Abstract

This article presents an interpretation of the works by the Israeli–Druze photographer Amira Ziyan, focusing on a series of photographs from 2017. These portray reenactments of actions identified with traditional roles of women in Druze society, such as cooking and cleaning. Employing a unique visual language and choice of form and content, the artist depicts a confrontation between a clear set of rigid and traditional boundaries and values and a contemporary, post-modern reality in which these boundaries and values are blurred. The interpretive reading proposed here describes a synergy between visual codes of minorities and accepted visual codes of their surrounding pervasive culture in contemporary Israel. Ziyan’s work offers a glimpse into visual codes of “otherness” that express the inner world of an artist who grew up on the margins of society but strove to be accepted as an essential part of its main artistic current. Focusing on this perspective contributes to ongoing discourse regarding contradictions inherent in Israeli society and identity.

1. Introduction

In a series of photographs of women created from 2017, the Israeli–Druze photographer Amira Ziyan represents her idiosyncratic cross-cultural self-determination as she constructs a set of distinct visual codes.1 These serve to highlight her experience of tension between “conformity” and “otherness”.2 This article focuses on the visual semantics of an artist nurtured at the margins of society, while striving to be accepted into its artistic mainstream. It is argued that Ziyan’s “split-reality” experience and the system of internal contrasts typical of her work are expressions of latent depth currents in Israeli society and questions of identity.3

The visual language of the series, as well as its iconographic content, communicates the photographer’s perspective on the cultural world of the Druze minority in Israel and its complex relationship with mainstream Israeli culture. Most photographs in Ziyan’s series depict female characters engaged in household activities, such as cooking and cleaning, traditionally associated with the roles of women, not only in Druze culture but in all traditional, patriarchal societies.4 Some of the actions, such as sports or reading, are identified with women’s liberation and rebellion against patriarchal authority. In all cases, the photographs are, first and foremost, non-apologetic and demonstrate impertinent reenactments that do not seek to be perceived as documentary.

This duality between reenactment and documentation underlies the entire series and is a source of its compelling power. I argue that an intricate weave of dualities that characterizes the entire series forms a visual code that represents Ziyan’s personal experience. In each of the photographs, a complex synergy of three strata can be traced: content, the basic elements of visual language, and mode of representation.5

In terms of content, a dichotomy emerges between the actions identified with traditional female roles and those identified with rebellion against conventions and patriarchal authority. Moreover, duality is manifest in the decision to present most of the characters by their first names alone (enabling the viewer to empathize with the character), while simultaneously avoiding any possibility of identifying the real-life individual (thus creating distance and generalization). As far as her basic visual elements, Ziyan weaves a series of contrasts between light and dark, flat and infinite space, employing intense stylish contrasting colors to form compositions with no clear boundaries and obscure spatial relations. Finally, in terms of mode of representation, Ziyan’s technical use of the camera and her unique visual language also reveals a synthesis of internal contradictions between two poles inherent in the medium of photography. On the one hand, its power to capture and preserve the reality of any given moment, and on the other hand, the power to mold and create new alternatives. Ziyan’s photographs exist in a twilight zone between these poles, without offering a clear resolution.

This synthesis of opposing forces is reflected both in the Druze cultural context in general and in the life of the artist herself. The Druze are an insulated community, with their own cultural, behavioral, and secret religious codes; however, they also aspire to fully integrate into Jewish–Israeli society more than any other minority community. This contradiction raises intricate questions regarding the status of the Druze community and its relationship with Jewish and Israeli culture, casting a different and challenging light on both sides of the equation, the pervasive culture of the majority, and the marginal culture of the minority.6

Furthermore, as noted above, the series of works in question focuses on women, a group with unique characteristics and problems in traditional Druze society. The unusual status of Druze women is reflected both in Ziyan’s personal biography and in the language and visual codes she developed in her photographs. As we will see below, these, too, are characterized by a series of internal contradictions and a synergy of contrasts.

By deciphering the visual codes in Ziyan’s photographs, I seek to understand their complex synergy and how the artist constructs a system of representation that repeatedly contradicts itself until it nearly loses its connection to reality. I will demonstrate how she offers the viewer a focused “visual code-intensive” experience, while simultaneously breaking new ground in the Druze community as one of the most intriguing photographers and creative artists in Israel today.

2. Basic Principles and Visual Codes

Before discussing the series of works from 2017, it is worth discussing Red Dress (Figure 1) from 2016, a photograph that embodies the basic principles and visual codes of Ziyan’s art, and is probably the most widely recognizable of her works. It depicts a long dress hanging from a broad grey concrete column. The column, in the middle of a bare patio, divides the composition in two. Houses of the village of Yarka appear in the background on the far right; over on the left side, a wild mountain landscape looms somewhat closer. The dress appears to consist of two states of matter. The top, against the column, is solid and static, but the lower the eye falls, the more the dress loses its solidity and morphs into a reddish glow, giving the impression of movement. It seems to release its grasp on reality, blowing in a breeze toward the natural greenery on the left.

Figure 1.

Amira Ziyan, Red Dress, 2016. Photograph mounted on Dibond, 60 × 90 cm, by courtesy of the artist.

In Red Dress, one senses the synergy of contrasts referred to above. First exhibited in 2016 in a one-woman show entitled “On Exposed Concrete”, curated by Avshalom Levi at the Cabri Gallery the photograph was taken on the patio of the artist’s sister’s house in Yarka (Levi 2016). The visual codes in the picture illustrate the dialectical space in which Ziyan’s photography has existed from the start, and which operate on various levels, from the technical to underlying personal and cultural meanings. According to the artist herself, this work explores the complex relationship between Ziyan, represented by the dress, and her father, represented by the column.7 Connotative meanings arising from the confrontation between the dress and the column allude to broader cultural contradictions, such as material vs. spiritual, nature vs. civilization, masculinity vs. femininity, past vs. present, near vs. far, and personal vs. cultural. The treatment of visual elements is characterized by contrasts between grays and vivid red, hard and soft, a series of sharp geometric shapes and supple amorphic undefined ones, movement and stasis. The mode of representation makes use of the camera’s limitations, such as shutter speed and its relationship to movement, the appearance and disappearance of objects, sharpness vs. blurring, etc. These observations also apply to other works by Ziyan.

American curator Charlotte Cotton makes an observation which may shed light on our interpretation of Ziyan’s visual codes. Cotton deals with how contemporary photography challenges the basic, historic assumptions of photography. According to her, the stereotype of the photographer lurking for a defining moment to cut out from the non-stop sequence of everyday reality in order to make a temporarily meaningful statement is no longer relevant. Instead, contemporary photography refers to the camera as a tool that allows the photographer to bring forward insights as to how he or she grasps and experiences reality. In Cotton’s words, it is “A strategy designed not only to alter the way we think about our physical and social world but also to take that world into extraordinary dimensions” (Cotton 2014, p. 9).

Cotton locates the origins of this approach in “conceptual art” of the 1960s and the 1970s. During this period, she claims, photography became a central tool in the hands of a wide variety of creators, whose motivations were quite different from those of the earlier and other artists who used cameras. The conceptual artists’ interest shifted from the ideal of virtuoso “artistic” photographer, to the idea that the action depicted in the photograph, more than its style, is the significant artistic act. According to Cotton, one can find a blend of these ideas in contemporary photography, with the return of stylish artistic strategies (ibid., pp. 21–23). This particular synthesis of contrasts, as we will see later, is a central characteristic of the visual codes in Ziyan’s photography.

3. Personal Journey Dualities

The dialectical contrasts inherent in Ziyan’s photographs are reflections of contradictions in her personal life. Her road from a rigid, traditional, patriarchal society to photography and creative art was not an easy one, a fact she reveals in a 2018 interview titled “I Gave Up a Private Life for Art” (Weinberg 2018). Although she rebelled against the traditions in which she was raised, they remain a concrete presence, an anchor of reality, both in her photographs and in her life, much like the column in Red Dress. The constant friction between the artist and society affords her works their most profound meaning. In the catalogue of the exhibition “Crystal Palace” at the Umm el-Fahem Art Gallery in 2018, Sayid Abu Shaqra wrote: “I found in her contrasting feelings and desires: on the one hand, a desire to preserve tradition and a sense of belonging, and on the other hand, a desire to break through the barrier of repression that verges on a sense of dislocation. In effect, the contradictory desires stem from a sense of dislocation” (Abu Shaqra 2018, p. 21).

Ziyan was born in the village of Yarka in 1977, one of 12 children raised in a traditional Druze family. Her authoritarian father’s dominance and the complex relationship between the two was illustrated powerfully in Red Dress, discussed above. He provided support and strength on the one hand, but on the other hand was an unchanging and immovable grounding force that kept her from “flying” on the wind to emotional realms of self-expression where she could escape from everyday life, if only briefly.

As long as her father remained in control, Ziyan refrained from any creative activity. He firmly opposed her desire to study, primarily for reasons of modesty and tradition, conditioning her academic education on her engagement to a man of his choosing.8 Left with no choice, she agreed, although she had no feelings for her intended husband. In 1999, she began to study chemical and industrial engineering on the understanding that she would continue to work in her father’s concrete factory (Ziyan 2014). This was the first meaningful step she took toward self-fulfillment. Just before graduating, she called off her engagement.9

Ziyan arrived at photography and creative art only after her father suffered a stroke. In the wake of this event, she took over her brother’s job in a photo shop. She claims that her encounter with photography, particularly the pictures of Jewish customers, altered her perception of reality. According to the norms of her native village, men alone held cameras and that only at weddings, most definitely not as a means of self-expression.10

Ziyan made many choices in her life that could be aptly described by the oxymoron in the title of this article: hiding in the light. She chose to get a degree, not marry, learn to drive, work, and be independent, all while living at home with her family, respecting the traditions and customs of her community and not rebelling for the sake of rebellion. “Independence doesn’t necessarily mean waging war on the family or rebelling boisterously and openly,” she says (Abu Shaqra 2018).

The same duality can be found in the choice of medium, compared with her unique use of it. Although the very essence of photography is light, exposure, openness, and memorialization, the visual language and codes Ziyan developed signify elusiveness. Her photographs strike a precarious balance between the overt and the covert, light and darkness, the rational and the irrational, patriarchalism and feminism.

Unbeknownst to her parents, Ziyan began to study art and photography at Haifa University in 2007. She graduated in 2010 with a BA cum laude and won the Friends of the University of Haifa award for the highest achievements in a final project. In 2012, she received an MFA. The final project for her BA degree (Figure 2), like many of her later works, including the 2017 series, dealt with the Druze woman. They are marked by a fundamental contrast between black and white, representing respect for tradition and the past on the one hand, and the fear of rebelling against them on the other hand (ibid.).

Figure 2.

Amira Ziyan, Untitled, 2010. Photograph, 50 × 70 cm., from final BA project, by courtesy of the artist.

4. Hiding in the Light

The most pronounced contradiction in Ziyan’s photographs in this series is associated with her use of light. Whereas photography is inherently based on exposure to light, here the light seems to interfere with the central event, or at least with its most crucial elements.

Recurring contrast between black and white, darkness and light, conjures a wealth of archetypes relating to truth and lies, exposure and concealment, and implicit eroticism. The complexity of the representation belies simplistic Western differentiation between good (light) and evil (darkness), suggesting a multilayered reality of the external vs. the internal world. The external world is represented by the mundane activities depicted in most of the pictures, which are portrayed in the light. Like Ziyan herself, these encroach on an infinite manifold consciousness of present/absent female figures performing them, hiding in the dark (Ziyan 2019).

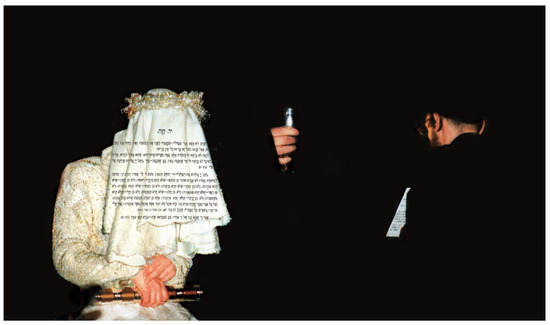

Visual codes based on a system of contradictions between good and evil, truth and falsehood, seduction and rejection, and so on, through the dichotomies of light and darkness, black and white, as well as the erasure of identity through concealment, are not foreign to Israeli female artists dealing with the status of women raised or living in traditional, patriarchal, and particularly religious communities. An example of this can be found in the works of the repentant artist Nechama Golan, undoubtably one of the central pioneers of religious women’s art in Israel (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Nechama Golan, Midrash Hava, 1999. Processed photograph, by courtesy of the artist.

This montage, which consists of a series of photographs taken by Golan during Hasidic weddings, is a stylized reenactment of a real daily event. Here too, the darkness identified with femininity is contrasted with light, symbolized by the candle held by a man’s hand. The black contrasted with white; most importantly, the female’s identity is concealed. In this case, the bride’s face is covered with a traditional veil, but one on which text is printed. The text on the veil is the first page from the chapter on Eve in Hayim Nahman Bialik and Yehoshua Hana Rawnitzki’s Sefer HaAggadah (The Book of Legends), a classic modern compilation of Jewish lore.11 The page depicted contains several dicta from Midrash “Genesis Rabbah”, compiled around the third century CE. The passages cited here place blame on the woman regarding the expulsion from heaven/Eden. This concept is emphasized in the last dicta on the veil: “Rabbi Hanina the son of Rabbi Idi said: Since Eve was created, Satan was created with her” (Genesis Rabbah 17).

The photographs of Ziyan’s series convey a synergy of similar contrasts on various strata, from the visual language to the content. The aesthetic is nearly identical: a solid black background from which hands or other parts of the body “burst” into the light. In some, only an object, such as a dress, attests to the female presence, and in all of them individuals cannot be identified. Yet, in contrast to this anonymity, Ziyan chooses the name of the woman portrayed as the title. Thus, while she evokes a sense of generalization and alienation, as some unseen woman is performing a routine activity, she also creates an almost personal relationship between the viewer and the figure: it is Samira cooking (Figure 4), Katherine exercising (Figures 6 and 7) or Nada cleaning (Figure 8). Moreover, the names add another level of meaning to the photographs, positioning the activities, if not in a specific time or place, at least in a certain cultural context.

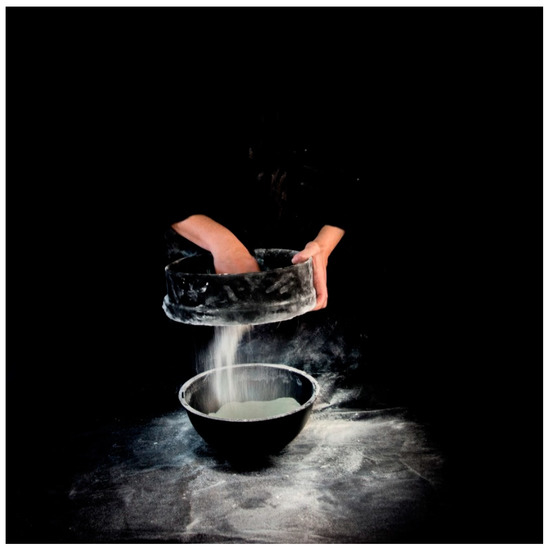

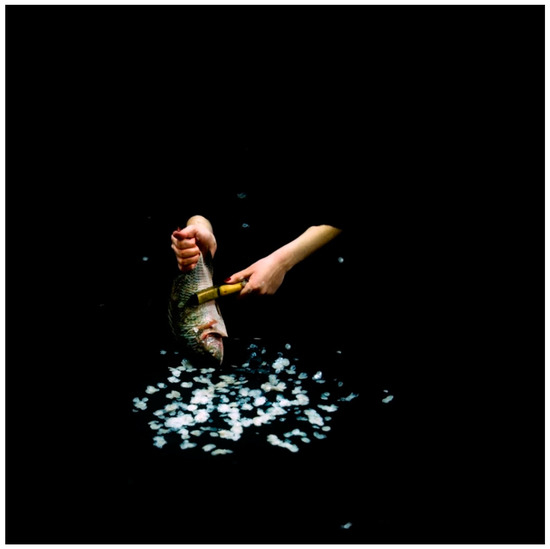

The works in the series can be divided into three general categories: cooking, exercising, and cleaning. As we will see below, despite the visual similarity between them, each category has its own distinct significance expressed in the details.

For the first category (Figure 4 and Figure 5), cooking is portrayed as a primary activity for women, virtually defining their identity. Accordingly, the raw ingredients and cooking implements take center stage in the photographs. Indeed, in Samira (Figure 4) and Heba (Figure 5), these objects are the real heroes of the picture, partially hiding the woman’s hand. They are lit by a bright, almost silvery, light, in sharp contrast to the black background. The viewer’s eye is drawn to the lower region of the scene, where the product of the activity is seen: the flour sifted by Samira, the fish scales cleaned by Heba. As in all works in the series, the contrast between the total anonymity and darkness hiding the figure and the prosaic nature of the activity implies two separate states: routine everyday life and the inner world of the present–absent figures, conveying a sense of ritual and spirituality that accompany the mundane act of cooking.

Figure 4.

Amira Ziyan, Samira, 2017. Photograph mounted on Dibond, 100 × 100 cm, by courtesy of the artist.

Figure 5.

Amira Ziyan, Heba, 2017. Photograph mounted on Dibond, 100 × 100 cm, by courtesy of the artist.

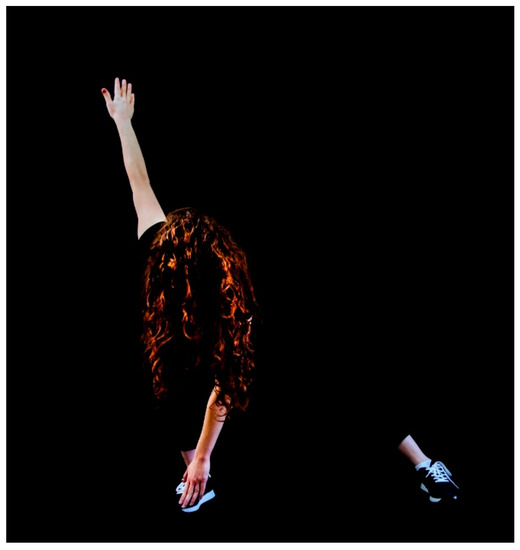

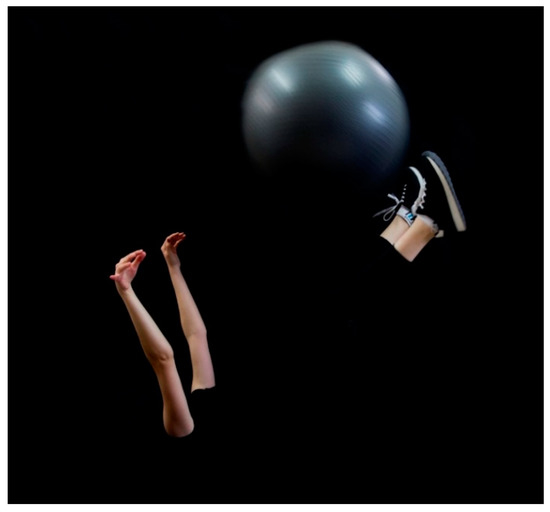

The photographs in the second category (Figure 6 and Figure 7), which depict Ziyan’s friend Katherine exercising, are the only ones in which we see the figure’s head. Nevertheless, only her hair is visible, not her face, so that despite the name and relationship between the two women, she cannot be identified with any certainty. Unlike the other pictures in the series, here the subject is the movement of the female body. Nevertheless, the basic synthesis of contrasts is preserved: the movement itself is not depicted but merely hinted at by its “edges”, the hands and ankles. Katherine’s head and the ball serve as additional anchors in the composition, enabling the viewer to identify the action and the position of the body. Yet, for the subject of the photograph, Katherine, her thoughts, feelings, and inner world remain concealed, hidden in the light and fully existing only in the viewer’s imagination.

Figure 6.

Amira Ziyan, Katherine, 2017. Photograph mounted on Dibond, 100 × 100 cm, by courtesy of the artist.

Figure 7.

Amira Ziyan, Katherine, 2017. Photograph mounted on Dibond, 100 × 100 cm, by courtesy of the artist.

Cleaning, the subject of the third category (Figure 8, Figure 9 and Figure 10), has special social significance for the Druze community, as Ziyan reveals: “You especially have to keep the body clean … That’s very important for us,” she says. “If a woman is dirty, she can’t get married again … Women who are unclean are punished. Culturally speaking, dirty isn’t only physical. Talking and exposing yourself too … A woman must hide herself”.12

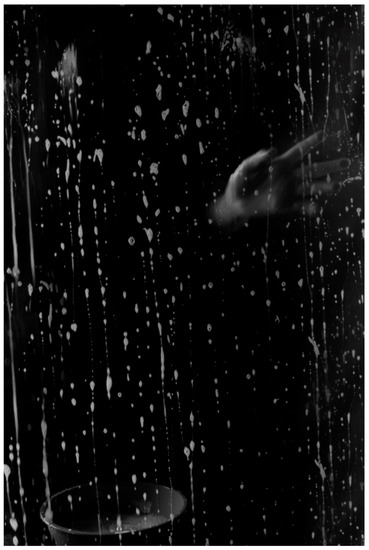

Figure 8.

Amira Ziyan, Nada, 2017. Photograph mounted on Dibond, 70 × 50 cm, by courtesy of the artist.

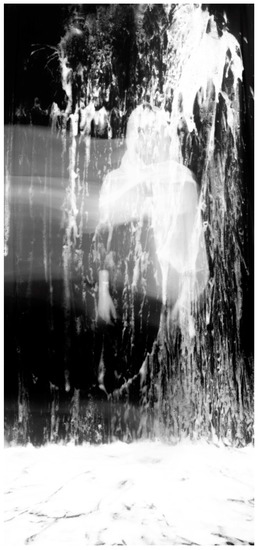

Figure 9.

Amira Ziyan, Untitled, 2017. Photograph mounted on Dibond, 180 × 90 cm, by courtesy of the artist.

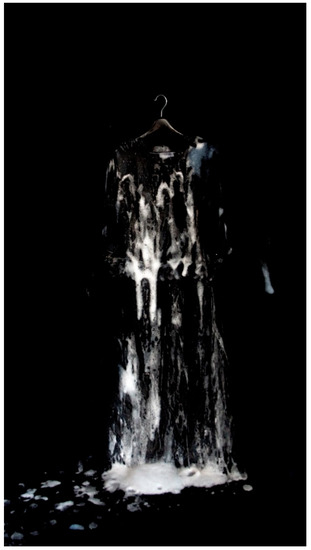

Figure 10.

Amira Ziyan, Dress of Suds, 2017. Photograph mounted on Dibond, 180 × 110 cm, by courtesy of the artist.

Abu Shaqra emphasizes the importance of purity for Ziyan and its connection to respect for woman in the Druze community.13 Gilad Ophir, the curator of the exhibition “Crystal Palace”, also relates to this issue, claiming that cleanliness is both personal and social, reflecting concern for the home, children, and the woman’s body. Any contact between the woman and people outside the family, especially men, tarnishes her social and familial status (Ophir 2018, p. 28).

Ziyan treats the act of cleaning powerfully in her photographs of Druze women. Rather than providing visual indications of the model’s gender and inner world, the images focus on the act itself and its consequences: streaks of soap and water. In Nada (Figure 8), the artist retains the model’s female name, but Nada’s body is only hinted at by the movement of a hand. The camera’s slow shutter speed blurs the contours, nearly concealing the figure. Instead, the focus is on soapy water dripping down a window and the bucket in the lower section.

In Untitled (Figure 9), Ziyan goes a step further, identifying the act of cleaning with the woman herself and thereby turning her into a ghost-like figure. The visual similarity between the woman and the dripping water is so great that the viewer might mistakenly imagine that the figure is just more dirt on the window, whether a piece of fabric or a soap stain.

The woman’s total identification with the act of cleaning can be seen in Dress of Suds (Figure 10). Here the female figure is entirely absent, replaced by Ziyan’s recurring image of femininity: a dress on a hanger. If, in Red Dress, the woman “hangs” on the man and the patriarchal tradition, in Dress of Suds there is no visible representation of the male, though his modes of power and authority remain an intangible cultural presence: a dress soaked in soapy water. This adds a further spiritual and ethical level of meaning to the physical cleanliness and purity demanded of women in Druze society.

In addition to their unusual iconography and unique visual choices in depicting female figures, the works dealing with cleaning stand out also for their elongated format. Most of the pictures in the series are square, creating a sense of balance and calm that attests to a degree of acceptance of their situation on the part of the women. The vertical format of the cleaning photographs, however, upsets the delicate balance of the composition, conveying a feeling of unease on the one hand, and an aura of reverence and holiness on the other hand. They are visual representations of the unique significance of cleanliness for the status of women in Druze society and in Ziyan’s personal life. Furthermore, the language and visual codes that characterize these photographs display three main features: abstraction, deconstruction, and a reconstruction that might be termed dodecaphonic.14

Similar visual codes can be found in the work of another artist, Hayam Mustafa. As with Ziyan, Musafa’s work is located at the intersection of modern Israeli society and conservative Druze communities. And like Ziyan’s “cleaning women”, often women in her works resemble abstract, unidentified spots, where the hidden outweighs the visible (Berkowitz 2018). In these examples (Figure 11 and Figure 12), women appear with their backs to the viewer, revealing a resemblance in visual language to Ziyan’s abstract female spots. In both cases, these visual codes convey synergy between contradictory existential questions such as progress versus tradition and the subjugation of personal identity in favor of the communal-versus-individual self-expression. However, each of the artists injects an entirely different sense of association into the discussion. Thus, similar visual codes have other contexts, and their interpretations differ accordingly.

Figure 11.

Hayam Mustafa, Untitled, 2017. Acrylic on canvas, 100 × 120 cm, by courtesy of the artist.

Figure 12.

Hayam Mustafa, Untitled, 2012. Acrylic on canvas, 120 × 100 cm, by courtesy of the artist.

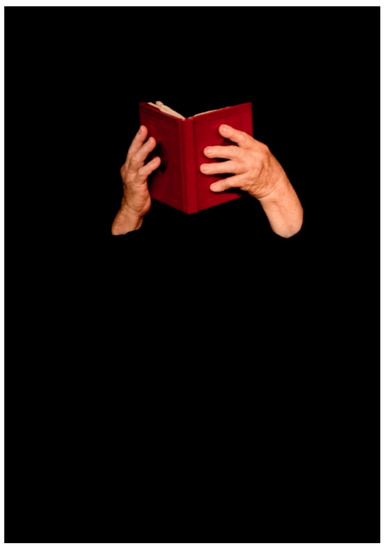

The work Jameela (Figure 13), depicting Ziyan’s mother reading the sacred esoteric canon Rasa’il al-Hikmah (The Epistles of Wisdom),15 is distinct in its interplay of textual and visual concealment. The Druze secret text arouses a sense of awe and mystery in the artist and occasions the same basic contradiction between exposure and concealment. “My religion is secret,” she says, “since I’m not a religious woman, I don’t know what is in it and I’m not even allowed to touch the book. I used to hear a lot of things about women: the book says this, and the book says that … I don’t know if it’s true or if it’s just made up, because I never saw it with my own eyes. But that is what I was raised on, that is what I was taught”.16

Figure 13.

Amira Ziyan, Jameela, 2017. Photograph mounted on Dibond, 70 × 50 cm, by courtesy of the artist.

Unlike other works in the series which portray routine or physical activities, this one relates to an act of worship. Moreover, the fact that she is reading the secret text indicates that Ziyan’s mother belongs to the al-‘Uqqāl, the “knowledgeable initiates”.17

Representing the mother’s religious status has broader cultural meaning, referencing the status of women in Druze society. The Druze faith is one of the few monotheistic religions in which a woman can serve as a spiritual leader or hold a religious position. Furthermore, it is the only such belief system that favors women over men discriminatorily. A man wishing to move from the status of Junhāl (unlearned) to ‘Uqqāl must get permission from al-‘Uqqāl, whereas a woman, considered pure from birth, is automatically granted this status when she comes of age, unless she is expelled from the group.18

Once again, although the woman’s name appears in the title, neither her face nor her body can be seen. Only her hands holding the book are lit up. Here too, Ziyan hides the figure, representing it solely by means of an object (the book), even though her religious status could be indicated by visual elements of her appearance.19 As with the rest of the photographs, concealing the figure adds a mystical level of meaning to the picture.

The depiction of the hands is also unusual. Whereas most of the female hands in the series sport red nail polish and tend towards the delicate, in contrast to the strenuous activity they are performing, here they are pudgy, at rest, and lacking in any sign of femininity. They bear witness to her mother’s age and long years of hard work, while unexpectedly presented in a mystical, spiritual context. This too attests to her religious status, which prohibits any indication of frivolousness or immodesty.20

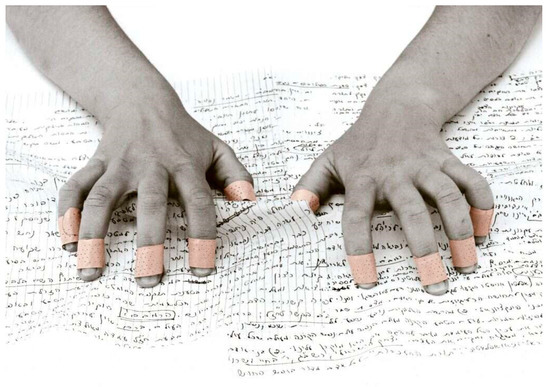

The contrast between the appearance of the woman’s hands and her spirituality, especially the fact that the cross between palms and text are the main visual code of this work, is reminiscent of yet another work by Nechama Golan, “Reality Hurts” (Figure 14). Here, two female (but, again, lacking in any sign of femininity) palms hold pages of handwritten text with a grip that seems both desperate and lustful. All the fingers are covered with bandages, which also convey a duality between protection against injury and healing. The artist wrote this text while studying Jewish philosophy as part of her repentance process. It symbolizes, on the one hand, the power she draws from her studies and, on the other hand, the complexities inherent in the religious prohibition on women’s studies.

Figure 14.

Nechama Golan, Reality Hurts, 1999. Processed photograph, 50 × 60 cm, by courtesy of the artist.

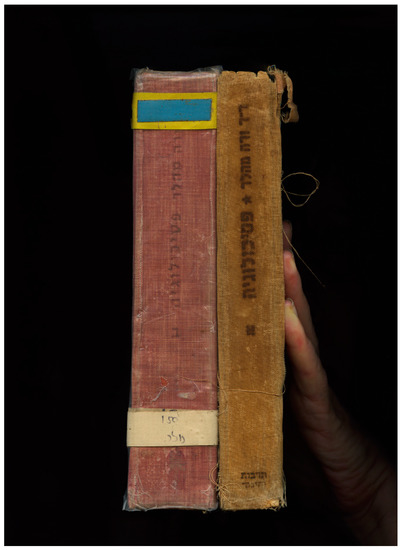

Note that the examples presented above were created by female artists who are members of patriarchal traditional societies. In the last two (Figure 13 and Figure 14), the content of the texts presented corresponds to values of these traditions. However, as mentioned earlier, the use of visual codes related to erasure or prominence of female figures and their identity through objects, body parts, color, and light is common in feminist art that addresses issues of women’s identity and status. Michal Heiman’s “Book Spines” series from 2008 (Figure 15 and Figure 16) is a pertinent example that corresponds with Ziyan’s visual codes and ideas.

Figure 15.

Michal Heiman, Book Spines, MHI (Magnetic Heiman Imaging), Psychology (By Vera Mahler, Vols. 1–2), Tel-Aviv (1961–1965), 2008. Scennogram, 100 × 72 cm, by courtesy of the artist.

Figure 16.

Michal Heiman, Book Spines, MHI (Magnetic Heiman Imaging), Encyclopedia of Sex Knowledge (By Dr. Costler and Dr. Willy, Vols. 1–2, Jerusalem, 1964), 2008. Scennogram, 100 × 72 cm, by courtesy of the artist.

In this series, the artist utilizes a technique she calls “Scennogram” (a term Heiman coined with linguistic editor Dafna Raz). A scanner is controlled by pressure and movement of both the human body and machine as an artistic medium. Each of the works of the series depicts book spines that include the title, author, publisher’s logo, volume number, etc. In Figure 15 and Figure 16, as in the entire series, Heiman presents non-fiction books from her personal library, whose themes are central to her life as well as to feminist discourse, including theories about sexuality and sex crimes, psychological theories, suicides, and poetry by women. According to her, the books are “One large readymade … like a resonance box: they connect with the vanishing point of waking up to them in the morning” (Omer 2008, p. 183).

Parts of the artist’s body are attached to the books: palms (Figure 15) or palms and a face (Figure 16). Here, too, the hidden outweighs the visible as human organs derive from darkness, created by a black cloth with which Heiman covers the scanner, much like how Ziyan covers parts of her figures. Human organs seem to emerge from a dusky twilight–both present and absent—covered by the books, which frames, like Ziyan’s everyday objects, the discourse around the mysterious figures.

Finally, akin to Ziyan’s photographs, Heiman’s Scennograms allude to the presence of a male figure, or more precisely, a father figure. In both cases, the visual codes that imply this indicate duality between steadiness on the one hand, and demarcation on the other hand. Heiman makes repeated use of the first two volumes of each series of books which are marked by the first two Hebrew letters: Alef-Beth. Put together, these letters form the word “father” (Figure 15 and Figure 16). At times, the artist’s face is crushed between the two books (and letters) but simultaneously supported by it (Figure 16).

5. Conclusions and Afterword

Visual codes are accepted conventions, readily understood by members of the culture in which they appear. The unique quality of a creator lies in the way he or she charges these codes with personal, at times eccentric or cultural interpretations, that portray a rich worldview and give new meanings to established conventions. The visual language Ziyan developed is based on a synergy of contrasts between accepted Western visual codes, which she absorbed during her studies and integration into Israeli culture and art field, and codes of the traditional patriarchal religious culture which she grew up immersed in. These visual codes express the halved inner world of a creator hanging between two worlds, not fully belonging to any of them. As we have seen in the work of other female artists who had similar life experiences, the same codes are used to express senses of “Otherness” and alienation. Additionally, feminist artists dealing with similar messages use similar visual codes despite differing life experiences. Ziyan’s original manipulation of these visual codes molds ordinary, simple moments with existential struggles, resulting in a unique, coherent, conceptual system of substantial contradictions that shake the viewer’s world.

In No Caption Needed (Hariman and Lucaites 2007), Robert Hariman and John Lucaites define what they term the “iconic photograph”, functioning like a religious icon, conveying a range of meanings and conjuring emotional responses in viewers who are members of the social culture it references. According to the authors, an iconic photograph, or one capable of becoming an icon, can be identified by aesthetic values based on “visual commonplaces” (what I have termed visual codes), and therefore “are easily recognized by many people of varied backgrounds. They are Lucite’s objects of veneration and other complex emotional responses. They are reproduced widely and placed prominently in both public and private settings, and they are used to orient the individual within a context of collective identity, obligation, and power … Objects of contemplation bearing the aura of history, or humanity, or possibility, they are sacred images for a secular society” (Hariman and Lucaites 2007, pp. 1–2).

Ziyan’s photographs undoubtedly meet these criteria, granting them the potential to become iconic. They are heavily charged with visual codes that render them easily recognizable, arouse strong emotional responses in a wide variety of viewers, members of either modern Israeli, Druze, or other traditional–modern societies. The contradictions represented both in their language and their style transcend the artist’s personal meaning and relevance, interacting on a cultural level with a diverse audience. Although the figures and subjects represent “the other” of a specific culture, place, and time, they trigger reflexive and critical contemplation of complex realities. Synthesizing the cross-cultural influences that guides her life, Ziyan develops a mysterious synergetic language that is simultaneously specific enough to trigger the viewer and vague enough to allow adaptation to one’s own cultural dichotomies.

The photographic series discussed here represents reflections on an inner world composed of concentric circles spreading out from her personal experience in the society in which she was raised. These encompass the status of women and the meaning of femininity in Middle Eastern culture, in the Druze community, and its encounter with Western culture in general.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Acknowledgments

My sincere thanks to Ilia Rodov and Leor Jacobi for helpful comments.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

Notes

| 1 | The term “visual code” is employed here as a tool for critical reading of the visual text. It relates to a system of cultural conventions expressed in the choice of representations, from basic elements of language to choices of iconography. The codes arouse a range of feelings and associations in the viewer, unconsciously and often automatically, that enables interpretation of an image in the context of culture, the spirit of the times, and personal experience. The concept of “visual code”, as used here, relies on post-structuralist criticism associated with thinkers such as Foucault, Deleuze, Derrida, Lacan and mainly Roland Barthes, which elevates connotation and negates denotation as a central tool for conveying meaning. In “The Photographic Message” (Barthes 1977), Barthes defined the “photographic paradox” as the necessary and simultaneous existence of both denotative and connotative messages in photographs and visual representations in general. In photography, this paradox is inherent in the very essence of the medium—how the camera accurately copies reality. Barthes defines this paradox as follows: while naturally and immediately, the photograph is perceived by the viewer as an “analogous” accurate transfer of reality, it is never actually like that. In the process of photography, a transformation of reality always occurs—the freezing of a moment, its reduction and flattening. Barthes claims that two opposing forces work simultaneously in visual texts to create its message: the power to represent reality, which produces a denotative message, and the power to shape reality, which produces a connotative message. The denotative message is the result of the viewer’s ability to identify the images and relate them to reality. The connotative message embodies within it the prevailing cultural meanings, cultural symbols belonging to the spirit of time or place, and universal symbols. Barthes claims that although people feel that their interpretations of the photograph originate from their personal feelings, it is actually based on a system of cultural symbols. This is the claim embodied in the concept of visual code—viewers feel a sensation whose origin they do not recognize. This feeling is motivated by the intelligent use that the creator makes of those cultural conventions and symbols. Analysis of the visual code begins, therefore, by defining that personal feeling, and only then in looking for cultural anchors for it. |

| 2 | The term “Otherness” refers to the quality or fact of being different. This concept is important in the postmodern discourse and many thinkers have discussed it. Foucault believes that every society undergoes a process in which the dominant culture pushes the other, the foreign, and the peripheral out of its spheres of influence. This is accomplished by defining the discourse of that “other” as irrelevant because it is biased and false (Foucault 1980). Similarly, Roland Barthes refers to it as a concept that most of all arouses the aversion of “common sense”, because one of the recurring characteristics of every petit bourgeois mythology is this inability to simulate the “other” (Barthes [1970] 1975). Emmanuel Levinas also refers to the “ethics of the Other” and considers responsibility towards the “Other” a necessary condition for the formation of morality. The “Other”, according to Levinas, refers to anything that is formulated in a way that I do not intuitively accept or understand. The very recognition of the existence of such a system of concepts establishes the human subject, on the one hand, and places him in a moral context on the other hand. According to Levinas, the term responsibility must be perceived as responsibility towards the other, towards what is not mine or does not even concern me; or rather towards what does concern me, that stands in front of me (Coe 2018, pp. 14–18). Israeli Culture researcher David Gurevich defines the term “Other” as follows: “The Other is everything that is not ‘I’, but is also not the opposite of that ‘I’. The ‘Other’ does not fit into the philosophical, psychological, aesthetic scheme that I am familiar with. The ‘Other’ is anyone whose existence I do not recognize as a subject, his right to be represented, his right to speak. This is an expression of the differences that disintegrate the rational pattern of the self: the ‘Other’ is the gap between the sayer and what is said by him. Postmodern ethics bases its self-identification on the responsibility to ‘Others’ (Gurevich 1997, p. 377). |

| 3 | The existence of these inherent contradictions has been addressed in a variety of studies that sought to define a unique Israeli identity. Shmuel Noah Eisenstadt likened it to the figure of the “pioneer”. Although originally perceived as essentially altruistic, the pioneers were, in fact, an elite group with moral and political demands that regarded membership in its ranks as a basis for special rights to which others were not entitled (Shmuel Eisenstadt 1967). Following this line of thought, Amnon Rubinstein explained that the figure of the “sabra” (a native-born Israeli), the direct descendent of the “pioneer”, emerged from the ambivalent and conflictual attitude of Israeli society to newcomers (Amnon Rubinstein 1984). Michael Feige and Luis Roniger describe the contradiction between the demand for citizens to sacrifice themselves for the country and what they call the “freier (sucker) culture”, or the unwillingness to be a “freier” that is built into the very establishment of Israel (Roniger and Feige 1992). Mosheh Tsukerman claims that there is no point in attempting to define any sort of “Israeli identity” so long as the contradictory foundations of the Israeli experience have not been explained in depth (Tsukerman 2001). |

| 4 | Using visual codes associated with erasure or prominence of female identity is not limited to creators of patriarchal or traditional cultures but is also employed by many feminist female artists. An example will be addressed towards the end of the article. |

| 5 | Synergy is the interaction or cooperation of two or more substances to produce a combined effect greater than the sum of their separate effects. The German art and design researcher Michael Erlhoff defines the term “Synergy” as “the process whereby two or more people or organizations with complementary skills, resources and knowledge, are able to achieve more through collaboration than the simple addition of their efforts working individually would have suggested” (Erlhoff and Marshall 2008). The use of this term expresses the concept that the system of contrasts embedded in Ziyan’s photographs functions as a sort of cooperation that results in a characteristic visual code, greater than the sum of its components. |

| 6 | The weave of contradictions typical to Israeli society, in which various groups of “Others” integrate into it, and how these contradictions are expressed in the art of these groups, is discussed by Tal Dekel. In her book Women and Migration, Art and Gender in a Transnational Age, she describes this contradiction: “In Israel there are different types of Others. Everyone can choose who their Other is. This basic state of the Jewish nation–state embodies a deep paradox. On the one hand, the country has been busy since its inception in accepting foreigners, indeed Jewish foreigners, those who are considered part of the ethnic collective, but complete strangers to the receiving collective. On the other hand, precisely foreigners and immigrants who are members of a different religion, who are defined as having no chance of becoming an organic part of the social and civil fabric of the State of Israel, become a central and vital part of life in it”. Admittedly, Dekel is dealing with immigrants, but her words can be also applied for minority groups such as the Druze, whose role in the military and civil service is perceived as important and central, even though this does not directly express their social status and their ability to fully integrate into society (Dekel 2013, p. 197). |

| 7 | The details and interpretations of this work are based on an interview with the artist, 19 February 2020, N.T. Further evidence appears in various publications over the years (for example Weinberg 2018). The meanings of these central representations are not the focal point of the discussion but rather the system of contrasts, for its connotative meanings, that produces a typical visual code with which the artist shapes her visual language. |

| 8 | Her father’s authoritarian behavior and her relationship with him are recurring themes in Ziyan’s work. However, her situation was not unusual in Druze society. While the mother is the dominant parent in raising children, the father has the final word, particularly in respect to his daughters’ marriages (Halabi 2002). |

| 9 | “He wanted me, but I couldn’t love him as a husband. He felt like my brother. It would be a pity for me and a pity for him to live with someone who doesn’t love him” (Kapach 2018). |

| 10 | “Working in the studio changed my life. I saw the photographs of Jewish customers. I saw they represented a different world than the one I knew. And this world spoke to me. I went back to college and registered for an introductory course in photography, but it didn’t satisfy me. I wanted to get a degree in art from Haifa University, but I knew my parents wouldn’t agree because it was a long way from the village, and I’d already studied a different subject. They complained that I was capricious and raised all sorts of arguments, like ‘if you study art, you won’t get married’, and ‘what will you get from it?’ They didn’t understand what it was I wanted. In Yarka, they weren’t exposed to art, and only men were allowed to hold cameras at weddings. But I stood my ground”(Kapach 2018). |

| 11 | Tel Aviv: Dvir, 1947 (Hebrew), p. 15a. Thanks to Paul Mandel for assistance in locating the edition. |

| 12 | From an interview with the artist, 19 February 2020, N.T. |

| 13 | “It is still important to her to prove that studying art outside the home did not detract from her loyalty to her father’s principles and way of life in respect to purity and honor in the family and extended family. Fear and purity are central themes in her life that have been with her since childhood and will apparently remain with her forever” (Abu Shaqra 2018, p. 21). |

| 14 | Dodecaphony, or the twelve-tone technique, was developed by the modernist German composer Arnold Schoenberg (1874–1951) in the wake of the atonal system. It relates to a variety of musical genres that do not maintain traditional tonal relationships. Instead, the composer organizes the music around a set of individual tones that lack the accepted internal hierarchy. The random series of tones devised by the composer serve as the central motif around which the composition is constructed (see Grout 1973). I use the term here to describe a series of connections of a personal and associative nature that recur in different forms in the cleaning pictures, analogous to the tones in dodecaphonic music. |

| 15 | Rasa’il al-Hikmah, transcribed exclusively by hand, contains 111 epistles organized into six volumes. They were written by Druze sages over a long period of time known as the Era of Revelation, which ended in 1043. The epistles contain cryptic texts regarded as secrets that only a few are entitled to decipher (Avivi 2000). |

| 16 | Interview with the artist, 19 February 2020, N.T. |

| 17 | In terms of religion, the Druze are divided into three groups: al-Ajawid, religious scholars, and the community’s spiritual leaders and authorities, a status achieved only by those who devote their lives to religious study; al-‘Uqqāl, pious individuals who are familiar with the secrets of the religion and are allowed to read the sacred texts, and who regularly attend prayers and meetings at the khalwat, the house of prayer; and al-Junhāl, the “ignorant”, primarily youngsters, who are not privy to the religious secrets and are not entitled to pray or read the canonical text (Halabi 2002, pp. 9–10). |

| 18 | Sheik Ahmed Kheer, a member of the Druze Spiritual Authority in Israel, stated that the distinguished status of the Druze woman and her equality with her husband in the home derives directly from the high status she is granted in the Druze religion. Nevertheless, as the Druze have typically been a persecuted minority, limitations are placed on the women. Throughout the generations, spiritual leaders have not allowed women to venture outside the community, not even to study or work, and certainly not to marry. Values demanded of the woman are purity, modesty, and humility (Fallah 2000); (Halabi 2002, pp. 34–35). |

| 19 | al-‘Uqqāl are obliged to wear traditional garb, particularly the laffa, a red fez with a white scarf wrapped around it. They also shave their heads as a sign of modesty (Fallah 2000, p. 109). |

| 20 | al-‘Uqqāl must conduct themselves with exceptional modesty and treat all human beings with kindness. They are forbidden from drinking alcohol, using profanity, or visiting any place of amusement, including restaurants, movies, or even weddings, where there is dancing and singing. They are not allowed to sing or listen to music, and therefore not allowed to listen to the radio. The most pious refrain from watching television as well. Ibid. |

References

- Abu Shaqra, Said. 2018. “From Amira to Miriam” [mi-Amir le-Miryam]. In Gilad Ophir (Curator), Amira Ziyan: Crystal Palace (Exh. Cat.). Umm el-Fahem: Umm el-Fahem Art Gallery, pp. 2–24. (In Hebrew) [Google Scholar]

- Avivi, Shimon. 2000. The Druze in Israel and Their Holy Places [ha-Druzinn be-Yisrael be-mekomotehem ha-kdoshim]. Jerusalem: Ariel. (In Hebrew) [Google Scholar]

- Barthes, Roland. 1975. S/Z. Translated by R. Miller. New York: Hill and Wang. First published 1970. [Google Scholar]

- Barthes, Roland. 1977. “The photographic message”. In Image-Music-Text. Edited and translated by Stephen Heath. New York: Hill and Wang, pp. 15–31. [Google Scholar]

- Berkowitz, Aria. 2018. Hayam Mustafa, Their Own Way (exh. cat.), Tel Aviv Artists House. Available online: https://zivakoort.com/2018/09/17/%D7%94%D7%99%D7%90%D7%9D-%D7%9E%D7%95%D7%A1%D7%98%D7%A4%D7%90-%D7%91%D7%93%D7%A8%D7%9A-%D7%A9%D7%9C%D7%94%D7%9F-%D7%AA%D7%A2%D7%A8%D7%95%D7%9B%D7%94-%D7%91%D7%99%D7%AA-%D7%94%D7%90%D7%9E%D7%A0%D7%99/ (accessed on 7 October 2022). (In Hebrew).

- Coe, Cynthia D. 2018. Levinas and the Trauma of Responsibility: The Ethical Significance of Time, 1st ed. Indiana: University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Cotton, Charlotte. 2014. The Photograph as Contemporary Art. New York: Thames & Hudson. [Google Scholar]

- Dekel, Tal. 2013. Women and Migration, Art and Gender in a Transnational Age. Tel Aviv: Resling. (In Hebrew) [Google Scholar]

- Eisenstadt, Shmuel Noah. 1967. Israeli Society. London: Weidenfeld and Nicolson. [Google Scholar]

- Erlhoff, Michael, and Tim Marshall, eds. 2008. Design Dictionary Perspectives on Design Terminology. Basel: Birkhäuser, p. 388. [Google Scholar]

- Fallah, Salman. 2000. The Druze in the Middle East [ha-Druzim be-mizrach ha-tichon]. Tel Aviv: Ministry of Defense press. (In Hebrew) [Google Scholar]

- Foucault, Michel. 1980. “On Popular Justice: A Discussion with Maoists”. In Power/Knowledge, Selected Interviews and Other Writings 1972–1977. Edited by Gordon C. New York: Pantheon Books, pp. 1–36. [Google Scholar]

- Grout, Donald Jay. 1973. A History of Western Music. New York: W. W. Norton & Co., pp. 481–82. [Google Scholar]

- Gurevich, David. 1997. Postmodernism Culture and Literature at the End of the 20th Century. Tel Aviv: Dvir. (In Hebrew) [Google Scholar]

- Halabi, Musbah. 2002. The Druze in Israel [ha-Druzim be-yisrael]. Tel Aviv: Melo. (In Hebrew) [Google Scholar]

- Hariman, Robert, and John Louis Lucaites. 2007. No Caption Needed: Iconic Photographs, Public Culture, and Liberal Democracy. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. [Google Scholar]

- Kapach, Einat. 2018. “Crossing the wall” [la’avor et ha-kir]. Makor Rishon. July 30. Available online: https://www.makorrishon.co.il/magazine/dyukan/66713/ (accessed on 7 October 2022). (In Hebrew).

- Levi, Abslom (Curator). 2016. On Exposed Concrete (Exh. Cat.). Cabri Gallery. Available online: http://www.cabrigallery.org.il/OnExposedConcrete_Az.aspx (accessed on 7 October 2022). (In Hebrew).

- Omer, Mordechai. 2008. To Put Painting Once Again in the Service of the Mind, Michal Heiman and Marcel Duchamp. In Michal Heiman Attacks on Linking (Exh. Cat. Curator Mordechai Omer). Edited by Michal Heiman. Tel Aviv: Tel-Aviv Museum of Art. [Google Scholar]

- Ophir, Gilad. 2018. Forbidden freedom [ha-hofesh ha-asur]. In Gilad Ophir (Curator), Amira Ziyan: Crystal Palace (Exh. Cat. Curator Gilad Ophir). Umm el-Fahem: Umm el-Fahem Art Gallery, pp. 25–31. (In Hebrew) [Google Scholar]

- Roniger, Luis, and Michael Feige. 1992. “From pioneer to freier: The changing models of generalized exchange in Israel”. European Journal of Sociology 33: 280–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rubinstein, Amnon. 1984. The Zionist Dream Revisited. New York: Schocken Books. [Google Scholar]

- Tsukerman, Moshe. 2001. The Making of Israeliism: Myths and Ideologies in a Conflictual Society [kharushet ha-israeliut: Mitosim ve-ideologia be-khevra mesukseket]. Tel Aviv: Resling. (In Hebrew) [Google Scholar]

- Weinberg, Orin. 2018. “I gave up a private life for art” [vitarti al ha-khaim ha-pratiim bishvil ha-omanut]. Y-Net Art. February 2. Available online: https://www.ynet.co.il/articles/0,7340,L-5109585,00.html (accessed on 7 October 2022). (In Hebrew).

- Ziyan, Amira. 2014. Lecture at Artists’ Workshop, Jerusalem. February 15. Available online: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=QfdC_MMeidI (accessed on 7 October 2022). (In Hebrew).

- Ziyan, Amira. 2019. The Unseen Hypotenuse. Ramot Menashe Art Gallery (Exh. Cat.) . Available online: https://www.ramotmenashe.co.il/%d7%94%d7%99%d7%aa%d7%a8-%d7%94%d7%a0%d7%a2%d7%9c%d7%9d-%d7%90%d7%9e%d7%99%d7%a8%d7%94-%d7%96%d7%99%d7%90%d7%9f/ (accessed on 7 October 2022). (In Hebrew).

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).