1. Introduction

The phrase “white ballet” refers to large corps de ballet compositions in romantic ballets in which dancers portray supranatural and bodiless beings such as ghosts, wilis, dryads, mermaids, and maidens under spells. They are dressed in lightweight, white costumes synchronously performing movements accompanying the dance of the prima ballerina. Dance “en pointe”, flying arabesques-the semantics of the “white” ballet itself as airy and exalted, include all of the most recognized images of ballet and serve as its business card (

Figure 1). The ballets

Giselle,

La Sylphide,

Swan Lake,

La Bayadère, and

The Nutcracker with their large “white acts” comprise the basis of the repertoire of ballet companies throughout the world.

The phrase “black dance” refers to the group of social dances that arose in African American society in the USA and Latin America. “Black dance” has a complex nature, as it is the syncretic merging of European and African components, the adaptation of social dances on the theatrical stage and cinema. (

Banes 1994, p. 58). “Black dancers” is not simply a racial characteristic including various skin colors, but a cultural characteristic that incites questions about self-identity, including Caribbean identity and the acceptance of the dancer by the spectator.

The art of ballet was born in Europe and for a long time remained a Europo-centric art form, thus the question about the color of skin did not and could not have arisen. French, Italian, and Russian dancers could be more less technical and expressive on stage, but the color of their skin in any case supported the white aesthetic. There are two main explanations for the “problematization” of the color of a ballet dancer’s skin. First, the dissemination of ballet beyond Europe, which was expressed in a deep interest in ballet and in the organization of national ballet schools and companies in America, Asia, and Africa. Second, the struggle for citizen’s rights against social discrimination, one of the forms of which was the myth that black-skinned individuals were unsuitable for ballet.

Cuba is a bright example of the creation of a ballet school in a country where the fight for social equality was tightly connected with overcoming racial segregation. State support for the national ballet company and international recognition of Cuban ballet were viewed as a great achievement of the socialist revolution. In Pedro Simon’s words, “Our school was created in order to destroy the myth that blacks should not dance ballet. The Cuban National Ballet unites all races: African, Latino, Asian, Caucasian” (Quoted after:

Alonso 1986, p. 41).

Pedro Simon here transmits the concept of racial democracy or “We are all Cubans”, on which the discourse of Cuban national identity has been built since the 1880s and 1890s. This implied acknowledgement of an ethno-cultural mixture as a key factor in the formation of identity; however, in practice, Cuban society was highly segregated. Following victory in the Cuban revolution, Fidel Castro declared the eradication of racism as one of the primary political tasks which was solved through programs of available housing, the elimination of illiteracy, and comprehensive free education and healthcare. In 1961, at the First May meeting, Fidel Castro announced that the epoch of discrimination and racism was over. After that, the topic of racism itself was declared to be counterrevolutionary (

de la Fuente 2001, pp. 259–316). In the 2000s, the debate on racism was renewed in Cuba (

Glassman 2011), including ballet.

Hamlet Betancourt León, a Mexican scholar, asked whether you can consider the Ballet Nacional de Cuba (BNC) to be representative of the Cuban nation. And he answered in the negative: The Cuban nation differs in its extreme variety of phenotypes, and the overwhelming majority in the ballet company includes dancers of the European type (

León 2006,

2009).

The Cuban nation truly has a complex ethnographic composition. Immigrants from Europe played a leading role in the ethnogenesis of Cubans (offspring from Spanish colonizers, and émigrés) as did offspring from African nations, tracing back to generations of slaves brought in as manpower starting in the XVI century. Brown-skinned individuals, those of mixed race, and Creoles from the Caribbean migrating to the island during the XVIII to XX centuries participated in forming the Cuban nation. Immigrants from China and Japan also played a definitive role. The influence of the indigenous population was also present on the island of Cuba, although its role was minimal (the indigenous population was practically completely eliminated by the start of the XVII century) (

Pervushin 1978, pp. 6–7). An important trend within the framework of the genesis of the Cuban nation is the decrease in the number of whites and purely Negro population, and the appearance of various types of mixed races (

Mokhnachev 1961, p. 218). In 1861, in Cuba, the white population was 54%, Creole was 46%, of which free “colored” people was formed 16%, black slaves made up 28%, and Chinese 2%. In 2010, whites comprised 65% of the population, blacks 10%, and mixed race 25%. According to some assessments, the offspring of African slaves form at least 40% of the Cuban population (

Dridzo 2013, p. 268).

As T. Henken writes, the identification of an individual as “black” is quite different in the USA and Cuba. In the USA, racial identity is determined using “one-drop rule”, meaning an individual with even one black ancestor is considered to be black, regardless of his/her actual phenotype. T. Henken clarified that, in Cuba, “one drop of European blood” determines that an individual is not black and that “all Cubans share the island’s African heritage (regardless of their concrete origin or phenotype)” (

Henken 2008, p. 352), and racial identity is determined as the degree of distance from pure black roots. In the Cuban popular lexicon, there are at least two hundred terms that refer not to the relationship to ancestors, but to the shade of one’s skin:

blanco (white),

jabao (high yellow),

trigueño (wheat colored),

mestizo (mixed race),

mulato (mulatto),

mulato adelantado (advanced mulatto),

mulato blanconazo (light mulatto),

pasa (raisin),

negro azul (blue Black),

indio (Indian),

prieto (dark), and

negro (Black)” (

Henken 2008, p. 353). In order to evaluate the degree of phenotypica variety of the Cuban people, it is sufficient to glance at any group photograph.

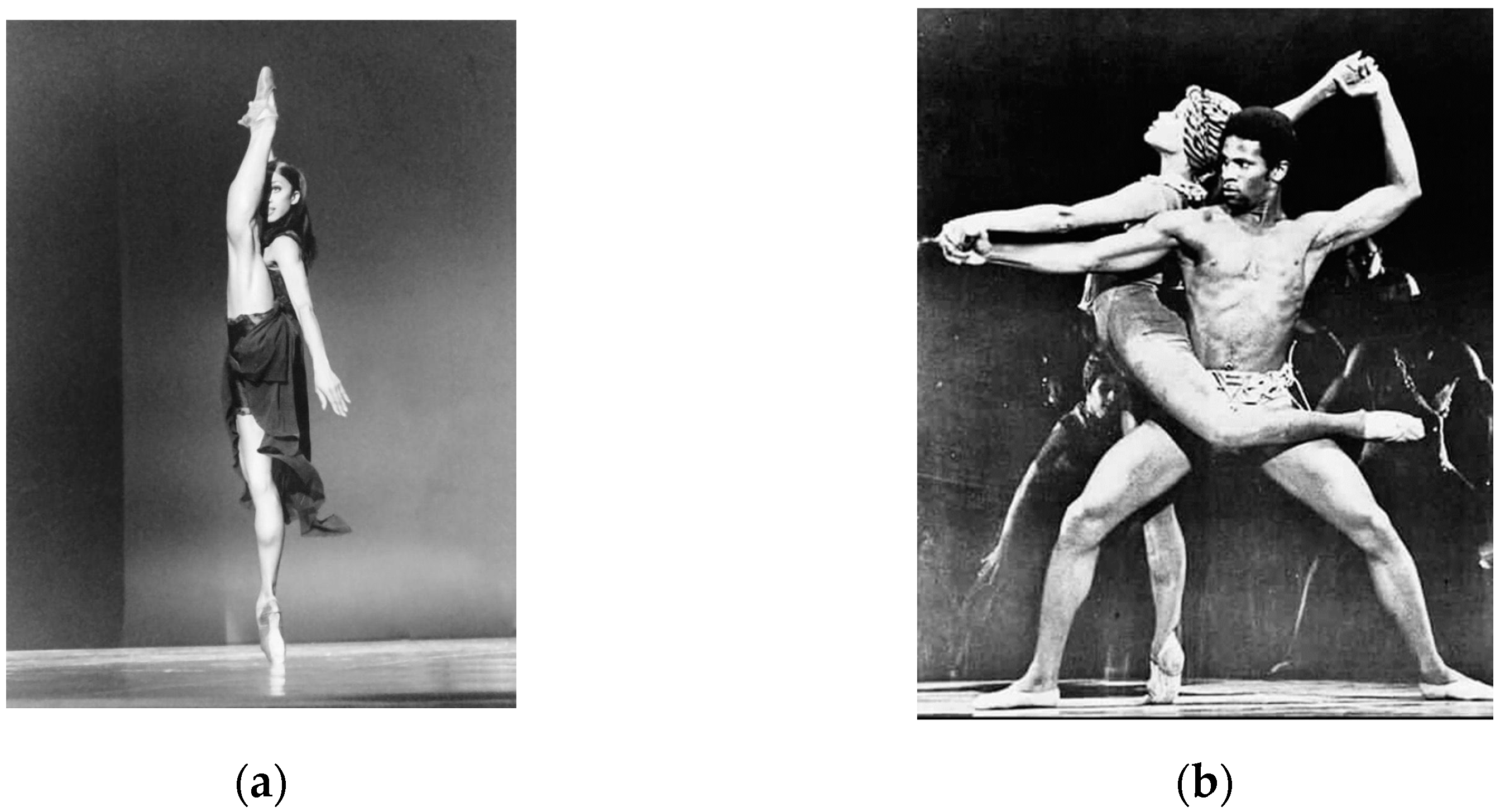

Indeed, having repeatedly visited Havana in 2013, 2017, and 2019, one of us (Mayumi Sakamoto de Miasnikov, (

Figure 2a,b)) noted the large variety of skin colors among students of the Cuban National Ballet School. On the Fitzpatrick Skin Classification scale (

Fitzpatrick 1975, pp. 33–34), we can state that among the girls there were very few with dark brown, deeply pigmented dark brown, or darkest brown skin (Fitzpatrick skin type IV–VI), and the girls with light skin tones, golden honey or olive, or moderate brown skin (Fitzpatrick skin type III) prevailed. Among the young boys, there were more dark-skinned individuals ranging from moderate to darkest brown (Fitzpatrick skin type III–IV). There were few light-skinned boys of the light, golden honey, or olive tones (Fitzpatrick skin type II). In the BNC, there is a larger variety in skin color but those with darkest brown skin have more difficulty joining the company. Yet, in the modern and character dance companies in Cuba, dark-skinned individuals predominate (Fitzpatrick skin type V–VI).

Hamlet Betancourt León believes that “social discrimination” exists in Cuban ballet. (

León 2009, p. 102;

2010, pp. 373–74). Despite the fact that, during admission to the ballet school, skin color holds no meaning, ballet has remained a sphere where lighter shades of skin have privileges.

So, what is going on? Is this really racial prejudice, or something else?

1 2. A Short History of the Black Struggle for the Right to Dance on Professional Stages

The first ballets with the participation of black-skinned performers were presented in New York in the 1820s. Among a range of theatrical initiatives addressed to the free African American population of New York (slavery was eliminated in New York in 1827), a notable event was the founding of the “African Grove Theatre” in 1821, one of the organizers of which was the African American actor James Hewlett, a famous performer of Shakespeare characters (

Figure 3a). Another famous actor in the company was Ira Frederick Aldrigew who, after 1858, travelled to Russia more than once and successfully performed in “Othello”, “Macbeth”, “King Lear”, and the “Merchant of Venice” (

Figure 3b). The repertoire of the African Grove Theatre contained several ballets, and one balletmaster invited from France worked there for a time (

Shafer 2002, pp. 30–32). The first attempts to create “black ballet” were not attempts to transfer European images to the stage, but pursued the objective of finding a specific language of dance expressing the “cultural dualism and even the cultural hybrid of America’s black-skinned population” (

McAllister 2003, p. 70). During the 1820s and 1830s, several African American theatrical companies arose, but they did not last for long.

The start of the 20th century was an era with a powerful wave of disseminating classical ballet across the world associated with the touring of Russian stars and the “Russian Seasons”, and then in connection with the emigration of many Russian artists and balletmasters. In the 1920s, the Harlem Renaissance took place, which brought the creation of a special literary school, theatrical movement, and a period when a whole constellation of highly educated and artistic personalities of Afro-American heritage appeared. This was also the beginning of research leading to the recognition of the great influence of African Americans in US culture (

Atlas of Literature 2005, pp. 190–95). In the 1920s, the first black dancers appeared in ballet classes, and their numbers steadily increased. At the time, the impression that blacks had no traits suitable for ballet predominated; they had “joints that were too stiff, heavy jumps, hyper-extended knees and weak legs” (

Defrantz 1996, p. 179).

In the 1930s and 1940s, several theatre companies arose containing exclusively African Americans. For example, the “New Negro Art Theater Dance Group”, created in 1931 by Hemsley Winfield; “Eugene Von Grona’s American Negro Ballet”, created in 1937 by the German dancer and choreographer; and the “Negro Dance Company” formed in 1940 by Wilson Williams. Their repertoires contained their own productions inspired by modern dance, reconstructions of African rituals, and ballets based on the “Russian Seasons” motif, for example, “Firebird” to the music of Igor Stravinsky. All of these beginnings did not last long and were supported, essentially, by the selfless devotion of their founders (

Defrantz 1996, p. 180).

In the 1930s, Katherine Dunham—a dancer, choreographer, anthropologist, and researcher—began her activity regarding the dancing culture of Caribbean nations and the active struggle for the civilian and cultural rights of the “Afro-American diaspora” (Dunham’s phrase). The main weapons in this fight were dance, ballet class, and the stage: “in dance, ideas and actions are not separate, in dance, ideas are action” (

Dee Das 2017, p. 7). In 1944, Katherine Dunham founded a dance school in New York, but not in Harlem, where the black population traditionally predominated, rather in the theatrical Broadway neighborhood, and this fact alone she viewed as overcoming segregation in the New York dance world (

Dee Das 2017, p. 7). Katherine Dunham created her own original method of teaching dance, combining classical ballet training, Afro-Caribbean dancing styles, Eastern martial arts, Indian classical dance, and yoga (

Dee Das 2017, p. 19). The tours of Dunham’s company in the 1950s and 1960s across North and South America, Europe, Australia and New Zealand, and Southeastern Asia became soft power for the anti-colonial movement and “encouraged artists in decolonizing states to embrace their Africanist and indigenous cultures” (

Dee Das 2017, p. 124).

After World War II and in the 1950s, the possibilities of African American dancers expanded somewhat, especially during Harry Truman’s presidency. In 1946, Joseph Rickard, a student of Bronislava Nijinsky, created the “First Negroid Classical Ballet” in Los Angeles. The company, at first amateur and later professional, existed for ten years and successfully toured across the USA, Canada, and Europe, but encountered many racial prejudices and limitations. There were modern productions set to the classical music of Bach, Chopin, Mendelsson, and Saint-Saens in the repertoire of the company, as well as modern choreography and ballets about the life of African Americans (

Blodgett and Hodson 1996, pp. 79–82).

George Balanchine, a talented American choreographer, held an active position in the issue of black dance and black dancers. One of the sources of George Balanchine’s choreographic style was the Afro-American (black) dance: “Balanchine has been classicizing movements from our Negro and show steps” (

Banes 1994, p. 55). The choreographer worked with African American dancers and show productions, collaborating with Katherine Dunham.

In 1951, Janet Collins became the first Afro-American prima ballerina at the Metropolitan Opera in New York. In 1955, African American Arthur Mitchell became a principal dancer at New York City Ballet.

In 1969, along with Karel Shook, Arthur Mitchell founded the Dance Theatre of Harlem, the first permanent company of black ballet dancers which successfully operates to this day. This theatre finally buried the myth about the absence of inborn traits in African Americans for classical choreography. A milestone event in New York’s cultural life was the company’s production of “Giselle” by balletmaster Frederick Franklin (1984), which was maximally close to the original choreography by Jean Corrali and Jules Perrot. This so-called

Creole Giselle received polar reviews from the critics: from complete rejection to admiration, and not only for innovation but for its mastery and aesthetic perfection (

Casey 2006).

Mitchell recalled: “At first, I went on record as saying I would never do

Swan Lake or

Giselle or any of the other classics,” he recalls. “I said I was into the neo-classic[al] school. But as time went on, I realized I was shortchanging the dancers by depriving them of this opportunity. So, when we decided to do Act II of

Swan Lake, I had to find another way of doing it. Traditionally known as the ‘white act’ of the ballet, it seemed silly for a black company to do a white act. Well, we changed the color of our tights to tan and brown. In that way, the line looked pure, longer, correct. As for

Giselle, when we mounted our full-length version, we set the action in the American South. So, it became a

Creole Giselle. It was never a question of changing the steps—only the sets, the costumes, the intonation and the approach” (

Gruen 1989).

During 1960s and 1970s, national ballet theatres were created in many Latin American countries, and the 1990s to 2000s classical ballet theatres appeared in South Africa, where all of these issues arose once again. This period is also associated with a growing quantity of academic studies on the problem of the “white ballet” and “black dancers”, methodologically relying on the conception of orientalism and cultural studies (

Post-Apartheid Dance 2012). An important methodological focus of this research direction is the impression of “whiteness” as a social construct. As Brenda Dixon Gottschild observed, in the world of dance, ballet remains the last bastion of the idea of whiteness as supreme (

Dixon Gottschild 2003, p. 131).

According to McCarthy Brown, despite the serious shift in the area of the admission of black-skinned dancers to classical ballet, for them a “glass ceiling” exists that is supported by a series of preconceptions not only in society as a whole but within the African American community. McCarthy Brown emphasizes, first of all, double consciousness, that is, the understanding of the lack of congruence between the expectations of the two types of viewers and colleagues. On the one hand, these dancers must dance so as to overcome strong stereotypes of black bodies in classical ballet, and on the other hand, they must inspire African American society and demonstrate that they have overcome social barriers (

McCarthy-Brown 2011, pp. 390–93). Secondly, this concerns the historical accumulation of images of black women (“controlling images”) that contradict the female ideal cultivated in classical ballet. Unlike the “fragile, submissive and demure” heroines in classical ballet (

McCarthy-Brown 2011, p. 389), the African American woman is a “strong black woman” (

McCarthy-Brown 2011, p. 394). The black-skinned man as a hero is more acceptable since he does not break the stereotypes of the feminine ideal. Furthermore, in the ballet world, there is a high demand for men, such that black men have an easier time creating a career in the world of ballet. Last and thirdly, there is “colorism”, the varied shades of skin among African Americans as a direct result of the slave-owning era, and the preference for light shades of skin before darker shades within an ethnic or racial society. Dancers with lighter shades of skin find themselves in more advantageous positions among African Americans (

McCarthy-Brown 2011, p. 397).

3. The Dance of Alicia Alonso and Cuban Identity

The face of the BNC became Alicia Alonso, who achieved international fame, and many answers to the questions set forth by us are found in her biography (more precisely, in the fates of the triumverate Alicia, Fernando, and Alberto Alonso), the founders of the Cuban school of classical dance and the ballet company.

Above all, we ask the question whether Alicia Alonso was familiar with the problem of the black and colored people’s struggle for the right to be professional dancers.

Alicia Alonso’s

2 childhood and youth (she was born in 1920) took place during the period of the blossoming of the Cuban avant-garde, highlighting the images of national (aboriginal and African American, Caribbean) identities. The Alonsos were familiar with many workers in the Cuban avantgarde and found themselves inside this process.

Alicia and Fernando Alonso, already members of Ballet Theatre in New York, danced the leading roles in the ballet

Dioné (premiere 6 March 1940, in Havana) as invited soloists. Under the pressure of the Pro-Arte Musical Society, which financed the production, the idea to set a ballet on the subject of Cuba’s aboriginal past was greatly transformed. The libretto was altered considerably: two young Taino aborigines, whose love story comprised the subject, became a story of European noblemen, where mythological midget

güijes became fairies, and a tropical forest turned into a French garden (

Tomé 2011, pp. 72–74).

The first genuine national ballet in Cuba was

Before the Dawn (composer Hilario González, choreography by Alberto Alonso, and libretto by Francisco Martínez Allende, premiere 25 May 1947, Havana). Alicia Alonso danced the main role of Chela, a widow with tuberculosis living in a typical overcrowded tenement building in Colonial Havana. The owner plans to evict her and she decides to commit suicide by setting herself on fire. As Lester Tomé wrote, “The Cuban character of

Antes del alba was unmistakable… Although the Alonsos and the rest of the performers were white, the ballet’s setting and display of Afrocuban dances reinforced the fact that its characters were black” (

Tomé 2011, pp. 77–78).

Primarily whites and children from wealthy families studied in Cuban ballet schools prior to the 1959 revolution. Light-skinned individuals included the famous Cuban ballerinas Loipa Araújo, Aurora Bosch, Josefina Méndez, and Mirta Plá (the so-called “four jewels” of Cuban ballet) (

Haskell 1979, p. 329). Alicia Alonso was well acquainted with the difficulties encountered by African Americans who wanted to study ballet and dance in the theatre, and helped many of them.

In the 1940s, prior to the founding of her own ballet theatre in Cuba, Alicia Alonso studied and worked in New York with Lincoln Kirstein and George Balanchine; their ideas about creating American ballet gave birth to the “debate over questions of cultural appropriation, race and aesthetics, and creative ownership in the wider history of Broadway as well as Balanchine’s own work with black dance and dancers” (

Steichen 2019, p. 232). From 1955 to 1959, Alicia and Fernando Alonso worked in the Ballets Russes de Monte-Carlo, at the same time as Raven Wilkinson, the first dark-skinned soloist, appeared in the company.

When asked whether she had encountered racism, Alonso answered: “It was impossible for many to imagine a Latin woman dancing classical ballet. They thought that Latinas, and especially Cuban women, could only dance the rumba” (Quoted after:

Tomé 2011, p. 119). When Alicia Alonso guested in Europe with Theatre Ballet in 1946 and danced

Giselle and

Swan Lake, the viewers could not believe that a Latin American was performing. “In England, a critic even asked me how I had the courage to dance

Giselle.” (Quoted after:

Tomé 2011, p. 120).

In other words, the Alonso triumvirate along with others in the arts community fought to overcome stereotypes in relation to Latin American dancers, and fought for the representation of Afro-Cuban identity. So, what is the source of racial discrimination in Cuba?

4. Alicia Alonso’s Choice

The fight of dark-skinned “colored” individuals for the right to dance professionally had two strategies. The first emphasized the black identity which simultaneously represented a culture of downtrodden, exploited classes. This was the path of Katherine Dunham and many others in the African American movement. Ballets such as

Before the Dawn which Alicia Alonso danced reflected this. Such was the Cuban program for mass teaching the Rumba and turning the Rumba into a marker of class and ethnic solidarity. However, as Yvonne Payne Daniel demonstrates, the rumba represents, “African identity which is still avoided in many instances of daily and official life, irrespective of official efforts to the contrary and irrespective of popular sayings that refer to ‘a hidden grandmother,’ suggesting that most Cubans have a profoundly intimate African heritage” (

Daniel 1994, p. 80). And even in Balanchine, as Sally Banes noted, Arthur Mitchell and Mel Tomlinson represented the black identity, they “played stereotype roles, either exotic or nonhuman, like the African Oni of Ife in

The Figura in the Carpet, Puck in

A Midsummer Night’s Dream, Pluto in

Persephona, and Hot Chocolate in

Nutcracker” (

Banes 1994, p. 69).

The second strategy was inclusion on equal ground in the domain of high (European) culture, which meant not so much an ethnic or regional culture, but a domain of eternal truths that was “beyond history and nation” and that concerned absolute artistic values. In other words, the art of classical dance was understood to be a sphere of the highest achievements in dance culture, as a domain of perfection.

Alicia Alonso, first for herself and then for the Cuban ballet school, chose the second strategy.

She set the goal for herself of achieving success in the repertoire of Romantic ballets of the 19th century. Although she performed neoclassical and modern choreography, her fame and her myth are associated with the roles of Odile, Sylphide, and Juliet. And especially with Giselle.

Alicia Alonso debuted in

Giselle in 1943 at American Ballet Theatre, and in 1946, the European public saw her in this role for the first time. It was her star role. She brought it international fame, and critics and ballet journalists alike stated that the role of Giselle ensured Alicia Alonso’s place in history. Lester Tomé defined Alicia Alonso’s performing style as the effect of a double identity: “The paradox of Alonso’s simultaneous embodiment of Cuban sensibility and a European aesthetic turned into an attitude that attempted to be truthful to the factors in a relationship that had hitherto been seen as irreconcilable. Alonso achieved complete identification with the European romantic style and, at the same time, channeled her national identity through her dance; she was truthful to both a European and a Cuban legacy” (

Tomé 2007, pp. 267–68).

As Lester Tomé noted, Alicia Alonso undertook efforts to strengthen her status as a legendary performer of Giselle. She ensured that her role as Giselle during her career was recorded in popular and academic publications (

Figure 4). The anniversary of the premiere was widely celebrated in Cuba, photobooks were printed, and gala concerts were held. In 1965, the ballet was filmed, and in 1980 (at the age of 60) she danced

Giselle with Vladimir Vasiliev in the Bolshoi Theatre (Gran Teatro) of Havana.

When the “Alicia Alonso Ballet” company was formed in 1948, the first production performed was

Giselle by Alberto Alonso, and two years later, Alicia Alonso’s school opened. By will or by necessity, the bets were placed on the classical repertoire as it corresponded to the expectations of Havana’s bourgeois public who paid money for it. In order to push forward Alberto Alonso’s experimental production within the framework of Pro-Arte, romantic ballets needed to be performed (

Tomé 2011, pp. 101–102).

During the year of the socialist revolution in Cuba (1959), Alonso was 39 years old—an age when the ballet career is in decline. The last few years before the revolution, due to difficulties in Cuba, Alicia and Fernando worked in America and in Europe. And in 1959, Alonso received an invitation from Fidel Castro to return to the island. The revolutionary rhetoric promised a bright future. But the reality of the revolution meant constant instability and unclear prospects. It meant either gaining or losing everything. It was not clear how long Alicia could still dance on the American stage and whether she could manage to open her own theatre. But Alonso returned to socialist Cuba, and the Alicia Alonso Ballet—now the BNC—received state support and later international fame.

In the 1960s, there were no black dancers in the BNC, but they appeared at the end of the 1970s. Among the first was Caridad Martinez, a graduate of the Cuban National Art School in Havana. By 1970, the Camagüey ballet had only one black ballerina (

Tomé 2017, pp. 11, 15). As Tomé demonstrated, ballet in Cuba remained classical and became a means of support for the official ideology and communist conception of labor. First, thanks to the formation of the image of ballet dancers as people who perform physical labor. For example, in the “didactic performance” format on manufacturing, when during the concerts one of the artists explained production and its story, and talked about ballet training and how much work and physical strength ballet dancers put into their art. These concerts drew common workers and ballet dancers together, embodying a singular proletariat identity. In addition, in the 1960s, ballet dancers, ballet masters, and ballet students among with many Cubans, participated in the “agricultural crusade” (

Tomé 2017, p. 13) to plant and harvest coffee, cane sugar, and citrus fruits without stopping ballet classes and rehearsals or postponing any premieres. Further, “The presence of the white artists in the fields suggested fluidity between the historically racialized identities of ballet dancers and sugarcane cutters” (

Tomé 2017, p. 15). Second, the BNC became a formal representation of the idea of the new individual in the post-revolutionary era, whose image included tireless work and daily self-sacrifice. The image of the dancers’ hard-working nature was part of the propagandist discourse, the aspiration of ballet dancers to technical and artistic perfection demonstrated a path of achievement of maximum results in one’s work; discipline, responsibility, and respect for authority, required for the functioning of a ballet theatre as a whole, reflected the standards that the government was trying to implement (

Tomé 2017, p. 17). Third, ballet dancers embodied the image of the New Woman working to benefit the country and not isolated in housekeeping duties, but a woman who is simultaneously attractive (

Tomé 2017, p. 19). The brightest example of this was Alicia Alonso. In her case, the image of the selfless toiler overcoming misfortunes and obstacles on the path to success was supplemented with the history of an ocular disease which she overcame and returned to her profession to become a prima ballerina (

Tomé 2017, p. 21). “Even if this chapter of Alonso’s career predated the Revolution,

Bohemia (Cuban magazine) appropriated the story in its discursive production of the New Man/Woman’s epic identity.” (

Tomé 2017, p. 12) (

Figure 5a,b).

In 1964, at the First International Ballet Competition in Varna (Bulgaria), young Cuban dancers won a slew of awards, and their bright performance style was a new revelation. Thereafter followed awards at the IV International Festival of Dance in Paris in 1966, which the famous ballet critic Arnold Haskell called a “Cuban miracle”. Since the return of Alonso to Cuba and the start of her directorship of the National Ballet School, only 5 years had passed (

Sakamoto de Miasnikov 2018). Cuban ballet under Alonso’s directorship came out victorious in an art form which, according to tradition, belonged to Europe. Along with this, during the international tours of the Cuban Ballet, Alicia herself danced

Giselle,

Swan Lake,

Coppelia, and

Don Quixote, thereby preserving the position of Cuban ballet as the preserver of the classics (

Figure 6).

Of course, there are dark-skinned and colored Cuban ballet dancers who became wonderful performers of the classical repertoire. But there are few of them. They include Caridad Martínez (born in 1950), who performed the pas de deux from Act I, Scene 2 and Act II of

Swan Lake. Her repertoire includes Princess Aurora, Princess Florine, and the fairies from

The Sleeping Beauty, the Prelude from

Les Sylphides, Myrtha in

Giselle, the Grand pas de deux from

Don Quixote and

Le Corsaire, Swanilda in

Coppelia, and Lise in

La Fille Mal Gardée (

Figure 7a,b). In addition, she performed many coryphée roles and the entire classical repertoire in the corps de ballet (

Martínez 2021). In 1985, Caridad Martínez left the BNC, founding, along with Rosario Suárez, Amparo Brito, and Mirtha García, the innovative “Theatre Ballet” aimed at modern choreography, Caribbean dance forms, and the Carnavale aesthetic (

Martínez 2009).

Catherine Zuaznabar (born in 1975) was the second dark-skinned ballerina to perform the role of Odette-Odille in

Swan Lake. But her further career was connected with modern choreography, and she later became a soloist with Maurice Bejart’s company (

Zuaznabar 2021) (

Figure 8a).

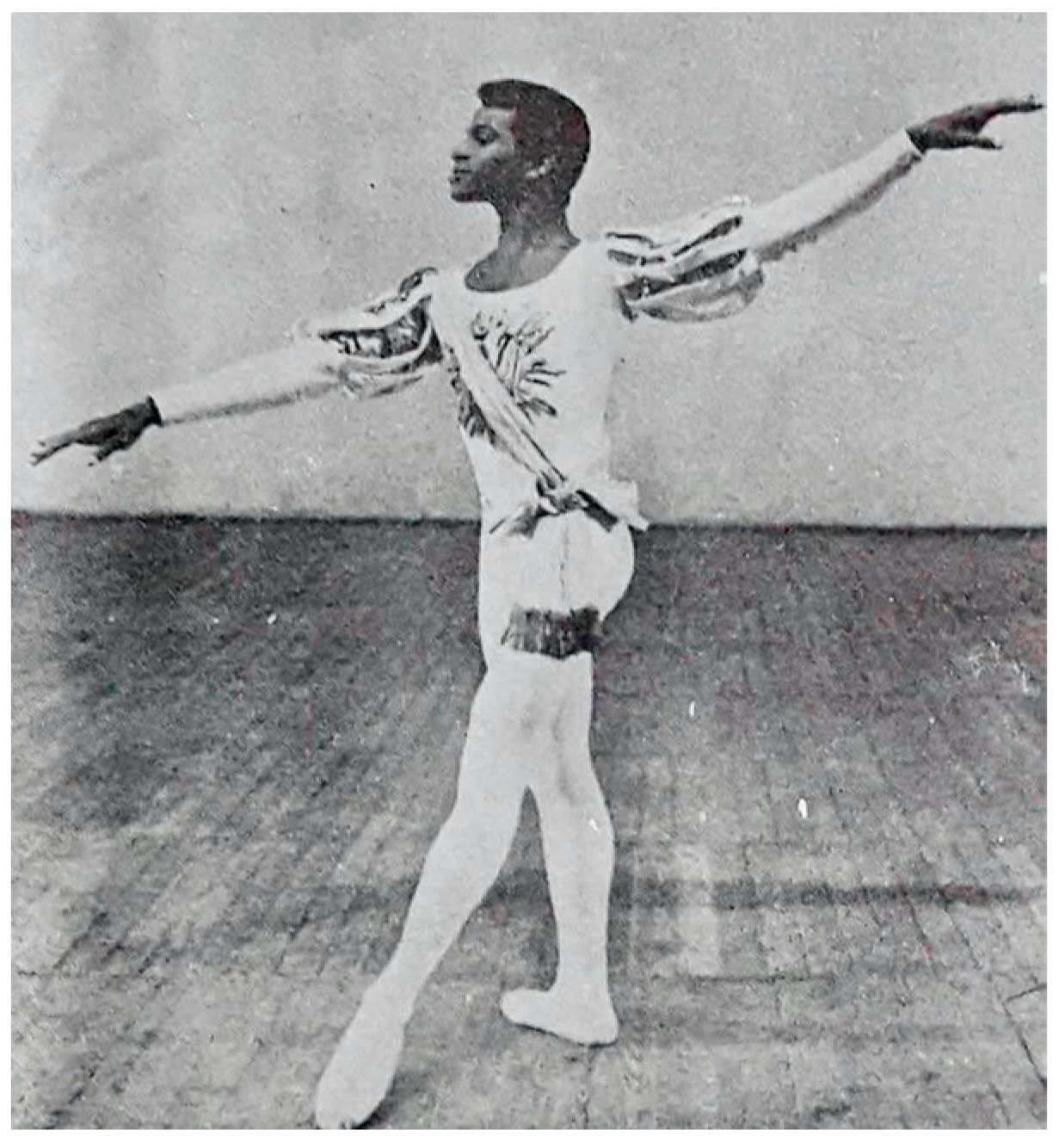

Andres Williams Dihigo (born in 1952) was a black dancer who graduated from the Cuban National Arts School and began his career in 1970. In 1986, he became a principal at the National Ballet of Cuba (

Figure 8b). The holder of numerous prizes and diplomas at ballet competitions, he danced the classical repertoire and had the

emploi of a prince. As Pedro Simon noted, “is there a dancer more deserving of the role of Prince than Andres Williams, with his nobility and style? No, and you cannot find anyone more black than he, but nonetheless, he is a classical ballet dancer” (

Alonso 1986, p. 41) (

Figure 9).

Carlos Acosta, (born in 1973) became a principal dancer with numerous ballet companies, including the English National Ballet, the Royal Ballet, and American Ballet Theatre. He performed many star roles in the male repertoire including Polovtsian Dances from the opera Prince Igor, and Spectre de la Rose, La Bayadère, Don Quixot, Frederic Ashton’s Romeo and Juliet, and Ben Stevenson’s The Nutcracker. Manuel Carreño, another black graduate from Cuba’s National Ballet School, worked in parallel with Acosta at the Royal Ballet.

On the one hand, Cuban black ballet dancers achieved success in other theatres. On the other hand, with the example of Carlos Acosta, Lester Tomé poses the question of institutionalization of multiformity in the ballet theatre starting in the 1990s. The invitation of Cuban (as well as Latin American and Asian) dancers to theatres in Great Britain, Europe, and the USA changed the impression of ballet as a form of exclusively European physicality. Along with this came the glamorization of racial and ethnic variety as the implementation of a political strategy of multi-culturalism (

Tomé 2019).