Abstract

In the 10th century, the arrabales of Córdoba underwent a process of rapid growth, triggered by the growing political authority of the capital of the western caliphate. This involved the urbanisation of erstwhile agricultural areas, with new streets and public buildings such as baths, mosques, and funduqs, as well as whole blocks of houses. Domestic blocks generally took the shape of lines of houses that were similar in plan. Among domestic models, which invariably revolved around a courtyard, the most basic type—rectangular in plan, with a central courtyard and a bay on either side—was also the most numerous. This work examines the characteristics and expansions of these buildings, in order to better understand the process that led to the crystallisation of Andalusi urban fabrics.

1. Introduction

The aim of this work is to analyse a type of house common in Córdoba’s arrabales, extensive urban areas built over a short space of time as a result of demographic growth during the caliphate period. This resulted in the construction of large city blocks formed by modest and functional houses that were similar in shape and plan. These houses are long and rectangular in plan and were built around a central courtyard that took up most of the space, to the sides of which stood two bays. These houses were generally built side by side, forming long rows and sharing parting walls; the space inside was also arranged in very similar ways, with little variations.

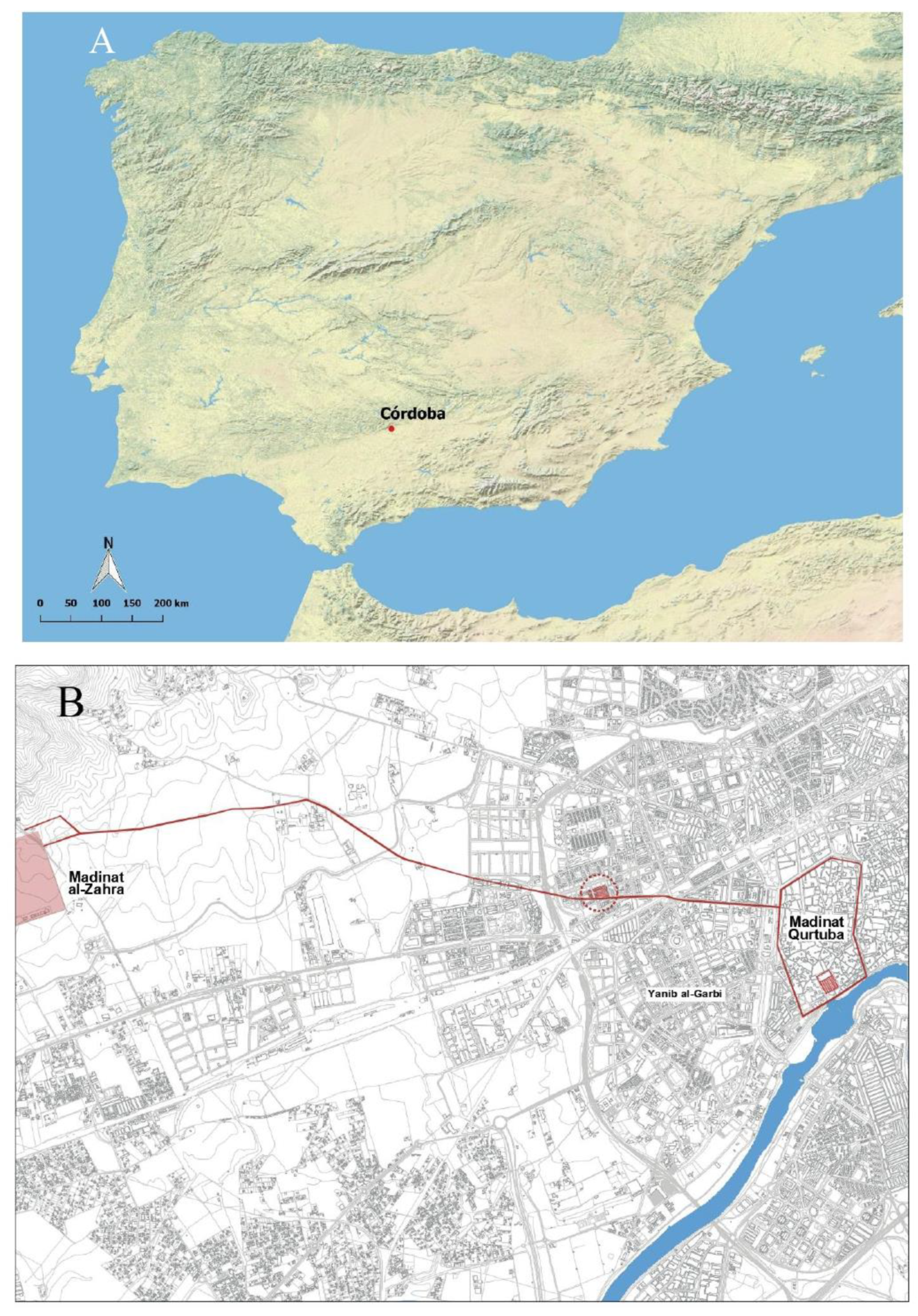

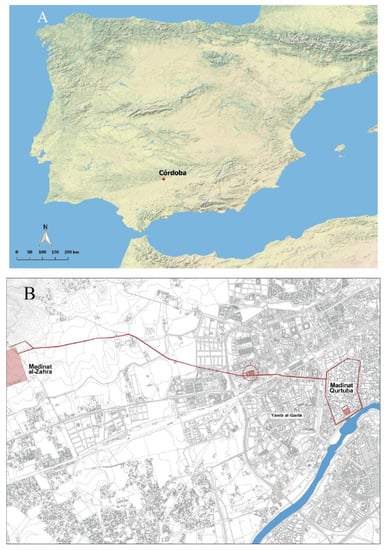

The examples studied here were found during the rescue excavation of the so-called Huerta de Santa Isabel, to the northwest of the city.1 The houses were part of the vast western arrabales of caliphate Córdoba, near the road that left the city through the ʻĀmir al Qurashi gate,2 which ran from Córdoba to Madīnat al-Zahrā̛ (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Location map of Córdoba (A). Location of the excavation area against the plan of modern Córdoba (Source: Instituto de Estadística y Cartografía de la Junta de Andalucía). In red, the road that skirted the arrabal to the south, which ran from the ʻĀmir al Qurashi gate to Madīnat al-Zahrā̛ (B).

Beginning in the late 9th century and, especially, during the reign of ʽAbd al-Raḥmān III and al-Ḥakam II (Manzano Moreno 2019, pp. 15–16), in the 10th century, the city of Córdoba grew spectacularly, as attested by both the archaeological and written records (Cabrera Muñoz 1999, pp. 111–13; Acién Almansa and Vallejo Triano 1998, p. 107). The capital of the Umayyad caliphate became the largest and most important city in western Europe, rivalling oriental metropolises such as Constantinople, Damascus, and Bagdad (Torres Balbás 1987, p. 68). This development had a profound effect on the urban structure, which became gradually denser and more saturated. Soon, this growth spilled over the city wall,3 resulting in a vast urban belt formed by independent arrabales that were closely monitored by the government and the local authorities of the madīna.4

During its peak, Córdoba had 21 peripheral arrabales, which, according to al-Maqqarī, were not surrounded by walls (Torres Balbás 1987, p. 78). The sources and archaeology have revealed that most of them grew around pre-existing almunias, estates owned by emirs, caliphs, and aristocratic families and used for both agriculture and leisure (Acién Almansa and Vallejo Triano 1998, p. 114; Arnold 2008, p. 187; López Cuevas 2013, p. 249; Manzano Moreno 2019, pp. 312–13).5 Probably, some of the new arrabales were built over the agricultural land of these estates, as well as over areas used for other purposes, such as necropolises, some of which were in suburban areas, especially near the city gates.6

This prosperity came to an end with the civil war or fitna (1009–1031), during which the urban population decreased dramatically, and the city contracted sharply. The years of anarchy that followed the fall of the caliphate shook the city, which was attacked and suffered severe damages in 1013, except for the eastern sectors, which were spared (Cabrera Muñoz 1994, p. 128).

The foundation of Madīnat al-Zahrā̛ played a key role in the development of the western arrabales (Cabrera Muñoz 1999, p. 115), as the area between the new palatine city and Qurṭuba entered a period of frantic urbanisation (Acién Almansa and Vallejo Triano 1998, pp. 124, 128). Since the 1990s, excavations have been exposing the vast arrabales of Umayyad Córdoba7, which are characterised by their regular street layout, which is very different to that of the medina, the result of a secular process of development. The large area excavated reveal straight streets and regular blocks, but also cul-de-sacs and sharp-turning alleys, which are not part of the original plan, but the early signs of saturation.

The aims of the present study go beyond the analysis of the Cordoban case, since we intend to study a particular house model that is not exclusive to these suburbs but is documented in other parts of al-Andalus and during different periods.8 Our intention is also to demonstrate the relationship of this domestic type with Andalusi urban development, specifically with the accelerated expansion of the suburban fabric in areas previously occupied by scattered almunias and cultivated fields.9 This is done with the aim of gathering valuable historical information, based on the analysis of these urban areas, about the influence of the State and the role played by private entrepreneurs in the formation of Andalusi cities (that is, about the balance between public and private in a medieval Islamic society). This process was so intense in the suburbs of the Cordoban capital during the heyday of the Caliphate State that it provides us with exceptional archaeological evidence. This, however, does not mean that the phenomenon was exclusive to Córdoba. In fact, to a greater or a lesser extent, it can be found in most Andalusi cities at some point in their history.

2. The arrabal of Huerta de Santa Isabel

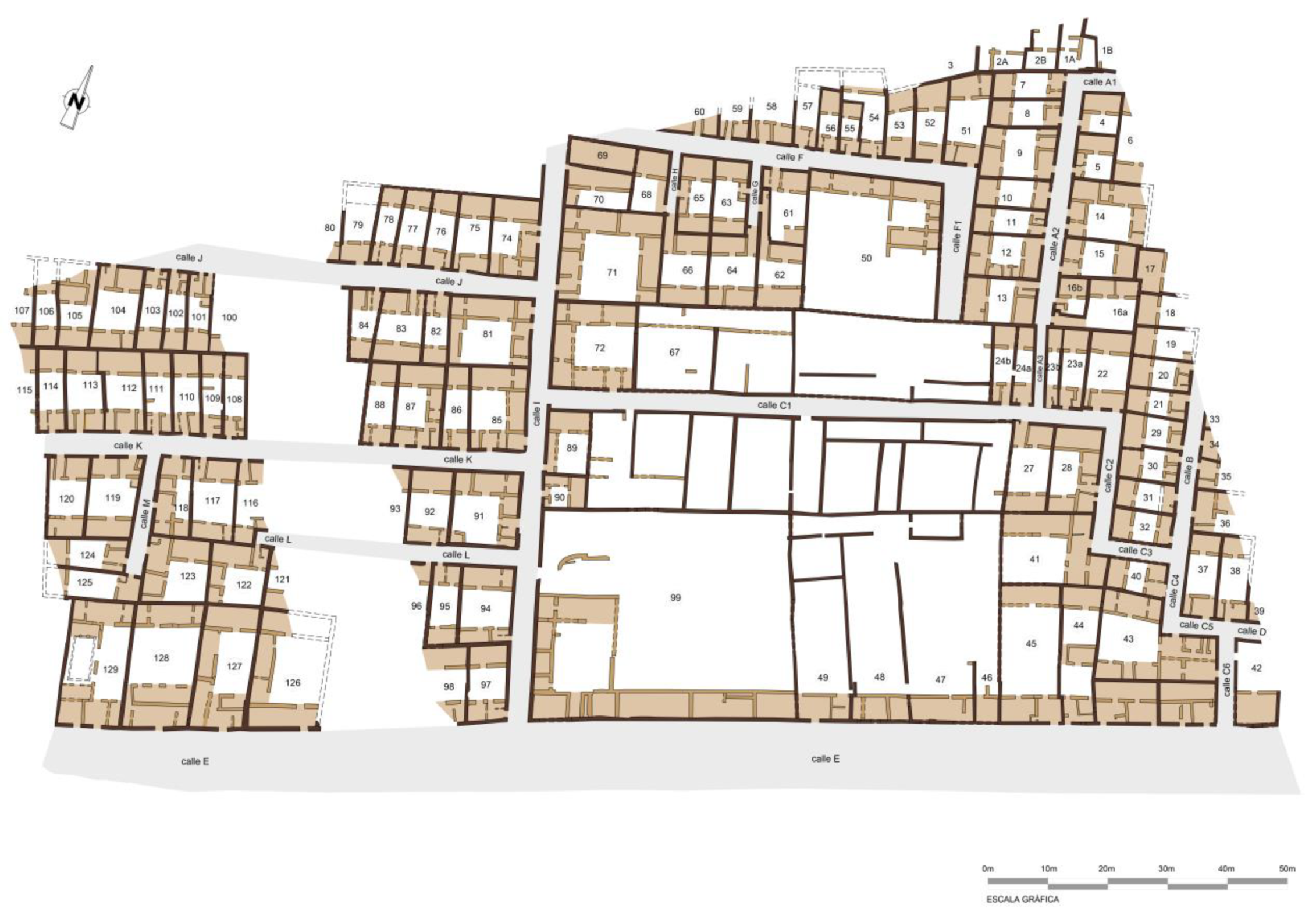

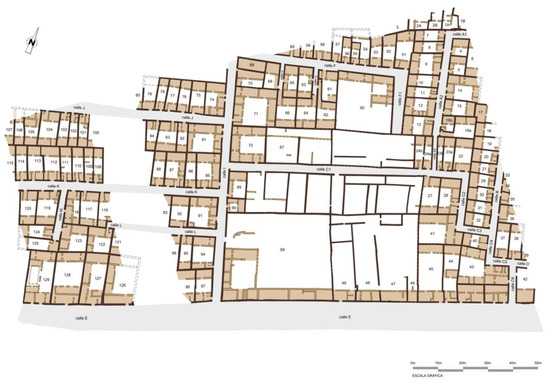

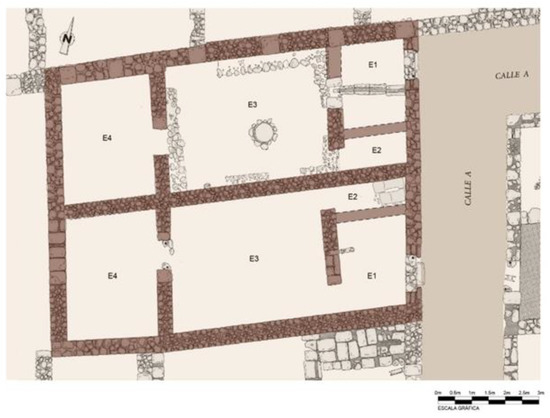

The excavation of Huerta de Santa Isabel revealed 132 buildings (Figure 2):10 of these, 75 were fully exposed; 17 can be reconstructed almost fully; 37 were only partially excavated; and the nature of three is uncertain (they could be shops or workshops). As such, 92 of these structures can confidently be interpreted as houses (the aggregate of the two first groups), 64 of which respond to the domestic model on which we shall be focusing.

Figure 2.

Huerta de Santa Isabel, Córdoba. Plan of the buildings identified in the caliphate-period arrabal.

The houses are arranged around thirteen straight streets oriented N–S and E–W. The main thoroughfares were called E and I, around which the earliest urban blocks were built. Street E, of which 185 m were exposed, marks the southern boundary of the arrabal, reaching the ʻĀmir al Qurashi gate, in the western wall of the city, and connecting the medina with the palatine city of Madīnat al-Zahrā̛ (Figure 1 and Figure 2). It is oriented E-to-W and is 9.50–10.10 m wide. The road is paved by an 8–10 cm thick layer of gravel, laid over a bed of lime, 16–20 cm thick. The northern side of the road is marked by the south façade of the southernmost urban blocks, and the southern side by a hard shoulder that separates the road per se from the open fields11. Street I, oriented N–S, links Street E, to the south, and Street K, to the north; it is 87 m long and between 2.70 m and 3 m wide.

Smaller streets part from E and I to form a regular but, in places, discontinuous and uneven layout. Two areas can be distinguished on either side of the main axis, Street I. To the west, all the streets run from east to west, in parallel with the road to Madīnat al-Zahrā̛,12 except for a cul-de-sac that runs towards the centre of the southernmost urban block. In the eastern sector, streets run both E-to-W and N-to-S; overall, the layout of this eastern sector is less tidy; the width of some streets is uneven, and some take sharp angles (A and F) or move in zig-zag (C), and there are two cul-de-sacs or adarves (G and H).

It seems clear that the layout was based on the road that linked Qurṭuba and Madīnat al-Zahrā̛, Street E, as most of the largest houses in the arrabal face this thoroughfare.13 The second urban axis is Street I, also lined by a row of large houses.14 The remaining houses, except for a few exceptions, are smaller, and the streets to which they open are narrower.

This urban hierarchy is also reflected in the sewage system, constituted by a network of both under- and overground channels and cesspits. The latrines, which were built as near the street as possible, flowed directly into the back wells, which were dug as near the façade as practicable in order to minimise the distance between latrines and wells. The latrines generally opened to the central courtyards, for ventilation and privacy.

Waste water generated by domestic activities and rainfall was channelled from the courtyards to the exterior drain pipes through the entrance hall or other room in the bay closest to the street. Streets I and C channelled the waste from Streets J, K, and L, and A, B, and D, respectively, towards Street E to the south, taking advantage of a natural NW-to-SE slope. Concerning the cul-de-sacs, the waste from G and H ran into F, and that of M into K. The system was designed to evacuate waste towards the open fields and prevent flooding.15

This system, in which the latrines spill into a cesspit and not into a sewer, like the drain channels that evacuate rainwater and domestic waste water is known as “separate evacuation”, and is therefore different to the “joint evacuation” system, which evacuates all waste but needs a greater water flow (Navarro Palazón and Jiménez Castillo 2010, pp. 218–32). The former system is the most common in the western arrabales (Aparicio Sánchez 2008a, pp. 29, 32).

Finally, it is worth stressing that the arrabal was not surrounded by a wall, although the doorjambs found on both ends of Street C confirm that it was shut during the night. No doorjambs to close Street E have been found in Street I, but their existence cannot be ruled out. The absence of a wall facilitated the attack, destruction, and sudden abandonment of the arrabal during the fitna (1009–1031). This event is also attested in the record, as substantial levels of fire have been found in several houses.16

3. Typology of Houses

All domestic units follow the central courtyard model, the most widespread in traditional Islamic societies owing to its suitability to the dry and warm climates that predominate in the areas controlled by Islam. The model is already found during Antiquity in the Near East, Mesopotamia, pharaonic Egypt, and the Graeco-Roman Mediterranean. Under Islam, however, the model was adapted to ensure privacy and limit contact with the exterior. Significant in this regard is the adoption of halls that form an angle and the reduction of openings to the outside (windows, balconies). The typically Islamic zeal for privacy is expressed in the façade of houses, which are plain and do not display the social or economic status of the inhabitants.

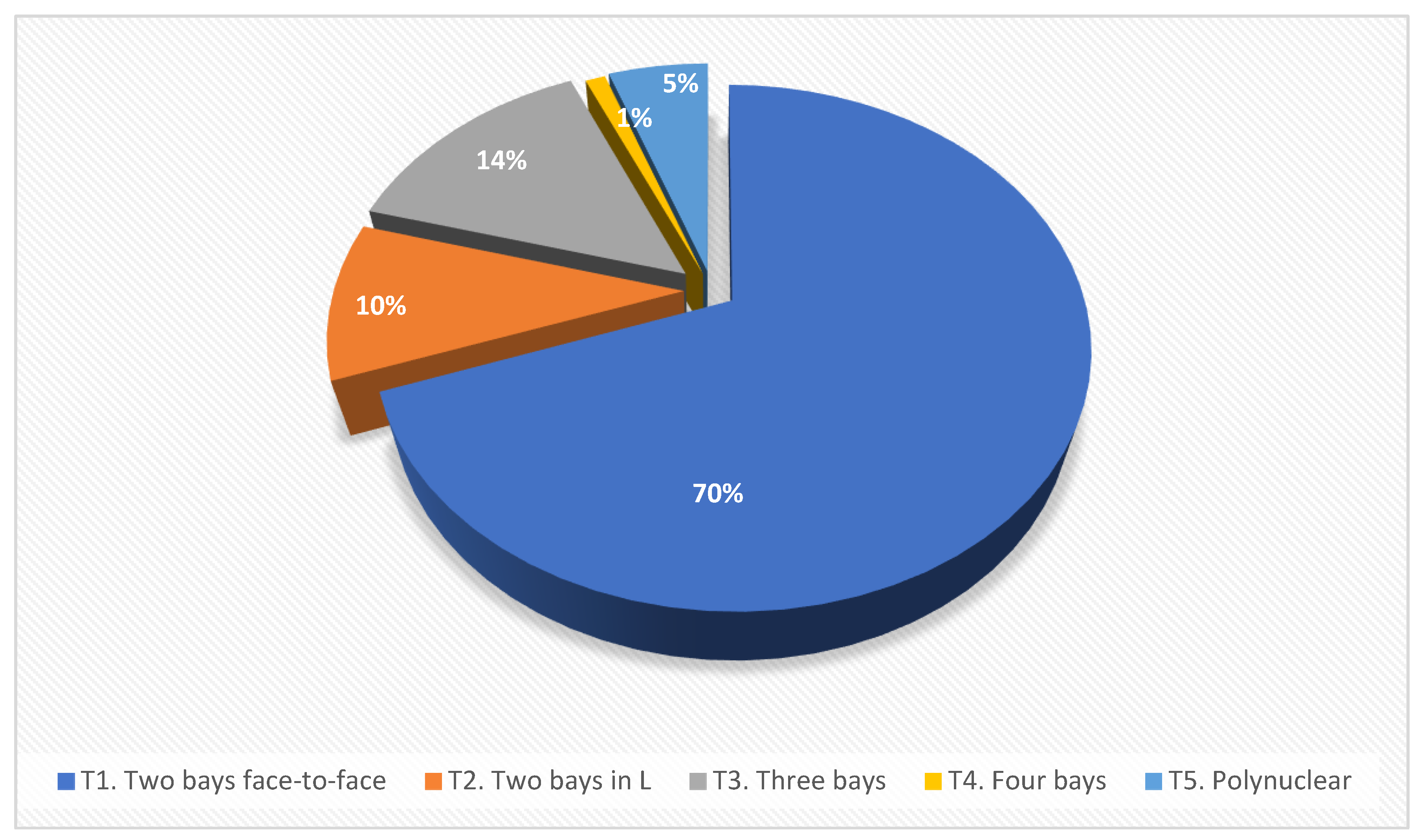

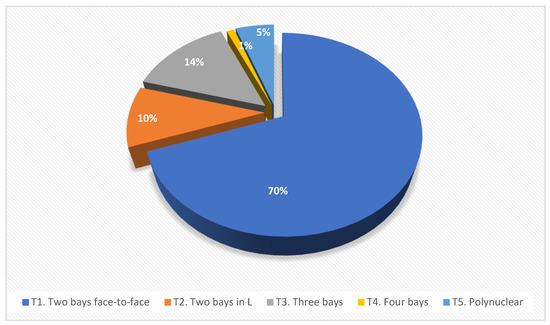

All the houses found in Huerta de Santa Isabel follow this model, although they can be divided into five types based on the internal distribution of space. Our focus shall be in the first of these types.

- Type 1. Two bays face-to-face. The houses form a long rectangle17, with the courtyard in the centre, taking up most of the space, and the two bays to the sides. Five variants have been distinguished, based on the number and function of the spaces found within each bay, which will be described in detail in the following sections; 64 of the houses in the arrabal (69.56%) respond to this model18. In other arrabales of Córdoba the type accounts for a similar proportion of houses19.

- Type 4. Four bays around a central courtyard. Only one example is known on the site (1.09%).24

- Type 5. Polynuclear. These are larger houses distributed in several nuclei, with a hierarchy of courtyards. Four have been identified (5.43%): one is square in plan, two more rectangular, and one forms an irregular polygon.25

It is therefore clear that Type 1, on which we shall focus hereafter, is the most common by some distance, and that Types 4 and 5 (Chart 1) are very rare.

Chart 1.

Proportion of houses by type in Huerta de Santa Isabel de Córdoba.

4. Type 1: Two Bays Face-To-Face and Variants26

These houses are rectangular in plan27, with two bays across the short sides. The courtyard is in the centre and, in most instances, takes over one-third of the area. The entrance hall and the latrine are situated in the bay that is closest to the street, while the living room and bedroom are in the other. Although they are small properties, access from the street is, except in the smallest houses, for lack of room, through a hall that takes a turn, preventing the inside of the house from being directly visible from the outside.28

This is the basic model, but some of the houses present auxiliary spaces, which allow for up to five subtypes to be distinguished.

In the basic type (entrance hall, latrine, courtyard, and living room alcove, which is found in 30 of the 64 Type 1 houses)29, the houses range from 25.10 m2 (House 55) to 56.96 m2 (House 95). House 125 is exceptionally big for the type (63.17 m2) (Table 1).

Table 1.

Type 1, archetype.

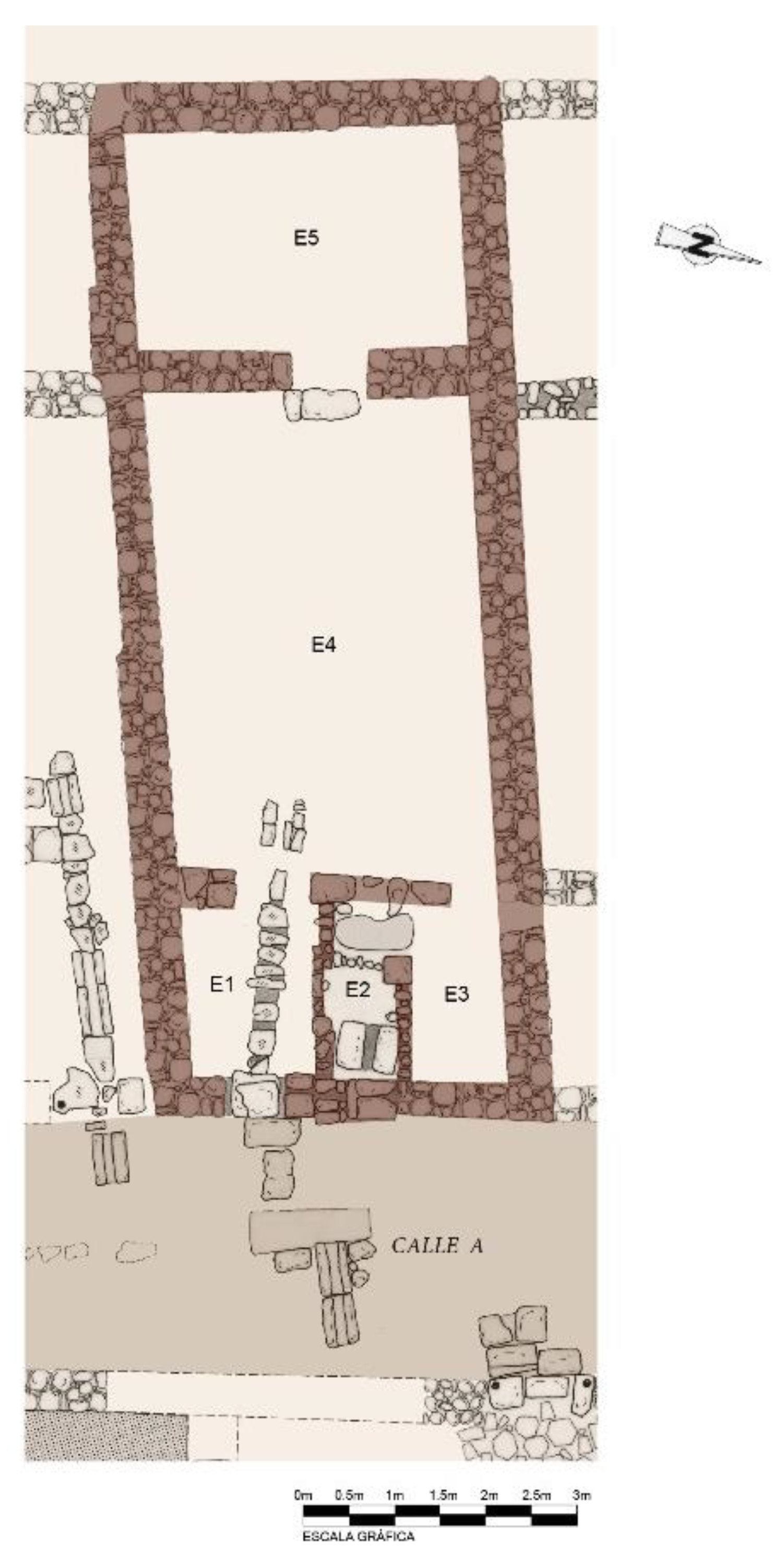

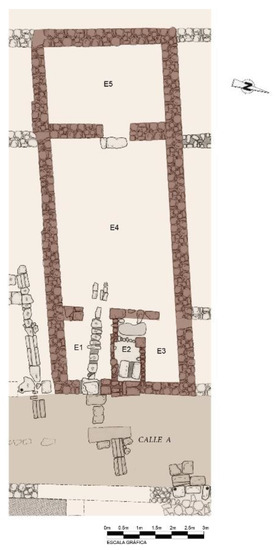

Sometimes, the houses have a small room next to the latrine, perhaps for private hygiene30, for instance in Houses 11 and 20. For example, Room 3 in House 11 (Figure 3) is 2.12 m2 in size, and opens to the courtyard and the latrine, forming a corner to shut the view of the latter (Figure 4).31

Figure 3.

House 11. Plan and room distribution.

Figure 4.

House 11. Latrine with access from a room for personal hygiene (E3).

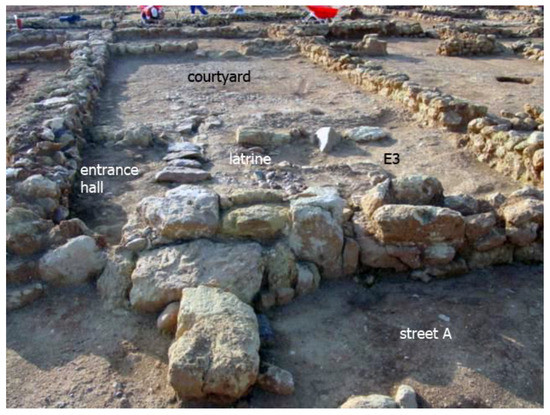

In other houses (102, 103, 108 and 109),32 small rooms, open to the courtyard, in the first bay, have been found to contain charcoal (Figure 5 and Figure 6),33 and are interpreted as hearths, but not full kitchens, because they lack features to store and prepare food, such as benches and pantries.34

Figure 5.

House 103. Plan and room distribution.

Figure 6.

House 103. Room E3 with remains of charcoal.

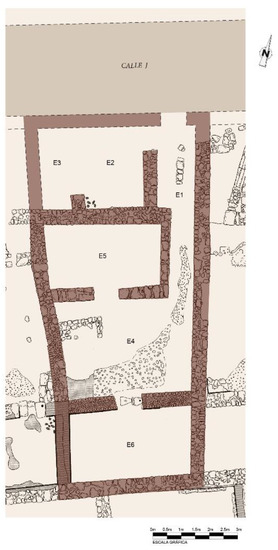

4.1. Variant 1

As noted, Type 1 can present some variations in terms of the number and distribution of rooms. Variant 1 presents an extra room in the ‘outer’ bay, in addition to the entrance hall and the latrine, the function and size of which varies. Therefore, these houses have five spaces, including the courtyard, one more than the basic type. Twelve houses respond to these characteristics35, with sizes ranging from 43.23 m2 in House 101 to 69.69 m2 in House 113 (Table 2). The houses are rectangular in plan, except for Houses 84 and 124, which are trapezoidal in plan, and Houses 53 and 113, which are shaped like an irregular polygon.36

Table 2.

Variant 1.

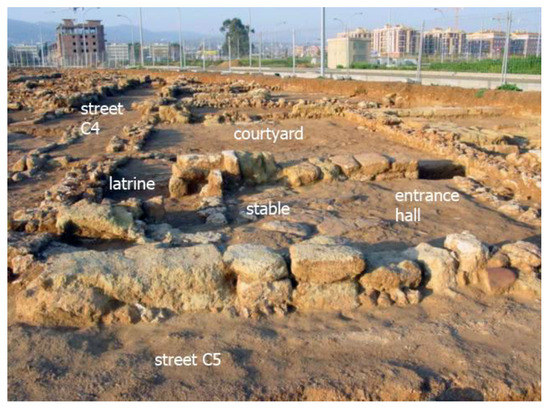

Houses 37 and 38, and, less certainly 75 and 101, may have used this additional space as a stable. In 37 and 38, the stable was accessed from the entrance hall, from which they were separated by a parting wall, as clearly attested in House 38 (Figure 7). In both instances, the room is paved with schist and calcarenite slabs, pebbles, and other stones for ease of cleaning (Figure 7 and Figure 8).

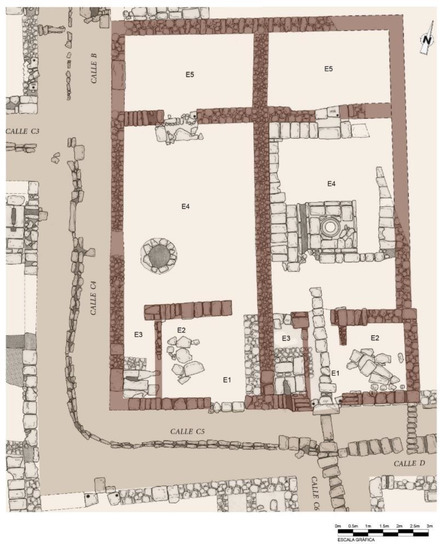

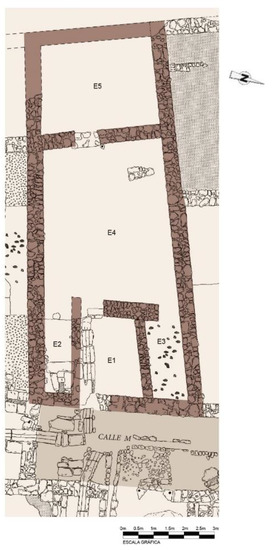

Figure 7.

Variant 1. Houses 37—left and 38. Plan and room distribution.

Figure 8.

House 37. Entrance hall and paved stable.

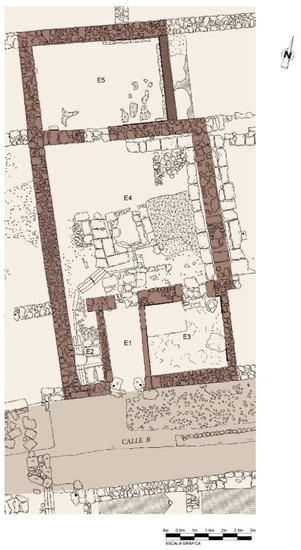

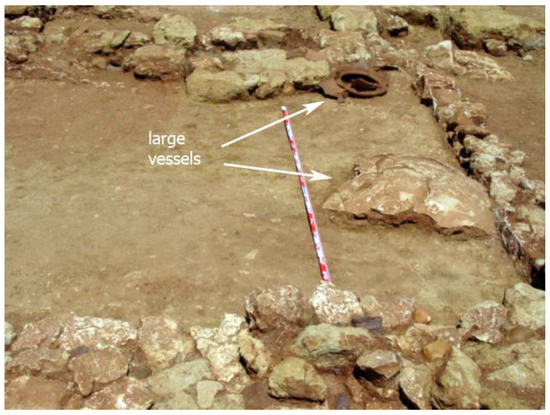

In other instances, this space was used as a storeroom, like in House 113, in which this room is the largest of the bay by some distance (Figure 9). The entrance hall is 2.99 m2 in size and the latrine 2.34 m2, while this additional room is 6.87 m2. It opens to the courtyard; the walls were lined in red-painted stucco, and the floor was made with ground stone; large storage ceramic vases were found inside (Figure 10).

Figure 9.

Variant 1. House 113. Plan and room distribution.

Figure 10.

House 113. Room with remains of large ceramic containers, open to the courtyard.

Finally, in Houses 111 and 124, this space was used as a kitchen. They are small rooms (2.94 m2 and 3.42 m2, respectively), open to the courtyard, and they were characterised by the presence of substantial ash and charcoal deposits, suggesting that they were used for cooking (Figure 11 and Figure 12).37

Figure 11.

Variant 1. House 124. Plan and room distribution.

Figure 12.

House 124. Kitchen open to the courtyard.

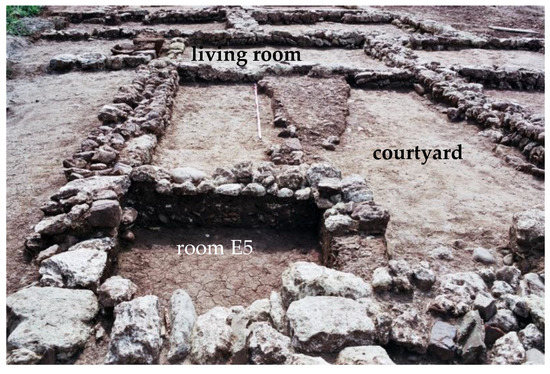

House 101 had a small room (1.12 × 1.18 m) in the northeast corner of the courtyard, in whose interior abundant charcoal deposits were found; like in Houses 102, 103, 108, and 109, rather than a full-blown kitchen, it seems like a room to cook the food prepared elsewhere (Figure 13 and Figure 14).

Figure 13.

Variant 1. House 101. Plan and room distribution.

Figure 14.

House 101. Room E5 in the courtyard.

4.2. Variant 2

It is similar to the previous variant, but with a distinguishable alcove in one of the ends of the living room.38 Twelve houses respond to this model39, all of which are rectangular in plan except for Houses 51 (Figure 15 and Figure 16) and 112, which are irregular in plan, and House 83, which is trapezoid-shaped. Their sizes range from 75.28 m2 in House 120 and 97.66 m2 in House 119; House 45 is exceptionally large (191.90 m2) (Table 3). In some of these, no remains of the parting walls that closed the alcoves have been found, but indirect evidence, including the distribution of the space, suggests that one existed.40

Figure 15.

Variant 2. House 51. Plan and room distribution.

Figure 16.

House 51. In the northern bay, the alcove and the living room can be distinguished.

Table 3.

Variant 2.

Another example of this variant is House 94, which is rectangular in plan. The house has an auxiliary living room in the ‘outer’ bay and a main living room with an alcove in the ‘inner’ bay (Figure 17). The opposite distribution—the main living room is to the south—is found in House 119.41 Two things stand out in this house. First, in contrast to the other houses of Variant 2, the latrine is not in the ‘outer’ bay, but in the courtyard (Figure 18, Space E4); and second, a closed feature in the entrance hall, which could be a manger or the base of a staircase to a potential second storey over the northern bay (Figure 18 and Figure 19).

Figure 17.

Variant 2. House 94. Plan and room distribution.

Figure 18.

Variant 2. House 119. Plan and room distribution.

Figure 19.

Variant 3. House 9. Plan and room distribution (Aparicio Sánchez 2020, Figure 20).

4.3. Variant 3

The main difference between this variant and the previous ones is that the ‘inner’ bay, in addition to the living room with alcove, has another independent room open to the courtyard. In the ‘outer’ bay, we find the entrance hall, the latrine, and one or two additional rooms, so the total of spaces can be six or seven, including the courtyard. These houses are rectangular in plan, except for House 9, which is trapezoid-shaped. Six houses respond to this model42, and all of them are over 80 m2 in size, except for House 15 (63.86 m2) (Table 4). One of the bays in House 9, for example, has an entrance hall, a stable, a latrine, and a possible washroom, and in the opposite a living room alcove and another space that may have been used as a kitchen (Figure 19).43

Table 4.

Variant 3.

4.4. Variant 4

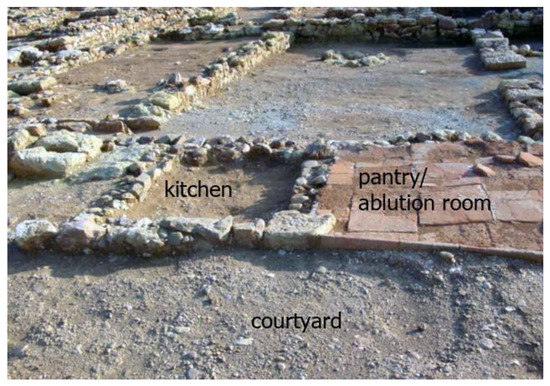

This variant includes a porticoed space in one of the sides of the courtyard; this is not a third full-blown bay, as in Type 3, because it is too narrow. Only House 12 responds to this model (74.36 m2). It is rectangular in plan and is divided into eight spaces (Table 5). The annex is on the southern side of the courtyard, and it is less than 2 m wide, while the bays are over 3 m wide (Figure 20). This area is divided into three spaces open to the courtyard, the latrine and two other rooms which have been identified as a possible pantry or a washroom and a small room used to cook, judging by the substantial deposits of charcoal found within it (Aparicio Sánchez 2017, p. 193, Figure 12). The former is 2.60 m2 and is paved with clay tiles, while the latter is much smaller, 1.45 m2, so its function must have been restricted to cooking (Figure 21).

Table 5.

Variant 4.

Figure 20.

Variant 4. House 12. Plan and room distribution.

Figure 21.

House 12. Spaces of annex: latrine, hearth, and possible pantry or washroom (Aparicio Sánchez 2017, Figure 12).

4.5. Variant 5

It includes the houses with the two opposing bays and a third one attached to one of them. Two houses respond to this model, 105, which is irregular in plan and 71.44 m2 in size; and 128, which is rectangular in plan and 196.63 m2 in size; the size difference is mirrored by the number of rooms in each, six in the former and nine in the latter (Table 6).

Table 6.

Variant 5.

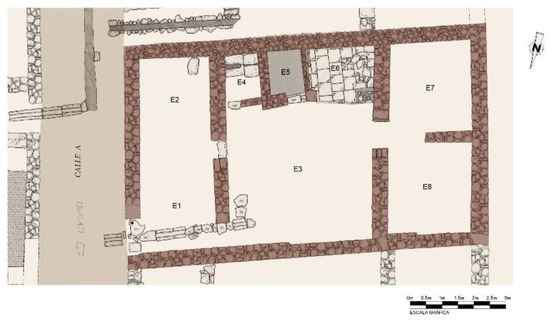

In House 105, the third bay is attached to the ‘outer’ bay (Figure 22), which houses the entrance hall, the latrine, and another room whose function is uncertain, but which could be a stable. The entrance hall gives access to the second bay, which consists of a corridor that extends the entrance hall and a room that opens to the courtyard, which, based on orientation and size, could have been a living room. The ‘inner’ bay has a possible second living room or multiuse room.44

Figure 22.

House 105, Variant 5. Plan and room distribution.

On a larger scale, House 128 reproduced this arrangement, with some differences. First, it has two latrines (Aparicio Sánchez 2008b, p. 244)45, both in the ‘outer’ bay. The large living room in the northern bay has alcoves on both ends (Figure 23). The third bay is attached to the southern bay and could contain a summer living room. The corridor that links the entrance hall and the courtyard is narrow in proportion to the rest of the house, but shuts the view of the inside of the house from the street.

Figure 23.

Variant 5. House 128. Plan and room distribution.

5. Rows of Houses and Partitions

As noted, the houses of Type 1 generally appear forming rows, sharing parting walls, and reproducing the same arrangement, with minor variations.

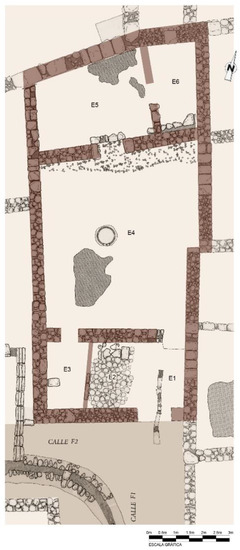

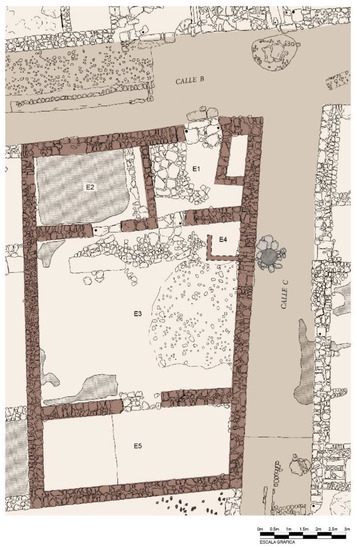

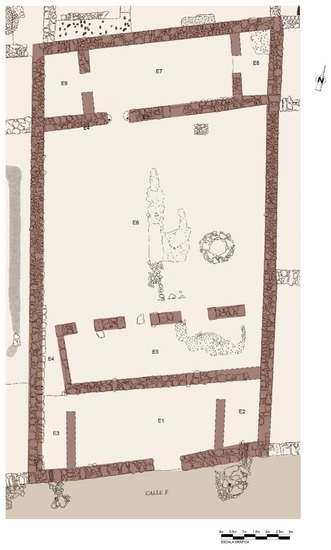

At least seven of these rows were identified in the arrabal (Figure 2).46 The first includes houses from 9 to 13, facing Street A2. Of these, two are smaller (10 and 11) and the other three are slightly larger (9, 12, and 13). To the north of this row, there are two houses (7 and 8) which must have been built at the same time, as suggested by the correlation between inner walls and their symmetry (Figure 24).47 The size of these urban units ranges from 45.55 m2 in House 11 to 88.44 m2 in House 9.

Figure 24.

House 7—top—and House 8. Plan and room distribution (Aparicio Sánchez 2020, Figures 11 and 16).

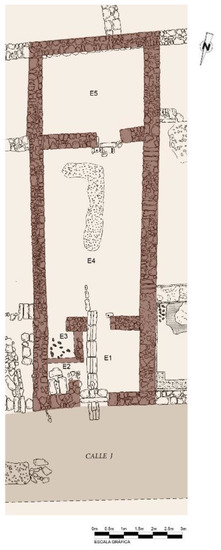

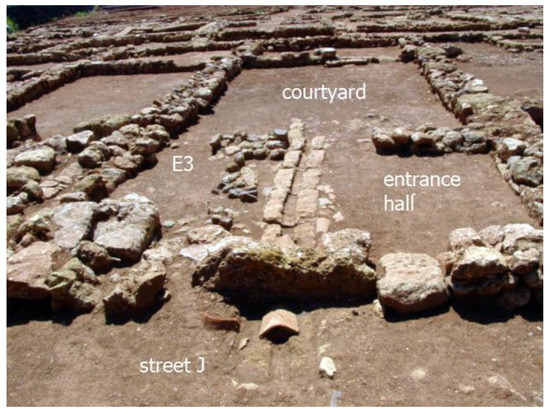

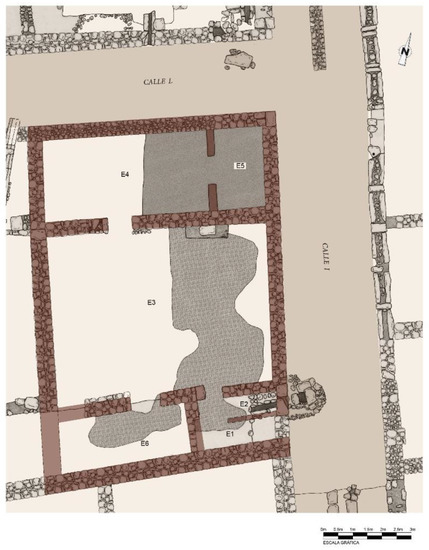

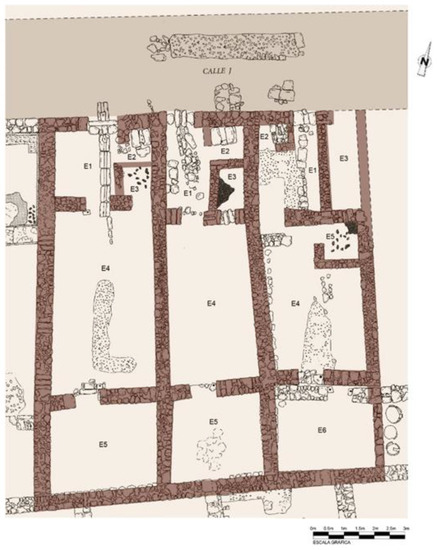

The second row is to the north of Street B and includes eight houses (18, 19, 20, 21, 29, 30, 31, and 32). In this instance, although this must be stated with caution, it is likely that Houses 19–20 and 30–31 originally formed single houses, 87 m2 and 93 m2 in size, respectively. Those for which no evidence of partitioning exists are smaller, between 38 m2 and 48 m2. Row 3, located in Street C1A, encompasses a minimum of five houses (22, 23a, 23b, 24a, and 24b); except for House 22, the others are partitions of earlier larger houses, with an average size of 75 m2. The fourth row (Houses 51 to 59), in Street F, is less regular, because of an earlier adjoining house to the north (Figure 2). Where no evidence of partition exists (51, 52, and 53) the houses range from 84 m2 to 46 m2, while the two examples for which it does (54–55 and 56–55) the size in excess of 73 m2.48 Row 5, in Street J, includes Houses 75 to 79. Some evidence suggests that 74–75 are partitions of an earlier house (Figure 25), and the same may be said about 76 to 78, although with much more caution. Should that be the case, the original houses would be 152 m2 and 143 m2 in size, respectively.

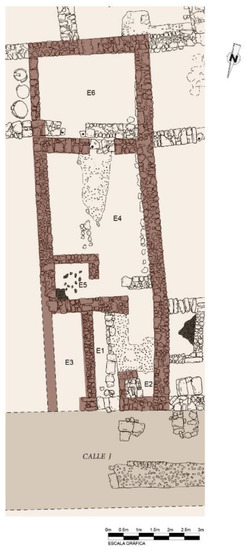

Figure 25.

Rows of houses. From east to west: 76, 77, and 78. Plan and room distribution.

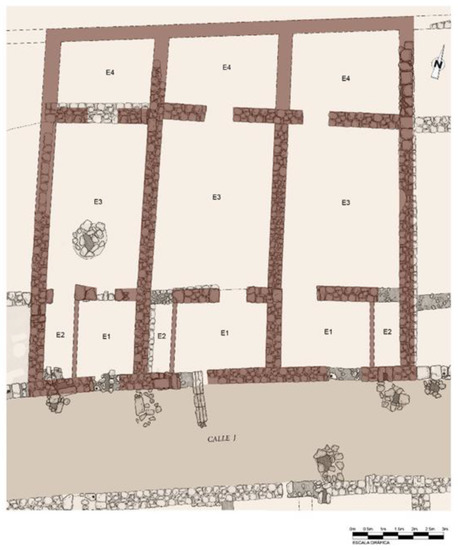

To the west, in Street J, is another row with at least six houses (101 to 106). Houses 105 and 106 could be partitions of an earlier larger house; 101, 102, and 103 (Figure 26) seem to be the result of the allotment of a single plot of land, as suggested by the alignment of their southern bays. If that is the case, the houses, including House 104, would range in size from 88 m2 and 131 m2.

Figure 26.

Houses 103, 102, and 101, from west to east. Plan and room distribution.

The last row, in Street K, includes eight houses (108 to 115). Again, partitions have been attested in Houses 108–109, 110–111, and 112–113, but it is uncertain if this is also the case for the remaining two. In these three instances, the houses are of a good size, ranging from 86 m2 to 148 m2.

The analysis of these rows of houses of Type 1 strongly suggests that the smallest houses were not originally built that way, but were the result of the partition of larger houses49, perhaps as a result of inheritances; in other instances, large plots seem to have been allotted, leading to the construction of several houses, e.g., 19–21 and 29–32; when the plots were smaller, they could accommodate only two or three houses (Figure 24, Figure 25 and Figure 26).

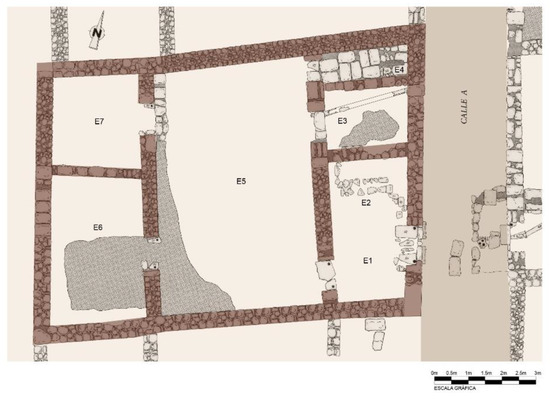

Houses 23a, 23b, 24a, and 24b also seem to be uneven partitions of earlier houses, as 23a is 47.54 m2 in size and 23b only 29.01 m2 (Figure 27).

Figure 27.

Houses 23b—left—and 23a. Plan and room distribution (Aparicio Sánchez 2021, Figure 2B).

Concerning the partition that results in Houses 24a and 24b, it needs to be noted that this partition was conditioned by the shared access to the water well (Aparicio Sánchez 2021, p. 29).50 It is clear that the parting wall runs across it from north to south (Figure 28 and Figure 29).51 On the other hand, the wall, which runs over the well and gives access to members of both households, seriously compromises the privacy of the courtyards, which strongly suggests that the inhabitants of both houses were kin.52

Figure 28.

House 24b and House 24a. Plan and room distribution (Aparicio Sánchez 2021, Figure 2A).

Figure 29.

Water well shared by Houses 24a and 24b, which suggests that they were originally part of a single house (Aparicio Sánchez 2017, Figure 16).

Two further examples of partitions, likely to affect two related households, are Houses 117–118 and 124–125, which shared the cesspit well on which the latrines emptied.53

6. Conclusions

This work has examined a common type of house in Córdoba’s arrabales during the 10th century; it is characterised by a rectangular, long plan, a central courtyard, and two built bays on the shorter side of the rectangle. These houses, which often form rows, share parting walls and reproduce the same interior arrangement54, with some variations; in general, the entrance hall and the latrines are situated in the ‘outer’ bay and the living room and alcove in the opposite bay. This is, in short, the most basic model to which central courtyard houses, typical of traditional Islamic societies, can be reduced.

This type of house is well attested elsewhere in al-Andalus55, but the arrabales of Córdoba are quite exceptional in that the type accounts for such a high proportion of the houses identified; after all, they are small houses with restricted habitability conditions. Their large number and the consistent repetition of the same interior arrangements along long rows of houses need to be put in relation to broader urbanisation processes. Based on the available data, we suggest the following phases:

- In the pre-urban phase, the periphery of the city was surrounded by a belt of privately or state-owned agricultural estates, such as almunias. This pre-urban phase has been attested in other arrabales in Córdoba, and some evidence also exists for this arrabal. The earliest houses were built on two large plots near the road: House 99 and the house that was eventually subdivided into Houses 46 to 49; the rest of the future arrabal was still dedicated to agricultural land. This phase has been attested in Ronda Oeste, where irrigation infrastructure predating the houses has been found, alongside marginal agricultural land and evidence for the process of conversion of these into urban spaces (Camacho Cruz 2018, p. 47). In the area of Tablero Alto, a large water cistern and other features have been related to an almunia, which, based on its location, could be ʽAbd al-Raḥmān I’s al-Ruṣāfa. The cistern, the purpose of which was to ensure the estate’s water supply, was built in the caliphate period and was in use until the late 13th or early 14th century (Clapés Salmoral 2020, pp. 21, 22, and 25).In this phase, the state may have been behind the urbanisation of the area, building streets and roads to access the city. In the arrabal that emerged around the road to Trassierra, for instance, it was concluded that, along with the existence of an almunia and a stream, the construction of the road, which, unlike other roads that had a Roman substratum, was built ex novo to link Qurṭuba and Madīnat al-Zahrā̛, acted as a stimulus for the emergence of the arrabal (Rodero Pérez and Molina Mahedero 2006, pp. 289–90). According to Ibn al-Athīr, ʽAbd al-Raḥmān II “built and laid down roads”, and al-Maqqarī stated that ʽAbd al-Raḥmān III “liked to urbanise land, setting up milestones…” (Castejón 1961–1962, p. 132); Ibn Ḥayyān reports that the road between al-Nāūra and Madīnat al-Zahrā̛ “was cleaned of obstacles after Nasir rode down it in person, taking the matter in his own hands and ordered all possible efforts to be made…”(Ḥayyān 1981, p. 322). However, the archaeological reality that we have studied in this work does not suggest that the State was responsible for intensive urbanisation that included the construction of houses; it did not even do so in Madīnat al-Zahrā̛ , where, according to Ibn Ḥawqal: “‘Abd al-Raḥmān ibn Muḥammad laid out markets there, built baths, caravanserais, citadels, citadels, gardens; he invited the eager people to live there by ordering the following proclamation to be promulgated by al-Andalus: ‘Whoever wishes to build a house or choose a dwelling place close to the sovereign will receive a premium of 400 dirhams’ A river of people hastened to build; the buildings became dense and the popularity of this city acquired proportions, to the extent that the houses formed a continuous line between Córdoba and Zahrā’” (Ḥawqal 1971, p. 65 ff).

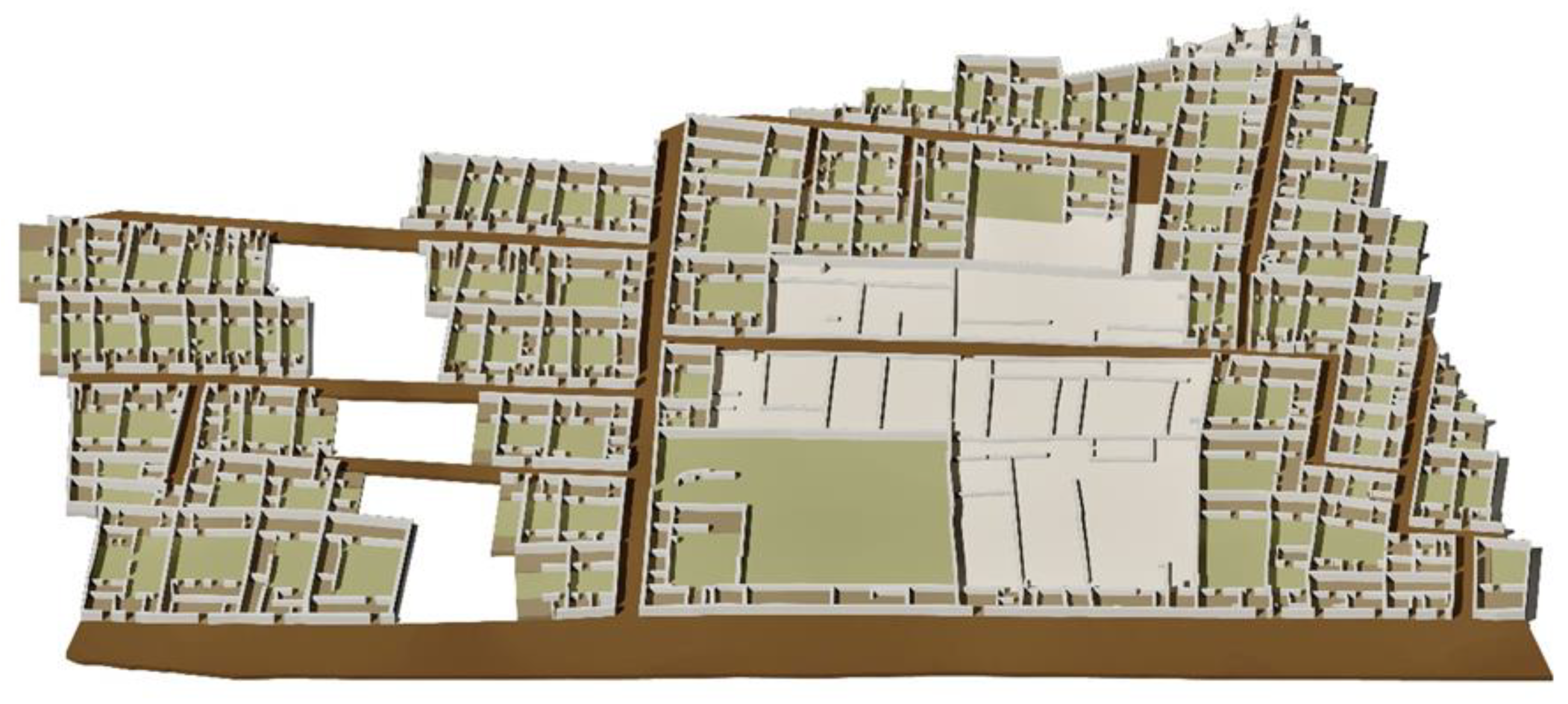

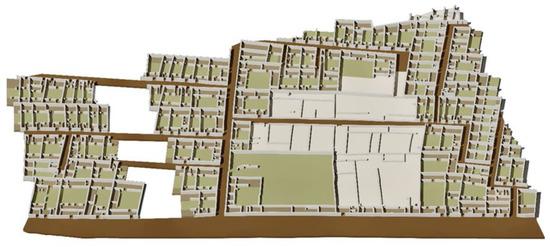

- Urbanisation of the plots closest to the main road. The earliest houses are near the roads and the almunia buildings. The plan clearly shows that the early houses, nearest to the road heading to the medina, Street E, were among the largest (Figure 30). Farther from the road, the layout becomes less neat, streets narrow down and become less straight, and the houses are smaller. This urbanisation model may be characterised as ‘centripetal’; the outer sides of the block formed by pre-existing roads are built over first, and thence, the houses grow towards the interior (Jiménez Castillo 2013, pp. 1.110, 1.111).

Figure 30. Three-dimensional (3D) reconstruction of the houses in arrabal Huerta de Santa Isabel, Córdoba (Ángela Mª. Aparicio Ledesma).

Figure 30. Three-dimensional (3D) reconstruction of the houses in arrabal Huerta de Santa Isabel, Córdoba (Ángela Mª. Aparicio Ledesma). - Rapid urbanisation, by sectors, of the agricultural plots farthest from the main road. This led to the configuration of secondary roads, which match right-of-ways associated with former irrigation channels and agricultural paths. This process would, in any case, be led by well-off social groups, which may or may have not been the owners of the pre-existing agricultural estates (Vázquez Navajas 2022, pp. 173–74, 186–87). Former agricultural plots were thus built over to form urban blocks, which adapted to the existing plot distribution. This phenomenon is also found elsewhere. In fact, it is not rare for the periphery of Andalusi cities to present an “organically regular” layout that has nothing to do with any official attempt at urban planning, but with the distribution of plots in the earlier agricultural landscape, which adopts orthogonal plans and a “limited geometry” in response to agricultural and irrigation needs. As such, the urbanisation of the area simply reproduces the regular arrangement of earlier agricultural plots, for which the traditional Islamic domestic arrangement, organised around a central courtyard, is eminently suitable (Navarro Palazón and Jiménez Castillo 2004, pp. 237, 239).A similar process has been suggested for another one of the western arrabales, P.P. O-7, although in this case no remains of wells or irrigation channels have been attested. The emergence of the arrabal in the 10th century has been associated with a process of “urban development”, which consisted on the “construction of the façade walls and the parallel parting walls, before the allocation of the available space to different households” (Clapés Salmoral 2019, pp. 50–51). Generally, it is held that these developments were undertaken by private investors (Murillo Redondo et al. 2004; Murillo Redondo et al. 2010; León Muñoz 2018), as the written sources do not mention any form of state intervention in the process.The analysis of the city blocks in Huerta de Santa Isabel yields further keys to this process. First, the differences between the eastern and western sector of the excavated area, which are significant, including the orientation of the streets, reveals that the arrabal did not emerge all at once. Second, the internal arrangement of each city block is extremely regular, but differs markedly from block to block, even when they are close together, which strongly suggests that the blocks were urbanised one by one. The arrangement of some of these blocks indicates that the facades and the parallel inner walls were built in a single phase (the walls of up to seven or eight houses are perfectly aligned), and that the parting walls between houses were built later.The written sources, which are always scarcer and sparser than we would like, suggest that enterprising individuals carried out projects that included the construction of housing blocks. This fact could explain the homogeneity in terms of layout and floor plans in some of the clusters of houses documented by archaeology, such as those studied in this article; this homogeneity strongly suggests that all the dwellings were built at the same time and according to a single plan. For instance, a fatwa by Cadi Ibn ‘Iyāḍ refers to the owner of some land, which must not have been very far from the city centre since there was a mosque nearby, on which he built “dozens of houses”, obviously for the purpose of selling/renting them: “I ask you for an answer—God honour you—about a man, whose land was parcelled out, dozens of houses being built on it, the sewers of which ran into a main street, which had to be raised so that the canal would pass under it, in a place close to a mosque which (initially) rose above the street”(Ibn ‘Iyāḍ 1998, pp. 228–29).Because of the rapid pace of this process and the soaring demand for housing and land to build, the most basic type of house became widespread. The type is eminently functional, reducing habitability features to the most elemental expression, making the most of the available land. As noted, this domestic model is attested in other cities in al-Andalus, although it is much less preeminent and is the result of the partition of larger houses, rather than of a process of ex novo urbanisation, as in the case at hand. Therefore, the extension of the model in the periphery of Córdoba must have been triggered by explosive demographic growth in the city during the 10th century. The fact that the other site in which this type of house predominates is the arrabal of El Fortí, Denia, built ex novo in the 11th century during the city’s apogee under its Slavic taifa rulers, when the space available inside the city walls became scarce, can hardly be coincidental.56However, it is worth stressing that, although these small houses were the most common type, they were not the only ones, as bigger houses existed, probably the home of larger households.

- Incipient saturation processes, which are reflected in three phenomena: partition of houses, emergence of cul-de-sacs, and the partial occupation of public or communal areas.Once all the agricultural land was built over, and since Córdoba’s population continued growing, the urban layout became denser, as illustrated by the partition of houses57; the occupation of public and communal space58; and the opening of adarves or cul-de-sacs.59In the previous section, we already mentioned the partition of houses at the site. Concerning the encroachment of public space, Houses 23b and 24a partially invaded Street A, to gain a little bit of room, while House 116 appropriates part of Street L to gain an extra room (Figure 2). In this way, the domestic plots became larger at the expense of public roads.60The formation of adarves can seem to respond to the opposite logic, as a public road is created where domestic rooms previously existed; however, the origin of this process also lies with the saturation of the urban space, because these cul-de-sacs were used to give access to houses that became otherwise locked in inside the urban blocks as a result of the partition of houses (Navarro Palazón and Jiménez Castillo 2003, p. 322). Four adarves have been identified in Huerta de Santa Isabel, G, H, L and M; G led to Houses 62 and 64; H to 65 and 66; M to 123, 124, and 125; and L to 92, 96, and 122, and some other houses that could not be excavated, between Houses 96 and 121.61

It is unclear if the growing scarcity of space led to the construction of second storeys (Navarro Palazón and Jiménez Castillo 1996), although no firm evidence for this has been found to date.62 Some elements found during excavation could perhaps suggest the existence of upper storeys or roof terraces, including the potential foundations for a staircase,63 porticos,64 and descending drainpipes,65 although none of them can be regarded as sufficient evidence in themselves. Many of the houses were intensely robbed out after their abandonment, so the plans will have to be examined in further detail to recognise additional evidence for upper storeys.

In any case, the general appearance of the urban landscape analysed in this study, as in the other interventions that have been carried out in the suburbs of Cordoba, is dense, with hardly any spaces left free of buildings. There is no evidence of intensive planning by the authorities, since the relative regularity of the urban layout is the result of the agricultural areas that predated the urbanisation of the area; nevertheless, the hand of the State can be seen in the layout and width of the main public roads. The archaeological record also reveals an urbanisation process which took into account the fact that building space was at a premium and was therefore used to the limit, as suggested by the size of the dwellings. These were built on former private agricultural plots by private entrepreneurs, which does not mean that some of them may not have belonged to the ruling elite. Finally, the urban landscape also reveals that the ruin and abandonment of these spaces occurred before the processes of large-scale urban saturation that are typical of the more advanced phases in the evolution of the urban fabric.

Author Contributions

This work has been prepared jointly by the two authors. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

Data is contained within the article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Notes

| 1 | The excavation affected plots I (Subplots 29, 30 and 31) and J of Plan Parcial E-1.1 del PGOU de Córdoba, owned by the public company VIMCORSA, and were undertaken between 2001 and 2003. As they responded to planning needs and followed no set research design, the excavation was subject to the usual time pressures. The results are being reviewed within the framework of project “La arquitectura residencial de al-Andalus: análisis tipológico, contexto urbano y sociológico, bases para la intervención patrimonial”, del Plan Nacional I+D+i HAR 2011-29963, directed by Julio Navarro Palazón and launched in 2012. |

| 2 | On the western side of the wall, modern Puerta de Gallegos. |

| 3 | The evolution of medinas can be divided into four stages: creation, expansion, saturation, and spill-over, which, although diachronic, can overlap and do not necessarily affect all the urban areas evenly. The spill-over stage is reached when housing expands outside the city walls, forming arrabales, “the continuation of an earlier process, in which pottery workshops, tanneries, and other space-demanding facilities, have been expelled to the margins”; Córdoba is regarded as a “paradigmatic example” (Navarro Palazón and Jiménez Castillo 2003, pp. 123–24, 373–74). |

| 4 | The term “arrabal” derives from the Arabic rabad, which means independent neighbourhood, inside or outside the city walls. Arrabales outside the city walls nearly always postdated the construction of the city walls, and could be followed, or not, by the construction of a wall around them (Torres Balbás 1987, pp. 73, 74, 77). |

| 5 | Emilio García Gómez (García Gómez 1965, p. 334) defines almunias as “country houses surrounded by a bigger or smaller garden and agricultural land; they were used as temporary residence and were, at the same time, a place for leisure and production”. The unbuilt areas of almunias agricultural land, pasture, and irrigated areas (Navarro Palazón and Trillo San José 2018). |

| 6 | Andalusi graveyards are not exclusively peri-urban elements, as they were also found inside cities, especially in those cities that had not yet undergone intense densification processes (Navarro Palazón and Jiménez Castillo 2003, pp. 346–50). |

| 7 | In addition to the arrabal of Huerta de Santa Isabel, on which we shall focus, with 132 houses around thirteen streets, many more can be mentioned: Ronda Oeste, with 248 domestic units and up to 42 streets (Camacho Cruz 2018, pp. 62, 65); Huerta de San Pedro, with 34 houses around three streets (Córdoba de la Llave 2006, 2008); Unidad de ejecución MA-4B Las Delicias, Carretera Palma del Río 39, with 48 houses around eight streets (Morales Ortiz 2010, pp. 880, 882); Manzana 15, P.P. O-7, with 52 buildings around eight streets (Liébana Mármol 2008); C/Joaquín Sama Naharro, with 43 houses around seven streets (Aparicio Sánchez 2009, p. 1.126; Aparicio Sánchez 2010, p. 185); Manzana 14, Plan Parcial O-7, with 40 houses around three streets (Clapés Salmoral 2013, pp. 98–99); Zona arqueológica de Cercadilla, with over 40 houses and eleven streets (Castro del Río 2005, pp. 36–94, 159; Castro del Río 2010, p. 616); and Sector Nororiental of the caliphate-period arrabal in the site of Cercadilla, with 28 houses around five streets (Fuertes Santos 2007, pp. 49–59). |

| 8 | There is an abundant bibliography on Andalusian domestic architecture, especially case studies; on a general level, see the different studies contained in the monograph on the subject edited by Navarro Palazón and Díez Jorge (2015). On the formative processes of Andalusian urbanism to which we refer here, see Navarro Palazón and Jiménez Castillo (2007b, 2007c). |

| 9 | On the expansion of the urban tissue of the Andalusi cities over the agricultural spaces of the periphery, see Navarro Palazón and Jiménez Castillo (2022). |

| 10 | The results of the excavation have been partially published elsewhere (Aparicio Sánchez 2008a, 2008b, 2017, 2020, 2021; Aparicio Sánchez and Riquelme Cantal 2008). |

| 11 | The hard shoulder is easily distinguished from the road/street, which can be easily identified through the wheel marks left by traffic. The hard shoulder is 1.60 m wide, and is covered in a layer of pottery fragments, general debris, and pebbles, between 5 and 10 cm thick. |

| 12 | Figure 2 shows an empty area that runs through the centre of this urban block, where archaeological excavation was prevented by the presence of a modern road. |

| 13 | Houses 45, 47, 48, 49, 99, 126, 127, 128, and 129 (Figure 2). |

| 14 | 71, 72, 81, 85, 91, and 94 (Figure 2). |

| 15 | For a more detailed description of this system, see Aparicio Sánchez (2008b). |

| 16 | 63, 71 and 90. |

| 17 | Except for House 51, which is shaped like an irregular polygon because the north wall was already there when the house was built, and the house had to adapt to it (Figure 2). |

| 18 | Calculated out of the total of 92 mentioned in Section 2. |

| 19 | Ronda Oeste (Camacho Cruz and Valera Pérez 2019, p. 65); Piscina Municipal de Poniente (Cánovas Ubera et al. 2008, pp. 214–15); al-Ruṣāfa (Murillo Redondo et al. 2010, pp. 589–91); Unidad de ejecución MA-4B Las Delicias (Morales Ortiz 2010, p. 884); Huerta de San Pedro (Córdoba de la Llave 2008, p. 41); C/Joaquín Sama Naharro (Aparicio Sánchez 2010, p. 186), and Cercadilla (Fuertes Santos 2007, p. 60). |

| 20 | Houses 4, 5, 91, 122, and 123 are square in plan; 16b and 89 are rectangular, and 16a and 41 form an irregular polygon. |

| 21 | Some authors merge the first two types (Córdoba de la Llave 2008, pp. 41, 43; Camacho Cruz 2018, p. 57); contra (Morales Ortiz 2010, p. 884; Aparicio Sánchez 2009, p. 1.127; Aparicio Sánchez 2010, p. 186). |

| 22 | House 71 is rectangular in plan. |

| 23 | Houses 14, 28, 63, 65, 71, 74, 81, 85, 90, 118, 126, and 127. The type is well represented in other arrabales: Ronda Oeste (Camacho Cruz and Valera Pérez 2019, p. 65; Piscina de Poniente (Cánovas Ubera et al. 2008, p. 215); Las Delicias, Carretera Palma del Río 39 (Morales Ortiz 2010, p. 884); al-Ruṣāfa (Murillo Redondo et al. 2010, p. 591); Huerta de San Pedro (Córdoba de la Llave 2008, pp. 298–99); C/Joaquín Sama Naharro (Aparicio Sánchez 2010, p. 189); Manzana 6 del Polígono de Poniente (Ruíz Nieto 2005, p. 71). |

| 24 | House 99, which had an ample vegetable garden, a well, and a waterwheel (Figure 2). This type is equally rare in other arrabales. In C/Joaquín Sama Naharro, only one house responds to the model (Aparicio Sánchez 2009, p. 1.127; Aparicio Sánchez 2010, p. 189); in Ronda Oeste it accounts for 1% of all the houses (Camacho Cruz and Valera Pérez 2019, p. 65); in al-Ruṣāfa is also found in small numbers (Murillo Redondo et al. 2010, p. 592). In Huerta de San Pedro, however, it is somewhat more common (Córdoba de la Llave 2008, pp. 298–99). |

| 25 | House 50, as far as we know, seems to have been square in plan and to have had two well-differentiated nuclei. Houses 44 and 129 are rectangular in plan and also have two well-defined nuclei. House 43, shaped like an irregular polygon, has a complex plan and is still being interpreted (Figure 2). Examples of this type were found in Manzana 6, Polígono de Poniente (Ruíz Nieto 2005, p. 71) and Ronda Oeste (Camacho Cruz et al. 2004, pp. 216, 219). |

| 26 | Unless otherwise stated, all the photographs, tables, and graphs are Laura Aparicio Sanchez’s, and plans by draftsman Ángela Mª Aparicio Ledesma’s, whom we want to thank for the time and effort spent in them. |

| 27 | See Note 15 for the only exception. |

| 28 | (Orihuela Uzal 2007, p. 329; Aparicio Sánchez 2017, pp. 183–84). |

| 29 | 7, 8, 10, 11, 20, 21, 23a, 23b, 24a, 24b, 31, 32, 40, 52, 54, 55, 56, 76, 77, 78, 82, 86, 88, 95, 102, 103, 106, 108, 109, 114, and 125. |

| 30 | In other, houses, bathing would take place in the courtyard (Reklaityte 2015, p. 275). |

| 31 | Although later in date, Islamic house IV in Palacio de Orive has an L-shaped room, 2 m2 in size, near the latrine, which was probably used for washing (Blanco Guzmán 2008, p. 314. Figure 9). |

| 32 | This is not certain in House 109. These spaces feature in the plan, but not in Table 1. |

| 33 | Small windowless rooms, capable of hosting only one person and interpreted as auxiliary kitchens, were found in the arrabal of Ronda Oeste. Access to these rooms was not directly through the courtyard, but through a large storeroom kitchen (Camacho Cruz and Valera Pérez 2019, p. 84). |

| 34 | Houses of Type 1 are found in Piscina Municipal de Poniente (Cánovas Ubera et al. 2008, p. 215); Huerta de San Pedro (Córdoba de la Llave 2008, p. 44, Figure 1); P.P. O-7 (Clapés Salmoral 2019, Figure 8), and al-Ruṣāfa (Murillo Redondo et al. 2010, pp. 595–91. Figure 285). Outside Córdoba, parallels include House 1 in Bayyāna-Pechina, dated from the emirate period to the first half of the 10th century (Castillo Galdeano and Martínez Madrid 1990, pp. 114–15. Figure 4); several in the arrabal of Arrixaca, Jardín de San Esteban, 11th–13th centuries (Robles Fernández et al. 2011, pp. 206–208, Figure 2); and in the alquería of Villa Vieja, Calasparra (Murcia) 11th-13th centuries (Orihuela Uzal 2007, p. 314. Figure 11). |

| 35 | Houses 29, 30, 37, 38, 53, 75, 84, 101, 110, 111, 113, and 124. |

| 36 | Parallels include House 14 in the arrabal of la Huerta de San Pedro, where this third space functioned as a kitchen; House 3, with a kitchen or a pantry; and House 1, with a stable (Córdoba de la Llave 2008, pp. 43–44, Figures 1, 2, 3, 5, and 6). In Ronda Oeste, in the so-called Casas del Naranjal, these rooms served as a warehouse or a workshop in House 37; a kitchen in Houses 3 and 18B, and kitchen-pantry in House 5 (Camacho Cruz et al. 2004, p. 214). The subtype is also attested in Piscina Municipal de Poniente (Cánovas Ubera et al. 2008, p. 215); P.P. O-7 (Clapés Salmoral 2019, Figure 8); al-Ruṣāfa (Murillo Redondo et al. 2010, pp. 594–602. Figure 286); and Ronda Oeste (Camacho Cruz and Valera Pérez 2019, p. 65). It is also found in considerable numbers in the arrabal of El Fortí, Denia, where it is known as Type I. These are dated to the 12th and early 13th centuries (Sentí Ribes et al. 1993, p. 277, Figure 2.1; Gisbert Santonja 2011, p. 103–6). House 4 in Bayyāna-Pechina, uses this space as a living room (Castillo Galdeano and Martínez Madrid 1990, pp. 113–14 and Figures 4 and 5). Another example is found in House VIII of the arrabal of the alcazaba in Mértola (Gómez Martínez 2001, p. 78, Figure 9). Finally, two bays of this kind, with the additional room being used as a kitchen can be recognised in House 2 in Vascos (Toledo), despite its irregular plan (Izquierdo Benito 1990, pp. 147–148. Figure 4). |

| 37 | Kitchen spaces are not always easy to recognise in the arrabales of Córdoba. In addition, the widespread anafes or portable hearths suggest that cooking could take place in the courtyards, where deposits of ash or charcoal are not rare, or in other rooms. Instances in which kitchens have been recognised include House 33 in the arrabal of Joaquín Sama Naharro, where a hearth and a bench to prepare the food were found in a space between the entrance hall and the courtyard. (Aparicio Sánchez 2010, p. 196); and Room 37 in Cercadilla, in which a room has been identified as a pantry (Castro del Río 2005, p. 122). In contrast, in the settlement of Siyāsa (XII–XIIIth centuries), in Murcia, kitchens are easy to identify, as they invariable contain three elements: a hearth, a pantry, and a bench (Navarro Palazón and Jiménez Castillo 2007a, pp. 232–37). |

| 38 | Examples can be found in Houses 1, 4, and 5 of the arrabal of Piscina Municipal de Poniente (Cánovas Ubera et al. 2008, p. 215); House 4 in Huerta de San Pedro (Córdoba de la Llave 2008, p. 44, Figures 1, 4 and 7;) Houses 2, 10A, and 42, in Casas del Naranjal—in Houses 2 and 10A the third space in the ‘outer’ bay has been identified as a kitchen (Camacho Cruz et al. 2004, pp. 214–17), like in House 18 of the arrabal of Cercadilla, where an anafe was found in this room (Fuertes Santos 2007, p. 52 and plan 5); and Houses 1.1, 2.17, 9.3, and 9.4 in al-Ruṣāfa (Murillo Redondo et al. 2010, pp. 594–602). |

| 39 | Houses 13, 22, 27, 45, 51, 83, 92, 94, 97, 112, 119, and 120. |

| 40 | In Table 3, in those houses where no parting wall to separate the alcoves have been found, the number of spaces is put down as 5/6, or 5/7 when two alcoves may have existed. |

| 41 | When the main living room is situated in the northern bay, the façade gets more sunlight in the coldest months, but a location in the southern bay makes for a cooler room in the summer (Navarro Palazón and Jiménez Castillo 2007a, pp. 252–53; García-Pulido 2015, pp. 273, 241). |

| 42 | Houses 9, 15, 64, 66, 104, and 117. |

| 43 | His house is described in detail in Aparicio Sánchez (2020, pp. 187–88, 190, 192, Figures 20 and 24). House 17 in Casas del Naranjal, Ronda Oeste, responds to this model (Camacho Cruz et al. 2004, p. 217). |

| 44 | A similar arrangement is found in House 2 in Bayyāna, Pechina; the third bay, with a corridor that links the entrance hall to the courtyard and a room open to the courtyard, is attached to the ‘outer’ bay (entrance hall, latrine, and kitchen). In this case, the house formed a larger domestic unit with House 3 (Castillo Galdeano and Martínez Madrid 1990, p. 114. Figures 1 and 4). In Córdoba, the model is found in Houses 7 and 25 of Cercadilla (Castro del Río 2005, p. 125). |

| 45 | Two latrines are found in a house in Block 6, Polígono de Poniente (Ruíz Nieto 2005, pp. 71–72) and in Houses 16 and 34 of the arrabal Casas del Naranjal, Ronda Oeste (Camacho Cruz et al. 2004, pp. 217, 219). This could suggest that the house was inhabited by a large family (Reklaityte 2015, p. 279). |

| 46 | Houses 33 and 36 and 37 and 39 may form other rows. |

| 47 | See details in (Aparicio Sánchez 2020, pp. 180–87, Figures 11–16). |

| 48 | For details of the partition of Houses 54 and 55 see (Aparicio Sánchez 2021, pp. 30–31, Figure 4a–c). |

| 49 | This issue was addressed in a recent paper (Aparicio Sánchez 2021), to which these new examples can be added. |

| 50 | It is important to emphasise that water wells were of such importance for Islamic society that partitioning was not considered an option. Therefore, when houses were subdivided, both units shared ownership over this resource (Carmona González 2015, p. 222). |

| 51 | House 46 of the arrabal in Manzana 15, P.P. O-7, presents a similar example, probably also the result of the division of a larger house (Vázquez Navajas 2013, pp. 36, 37, Figure 3). Two more examples were identified in Ronda Oeste (Camacho Cruz and Valera Pérez 2019, p. 76, Plate 15). |

| 52 | See more details in Aparicio Sánchez 2021 (pp. 29, 31, 32, Figure 2C, D). |

| 53 | This is also attested in other arrabales in Córdoba, such as Ronda Oeste (Camacho Cruz et al. 2004, pp. 217–21) and al-Ruṣāfa al-Rusafa (Murillo Redondo et al. 2010, pp. 595, 599, 603, Figure 291). |

| 54 | According to Mohammed, the owner of a wall is compelled to share it as a parting wall with whomever wants to build next to it, a recommendation that was followed in al-Andalus, at least during the Umayyad caliphate period (Carmona González 2015, pp. 210–11). |

| 55 | The most significant is the arrabal El Fortí, Denia, known for its regular, pseudo-orthogonal street layout, with straight and hierarchised streets, a well-laid-out sewage system, and regular blocks (Gisbert Santonja 2011, p. 103). The houses documented in El Fortí include Type I, formed by two built bays on either side of a central courtyard, and a distribution of spaces that greatly resembles that of our Type 1; the site is dated to the 12th and early 13th centuries (Sentí Ribes et al. 1993, p. 277, Figure 2.1; Gisbert Santonja 2007, pp. 212–13, Plates 9 and 10; Gisbert Santonja 2011, pp. 103–6). Other examples are found in a sector of the arrabal of Arrixaca, Jardín de San Esteban, dated to the 11th–13th centuries (Robles Fernández et al. 2011, pp. 206–8, Figure 2); a house in Bayyāna-Pechina, built during the emirate period, which was still in place in the first half of the 10th century (Castillo Galdeano and Martínez Madrid 1990, pp. 114–15. Figure 4); some in the alquería of Villa Vieja, Calasparra (Murcia), dated to the 11th–13th centuries (Orihuela Uzal 2007, p. 314. Figure 11); the alquería of Bofilla, 11th–13th centuries (López Elum 1994); the alcazaba of Mértola, 12th-13th century, although this is the result of the partition of a larger house (Gómez Martínez 2001, p. 78, Figure 9); the alquería of Cairola (Vall d´Ebo, Valencia), which postdates the Christian conquest, in this case with a second storey over the ‘outer’ bay (Torró Abad and Ivars Baidal 1990, pp. 77–78, Figures 6 and 7); and finally, in Vascos, Toledo (Izquierdo Benito 1990, pp. 147–48. Figure 4). |

| 56 | As noted, this arrabal is in many ways similar to ours, including a pseudo-orthogonal plan with straight and hierarchised streets and regular city blocks (Gisbert Santonja 2011, p. 103). A large number of the houses documented there are strongly reminiscent of our Type 1: two built bays separated by a central courtyard. It has been argued that these houses were inhabited by craftspeople and merchants (Gisbert Santonja 2007, pp. 212–13, Plates 9 and 10; Gisbert Santonja 2011, pp. 103–6). |

| 57 | For a study of house partitions in al-Andalus see Navarro Palazón and Jiménez Castillo (2011). |

| 58 | Details of house partitions and the occupation of streets see (Aparicio Sánchez 2021, pp. 29, 31, 32, Figure 2C, D). |

| 59 | Facilitated by the complex system of Islamic wills and by the legal doctrine that favoured private agreements between neighbours and the shared use of parting walls, leading to organic urban growth (Navarro Palazón and Jiménez Castillo 2004, p. 239; Carmona González 2015, pp. 209–11). |

| 60 | In Ronda Oeste, some actions that encroached upon public roads suggest an incipient process of saturation, including the extension of a baths building and a house (Camacho Cruz 2018, p. 59). |

| 61 | Other examples in caliphate-period arrabales in Córdoba include: Street A, Block 15, in P.P. O-7 (Liébana Mármol 2008); Unidad de ejecución MA-4B Las Delicias, Carretera Palma del Río 39 (Morales Ortiz 2010, p. 882. Figure 1); Streets 6 and 10 in Huerta de San Pedro (Córdoba de la Llave 2006, p. 297); another one in Ronda Oeste (Camacho Cruz 2018, p. 59. Figura 12); and several in al-Ruṣāfa (Murillo Redondo et al. 2010, p. 589). Although they are all dated to the caliphate period, we must also mention small emirate-period adarves in the arrabal of Šaqunda, Saqunda, abandoned in 811 (Casal García 2008, pp. 127, 129. Plates 3 and 5). |

| 62 | In Cercadilla (Castro del Río 2005, p. 146); Ronda Oeste (Camacho Cruz and Valera Pérez 2019, nota 6) and Block 14 in P.P. O-7, although in the latter case, a rammed-earth wall, 5 m tall was found (Clapés Salmoral 2013, p. 92, Note 15). A possible staircase was attested in House 1 in Piscina Municipal de Poniente; it is a square feature situated in one of the ends of the portico (Cánovas Ubera et al. 2008, pp. 206, 216). |

| 63 | Like the feature found in the entrance hall of House 119 (Figure 18). |

| 64 | In House 12 (Figure 20). |

| 65 | A vertical drainpipe running down the façade of House 85 wall must have evacuated rain water from the terrace (Aparicio Sánchez 2008b, p. 255). |

References

- Acién Almansa, Manuel, and Antonio Vallejo Triano. 1998. Urbanismo y estado islámico: De Corduba a Qurṭuba—Madīnat al-Zahrā’. In Genèse de la ville islamique en al-Andalus et au Maghreb occidental. Edited by Patrice Cressier and Mercedes García Arenal. Madrid: Casa de Velázquez, Consejo Superior de Investigaciones Científicas, pp. 107–36. [Google Scholar]

- Aparicio Sánchez, Laura. 2008a. La planificación urbanística en la Córdoba califal. Los arrabales noroccidentales. In Actas do IV Congresso de Arqueología Peninsular. Edited by Nuno Ferreira Bicho. Faro: Centro de Estudos de Património; Universidade do Algarve, pp. 29–38. [Google Scholar]

- Aparicio Sánchez, Laura. 2008b. Redes de abastecimiento y evacuación de aguas en los arrabales califales de Córdoba. Arte, Arqueología e Historia 15: 237–56. [Google Scholar]

- Aparicio Sánchez, Laura. 2009. Actuación Arqueológica Preventiva en la C/Joaquín Sama Naharro esquina a Músico Cristóbal de Morales, de Córdoba. In Anuario Arqueológico de Andalucía, 2004.1. Sevilla: Junta de Andalucía, pp. 1.124–1.142. [Google Scholar]

- Aparicio Sánchez, Laura. 2010. El arrabal islámico de la C/Joaquín Sama Naharro, Córdoba. Arte Arqueología e Historia 17: 183–202. [Google Scholar]

- Aparicio Sánchez, Laura. 2017. La vivienda califal en los barrios occidentales de Córdoba. Al-Mulk Anuario de Estudios Arabistas 15: 175–214. [Google Scholar]

- Aparicio Sánchez, Laura. 2020. Estudio de seis viviendas del arrabal califal Huerta de Santa Isabel (Córdoba). In Más allá de las murallas. Contribución al estudio de las dinámicas urbanas en el sur de al-Andalus. Edited by Mª Mercedes Delgado Pérez. Madrid: La Ergástula, pp. 167–98. [Google Scholar]

- Aparicio Sánchez, Laura. 2021. Los primeros indicios de saturación en los arrabales cordobeses. La partición de las viviendas y la creación de adarves. In Actas VI Congreso de Arqueología Medieval (España-Portugal). Coordinator Manuel Retuerce Velasco. Ciudad Real: Asociación Española de Arqueología Medieval, pp. 27–32. [Google Scholar]

- Aparicio Sánchez, Laura, and José Antonio Riquelme Cantal. 2008. Localización de uno de los arrabales noroccidentales de Córdoba Califal. Estudio urbanístico y zooarqueológico. Cuadernos de Madīnat al-Zahrā’ 6: 93–131. [Google Scholar]

- Arnold, Félix. 2008. La almunia de al-Rummanīyya. Resultado de una documentación arquitectónica. Cuadernos de Madīnat al-Zahrā’ 6: 181–204. [Google Scholar]

- Blanco Guzmán, Rafael. 2008. Algunas precisiones sobre la Qurṭuba tardoislámica. Una mirada a la arquitectura doméstica de al-Rabaḍ al-Šarquī. Anales de Arqueología Cordobesa 19: 293–322. [Google Scholar]

- Cabrera Muñoz, Emilio. 1994. Ornato del mundo. In Córdoba Capital. 1. Historia. Coordinator Emilio Cabrera Muñoz. Córdoba: Caja Provincial de Ahorros de Córdoba, pp. 113–28. [Google Scholar]

- Cabrera Muñoz, Emilio. 1999. Aproximación a la imagen de la Córdoba islámica. In Córdoba en la Historia: La construcción de la urbe. Edited by Francisco R. García Verdugo and Francisco Acosta Ramírez. Córdoba: Ayuntamiento de Córdoba y Fundación La Caixa, pp. 111–28. [Google Scholar]

- Camacho Cruz, Cristina. 2018. Evolución del parcelario doméstico y su interacción con la trama urbana: El caso de los arrabales califales de Córdoba. Arqueología y Territorio Medieval 25: 29–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camacho Cruz, Cristina, and Rafael Valera Pérez. 2019. Espacios domésticos en los arrabales occidentales de Qurṭuba: Tipos de viviendas, análisis y reconstrucción. Antiqvitas 31: 59–92. [Google Scholar]

- Camacho Cruz, Cristina, Miguel Haro Torres, José Manuel Lara Fuillerat, and César Pérez Navarro. 2004. Intervención arqueológica de urgencia en el arrabal hispanomusulmán “Casas del Naranjal”. Yacimiento “D”. Ronda Oeste de Córdoba. In Anuario Arqueológico de Andalucía 2001. Sevilla: Junta de Andalucía, Tomo III, vol. 1, pp. 210–30. [Google Scholar]

- Cánovas Ubera, Álvaro, Elena Castro del Río, and Maudilio Moreno Almenara. 2008. Análisis de los espacios domésticos en un sector de los arrabales occidentales de Qurṭuba. Anejos de Anales de Arqueología Cordobesa 1: 201–22. [Google Scholar]

- Carmona González, Alfonso. 2015. Casos de litigios de vecindad en al-Andalus. In La casa medieval en la península ibérica. Edited by Mª Elena Díez Jorge and Julio Navarro Palazón. Madrid: Sílex, pp. 209–28. [Google Scholar]

- Casal García, María Teresa. 2008. Características generales del urbanismo cordobés de la primera etapa emiral: El arrabal de Šaqunda. Anejos de anales de arqueología cordobesa 1: 109–34. [Google Scholar]

- Castejón, Rosario. 1961–1962. Madinat al-Zahra en los autores árabes. Al-Mulk: Anuario de Estudios Arabistas 2: 119–56. [Google Scholar]

- Castillo Galdeano, Francisco, and Rafael Martínez Madrid. 1990. La vivienda hispanomusulmana en Bayyāna-Pechina (Almería). In La casa hispano-musulmana. Aportaciones de la arqueología. Coordinators Jesús Bermúdez López and André Bazzana. Granada: Patronato de la Alhambra y Generalife, Casa de Velázquez, pp. 111–27. [Google Scholar]

- Castro del Río, Elena. 2005. El arrabal de época califal de la zona arqueológica de Cercadilla: La arquitectura doméstica. Córdoba: Servicio de publicaciones Universidad de Córdoba. [Google Scholar]

- Castro del Río, Elena. 2010. El arrabal de Cercadilla. Córdoba. In Monografías de Arqueología Cordobesa. Córdoba: UCOPress, vol. II, pp. 615–21. [Google Scholar]

- Clapés Salmoral, Rafael. 2013. Un baño privado en el arrabal occidental de Madīnat Qurṭuba. Arqueología y Territorio Medieval 20: 97–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clapés Salmoral, Rafael. 2019. La formación y evolución del paisaje suburbano en época islámica: Un ejemplo en el arrabal occidental de la capital omeya de Al-Andalus (Córdoba). Arqueología y Territorio Medieval 26: 31–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clapés Salmoral, Rafael. 2020. La arquitectura del poder: Los edificios omeyas del “Tablero Alto” y su integración en la almunia de al-Ruṣāfa (Córdoba). Arqueología y Territorio Medieval 27: 313–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Córdoba de la Llave, Ricardo. 2006. Excavación arqueológica en el yacimiento califal de Huerta de San Pedro (Córdoba). In Anuario Arqueológico de Andalucía 2003. Sevilla: Junta de Andalucía, pp. 295–304. [Google Scholar]

- Córdoba de la Llave, Ricardo. 2008. Viviendas adosadas andalusíes del yacimiento califal “Huerta de San Pedro” (Córdoba). In Actas do IV Congresso de Arqueología Peninsular. Edited by Nuno Ferreira Bicho. Faro: Centro de Estudos de Património; Universidade do Algarve, pp. 39–50. [Google Scholar]

- Fuertes Santos, Mª del Camino. 2007. El Sector Nororiental del arrabal califal del yacimiento de Cercadilla. Análisis urbanístico y arquitectónico. Arqueología y Territorio Medieval 14: 49–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García Gómez, Emilio. 1965. Notas sobre topografía Cordobesa en los anales de al-Haquem II. Al-Andalus XXX: 319–79. [Google Scholar]

- García-Pulido, Luís José. 2015. Respuestas de las viviendas andalusíes a los condicionantes climáticos. Algunos casos de estudio. In La casa medieval en la península ibérica. Edited by Mª Elena Díez Jorge and Julio Navarro Palazón. Madrid: Sílex, pp. 229–67. [Google Scholar]

- Gisbert Santonja, Josep Antoni. 2007. Dāniya, reflejo del Mediterráneo. Una mirada a su urbanismo y arqueología desde el mar (s. XI). In Almería, “puerta del Mediterráneo” (ss. XI–XII). Coordinator Ángela Suárez Márquez. Sevilla: Junta de Andalucía, pp. 203–30. [Google Scholar]

- Gisbert Santonja, Josep Antoni. 2011. Al-Idrīsī y las ciudades de Sharq al-Andalus, Dāniya-Dénia-: Ensayo de conexión entre la evidencia arqueológica y el mundo del geógrafo. In El mundo del geógrafo ceutí Al-Idrīsī. Coordinator Francisco Herrera Clavero. Ceuta: Instituto de Estudios Ceutíes, pp. 79–121. [Google Scholar]

- Gómez Martínez, Susana. 2001. Mértola islámica. Los espacios de vivienda. In Actas I Jornadas de cultura islámica. Almonaster La Real, Huelva. Edited by Juan Aurelio Pérez Macías and Yolanda Benabat Hierro. Sevilla: Junta de Andalucía, pp. 65–98. [Google Scholar]

- Ibn ‘Iyāḍ, Muḥammad. 1998. Madāhib al-ḥukkām fī nawāzil al-aḥkām (La actuaciōn de los jueces en los procesos judiciales). Translated by Delfina Serrano. Madrid: CSIC. [Google Scholar]

- Ḥawqal, Ibn. 1971. Configuración del mundo (fragmentos alusivos al Magreb y España). Translated by María José Romani Suay. Valencia: Anubar. [Google Scholar]

- Ḥayyān, Ibn. 1981. Crónica del califa ‘Abdarraḥmān III an-Nāṣir entre los años 912 y 942 (al-Muqtabis V). Translated by María Jesús Viguera, and Federico Corriente. Zaragoza: Anubar. [Google Scholar]

- Izquierdo Benito, Ricardo. 1990. La vivienda en la ciudad hispanomusulmana de Vascos (Toledo). Estudio arqueológico. In La casa hispano-musulmana. Aportaciones de la arqueología. Coordinator Jesús Bermúdez López and André Bazzana. Granada: Patronato de la Alhambra y Generalife, Casa de Velázquez, pp. 147–62. [Google Scholar]

- Jiménez Castillo, Pedro. 2013. Murcia: De la Antigüedad al Islam. Ph.D. thesis, Universidad de Granada, Granada, Spain. [Google Scholar]

- León Muñoz, Alberto. 2018. El urbanismo de Córdoba andalusí. Reflexiones para una lectura arqueológica de la ciudad islámica medieval. Post-Classical Archaeologies 8: 117–64. [Google Scholar]

- Liébana Mármol, José Luís. 2008. Informe de la Intervención Arqueológica Preventiva en la parcela M-15 del Plan Parcial O-7. Informe administrativo depositado en la Delegación de Cultura de Córdoba. [Google Scholar]

- López Cuevas, Fernando. 2013. La Almunia Cordobesa, entre las fuentes historiográficas y arqueológicas. Revista Onoba, 243–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López Elum, Pedro. 1994. La alquería islámica en Valencia. Estudio arqueológico de Bofilla (siglos XI a XIV). Valencia: Ed. P. López Elum. [Google Scholar]

- Manzano Moreno, Eduardo. 2019. La corte del califa. Cuatro años en la Córdoba de los omeyas. Barcelona: Crítica. [Google Scholar]

- Morales Ortiz, Silvia María. 2010. Informe de resultados de la actividad arqueológica preventiva correspondiente a la apertura de cuatro viales en la unidad de ejecución manzana-4B, “Las Delicias”, carretera Palma del Río nº39, Córdoba, Anuario Arqueológico de Andalucía 2005. Sevilla: Junta de Andalucía, pp. 878–88. [Google Scholar]

- Murillo Redondo, Juan Francisco, María Teresa Casal García, and Elena Castro del Río. 2004. Madīnat Qurṭuba. Aproximación al proceso de formación de la ciudad emiral y califal a partir de la información arqueológica. Cuadernos de Madīnat al-Zahrā’ 5: 257–90. [Google Scholar]

- Murillo Redondo, Juan Francisco, Fátima Castillo, Elena Castro, María Teresa Casal, and Teresa Dortez. 2010. La almunia y el arrabal de al-Ruṣāfa, en el Ŷānib al-Garbī de Madīnat Qurṭuba. In Monografías de Arqueología Cordobesa. Córdoba: UCOPress, vol. II, pp. 565–615. [Google Scholar]

- Navarro Palazón, Julio, and María Elena Díez Jorge. 2015. Introducción a la casa medieval. In La casa medieval en la península ibérica. Edited by Mª Elena Díez Jorge and Julio Navarro Palazón. Madrid: Silex, pp. 9–15. [Google Scholar]

- Navarro Palazón, Julio, and Pedro Jiménez Castillo. 1996. Plantas altas en edificios andalusíes. La aportación de la arqueología. Actas del coloquio Formas de habitar e alimentaçâo no Sul da Penísula Ibérica (Idade Média) Arqueologia Medieval 4: 107–38. [Google Scholar]

- Navarro Palazón, Julio, and Pedro Jiménez Castillo. 2003. Sobre la ciudad islámica y su evolución. In Estudios de arqueología dedicados a la profesora Ana María Muñoz Amilibia. Edited by Sebastián F. Ramallo Asencio. Murcia: Universidad de Murcia, pp. 319–81. [Google Scholar]

- Navarro Palazón, Julio, and Pedro Jiménez Castillo. 2004. Evolución del paisaje urbano andalusí. De la medina dispersa a la saturada. In Paisaje y naturaleza en Al-Andalus. Granada: Fundación El Legado Andalusí, pp. 232–67. [Google Scholar]

- Navarro Palazón, Julio, and Pedro Jiménez Castillo. 2007a. Siyâsa. Estudio arqueológico del despoblado andalusí (ss. XI–XIII). Murcia: El legado andalusí. [Google Scholar]

- Navarro Palazón, Julio, and Pedro Jiménez Castillo. 2007b. Las ciudades de Alandalús. Nuevas perspectivas. Zaragoza: Instituto de Estudios Islámicos y del Próximo Oriente. [Google Scholar]

- Navarro Palazón, Julio, and Pedro Jiménez Castillo. 2007c. Evolution of the Andalusi Urban Landscape: From the Dispersed to the Saturated Medina. In Revisiting Al-Andalus. Perspectives on the Material Culture of the Islamic Iberia and Beyond. Edited by Glaire D. Anderson and Mariam Rosser-Owen. Leiden-Boston: Brill, pp. 115–42. [Google Scholar]

- Navarro Palazón, Julio, and Pedro Jiménez Castillo. 2010. El agua en la ciudad andalusí. In Actas del II Coloquio Internacional Irrigación, Energía y Abastecimiento de Agua. La cultura del agua en el arco mediterráneo. Alcalá de Guadaira: Ayuntamiento de Alcalá de Guadaira, pp. 147–254. [Google Scholar]

- Navarro Palazón, Julio, and Pedro Jiménez Castillo. 2011. La partición de fincas como síntoma de saturación en la ciudad andalusí: Los ejemplos de Siyâsa y Murcia. In Cristãos e Muçulmanos na Idade Média Peninsular. Encontros e desencontros. Lisboa-Faro: Libros Pórtico, pp. 79–94. [Google Scholar]

- Navarro, Palazón Julio, and Pedro Jiménez Castillo. 2022. The Expansion of Urban Layouts over Cultivated Spaces in the Medieval Islamic West. Dar. Bi-annual international journal of architecture in the Islamic world. Special Issue «The Cities of the Islamic World» 2: 63–76. [Google Scholar]

- Navarro Palazón, Julio, and Carmen Trillo San José, eds. 2018. Almunias. Las fincas de las élites en el Occidente islámico: Poder, solaz y producción. Granada: Editorial Universidad de Granada/UCOPress/Editorial Universidad de Sevilla/CSIC (Colección Historia, nº 357). [Google Scholar]

- Orihuela Uzal, Antonio. 2007. La casa andalusí: Un recorrido a través de su evolución. Artigrama 22: 299–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reklaityte, Ieva. 2015. Una aproximación arqueológica a la hidráulica doméstica de las ciudades de al-Andalus. In La casa medieval en la península ibérica. Edited by Mª Elena Díez Jorge and Julio Navarro Palazón. Madrid: Sílex, pp. 269–88. [Google Scholar]

- Robles Fernández, Alfonso, José A. Sánchez Pravia, and Elvira Navarro Santa-Cruz. 2011. Arquitectura residencial andalusí y jardines en el arrabal de la Arrixaca. Breve síntesis de las excavaciones arqueológicas realizadas en el jardín de San Esteban, Murcia (2009). Verdolay 13: 205–19. [Google Scholar]

- Rodero Pérez, Santiago, and Juan Antonio Molina Mahedero. 2006. Un sector de la expansión occidental de la Córdoba islámica: El arrabal de la carretera de Trassierra (I). Romula 5: 219–94. [Google Scholar]

- Ruíz Nieto, Eduardo. 2005. El ensanche occidental de la Córdoba califal. Meridies 7: 59–74. [Google Scholar]

- Sentí Ribes, María Assumpció, Gisbert Santonja, Josep Antoni, and María Josepa Berenguer Llopis. 1993. L´espai privat al Raval de Daniya (El Fortí.Dénia). In Actas IV Congreso de Arqueología Medieval Española, 4–9 de octubre 1993. Alicante: Sociedades en transición, vol. 2, pp. 277–85. [Google Scholar]

- Torres Balbás, Leopoldo. 1987. La Edad Media. In Resumen histórico del urbanismo en España. Edited by Antonio García y Bellido, Leopoldo Torres-Balbás, Luís Cervera, Fernando Chueca and Pedro Bidagor. Madrid: Instituto de Estudios de Administración Local, pp. 68–172. [Google Scholar]

- Torró Abad, Josep, and Josep Ivars Baidal. 1990. La vivienda rural mudéjar y morisca en el sur del País Valenciano. In La casa hispano-musulmana. Aportaciones de la arqueología. Coordinator Jesús Bermúdez López and André Bazzana. Granada: Patronato de la Alhambra y Generalife, Casa de Velázquez, pp. 73–97. [Google Scholar]

- Vázquez Navajas, Belén. 2013. El agua en la Córdoba andalusí. Los sistemas hidráulicos de un sector del Ŷānib al-Garbī durante el Califato Omeya. Arqueología y Territorio Medieval 20: 31–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vázquez Navajas, Belén. 2022. ¿Cómo se construyeron los arrabales califales de la Córdoba omeya? Aportaciones desde la hidráulica. In Una nueva mirada a la formación de al-Andalus. La arabización y la islamización desde la interdisciplinariedad, Documentos de Arqueología medieval 18. Edited by Eneko López Martínez de Marigorta. Basque Country: Universidad del País Vasco, pp. 171–90. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).