1. An Artistic Self-Betrayal?

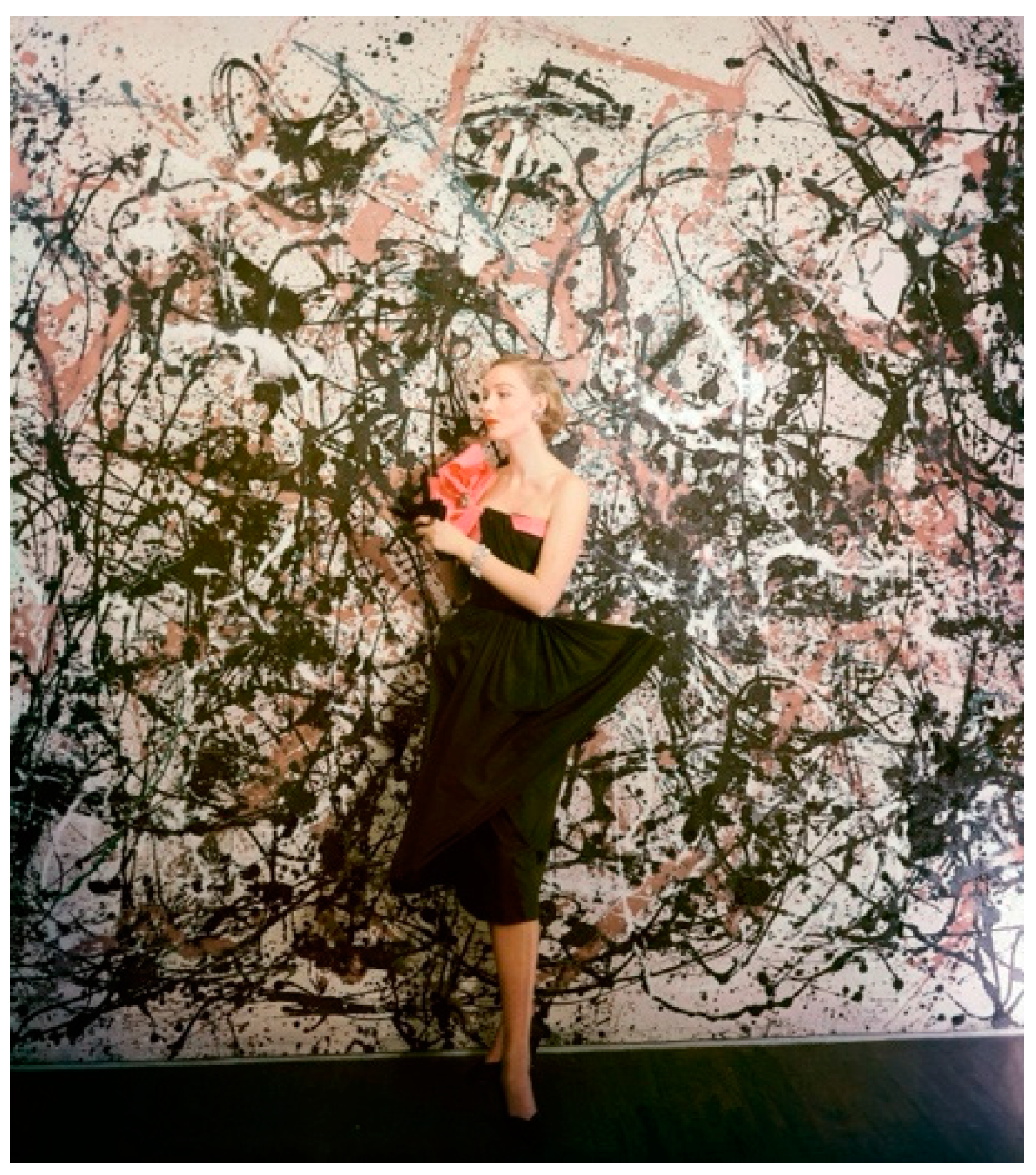

In a recent article, Donald Kuspit describes the manner in which one of Pollock’s great abstractions of 1950,

Autumn Rhythm, becomes kitsch in Sir Cecil Beaton’s fashion shoot of a glamorous model standing in front of a detail of the painting, published in the March 1951

Vogue magazine (

Figure 1). “Van Bueren’s black dress and the bouquet of pink flowers she holds echo the colors in Pollock’s painting, although her poise and elegance contradict its eccentric dynamics—the swirling turbulent quasi-grand gestures, some painterly thick, some thinly linear. But her glittering jewelry—diamond bracelet and earrings—make the subliminal point: Pollock’s painting is expensive kitsch” (

Kuspit 2020). The artist has sold his soul to the public.

Following Donald Winnicott, Kuspit distinguishes between an artist’s “True Self” and his or her “False Self” (

Winnicott 1960). To achieve success, the false self conforms with society: to gain access to a mass audience the artist pretends to be other than he or she is, the art thereby becoming kitsch. For Kuspit, Pollock’s true self is “a true avant-garde believer, a certified member of the cult of the avant-garde, the belief that being an outsider was the one and only true way of becoming creative and original”. By permitting himself to become “a public ‘personality’” in the 8 August 1949

Life magazine article, “Jackson Pollock: Is he the greatest living painter in the United States?”, Pollock invites, Kuspit suggests, the kitchification of his art that we witness in Beaton’s treatment of

Autumn Rhythm. I disagree with Kuspit on two points: I disagree, not with his appropriation of Winnicott’s distinction, but with his construction of Pollock’s true self as “a true avant-garde believer” and with the claim that Pollock came to surrender his creativity to what the public expected or demanded, allowing his art to degenerate into kitsch. As I will show, public expectations had no great impact on the evolution of Pollock’s art. What fueled it was a private spiritual quest for meaning. No doubt, Pollock welcomed the attention given to his work, attention that promised then much-needed sales. Did he thereby pretend to be other than he was?

In his 1939 essay “Avant-garde and Kitsch” Clement Greenberg, who advanced the influential definition of avant-garde to which Kuspit subscribes, explains how the burgeoning mass culture in the 1930s dictated the necessity for an “avant-garde” art to come into being if art per se was to survive. He names examples of kitsch: “popular, commercial art and literature with their chromotypes, magazine covers, illustrations, ads, slick and pulp fiction, comics, Tin Pan Alley music, tap dancing, Hollywood movies, etc., etc.”. He rails: kitsch “is vicarious experience and faked sensations … Kitsch is the epitome of all that is spurious in the life of our times. Kitsch pretends to demand nothing of its customers except their money—not even their time” (

Greenberg 1939, pp. 11, 14). To counter kitsch, the different disciplines of art would have to determine what qualities of form pertained to their field alone. Painting, for example, would have to forego the three-dimensional sculptural illusionism that so easily lends itself to realistic imitation and “literary” narrative in kitsch art, and rather “stress the ineluctable flatness of the support that remained most fundamental in the processes by which pictorial art criticized and defined itself under Modernism” (

Greenberg 1960, p. 87).

Greenberg determined that Pollock was such a modernist artist, writing in his February 1947 review of his work done just before the abstract poured paintings: “As is the case with almost all post-cubist painting of any real originality, it is the tension inherent in the constructed, recreated flatness of the surface that produces the strength of his art” (

Greenberg 1947a, p. 125). In the January 1948 review of the first poured paintings, he speaks of “style, harmony, and the inevitability of [their] logic. The combination of all three of these latter qualities … reminds one of Picasso’s and Braque’s masterpieces of the 1912–1915 phase of cubism” (

Greenberg 1948, p. 202). Yet Kuspit invites us to understand

Autumn Rhythm, created only three years later, as avant-garde art transformed by the artist’s embrace of the public into high-class kitsch!

Kuspit’s invocation of Beaton’s photographs recalls T. J. Clark’s own turn to Beaton’s photographs as the background of his essay on Pollock, “The Unhappy Consciousness”, in his

Farewell to an Idea: Episodes from a History of Modernism. These photographs are said by him to have stirred up his fears about modernism, what he calls “the bad dream of modernism”, that its explorations of an Other to bourgeois experience would simply be co-opted by bourgeois culture. Clark realizes that the photographs “raise the question of Pollock’s paintings’ public life” (

Clark 1998, pp. 305, 306). Kuspit suggests that by embracing the public Pollock betrayed his true self, but his construction of Pollock’s “true self” cannot convince. This calls his account of Pollock’s supposed self-betrayal into question. Like every artist, Pollock sought public recognition. Eventually, he even came to court bourgeois culture, but did he thereby betray his “true self?”

2. What Made Pollock Pollock?

Already in my dissertation “A Jungian Interpretation of Jackson Pollock’s Art through 1946” I challenged the then dominant understanding, indebted to Greenberg, of Pollock as a modernist that still informs Kuspit’s understanding of Pollock’s “true self” (

Langhorne 1977). From that dissertation, I extracted material that I published as an article, “Jackson Pollock’s

Moon Woman Cuts the Circle” (

Langhorne 1979). It was harshly criticized by William Rubin, the director of the Department of Painting and Sculpture at the Museum of Modern Art. In defense of what was then modernist orthodoxy he chose to attack this iconographic exploration in a two-part article in

Art in America in 1979: “Pollock as Jungian Illustrator: The Limits of Psychological Criticism”. Pollock, he insisted, “was before all else a painter”.

1 What was Pollock’s understanding of himself as a painter? Michael Leja has shown, all such ideas are rooted in and circumscribed by the individual’s cultural situation, as it finds expression in “contemporary cultural productions of diverse sorts, popular philosophy, cultural criticism, Hollywood movies, journalistic essays, and other materials” (

Leja 1993, p. 4). He points to the fascination with the primitive and irrational: “One kind of cultural production in particular gave these ideas center stage and treated them comprehensively, a type of popular nonfiction I will call Modern Man literature, since its focus was the nature, mind, and behavior of "Modern Man” (

Leja 1993, p. 7). Leja demonstrates Pollock’s indebtedness to that discourse. He also recognizes that Jungian ideas were very much part of it. However, Leja fails to do justice to the extent Jung and Jungian ideas helped shape Pollock’s understanding of his artistic goal. I am not a Jungian: I cannot accept Jung’s theory of archetypes. However, we must acknowledge that Pollock’s deep interest in Jungian thought—he was in Jungian psychotherapy between 1939 and 1943 and late in his life declared “I’ve been a Jungian for a long time”—pervades not only his early 1940s work, but still, as I shall show, his mature poured paintings, where this interest cannot be divorced from his much broader spiritual concerns (

Pollock 1957). Not that he felt that he had succeeded in communicating these concerns. He suffered from a sense that what he had achieved had not been understood by the public that admired the bold iconoclast, and this has not really changed. Despite the fact that today no American artist, other than perhaps Andy Warhol or Basquiat, can claim a more prominent place in American mass culture, such popularity has little to do with understanding what he was up to. But what was he up to?

To approach that question, let us take a close look at four of Pollock’s abstract poured paintings of 1950, the last of which suffered the ignominious fate of being called “expensive kitsch”:

Lavender Mist:

Number 1,

1950 (

Figure 2),

Number 32,

1950 (

Figure 3),

Number 31,

1950 or

One, as it is known today (

Figure 4),

Autumn Rhythm: Number 30,

1950 (

Figure 5). About the last three paintings, made from one great role of canvas, Kirk Varnedoe wrote: “Along with New Year’s in 1944, and the advent of the poured paintings in 1947, this was one of the defining moments that made Pollock Pollock”.

2 What was Pollock up to when creating what are strikingly different all-over compositions?

Before beginning work on the three larger paintings, Pollock had spent most of June 1950 on

Lavender Mist, a large canvas 7 feet 3 inches x 9 feet 10 inches, an exquisitely articulated and carefully worked, atomized and unified, beige-pink field.

3 A number of writers have noticed the intimation of two sweeping arcs, especially noticeable in the black tones of the one on the left, converging towards the bottom of the central vertical axis of the canvas (

Rohn 1987, pp. 65–69;

Carmean 1978, p. 129). The convergence weights the composition; the outward springing arcs open it up in a centrifugal motion. Roughly vertical streaks of black throws of paint move into and beyond the field, a stretching amplified by the height of the canvas. But this height is then bound by the careful imprint of his hands, repeated, gently marking the upper left corner of the canvas and also rotating around its upper right corner. Opposed impulses, left-right, up-down, are brought into exquisite equilibrium in the all-over shimmering field that elicited the title of

Lavender Mist from Clement Greenberg.

4

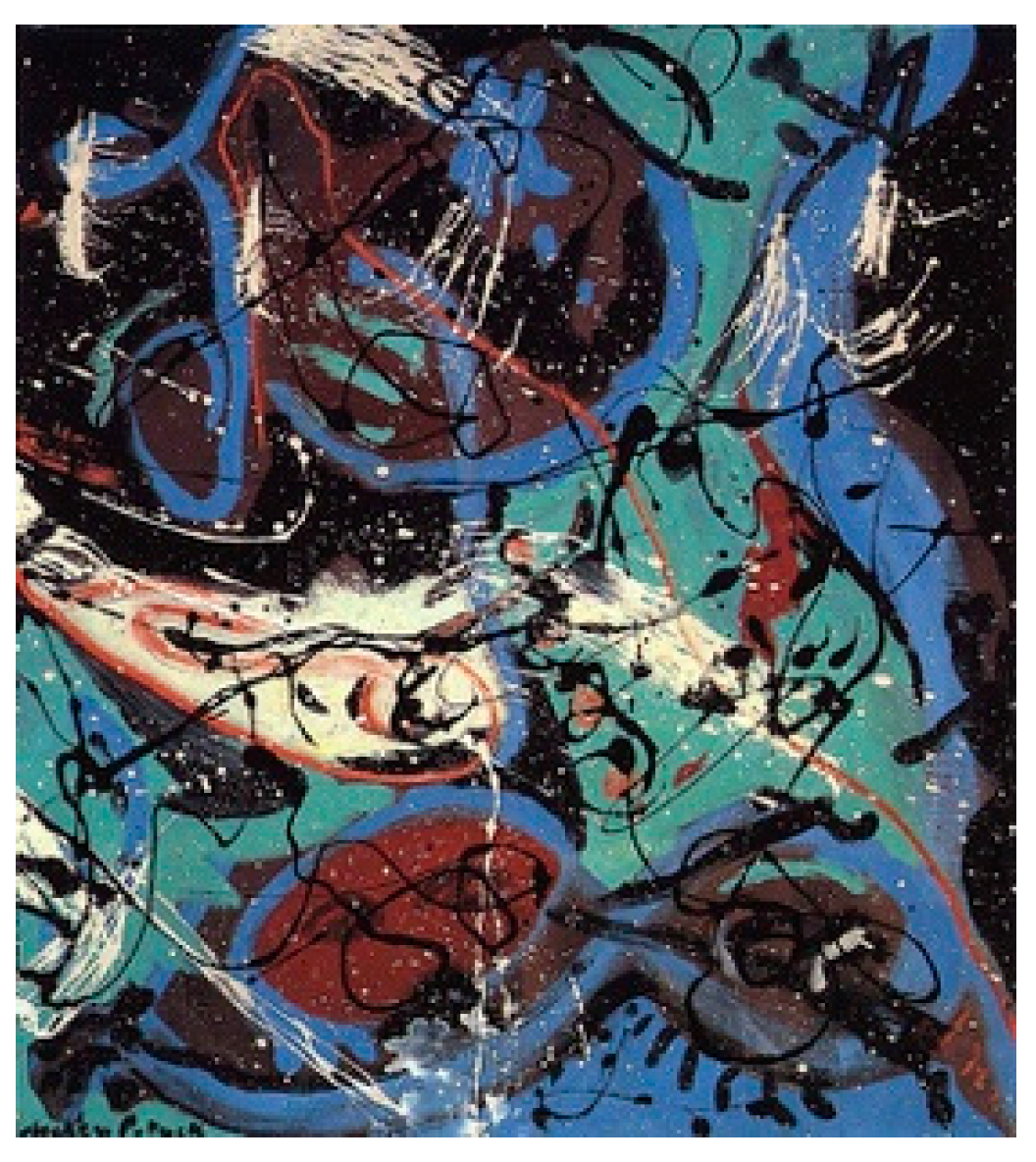

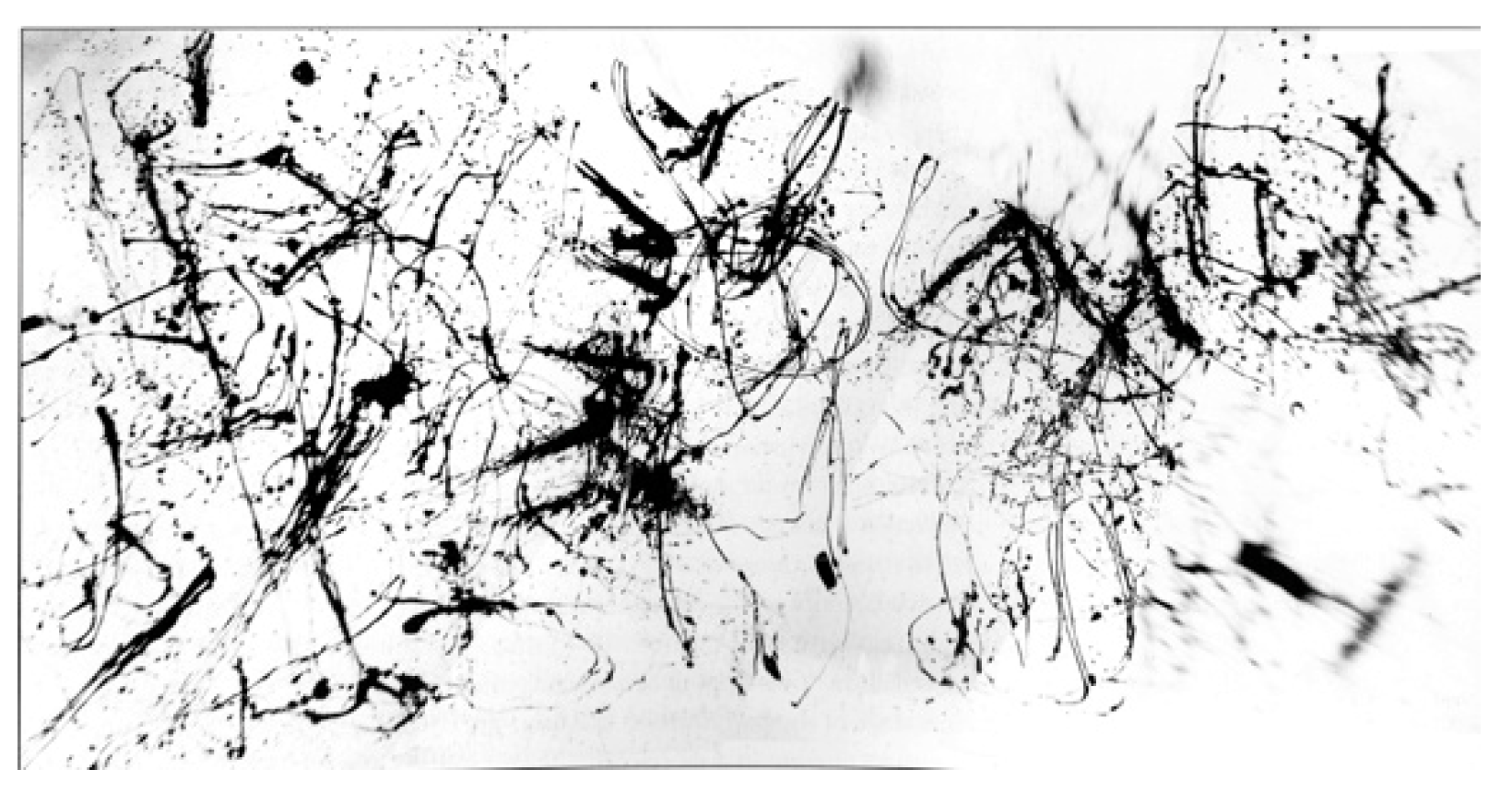

Figure 3.

Jackson Pollock, Number 32, 1950, 1950, enamel on canvas, 106 × 180 in. (269.2 × 457.2 cm). Kunstsammlung Nordrhein-Westfalen, Dusseldorf. © 2022 The Pollock-Krasner Foundation/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York.

Figure 3.

Jackson Pollock, Number 32, 1950, 1950, enamel on canvas, 106 × 180 in. (269.2 × 457.2 cm). Kunstsammlung Nordrhein-Westfalen, Dusseldorf. © 2022 The Pollock-Krasner Foundation/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York.

Pollock turned next to the great roll. Rudolph Burckhardt, who photographed Pollock miming the act of painting

Number 32,

1950 after it was completed, recalls that it was finished in one session (

Carmean 1978, p. 135). The unity of

Lavender Mist that took Pollock most of June to create is now undone in one fell swoop. Moving from the 7 feet 3 inches height of

Lavender Mist to the 8 feet 10 inches height of

Number 32,

1950 sets the scale in relation to the body at a sublime pitch, as does the extended horizontality, moving from 9 feet 10 inches to 15 feet. The building up of a fabric of black throws of paint embedded in complex effects of pinkish beiges is simplified to throws of thinned black enamel paint soaking directly into the vast surface of the unprimed canvas, generating the energy of a cosmic windstorm. Its whirling turbulence prevents what might invite thoughts of figuration or even angular letters of some unknown script from forming.

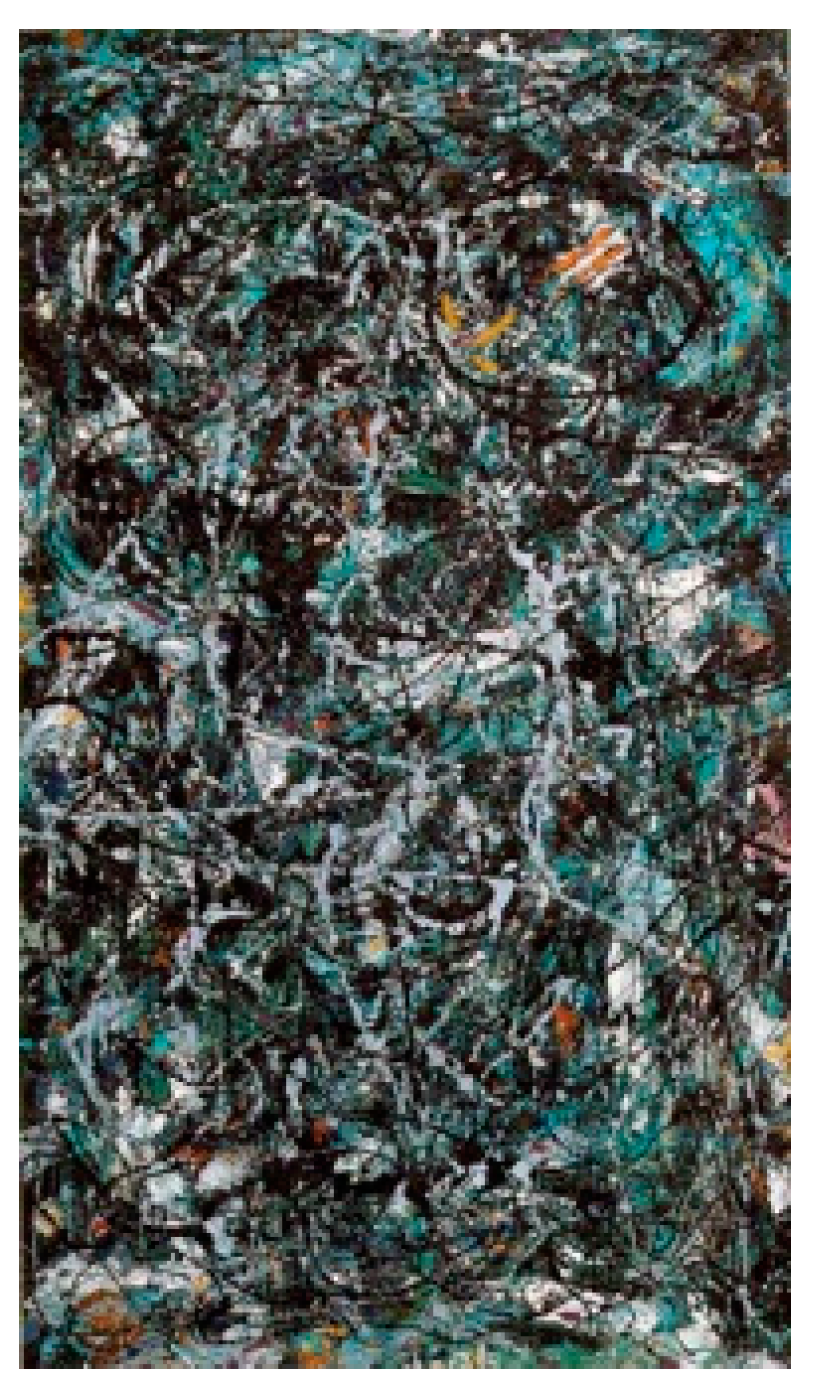

Figure 4.

Jackson Pollock, One: Number 31, 1950, 1950, oil and enamel on canvas, 106 × 209 in. (269.5 × 530.8 cm). The Museum of Modern Art, New York. Sidney and Harriet Janis Collection Fund (by exchange). © 2022 The Pollock-Krasner Foundation/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York.

Figure 4.

Jackson Pollock, One: Number 31, 1950, 1950, oil and enamel on canvas, 106 × 209 in. (269.5 × 530.8 cm). The Museum of Modern Art, New York. Sidney and Harriet Janis Collection Fund (by exchange). © 2022 The Pollock-Krasner Foundation/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York.

Pepe Karmel points out that, as revealed in the filming of Pollock painting later that fall, Pollock began some of the large canvases of 1950 with suggestions of linear figuration that he then totally obscured (

Karmel 1998, p. 111;

Karmel 1999, p. 92). However, in the immediately following work,

One, the viewer is not even tempted to look for such hidden elements, as the material of paint is so endlessly differentiated, whether thrown, spun, spotted, or puddled, that one is struck immediately by the density and cohesion of the all-over field. The relatively unbound energies of

Number 32,

1950, which hung on the studio wall as Pollock worked on

One, coalesce here into a rectangular composition that pulls in on all four sides from the framing edges, slightly weighted with an increased density of interweaving across the bottom.

5 The lack of orientation in the first, which may account for its being published upside down in the Pompidou catalog, gives way to a decided up and down in the second. We begin to recognize a rhythmic underpinning: three-quarters the way up the left-hand edge of the canvas an elegant wedge made by two long black throws thrusts right, initiating a sequence of sloping diagonals that zig-zags to a dramatic encounter of white and black in the center, an instance of what Carmean calls “graspable” throws (

Carmean 1978, p. 138): a white throw arcing from the lower left comes to a head to confront, near the central vertical axis of the entire canvas, a large black loop that falls down just to its right. White energies, like electricity, streak further through matter towards the right, through white nodal points, in fine cracks, quieting in the larger halation or breath of white. Once one notes this fine white tracery, one also sees white arcs cascading down, ever smaller, towards the bottom corner of the canvas. However, countering this movement, energies spring upward. At the right edge of the canvas a blue-gray throw, accompanied by two more clearly defined black ones, rises to a point above the center of the right edge, sending yet further impulses upwards. Once tossed up, energies channeled in the large black upward-facing arcs in particular begin to move the eye back across the upper field towards the left. For the first time in his work, Pollock fully integrates a drama along the vertical with a drama played out on the horizontal axis. Thus,

One pushes even beyond the integration achieved in

Lavender Mist.

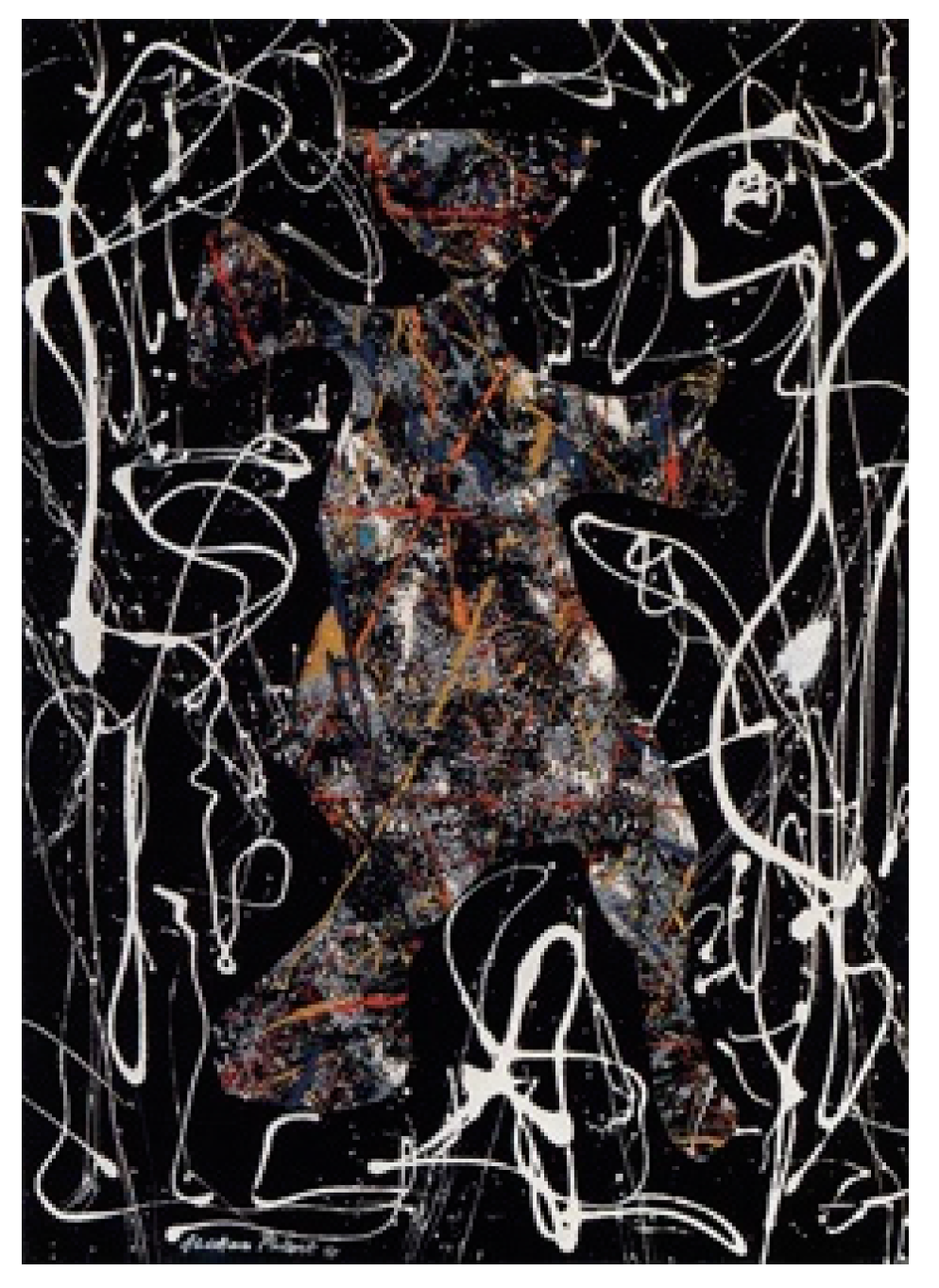

Figure 5.

Jackson Pollock, Autumn Rhythm: Number 32, 1950, 1950, enamel on canvas, 105 × 207 in. (266.7 × 525.8 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York. George A. Hearn Fund, 1957. © 2022 The Pollock-Krasner Foundation/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York.

Figure 5.

Jackson Pollock, Autumn Rhythm: Number 32, 1950, 1950, enamel on canvas, 105 × 207 in. (266.7 × 525.8 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York. George A. Hearn Fund, 1957. © 2022 The Pollock-Krasner Foundation/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York.

Number 32,

1950, and

One, already cut from the roll, hung at either end of Pollock’s studio when he worked on

Autumn Rhythm. This third painting was created on a canvas sheet that was still attached to the roll (

Carmean 1978, p. 135). After

One, the composition opens up again, not to the maelstrom of

Number 32,

1950, but rather to a measured “dance” (

Clark 1998, p. 342).

Autumn Rhythm shares its palette with

One, lacking only some of the green-grays. However, now the throws, in black, white, and bronze/russet, are distinctly more weighty and hence “graspable”, and the painterly fabric loosened. The slight density of the bottom of the field in

One becomes yet denser in

Autumn Rhythm. This allows the thinner tracery of paint to form a greater presence above, adding to the complexity of balancing in

Autumn Rhythm, between left and right within the frieze composition, up and down, or in and out along the literal three-dimensional space created by layering. An equilibrium is reached on all axes, more evident than in the three earlier canvases. As Carmean comments, “

Autumn Rhythm’s varying voices—light and dark, heavy and light, straight and curved—can be found in other works as well, but never so emphatically stated” (

Carmean 1978, p. 140).

Through the loosened three-dimensionality of the web of

Autumn Rhythm moves a new sense of rhythm and journey. Consider the way, acting as an incoming rhythm, three closely-placed threads of black, three-quarters the way up the left-hand edge, enter to get caught up in the reinforced “splat” of the upper part of the left-hand pole “figure”

6 that sets a black pulse moving in a zig-zag pattern to the right, where, after various adventures, it exits on the right edge as a straight slightly uptilted diagonal. Rohn observes that “Pollock wanted to emphasize the extended horizontal dynamics inherent in

Autumn Rhythm’s proportions. He used the poles [to left and right] to stress outward and upward extension. The less structured center adds dynamically to the sensation of the composition’s being stretched apart”, and I would say, with the exiting mark, as moving on (

Rohn 1987, p. 52).

A number of questions are raised by this look at the abstract forms in the three larger paintings and Lavender Mist. The unity of Lavender Mist gives way to the disruption of Number 32, 1950, followed by the even grander unity of One, which is followed by a loosening that projects a sense of ongoing movement. This pattern suggests a story of some sort, a narrative, a deeper significance. Where are we to find the key to that narrative?

3. The Pursuit of Spirit in Matter

We are given a pointer by the answer Pollock gave in 1953 to the question of who really understood the content of his abstract paintings, “Greenberg?” “No … There’s only one man who really knows what it’s about, John Graham”.

7 No doubt Pollock appreciated and colluded with Greenberg’s celebration of him as perhaps the greatest American artist to which he owed worldwide fame and commercial success. However, such collusion was in bad faith as suggested by the fact that Pollock felt obliged to warn Fritz Bultman, after a conversation with him about mysticism, “Don’t tell Clem any of this”.

8 Pollock knew that his true self was not at all that of an avant-garde artist in the Greenbergian mode, pursuing painting for painting’s sake. He pursued the dangerously self-inflating dream of the artist as seer and healer, as a shaman of sorts.

We can trace the origins of that dream back to his teenage years. In 1928, when the 16-year-old Pollock first arrived at Manual Arts High School in Los Angeles, his art teacher, Frederick John de St. Vrain Schwankovsky, advocated “metaphysical thinking” (

Schwankovsky 1965), even delivering an address to the Los Angeles Board of Education saying the art of the future “will deal with the inner or occult significance of things, and with the world of the imagination. This means, if I am correct, that in future the artist will have to train and develop his imagination and his inner life. He will have to be a seer, and a studious mystic” (

Schwankovsky 1928, p. 12). “Schwannie”, as he was affectionally known to an inner circle of student disciples that included Pollock, Philip Guston (then Goldstein), and Manuel Tolegian, taught his students not only to appreciate Cézanne and Matisse, but introduced them to Eastern religion, Rosicrucianism, Hinduism, Buddhism, yoga, reincarnation, karma, all in order to teach them “how to expand their consciousnesses”, to meet themselves (

O’Connor 1965, p. 17). Kadish was later to call it “a good thing some of the early things that Phil Guston and Jackson did were destroyed”; rather “like some Hare Krishna illustrations”, they were “not the kind of thing one regards as serious art”.

9 In 1928 Schwankovsky joined the Theosophical Society. Theosophy’s claim to capture “the essence of all religion and of absolute truth, a drop of which underlies every creed” (

Jinarajadasa 1931, p. 922) answered his ever-searching eclectic religiosity. Schwankovsky became a personal friend of the Theosophical guru Krishnamurti and invited him out to his studio in Laguna Beach to speak to his students. Tolegian remembers how fascinated Jackson was when listening to Krishnamurti speak. “Schwannie … was a lifelong influence on us with his mysticism and yoga”.

10 Later to Lee Krasner Pollock would often speak of Krishnamurti. She recalls that his mother and family were anti-religious, even “violently anti-religious” and that he felt a loss there as he had strong religious impulses.

11In John Graham, Pollock found a soulmate. Pollock had been close to this eccentric Russian expatriate, painter, connoisseur, theorist, and vocal advocate of modernist painting, in 1940–1943 (

Langhorne 1998, p. 65, n. 5). His answer to the question of who really understood what his art was about suggests that to understand Pollock’s mature abstract work we should look at his early work and into the hermetic lore that characterized Graham’s own art at the time.

What did Graham know that Greenberg did not? Graham’s book of aphorisms

System and Dialectics of Art (1937) had an underground following among his young friends in the New York art world, a group that included Stuart Davis, Gorky, de Kooning, Lee Krasner, David Smith, Mark Rothko, Adolph Gottlieb, and also Pollock. There Graham pronounced abstract painting “the highest and most difficult form of painting” (

Graham 1971, p. 106). In the article “Picasso and Primitive Art” (

Graham 1937), he presented the modernist Picasso of the 1930s as a sophisticated primitive artist, conscious of the unconscious, exploring metamorphic form. We know that Pollock admired that article.

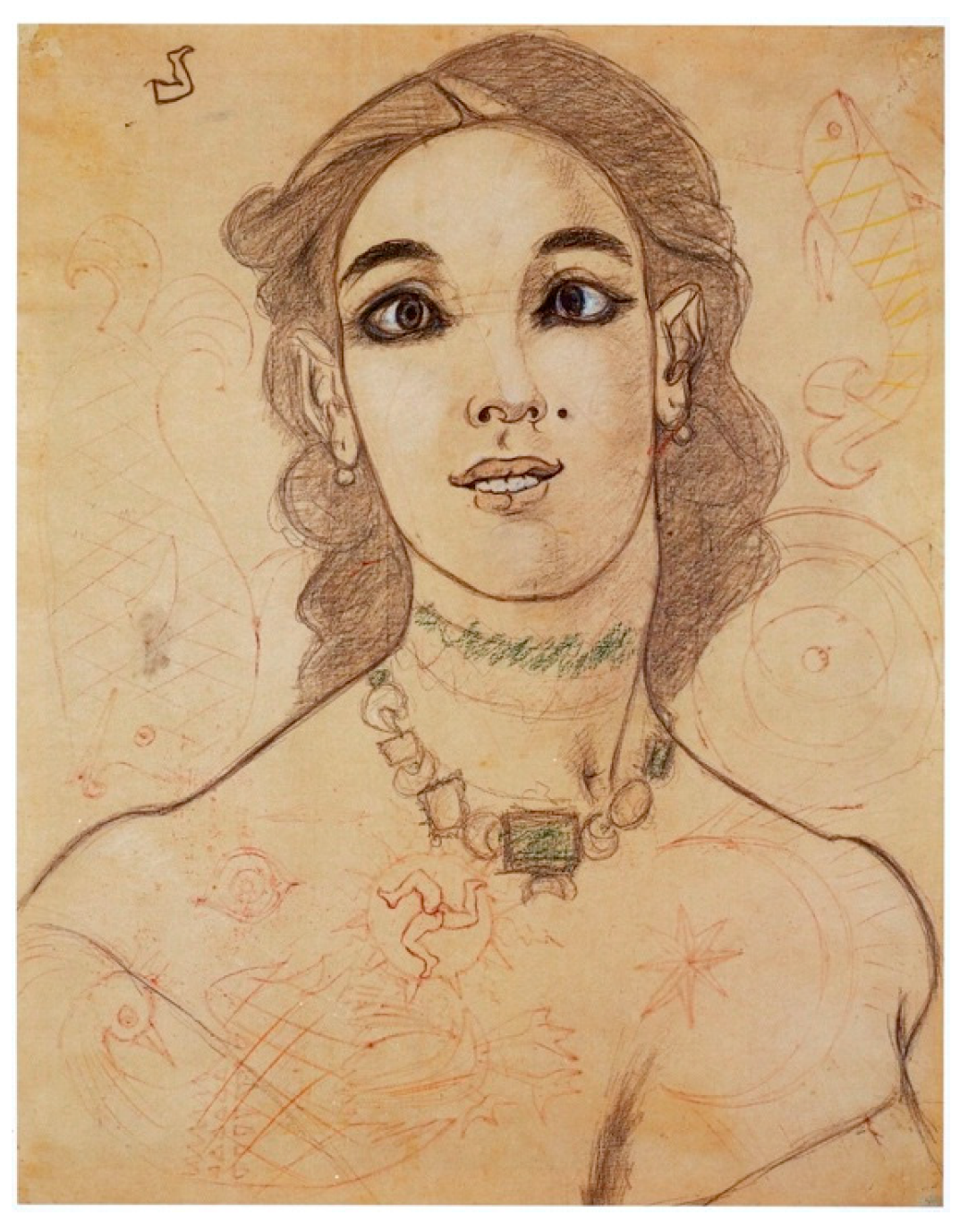

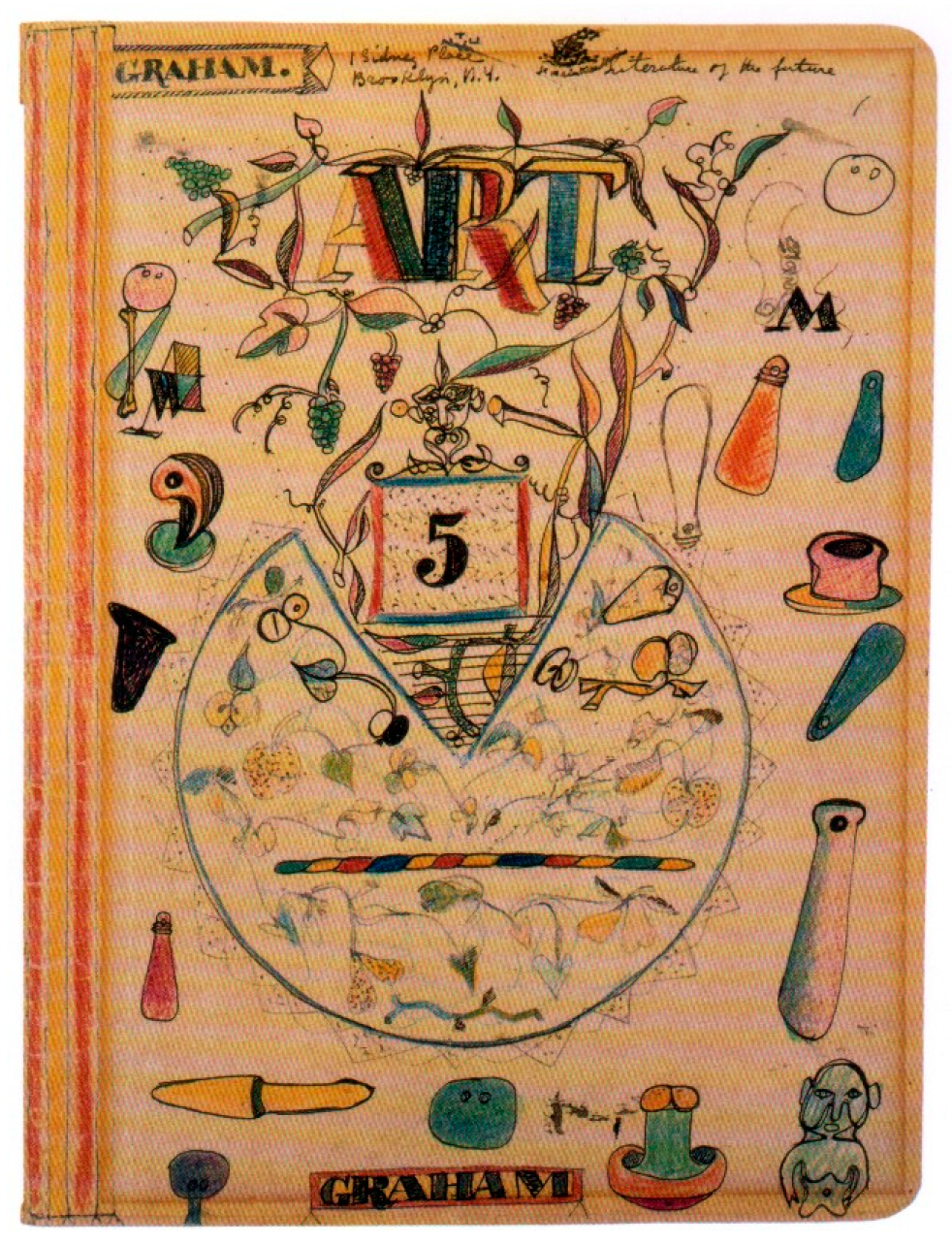

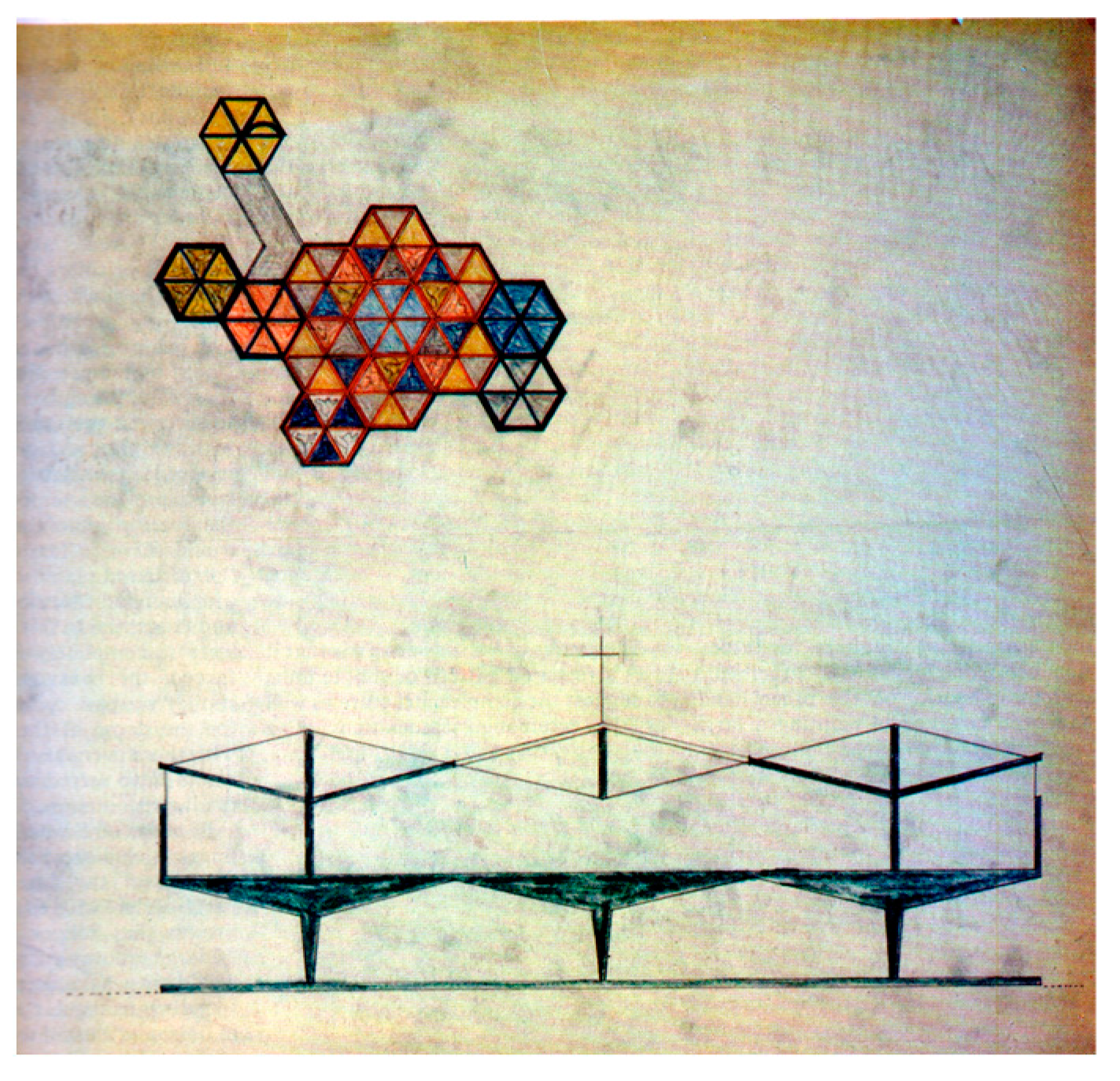

12 However, by 1940, Graham had turned to esoteric hermetic ideas, as shown by a drawing

Universe (Literature of the Future) c. 1940 (

Figure 6).

There he diagrams his understanding of “art”, writ large, using the “philosophical geometry” of alchemy: a circle penetrated by a downward pointing triangle, signifying the interpenetration of spirit and matter.

13 The goal of the Great Work in the hermetic tradition, tied to the mythical Hermes Trismegistus and resuscitated in Symbolist and then Surrealist Art, is the realization of spirit in matter, figured in alchemy by the transformation of lead into gold (See

Tuchman 1987;

Peggy Guggenheim Collection and Museum Barberini Potsdam 2022; especially

Atkins 2022, pp. 137–41). Alchemy offered the painter a seductive figure illuminating his or her own work: as matter is transformed and turned into art, the self is to be transformed and spiritualized. At the same time, alchemy’s symbols provided new subject matter, signs referring to self-transformation.

The embrace of hermeticism by quite a number of artists at the time, especially the Surrealists, took the evolution of modern art beyond the austere purity proposed by Greenberg to a whole new level of vitality. Pollock encountered the Surrealists’ fascination with alchemy in the October 1942 exhibition “First Papers of Surrealism” at Whitelaw Reid Mansion in New York. A splendid catalog designed by Marcel Duchamp laid out the stepping stones of Surrealist myth. The page devoted to “La Pierre Philosophale” contained a traditional alchemical image: the emblematic bird flanked to either side by the sun and the crescent moon, standing on the rock of the untransformed

prima materia, surmounted by the circle with rays containing the sign of Mercury, a symbol of the sought for “philosopher’s stone”. The second illustration on the page is a 1942 abstract drawing by Matta, accompanied by André Breton’s description, “A flanc d’abime, construit en pierre philosophale, s’oeuvre le Chateau étoilé”. “On the edge of the abyss, constructed in philosophical stone, opens up the starry Castle”. At this point, Pollock made contact with Matta, whose circle he briefly joined in October through the winter of 1942–1943 to explore psychic automatism, specifically through abstract painting, to discover what they excitedly talked of: “new images of man” (

Kozloff 1965, p. 2). The need for the creation of new images of man seemed urgent given the way the world was then tearing itself apart.

4. John Graham

Ever since early 1939, when Picasso’s

Guernica with its horse and bull imagery and related drawings was displayed at the Valentine Gallery, Pollock felt challenged by the Spaniard’s art and fame.

14 It was to evolve into a lifelong agon. John Graham helped Pollock find his own way. Unlike the Surrealists who, while they admired Picasso, did not engage with his art, Graham applied his knowledge of alchemy to challenge Picasso’s modernist art. In 1942, Graham was 55, serving, as Pollock’s friend Reuben Kadish observed, as a guru to the 30-year-old Pollock.

15 The focus was Picasso’s

Girl before a Mirror (

Figure 7), which had been illustrated in the 1937 article and was hanging in the Museum of Modern Art since 1938, to which both men made responses.

Figure 7.

Pablo Picasso, Girl before a Mirror, Boisgeloup, March 1932, oil on canvas, 64 × 51 1/4 in. (162.3 × 130.2 cm). Collection Museum of Modern Art. New York. Gift of Mrs. Simon Guggenheim. © 2022 Estate of Pablo Picasso/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York.

Figure 7.

Pablo Picasso, Girl before a Mirror, Boisgeloup, March 1932, oil on canvas, 64 × 51 1/4 in. (162.3 × 130.2 cm). Collection Museum of Modern Art. New York. Gift of Mrs. Simon Guggenheim. © 2022 Estate of Pablo Picasso/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York.

Figure 8.

John Graham, Untitled (Artist Sweating Blood), ca. 1942–1943, oil on canvas, 29 3/4 × 23 1/2 in. (75.56 × 59.69 cm). Present location unknown.

Figure 8.

John Graham, Untitled (Artist Sweating Blood), ca. 1942–1943, oil on canvas, 29 3/4 × 23 1/2 in. (75.56 × 59.69 cm). Present location unknown.

Graham’s

Untitled (Artist Sweating Blood) c. 1942–1943 (

Figure 8) replicates the division of Picasso, a figure on the left facing a mirror on the right. However, instead of Picasso’s classic beauty seeing in her reflection the mysteries of sexuality, death, and life, Graham creates an explicitly hermetic image. He gives the contemplating figure, over which he inscribed Russian letters meaning “wise ones” or “sages”, a striking eye surrounded by a downward pointing triangle. This eye recalls the hermetic geometry that symbolized his understanding of art in

Universe (Literature of the Future) as the interpenetration of spirit and matter, here reflected in the mirror-canvas of his art: a phallus hovers over the feminine vase. Graham defines the goal of art as the interpenetration of opposites, here projected in explicitly sexual terms. In alchemy, sexual union is a central metaphor for the merging of opposites leading to the creation of the philosopher’s stone that frequently found its way into Surrealist art (

Atkins 2022, pp. 137, 139–40).

Figure 9.

Jackson Pollock, The Moon Woman, 1942, oil on canvas, 69 × 43 in. (175.2 × 109.3 cm). Peggy Guggenheim Collection, Venice (The Solomon R. Guggenheim Foundation). © 2022 The Pollock-Krasner Foundation/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York.

Figure 9.

Jackson Pollock, The Moon Woman, 1942, oil on canvas, 69 × 43 in. (175.2 × 109.3 cm). Peggy Guggenheim Collection, Venice (The Solomon R. Guggenheim Foundation). © 2022 The Pollock-Krasner Foundation/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York.

In his 1942 variation on

Girl Before a Mirror, Pollock also presents the contemplating figure, the moon woman as he calls her in the title (

Figure 9), with a striking eye, and with a dual profile and frontal head as in Picasso’s painting. However, Pollock’s dual-headed woman looks with her agitated third eye not at a mirror or a canvas, but at a mass of heavily scumbled yellow, white, green, black, pinky-green paint: her effort to “see” (she points to yet a fourth eye) is focused on chaotic material. This yields, upon closer inspection, a flower. Its yellowish stem rests on a sort of shelf; its sunflower-like head is surrounded by yellow and white pigment. This flower bathed in gold hints at an order distinctly “other” than the classical order that still plays a role in Picasso’s art. Is it the flower named in the title of

The Secret of the Golden Flower; A Chinese Book of Life? Dr. Joseph Henderson, Pollock’s Jungian psychotherapist from 1939 to 1940, had shown Pollock the mandalas illustrating this book of Chinese mystical alchemy and Taoist yoga.

16 As Jung explains in the accompanying commentary, the materiality of each individual contains a latent spiritual dimension. The goal is to control the flow of life forces so that the dark material aspect of one’s being transforms itself into the light spiritual aspect, creating a transformed body, the “golden flower” or “diamond-body” (

Jung 1931, pp. 73, 123, 131).

Figure 10.

Frederick John de St. Vrain Schwankovsky, Modern Music, 1920, Oil on canvas, 66 × 51 cm, Laguna Art Museum, Laguna Beach, California.

Figure 10.

Frederick John de St. Vrain Schwankovsky, Modern Music, 1920, Oil on canvas, 66 × 51 cm, Laguna Art Museum, Laguna Beach, California.

In his depiction of his moon woman, Pollock echoes his former teacher Schwankovsky’s painting

Modern Music 1920 (

Figure 10). There, Schwankovsky depicts his wife playing the piano, and on the left a vertical sequence of colors and forms conveying the emotion of the music and its creation, its spirituality announced in the topmost large symbolic flower. This Schwankovsky had “patterned after a yoga diagram used for describing different spiritual planes, or chakras in the body” (

Colburn n.d.). Chakras are the six nodal points along the spine through which life force energy circulates, purifying the lower energies and guiding them upwards as the practitioner strives for self-realization, ultimately achieved in the topmost or 7th chakra, the 1000-petalled lotus. Pollock did not forget Schwankovsky’s conjunction of art and spiritual pursuit, as, like his guru Graham, he sought to challenge the art of Picasso with hermetic wisdom.

Figure 11.

Jackson Pollock, Male and Female, ca. 1942, oil on canvas, 73 1/4 × 49 in. (186.1 × 124.3 cm). Philadelphia Museum of Art. Gift of Mr. and Mrs. H. Gates Lloyd, 1974. © 2022 The Pollock-Krasner Foundation/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York.

Figure 11.

Jackson Pollock, Male and Female, ca. 1942, oil on canvas, 73 1/4 × 49 in. (186.1 × 124.3 cm). Philadelphia Museum of Art. Gift of Mr. and Mrs. H. Gates Lloyd, 1974. © 2022 The Pollock-Krasner Foundation/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York.

While in

Moon Woman Pollock contemplates the potential for self-transformation, he was also contemplating the potential for a new art, evident in

Male and Female 1942 (

Figure 11). The rectangular “canvas”, placed on the right of

Artist Sweating Blood with its sexual imagery, is now placed dramatically in the center, where the diamonds symbolizing the union of these opposites stand out against the thick white paint of the central panel.

The title reminds us that Pollock had just met Lee Krasner, his future wife, in late 1941. Placed to either side of the central diamonds, the figures who are to effect this union are characterized by ambiguous androgyny. Both personages have female torsos, one red, the other pink. However, a driving male desire is evident in the white phallic column spewing automatist paint just to the left of the personage with the red torso. On the extreme right side of the canvas, passages of automatist paint cascade downward to the right of the large white lunar head. Even more scumbling is found just below the pink torso’s yellow pubic triangle, located in the black area below the central white panel. This circulation of erotic energy mounts upwards to a bold conclusion in the diamond symbols, the bottom diamond moving onto the white panel, the top one carefully abutting its top edge. Is Pollock thinking of his hopes for his relationship with Lee Krasner? Of an emerging sense of himself, a relationship between his anima, the unconscious female component in every man’s psyche, and his masculine spiritual animus—his friend Peter Busa remembers Pollock “was thinking of incorporating that in a painting”.

17 Or is he thinking of a path to a new art? Probably all of the above.

The central white rectangle reads as a proto-canvas of his future art, here only symbolized by diamonds. That the pink female torso impinges on the central rectangle with its thick white paint suggests that for Pollock untransformed paint itself has a female charge. The circulation of automatist energies around the edges of the canvas and upward towards the center suggests the process by which the thick material of paint will be transformed into diamonds, spirit-matter. How to achieve this remained a mystery in 1942. The goal, symbolized by the diamonds, is, however, clear: the hermetic one of spiritualizing matter, a goal that for him, as for Graham, intertwined with a dream of sexual fulfillment and personal growth, obscuring the distance that separates art from life.

John Graham shows him the next step. In 1943, he began to deny Picasso, even erasing his name from

System and Dialectics of Art. He still believed in the artist as a visionary and diviner, but no longer convinced that the wisdom he sought could be brought forth through the evolution of form, he turned to symbolic images as a “secret, sacred language” (

Graham 1961, p. 47).

Figure 12.

John Graham, Study for Two Sisters, ca. 1943, pencil and charcoal on paper, 24 × 18 3/4 in. Present location unknown.

Figure 12.

John Graham, Study for Two Sisters, ca. 1943, pencil and charcoal on paper, 24 × 18 3/4 in. Present location unknown.

The woman in

Study for Two Sisters c. 1943 (

Figure 12) stares forward with striking crossed eyes and the suggestion of a wound on her neck just above her necklace. That she signifies the fusion of opposites, of body and spirit, is indicated by, among other symbols, the star and crescent moon on her left shoulder and on her right shoulder a lone eye that elsewhere Graham refers to as “the third eye of perception”.

18 How is the artist to actualize this vision of the union of body and spirit? The wound on her neck provides a clue. For Graham ritual sacrifice is the first step. “A ritual death is the true life … the Angle of Deviation, the Angel of Deviation … is escape into life eternal”.

19 Though by this time Graham’s convictions are cloaked in hermetic terminology, the fundamental dialectic in which they are rooted and that was prominent in his

Systems and Dialectics of Art remains: his insistence that in the dialectics of art “both elements of thesis and negating antithesis must be present for revolution” (

Rose 1976, p. 68). In such a work as

Study for Two Sisters the beautiful body and the antithetical wound promise a revolution.

Figure 13.

Jackson Pollock, Moon Woman Cuts the Circle, 1943, oil on canvas, 42 × 40 in. (109.5 × 104.0 cm). Musee National d’Art Moderne, Centre Georges Pompidou, Paris. © 2022 The Pollock-Krasner Foundation/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York.

Figure 13.

Jackson Pollock, Moon Woman Cuts the Circle, 1943, oil on canvas, 42 × 40 in. (109.5 × 104.0 cm). Musee National d’Art Moderne, Centre Georges Pompidou, Paris. © 2022 The Pollock-Krasner Foundation/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York.

Figure 14.

Jackson Pollock, Untitled, CR 704, ca. 1943, ink and touches of red gouache on brown paper, 12 1/2 × 13 in. (31.7 × 33 cm). Gift of the artist to B. H. Friedman. Present location unknown. © 2022 The Pollock-Krasner Foundation/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York. A number following CR refers to the number designated to each of Pollock’s works in O’Connor and Thaw 1978.

Figure 14.

Jackson Pollock, Untitled, CR 704, ca. 1943, ink and touches of red gouache on brown paper, 12 1/2 × 13 in. (31.7 × 33 cm). Gift of the artist to B. H. Friedman. Present location unknown. © 2022 The Pollock-Krasner Foundation/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York. A number following CR refers to the number designated to each of Pollock’s works in O’Connor and Thaw 1978.

A woman, a mutilated eye, and wounding all play a role in Pollock’s

Moon Woman Cuts the Circle in 1943 (

Figure 13). Pollock does not advance his search for a revolution in art with the static imagery of

Study for Two Sisters. As the title tells us, the contemplation of his

Moon Woman in 1942 gives way to action. But where is the moon woman? Where is the circle? A study drawing of c. 1943 (

Figure 14) for

Moon Woman Cuts the Circle, that Pollock gave to his first biographer, shows a female figure holding a knife to her side as she gazes up at the circle of a tail-biting serpent floating above her head, the traditional symbol in alchemy for “the divine and all-creating spirit concealed in matter” (

Jung 1939, p. 227). In Pollock’s drawing, it seems to govern the nature of the female herself. For both Graham and Pollock, the female symbolizes the material sensuous realm that holds within it the promise of spiritual awareness. Pollock would have seen an illustration of this alchemical serpent in Jung’s

The Integration of the Personality, a copy of which Lee Krasner owned and brought with her to Pollock’s apartment when she moved in in 1942.

20 Later in life Krasner remarked: “undoubtedly he found this, that and the other in that book”.

21 Krasner herself later commented on Pollock’s involvement with the moon as being Jungian: Pollock “did a series around the moon. He had a mysterious involvement with it, a Jungian thing”.

22Jung insists on the role of violence in the narrative of alchemical or spiritual transformation. The circular serpent, the alchemical dragon, matter concealing spirit, must be split open, sometimes with a sword, to initiate the differentiation of spirit and body that will eventually lead to their fusion at a higher, more spiritually aware level, an alchemical dialectic if you will.

23 During this period, Pollock often spoke with his friend and fellow artist, Fritz Bultman, who was also in Jungian analysis in 1943, about the extreme violence described in American Indian ritual as necessary to achieving a shamanic “dream-vision”.

24 In

Moon Woman Cuts the Circle, we clearly see a red head with two eyes and a white feathered American Indian headdress in the upper right, a red “crescent arm” swinging upwards in the upper left. This moon woman appears to be seated on white haunches; her white legs extended to the left. As she wields the dagger with her extended red “crescent arm”, she slashes her chin, gouges her forehead to cut out what was her third eye, which we now see connected by a red line to the dagger, and rips at her belly and breasts to release a flow of diamonds outward and upward in a savage caesarean birth.

25Compared to Graham’s emblematic wounding of the female, the action of Pollock’s

Moon Woman Cuts the Circle is violent in the extreme. One might well protest: such ritualistic wounding, no matter what its hermetic character or shamanic precedent, seems misogynist, even obscene, especially in a time of real war and real wounding. Yet it was the very violence of World War II that provided the context for a preoccupation with wounding. Picasso’s

Guernica hung in the same room as

Girl before a Mirror at the Museum of Modern Art, its central theme of the wound challenging all creative spirits to oppose to it a new image of man. As Leja remarks, “By the time of World War II, the quest for a new view of ‘human nature,’ for a new form or human self-description, has become a high priority of middle-class culture in the United States” (

Leja 1993, p. 204).

Leja recognizes the connection between the trauma of the war and Pollock’s fascination with violence, linking it to the popular culture of the day. “The image of man struggling to exert control over the powerful forces within and without him found compelling visual expression in Pollock’s work”. Leja finds analogous expressions in “the jazz musician teetering at the edge of chaos, or the private detective or

film noir protagonist struggling to make order of chaos and to master the forces of evil” (

Leja 1993, p. 283). Leja invites us to understand Pollock’s preoccupation with violence as rooted in the morass he bore within himself, which he countered by turning to modernist abstraction and by asserting artistic control. But for Pollock, as for Graham and Jung, violence is thought to lead to and be only a step towards a more integrated self. As

Moon Woman Cuts the Circle shows, violence here has a positive function.

No longer contemplative as in

Girl before a Mirror, Pollock’s moon woman acts. In having the moon woman cut the circle, Pollock breaks with traditional figuration to an even greater degree than did Picasso in the war-torn scene of

Guernica. The moon woman’s act of self-mutilation is both thematically and formally a rending of the figure. Pollock breaks the unity of the figure to create a new and ambiguous tension of figure and ground, thus breaking the modernist surface of late synthetic cubism in a new way. He purposefully cuts into the red figuration, bringing the blue ground fully into play. This tension he further complicates by an unexpected layering. Closer inspection reveals that the red, which one reads as a figure, is in fact ground; the blue that floods around the canvas and into its center, within the broken red circle, is not background, but is applied by and large over the red in a second layer—effectively creating a second and new ground (See

Mancusi-Ungaro 1999, p. 120). On the top of this ground, he outlines in black the stream of diamonds, as though they have yet to really materialize. The formal result of the action produces an opening of the pictorial surface that Greenberg might have approved as a revolutionary step in the formation of a new modernist painting.

However, Pollock reaches here not just for formal innovation. He struggles towards a new formulation of the creative act, at once a rending and an emergence, a death and a birth, depicted as a violent physical action: the swing of the “crescent arm”, the gashing of the forehead, the release and flow of diamonds. Peter Busa remembers Pollock struggling to describe his work on

Moon Woman Cuts the Circle: “If he had two or three people there, then he could describe his experiences in painting it and the qualities of the many overtones of a painting not being fixed or static, but in the state of becoming. Very much like one thing leading to another” (

Landau 1989, p. 256, n. 32). Important here is the suggestion that painting can capture “a state of becoming”, with shifting meanings. Bultman remembers Pollock’s involvement with

Guernica as “that release of a violent image” (

Bultman 1980).

Moon Woman Cuts the Circle bears witness to such a release, which carries Pollock well beyond Picasso’s understanding of creativity as metamorphosis in

Girl before a Mirror to an understanding of creativity as destructive action leading to birth. In the early 1950s, Pollock described to the young and fascinated writer Patsy Southgate the process of his abstraction, a process that we see begins to occur in

Moon Woman Cuts the Circle: “he took the image, broke it up, and put it together again … He felt that the American contribution he made was much better than anything that had ever been done because it was more personal and soul-searching—romantic and imagistic—and that it was almost sacred to break down the image and re-form it out of your own image. It was a

very creative act”.

26.

Just how self-aware Pollock was as he embarked on this path of death and rebirth is suggested by the words he provided alongside the drawing related to

Moon Woman Cuts the Circle that he gave B. H. Friedman, his first biographer, in effect a “key” to his deepest concerns at this time: “Thick/thin//Chinese/Am. indian//sun/snake/woman/life//effort/reality//total”. “Thick/thin” suggests the formal tension he generates as he opens up the pictorial surface of

Moon Woman Cuts the Circle; “Chinese” the desired flow of energy to higher consciousness, “Am. Indian” the shamanic violence required in the process of death-rebirth; “sun” the male spirit to be released from the tail-biting “snake”, a process involving “woman/life//effort/reality” to achieve a new “total”.

27 In Jung’s

Integration of Personality next to the illustration of the tail-biting serpent the text states that the dragon, “probably the oldest pictured symbol known to us in alchemistic texts”, appears as the tail-eater “accompanied by the legend: … ‘the One, the All’. The alchemists declare again and again that the

opus emerges from one thing and leads back again to the One; it is thus in a certain sense a circle like a dragon that bites itself in the tail. For this reason, the work is often called

circulare, circular, or else the

rota, the wheel” (

Jung 1939, p. 227). Alchemy offered Pollock a narrative about a cyclical process leading to both the renewal of self and the renewal of art.

28Pollock shared with Bultman his conviction that “the dream vision” with its release of “subjective matter”, whatever that flow of diamonds might turn out to be, was the way to definitively break with the world of representation (

Bultman 1980). Graham, as in

Study for Two Sisters, remains caught in the world of representation, indeed classical representation. Pollock, on the other hand, in cutting the circle is launched on a quest that will propel him, both personally and pictorially, to a culmination in the great abstract paintings of 1950:

Number 32,

1950,

One, and

Autumn Rhythm.

29 5. Pouring

The erotic character, so evident in

Male and Female 1942, of Pollock’s evolving quest between 1943 and 1946 is suggested even by his titles:

Male and Female in Search of a Symbol 1943,

Two 1945,

Development of the Foetus (The Child Proceeds) 1946; death-like experience to propel further innovation by titles such as

She-Wolf 1943,

Night Sounds 1944,

Totem Lesson II 1945. However, the progress Pollock had made in these years can most easily be seen by comparing

Male and Female 1942 with

Shimmering Substance 1946 (

Figure 15), one of the

Sounds in the Grass series created shortly after Pollock and Krasner married and moved from New York City to the country in Springs, Long Island. In

Shimmering Substance, the full scope of symbolic meanings encoded in

Male and Female is expressed in an abstract and all-over automatist field of animated paint.

This achievement of an all-over “recreated flatness” was to be hailed by Greenberg in a February 1947 review as the hallmark of the new post-cubist art. Figurative symbols have vanished, and the promise of the central white panel in Male and Female is realized now throughout the animated field: Shimmering Substance. With colored lines in fluid looping rhythms, Pollock generates relationship and elision between opposites: black-white, yellow-red-blue, up and down, left-right, in-out, thick-thin. The suggestion of a single glowing yellowish circle is especially tantalizing as it provides a new emphatic unitary structure in Pollock’s art. The circle of the uroboric serpent that hovered above the head of the moon woman in CR 704 has here been reconstituted as the glowing circle of a fully realized spirit-matter, a realization in paint of the symbolic diamond. In Shimmering Substance, Pollock has achieved a “total”. However, he had not yet taken the step of making the pouring of paint his primary means of creating a painting.

Figure 16.

Jackson Pollock, Composition with Pouring II, 1943, oil and enamel paint on canvas, 25 × 22 1/8 in. (63.9 × 56.3 cm). Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, D.C. Gift of Joseph H. Hirshhorn, 1966. © 2022 The Pollock-Krasner Foundation/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York.

Figure 16.

Jackson Pollock, Composition with Pouring II, 1943, oil and enamel paint on canvas, 25 × 22 1/8 in. (63.9 × 56.3 cm). Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, D.C. Gift of Joseph H. Hirshhorn, 1966. © 2022 The Pollock-Krasner Foundation/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York.

Pollock had experimented with pouring already in 1943. We know from

Male and Female that paint has for Pollock an erotic charge. In

Composition with Pouring II (1943) (

Figure 16), this becomes almost embarrassingly explicit: a white phallus outlined in red is depicted moving towards the lower center of the canvas and transected eye beyond, the ejaculatory triumph of this phallus marked, amid other black poured lines, with a passage of poured white paint. At the same time, we are struck by the seemingly abstract animated materiality of this experimental work, by what Greenberg would call “recreated flatness”. Curving figurative elements, barely recognizable, undulate and even seem to flow over the two-dimensional surface, as the poured colored lines further activate, mingle with, and generate a layered materiality of the surface. Through the technique of pouring paint, Pollock begins to use the literal spatial dimension of layering. Descent generates the beginning of an ascent, the building up of layers from below to above. In the play of opposites Pollock catches the scent of endless transformative possibilities: what is spiritual partakes of the instinctual, and vice versa. Male mingles with female. Matter in these early poured paintings is not simply mute material; matter means.

In 1943, Pollock created three such paintings, one of which he gave as a wedding present to his close friend Herbert Matter and his wife, an accomplished painter, Mercedes.

30 Matter, a Swiss photographer and graphic designer, with whom he had become close friends in late 1941 (

Landau 2007, p. 46, n. 41), was fascinated with movement, installing an exhibition of stroboscopic photographs at the Museum of Modern Art,

Action Photography, in 1943. That year, he also exhibited his own photographic experiments visualizing the flow of energy in a solo show at the Pierre Matisse Gallery. He photographed, for example, the mingling of fluid materials, as ink was dripped into glycerine (

Figure 17), which bears comparison with Pollock’s

Composition with Pouring II (1943) (See juxtaposition in

Landau 2007, p. 29). Matter also exhibited

Electrical Discharges, visualizations of the flow of electricity between two poles, to which in his personal papers he ascribed mental states.

31 A convinced vitalist, Matter believed that a life force was immanent in all matter and an artist’s challenge was to release it and activate our intuitive understanding of all life’s interconnectedness (

Katz 2007, p. 63). The two friends shared a belief in the spiritual dimension of matter.

Their 1943 experiments with the flow of energy within matter provided Pollock in 1947 with a ready tool to advance his art. Seeking to extend the sense of “total” arrived at in

Shimmering Substance, he embraced the technique of pouring. With his underlying sense of structure, Pollock was able to start a canvas somewhat automatically. In his 1947 description of the new technique of pouring paint onto a canvas placed on the floor, he stated: “When I am

in my painting, I’m not aware of what I’m doing. It is only after a sort of ‘get acquainted’ period that I see what I have been about. I have no fears about making changes, destroying the image, etc., because the painting has a life of its own. I try to let it come through. It is only when I lose contact with the painting that the result is a mess. Otherwise, there is pure harmony, an easy give and take, and the painting comes out well”. Creativity is tied to responsiveness. In a draft for this statement, he declared “the source of my art is the unconscious” (

Pollock 1947–1948, p. 241). The process of pouring paint allowed him to move from an initial unconscious automatism towards “pure harmony”, a harmony of opposites in a resolved composition expressing a new sense of self.

Pollock’s statement that only John Graham understood the content of his poured paintings was made in 1953. Indeed, what he had learned from Graham continued to sustain his artistic journey through 1947–1950: the drive towards eros, the mechanism of death leading to rebirth. I will point to three works to indicate Pollock’s continuing pursuit of erotic union, sometimes using the mechanism of destruction, as he pursues union at ever more integrated levels: Full Fathom Five 1947, Cut-Out Figure 1948, Lavender Mist 1950.

Figure 18.

Jackson Pollock, Full Fathom Five, 1947. Oil on canvas with nails, tacks, buttons, key, coins, cigarettes, matches, etc., 50 7/8 × 30 1/8 in. (129.2 × 76.5 cm). Collection Museum of Modern Art, New York. Gift of Peggy Guggenheim, 1952. © 2022 The Pollock-Krasner Foundation/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York.

Figure 18.

Jackson Pollock, Full Fathom Five, 1947. Oil on canvas with nails, tacks, buttons, key, coins, cigarettes, matches, etc., 50 7/8 × 30 1/8 in. (129.2 × 76.5 cm). Collection Museum of Modern Art, New York. Gift of Peggy Guggenheim, 1952. © 2022 The Pollock-Krasner Foundation/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York.

In

Full Fathom Five 1947 (

Figure 18), its initial impastoed layers are painted with a brush; embedded in the impasto are clusters of nails, a garland of upended thumbtacks, buttons, two keys, cigarettes, matches, etc. Then come the thin poured lines of mostly black and silver paint. While the topmost quick slashes of mustard yellow and orange and white impastoed paint encircled in a ring of black poured paint might suggest a head, what is especially intriguing about Pollock’s process of painting this canvas, as discovered through the conservator’s X-ray photographs made at the time of the Museum of Modern Art’s 1999 Pollock retrospective, is the presence of a rough figure in the first impastoed layer to which Pollock then responded with subsequent layering. One of the keys embedded in the impasto, hardly visible in most reproductions, falls unmistakably right at the crotch of the figure (

Coddington 1999, p. 103). In this detail, we recognize a literal variation of the erotic theme. Here he has decided to bury the triggering image, for he had begun to discover a more abstract way of translating the drama of erotic dialogue into more purely pictorial sensations: either of being drawn down into the encrusted layers of aqua-green and grays or of being released into the more buoyant swirls of poured silver and black.

Figure 19.

Jackson Pollock, Cut-Out Figure, 1948. 78.8 × 57.5 cm. Private Collection, Montreal. © 2022 The Pollock-Krasner Foundation/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York.

Figure 19.

Jackson Pollock, Cut-Out Figure, 1948. 78.8 × 57.5 cm. Private Collection, Montreal. © 2022 The Pollock-Krasner Foundation/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York.

That the mechanism of disruption continues to play a role in Pollock’s pursuit of his quest is vivid in an example from 1948:

Cut-Out Figure (

Figure 19). To make this work, Pollock started with the all-over field of one of his early abstract poured paintings, characterized by an encrusted surface and angular throws of multi-colored paint, presumably a failed work. From the unity of this field, he cut out a large humanoid figure. This figure he then collaged onto the vertical axis of another surface, the black ground of which he articulated with white poured lines, suggesting upright personages flanking it to the left and right. These white poured lines challenge the central figure, which appears to be sexless, with their more instinctual energies, an echo of the similar challenge made in

Male and Female where sexy automatist energies swirled around the as yet untransformed center. That Pollock sets forth the proposed transformation in

Cut-Out Figure with an initial and literal act of cutting recalls the sacrificial act in

Moon Woman Cuts the Circle where the figure of the moon woman was cut open to release the flow of diamonds. Disruption continues to play a role in the ongoing narrative of transformation as Pollock strives for an ever more comprehensive unity.

Both T. J. Clark and Leja discuss

Cut-Out Figure. Clark finds in it an example of the way the abstract has to exclude the figurative. “If there is to be a figure at all in a poured painting, that is to say, it will be one that the act of mark making has excluded. The abstract will displace the figurative, cut it out, put it nowhere—and then given the weightless, placeless homunculus just enough character for it to be someone after all”. Clark sees “no to and fro between the white pours and the stuck-on homunculus” (

Clark 1998, pp. 347–49). As stated above, I see more of a relationship between the cut-out figure and the vaguely figural white pours: an invitation to transform what remains untransformed, a forward-looking pointer.

Leja, too, sees a relationship between the collaged figure and the figural white pours: “in one sense it is immersed or entangled in them, in another it participates in an interaction”. This interaction, to be sure, is said to “be partial at best”, as such “a powerful symbolization of the dialectics of alienation and entrapment, interiority and exteriority, control and uncontrol” (

Leja 1993, p. 300; See also

Leja 2016, pp. 31–35). Missing once again is attention to what I take to be the forward-looking nature of the work.

In

Lavender Mist (see

Figure 2), the balancing of energies on the horizontal, vertical, and diagonal axes and in the layered depth of the field is exquisitely achieved. The tensions present at the beginning of the period of the abstract poured paintings in

Full-Fathom Five are resolved. The animation of the field is no longer the least gendered. “Every move he made on this painting”, the painting conservator Coddington has written, “... every adjustment of prior technique, broke the image into smaller and smaller segments until it was reconstituted as an organic whole” (

Coddington 1999, p. 109). Is this organic whole not the instantiation of the diamond-body, the image of a new self, that Pollock had long sought?

Despite the exquisite beauty of Lavender Mist, was there something dissatisfying about it that would lead Pollock in his next masterwork to the explosive and cosmic windstorm of Number 32, 1950? Perhaps the loving synthesis of opposing forces, of matter and spirit, that he achieved in Lavender Mist, even though he had left behind all imagery, remained too personal: one thinks of those handprints that made Lavender Mist his. The ambivalent accolade of the 1949 Life article, “Jackson Pollock: Is he the greatest living painter in the United States?” demanded an answer. In the summer of 1950, Pollock wanted to prove that he was indeed great, the American answer to Picasso. Here, we first encounter the problematic consequences of the embrace of Pollock’s essentially private and hermetic art by mass visual culture.

6. Meaning

That summer, Pollock told to Tibor de Nagy the story of a young Indian boy “who wanted to be initiated into a famous clan, but he had to do three heroic things before he could become famous”.

32 Pollock applied that story to himself, creating the trilogy, with which this essay began, from a giant roll of canvas, each painting larger, with the exception of

Mural 1943, than any of his earlier works. In the sequence of these paintings, we can now see the by-now-familiar alchemical narrative of destruction-creation. The first step is the wound, a willed sacrifice. What is sacrificed? The perfection of

Lavender Mist. The accomplishment of the organic unity of

Lavender Mist is willfully torn asunder in the cosmic windstorm of

Number 32,

1950 (see

Figure 3) in the hopes for a union of opposites at yet a higher level.

The unity of

Lavender Mist was followed by the even grander unity of

One (see

Figure 4). The scale is larger, the gestures more energetic and more “graspable”, as the throws of paint moving along both the horizontal axis and the vertical axis are integrated more fully. As reported in Robert Goodnough’s article “Pollock Paints a Picture”, which we now know to have been written in response to his observations of Pollock painting

One over the course of three different sessions in late June and early July 1950, Pollock was remarkably forthright.

33 The content of Goodnough and Pollock’s conversations deserves quoting at length.

“At first he [Pollock] is very much alone with a picture, forgetting that there is a world of people and activity outside himself. Gradually he again becomes aware of the outside world and the image he has begun to project is thought of as related to both himself and other people … His work may be thought of as coming from landscape and even the movement of the stars … yet it does not depend on representing these but rather on creating an image as resulting from contemplation of a complex universe at work, as though to make his own world of reality and order. He is involved in the world of art, the area in which man undertakes to express his finest feelings, which, it seems, is best done through love”.

Pollock considered

One one of his most successful works, “an integrated whole … more of an emotional experience from which the physical has been removed, and to this intangible quality we sometimes apply the word ‘spiritual’” (

Goodnough 1951, p. 60). His ambition for the canvas is confirmed in the story of its title. Between 1950 and 1955 the canvas had been simply called

Number 31,

1950. When Ben Heller bought it in 1955, he wanted a meaningful title. Greenberg suggested naming the canvas

Lowering Weather and as Greenberg remembers, Jackson was willing to go along with this, until Ben Heller thought that this was not profound enough. Pressed by Heller to find a really significant title, “Jackson sat around”, according to Greenberg, “squirming, and said ‘just call it ‘one’” (

Greenberg 1968, p. 254). To Heller Pollock explained his proposed title, recalling times in his life when he felt most at one with the world. He mentioned a cross-country trip made as a young man and his summers making large poured paintings (See

Stuckey 2013, p. 34). To his friend Jeffrey Potter, whom he first met around 1949, he asserted: “We’re part of the one, making it whole. That’s enough, being part of something bigger. Let the Salvation Army take over the gods. We’re part of the great all, in our lives and work. Union, that’s us” (

Potter 2000, p. 89).

Male and Female 1942,

Composition with Pouring II c. 1943,

Shimmering Substance 1946,

Lavender Mist,

One are all predicated on Pollock’s desire for a union of opposites to constitute a more integrated self.

Pollock’s appeal to “the one”, “the great all” takes us back to the beginnings of his quest, to that tail-biting serpent that hovered over his moon woman in the study drawing for

Moon Woman Cuts the Circle. In

Integration of the Personality Jung explained that this serpent was as far back as the tenth or eleventh century accompanied by the legend: the One, the All. The alchemical work of transformation itself “emerges from one thing and leads back again to the One”.

34 The original undifferentiated matter of the serpent hovering over the moon woman has now been differentiated, and finally, after the artist’s long labors from 1943 to 1950, been reconstituted as the One. One might see

Shimmering Substance or

Lavender Mist as already the One, but

One is more completely the One and the All.

35.Given this triumphant conclusion to his quest, one wonders: what next? In fairy tales, the consummation of the lover’s quest is often followed by: and they lived happily ever after. Is

Autumn Rhythm (see

Figure 5) to be understood in this way, as the happy dance that follows the successful conclusion of the artist’s quest? With it, Pollock creates a repetition and variation of

One, even closely sharing its palette, but allowing for, in the looser painterly fabric of the canvas, an even more evident balancing of opposites in a stately dance. That this dance still partakes of the erotic energies that have animated Pollock’s art since 1942 becomes evident in the suggestion of imagery underlying the first stages of

Autumn Rhythm that Pepe Karmel has uncovered. A tripartite composition, noted by Carmean, is tracked in the process of its creation by Karmel in photo-composite images created by overlapping the still photos that Hans Namuth shot in his documentation of Pollock painting.

36 Starting on the right-hand third of the canvas (as it was viewed when finished and hung), Pollock moved to the central section where he drew, as Karmel states, a full-length vaguely female figure. Eventually, he moved on to the left portion where he threw a long “pole” stick figure, tilting up and out. Karmel notes the way Pollock amplified the original composition, reinforcing existing forms with additional black lines or “splats”. A series of these splats impinge somewhat aggressively on the central female figure (

Figure 20).

Here, we recognize the underlying erotic imagery of

Composition with Pouring II c. 1943 and of

Full-Fathom Five 1947, proof of the continuing force of Graham’s erotic agenda as internalized and amplified by Pollock. As he continues to build the composition, the reinforcement of splats is particularly evident in the upper part of the left-hand figure in the finished work where the major lines have become thicker and more insistent; in the central section where the effect of the original concentric order is obscured with a succession of horizontal bars in the lower center; in the upper right where among other marks a “lozenge” (a diamond shape?) is reinforced.

37 The pursuit of the diamond body remains an ongoing enterprise.

When Pollock declared in 1953 that only John Graham understood his art, he suggested its hermetic character. His art invites interpretation as the pursuit of a quest supported by a private myth. However, as a convinced Jungian—he reiterated his allegiance to Jung just a few months before his death in 1956, saying: “when you’re painting out of your unconscious, figures are bound to emerge. We’re all of us influenced by Freud, I guess. I’ve been a Jungian for a long time” (

Pollock 1957)—he appropriated Jung’s faith in archetypal imagery and patterns arising from a collective unconscious. But if that appropriation was justified, should Pollock’s art not have been widely understood? However, the public did not understand the poured paintings. Although Pollock asserted in a 1950 interview “Technique is just a means of arriving at a statement”, he also later lamented “they never get the point …”.

38 That year he wondered aloud: “Is Jung the answer?” “Are Jung’s ideas the answer?”

39.

Certainly, Clement Greenberg never got the point. He did praise the works of the summer of 1950 for their “aesthetic unity”, calling the “four or five huge canvases of monumental perfection … the peak of his achievement so far”. He elaborated, Pollock “wanted to control the oscillation between an emphatic physical surface and the suggestion of depth beneath it as lucidly and tensely and evenly as Picasso and Braque had controlled a somewhat similar movement with the open facets and pointillist flecks of color of their 1909–1913 cubist pictures” (

Greenberg 1952, p. 106). Greenberg never did admit the presence of process in these paintings, nor did he recognize their spiritual dimension, a dimension that, when he did recognize it in the art of Adolph Gottlieb, Mark Rothko, Clyfford Still, and Barnett Newman, he dismissed as “half-baked and revivalist” (

Greenberg 1947c, p. 189).

Harold Rosenberg, Greenberg’s and Pollock’s old friend, did “get the point”, but he did not like it. He recognized the role of time, process, and even narrative, as well as the religious in the new American art in the December 1952 article, “The American action painters” (

Rosenberg 1952, p. 23). In his essay, he never specified any of the action painters by name. However, Pollock himself pointed to a half-drunken conversation between himself and Rosenberg on the train between East Hampton and New York as the source for the article’s key ideas (

Greenberg 1962, p. 138). Hearing Pollock speak of his intentions, Rosenberg recognized the artist’s need for a personal myth to motivate the art. Explaining the type of painter who is an action painter as one “reborn”, Rosenberg elaborated: “based on the phenomenon of conversion the new movement is, with the majority of painters, essentially a religious movement. In every case, however, the conversion has been experienced in secular terms. The result has been the creation of private myths”. Here, Rosenberg is on target. Rosenberg’s description of this secularized private mythmaking as self-creation fits Pollock’s art.

40 The act on the canvas “springs from an attempt to resurrect the saving moment in his ‘story’ when the painter first felt himself released from Value—myth of past self-recognition. Or it attempts to initiate a new moment in which the painter will realize his total personality—myth of future self-recognition” (

Rosenberg 1952, p. 48). The liberating moment in

The Moon Woman Cuts the Circle when the moon woman sacrifices the third eye and simultaneously releases diamonds, might well come to mind. The search for the realization of total personality might describe

Lavender Mist.

But Rosenberg brought to his viewing of Pollock’s art expectations shaped by the existential philosophy that he adopted at the end of World War II. What Rosenberg, as a follower of Sartre, could not tolerate was the closure of such searching in the embrace of an absolute.

41 “Art as action rests on the enormous assumption that the artist accepts as real only that which he is in the process of creating … the artist works in a condition of open possibility … To maintain the force to refrain from settling anything, he must exercise in himself a constant No” (

Rosenberg 1952, p. 48). Kuspit’s understanding of the artist’s ‘true self’ is not so very different: “True Self art suggests that the self is in perpetual creative process—and thus always peculiarly in crisis, always uncertain of itself and unstable, always on the problematic move—and as such not a social product—never completely socialized and with that given final form and meaning … In contrast, False Self art suggests that the self is ‘finished,’ that is, a static, unchangeable social product” (

Kuspit 2020). Not that Pollock settled for the public’s perception of his art. The public, he was convinced, had never understood his artistic quest. However, had he not now brought that quest to an end? “We’re part of the one, making it whole. That’s enough, being part of something bigger”. The fact that Pollock had given himself over to the “weak mysticism” of a “cosmic I” in 1950 Rosenberg found unforgivable (

Rosenberg 1952, p. 48). Earlier Pollock appeared to exercise this constant No, pushing from one possibility to the next as he worked his way through the abstract poured paintings of 1947–1949 to

Lavender Mist and beyond. However, had something qualitatively different not happened in Pollock’s art in 1950 that does invite understanding of the three monumental paintings as a kind of homecoming? The myth of destruction–creation encoded in

Moon Woman Cuts the Circle had come to a kind of conclusion in a monumental expression of the One and the All. For Rosenberg, this grand summation smacked of the Absolute, of God. Seeming to aim his judgment against the huge canvases of 1950, he wrote “When a tube of paint is squeezed by the Absolute, the result can only be a Success … The result is an apocalyptic wallpaper” (

Rosenberg 1952, p. 49), an expression of impotent megalomania rather than transformative choice. Kuspit’s description of

Autumn Rhythm, as it appeared in the 1951

Vogue magazine, as wallpaper comes to mind, not even apocalyptic wallpaper, just wallpaper: “expensive kitsch”.

7. Museum and Church

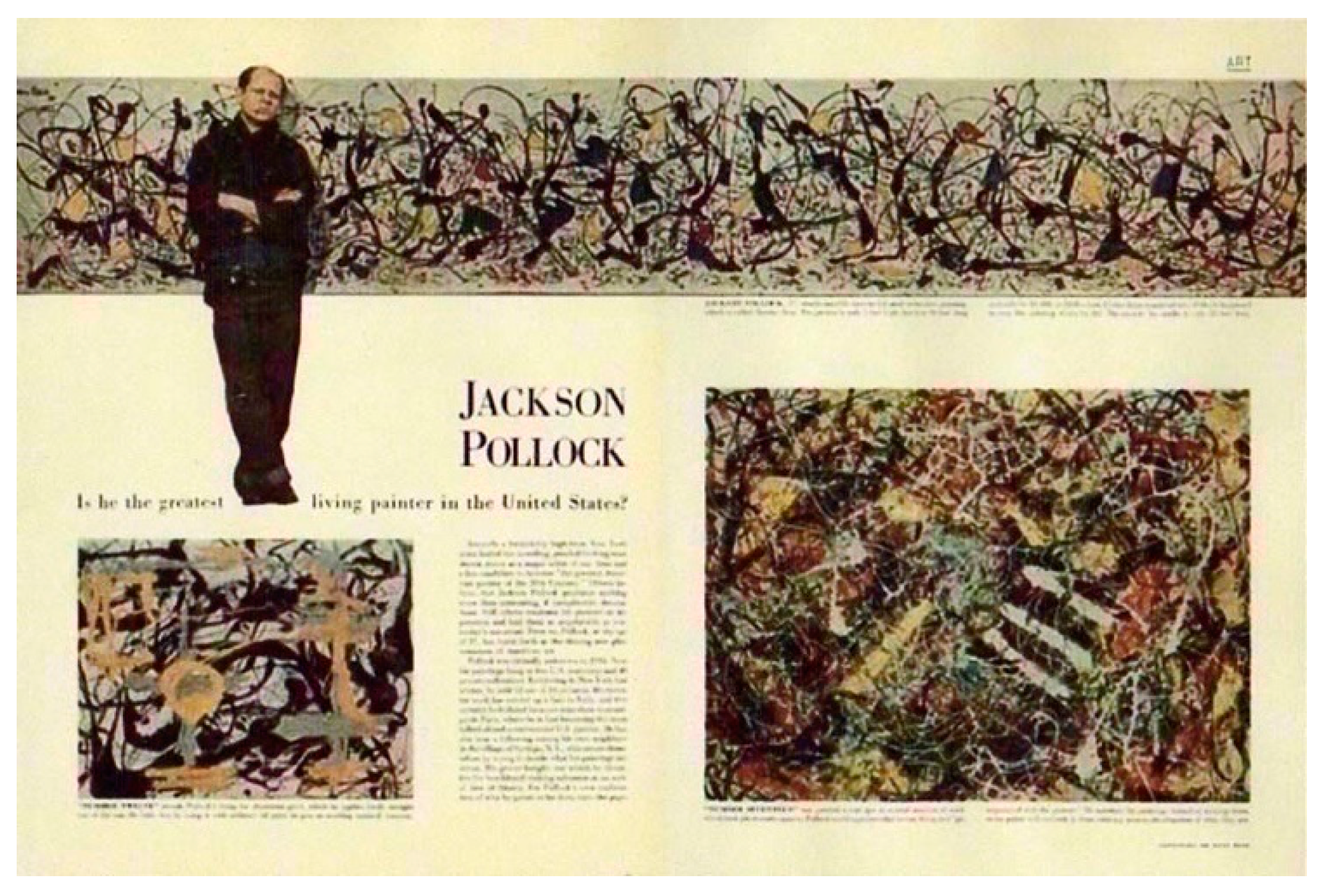

Every artist seeks a public, and he or she wants to be recognized and understood. Pollock was no exception. In 1939 his personal problems accompanied by drinking had led to his Jungian psychotherapy; by the fall of 1948, he had finally managed to go on the wagon and the response to his newly embraced practice of pouring had been encouraging. He now wanted to reach a wider public. So, when a sequence of events, precipitated by Greenberg, led to

Life Magazine asking to do an article on his art in 1949, he and Lee Krasner, aware of the risks, but wanting exposure and needing money, accepted.

42 At the Museum of Modern Art’s October 1948 “Round Table on Modern Art”, organized by the staff of

Life with the goal of publishing the proceedings as part of their policy to educate their readers, Greenberg had praised one of Pollock’s 1947 poured paintings,

Cathedral, as “one of the best paintings recently produced in this country” (

Davenport 1948, p. 62). This led to

Life’s proposal to do an article on Pollock and his art. In the October 1947 issue of the British journal

Horizon, Greenberg had declared: “the most powerful painter in contemporary America and the only one who promises to be a major one … is Jackson Pollock” (

Greenberg 1947b, p. 170). This the title of the

Life article, when it appeared in the 8 August 1949 issue, inverted and turned into a question: “Jackson Pollock: Is he the greatest living painter in the United States?” In acknowledging the range of responses to Pollock’s strange art the text was even-handed: leading with the claim made by “a formidably high-brow New York critic” (Greenberg), to “interesting, if inexplicable, decoration”, to “unpalatable as yesterday’s macaroni”. A few biographical facts and excerpts from his 1947 statement about his pouring technique, interspersed with some mocking words—”drools” (accompanying the staged photographs of Pollock demonstrating his technique), “dribbles”, “scrawls”—completed the two and one/half page spread (

Figure 21) (See

Seiberling 1949).

Donald Kuspit asserts that Pollock through this article willingly “became a public ‘personality’”, thus betraying his true self and beginning a process of turning his art into kitsch. However, as we have seen, Pollock was not concerned to advance the solitary project of art for art’s sake. He thought of himself as an artist–alchemist on a goal-directed spiritual quest. Harold Rosenberg, who knew more of this aspect of Pollock’s project, years later declared that Pollock “preferred to play the laconic cowboy—a disguise that both protected him from unwanted argument and hid his shamanism behind the legendary he-man of the West” (

Rosenberg 1967, p. 131). Here, too, we meet with the suggestion that Pollock presented himself falsely. Rosenberg is referring to the photograph, taken for

Life by Arnold Newman, of Pollock, a “brooding, puzzled looking man”, standing leaning back, arms folded, dressed not in an artist’s smock, but in dungarees, a cigarette dangling from his lips, in front of

Summertime, 1948, then known as

Number 9A,

1948. The by-line reads the painting “sells for

$1800 or

$100 a foot. Critics have wondered why Pollock happened to stop this painting where he did. The answer: his studio is only 22 feet long”.

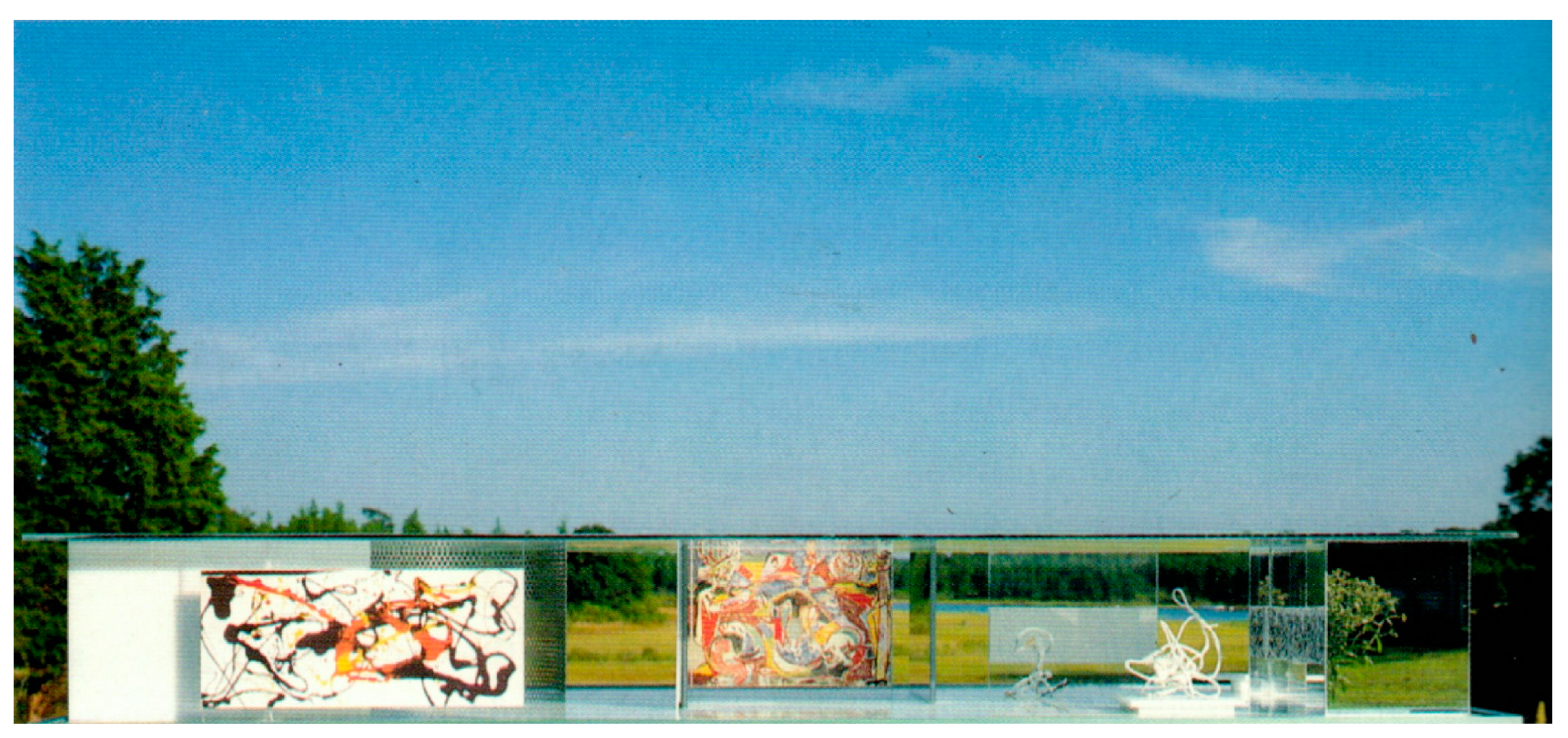

This presentation of

Summertime with its implication of painting as wallpaper sold by the foot contrasts with the radically different public life envisioned for the painting in Peter Blake and Jackson Pollock’s model for an Ideal Museum on which they were working to be shown in the November 1949 exhibition at the Betty Parson’s Gallery (

Figure 22) (See

Langhorne 2011). There, Blake used the photograph of

Summertime taken by

Life and placed it between two vertical mirrors at each end of the canvas, its dancing rhythms extending out to infinity. Had the museum been built and placed as envisioned out in open nature, these rhythms would have dramatized Pollock’s sense of being part of nature. When Lee Krasner first introduced her teacher Hans Hofmann to Pollock in 1942, Hofmann is said to have reacted at once to the paintings, “You do not work from nature”. Pollock’s answer: “I am nature”.

43 Realizing that the statement could be misunderstood—“People think he means he’s God”—Krasner explained: “He means he’s total. He’s undivided. He’s one

with nature, instead of ‘That’s nature over there, and I’m here’” (Krasner, quoted in

Wallach 1981). Here, we have a statement about Pollock’s sense of self, beautifully realized in the Ideal Museum (

Figure 22).

While presenting a misleading image of the artist, the

Life article did bring Pollock public fame and sales. The American he-man and his art caught the imagination of the readers of

Life. He even received fan-mail! (

Naifeh and Smith 1989, p. 596). Challenged by the question posed by the article “Is he the greatest living painter in the United States?”, Pollock created in the summer of 1950,

Number 32,

One and

Autumn Rhythm, gigantic statements of his spiritual convictions that he hoped would resonate with the public. These represent not a betrayal, but the culmination of his personal quest.

One person open to the spiritual dimension of Pollock’s art was Tony Smith, then still an architect, who had become a close friend. When Alfonso Ossorio, an artist and neighbor of the Pollocks, who had worked on a mural for a Catholic chapel in the Philippines, was shocked to discover on his return to East Hampton in the spring of 1950 that there was not a single private Catholic chapel on Long Island (