Abstract

With the expedition of the Portuguese explorer Jorge Álvares in 1513, Portugal took the first step toward discovering the new world. Since then, the Portuguese have become messengers between Asia and Europe. They successfully created a unique image of China in Portuguese territory by accepting and spreading Chinese culture. However, people see what they can and what they want to see, which depends greatly on their cultural and philosophical perspectives. Therefore, when the Portuguese adopted and used Chinese traditional representations to create art through the prism of their own cultural and philosophical values, their subjective perspectives became involved, which could be reflected in their artistic creations. By decoding the shanshui motif on Chinese porcelain and Portuguese faience, this study aims to discuss the differences between Chinese and Portuguese views and explore what is beyond representations, which is related to aesthetic and cultural perspectives. This indicates that imitation without understanding and modification without intention give rise to a new aesthetic value, a distinct cultural phenomenon, and a mixed heritage where two worlds subtly intersect.

1. Introduction

Portugal is the Eurasian maritime pioneer par excellence, the messenger of Asia in Europe and of Europe in Asia. Since the expedition of the Portuguese explorer Jorge Álvares in 1513, Portugal took its first steps to discover the new world, which was of great significance and financial benefit. Portuguese travelers brought back “China” and began to establish their imagery about this mysterious country. Various first-hand information and precious reports from travelers provided convincing evidence about China, vividly described in their literature works such as Suma Oriental by Tomás Pires, Algumas Cousas Sabidas da China by Galiote Pereira, Ásia-Decade by João de Barros, Tratados das Cousas da China by Frei Gaspar da Cruz and Peregrinação by Fernando Mendes Pinto.

The information this literature failed to include and express could be delivered through cultural and visual materials, which also tangibly exhibit the intercultural dialogue between China and Portugal, as Jorge Flores summarized “in the objects read the Portuguese East, as much or more than in the documents” (Flores 1998, p. 51).

Porcelain has a particular value among all products with high profits. Even though it might have been submerged in the ocean for centuries and finally came to us in fragments, it presents the intersection between two cultures and the encounter between two civilizations. Each piece shows the history of an expanding world in its own way.

According to Queiroz, “in ceramics the character of the people who produce it is reflected: the poetry of each nationality is in its forms, the different aspects of each nation and each country are in their colors, at the same time, the joy or sadness of their creators is observed” (Queiroz 1907, p. 4). Throughout history, human characteristics, historical traits, and even social changes have been recorded in each piece of ceramic.

The production of Portuguese faience may have begun in the middle of the sixteenth century, as the documentation is replete with references to numerous malegueiros and the production of málega, especially in a 1551 document (Sebastian 2010, p. 112; Casimiro 2010, p. 531; Pais 2012, p. 145). The word málega has been used as a synonym for pottery and Earthenware in Portugal since the 15th century, and potters are known as malegeiros (Meco 2018, p. 13). The earliest Portuguese faience productions were imitations of Spanish ceramics, specifically Sevillian majolica (Casimiro 2010, p. 531). Then, white, opaque, tin-rich enamel-coated pieces from Italy arrived in Portugal. During the second half of the sixteenth century, a more refined decorated faience was introduced to Portugal, and Antwerp-based Flemish potters established themselves there. From the Near East, Islamic aesthetics, in accordance with the Portuguese taste, also arrived in Portugal through a direct connection or interpretations made by the Spanish or Italian potters, giving rise to the “Geometric Decoration”, which was applied extensively to Portuguese faience during the first quarter of the 17th century (Roque 2018). However, Chinese porcelain, specifically kraak porcelain, played an important role in the production of Portuguese faience, particularly in terms of decoration. Chinese, European, and Islamic influences coexist in the production of Portuguese faience. It is impossible to pinpoint when Portuguese faience began to prominently feature Chinese motifs. However, based on the findings of Portuguese archaeologists, it likely occurred during the last two decades of the 16th century (Casimiro et al. 2015, p. 68).

As Robert Smith states in his book, the Portuguese were the first Europeans both to import and copy in faience the porcelains of the East. What they imitated was the blue-and-white Ming dynasty export ware, especially that of reigns of the emperors Jiajing (1522–1566) and Wanli (1573–1619) (Smith 1968, p. 26). The Portuguese were attracted by Chinese porcelain when it arrived and there was a great demand for it. From the first half of the seventeenth century, Lisbon’s craftsmen began to produce their “porcelain” with the materials they could find. We know that the so-called “Lisbon’s porcelain” (Sandão 1976, p. 30) is not real Chinese porcelain due to the raw material and the cooking temperature.

As claimed by Rafael Salinas Calado, the privileged commercial relations that the Portuguese were able to develop with China from the first quarter of the 16th century furnished them with perfect knowledge of Chinese porcelain and constituted a basis for influencing the decorative elements of Portuguese faience. And this tendency for trading and making Chinese-style ceramics subsequently took hold in all of Europe, but especially in Holland (Calado 2002, pp. 16–17).

Portuguese faience has been deeply influenced by Chinese porcelain since the Portuguese were crazy about it. The themes of the faience were inspired by Chinese porcelain. However, unlike the Dutch, who tried to imitate Chinese prototypes strictly, the Portuguese reinterpreted them quite liberally. What it looked for was more than the artless imitation of Chinese porcelain. Uniquely, it employed a combination of oriental and occidental decorative motifs, creating a novel aesthetic dimension and establishing a particular artistic expression in ceramics.

In recent years, researchers have endeavored to find the exotic elements or motifs in Portuguese faience and decode their symbolic meanings. However, most existing studies about Portuguese faience or Chinese porcelain extol the “exoticism” with which such heritage has always been observed. This could downplay its true artistic and symbolic potential and ignore modifications during the imitation process. It is obvious that Portuguese craftsmen followed a consistent pattern of borrowing motifs from Chinese porcelain, but they maintained the original traits of Portuguese faience and created their own personality, which is distinguished by Monteiro as “to honor without subservience” (Monteiro 1994, p. 24).

The fundamental objective of this study is to discuss cultural understanding, by offering a comparative analysis of the shanshui motif depicted on Chinese porcelain and Portuguese faience. Sometimes what people see depends on what they can and want to see in their cultural and philosophical perspectives. There is no fixed relationship between the artwork and its representation, since how images generate their meanings depends mainly on the viewers.

What has been mentioned above raises the following research issues: Are there differences between Portuguese and Chinese views? If so, how can the particularities of the Portuguese view about China be proven? Can these differences be explained or demonstrated?

These issues and ideas will be clarified mainly through a series of comparative analysis studies on Chinese porcelain and Portuguese faience, especially by analyzing the differences in shanshui motif’s representation.

2. Shanshui

Among the various Chinese porcelain motifs applied to Portuguese faience, the shanshui motif is enrolled in this study for several reasons. The main one is that even though shanshui was not popular or admired in the history of Chinese porcelain, the imagery of China was constructed in Western thought through the shanshui theme, almost becoming the primary illustration of China in Europe.

Various Chinese porcelain motifs were applied to Portuguese faience, among which shanshui served to construct the imagery of China in the Western world and became the primary illustration of China. Therefore, the shanshui motif was chosen for the study even though it does not enjoy great popularity and admiration in the history of Chinese porcelain.

The Shanshui motif in ceramics derives from Chinese paintings. Shan(mountain) and shui (water), which combine to denote landscape (shanshui) in Chinese, represent two poles of cosmic energy, the yang, and the yin, respectively. They are fundamental compositional elements of traditional Chinese landscape painting, also known as shanshui painting, an independent art form that rose in China around the 4th century. The first recorded reference to shanshui painting was written in Hua Shanshui Xu (Preface on Landscape Painting) by Zong Bing (375–443), dating back to the 15th century, whose appearance is closely related to Chinese philosophy, especially Taoism.

The term “shanshui” may come from the story of Zong Bing, who traveled a long time through mountains and rivers in search of inspiration from nature. Years later, he had to stop his trip due to health issues. One day, while mourning the physical situation that restricted him from experiencing nature, he realized that his spiritual world should never be constrained despite his physical limitation. He took up his brush and started sketching the mountains and rivers that he had enjoyed. Then, he laid down on his mat and gazed at his painting, imagining himself traveling among these images of mountains and rivers. This famous story of Zong Bing Wo You 宗炳卧游 (meaning spiritual journey in bed) plays an essential role in the emergence of shanshui in the history of Chinese painting. Zong Bing Wo You is not only a significant issue in the history of Chinese painting but also demonstrates an inner calling to take shanshui painting as a conceptual and spiritual experience rather than merely visual. The shanshui theme is more about “being” than “seeing” (Law 2011). Since then, many scholars have been discussing the shanshui painting theory on the basis of Zong Bing’s perspective technique of shanshui painting and his aesthetic theory—Chang Shen 畅神 (free flow of one’s mind).

Even though styles have varied throughout history, paintings of the ancient Chinese masters still share some common characteristics, which can also be reflected in shanshui porcelain pieces.

As a significant stylistic innovation, the shanshui motif only became a subject of porcelain decoration in the seventeenth century, and it is always associated with the scholarly taste of the literati class (Ströber 2011, p. 19). Despite the fact that the shanshui motif on Chinese porcelain varied from period to period, we would like to use this Qing Dynasty porcelain (Figure 1) as a representative example to illustrate some typical characteristics of the shanshui motif. Curtis’s research indicates that this dish was likely a collectible for a member of the educated elite (Curtis 1995, p. 72). This dish’s motifs are diverse and abundant, rendered with care and precision, but they do not induce a sense of disorder or confusion. The image contains mountains, houses, a flock of birds, a boat with a fisherman on the water, and a man crossing a bridge on the upper left-hand side, possibly on his way to pavilions on the shore. The style and construction of this dish are highly expressive. According to Eva Ströber’s article, this dish’s landscape is painted in the distinctive style known as “Master of Rocks” (Ströber 2011, p. 21).

Figure 1.

Chinese porcelain, Kangxi period (1662–1722), 1665–1675. Princessehof Ceramics Museum, Leeuwarden. Inv. OKS 1987-15. Retrieved from Ströber (2011).

Porcelain and rice paper are different materials; however, porcelain also displays the traits and techniques of Chinese shanshui painting. In dish OKS 1875-15 (Figure 1), the modeling of the rock surfaces is depicted with parallel texture lines and graded color intensity, with heavy cobalt blue outlines, presenting a three-dimensional effect, emphasizing distance and proximity, and even employing the traditional Chinese shanshui painting technique Cun Fa (texture method). Through the technique of Liu Bai, the water is portrayed by a white porcelain base with a few irregular light blue specks, emphasizing the vastness of the vacuum. The vacant spaces, such as water, act as perceptual breaks, permitting viewers to freely roam or travel through the vast expanse produced by porcelain artisans. The treatment of space is segmented, and this dish employs three fundamental schemata. The image from front to back is divided into three stages: the front with giant trees and mountains, the middle with fishermen on the water, and the background with a person on a bridge and mountains that overlap. The image may be appreciated from various vantage points, component by component and motif by motif. This type of perspective in shanshui painting is considered an atmospheric perspective (Sullivan 2007, p. 415), not a fixed-point perspective (Law 2011, p. 374), but a specific concept in Chinese art theory—yuan (distance)—which requires shifting perspectives and creates an interactive process between the artist and the viewer (He 2014, p. 18). The two human characters pictured on this dish are contemplating or enjoying the harmony of nature’s elements but are never attempting to control them. They are symbolic images expressing their dream retirement lifestyle near nature. In addition to indicating the magnitude of the landscape, the tiny people provide spiritual majesty to the entire scene.

The Shanshui motif has always been infused with human emotion, particularly literati’s emotions. The apparent tranquility of the literati shanshui motif conceals a profound social connotation. According to the Princessehof Ceramics Museum (Keramiekmuseum Princessehof), this dish was manufactured during the reign of Kangxi (1662–1722). The closest date would be between 1665 and 1675, which corresponds to the beginning of Kangxi’s reign or the period of transition (1620–1683). The Han-dominated Ming dynasty was overthrown by the Man-dominated Qing dynasty using military force. The 1644 Battle of Beijing left the Chinese with a traumatic memory. When the Manchu defeated the Ming dynasty, the literati resisted the Manchu way of thinking vehemently. Pieces of porcelain from the reigns of Shunzhi and early Kangxi communicate this cultural and social signal. The imagery depicted on shanshui porcelain has become a refuge from reality, revealing the mentality of the Chinese in a turbulent society. Once culture and art conform to the social form, they come to life with vigor.

In Chinese culture, however, shanshui is not only a traditional motif or an artistic practice that provides aesthetic pleasure, but also an experience of self-cultivation; it not only reveals the natural splendor to humanity, but also reveals the natural law of changes, and reflects the ideology of the society and the mental state of the people. The following section discusses a set of shanshui motifs and their counterparts on porcelain and faience, visually displaying the interpretation of the Chinese shanshui motif in a Portuguese context and exploring what it is beyond the representation.

3. Shanshui on Two Pieces: Portuguese Faience and Chinese Porcelain

To figure out the differences between Portuguese and Chinese views, two representative pieces with the shanshui motif are shown in this study, a Portuguese faience dish from the second half of the 17th century (Figure 2) and a Chinese porcelain dish made during the Jiajing period (Figure 3). Both are analyzed concerning their decorative details and artistic compositions.

Figure 2.

Portuguese Faience, 1650–1700. National Museum of Ancient Art, Lisbon. Inv. MNAA 2402.

Figure 3.

Chinese Porcelain, 1550–1566. Soares dos Reis National Museum, Porto. Inv. MNSR 1829.

The Portuguese faience dish, inv. MNAA 2402 (Figure 2), which was made during the second half of the 17th century, is currently being displayed on the exhibition stand named “Small Motif” (“Desenho Miúdo”) in the National Museum of Ancient Art in Lisbon (Museu Nacional de Arte Antiga). José Queirós in his fundamental book on Portuguese Ceramics mentioned the creation of this new designation in the Portuguese ceramic classification—”Small Motif”, which constitutes a phase of transition from purely oriental motifs to a hybrid decorative grammar, in which western elements appear to punctuate the pieces (Queiroz 1907). This so-called “Small Motif” in the chronology established by Reynaldo dos Santos was considered common among the oldest motifs inspired by Chinese porcelain (Santos 1970). Researchers from Portugal discovered that the “Small Motif”, in the second half of the 17th century, roughly between 1660 and 1680, appeared in Lisbon in limited quantities and was produced almost exclusively for domestic consumption (Sebastian 2010, p. 505; Roque 2018, p. 35). The “Small Motif” pieces dated between 1660 and 1668, according to Alexandre Pais and João Monteiro, could be a decorative style exclusive to one pottery in Lisbon (Pais and Monteiro 2013, p. 73). In the second half of the 17th century, the introduction of the manganese-purple pigment in Portuguese ceramic ornamentation coincides with the emergence of this decorative style (Roque 2018, p. 171). The human figure, water, pavilion, pagoda on this piece of “Small Motif”, which are typical elements of shanshui motif, mirror the influence of Chinese motifs on Portuguese faience.

In this named “Small Motif” Portuguese faience dish (Figure 2), the clearly Chinese-influenced decorative composition is focused on its central set, in which stands out a hermit monk dressed in a long tunic, under the shade of his large parasol, crossing a bridge to reach a turreted building with a flying flag, possibly suggesting a mosque. On the right side, a boat with a large and unfurled Western vessel sails over the water. This water (shui) is depicted by some casual parallel lines and by daubing a heavy cobalt blue. Curiously, the dividing line between the left and right of the central set, that is, the axis of the composition, is outlined by black lines and filled with parallel blue dashes. Due to its strange shape and this slipshod manner of painting, it is quite difficult to identify this axis of the composition.

A very similar decorative central composition on another Portuguese faience dish, inv. MNAA 6781 (Figure 4), albeit with two human figures, is referred to by João Pedro Monteiro in his book entitled A Influência Oriental na Cerâmica Portuguesa do Século XVII, as also belonging to the National Museum of Ancient Art. According to João Pedro Monteiro, the central medallion of inv. MNAA 6781 is decorated with oriental figures surrounded by an exotic landscape, in a composition divided in half by an elongated rock from which a tree emerges (Monteiro 1994, p. 134). On both sides are human figures, the one on the left crossing a bridge and the other on the right standing in a small boat, surrounded by buildings, branches, bushes, and with an aquatic base where a swan spreads its wings.

Figure 4.

Portuguese Faience, 1650–1700. National Museum of Ancient Art, Lisbon. Inv. MNAA 6781.

Besides the identical central medallion, especially the artistic composition divided by an erect rock, the two pieces of Portuguese faience also have very similar borders in a continuous composition, which are separated from the central part by a white narrow band. Internally, the border is defined by a thin line of manganese and a thick brushstroke that marks the Earth, while externally, it is limited by two thin lines of manganese, reinforced by strokes of blue wash. The space of the border is also densely filled with a continuous and stylized composition of Chinese decorative elements with flowering trunks, fruits, bushes, corks, rocks, clouds, and towers, among others, constituting a disorderly and unsystematic image of fullness.

According to Mário Roque, this type of elaborate and detailed decorative composition, “Desenho Miúdo”, evolves in Lisbon around 1660 and is characterized by the spreading of the dense decorative elements over the entire surface of the object, in an Eastern-influenced manner, typical of Ming to Qing transitional porcelain objects (Roque 2018, p. 171). However, due to the highly stylized nature of the decorative motifs, it is difficult to identify them depicted on the borders. The decorative elements representing horror vacai were likely derived from easily recognizable Chinese porcelain models, but they were interpreted freely and creatively by Portuguese craftsmen rather than purely copied. On the border of dish inv. MNAA 6781 (Figure 4), we observed three pomegranate motifs, which remained Chinese models but were surrounded by stylized abundant leaves.

Excluding private collections and foreign museums, we have only found two faience pieces with the same compositional axis applied to their central medallions in Portuguese museums. Moreover, the details depicted on these two faience pieces are distinct (Figure 2 and Figure 4). Dish inv. MNAA 2402 (Figure 2) is surrounded by a band of triple “beads” (“Contas”) between two friezes, whereas dish inv. MNAA 6781 (Figure 4) is surrounded by a blank band. Moreover, the painted human figures on these two pieces are quite distinct. Alexandre Pais described the oriental figure on dish inv. MNAA 2402 (Figure 2) as elongated and with a very particular head shape (Pais 2012, p. 364). Similar human figures with strange head shapes and with parasols can be seen on other faience pieces—dish inv. MNAA 2401, bottle inv. C 640 (illustrated in book “Lisboa na origem da chinoiserie: a faiança portuguesa do século XVII, colecção Mário Roque”, cat. p. 179, nº. 56) and dish inv. ACP C123 (illustrated in book “Faiança Portuguesa do Ateneu Comercial do Porto”, cat. p. 29, nº. 17). On dish inv. MNAA 6781 (Figure 4), there are two human figures of different sizes wearing similar costumes and headgears. Similar human figures also can be traced on other faience pieces—dish inv. MNMC 9851, salver inv. C 621 (illustrated in book “Lisboa na origem da chinoiserie: a faiança portuguesa do século XVII, colecção Mário Roque”, cat. p. 171, nº. 53), dish inv. AM 45 (illustrated in book “Faiança Portuguesa:séc. XVI a séc XVII”, cat. p. 45, nº. 65) and jar inv. CER 87 (illustrated in book “Faiança Portuguesa da Fundação Carmona e Costa” p.66). Miguel Cabral de Moncada made a deduction about the figure depicted on dish inv. AM 45, and he considered this figure based on the Chronicle of the Three Kings (Moncada 2008, p. 64). As for the jar inv. CER 87, Alexandre Pais and João Monteiro explained images of Four Emperors or Four Quadrants representing the cardinal point of the compass, who may wear hats like those seen here (Pais and Monteiro 2003, p. 68).

Now we turn our attention to this Chinese porcelain dish, inv. MNSR 1829 (Figure 3), exhibited currently in Soares dos Reis National Museum in Porto (Museu Nacional de Soares dos Reis). This piece was made in Jingdezhen, during the reign of the Jiajing Emperor (1522–1566) in the Dynasty Ming. The central set of this dish is decorated with a medallion inside a double concentric circle, where various planes an aquatic landscape with several rocky islands, steep hills, pagodas, and vegetation can be observed. The foreground shows several central rocks, where a pagoda with a flying flag is partially hidden behind, constituting the axis of the composition of the central set. On the left side, two human figures on a bridge are heading to a double-roofed pavilion with a huge hanging branch, and on the right side, one fisherman is rowing his sampan up the water, drawn by parallel blue dashes. If we look at the details, what attracts our attention are the two human figures, one figure rides his white horse while another follows him, holding some object with him. The background is formed by three islands of different dimensions, the central one is much larger and has a pagoda with a flying flag partially hidden behind, which is very identical to the island in the foreground and seems to mirror it. Two islands with floating clouds and hanging branches are depicted on both sides. Furthermore, a little sun adds spice to the central image of this Chinese porcelain dish. They evoke, although schematically, aspects of nature and of life. On this porcelain dish, inv. MNSR. 1829 (Figure 3), its central medallion gives us a concept of space by the contrast between the vigorous and powerful foreground and the floating and idyllic background.

The design of this dish of Chinese porcelain (Figure 3) in particular and its style is highly expressive, marked by mountains and remarkable rocks. It is characterized by the unique technique of using numerous parallel structural lines with graded color intensity to depict the surface and volume of the dramatically towering mountains. Chinese porcelain, even with the simplest motifs, always contains a moral lesson related to the ethical value that drifts from the agitated society. The pine tree and the standing crane on the left of the central image recall the Chinese literati (wen ren) who survive the vicissitudes of life due to the combination of strength of mind and resilience. A traditional Chinese pavilion is hidden behind the rocks and trees. Due to the characteristic of the two figures and the oblong object, which reminds me of a musical instrument, they are given a particular cultural connotation linked to the classical allusion coming from Xie Qin Fang You 携琴访友 (Taking a qin to visit a friend). The entire image expresses a harmonious and peaceful life of literati who have been removed and isolated from the imperial court and even from the world. These details precisely describe the state of society.

The image offers viewers a feeling of freedom and tranquility for the imagination. In comparison with the impressive landscape, human figures are painted in small proportion and convey the insignificance of the human being with nature, and accurately reflect Tian Ren He Yi 天人合一 (meaning the unification of the cosmos and humanity), one of the essential ideas of Chinese philosophy presented by Confucianism, Taoism, and Buddhism.

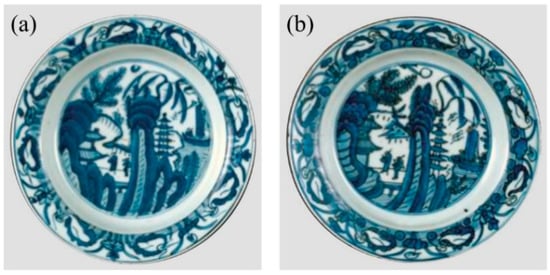

If there is a focus on the axis of the composition depicted on the faience dish, inv. MNAA 2402 (Figure 1) and its artistic composition, we can find a very identical axis presented on the other two porcelain dishes, inv. CMAG 21 and inv. CMAG 22 (Figure 5a,b), both made in the second half of the 16th century from Jingdezhen. The central medallion of two dishes, with a similar decorative shanshui motif, including a double-roofed pavilion, two human figures, rocks, weeping willow, pagoda, sampan, and water, constitutes an identical composition. The highest large vertical rock, topped by weeping, outlined by thick black lines, and filled with parallel blue short lines at random, stands out as the axis of the central set. Compared with the porcelain, inv. MNSR 1829 (Figure 3), on these two dishes (Figure 5a,b), although the central decorations are very identical, they are less harmonious and the blue is much more intense, gradually losing the artistic conception of shanshui.

Figure 5.

Chinese Porcelains, second half of the 16th century. Casa-Museu Dr. Anastácio Gonçalves, Lisbon. (a) Inv. CMAG 21; (b) Inv. CMAG 22.

On the border, whether in dish inv. MNSR 1829 (Figure 3) or in dishes inv. CMAG 21 and 22 (Figure 5a,b), they are depicted as elegant herons hidden among lotus flowers, constituting continuous motifs, and creating densely an image with full and hazy senses. In Chinese culture, as a poetic symbol, the heron represents purity, elegance, and perfection and has always been praised in ancient poems. In Chinese porcelain, as one of the most popular motifs, the herons are nearly always drawn with a completely white body, while the plant motifs around them are filled with color. The Chinese character of heron 鹭 (pinyin: lù) is homonymous with the character 路 (pinyin: lù), which means “street, path, or way”. The Chinese character of lotus 莲 (pinyin: lián) is homonymous to the character 连 (pinyin: lián), which means “successive”. Therefore, the meaning of successive progress is added to Chinese porcelain with the heron and lotus motif, constituting the Chinese idiom, “一路连科” (pinyin: yí lù lián kē), which means “come out first successively from local to provincial to court exams” and expresses a good expectation both in the Imperial Examination (Keju) and in continuous career achievement.

The motifs themselves contain no cultural or symbolic context. They become meaningful because of created meanings, imagined figures, and connections established by human intelligence. This type of artistic composition with heron and lotus motifs (borders on dishes inv. MNSR 1829, inv. CMAG 21, and inv. CMAG 22) also became very representative of Chinese porcelain during the Qianlong reign of Dynasty Qing. During a peaceful and prosperous period, in addition to expressing expectations to enter the official career, the Chinese emperor also tried to convey a warning to officers during their career in the imperial court, thus enriching the symbolic phrase “一路清廉” (pinyin: yí lù qīng lián), through the subtle expression of the same porcelain motifs—heron and lotus, which means “always be honest and fair in your governmental role”.

There are additional pieces of Chinese porcelain in Portugal with similar artistic compositions on the central medallion and with herons and lotus motifs on the border, including dishes inv. 150 (Figure 6) and inv. 124 (Figure 7) (mentioned by Goldschmidt 1984, pp. 34–35) of the Porcelain Room of Santos Palace, the current French Embassy in Portugal, and dish inv. CMAG 12 (Figure 8) of Casa-Museu Dr. Anastácio Gonçalves. In addition, similar porcelain dishes from the Jiajing period can be found abroad, particularly in the Topkapi Saray Museum in Istanbul (mentioned by Regina Krahl 1986, pp. 684–87). According to B.S. McElney’s chronology of Kraak porcelain and Xiong Huan’s study, the first period (1550–1570) and the second period (1560–1580) represent the initial stage of typical Kraak porcelain, whereas beginning with the third period (1575–1590), panels were added to the rims. The series of porcelain dishes mentioned in this study are from the second period—continuous rim decoration and white cavetto, broad line painted inside the rim (McElney 1979; Xiong 2006). According to the design description and chronological study of Clarence Shangraw, the sequence of porcelain dishes belongs to Kraak Type II (1560–1570)—white cavetto, continuous rim decoration with “water”—which was depicted by fine lines along the inner rim strips. And because no cargo from this period has been recovered, this dating is speculative (Shangraw and Porten 1997). According to the cited research, these porcelain plates with similar motifs on the central medallion and the border were likely produced between 1560 and 1580, during the Jiajing and early Wanli periods.

Figure 6.

Chinese Porcelains, second half of the 16th century. Porcelain Room of Santos Palace, Lisbon. Inv. 150. Retrieved from Goldschmidt (1984).

Figure 7.

Chinese Porcelains, second half of the 16th century. Porcelain Room of Santos Palace, Lisbon. Inv. 124. Retrieved from Goldschmidt (1984).

Figure 8.

Chinese Porcelains, second half of the 16th century. Casa-Museu Dr. Anastácio Gonçalves, Lisbon. Inv. CMAG 12.

The visual and cultural connections which are established in this study have not been proven archaeologically, mainly because most of the influences are subtle, invisible, and almost imperceptible. However, it would be possible to find out the historical traces and discover their origins. According to the Rui André Alves Trindade, the representation of decorative elements alien to Western culture in the Chinese pieces which firstly arrived in Portugal aroused little interest, but the introduction of figurative motifs from Chinese paintings into porcelain decoration at the end of Jiajing period began to inspire Lisbon potters (Trindade 2015). The Shanshui motif with its peculiar visual language and poetic artistic conception became one of the favorite themes presented in Portuguese faience. Furthermore, the Santos Palace is a former royal palace, acquired by the Lencastre family in 1629, and this Lencastre collection with 263 pieces of Chinese porcelain marks several historical and artistic phenomena. Around 1580, several faience potteries in the parish of Santos-o-Velho, where Santos Palace is located, produced examples of blue and white faience with decorations inspired by Chinese porcelain. Moreover, the Lencastre family was the owner of the pottery on Rua da Madragoa, just meters from his palace. Therefore, we have adequate reasons to believe these Chinese porcelains served as models of inspiration for the faience potters nearby (Trindade 2015).

The application of the term “inspiration” in this study would be preferable to using the “imitation”, that is, as happens in the process of any cultural interaction when the Chinese porcelain became popular and widely accepted in Portugal, the Portuguese craftsmen transformed its iconography, created it through the prism of their own culture and ideology, and hybridized it with the occidental elements which are much more familiar to them. Dawn Odell makes a similar demonstration about the Dutch delftware and employs the term “domestication” to provide a new model to understand the reception of Chinese visual culture in seventeenth-century Europe (Odell 2018). On the grounds of the representation of the shanshui motif both on Portuguese faience and Chinese porcelain, it is noted through a contrastive observation and a descriptive analysis that Portuguese craftsmen did not adopt the Chinese artistic style; instead, they maintained their aesthetic preferences to manifest their vision of shanshui, and interpret his China in a Portuguese style, loyal to their mental values.

As demonstrated on the Portuguese faience dishes, inv. MNAA 2402 (Figure 2) and inv. MNAA 6781 (Figure 4), we summarize two main modes in which Portuguese craftsmen carry out their representation of shanshui motif on faience and they are, respectively, decontextualization and recontextualization.

The decontextualization is principally embodied in the appropriation and adoption of motifs and schemas. The Portuguese craftsmen chose to depict the shanshui motif in a graphic style, simplifying the Chinese motifs. They dedicated themselves to opting for those partial elements or incomplete details that tally with their own interests or attract their attention, not taking into consideration the intention of the original image or the whole structural relationship among each element. The Shanshui motif is a representation of an organic whole on porcelain. However, the elongated rock in a strange shape and exaggerated proportion depicted on the faience destroys the harmonious composition. A hermit monk in a long tunic holding his large parasol took the place of the classic scene Xie Qin Fang You. A traditional double-roofed Chinese pavilion was replaced by a turreted building with a flying flag, and a sampan full of Chinese interest was substituted by a sailing boat. It was quite difficult for Portuguese researchers in the faience area to identify the central set of this faience dish as a shanshui motif, even though it may well represent a piecing together of details borrowed from the shanshui motif on Chinese porcelain. For the Portuguese craftsmen, the integrity of the composition and the choice of familiar elements in their aesthetic preference took precedence over the rationality of the arrangement of all details.

Upon the decontextualization of the shanshui motif depicted on Chinese porcelain, the original image of the Chinese landscape was introduced into another context by recontextualization. Those borrowed elements were painted on the faience with less precision and attention but with confident and spontaneous brushstrokes, and the blank space of the image was filled with several scattered trees or bush branches that lead to a naturalistic impression of the scene. The result is almost recreation, giving the image a entirely different artistic conception of spontaneous but elaborate syncretism. Although the artistic conception of this faience dish is not reflected in the original image, it has a relationship with it, but a rebirth of the appropriated elements and composition of shanshui and its spiritual meaning in the cultural context where it is located. Although what we see is a slightly unskilled and awkward appropriation, the shanshui elements on Chinese porcelain have become the Portuguese decorative grammar—”Small Motif” on faience—and the East has also been moved to the West, resulting in hybrid production of creative freedom. The East and the West are intertwined in these pieces of artwork.

In this artistic miscegenation, the values of the culture and life of each period are witnessed, as if it were a trans-memorial ballast, reflecting as best as possible the client’s will and the craftsmen’s creativity, as if it were a container, transporting and exchanging an imaginary world in the thinking of a courageous people. The Portuguese began to establish their imagery about China according to what they have observed from the Chinese porcelain. To a certain extent, the image itself has become valid historical evidence.

The two dishes (Figure 2 and Figure 3), as a set of pieces, provide us a sense of how closely the Portuguese faience could adhere to Chinese porcelain and show us the ways these imitations strayed from the original models. However, even in a very closely matched resemblance, especially in its artistic composition and distinct decorative elements, the Portuguese craftsmen capture the similarity rather than the feel. In some cases, they are not “capable” of imitating the shanshui motif and just alter it for cultural reasons, transforming it into a particular artistic phenomenon, or they are self-consciously and intentionally trying to distinguish them from the original image on Chinese porcelain, demonstrating their bold imagination and the genius interpretation. In either case, “the imperfect imitation” and “the rough representation” demonstrate exactly their special view. Beyond the representation of the shanshui motif on two dishes and their counterparts on porcelain and faience, the question is the differences between the Portuguese view and the Chinese view.

4. The Differences between the Portuguese View and the Chinese View

Due to the discrepancy between imitation and originals and the autonomy of interpretation of the shanshui motif, we intend to summarize the differences between the Portuguese view and the Chinese view, to enunciate some particularities of the Portuguese view of Chinese culture, and to furthermore throw light on causality beyond representation.

4.1. The Vastness of the Void in Chinese Shanshui

Poetic vastness is considered one of the distinct and prospective characteristics of the Chinese shanshui painting. The technique of Chinese painting Liu Bai (literally means “that keeps a white space”) is a symbolic technique that Chinese painters use frequently.

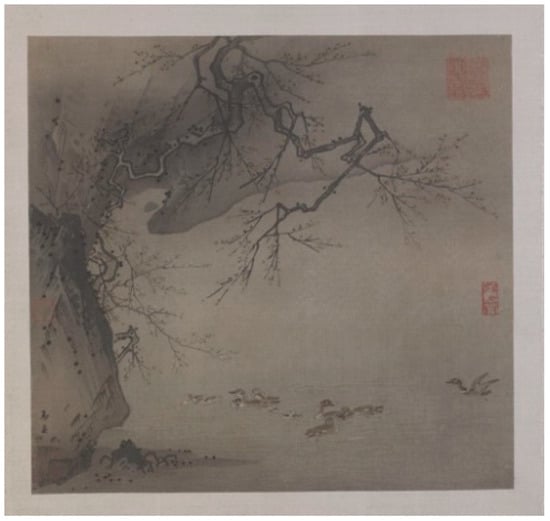

The central part of the Chinese porcelain dish, inv. MNSR 1829 (Figure 3) keeps several spaces empty. This artistic composition derives from traditional Chinese paintings, such as the paintings of Ma Yuan and Xia Gui of the Southern Song dynasty (1127–1279). Their paintings became famous and outstanding due to the composition of the picture, as they placed descriptive elements, such as landscape and human activity, in a small corner or half of the image, maintaining the maximal space for a broad, empty, and expansive sky.

In the painting Ducks in Water Beneath Blossoming Plum (梅石溪凫图) (Figure 9), Ma Yuan employs the typical diagonal composition, with the rocks and blossoming plum trees located in the upper left corner. The branches of the plum trees emphasize the formality of this composition, while the ducks on the lower right play an important role in balancing the image and completing the vibrant scene. Ma Yuan frequently used one corner to emphasize rocks or other elements, creating a contrast between reality and fiction, earning him the moniker “Ma Yi Jiao” (One-Corner Ma).

Figure 9.

Ducks in Water Beneath Blossoming Plum (梅石溪凫图). Ma Yuan. Palace Museum, Beijing.

In the painting Recluse playing qin by the water (临流抚琴图) (Figure 10), Xia Gui depicts a recluse or a literati peacefully playing qin, with the main design weight off to the right side and the left side of the picture left almost bare or just slightly painted with the misty and foggy shores. Xia Gui simplifies the composition, yet each section retains its own succinct and pristine visual image, earning him the moniker “Xia Ban Bian” (Half-Side Xia).

Figure 10.

Recluse playing qin by the water (临流抚琴图). Xia Gui. Palace Museum, Beijing.

Although porcelain dishes inv. CMAG 21 and inv. CMAG 22 (Figure 5a,b) have less space than the inv. MNSR 1829 (Figure 3), the Chinese craftsmen still reserve a space for imagining and traveling across the river. However, the Portuguese faience dishes, inv. MNAA 2402 (Figure 2) and inv. MNAA 6781 (Figure 4), present a vacui horror, which stray from the Chinese aesthetic. The whole image is filled with scattered and disorganized motifs, such as short branches, without a minimum space for “breathing”. It is known that Portuguese faience is a result of contact with a different culture, especially Islamic culture. This vacui horror may come from the Islamic mental tradition.

Van Thi Diep states in his article that this void is not understood in Western thought. It is intangible and inaccessible; it is nothing, but it can hardly be described as something (Diep 2017, p. 80). This incomprehension is influenced by Chinese philosophy, especially Taoism and Confucianism, and plays a considerable role in Chinese shanshui paintings. A traditional rule says the following: “In a picture, a third fullness, two-thirds emptiness” (Cheng 1994). Since a third of fullness corresponds to the Earth (terrestrial element) and two-thirds of emptiness to Heaven (celestial elements and emptiness), the harmonious proportion established between Earth and Heaven is the same as the one-man attempts to develop in himself since he also endowed with the virtues of Heaven–Earth (Cheng 1994, p. 89). The composition of the shanshui motif refers to an ancient Chinese culture, which considered life as an open “space” that could be cultivated. Self-cultivation is a process of personal development that, in light of Confucianism, means maintaining a balance between the inside and the outside, the self and the other. Zhu Xi (1130–1200), the famous Song Neo-Confucian philosopher clarified that “Heaven and Earth (the cosmos) have the heart and mind of creativity, and this same heart and mind are attained in the creation of humans and things” (Quoted in He 2014).

Applying this ideology to art, the Chinese used artistic creativity to express the unity of Heaven and Earth in mind. The unity of Heaven and Earth does not lead to concrete mountains or water, but to the merging of the universe, nature, and life. Chinese painters and scholars studied nature until they could reach the point of being able to capture the heart of nature and absorb its spirit into their mental world. After all, the shanshui motif on porcelain and Chinese paintings is an intersection between the interior state of the painter and the process of cosmic fusion with nature.

The vastness of the shanshui creates a particular and strong power. One power manifests itself in the desire for tranquility, in nostalgia that ensues painful experience, in isolation that refuses the agitated reality, and in spirituality that frees emotions from these periods of disturbance. Thus, as long as these vacant spaces remain, they will seem to be awaiting our arrival (Sullivan 2007, p. 419). Observers become subjects of the image shanshui, filling the poetic vastness with an imaginary journey and a spiritual experience.

4.2. The Spatial Sense of Infinity

In traditional shanshui paintings and shanshui motifs on porcelain, mountains occupy the most significant space, firmly capturing our attention. This artistic composition brings us a feeling of solemnity and monumentality and a sense of infinite space. In the preface of the book Hua Shanshui Xu (Preface on shanshui Painting), Zong Bing declares that the pupil of one’s eye is small, yet its range of vision is infinite; although the silk used for a painting is only a meter or so in width and length, the view it encompasses can extend to thousands of miles. However, Portuguese faience does not provide this opportunity to travel or the sense of monumentality. The Portuguese craftsmen do not forget the perspective representation or forget the far and near distance. However, they pay more attention to the detailed portrayal than to the overall feeling of the picture, as if all the elements depicted in the faience exist in a framed dramatic image.

Perspective is one of the main factors that determine the difference in a spatial sense. Master painters apply the view of the three distances, first formulated by the painter and theorist Guo Xi (around 1000–1087), who presented it in the book Linquan Gaozhi (Lofty Record of Forests and Streams). He describes three distances in the shanshui painting: high distance (高远), which observes between the bottom of the mountain and its peak; level distance (平远), from a near elevation to a far one; and deep distance (深远), from an adjacent ridge to a distant one.

Instead of applying the isometric perspective, which Western painters are familiar with, Chinese shanshui painting consists of several perspectives. Sullivan says that Chinese landscape painting has its techniques—the use of atmospheric perspective (Sullivan 2007): the most distant objects occupy the top positions and are painted smaller and less distinct; he also indicates that the scroll intends to involve the viewer’s imagination at an almost physical level, creating a feeling of wandering through a scene rather than absorbing it from a fixed point (Sullivan 2007, p. 408). He Jinli complains that perspectives need to be unstable to create a complete feeling (He 2014, p. 18).

Sullivan also explains that “Scientific perspective involves a view from a determined position and includes only what can be seen from that single point” (Sullivan [1950] 2008, p. 176), which is reflected in the Western painting and particularly in the dish of Portuguese faience (Figure 2). While looking at the central motif obtained from a single perspective, we do not notice the other motifs, nor do we feel compelled to discover the other details. However, the shanshui motif depicted on Chinese porcelain invites us to travel through the natural landscape. This freedom of looking and traveling through the three distances of perspective causes a unique experience for observers and creates a great sense of monumentality and infinity.

4.3. The Collective Sense and Individualism

The collective sense is another essential feature of the shanshui motif, which was difficult to understand for Portuguese craftsmen. This attribute is represented in three main aspects: time, space, and the human figure.

Whether Chinese Shanshui painting or shanshui motif on porcelain, a collective sense of the season instead of a particular day or any specific time is usually described. In virtue of painting the details of mountains, rivers, trees, clouds, etc., the Chinese artists describe the different seasons and the emotions associated with those motifs. As Guo Xi explains in his book, “Mountains in spring are saturated with mist and clouds, make feel lively; mountains in Summer are full of green and shade, make people feel bright and open; mountains in Autumn are clear and vivid, make people solemn; and mountains in Winter are static and gloomy, make people quiet and lonesome” (Quoted in Law 2011, p. 375).

The Chinese porcelain pieces mentioned above seem to allude to spring. The peaceful river, the mountains, lush shrubs, and human figures represent a quiet life. However, in most Western paintings or images depicted on faience, artists or craftsmen mainly focus on moments or episodes. In Western landscape painting, the masters like to paint the storm, to capture the tense moment, create the destructive power of nature, and represent relaxing environments. Landscape painting follows the rules of time strictly. The central image of the faience dish (Figure 2) shows a human figure fixed in a scene as if it was a portrait. Conversely, in the Chinese shanshui motif, time is more diffuse, broader, unlimited, and varying with will, emotion, experience, and the emotion of the observers.

As for space, science and technology play a significant role in the development of western landscape painting. Painters also show their philosophical interests, but most of the work seeks verisimilitude and vividness. Thus, it is not difficult to identify the landscape sketched in a painting by conferring it with reality.

In turn, Chinese shanshui painting and shanshui motif on porcelain aim to convey the experience of “being in nature” instead of “observing nature”, emphasizing the concept instead of the visual manifestation. In the book The History of Art, Ernst Gombrich accurately explains this idea: “Chinese artists did not go out into the open, to sit down in front of some motif and sketch it. They even learned their art by a strange method of meditation and concentration in which they first acquired skills in ‘how to paint pine-tree,’ ‘how to paint rocks,’ and ‘how to paint clouds’, by studying not nature but the works of renowned masters. Only when they had thoroughly acquired this skill did they travel and contemplate the beauty of nature to capture the moods of the landscape (...) The Chinese, therefore, consider it childish to look for details in pictures and then compare them with the real world. They want, rather, to find in them the visible traces of the artist’s enthusiasm” (Gombrich 1972, p. 111). In Chinese shanshui, the natural objects transmit emotions rather than the mirror of reality. In many cases, mountains are depicted as more grandiose and more extensive than the real mountains, and the rivers are more peaceful and longer than the real rivers. The Chinese artists and craftsmen create their works by using the techniques of the ancient masters and combining their personal feelings.

Most of the images of shanshui motifs on Chinese porcelain cannot be accurately identified since they are not real, but only reflections of feelings. The appearance of porcelain painted with the landscapes based on reality is the result of custom-made foreign order with the motifs of their Western houses, palaces, and gardens.

The discoveries of science and technology provided Western painters the precision of the concepts of time and space, and in the meantime, reinforced verisimilitude, especially from the 17th century. However, Chinese painters, influenced by their philosophy, depicted the shanshui from the abstract and general characteristics instead of the concrete and individual characteristic. The essential objective of the Chinese shanshui painting is to cultivate the spirit rather than produce a mimetic illusion through the accumulation of details. This feature can also be observed in the treatment of the human figure, in its expressiveness, and in the relationship between the human figure and the natural landscape.

4.4. The Expressiveness of the Human Figure

Considering the shanshui motif on dishes of Chinese porcelain (Figure 1, Figure 3, Figure 5a,b, Figure 6, Figure 7 and Figure 8), human figures are inconspicuous and diminutive in comparison with other shanshui decorative elements and overall image. While natural motifs are meticulously painted, the human figures are outlined in simple lines, in many cases, without “face”. On Chinese porcelain, the human figure appears with the function of adorning the landscape. These little human figures show a harmonious coexistence between humankind and nature. However, not being aware of it, on dish inv. MNAA 2402 (Figure 2) and dish inv. MNAA 6781 (Figure 4), Portuguese craftsmen sought to draw their eyes, nose, and mouth, among other organs to make them more convincing. Furthermore, the exaggerated proportion of human figures may destroy the sense of harmony in the picture between humanity and nature.

This ambiguous representation of human figures has its logical reasons and expresses the craftsmen’s or painters’ subtle intentions. They hope to present an ideal lifestyle of literati through daily activities such as drinking tea, playing musical instruments, playing chess, making farewell to family members, and reading poetry in the pavilion, among other activities, thus showing their real interests and their desired life. However, the human figures, sketched by literati (wen ren), are also a social representation of the group to which the scholar painters belonged. At times, these human figures accurately embody their painters, reflecting their dignity and philosophical convictions. In addition, these tiny human figures are not only standing in the shanshui paintings that we discovered, but also those people who flood our minds while we appreciate the scene. They are all people-as-landscapes and show that there are many more people in shanshui, in the real world, and in our minds.

Since human figures are the projection of their painters, it is not necessary nor should be depicted with an identifiable face. There are two main reasons: first, the Chinese literati have a secure connection with the imperial court, and most of them were dissatisfied with feudal dominance. With such a sensitive political issue, it is much safer to draw the figures without the identification, that is, the “face”. Second, an unidentified figure represents the revolted community against the cruel reality of feudal dominance, which aims to present an alternative ideal life. Moreover, human figures have an ornamental function in the Chinese shanshui motif.

4.5. The Relationship between the Human Figure and the Natural Landscape

As explained in the previous section, the human figure appears on porcelain and in Chinese paintings to adorn the landscape. On Chinese porcelain, human figures are tiny and comprise one part of the shanshui motif into which they integrate. Oppositely, the human figure on the Portuguese faience assumes a gigantic proportion in the center of the image, as if they were watching a show on the stage. The figure with his parasol depicted on faience does not reflect the feeling for nature or the desire to stroll along with the natural beauty. One conjecture is presented here: the disproportionate human figure in the composition of the picture probably shows the individualism in Western thought.

Ancient Chinese philosophers consider the different natural elements as all part of an indivisible whole instead of separated objects. In Taoist theory, Man is only a humble tiny entity of the whole (Law 2011, p. 379). Human figures are not willing to conquer nature; neither are the gnats that are living at the bottom of the natural world without the ability to revolt. As illustrated in Taoism, between Heaven and Earth, I am but as a small stone or a small tree on a great hill, so long as I see myself to be this small, how should I make much of myself (Legge 1962, p. 376). This harmonious unification between the human figure and nature precisely demonstrates the essence of Chinese philosophy: “the unification of the cosmos and the human being”.

This theory about the harmonious and reciprocal relationship between the human figure and nature was formulated by Zhuangzi, a Taoist philosopher who lived around the 4th century BC. In Qiwu Lun (The Adjustment of Controversies) from the Inner Chapters, Zhuangzi composes the following description, translated by James Legge. “Under Heaven there is nothing greater than the tip of an autumn down, and the Tai mountain is small. There is no one more long-lived than a child which dies prematurely, and Peng Zu did not live out his time. Heaven, Earth, and I were produced together, and all things and I are one.” (天下莫大于秋豪之末, 而大山为小; 莫寿乎殇子, 而彭祖为夭. 天地与我并生, 万物与我为一.) The English translation was retrieved from the Chinese Text Project, which is an online open-access digital library created by Donald Sturgeon). The emphasis of Zhuang Zi is on letting the “self” go, keeping the “self” equal to all things, and making the “self” one with all things. The realm of obedience to the natural order, which contains all natural things, is the same as the realm of “I” and “Heaven” and leads to valuable ideas of equality and “non-anthropocentric” naturalism. As Chiayu Hsu reveals, the significance of “myriad things” puts forward a philosophy of life concerning how all different things exist as authentic unto themselves and preserving the immanent values of each individual (Hsu 2019, p. 4).

And in the Han dynasty, this theory was developed by Dong Zhongshu (179–104 BC), a Confucian philosopher who emphasized the unification of cosmos humankind by alluding to “resonance between the cosmos and the human being” (Tian Ren He Yi). In Chunqiu Fanlu (Luxuriant Gems of The Spring and Autumn Annals), Dong Zhongshu stated that “if a grouping is made according to kind, Heaven and human being are on.” (以类合之, 天人一也) (Dong 2016, p. 414).For the first time in Chinese history, Dong Zhongshu systematized theories based on Confucianism and applied them to the theory of imperial power. He considers that Heaven, not the emperor, has absolute power, dominates the world, and decides the rules of nature and human lives. If dominators implement a policy of benevolence, the weather conditions would become favorable, and the people would also live peacefully. This harmony between the cosmos and humanity greatly influenced aesthetic value and artistic creation.

Depending on a different understanding of Heaven and man and the need for political advocacy, the term Tian Ren He Yi may have had different ways of expression in history. However, the “unification of the cosmos and the human” theory or the “resonance between the cosmos and the human” is not just a philosophical thought, but a life motto and a mental state that resonates with the Chinese shanshui motif especially demonstrated in the shanshui motif with the human figure. Shanshui is more than the representation of nature, it is a way of experiencing being in nature. We are all invited to be in this nature and become these human figures in that painting. Sullivan illustrates these figures poetically and says that they seem to have arrived in the painting slightly ahead of us and to be lingering there a moment as well (Sullivan 2007, p. 417).

4.6. The Story behind the Shanshui

In Chinese shanshui, there are always a cultural meaning and a connotative meaning behind the individual motifs. The most important characteristic is the story behind the shanshui. As shown in Zong Bing’s story, shanshui painting is not carried out in any natural scene. It is a conceptual perception obtained from several episodes, experiences, and life stories.

On the Chinese porcelain dishes (Figure 3, Figure 5a,b, Figure 6 and Figure 8), considering the characteristics of the two figures and the oblong object, we infer that the depiction of the two figures crossing the bridge is based on the historical scene—Xie Qin Fang You (Taking a qin to visit a friend). The image alluding to Xie Qin Fang You derives originally from the story of Yu Boya and Zhong Ziqi in the spring and autumn period (from approximately 770 to 476 BCE), recorded in the classic text entitled Lüshi Chunqiu (Master Lü’s Spring and Autumn Annals). It is said that Yu Boya was good at playing Guzheng, while Zhong Ziqi was good at listening to music and could even hear the emotion and thought conveyed by Boya’s music. Afterward, Boya, holding his musical instrument, visited Ziqi until he died. The news of Ziqi’s death distressed Boya and led him to abandon his Guzheng, saying that he would never find his Zhiyin (知音, soul mate) (Tian et al. 2003). The word Zhiyin literally means knowing the song; it relates to the story of Yu Boya and Zhong Ziqi. Today, this term is widely used to describe intimate friendship. The story of Yu Boya and Zhong Ziqi was constantly developed and gradually constituted the stylized motif of Xie Qin Fang You. Initially, Xie Qin Fang You only appeared in the form of Chinese painting on rice paper (Xuan Zhi) and later became a famous motif on Ming Dynasty porcelain. Furthermore, the theme only expresses friendship, but also expresses the elegant feelings and noble souls of literati, that is, to stay away from the hustle and bustle of the world and its vulgarities, return to the embrace of nature, and reflect the harmonious relationship between human and nature, enriching the expressive context of the “literati painting”.

Therefore, the shanshui motif is not just a natural scene of mountain and water but a hope in the real world. It shows some historical episodes, to which the Chinese attribute a representative value and a life lesson. The essence of Chinese paintings depends on the revelation of the truth. The numerous shanshui scenes on Chinese porcelain and Chinese paintings were made in the transition period (1620–1683). When the Mongol invaders conquered the Chinese territory and imposed the policies of the Ming dynasty, many literati, who had been the empire’s backbone, chose to isolate themselves to have a rural life, instead of collaborating with the new dominant power. In works of art, they portray their inner exiles and regard the shanshui as an exit to move away from that hectic society. They intend to create a space where people can get in touch with their idealized world. As for them, shanshui is an essential spiritual condition for survival.

It would be very difficult for Portuguese faience craftsmen to know the history behind the shanshui motif, therefore, they tended to decontextualize it and conceived it as a simple and timeless figuration of China, and moreover, they had the tendency to recontextualize it with the rebirth of artistic conception, which is much more familiar to Western taste. They tried to borrow the theme but did not embody the ideal world that the Chinese people expected and desired.

5. Conclusions

Along with the development of the 21st century’s new perspectives, the abundance of traditional Chinese art proves to be an extraordinary cultural resource for exploring and integrating into our modern life. It is up to researchers how to present those historical marks presented in the intercultural dialogue and how to deepen the historical and cultural contexts behind the beauty of porcelain, silk, lacquer, biombo, among others.

Chinese porcelain, being the first globalized product, which was initially imported and then produced in Portugal, deeply influenced the manufacture of Portuguese art and its artistic style, especially the faience. While Portuguese Faience can be recognized as one of the most significant post-medieval productions, and those produced in the seventeenth century with Chinese porcelain influence could be considered one of the most sui generis artistic expressions and recognizable identity values of Portuguese art, it remains little known at the international level. Due to the high demand, Portuguese craftsmen produce the faience decorated with Chinese motifs. Chinese influence was one that most influenced seventeenth-century Portuguese.

From Chinese porcelain to Portuguese faience, a particular dialogue took place between the two cultures. The present study provides a comparative analysis of shanshui motifs depicted on Chinese porcelain and Portuguese faience and proposes two modes—decontextualization and recontextualization—in which Portuguese craftsmen applied their representation of shanshui motif. Those appropriations and transformations to which this theme and several elements have been subjected reflect, subtly and poetically, the cultural particularities of China and Portugal and their social contexts and worldviews.

From the general aesthetic point of view, the shanshui depicted on Portuguese faience is almost a coarse and crude imitation and even lacks in aesthetic value, but the diversity of imagery beyond representation is evidence of the complex visual vocabulary that seventeenth-century Portuguese viewers had at their disposal in imagining the “China”. The Chinese shanshui maintains its essence: it offers an imaginary and spiritual world. The value of shanshui does not depend on the similarity to real nature, but on the ability to transform nature into a worldview,

a moral expression of the craftsmen, and an emotional source for the viewer.

Each person has his shanshui vision, which is also mostly the result of the surrounding culture. The shanshui reveals China and is also shown in the reinterpretations of Portuguese faience and other European productions, such as Delftware, European tapestry production, and English garden design. The relationship between the different civilizations presented in this theme gives it value and uniqueness and demands a thoughtful interpretation.

Furthermore, as we demonstrate in this study the historical connection between the Santos Palace and Lencastre family’s pottery, that is, the connection between the Chinese export porcelain and the manufacture of Lisbon faience. If there are two historical phenomena with morphological similarities, it is very likely that there is an actual historical connection between them. The reason why we have not found this historical connection is not due to the limitations of historical disciplines, but due to the limitations of each of our individual knowledge. However, the aim of this study is not to become archaeological evidence, but to open a new perspective of thought, and to renew the knowledge of Chinese culture and its power of intercultural communication.

This article is a comparison of Portuguese faience and Chinese porcelain with similar compositional qualities. We hope to systematically analyze this group of porcelain and faience with shanshui motif and draw out the possibility of future in-depth research. A further dimension introduced by this study is that of the transcultural perspective on art (Juneja and Grasskamp 2018; Li 2020), which is investigated as a catalyst of object encounters across cultural and geographical distances. Through a series of comparative analysis studies on Chinese porcelain and Portuguese faience, we hope to expand the research boundaries of the original disciplines, employ diverse theories and research ideas, and establish the connection between art and images. This will allow us to appreciate historical traces and the moments of encounter and (dis)encounter, and to comprehend the human condition in an integrated, inclusive, and dynamic manner.

Author Contributions

Writing—original draft preparation, M.G.; writing—review and editing, M.G. and R.M.; funding acquisition, M.G. and R.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by Portuguese Art Fundo do Ensino Superior de Macau; grant number: CP-MUST-2020-07.

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Portuguese Art (CP-MUST-2020-07) Fundo do Ensino Superior de Macau.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Calado, Rafael Calado. 2002. A brief history of faience in Portugal. In Itinerary of Faience of Oporto and Gaia. Org. and Coord. Museu Nacional de Soares dos Reis. Collab. Câmara Municipal do Porto. Porto: MNSR, pp. 13–26. [Google Scholar]

- Casimiro, Tânia Manuel. 2010. Faiança Portuguesa nas Ilhas Britânicas (Dos Finais do Século XVI ao Início do Século XVIII). Ph.D. dissertation, Nova University of Lisbon, Lisboa, Portugal. [Google Scholar]

- Casimiro, Tânia Manuel, Rosa Varela Gomes, and Mário Varela Gomes. 2015. Portuguese faience trade and consumption across the world (16th–18th centuries). In Global Pottery—First International Congress on Historical Archaeology & Archaeometry for Societies in Contact. Edited by Jaume Buxeda I Garrigós, Marisol Madrid I Fernández and Javier G. Inanez. Oxford: British Archaeological Reports, pp. 67–79. [Google Scholar]

- Cheng, Franços. 1994. Empty and Full: The Language of Chinese Painting. Translated by Mchael H. Kobn. Boston and London: Shambhala. [Google Scholar]

- Curtis, Julia B. 1995. Chinese Porcelains of the Seventeenth Century: Landscapes, Scholar’ Motifs and Narratives. New York: China Institute Gallery. [Google Scholar]

- Diep, Van Thi. 2017. The landscape of the Void: Truth and magic in Chinese landscape painting. Journal of Visual Art Practice 16: 77–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, Zhongshu. 2016. The Meaning of Yin and Yang. In Luxuriant Gems of the Spring and Autumn. Edited and translated by Sarah A. Queen and John S. Major. New York: Columbia University Press, pp. 414–15. Available online: http://www.jstor.org/stable/10.7312/dong16932.58 (accessed on 22 August 2022).

- Flores, Jorge Manuel. 1998. Um Império de Objectos. In Os Construdores do Oriente Português: Ciclo de Exposições Memórias do Oriente. Edited by Mafalda Soares Cunha. Lisboa: Comissão Nacional para as Comemorações dos Descobrimentos Portugueses, pp. 24–70. [Google Scholar]

- Goldschmidt, Daisy Lion. 1984. Les Porcelaines chinoises du palais de Santos. Arts Asiatiques 3: 3–72. Available online: https://www.persee.fr/doc/arasi_0004-3958_1984_num_39_1_1616 (accessed on 25 April 2022).

- Gombrich, Ernst. 1972. The Story of Art, 13th ed. New York: Phaidon Press Limited. [Google Scholar]

- He, Jinli. 2014. Continuity and Evolution: The idea of “Co-creativity” in Chinese Art. ASIANetwork Exchange: A journal for Asian Studies in the Liberal Arts 21: 15–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsu, Chiayu. 2019. The Authenticity of Myriad Things in the Zhuangzi. Religions 10: 218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Juneja, Monica, and Anna Grasskamp. 2018. EurAsian Matters: An Introduction. In EurAsian Matters. Transcultural Research—Heidelberg Studies on Asia and Europe in a Global Context. Edited by Anna Grasskamp and Monica Juneja. Cham: Springer, pp. 3–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krahl, Regina. 1986. Chinese Ceramics in the Topkapi Saray Museum, Istanbul Vol. II. London: Sotheby Parke Bernet Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Law, Sophia. 2011. Being in Traditional Chinese Landscape Painting. Journal of Intercultural Studies 32: 369–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Legge, James. 1962. The Texts of Taoism. New York: Dover, vol. 1. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Jun. 2020. Kuawenhua de Meishu Shi: Tuxiang Yiji Chongying 跨文化的艺术史: 图像以及重影 [Transcultural History of Art: On Images and its Doubles]. Beijing: Peking University Press. [Google Scholar]

- McElney, Brian S. 1979. The Blue and White Wares—post 15th Century. In South-East Asian and Chinese Trade Pottery. Edited by Sir John Addis. Hongkong: Oriental Ceramic Society, pp. 34–36. [Google Scholar]

- Meco, José. 2018. “Porcelanas” de Lisboa—O Encanto da Faiança Portuguesa do Século XVII. In Lisboa na Origem da Chinoiserie: A Faiança Portuguesa do Século XVII Colecção Mário Roque. Edited by Mário Roque. Lisboa: São Roque Antiguidade & Galeria de Arte, pp. 8–13. [Google Scholar]

- Moncada, Miguel Cabral de. 2008. Faiança Portuguesa, séc. XVI a séc. XVIII. Lisboa: Scribe. [Google Scholar]

- Monteiro, João Pedro. 1994. A influência Oriental na Cerâmica Portuguesa do Século XVII. Lisboa: Electa. [Google Scholar]

- Odell, Dawn. 2018. Delftware and the Domestication of Chinese Porcelain. In EurAsian Matters: China, Europe, and the Transcultural Object, 1600–1800. Edited by Anna Grasskamp and Monica Junej. Cham: Springer, pp. 175–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pais, Alexandre Nobre. 2012. “Fabricado no Reino Lusitano o Que Antes nos Vendeu tão caro a China”: A Produção de Faiança em Lisboa, Entre os Reinados de Filipe II e D. João V. Doctoral dissertation, Portuguese Catholic University, Porto, Portugal. [Google Scholar]

- Pais, Alexandre Nobre, and João Pedro Monteiro. 2003. Faiança Portuguesa da Fundação Carmona e Costa. Lisboa: Assírio & Alvim. [Google Scholar]

- Pais, Alexandre Nobre, and João Pedro Monteiro. 2013. O exótico na faiança e azulejo do século XVII. In O Exótico Nunca Está em Casa? A China na Faiança e Azulejo Portugueses (Séculos XVII–XVIII) [The Exotic Is Never at Home? The Presence of China in the Portuguese Faience and Azulejo (17th–18th Centuries)]. Edited by Alexandra Curvelo. Lisboa: Museu Nacional do Azulejo, pp. 59–79. [Google Scholar]

- Queiroz, José. 1907. Ceramica Portugueza. Lisboa: Typografia do Anuario Commercial. [Google Scholar]

- Roque, Mário. 2018. A Escolha dos Oleiros: Uma miscigenação ao gosto da época. In Lisboa na Origem da Chinoiserie: A Faiança Portuguesa do Século XVII Colecção Mário Roque. Edited by Mário Roque. Lisboa: São Roque Antiguidade & Galeria de Arte, pp. 33–35. [Google Scholar]

- Sandão, Arthur. 1976. Faiança Portuguesa: Séculos XVIII e XIX. Porto: Livraria Editora Civilização. [Google Scholar]

- Santos, Reynaldo dos. 1970. Oito Séculos de Arte Portuguesa. Lisboa: Empresa Nacional de Publicidade, vol. 3. [Google Scholar]

- Sebastian, Luís. 2010. A produção Oleira de Faiança em Portugal (Séculos XVI–XVIII). Doctoral dissertation, Nova University of Lisbon, Lisboa, Portugal. [Google Scholar]

- Shangraw, Clarence, and Edward Von der Porten. 1997. Kraak Plate Design Sequence 1550–1655. Benicia: Drake Navigators Guild. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, Robert. 1968. The Art of Portugal 1500–1800. New York: Meredith Press. [Google Scholar]

- Ströber, Eva. 2011. Literati and Literary Themes on Porcelain from the Collection Keramiekmuseum Princessehof Leeuwarden. Aziatische Kunst 41: 12–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sullivan, Micheal. 2007. The Gift of Distance: Chinese Landscape Painting as a Source of Inspiration. Southwest Review 92: 407–19. Available online: http://www.jstor.org/stable/43472830 (accessed on 15 September 2021).

- Sullivan, Micheal. 2008. The Arts of China, 5th ed. Berkeley: University of California Press. First published 1950. [Google Scholar]

- Tian, Zibing, Shusheng Wu, and Qing Tian. 2003. Zhongguo Wenyang Shi 中国纹样史 [A History of Chinese Decorative Designs]. Beijing: Higher Education Press. [Google Scholar]

- Trindade, Rui André Alves. 2015. Aqua: Faianças da Coleção do MNAA: Sala do Tecto Pintado. Lisboa: MNAA (Museu Nacional de Arte Antiga). [Google Scholar]

- Xiong, Huan. 2006. The Study of Kraak Ware. Palace Museum Journal 3: 123–34. [Google Scholar]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).