Abstract

During the last five decades, the entire Christian religious landscape of the Sea of Galilee has undergone a gradual and steady reshaping, with devotional centers renovated, rebuilt, and even re-invented. Together they frame the area around the Sea of Galilee as A Holy Land in itself, an enclave not only with unique characteristics distinguishing it from The Holy Land as a whole, but also in competition with it. Among the many establishments, one site does this explicitly in both word and image: the Duc in Altum center of worship built on the presumed location of the ancient city of Magdala. In this article, we explore the visual strategies and mechanisms that enable the site to assert its alleged authenticity and legitimacy; lay the foundations for a theoretical framework for understanding the ideological processes of the current Christian art around the Sea of Galilee; and suggest that these strategies are paradigmatic to the redefining of the religious and political identity of the entire region of the Sea of Galilee in order to establish it as A Holy Land of its own.

1. Envisioning a Sacred Site Anew

Following the inauguration of the Basilica of the Annunciation in Nazareth in 1969, the entire religious landscape of the Sea of Galilee underwent a gradual and steady reshaping.1 The former 18th-century Franciscan Basilica of the Annunciation was too modest to attract significant pilgrimage, and having no unique architectural features it also had minor influence on its surroundings.2 With the demolition of the older building, a grand new project was set into motion: a full rebuilding set to change the visual language of the religious monument.3 Unlike previous modern endeavors in the Holy Land that adapted historical styles for new sites, the 1969 basilica in Nazareth designed by the Italian brutalist architect Giovanni Muzio manifested an entirely novel architectural language.4 The increasing weight of Nazareth as a pilgrimage target and the impact of its sensational building triggered influential ecclesiastical patronage—Benedictine, Franciscans, Orthodox, among many nationalities—to further develop the wider region. This spectacular project was but the opening shot of a long process that continues to this day of recreating the entire area of the Sea of Galilee as a pivotal pilgrimage destination that outcompete the more established and prestigious sacred Christian sites, such as the Church of the Holy Sepulchre in Jerusalem and the Church of the Nativity in Bethlehem.5 The creative building activities took on varying forms. Older sacred establishments were extensively renovated, others were and still are being completely rebuilt, and several, as we will demonstrate below, have even been invented.6

We argue that the development of the Sea of Galilee area as a differentiated pilgrimage goal, especially in the 21st century, is not an organic continuation of past processes of either medieval or modern Christian pilgrimage in the Holy Land. Many of the local ancient sites have been abandoned or demolished over the course of time, and those that survived were no competition for the more elaborate centers of pilgrimage.7 Consequently, the relatively marginal status of the Sea of Galilee area in modern devotional practices has seen drastic changes over the last few decades. The new establishments redefine the area of the Galilee as distinct from other cultic sites in the Holy Land. Each individual renewed locus sanctus of the region has independently striven to tell its own distinct part of a uniquely Galilean story. Together they frame the area around the Sea of Galilee as A Holy Land in itself, an enclave not only with unique characteristics distinguishing it from The Holy Land as a whole, but also in competition with it.

Among the many establishments, one site does this explicitly in both word and image: the Duc in Altum center of worship built on the presumed location of the ancient city of Magdala– a major Roman port city on the shores of Galilee, home to Mary Magdalene. Duc in Altum, inaugurated in 2014, is but a part of a larger pilgrimage complex that includes several foci of interest: an archeological park presenting the ancient Jewish city of Magdala;8 a hotel for the pilgrims; and the spiritual center itself, the Duc in Altum. Erected directly on the historical site of the excavation identified as Magdala and incorporating archaeological excavations from a campaign held between 2004 and 2009 (and still ongoing),9 the center employs various artistic strategies in order to establish its claim as a primary pilgrimage target. It commemorates several of the events of Christ’s ministry around the Sea of Galilee in its art.10 Most of the biblical events that are commemorated (and have been appropriated) by the site, however, are not in fact specifically attributed in the Scriptures to the city of Magdala, they began being associated with this place since the initiation of the new pilgrimage center.

Exploring how religious goals found visual expression, this article has four aims: to frame the regional artistic arena around the Sea of Galilee; to explore the visual strategies and mechanisms that enable the site to assert its alleged authenticity and legitimacy; to establish the foundations of a theoretical framework for understanding the ideological processes of the current Christian art around the Sea of Galilee; and to posit that these strategies are paradigmatic to the redefining of the religious and political identity of the entire region of the Sea of Galilee in order to establish it as A Holy Land of its own.

We begin this article by contextualizing the building of Duc in Altum within the historical perspective of envisioning the area of the Sea of Galilee as A Holy Land.11 We briefly reflect on the idiosyncratic development of the Sea of Galilee in contrast to other regional centers in the Holy Land, while also indicating the scholarly lacuna in the study of the region, with Duc in Altum as a case in point.

The Duc in Altum worship center has never previously been academically studied, and our investigation thus incorporates field work, interviews, and historical propositions. In the following, we closely describe and analyze the entire range of artistic media employed in the creation of the Duc in Altum site: architecture, mosaics, frescos, paintings, objects, and even cellular cameras. Each of the different spaces of the place reveals its own use of artistic media and unique visual manipulation. We will demonstrate the interplay between tradition and innovation, which work together to spark the imagination of visitors and foster a meaningful experience at a newly-established pilgrimage site. Since the histories, both ancient and modern, of the site have been sparsely documented, we will refer to the local studies and publications and the credo of the site’s patron—Mexican-born Father Joan Solana. These sources, however, will be cautiously addressed, in being religiously and even politically motivated. The different spaces of the center provide various potentials for interaction with the past and with the surroundings, in ways perhaps more experiential and experimental then might be expected in a contemporary religious Christian building. We will then frame the visual strategies of the site through three key terms: (a) site-specificity—in this context, a work of art that gains its meaning only from its direct relation to its location and its histories. If divorced from its specific geographical site, the artwork would lose its web of signifiers; (b) calculated estrangement—a term coined by us to refer to visual characteristics that intentionally mark a work of art as rooted in foreign places and cultures, and therefore alienated from the local realities. Such calculated estrangement is not accidental. Rather, it is a strategy that reflects religious, political and social differentiation and agendas; and (c) staged authenticity, real and fabricated, by which we refer to the use of actual or pseudo archaeological findings in order to bestow upon the site an aura of authenticity and antiquity. Moreover, these are inserted into the new complex that stages the entire scenery as authentic. This triple strategy is enacted by various actors and patrons with various religious and political motivations.12

2. A Holy Land within the Holy Land: An Historical Perspective

Over the centuries, the Eastern and Western Christian Churches have demonstrated a changing degree of connection with the Holy Land (Bowman 1991, pp. 98–121; Liron 1997). From their initial establishment in Late Antiquity to the Crusader Conquest of 1099, the holy places had become active sites of pilgrimage flagged by monumental architecture (Wilkerson 1977; Kühnel 1998). After the fall of the Crusader Kingdom, the Franciscans became (from the 14th century on) the official custodians of the Holy Places in the name of the Catholic Church, which operated their sites alongside those of the Eastern-Christian communities, including sites belonging to the Greek-Orthodox, Armenian, Coptic, Assyrian, Ethiopian, and other Churches (Roncaglia 1950; Simon 1980). Under the Ottoman Empire, although Christians had rights of protection and control over the holy places, they did not have exclusive ownership of them. In 1535, the Capitulation contract between the Ottoman Empire and other powers in Europe, particularly France, gave French institutions the main role in protecting the Catholic Christians in the Holy Land.

This situation significantly changed with the decline of the Ottoman Empire in the 19th century and the secularization of France, with its constitutional separation between state and religion in 1905, which prohibited any further governmental involvement in the religious arena (Desramaut 1986). Consequently, certain European powers, predominantly Russia, Britain, Germany, Italy, and some individual French patrons, began to expand their presence and authority in the former Ottoman territories, focusing especially on the Holy Land. An extensive construction of churches began there, mainly in Jerusalem, as close as possible to the Church of the Holy Sepulchre, as well as Franciscan renovations and new construction at sites outside Jerusalem such as Emmaus (Halevi 2012b).

Along with their desire to protect the sacred places, the various European powers also sought to perpetuate and strengthen their own nation’s standing in the Holy Land by creating complexes designed with a strong visual reference to the artistic styles characteristic of their home country. For example, Russian churches in the Holy Land were constructed with the “onion domes” of Orthodox churches in Russia and Ukraine, including in the Holy Trinity Cathedral (1860–1872) and the Church of Mary Magdalene (1888) in Jerusalem (Kroyanker 1987). Similarly, St. Louis Hospital (1879–1896) and the Notre-Dame de France guesthouse and church (1884–1904) located near the northwest corner of the Old City walls, used French architectural models as their main source of inspiration (Ibid.). The Lutheran Church of the Redeemer (1898), the Benedictine Church of the Dormitian Abbey (1901–1910), and the Augusta Victoria Hospital on the Mount of Olives (1910), built under the patronage of the German Emperor Wilhelm II, relied on identifiably German models (Arad 2005a, 2005b). Similar national tendencies are also evident in the endeavors initiated by the British Empire, such as the St. George College and Cathedral (1899), and by Italy, such as the Italian hospital and church in Jerusalem (1919). The 19th-century tendency, and up to around the 1960s, therefore, was that of the local use of models from the country of origin, to signal a connection to the source of the founding community. In other cases, national reinterpretations of medieval art and architecture were used to strengthen connections to the countries of origin of the different communities.

This situation was initially true also for the area around the Sea of Galilee. Several sites built from the 19th century and into the early 20th century reflect strong influences from the home countries of the founding communities, such as St. Peter’s Church in Tiberius (mid-19th c.), the Greek-Orthodox Church of the Twelve Apostles (1927), the Primacy of Peter (1934), and the Church of the Beatitude by Barluzzi (1936) (Halevi 2009, 2012a). These were distinct but sporadic cult centers, founded by differentiated and even competing religious groups. They were designed as visually akin to European models and complementary in style to concurrent architecture in Jerusalem and across the Holy Land. However, in the mid-20th century a radical change in strategy occurred. Numerous new endeavors began to reshape the geography and architectural landscape around the Sea of Galilee to incorporate completely foreign architectural elements, forcibly modern (rather than historicizing) and universal (rather than national).

From the 1960s onwards, the following decades saw an influx of new foundations: first and foremost the Basilica of the Annunciation, consecrated in 1969 (Segal et al. 2020). As already noted in the Introduction, the new brutalist approach and the breaking with tradition, had immense regional ramifications. This foundation was closely followed by a rebuilding of the Church of the Multiplication of the Loaves and Fishes (1982), the Yardenit Baptism site (1982), the Pilgrimage Church of St. Peter in Capernaum (1990), the discovery of a ‘Jesus Boat’ (1986) housed today in the Yigal Allon Museum (2000), the Neocatechumenal Way’s center ‘Domus Galilae’ (1999–2003), and Duc in Altum in Magdala (2014). During the same period, various religious destinations have been renovated and embellished: the renovation and new pictorial cycle of the Greek-Orthodox Church of the Holy Apostles (renovated 1969; originally built 1927–1931); the renovation and new embellishment of the Franciscan Church of the Primacy of Saint Peter (renovated 1964 and 1982; originally built 1933); new mosaics in the crusader Church of St. Peter in Tiberias (alteration after 1980, originally built 1847). Furthermore, the religious denominations active in founding and reinvigorating holy sites have greatly grown and diversified since the 1960s.

These reinvigorations and building-campaigns have integrated both the older and the newly-founded churches into a changing landscape. They have engineered artistic manifestations that have led to a differentiated pilgrimage circuit, even to an alternative Holy Landscape—A (new) Holy Land within The Holy Land. This circuit, comprising independent but interconnected sites, has a dynamism and aesthetic of its own, located predominantly in innovations of the last few decades and comprising extremely diverse Christian representations. Consequently, it draws a wide spectrum of pilgrims/tourists, including Jews and Muslims. The sites, however, are completely estranged to both Israeli and Palestinian space, to urbanism, and to aesthetics. This (religious) notion is clearly articulated in the bronze doors of the Basilica of the Annunciation in Nazareth. The main door through which the pilgrims enter the church features Mary and the Infant Jesus in the gable, flanked by King David playing the harp, with Nathan at his feet to the left; and the prophet Isaiah rejecting King Ahab and pushing him outside in the opposite direction of the main scene. The inscription reads: Regnum tuum usquein aeternum—thy kingdom, unlike that of Ahab (representing the kingdom of Israel) is eternal (2 Samuel 7: 16), referencing the contemporary entities and realities as ephemeral and estranged (Pinkus 2020, pp. 175–76).

These changes are partially anchored in developments within the Roman Catholic Church in the second half of the 20th century (Proctor 2016, pp. 133–218). Following the decisions by the Second Vatican Council (1962–65) to enable a free scope of modern art (provided that it confers upon the sacred buildings due honor and reverence), a significant change in the ideology of church building has occurred (McNamara 2009). Liturgical changes arising from the Second Vatican Council (regarding the languages used for preaching and a decision that the priest should face the congregation during the mass), have resulted in a new spatial organization as well (Longhi 2020, pp. 69–94).

In spite of these intensive developments, along with their political and inter-religious significance for modern Israel, and the involved ecclesiastical institutions (Dumper 2002; Bowman 1993), modern Christian art and architecture in the Holy Land has thus far been little studied.13 Most of the scholarship has looked at pilgrimage practices and the liturgy rather than the modern sites themselves.14 There is an important body of studies on specific 19th- and 20th-century churches, mainly on edifices in and around Jerusalem,15 but no comprehensive research exists on the contemporary churches in the Holy Land. Furthermore, unlike the studies focusing on Jerusalem and its surroundings, there has been no theorization of the connections between the churches around Galilee and their European or other international models.

The second focus of several monographic works has been on Nazareth, mainly the work by Nurith Kenaan-Kedar on the modern Basilica of the Annunciation in Nazareth, by Einat Segal on the Salesian Church of Jesus the Adolescent in Nazareth (Segal 2011, 2013, 2014, 2016) and on the modern frescos of the Greek-Orthodox Church of the Annunciation (Sharif-Safadi 2014, pp. 51–66). Recently, the first comprehensive anthology of monographs was published on the modern Basilica of the Annunciation in Nazareth, encompassing research covering all the types of artistic media in the church (Segal et al. 2020). Therein Segal, for example focuses on the nationalistic versus universal in the dozens of stained-glass windows of the church, and their stylistic origins and various artists, while Nira Tessler highlights issues of multi- versus trans-culturalism in the famous Madonna panels, commissioned by multiple communities around the globe (Segal 2020; Tessler 2020, pp. 211–28). Other contributions in this anthology, by leading scholars, investigate the modernist concrete architecture (Irace 2020, pp. 95–106); the impact of the Second Vatican Council on the design of the architecture and its decoration as reflecting trans-cultural religious space in a global world (Longhi 2020, pp. 69–94); while also reflecting on the crusader past of the edifice and its sculptural embellishments,16 (as well as the Franciscan history of the cult and the local economy) (Kedar 2020, pp. 53–68; Klimas 2020, pp. 123–44).

The smaller churches around the Galilee have received even less scholarly attention as individual sites and, especially, have not been addressed as a modern phenomenon or as a distinctive group. They have mainly been referred to either in archeological reports and denominational religious publications or in tourist pamphlets. Since these minor publications were initiated and motivated by rival religious orders, they have ignored the wider phenomena and collaborations between churches. In the academic milieu too, while in the last decade some efforts have been invested in the study of modern Christian art in the Jerusalem area and in Nazareth, none have focused on the study of the vibrant modern and contemporary artistic production around the Sea of Galilee. Moreover, since all the previous studies have considered each artistic campaign as an isolated phenomenon, the overall effect of the intensive production around the Sea of Galilee has been ignored. We suggest that the processes that we will demonstrate for Duc in Altum are paradigmatic to the Galilee religious circuit, which has its own characteristics, defined by circumstances specific to the 20th and 21st centuries.

3. The Duc in Altum Worship Center: The Power of Suggestion

In 2006, at the initiation of Father Juan Solana, the papal appointee in charge of the Pontifical Institute Notre Dame of Jerusalem Center, land was acquired north of Tiberias. With the discovery of rich archaeological remains this area of land became identified as Magdala, the hometown of Mary Magdalene, the woman who became the first apostle, the Apostola Apostolorum, and was exorcised by Christ (Brock 2003). The site is located along the major Roman commercial trade route, the Via Maris, and on the way from Nazareth to Ginosar and Capernaum. Over the years, the ancient settlement of Magdala fell prey to the ravages of time. After the 1948 Arab-Israeli war the small village al-Majdal that had once stood at the site was destroyed, and the area is now under the jurisdiction of the municipality of the modern Israeli town of Migdal. During 2008–2009, the Catholic organization the Legionaries of Christ acquired additional land in the area and the first stone of the new building was blessed by Pope Benedict XVI in May 2009 (García 2016, pp. 153–57). The excavations culminated during 2021 in the extraordinary finding of a second synagogue, dating to the period of the Second Temple, and the unearthing of the sensational Magdala Stone, interpreted as depicting the Temple’s liturgical objects and thus one of the most significant findings over the last half century.17 These various archaeological campaigns revealed the 1st-century Roman remains of the city, its water system, mikveh (Jewish ritual bath), the harbor, the industrial zone of Migdal, and the remains of synagogues dated to between 50 BCE and 100 CE.18 These places were perceived as those that Jesus had visited and in which he had acted and taught. Most of the events represented in the spiritual center, however, are not directly attributed in the New Testament to the city of Magdala. Moreover, the remains of the site, associated in the crusader period (1099–1187) with the tomb of Mary Magdalene, are located a few kilometers outside Magdala and its worship center. The current pilgrimage site, therefore, has no known pilgrimage attribution prior to the 21st century.

Under the initiation of Father Juan Solana, the site was envisioned as a spiritual center, a place where pilgrims could enjoy comfortable accommodation in a devotional atmosphere on the shores of the Sea of Galilee, alongside the emerging archaeological site. This religious, and also touristic, intention, as we shall see, has had far-reaching consequences and implications for the area around the Sea of Galilee. To date, apart from the pilgrimage guesthouse and the impressive development of the archeological garden, which comprise the main part of the ambitious religious-artistic plan for the envisioned worship center of Duc in Altum (Figure 1), the other components planned for Magdala are still under constructions.

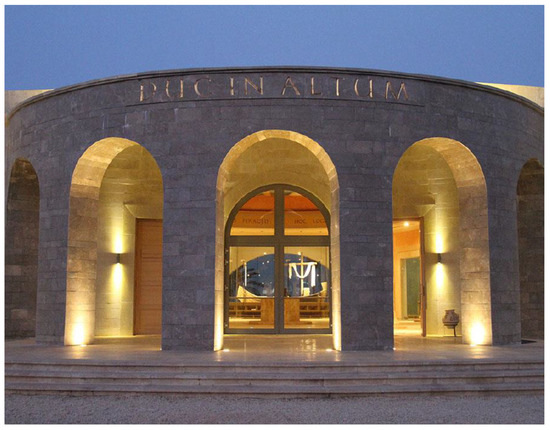

Figure 1.

West Façade, Duc in Altum Worship Center, 2014 (photo: PD).

The Duc in Altum—“put out [the nets] into the deep”—commemorates the event in which Christ commanded Simon Peter and the fishermen to go into the depths of Lake Gennesaret (the Sea of Galilee) to catch fish and feed the masses: “When he had finished speaking, he said to Simon Peter, ‘Put out into deep water (duc in altum), and let down the nets for a catch’” (Luke 5: 4).19 This command is extended in the site’s publications to the visitors, inviting them to enter both physically and spiritually “into the deep” as they enter the space. The invitation to personally experience the events is well exploited through various visual aids that provide a powerful suggestion that it was in this very place that it had all happened.

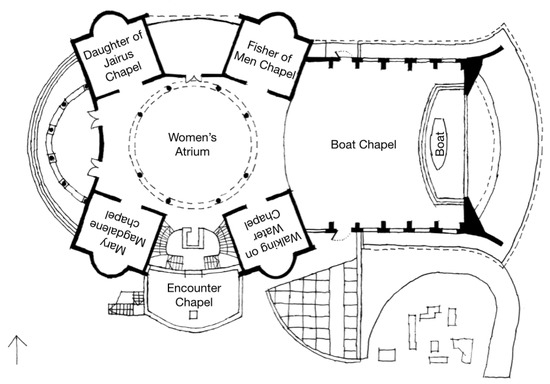

4. For All the Pious Women Who Followed Christ: The Women’s Atrium

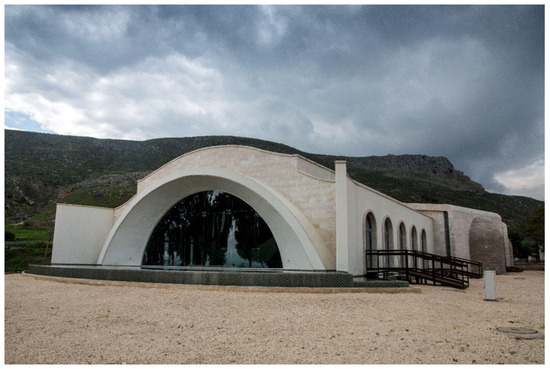

The first hall welcoming the visitor upon entering the center of worship is the Women’s Atrium, a domed eight-sided space with eight columns. The architecture of the entire center is inspired, according to Father Juan Solana, by late antique Byzantine octagonal structures.20 The overall shape of the worship center, however, is at odds with any historical church design (Figure 2 and Figure 3). The sides of the octagon are not fully regular—the eastern and western ones are significantly longer than the six others. To either side of the octagon (north and south) are two chapels flanking a stairwell to the crypt in the south and a sacristy to the north. In the east lies a rectangular space that constitutes the main hall of worship, a kind of cappella maggiore, with windows looking out eastwards to the Sea of Galilee. Each of the different architectural units—octagonal hall, four lateral chapels, rectangular hall, and crypt—is designed with a different visual language based on a distinct content-emphasis.

Figure 2.

East Façade, Duc in Altum Worship Center, 2014 (photo: Ilan Amihai, Alamy Stock Photo).

Figure 3.

Ground Plan of Duc in Altum Worship Center. (plan: Naomi Simhony after de la Garza).

Seven of the eight columns of the Women’s Atrium are dedicated to women who had followed the footsteps of Christ: Mary Magdalen (John 20: 1); ‘Aliae multiae’ (the many others who followed him to Jerusalem) (Mark 15: 41); Mary, wife of Clopas (John 19: 25); Peter’s mother-in-law who was healed by Christ (Matthew 8: 15); Salome, wife of Zebedee and mother of John and Jacob the Greater (Matthew 20: 20); Mary and her sister Martha (Luke 10: 38); Susanna and Joanna, the wife of Chuza (Luke 8: 3). An eighth column (between the column with Mary and her sister Martha and that of Susanna and Joanna) is empty, left without an identifying inscription, dedicated to all women. This eighth column is explained in the church booklet as dedicated to all anonymous women imbued with true faith from every epoch and every geographical area of the globe.21 This global orientation can be seen as the realization of the decision of the Second Vatican Council (convened in 1962; conclusions signed in 1965), instructing the Church to open its rituals to the participation and conduct of all races and genders.22 This approach is echoed and perhaps also intensified by the inscription on the dome’s drum, inspired by Pope John Paul II’s blessing to all women (Mulieris Digintatem) wherever they are (The Holy 1963 chapter 4 clause 2). Similarly, the dome crowning the atrium is adorned with a fresco above the center that employs a unique iconography (Figure 4), derived (with alterations) from the venerated image of ‘The Virgin of Guadalupe’, the Patroness of Mexico and the Continental Americas. The dome fresco portrays the two hand-palms of the Madonna joined in prayer, seven stars set against a blue background, and several of the gold rays that usually surround her full-length representation in a mandorla. Depicting these familiar elements on the atrium dome confers a visual presence of the Latin-American patronage and funding of the church.23 Originating in a miraculous image dated to 1531 the image was considered as an acheiropoieton—known as the Tilma—no less important then the Veronica; as such it became deeply interwoven with Mexican religiosity (Noreen 2018). While the Women’s Atrium is responsive to the universal and multi-cultural challenges extended by the Second Vatican Council to the ecclesiastical institutions, the crown of chapels—four lateral ones and a cappella maggiore in the tradition of Romanesque sacred architecture of the Latin West—reveals a complementary strategy: localization. The two work in syncretism to produce forms both universal and particular to the Middle-Eastern setting, real and imagined.

Figure 4.

Hands of the Virgin of Guadalupe, Women’s Atrium, Dome (photo: Assaf Pinkus).

5. Mosaic “Windows” to a Re-Imagined City: The Four Lateral Chapels

The women’s atrium is flanked by four chapels, each adorned with a large mosaic in the apse behind an altar (Figure 3). The mosaics were commissioned from the Chilean artists Juan Fernández and María Jesús Ortiz and executed in the Italian workshop of Valerio Lenarduzzi. The chapels are dedicated to the public ministry of Christ, with two foci: the two western chapels near the entrance feature women who were miraculously healed by Christ, while the two eastern ones feature events that had taken place on the shores and waters of the Sea of Galilee. This arrangement reflects the physical landscape around the site: the scenes of the Calling of Peter and Andreas and the Calming of the Storm in the east are installed facing the lake, the very waters in which they had occurred; while the healing miracles that were performed on land are situated facing Mount Arbel and the ruins of the town of Magdala. Each event of Christ’s ministry is thus depicted against a background representing the local landscape that lies behind the center’s walls. The visual narratives are situated within an extended space, merging the site’s interior and exterior. The solid concrete structure itself is thus de-materialized and turns “transparent”, and the pilgrims find themselves within the ‘true locus sanctus’ itself. Duc in Altum thereby declares itself to be a site-specific monument, not only through its immediate relation to the historical context, but also through the localization of both the imaginative (mosaics) and real (landscape). In the words of Father Juan,24 each mosaic becomes an open window. Nevertheless, although all the events are indeed reported to have happened in or around the Galilee, none of them are reported in the New Testament as occurring specifically in Magdala.

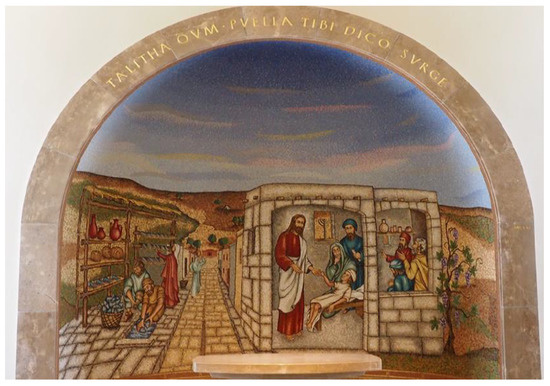

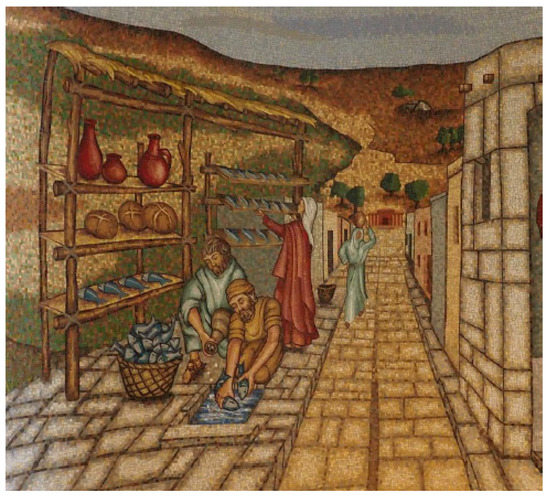

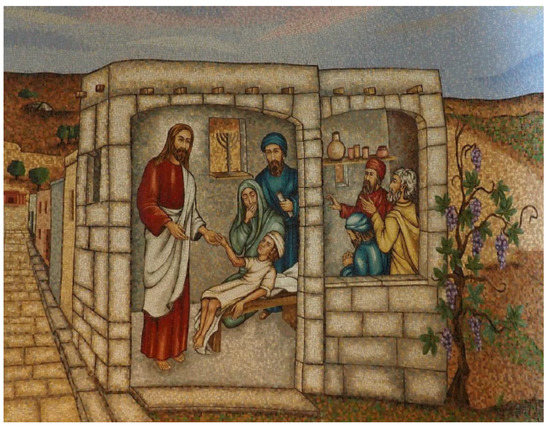

Entering the Daughter of Jairus chapel to the left (north), the visitor is confronted with a spectacular imaginative vista, evocative of ancient Magdala (Figure 5). The mosaic depicts the resurrection of a young girl, a scene often known by the words in Aramaic with which Christ urged the girl to rise “Talitha qum” (“Little girl, get up!”; Mark 5: 41). The composition is divided into two: on the right the miracle of the resurrection of Jairus’ daughter by Christ is shown taking place in a small stone house, whose fourth wall is ‘removed’ (as in medieval art) to allow the viewer to peer in and witness the miracle. On the left is a depiction of market life in a generic ‘old’ city, alluding to the ancient city of Magdala. A Roman road passes through and separates the two parts of the mosaic, between the miracle that was not performed in Magdala and the market that suggests otherwise. The perspectival lines of the streets of the imaged city converge at an ancient Roman building—an imaginary reconstruction of the ancient synagogue resurrected from the nearby archeological excavations, as Father Solana himself testifies.25

Figure 5.

Talitha qum (Daughter of Jairus), Northwest Chapel (photo: Assaf Pinkus).

According to the New Testament, the miracle of the raising of Jairus’ daughter occurred in the general area, but without any specific mention of Magdala. The paving of the market street, reminiscent of that found in the nearby excavations, and the facade of the synagogue in the center of the background, suggest locality. They enable the viewers to imagine the scene occurring right here, where they stand, in the very place where the market was once held in the days of Christ’s ministry. A close examination of the details reveals other captivating local references. The miracle portrayed on the right takes place inside a small stone building.26 The one-room house is the first in a row of small, colorful, cubic houses depicted on either side of the road. These structures, which appear in the mosaics of two other lateral chapels, are reminiscent of many 19th-century Arab-Palestinian villages as portrayed in Romantic-Orientalist painting, and even more specifically of the houses in the Palestinian-Arab village Al-Majdal (located on the western shore of the Sea of Galilee), which too had been one-story stone houses.

In the market scene, the allusion to Magdala is further strengthened. The main goods on offer are wine, bread, and fish. This is not a generic image of commerce but, rather, one potentially calling to mind both the Eucharist and the Miracle of the Loaves and Fishes, another event from Christ’s ministry related to the Sea of Galilee. That miracle is associated with Tabgha near Capernaum (north of Magdala) and this may account for its implicit inclusion rather than a clear depiction of the scene. The foreground of the market scene refers even more directly to the Magdala excavations: the man in the foreground is bending towards a small rectangular water source, a salting pool, to which Magdala owed its prosperity and reputation throughout the Roman world.27 Comparable pools were found during the archaeological dig at the site itself, as well as the remains of Magdala’s urban market and harbor (Figure 6 and Figure 7). Hence the entire scene is transposed or relocated to Magdala. In the distance can be seen a woman, dressed in white and walking along the street towards the market, carrying an urn on her head.28 This is a highly charged political image: on the one hand, it is an ancient image of the personification of the well or a biblical image such as the story of Rebecca and Eliezer from Genesis (24: 11–19), in which she carries the jar on her head; on the other hand, it is a powerful local controversial image that could be understood as either an Arab-Palestinian national image or as a national symbol appropriated by the Zionist movement (Kennan-Kedar 2013, pp. 49–50).

Figure 6.

Detail: Market Scene.

Figure 7.

Magdala archaeological site, Salting Pools, 1st Century (photo: Assaf Pinkus).

This charged imagery culminates in yet another indicative detail. On the left side of the room, the standing Christ extends his left hand to Jairus’ 12-year-old daughter (Figure 8). On a shelf above the resurrected girl, and her parents, is a seven-branched menorah, recalling the menorah of the Second Temple in Jerusalem engraved on the Magdala Stone.29 The menorah has multiple functions in this scenario: first, it identifies the Jewish origins of the place, of the city of Magdala; second, through its similarity to that on the Magdala Stone it contributes to the sense of localization, transferring the house of Jarius from wherever it might have been to ancient Magdala, at least in the pilgrim’s experience; and third, it is a pronounced allusion to the political complexity of the realities of the Holy Land among the different ethnic, religious, and national entities.

Figure 8.

Detail:Talitha qum with Menorah (photo: Assaf Pinkus).

The opposite chapel, in the southwest, depicts Christ Driving Out the Seven Demons from Mary Magdalene (Figure 9). Standing on two flat rocks against a barren mountainous background, Christ is pointing toward Mary Magdalene. Local flora, such as olive trees, a palm, the agave plant, and several flowers, suggest a rather conventional symbolism. Uniquely, an amaryllis flower is featured in the middle of the composition. Bearing a close similarity in its form to the Marian lily, yet colored in a deep red symbolizing fleshly passion, it perfectly illustrates the dual nature of Mary Magdalene: sanctity and sin (Mozley and Mozley 1852, pp. 45, 120). The red color of the amaryllis also recalls the unique coloring of Christ’s robe, suggesting the union (in spirit) of the two protagonists. Deep in the mountains to the left are several tiny colorful cubic houses, similar to the houses along the market street in the mosaic depicting the resurrection of Jairus’ daughter. Consequently, the suggestive transposition of the resurrection of Jairus’ daughter to Magdala—the city of Mary Magdalene where, one may assume, her exorcism had taken place—is completed and becomes almost explicit. Although the visual similarity is controversial, it is worth noting that Father Solana, the conceptualizer of the entire site, links the hands of God and Adam in the painting of the Creation of Man by Michelangelo in the Sistine Chapel, to the hands of Jesus and Mary in Magdala. In the Sistine Chapel, claims Father Solana, it is the creation of man; and in Magdala it is the recreation of woman because Jesus is giving her new life (García 2016, p. 194).

Figure 9.

Christ driving out the seven demons from Mary Magdalene (photo: Assaf Pinkus).

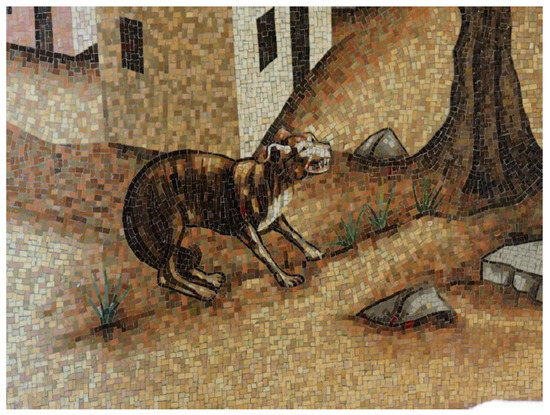

In this mosaic too, Mary Magdalene is dressed in a long brown robe with torn edges, an allusion to her life as a hermit, according to a western apocryphal legend.30 The pink scarf that covers her head reveals a little of her light brown hair.31 Father Solana sees the transformation of this article of the Magdalene’s clothing from a ragged brown to a bright pink as a symbol of the new woman arising from the redemptive power of Christ (García 2016, p. 94). Her left hand is stretched out towards Jesus while around her right hand, resting on her chest, is coiled the tail of a serpent, one of the seven demons expelled from her body by Christ. The serpent continues to twist on the olive tree on the left, with its head facing downwards. Six other demons are depicted as small black devils jumping from the Magdalene’s left side, with their hands spread upward. Uniquely added to this scene is an image of a dog on the bottom left, barking and baring its teeth at the occurrence (Figure 10). The dog is both threatening (barking) and frightened (hiding its tail between its legs). Following a medieval exegesis of Psalm 22 (“For dogs have compassed me; the assembly of the wicked have enclosed me; they pierced my hands and my feet”), barking dogs came to symbolize the Jews attacking Christ and leading to his Crucifixion.32 In Renaissance art, a barking dog, also became an attribute of Judas, symbolizing infidelity and treachery (Cohen 2008, pp. 136–41; Marrow 1977, p. 194). Could this unique supplement to the story, and one that appears nowhere else, also bear political connotations, similar to the girl with the urn in the “Talitha qum” mosaic? Be that as it may, the choice of the topic of Christ expelling demons from the body of Mary Magdalene is in itself a rather peculiar episode from the life of the saint, rarely illustrated in ecclesiastical art.33 According to Father Solana, since this event is the only occasion recounted in the New Testament in which Mary is called ‘Magdalene’, i.e., from Magdala, it bears a central meaning for the worship center;34 and suggests its authenticity.

Figure 10.

Detail: Barking Dog.

Proceeding eastward, to the right, the southeastern chapel (called the Walking on Water Chapel) is adorned with a mosaic depicting Christ Calming the Storm (Matthew 14: 30). The mosaic is divided horizontally into two parts: a stormy sea in the lower part and an open sky above (Figure 11). A low mountain range borders the sea and separates it from the sky. In the stormy Galilee, Christ and Peter are depicted on the right, sinking in the water. Christ is again attired in red and white, his head covered with a white headdress in a fashion that could suggest either a 15th-century headdress or Ottoman fashion (Frick 2006, pp. 158–60; Herald 1981, pp. 211–26). His garment flaps in the wind while he stands calmly, raising his right hand in a gesture of blessing, alluding to his admonition to Peter: “You of little faith, why did you doubt?”

Figure 11.

Christ Calming the Storm (photo: Assaf Pinkus).

To the left, five disciples are rocking in their small fisherman’s boat on the stormy waters. The wooden boat in the mosaic “pre-prefigures” the main altarpiece in the open rectangular hall (cappella maggiore), constructed as a life-size fishing boat of the same shape and dimensions as the pictorial one. This dissolves the boundaries between art and reality, between history and its reenactment, suggesting that the visitor is actually being absorbed into the space where it really happened. Although this event indeed took place on the Sea of Galilee, it too is not related in the New Testament to any particular shore. The mosaics and the constructed space, however, strongly reverberate the idea that it had all occurred in the very real waters that lie behind the mosaic, using image and nature as memory aids to make the scene come alive for the visitor.

Although the depiction of the stormy nature matches the description in Matthew (14: 24), it is at certain odds with the physical Sea of Galilee behind the wall and window. The foam of the depicted waves seem to be of saltwater, whereas the Sea of Galilee is sweet water. The intense storm accentuates the miraculous event and is quite unlike the weather events that actually occur in the region. The cliffs portrayed around the sea are similarly estranged from the physical ones behind the building; and, whereas the actual Golan Heights rise to 1126 m, in the mosaics the mountain chain is rather gentle and low. The visitor is hence in the Sea of Galilee, but not the current one: it is a mystical landscape of either ancient biblical times or of eschatological ones; not of the here and now. The entire scene is circumscribed by the chain of mountains against a background of blue sky whose hue indicates the period of just before dawn, as described in Matthew (14: 25). This specific moment, the moment of spiritual renovation, shortly before sunrise, is the perfect backdrop for entering the Boat Chapel.

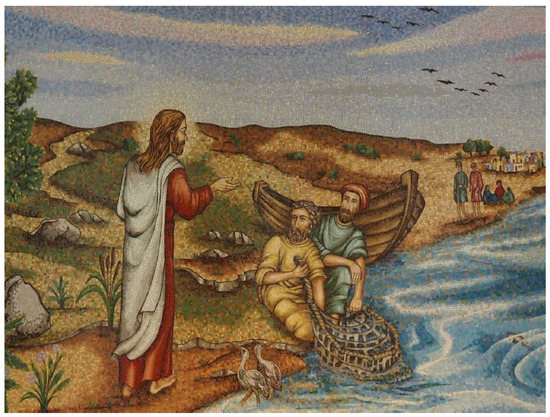

The other metaphorical “gateway” to the Boat Chapel is the last lateral chapel, the Fisher of Men Chapel, with a mosaic depicting the Calling of the Disciples Peter and Andrew on the Sea of Galilee (Matthew 4: 18). The foreground of the mosaic depicts Jesus on the left together with Peter and his brother Andrew on the shore of the Sea of Galilee (Figure 12). They appear against its landscape, a rocky mountainous background with an olive tree, local vegetation, a group of colorful buildings, and two boats in the sea. Christ is addressing Peter and Andrew, who are sitting on the shore casting a fishing net into the lake. Both look towards Jesus. This is the moment when Jesus tells them “Come, follow me, and I will send you out to fish for people.” Between Jesus and the two brothers are two coastal birds (possibly local herons). Two men attired in short tunics and hats are approaching the saints, while three other male figures are seated on the ground, recalling the gamblers who play for the tunic of Christ. The small village of cubic houses featured in the back, similar to the structures in the exorcism scene, is again a reference to 19th-century Arab-Palestine villages. Whereas this portrayal bestows upon the scene a local authenticity, the choice of this specific style of building, rather than Roman architecture that would more aptly fit the historical circumstances, is puzzling.

Figure 12.

The Calling of Peter and Andreas (photo: Assaf Pinkus).

6. The ‘Boat Chapel’: Duc in Altum’s Cappella Maggiore

The Boat Chapel to the east is the main place of congregation and liturgical ceremony and is the grand final of the entire complex, both in terms of devotional ecstasy and in the dimensions of the space (Figure 13). The vaulted concrete ceiling of the chapel is designed in the shape of an inverted wooden boat, containing an altarpiece in the form of a sailboat. This matryoshka-like structure brings to mind such medieval devotional objects as the Shrine Madonnas, which would house additional homologous images inside them (Gertsman 2015; Pinkus 2012). Twelve side pillars in the chapel feature wall icons, paintings of the Twelve Disciples made by the artist Gerardo Zenteno.35 The Disciples appear against a background of golden lightning, as if a pseudo-Byzantine mosaic has been reincarnated through modern-day technology. The figures are drawn in an eastern style more associated with Orthodox icons than with a Catholic church space. The chapel resonates a universal visual spectrum (in the sense of incorporating both Eastern and Western Churches), as well as that of the early Byzantine relics often incorporated into Catholic sites in the Holy Land to stress their ancient roots. Each of the Disciples is identified by a gold-filled inscription, other than Judas Iscariot, who is included amongst the twelve but marked by the lack of gold in his inscribed name and his fallen gaze. According to Father Solana,36 since the decoration on the walls was meant to truthfully reflect the episodes of Christ’s ministry, and since Judas at that time was still one of the Disciples, he decided to include his portrayal, but with denigrating signs: no halo, a downcast gaze rather than a straight one, and holding the moneybag.

Figure 13.

The Boat Chapel (photo: Assaf Pinkus).

The apse is oriented eastwards, to the shore of the Sea of Galilee, and its altar is a unique and site-specific piece, featuring a fishing sailboat with a mast and furled sail. The connection between the chapel interior and the Galilee landscape beyond is emphasized by various visual and material means. The boat is set in front of grand transparent glass windows that look out onto the sea. Beyond the windows is an artificial pool of water that surrounds the entire chapel and visually merges with the waters of the Sea of Galilee. The boat-altar rests atop a platform and stairs of imported green-blue Carrera marble whose streaks suggest waves and create a dynamism of light and color evocative of deep water. Consequently, the boat-altar appears to be floating on the surface of water. The art and architecture blur the boundaries between the different materials (stone and water), between the interior and the exterior (a boat inside and the sea and water-pool outside), and between natural and artificial water sources. The shapes of the ceiling beams are reminiscent of ship-bottoms, strengthening a sense of the conveners being in a boat, looking at a boat, gazing out towards a sea that has found its way visually into the space. This visual emphasis is coupled by a textual emphasis on Christ’s preaching from a boat in the Sea of Galilee. The clergy in this space of worship assume their position behind the boat-altar, simulating the situation of preaching from the boat, with the real Galilee in the background, manifesting Father Solana’s testimony: “The boat which I had been dreaming about for a long time, from where I could preach on the seashore, as Jesus had done in His time, to the pilgrims who come from all over the world…” (García 2016, p. 92). Hence, the spiritual transformation is not only the transformation of the site into the place where it had all happened, but the preacher himself, as Christ’s follower, conveys the transformational experience for the devoted pilgrims, as past, present, and future collapse into each other, and identities become united.37

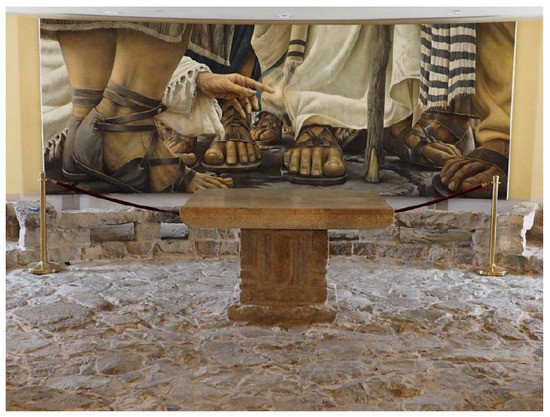

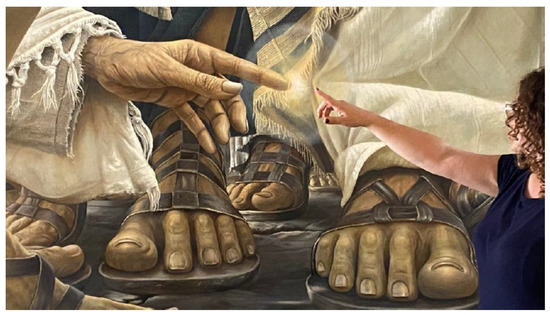

7. The “Encounter Chapel”: Stepping into the Past and onto the Past

A staircase to the south of the Women’s Atrium leads to a lower level in the church, constructed as a “grotto” (rather than a crypt), dedicated to Christ’s encounter with the woman with a running issue of blood, (zava), and who touched the lapels of Christ’s garment and was healed (Mark 5: 25–29). This choice of a miraculous event related to a woman seems deliberate and in direct continuation of the themes of two of the lateral chapel mosaics, depicting the resurrection of Jairus’ daughter and Jesus casting the seven demons out of Mary Magdalene.

The grotto is built on the archeological site of Magdala’s harbor and commercial zone, with the floor of the chapel incorporating the ancient pavement. The archeological findings have been reconstructed into an image of a study room in the ancient synagogue in the center of the archeological park outside. Moreover, in the reconstruction of the space, benches that imitate the shape of those found in the dig have been installed along the walls, completing the transformation of the room from a harbor into an imaginative prayer room. The reconstruction of the benches from local rough-cut stone intensifies the authentic aura of this fabricated synagogue-space (Figure 14). It equips the visitors with every visual aid necessary to complete the internal journey back in time, and to envision themselves walking along the streets of Magdala in the days of Christ’s ministry, and even to imagine that (like the woman with the “issue of blood”) they might encounter Jesus by chance in the market place and reach out to touch the lapels of his robe.

Figure 14.

The “grotto” with the mock-antique benches (photo: Assaf Pinkus).

To support such an imagined moment of contemplation of the past, the room is dominated by a large hyper-realistic painting behind the altar of the encounter of Christ with the bleeding woman (Figure 15). The painting presents a close-up of several pairs of feet in sandals and the bottom of some simple woven garments. A single hand reaches out to touch what looks like the bottom of a Jewish prayer shawl (talit). The outstretched hand, like the feet, is at least a dozen times larger than life-size. The painting keeps the viewer’s gaze at foot-height, a dwarf’s perspective beneath the feet of the giants of a meaningful past. The diagonal angle of the hand, along with a ring of light at its point of contact with the fabric, suggests an electric dynamism—a magical and transient moment. One can almost imagine the feet moving forward, the sharp light diminished and the hand drawn back, transformed by the magical moment of contact with the divine. The focus on the contemporary image is highlighted by the stark simplicity of the empty room, whose architectural details (paving and mock-antique benches) speak to other times.

Figure 15.

Jesus and the Bleeding Woman, grotto of Duc in Altum (photo: Assaf Pinkus).

Like the other scenes localized visually in Duc in Altum, this New Testament event is not reported as occurring in Magdala. Unlike the mosaics of the four lateral chapels, each portraying a complete scenario or narrative, the hyper-realistic fresco depicting the encounter constitutes a fragmentary, almost fetishist close-up. The scene is historicized through the style of the sandals and clothing, but the visual language and compositional choice are fully contemporary, even cinematic. As the hand reaches out from the left to touch the robe, it manifests like a cinematic zoom-in on the moment at which the bleeding woman dares to reach out and touch Christ’s garment. The composition of the image is centered around the ray of light shining from that hand, inviting the visitor to occupy the place of the bleeding women, reach out themselves, and imagine virtually being granted the miraculous touch of Christ. It embodies a unique moment with an innovative new iconography, focusing only on the hand of the bleeding women as it draws the miracle from Christ, who is unaware at first of her bold deed. She has defied the Jewish prohibition against touching men during the time of a woman’s bleeding,38 and instead followed her own belief. The painting thus encourages the devotees not only to physically take the place of the bleeding women but also to follow their individual beliefs and work miracles of their own.

Even more significant than the religious experience of the painting, is its novel visual manipulation. The painting is constructed and orchestrated not so much for the devotees as for their cellular cameras. When standing in front of Christ’s hands, the visitor becomes part of the image—but this optical illusion is incarnated and discernable only through the lens of the modern photographic medium, as a souvenir to take home after the pilgrimage is completed (Figure 16). The hyper-realistic painting, combined with an extremely illusionistic and technical device that dissolves the boundaries between art and the devotees, engenders an extremely sensual encounter. It is the only artwork in Duc in Altum bearing neither inscription nor citation from the New Testament. This is not accidental, as it is not the past that is being depicted, but the here and now of the devotees’ own time.

Figure 16.

The fresco with visitor, moment of “encounter” enacted using cellular camera (photo: Assaf Pinkus).

8. Reinventing Magdala: Between Estrangement and Authentication

The vibrant and active pilgrimage site of Duc in Altum connects to a long Holy Land tradition of highlighting possibilities for the viewers without committing to historical accuracy. Here, the experience is framed within highly creative architectural spaces that simultaneously combine a contemporary visual language and materials with a spectrum of adopted styles mixed and matched as needed to create a maximum potential for experience. One of the means for such experience is that of blurring the boundaries between the archaeological and the newly-made. Where does the archaeologically-excavated floor end and the new additions to it begin? Which benches at the site are 1th century and which are 21st? The same is true for the Magdala Stone: three stones, one original (perhaps) and two copies, are on display in various places in the hotel and at the archeological site, yet none bear evidence regarding which is the authentic one. By blurring the boundaries between the historical and the suggested, the conceptualizer of Duc in Altum has succeeded to create a space of possibilities and suggestions. Without claiming that any specific miracle had truly occurred at that specific site, it manages nonetheless to bring them all into a shared umbrella of potentials—they intimate it. These are constantly connected to the local fabric: elements from the excavation (original and newly-made to match); views of the landscape and especially the Galilee; but also completion of that landscape with artistic elements that blur even the boundaries between materials like the marble ‘waves’ beneath the boat-altar and the mosaic mountains, which in most cases mirror the real mountains behind them, functioning like a ‘window’ into the Galilee environment despite the fully opaque walls. The imitation mosaic ‘windows’ included within that landscape offer imaginative details that organize past and present, space and narrative—whether claiming authenticity or providing opportunity for the imagination. This visual stratagem comprises a triple move:

Site Specificity. Regarding the pictorial program of Magdala as a whole, this center of worship is aptly designed to visually manifest the universal claims of the site, combining artistic characteristics of both the Eastern and Western worlds, fused with local nuances and novel iconography (such as that of the Women’s Atrium) that suit the specific terms and circumstances of Magdala. This, however, is just part of the larger mechanism and strategy employed to create a new reality for Duc in Altum. As already mentioned, none of the biblical events incarnated in pigment, glass, and stone are actually known to have happened in Magdala itself. Although they all took place around the Sea of Galilee, and although nowhere in Duc in Altum is it stated that the events indeed occurred in Magdala, the power of visual suggestion manifests strongly. For the pilgrim (but also for every other visitor), the accumulation of site-specific characteristics subconsciously associates the events with Magdala’s locale. However, this is a specific locale that is concomitantly self-referentially site-specific, estranged from its immediate environment, and devised as distinct from its setting in modern-day Israel. This is achieved not only through the iconographic details, as detailed above, but also through a dialectic play between estrangement and authentication. This modern model of concurrent estrangement and authentication would appear to be a recurring theme in the architecture around the Galilee today.

Calculated Estrangement. The architectural models chosen for this holy site mark them as different from the local Israeli-Palestine contemporary architecture, as well as from the 19th to mid-20th century Christian buildings in the Holy Land, which have adopted individual national styles (discussed below). In Magdala, the architectural models are drawn from various elements of both Byzantine and medieval Western traditions. Contrary to these universal, rather than global, trends however, they are not responsive to local trends of architecture and foreign to the surrounding architectonic landscape.39 Notwithstanding, although completely at odds with the local building styles, Duc in Altum as a whole is transparent to the natural environment and its decoration is an extension of the Sea of Galilee and Mount Arbel. An additional strategy employed by its designers is that of stylistic and artistic estrangement: namely, the use of artistic models, media, and materials imported to the Holy Land from abroad, but generally not created using local materials or by local artists, save for the architecture carried out by the Nazareth firm of Nakhla architects. None of the materials used for the decorations are of local origin. The mosaics, for example, are made from luxurious Murano glass. Whereas nowadays this prestigious “Venetian” glassware is mostly being produced in China, for the Magdala project it was ordered from the Italian manufacturer. Moreover, the landscape featured in the mosaics has nothing to do with Israeli or Palestinian artistic trends, or with contemporary geography. Even the depictions of the Sea of Galilee itself are based on imported models or biblical descriptions and not on empiric observations. The same is true of the biblical villages depicted in the mosaics—these are mostly based on Orientalist painting or on real pre-1948 Palestine villages in the Holy Land (such as the Arab village Al-Majdal mentioned above) and not on modern local settlements. The visitors thus find themselves in an imaginary new Holy Land. Consequently, they no longer stand on the ground of a political conflict, but rather on holy-mystical ground, and are transported from the here and now to the two other poles of time: the past, and the eschatological time of salvation.

Staged Authenticity. Most crucially, in order to function successfully as a center of worship, the site must be conceived by its visitors as authentic. Several strategies are deployed in order to achieve this goal, the most prominent of which is that of visualizing historical continuity. In contrast to the above-noted strategies of estrangement, the mosaics and painting promote a sense of authenticity by means of a fabricated historical continuity.40 Based on archeological excavations, and bringing certain aspects of these back to life in the mosaics, it is through the visual properties of the pictorial program and site-specific details that the site raises a strong claim to historical authenticity. At the same time, this sense of (imagined) authenticity enabled the iconographer of the program to shape consciousness and relocate or transfer all the depicted biblical events to Magdala. The most illustrative examples are Magdala’s synagogue and the pool for salting fishes reincarnated in the Raising of Jairus’ daughter scene. These and other details have been recruited in order to visually reassure the pilgrims to the site regarding its history and fidelity, highlighting that these were indeed the ancient places of Christian faith, where Jesus and the disciples had acted. These details confirm that the imaginary Magdala—and by extension the new Holy Land around the Sea of Galilee being built in these very days—indeed existed and still does. The visitor is thereby unable to differentiate between the real archeological truth of the site and the reconstructed one. The site, as noted above, exhibits in three different places the Magdala Stone and two copies of it, which cannot be differentiated from each other by non-specialists. In this way, the historical background of the place is present everywhere and the authenticity of the site is enhanced. The question of which one is the original stone becomes redundant. It is an authenticity that remains unquestioned.

This is reinforced by the visual and artistic site-specificity: each painting and object is related directly to the site and the event that it commemorates and can thus only be exhibited there; at any other sites these artefacts would lose their powerful meaning, such as the monumental altar designed as a full-scale ‘boat’ for the apse at Magdala. The altar is encircled by water on all sides: it stands on “marbleized” water, surrounded by a decorative pool outside the apse and around its windows. All this functions as a prelude to the waters of the Sea of Galilee seen through the wall of windows of the apse. This visual rhetoric and topic present a unique manifestation that can only be meaningful at this specific site. In order to support the claim of fictive authenticity, the conceptualizers of the site have recruited the archeological findings, again in a half-authentic and half-imaginative way. The majority of the holy places in the Holy Land, including at the Sea of Galilee, have been erected above archeological excavations either of Early-Christian or Late-Antiquity-Jewish sites (not necessarily sacred), leaving their remains visible (e.g., through a transparent floor, such as in St. Peter’s Church in Capernaum), and hence emphasizing historical continuity. In the mock-grotto of Duc in Altum, the ancient market of Magdala is reconstructed as a synagogue, leaving the visitor with no clue regarding which part of the archeological space is authentic and which is fabricated. Finally, in order to bestow upon the site a further sense of historicity, the designer has used pseudo-spolia: the boat altar, for example, reproduces the 5th-century mosaics of the loaves from the nearby village Tabgha, embedded in the altar in the tradition of medieval spolia.

These visual properties in the Duc in Altum worship center are paradigmatic to the strategies that we have discerned in the making of a (new) Holy Land within the (old) Holy Land. This expropriation of the space from its natural environment and the making of a “micro” Holy Land is being accomplished in two dialectically opposing stages—of estrangement and of authentication/site-specificity. We have noted three main dialectical moves: architectural and artistic estrangement (which leads also to environmental estrangement); fabrication of historical continuity and authenticity; and site-specific installations.

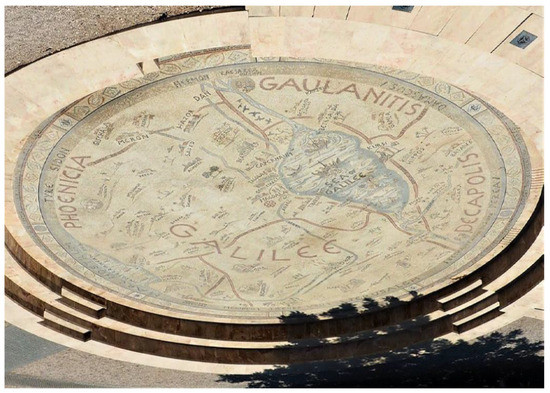

Using various visual strategies, from site-specific artworks to suggestive-imaginative details, estrangement and authentication, Duc in Altum has gradually transitioned into a place with historical implications and possibilities: this could have been the place of the raising of Jairus’ daughter, of the calming of the storm, of the calling of the Apostles, and the healing of the bleeding women; and this is where Mary, from Magdala, could have been healed in the town of her origin. The focus on the ministry of Christ is also a strong tool for differentiating the area around the Galilee from that of Jerusalem of the Passion, Bethlehem of the Nativity, and Nazareth of the Annunciation. If Bethlehem and Nazareth are where it all began and Jerusalem is where it came to a tragic but ultimately victorious end—the Galilee is where it all happened. A metonym for the strategy as a whole is found in a mosaic preceding the entrance to the Duc in Altum worship center (Figure 17).

Figure 17.

Map of the Galilee as a micro-Holy Land (photo: Assaf Pinkus).

The mosaic, set into the floor northwest of the worship center, features a map of the newly conceptualized Holy Land, in the tradition of medieval cartography. Visually drawn from such mosaics as the Madaba map, the mosaic depicts the entire religious establishment of the region, with the Sea of Galilee occupying its “umbilicus”, replacing the traditional medieval maps with Jerusalem at the center. The ancient city of Magdala, where Duc in Altum is established, is located at the center of the round mosaic, marked out by a rosette that amplifies its significance. Arrows point outwards to indicate other locations outside the map, including Jerusalem, Sidon, Bethany, and Tyre, each represented solely by an understated name in gray. The sites around the Galilee, in contrast, are highlighted with miniature architecture, narrative scenes from the New Testament in and around the lake’s waters, and representations of the flora and fauna of the area. Thus, Kursi, Hamat Tiberia, the Mount of Beatitudes, Tabgha, Capernaum and, above all, Magdala at the center, become the main loci in what reads as a ‘zoom-in’ image of an area of major and independent importance in the Holy Land, able to stand alone as a defined unit. More intriguing still, the map is merely a model for a larger mosaic, 114 m in diameter;41 through which one can reflect on the dimensions and programmatic character of this ambitious project. The mosaic image is a signifier of a wider phenomenon of denotation of the Galilee and its surroundings as a microcosm of the Holy Land and a Holy Land in and of itself. Constituting a landmark of this ongoing process that began in 1969 with the declarative architecture and decoration of the Basilica of the Annunciation in Nazareth, the Duc in Altum, is nevertheless, merely a temporary zenith that will soon be transcended by new projects, being conceptualized at this very moment.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.P.; methodology, N.B.; formal analysis, E.S.; investigation, A.P., N.B. and E.S.; writing—original draft preparation, A.P., N.B. and E.S.; writing—review and editing, A.P., N.B. and E.S.; project administration, E.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Notes

| 1 | We wish to warmly thank Father Juan Solana for the enriching interview with him on site, the Duc in Altum publications and kind hospitality. We also thank our research assistant Hadas Gabay as well as the Open University and Tel Aviv University’s internal research funding scheme. The sole monograph anthology of the current building of the Church of the Annunciation at Nazareth is by (Segal et al. 2020). On the conceptualization of the architectural design for the church, see (Irace 2020, pp. 95–105). |

| 2 | On the different plans and phases of the Church of the Annunciation in Nazareth, see: (Halevi 2010). |

| 3 | The renewal of the pilgrimage site and the creation of modern religious architcture in Nazareth and the area was not only the interest of the Christian community but also an Israeli one, see: (Simhony 2020; Neuman forthcoming). |

| 4 | The new building also spearheaded a new type of pilgrimage experience (Segal et al. 2020). |

| 5 | Although archaeological and textual evidence point to continuous pilgrimage to several sites on Sea of Galilee from the fourth to at least the fourteenth century. The new foundations in the nineteenth to twenty-first centuries mark a divergence from this traditional rituas. More importantly, some of the events marked in the new sites do not have medieval roots. It is beyond the scope of the present article to discuss this tradition. For further details of the pilgrimage circuits in the holy land in the Middle Ages and medieval maps of the Holy Land see (Arad 2020). On Christian pilgrimage to the Galilee during the Crusader period. See: (Prawer 1986, pp. 31–62, especially 34). For a seminal reading of the anthropological perspective on Christian pilgrimage, see: (Turner and Turner 1978). |

| 6 | See the discussion below. The developments are not exclusively Christian: the renovation of the Church of the Annunciation also influenced Jewish religious architecture in the region. See: (Simhony 2020). |

| 7 | On the different plans and phases of the Church of the Annunciation in Nazareth, see: (Halevi 2010). |

| 8 | For the different opinions regarding the attribution of the name Magdala to the site, see: (Taylor 2014). The article claims there is no place called Magdala in the earliest manuscripts of the New Testament. The sites called Magdala in Israel today continues a Byzantine identification, from the 5th or 6th century CE (at page 205). |

| 9 | The report on the excavation campaign by two teams, Israeli and Mexican, is: (Zapata-Meza et al. 2018). |

| 10 | Both publications on the Duc in Altum center were commissioned by the site itself, see (de la Garza 2020; García 2016, p. 194). |

| 11 | On the influence of the establishment of the State of Israel and of the Second Vatican Council and Jewish and Christian architecture in Nazareth and beyond, see: (Simhony 2020). On the influence of the Second Vatican Council on the architecture at Nazareth, see: (Longhi 2020, pp. 69–94). |

| 12 | Tracking the specific actors (their narratives and intentions) of each site is the goal of our onging study. To uncover and analyze these there are additional interviews with each ecclesiastic authority that remain to be analyzed, This is, however, beyond the scope of the present article. |

| 13 | Two exceptions are: (Simhony 2020; Halevi 2007). |

| 14 | For example: (Feldman 2007; Keshman 2019). |

| 15 | Such as the Church of the Visitation in Ein Karem (Kenaan-Kedar 2009, pp. 52–83); Augusta Victoria Hospice on the Mount of Olives, (Arad 2005b; Peled 2016). Several dissertations have been dedicated to certain individual artefacts or churches and monasteries in Jerusalem or its environs, such as the iconostasis of St. George Church in Lod, see (Traister 2009); the 19th-century decoration of the Church of Saint George in Ramla, see (Levy 2014); Beit Jimal Monastery and its wall paintings, see (Shalev-Khalifa 2010); and the Church of All Nations on the Mount of Olives in Jerusalem, see (Halevi 2014). Additional projects have sought to look at clusters of churches and discern possible patterns, most prominently a work in progress by Bianca Kühnel and Anastasia Keshman on contemporary ecclesiastic art around Jerusalem (not yet published); studies by Masha Halevi on the churches by Antonio Barluzzi (Halevi 2012a, 2012b); Lily Arad on the compounds founded by Kaiser Wilhelm II, (Arad 2005a). |

| 16 | (Fishhof 2020, pp. 39–52). For the most comprehensive standard work on the capital, see (Folda 1986). |

| 17 | The Magdala Stone is sculpted with what has been interpreted as a contemporary and even eye-witnessing depiction of the Herodian Temple, including the menorah with the seven reeds inside it. For a consideration of the holistic analysis of the stone, see: (Aviam 2013, pp. 205–20; Fine 2017). The exact use of the stone is under debate by archaeologists; it might have been used as a ceremonial item on which the Torah and other sacred scrolls were placed. For the points of contention among scholars, see: (Gurevich 2018). |

| 18 | For a summary of the finds in both the southern and the northern parts of the excavation in the area, see: (Bauckham and De Luca 2015). |

| 19 | The construction of the center and the motivation behind this endeavor is documented in the book by Jesús García, The Magdala Project. This source, however, should be read with caution, as it is more of a spiritual-political manifesto than an archival record of the process. |

| 20 | Conversation conducted at the site on the 2 August 2022. |

| 21 | (García 2016, p. 264). The Magdala Project also promises to establish an International Center for Women, conferences, courses, workshops and special programs ‘dedicated to the propagation of the Christian concept of women’. Ibid., 212. |

| 22 | (The Holy 1963). See especially chapter II, clauses 54, 63, chapter 4 clause 2 and 83. |

| 23 | On the Virgin of Guadalupe, see: (Gómes-Barris and Irazábal 2010; Napolitano 2009). |

| 24 | Conversation held at the site on 2 August 2022. |

| 25 | Conversation held at the site on 2 August 2022. |

| 26 | Another detail hints at the religious significance of the place: a vine is planted in front of the house, symbolizing the blood of Christ and referencing the Eucharist. |

| 27 | On evidence regarding the urban center at Taricheae, see: (Aviam 2013, pp. 205–10). |

| 28 | This image symbolizing life in the Eastern-Mediterranean region is already known in paintings of Christian manuscripts, such as the 6th-century “Vienna Genesis”, through 19th-century paintings of biblical stories by Gustave Doré, to photographs of Arab and Hebrew women in the 20th century. |

| 29 | According to Aviam, the appearance of the menorah in a synagogue dated to the Second Temple period is unique. The menorah on the stone symbolized the Temple and the author suggests that all the other decorative elements are also symbolic. (Aviam 2013, p. 208). According to Fine, the motif was already embedded in the local visual language by the time of this period. (Fine 2017, pp. 28–29). |

| 30 | (King 2003). About the various traditions regarding Mary Magdalene see also: (Haskins 1995). |

| 31 | This attire is reminiscent of the famous Donatello wooden sculpture of the saint, 1453–1455, that inaugurated this visual tradition. (Avery 1991, pp. 130–31). |

| 32 | The dog can also represent fidelity in Christian art but this would be at odds with the barking dog at Magdala, see (Cornwell and Cornwell 2009, p. 121; Ferguson 1961, p. 15). |

| 33 | For an iconographical overview, see (Anstett-Janssen 2004, pp. 515–41). |

| 34 | According to Taylor this was a name that marked Mary as an Apostle of Christ rather than the name of her town of origin. See (Taylor 2014, p. 206). |

| 35 | Conversation held at the site on 2 August 2022. |

| 36 | Conversation held at the site on 2 August 2022. |

| 37 | This is precisely the pilgrim’s experience described in the seminal works by (Eliade 1971). |

| 38 | See Leviticus 15: 1 on the male with a discharge (zav) and Leviticus 15: 25–30 on a woman with a discharge. Specifically, anyone who touches her contracts impurity: “When a woman has a discharge of blood for many days at a time other than her monthly period or has a discharge that continues beyond her period, she will be unclean as long as she has the discharge… Anyone who touches them will be unclean” (Leviticus 15: 25–27). |

| 39 | It cannot be considered as global, as it ignores current architectural developments and the new artistic articulations of many Christian communities such as those of Africa and Asia; rather, it adheres to the Western colonialist tradition. |

| 40 | Steven Fine has commented on the long tradition of fabricated connections (as he defines them) between text and locale in Jewish and Christian architecture since Late Antiquity, see (Fine 2017, p. 29). |

| 41 | https://www.magdala.org/magdala-mosaic-family (accessed on 8 July 2021). |

References

- Anstett-Janssen, Marga. 2004. Maria Magdalena. In Lexikon der christlichen Ikonographie 7. Edited by Wolgang Braunfelds. Freiburg: Herder. [Google Scholar]

- Arad, Lily. 2005a. Perception and Action in Kaiser Wilhelm II’s Concept of Jerusalem. Jerusalem: Konrad-Adenauer-Stiftung. Jerusalem: Helmut Kohl Institute for European Studies. [Google Scholar]

- Arad, Lily. 2005b. The Augusta Victoria Hospice on the Mount of Olives and Kaiser Wilhelm II’s Peacefull Crusade. Jahrbuch des Deutschen Evangelischen Instituts für Altertumswissenschaft des Heiligen Landes 9: 126–47. [Google Scholar]

- Arad, Pnina. 2020. Christian Maps of the Holy Land: Images and Meaning. Turnhout: Brepols. [Google Scholar]

- Avery, Charles. 1991. Donatello: Catalogo Completo delle Opera. Firenze: Cantini. [Google Scholar]

- Aviam, Mordechai. 2013. The Decorated Stone from the Synagogue at Migdal, A Holistic Interpratation and a Glimpse into the Life of Galilean Jews at the Time of Jesus. Novum Testamentum 55: 205–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bauckham, Richard, and Stefano De Luca. 2015. Magdala as We Now Know It. Early Christianity 6: 91–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowman, Glenn. 1991. Christian Ideology and the Image of the Holy Land. The Place of Jerusalem Pilgrimage in the Various Christianities. In Contesting the Sacred: The Anthropology of Christian Pilgrimage. Edited by John Eade and Michael J. Sallnow. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Bowman, Glenn. 1993. Nationalizing the Sacred: Shrines and Shifting Identities in the Israeli-Occupied Territories. Man 28: 431–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brock, Ann Graham. 2003. Mary Magdalene, the First Apostle: The Struggle for Authority. Harvard Theological Studies 51. Cambridge: Harvard Divinity School. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen, Simona. 2008. Animals as Disguised Symbols in Renaissance Art. Leiden: Brill. [Google Scholar]

- Cornwell, Hilarie, and James Cornwell. 2009. Saints, Signs, and Symbols. Harrisburg: Morehouse Pub. [Google Scholar]

- de la Garza, Rodolfo. 2020. Magdala una Obra Para Contarse. Mexico: Primera Edición. [Google Scholar]

- Desramaut, Francis. 1986. L’Ophelinat Jésus-adolescent de Nazareth en Galilée: Au temps des turcs, puis des anglais (1896–1948). Rome: Libreria Ateneo. [Google Scholar]

- Dumper, Michael. 2002. The Politics of Sacred Space: The Old City of Jerusalem in the Middle East Conflict. Boulder: Lynne Rienner. [Google Scholar]

- Eliade, Mircea. 1971. The Myth of the Eternal Return: Cosmos and History. Translated by Willard R. Trask. Princeton: Princeton University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Feldman, Jackie. 2007. Constructing a Shared Bible Land: Jewish-Israeli Guiding Performances for Protestant Pilgrims. American Ethnologist 48: 348–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferguson, George. 1961. Signs & Symbols in Christian Art. London and New York: Oxford University Press, vol. 164. [Google Scholar]

- Fine, Steven. 2017. From Synagogue Furnishing to Media Event: The Magdala Ashlar. Ars Judaica 13: 27–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fishhof, Gil. 2020. The Sculpted Images of St. Peter and the Virgin in the Crusader Church of the Annunciation: Rival Traditions, Competition for Pilgrims, and Regional Context. In The Basilica of the Annunciation in Nazareth: Where the Word Became Flesh. Berlin and Boston: De Gruyter. [Google Scholar]

- Folda, Jaroslav. 1986. The Nazareth Capitals and the Crusader Shrine of the Annunciation. University Park: Pennsylvania State University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Frick, Carole Collier. 2006. Dressing Renaissance Florence: Families, Fortunes, and Fine Clothing. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press. [Google Scholar]

- García, Jesús. 2016. The Magdala Project: A First Century Discovery for the People of the Third Millennium. Madrid: Gospa Arts. [Google Scholar]

- Gertsman, Elina. 2015. Worlds Within: Opening the Medieval Shrine Madonna. University Park: Pennsylvania State University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Gómes-Barris, Macarena, and Clara Irazábal. 2010. Transnational Meaning of La Virgen de Guadalupe: Religiosity, Space and Culture at Plaza Mexico. Culture and Religion 11: 107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]