2. The Berlin Schaubühne’s Antikenprojekt

It is interesting that the Berlin Schaubühne had never attempted to stage a Greek play before 1974. Considering the theatre’s “proclivity for fundamental and thorough analysis” (

Fischer-Lichte 2017, p. 271), however, it comes as no surprise that the Schaubühne chose

The Bacchae as its first Greek tragedy on stage. During its short life, being founded by Peter Stein in 1970, the Schaubühne was fast becoming the most respected, innovative, and socially conscious theatre in West Germany, known for its social realism and critical stagings of modern plays (

Remshardt 1999, p. 35). As Anton Bierl suggests, in its choice to produce

The Bacchae, “the plan was to research the origins of Western theater and to put the findings into practice” (

Bierl 2016, p. 269).

Under the guidance of Dieter Sturm, then head of dramaturgy for the Schaubühne, the cast prepared meticulously, with members of the group even travelling to Greece in 1973 for a first-hand impression (

Remshardt 1999, p. 35;

Fischer-Lichte 2005, pp. 332–44;

2014, pp. 93–115;

2017, p. 272;

Bierl 2016, p. 270). They studied the literature on ancient Greek theatre, mythology, and rituals, extensively (

Fischer-Lichte 2017, p. 272). They consulted experts and held lengthy discussions reviewing the research of philologists, anthropologists, archaeologists, and historians, the thoroughness of which is amply documented in the dramaturgical protocols and in a voluminous programme book, which amounted to 80 pages (

Remshardt 1999, p. 35;

Fischer-Lichte 2017, p. 272). In concurrence with a growing part of artistic production within the visual arts of the same time, the Schaubühne’s project clearly adopted a research-based approach.

As a result of this research, which took the group beyond what was thought to be known about Greek tragedy, into the unknown and speculative territory of prehistory (

Remshardt 1999, p. 35), they reached the conclusion that the presentation to an audience of a world so alien could not be attempted without an introduction. Therefore, Stein conceived of a two-part production that emphasized its process-oriented nature through its title, called

Antikenprojekt [Antiquity Project]. The first evening, presenting

Exercises for Actors under his direction would serve as a prelude for the production of the second evening,

The Bacchae under the direction of Klaus Michael Grüber. The small Schaubühne building at Hallesches Ufer was deemed inadequate for the

Antiquity Project and a set was created for each performance inside a large exhibition hall at the Berlin fairgrounds, the Philips Pavilion. For Sampatakakis, this displacement was the first political statement made obvious: Greek tragedy was ready for renegotiation under new socioeconomic conditions (

Sampatakakis 2017, p. 200).

The stage for

Exercises for Actors was designed by Karl-Ernst Herrmann. The floor on the hall was covered in soil (

Fischer-Lichte 2017, p. 273). The set clearly manifested the company’s need to “stake out a cultural and historical place from which to perform that first evening of the

Antiquity Project”, beginning metaphorically and figuratively, “at theatrical ground zero” (

Remshardt 1999, p. 35). A large clock hung above the stage and every five minutes the voice of Bruno Ganz—who played Pentheus the following night—announced the time. In juxtaposition to the visual set, this audible element undermined the illusion of regression into archaic ritual forms and a search for origins, thus consistently reflected as a contemporary conceit (

Remshardt 1999, p. 36).

The performance lasted for three hours and consisted of six parts: ‘Beginnings’, ‘The Hunt’ and ‘The Sacrifice’, followed by an intermission which featured a satyr play, and then what looked like an initiation rite. Through its structure,

Exercises for Actors directly referred to Burket’s

Homo Necans and the book’s description of sacrificial rituals and initiation rites in ancient Greece. The first words were spoken at the final part of the evening when a recitation from Aeschylus’

Prometheus Bound marked the transition from

dromena to

legomena.

2 The words spoken anticipated the next evening, the performance of

The Bacchae directed by Grüber; from the mouth of Prometheus, the audience heard: “For humans in the beginning had eyes but saw to no purpose | they had ears but did not hear. | Like the shapes of dreams they dragged through their long lives” (v. 447–449).

3 3. Klaus Michael Grüber’s Die Bakchen and the Visual Arts

For West Berlin theatre critic Stephen Locke, if there was one singular characteristic of Klaus Michael Grüber’s productions, that was “the imaginative utilization of space and sound to create living pictures, environments, suggestive images that beg for—and eschew—specific interpretation” (

Locke 1977, p. 47). After studying in Stuttgart, Grüber became assistant to the director Giorgio Strehler at the Piccolo Teatro di Milano, in 1962. In his book

Anarchie in der Regie? [Anarchy in Directing?], Günther Rühle described Grüber’s style as “the convincing translation of a hermeneutic play into new worlds of images”, and his method as “directing by association” (

Rühle 1982, p. 120). It was often that Grüber described to his associates of a particular scene in terms of a well-known painting (

Locke 1977, p. 47).

As follows,

The Bacchae was a natural choice for Grüber. As a drama that is directly concerned with the notion of spectatorship,

The Bacchae employs a set of theatrical tropes—such as its metatheatricality, the confusion of binaries, and literal and metaphorical dismemberments (

Taxidou 2012, p. 9)—that were central to Grüber’s interests, such as the confrontation with the meaning of identity and the encounter between subjectivity and the world (

Remshardt 1999, p. 43). As Melinda Weinstein suggests, “for the characters in the play, the actors, and the audience, the modality of knowing Dionysus represents in the drama is not-knowing”, disturbing Pentheus’—but not only his—“reliance in the senses for perceiving the truth” (

Weinstein 2008, p. 18).

Grüber’s strategy of establishing a pictorial and symbolic order that was highly associative and created proliferate meanings was coupled with the breaking down of the linearity of the dialogue, resulting in what Erika Fischer-Lichte has named the “dismemberment of the text” (

Fischer-Lichte 2005, p. 231). The linguistic element of the performance became ragged, seemed fragmented and disjoint. Binaries and doubles, like Dionysus and Apollon or Dionysus and Pentheus met, only to fall apart again immediately. The ruling tone was one of disorder, rupture, and fracture, of scattering and detachment. Meaning was lost in either language or vision, there was no recognition of past and present (

Bierl 2016, pp. 271–72). Indeed, the idea of doubling seemed to have been translated by Grüber into a four-hour long intertextual, intermedial play between the text, the performance on stage, and the visual arts.

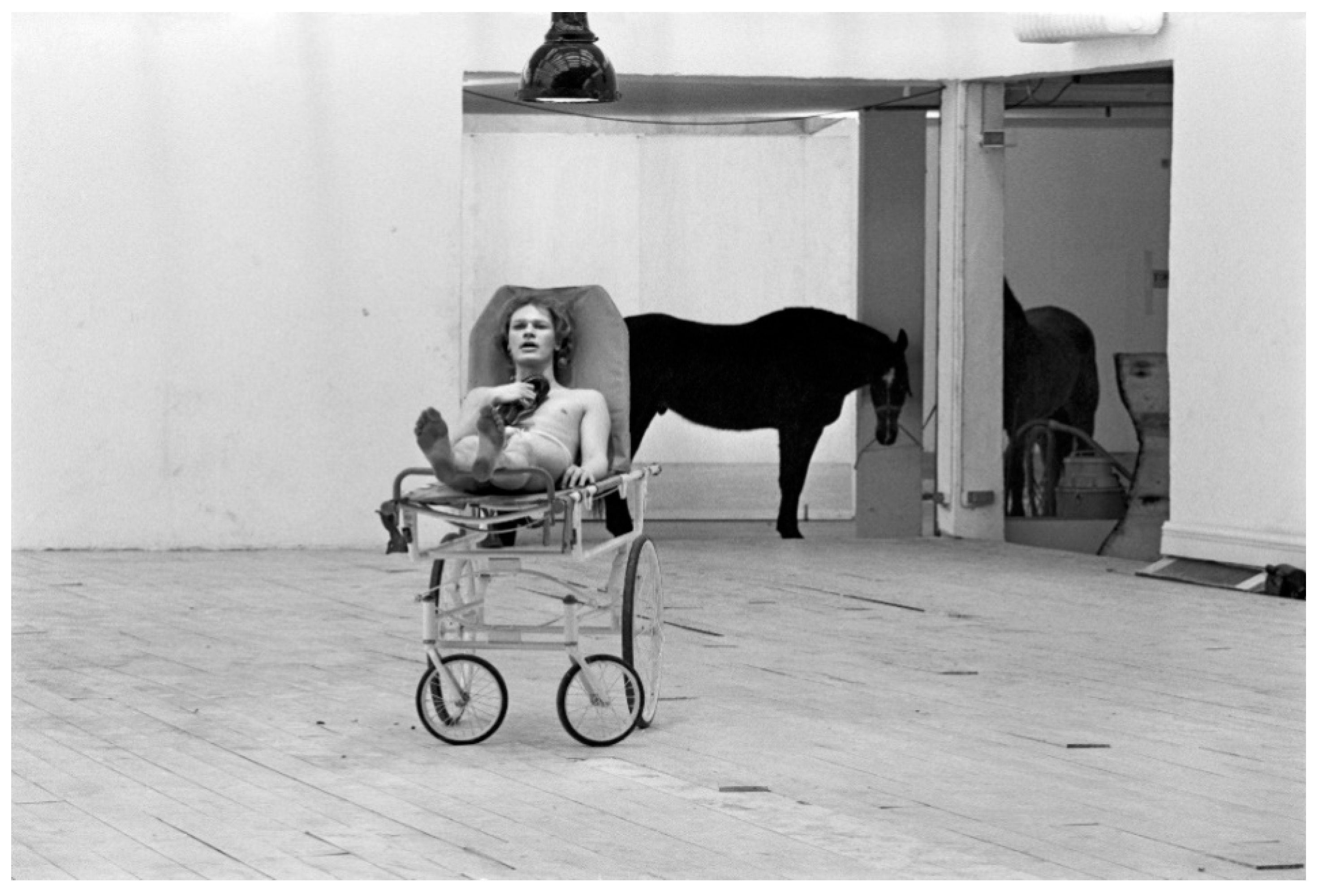

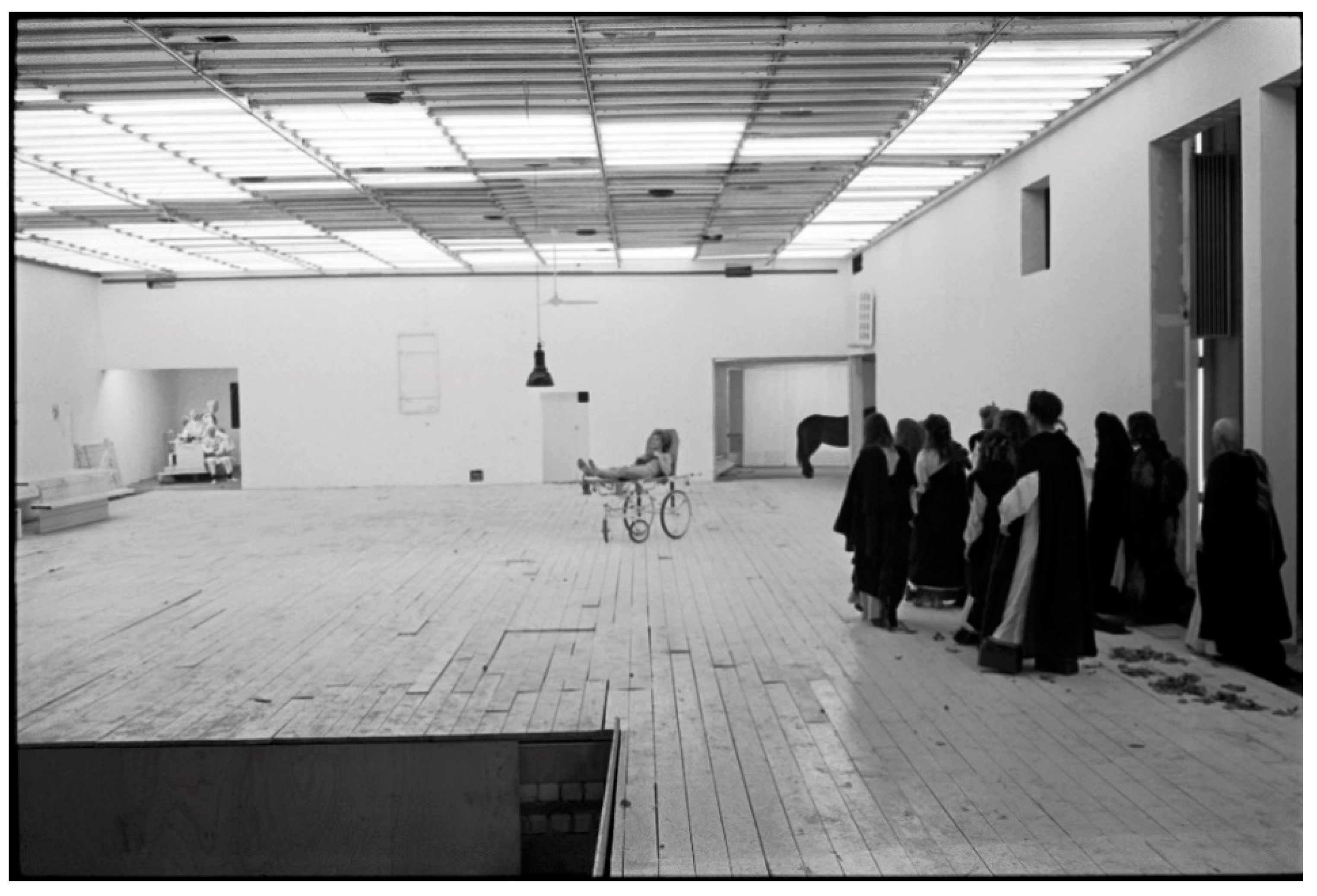

Grüber’s tactics were instantly introduced in the first scene. Stage designers Gilles Aillaud and Eduardo Arroyo, a sculptor and a painter, respectively, had turned the stage into a clinical space with white walls, floor and ceiling. There were slowly rotating fans, wall-mounted radiators, light switches, and a water faucet, as well as a toilet-roll holder complete with toilet paper. Pentheus’ Thebes was a clean and tidy place, where control was applied over everything, including temperature, light and water, even bodily functions. The back wall had four openings: on the left, a road-sweeping machine was parked, manned by Pentheus’ servants; in the middle there were two doors, a hatch in the wall around one and a half metres above ground and, next to it, an open door, in which a man in a tuxedo was standing with a glass of champagne in his hand; on the right, two horses were positioned behind a glass pane.

As music from Stravinsky’s

Apollon musagète filled the space, one of Pentheus’ servants pushed onto the stage a hospital gurney. On it lay Dionysus (Michael König), naked, except for an artificial phallus. His posture, combined with the way he was positioned on the stage to create a foreshortened perspective progressing from his feet to his head, was strongly reminiscent of Andrea Mantegna’s

Lamentation of Christ (c. 1480), displayed in the Pinacoteca di Brera in Milan (

Figure 1 and

Figure 2). The association of Dionysus with Jesus Christ is a recurring one, in the dying-and-rising god archetype, as well in religious imagery in early Christian art, such as “in wine and vine motifs alluding to the Eucharist” and most markedly “in the use of Dionysiac facial traits for representations of Christ” (

Mathews 1999, p. 45). It also appears as a binary in Nietzsche’s philosophy, with his

Ecce Homo culminating with the words: “Dionysus versus the Crucified!” (

Nietzsche [1908] 2007, p. 95;

Girard 1984, pp. 816–35).

As an additional layer of borrowed imagery,

Die Bakchen’s first scene also carried intriguing references to a triangle of religious personae—incorporating Dionysus, Jesus Christ and the sun-god Helios—in what could be described as a matrix of comparative mythology. For this, the reclining Dionysus was arranged in alignment with the horses in the background (

Figure 1), recreating the east pediment of the Parthenon (c. 438–432 BC) that depicts Helios’ horses alongside the god. In the pediment, the horses jump out of the marble at sunrise, bringing on the first light. Fittingly, when the gurney came to a halt, light from a lampshade lowered from the ceiling illuminated Dionysus.

What is more, the cohabitation of the stage by human and animal bodies—the actors and the horses—brings to mind artworks that were contemporary to Grüber’s production, such as Joseph Beuys’

Titus Andronicus/Iphigenie, a performance art piece presented in 1969 at the Theater am Turm in Frankfurt, for

Experimenta 3.

4 Wearing a fur coat, Beuys appeared on a darkened stage with a white horse. During the performance, Beuys made a striking juxtaposition between William Shakespeare’s

Titus Andronicus, with its excessive violence and cruelty, and Johann Wolfgang von Goethe’s

Iphigenie auf Tauris in which Iphigenia is presented as the personification of humanity. As isolated elements of the set, they also suggest Jannis Kounellis’ Arte Povera piece,

Twelve Live Horses (Untitled), presented also in 1969, at the Galleria L’ Attico in Rome, where the horses stood for several days.

5Dionysus’ initial speech began through stammering, emerging slowly from an almost incomprehensible language in which the god himself had to dive searching for words. While holding a red women’s shoe in his hands, Dionysus kept repeating the word

ich [I], as if finding his way into unfamiliar text. The repetition of the personal pronoun “ich”, an alliteration of “Ήκω”, the first word of Euripides’ drama, meaning “I am here”, is highly indicative of the characters’ speech difficulty, as well as the fragmentation of language, both present throughout the performance.

6 Dionysus’ monologue continued partly in German, partly in ancient Greek, frequently accompanied by imbecilic gestures and convulsive spasms, ending by repeating his first line “I am the god, Dionysus. Dionysus, son of Zeus” (v. 1).

After Dionysus’ final words, the right wall opened to the sound of bells, as well as leaves and cold wind blowing, allowing the chorus to enter. Walking slowly, almost in a dreamlike state, the Bacchae were also barefoot, but they were dressed in black cloaks over white blouses, skirts, or dresses. As one of the women—the chorus leader—sat down on the floor, slowly speaking the lines of the first chorus song, the others appropriated the stage: turned down the fluorescent lights, tore open the floorboards, started a fire and dug up water, leaves, grapes, and wool. They also dug out objects from the past—a bronze bust of the god Dionysus—and two men, the elderly Cadmus (Peter Fitz) and Teiresias (Otto Sander), figures that evoked plaster casts of Greek statues. This association was strengthened by Teiresias, who struck a ‘classical’ pose, lying down with one leg stretched out, the other bent at the knee, leaning against his forearm resting (

Fischer-Lichte 2014, p. 102;

2017, p. 282). His other forearm remained raised for quite a while, as in the

Seer sculpture, found on the east pediment of the Temple of Zeus at Olympia (c. 460 BC), now in its Archaeological Museum. The women assembled around the bust of Dionysus, at that point raised on the gurney and decorated as an altar, while Teiresias and Cadmus spoke long monologues.

Pentheus (Bruno Ganz) entered the stage. He too was naked, except for a plastic phallus, a part of a sleeve out of plaster on his left hand, and a belt. He started his speech with a long quotation from the diaries of Ludwig Wittgenstein, more precisely the entries for 31 May 1915 and 8 July 1916, that deliberate on the describing of the world through language

7 and being in the world as an individual.

8 During Teiresias’ long monologue that followed, Pentheus took the pose of Auguste Rodin’s

The Thinker (1881–1883), the multiple casts of which include a bronze one at the Alte Nationalgalerie in Berlin. This visual reference enforced Pentheus’ representation as a man of the mind, relying on thought and reason.

At a sign from Pentheus, the servants switched the fluorescent lights back on, replaced the floorboards, brushed the floor clean with the road-sweeping machine and reestablished order. Wearing yellow plastic suits, their faces covered by fencing masks of sorts, the servants were standing around like figures out of Bruegel’s

The Beekeepers (c. 1568),

9 a drawing found at the collections of the Staatliche Museen in Berlin. The beekeepers, guardians of an orderly and productive society, are seen here as having a sinister appearance, due to the very nature of their outfits that give us the bodily form of humanity without a face.

Before the first encounter between Dionysus and Pentheus, the latter demarcated a space on the wall and on the floor with adhesive tape, following a source of light, the same one that would be used later to create his shadow. Could this be a reference to Mel Bochner’s conceptual art practice that also marked space with adhesive tape to create binary spatial positions of inside/outside and either/or? Bochner had indeed exhibited his conceptual installation

Properties of between (1972) in

documenta 5, the legendary exhibition that solidified the position of conceptual art in the art world, titled “Questioning reality—Image worlds today” and directed by Harald Szeemann. What is also remarkable it that his work had also been read through Wittgenstein’s philosophy, in relation to abstract logical truths and the structure of reality (

Borden 1973, pp. 75–76;

Pincus-Witten 1972, pp. 75–76). To enforce this assumption, theatre and art critic Peter Iden suggested that Grüber “spells our inventions on stage which had defined the last documenta in Kassel” (

Iden 1974, quoted in

Fischer-Lichte 2014, p. 93), in the organizing committee of which Iden himself had served. Grüber’s probable attraction to conceptual art must have spurred from his own explorations of language as a slippery system of communication and of identity as an unstable structure.

In the following scene, Pentheus meets Dionysus in a sequence that establishes the two—according to Girard—as each other’s “monstrous doubles” (

Girard [1972] 1977, p. 160). As expected, Grüber did not shy away from the potential sexual overtones and irony of the scene that threatens to overrule “the normal order and coherence through the collapse of polarities” that are embodied by the very figure of Pentheus (

Segal 1977, p. 105). Standing against the light, Pentheus was seen contemplating the long shadow cast by his body. While he slowly squatted down, knelt and leant forward as if to drink water, his shadow diminished and then disappeared. Unnoticed by Pentheus, Dionysus approached very slowly, stepped behind him and cast a long shadow over his cousin. Being related and of similar age, the two figures, god and man, became nearly indistinguishable as they kissed intimately and stroke each either’s bodies, “melting into one another” (

Fischer-Lichte 1999, p. 15;

2017, p. 285). The setting was identical to the myth of Narcissus who leaned upon the water and fell deeply in love with his own reflection, providing imagery to poets and artists such as Ovid

10 and Caravaggio, as seen in

Narcissus at the Source (1597–1599), displayed at the Galleria Nazionale d’ Arte Antica in Rome.

What followed was the first messenger speech, one of two that structure the play and put the spectator onto the stage. For James Barrett, the play shows that an important part of

The Bacchae’s self-conscious interest is directed at the status of the messengers who are produced as “substantially ‘outside’ the drama—virtual ‘spectators-in-the-text’—and in so doing expands our notion of what is possible on the tragic stage while clarifying the status of the spectator with the play’s metatheatre” (

Barrett 1998, p. 338). A herdsman (Heinrich Giskes) entered wearing the elevated shoes worn in original presentations of Greek tragedy [

cothornoi], however, in this case, his feet were furry and prominently hooved. Fur sprouting from the skin of his right shoulder supported the assumption that he was a satyr. Satyr imagery was widely used in ancient Greek and Roman art, but is also featured in the Dresdner Zwinger, a palatial complex with gardens in Dresden, one of the most important buildings of the Baroque period in Germany.

The satyr-messenger was leading two dogs on leashes, a black and a white one. During his long description of the Bacchae’s activities on the mount Cithaeron that he had earlier witnessed, he fed the dogs raw meat. The hounds carried echoes of the ones that tore apart Pentheus’ cousin, Actaeon. They also stood as doubles of the maenads, also dressed in black and white, whom the messenger had reported shouting “Hounds that run with me, we are hunted now!|Follow me! Follow me!” (v. 731–732). Pentheus crouched beside the messenger and snapped at a piece of flesh the herdsman was holding. He himself ate a piece of the raw meat, sharing it between himself and the dogs. This was a case of omophagia, the communal feast on raw meat that followed a sacrifice, thus setting the stage for Pentheus’ demise.

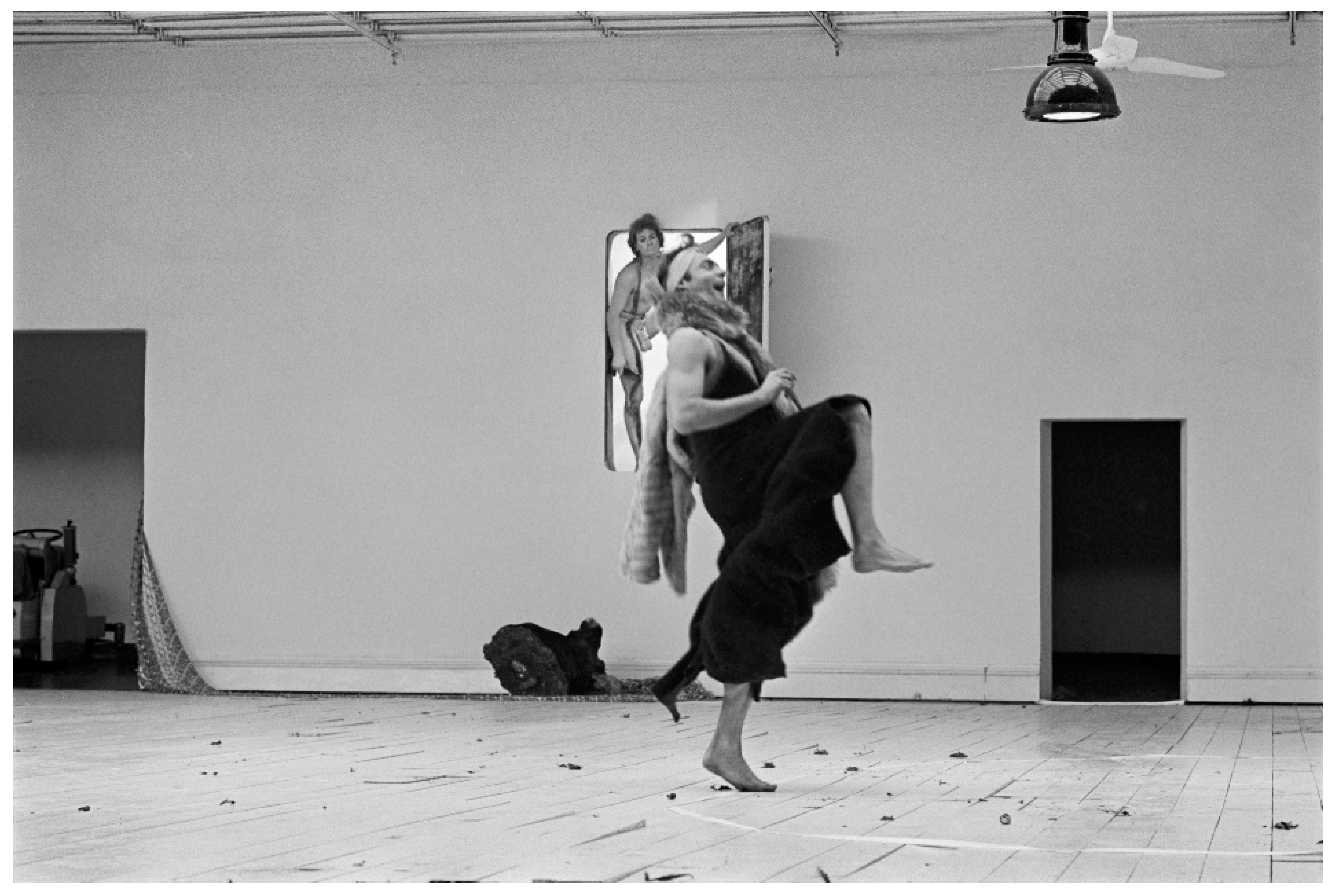

In the second encounter between Dionysus and Pentheus, the god convinced the king to travel to Cithaeron dressed as a maenad, to witness the Bacchae led by his mother Agave and her sisters. Pentheus appeared dressed in contemporary women’s clothing: a dress, a fur jacket, a scarf around his hair and eventually wore the red shoe that Dionysus had been carrying with him. Dionysus applied lipstick on him, and he admired himself in a hand mirror, the same one used later by the god himself. This is also the moment that the idea of doubling becomes clearest in Euripides’ text, as Pentheus, coming out of the palace under the influence of Dionysus, claims to see two suns and two cities of Thebes. For Charles Segal, this offers an important insight into the nature of the divine figure of Dionysus: “Doubling and reversal work together to reinforce the ambiguity of identity in the realm of Dionysus” (

Segal 1982, p. 30;

Goldhill 1988, p. 142). Pentheus then took some exaggerated dancing poses (

Figure 3), just like the ones depicted in the Pronomos Krater, arguably the most celebrated artwork that is associated with the ancient Greek theatre, as it depicts a Dionysian thiasos. Made in Athens (c. 400 BC), and discovered in Southern Italy, the red-figure krater now resides in the Museo Nazionale Archeologico in Naples. There was a picture of the Pronomos Krater in the

Die Bakchen programme notes (

Fischer-Lichte 2017, pp. 285–86).

As Pentheus was led by Dionysus on horseback to Cithaeron, the fourth chorus was chanted by the women, alongside a male voice, over loudspeakers. Language progressively collapsed as German and ancient Greek merged, words were echoed and repeated out of context, producing an asyntactic soundscape, that led impeccably to the second messenger speech. The second messenger (Rüdiger Hacker), reporting the sparagmos [dismemberment] of Pentheus, appeared covered in slime and mud. He stood motionless for over thirty minutes, framed by the right door, his voice swelling and pausing, changing pace without rhythm, stretching sounds and using extreme variations in pitch and volume. The slime continuously dripping from his body made an explicit reference to Stein’s Exercises for Actors from the previous evening, especially the hunting, sacrifice, and initiation segments. It also made an implicit reference to the Viennese Actionist, Hermann Nitsch, and his Orgies Mysterien Theater, the actions of which had started as early as 1962 and had been recently exhibited in documenta 5. Nitsch combined real animal carcasses and blood that was poured over crucified human bodies in order to produce images and actions that went past disgust, leading his audiences to catharsis.

As the messenger delivered his long and painstaking speech, the Bacchae were spread out on the stage, sitting or standing, positioned to create the impression of a picture painted according to the central perspective principle adopted in the Renaissance. They formed two diagonal lines that ran from the front of the stage to the middle opening where the messenger stood, fixing him as the centre of attention (

Fischer-Lichte 2014, p. 107;

2017, pp. 287–88). Indeed, writing in an edited volume focusing on the work of Klaus Michael Grüber, Bruno Ganz, the actor that played Pentheus in this very production, compared the director to a painter (

Banu and Blezinger 1993, quoted in

Haviaras 2015, p. 268). When the speech was over and the messenger had departed, the Bacchae followed him assuming the same poses that Pentheus had employed earlier, the ones from the Pronomos Krater.

Wrapped in bloody bandages, Agave (Edith Clever), mother of Pentheus, entered the stage, holding a thyrsus topped with her son’s head, that her senses were telling her was the head of a young lion. Her costume was unlike the ones of the rest of the thiasos (

Figure 4), borrowed by another Viennese Actionist, Rudolf Schwarzkogler. Schwarzkogler’s actions, which began in 1965 and came to an end with the artist’s death in 1969, display oppositions such as bandaging and mutilation that are meant to confuse the relationship between healing and pain (

Figure 5). His work was shown posthumously in

documenta 5. Before the horrible moment of re-cognition of Agave’s deed, the servants replaced Pentheus severed head with a silver tray, where a shirt, shoes, and pieces of a suit were arranged, the contemporary clothes worn earlier by the man in the tuxedo.

The final scene found Cadmus and Agave trying to piece together the fragmented clothes on the tray. Grüber decided to end the play here as the original text of Euripides breaks off at this exact point, in what Euben calls “an almost too perfect irony” (

Euben 1990, p. 133), and has been supplemented by the findings of philologists. Alternating between German and ancient Greek, Agave spoke the final words of the performance: “Father, you see how everything has changed for me…” (v. 1329).

Agave’s last words, and the ones that wrap up Grüber’s production, were not only meant for dramatic purposes. Indeed, the change of fortune claimed by the daughter of Cadmus also applied to the spectators in terms of their status as subjects within a specific cultural identity. For Fischer-Lichte, the very idea of the cultural identity of the German educated middle class [

Bildungsbürger]—to which the majority of the spectators belonged—as based on an identification with Greek culture, was not simply undermined by

Die Bakchen, but shattered in its very assumptions (

Fischer-Lichte 2014, p. 112). As she claims, “What was believed to be unshakeable knowledge of ancient Greek culture was exposed as nothing but images composed of elements from modern times based on our own imagination of ancient Greece and on desires generated by our contemporary world” (

Fischer-Lichte 2014, p. 114). As youths following their initiation, the German spectators had to leave the

Antiquity Project with this new knowledge distilled to them through the two performances: that language does not equal communication and seeing does not amount to knowing.

4. Grüber’s Theatre of Images

Certainly, what Grüber delivered was a completely new concept of theatre, distant from a hermeneutic approach with reference to the dramatic text, but closer to a radical theatre of images (

Fischer-Lichte 2014, pp. 104, 106, 109). It is indicative that Heiner Müller, reviewing the performance in 1975, underlined that this was the event he had been waiting for, the moment that theatre assimilated the accomplishments of the visual arts in the twentieth century, which had remained unabsorbed for so long. Yet, Müller’s reference was exclusively to Surrealism, which he thought was present in the performance (

Müller 1986, p. 47). For Sotirios Haviaras, on the other hand, the two visual arts avant-gardes that ran through

Die Bakchen, were Arte Povera and Figuration Narrative—to which the production designers, Gilles Aillaud and Eduardo Arroyo, subscribed—, two artistic movements that were able to render the two worlds of the tragedy: the Bacchic on the one hand, and Pentheus’ Thebes on the other (

Haviaras 2015, p. 269). However, as I have attempted to demonstrate, there was a wider repertoire, alongside a certain specificity, to the visual elements of

Die Bakchen, featuring references to works of classical and Renaissance art, modern sculpture, Arte Povera, as well as conceptual and performance art pieces.

Still, it is important to underline that Grüber was not shooting for a museum aesthetic. Although his production of

The Bacchae presented Greek tragedy alongside antiquities and works of art, all coexisting fragments of several eras of human culture, his approach was not that of a museum keeper. According to Hans-Thies Lehmann, Grüber’s production was the antidote to a dying genre of tragedy, one that threatened to deteriorate “into the mere pretense of transgression: a matter of museums and

Kulturgut” (

Lehmann 2016, p. 401). As Lehmann underlines, without such interruption of the aesthetic itself, tragedy would remain what it is least supposed to be: a museum-piece of educated culture [

Museum und Bildungsgut] (

Lehmann 2016, p. 444).

In fact, Grüber’s

Die Bakchen was not an archive, that is a site of knowledge production, but a disturbance to the archive.

11 “Dionysus”, reads a note in the rehearsal transcripts, “is shown not as a character but as a condition that must necessarily be transformed into something else. He is an irritant who provokes a space of negotiation but has no space himself. He represents a violation of the scene. […] a disturbance in a cybernetic system” (

Remshardt 1999, p. 40). This remarkably contemporary terminology makes a strong claim for Grüber’s awareness of new developments in the visual arts, where systems aesthetics and cybernetics marked the passage to art as a set of relations, through a recoding of information, knowledge, and technology. As it appears, when Grüber, Aillaud, and Arroyo visited

documenta 5 in 1972, they took on more than visual influences from individual artworks, or presentation methods, like the white cube they employed for their stage (

Figure 6), but acquired—as Maria Daraki has claimed for all that comes to contact with Dionysus—“a different way of thinking” (

Daraki 1985, p. 232). Their scenography in the expanded field

12 called for threads, webs and intra-actions

13 between textual excerpts and spoken words, bodies—human and non-human—actions, objects, images, situations, and environments.

14 As Grüber has asserted in one of his rare interviews: “The point of departure is not theatrical form, but rather material: people, room, floor, lights, parts of the body, voice.—Dialectic: I take the room, the room takes me” (

Klett 1975, p. 84, quoted in

Locke 1977, p. 54). Indeed, as part of a wider network of disjointed words and isolated images, Grüber did not hesitate to exhibit his own identity as fragmented, his position doubled: a director mirroring neither a painter, nor a museum keeper, he aligned himself, through

Die Bakchen, to the newly established role of the contemporary curator.