationale de France. Paris. gr. 1128, fol. 176r (detail). King Abenner destroys idols. Photo: gallica.bnf.fr/Bibliothèque nationale de France.

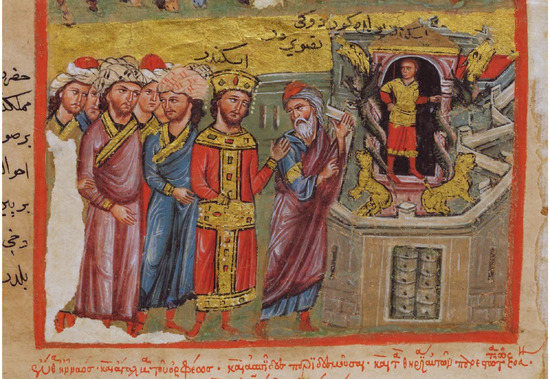

3. “Idols” as Destinations: The Alexander Romance

A significantly different case is that of the Alexander Romance, which circulated in several parallel versions and gained immense popularity throughout medieval Europe, with translations into numerous languages (Jouanno 2002; Zuwiyya 2011; Moennig 2016; Moore 2018; Stoneman 2022). The Romance is a fictional chronicle detailing the adventures of Alexander the Great and was especially popular in Byzantium, where Alexander also became a recurring character in visual culture (Paribeni 2006; Kalavrezou 2014). However, only one of the eighteen surviving Byzantine manuscripts of the Romance has preserved an extensive cycle of miniatures, that is, Venice, Istituto Ellenico di Studi Bizantini e Postbizantini cod. 5, which was produced for the Emperor of Trebizond Alexios III (r. 1349–1390). This highly luxurious codex contains a hybrid version of the text (the so-called γ recension: Von Lauenstein et al. 1962–1969; Jouanno 2009; Stoneman 2007–2012) and is illustrated with 250 large-format miniatures executed by three distinct artists. The complex history of this manuscript has been accurately reconstructed in scholarly literature (Xyngopoulos 1966; Trahoulia 1997, 2017), so I will not discuss it here. Instead, I will focus on the remarkable number of images of statuary featured in the miniatures.

The Alexander Romance (see Supplementary Materials) differs substantially from Barlaam and Ioasaph with regard to idolatry, as the narrative universe of the Romance is almost entirely pagan, and none of the characters has experienced Christ’s incarnation. Indeed, monotheism becomes a driving force of the story after Alexander meets with some Jewish priests who tell him about their one God (Jouanno 2018). This does not prevent him, however, from continuing to listen to oracles, receive premonitory dreams, and interact with animated statues and even talking cypresses (fol. 140r). In this case, our initial definition of “idol image” needs to be thoroughly revised: from Alexander’s perspective, there are no “idols”, but rather legitimate cult images to be worshipped and preserved. He is never depicted as a destroyer of statues or temples but rather as someone who regularly uses them. These objects of worship would have been considered idols only by the intended Christian readers of this manuscript. Evidently, the fairy-tale-like tone of the narrative, the numerous references to classical antiquity, and the recurrent encomiastic subtexts permitted a high degree of tolerance for the overall pagan atmosphere of the story.

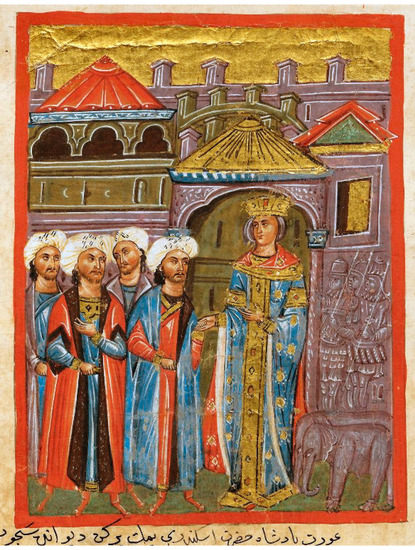

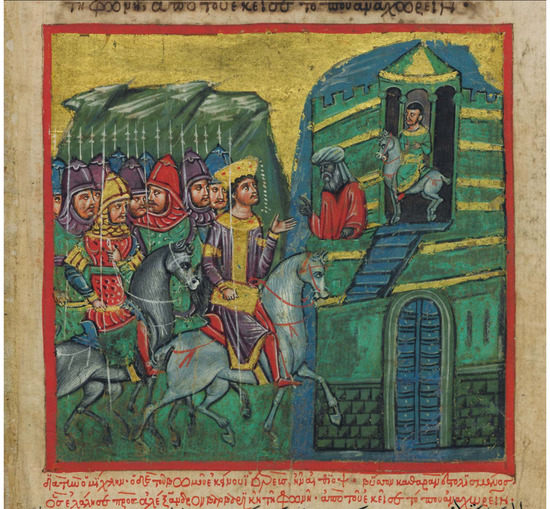

In the Romance, characters such as Alexander, his father Philip, his mother Olympias, his allies, and his enemies are often separated by great distances, leading them to rely on letters, ambassadors, and even dreams or visions to stay connected. This practice of long-distance communication also involves the use of figurative arts. Twice in the text, we find the literary trope of the “secret portrait”: both Darius, King of Persia, and the fictional Queen Kandake desire to see Alexander’s face and order their trusted artists to secretly paint a portrait of him (fols. 25r, 143v). The Romance is characterized by a remarkable prominence of images, which also emphasize the notion of distance, both geographical and ethnic. After all, it is with an image that the text expresses one of its central themes, that is, Alexander’s self-destructive will to overcome every known frontier. In one of the most intense passages of the Romance, while on his way to reach the ends of the earth, Alexander discovers a mosaic portrait of the ruler Sesonchosis, with an inscription ordering travelers not to continue any further lest they incur certain death. In order to avoid interrupting his journey, Alexander decides to lie to his men and tell them that the mosaic contains only an auspicious message (fol. 103r, Figure 12).

Figure 12.

Venice. Istituto Ellenico di Studi Bizantini e Postbizantini cod. 5, fol. 103r (detail). Alexander and his army reach the image of Sesonchosis. Photo: ©Istituto Ellenico di Studi Bizantini e Postbizantini, Venice, all rights reserved.

The artists who worked on the miniatures of the Venice manuscript demonstrated a rare ability to effectively represent the majority of the works of art described in the Romance by using a wide variety of visual devices. One of the most interesting cases involves memorial statues, which appear very often in the text. The miniature on fol. 29r shows Alexander speaking to the Macedonians shortly after Philip’s death, in front of a statue celebrating the deceased king. At first glance, the statue appears to be a depiction of Philip himself as if he were still alive, rather than a sculpture. Only its smaller proportions and placement inside a shrine allow the viewer to recognize the actual nature of the image. Its physical proximity to Alexander helps confirm the legitimacy of the royal succession (Figure 13).

Figure 13.

Venice. Istituto Ellenico di Studi Bizantini e Postbizantini cod. 5, fol. 29r (detail). Alexander speaks to the Macedonians beside Philip’s memorial statue. Photo: ©Istituto Ellenico di Studi Bizantini e Postbizantini, Venice, all rights reserved.

In the case of statues representing deities, those that Christian readers would have identified as “idols”, the artists took a different approach. Some of these cult objects resemble the typical idols of Byzantine iconography and appear as generic, monochrome statuettes, occasionally featuring demonic elements, as can be seen in the Oracle of Delphi visited by Philip (fol. 16v, Figure 14). At other times, statues of ancient deities have more individual features. On fol. 63v, for example, Alexander is shown visiting a temple containing a statue of Orpheus. The statue is surrounded by numerous animals, as is typical in depictions of Orpheus, but it is also clad in armor, which does not conform to any established Greco-Roman iconographic tradition (Figure 15). In the Venice manuscript, most of the cult images are represented as rectangular bas-reliefs, and their appearance sometimes risks making them look like two-dimensional Christian icons. In the miniature on fol. 53r, Alexander is standing in front of a cult image of Zeus, who is portrayed as a warrior holding a spear and a shield. Without the overall context of the scene, the portrait could be mistaken for that of a Christian military saint (Figure 16). This eclectic approach is also evident in decorative statuary, as demonstrated by the miniature on fol. 160v, which depicts Queen Kandake appearing in front of a sumptuous bas-relief representing armed warriors and elephants, characterized by a strongly antiquarian taste (Figure 17).

Figure 14.

Venice. Istituto Ellenico di Studi Bizantini e Postbizantini cod. 5, fol. 16v (detail). Philip visits the Oracle of Delphi. Photo: ©Istituto Ellenico di Studi Bizantini e Postbizantini, Venice, all rights reserved.

Figure 15.

Venice. Istituto Ellenico di Studi Bizantini e Postbizantini cod. 5, fol. 63v (detail). Alexander visits the temple of Orpheus. Photo: ©Istituto Ellenico di Studi Bizantini e Postbizantini, Venice, all rights reserved.

Figure 16.

Venice. Istituto Ellenico di Studi Bizantini e Postbizantini cod. 5, fol. 53r (detail). Alexander’s dream/Alexander visits the temple of Zeus. Photo: ©Istituto Ellenico di Studi Bizantini e Postbizantini, Venice, all rights reserved.

Figure 17.

Venice. Istituto Ellenico di Studi Bizantini e Postbizantini cod. 5, fol. 160v (detail). Queen Kandake’s entrance. Photo: ©Istituto Ellenico di Studi Bizantini e Postbizantini, Venice, all rights reserved.

The pre-Christian setting of the Alexander Romance means that cult images primarily serve to highlight the extent of the territories traversed by the characters. Not surprisingly, the temples, shrines, and oracles that house statues and bas-reliefs are often described as the final destination of a long journey that involves overcoming trials or battles. In the Venice manuscript, these “idols”—if we can still call them that—establish a complex pictorial vocabulary aimed at visualizing not only geographical but also ethnic distances. The recurrent presence of statuary combines with extensive use of stereotypical characterizations for each people encountered by Alexander in the course of his adventures: the Scythians wear pants, the Pygmies are short in stature, the Indians have a very dark complexion, and similarly dark-skinned is the Ethiopian priest who drives the Macedonians from his temple on fol. 183r (Figure 18). Statues become an essential component of this type of “ethnography of the fringes” (Kaldellis 2013, p. 66) and contribute to creating a sense of historical authenticity, even amidst fantastical elements such as centaurs and giant ants (fols. 132r, 100v; Cupane 2014b).

Figure 18.

Venice. Istituto Ellenico di Studi Bizantini e Postbizantini cod. 5, fol. 183r (detail). Alexander’s encounter with an Ethiopian priest. Photo: ©Istituto Ellenico di Studi Bizantini e Postbizantini, Venice, all rights reserved.

4. Conclusions

By examining the Byzantine illustrations of Barlaam and Ioasaph and the Alexander Romance comparatively, it is possible to discern two very different approaches to the use of images of idols. In reinterpreting the Buddha’s story from a Christian perspective, Barlaam and Ioasaph takes advantage of the tale’s exotic location to portray an alternative world where idolatry is still a concrete reality against which the Christian hero must fight. The illustrated manuscripts of Barlaam and Ioasaph deal with the intentional artificiality of this world by incorporating a few “ethnic” elements firmly rooted in traditional hagiographical iconography, with images of idols falling squarely into such a tradition. In contrast, the Venice Alexander Romance shows how, under specific circumstances, the Byzantine attitude toward the visual representation of idols (and the concept of idolatry itself) could be almost entirely free from theological or polemical implications. Once introduced into a controlled figurative system, the statues worshipped by Alexander help reinforce the setting’s fictional nature and effectively endorse an escapist fantasy for the reader. In both cases, the representations of idols as markers of ethnic and geographical distance highlight the role of visual culture in the construction and negotiation of identity and provide new insights into Byzantine perceptions of the “other”.

Supplementary Materials

A digitized copy of the Alexander Romance preserved in the Istituto Ellenico of Venice is available at http://eib.xanthi.ilsp.gr/gr/manuscripts.asp? (accessed on 7 April 2023).

Funding

This research was funded by the Pontifical Institute of Mediaeval Studies (Toronto), the HUJI Center for the Study of Early Christianity (Jerusalem), the Dumbarton Oaks Research Library and Collection (Washington DC), and ANAMED Koç University Research Center for Anatolian Civilizations (Istanbul).

Acknowledgments

This research is partly related to the project entitled Manuscritos bizantinos iluminados en España: obra, contexto y materialidad-MABILUS (MICINN-PID2020-120067GB-I00) (https://mabilus.com, accessed on 7 April 2023) and was supported by the Pontifical Institute of Mediaeval Studies (Toronto), the HUJI Center for the Study of Early Christianity (Jerusalem), the Dumbarton Oaks Research Library and Collection (Washington DC), and ANAMED Koç University Research Center for Anatolian Civilizations (Istanbul). I am very grateful to Verónica Abenza Soria, Manuel Castiñeiras González, Paolo Cesaretti, Mark Huggins, Antonio Rigo, Linda Safran, Carlos Sánchez Marquez, Gaga Shurgaia, and Niccolò Zorzi for their invaluable help during the preparation of this article. I would also like to express my heartfelt thanks to Father Theologos Iverites (Holy Iviron Monastery) and Vassileios Koukousas (Venice, Istituto Ellenico di Studi Bizantini e Postbizantini) for facilitating my research.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

References

- Antonov, Dmitriy, and Mikhail Maizuls. 2018. Ruina idolorum. Iconography of Christian Idoloclasm: East and West. Ikon 11: 249–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bádenas de la Peña, Pedro. 2015. La rédaction byzantine de “Barlaam et Josaphat,” considérations sur la paternité et la composition. In Barlaam und Josaphat: Neue Perspektiven auf ein europäisches Phänomen. Edited by Constanza Cordoni and Matthias Meyer. Berlin: De Gruyter, pp. 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ball, Jennifer. 2005. Byzantine Dress: Representations of Secular Dress in Eighth- to Twelfth-Century Painting. New York: Palgrave MacMillan. [Google Scholar]

- Barber, Charles. 2002. Figure and Likeness: On the Limits of Representation in Byzantine Iconoclasm. Princeton: Princeton University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Bigham, Steven. 2004. Early Christian Attitudes toward Images. Rollinsford, NH: Orthodox Research Institute. [Google Scholar]

- Brubaker, Leslie, and John Haldon. 2001. Byzantium in the Iconoclast Era (ca 680–850): The Sources; An Annotated Survey. Aldershot: Ashgate. [Google Scholar]

- Camille, Michael. 1989. The Gothic Idol: Ideology and Image-Making in Medieval Art. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Cesaretti, Paolo, and Silvia Ronchey, eds. 2012. Storia di Barlaam e Ioasaf. La vita bizantina del Buddha. Turin: Einaudi. [Google Scholar]

- Chatterjee, Paroma. 2014. The Living Icon in Byzantium and Italy: The Vita Image, Eleventh to Thirteenth Centuries. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chatterjee, Paroma. 2021. Between the Pagan Past and Christian Present in Byzantine Visual Culture: Statues in Constantinople, 4th–13th Centuries CE. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cordoni, Constanza. 2014. Barlaam und Josaphat in der europäischen Literatur des Mittelalters: Darstellung der Stofftraditionen-Bibliographie-Studien. Berlin: De Gruyter. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cordoni, Constanza, and Matthias Meyer, eds. 2015. Barlaam und Josaphat: Neue Perspektiven auf ein europäisches Phänomen. Berlin: De Gruyter. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cupane, Carolina. 2014a. The Heavenly City: Religious and Secular Visions of the Other World in Byzantine Literature. In Dreaming in Byzantium and Beyond. Edited by Christine Angelidi and George T. Calofonos. Farnham: Ashgate, pp. 53–68. [Google Scholar]

- Cupane, Carolina. 2014b. Other Worlds, Other Voices: Form and Function of the Marvelous in Late Byzantine Fiction. In Medieval Greek Storytelling: Fictionality and Narrative in Byzantium. Edited by Panagiotis Roilos. Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz, pp. 183–202. [Google Scholar]

- D’Aiuto, Francesco. 1997. Su alcuni copisti di codici miniati mediobizantini. Byzantion 67: 5–59. [Google Scholar]

- Debruyne, Iphigeneia. 2015. Barlaam et Joasaph (Paris grec 1128). Création et tradition d’un manuscrit paléologue. Ph.D. thesis, Université de Fribourg, Fribourg, Switzerland. Available online: https://sonar.ch/global/documents/304648 (accessed on 7 April 2023).

- Dell’Acqua, Francesca. 2020. Iconophilia: Politics, Religion, Preaching, and the Use of Images in Rome, c. 680–880. London and New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Der Nersessian, Sirarpie. 1937. L’illustration du Roman de Barlaam et Joasaph. Paris: De Boccard. [Google Scholar]

- Durak, Koray, and Ivana Jevtić, eds. 2019. Identity and the Other in Byzantium: Papers from the Fourth International Sevgi Gönül Byzantine Studies Symposium. Istanbul: Koç University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Egedi-Kovács, Emese. 2017. Un trésor inexploré entre Constantinople, le Mont Athos et le monde franc. Le Manuscrit Athon. Iviron 463. In Investigatio Fontium II. Griechische und lateinische Quellen mit Erläuterungen. Edited by László Horváth and Erika Juhász. Budapest: Eötvös-József-Collegium, pp. 89–164. Available online: http://byzantium.eotvos.elte.hu/wp-content/uploads/Investigatio_II.pdf (accessed on 7 April 2023).

- Finney, Paul Corby. 1994. The Invisible God: The Earliest Christians on Art. New York: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Gasbarri, Giovanni. 2022. What Does an Idol Look Like? Visualizing Idolatry in Late Antique Jewish and Christian Art. In Iconotropy and Cult Images from the Ancient to Modern World. Edited by Jorge Tomás García and Sandra Sáenz-López Pérez. New York: Routledge, pp. 99–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gasbarri, Giovanni. 2023. Cristo contro gli idoli: Note critiche sul rapporto tra iconografia evangelica e idolatria nell’arte bizantina. Quaderni di Storia Religiosa Medievale. forthcoming. [Google Scholar]

- Hilsdale, Cecily J. 2018. Worldliness in Byzantium and Beyond: Reassessing the Visual Networks of Barlaam and Ioasaph. In Re-Assessing the Global Turn in Medieval Art History. Edited by Christina Normore. Amsterdam: ARC, pp. 57–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Humphreys, Mike, ed. 2021. A Companion to Byzantine Iconoclasm. Leiden: Brill. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jensen, Robin M. 2022. From Idols to Icons: The Emergence of Christian Devotional Images in Late Antiquity. Oakland: University of California Press. [Google Scholar]

- Jevtić, Ivana. 2016. Pierres vivantes. Sur la représentation des idoles dans la peinture paléologue. In Mélanges Catherine Jolivet-Lévy. Edited by Sulamith Brodbeck, Andréas Nicolaïdès, Paule Pagès, Brigitte Pitarakis, Ioanna Rapti and Élisabeth Yota. Paris: CNRS, pp. 255–76. [Google Scholar]

- Jouanno, Corinne, ed. 2009. Histoire merveilleuse du roi Alexandre maître du monde. Toulouse: Anacharsis. [Google Scholar]

- Jouanno, Corinne. 2002. Naissance et métamorphoses du Roman d’Alexandre. Domaine Grec. Paris: CNRS. [Google Scholar]

- Jouanno, Corinne. 2018. Byzantine Views on Alexander the Great. In Brill’s Companion to the Reception of Alexander the Great. Edited by Kenneth R. Moore. Leiden: Brill, pp. 449–76. [Google Scholar]

- Kalavrezou, Ioli. 2014. The Marvelous Flight of Alexander. In Medieval Greek Storytelling: Fictionality and Narrative in Byzantium. Edited by Panagiotis Roilos. Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz, pp. 103–14. [Google Scholar]

- Kaldellis, Anthony. 2013. Ethnography after Antiquity: Foreign Lands and Peoples in Byzantine Literature. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press. [Google Scholar]

- Kaldellis, Anthony. 2019a. Romanland: Ethnicity and Empire in Byzantium. Cambridge: Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Kaldellis, Anthony. 2019b. Ethnicity and Clothing in Byzantium. In Identity and the Other in Byzantium: Papers from the Fourth International Sevgi Gönül Byzantine Studies Symposium. Edited by Koray Durak and Ivana Jevtić. Istanbul: Koç University Press, pp. 41–52. [Google Scholar]

- Kruk, Miroslaw Piotr. 2021. Three Categories of the Reception of Classical Antiquity in Old Rus Art. In Byzantium and Renaissances. Dialogue of Cultures, Heritage of Antiquity—Tradition and Modernity. Edited by Michał Janocha, Aleksandra Sulikowska, Irina Tatarova, Zuzanna Flisowska, Karolina Mroziewicz, Nina Smólska and Krzysztof Smólski. Warsaw: Campidoglio, pp. 341–57. [Google Scholar]

- Mango, Cyril. 1981. Discontinuity with the Classical Past in Byzantium. In Byzantium and the Classical Tradition. Edited by Margaret Mullett and Roger Scott. Birmingham: Centre for Byzantine Studies, University of Birmingham, pp. 48–57. [Google Scholar]

- Moennig, Ulrike. 2016. A Hero without Borders: 1 Alexander the Great in Ancient, Byzantine and Modern Greek Tradition. In Fictional Storytelling in the Medieval Eastern Mediterranean and Beyond. Edited by Carolina Cupane and Bettina Krönung. Leiden: Brill, pp. 159–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moore, Kenneth R., ed. 2018. Brill’s Companion to the Reception of Alexander the Great. Leiden: Brill. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parani, Maria G. 2003. Reconstructing the Reality of Images: Byzantine Material Culture and Religious Iconography (11th–15th Centuries). Leiden: Brill. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paribeni, A. 2006. L’immagine di Alessandro a Bisanzio e nel Medioevo occidentale. In Immagine del mito. Iconografia di Alessandro Magno in Italia. Edited by Paola Stirpe. Rome: Gangemi, pp. 70–98. [Google Scholar]

- Pelekanidis, Stylianos M., Panagiotis C. Christou, Chrisanthe Tsioumis, and Soteres N. Kadas. 1975. The Treasures of Mount Athos: Illuminated Manuscripts. Vol. 2, The Monasteries of Iveron, St. Panteleion, Esphigmenon, and Chilandari. Athens: Ekdotike Athenon. [Google Scholar]

- Shurgaia, Gaga. 2019a. Sull’autore della Vita Barlaam et Ioasaph (CPG 8120). Studium 115: 562–99. [Google Scholar]

- Shurgaia, Gaga. 2019b. L’edificante storia di Barlaam e Ioasaph: ὑπό, παρά oppure ὑπὲρ Εὐθυμίου? In Iranian Studies in Honour of Adriano V. Rossi, Part Two. Edited by Sabir Badalkhan, Gian Pietro Basello and Matteo De Chiara. Naples: UniorPress, pp. 917–53. [Google Scholar]

- Stewart, Edward, David Alan Parnell, and Conor Whately, eds. 2022. The Routledge Handbook on Identity in Byzantium. New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stoneman, Richard, ed. 2007–2012. Il Romanzo di Alessandro. 2 vols. Rome: Fondazione Lorenzo Valla. [Google Scholar]

- Stoneman, Richard, ed. 2022. Alexander the Great: The Making of a Myth. London: British Library. [Google Scholar]

- Toumpouri, Marina. 2015. L’illustration du “Roman de Barlaam et Joasaph” reconsidérée. Le cas du Hagion Oros, Monè Ibèron, 463. In Barlaam und Josaphat: Neue Perspektiven auf ein europäisches Phänomen. Edited by Constanza Cordoni and Matthias Meyer. Berlin: De Gruyter, pp. 389–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toumpouri, Marina. 2017. Barlam and Ioasaph. In A Companion to Byzantine Illustrated Manuscripts. Edited by Vasiliki Tsamakda. Leiden: Brill, pp. 149–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trahoulia, Nicolette S. 1997. The Greek Alexander Romance: Venice Hellenic Institute Codex Gr. 5. Athens: Exandas. [Google Scholar]

- Trahoulia, Nicolette S. 2017. The Alexander Romance. In A Companion to Byzantine Illustrated Manuscripts. Edited by Vasiliki Tsamakda. Leiden: Brill, pp. 169–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Volk, Robert, ed. 2006. Historia animae utilis de Barlaam et Ioasaph (spuria). Vol. 2, Text und zehn Appendices. Berlin: De Gruyter. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Volk, Robert, ed. 2009. Historia animae utilis de Barlaam et Ioasaph (spuria). Vol. 1, Einführung. Berlin: De Gruyter. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Von Lauenstein, Ursula, Helmut Engelmann, and Franz Parthe. 1962–1969. Der griechische Alexanderroman. Rezension Γ nach der Handschrift R herausgegeben. 3 vols. Meisenheim am Glan: Hain. [Google Scholar]

- Wessel, Klaus. 1978. Idole. In Reallexikon zur byzantinischen Kunst. Vol. 3, Himmelsleiter–Kastoria. Stuttgart: Hiersemann, pp. 318–26. [Google Scholar]

- Xyngopoulos, Andreas. 1966. Les Miniatures du Roman d’Alexandre le Grand dans le Codex de l’Institut Hellénique de Venise. Athens: n.p. [Google Scholar]

- Zuwiyya, Z. David, ed. 2011. A Companion to Alexander Literature in the Middle Ages. Leiden: Brill. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).