Predators and Prey: Cosmological Perspectivism in Scythian Animal Style Art

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Background

2.1. Who Were the Scythians?

2.2. What Is Scythian Animal Style?

2.3. Problems of Interpretation

2.4. What Is Cosmological Perspectivism?

2.5. Why Is It Relevant to the Scythians?

3. Predators and Prey

3.1. Wild Contest

3.2. Composite Creatures

3.3. Contest: A Universal Relation

4. Greek Art

4.1. Mesopotamian Influence

4.2. Hellenistic Naturalism

4.3. Hellenistic-Scythian Art

4.4. The Chertomlyk Amphora

4.5. The Tolstaya Mogila Pectoral—The Domestic Perspective

4.6. The Solokha Comb—Horses as People

5. Conclusions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| BM | The British Museum, London |

| MMA | The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York |

| SHM | The State Hermitage Museum, St Petersburg |

| EKRM | East Kazakhstan Regional Museum of Local History, Ust-Kamenogorsk |

| UAM | Ufa Archaeology and Ethnography Museum, Ufa |

| AM | Ashmolean Museum, Oxford |

| 1 | The exhibition brought together artefacts from the Filippovka burial mounds in the southern Urals, excavated between 1986 and 1990 and afterwards becoming part of the collection of the Ufa Archaeological Museum, and some of the finest Scythian artefacts from the State Hermitage Museum in St Petersburg. For the full catalogue, see (Aruz et al. 2000). |

| 2 | For a short overview of the concept of cosmological perspectivism, see (Marina and Cesarino 2014, August 26). |

| 3 | For the fullest outline and exploration of his theory, see (Viveiros de Castro 2012). |

| 4 | For a brilliant recent and comprehensive survey of the Scythians, their history, archaeology, art and culture, see (Cunliffe 2019). |

| 5 | For an introduction to these sources, see (Cunliffe 2019, pp. 44–48). Herodotus brought to his account his own first-hand observations from time he had spent in Olbia, a Greek city on the north coast of the Black Sea, near the Dnieper-Bug estuary, an important contact point between the Greeks and Scythians. For more, see (West 2007). |

| 6 | On the gorodišče finds, see (Cunliffe 2019, p. 22). |

| 7 | A good English language catalogue of Scythian artworks comes from the British Museum’s recent (2017) exhibition of Scythian artefacts from the State Hermitage Museum’s collection, which contains many of the finest examples of Scythian art and material finds (Simpson and Pankova 2017). |

| 8 | For an overview and the history of Peter the Great’s collection, see (Korolkova 2017). |

| 9 | On the casting process, see (Korolkova 2017, pp. 68–69). On the gold working techniques analysed from finds from a recent well documented site, see (Amir and Martinón-Torres 2021). On Achaemenid stylistic influence in the artefacts of Peter’s collection, see (Korolkova 2017, pp. 38–39). |

| 10 | On similarities between items in Peter the Great’s Siberian collection and those in the Oxus Treasure, in the British Museum’s collection, see (Simpson and Pankova 2017, pp. 308–19, in particular cf. figs. 31 and 171). |

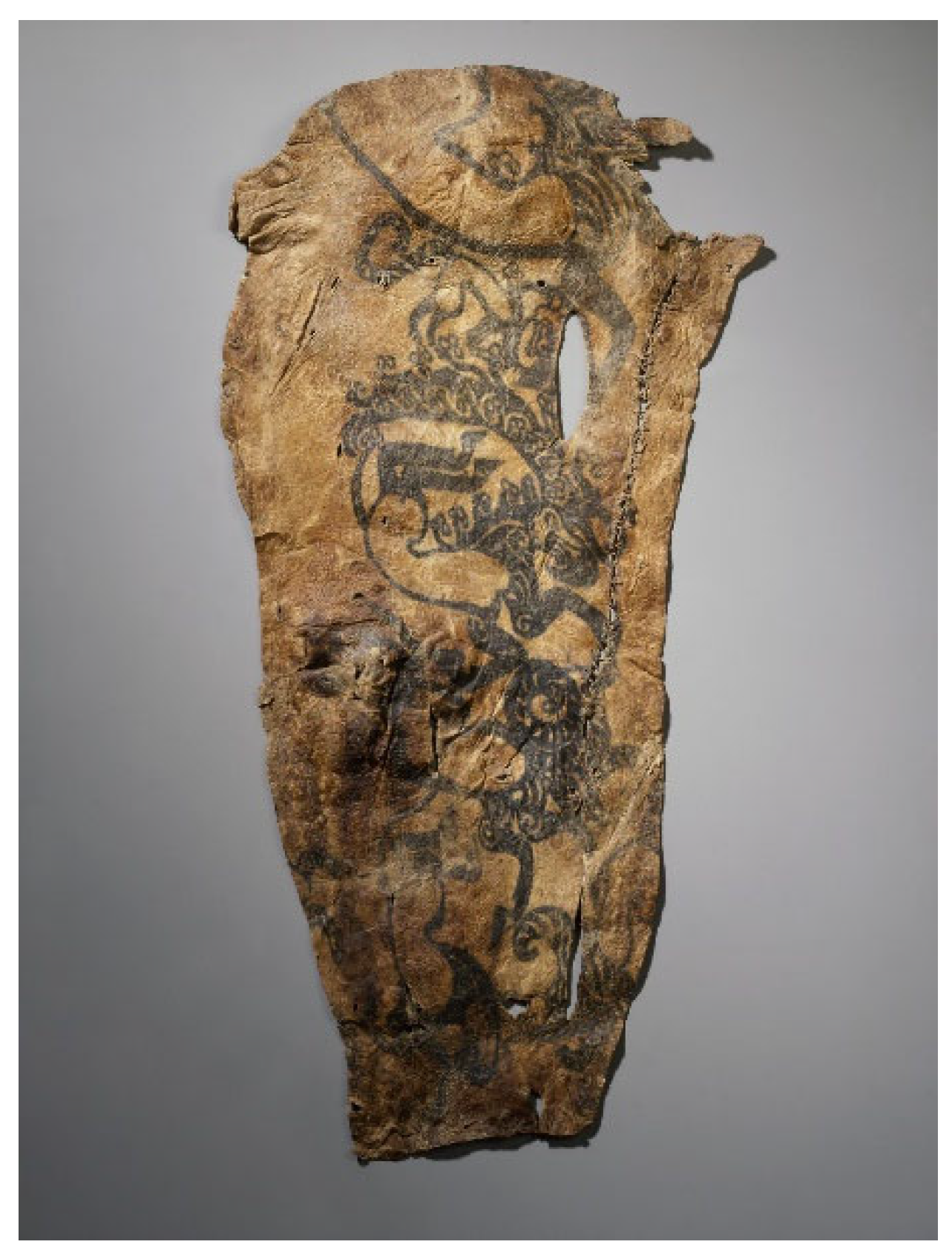

| 11 | On Scythian tattoos, see (Simpson and Pankova 2017, pp. 95–97, 108–9). |

| 12 | According to Herodotus (Hist 4. 131–132), the Achaemenid Persians themselves faced difficulty in interpreting the Scythian language of animal symbols. When, in the early 6th century, under Darius I, they attempted an invasion of the Pontic steppe but found themselves unable to catch the mobile Scythians or their flocks, they were sent a message by the Scythians in the form of a bird, a mouse, a frog and five arrows. The meaning was unclear to Darius and the others with him but was at last correctly interpreted by one of his advisors. Within the meaning of this message the Persians were represented by these prey animals and were being advised to embody them and flee before the predation of the Scythians’ arrows, a symbolic message wholly intune with a perspectivist comsology. To Herodotus’ understanding at least, the Scythians spoke in a language of animals and predation not obviously comprehensible to a sedentary Iranic audience. |

| 13 | A short overview of Viveiros de Castro’s theory of perspectivism is offered in (Marina and Cesarino 2014, August 26). Viveiros de Castro explicitly unpacked his theory in (Viveiros de Castro 2012), but he had already utilisesd and outlined it in earlier work, such as (Viveiros de Castro 1998). |

| 14 | If he is correct, might Euripides be drawing on the Scythians for his model of (to a Greek perspective) chaotic non-Greeks with strange, disconcerting beliefs? |

| 15 | For studies of Mongolia (Pedersen 2001, 2007; Empson 2007) and of the Siberian Yukaghirs (Willerslev 2004, 2007). |

| 16 | Inner Asia vol. 9, pp. 141–345, published in 2007, see (Viveiros de Castro 2007). |

| 17 | For studies on the Turkic peoples of the Altai and the Dukha, Tuvan Turkic reindeer herders of northern Mongolia, see (Broz 2007; Kristensen 2007), for a study on the Tibetans of Yunnan, see (Da Col 2007). |

| 18 | For a work that seeks to approach Amerindian and Central Asian shamanism comparatively, see (Seaman and Day 1994, esp. pp. 4–5). |

| 19 | Cunliffe suggests that Scythian animal art is the ‘manifestation of a deeply rooted shamanistic belief system’ (Cunliffe 2019, pp. 92–93). In support of this interpretation, a number of petroglyphs from Georgievskaya and Boyaru in the Minusinsk valley (near Altai), from where some of the earliest Scythian animal style (known as the Tagar culture) originates, seem to depict shamanic figures with antlered headgear and drums (Cunliffe 2019, p. 93), while several finds in the Altai kurgans, such as the antlered and animal shaped headdresses in Pazyryk kurgans 1 and 2, resemble similar shamanic equipment (Cunliffe 2019, pp. 273–74). Such ‘animal clothing’ is important in helping perspectivist shamans ‘inhabit’ other creatures’ perspectives (Viveiros de Castro 2012, p. 136). It has also been sugegsted that some of Herodotus’ descriptions may describe shamanic practices, such as the Scythians’ divination (Hdt. 4.67, 172), for an outline of these, see (Cunliffe 2019, pp. 272–73). Nevertheless, ‘shamanism’ is a fraught term, and this aspect of Scythian ritual practice is not well established and would benefit from further investigation. |

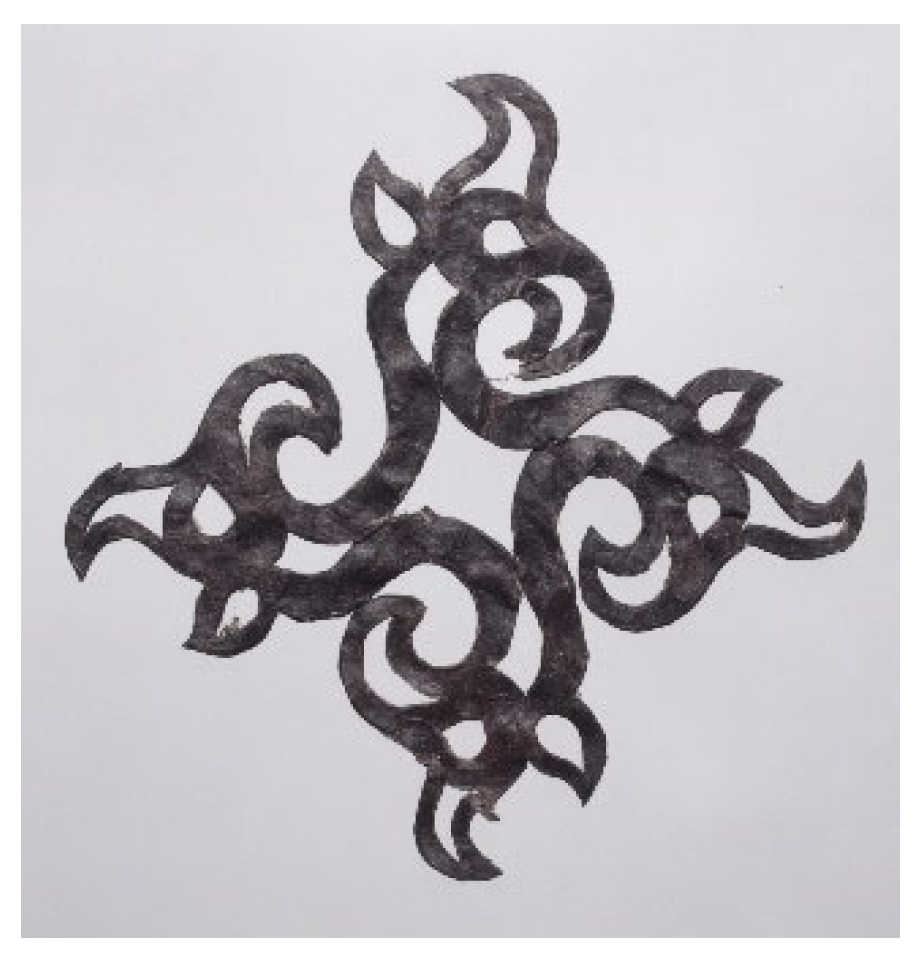

| 20 | On this repeating motif, see (Cunliffe 2019, p. 284). |

| 21 | On this motif, see (Cunliffe 2019, pp. 284–85) On these Shilitki finds, see (Aruz et al. 2000, pp. 172–73; Simpson and Pankova 2017, p. 147; Samashev et al. 2021, p. 33). |

| 22 | For the historical range of the Eurasian moose, see (Heptner et al. 1988, pp. 314–24). |

| 23 | For the historical range of the Persian leopard, see (Heptner and Sludskii 1992, pp. 212–16). |

| 24 | For the historical range of the Caspian tiger, see (Heptner and Sludskii 1992, pp. 108–21). |

| 25 | Golden eagles do sometimes hunt and catch small deer and mountain goats and are still used for hunting by peoples in the Kazakh steppe and Altai mountains. For more on the depiction of fantastical eagle predation in Figure 10, see (Simpson and Pankova 2017, p. 308). |

| 26 | On the historical scale of the Mongolian white-tailed gazelle’s migration, see (Squires 2012, pp. 359–61). |

| 27 | For more on this vessel (UAM inv. no. 831/7, 9, 10a,b), see (Aruz et al. 2000, pp. 95–98). |

| 28 | The tattoos on the right arm of the female burial in Pazyryk kurgan 5 depict tigers and snow leopards predating deer and moose. See (Simpson and Pankova 2017, p. 97). |

| 29 | For more on this particular artefact, see (Simpson and Pankova 2017, p. 243). For more on the horse burials and costumes of Pazyryk kurgan 1, see (Argent 2010). For an overview of Pazyryk kurgan 1, see (Cunliffe 2019, pp. 18–19). |

| 30 | On the original colouring of the saddle cover, see (Simpson and Pankova 2017, p. 243). |

| 31 | The notorious Dzut, which describes a number of extreme weather conditions that can affect flocks on the Central Asian steppe, can regularly kill millions of flock animals. |

| 32 | That the Scythians are representing higher levels of contest taking place on a supranatural level is an already popular idea, although discussed only in a vague and undefined sense. For instance, see (Simpson and Pankova 2017, p. 267). |

| 33 | For more on this object, see (Aruz et al. 2000, p. 261). |

| 34 | For more on this 5th century depiction of a griffin holding a stag’s head in its beak from Pazyryk 2, see (Aruz et al. 2000, pp. 270–71), for more on the golden stags of Filippovka, see (Farkas 2000, p. 14; Aruz et al. 2000, pp. 26–27, 72–79). |

| 35 | Spirits often appear in forms connected with the heavens, as lightning flashes or birds (Viveiros de Castro 2012, p. 108). |

| 36 | Examples of these creatures in Scythian art from the peripheries include: the Solokha gorytos (Cunliffe 2019, pp. 344–45), the golden torcs from the Oxus treasure (Simpson and Pankova 2017, p. 308) and the Peter the Great collection (Simpson and Pankova 2017, p. 39), and the chalcedony seal from a Scythian grave in the Greek Black Sea settlement of Nymphaeum, see (Vickers 2002, p. 42; Simpson and Pankova 2017, p. 290). For an overview of the Oxus treasure, see (Simpson and Pankova 2017, pp. 310–12). For an overview of the Nymphaeum site, see (Vickers 2002, pp. 1–55; Simpson and Pankova 2017, p. 286). |

| 37 | On this object, see (Simpson and Pankova 2017, p. 59). |

| 38 | Künzl has made a somewhat similar argument in relation to the Tolstaya Mogila pectoral, on which scenes of griffin predation appear alongside grasshoppers. Künzl suggests that the predation of the beasts represents the depravation wrought by the predation of a locust swarm (Künzl 2016). |

| 39 | As Cunliffe has said regarding the Scythians, “There can be no doubt that the constant battle for life ramified into every corner of nomad existence” (Cunliffe 2019, p. 289). |

| 40 | “It is not clear… that the horse sacrifices practiced by the Scythians had any connection with eternity, rebirth and the immortality of the king” (Farkas 1977, pp. 124–25). |

| 41 | For an outline of this interpretation, see (Price 2010). |

| 42 | For a similar reading, that animal style used to represent events from human lives, in this case in Pazyryk tattoos, see (Azbelev 2017). |

| 43 | On these objects, see (Artamonov 1970, p. 50; Cunliffe 2019, pp. 276–78). Bianili was the name the Urartians used for themselves. For an overview of Urartian history, language and culture, including incidents of contact with the Scythians, see (Baumer 2021, pp. 76–94). For a brief narrative history of Scythian interactions with the Urartians and Assyrians, see (Cunliffe 2019, pp. 31–35, 111–17). |

| 44 | On this object (SHM inv. no. Ky.1903-2/3), see (Artamonov 1970; Simpson and Pankova 2017, p. 198). |

| 45 | The resemblance between the two is so close as to suggest a shared origin, perhaps a place of manufacture or derivative source. The hatchet was also likely produced by the same workshop. For more on the Kelermes sword and scabbard, see (Simpson and Pankova 2017, p. 223; Cunliffe 2019, p. 115), for more on the Melgunov example, see (Artamonov 1970, p. 50; Cunliffe 2019, p. 116). |

| 46 | For more on Hellenistic Bosporan kingdom, see (Hind 1994) On the Bosporan grain trade, see (Hind 1994, p. 489). |

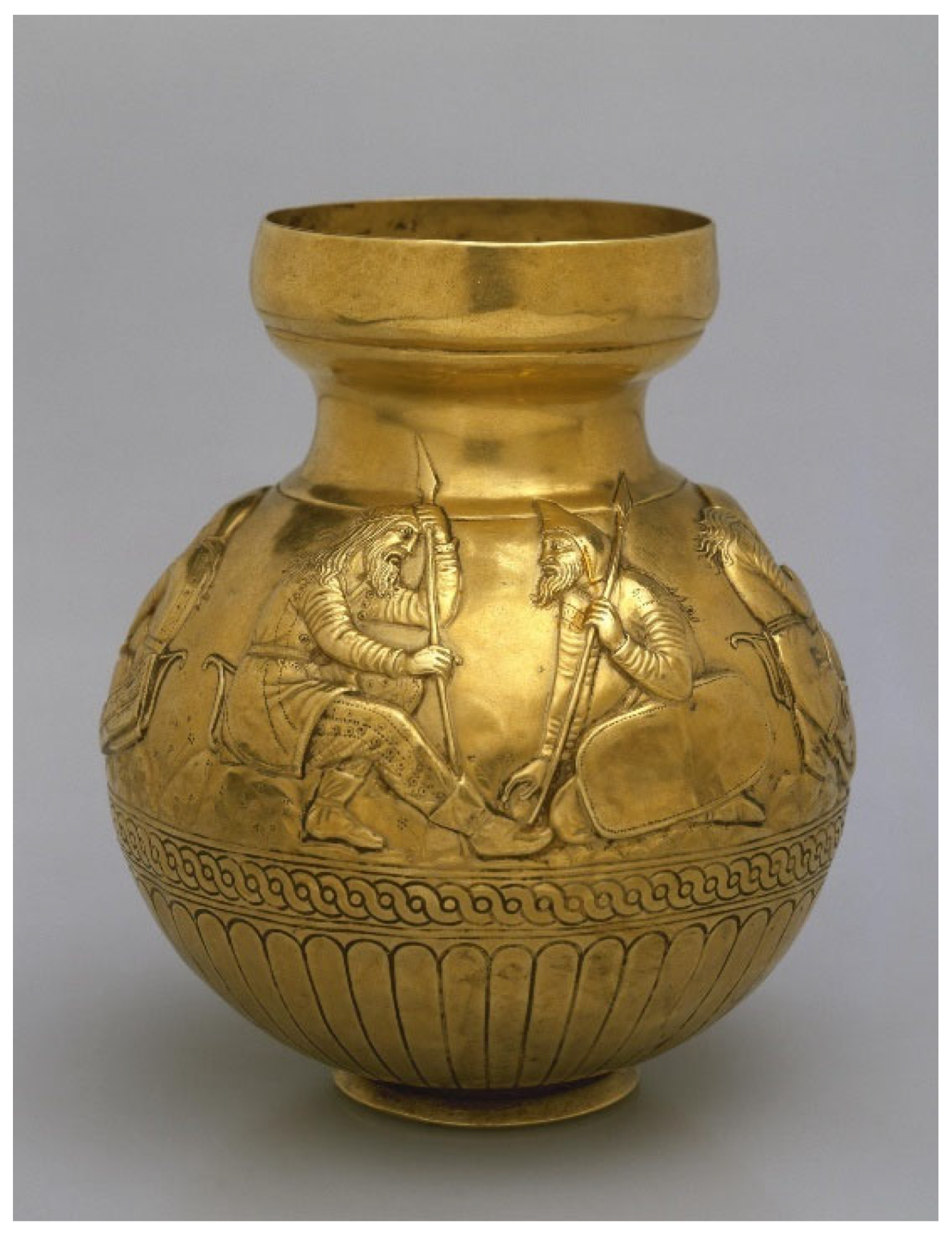

| 47 | On this object, see (Aruz et al. 2000, pp. 206–10; Simpson and Pankova 2017, p. 292; Cunliffe 2019, pp. 332–33). |

| 48 | On this object, see (Aruz et al. 2000, pp. 218–23; Cunliffe 2019, pp. 340–41). |

| 49 | For the shields (SHM inv. no. 1295-232) (SHM inv. no. 1295-382) found in Pazyryk 1, see (Simpson and Pankova 2017, pp. 230–31; Cunliffe 2019, p. 247). |

| 50 | For the pieces of scale armour (AM inv. no. AN 1885.465) found in Nymphaeum 6, see (Vickers 2002, pp. 46–47; Simpson and Pankova 2017, pp. 290–91). On Greek helmet finds in Scythian burials, see (Cunliffe 2019, pp. 249–50) On Scythian armour in general, see (Cernenko 1983, pp. 7–11; Cunliffe 2019, pp. 247–51). |

| 51 | On this object, see (Aruz et al. 2000, p. 223; Simpson and Pankova 2017, p. 294; Cunliffe 2019, pp. 338–39). |

| 52 | On this object, see (Simpson and Pankova 2017, p. 150). |

| 53 | Herodotus records several examples of the Scythians pouring libations as part of different rituals (Hdt. 4.62, 70). The inclusion of such a distinctly Greek object in a Scythian burial suggests the possibility of Greek influence on Scythian rituals, and potentially on Scythian beliefs in the contact zone. |

| 54 | On Chertomlyk kurgan, see (Simpson and Pankova 2017, pp. 26, 264–65). |

| 55 | On the production of the Chertomlyk artefacts, see (Treister 1999). |

| 56 | On this object, see (Aruz et al. 2000, p. 233). |

| 57 | On this object, see (Cunliffe 2019, pp. 344–45). |

| 58 | This interpretation was first suggested by the German archaeologist Carl Robert in 1889 and has been largely accepted by scholars (Aruz et al. 2000, p. 232). |

| 59 | For an interpretation of each scene as an episode in Achilles’ life, see (Aruz et al. 2000, p. 232). |

| 60 | For comparative studies of the Vergina gorytos with Scythian examples, see: (Plika 2015; Galdanova 2016) |

| 61 | For other studies of the amphora, see: (Kuz’mina 1976, 1982; Farkas 1977; Simpson and Pankova 2017, p. 265; Cunliffe 2019, pp. 350–51). |

| 62 | There are no good images available of the rear of the amphora and, as far as I am aware, no other English language scholars have made a description. A blurred black and white image is included in Kuz’mina’s work, from which it is unclear whether this top panel contains a direct repeat of the front scene or is left empty, see (Kuz’mina 1982). |

| 63 | On this object, including a complete reconstruction, see (Simpson and Pankova 2017, pp. 112–13). |

| 64 | Kuz’mina interprets the upper scene as decidedly rooted in Iranic astrology, an assumption that overlooks the deeply and uniquely Scythian nature of the motif (Kuz’mina 1976, 1982). In her counter argument, Farkas questions any straightforward Iranic equivalency but does still hold, from the object alone, that it could represent a cosmological conflict that reflects or interprets the earthly conflict below (Farkas 1977, p. 137). |

| 65 | Viveiros de Castro specifies that ‘some animals predated on by humans even see humans as spirits’ (Viveiros de Castro 2012, p. 127). |

| 66 | Currently housed in the Kiev Museum of Historical Treasures. On this object, see (Cunliffe 2019, pp. 286–87, 348–49). For an alternative interpretation, see (Künzl 2016). Interestingly, Künzl makes an interpretation similar to perspectvism of the griffins as representatives of a higher ‘predatory’ natural disaster in the form of the locusts depicted in the borders. |

| 67 | See notes 48 above. |

| 68 | In Chertomlyk, four men, one woman and twelve horses were killed and buried alongside their lord (Farkas 1977, p. 125). To what extent indeed could the relation of a lord to his subjects have been expressed in the visual language of predation? |

| 69 | For more on the relationship between Scythians and their horses, see (Recht 2021). |

References

- Amir, Saltanat, and Marcos Martinón-Torres. 2021. Goldworking of the Great Steppe: Technical Analysis of Gold Artefacts from Eleke Sazy. In Gold of the Great Steppe. Edited by Rebecca Roberts. London: Paul Holberton Publishing, pp. 137–55. [Google Scholar]

- Argent, Gala. 2010. Do the Clothes Make the Horse? Relationality, Roles and Statuses in Iron Age Inner Asia. World Archaeology 42: 157–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Artamonov, M. I. 1970. The origin of Scythian art. Soviet Anthropology and Archeology 9: 50–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aruz, Joan, Ann Farkas, Andrei Alekseev, and Elena Korolkova. 2000. The Golden Deer of Eurasia: Scythian and Sarmatian Treasures from the Russian Steppes. Edited by The Metropolitan Museum of Art. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art. [Google Scholar]

- Azbelev, Pavel Petrovich. 2017. Pazyryk Tattoos as an Artistic Testimony of Ancient Wars and Marriages. In Actual Problems of Theory and History of Art: Collection of Articles. St. Petersburg: St. Petersburg University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Baumer, Christoph. 2021. History of the Caucasus: At the Crossroads of Empires. London: I. B. Tauris/Bloomsbury, vol. 1. [Google Scholar]

- Broz, Ludek. 2007. Pastoral perspectivism: A view from Altai. Inner Asia 9: 291–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cernenko, Evgeniĭ Vasilevich. 1983. The Scythians, 700–300 BC. Edited by Martin Windrow. Men At Arms. London: Osprey Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Cunliffe, Barry. 2019. The Scythians: Nomad Warriors of the Steppe. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Da Col, Giovanni. 2007. The view from somewhen: Events, bodies and the perspective of fortune around Khawa Karpo, a Tibetan sacred mountain in Yunnan Province. Inner Asia 9: 215–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, Whitney. 2018. The absolute in the mirror: Symbolic art and cosmological perspectivism. In The Art of Hegel’s Aesthetics: Hegelian Philosophy and the Perspectives of Art History. Edited by Paul A. Kottman and Michael Squire. Paderborn: Wilhelm Fink, pp. 69–100. [Google Scholar]

- Desjardins, Sean P. A. 2017. A Change of Subject: Perspectivism and Multinaturalism in Inuit Depictions of Interspecies Transformation. Études Inuit Studies 41: 101–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Empson, Rebecca. 2007. Separating and containing people and things in Mongolia. In Thinking Through Things: Theorising Artefacts Ethnographically. Edited by Amiria Henare, Martin Holbraad and Sari Wastell. London: Routledge, pp. 113–40. [Google Scholar]

- Farkas, Ann. 1977. Interpreting Scythian Art: East vs. West. Artibus Asiae 39: 124–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farkas, Ann. 2000. Filippovka and the Art of the Steppes. In The Golden Deer of Eurasia: Scythian and Sarmatian Treasures from the Russian Steppes. Edited by Joan Aruz, Ann Farkas, Andrei Alekseev and Elena Korolkova. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, pp. 3–18. [Google Scholar]

- Galdanova, Oyuna Aldarovna. 2016. Figurative Images and Their Iconographic Prototypes in Decoration of Scabbard and Gorytos Overlays from Scythian Tombs of the 4th Century BC. Actual Problems of Theory and History of Art: Collection of articles 6: 42–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Heptner, V. G., A. A. Nasimovich, and A. G. Bannikov. 1988. Mammals of the Soviet Union: ARTIODACTYLA and PERISSODACTYLA. 3 vols. Vol. I. Mammals of the Soviet Union. Translated by P. M. Rao. Edited by Robert S. Hoffmann, V. G. Heptner, N. P. Naumov and V. S. Kothekar. New Delhi: Amerind. [Google Scholar]

- Heptner, V. G., and A. A. Sludskii. 1992. Mammals of the Soviet Union: CARNIVORA (Hyaenas and Cats). In Mammals of the Soviet Union. 3 vols. Translated by P. M. Rao. Edited by V. G. Heptner, N. P. Naumov, Robert S. Hoffmann and V. S. Kothekar. New Delhi: Amerind Publishing Co., vol. II.2. [Google Scholar]

- Hind, J. 1994. The Bosporan Kingdom. In The Cambridge Ancient History. Edited by D. Lewis, J. Boardman, S. Hornblower and M. Ostwald. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 476–511. [Google Scholar]

- Korolkova, Elena F. 2017. Siberian collection of Peter the Great. In Scythians: Warriors of Ancient Siberia. Edited by St John Simpson and Svetlana Pankova. London: Thames & Hudson, pp. 32–69. [Google Scholar]

- Kristensen, Benedikte Møller. 2007. The Human Perspective. Inner Asia 9: 275–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuz’mina, E. E. 1976. O semantike izobrazhenii na chertoml’shchkoi vase. Sovetskaia arkheologiia 3: 68–75. [Google Scholar]

- Kuz’mina, E. E. 1982. On the Semantics of the Images on the Chertomlyk Vase. Soviet Anthropology and Archeology 21: 120–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Künzl, Ernst. 2016. Life on Earth and Death from Heaven: The Golden Pectoral of the Scythian King from the Tolstaya Mogila (Ukraine). In The Archaeology of Greece and Rome: Studies In Honour of Anthony Snodgrass. Oxford: Oxford University Press, pp. 317–36. [Google Scholar]

- Marina, Vanzolini, and Pedro Cesarino. 2014. Perspectivism; Oxford Bibliographies Online. Oxford: Oxford University Press, August 26. Available online: https://www.oxfordbibliographies.com/view/document/obo-9780199766567/obo-9780199766567-0083.xml (accessed on 23 July 2022).

- Pedersen, Morten A. 2001. Totemism, Animism and North Asian Indigenous Ontologies. Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute 7: 411–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pedersen, Morten A. 2007. Talismans of thought: Shamanist ontologies and extended cognition in northern Mongolia. In Thinking Through Things: Theorising Artefacts Ethnographically. Edited by A. Henare, M. Holbraad and S. Wastell. London: Routledge, pp. 151–76. [Google Scholar]

- Plika, Peli. 2015. A Comparative Research between the Macedonian Tombs and the Scythian Kurgans. Nea Moudania: MA Black Sea Cultural Studies, School of Humanities, The International Hellenic University. [Google Scholar]

- Price, Neil. 2010. Passing into Poetry: Viking-Age Mortuary Drama and the Origins of Norse Mythology. Medieval Archaeology 54: 123–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Recht, Laerke. 2021. My Kingdom for a Horse: Saka-Scythian Horse-Human Relations. In Gold of the Great Steppe. Edited by Rebecca Roberts. London: Paul Holberton Publishing, pp. 119–36. [Google Scholar]

- Samashev, Zainolla, Abdesh Toleubayev, Saltanat Amir, Claudia Chang, Marcos Martinón-Torres, and Laerke Recht. 2021. Gold of the Great Steppe. Edited by Cambridge The Fitzwilliam Museum and East Kazakhstan Regional Museum of Local History. London: Paul Holberton Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Seaman, Gary, and Jane Stevenson Day. 1994. Ancient Traditions: Shamanism in Central Asia and the Americas. Niwot: University Press of Colorado. Denver: Denver Museum of Natural History in cooperation with Ethnographics Press, Center for Visual Anthropology, University of Southern California. [Google Scholar]

- Simpson, St John, and Svetlana Pankova. 2017. Scythians: Warriors of Ancient Siberia. Edited by The British Museum. London: Thames & Hudson. [Google Scholar]

- Squires, Victor R. 2012. Rangeland Stewardship in Central Asia: Balancing Improved Livelihoods, Biodiversity Conservation and Land Protection. London: Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Treister, Michael. 1999. The Workshop of the Gorytos and Scabard Overlays. In Scythian Gold: Treasures from Ancient Ukraine. Edited by Ellen D. Reeder. New York: Harry N. Abrams, Inc., pp. 71–81. [Google Scholar]

- Vickers, Michael. 2002. Scythian and Thracian Antiquities in Oxford. Edited by Timothy Wilson. Ashmolean Handbooks. Oxford: Ashmolean Museum. [Google Scholar]

- Viveiros de Castro, Eduardo Batalha. 1998. Cosmological Deixis and Amerindian Perspectivism. Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute 4: 469–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viveiros de Castro, Eduardo Batalha. 2007. The Crystal Forest: Notes on the Ontology of Amazonian Spirits. Inner Asia 9: 153–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viveiros de Castro, Eduardo Batalha. 2012. Cosmological Perspectivism in Amazonia and Elsewhere: Four Lectures Given in the Department of Social Anthropology, Cambridge University, February–March 1998. Masterclass Series; Manchester: HAU, Journal of Ethnographic Theory, vol. 1. [Google Scholar]

- West, Stephanie. 2007. Herodotus and Olbia. In Classical Olbia and the Scythian World: From the Sixth Century BC to the Second Century AD. Edited by David Braund and S. D. Kryzhitskiy. London: British Academy. [Google Scholar]

- Willerslev, Rane. 2004. Not animal not not-animal: Hunting, imitation and empathetic knowledge among the Siberian Yukaghirs. Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute 10: 629–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Willerslev, Rane. 2007. Souls Hunters: Hunting, Animism, and Personhood among the Siberian Yukaghirs. Berkeley: University of California Press. [Google Scholar]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Sharkey, B. Predators and Prey: Cosmological Perspectivism in Scythian Animal Style Art. Arts 2022, 11, 120. https://doi.org/10.3390/arts11060120

Sharkey B. Predators and Prey: Cosmological Perspectivism in Scythian Animal Style Art. Arts. 2022; 11(6):120. https://doi.org/10.3390/arts11060120

Chicago/Turabian StyleSharkey, Benjamin. 2022. "Predators and Prey: Cosmological Perspectivism in Scythian Animal Style Art" Arts 11, no. 6: 120. https://doi.org/10.3390/arts11060120

APA StyleSharkey, B. (2022). Predators and Prey: Cosmological Perspectivism in Scythian Animal Style Art. Arts, 11(6), 120. https://doi.org/10.3390/arts11060120