Jan van Eyck’s New York Diptych: A New Reading on the Skeleton of the Great Chasm

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Overview of the Work

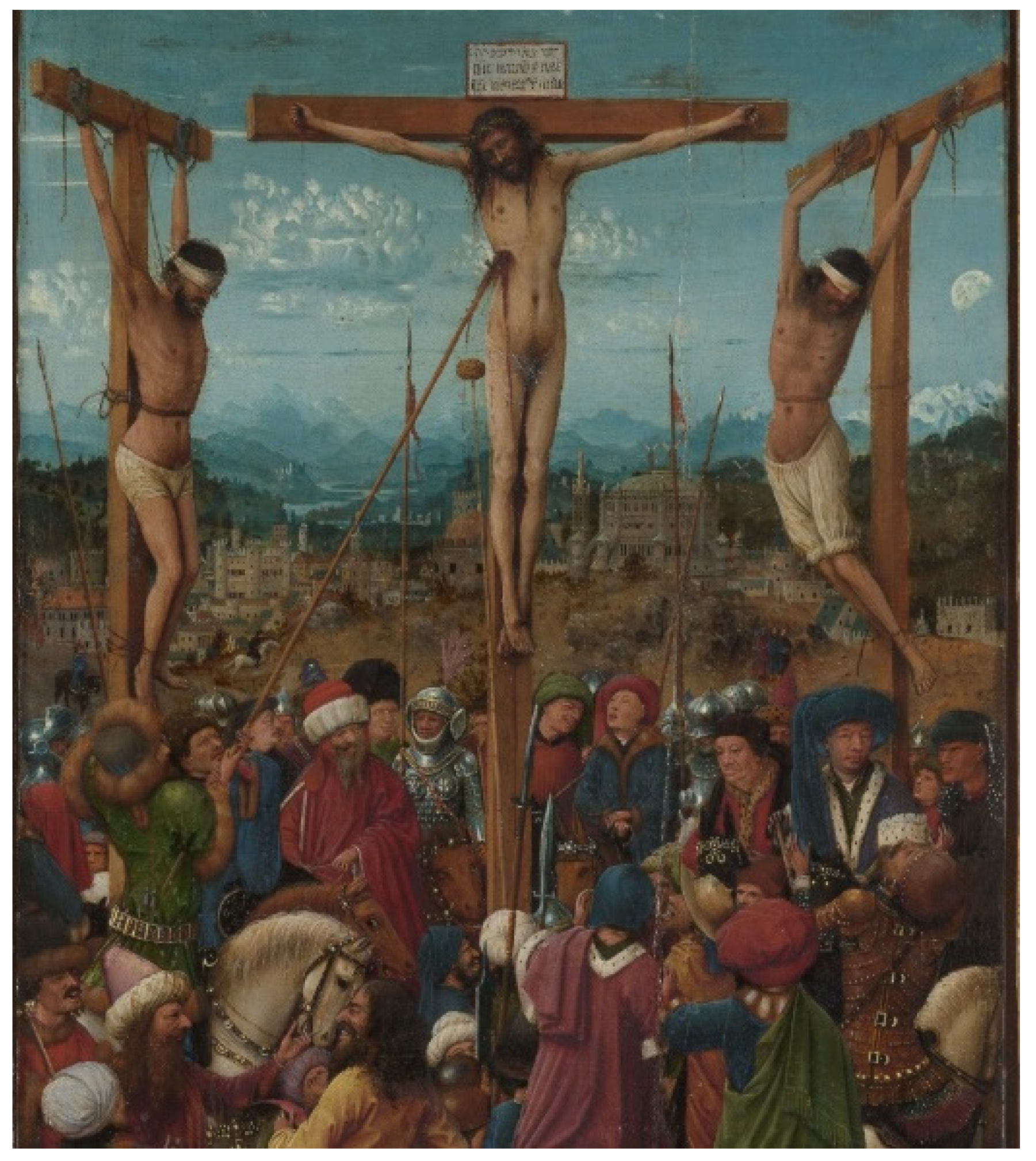

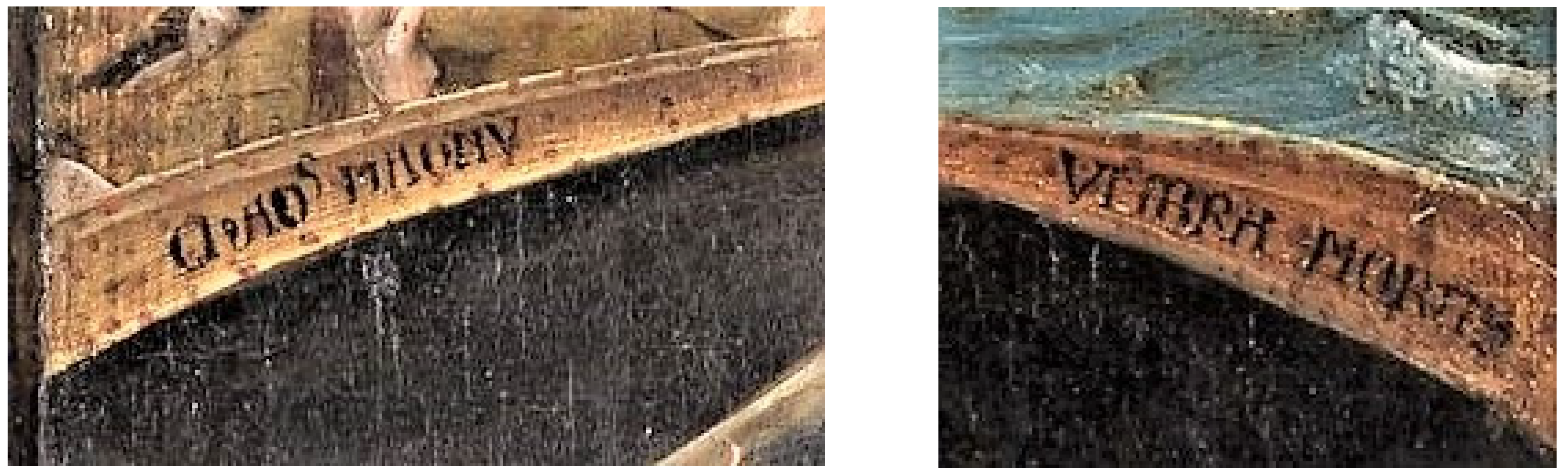

DOMINVS POSVIT I EO INIQVITATE OMNIVM NRM OBLATVS E QVIA IPE VOLVIT + NON APERVIT OS SVV SIC OVIS AD OCCASIONE DVCET + QI[?] AGNVS CORAM TONDETE SE OBMVTESCET PPT SCEL PPLI MEI PERPERCVSSI EV ET DABIT IMPIOS PRO SEPVLTVRA ET DICITES PRO MORTE SVA VSAE[?] [T]R[ADI]DT I MORTE AIAM SVA + CV SCELERATIS REPV[T]ATVS E ET IPE PCCM MVLTORV TVLIT + PRO TRANSGRESSORIBVS ORAVIT. (And the Lord hath laid on him the iniquity of us all. He was oppressed, and he was afflicted, yet he opened not his mouth: he is brought as a lamb to the slaughter, and as a sheep before her shearers is dumb, so he openeth not his mouth… For the transgression of my people was he stricken. And he made his grave with the wicked, and with the rich in his death… and he was numbered with the transgressors; and he bare the sin of many, and made intercession for the transgressors [Isaiah 53:6–9,12].)

DED MORS MORTVOS ECCE TABNACLM DEI CV HOIBVS + HITAB CV EIS IPI PP EI ERVNT + IPE DS CV EIS EIT EOR[D]S ET ABSTG OEM LA[G]A AB OCLIS SCOR + MORS VLT NON EIT N[Q]LVC NQDOLOR EIT VLTRA DEDIT MARE MORTVOS SVO CONGREGABO SR EOS MALA SAGITTAS MEA OPLEBO I EIS OSVET FAME + DEVORABT EO AVE MORSV A[?] DESTES BESTIAR MITTA I EOS CV FORE THECIV SR T[?]A AQ SPECIV. (And death and hell delivered up the dead which were in them [Revelation 20:13]; Behold, the tabernacle of God is with men, and he will dwell with them, and they shall be his people, and God himself shall be with them, and be their God. And God shall wipe away all tears from their eyes; and there shall be more death, neither sorrow, nor crying, neither shall there be any more pain [Revelation 21:3,4]; And the sea gave up the dead which were in it [Revelation 20:13]; I will heap mischiefs upon them; I will spend mine arrows upon them. They shall be burnt with hunger, and devoured with burning heat, and with bitter destruction: I will also send the teeth of beasts upon them, with the poison of serpents of the dust [Deuteronomy 32:23,24].)

2.1. Original Configuration and Provenance

Dui quadretti lungho attaccati insieme con tre colonne con base e capitelli et architrave sopratutto indorato con dio Padre nella sumita et uno di detti quadri vi e la Crocefissione di Nostro Sigre in mezzo li dui ladroni co’diuerse figurine di Soltadi, e le Marie con lettere antiche intirno, nell’altro Giesu Christo appoggiatto alla Croce con diverse figure d’Angeli e sotto esso infinite figure di santi, sotto a’quali il Purgatorio co’un Angelo in mezzo e sotto l’inferno co’lettere similmente intorno di mano del detto Alberto dura (Two long squares attached with three columns with a base and capitals as well as an architrave with gilded God the Father. One of the panels shows the Crucifixion of Our Savior in the middle accompanied with two thieves, several soldiers, and the Virgin Mary. It is surrounded with ancient letters. The other panel shows Christ against the cross and various items held by angels. Below him are countless saints; below them is the purgatory with an angel in the center; and under hell we find letters similar to those mentioned above. By the hands of Albrecht Dürer.)(Jones 2014, p. 37. Translation by the current author).

2.2. Attribution and Dating

3. Motif of the Skeleton in the Last Judgment

4. Possible Source of the Inscriptions

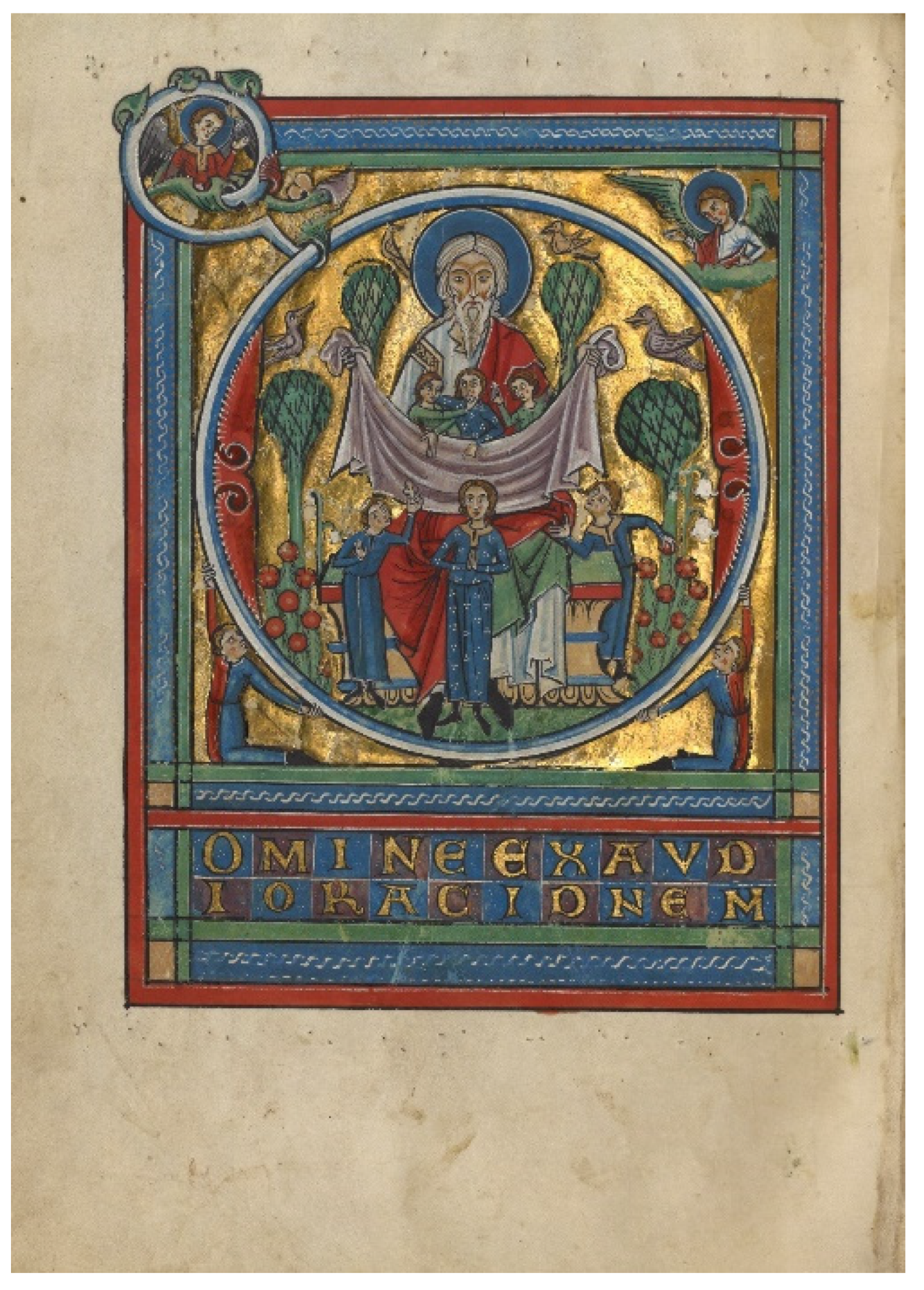

Sed iam venerat, fratres, tempus illud quod beatus Iob postulabat, iam recordandi tempus, iam venerat tempus miserendi, quando Sanctorum voces sub altare Dei beatus Ioannes audivit.… Donec enim veniret desideratus ille, qui sanguine suo deleret chirographum damnationis nostrae et, flammeum exstinguens gladium, aperiret credentibus regna caelorum, nullus omnino cuiquam Sanctorum ad ea patebat accessus; sed providerat eis Dominus in inferno ipso locum quietis et refrigerii, chaos magnum firmans inter sanctas illas animas et animas impriorum. Quamvis enim utraeque in tenebris essent, non utraeque erant in poenis; sed cruciabantur impii, iusti vero consolabantur.… Hunc ergo locum, obscurum quidem, sed quietum, sinum Abrahae Dominus vocat.… In hunc ergo locum Salvator descendens, CONTRIVIT PORTAS AEREAS ET VECTES FERREOS CONFREGIT, eductosque vinctos de domo carceris, sedentes quidem, hoc est quies centes sed in tenebris et umbra mortis, iam tunc quidem sub altare Dei collocavit (But when Blessed John heard the voices of the saints beneath the altar, the time for which blessed Job asked had already come; the time of reckoning, the time of mercy had already come.… For until he who was longed for came to cancel the decree of our damnation with his own blood and quench the fiery sword, opening the kingdom of heaven to those who believe, no way to it lay open to any of the saints. Rather, God had provided a place of rest and refuge for them below, and a great chasm was fixed between those holy souls and the souls of the wicked. For although both were in darkness, they were not both undergoing punishment; the wicked were in torment and the righteous in consultation.… And this place, dark indeed but restful, the Lord called the bosom of Abraham because, I suppose they rested in faith and expectation of the Savior.… Now the Savior, descending to this place, broke the gates of brass and shattered the bars of iron and led from their prison those who had been bound; they were indeed seated, that is, at rest, but in the shadow of death. Then he set them beneath the altar of God.)(Leclercq and Rochais 1968, pp. 354–55; Scott 2016, pp. 238–40, with some modifications of the translation by the current author).

5. Conclusions

Among the paintings including the motif of the rays through the glass is the Washington Annunciation by Jan van Eyck (ca. 1434/36) (Meiss 1945, p. 178), which is mentioned as coming from Dijon and painted for Philip the Good (Hand and Wolff 1986, p. 81). Are both the New York Diptych and Annunciation reflecting Philip’s affinity with Bernard’s writing? Further research on circulation of Bernard’s writings in and around the ducal court will provide a clue for the identity of the commissioner.Just as the brilliance of the sun fills and penetrates a glass window without damaging it, and pierces its solid form with imperceptible subtlety, neither hurting it when entering nor destroying it when emerging: thus the word of God, the splendor of the Father, entering the virgin chamber and then came forth from the closed womb.

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| 1 | A comprehensive bibliography of the New York Diptych can be found in the Metropolitan Museum of Art website: https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/436282 (accessed on 16 December 2021). |

References

- Acres, Alfred. 2000. Rogier van der Weyden’s painted texts. Artibus et Historiae 21: 75–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ainsworth, Maryan. 2016. The relationship between the Rotterdam drawing and the New York painting. In An Eyckian Crucifixion Explored: Ten Essays on a Drawing. Edited by Friso Lammertse and Albert J. Elen. Rotterdam: Museum Boijmans van Beuningen, pp. 116–33. [Google Scholar]

- Ainsworth, Maryan. 2017. Revelations regarding the Crucifixion and Last Judgment by Jan van Eyck and workshop. In Van Eyck Studies. Edited by Christina Currie, Bart Fransen, Valentine Henderiks, Dominique Vanwijnsberghe and Cyriel Stroo. Leuven: PeetersPeeters, pp. 221–32. [Google Scholar]

- Belting, Hans, and Dagmar Eichberger. 1983. Jan van Eyck als Erzähler: Frühe Tafelbilder im Umkreis der New Yorker Doppeltafel. Worms: Wernersche Verlagsgesselschaff. [Google Scholar]

- Bohde, Daniela. 2019. Mary Magdalene at the foot of the cross. Mitteilungen des Kunsthistorischen Institutes in Florenz 61: 3–43. [Google Scholar]

- Borchert, Till-Holger. 2016. Some Eyckian drawings and miniatures in the context of the drawing. In An Eyckian Crucifixion Explored: Ten Essays on a Drawing. Edited by Albert Elen and Friso Lammertse. Rotterdam: Museum Boijmans Van Beuningen, pp. 94–107. [Google Scholar]

- Bousmanne, Bernard, and Elena Savini. 2020. The Library of the Dukes of Burgundy. Turnhout: Harvey Miller Publishers. [Google Scholar]

- Brans, Jan. 1952. Isabel la Católica y el Arte Hispano-Flamenco. Madrid: Cultura Hispanica. [Google Scholar]

- Camp, An. 2016. The use of goldpoint and silverpoint in the fifteenth century. In Lammertse and Elen. Rotterdam: Boijmans Van Beuningen, pp. 44–57. [Google Scholar]

- Christiansen, Keith, and Maryan Ainsworth. 1999. From Van Eyck to Bruegel: Early Netherlandish Painting in the Metropolitan Museum of Art. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art. [Google Scholar]

- Dhanens, Elisabeth. 1973. Van Eyck-The Ghent Altarpiece. London: Allen Lane. [Google Scholar]

- Eichberger, Dagmar. 1987. Bildkonzeption und Weltdeutung im New Yorker Diptychon des Jan van Eyck. WiesbadenL: Reichert Verlag. [Google Scholar]

- Hand, John, and Martha Wolff. 1986. Early Netherlandish Painting. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Humfrey, Peter, and Martin Kemp, eds. 1990. The Altarpiece in the Renaissance. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Jones, Susan. 2014. Jan van Eyck and Spain. Boletín del Museo del Prado 32: 30–49. [Google Scholar]

- Lane, Barbara. 1984. The Altar and the Altarpiece: Sacramental Themes in Early Netherlandish Painting. New York: Harper & Row. [Google Scholar]

- Leclercq, Jean, and Henri Rochais, trans. 1968. Sancti Bernardi Opera. Rome: Cistercienses, Volume 5. [Google Scholar]

- Mecklenburg, Michael, and Thom Mertens. 2013. Introduction: The Last Judgement in medieval sermons. In The Last Judgement in Medieval Preaching. Edited by Thom Mertens, Hans-Jochen Schiewer, Maria Sherwood Smith and Michael Mecklenburg. Turnhout: Brepols Publishers, pp. ix–xxxiiii. [Google Scholar]

- Meiss, Millard. 1945. Light as form and symbol in some fifteenth-century paintings. Art Bulletin 27: 175–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panofsky, Erwin. 1953. Early Netherlandish Painting: Its Origins and Character. Cambridge: Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Passavant, Johann. 1841. Beiträge zur Kenntnis der altniederländischen Malerschulen des 15ten und 16ten Jahrhunderts. Kunstblatt 12. Available online: https://digi.ub.uni-heidelberg.de/diglit/kunstblatt22_1841/0054 (accessed on 16 December 2021).

- Paviot, Jacques. 2010. La Crucifixion et le Jugement dernier attribués à Jan van Eyck (Diptyque de New York). Zeitschrift für Kunstgeschichte 73: 145–68. [Google Scholar]

- Ridderbos, Bernhard. 2005. Objects and questions. In Early Netherlandish Paintings: Rediscovery, Reception, and Research. Edited by Bernhard Ridderbos, Anne van Buren and Henk van Veen. Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press, pp. 4–172. [Google Scholar]

- Scott, Mark, ed. 2016. Sermons for Autumn Season. Collegeville: Cistercian Publications/Liturgical Press. [Google Scholar]

- Van Buren, Anne. 1978. The canonical office in Renaissance painting, part II: More about the Rolin Madonna. Art Bulletin 60: 617–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

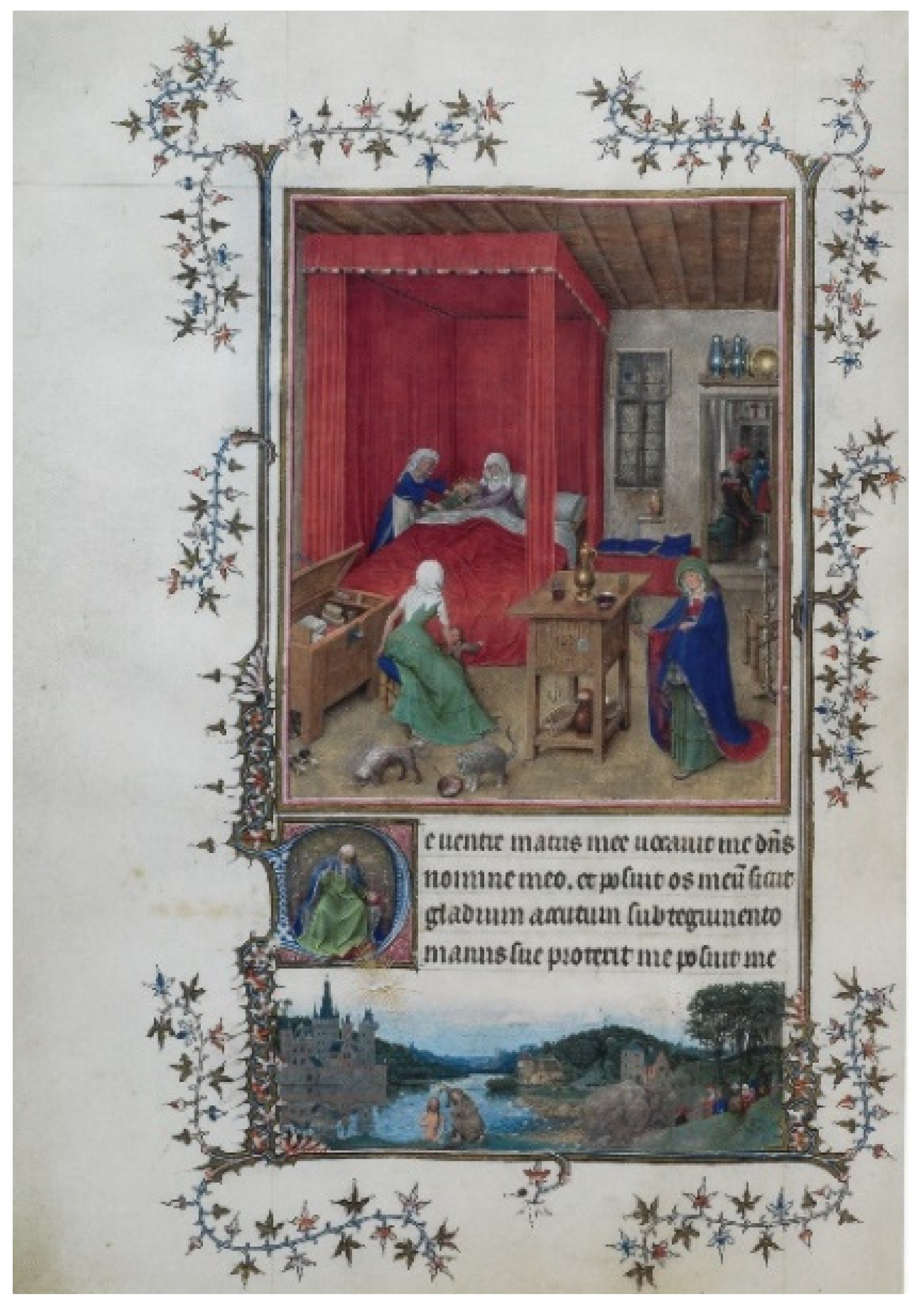

- Vanwijnsberghe, Dominique. 2020. The Eyckian miniatures in the Turin-Milan Hours. In Van Eyck: An Optical Revolution. Edited by Maximiliaan P. J. Martens, Till-Holger Borchert and Jan Dumolyn. Veurne: Hannibal, pp. 296–315. [Google Scholar]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Sugiyama, M. Jan van Eyck’s New York Diptych: A New Reading on the Skeleton of the Great Chasm. Arts 2022, 11, 4. https://doi.org/10.3390/arts11010004

Sugiyama M. Jan van Eyck’s New York Diptych: A New Reading on the Skeleton of the Great Chasm. Arts. 2022; 11(1):4. https://doi.org/10.3390/arts11010004

Chicago/Turabian StyleSugiyama, Miyako. 2022. "Jan van Eyck’s New York Diptych: A New Reading on the Skeleton of the Great Chasm" Arts 11, no. 1: 4. https://doi.org/10.3390/arts11010004

APA StyleSugiyama, M. (2022). Jan van Eyck’s New York Diptych: A New Reading on the Skeleton of the Great Chasm. Arts, 11(1), 4. https://doi.org/10.3390/arts11010004