Abstract

The collective ritual of building one-day votive churches (obydennye khramy) was practiced in the European north of Russia between the late 14th and 17th centuries. The product of a syncretism between Orthodox Christianity and native folklore, the ritual’s purpose was to deliver the community from epidemic disease. One-day churches were built of freshly cut logs, on virgin ground, in a prominent place, such as a town square or crossroads. According to local belief, votive objects made from natural materials were simultaneously temporary and eternal; this paper interrogates how one-day churches fit this model. Obydennye khramy were ephemeral structurally, processually, and circumstantially. These were simple, rudimentary votive structures, not built to last nor substitute established churches. By condensing into a single day all of the traditional steps of church-building, the ritual prevented the church from growing old before completion, ensuring its purity through its newness. Built under threat of pestilence, obydennye khramy had the function of realigning the progression of time, putting an end to the period of disease, and thereby allowing humans to fleetingly triumph over natural forces. Obydennye khramy were enduring as objects of intercession, as governance instruments, and in their subsequent representations in the written word and urban topography. Votive churches were spatial icons, mediating between humans and the cosmos and returning to nature as they decayed. The ritual itself, led by religious and secular authorities, performatively reinforced social hierarchies. Obydennye khramy were immortalised in chronicle narratives and occasionally replaced with stone churches, some of which survive today.

1. Introduction

“The same autumn there was a great plague in Novgorod; all this came upon us because of our sins; a great number of Christians died in all the streets. And this was the symptom in people: a swelling would appear, and having lived three days [the man] would die. Then they erected a church to St. Afanasi in a single day, and Vladyka loan, Vladyka of Novgorod, consecrated it, with all the Igumens and priests and with the choir of St. Sophia; so by God’s mercy and the intercession of St. Sophia, and by the blessing of the Vladyka, the plague ceased.”The Novgorod First Chronicle(Michell and Forbes 1914, p. 164)

The chronicle record for the year 1390 is the earliest account of a one-day votive church (obydenny khram) being built in response to an outbreak of the Black Death in the medieval Russian city of Novgorod. The chronicler relates that this impressive feat was completed within a single day by the men of the city and overseen by the archbishop (vladyka), along with the entire institutional hierarchy of Novgorod’s St. Sophia cathedral (Figure 1). The ritual of the one-day church was practiced in the European north of pre-Petrine Russia between the 14th and 17th centuries. One-day churches were built of freshly cut logs, on virgin ground, in a symbolically charged location, such as a town square or a crossroads. The accelerated, continuous process of fabrication was believed to have miraculous properties, creating a magical barrier that could protect the city from supernatural evil forces associated with epidemic disease.1

Figure 1.

One-day church ritual in Novgorod, 1390. (a) Construction; (b) consecration. The Illustrated Chronicle of Ivan the Terrible, Osterman Volume II. Library of the Russian Academy of Sciences.

According to local belief, votive objects made from natural materials were simultaneously temporary and eternal. This seemingly paradoxical condition will be discussed in this paper, using textual accounts of one-day church construction from the Novgorod First Chronicle and the Pskov Third Chronicle and miniatures from the Illustrated Chronicle of Ivan the Terrible.2 The one-day church, as a votive construction built with tree logs, may be understood as an ephemeral icon created from natural materials through collective ritualistic performance. Aspects of ephemerality in the one-day church are discernible in the brevity of the ritual process and in the limited lifespan of the physical structure, whose rudimentary design was not conceived for durability. Aspects of permanence are evident in the processes of the one-day church’s translation onto paper and into stone, into myth and into monument.

The one-day church demonstrates how the category of imaginary architecture could encompass material structures in addition to two-dimensional sketches and paper-based models. The one-day church was a magical object, capable of mediating between the earthly and supernatural realms during the brief period of its fabrication. Following the ritual, the ways in which these churches were documented on paper elevated them into hagiographic narratives of history via the literary form of the medieval chronicle.

2. Climatological Vulnerability of Medieval Novgorod and Pskov

Before elaborating on the characterisation of the one-day votive church as an ephemeral icon, it is worth considering the environmental and climatological context within which this ritual developed. Located in present-day northern European Russia, inland from the Baltic Sea and the Gulf of Finland, the medieval towns of Novgorod and Pskov were prosperous mercantile economies linked to European and Asian trade routes via the region’s ample network of rivers and waterways (Halperin 1999; Arakcheev 2014; Birnbaum 1992). Reconstructions of medieval climate patterns reveal a short, cool growing season with unpredictable precipitation which made the area prone to crop failures and subsistence crises (Huhtamaa 2015). From the 12th century onwards, chronicles record recurrent bouts of weather anomalies, failed harvests, famine, and epidemic disease in Novgorod and in Pskov.3 It is this conjuncture of urban wealth and climatological vulnerability that perhaps laid the conditions for such a labour- and resource- intensive ritual as the one-day church.

Due to its spatial progression across Europe from the Black Sea basin, the Black Death appeared in northern Russia relatively late, but its effects were particularly devastating once it arrived. The Pskov chronicler was aware of the Black Death’s spread through Europe as early as 1349, though the “terrible plague” did not actually reach Pskov until 1352 (Savignac 2016, pp. 62–64). The chronicle’s apocalyptic description of that year’s events distinguishes the Black Death from earlier epidemics in terms of its deadly nature as well as the intense religious fervour it inspired. The fatalities overwhelmed the clergy’s capacity to perform proper funerary rites, necessitating the burial of corpses in mass graves outside of cemetery grounds. Many of Pskov’s panicked residents were said to have taken holy orders or donated their earthly possessions to the church, hoping to secure their eternal salvation as they “abandoned their bodies to the grave.”

From that first outbreak of Black Death in 1352 until the end of the 15th century, Russia would experience a new wave of plague on average every five years. Novgorod and Pskov were at the center of its territorial incidence, made particularly susceptible by their urban density and cross-border contacts (Alexander 1986, p. 249). The fragility of population health due to food insecurity was a compounding factor (Figure 2). The Novgorod chronicle described a famine diet of boiled tree bark, moss, and snails; in especially desperate circumstances, people ate companion animals or engaged in cannibalism and necrophagy (Michell and Forbes 1914, p. 76).

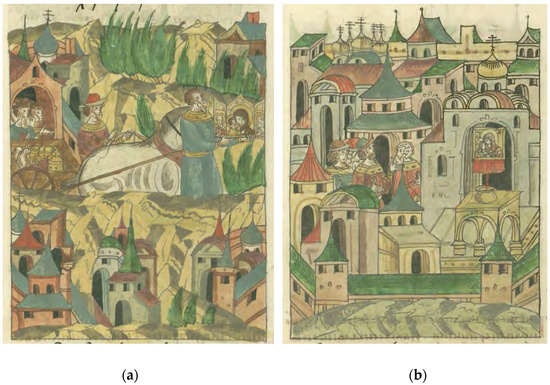

Figure 2.

Subsistence crises in Novgorod. (a) Crop failure, 1412; (b) plague, 1417. The Illustrated Chronicle of Ivan the Terrible, Osterman Volume II. Library of the Russian Academy of Sciences.

The first one-day church was recorded in Novgorod in 1390, the same year that the Pskov chronicle told of a Black Death outbreak “such as had never been seen before. From five to ten corpses were buried in a grave dug for a single person” (Savignac 2016, p. 70). The quarter-century period that followed was the deadliest; plague struck northern Russia once every two years, while food system resilience deteriorated, resulting in prolonged famines and acute food shortages.4 It was precisely at this difficult time that the greatest number of one-day churches were built. The one-day church ritual thus emerged not as an immediate response to the advent of the Black Death, but during the subsequent waves of disease when the plague had become endemic and the human suffering was at its apex.

In Russia, as elsewhere in medieval Europe, contemporaneous accounts interpreted the Black Death as divine retribution for the people’s sinful ways. An understanding of disease as a collective punishment implied a societal response of collective atonement. Expiatory plague responses were a widespread feature in European religious cultures of the 14th century, recorded in art and architecture through phenomena such as plague saints and memorial chapels. The one-day church, however, is a type of plague response that is unique to northern Russia, arising from a distinct confluence of spiritual and pragmatic factors that will be considered in the following sections.

3. The One-Day Church as an Ephemeral Icon

Medieval Russian chapels were religious structures designed for divine services without a priest, small in size, and often built at the initiative of common people. Ethnographer A.B. Permilovskaya considers the chapel to be “the most vivid manifestation of northern Russian traditional culture and its wooden architecture” (Permilovskaya 2010, p. 248). Chapels were built in natural–sacral complexes, positioning the religious structure in relation to a landscape feature, such as a forest grove, river, or roadway that would create a natural boundary delimiting the sacred space. A chapel was believed to produce an intimate encounter with the divine, a space where prayers could be heard and answered quickly. Votive chapels were a particular type of chapel built in response to distress or crisis situations, either preemptively to ward off a potential danger or seek relief from ongoing circumstances, or subsequently, as an expression of gratitude for deliverance obtained (Permilovskaya 2010). The practice began almost immediately after Christianisation; the first recorded instance of a votive chapel was the Church of the Sacred Transfiguration built in 996 by Vladimir, Prince of Novgorod and Grand Prince of Kyiv, following his escape from Pecheneg invaders at Vasylkiv near Kyiv (Antonov 2022, p. 53). According to the Rus’ Primary Chronicle, construction was accompanied by “a great festival” lasting eight days. Three hundred kettles of mead were brewed for the consumption of boyars, military lieutenants, and city elders, and Vladimir distributed a sum of three hundred hryvnias to the poor (Hazzard Cross and Sherbowitz-Wetzor 1953, p. 121). Grand Prince Vladimir’s personal vow of gratitude also became a memorable occasion for the community at large.

The one-day church is a subtype of the votive chapel built in response to epidemic disease. Its defining feature is that all the traditional steps of creating a religious structure—groundbreaking, construction, and consecration—which in medieval Novgorod typically required between two and five years for stone churches,5 were condensed into the space of a single day. The process unfolded as follows. To begin with, an authority figure directed the people to build a one-day church. The order might come from a bishop, a prince, or a combination of the two. This initial step was the only part of the process that could occur outside the “one-day” timeframe, sometimes preceding the other events by a few days to a week. On the day in question, a construction site was chosen by religious hierarchy. This location had to be virgin ground, in other words, a new space where no structure had previously existed. Often, this site was a space of communal activity, a town square or a crossroads. Common people collected the building materials and these, too had to be new. Fresh logs were cut from the forest and brought into the town. Then, the ceremony of breaking ground took place in the presence of the bishop and prince. At this point the foundations of the church were marked, with its altar oriented to the east. Construction would begin immediately and proceed in a continuous, uninterrupted manner throughout the day and into the night. That same evening, the ceremony of consecration would take place, presided by religious leadership. The church would be dedicated to a manifestation of divinity or to a saint, in the process assuming a votive character. The supernatural personalities to whom one-day churches were consecrated will be further discussed in subsequent sections.

Chronicles record twenty-two instances of one-day churches being built in the northern Russian towns of Novgorod, Pskov, Tver’, and Torzhok between the years of 1390 and 1552. Chronicle narratives trace a causal linkage between the proper completion of the ritual and the subsequent abatement of the plague.6 There are accounts of one-day churches further south, in Moscow and its environs from the late 15th century to the mid-17th century. Given that the earliest documented instance of a Muscovite one-day church occurred nearly a century later than the first record in Novgorod, it can be surmised that the ritual was diffused southward following Moscow’s territorial annexation of Novgorod in 1478 and of Pskov in 1510.

Because of their ritual character, one-day churches were small, rudimentary structures. Though no one-day churches have survived, ethnographic work conducted by D.K. Zelenin in northern Russia in the early 1900s documents intergenerational memories of these structures. The size of one such chapel, in the village of Yekaterininsky on the Vyatka River, was approximately one and a half square fathoms (sazhen). A tree stump was used for its altar, and the royal doors were made from “two simple boards, tied with string” (Zelenin 1911, p. 16). Rather more similar in design to a barn than to a parish church, one-day churches consisted of an octagonal or rectangular base made from interlocking logs with a low-slung tented roof, a simplified variant of the enclosure (klet’) chapel type prevalent in northern Russia at that time (Figure 3).7 Given their simplicity, one-day churches had a limited lifespan, often no more than 25 years (Permilovskaya 2010, p. 250). The one-day church with the greatest longevity stood for 150 years, which is nonetheless far shorter than the lifespan of a traditional wooden church that could generally survive for 400 years (Permilovskaya 2011, p. 294).

Figure 3.

Construction of “Saviour-Vsegradsky” (Spaso-Vsegradsky) one-day church in Vologda, October 1654. Print in the collection of Spaso-Vsegradsky Cathedral. (Anonymous 17th c.).

The extant structure that most closely resembles the architecture of a one-day church is the Church of the Resurrection of Lazarus, a rectangular klet’ church built in the late 14th century at Saviour monastery in Murom, on the Oka River, by missionaries from Novgorod (Figure 4). Thought to be the oldest surviving wooden religious structure in Russia, the Church of the Resurrection of Lazarus is preserved at the Kizhi Island Open-Air Museum of wooden architecture. This structure displays the technique of building with interlocking logs, as well as the form of the tented roof, as they would have been practiced in Novgorod at the time.

Figure 4.

Church of the Resurrection of Lazarus, northeast view, at the Kizhi State Open Air Museum of History, Architecture, and Ethnography. Photograph by William Brumfield in the collection of the Library of Congress (Brumfield 1988).

Due to its folkloric character, the one-day church was not a subject of study in imperial Russia before the late 19th century, when it began to be studied as an ethnographic phenomenon. By that time, the ritual was no longer being practiced, so these early studies were of a historical character. More recent studies have engaged with the one-day church as a phenomenon of hierotopy, a concept developed in 2000 by Alexei Lidov. Hierotopy, broadly, is the creation of a sacred space as a staging point for an encounter with the supernatural. A hierotopical project produces a single sacred whole, a unique spatial image woven together from various elements of religious and liturgical practice; these elements include permanently visible objects as well as ephemeral sensory phenomena (Lidov 2014). A crucial feature of hierotopical phenomena is the participation of the beholder in the spatial image.

There are several principles of Eastern Christian hierotopy as identified by Lidov (2014) that are relevant to the one-day church ritual. Eastern Christianity conceptualised the church as a moving spiritual substance that could be temporarily displayed and re-created on public streets and squares by means of religious rituals. These liturgical performances temporarily transformed urban landscapes into spatial icons, emanating into the environment and entering into a living relationship with the beholder. Another characteristic feature of Orthodoxy was the intention to re-create in smaller form an iconic concept of a larger sacred space. Finally, hierotopical phenomena in Eastern Christianity were accompanied by textual sources creating a hagiographic image of the authority figure who oversaw the creation of a sacred space. As a collective religious performance occurring in the public space, the one-day church ritual can thus be considered a spatial icon of an ephemeral character, reproducing in miniature the traditional process of church construction, and involving the entire town as beholder-participants.

4. Disaster Rituals in the Russian Chronotope

To understand how a tangible structure such as the one-day church could be considered an ephemeral icon, it is necessary to explore the complex perception of time in medieval Russian culture and the relationship of this perception to religious practice. Novgorod and Pskov were part of the Russian North, a unique cultural space that emerged on the outskirts of the Kyivan state.8 The Russian North can be defined as a zone of close contact among multiple ethnic cultures, settled and colonised by ethnic Russians as a frontier environment and subsequently becoming a preserve of ancient Russian culture (Permilovskaya 2011, pp. 291–92). The Russian North had a rich folk culture arising most notably from the interaction of Russians with Finno-Ugric peoples, and local religious practice was rooted in regional conceptions of the human relationship with the natural environment. These conceptions were performatively represented through a broad array of collective rituals oriented towards the natural world, based on the organisational foundations of localised self-governance and the capacity for spontaneous mass mobilisation (Terebikhin 2016, pp. 21–22). A year in the life of a medieval northerner would have been structured by the performance of religious rituals, some whose dates were fixed by the liturgical calendar and others that were held episodically in response to exceptional circumstances.

Russian religious expression in the medieval period displayed a particular syncretism between Byzantine Christian liturgical-ceremonial forms and pre-Christian folkloristic conceptions of the cosmos. The coexistence of Christian and pagan worldviews is commonly called folk Orthodoxy, popular Orthodoxy, or the dual-faith phenomenon (dvoeverie) (Revko-Linardato 2015; Hilton 1991). Manifestations of dvoeverie in the Russian North were potentially a consequence of the way in which the region became Christianised. Christianity began to appear informally in the 10th century, before the Kyivan state was officially Christianised under Grand Prince Vladimir; after Christianisation, the Russian North underwent monastic colonisation, with Orthodox Christianity becoming spatially diffused via fortified monastery compounds. Outside of these compounds, pre-Christian influences persisted in autochthonous cultures.

The animistic mythologies of the Finno-Ugric peoples were formed by the realities of subsistence as subarctic hunters and fishers. Perhaps the most significant feature of Finno-Ugric myths was the preeminent role assigned to nature spirits in shaping the world; evil spirits and souls of the dead could wander the earth inflicting pestilence and crop failure, necessitating the placement of apotropaic talismans at settlement boundaries to deny entry to malignant forces (Golubovka 2006; Siikala 2002). The forest was personified as a divine being with an anthropomorphic form, while wood was associated with rebirth, new life, and the return of springtime (Paulson 1965; Siikala 2002). In the land around Novgorod, Russian fur traders had begun to tax the Finno-Ugric Komi-Zyrians by the late 11th century, a trading relationship accompanied by processes of cultural interaction and folkloric borrowing in both directions (Paulson 1965, p. 150). During the 14th century, the time of the first one-day churches, household objects and grave goods in the Novgorodian land were still commonly decorated with both Christian and pagan religious symbols, though the original magical meanings and purposes of these pagan symbols were progressively forgotten after Christianisation as their sacral symbolism was assimilated into the new faith (Brisbane 2013; Chausidis 1994). As late as the 16th century, sermons delivered in Novgorod condemned remnants of heathen customs that were said to threaten the Christian faith (Birnbaum 1988, p. 524).

Critical scholarship has called for reconsideration of traditional definitions of dvoeverie as a superficial layer of Christianity uneasily situated atop an enduring foundation of paganism. According to Levin, Rock, and others, the term’s current usage is an anachronistic and ideologically loaded construction which originated in 19th century Romanticism with its passion for folkloric ethnography and was reappropriated by 20th century Soviet historiography to advance the narrative of perennial class conflict between the popular classes and the church hierarchy; a common characteristic of these imperial and socialist historiographies is their compatibility with politicised narratives of Russian exceptionalism. As opposed to a “conflict paradigm” of opposition between authentic indigenous beliefs and elite-imposed foreign religion, dvoeverie is perhaps better imagined as a process of interaction and intersection comparable to social dynamics elsewhere in early Christian Europe (Levin 1993, p. 32). In medieval European Christianity, syncretism was typical, not exceptional, hence dvoeverie should not be understood as a uniquely or even a primarily Russian phenomenon (Rock 2009). At the same time, “specific traits of Orthodox Christianity … rendered “official” religion itself more “popular” than it was in Latin Christendom” (Kizenko 2008, p. 13).

Recent publications are correct to challenge conflictual and exceptionalist models of dvoeverie, but it is nonetheless apparent that the Russian North was especially proximate in time and space to pre-Christian traditions. The Rus’ itself was Christianised late, at the end of the 10th century. Novgorod’s Christian traders and merchants were, moreover, in regular contact with Komi-Zyrians who retained aspects of their indigenous culture and religion well after Rus’ Christianisation and Russian colonisation. In addition, the medieval Russian North was a peasant society without the urban university tradition—and the theological debates it facilitated—in western and central Europe. Dvoeverie in this environment can be understood as a localised, plural phenomenon, involving a magical, emotional conception of Orthodox Christianity whose broad characteristics were largely shared amongst the people and the clergy. One such characteristic of dvoeverie was the attribution of magical capabilities and protective powers to religious objects and images (Billington 1962, pp. 24–34; Golubovka 2006; Bogatyrev 2007). Religious images functioned as instruments for divine intercession, mediating between the supernatural realm and the human world (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Magical powers of religious images. (a) Procession of a miracle-working icon in Moscow, 1413; (b) an icon of the Mother of God bleeding in Novgorod, 1411. The Illustrated Chronicle of Ivan the Terrible, Osterman Volume II. Library of the Russian Academy of Sciences.

A worldview fundament that medieval Russian Christianity inherited from pre-Christian tradition is the perception of time and space as malleable, undivided realms, a mode of perception termed the Russian chronotope.9 Religious rituals in the Russian North centered around the barrier between heaven and earth, which was conceptualised as a permeable veil that allowed supernatural forces of good and evil to pass through it into the human world. The irruption of evil forces into the world was considered responsible for climatic anomalies, natural disasters, and crises such as pestilence and famine. Appealing for direct intervention by divine forces, via the mediation of magical objects, was the means by which humans could obtain protection from evil forces. Time, like cosmic planes of existence, was a dualistic and fluid concept. The syncretic worldview distinguished between time’s universal course in the supernatural world and its constructed form in the human world, the latter of which had to be regulated by the performance of collective rituals. The ritual act simulated a cycle of apocalypse and renewal in the natural world, thereby resetting the course of human time and realigning it with universal time.

A particular form of collective ritual was the disaster ritual, which allowed humans to obtain relief from the vicissitudes of nature by manipulating the passage of time on earth. Its goal was to artificially contract human time to put an accelerated end to the period of suffering (Baïbourine and Roty 2000, pp. 46–47; Moroz 2004). Proper completion of the ritual opened a new period in human time, realigning it with universal time, and in the process creating a protective barrier which denied evil forces entry into the new time period. The manipulation of time was achieved by creating a material object under tightly prescribed conditions; the work had to be participatory, continuous, compulsive, and uninterrupted (Tolstaya 2003). As a consequence of the special fabrication process, the object became imbued with magical attributes that made it into the physical embodiment of the desired transition from one time period to the next.

Throughout the East Slavic world, disaster rituals for protection from epidemic or epizootic disease involved the collective fabrication of votive objects from natural materials within a single day. The one-day object (obydenny predmet) was unsullied by the passage of time, such that the purity of its newness sacralised the territory on which it was created and formed an apotropaic barrier to exclude the forces of disease. The purpose of the one-day object was to renew the settlement boundaries, thereby returning collective life to its primordial, ideal state. Even into the 20th century, rural communities continued to fabricate smaller one-day objects—fibre towels and wooden crosses positioned at the village crossroads—to ward off livestock epidemics (Golubovka 2006, pp. 105–6). At this point it is worth considering the linguistic properties of the word obydenny. In contemporary usage, it is mainly applied in reference to something that is ordinary, typical, or everyday. Ritual terms, such as Obydenny, however, often retain an older meaning in parallel to their current usage. Linguistic analysis shows that the original meaning of obydenny in East Slavic languages is “on the same day,” that is, signifying the convergence of two events—the beginning and end of a process—that are usually separated by a longer period of time (Strakhov 1985). This original meaning signifies the contraction of time inherent in the disaster ritual.

Being made from natural materials, one-day votive objects could exert magical powers over natural forces, procuring divine intercession on behalf of the collective. Ritual objects created in this manner were believed to be one with the natural world and its cosmic energies; though their material existence was ephemeral, their afterlife was eternal as they returned to their origins in nature and became part of the cycle of the seasons (Beliaev 2004, pp. 46–47). As they decayed, one-day churches and one-day crosses built from logs returned to the forests from which they came. The concept of ritualistically created, diminutively sized churches as ephemeral icons was further apparent in the traditional practice of carving ice sculptures in the shape of churches on riverbanks for the Feast of Epiphany, an essential calendar-based ritual for regulating the passage of the seasons (Beliaev 2004, p. 47; Flier 2015).

Thus, with reference to the original linguistic meaning of obydenny, the one-day church can be described as a typical object, created in an exceptional manner under atypical circumstances, to function during the process of its fabrication as an image-mediator between the natural and supernatural realms. The spiritual intention of constructing a one-day church was to bring about an abatement of the Black Death by resetting the seasonal calendar and restoring the primordial equilibrium of communal life, thereby renewing earthly time and synchronising its course with universal time. The cycle of apocalypse and renewal stimulated by the one-day church ritual symbolically reproduced the cycle of the crucifixion, burial, and resurrection of Jesus Christ, which functioned to redeem the world and which opened a new age in the history of humanity (Terebikhin 2016, pp. 23–24). It was the progression of the religious ritual, not the materiality of the physical structure, that endowed one-day churches with their magical character.

5. Practical and Social Significance of One-Day Churches

On a practical level, the function of disaster rituals was to ensure the survival of the community. Medieval Russian rituals had important functions for psychological conditioning, information transmission, and reinforcement of the social order. By channelling individual fears into a socioculturally appropriate performative framework, rituals attenuated anxiety and reinforced collective solidarity in the face of extreme circumstances (Liénard and Boyer 2006). Collective rituals were, moreover, useful for communicating vital information to illiterate people, a medieval Russian form of news transmission (Waugh 2017, pp. 222–30); the fantastical nature of the one-day church ritual would encourage its word-of-mouth diffusion, thus ensuring that even those not physically present at the ceremony would become aware of its performance.

The Black Death placed considerable stress on the social fabric, necessitating the mobilisation of efforts to preserve the social order. Anxiety about the Black Death was compounded by the belief that the earth was living through its final years before the second coming of Christ, the final battle between good and evil, and the Last Judgement. These events were expected to begin in the year 1492, called Year 7000 in Eastern Christian literature and representing seven millennia from the creation of the world (Gippius 2013; Antonov 2022, pp. 57–58). The popularity of the one-day church ritual should be viewed in this context.

With the participation of the archbishop and the prince in the groundbreaking and consecration, and the mobilisation of artisan associations for the construction process, the ritual reinforced religious and political hierarchies through performative actions in urban space (Musin 2009, p. 115). The ritual can, accordingly, be considered as a governance instrument, demonstrating the ability of authority figures to orchestrate an intervention against the forces of nature, thereby accounting for the legitimacy of power (Paūn 2009, pp. 78–81). Conversely, the ritual was an opportunity for common people—merchants, artisans, and peasants—to rally behind the most important offices of church and state, the archbishop and the prince.

Impulses of social conservatism and eschatological anxiety were evident in the religious personalities to whom the one-day churches were consecrated. Several of them were dedicated to the Saviour (spas), signifying hope for deliverance. Additionally, chronicles record several churches during the 15th century being dedicated to St. Varlaam of Khutyn and St. Anastasia the Martyr (Figure 6). These are local saints, whose cults became popular among Novgorod merchants from the late 14th century, a time when increasing social and religious conflicts made it imperative for patriotic citizens to assert loyalty to the ruling group. The vita of St. Varlaam—a nobleman who was abbott of Khutyn monastery—allowed for his association with the figure of archbishop Ivan of Novgorod (1388–1415), who had also been abbott of Khutyn (Bushkovitch 1975, pp. 22–23). As for the cult of St. Anastasia, it was associated with loyalty to Orthodoxy and rejection of heresies (Bushkovitch 1975, pp. 23–24).

Figure 6.

Icon of St. Varlaam of Khutyn, St. John the Merciful, St. Paraskeva, and St. Anastasia with the Virgin of the Sign. Novgorod, 15th century. Russian Museum.

Participation in the ritual, then, was a way for common people to reinforce community bonds and demonstrate patriotism. For the ruling group, participation was an opportunity to reaffirm the legitimacy of their position at the top of the social order.

6. Chronicle Historiographies of the One-Day Church

Upon the completion of the one-day church ritual, it was translated into the written record, attaining permanence through its narration on paper. Chronicles were the primary source of coetaneous documentation of one-day churches, providing a historiography of the ritual. Medieval Russian chronicles were annalistic accounts of notable events in a particular city and its environs that are collected, compiled, transcribed, edited, and copied by an anonymous scribe or chronicler (Lind 1989, pp. 3–6; Waugh 2017, pp. 213–14). Although they evolved into an independent literary genre, Russian chronicles were initially inspired by the Byzantine chronograph, a literary form which manifested a strong preoccupation with apocalyptic eschatology (Lind 1989; Kraft 2012, pp. 213–15; Gippius 2013, pp. 151–58). This tendency is apparent in the chronicles’ lurid descriptions of the Black Death. A single individual was responsible for the chronicle at a given time, but the chronicle as a whole is the collective work of several successive scribes. Any interaction by the chronicler with the text may be termed an “editorial act”; these interventions could be routine, appending the annual entry to the end of the existing manuscript, or more complex, retrospectively editing textual passages from prior years (Timberlake 2001, pp. 196–97). This makes it impossible to determine precisely when particular information was inserted into the written record, by whom, and how long after the fact.

Aside from their documentary functions, chronicles often include literary elements of folkloric legend as well as Orthodox hagiography. From the 12th century onward, chroniclers were likely appointed by archbishops, making the chronicle an essentially ecclesiastical chronicle (Timberlake 2001, p. 197). Ostroswki goes so far as to say that the chronicles incorporated “propaganda” (Ostrowski 2002, p. 145) of the Russian Orthodox church. Religious and secular authority were deeply intertwined, and their interests played a role in chroniclers’ decisions about which events to record and how to record them. During the 15th and 16th century, when it is believed that most chronicles were produced in their current form, the Orthodox church was cooperating with the Moscow tsars to articulate a framework of spiritual legitimacy for Moscow’s nation-building project, which was then in its early phases (Bogatyrev 2007; Filyushkin 2018; Billington 1962, pp. 31–32). Traces of this are apparent in both the Novgorod and Pskov chronicles. The absorption of Pskov into Moscow’s territory is narrated in the chronicle as a triumphant event, with the bishop greeting the new tsar with the words “God bless you, our sovereign, for having taken Pskov without a battle” (Savignac 2016, pp. 151–52). The chronicles thus advance a hagiographic view of ecclesiastical leaders, the authorities primarily responsible for their compilation, and additionally depict princes, especially those from Moscow, in a similar light.

Bearing in mind the tendency in Eastern Christian hierotopy to develop texts producing a quasi-mythological image of the creator of a sacred space, the origin story provided by the Novgorod chronicle for the one-day church ritual is an interesting one. The first one-day church in 1390 was built on the orders of archbishop Ivan (who is referred to as vladyka Ioan in the quoted text at the beginning of this piece), and Ivan personally consecrated the church. It should be recalled that this is the same Ivan who was associated with the cult of St. Varlaam of Khutyn. The chronicle tells that the plague abated “by God’s mercy”, but also “by the blessing of the vladyka.” The plague was turned away by the joint intercession of heavenly and earthly powers; the people would, therefore, owe gratitude for their deliverance to both of them (Figure 7).

Figure 7.

Archbishops Moisei (1325–1330, 1352–1359) and Alexei (1359–1388) of Novgorod appear before the Mother of God and Christ child enthroned. The archbishops are depicted with halos, an indication of sainthood. Fresco in the Church of the Assumption in Volotovo, Novgorodian Land. Late 14th century. Photograph by L.A. Matsulevich, 1910 (Matsulevich 1910), Novgorod Society of Antiquity Lovers.

Similar tendencies are apparent in the Pskov chronicle entry for 1407 (Savignac 2016, pp. 76–77), recording the first time that a one-day church was constructed in Pskov:

“At that time there was a terrible plague in Pskov and the people of Pskov said to Prince Daniil Aleksandrovich, “You brought this plague upon us,” so Prince Daniil left Pskov. Pskov then sent ambassadors to Grand Prince Vasily Ivanovich [of Moscow] requesting that Prince Konstantin, his younger brother, be their prince. Prince Konstantin arrived in Pskov on March 15, the Feast of St. Agapius the Martyr, and Pskov received him with honor. Prince Konstantin then took it into his mind—for God had placed good thoughts in his heart—to build a church dedicated to St. Athanasius. The foundations of the church were laid on March 24, the Feast of holy father Artemon; the church was finished and consecrated in a single day and services were held that same day for all assembled. … The plague died out in Pskov.”

The ritual is described here as the initiative of a prince with “good thoughts in his heart,” sent from Moscow to govern the people of Pskov at their own request (Figure 8). The prince, moreover, gave the order to build a one-day church in Pskov for the first time, on the first day of his arrival. Like the one-day church, the prince’s reign was, at this point, new, pure, and unsullied.

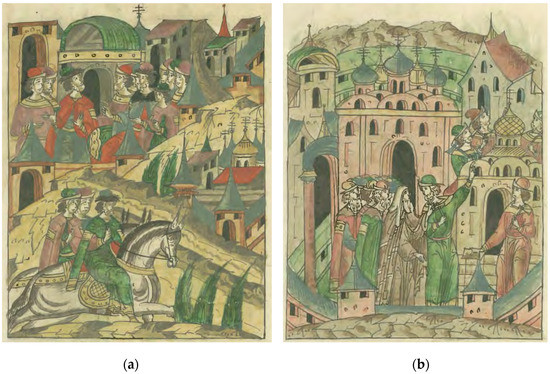

Figure 8.

Powerful figures of the North. (a) Prince Konstantin, 1419; (b) Vladyka Ioan building a stone church, 1411. The Illustrated Chronicle of Ivan the Terrible, Osterman Volume II. Library of the Russian Academy of Sciences.

The virtuous intention of authority figures is, thus, an essential element in the proper completion of religious rituals. In the historiography of one-day churches, they joined the list of glorious deeds and quasi-miraculous actions performed by princes and bishops. Chronicles frequently tell of princes and bishops interacting with icons and their miracle-working powers. In many cases, these leaders are responsible for personally discovering these icons and bringing them into the community, which subsequently benefits from the protection of these objects. The one-day church is, thus, narrated on paper as an ephemeral icon, created by virtuous leadership whose spiritual initiative allows the icon’s miraculous powers to extend to the entire community.

7. Legacies of the One-Day Church

Via chronicle accounts, one-day churches attained permanence in the historical record. They also attained a more directly visible form of permanence in the urban topography. The ritual site remained consecrated ground, even after its completion. Sometimes a larger, more durable church of wood or stone would later be built on the same site where a decaying one-day church had stood (Figure 9). The most notable case occurred in Vologda, where the stone church constructed in the late 17th century atop a one-day church site evolved into the Saviour-Vsegradsky Cathedral, a nationally renowned destination of religious pilgrimage. The cathedral contained an icon, “Saviour, the Most Merciful (Everyday),” said to have been painted in a single day to commemorate the successful completion of the one-day church ritual. Its iconography represents Christ pointing at the forest floor (Vinogradova et al. 2013, pp. 188–93), an allusion to the natural origins of the one-day church.

Figure 9.

Church of St. Varlaam of Khutyn in Pskov, built in 1495 on the site where a one-day church, also dedicated to St. Varlaam of Khutyn, was erected in 1466. Photograph by S.A. Gavrilov, 2011 (Gavrilov 2011), Wikimedia Commons.

From the late 16th century, practice of the one-day church ritual began to decline in the Russian North. The territorial incidence of Black Death shifted southward after 1570, meaning that Novgorod and Pskov were no longer as severely affected (Alexander 1986, p. 246). Other reasons for the ritual’s ebbing relate to the politics of Russian nation-building. Novgorod went through a period of decline after its absorption into Moscow, culminating in bloody reprisals and administrative division overseen by Tsar Ivan the Terrible in 1570 to extinguish its distinct local identity (Birnbaum 2016, p. 54). By the 17th century, chapels had fallen out of favour because of their relative autonomy from ecclesiastical hierarchy as well as their association with the Old Believer’s movement. Church Holy Synod decrees forbade the construction of new chapels, and disallowed the maintenance of existing chapels (Permilovskaya 2010, p. 251). These prohibitions were not lifted until the second half of the 19th century, and even then, church authorities in the North were reluctant to approve peasants’ requests to construct new chapels (Permilovskaya 2010, p. 251).

The medieval one-day church has had an interesting contemporary afterlife. The ritual was revived in Russia, Ukraine, and Belarus during the 2000s. One-day churches have been erected at folk festivals, and at the level of the urban microdistrict (mikrorayon).10 Like their medieval predecessors, the 21st-century one-day churches are often symbolically located at a crossing point within the urban fabric. Funded by private religious groups and advertised via digital media, these rituals are meant to (re)build the sense of community that suffered amidst the transition to market economy.11 The revival of the ritual can be understood in the context of broader sociocultural trends in the post-Soviet space—the return of religiosity to the public sphere, the reconsideration of national history, and the collective search for new markers of cultural identity. Ultimately, it was arguably the translation of the ephemeral one-day churches onto paper and into stone that preserved their memory and allowed for their rediscovery as a practice of contemporary religious expression and cultural identity.

To conclude, the one-day church arose in the specific context of the Russian North during the late 14th century amidst endemic plague and chronic food insecurity, which placed the social fabric under considerable strain. The ritual of creating a votive chapel within a compressed timeframe briefly produced a spatial icon, sacralising the urban territory with the active participation of the collective. The ritual’s immediate goal was to recreate in miniature the crucifixion and resurrection, the cycle of death and rebirth, to reestablish order in the natural world. The process also aimed to produce a renewal of civic patriotism, alleviating tensions in society. Afterward, one-day churches were written into history as the miraculous deeds of their creators.

Funding

This research was funded by the Central European University Foundation of Budapest.

Data Availability Statement

The study did not report any data.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

Notes

| 1 | This article has been developed from conference papers presented by the author at the 5th annual symposium of the New York University Medieval and Renaissance Graduate Interdisciplinary Network (MARGIN), in May 2021, and the First International Online Conference on Pandemics and the Urban Form (PUF), in April 2022. |

| 2 | Chronicle accounts cited in this article are primarily drawn from the Novgorod First Chronicle (Novgorodskaya Pervaya Letopis’) covering the years 1016 to 1471 and the Pskov Third Chronicle (Pskovskaya Tret’ya Letopis’) covering the years 852 to 1650. For the sake of simplicity, these texts are sometimes referred to as “the Novgorod chronicle” and “the Pskov chronicle”, though they are not the only chronicles associated with their respective towns. Quotations are from the 1914 Michell and Forbes translation of the Novgorod First Chronicle and from the 2016 Savignac translation of the Pskov Third Chronicle. Additionally the Rus’ Primary Chronicle or Tale of Bygone Years (Povest’ Vremennykh Let), compiled in Kyiv during the 12th century and covering the period from circa 850 to 1110, is cited. The 1953 Sherbowitz-Wetzor update of the Hazzard Cross translation is used for the Primary Chronicle. Miniatures are reproduced from the Illustrated Chronicle of Ivan the Terrible (Litsevoy letopisny svod), a ten-volume compilation commissioned by Tsar Ivan IV and completed in the late 16th century; miniatures were selected from the seventh volume, “Osterman Volume II,” covering the period from 1378 to 1424 and held in the collection of the Library of the Russian Academy of Sciences. |

| 3 | For a tabular compilation of these events see (Langer 1975, pp. 59–61). |

| 4 | For compilations of these events see (Alexander 1986, p. 246; Langer 1975, pp. 59–61; Huhtamaa 2015, pp. 557–79). |

| 5 | See (Rappoport 1995, p. 178) for the details of church building in medieval Russia. |

| 6 | One-day churches are mentioned in the Pskov Third Chronicle (Savignac 2016, pp. 76–77, 92, 109, 142, 158); and in the Novgorod First Chronicle (Michell and Forbes 1914, pp. 164, 219). See also (Langer 1975, pp. 57–58; Zguta 1981, p. 423) for compilations of chronicle records. |

| 7 | For a typology of traditional wooden religious architecture, see (Opolovnikov and Opolovnikova 1989, pp. 143–66). |

| 8 | The settlement that would evolve into Novgorod was formed in the 9th century. Initially Novgorod was a principality within the Kyivan Rus’, a state that existed in eastern and northern Europe from the 9th to the 13th century, when it disintegrated due to the Mongol invasion. Governed by the Grand Prince of Kyiv, the Rus’ is often considered the first East Slavic state. The prince of Novgorod was politically subordinate to Kyiv until 1136, when the Novgorod Republic was established and self-rule was adopted, giving considerable influence to the local clergy and nobility (boyars), also in the choice of their prince. Originally a part of Novgorod’s territory, Pskov gained independence in 1348. Pskov, however, remained within the jurisdiction of the Novgorod archbishopric until the late 16th century. |

| 9 | The notion of chronotope originated in literary theory, proposed by Russian scholar Mikhail Bakhtin in 1937, and has subsequently been applied to the disciplines of anthropology and ethnology. See (Steinby 2013) for an explication of the original meaning of the chronotope concept and its subsequent broadening applications. |

| 10 | A mikrorayon is a Soviet urban design concept, the smallest unit of central spatial planning. Meant to create a city within a city, it included housing units, commercial space, family services, and public transportation links. Due to the poor quality of construction and the failure to complete many developments according to the original planning concept, mikroraiony are considered obsolete by modern planning standards, which has prompted municipalities to launch various urban renewal and beautification initiatives to include the one-day church ritual. |

| 11 | For examples of online announcements publicising 21st-century one-day church rituals, see (Rossisky Klub Pravoslavnikh Metsenatov 2011; Sinodal’ny Informatsiony Otdel 2014). |

References

- Alexander, John T. 1986. Reconsiderations on Plague in Early Modern Russia, 1500–1800. Jahrbücher Für Geschichte Osteuropas 34: 244–54. [Google Scholar]

- Anonymous. 17th Century. Pervonachal’ny Vid’ Obydennoy Tserkvi [Original View of the One-Day Church]. Print. Spaso-Vsegradsky Sobor. Available online: http://svn-35.narod.ru/foto.htm (accessed on 26 February 2023).

- Antonov, Dmitriy I. 2022. Votivnye Dary na Rusi: Predmety i Praktiky [Votive Gifts in Russia: Objects and Practices]. RSUH/RGGU Bulletin. “Literary Theory. Linguistics. Cultural Studies” Series 4: 50–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arakcheev, Vladimir A. 2014. The Evolution of State Institutions of the Republic of Pskov and the Problem of Its Sovereignty from the Thirteenth to Fifteenth Centuries. Russian History 41: 423–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baïbourine, Albert, and Martine Roty. 2000. Le rituel et l’événement. La construction du temps dans la culture traditionnelle russe. Ethnologie Française 30: 41–49. [Google Scholar]

- Beliaev, Leonid. 2004. The Hierotopy of the Orthodox Festival: On National Traditions in the Making of Sacred Spaces. In Hierotopy: Studies in the Making of Sacred Spaces. Edited by Alexei M. Lidov. Moscow: Radunitsa, pp. 46–47. [Google Scholar]

- Billington, James H. 1962. Images of Muscovy. Slavic Review 21: 24–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Birnbaum, Henrik. 1988. When and How Was Novgorod Converted to Christianity? In Proceedings of the International Congress Commemorating the Millennium of Christianity in Rus’-Ukraine (1988/1989). Cambridge: Harvard Ukrainian Research Institute, pp. 505–30. [Google Scholar]

- Birnbaum, Henrik. 1992. Medieval Novgorod: Political, Social, and Cultural Life in an Old Russian Urban Community. In California Slavic Studies. Oxford: University of California Press, vol. 14, pp. 253–315. [Google Scholar]

- Birnbaum, Henrik. 2016. Lord Novgorod the Great: Essays in the History and Culture of a Medieval City-State, 2nd ed. 2 vols. Bloomington: Slavica Publishers, vol. 1. [Google Scholar]

- Bogatyrev, Sergei. 2007. Ivan the Terrible Discovers the West: The Cultural Transformation of Autocracy during the Early Northern Wars. Russian History 34: 161–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brisbane, Mark. 2013. Baltic Beads and Beaver: Motivations for Medieval Settlement Expansion in Northwestern Russia. In Exploring Atlantic Transitions: Archaeologies of Transience and Permanence in New Found Lands. Edited by Peter Pope and Shannon Lewis-Simpson. Woodbridge: Boydell Press, pp. 15–24. [Google Scholar]

- Brumfield, William Craft. 1988. Church of the Resurrection of Lazarus, from Murom Monastery Karelia, Late 14th Century? Northeast View, Kizhi Island, Russia. Photograph. Library of Congress. Available online: www.loc.gov/item/2018682070/ (accessed on 26 February 2023).

- Bushkovitch, Paul. 1975. Urban Ideology in Medieval Novgorod: An Iconographic Approach. Cahiers Du Monde Russe et Soviétique 16: 19–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chausidis, Nikos. 1994. The Magic and Aesthetic Functions of Mythical Images in the South Slav Traditional Culture. In The Magical and Aesthetic in the Folklore of Balkan Slavs. Belgrade: Library Vuk Karadzik, pp. 5–21. [Google Scholar]

- Filyushkin, Alexander. 2018. ‘To Remember Pskov’: How the Medieval Republic Was Stamped on the National Memory. Jahrbücher Für Geschichte Osteuropas 66: 559–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flier, Michael S. 2015. Muscovite Ritual in the Context of Jerusalem Old and New. Canadian-American Slavic Studies 49: 143–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gavrilov, S. A. 2011. Varlaama Khutynskogo Na Zvanitse [(Church of Saint) Varlaam of Khutyn on Zvanitsa (Street)]. Photograph. WIkimedia Commons. Available online: https://ru.wikipedia.org/wiki/Церкoвь_Варлаама_Хутынскoгo_(Пскoв)#/media/Файл:Варлаама_Хутынскoгo_на_Званице.JPG (accessed on 26 February 2023).

- Gippius, Aleksej. 2013. Gli Ultimi Cinque Centenni (6500–7000): Sulla cronologia dell’escatologia antico-russa. In I testi Cristiani nella storia e nella cultura: Prospettive di ricerca tra Russia e Italia; atti del convegno di Perugia—Roma, 2–6 maggio 2006 e del seminario di San Pietroburgo, 22–24 settembre 2009. Orientalia Christiana Analecta. Roma: Pont. Ist. Orientale, pp. 151–58. [Google Scholar]

- Golubovka, Olga V. 2006. Ethno-Cultural Interaction of the Northern Komi-Zyrians and the Russians in the Realm of Sacral Symbolism. Archaeology, Ethnology and Anthropology of Eurasia 27: 101–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halperin, Charles. 1999. Novgorod and the ‘Novgorodian Land’. Cahiers Du Monde Russe 40: 345–63. [Google Scholar]

- Hazzard Cross, Samuel, and Olgerd P. Sherbowitz-Wetzor, trans. 1953. The Russian Primary Chronicle. Laurentian Text. Cambridge: The Mediaeval Library of America. [Google Scholar]

- Hilton, Alison. 1991. Piety and Pragmatism: Orthodox Saints and Slavic Nature Gods in Russian Folk Art. In Christianity and the Arts in Russia. Edited by William C. Brumfield and Milos M. Velimirovic. New York: Cambridge University Press, pp. 55–72. [Google Scholar]

- Huhtamaa, Heli. 2015. Climatic Anomalies, Food Systems, and Subsistence Crises in Medieval Novgorod and Ladoga. Scandinavian Journal of History 40: 562–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kizenko, Nadieszda. 2008. ‘Popular’ Religion in Russia and Ukraine (Review Essay). Kritika: Explorations in Russian and Eurasian History 9: 1–14. [Google Scholar]

- Kraft, András. 2012. The Last Roman Emperor Topos in the Byzantine Apocalyptic Tradition. Byzantion 82: 213–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Langer, Lawrence N. 1975. The Black Death in Russia: Its Effects upon Urban Labor. Russian History 2: 53–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levin, Eve. 1993. Dvoeverie and Popular Religion. In Seeking God: The Recovery of Religious Identity in Orthodox Russia, Ukraine, and Georgia. Edited by Stephen K. Batalden. DeKalb: Northern Illinois University Press, pp. 29–52. [Google Scholar]

- Lidov, Alexei. 2014. Creating the Sacred Space. Hierotopy as a New Field of Cultural History. Spazi e Percorsi Sacri. I Santuari, Le Vie, i Corpi 61: 61–89. [Google Scholar]

- Liénard, Pierre, and Pascal Boyer. 2006. Whence Collective Rituals? A Cultural Selection Model of Ritualized Behavior. American Anthropologist 108: 814–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lind, John. 1989. In the Workshop of a Fifteenth Century Russian Chronicle Editor. The Novgorod Karamzin Chronicle and the Making of the Fourth Novgorod Chronicle. In Fourteenth International Symposium Organized by the Centre for the Study of Vernacular Literature in the Middle Ages. Odense: Odense University, pp. 1–19. [Google Scholar]

- Matsulevich, L. A. 1910. Bogomater’ Na Trone c Mladentsem Khristom i Arkhiepiskopy Moisey i Aleksey [The Mother of God Enthroned with the Christ Child and the Archbishops Moisey and Alexei]. Photograph. Novgorodskoe Obshchestvo Lyubiteley Drevnosti. Available online: https://www.icon-art.info/hires.php?lng=ru&type=1&id=4560 (accessed on 1 February 2023).

- Michell, Robert, and Nevill Forbes, trans. 1914. The Chronicle of Novgorod, 1016–1471. London: Camden Third Series, vol. XXV. [Google Scholar]

- Moroz, Andrei. 2004. ‘Holy’ and ‘Terrible’ Places: Models of the Creation of Sacred Space in Folk Culture. In Hierotopy: Studies in the Making of Sacred Spaces. Edited by Alexei M. Lidov. Moscow: Radunitsa, pp. 181–84. [Google Scholar]

- Musin, Alexandr. 2009. The Litania and the Making of Sacred Space in Medieval Novgorod. In Spatial Icons. Textuality and Performativity. Edited by Alexei M. Lidov. Moscow: Indrik, pp. 112–17. [Google Scholar]

- Opolovnikov, Alexander, and Yelena Opolovnikova. 1989. Churches. In The Wooden Architecture of Russia. Edited by David Buxton. London: Thames and Hudson, pp. 143–250. [Google Scholar]

- Ostrowski, Donald. 2002. Anti-Tatar Interpolations in the Rus’ Chronicles. In Muscovy and the Mongols: Cross-Cultural Influences on the Steppe Frontier, 1304–1589. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 144–63. [Google Scholar]

- Paulson, Ivar. 1965. Outline of Permian Folk Religion. Journal of the Folklore Institute 2: 148–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paūn, Radu G. 2009. ‘Living Icons’: Relics, Processions, and the Iconic Hypostasis of Power. In Spatial Icons. Textuality and Performativity. Edited by Alexei M. Lidov. Moscow: Indrik, pp. 78–81. [Google Scholar]

- Permilovskaya, A. B. 2010. Chasovnya v Traditsionnoy Kul’ture Russkogo Sebera [The Chapel in the Traditional Culture of the Russian North]. Yaroslavskiy Pedagogicheskiy Vestnik 4: 248–54. [Google Scholar]

- Permilovskaya, A. B. 2011. Kul’turnye Smysly Narodnoy Arkhitektury Russkogo Sebera [Cultural Senses of the Russian North National Architecture]. Yaroslavskiy Pedagogicheskiy Vestnik 2: 291–97. [Google Scholar]

- Rappoport, Pavel. 1995. The Organization of Construction Work. In Building the Churches of Kievan Russia. Aldershot: Variorum, pp. 161–211. [Google Scholar]

- Revko-Linardato, Pavel. 2015. Sociocultural Byzantine Influence on Thought Formation in Medieval Russia. Peitho. Examina Antiqua 1: 321–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rock, Stella. 2009. Popular Religion in Russia: Double Belief and the Making of an Academic Myth. London and New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Rossisky Klub Pravoslavnikh Metsenatov. 2011. Proekt: Obydennye Khrami [Project: One-Day Churches]. Rossiyskiy Klub Pravoslavnykh Metsenatov. September 21. Available online: https://rkpm.ru/proekty/obydennye-khramy/ (accessed on 27 January 2022).

- Savignac, David, trans. 2016. The Pskov 3rd Chronicle, 2nd ed. Crofton: Beowulf & Sons. [Google Scholar]

- Siikala, Anna-Leena. 2002. What Myths Tell About Past Finno-Ugric Modes of Thinking. In Myth and Mentality: Studies in Folklore and Popular Thought. Edited by Anna-Leena Siikala. Helsinki: SKS Finnish Literature Society, pp. 15–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sinodal’ny Informatsiony Otdel. 2014. V Luzhnikakh Vosvedut Obydenny Khram-Chasovniu [An Ordinary Chapel-Church Will Be Built in Luzhniki]. Pravoslavie.ru. September 6. Available online: https://pravoslavie.ru/73417.html (accessed on 27 January 2022).

- Steinby, Liisa. 2013. Bakhtin’s Concept of the Chronotope: The Viewpoint of an Acting Subject. In Bakhtin and His Others: (Inter)Subjectivity, Chronotope, Dialogism. Edited by Liisa Steinby and Tintti Tintti. London: Anthem Press, pp. 105–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strakhov, Aleksandr B. 1985. Vostochnoslavyanskoe ‘Obydenny’ (Semantika i Proiskhozhdenie Slova i Ponyatnya) [East Slavic ‘Everyday’ (Semantics and Origin of the Word and Concept)]. Russian Linguistics 9: 361–73. [Google Scholar]

- Terebikhin, Nikolay M. 2016. Ritualy Prirodnykh i Sotsial’nykh Katastrof v Traditsionnoy Mental’noy Ekologii i Etnomeditsine Russkogo Sebera [Rituals of Natural and Social Disasters in Traditional Mental Ecology and Ethnomedicine of the Russian North]. Ekologiya Cheloveka 23: 21–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Timberlake, Alan. 2001. Redactions of the Primary Chronicle. Russkiy Yazik v Nauchnom Osveshchenii 1: 196–218. [Google Scholar]

- Tolstaya, Svetlana. 2003. Time as an Instrument of Magic: Compressing and Prolonging of Time in the Slavic Folk Tradition. EthnoAnthropoZoom 3: 105–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vinogradova, E. A., N. N. Fedyshin, and I. N. Fedyshin. 2013. Ikona Iz Vologodskogo Spaso-Vsegradskogo Sobora ‘Spas Vsemilostivy (Obydenny)’ i Ee Spiski v Sobranii Vologodskogo Museya-Zapovednika [The Icon ‘Saviour, The Most Merciful (Everyday)’ from the Vologda-Saviour-Vsegradsky Cathedral and Its Copies from the Collection of Vologda Museum-Reserve]. Vestnik Pskovskogo Gosudarstvennogo Universiteta. Seriya: Sotsial’no-Gumanitarnye Nauki 2: 188–202. [Google Scholar]

- Waugh, Daniel C. 2017. What Was News and How Was It Communicated in Pre-Modern Russia? In Information and Empire: Mechanisms of Communication in Russia, 1600–1850. Edited by Simon Franklin and Katherine Bowers. Cambridge: Open Book Publishers, pp. 213–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zelenin, Dmitry. 1911. ‘Obydennya’ Polotentsa i Obydennye Khrami (Russkie Narodnye Obychai) [“Ordinary” Towels and Ordinary Temples (Russian Folk Customs)]. Zhivaya Starina 1/2: 1–20. [Google Scholar]

- Zguta, Russell. 1981. The One-Day Votive Church: A Religious Response to the Black Death in Early Russia. Slavic Review 40: 423–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).