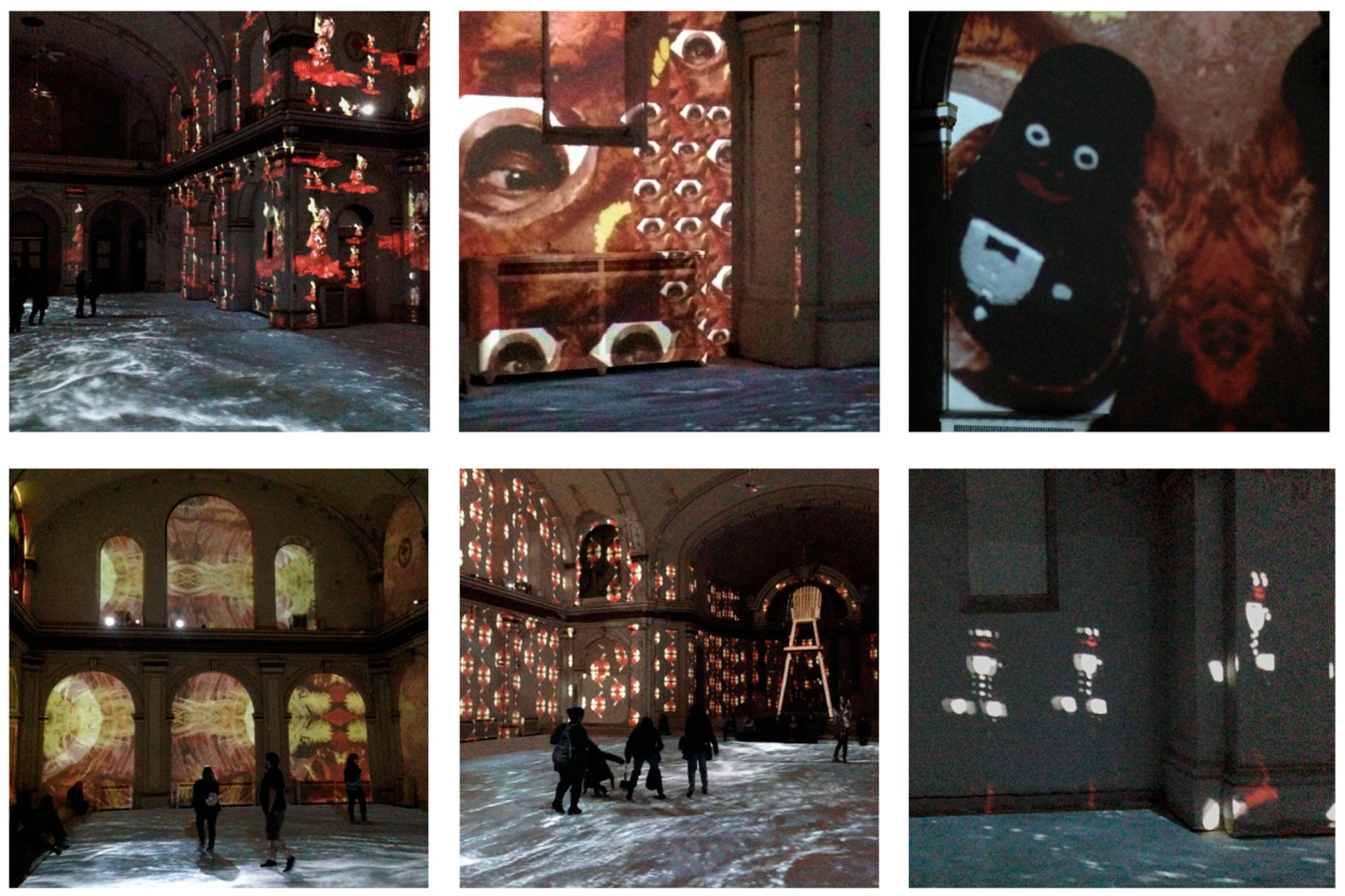

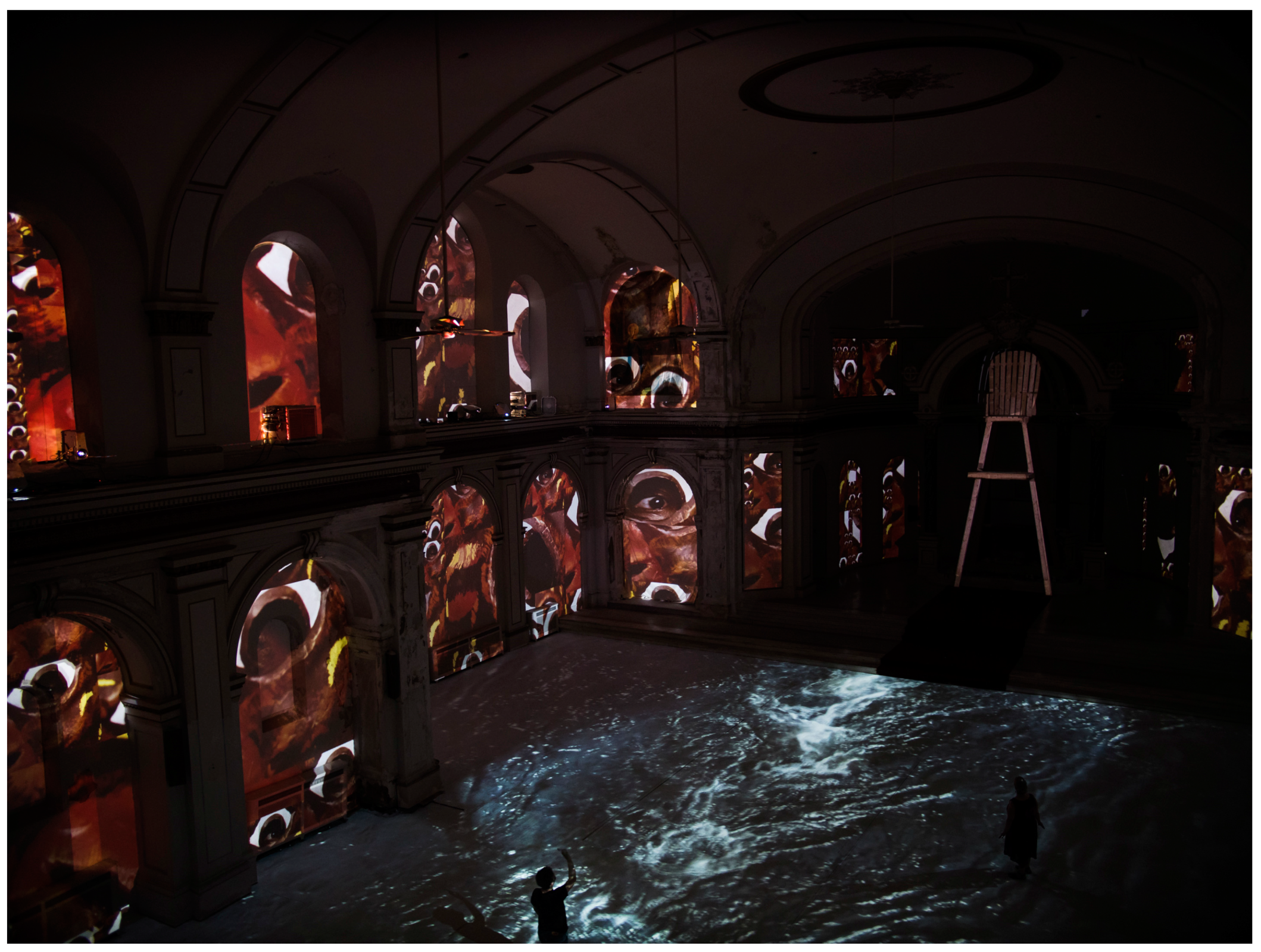

On a very rainy morning in September 2018, I visited the space of a deconsecrated church on the east side of Kansas City to see Nick Cave’s Hy-Dyve video installation. Upon opening the heavy nave doors, I discovered I was little prepared for the encounter with the frothing sea of images covering the floor and walls of this former religious site. Even though I had seen photographs of the installation on social media, I found the experience highly destabilizing. The images of gushing water projected on the floor momentarily impaired my balance, adding to the sense of confusion triggered by the vast emptiness of the church. Throbbing percussive sounds further enhanced the feeling of unfamiliarity. Video vignettes following different timelines unfolded on the dilapidating church walls, engendering a sense of temporal displacement. Despite the mystifying environment and the non-linear image sequences, one had little difficulty in recognizing all too familiar signs of subjugation and surveillance such as a trapped black figurine or the close-up of an eye anxiously surveying the surroundings from behind a mask.

Hy-Dyve powerfully evoked the sensation of being profiled and pursued, conjuring both distant and recent memories of racial injustice. Unlike most immersive environments, it offered a grounding in past and present socio-political realities rather than an escape into an imaginary realm. Enveloped in darkness, the altar canopy of the church did not confer any solace. Instead, it served as a ghostly frame for an oversized lifeguard chair. Left empty, the grandiose seat triggered more feelings of anxiety than protection. Its imposing height evoked a high vantage point from which an invisible eye of a surveilling authority might scrutinize the church interior. In conjunction with the installation title which offers a playful spin on the term “high dive”, the vacant chair suggested an uncertain scenario in which one might need to take a leap of faith and jump into the unknown, or, in this instance, risk being seen by an authority figure which may or may not be impartial. Given the combination of video images and sculptural elements, the environment was both absorbing and disruptive. It called the viewers’ attention not only to mesmerizing projections but also to the dilapidating structure of the deconsecrated church. A space that may once have felt comforting was now unsettling, confronting visitors with an unfamiliar territory in which they would need to reorient their senses and make sense of ambiguous iconographic signs.

Nick Cave is best known for his carnivalesque

Soundsuits, wearable sculptures made of eclectic materials such as beads, buttons, feathers, or hair.

1 Primarily displayed in museums as clothing items garnering the bodies of mannequins rather than as performative objects, they lose a degree of their critical edge and affective potential. While it is well-known that Cave designed his first twig soundsuit in 1992 in response to the beating of Rodney King, the increasingly exuberant aesthetics of his wearable sculptures and their joyful celebration of life have partly eclipsed the bleak realities which inspired them. Sensing that the institutionalization of his practice may take away from its disruptive potential, Cave has worked increasingly harder at integrating

Soundsuit performances into public spaces. He has also invited LGBTQ youth and victims of domestic abuse to imbue them with more specific meanings. Most notable among his community-oriented projects are the

Dance Labs organized in partnership with the Museum of Contemporary Art Detroit in 2015 and

As Is, a 2016 performance he prepared over the course of eight months in Shreveport, Louisiana. For both, he established long-term collaborations with dancers, musicians, and members of local communities. Performers with different backgrounds brought Cave’s costumes to life in jubilant dances. In tandem with these endeavors to broaden participation in the design and performative activation of his

Soundsuits, Cave has reoriented his practice towards staging immersive installations such as

Hy-Dyve that can serve as ground for public congregations. Such works continue to build on cross-cultural references and flamboyant materials yet place viewers in more tense relation to processes of identity negotiation. Preventing voyeuristic identification, Cave’s installations have disorienting qualities and ask visitors to have a more vivid encounter with the experience of blackness, or, more generally, the sensation of being perceived as different.

Composed of 14 video channels,

Hy-Dyve was originally displayed in “Until”, Cave’s large-scale exhibition at MASS MoCA in 2016. Taking its name from the phrase “innocent until proven guilty”, the exhibition featured seemingly joyous environments composed of a myriad of scintillating and colorful objects in the midst of which visitors could discover racist memorabilia and symbols of violence.

2 In this article, I address the Kansas City iteration of

Hy-Dyve, which was part of “Open Spaces”, a festival hosted in alternative art venues in 2018 (

Figure 1).

3 The work is based on projection mapping, a technique used to project video images onto buildings and three-dimensional objects, thus transforming their surface into an illusionistic field of light. While the term for it has come into widespread use only in the last 15 years with its proliferation in the entertainment industries, the technique has deep roots in the art field. Stan VanDerBeek used the domed ceiling of his Movie-Drome construction for expanded cinema experiments in the mid-1960s, Robert Whitman projected cinematic images onto performers’ bodies in

Prune. Flat. in 1965, and Jeffrey Shaw, together with Theo Botschuijver and Sean Wellesley-Miller, projected film and slides onto an inflatable structure for

Movie Movie in 1969. More recently, artists such as Tony Oursler, Rafael Lozano-Hemmer, and Krzysztof Wodiczko have resorted to projection mapping as a means of enhancing the affective impact of their works and revealing the psychological qualities of objects and buildings. The technique serves similar purposes in Cave’s staging of

Hy-Dyve. It creates an immersive space in which viewers are highly aware of the physicality of their surroundings while observing a shifting field of images. In the case of its display in a church space, the projections permeate the arched niches, enhancing their visibility and taking advantage of their depth to heighten the illusionistic attributes of the images.

Taking note of the sensory and conceptual elements of Hy-Dyve, I discuss the ambivalence of this installation’s symbolism in the context of the church and the friction it establishes between the overseeing eye of authority and the gaze of the Other behind the mask confronting surveillance and objectification. Decoding the artist’s references to racial profiling, I offer a semiotic analysis of Hy-Dyve in terms of its critique of scopic regimes that perpetuate identity bias. I argue that the immersive experience the installation fosters does not undermine critical reflection and I build on Gilles Deleuze’s theory of close-up operations in order to show how Cave disrupts processes of identification and undermines binary oppositions between the subject and object of perception. I also examine the multivalent meanings of his Soundsuits which make an episodic appearance in this video installation and function both as signs of otherworldly alterity and markers of more specific gender and racial differences. In Hy-Dyve, Cave brings these wearable sculptures in closer dialogue with the particularities of black experience while simultaneously maintaining the openness of their signification to elicit affective connections. Thus, he maintains his affinity with post-black art while concomitantly embracing a more explicitly political agenda stirred by ongoing abuses of power and racial injustices. Two vectors of his practice meet in Hy-Dyve: the ecstatic performances with Soundsuits celebrating fluid transformations of identity and the recontextualization of visual motifs of subjugation meant to underscore persistent racial tensions.

1. Nick Cave’s Performative Disguises beyond the Post-Black Art Debate

Hy-Dyve is an installation about assuming risks while navigating the treacherous path of making one’s differences visible in public space. At a time of repeated police assaults against African-Americans, Nick Cave opens up the experience of embodying his

Soundsuits to a broader public by conceiving environments that metaphorically convey the anxiety of entrapment in social spaces that are still marked by vestiges of racial segregation. By immersing viewers in the disorienting space of installations created for the “Until” exhibition at MASS MoCA, the artist avowed that he aimed to give the public a sense of what it feels like to be in “the metaphorical belly of a

Soundsuit” and unveil the “disturbing” experiences which motivate him to create art (

Gleisner 2017). This sensation of captivity that Cave wanted to provoke can be associated both with the experience of living in a society in which racism is still pervasive and with the suffering of African slaves transported in inhuman conditions in the belly of ships during the Middle Passage. Immersive technologies offer the possibility of acquiring a more embodied connection with the experience of those who are dispossessed, subjugated, or marginalized. Similar to Cave, Alejandro G. Iñarritu has conceived

Carne y Arena (2017), a virtual reality environment in which exhibition visitors can relate to the experience of Central American and Mexican migrants at a more visceral level. While immersion is generally associated with spectacle culture, it can also serve activist agendas by confronting participants with disquieting experiences that can bring them in closer touch with the lives of those who face discrimination. The language of the senses can at times bypass barriers imposed by cultural, racial, and social biases. Instead of celebrating differences, primarily through the proliferation of colorful suits that undermine identity categorization, Cave has increasingly focused on showing a less joyful side of the experience of disguise. Anchored around visual tropes with unstable meaning,

Hy-Dyve configures an environment in which doubt and insecurities prevail over the jouissance generally inspired by his soundsuit performances.

At the turn of the millennium, Cave’s practice easily aligned with “post-black” art, a term applied by Thelma Golden to works by a young generation of artists who resisted the classification of their practice in terms of “black art” and built on Western and non-Western influences in order to unsettle categories and genealogies that impose constraints on their self-expression (

Golden 2001). Artists associated with this post-black attitude include Glenn Ligon, an originator of the term together with Golden, as well as Mark Bradford, Rashid Johnson, Sanford Biggers, and Julie Mehretu. Three of Cave’s

Soundsuits were included in “Frequency” (2005), one of the five non-thematic exhibitions organized at Studio Museum in conjunction with attempts at questioning preconceived notions of black aesthetics. Through their resemblance with textile and raffia suits worn in African dances and their concomitant celebration of differences that elude specific cultural and racial markers, the

Soundsuits easily aligned with the post-black tendency which privileged hybridity and favored departures from unitary definitions of blackness.

The “post-black” term proved controversial and garnered extensive attention from both artists and scholars. As Cathy Byrd explains, the term easily risked congealing into another prescriptive category and even artists associated with it were skeptical of its validity (

Byrd 2002). In a more recent take on this debate, Margo Natalie Crawford points out that Golden’s proposal of the “post-black” term was accompanied by a “wink”, a slightly ironical take on the idea of moving completely beyond racial issues (

Crawford 2015). Yet, Crawford is concerned by the depoliticizing implications of this concept even under these terms, arguing that it dilutes the tension involved in black aesthetic expression and overshadows continuities between the Black Art Movement of the 1960s and 1970s and the practice of artists belonging to more recent generations. While her critique is valid, it does not fully account for the fact that “post-black” art was conceived in response to the multiculturalist policies pervading American art museums in the 1990s. Under the guise of promoting diversity, art institutions organized exhibitions framed around racial categories which enforced a fixed set of aesthetic and ideological expectations from artists representative of minority identities. In this climate, Golden refused the title of curator of African American Art at the Whitney Museum and oriented her attention to conversations with artists whose practice eluded the increasingly rigid “black art” category.

4 Cave’s

Soundsuits were consonant with this movement towards thinking about issues of identity beyond cultural specificity. They covered the body of performers in their entirety and suggested that an openness towards Otherness in the absence of easily recognizable racial or gender markers could heighten relationality.

Nevertheless, this broader attunement to a universal sense of alterity remains dubious today. It aligns too closely with modern humanism, which permitted the perpetuation of violent acts in the name of moral reforms that would guarantee universal equality based on a shared set of values defined from a Western perspective. Gauging the relationship between difference and sameness without falling into the trap of oversimplification proves difficult, especially in a contemporary climate that has unveiled the mystification of past ideologies which consolidated white privilege. Even scholars supporting the relevance of postidentity debates following the multiculturalism of the 1990s insist that generalizations can obscure significant histories of oppression and falsely suggest that amends are no longer necessary. In pondering such problematics in relation to the distinctions between post-black, post-Chicano, and post-Indian art, Jessica Horton and Chérise Smith argue that “without qualification, postidentity claims can slide into dangerous assertions that America is a post-race nation” (

Horton and Smith 2014).

Paradoxes of postidentity which cannot be easily tackled at the level of discourse can more easily be reconciled in Nick Cave’s body of art which currently features both sculptural objects representative of the post-black agenda such as the

Soundsuits and works based on thrift store items evocative of persistent marks of racism in contemporary societies. His exhibition “Made by Whites for Whites” (2014) at Shainman Gallery featured works such as

Sea Sick and

Property, which served as testimony to the propaganda machine of colonialism and racism enforcing the objectification of black bodies. Slightly reminiscent of Betye Saar’s assemblages, such recent mixed media works take a stab at the persistence of symbols of black servitude in American visual culture.

Hy-Dyve synthesizes these two sides of Cave’s practice at the level of a non-linear narrative which shows that the desire for moving beyond identity categorization can coexist with that for acknowledging specific cultural and social histories which continue to inform one’s identity and experience at present. In “Postmodern Blackness”, bell hooks persuasively argues that we need to distinguish between the tendency to essentialize identities and the focus on commemorating collective narratives shaping black subjectivities. Critiquing the lack of discourse on black experience in postmodern theories, hooks explains that “there is a radical difference between a repudiation of the idea that there is a black “essence” and recognition of the way black identity has been specifically constituted in the experience of exile and struggle” (

Hooks 2015). A similar desire to connect common sensibilities and legacies of oppressed groups with the singularities and multiple dimensions of their members’ intersectional identities stands at the basis of Cave’s non-linear construction of

Hy-Dyve which reunites visual motifs of subjugation with images of resistance through acts of performativity. The installation has been termed one of the artist’s “most personal videos”, as well as one of his more explicitly political works due to its overt references to surveillance (

Markonish 2017). Indeed, this is one of the rare cases in which Nick Cave partly makes his face shown in his work. Except for a series of photographs from 2006 in which he is donning a textile assemblage made out of found materials, he almost always appears in his works in suits that conceal his face. This turn towards becoming (un)masked, signals a shift from a visual rhetoric more closely associated with post-black discourse.

Hy-Dyve suggests that identity construction embraces multiple forms, including a kaleidoscopic rearrangement of pre-existing components which morph into new configurations and a more radical performative queering of selfhood. The former can be observed in the installation at the level of the collage of video projections on the church walls, and the latter is evident in the energetic dance of Cave’s

Soundsuit. As Chérise Smith eloquently argues, “identity is lived and experienced between the “real”, the “fiction”, and the performance” (

Smith 2011). Given its virtual immersion of viewers in a narrative space of colonial and postcolonial dislocation,

Hy-Dyve brings into visibility this fraught relationship with identity formation and ongoing transformation. Integrated in the church, the installation presents an augmented reality by merging dilapidating architectural features with images of performative transgressions of identity markers. Thus, it enraptures the imagination but does not obliterate the difficulties of self-definition. Cave’s

Hy-Dyve blatantly exposes the contingent quality of selfhood. It highlights the fluctuations of identity in relation to a complex set of personal, historical, and socio-cultural variables which influence the degree to which individuals feel liberated (or not) to unmask themselves. While observing a plurality of gazes of one eye visible behind a mask and watching the shifting shape of the dancing soundsuit, viewers gain insight into the intricacies of conceptualizing black subjectivities. In what follows, I will delineate how the ambivalent meanings of visual motifs in the installation undermine fixed interpretations and play havoc with definitions of identity based on binary oppositions.

2. Narratives of Entrapment

Hy-Dyve is structured around six video vignettes which may appear quite disparate until viewers become fully attuned to their jarring interconnections at the level of, more or less, easily recognizable symbols of captivity. The immersive qualities of the video projections shimmering across spectators’ bodies and permeating the church niches make up for the initial discontinuities in the video narrative. They are further amplified by the floor images of cascading water on which visitors tread hesitantly. Far from constructing a linear story, the vignettes convey contrasting emotions ranging from apprehension and panic to exhilaration and quietude. Notably, Hy-Dyve does not offer a totalizing experience which might diminish one’s ability to ponder its critical message about racial profiling. It actively engages viewers in meaning construction, encouraging them to consider how what they already know about the history of slavery and racial discrimination relates to somewhat mystifying visual projections portraying performative acts of masking, dancing, and running.

The video scenes include an image of a rooster mask, a close-up view of the artist’s eye peering out of the mask, a black figurine struggling to break free from an enclosure, a dancing soundsuit, an abstract red and yellow shape floating upwards, and a cartoonish character running at increasing speed. (

Figure 2) Once completed, this sequence of wall projections momentarily comes to a halt while video images continue to flood the floor, illuminating cracks in its surface and making viewers experience a heightened sense of collective presence. As they metaphorically walk across tempestuous waters, visitors find themselves unmasked, made visible to others while partaking in acts of questioning their positionality in relation to the fragmented narratives proposed by Cave. Though the environment continues to feel pervasively immersive, especially since visitors become more acutely aware of proprioception while contemplating the images of gushing water beneath their feet, the construction of the installation becomes more sharply evident. The medium and the message do not coincide as Oliver Grau suggests it happens in the context of immersive artworks (

Grau 2003). One becomes better conscious of the illusion of projection mapping while contemplating the now blank walls of the church showing even more signs of disrepair. Nonetheless, one continues to feel engulfed in the work, struggling to maintain balance in the face of this overwhelming deluge. The sound of water further amplifies the intensity of this absorbing experience and renders visitors even more alert to the difficulty of sidestepping natural and social forces that are beyond their individual control. Hereby, the state of immersion becomes a metaphor for contingency and interconnectivity.

The first video vignette depicts a rooster mask exuding pride. At first, the animal figure appears more as an animate being than an object used for disguise. Shown in profile with its strong beak, wide-open eye, and flamboyant crest, the rooster gazes down on the visitors in an act expressive of defiance or authority. It is initially part of a whole series of images of the same size that populate the church walls, making one feel watched from all sides. The domineering presence of these unflinching rooster heads is shortly counterposed to the abrupt collapse of other identical heads shown at smaller scale. Their fall inevitably makes one think of a violent act of decapitation even though they all calmly find their place in a cohesive multilayered formation. Exploring the literary references called forth by the rooster mask in the MASS MoCA iteration of

Hy-Dyve, James H. Sanders III suggests that it alludes to the lyrics of folk tunes such as “killing the old red rooster when she comes” or stories such as “Henny Penny” (

Sanders 2018). In the church context, though, I find that this collapse of rooster heads triggers closer associations with narratives of martyrdom, demonstrating the stoicism of individuals willing to suffer persecution or even be condemned to death for their beliefs. More generally, the mask could be read as a symbol of masculinity and its fall could be interpreted as an act of questioning the heteronormative expectations associated with it. As with other visual motifs in the installation, the rooster constitutes a multivalent sign.

The next series of images takes viewers closer to the rooster head, suggesting that it is an embodied object turned subject: a mask concealing the face of its wearer. At least this is what one is led to infer upon encountering a close-up of the rooster eye opening which frames the peering gaze of a human. Multiple images of just one eye at various scales are projected into the church niches. (

Figure 3) The eye’s subtle movements have a forceful impact, captivating one’s attention without allowing a complete decoding of the meaning of the gaze. In some images, the eye blinks softly, in others it is wide open, or it cautiously glances sideways, as if wary of an impending threat. Liviu Pasare, the designer of projection mapping for Cave’s installation, explains that he took advantage of the tripartite elevation of the church to project multiple video timelines concomitantly (

Albu 2022). The temporal and spatial variations resulting from this distribution of the imagery enhanced the plurality of the projections without diminishing the overall immersive effect of the installation.

This visual field composed of eye close-ups corresponds to what Gilles Deleuze calls the “affection-image”, an image taken at close range that builds on the tension between an “immobile unity” and the potential for micro-movements across its surface (

Deleuze [1983] 2013). In more concrete terms, the philosopher associates it with the isolated image of a face on which one can observe subtle yet notable changes. Deleuze further distinguishes between a “reflecting face”, which is static and betrays absorption in thought, and an “intensive” face, which is more reactive, expressing minute affective changes and evading association with a specific attribute. In the absence of a full view of Cave’s face, the “intensive face” is more evident in the close-up images of the eye, especially as one notes the contraction and dilation of the pupil or the shift of the gaze sideways. The artist is clearly intent on impeding any presumed understanding of the identity of the seeing subject, or, more precisely, any arbitrary projection of thoughts a viewer might ascribe to the figure in disguise. Instead, Cave invites attunement at a more visceral level by channeling visitors’ attention to micro-movements of the pupil and the eyelid. Since the mask lacks the plasticity of the skin, the tension between the fixity of its surface and the moving eye is intense.

In view of numerous instances in which the emotions and intentions of black people have been misread, Cave impedes any attempt at imposing a narrow reading of the feelings or thoughts of the figure under the mask. Viewers gradually realize that they are surrounded by a multitude of expressive images of an eye captured at different moments in time rather than by merely pictures of it rendered at different scales. In an eloquent analysis of the limitations of a universal theory of affect in relation to black experience, Tyrone S. Palmer points out that emotional nuances are extensively overlooked in interpersonal relations with African-Americans when read from a white perspective. He argues that “Black affect” is perceived “as always already excessive, inadequate or both” (

Palmer 2017). While Palmer agrees that one way of resisting misinterpretations of black expression may be embracing opacity, as Édouard Glissant suggested (

Glissant [1990] 1997), he warns that such an act may actually provide further grounds for justifying racial abuse in the name of an inability of white subjects to recognize or decode affective cues.

5 This tension between legibility and illegibility can be vividly sensed in Cave’s eye vignettes. Seeing just one eye of the masked figure, viewers experience a sense of an endlessly forestalled encounter. The plurality of eye movements observable across the video mosaic conveys an overwhelming feeling of anticipation. Different gradations of fear become apparent: from vigilance to nervous assessment of sources of danger, or utter terror in front of an unavoidable attack.

Despite the nuanced expressions and the ubiquity of the watchful gazes evident in

Hy-Dyve, viewers have little doubt that the figure under the mask is being pursued. The images bring to mind Cave’s statements on feeling vulnerable upon stepping outside the safe confines of his private space: “the moment that I walk out of my home, I can be profiled, and I am looked at very differently” (

Gleisner 2017). As a queer black man, he is aware of the multiple nuances of discriminatory behavior. Although he references his own subjection to judgmental scrutiny, Cave may resist too close of an association of these images with his personal experience even though he is the one behind the mask. After all, he has repeatedly affirmed that he wants to serve the role of “messenger” between people (

Bolton et al. 2014). In an interview with Bill T. Jones, he declared: “My work is not about me. I have to remove myself and then produce the work […].” (

Jones 2016). This may be one of the reasons for which Cave hesitates to make himself fully visible. In

Hy-Dyve, the unmasking is never complete. It is a process of baring parts of oneself that could more viscerally speak to the experience of others similarly exposed to profiling. The image of one and the same eye singularizes the experience of being pursued, yet its multiplication and dispersal across the church walls evoke a plurality of menacing scenarios and emotional reactions. As Deleuze astutely points out, “The close-up does not divide one individual, any more than it reunites two: it suspends individuation. Then the single and ravaged face unites a part of one to a part of the other.” (

Deleuze [1983] 2013). To be sure, the anxious eye in the video projections resists an individuating gaze. The lack of symmetry between the eye images, along with the movement of the pupil in different directions, additionally interferes with fixed subject/object binaries that inform identity categorization. Viewers’ gazes end up floating across the intensive images, never returned, yet seemingly intuited by the masked figure who appears to be pursued from all sides.

The following video vignette in

Hy-Dyve takes viewers literally and figuratively to the heart of the matter: the tension between the desire to drop the mask and the urge to seek protection when one is faced with objectification and racial profiling. Spectators are offered an even more proximate view of the mask eye hole, yet this time its aperture frames a moving figurine instead of a wary eye. The object is not easily identifiable, neither is the mask hole since it is shown from an oblique vantage point that makes it appear abysmal. The object turns out to be a black servant figurine once it emerges triumphantly from the aperture after a frantic series of twists and turns. Its escape provides some degree of comical relief from the somber mood of the mask scene. The fidgeting motion of the figurine contrasts sharply with the subtle movement of the masked eye. Despite these differences, both scenes convey the anxiety of entrapment. The figurine embodies a stereotypical representation of a docile black servant ready to fulfill his master’s desires while donning a smile. But in this vignette, it appears as a disruptive force, a resilient individual finding his way out of the tightest confinement. Over the last decade, Cave has integrated such collectible items from the Jim Crow era in his works, re-inscribing them with meaning and keeping them in the public eye as undeniable evidence of the desire to reduce difference to sameness (

Markonish 2017). In

Hy-Dyve, the figurine stands for an unavoidable irritant of all acts of seeing and defining black identities. It is hardly accidental that the eye aperture in the rooster mask also resembles a gaping wound, especially in relation to the agitated motion of the trapped object. The vignette offers insight into a black subject’s entrapment in a body carrying vestiges of past misjudgments which have impacted his self-perception. It also discloses his current entrapment in a visual culture that perpetuates biased views. The subject is thus trapped on the inside and the outside, having to shrug off both self-imposed and assigned masks.

Interestingly, the immersive experience fostered by

Hy-Dyve brings to the surface the enfolding of individuals in surveillance societies, thus subverting a smooth state of absorption in its framework. Due to the plurality of images of one and the same visual motif, viewers are made aware of the framing of representation and the framing of black subjects repeatedly placed under supervision in anticipation of misconduct and even made to appear guilty through the manipulation of evidence. Consequently, viewers experience a sense of displacement which is generally found to be at odds with states of immersion. They may come to question if and how they might be seen in the installation or in society at large. In

Virtual Art, Oliver Grau claims that immersion results from an experience of “unity of time and place” and a lack of awareness of deception (

Grau 2003). Yet, in this instance, the environment plays havoc with such blinding absorption, making one sensitive to the framing of one’s presence within and beyond the confines of the installation. More recent theorizations of immersion have shown that critical distance does not preclude immersion. While Grau does not actually argue that the two are mutually exclusive, he suggests that the possibility for reflection on one’s experience diminishes when one is engaged in an immersive state. His rationale for this is the result of thinking of immersion primarily in terms of emotional intensity and neglecting the fact that action and cognition can be equally absorbing and moving. Katja Kwastek proposes that we shift focus from an understanding of immersion in terms of “mental or sensual illusion” to a discussion of it in relation to both “emotional and cognitive intensity” (

Kwastek 2016). She applies this idea to interactive artworks by looking at their reception through the lens of the concept of flow which defines an absorbing experience that can be triggered both by sensory engagement and by the performance of acts meant to complete the content of an artwork.

Although Hy-Dyve does not call upon viewers to become literal co-producers of the work through their creative feedback, it fosters an absorbing mode of participation by inviting them to explore meaningful connections between the video vignettes. Oscillations between various interpretive possibilities accompany the vivid sensations the installation provokes, equally contributing to its immersive impact as visitors attempt to identify some degree of narrative congruence between the video scenes. This is particularly the case with the vignettes including more easily identifiable figurative elements. The process of meaning-making becomes more unstable when witnessing the vignettes that veer towards abstraction. In this instance, absorption emerges more strongly from sensory stimulation. This pivoting between varying sources of intensity does not detract from the immersive experience. On the contrary, it maintains its hold and shows that our attention can be stretched and heightened through sharp shifts in the object of visual focus.

3. The Spatialization of the Body

In the two video vignettes following the one depicting the trapped figurine, the projected images no longer match the borders of the architectural structure neatly. More abstract in character, they extend across the boundaries of niches and arches, turning the church walls into a screen with diminished material presence. This shift in projection mapping interestingly corresponds to a change in visual content and perspective. While the prior scenes offered viewers an increasingly close vantage point, these vignettes convey more distant views and have a more impersonal character. In the absence of almost all figurative cues, the identification of what one sees becomes challenging. Moving rhythms and color patterns take front stage in a mesmerizing choreography which evokes ongoing transformations of matter. For those familiar with Cave’s Soundsuits, the images are bound to conjure memories of effervescent dance performances and eclectic outfits. For others, they may appear as computer animations due to their tempo and the geometric patterns they encompass.

The tempo of the first vignette in this more abstract set of imagery is fast. An explosion of yellow and red fibers moving rhythmically takes viewers by surprise. (

Figure 4) The atmosphere they create is so electrifying that one may fail to notice that the black figurine makes another appearance. Its gloved hands emerge from the vibrating fibers and seem to support an invisible ceiling. The frantic dance of quasi-unidentifiable matter ends in a dazzling outburst of light. The blinding sensation echoes the prior obfuscation of vision evoked by the entrapment of the figurine in the mask eyehole. Sensations take precedence over reflection in this intense moment of

Hy-Dyve which brings to mind Deleuze and Guattari’s ponderings over affect and artmaking as instantiations of “nonhuman becoming.” In their view, affect “is a zone of indetermination, of indiscernibility, as if things, beasts, and persons […] endlessly reach that point that immediately precedes their differentiation” (

Deleuze and Guattari 1991). Cave places viewers precisely in such a liminal zone where the interpretation of the work strictly in terms of race is temporarily suspended. This video segment deepens disorientation both in sensorial and conceptual terms. At this level, the work moves beyond a strictly racial reading, interfering with attempts at differentiation based on identity categories.

Through its disorienting visual effects,

Hy-Dyve parallels David Hammons’s

Concerto in Black and Blue (2002), a dark environment through which participants navigated with flashlights of narrow frequency. Responses to Hammons’s installation, which focused merely on its correlations with racialized space in the U.S., served as the main premise for Darby English’s eloquent critique of the tendency to “limit the significance of works assignable to black artists to what can be illuminated by reference to a work’s purportedly racial character” (

English 2007).

Hy-Dyve similarly encompasses allusions to acts of identification and recognition that surpass racial categorization.

The fast-swaying strands which eventually transform into a field of throbbing light trigger a transgressive experience. Cave asks viewers to envision what it might feel like to experience the world through a different body which lacks human shape. The experience is defamiliarizing even for viewers who recognize the reference to moving textures characteristic of Cave’s

Soundsuit performances. The abstract patterns which emerge as the colorful strands jump and swing are entrancing, especially since they offer no specific cues to the source of their vitality. They seem to be imbued with a mysterious life force which eludes bodily constraints. Through the brightness of the colors and the shifting geometric patterns, this vignette resembles the aesthetics of a visionary experience. The luminosity of the images and the absence of easily recognizable symbols add to this impression, along with the aerial perspective upon a seemingly shape-shifting body hidden beneath the bouncing strands. Aldous Huxley suggests that visionary images connect us to the collective subconscious and momentarily permit us to surpass a self-centered view upon reality. According to him, art can open a gateway to such a transporting experience which connects us to “the Other World’s essential alienness and unaccountability” (

Huxley [1954] 2009). It is in this remote yet not entirely inaccessible layer of consciousness that Cave hopes viewers can overcome the urge to label what they perceive and define others solely based on identity markers.

By Cave’s own admission, his

Soundsuits are puzzling because they prompt questions of identification yet impede any clear-cut answer. In an interview, he states: “You’re trying to find that link to something familiar. And yet, it’s familiar from the perspective that it’s figurative, and then that becomes where the difficulty falls in—because there’s a sort of humanness to it, but yet it’s not of this world.” (

Sharp 2015). In

Hy-Dyve, Cave takes this otherworldly quality one step further by extending the moving texture of his

Soundsuits to the surface of the entire church. In their overview of projection mapping, Daniel Schmitt, Marine Thébault, and Ludovic Burczykowski claim that this technique implies a “spatialization of the gaze” (

Schmitt et al. 2020). Comparing it to cinematic projection, they point out that it is less likely to trigger processes of identification. Instead, it involves the dispersion of the gaze, which is no longer expected to be frontally aligned with the screen, and the mobilization of the viewers who are no longer confined to a seating area. In the soundsuit vignette, the church walls appear to pulsate to the rhythm of the bright strands which camouflage traces of humanity. Architecture frameworks and soundsuit images converge in this absorbing scene. Cave metaphorically portrays an act of queering of identity through the spatialization of body movement images which start by being associated with a dancing human figure yet eventually dissolve into a field of colorful strands that engulfs the church walls in its luminous vibrations. It is as if the outlines of the dancer in the soundsuit become infinitely malleable and expendable. Figure and ground become one, composing a vibrating and luminous space which contrasts with the gridded patterns of images observable in the preceding video scenes. This collapse of corporeal boundaries evokes the transgression of fixed signifiers of identity and the fluid mutation of selfhood. The vignette impedes identification, provoking instead a more visceral relation to the quivering body potentially inhabiting the mélange of colorful fibers.

This shift towards suppressing references to recognizable human shapes complicates Cave’s earlier take on the

Soundsuits. It may be read as his response to the failure of the universalist humanist project of the Enlightenment which served as an ideological platform for establishing different degrees of belonging to humanity based on racial differences. In

Becoming Human, Zakiyyah Iman Jackson shows that both human and animal categories were redefined in relation to notions of abjection developed in the context of colonialism. She adroitly asks: “If being recognized as human offers no reprieve from ontologizing dominance and violence, then what might we gain from the rupture of the ‘human?’” (

Jackson 2020). Cave’s

Hy-Dyve invites us to experience this very rupturing of the human, understood in Western terms as the opposite of the animal, the embodiment of rationality, and the presumed upholder of an ethical stance which would prohibit acts of violence against other fellow humans.

The transformation of the soundsuit into a vibrating field of fibers highlights the affective and material bond we share, as well as our entanglement in a mutating array of relations which surpass boundaries between animal, plant, and human bodies. The yellow and orange hues of the fibers encourage viewers to recollect the rooster head mask seen in the first vignette. The visual episodes proposed by Cave connect in subtle ways, not through narrative lines, but through colors and rhythms which allude to affective ties and the performativity of identity. Resisting categorizations based on skin color or physiognomy, Cave asks us to see the body as a lively, mutating environment constantly undergoing processes of differentiation and attunement in relation to various psychic and social rhythms.

The next set of moving images also impedes attempts at identification of figurative elements but unfolds at a completely different pace. Shapes that resemble cocoons or sky lanterns slowly float upwards in parallel rows. They encapsulate the same colors as the dynamic moving strands. This color connection makes one see them as compact versions of the exuberant being celebrating difference in the prior scene. They appear to be infused with some sort of dormant energy that can burst back to the surface at any moment. The steady movement of the shapes up and down the walls evokes the flow of people engaged in migratory processes, a sign of the constantly evolving diasporic space. This quiet moment in the unfolding of the projections offers viewers some respite before the encounter with the final vignette of Hy-Dyve, which confronts them with yet another tense experience.

4. The Burden of History

The black figurine makes its appearance again, this time in the guise of an animation character. The projections now appear only on the lower portion of the church walls. The figure first seems to be marching at a steady step. He is part of a whole row of identical individuals, mechanically moving in unison. Gradually, their pace accelerates, and they appear to run faster and faster, up to the point where their features turn into black and white patches. Conflicting interpretations arise: the running figures could be seen as docile servants performing their duties at a faster and faster pace or as individuals desperately seeking liberation from the conditions of servitude. Either way, the feeling of entrapment prevails over that of freedom because the figures run on the spot. It becomes increasingly harder to watch these endlessly running figures who embody the struggle of so many generations of African-Americans.

The running figure in

Hy-Dyve conveys the urgent need to take a stance against racism. Cave made it clear that he created the works in “Until”, the exhibition that

Hy-Dyve was originally part of, under the impact of wrongful police shootings between 2014 and 2017: “As I was developing this project, the Michael Brown incident happened in Ferguson, Missouri; Freddie Gray went down, and then Eric Garner, Sandra Bland, and Christian Taylor.” (

Gleisner 2017). He also explicitly affirmed that

Hy-Dyve is about “feeling trapped” and time “running out” (

Loos 2016). The running figure does not merely represent the Jim Crow era. In conjunction with the other vignettes, it brings to mind images of the victims of police pursuits that end in unwarranted violence due to racial profiling.

The encounter with the images of flight is suspended quite abruptly. The break in the flow of wall video projections increases the affective momentum. In this brief interlude, the experience of restlessness is prolonged. It is as if the pictures of the running figure have turned into phantom images that continue to haunt viewers while they endeavor to make sense of the connections between the vignettes. Visitors are left wandering, and wondering, in the midst of the floor images of tumultuous waters. The powerful stream of water bespeaks ambivalent associations. It could be read as a sign of the Middle Passage in view of subsequent images pointing to the struggles of African Americans, or a more contemporary reference to devastating floods affecting impoverished communities. Either way, it connotes tempestuous forces undermining human control. Cave has had an ongoing interest in challenging anthropocentrism, an ideology which is tightly connected to the rampant exploitation of both environmental resources and indigenous populations in the name of the presumed superiority of Western cultural values. In conjunction with “Meet Me at the Center of the Earth”, a 2009 exhibition which focused on his use of animal imagery, Cave stated: “Animals have so much to teach us. […] We are destroying the earth and continue to be naïve about it. We have to find ways to live with each other, extend our compassion to other communities, and take care of our natural resources.” (

Cave and Eilertsen 2009).

Hy-Dyve reflects Cave’s desire to inspire communion. It creates a sense of belonging to an affective community menaced by, more or less, visible threats. In this interlude, visitors become more self-aware, as well as more vividly conscious of the presence of others sharing the installation space. At the time of my visit, I could not help but notice how a group of high-school students had gathered in a circle on the floor while another group had found refuge on the stairs leading to the altar. (

Figure 5) As the images of water continued to flood the floor and the walls remained barren of projections, the traces of blight became more pronounced. The cracks in the wall looked wider and the vestiges of paintings which once adorned the space became more visible. The Gloria medallion at the top of the altar canopy also stood out better. Nonetheless, there was no resurrection of hope in sight, especially as one continued to be disoriented while treading on the images of gushing water. The vastness of the church devoid of pews accentuated the feeling of displacement. The niches became more haunting, functioning as screens for one’s imagination. Such a disorienting and ambivalent experience can hardly be replicated in a museum environment devoid of high ceilings or historical traces. The abysmal quality of the church space took one closer to the Middle Passage and the disorientation slaves experienced when they were uprooted from their homelands. Emptiness is the mark both of the psychic space of the dispossessed and of the territories across which they travelled. In

The Open Boat, Glissant speaks of multiple dimensions of abysmal depth. He conjures up poetic images of the emptiness of the “belly of the boat” in which slave bodies were crammed, the chasm of the ocean depth, and the abyss of “the nonworld” to which those who survived the horrendous journey arrived (

Glissant [1990] 1997).

Cave’s

Hy-Dyve metaphorically places viewers in a vast space that evokes the experience of deterritorialization and carries the heavy imprint of contemporary blight due to the signs of neglect it conspicuously displays. Yet not everything is lost since there is a sense of intimacy, of desired or actual mutual understanding of those co-present in the church who are ultimately participating in an act of commemoration; not only of the victims of police brutality of recent years, but also of the numerous slaves who died at sea. As Glissant masterfully proposes, what is gained is “knowledge of Relation within the Whole” (

Glissant [1990] 1997). This is also Cave’s desideratum as he likes his presence to fade into the background to allow audience or community members to reclaim the space of his works.

5. The Charged Site

Cave is especially sensitive to the social histories of the sites in which his works are inscribed. This aspect is most prominent in his collaborations with communities staging

Soundsuit performances but is also increasingly apparent in relation to the adaptation of his installations to different display settings.

6 The floor projections in

Hy-Dyve are usually filmed anew for each installation iteration so that they capture images of water representative of the location where the work is shown. Other differences are also apparent. In the Kansas City iteration of

Hy-Dyve, the starkly illuminated lifeguard chair is positioned near the altar rather than in the middle of the installation, as in the case of its initial display at MASS MoCA. Thus, the chair’s association with a vacant seat of judgment becomes more conspicuous, asking viewers to ponder both who gets to occupy the position of authority and what happens in the complete absence of a moral compass.

The church installation of Hy-Dyve included additional transformations, which were subtle yet notable. At MASS MoCA, the lifeguard chair was anchored by lateral benches which permitted visitors to adopt a more contemplative perspective and find some degree of refuge from the perceptually destabilizing effects of the images projecting across their bodies and under their feet. Beneath the chair seat, Cave also placed a transparent box containing the yellow and red soundsuit which makes an appearance in the video vignettes. This component was not present in the Kansas City installation, possibly because it may have constituted too much of an object of veneration when placed in the proximity of the altar.

In Kansas City,

Hy-Dyve spoke to past and present oppression in a powerful manner. It represented even more of an emotionally charged site because the deconsecrated church in which it was located belongs to the Hope Center, a nonprofit organization which offers programs for disadvantaged youth.

7 In such a setting, the installation launched a poignant demand for practicing neighborly love. Cave’s display choice was even more compelling since the venue is located on the east side of Kansas City, an impoverished urban area presently facing housing problems and high unemployment rates. It is a charged site given its history of inequities and interracial tension. Born in Columbia, MO, Nick Cave studied at the Kansas City Art Institute and is no stranger to the segregation policies that have shaped the physical and demographic geography of this city.

The Annunciation Church where

Hy-Dyve was displayed was completed in 1924 at the intersection of Benton and Linwood Boulevard. The catholic parish to which the church belonged had moved from the inner-city area where the stockyards and railway systems were rapidly expanding (

Hornbeck 2008). The Gothic Revival architecture of the church is imposing even today despite the fact that the steeples meant to cover the square towers flanking the church façade were never completed. Its interior is also impressive given the very wide, barrel-vaulted nave. The Linwood neighborhood near which the Annunciation Church is located witnessed major transformations in the 1950s when numerous white families started to move out at the first signs that black families were assuming residency there. For several decades before this, the Linwood Improvement Association had strived to impose racial boundaries, placing racist signs in public spaces and even organizing rallies to protest the presence of black people in this area. While initially real estate companies supported these campaigns, they eventually decided to encourage blockbusting to maintain their financial profit in the area. In response to this, Earl T. Sturgess, a pastor in the Southeast Presbyterian Church found just a couple of blocks away from the Annunciation Church, established a coalition in the 1950s to put a stop to the flight of white families from this area (

Gotham 2014). He urged residents in this area to refuse to sell their properties to black people. His movement did not succeed, and the east side of Kansas City went through significant demographic changes. As sociologist Ken Fox Gotham rightfully notes, these changes in population deepened not only racial conflicts but also social inequities due to the imposition of restrictions on the loans taken by residents of this neighborhood.

Displayed in the vicinity of Linwood, Cave’s

Hy-Dyve installation acquired additional meaningfulness by temporarily occupying a terrain which has a long history of racial tension and still carries some of the marks of division. The sacred space of churches in Linwood offered no refuge from racial conflicts, especially since certain church leaders took an active part in vigilant coalitions in the neighborhood. The former Annunciation Church is currently in an increasingly deteriorating state and appears on the list of the most endangered historic buildings in Kansas City.

8 Reminiscing the installation process, designer Liviu Pasare pointed out that he had to use ladders instead of forklifts for placing the video projectors because of the increasingly frail building structure (

Albu 2022). Permeating all the corners of its empty space, Cave’s

Hy-Dyve highlighted dire signs of disrepair. At times, the video projections illuminated fissures in the walls and scant remnants of canvas paintings attached to the walls.

9 Since the stained-glass windows, originally made in Austria, were removed, the only sign of the sumptuous church past was the high baldacchino composed of richly colored marble. While contemplating images of slavery and racial profiling in the church setting, one cannot help but question why religious values have failed to prevent abominable acts of cruelty against black people. As someone who embraces spirituality but does not make public statements on his religion, Cave plunges visitors of the deconsecrated church into a sensuous space that elicits togetherness and bridges the presumed gap between poetics and politics.

Hy-Dyve inspires activist advocacy for the local community without proclaiming a specific course of action. It ties in with Christian religious values such as love for one’s neighbor without preaching. Instead, it places viewers, be they insiders or outsiders of east Kansas City, in an affective environment that permits them to envision what it might feel like to be torn between a desire to make one’s differences visible and a need for self-protection.

6. Upstaging Identification

Bearing affinities both with his well-known Soundsuits and his more recent sculptures incorporating racist memorabilia, Hy-Dyve acts as a connector between these two facets of Cave’s practice: an earlier stance according to which all differences are fluid and a more recent activist commitment to singling out the difficulties of the black experience across multiple generations. Coming to terms with differences ultimately calls for acknowledging their specificity and concomitantly accepting their susceptibility to change. Cave’s installation forcefully conveys this idea by emphasizing the contingency of processes of self-definition which may accentuate or erode differences depending on the spatial and historical frameworks against which they unfold.

Hy-Dyve situates spectators in a liminal space between visibility and invisibility. Through transitions between light and darkness, effervescence and entrapment, the video vignettes convey a fluid process of definition of black subjectivities which transgresses binary oppositions but continues to carry the imprint of burdensome histories of domination. The chair looming at the center of the former altar signals that power relations are unavoidable, and all individuals are ultimately imbricated in their entangled threads. Its emptiness undermines facile good/bad polarities and suggests that we can all bear witness to each other’s acts and resist the congealing of differences into fixed categories. Cave’s decision to unveil his eye in Hy-Dyve is not merely an allusion to the statement that “the personal is political”, but is a hint at the fact that we need to watch out for one another in times when trust in institutions in the United States is weakened. Fully masking one’s face and body limits an openness to others. Cave’s exposure of his gaze may thus come as an admission that staying disguised is not always a viable option because there are times when one needs to assume the risk of being seen in order to stand up for others.

In the 2000s, Cave’s Soundsuits could easily be integrated into a post-identity framework given their association with performative acts of becoming the Other that elude categorization. Nonetheless, they are far from rendering racial differences irrelevant. In Hy-Dyve, the presence of the soundsuit is more closely associated with the experience of inhabiting a black body because of its juxtaposition to symbols of slavery. Yet its signification is not restricted to this dimension since it speaks of performing differences that elude legibility and impede identification in terms of binary oppositions.

Hy-Dyve reflects the mistrust and interracial anxieties persisting in American society in the new millennium. Despite its dark undertones related to surveillance and racial profiling, the installation also delivers a hopeful message about the recognition of the complex dynamics of identity formation which move us past oppositional modes of self-definition. Art historian Amelia Jones persuasively speaks of the way in which artists enable us to “see differently” by maintaining “the

durational aspects of how we identify in the foreground” (

Jones 2012). This is exactly what Cave accomplishes in

Hy-Dyve by using visual tropes with slippery meaning. He asks us to pause, pay attention, and relate affectively to the experience of being trapped, locked in an exchange of gazes that does not allow for fluid differentiation. To this rhetoric of the gaze, Cave counterposes communication through bodily movement which appears more liberating because it can sensitize viewers to the experience of otherness in a more immediate manner, thus upstaging the ascription of identity categories. This being said, the powerful bodily sensations fostered by

Hy-Dyve do not hinder intricate acts of meaning making. Cave challenges viewers to question their position in relation to ambivalent visual motifs and imagine narrative lines which extend beyond the scope of the artwork.

Whether envisioned as the interior of a slave ship navigating across stormy waters (

Lakin 2018), a visual metaphor for the tormented psychic space of African-American experience, or more broadly, the turbulent environment of contemporary societies where the acknowledgment of differences at the level of discourse does not bring about actual social change,

Hy-Dyve speaks to past and present divides, visible and invisible constraints, anxieties and desires associated with processes of identification. Tension persists in the absorbing space of the installation. Sensory immersion in

Hy-Dyve does not preclude reflection on the conundrums of identification or the dire consequences of racial profiling. The video projections are both gripping and disquieting, repeatedly prompting viewers to question what they see and how they assign meaning to images. By confronting viewers with visual tropes with ambivalent meaning, Cave enables them to inhabit a space of indetermination where judgments are forestalled and identity attributes restlessly mutate at different rhythms just as the kaleidoscopic symbols that form new arrangements on the church walls. He does not relinquish installation visitors from responsibility but compels them to take a stance, find meaningful ways to connect the video vignettes, and make sense of the deeply interconnected threads of past and present abuses of power.