Abstract

This article discusses the cannibalistic imagery in Meret Oppenheim’s works. The crucial aspect is the comparison of two versions of a seemingly similar event in which anthropophagic motifs were significantly present—Spring Banquet and Cannibal Banquet. Often mistaken or wrongly attributed, these events were essentially non-identical and evoked contrasting meanings. The comparison of Spring Banquet and Cannibal Banquet proves that they represent contradictory aspects of anthropophagic imagery. The primary research question is whether Oppenheim’s use of cannibalistic motifs differs from the manner in which they are utilized by male surrealists. Therefore, cannibalistic imagery in the works of Oppenheim is described in the context of avant-garde preoccupation with gendered anthropophagy in which a woman is imagined as an object of consumption. This article concludes with an argument that Oppenheim attempted to subvert the prevailing meanings of cannibalism in surrealism. This article also discusses Oppenheim’s other artworks with anthropophagic connotations, including Ma gouvernante—My Nurse—mein Kindermädchen (1936) and the less-known Bon appétit, Marcel! (The White Queen, 1966).

1. Introduction

Meret Oppenheim remains one of the most renowned figures of the surrealist movement. However, her position within the group was ambiguous, and throughout her career, she repeatedly distanced herself from surrealism (Baur 2022, p. 49; Zimmer 2021, pp. 21–22; Meyer-Thoss 2013, p. 293; Blau 1997, p. 40). Her recognition was also often limited to her famous fur-covered teacup, Object1 (Déjeuner en fourrure), which was presented in the year 1936 at Galerie Charles Ratton in Paris during the exhibition devoted to the “Surrealist Object”. This work became an icon of the surrealist movement and was acquired in the same year by Alfred Barr Jr. for the collection of the Museum of Modern Art in New York. However, apart from Object, which is her only work mentioned or displayed with any frequency in books or exhibits on Surrealism (Suleiman 1990, p. 212), her less-known works deserve more careful critical attention.

Meret Oppenheim’s oeuvre is diverse, heterogeneous and multifaceted, and it escapes any stylistic frames or categorizations (Curiger 1989; Baur 2022; Eipeldauer et al. 2013). Despite her apparent popularity, Oppenheim’s oeuvre has remained overlooked; however, recent tendencies prove that her works are being rediscovered, with major retrospectives (Eipeldauer et al. 2013) or the recent exhibition at The Museum of Modern Art in New York2. The following article is focused on the interpretation of cannibalistic imagery and its various meanings in her works. There has been a visible increase in research on cannibalism also in the context of anthropophagic imagery presented in visual arts3, film and literature (Brown 2013; Champion 2021; Guest 2001; Githire 2014; Pouzet-Duzer 2013). Cannibalism itself is a complex cultural phenomenon and a powerful metaphor; hence, it is crucial to indicate that its implications vary depending on the context (see Guest 2001; Champion 2021; Avramescu 2009; Nyamnjoh 2018; Kilgour 1990).

This article compares two versions of a seemingly similar event in which anthropophagic4 imagery was significantly present—Spring Banquet (Le Festin/Festin de Printemps) and Cannibal Banquet (Dinner Cannibale). The first was staged at a private event in Bern in April 1959, and the latter was staged during the Exposition inteRnatiOnale du Surréalisme (EROS), which took place from 15 December 1959 to February 1960 at the Galerie Daniel Cordier in Paris. This article concentrates on examining the anthropophagic motifs in Meret Oppenheim’s works from a gendered perspective.

This article’s main thesis is that, despite their apparent similarity, those events expressed various ideas and differed in their principles. Changes in the second version of the banquet were immensely significant, and evident alterations deeply affected the meaning of Oppenheim’s action. The two banquets are often mentioned (Baur 2022; Eipeldauer 2013; Curiger 1989); however, they are rarely compared. One of the most extensive comparisons was presented by Peter Gorsen in his article, “Meret Oppenheim’s Banquet—A Theory of Androgyne Creativity” (Gorsen 1997), in which he places Spring Banquet in the context of a matriarchal cult and describes the ambivalent feelings Oppenheim had toward the second version of the event. Maria Rosa Lehman interpreted Cannibal Banquet in the context of violent voyeurism; the author also pointed out that surrealist exhibitions can be read as early performances, as they exceed the plain presentation of the objects (Lehmann 2014, 2017). One of my key arguments is that, to understand the meaning of Cannibal Banquet fully, it is crucial to place it in the context of the whole EROS exhibition. Surrealist presentations engage various senses and often include performative actions. This feature of EROS was thoroughly described by Steven Harris (Harris 2020) and Annette Michelson (Michelson 1960). This paper concentrates on a particular aspect of Oppenheim’s banquets—its cannibalistic connotations, with a vital argument that cannibalistic motifs can fundamentally differ in their meanings.

In order to analyze Spring Banquet and Cannibal Banquet from an adequate perspective, it is crucial to place those works in a broader context; therefore, this article describes the place of women artists in the surrealist movement and the presence of anthropophagic motifs within it. Cannibalistic imagery and desires have informed avant-garde texts and artworks; however, they represent mainly the male perspective, in which cannibalism is connected with destruction and aggression. Can Oppenheim’s works be read in a feminist context? Does the fact that the cannibalistic ritual was set by a woman change its meaning? Does Oppenheim’s approach toward cannibalistic imagery differ from the male perspective? Besides the two above-mentioned events, Oppenheim’s other artworks with anthropophagic connotations are mentioned, including Ma gouvernante—My Nurse—mein Kindermädchen (1936) and the less well-known Bon appétit, Marcel! (The White Queen, 1966). The critical context for interpreting these artworks is the links between food, eroticism and gender.

2. Surrealism and Women

In order to reflect on the meaning(s) of cannibalistic imagery in Oppenheim’s works, it is essential to expand the issue of the surrealist approach toward women and femininity and how this is reflected in anthropophagic motifs.

As André Breton emphasized in 1929, the “problem of woman is the most marvelous and disturbing problem in all the world” (Chadwick 2021, p. 10). A recurring motif in the scholarly discourse regarding surrealism is the position of women within the movement (see Chadwick 2021; Gauthier 1971; Caws et al. 1993; Caws 1986; Latimer 2016; Billeter and Pierre 1987; Orenstein 1975). It should be noted that both the role of women artists and the representations of the female body in surrealist art are varied and do not fall into one pattern. Women are celebrated or even worshiped, but on the other hand, surrealist imagery is inundated by images of violations of their bodies—they are defragmented, decapitated, caged and tortured (Caws 1986; Kuenzli 1993). Gwen Raaberg emphasized that it was not until 1930 that women became more visible within the movement, as before this, no women had been listed as official members nor had signed manifestos (Raaberg 1993, pp. 1–2). However, even with the increasing presence of women artists, Raaberg observed a reoccurring lack of recognition of their conceptual and creative force.

As a source and object of male desire, women are assigned various roles—as a femme-enfant, muse or embodiment of amour fou—and they are conceived as “man’s mediators with nature and the unconscious”. In each case, “the concept of ‘woman’ objectified by male needs was in direct conflict with individual woman’s subjective need for self-definition and free artistic expression” (Raaberg 1993, pp. 2–3). Rudolf Kuenzli drew attention to the fact that surrealists’ seemingly revolutionary approach to gender masks their latent misogyny and that they reproduce “patriarchy’s misogynistic positioning of women” (Kuenzli 1993, p. 18). Tirza True Latimer affirmed that, even with their fundamental critique of bourgeois values, including the nuclear family and traditional gender roles, they fail to “unsettle prevailing male-female hierarchies, challenge stereotypes of femininity, or question the dominant culture’s misogyny, heteronormativity, and homophobia”. (Latimer 2016, p. 355).

The surrealist relation to femininity cannot be reduced to violent misogyny, and such a one-dimensional approach has been referred to as reductionist (Caws 1986, p. 265) and questioned. For instance, it is worth noting Breton’s words in Arcanum 17, in which he mentioned the need to “bring man down from a position of power which, it has been sufficiently demonstrated, he has misused, restore this power to the hands of woman, dismiss all of man’s pleas so long as woman has not yet succeeded in taking back her fair share of that power, not only in art but in life” (Breton 1994, p. 62). Penelope Rosemont connected the disappearance of women’s contributions to surrealism with the tendency of art critics to overlook their input, rather than surrealist’s reluctance toward them. She also indicated that “despite their very real problems, confusions, and mistakes, the first Surrealist Group was probably the least sexist male-dominated group of its time”. (Rosemont 1998, p. 106).

While acknowledging this diversity, the present article concentrates on the misogynistic aspect of surrealism, as it is a crucial context of the analyzed artworks. There is, in fact, an undeniable persistence of images that “objectify, defile, subjugate, and fetishize the female form (…)” (Latimer 2016, p. 354). Surrealist sadistic eroticism is filled with an obsession with violated femininity, hence the persistence of representations and imagery connected to cannibalism—women’s bodies are dissected, defragmented, objectified and presented on tables or plates. These images can be interpreted as being a result of the above-mentioned misogyny and perhaps even as a desire to erase women’s subjectivity. However, the question here is how to analyze the use of this anthropophagic imagery by a woman surrealist such as Oppenheim.

3. Avant-Garde and Anthropophagy

Anthropophagic imagery permeates avant-garde artworks (see Ades 1998; Novero 2010; Pouzet-Duzer 2013). The reading of cannibalism in which it becomes a metaphor for male desire is not restricted to surrealism but is also a prevalent motif in Italian futurism. The motif of female-oriented cannibalism frequently appears in The Futurist Cookbook, in which women are in constant threat of being eaten and annihilated (Marinetti and Fillia 2014; see also: Novero 2010). Cannibalistic imagery appears in The Futurist Cookbook in various ways—it is present in the narrative itself5, and it is visible in descriptions of the feasts (Extremist Banquet) and served dishes (food sculptures shaped as parts of women’s bodies)6.

Surrealists have employed anthropophagic motifs on numerous occasions, and this study does not attempt to exhaust the topic. Women served on plates, passive and waiting to be eaten, appear in works by Man Ray, René Magritte and Salvador Dali. Ades mentioned that, in the case of surrealism, anthropophagy often aligns with sexuality and desire (Ades 1998, p. 244).

Cannibalistic motifs appear in Dali’s works, such as Autumnal Cannibalism (1936) and Portrait of Gala with Two Lamb Chops in Equilibrium upon Her Shoulder (1933). In the latter, Dali depicts Gala with her eyes closed, with two pieces of meat on her shoulder. The artist commented that this image arose as a result of an unconscious desire:

The meaning of this, as I later learned, was that instead of eating her, I had decided to eat a pair of raw chops instead. The chops were, in effect the expiatory victims of abortive sacrifice—like Abraham’s ram, and William Tell’s apple. Ram and apple, like the sons of Saturn and Jesus Christ on the cross, were raw—this being the prime condition for the cannibalistic sacrifice. (…) My edible, intestinal and digestive representations at this period assumed an increasingly insistent character. I wanted to eat everything, and I planned the building of a large table made entirely of hard-boiled egg so that it could be eaten.(Dalí 1993, pp. 888–89)

Here, cannibalism is a sign of a desire that cannot be fulfilled, gargantuan gluttony in which the subject attempts to devour the whole world. His desire to overtake, control and own everything results in the fantasy of consumption. Dali’s craving to consume Gala was possessive, connected with the urge to immobilize and control her completely. In an act of Freudian sublimation, the desire was displaced so it could be fulfilled in a way that is acceptable by society, so instead of fulfilling the cannibalistic impulse, Dali consumed the lamb. The symbolism of a lamb as well as the mention of Abraham’s ram can inspire a theological interpretation. Robert James Belton mentioned that Dali’s “infatuation with edible women (…) is an inversion of the transubstantiation of the Host, the normal Eucharist being replaced by sexual activity with cannibalistic overtones” (Belton 1995, p. 171).

The anthropophagic desire returns in Dali’s cookbook Les dîners de la Gala, in which the chapter devoted to aphrodisiacs is titled Je mange Gala—linking food, cannibalistic imagery and eroticism (Dalí 2016, pp. 247–69). Analyzing surrealist misogynistic imagery, Kuenzli mentioned the works of Hans Bellmer, in which he “fetishizes the female figure, deforms, disfigures, manipulates her. To dominate, colonize, dissolve obliterate female subjectivity” (Kuenzli 1993, p. 25). In a similar manner, cannibalistic tropes in surrealist art can be read as a violent attempt to erase women’s subjectivity.

Gauthier mentioned a painting by Dali in which he represented his “douce” Gala as a pomegranate among other pomegranates. She connected it with the surrealist motif of la femme-fruit, in which a woman becomes an object to be consumed (Gauthier 1971, p. 115). For Gauthier, consumption is one of the final aspects of the male desire to control and objectify women. In surrealist imagery, women can not only be eaten but also drunk, as in Magritte’s paintings in which women’s bodies are trapped inside bottles, or in Louis Aragon’s poem (with the sentence—(…) Ô mon verre de vin). (Gauthier 1971, pp. 116–17).

It must be stressed that there is also another dimension of cannibalism present in artworks in the surrealist circle, which is connected with the image of the praying mantis. Here, the situation is reversed: the male is consumed by the female. William L. Pressly wrote about surrealist preoccupation with this insect and interpreted it as another dimension of their interest in erotic violence and repressed desires (Pressly 1973, p. 600). The mantis seems to belong to a history of Freudian images of male decapitation/castration. In this aspect, it appears in the works of Salvador Dali, as he associated this creature with “the most frightening aspects of sex and eating—a reflection of his fear of castration by the vagina dentata” (Pressly 1973, p. 600). The image of a praying mantis reverses the prevalent surrealist cannibalistic images in which women are depicted as passive prey. We may note that both images are present in the works of Oppenheim—that of a passive woman served for consumption and that of vagina dentata. The fact that “gendered” cannibalism is so prevalent in works by male artists makes the question of why it is also utilized by woman surrealists even more significant.

4. L’objet Cannibale

Spring Banquet (Le Festin) and Cannibal Banquet are not the only Oppenheim works in which cannibalistic motifs appear. Therefore, before analyzing the banquets, Oppenheim’s other projects are described, because they also prove how the artist distanced herself from the dominant surrealist anthropophagic imagery. One of the most famous of Oppenheim’s objects is Ma gouvernante—My Nurse—mein Kindermädchen (1936)—a pair of high-heeled shoes tied together and served on a plate. They resemble a piece of poultry, ready to be consumed. The reoccurring motif is the immobilization of the woman’s body, in which she becomes passive prey. Powers suggested that this object exemplifies “a desire to be eaten” (Powers 2004, p. 240). Other researchers have emphasized the fetishistic aspect of the object (Solomon-Godeau 2013, p. 53).

The critical aspect is the figure of the gouvernante indicated in the title—here, the servant is served. The gouvernante is not a part of a family, but she is present in the household. She is vulnerable and defenseless, as taking the job of the gouvernante is sometimes the only way for young, educated and unmarried middle-class women to support themselves. Here, the figure of the gouvernante is sexualized in a cannibalistic manner. This object was interpreted from a feminist perspective as a critique of the objectification of a woman: “My Nurse takes its place in a complex social and art historical tradition surrounding the objectification and availability of women’s bodies” (Catalano 2010). Catalano read this object in reference to the connection between the woman and consumption—for instance, in the act of breast-feeding. She saw this object as a denial of breast-feeding (as the gouvernante can be read as a maternal figure but in a different manner from a wet nurse) and such “female consumability” (Catalano 2010).

The culinary setting of Ma gouvernante has the ambience of a witty dare—one might question whether Oppenheim is subversively mocking cannibalistic imagery. Her unique visual imagination discovered the startling resemblance between the tied women’s heels and poultry. Another aspect that can be mentioned is that high heels, to some extent, make women more vulnerable, limiting their capacity to move. The binding can be interpreted as a visualization of the limitations and expectations imposed on women to enforce their passivity and vulnerability. As Cox argued, it is the “literalness of this womanly body as a desiring site that challenges Surrealism’s misogynist representational hegemony” (Cox 2016, p. 348).

One of the distinctive aspects of Oppenheim’s oeuvre is its playfulness and witty irony. This is also visible in the case of another object, entitled Bon appétit Marcel! (The White Queen) from 1966. The object consisted of a chess board on which a plate is placed with a knife, fork, and napkin. In the middle, there is a form made of dough shaped to resemble a chess queen. Next to it is a half-empty glass. Here, the most powerful chess figure, the queen, is placed on a plate, defeated and defenseless. However, inside the soft labial-shaped dough, the artist put a partridge spine in such a way that it resembles teeth. Here, the vulnerability of the figure is merely an appearance, for even though seemingly helpless, she poses a threat, as the bony spine could be something to be choked with.

Consequently, the wish “Bon appétit”, which appears in the title, is filled with irony, because consuming the queen does not promise pleasure but potential risk. The shape of the figure with the teeth inside recalls the image of a vagina dentata (see Solomon-Godeau 2013, p. 47). In this context, Kriebel stated that “ambivalence is made physical: the edible woman as vagina dentata threatens lingual castration. Eat up and choke, Marcel. Chess is war” (Kriebel 2014, p. 2).

Vachhani read the vagina dentata as an ambivalent figure of a woman monstrosity that embodies both fear and desire (Vachhani 2009). She emphasized its potential to “disrupt and disturb the phallogocentric order” (Vachhani 2009, p. 163). As was noted, Powell linked the vagina dentata with the surrealist preoccupation with the praying mantis, a man-eating seductress with violent castrating femininity, in both by “linking sexual pleasure to the concept of death and dying, by making sex something to die for, something that in itself is a kind of anticipation of death” (Vachhani 2009). Vagina dentata, as a latent and hidden threat, “relates to fears of weakness, impotence or annihilation by incorporation” (Vachhani 2009). The castrating dimension of vagina dentata relates to the fear of the annihilation of the sexual difference. Louise Flockhart mentioned that a female cannibal, “as female monster, challenges the meaning of femininity, and as a cannibal, challenges the meaning of the human” (Flockhart 2019, p. 71). In Oppenheim’s object, the latent power embedded in the chess queen places it close to a monstrous figure.

There is another context that can be taken into account when interpreting Bon appétit Marcel! (The White Queen): the 1963 action in which Marcel Duchamp played chess with Eve Babitz at the Pasadena Museum of Art. The famous photograph of the event, taken by Julian Wasser, presents Duchamp and Babitz sitting at the chess board in front of Duchamp’s artwork, The Bride Stripped Bare by Her Bachelors, Even (1915–1923). Resonating with this artwork, Babitz is naked; her long hair covers entirely her face, which Claudia Mesch read as a rejection of her subjectivity (Mesch 2006). On the contrary, Duchamp is dressed, and his face is visible. Mesch emphasized the gender-conventional aspect of this setting, as the photograph of the match “visually conforms to a long lineage of female nudes retinally transformed into objects by male artists” (Mesch 2006, p. 24). In a conventional way, the image of an objectified naked woman is cannibalized. In this perspective, the ironic gesture of Bon appétit Marcel! can be related to this event, reversing the dominant power relation—”Eat up and choke, Marcel!” (Kriebel 2014).

5. Spring Banquet—Le Festin

Photographs documenting the two events—Spring Banquet (Le Festin) and Cannibal Banquet—seem to capture almost identical situations. The crucial and common element is a naked woman lying on a table, surrounded by food, which is placed both on her body and on the tablecloth around her. The initial resemblance might be misleading, however, because those two performances were essentially non-identical.

What makes the differentiation between Spring Banquet and Cannibal Banquet even more complicated is that the photographs documenting those events and their titles are sometimes inaccurately assigned. Another source of perplexity is the fact that the photograph reproduced in the EROS catalog7 is actually of the original Le Festin and not of Cannibal Banquet, which was staged at the opening of the EROS exhibition (see Breton 1959).

The original Le Festin took place in April 1959 in Bern. The date was an essential component of the performance, because the symbolism of spring and the rebirth of nature was a significant context for the whole event.

The sole existing photo from the original event (taken by the artist herself) is blurred and shows a nude woman, with her face painted and head adorned with plants. She is lying among food products and flowers. The photo does not capture anyone eating or sitting at or standing next to the table. This is not accidental, because Oppenheim recalled that the photo was staged during a private event, and she never mentioned the names of the participants (“there were three couples present”8—Oppenheim 2013, p. 245). However, she described in detail the preparation of the setting and her first meeting with the model, and she noted the reactions of her friends (Oppenheim 2013, pp. 244–45). She mentioned that it took place at her friend’s place—in the painter’s studio. Spring Banquet was an amicable feast designed to celebrate life, pleasure and rebirth. It had an intense erotic aspect emphasized by the model’s nudity and the fact that the revelers did not use cutlery or hands but ate directly from her body with their mouths.

Oppenheim recalled the event:

In the centre, there was a long, narrow table covered with a white cloth that hung down to the floor. The girl lay down on top; I covered her feet and lower legs and her hands and forearms with white cloth napkins, and I painted her face [and neck] gold (a cream of gold bronze and vaseline). Her head (her hair had been tied back) was covered with roses and mimosas, and from here candied fruits of every colour poured down to her shoulders. I’d placed empty lobsters, ‘feelers’ pointing upward, on her legs. Then came the hors d’oeuvres (lobster and mayonnaise), a large steak tartare, followed by a belt of raw mushrooms and cream. On her breasts, whipped cream, with grated chocolate on the right and raspberry puree on the left, the whole strewn with candied violets. Ladyfingers were arranged along the girl’s chest and arms. I provided the parts of the table left uncovered by the girl’s body with a dense sprinkling of wood anemones. There were five champagne glasses placed among the flowers, but no plates or cutlery, of course. These preparations took just under half an hour.(Oppenheim 2013, p. 244)

Le Festin resembles a secret, primeval or pagan ritual for a few initiates who are admitted to participate. This ritualistic aspect was highlighted by Oppenheim and is mentioned by researchers (see Gorsen 1997, p. 35; Poprzęcka 2012). The woman-table in Le Festin becomes a source of fertility, symbolically connected with vegetation. She seems to embody the soil from which everything grows and the chthonic forces of nature. The setting evokes the impression of cornucopian abundance. This sacral aspect is emphasized by the flower-crown and the painting of the model’s face in gold, which makes her resemble an ancient or pagan goddess (for instance, fertility goddesses Pomona or Cybele). Analyzing Le Festin, Gorsen brought up the context of matriarchal cults connected with the “equinox festival” and recalled the figure of Ostara—the spring goddess embodying the “wild force of youth and beginning” (Gorsen 1997, p. 35).

However, another reading is possible—the model embodies contrasting identities because she can be interpreted both as a goddess and as a sacrifice9. The table becomes an altar where she lies among other offerings. Lothar Kolmer mentioned that the ritual feast creates a community from both horizontal and vertical perspectives (Kolmer and Gottwald 2009, pp. 11–12). Horizontally, it creates social bonds among the participants, whereas vertically, it connects them with the Divine. In this perspective, the table-altar becomes an axis mundi that connects the disparate realities of the sacred and profane.

It can be argued that, in Spring Banquet, Oppenheim reproduced the stereotypical patriarchal imagery that places women close to nature, irrationality and vegetation. Gauthier mentioned various surrealist ideas and representations of femininity, among which many are connected with this woman–nature interrelatedness (Gauthier 1971, pp. 98–158). Oppenheim’s Le Festin reflects some of those types of representations—such as the connection between women and flowers (la femme-fleur), trees, plants, the landscape, Earth and different elements.

This link between femininity and vegetation is a reoccurring motif in Oppenheim’s oeuvre. For instance, in her cycle depicting the Four Elements, Earth (The Four Elements. Earth, 1963) is represented as a smiling woman whose body merges with the trees and soil around her. The lemniscate form of her body resembles the infinity symbol; she is one with the world and embodies the never-ending cycle of life. A direct reference to vegetation also appears in Oppenheim’s work, The Secret of Vegetation (1972), which refers to the opposing forces of nature.

The primaeval feature of Le Festin brings to mind Oppenheim’s terracotta sculpture10, Primeval Venus (Urzeit-Venus, 1933/1962). The radical simplicity of the form of the woman’s body and the language of synthesis recalls the Paleolithic Venuses. Instead of a head, Oppenheim’s terracotta figure has a piece of straw—once more, the woman’s body relates to the idea of fertility and vegetation. Analogously to the aforementioned drawing of Earth from the Four Elements cycle, here also, the plants grow directly from the woman’s body. The resemblance of the object to the prehistoric figurines evokes the idea of Magna Mater, in view of the fact that they are often read as primitive symbols of fertility. Orenstein mentioned that, in search of their identity, woman surrealists repeatedly refer to symbolism related to the Feminine Archetype—for instance, the Woman as a Goddess or Great Mother, which positions them closer to the image of Magna Mater than the figure of femme-enfant often imposed by male surrealists (Orenstein 1975, pp. 34–35).

Lisa Jaye Young linked Oppenheim’s interest in nature with her upbringing near the Jura Mountains close to Bern, where she spent her childhood. She interpreted Le Festin as a

sensual return to “female” spirituality, but also as the apogee of Oppenheim’s spirit of renewal and faith in Nature. It is a living testament to the artist’s philosophy of binding the body closely to the cycles of life and its sustenance, death and its inevitability.(Young 1997, p. 51)

The naked model has her eyes closed; she is passive, immobilized and dangerously intermingled with the food products around her. In this perspective, Festin can be read as a narrative about a cycle, as the setting has both the connotations of death/stillness but also of life, fullness and vegetation, the earth from which everything grows and to which everything returns. Schulz mentions Oppenheim’s interest in the “polarities and spiritual forces of nature, including Eros and Thanatos” (Schulz 2013, p. 125), and this entanglement is visible in the necro-cannibalistic Le Festin setting.

In her memoir, Oppenheim mentioned solicitous preparations, for instance, the gathering of wood anemones in the morning (Oppenheim 2013, p. 244). The choice of an anemone is not accidental. Its symbolic meaning connected with rebirth11, rooted in Greek mythology (Greek “άνεμος” means wind), corresponds with the overall spring renewal atmosphere of Le Festin and indicates that Oppenheim thought about every detail of the feast.

There is also the possibility to interpret Spring Banquet in connection to the artist’s biography. She was recovering from a period of inactivity and despair, which ended in October 1954, as she mentioned—“without the external occasion” (Oppenheim 2022, p. 315). She recalled that, during a crisis, she often dreamt about the winter: “it was always winter—completely white, devoid of life” (Oppenheim 2022, p. 315). In 1949 in one of her dreams, a rabbit appeared, signifying rebirth, which was yet to come (“at least it was a living thing—and a symbol of fertility to boot” Oppenheim 2022, p. 315). It is visible that nature and fertility had an intense personal meaning for her. In this perspective, Le Festin can be read as a celebration of personal growth in which her own “spring” is inscribed into the cycle of nature. Consequently, the amicable and intimate aspect of Le Festin becomes understandable as a private celebration of life, creativity and overcoming despair.

What is evident in Le Festin is the erotic atmosphere in which the pleasures of eating intermingle with sexual desire. The banqueters are supposed to eat directly from the model’s body, without the use of cutlery or hands, and the idea that they would touch the naked body with their lips emphasizes the erotic cannibalistic tension of the banquet. The absence of cutlery highlights the feast’s primeval aspect but also enhances the pleasure of the eaters (and perhaps of the model).12 Eating straight from the woman’s body enhances the sensuous and sensual aspect of Le Festin, evoking the impression of proximity and intimacy. Oppenheim orchestrated a sensory ritual in which the pleasures of touch, smell, sight and taste are combined.

In Spring Banquet, orality and tactility are strongly emphasized. Barbara Kirchenblatt-Gimblett mentioned that oral pleasure is connected both with eating and sexuality, as “gastronomy and eroticism share not only touch but also appetite and oral pleasure” (Kirshenblatt-Gimblett 1999, p. 2). The taste experience is present in both sexual encounters and in eating. Touch is often described as a sense connected with intimacy and proximity (Classen 2020); however, the most intimate relationships are associated with not only touching and smelling but also tasting the body of the other (sexual partners, the infant and mother). This can be why one of the aspects of cannibalistic imagery is the erotic potential and tension embedded in anthropophagic metaphors, as both cannibalism and sex are powerful metaphors of incorporation (see Kilgour 1990). This cannibalistic erotic desire can be present on both sides—one might feel the urge to consume the other (as Dali wanted to swallow Gala), but one might also feel the desire to be consumed, to vanish entirely and dissolve into the other. In his well-known essay, Levi-Strauss stated that cannibalism is not limited to consuming flesh and bones but any form of consumption of bodily fluids (blood, semen, breast milk, saliva, etc.). (Lévi-Strauss 2016, p. 86).

Surprisingly, although cannibalistic imagery is significantly present in Le Festin, it does not evoke a feeling of danger, nor does it seem to have aggressive connotations. Although the woman is in the center of cannibalistic scenography, she is not meant to be annihilated or destroyed.

The relationship between food and femininity has a long tradition and is often described by scholars of food studies as almost culturally universal (Counihan 1999, p. 96), which is based on women’s stereotypical role as nurturers and caregivers. Furthermore, the fact that they become a source of nutrition for children during pregnancy and lactation contributes to this interrelation. Spring Banquet continues the ages-long tradition in the art of representing women with food; however, in this example, a nude woman metaphorically becomes one with the food to be consumed.

Both food and sex share the incorporation of substances and crossing the boundaries of one’s body. Carole M. Counihan mentioned that food and sex metaphorically overlap, as “eating may represent copulation, and food may represent sexuality.” (Counihan 1999, p. 9). She pointed to associations among eating, intercourse and reproduction; hence, both eating and copulation cause and symbolize social connection (Counihan 1999, p. 9).

This social and intimate aspect is vital to the interpretation of the difference between Spring Banquet and Cannibal Banquet. In her description of the feast, Oppenheim concentrated on the reaction of her friends—when they saw the scenography of the feast, they were in awe. The descriptions indicate that the banqueters knew each other and felt comfortable in each other’s company. In her memories, Oppenheim recalled the playful and friendly atmosphere that accompanied the feast (“My friends had been waiting in the next room, and I called them in. It was such a beautiful sight that they all busted out in enthusiastic cheers”. Oppenheim 2013, p. 244). One of the critical aspects is that the banquet did not have any outside spectators, only participants. The ritual feast was not observed or documented by anyone who did not directly participate.

The passiveness and indifference of the model could bring to mind even necrophagic connotations, as the food was eaten from her motionless body, and her eyes remained closed. Despite her strong bodily presence, she remained absent and distant throughout the feast.

The stillness and inactivity of the model might create the risk of objectifying a woman’s body. It was even noted by the model herself—after Oppenheim described the idea of Le Festin, she commented on her role as “une pièce montée, en somme” (Oppenheim 2013, p. 244), referring to decorative confectionery in an architectural or sculptural form.

However, after the feast, the model was also invited to participate:

After everyone had had enough to eat, we sat down and drank coffee. The girl was taken to the bathroom and returned with her clothes on to eat the same menu we had (we’d set the food aside for her). So as to prevent any misunderstanding: there were three couples present. Three men and, including the woman as a table, three women. So it wasn’t ‘woman as sex object for men’. Rather a spring banquet, I would even say, a spring fertility rite for all.(Oppenheim 2013, p. 245)

Oppenheim stressed that the aspect of community was crucial, and I would argue that the artist was able, to some extent, to overcome the threat of objectification that was present in the setting of Le Festin. She did this by allowing the model to participate in the feast. Recalling the performance, she stressed that they all waited and also left the food for the model. By participating in the banquet, the model somehow regained her subjectivity. In a significant reversal, she consumed the food that was displayed on her body, visualizing the concept that “you are what you eat”13. With the act of incorporation, she became one with the cornucopia offering. Her partaking in the meal allowed her to transcend the act of objectification to which she was subjected. The model was able to escape her immobility and passivity, and, in a way, she was brought back to life, symbolically overcoming the forces of death. Claude Fischler mentioned the etymology of the word “to participate,” which

has its etymology in the Latin pars capere, literally to have one’s share of a sacrificial meal, to take part, hence to be part of, to have one’s place in, a group, an institution or an event.(Fischler 2011, p. 536)

In Le Festin, the feast is thought to reinforce the amicable relations between the revelers. The social bonding aspect of commensality is a crucial context of this feast because “commensality is undeniably one of the most important articulations of human sociality” (Kerner and Chou 2015, p. 1). Interestingly, Oppenheim mentioned that the model was chosen based on her physical attractiveness (“I told them about a pretty girl I’d met in a restaurant a few weeks before (…) She was well-dressed, slender, and blonde”) (Oppenheim 2013, p. 245). Oppenheim emphasized that both women and men participated in the feast. Oppenheim did not consider Spring Banquet to be a spectacle for a male gaze, nor was it thought to fulfill the male desire. Moreover, Gorsen observed that, in the “matriarchal and mythological Berne spring banquet, the male participants only played a subordinate, receptive role (…)” (Gorsen 1997, p. 35). Although the matriarchal aspect of Le Festin is mentioned by numerous scholars (Gorsen 1997; Poprzęcka 2012), it does not mean that Oppenheim’s work can be easily interpreted from the feminist perspective. The artist’s approach toward feminism was not one-dimensional, and she repeatedly questioned her relationship with feminism, especially in the context of the “women-art” exhibitions. Instead, she emphasized that, for her, art had no gender, and she placed herself closer to the Jungian-inspired concept of androgyny and of a “holistic, androgynely poled future human being” (Gorsen 1997, p. 37). The unity of femininity and masculinity in a single being for Oppenheim was a way to “overcome conflict between her gender identity as a woman and the traditional attributes and behavioral patterns of womanhood” (Eipeldauer 2013, p. 15).

It should be observed that, in Spring Banquet, femininity is celebrated both by men and by women; there is no desire to destroy it or humiliate it with the act of incorporation. This is in contrast to the futurist and surrealist ideas in which the consumption of a woman is a way to fulfill the male desire. However, the crucial question is whether Oppenheim’s intentions were interpreted according to her ideas. The history of Cannibal Banquet suggests that, perhaps, Le Festin was misinterpreted from the beginning.

6. Cannibal Banquet

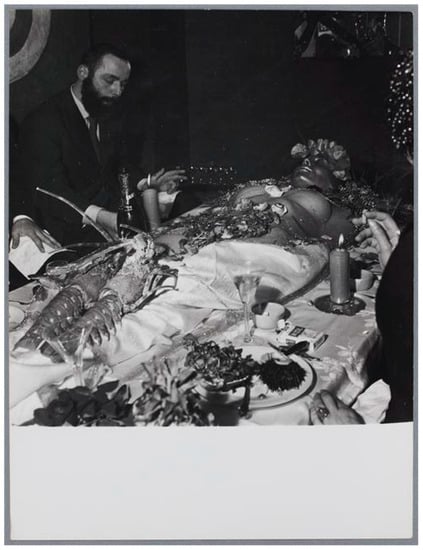

In an interview with Robert J. Belton, Oppenheim recalled the origins of Cannibal Banquet (Figure 1):

The feast at the EROS exhibition in 1960 started out as a spring festival for friends in Bern. Breton heard that I had served a meal on a nude woman and asked that I recreate it for the EROS show. But the original intention was misunderstood. Instead of a simple spring festival, it was yet another woman taken as a source of the male pleasure. There’s always a gap between aims and public comprehension.(Belton 1993, p. 70)

Figure 1.

EROS à la Galerie Daniel Cordier (1959–1960). Meret Oppenheim, Cannibal Banquet (Feast), 1959. Photo: Van Hecke Roger, Photo (C) Centre Pompidou, MNAM-CCI Bibliothèque Kandinsky, Dist. RMN-Grand Palais/Fonds Breton © 2022, ProLitteris, Zurich.

To fully understand Oppenheim’s disappointment with the EROS exhibition, it is crucial to trace the changes that affected the overall ambience of the feast. They were so significant that it is possible to question whether it is accurate to describe the second event as a reenactment of the original Le Festin.

In the catalog of the EROS exhibition, Meret Oppenheim is listed among the participating artists; she is also mentioned on the first page (“le festin inaugural est regle par Meret Oppenheim”). However, her firm critique of the event proves that she did not possess complete control over this action. Moreover, in one of the letters, she mentions “I organized the festin in December against my conviction, only on Andre Breton’s insistence” (Letter to Peter Gorsen, reproduced in: Krinzinger 1997, p. 30)

Cannibal Banquet should be viewed in the context of the whole EROS exhibition. Exposition inteRnatiOnale du Surréalisme took place from 15 December 1959 to February 1960 at the Galerie Daniel Cordier in Paris. The title EROS drew attention to the centrality of love in surrealist thought. Annette Michelson indicated that the surrealist concept of love “is haunted by the Platonic myth of a final fusion of the sexes in an androgynous union, the symbol of that paradisiacal state in which all contradictions, tensions, and antinomies are resolved” (Michelson 1960, p. 32). This concept can be one of the sources of cannibalistic imagery, in which the sexual difference is erased with the act of incorporation. Cannibal Banquet was performed during the opening of the EROS exhibition, and afterward, it was replaced with an eerie mannequin setting that resembled the inaugural banquet.

The first evident change is the title; however, it is not clear when this change occurred. In Spring Banquet, the cannibalistic aspect was somehow in the background; it was present but not central to the interpretation of the banquet. With the change in the title, a direct emphasis is put on the anthropophagic aspect as a violent and unsettling dimension of the feast. There is no direct evidence that it was Breton who interfered with the title of Oppenheim’s work, as had happened with the famous fur teacup, because the title Le Déjeuner en fourrure was given by him and significantly affected later interpretations of the artwork.14 Commenting on those appropriations, Oppenheim surprisingly distanced herself from the linguistic aspect (it is, nevertheless, well known that language was important to her15). Oppenheim commented in an interview on this situation: “the word-games of critics, the power struggles of men!” (Belton 1993, p. 68). Those words put her withdrawal in a different context—not as a surrender to male dominance but as a conscious and ironic distance toward the male urge to dominate. With this declaration, she consciously situated herself outside a discourse in which she did not want to participate. She assumed the place of an ironic observer who held that refusing to participate in a game in which the rules are set by others is the only way to win. In the case of Cannibal Banquet, it was not only the title that changed but the whole context of the banquet.

Photographs from the event taken by Roger van Hecke show a half-naked woman lying on a table; her eyes are closed. The model’s legs are covered with a white tablecloth, and there are lobsters placed on each of her calves. She is adorned with flowers; her face is painted gold. She is surrounded by objects placed on the table—cutlery, a bottle of champagne, glasses, a pack of cigarettes, plates and candles. It is visible that people are sitting around the table, both men and women.

One of the most disturbing photographs shows a bearded man standing with a knife and fork in his hands. He is leaning down and cutting something; however, from the perspective of the photography, it seems that he is cutting directly into the body of the naked woman. The seemingly minor change from Le Festin to Cannibal Banquet (the addition of cutlery) creates a sense of distance, and the intimate closeness of touching the naked body with lips is now absent. It also brings forward the violent aspect of this staging; the model is somehow attacked with sharp utensils. This is why the photo with the man holding a knife is so disturbing. Belton mentioned surrealists’ interest in the “phallic cult of the knife” and connected it with their fascination with perversion and sex crime (Belton 1995, p. 139).

It should be noted that, during the inauguration, the banquet was observed by the viewers, who did not participate in it directly but witnessed it from behind metal bars, which accentuated the spatial distance between the banqueters and the audience. Maria-Rosa Lehmann quoted Jean-Claude Silbermann, who remembered having to loosen the hands of men gripping the bars because they wanted to participate in the situation in a more direct manner (plusieurs fois desserrer les mains d’hommes accrochées aux barreaux) (Lehmann 2017, p. 20).

Scholars emphasize the violent sexual aspect of Cannibal Banquet’s theatrical staging. Highlighting the intensity of the voyeuristic violence, Lehmann wrote that

The woman-table, the edible, cannot defend herself either against her true rapists, those who eat it, nor against the passive rapists, the spectators-voyeurs, those who watch it. Through the gaze, the surrealists force situations of communication or confrontation between their public and their performances.(Lehmann 2017, p. 20)

She argued that the public takes a position of voyeuristic power, because Cannibal Banquet concentrates on the fetishistic nudity in which a woman’s body is objectified (Lehmann 2017, p. 14). She considers this performance to be the culminating point of surrealistic voyeurism, and with the transformation of the woman into the object to be consumed, the nude is cannibalized by both the banqueters and the gaze of the observers. For Lehmann, they are guilty of the act of violence, similar to that of the banqueters. The fact that photographs from the event show that women also participated directly in this cannibalistic setting can lead to the question of the role of women in sustaining and reinforcing patriarchic structures.

The art historian Maria Poprzęcka accurately described the changes made compared to the original Le Festin:

There [in Le Festin—A.S] woman was the object of men’s homage—here she became a dish served for men as an elegant dinner. There was the altar—here buffet. And everything in a very surrealistic mode which had put a woman in the role of a food product, serving to satisfy erotic hungers—served to be eaten, bitten, licked. Even to be drunk—as in Rene Magritte’s painting in which the naked woman is corked in a bottle.(Poprzęcka 2012, pp. 214–15)

Placing Cannibal Banquet in the environment of the whole EROS exhibition allows us thoroughly to grasp how the context affects the meaning(s) and readings of the banquet. The “profoundly theatrical” EROS was not a conventional presentation of the artworks but rather a total, Gesamtkunstwerk-like experience that engaged various senses.16 (see Michelson 1960; Harris 2020). Viewers proceeded from one room to another, each with elaborate scenography. The viewers’ journey among grotto-like venues concluded with the last space, where Cannibal Banquet was presented17. The space was described as an “architectural facsimile of the vaginal grotto, the tunnel of love” (Michelson 1960, p. 37). Metaphorically, the viewers were penetrating the female’s body, and this journey concluded with the act of consumption:

at one end of this room on opening night, seated behind an iron grill, several ladies and gentlemen were feasting, as in a Sade tale, upon lobster and champagne, about a table on which was the naked and recumbent body of another lady. Since the night of the vernissage, table and guests have been replaced by wax models. The walls are red, and on them are hung—or impaled—the elements of a vast and elaborate panoply. These constitute, when reassembled, a ritual costume, designed and worn by M. Jean Benoît at the solemn, commemorative ceremony in honor of Sade held before the opening of the exhibition.(Michelson 1960, p. 32)

Cannibal Banquet was presented next to Jean Benoît’s work, and it may be argued that this spatial layout was not accidental and evoked the memory and writings of the Marquis de Sade. Benoît’s action, Exécution du testament du Marquis de Sade, which took place on 2 December 1959, had an extreme autoaggressive aspect, because he “branded himself with a red-hot iron bearing the letters S-A-D-E.” (Harris 2020, p. 576). By leaving this imprint on his body, Benoît emphasized the influence that philosophy and the writings of the Divine Marquis had on surrealists. What connected Cannibal Banquet and Benoît’s work was that, after the initial actions, they were presented during EROS solely as residues, “leftovers.”

An intense connection between eroticism and violence is prevalent in Sade’s writings (Phillips 2002–2003). In Sade’s novels, sex is often connected with power and the desire to control, torture and violate women’s bodies. In Sade’s imagery, cannibalism is an act of extreme violence, a form of definitive humiliation and objectification of the human. In Juliette, the acts of cannibalism are performed by Minsky—a terrifying, almost unhuman giant18 who lives in a remote castle where he engages in his abominable activities. He consumes women and young boys, and in a gruesome scene, he invites his guests to eat human flesh while sitting at a table and chairs formed from living women’s bodies. Katherine Martinez discussed cannibalism as a “highly gendered patriarchal phenomenon in which men and masculinists propensities are privileged in the literal and metaphorical consumption and control of women’s and feminized male bodies” (Nyamnjoh 2018, p. 55), and this gendered aspect of anthropophagic imagery links Sade’s writings with Cannibal Banquet.

Cannibal Banquet is not the only surrealist work in which anthropophagic imagery is connected to Sade’s violent eroticism—it is also visible in the photograph by Man Ray from 1930, titled Hommage a D.A.F. Sade19, which was published in Le Surrealisme au service de la revolution, no. 2 (see Belton 1995, p. 139; also Chadwick 2003, p. 214; Bate 2020). The photograph depicts a result of decapitation. The woman’s head, seemingly detached from the body, is presented under a glass bell jar. Her eyes are closed, and her mouth is slightly open. Chadwick compared this staging to “a piece of cheese or a sacred relic”, in which the head resembles “a wax effigy, a fetish, a memento mori” (Chadwick 2003, p. 214). In a typically surrealist manner, the woman is portrayed as a trophy or prey—immobilized, defenseless and dismembered. Reflecting on the patriarchal violence that affects both women and nonhuman animals, Carol J. Adams described the cycle of objectification, fragmentation and consumption (Adams 2015, p. 27). Adams reflected on the images of metaphorical sexual butchering in which women’s bodies are reduced to meat. Representations that collapse sexuality and consumption have been described by various feminist writers as “carnivorous arrogance”, “gynocidal gluttony,” “sexual cannibalism”, “psychic cannibalism” and “metaphysical cannibalism” (Adams 2015, p. 41). Cannibal Banquet’s immobilized body (as Lehmann noted, this stillness is emphasized by partially covering the legs of the naked model with a tablecloth) served on a table might metaphorically position the model as a piece of meat ready to be cut into with a knife and consumed. The positioning of a human or nonhuman entity as meat radically rejects its subjectivity and reduces it solely to the function of a comestible.

As Neil Cox writes, “The increasing importance of Sade was connected to the idea that Surrealism stood for the liberation of sexual desire, and the celebration of desires and sexual acts that flew in the face of bourgeois moral conservatism” (Cox 2016, p. 341). It is clear that, in the case of Cannibal Banquet, the aspect of shock is crucial, seeing that breaking one of the strongest food taboos was aimed at disturbing bourgeois society. Paul Éluard wrote that “Sade gives back the civilized man the force of his primitive instincts,” (Éluard 1926, p. 9) and for ages, the “cannibal” has remained as a figure of the “primitive” and “savage”, also in order to justify colonial oppression (see Nyamnjoh 2018, p. 12). The cannibal is placed beyond the bounds of acceptable society, establishing the external boundary of culture. Boëtsch mentioned that, in XIX-century anthropology, there is a tendency to consider anthropophagy as a status of mental inferiority, and “certain authors considered it would affect only the most inferior ‘races’, the most bestial, or those most incapable of the least refinement” (Boëtsch 2004, p. 61).

However, the image of the cannibal in Cannibal Banquet is not that of a savage but that of a cultured one. Here, the savage is not positioned outside as the “Other” but appears within the “civilized,” highlighting that “primitive” instincts are present in the unconscious of the civilized and are being resurfaced. In Cannibal Banquet, the cannibals wear elegant suits, use cutlery and drink champagne. The dark impulses and desires are not placed outside the culture but are a reflection of the unconscious, present within contemporary society.

The fact that, after the opening of the EROS exhibition, the model was replaced with a mannequin puts Cannibal Banquet even further away from the original Le Festin. The woman was eaten and replaced with a wax model— which can be read as a consequence of the desire to completely remove a woman’s subjectivity and replace it with an object. In Le Festin, there was an attempt to transcend the act of objectification by inviting the model to participate in the feast and overcome her immobility and passivity, whereas in Cannibal Banquet, these became reinforced. Mannequins are a crucial motif of surrealist fetishism and a figure of male desire. The surrealist fascination with dolls and mannequins is connected with the “unconscious as well as with the uncanny”, as it “unsettles our everyday expectations of the real and the imagined, the living and the dead” (Lusty 2016, p. 138). Lusty mentioned that, in Freud’s writings, the doll represents the “passive feminine object who merely reflects male desire and identity, albeit one in crisis” (Lusty 2016, pp. 92–93). According to Freud, the idea of a living doll is connected not with infantile fear but an infantile wish, a childhood desire for the inanimate to come to life (Lusty 2016, p. 138). In Cannibal Banquet, not only is the nude woman replaced by a wax figure, but so too are the banqueters. The uncanny wax figures present the scenography of a strange museifictation. The complete stillness of this setting is an antonym of the life cycle and rebirth, which is of the essence in Le Festin.

Steven Harris mentioned the photo shoot organized for Vogue magazine by William Klein (Harris 2020). The famous photo shows several surrealists (Ivsic, Parent, Benayoun, Mitrani, Benoît, Breton, among others) and Vogue models gathered around the Cannibal Banquet table, with the wax model lying among food products. Harris accentuated the “association of ‘mannequins en cire’ (wax figures) and ‘mannequins vedettes’ (supermodels)” (Harris 2020, p. 580). He also mentioned that the models are wearing fur, and he saw it as an allusion to Oppenheim’s fur teacup. However, what is most striking in both the photo and the text that accompanied it is the absence of Oppenheim—she is not among the sitters, nor was she mentioned as the author of the work.20 Continuing with the cannibalistic metaphors, in a way, Oppenheim was devoured again by Breton. He incorporated her artistic ideas and appropriated them. Interestingly, an initially disturbing and unsettling image became a pretext for photography to be reproduced in a commercial fashion magazine. As Virginie Pouzet-Duzer wrote, “Festin cannibale represents at the same time Surrealism’s consumption and the end of cannibalism’s effectiveness as poetic concept—and this is perhaps why its image was quickly cannibalized itself by the consumer society” (Pouzet-Duzer 2013, p. 88).

7. Conclusions

Comparing the two versions of the feast demonstrates the importance of the circumstances of the presentation. Changing the title, context of the feast, place, participants and way of eating all contribute to a different reading of a seemingly similar cannibalistic setting, in which a naked woman is placed on a table among food.

Spring Banquet took place in April as a rite of spring; Cannibal Banquet was staged around the winter solstice. The changes from the initial version are evident, and we might question whether it is possible to describe them as two different versions of the same performance or whether we should treat them separately. Lehmann claimed that the distinction is not total and that, even though Breton “underlined the darker meaning of the performance, he did not undermine the original idea of celebrating woman and nature”. (Lehmann 2014). However, the matriarchal festive interpretation that dominates in the case of Le Festin is impossible with Cannibal Banquet. It is visible how the aforementioned changes affected the interpretations. In both stagings, the woman was presented for consumption. Her nudity was consumed visually, and the banqueters ate food directly from her body. The crucial difference is the intimate and private atmosphere of Le Festin, contrasted with the violent voyeuristic enjoyment of Cannibal Banquet. Therefore, the spring festive was transformed into “the festival of erotic cannibalism” (Poprzęcka 2012, p. 215)

It is also noteworthy that Oppenheim did not approve the changes, and she claimed that they altered the meaning of the work. Oppenheim criticized the dominance of male pleasure, and she struggled to “identify with the brutal surrealist eros which she experienced as brutal and tragic for the ‘second sex’” (Gorsen 1997, p. 35). Her disappointment with Cannibal Banquet was so profound that it made her question her position within the surrealist movement, as the “weird fantasies of après-guerre surrealism made her sick” (Lehmann 2014). The cannibalization of the original idea was so widespread that, in a letter written in 1974 to Peter Gorsen, in his book, Sexualästhetik, Oppenhim said that she is not mentioned in connection with the photo of the banquet (Letter to Peter Gorsen, reproduced in: Krinzinger 1997, p. 30). Repeatedly, Oppenheim was overlooked or not mentioned in the context of her involvement in the initial idea of Le Festin, the work that led to the creation of Cannibal Banquet. The side-to-side analysis of both banquets proves the vital importance of the artistic strategies connected with the context of their exhibition. Seemingly minor changes profoundly affected the meaning and ambience of the work, shifting them from a celebration of intimacy to a violent spectacle.

Even though Oppenheim’s initial Le Festin idea became appropriated and cannibalized, it found some continuation—for instance, in the 1992 performance The Banquet, which was a collaboration by Hunter Reynolds and Chrysanne Stathacos. In this performance, they referred to the original Le Festin, but by replacing the female with a male body and “blatantly confronting issues of male dominance throughout (art) history,” (Denson n.d.) as the queer ritual festive progressed, it became clear that “the real sacrificial victim to be shredded and devoured that night was Patriarchy” (Denson). Reynolds and Stathacos’s reference shows not only the vitality of Oppenheim’s feast but also the relevance of cannibalistic imagery, which always seems to revolve around hierarchic structures. Nyamnjoh argued that our contemporary understanding of cannibalism is diverse and metaphorical, and it encompasses various hierarchies—(post)colonial, gendered, class, etc. His words testify to the universality of the cannibal figure: “we are all cannibals when, through our vacuous claims of superiority or supremacy, we act, socially, politically, economically and culturally to make life impossible for others.” (Nyamnjoh 2018, p. 57).

The comparison of Le Festin and Cannibal Banquet shows that they represent contradictory aspects of anthropophagic imagery. Heike Behrend discussed the various meanings of anthropophagy, as “cannibalism, in its different, contradictory forms sets up not only the opposition but also the dissolution of the opposition between the self and his or her other”. (Behrend 2011, p. 41). Cannibalistic imagery is somehow paradoxical in itself—it is utilized to describe acts both of love and of extreme violence. It can signify hostility or longing for an impossible absolute unity. Behrend also mentioned those contradictory (positive as well as negative) connotations of cannibalism:

at one extreme, cannibalism is a somewhat suspicious figure of transcendence, an act of union and love, an utopian yearning for a lost unity and oneness, thereby bridging even the divide between eating and being eaten; at the other side of the continuum, cannibalism is an abominable act that not only attempts to kill but also to annihilate its victim.(Behrend 2011, p. 44)

Cannibalism obliterates the difference between the Self and the Other because “ingestion or incorporation invariably results in losing, more or less permanently, that which one is ingesting, incorporating, assimilating and using to reassert oneself” (Nyamnjoh 2018, p. 20). However, the question is whether this act of incorporation in surrealist works leads to the erasure of feminine subjectivity or to androgynous union.

The image of cannibalism appears in Oppenheim’s oeuvre on numerous occasions. However, it is clear that it was not utilized to convey the exact same meaning. In Le Festin, cannibalistic imagery is evidently present; however, Oppenheim attempted to detach it from its brutal and aggressive connotations, shifting the focus to issues of rebirth, the cycle of nature and an amicable celebration with an evident erotic component. Emphasizing the contradictory meanings of cannibalism, Behrend noted its connection with rebirth:

Cannibalism may be displayed in the anguish of mourning; it may be an aspect of the life-cycle and rituals of regeneration; it may be projected outwardly to the realm of the gods or an ethnic landscape or inwardly as an idiom of dreams.(Behrend 2011, p. 41)

Placing Oppenheim’s works in the broader context of cannibalistic motifs in surrealism proves that they have almost inseparable gendered references. Anthropophagic narratives and images are linked with the patriarchal fantasy of the metaphorical consumption of women. Those metaphors are, however, presented in an explicit and direct manner. Situating Cannibal Banquet in the setting of the EROS exhibition reveals the relationship between the surrealist anthropophagic themes and writings by Marquis de Sade.

It can be argued that, in a way, Oppenheim attempted to subvert the prevailing meanings of cannibalism in surrealism. Her irony and playfulness distance her works from sadistic or violent imagery. She utilized similar language and images, but her use of those images is individual and somehow detached from mainstream surrealism. Therefore, the anthropophagic motifs in Oppenheim’s works are not the same as those in the works of her male counterparts. She was interested in eroticism, not perversion or sadism; in intimacy, not a spectacle; and in close relationships, not the objectification of others. Moreover, she played with the idea of “being eaten” as a surrender to a man’s power, challenging the idea of objectification and the male desire as in Bon appétit Marcel!, in which the seemingly powerless woman figure shows the potential to “bite back,” reversing the stereotypical patriarchal cannibalism.

Funding

The research activities co-financed by the funds granted under the Research Excellence Initiative of the University of Silesia in Katowice. Grant number: 11491022.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Data sharing not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

Notes

| 1 | The problem of the title of this artwork is discussed further in this article. |

| 2 | “Meret Oppenheim: My Exhibition”, The Museum of Modern Art, New York, 30 October 2022–4 March 2023. Organized by Anne Umland, Nina and Natalie Dupêcher. This exhibition was co-organized and also shown at the Kunstmuseum Bern (22 October 2021–13 February 2022) and the Menil Collection, Houston (25 March–18 September 2022). |

| 3 | One of the most important examples of the interest in anthropophagy is the 24ª Bienal de São Paulo (1998) curated by Paulo Herkenhoff and Adriano Pedrosa; see Herkenhoff and Pedrosa (1998). |

| 4 | It is important to emphasize that, even though they are used interchangeably, the terms cannibalism and anthropophagy are not synonymous. Anthropofagos literally means human-eater, and as Champion notes, the term does not necessarily indicate “intraspecies consumption,” which is the base of cannibalism (Champion 2021, p. 3). Not every anthropophagic act is therefore cannibalistic, but each example of cannibalism of the human species is anthropophagic. Having remarked this point, I follow common practice and use these terms interchangeably. |

| 5 | The Futurist Cookbook opens with a narrative about Giulio Onesti, who suffers immense sadness after losing his beloved woman. Due to the impossibility of fulfilling his desire of possessing that woman, Marinetti decides to prepare for him a meal in the shape of a body. With the symbolic consumption of a woman, Giulio’s desire is fulfilled, and his melancholy is cured. |

| 6 | See, for instance, the formula for Italian Breasts in the Sunshine or Strawberry Breasts (Marinetti and Fillia 2014). |

| 7 | The photograph and the Catalogue de l’Exposition inteRnatiOnale du Surréalisme (EROS) are available at www.andrebreton.fr, accesed on 2 December 2022. |

| 8 | Oppenheim mentioned that there were three couples present; this also included the artist herself and the model. |

| 9 | One might ask about the similarity to Stravinsky’s ballet, Le sacre du printemps (The Rite of Spring)—a pagan Slavic-inspired story in which a young woman is sacrificed as an element of spring rituals. Stravinsky’s piece revolves around the return of spring and the renewal of the earth through the sacrifice of a virgin. The inspiration for the ballet was Nikolai Roerich’s concept that the renewal of the culture is only possible through a revival of Old Slavic rituals. |

| 10 | The sculpture was also cast in bronze. |

| 11 | Anemone was a nymph, a member of the court of Chloris, the goddess of flowers. She fell in love with Chloris’s husband Zephyr, was consequently exiled and eventually died of a broken heart. Zephyr asked Venus to change her body into a flower, which came back to life every spring (Lehner and Lehner 1960, p. 54). |

| 12 | The rejection of cutlery is also found in The Futurist Cookbook, in which Marinetti mentions that eating with one’s hands is supposed to give additional “prelabial tactile pleasure” (Marinetti and Fillia 2014, p. 38). |

| 13 | This famous quotation is attributed to Jean Anthelme Brillat-Savarin, who wrote in his book, The Physiology of Taste: or Meditations on Transcendental Gastronomy, “Dis-moi ce que tu manges, je te dirai ce que tu es.” |

| 14 | Oppenheim commented on this situation: “it was he [Breton—A.S] who named it playing on the associations with queer sexuality in Manet’s Dejeuner sur l’herbe and Sacher-Masoch’s Venus en fourrures.” (Belton 1993, p. 68). |

| 15 | See, for instance, the following chapter: “Quick, Quick, the Most Beautiful Vowel is Voiding. Text-Image Relationships in the Works of Meret Oppenheim” (Baur 2022, pp. 89–106). |

| 16 | Annette Michelson, in her review of the EROS exhibition, mentioned its multisensory aspect; she recalled that the floor was covered with sand, there was pink velvet on the walls, and the “silence (a hush of the boudoir and a hush of the museum) was punctuated by recorded sighs and murmurs” (Michelson 1960). |

| 17 | A drawing by Pierre Faucheux depicts a project of the exhibition space, in which each space has a designated name—«Salle du Désir», «La forêt du sexe», «Fétichisme» and «Le repaire». The “Dinner Cannibale” took place in the last one, which can be translated as “the lair.” The exhibition project is accessible at www.andrebreton.fr, accessed on 2 December 2022. |

| 18 | Among Oppenheim’s drawings, there is one of Polyphem—“Polyphemus in love” (1974), in which the cannibal cyclops is staring intensively at the audience while poking his tongue out. The cannibal is a monstrous figure, and in the narratives, the creatures who practice cannibalism are dehumanized and placed on the borders of humanity. However, the paradox of cannibalism is that, on the one hand, it puts one on the boundaries of humanity, but to be a cannibal, one must remain human. Therefore, in literature, cannibalistic acts are often performed by anthropomorphic creatures, such as giants or cyclopes. |

| 19 | Interestingly, another version of this photo exists from a different angle, attributed to Lee Miller, signed Tanja Ramm, Paris 1931 (Chadwick 2003, p. 212). |

| 20 | The text states that “André Breton, chef inconteste de l’ecole, en avait réglé la mise en scène avec Marcel Duchamp. Elle culminait en une salle dite du “festin inaugural” où hors-d’oeuvre, viandes et petits fours etaient servis sur un mannequin de cire”. |

References

- Adams, Carol. 2015. The Sexual Politics of Meat: A Feminist-Vegetarian Critical Theory. London: Bloomsbury. [Google Scholar]

- Ades, Dawn. 1998. The anthropophagic dimensions of dada and surrealism. In XXIV Bienal de Sao Paulo: Historical Nucleus: Antropofagia and Histories of Cannibalisms. Edited by Herkenhoff Paulo and Pedrosa Adriano. Sao Paulo: Fundacao Bienal Sao Paulo, pp. 234–45. [Google Scholar]

- Avramescu, Cătălin. 2009. An Intellectual History of Cannibalism. Princeton: Princeton University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Bate, David. 2020. Photography and Surrealism: Sexuality, Colonialism and Social Dissent. New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Baur, Simon. 2022. Meret Oppenheim Enigmas. A Journey Through Her life and Work. Zurich: Verlag Scheidegger & Spiess AG. [Google Scholar]

- Behrend, Heike. 2011. Resurrecting Cannibals: The Catholic Church, Witch-Hunts and the Production of Pagans in Western Uganda. New York: Boydell&Brewer. [Google Scholar]

- Belton, Robert J. 1993. Androgyny: Interview with Meret Oppenheim. In Surrealism and Women. Edited by Caws Mary Ann, Kuenzli Rudolf and Raaberg Gwen. Cambridge and London: MIT Press, pp. 63–75. [Google Scholar]

- Belton, Robert J. 1995. The Beribboned Bomb: The Image of Woman in Male Surrealist Art. Calgary: University of Calgary Press. [Google Scholar]

- Billeter, Erika, and Jose Pierre, eds. 1987. La Femme et le surrealisme. Lausanne: Musee Cantonal des Beaux-Arts. [Google Scholar]

- Blau, Anna. 1997. The Freedom I Mean isn’t a Present. Interview with M.O. In Meret Oppenheim. Eine andere Retrospektive. A Different Retrospective. Edited by Krinzinger Ursula. Zurich: Edition Stemmle, pp. 40–41. [Google Scholar]

- Boëtsch, Gilles. 2004. A Metaphor of Primitivism: Cannibals and Cannibalism in French Anthropological Thought of the 19th Century. Estudios del Hombre. Man as Meat, Universidad de Guadalajara 19: 56–72. [Google Scholar]

- Breton, André. 1959. Catalogue de l’Exposition inteRnatiOnale du Surréalisme (EROS) à la galerie Cordier de décembre 1959 à janvier 1960. Paris: Galerie Daniel Cordier. [Google Scholar]

- Breton, André. 1994. Arcanum 17 with Apertures. Los Angeles: Sun&Moon Press. [Google Scholar]

- Brown, Jennifer. 2013. Cannibalism in Literature and Film. London: Palgrave Macmillan. [Google Scholar]

- Catalano, Janine. 2010. Distasteful: An Investigation of Food’s Subversive Function in René Magritte’s The Portrait and Meret Oppenheim’s Ma Gouvernante—My Nurse—Mein Kindermädchen. Invisible Culture. Available online: https://ivc.lib.rochester.edu/distasteful-an-investigation-of-foods-subversive-function-in-rene-magrittes-the-portrait-and-meret-oppenheims-ma-gouvernante-my-nurse-mein-kindermadchen/ (accessed on 2 December 2022).

- Caws, Mary Ann. 1986. Ladies Shot and Painted; Female Embodiment in Surrealist Art. In The Female Body in Western Culture. Edited by Suleiman Susan Rubin. Cambridge: Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Caws, Mary Ann, Kuenzli Rudolf, and Raaberg Gwen, eds. 1993. Surrealism and Women. Cambridge and London: MIT Press. [Google Scholar]

- Chadwick, Whitney. 2003. Lee Miller’s Two Bodies. In The Modern Woman Revisited: Paris Between the Wars. Edited by Chadwick Whitney and Latimer Tirza True. London: Rutgers University Press New Brunswick, pp. 199–222. [Google Scholar]

- Chadwick, Whitney. 2021. Women Artists and the Surrealist Movement. London: Thames&Hudson. [Google Scholar]

- Champion, Giulia, ed. 2021. Interdisciplinary Essays on Cannibalism. Bites Here and There. New York and London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Classen, Constance, ed. 2020. The Book of Touch. New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Counihan, Carole. 1999. The Anthropology of Food and Body. Gender, Meaning, and Power. New York and London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Cox, Neil. 2016. Desire Bound: Violence, Body, Machine. In A Companion to Dada and Surrealism. Edited by Hopkins David. Chichester: John Wiley & Sons, pp. 334–51. [Google Scholar]

- Curiger, Bice. 1989. Meret Oppenheim. Defiance in the Face of Freedom. Zurich, Frankfurt and New York: PARKETT Publishers. [Google Scholar]

- Dalí, Salvador. 1993. The Secret Life of Salvador Dalí. New York: Dial Press. [Google Scholar]

- Dalí, Salvador. 2016. Les Diners de Gala. Köln: Taschen. [Google Scholar]

- Denson, Roger. n.d. The Banquet. Available online: https://chrysannestathacos.com/the-banquet/ (accessed on 25 October 2022).

- Eipeldauer, Heike. 2013. Meret Oppenheim’s Masquerades. In Meret Oppenheim. Retrospective. Edited by Eipeldauer Heike, Brugger Ingrid and Sievernich Gereon. Berlin: Hatje Cantz Verlag, pp. 11–24. [Google Scholar]

- Eipeldauer, Heike, Ingrid Brugger, and Sievernich Gereon, eds. 2013. Meret Oppenheim. Retrospective. Berlin: Hatje Cantz Verlag. [Google Scholar]

- Éluard, Paul. 1926. DAF de Sade ecrivain fantastique et revolutionnaire. La Revolution Surrealiste 8: 8–9. [Google Scholar]

- Fischler, Claude. 2011. Commensality, society and culture. Social Science Information 50: 528–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flockhart, Louise. 2019. Gendering the Cannibal in the Postfeminist Era. In Gender and Contemporary Horror in Film. Edited by Holland Samantha, Robert Shail and Gerrard Steven. Bingley: Emerald Publishing Limited, pp. 67–81. [Google Scholar]

- Gauthier, Xavière. 1971. Surréalisme et sexualité. Paris: Éditions Gallimard. [Google Scholar]

- Githire, Njeri. 2014. Cannibal Writes. Eating Others in Caribbean and Indian Ocean Women’s Writing. Champaign: University of Illinois Press. [Google Scholar]

- Gorsen, Peter. 1997. Meret Oppenheim’s Banquet—A Theory of Androgyne Creativity. In Meret Oppenheim. Eine andere Retrospektive. A Different Retrospective. Edited by Krinzinger Ursula. Zurich: Edition Stemmle, pp. 35–37. [Google Scholar]

- Guest, Kristen, ed. 2001. Eating their Words. Cannibalism and the Boundaries of Cultural Identity. Albany: State University of New York Press. [Google Scholar]

- Harris, Steven. 2020. EROS, c’est la vie. Art History 43: 564–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herkenhoff, Paulo, and Adriano Pedrosa, eds. 1998. XXIV Bienal de Sao Paulo: Historical Nucleus: Antropofagia and Histories of Cannibalisms. Sao Paulo: Fundacao Bienal Sao Paulo. [Google Scholar]

- Kerner, Susanne, and Cynthia Chou. 2015. Introduction. In Commensality from Everyday Food to Feast. Edited by Kerner Susanne, Chou Cynthia and Warmind Morten. New York and London: Bloomsbury, pp. 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Kilgour, Maggie. 1990. From Communion to Cannibalism: An Anatomy of Metaphors of Incorporation. Princeton: Princeton University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Kirshenblatt-Gimblett, Barbara. 1999. Playing to the Senses: Food as a Performance Medium. Performance Research 4: 1–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolmer, Lothar, and Franz Theo Gottwald. 2009. Jedzenie. Rytuały i magia. Warszawa: Warszawskie Wydawnictwo Literackie MUZA SA. [Google Scholar]

- Kriebel, Sabine. 2014. Meret Oppenheim Retrospective Berliner Festspiele, Martin-Gropius Bau. Available online: http://enclavereview.org/meret-oppenheim-retrospective-berliner-festspiele-martin-gropius-bau-berlin/ (accessed on 25 October 2022).

- Krinzinger, Ursula, ed. 1997. Meret Oppenheim. Eine andere Retrospektive. A Different Retrospective. Zurich: Edition Stemmle. [Google Scholar]

- Kuenzli, Rudolf. 1993. Surrealism and Misogyny. In Surrealism and Women. Edited by Caws Mary Ann, Kuenzli Rudolf and Raaberg Gwen. Cambridge and London: MIT Press, pp. 17–26. [Google Scholar]

- Latimer, Tirza True. 2016. Equivocal Gender: Dada/Surrealism and Sexual Politics between the Wars. In A Companion to Dada and Surrealism. Edited by Hopkins David. Chichester: John Wiley & Sons, pp. 353–65. [Google Scholar]