Recto and Verso: The Pictorial Fronts and the Marbled Reverses of Two Flemish Panel Paintings

Abstract

:1. Introduction: Stone Imitation or Painted Imagery?

2. Margareta van Eyck and the Concept of prima materia

“He (Van Eyck) will have been aware of the ambiguity of confirming with it not only the completion of the painting, but also that of the woman. The sculpturability of the painting material by the artist is thus paralleled by the sculpturability of the female “materia” by the husband, “as he can”, as his word of choice adds and assures Margareta’s completed representation. The polarization of the sexes into an active male and a passive female part is not restricted to the biological component, but finds its correspondence in the artistic ‘act of procreation’”.18

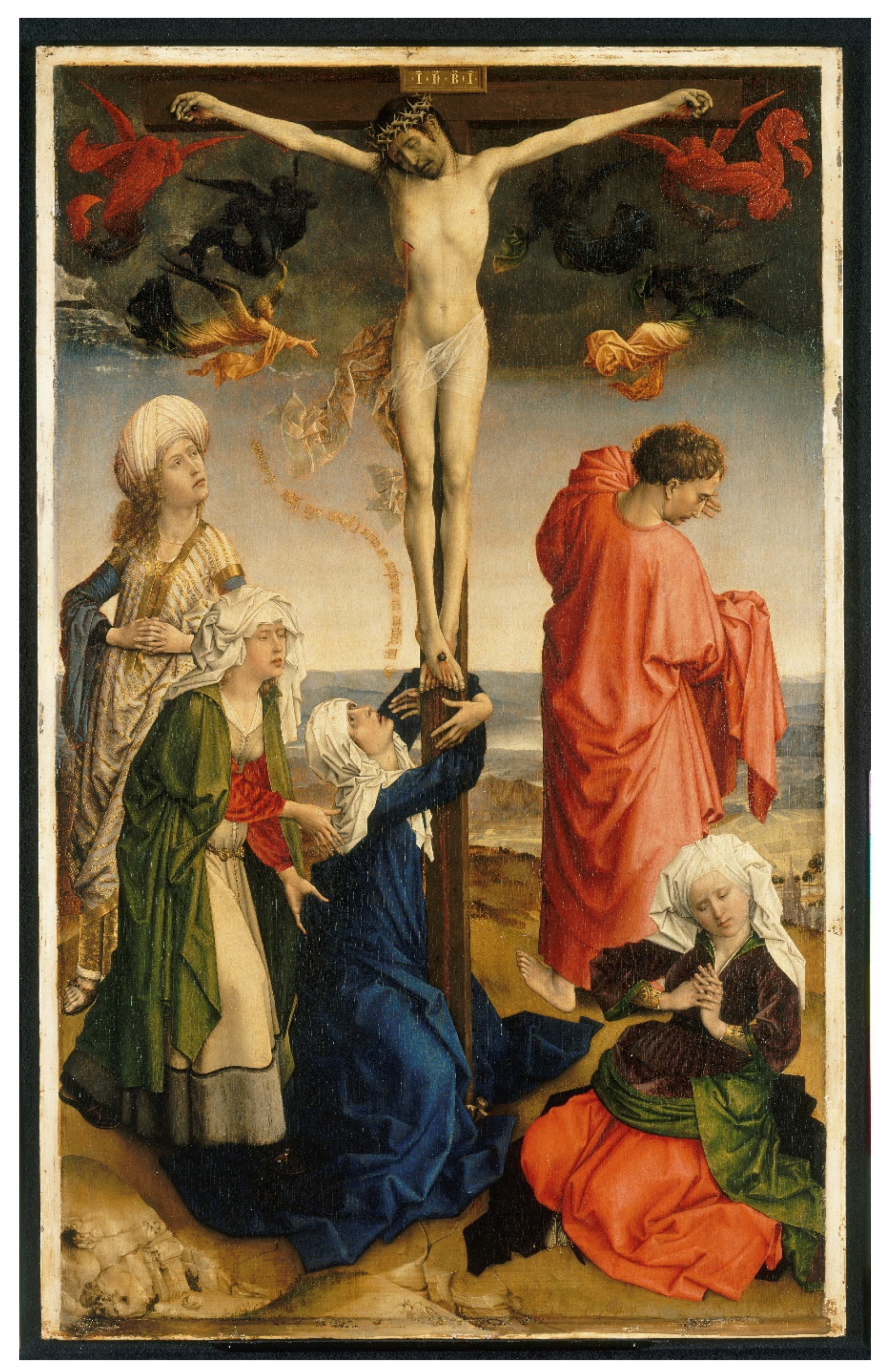

3. Rogier van der Weyden’s Crucifixion and the Concept of Disembodiment

“As stated above, in Christ’s conception His being born of a woman was in accordance with the laws of nature, but that He was born of a virgin was above the laws of nature. Now, such is the law of nature that in the generation of an animal the female supplies the matter, while the male is the active principle of generation […]. But a woman who conceives of a man is not a virgin. And consequently it belongs to the supernatural mode of Christ’s generation, that the active principle of generation was the supernatural power of God: but it belongs to the natural mode of His generation, that the matter from which His body was conceived is similar to the matter which other women supply for the conception of their offspring. Now, this matter […] is the woman’s blood, not any of her blood, but brought to a more perfect stage of secretion by the mother’s generative power, so as to be apt for conception. And therefore of such matter was Christ’s body conceived.”

“[…] hence He is said to have taken flesh from the Virgin, not that the matter from which His body was formed was actual flesh, but blood, which is flesh potentially.”

“When, therefore, it is about to rain and the air in the clouds is already condensing into raindrops but the rain is not yet falling, if there is, opposite the cloud, the sun or any other object so bright that the cloud mirrors it and reflection takes place from the cloud to the bright object opposite, an image of colour but not of shape must be produced. Each of the reflecting particles is invisibly small, and the continuous magnitude formed by them all is what we see; what appears to us is therefore necessarily a continuous magnitude of a single colour, since each of the reflecting particles gives off a colour the same as that of the continuous whole. Since, therefore, these conditions are theoretically possible, we may suppose that when the sun and the cloud stand in this relation and we are situated between them, the process of reflection will give rise to an image. And it is under these conditions and no others that the rainbow in fact appears.”

4. Conclusions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

| 1 | This is also a difficult undertaking as the backs of panel paintings have been neglected within research, making it difficult to find corresponding image material. In addition, many of the preserved overpaintings are in poor condition today as they were damaged, removed, or painted over in the past. (Cf. Verougstraete 2015, p. 86). |

| 2 | These are not necessarily triptychs or diptychs, and may single panels or portraits. |

| 3 | The idea of petrification is further worked out in the research of Rath 2020 and Kölle 2019 in relation to painted stone floors and painted columns of the Holy Blood. |

| 4 | For the panels described here: (Kemperdick and Sander 2009, p. 292; Campbell et al. 2008, p. 180f). |

| 5 | Beate Fricke was already able to fruitfully connect theories on the incarnation of Christ as well as on the similitude of God for the painted reverse side of Dürer’s Man of Sorrows in Karlsruhe, which she legitimizes with sources from John of Damascus (Cf. Fricke 2010a, pp. 183–206). Susan Müller Wusterwitz understands the reverses primarily as stimulants for religious devotion (Cf. Wusterwitz 2003, pp. 131–42). James Mundy argues for a memorative meaning, representing mainly on the reverse of portraits a triumph over death (Cf. Mundy 1988, pp. 37–43). In addition, there are theories that have dealt with similar appearances of stone imitations, primarily abstract-looking painted stone floors within pictorial works as an iconographic element. Georges Didi-Hubermann, for example, takes up the idea of the metaphysical concept of hylemorphism for the stone floors of the Annunciation scenes of Fra Angelico by searching for the form-giving power of God within the form-giving power of colour for sprinkled floor and wall surfaces in his Italian paintings (Cf. the study of Fra Angelico’s work in detail: Didi-Hubermann 1995). Markus Rath suggests, furthermore, an inherent visualization of the creative process of the artist for these very colour surfaces by defining colour as a substantial possibility and the artist as a form-giving instance (Cf. Rath 2020, pp. 334–59; Rath 2019, p. 322). The investigations listed here form a basis for the consideration of the sprinkled backs. |

| 6 | Both artists have been credited with other panels that have marbled reverses. Among Jan van Eyck’s works, a marbled reverse is preserved on the panels of Saint Barbara (Koninklijk Museum voor Schone Kunsten, Antwerp) and on the portrait of the so-called Timotheus (National Gallery, London). For Rogier van der Weyden, a marbled back can be traced on the Portrait of a Young Woman (Gemäldegalerie, Berlin) and on the Kolumba Altar (Alte Pinakothek, Munich), although the latter is now painted over (Cf. Wusterwitz 2003, pp. 131–42; Billinge et al. 2000, p. 44; Kemperdick and Sander 2009, p. 292). |

| 7 | As is the case in the studies of Didi-Hubermann and Markus Rath. (Cf. Didi-Hubermann 1995; Rath 2020, pp. 334–59). |

| 8 | A prominent example is the mappae clavicula from the late 12th century (Cf. Smith and Hawthorne 1974); furthermore, see on this topic: (Bucklow 2009). For the 17th century, Karin Leonhard has dealt with this subject (Cf. Leonhard 2013). |

| 9 | We find references to this understanding of painting in art theoretical writings, such as the Schedula diversarum artium of Theophilus Presbyter (12th century) and in the tract Libro dell’arte o trattato della pittura by Cennino Cennini, written around 1400, in which art theoretical ideas are combined with art technical instructions (Cf. Oltrogge 2014, pp. 105–7; Reudenbach 1994, pp. 1–16; Kruse 2000, pp. 305–25). Even if these texts cannot be concretely linked to the case studies presented here, they nevertheless refer to a discourse that will have been present in a theoretically-reflected artistic environment of the 15th century, which can be assumed for Jan van Eyck and Rogier van der Weyden. Furthermore, various works of van Eyck have been related to ancient texts, which suggests a scientific and philosophical interest in close connection with painting techniques and materiality (Cf. Preimesberger 1991, pp. 459–89; Lindnerova 2016, pp. 225–43; Lehmann 2007, pp. 21–40). |

| 10 | The profiled frame identifies the panel side of the marbling as the object of observation, and can therefore be taken seriously as a painting in its own regard. (Cf. Wusterwitz 2003, p. 129). |

| 11 | The structure of the layers of paint resembles the marbling found on the reverse side of Jan van Eyck’s depiction of St. Barbara, which was revealed by technological research carried out by Rachel Billinge, Hélène Verougstraete and Roger Van Schoute. (Cf. Billinge et al. 2000, p. 44). |

| 12 | Hélène Verougstraete and Roger van Schoute describe these decoration-types as jasper, or jaspered. They suggest that the term was used in the 15th century to describe spattered patterns that are similar to the grain of porphyry. See: (Verougstraete and Van Schoute 2000, p.110f). |

| 13 | (Verougstraete and Van Schoute 2000, p.111). The good state of preservation is probably due to the fact that in the 17th century the painting was kept in a box by the painters’ guild in Bruges, and exhibited only once a year in honor of Jan van Eyck. See: (Campbell et al. 2008, p. 180). |

| 14 | Pentcheva discusses in her research how multisensory experiences cause a change in the perception of the marble material. She proves the described reception of the materials through early Christian sources which connect the perception of the material with meditative inner images. (Cf. Pentcheva 2011, pp. 97–101). For the perception of actual marble as water, see Fabio Barry: (Barry 2007, pp. 627–56). |

| 15 | For the reverse effect of petrification in connection with representations of marble, see (Rath 2020, pp. 340–46). |

| 16 | The principle has been explained in research, especially for the formless floor and wall tiles of Italian Annunciation scenes of the Quattrocento (Cf. Didi-Hubermann 1995; Rath 2019, pp. 303–22). In general, about the principle of hylemorphism in relation to art technology, see: (Bucklow 2009, p. 78). |

| 17 | (Cf. Gludovatz 2004. p. 27). Elisabeth Dahnes argues that his choice of words indicates that a painting was completed by the artist’s own hand, which at the same time means that some paintings were not completed by van Eyck’s hand but by a workshop assistant. (Cf. Dhanes 1980, p. 179). |

| 18 | English translation by the author. Original quote: “Er (Van Eyck) wird sich der Doppeldeutigkeit bewusst gewesen sein, damit nicht nur die Vollendung des Gemäldes, sondern auch die der Frau zu bestätigen. Die Formbarkeit des Malmaterials durch den Künstler wird so die Formbarkeit der weiblichen “materia” durch den Ehemann parallelisiert, so gut er es vermochte, wie sein Wahlwort hinzugefügt und Margaretas vollendete Darstellung versichert. Die Polarisierung der Geschlechter in einen aktiven männlichen und einen passiven weiblichen Part ist hier nicht auf die biologische Komponente beschränkt, sondern findet seine Entsprechung im künstlerischen ‘Zeugungsakt’.” See: (Gludovatz 2004. p. 31). |

| 19 | A dendrochronological examination suggests a use of the wooden carrier from 1429. (Cf.: Kemperdick and Sander 2009, p. 294). |

| 20 | The phrase originates from a meditation book (Cf. Kemperdick and Sander 2009, p. 291). |

| 21 | I would like to thank Dr. Stephan Kemperdick for this information. |

| 22 | On the late medieval conception of pneuma, see: (Putscher 1973). |

| 23 | Wusterwitz describes the tradition in which the red drops of color are contemplated as drops of blood and can evoke individual episodes of Christ’s passion as well as the redeeming power of the blood (Cf. Wusterwitz 2003, p. 116). |

| 24 | She demonstrates this on a column of the Holy Blood which is depicted on the representation of Ecce Homo by Quentin Massys (Quentin Massys, Ecce Homo, 1520, oil on wood, 95 × 74 cm, Venice, Palazzo Ducale). Both the column (in the form of a capital) and the body of Christ are crowned here by a crown of thorns to increase the parallelism of the two motifs. (Cf.: Kölle 2019, p. 271). |

| 25 | On the visual link between colour and blood in Flemish art: (Cf. Fricke 2010b; Didi-Hubermann 2005, pp. 21–49; Schlie 2012, pp. 51–79; Gertsmann 2019, pp. 397–429; Tammen 2011, p. 245; Tammen 2012, pp. 302–22). |

| 26 | George Didi Hubermann takes this term from the Summa Theologica of Thomas Aquinas: Thomas Aquinas, Summa Theologiae 1947, III, 31, 5; III, 32, 3-4. Aquinas here again refers to Aristotelian metaphysics, which is based on the theory of hylemorphism (Cf. Didi-Hubermann 1995, p. 43). On the connection of the concept of causa materialis with the cloak of Mary: (cf. Gertsmann 2019, pp. 397–429). |

| 27 | In the representational convention of the late Middle Ages, the gold ground would be understood as pure light in which neither body nor space exist. According to Beate Fricke, it describes a transitory moment. See: (Fricke 2010a, p. 192f) |

| 28 | (Cennini 1922, cap. 147, p. 126). Compare Burioni for a positioning of the pictorial ground as an art-theoretical concept: (Burioni 2012, pp. 94–148, pp. 97, 102). |

References

- Aquinas, Thomas. 1947. Summa Theologiae. Translated by Fathers of the English Dominican Province. Available online: https://aquinas101.thomisticinstitute.org/st-index (accessed on 14 October 2021).

- Aristotle, Metaphysics. 1933. Volume I: Books 1–9. Translated by Hugh Treden-nick. Cambridge: Loeb Classical Library, p. 271. [Google Scholar]

- Aristotle, Meteorologica. 1952. Books 1–4. Translated by Henry Desmond Pritchard Lee. Cambridge: Loeb Classical Library, p. 397. [Google Scholar]

- Barry, Fabio. 2007. Walking on Water: Cosmic Floors in Antiquity and the Middle Ages. The Art Bulletin 4: 627–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Billinge, Rachel, Hélène Verougstraete, and Roger van Schoute. 2000. The Saint Barbara. In Investigating Jan van Eyck. Edited by Susan Foister, Sue Jones and Delphine Cool. Turnhout: Brepols, pp. 41–48. [Google Scholar]

- Böhme, Gernot und Hartmut. 1996. Feuer, Wasser, Erde, Luft. Eine Kulturgeschichte der Elemente. Munich: Beck. [Google Scholar]

- Bol, Marjolijn, and Ann-Sophie Lehmann. 2012. Painting Skin and Water Towards a Material Iconography of Translucent Motifs in Early Netherlandish Painting. In Rogier van der Weyden in Context, Papers presented at the Seventeenth Symposium for the Study of Underdrawing and Technology in Painting held in Leuven, 22–24 October 2009. Edited by Lorne Campbell, Jan van der Stock, Catherine Reynolds and Lieve Watteeuw. Leuven: Peeters, pp. 215–25. [Google Scholar]

- Bonus, Petrus. 1894. The New Pearl of Great Price. A Treatise Concerning the Treasure and Most Precious Stone of the Philosopher. Translated and Edited by Arthur Edward Waite. London: J. Elliott and Co. [Google Scholar]

- Bucklow, Spike. 2009. The Alchemy of Paint. Art Science and Secrets from the Middle Ages. London and New York: Boyars. [Google Scholar]

- Burioni, Matteo. 2012. Grund und campo. Die Metaphorik des Bildgrundes in der frühen Neuzeit oder: Paolo Uccellos Schlacht von San Romano. In Der Grund: Das Feld des Sichtbaren. Edited by Gottfried Boehm. Munich and Paderborn: Fink, pp. 94–148. [Google Scholar]

- Campbell, Lorne, Rice Louise, and Attwood Philip. 2008. Renaissance Faces. Van Eyck to Tizian, Exh. Cat. London: National Gallery. [Google Scholar]

- Cennini, Cennino. 1922. The Book of the Art of Cennino Cennini: A Contemporary Practical Treatise on Quattrocento Painting. Translated by Christiana J. Herringham. London: George Allen & Unwin. [Google Scholar]

- Dhanes, Elisabeth. 1980. Hubert und Jan van Eyck. Königstein and Taunus: Langewiesche. [Google Scholar]

- Didi-Hubermann, Georges. 1995. Fra Angelico. Unähnlichkeit und Figuration. Munich: Fink. [Google Scholar]

- Didi-Hubermann, Georges. 2005. Blut der Bilder. In Transfusionen. Blutbilder und Biopolitik in der Neuzeit. Edited by Anja Lauper. Zürich and Berlin: Diaphanes, pp. 21–49. [Google Scholar]

- Dunkerton, Jil, Rachel Morrison, Ashok Roy, Media Pigments, and Varnish Layers. 2017. On the Portrait of Margaret van Eyck. In Van Eyck Studies, Papers presented at the Eighteenth Symposium for the Study of Underdrawing and Technology in Painting, Brussels, 19–21 September 2012. Edited by Christina Currie, Bart Fransen, Valentine Hendriks, Cyriel Stroo and Dominique Vanwijnsberghe. Paris, Leuven and Bristol: Peeters, pp. 270–79. [Google Scholar]

- Dunlop, Anne. 2014. On the origins of European painting materials, real and imagined. In The Matter of Art. Materials, Practices, Cultural Logics, c. 1250–1750. Edited by Christy Anderson, Anne Dunlop and Pamela H. Smith. Manchester: Manchester University Press, pp. 68–96. [Google Scholar]

- Fricke, Beate. 2010a. Artifex ingreditur in artificium suum. Dürers Schmerzensmann in Karlsruhe und die Geschichte eines Arguments von Johannes von Damaskus. In Intellektualisierung und Mystifizierung Mittelalterlicher Kunst. Edited by Martin Büchsel and Rebecca Müller. Berlin: Mann, pp. 183–206. [Google Scholar]

- Fricke, Beate. 2010b. Zur Genealogie von Blutspuren. Blut als Metapher der Transformation auf dem Feldbacher Altar (ca. 1450). In L’Homme, L’Homme 21, Blut, Milch und Dann Heft 2. Weimar: Cologne, pp. 11–32. [Google Scholar]

- Ganz, David. 2008. Spuren der Bildwerdung. Zur Medialität gemalter Tränen im Spätmittelalter. In Tränen. Edited by Beate Söntgen. Munich: Fink, pp. 27–40. [Google Scholar]

- Gertsmann, Elina. 2019. Der blutige Umhang des textilen Leibs der Jungfrau. In Religiöses Wissen im vormodernen Europa. Schöpfung—Mutterschaft—Passion. Edited by Renate Dürr, Annette Gerok-Reiter, Andreas Holzem and Steffen Patzold. Paderborn: Ferdinand Schöningh, pp. 397–429. [Google Scholar]

- Gludovatz, Karin. 2004. Vom Ehemann vollendet: Die Bildwerdung der Margareta van Eyck. In (En)gendered: Frühneuzeitlicher Kunstdiskurs und weibliche Portraitkultur nördlich der Alpen. Edited by Simone Roggendorf and Sigrid Ruby. Marburg: Jonas Verlag, pp. 18–37. [Google Scholar]

- Haage, Bernhard Dietrich. 1996. Alchemie im Mittelalter. Ideen und Bilder—Von Zosimos bis Paracelsus. Zürich: Artemis & Winkler. [Google Scholar]

- Ivanovici, Vladimir. 2016. Manipulating Theophany: Light and Ritual in North Adriatic Architeture (ca. 400–ca. 800). Berlin: De Gruyter. [Google Scholar]

- Kemperdick, Stephan, and Jochen Sander. 2009. Der Meister von Flémalle und Rogier van der Weyden, Exh. Cat. Frankfurt am Main (Städel Museum): Ostfildern. [Google Scholar]

- Kölle, Julia. 2019. Versteinertes Blut. Heilig-Blut-Säulen in der flämischen Malerei um 1500. In Steinformen. Materialität, Qualität, Imitation. Edited by Isabella Augart, Maurice Saß and Iris Wenderholm. Berlin and Boston: De Gruyter, pp. 247–77. [Google Scholar]

- Kruse, Christiane. 2000. Fleisch werden, Fleisch malen. Malerei als ›incarnazione‹. Mediale Verfahren des Bildwerdens im Libro dell’Arte von Cennino Cennini. Zeitschrift für Kunstgeschichte 63: 305–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kruse, Christiane. 2003. Wozu Menschen Malen: Historische Begründungen eines Bildmediums. Munich: Fink. [Google Scholar]

- Lehmann, Ann-Sophie. 2007. Jan van Eyck und die Entdeckung der Leibfarbe. In Weder Haut Noch Fleisch. Das Inkarnat in der Kunstgeschichte. Edited by Daniela Bohde and Mechtild Fend. Berlin: Mann, pp. 21–40. [Google Scholar]

- Leonhard, Karin. 2013. Bildfelder. Stillleben und Naturstücke des 17. Jahrhunderts. Berlin: Akad.-Verl. [Google Scholar]

- Lindnerova, Klara. 2016. Die Rezeption der Naturalis Historia des Älteren Plinius bei Jan van Eyck. Die antike Quelle als Inspiration für die altniederländische Malerei an der Wende vom Mittelalter zur Neuzeit. In Kontinuitäten, Umbrüche, Zäsuren: Die Konstruktion von Epochen im Mittelalter und früher Neuzeit in interdisziplinärer Sichtung. Edited by Thomas Kühtreiber and Gabriele Schichta. Heidelberg: Universitätsverlag Winter, pp. 225–43. [Google Scholar]

- Magnus, Albertus. 1967. Book of Minerals. Translated by Dorothy Wyckoff. Oxford: Clarendon Press. [Google Scholar]

- Mundy, James. 1988. Porphyry and the “Posthumous” Fifteenth Century Portrait. Pantheon Internationale Jahreszeitschrift für Kunst XLVI: 37–43. [Google Scholar]

- Oltrogge, Doris. 2014. Ars picturae. Die Malerei in kunttechnologischen Quellen des frühen und hohen Mittelalters. In Zwischen Kunsthandwerk und Kunst: Die „Schedula diversarum artium". Edited by Andreas Speer. Berlin and Boston: De Gruyter, pp. 105–7. [Google Scholar]

- Panofsky, Erwin. 1966. Early Netherlandish Painting. Its Origins and Character. Cambridge: Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Pentcheva, Bissera V. 2011. Hagia Sophia and Multisensory Aesthetics. Gesta 50: 93–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Preimesberger, Rudolf Zu. 1991. Jan van Eycks Diptychon der Sammlung Thyssen Bornemisza. Zeitschrift für Kunstgeschichte 54: 459–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Putscher, Marielene. 1973. Pneuma. Spiritus. Geist. Vorstellungen vom Lebensantrieb in ihren geschichtlichen Wandlungen. Wiesbaden: Steiner. [Google Scholar]

- Rath, Markus. 2019. Annunziation und Petrifikation in der Malerei des Quattrocento. In Steinformen. Materialität, Qualität, Imitation. Edited by Isabella Augart, Maurice Saß and Iris Wenderholm. Berlin and Boston: De Gruyter, pp. 303–22. [Google Scholar]

- Rath, Markus. 2020. Substanzaktivität. Farbe als prima materia im Andachtsbild der Frühen Neuzeit. Zeitschrift für Kunstgeschichte 83: 334–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reudenbach, Bruno. 1994. Ornatus materialis Domus. Die theologische Legitimation handwerklicher Künste bei Theophilus. In Studien zur Geschichte der europäischen Skulptur im 12./13. Jahrhundert. Heinrich: Frankfurt a. M., pp. 1–16. [Google Scholar]

- Schlie, Heike. 2012. Blut und Farbe: Sakramentale Dimensionen der Frühneuzeitlichen Bild und Kunsttheorie. In Sakramentale Repräsentation. Substanz, Zeichen und Präsenz in der Frühen Neuzeit. Edited by Stefanie Ertz, Heike Schlie and Daniel Weidner. Munich: Fink, pp. 51–79. [Google Scholar]

- Schmitz, Rolf P. 1999. “Form/Materie”. In Lexikon des Mittelalters IV. Edited by Robert-Henri Bautier. Stuttgart and Weimar: Metzler, pp. 635–46. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, Cyril Stanley, and John G. Hawthorne. 1974. Mappae Clavicula. A Little Key to the World of Medieval Techniques. Translations of the American Philosophical Society held in Philadelphia for Promoting Useful Knowledge. Philadelphia: American Philosophical Society, vol. 64, Part 4. [Google Scholar]

- Tammen, Silke. 2011. Blut ist ein ganz besonderer Grund. In Bild und Text im Mittelalter. Edited by Karin Krause and Barbara Schellewald. Cologne, Weimar and Vienna: Böhlau, pp. 229–51. [Google Scholar]

- Tammen, Silke. 2012. Rot sehen—Blut berühren. Blutige Seiten und Passionsmemoria in einem spätmittelalterlichen Andachtsbüchlein (Brit. Libr., Ms. Egerton 1821). In Die Farben Imaginierter Welten: Zur Kulturgeschichte ihrer Codierung in Literatur und Kunst vom Mittelalter bis zur Gegenwart. Edited by Monika Schausten Akad. Berlin: Akad.-Verl., pp. 302–22. [Google Scholar]

- Tvrzníková, Veronika. 2016. Ritual, Body and Perception: A New Perspective on the Orthodox Baptistery of Ravenna. Available online: https://theses.cz/id/tw2cfl/ (accessed on 14 October 2021).

- Verougstraete, Hélène Roger, and Frames Van Schoute. 2000. Supports of some Eyckian Paintings. In Investigating Jan van Eyck. Edited by Susan Foister, Sue Jones and Delphine Cool. Turnhout: Brepols, pp. 107–17. [Google Scholar]

- Verougstraete, Hélène. 2015. Frames and Supports in 15th- and 16th Century Southern Netherlandish Painting. Brussels: Royal Institute for Cultural Heritage. [Google Scholar]

- Wilson, Malcolm. 2013. Structure and Method in Aristotle’s Meteorologica: A More Disorderly Nature. Cambridge: Cambridge Univ. Press. [Google Scholar]

- Wusterwitz, Susan Müller. 2003. Bildnis und Tugendübung. Zur Funktion früher niederländischer Portraittafeln in der individuellen Frömmigkeitspraxis des 15. Jahrhunderts. Hamburg: Mikrofiche. [Google Scholar]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Borgers, K. Recto and Verso: The Pictorial Fronts and the Marbled Reverses of Two Flemish Panel Paintings. Arts 2022, 11, 10. https://doi.org/10.3390/arts11010010

Borgers K. Recto and Verso: The Pictorial Fronts and the Marbled Reverses of Two Flemish Panel Paintings. Arts. 2022; 11(1):10. https://doi.org/10.3390/arts11010010

Chicago/Turabian StyleBorgers, Kathrin. 2022. "Recto and Verso: The Pictorial Fronts and the Marbled Reverses of Two Flemish Panel Paintings" Arts 11, no. 1: 10. https://doi.org/10.3390/arts11010010

APA StyleBorgers, K. (2022). Recto and Verso: The Pictorial Fronts and the Marbled Reverses of Two Flemish Panel Paintings. Arts, 11(1), 10. https://doi.org/10.3390/arts11010010