1. New Visions

Despite contributions to some important international exhibitions in the late 1960s and early 1970s, Belgian artist Raoul De Keyser (1930–2012) only acquired international fame in the 1990s and early 2000s when he participated in leading exhibitions such as Documenta (1992) or the Venice Biennale (2007) while also having one-man shows in Kunsthalle Bern (1991), Portikus Frankfurt (1991), Royal Hibernian Academy Dublin (2000), Whitechapel Gallery London (2004), Kunstmuseum Bonn (2009), and David Zwirner Gallery New York (2001, 2003, 2006, 2009, and 2011) (

Jacobs 2000,

2007;

Searle 2004;

Storr 2011;

Germann and Schwenk 2018). De Keyser, however, had started his artistic career in the late 1940s (

Jacobs 2015). In the early 1950s, however, he cast aside his artistic ambitions and started a career as a civil servant, combining it with free-lance sports and art journalism. In 1963–1964, he resumed his artistic career after an encounter with painter Roger Raveel (1921–2013), who, after having experimented with lyrical abstraction in the 1950s, had just developed a form of figurative painting, which was immediately recognized as a local variation of Pop Art and

nouveau réalisme.

1 Despite its affinities with the vanguard art currents of the day, Raveel’s art was rooted in the local and the vernacular, as demonstrated by his interest in a typically Flemish rural backyard with a clothesline and little partition walls of concrete (

Sizoo 1969;

Dewulf et al. 2003;

Jooris 2003).

As a critic in the late 1950s and early 1960s, De Keyser had written about Raveel, and, in 1963, he spent several months studying under Raveel at Deinze’s Academy of Fine Arts, becoming an artist again. De Keyser’s paintings of 1964 and the following years are unmistakably marked by an interest in his everyday surroundings, typical of Raveel and the so-called

Nieuwe Visie (New Vision), a Belgian art current that not only shows resemblances with

nouveau réalisme in France but also with

nieuwe figuratie in the Netherlands and practices by contemporaneous artists such as Valerio Adami, Patrick Caulfield, R.B. Kitaj, and Richard Lindner. Instead of the lyrical abstraction of the previous decade (in Belgium exemplified by CoBrA and local followers of the Ecole de Paris), the

Nieuwe Visie stood for a new kind of figuration that was unmistakably modern as it was inspired by the bold language of comics or advertising (

Jooris 1967;

Bekkers and Sizoo 1972;

Geirlandt 1973). After two or three years of (renewed) artistic practice, De Keyser’s art was presented and celebrated in the context of a regeneration of figurative painting among many vanguard artists all over Europe—he participated, for instance, in the

Premio Lissone Internazionale di Pittura exhibition in Italy in the fall of 1967, which also included works by Valerio Adami, Evelyne Axell, Peter Klasen, and Tom Philips, among others. Likewise, together with Adami, Axell, Klasen, and Philips, De Keyser’s work was also shown, in the summer of 1968, at the third edition of the

Alternative Attuali in L’Aquila, which also included works by Enrico Baj, David Hockney, Eduardo Arroyo, Patrick Caulfield, Allen Jones, Jim Dine, and others.

2The breakthrough of the

Nieuwe Visie coincided more or less with the moment the Belgian art world shifted its focus from Paris to the Anglophone, particularly the American art world. Pop Art specifically was welcomed by a new generation of artists—strikingly, the artists of the

Nieuwe Visie were hardly interested in French

nouveau réalisme. American and British Pop Art were discussed in Belgian art journals, while some major works became part of leading private Belgian art collections.

3 Particularly relevant for De Keyser is that the focus on new artistic tendencies in American art did not only include Pop Art but also the Post-Painterly Abstraction and Hard Edge—in a 1965 interview, for instance, he expresses his admiration for Kenneth Noland (

Jooris 1965). Landmark exhibitions at the Brussels Palais des Beaux-Arts such as

New American Painting (1958),

Art USA Now (1964), and

Pop Art, Nouveau Réalisme, etc. (1965) triggered the dissemination of the new American art trends. Like many other young Belgian artists and critics, Raoul De Keyser also came into contact with works by leading American modernist painters at exhibitions in Dutch museums such as

American Pop Art (Stedelijk Museum, Amsterdam 1964) and one-man shows by Robert Indiana at the van Abbe Museum in Eindhoven (1966) and Al Held at the Stedelijk Museum in Amsterdam (1966).

4 Equally important was De Keyser’s visit to the 1966 exhibition

Vormen van de Kleur (

New Shapes of Color) at the Stedelijk Museum Amsterdam, which included works by Josef Albers, Al Held, Donald Judd, Ellsworth Kelly, Morris Louis, Barnett Newman, Kenneth Noland, and Frank Stella, among others (

Raoul De Keyser: Rondom de Werkelijkheid 1970). In a 1975 interview, De Keyser stated that the works by these American artists “had another kind of impact than in most cases of European art. That art was more open. They did not play hide and seek like many painters of the Ecole de Paris. Their paintings evoked a contact with life and a preoccupation with painting.” (

Jooris 1975, p. 15).

The transition of the artistic horizon from Paris to New York also coincided with a paradigm shift, exchanging an existentialism-inspired art discourse favoring psychological, symbolic, and mythic associations for a sober yet playful rediscovery of the everyday. Coining the concept of the “

Nieuwe Visie,” poet and critic Roland Jooris noted that the local art world was previously “entangled in the pale after-effects of post-expressionism, in the limited grandiloquence of the ‘Ecole de Paris,’ in surreal acrobatics, or in matter painting. The link between the changing image of reality, worldview, and art, between space, time, thing, and man had been completely lost.” (

Jooris 1967, p. 43). In the works by Raveel, De Keyser, and others, Jooris recognized a new climate characterized by a “joyful atmosphere, a clear and clarifying imagery, a ludic element, humor, color as the preeminent instrument of expression, the desire to merge painting with reality, a sense of relativity (both art historical and visual), a connection with the immediate surroundings, a fracture of existing aesthetic categories, an emphasis on the visual and a tendency towards objectification.” (

Jooris 1967, p. 43). Jooris particularly noticed these elements in works by De Keyser, which “disarm the viewer immediately because of their overwhelming simplicity and clarity (…). It is the simplicity of forms, of colors in their direct and clear surfaces, of the functional ‘thing’ that becomes ‘plaything’ in its disconnection. It is also the simplicity of a new ‘ludic’ man (to quote Constant) who has liberated himself from the Earnestness, of Culture, and Artificiality.” (

Jooris 1966, p. 6).

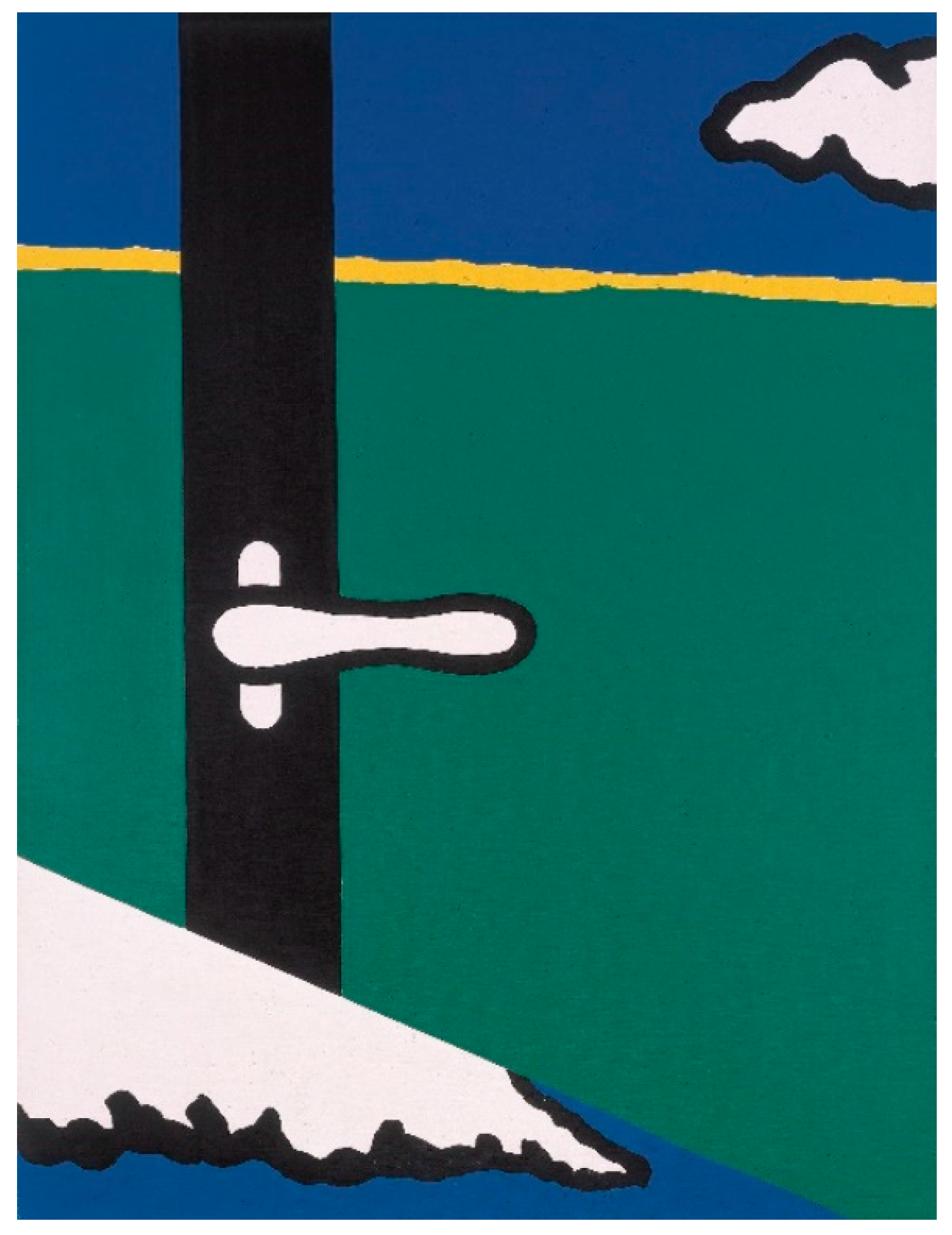

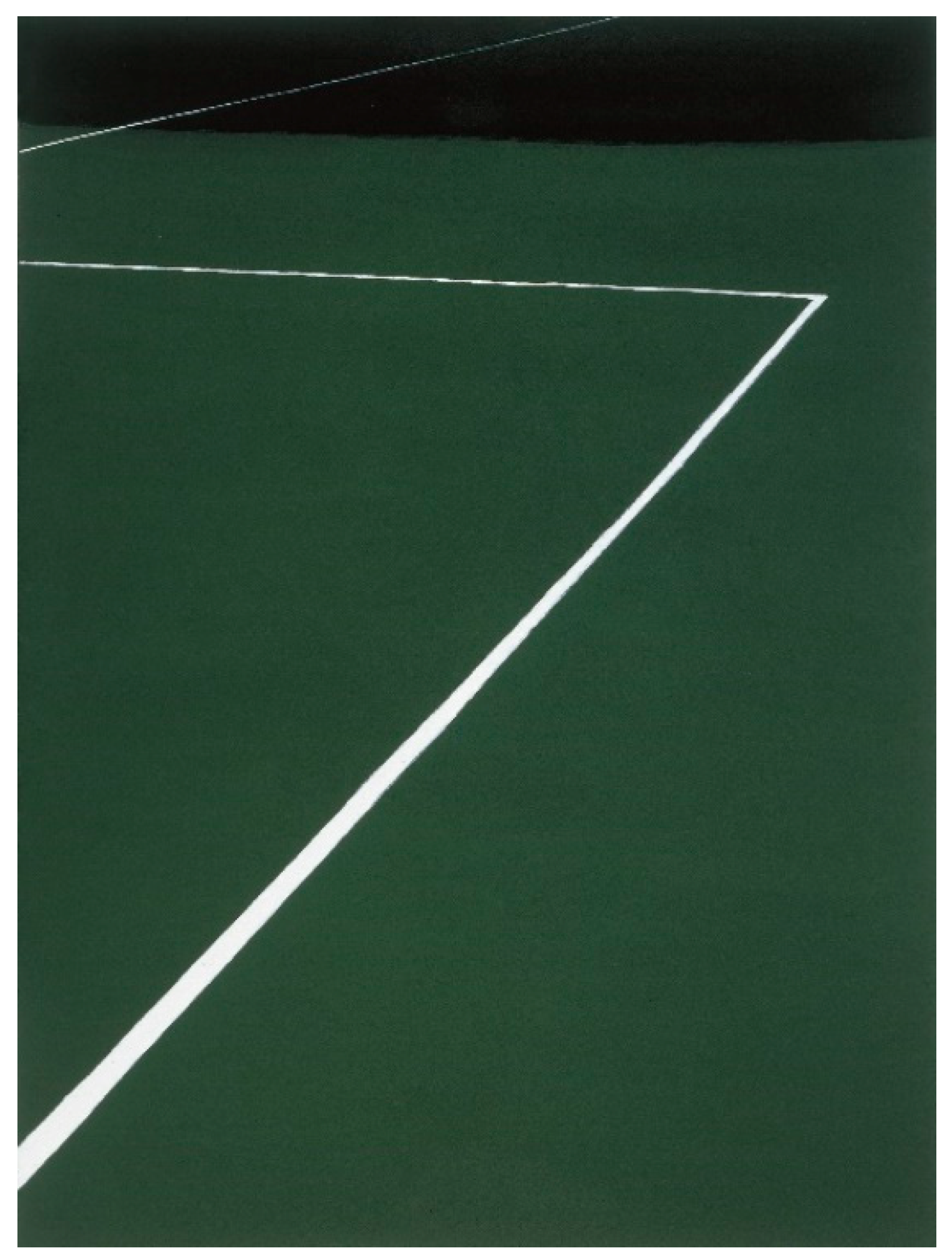

As the works by Raveel and the other painters of the

Nieuwe Visie in the mid and late 1960s, De Keyser’s canvasses depict everyday subjects—De Keyser’s recurrent motifs in those years are windows (

Figure 1), riverbanks, sports infrastructure and paraphernalia (

Figure 2), camping tents (

Figure 3), bungalows, et cetera. Rather than evoking an idyllic natural landscape, they show that Belgium’s countryside was in the process of a radical transformation: a landscape marked by suburbanization, new road infrastructure, and new facilities for sports and recreation (

Laureyns 2013). In so doing, De Keyser’s works are not only exemplary for his own career but also for a major transformation of both the Belgian (physical and social) landscape and the Belgian art world. De Keyser’s themes (sports, leisure, road infrastructure), which indicate the drastic changes in the environment, as well as his artistic strategies (ready-made appearances and the physicality of objecthood) that resonate with American modernism, are unmistakably connected to the changes that Belgium was undergoing in the 1960s: a period of economic prosperity. The shift in the art world, exchanging its focus on Paris and French and Francophone culture for a focus on New York and Anglo-Saxon culture, went hand in hand with the economic power shifts that mark Belgium in that era, its weight moving from the southern and French-speaking part of the country, which underwent early and rapid industrialization in the nineteenth century, to the northern Flemish part, which had remained predominantly rural until the mid-twentieth century. The late modernization of the Flemish part, exemplified by the postwar suburbanization of the landscape rather than the development of a metropolitan culture, tallied with the cultural shift from French culture as guiding (also in Flanders where the bourgeoisie was French-speaking) to the appropriation of a global Anglo-Saxon culture.

With his depictions of everyday subjects as well as with a simplified figuration reminiscent of advertising and comic books, De Keyser is certainly indebted to American Pop Art. However, his works exchange the spectacular signs of American consumer culture for the vernacular and rather unspectacular imagery of this new Flemish landscape. Several early works by De Keyser show some kind of anecdotal atmosphere, particularly when they focus on clearly recognizable objects such as cars, bikes, garden hoses, zippers, et cetera. However, De Keyser quickly exchanged this anecdotal element for an interest in the chromatic impact of large surfaces, the texture of the paint, and the material of the support, echoing the agenda of various tendencies in postwar American modernist painting such as Color-Field Painting, Post-Painterly Abstraction, Stained Color-Field Abstraction, Hard Edge, and Minimal Art. Switching from oil to acrylic in 1967, De Keyser exchanged the impastoed surfaces of his early works for large, flattened color surfaces marked by thick black contours. In addition, De Keyser’s works were characterized by a high degree of reflexivity, perfectly indicated by the importance of particular motifs such as windows, chalk lines, and tents. Windows, of course, had been used by many leading modernist painters (Henri Matisse, Robert Delaunay, Marcel Duchamp, René Magritte, Ellsworth Kelly, et cetera) testing out or deconstructing the illusionist ambitions of the medium of painting (

Figure 1). More particularly, De Keyser’s self-referential ambitions are demonstrated by his chalk lines (

Figure 2). Just as Jasper Johns avoided the pitfall of illusionism by representing objects that were already flat (flags, maps, shooting targets, numbers), De Keyser identifies the flat character of the football pitch with the two-dimensionality of painting, while the drawing of chalk lines is seen as the execution of a pictorial act. Just as a groundsman transforms a lawn into a football pitch, so, too, De Keyser transforms a blank canvas into a painting. Similarly, as the chalk lines on the football pitch triggered De Keyser to make paintings of simple configurations of lines, the tent paintings are simply canvases with canvas as their preeminent motif. While perfectly in line with the Nieuwe Visie’s fascination for various forms of democratic leisure, the tent paintings are studies of colored textiles and fabrics and how they can be stretched (

Figure 3).

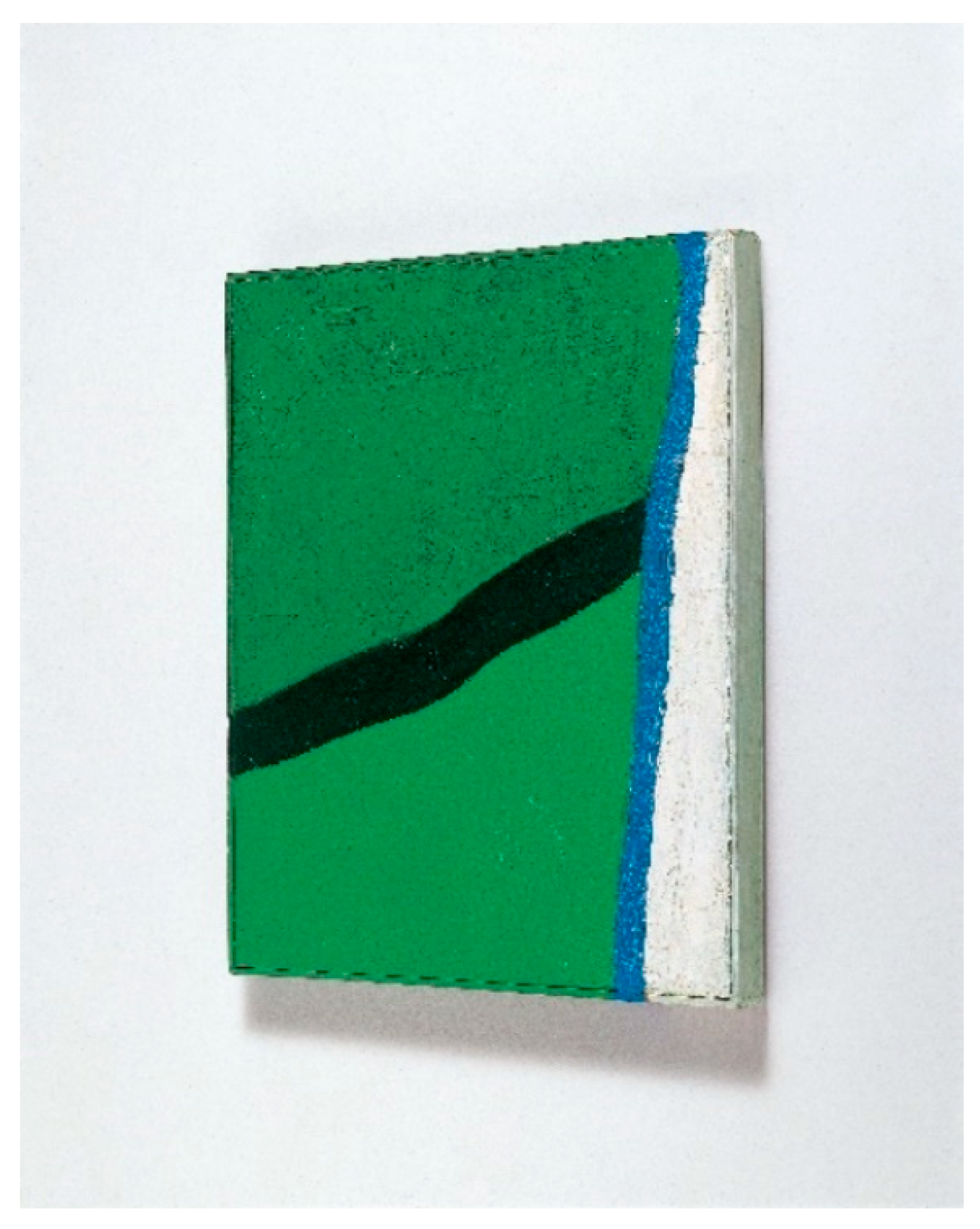

2. Linen Boxes

The gradual disappearance of depth in his paintings triggered De Keyser’s fascination for their “objecthood”. By allowing the painting to flow over the edges of the frame, some of his paintings become three-dimensional “things” rather than fictitious windows in a wall. This is certainly the case in the 1964–1966 untitled work that is part of the collection of the Groeningemuseum in Bruges, which is one of his last paintings with a frame (

Figure 4). What is more, the frame is entirely part of the painting, which stands out with its thick stretcher, presenting itself as a tangible, three-dimensional object made of wood, canvas, and paint. In a 1975 interview, De Keyser, referring to its abstract landscape merely evoked by a juxtaposition of green, blue, white, and black fields as well as to his later

Linen Boxes, called it “a ‘half landscape box.’ (…) The wooden little slat that was meant as a frame got involved in the painting. It therefore acquires a kind of tactility.” (

Jooris 1975). Its objecthood is evident in the many reproductions of this work that have been included in many important exhibitions, in that it is often photographed not frontally but from an oblique angle, showing it as a three-dimensional entity.

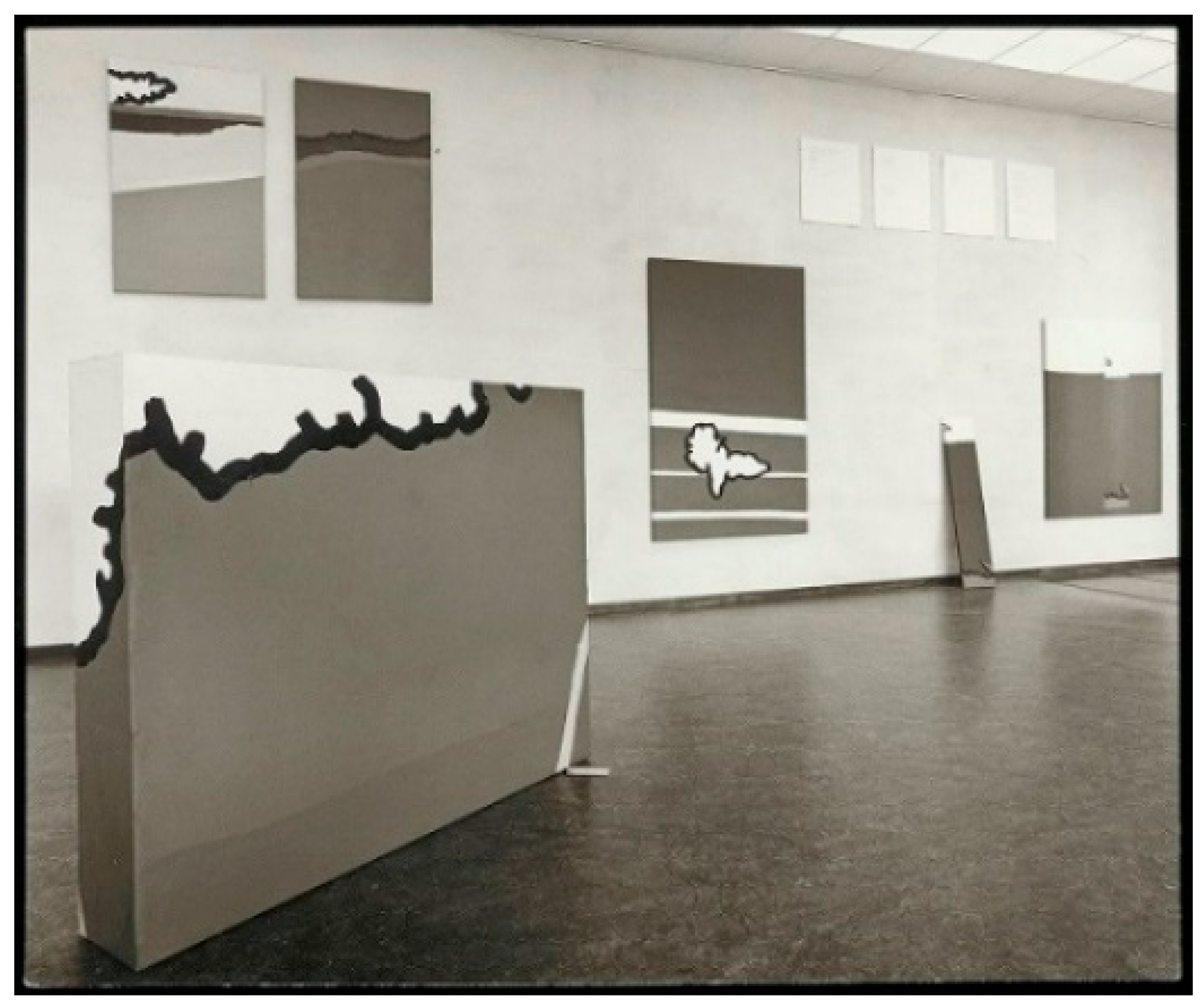

5Unmistakably inspired by various experiments in American late-modernist painting (Hard Edge, Shaped Canvas, Minimal Art), De Keyser eventually detached the picture plane from the wall completely, turning the painting into a material and tangible object. Between 1966 and 1971, De Keyser experimented with various kinds of “three-dimensional” paintings. For instance, he created cube-like structures made of painted canvas stretched over wooden slats, showing the same colors as his contemporaneous two-dimensional paintings (

Figure 5). These cubes were destroyed by the artist himself in the late 1960s, after which they fell completely into oblivion. Echoing the reluctance of most minimal artists to call their works “sculptures,” Roland Jooris tellingly described De Keyser’s colorful cubes as “things” as they enabled the artist to express his connection with reality and the everyday (

Jooris 1966). As they evoked folding, cutting, and reversing, these constructions also reminded Jooris of toys.

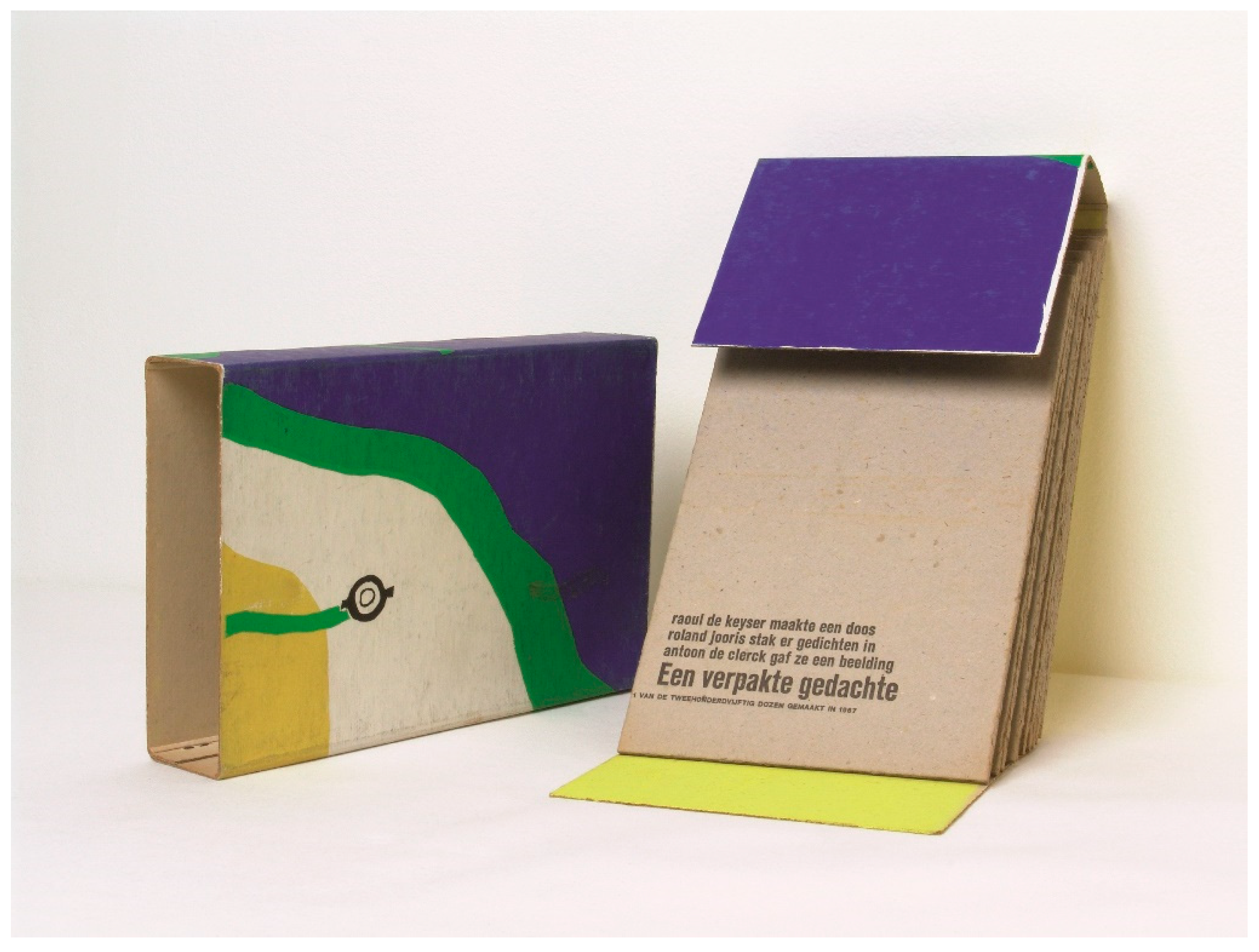

This ludic element also marks other three-dimensional works that De Keyser made in the late 1960s and early 1970s, particularly the seven so-called

Linnen Dozen (

Linen Boxes) in slightly variable sizes (

Figure 3 and

Figure 6,

Figure 7 and

Figure 8). The first two boxes (measuring 120 × 150 × 25 cm) and the seventh (115 × 150 × 25 cm) have a “horizontal” appearance, whereas the others present themselves as “vertical” slabs, measuring 155 × 150 × 25 cm (IV), 145 × 120 × 25 cm (V), and 150 × 120 × 25 cm (VI). The imagery of/on these seven slab-like structures is clearly related to several other (two-dimensional) paintings by De Keyser, evoking lawns with a garden hose (

Linnen Doos I and

II), clouds (

III), landscapes (

Linnen Doos IV–veldsituatie), tents (on

V and

VI), or soccer goals (on

VII). With these depictions, they “represent” something, creating a kind of mental or fictive space not unlike their “two-dimensional” companion pieces. At the same time, however, consisting of canvases stretched over wooden frames, they are emphatically present as three-dimensional and material things occupying the exhibition space. In general, throughout the four-year period in which these seven boxes were made, there is an evolution towards a more compact appearance due to the increasingly minimalist language (

Jooris 1972). In addition, color and canvas increasingly merge into one another as we can feel the grain of the canvas through the color. Furthermore, the boxes evoke a kind of packaging or wrapping of an object, something that is enhanced by the fact that staples are visible on the edges. The idea of packaging was even developed literally with

Een Verpakte Gedachte (A Packed Idea, 1967), a set of poems by Roland Jooris kept together in a silkscreened cardboard box by De Keyser, which can be considered as a miniature version of

Linnen Doos II (

Figure 6 and

Figure 9).

Although critics like Roland Patteeuw connected De Keyser’s boxes to Claes Oldenburg’s objects or Andy Warhol’s

Brillo Boxes (

Patteeuw 1969), they clearly answer to different aspirations. Neither do these linen boxes incorporate concrete objects into a painting, like Rauschenberg’s “combine paintings” or certain works by Raveel, who incorporated “real” objects such as a pigeon in a cage or bedposts into some of his paintings of the early 1960s—De Keyser, too, included “real” objects in some of his 1965–1966 paintings such as a zipper in

Het Helder Wegen van een Ruimte (1965) or a safety pin in

Walter (1966). Some installation views of the 1967–1968

Linen Box III (Freethiel), now in the Museum of Ostend, show that a label was attached to it, as if it is a box ready for shipment or a commodity with a price tag, emphasizing its association with Pop Art’s fascination for everyday objects and consumer culture (

Figure 7).

First and foremost, however, the spatiality and tangibility of De Keyser’s

Linen Boxes bring them closer to the so-called “Specific Objects” by American minimalist artists of the 1960s. Like Judd’s works, De Keyser’s boxes are “neither painting nor sculpture,” but a paradoxical hybrid, like “a picture [which] stops being a picture and turns into an arbitrary object.” They seem to occupy the third dimension and thus “real space”. However, in contrast with Judd’s “objects”, they do not get rid of “the problem of illusionism” (

Judd 1975, p. 181). Moreover, they show bright, “poppy” colors or the soft hues reminiscent of Color-Field Painting instead of the non-colors white, black, and grey favored by minimalists. Nonetheless, fully-fledged three-dimensional objects like minimalist “specific objects”, De Keyser’s

Linen Boxes assert their presence in the exhibition space, inviting the beholder to walk around them. They even share the volume and scale of key minimalist works like some of Dan Flavin’s neons, Brice Marden’s Back Paintings, or various works by Donald Judd or Carl Andre. With a maximum height of one meter and a half, they effortlessly enter into a physical confrontation with the viewer (

Colpitt 1990, pp. 73–79). Their presence and “literalness” is, in some cases, even emphasized further.

Linnen Doos V and

VI not only refer to tents as three-dimensional constructions made of slats and almost monochrome stretches of canvas, they simply

are tents, too (

Figure 3). The visible cuts and stitches and the insertion of an eyelet in one of the corners contribute to this effect. Likewise, consisting of grass green surfaces surrounded by white lines,

Linnen Doos VII not only evokes a soccer pitch, it also presents itself as a three-dimensional goal of 5-a-side football (

Figure 8).

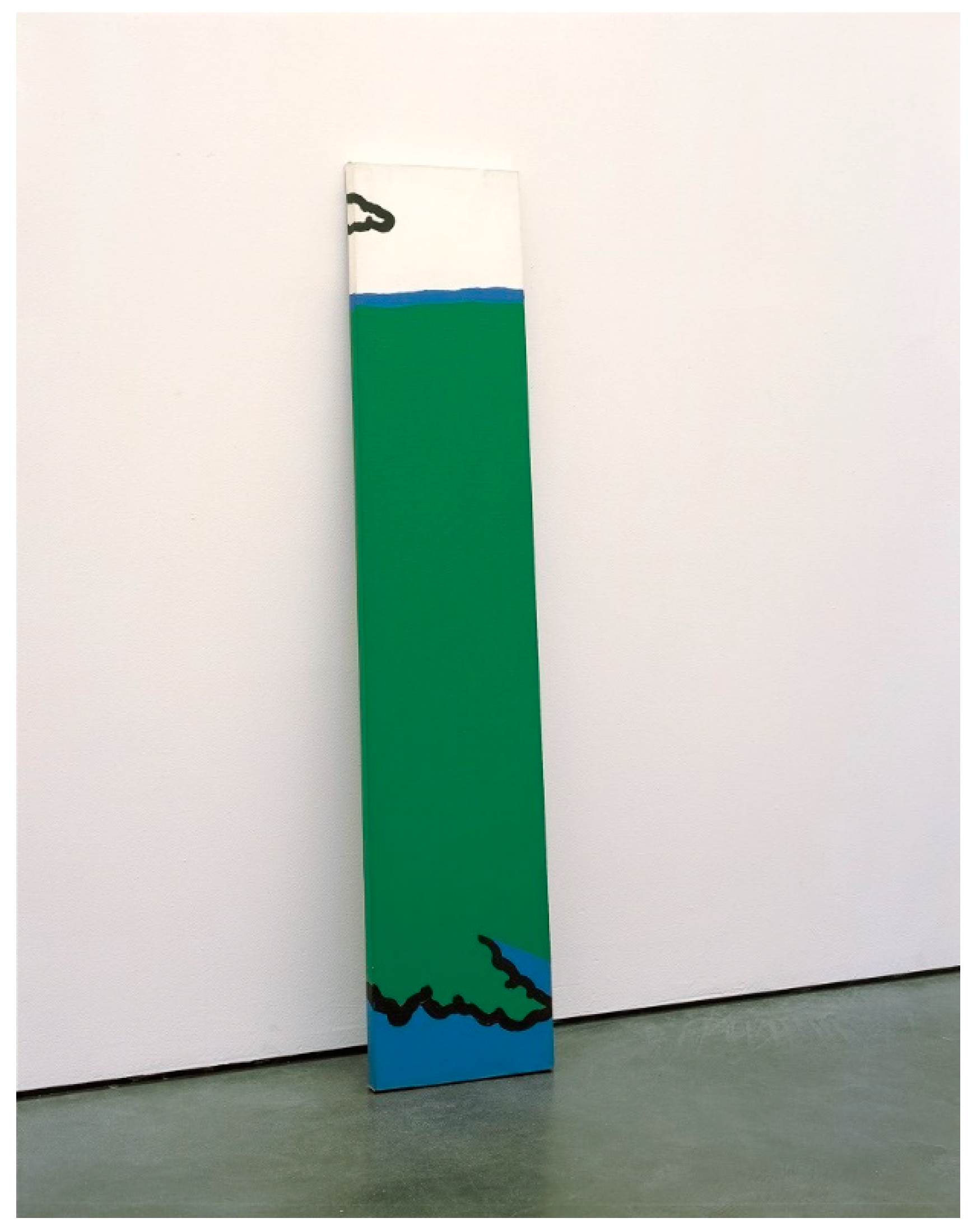

3. Slices

More or less in the same years in which De Keyser produced his seven

Linnen Dozen, he also made seven so-called

Slices (

Figure 10,

Figure 11 and

Figure 12). The

Slices are small upright stretchers with canvas, which, due to their size (120 × 25 × 2.5 cm), can be interpreted as surfaces that have been cut from the sides of the

Linen Boxes. Initially painted in oil and later in acrylic, these canvases display a stylistic development similar to the

Linen Boxes and De Keyser’s painting in general. Whereas the five earliest ones evoke landscape elements, the two last ones, painted in 1971, seem more abstract as their compositions consisting of red and white wide strips emphasize their vertical shapes.

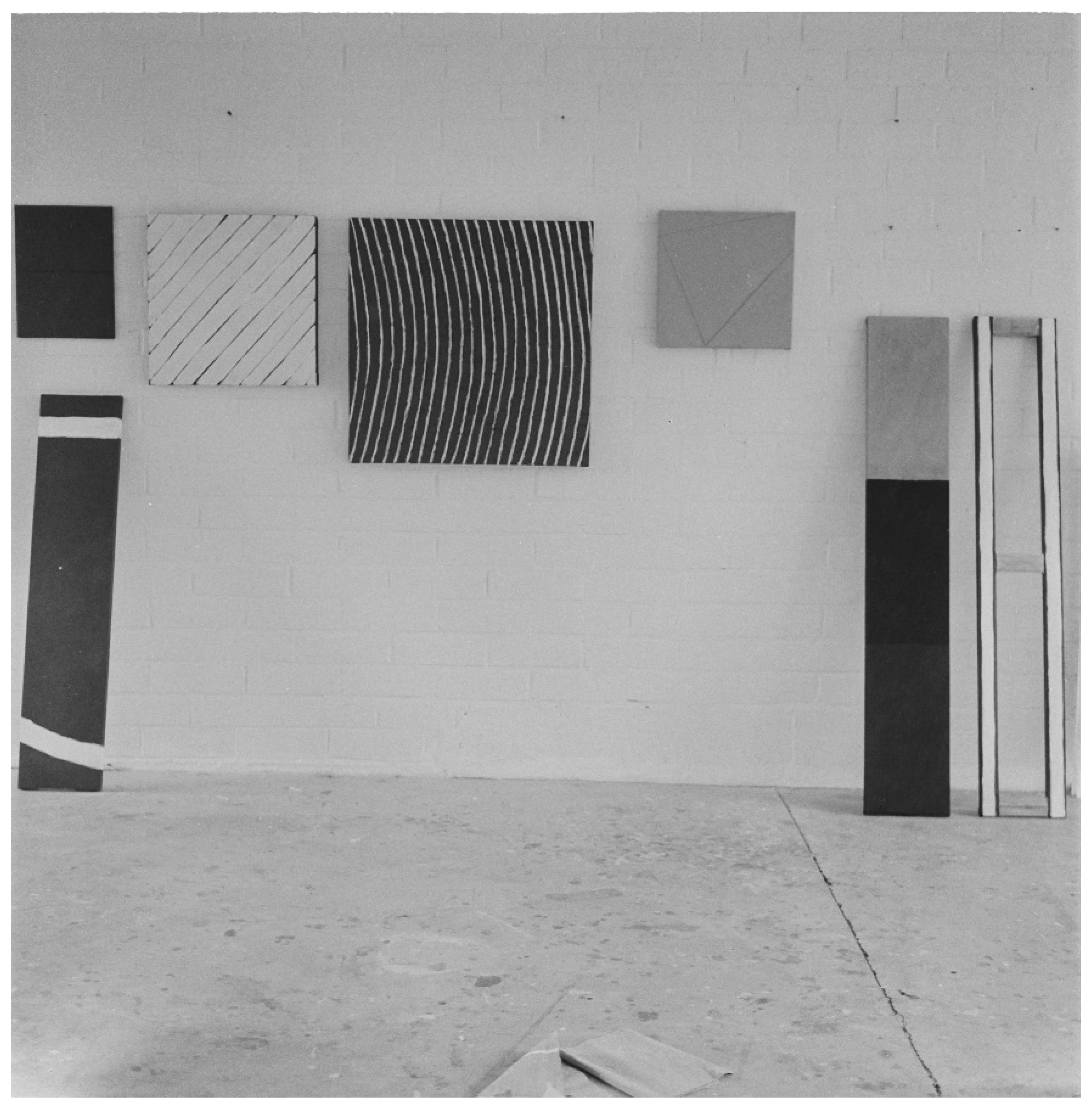

Placed on the floor and leaning against the wall, the Slices undermine the “window effect” of conventional painting, tallying with minimalist practices in which works frequently activate an unusual relationship with the floor or wall of the exhibition space. Bringing to mind similar experiments by artists such as John McCracken, Jo Baer, Blinky Palermo, and Marthe Wéry, De Keyser’s Slices demonstrate his interest in the painting as an object. However, in contrast with the practices of some of these artists, De Keyser’s Linen Boxes and Slices do not really “activate” their surrounding space. They remain “things” rather than architectural elements organizing the exhibition space, even evoking another fictitious realm because of their fragmentary representation of landscapes, clouds, garden hoses, and tents, rather than emphatically organizing the entire exhibition space.

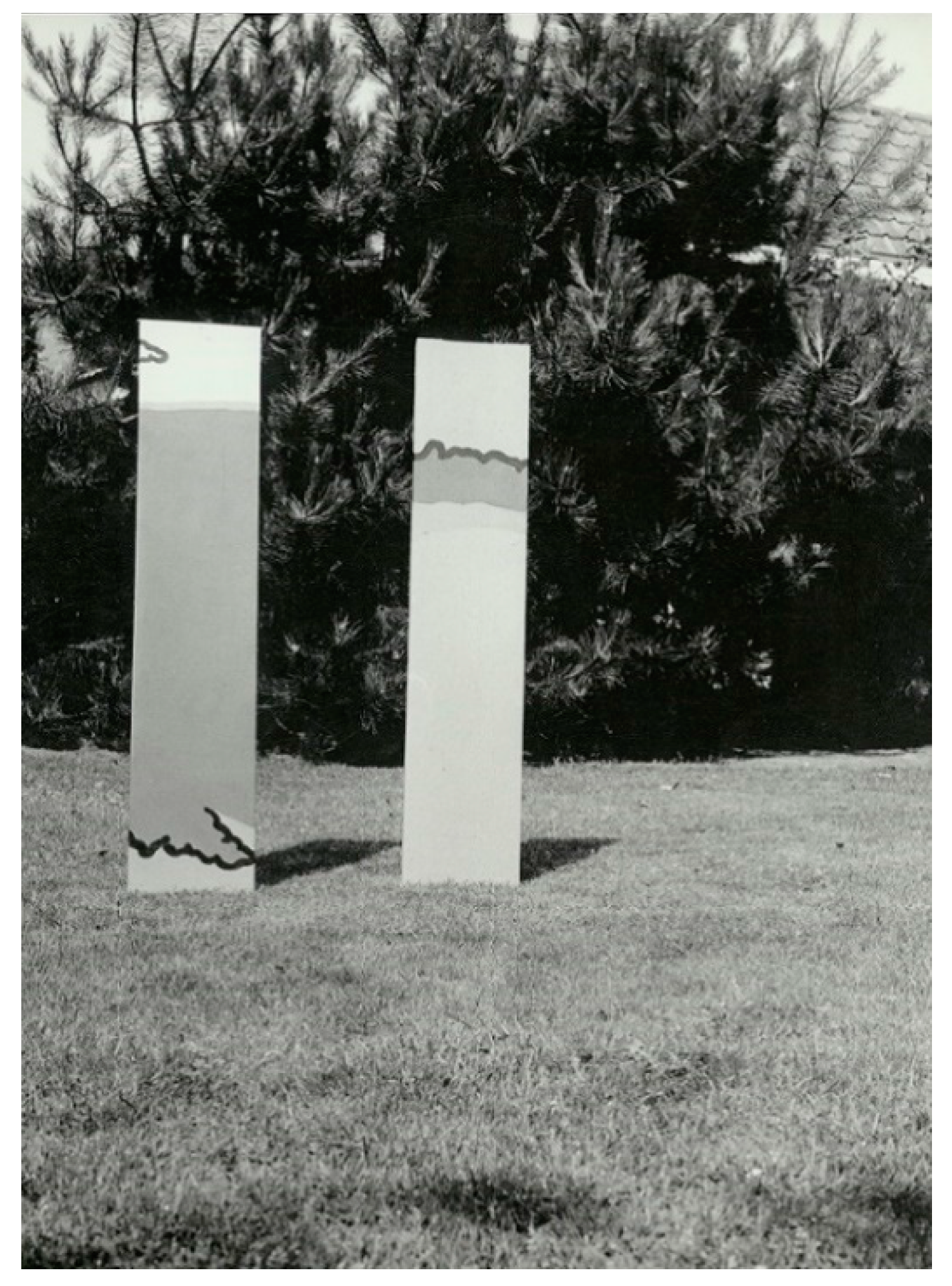

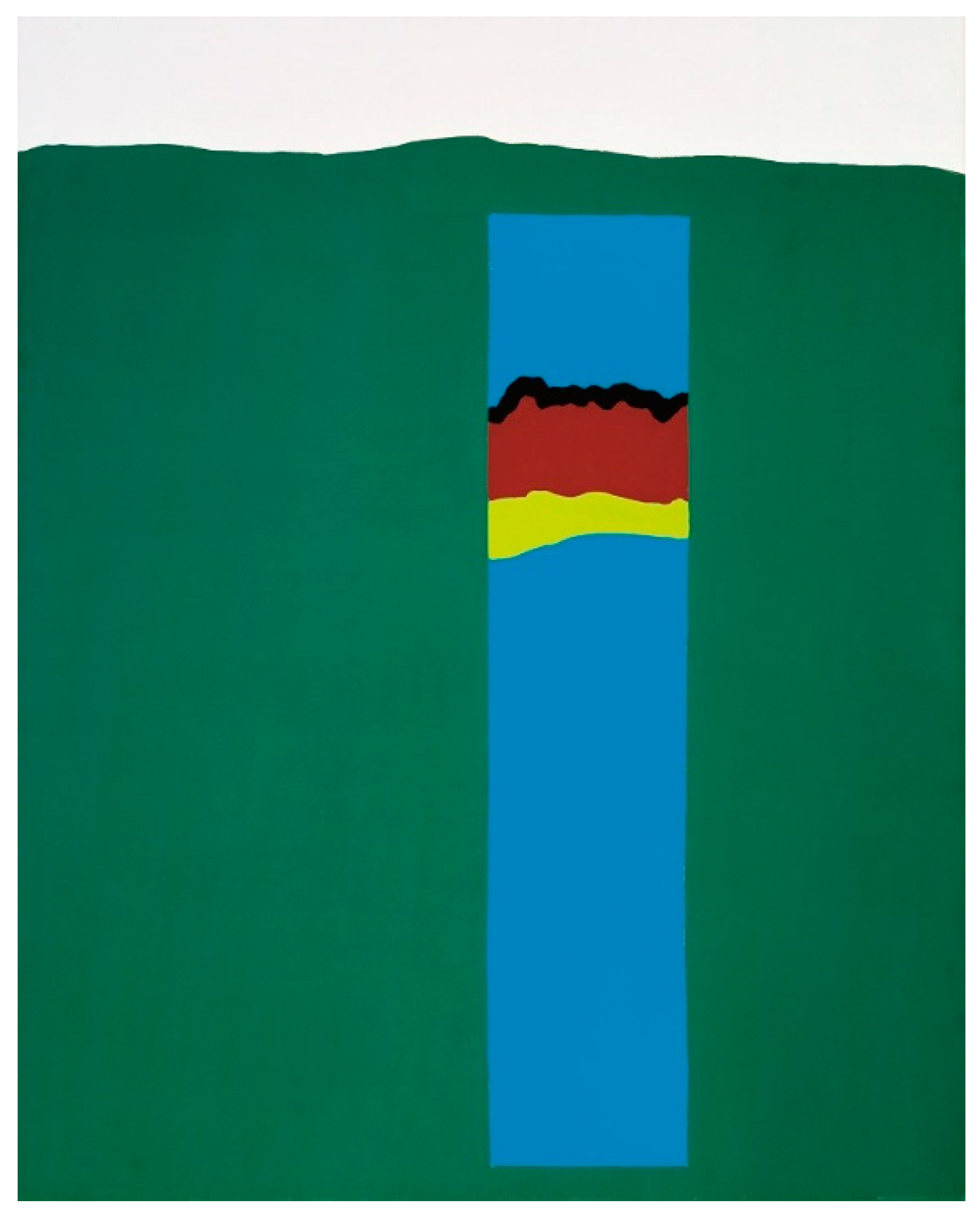

The complex conceptual and spatial relationships that De Keyser raises with his

Linen Boxes and

Slices are developed even further in a series of (two-dimensional) paintings depicting these three-dimensional pictorial constructions (

Figure 13 and

Figure 14). If the canvas had developed into a box or slab, these volumes now sneak back into flat surfaces of new paintings. In a dazzling logic of almost Borgesian or Escheresque proportions, De Keyser, from 1966 onwards, situates his

Linen Boxes and

Slices in landscapes. The configurations in these paintings resonate with the ways De Keyser manipulated his works, shifting or tilting them, placing them on the studio floor or in the garden, as demonstrated by various photographs in De Keyser’s archives. Clearly, some of the photographs of installations of various paintings,

Linnen Dozen and

Slices in a garden, inspired the making of paintings that incorporate fragments from previous works (

Figure 12). This resulted in highly hybrid and fragmented images, such as

Heterogene Concurrentie (1968),

Doos in Landschap (1969),

Summiere Doos in Landschap (1969), or

Slice-Landscape I and

II (1970). In the triptych

Veldoefeningen met Slice (1971–1972), the

Slices, situated in a natural landscape, seem to be the subject of a photographic exercise; it is as if we are looking at the same painting constantly moving closer by means of a zoom lens with changing focal settings. Another variation can be found in the 1967 polyptych

Oefeningen met Eerste Linnen Doos, which shows the

First Linen Box not in a landscape but against the neutral space of a blank canvas (

Figure 15). Looking like a drawing from a construction manual, the four parts constitute a single rectangular painting showing the box together with smaller depictions of its front and side as well as a close-up of the garden hose. Over the years, this four-part painting has been installed in various ways, in a square creating the single image but also as four parts adjacent to one another in a row.

4. 1970s

Both the

Linen Boxes and the

Slices, as well as the paintings depicting them, illustrate De Keyser’s interest in the oscillation between the painting as an image and object. This would also mark his work in the 1970s, a decade in which De Keyser’s art becomes more abstract, more subdued, more ascetic, more tranquil, and more minimalist (

Figure 16 and

Figure 17). De Keyser’s 1970s oeuvre resonates with what in Belgium and the Netherlands was often called “fundamental painting”, in line with the landmark exhibition

Fundamentele Schilderkunst at the Stedelijk Museum Amsterdam in 1975, which included works by Louis Cane, Alan Charlton, Robert Mangold, Brice Marden, Agnes Martin, Gerhard Richter, Robert Ryman, and Marthe Wéry, among others. Like

analytische Malerei in Germany and

nouvelle peinture in France, fundamental painting stands for an artistic practice that investigates the process of painting and its components such as line, structure, color, medium, support, texture, et cetera. A cool, cerebral, abstract, and often geometric kind of art, fundamental painting also favors works in series that meticulously explore minimal differences. These ambitions were also expressed in the exhibition

Concerning Painting, curated by Italian gallerist and critic Roberto Peccolo for various Dutch museums in 1975 and which included paintings by De Keyser, along with works by Winfred Gaul, Jules Olitski, Larry Poons, Dan van Severen, Claude Viallat, Gianfranco Zappettini, and others.

6In line with the art propagated at these influential exhibitions, De Keyser’s 1970s art is characterized by the use of serial structures and a fascination for monochrome painting. He exchanged the bright “poppy” colors of the 1960s for softer and more neutral colors. Frequently, his colors can be considered subdued versions of his earlier palette of yellows, blues, and greens, which now are often applied in thinner layers, sometimes making visible the texture of the canvas. Compared with his works of the late 1960s, the new decade brings more variations in the application of paint. The “cool” style with hard edges of the 1960s is exchanged for a more organic style with more irregular, hesitating, crenellated borders and with more vivid—though restrained—brushwork. In many paintings, the width and orientation of the brush strokes even contribute largely to the painting’s composition. Instead of flattened surfaces, several layers of paint are often visible.

This growing interest in the material conditions of painting continued to draw De Keyser’s interest to the objecthood of his paintings. In the mid-1970s, experiments with unconventional formats that triggered the development of the

Linen Boxes and

Slices continue, albeit in a modified form. Preparatory drawings and installation views that survived in the artist’s archives indicate that De Keyser created at least six additional

Slices or

Slice-like works. One is a strip-like painting, as narrow as a single stroke of paint, which was shown in 1974 at the exhibition

Amédée Cortier en Raoul De Keyser at the Van Abbe Museum in Eindhoven under the title

Slice VIII. This “slice” was later integrated into the composite work

Kant Gampelaere (1973/1976/1985), its triple date indicating that this “installation” developed gradually over the years (

Figure 16). In addition, in the mid-1980s, De Keyser made two similar works entitled

X (1986) and

Untitled (1987), which both look like long single brush strokes that developed into autonomous paintings. Referring to the Gampelaere farm where De Keyser had his studio in the 1960s,

Kant Gampelaere adopted various configurations between 1973 and 1985. A 1977 sketch describes the work as

Gampelaere Hoek (

Gampelaere Corner) and shows four components: two square-format paintings (52 × 52 cm) and two slats, being the aforementioned

Slice VIII as well as a

Slice IX (eventually destroyed), placed on the floor and leaning against the wall. In its final constellation, the work consists of a single 35 × 35 cm painting showing a chalk soccer corner, a slice-like element, and a chalk line (

Slice VIII) turned into a narrow painting, both latter ones leaning against the wall.

In addition, another sketch (1978) shows three

Slices that display, on their vertical edges, a narrow wedge-shape reminiscent of the many wedges in certain paintings such as

Spie (Gusset 1978) and

Wig (Wedge 1978). It is unclear, however, if these works were ever executed. And yet another sketch (dated December 1978) shows “hanging

Slices” that also appear in some installation views. A 1976 show at Gallery Grafiek 50 in Wakken, for instance, shows two

Slices that are displayed as the earlier ones (on the floor, leaning against the wall), but a third one hangs on the wall. Notes in the artist’s archives mention the colors dark green and white for these

Slices, which were, however, destroyed. Furthermore, only one of these

Slices was entirely covered with canvas. Both others were open structures: one of them had its sides covered with painted canvas, the other one its three short, intermediate slats, evoking the artists of the French Supports/Surfaces group and their deconstructions of painting into its constituents–canvas, stretcher, frame, paint, et cetera (

Figure 17).

In their various manifestations (slats or narrow strips, open or closed, hanging or leaning), the Slices demonstrate De Keyser’s unrelenting and almost maniacal fascination for sizes of works. His notebooks are full of calculations and numbers (in most cases, incomprehensible for readers). Under the names of “Richter” and “Baer”, for instance, only formats are mentioned, as if he was almost exclusively interested in the sizes of the works. In addition, throughout the decade, De Keyser prefers small square formats, displaying, like the earlier Slices, their double nature of both object and surface. Moreover, installation views of several exhibitions of the 1970s show that many paintings are displayed conventionally, in a single row at eye level, but that others are arranged in more asymmetric and dynamic configurations, stimulating a spatial interaction between works, evoking the striking constellation of different components in Kant Gampelaere. Moreover, in the 1970s, De Keyser also emphasizes the objecthood of his paintings by using quite thick stretchers, as in Krijthoek 190 (1977) from the S.M.A.K. collection, for instance, or in series such as De Zandvlo (1976), consisting of three eponymous paintings with different stretchers (thick, thin, without). Furthermore, many works of 1977–1978 make their objecthood explicit as they direct the beholder’s focus to the edges of the surface. The frame is doubled, as it were, by a painted frame or a wedge-shaped strip delineating one side of the picture plane.

5. “A Little Bit Minimal”

In short, a sensibility for tensions between abstract imagery and objecthood is sometimes explicitly and sometimes implicitly at stake in most if not all works by De Keyser, who loved juxtaposing paintings in surprising configurations on his studio wall. Many studio photographs in his archives demonstrate that De Keyser experimented with various configurations, proportions, and “mini-exhibitions”. Architect Paul Robbrecht, who designed spaces in which some De Keyser works were exhibited, articulated this strikingly in an essay written in the early 1990s. De Keyser’s paintings, Robbrecht wrote, “seem to be crystallizations, compressed materials, given extra definition by their sometimes limited dimensions. Some of his works are like temporary delineations of endless surfaces or fragments plucked from an endlessly advancing linear structure … There is also something in his paintings which prevents them from becoming windows which break up a wall. Instead you have the feeling that they are leaning against the wall or sliding along it with obstinate indifference.” (

Robbrecht 1991). Nonetheless, practically all works by De Keyser, including his

Linen Boxes and

Slices, do not hypostasize exclusively their material presence. With their fragmentary and evocative references to landscape elements, they oscillate between figuration and abstraction, between illusion and obstinate materiality, between referentiality and autonomy.

A critic following De Keyser closely in those decades, Roland Jooris discussed the

Linen Boxes in several of his art critical writings, but he also referred to these works in his poems, some of them included in the leaflets of De Keyser exhibitions where these works were shown, e.g., in a 1969 show at Gallery Les Contemporains in Brussels and a 1970 show at Gallery Foncke in Ghent. On the one hand, Jooris emphasizes the spatial aspects of the

Linen Boxes, describing them, for instance, as a “chunk of environment.” On the other hand, he presents them as, among other things, consumer items. Objects that are not self-referential “specific objects” but things among other everyday things, the

Linen Boxes are like minimalist sculptures on which you can put everyday items, as Jooris puts it in his 1969 poem “

Een beetje minimal” (“

A little bit minimal”) in which he evokes the image of a Robert Morris cube that serves as a base for a glass of beer (

Jooris 1969).

Giving the self-contained works of American Minimalism a ludic and comical twist, Jooris’s discussion of De Keyser’s

Linen Boxes is characteristic of the reception of late-modernist American art in Belgium. Like De Keyser himself, Jooris absorbed only a general sense of the new American currents without contributing to the debates around notions of “flatness,” “shape” versus “form”, “specific objects”, “objecthood”, and “theatricality” that went hand in hand with the development of Minimal Art (

Colpitt 1990;

Meyer 2000). Although Jooris refers to Clement Greenberg in one of his writings on De Keyser (

Jooris 1972, n.p.), the reception of American modernism was to a large extent disconnected from its art theoretical discourse. Nonetheless, in several of his writings, Jooris demonstrates that De Keyser’s art plays on the very same aspirations and sensibilities that fascinated American artists and their critics. He emphasizes, for instance, De Keyser’s use of all-over structures or the absence of centered compositions by means of cut-outs and seemingly arbitrary framings. Jooris also notices the tension between image and surface, the use of color as a structural component, and the preoccupation with the material aspects of the stretcher and its edges as crucial elements in De Keyser’s paintings. In addition, he interprets the

Linen Boxes as non-hierarchical things among other objects and commodities. However, in contrast with the “specific objects” by Donald Judd and other Minimalist artists who exemplified the transition from painting into three-dimensional “real space” (

Colpitt 1990, pp. 106–12;

Meyer 2000, pp. 23, 27), De Keyser’s

Linen Boxes and

Slices remain somehow three-dimensional paintings rather than transforming into objects activating the surrounding space or offering an experience of “theatricality” as Michael Fried famously described it (

Fried 1967). The “objecthood” of the

Linen Boxes and

Slices is balanced by mimetic references to an (extra-pictorial) reality, their surfaces showing shapes that do not tally with their geometry. Persisting in emphasizing their “pictorial” qualities, the seven

Linen Boxes and nearly a dozen

Slices mark only a short and limited, though a highly important, stage in the artistic career of De Keyser. Like the oeuvres of American painters such as Jo Baer, Robert Mangold, Brice Marden, Agnes Martin, David Novros, and Robert Ryman contradicted the notion that Minimal Art implied the “end of painting” (

Meyer 2000, p. 30;

Levy 2019), De Keyser further developed his painting in a thorough engagement with Minimalism and its preoccupation with objecthood.