Abstract

Evidence for industrial scale production of numerous manufacturing processes has been attested in all phases of occupation at Poggio Civitate (Murlo). A subset of these, tools for the production of textiles and fibers, indicates that textile crafts were manufactured on a large scale as a part of a centralized and organized industry. These industrialized practices occurred within and around the monumental seventh and sixth century BCE complexes which displayed architectural decoration bearing iconographic themes that served to secure the positions of the aristocratic elites. This paper investigates the stamped decoration present on rocchetti and its relationship to the architectural decoration present on the monumental structures of the site. As small moveable objects used by members of the community, rocchetti present an opportunity to investigate the movement of elite images through the non-elite population of a community and their reception of aristocratic ideology presented in monumental structures.

1. Introduction

Excavations at Poggio Civitate (Murlo), an Etruscan settlement 25 km south of the modern city of Siena, have illuminated facets of the daily life of the community between the eighth and sixth centuries BCE. Since excavations began in 1966, significant evidence of industrialized production within the site’s monumental complexes have shed light on the organization of a rural, inward-facing economy in northern Etruria. Of the numerous types of production attested at the site, the processing of fibers and manufacture of textiles indicate that Poggio Civitate had a centralized and organized industry which met the consumption needs of the local community under the aristocratic control of the site’s ruling elite. This paper investigates the decoration present on rocchetti, or spools for thread, and its relationship to the iconography of the architectural decoration present on the monumental structures of the site. As small moveable objects used by a cross-section of the community, rocchetti present an opportunity to investigate the movement of elite iconography through the non-elite population of a community and the reception of aristocratic iconographic messages presented in monumental structures. The types of decoration on the quotidian rocchetti at the site of Poggio Civitate will be discussed and contextualized with its relationship to the images present on monumental architecture and banqueting wares. Further, the objects will be related to the members of the community interacting with them for the production of textiles.

2. Weaving Contexts at Poggio Civitate

The community of Poggio Civitate engaged in three phases of large-scale architectural development. The earliest phase of occupation at the site, dated to the early Orientalizing period and therefore referred to as the Early Phase Orientalizing Complex, preserves at least two buildings of a larger scale than the traces of curvilinear huts dating to the same time period found to the southwest.1 One of them, a large-scale rectilinear residence, Early Phase Orientalizing Complex 4 (EPOC4), appears to be a domestic space which utilized a terracotta tile roof with decorative elements including a horn acroterion and decorative plaques.2 Materials associated with the floor surface of EPOC4 in the interior and front porch space were grains, seeds, and ceramics suggestive of food processing, assembly, and consumption.3 Spindle whorls and rocchetti found on the floor surface are indicative of thread and textile industry, designating that this domestic space doubled as a production space.4

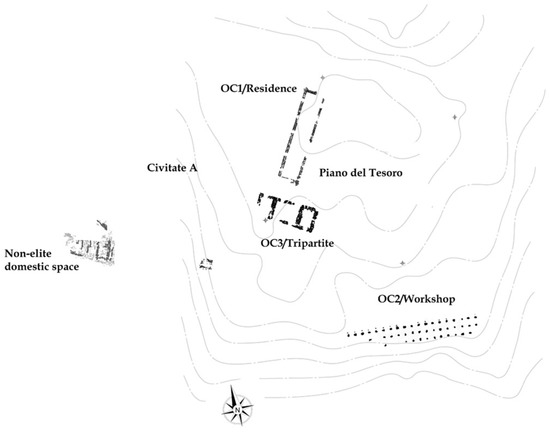

On the highest plateau of the hill, known as the Piano del Tesoro, the following two phases of monumental architectural building occurred. During the second quarter of the seventh century BCE, in the mid-Orientalizing period, a complex of three large scale structures with a common decorative program were constructed around an open area (Figure 1). This Orientalizing Complex, which housed the settlement’s aristocratic rulers and the centralized activities of the community, was composed of an opulent residence (OC1/Residence), a building that is tripartite in structure and possibly acted as the center of religious activity (OC3/Tripartite), and an open-air workshop that housed several forms of manufacturing and the processing of resources (OC2/Workshop).5 The complex provides spaces for the continuation of the domestic and productive activities of the elite inhabitants of the Early Phase Orientalizing Complex with an increased restriction of the visibility of those activities within the internal open area.6

Figure 1.

Site plan of the Orientalizing Phase architectural remains, dating to 675/650–600 BCE (Image: Poggio Civitate Project).

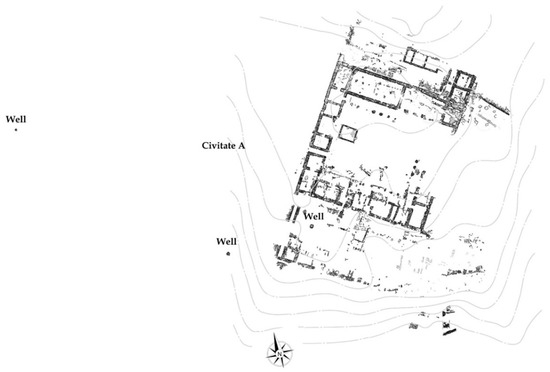

Sometime between the end of the seventh or beginning of the sixth century BCE the Orientalizing Complex was destroyed in a fire that consumed the buildings of the hilltop. The community prepared the area for new construction and combined the functions of the three previous structures into one building with newly introduced defensive works, known as the Archaic Complex (Figure 2).7 The structure was composed of four wings arranged around a partially colonnaded central courtyard. Each wing of the structure measured 60 m in length, placing this structure among the largest known in Central Italy at this time period.

Figure 2.

Site plan of the Archaic Complex architectural remains, dating to 600–535 BCE (Image: Poggio Civitate Project).

It is within this politically charged iconographic environment that the manufacturing activities of the site took place. The spaces associated with production have revealed a multitude of industrial activities occurring within and around the monumental structures simultaneously and indicate that the non-elite members of the community were involved in the production of elite ceramics and roofing decoration. In fact, molds for the production of the roofing elements have been recovered in excavations, such as a mold for the fabrication of antefixes in the form of male human heads from the OC2/Workshop and a mold for the female faces on the Archaic lateral sima from the west of the complex in an area associated with non-elite domestic and production spaces.8 These findspots illustrate that artisans involved in the creation of the monumental decoration for elite spaces, but not part of the elite class themselves, were tasked with creating other ceramic elements such as pottery and textile production objects.

3. The Stamped Rocchetti of Poggio Civitate

Weaving tools, including spindle whorls, rocchetti, and loom weights, were created and used within spaces, such as OC2/Workshop and likely some portion of the Archaic Complex, which possessed monumental decorations that moreover were likely created by the same non-elite artisans creating these decorative roofing elements. Rocchetti are cylindrical objects with flaring, bulbous ends, most often made from ceramic, and associated with the production of fibers and textiles.9 The exact function of rocchetti within the process of textile production in Etruria is not certain. It has been suggested that rocchetti held fibers or yarns during the weaving process or were used as a method of storing and transporting yarn, acting as simple spools.10

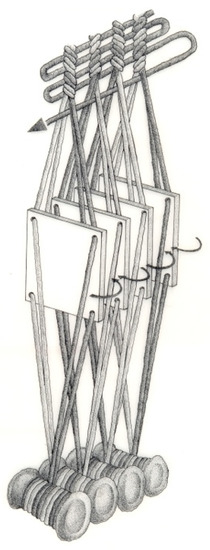

Excavations at Poggio Civitate have revealed numerous examples of rocchetti, totaling 875 identifiable fragments from across the site. Intact examples, numbering fewer than 200, suggest that the majority of the rocchetti at Poggio Civitate weighed less than 50 g. This weight is consistent with their use in tablet weaving, a method that utilizes square tablets which can be rotated to create different sheds (Figure 3).11 Tablet weaving allowed for the creation of elaborate patterns in narrow bands or as decorative borders.12 Rocchetti likely functioned as the weights securing the fibers attached to the tablets.13 The relatively consistent weight of rocchetti at Poggio Civitate not only confirms their use in tablet weaving, but also suggests that textile production was conducted in an organized and centralized manner which enforced consistency. The output from Poggio Civitate’s large-scale textile and thread production activities most likely served not only the hilltop dwellers, but also rural communities surrounding the site.14 This model for a local, even inward- facing textile economy, is consistent with other modes of production at Poggio Civitate.15

Figure 3.

Illustration of tablet weaving utilizing rocchetti as weights (Image: Poggio Civitate Project).

Decoration on rocchetti is frequent and appears on the bulbous ends of the object, as the shaft would be covered while in use.16 The decoration was created utilizing simple shapes, incised or impressed.17 Rolled stamps or the impression of cords used to create geometric patterns become popular as early as the Villanovan period and are present in the archaeological record of Poggio Civitate.18 Stamps similar to those used on Etruscan ceramics are also common throughout Etruria and became popular concurrently with stamped ceramics during the second half of the seventh century BCE.19 The most frequent decoration found on Etruscan rocchetti and ceramic wares is concentric circles, a geometric pattern that is popular throughout Etruria. The long history of concentric circles on ceramics in Etruria suggests that this geometric design is born out of an existing local Italic decorative tradition.20 Concentric circles are also the most frequently preserved stamp present on the rocchetti from Poggio Civitate, representing 46% of the 194 rocchetti preserving identifiable stamped decoration. Other rocchetti preserve stamps with one central image displaying a single figure set in a square or circular impression.21 While stamps preserving vegetal or geometric designs, as well as fantastic animals, are a widespread phenomenon in Etruria, the following discussion reviews the corpus of stamped decoration preserved at Poggio Civitate.22

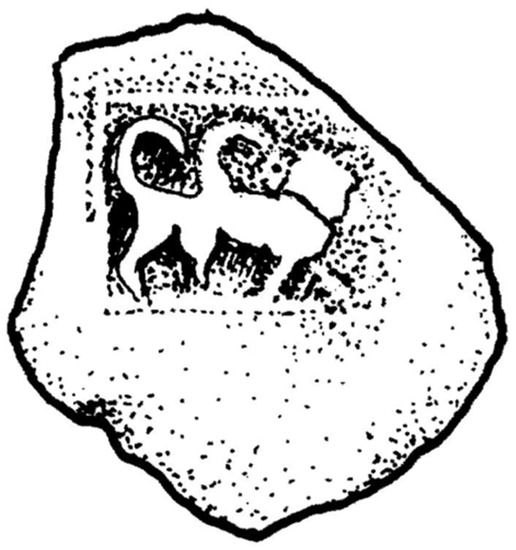

The most popular stamp, comprising 28% of the preserved stamps, is an image of a quadruped standing or striding. The animals displayed on these stamps are challenging to identify due to their stylized nature, the small size of the impressions, and the often uneven application of the stamp on the surface of the clay, however, in some cases it is possible to identify both real and mythological animals among the animal stamps. The real animals depicted in stamped decorations are horses and deer. The horses are highly stylized, with flaring muzzles and wide tails, prancing to the left on curved legs, all four of which are visible. The same style of stamp appears on two fragments of impasto drinking vessels found to the north of the Archaic Complex (Figure 4).23 The deer, depicted in profile, extends its neck high and stretches its antlers over his back; all four legs of the deer are spread wide and visible. Like the horse stamps, the deer stamps appear on both rocchetti and drinking vessels.24 Moreover, the horse and deer iconography also correspond to animal acroteria that decorated the roof of the Archaic Complex.

Figure 4.

PC19710594 (left) and PC19680113 (right) detailing the use of the same horse stamp on an Orientalizing drinking vessel and a rocchetto head, ca. 675/650–600 BCE.

Examples of winged felines, most likely sphinxes, are also found among the stamped decoration of rocchetti (Figure 5).25 Similar to the real animals, the sphinxes are depicted striding to the right in profile with all legs visible. The sphinx has a human head and a curved tail with a single wing extending from the back of the sphinx, similar in style to the volute-like wings of the sphinx statue which decorated the roof of the Archaic Complex.26 Other winged mythological animals are evident in the preserved stamps, such as a possible chimaera, but are difficult to identify with certainty.

Figure 5.

Sphinx stamp on an impasto rocchetto, ca. 675/650–535 BCE (Image: Poggio Civitate Project).

A further 16% of the stamped decoration on rocchetti are lotus palmettes or curving vegetal volutes (Figure 6). This category of stamps is highly variable, with most examples preserving leaves curling outward from a central design. One example, preserved on two rocchetti, is defined by two large petals of a palmette with three petals branching from a central stalk.27 Three additional petals decorate the base. Other examples display crossed, curving volutes placed over a central stalk, or a singular line ending in two inward curling volutes around a central vegetal decoration.28 Stylistically, these vegetal stamps fit comfortably within the iconography of the monumental decoration present in both phases of the site and often accompany other elements of eastern-inspired decoration, such as the images of the fertility deity and the mythological animals.

Figure 6.

Stamped crossed volute decoration on an impasto rocchetto, ca. 675/650–535 BCE (Image: Poggio Civitate Project).

Similar to the larger category of palmettes and volutes, eight examples preserve vegetal rosettes stamped multiple times on the decorated ends of rocchetti.29 The rosettes vary in style between a composition of radiating lines around a central circle and a design composed of a circle split into eight petals. Where the rosette stamps are impressed more than once on the head of the rocchetti, one is placed centrally and the others form a circle around it, following the diameter of the head’s edge. Rosettes frequently accompany other elements of eastern iconography such as lotus palmettes and volutes, and were incorporated on the lateral sima of the Archaic Complex alongside female and feline heads.

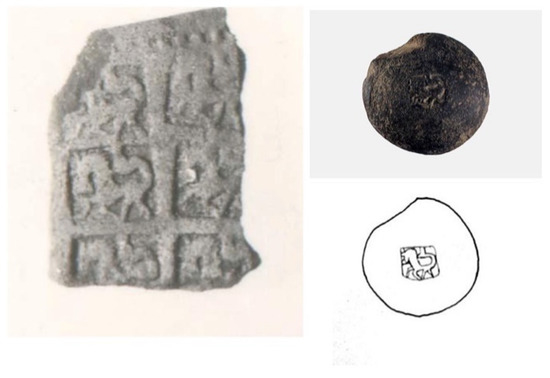

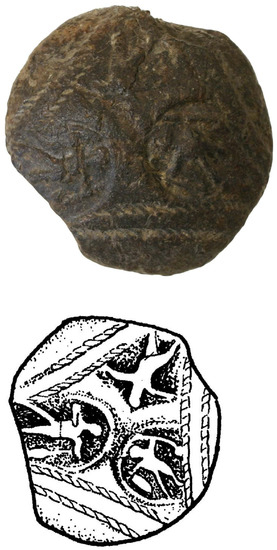

One exceptional example includes three identical stamps of an armed warrior surrounded by a double triangle of rolled decoration on the preserved end of a sole impasto rocchetto (Figure 7).30 The armed warrior is in relief, turning to the left, carrying a shield on his left arm, and holding a weapon out with his right arm. The weapon is difficult to distinguish, but is likely a club or a short spear. The image is the only example found at Poggio Civitate of a human figure on the decoration of a rocchetto, but is similar in design to a stamp that repeats six times on a fine impasto vessel fragment in which an armed warrior viewed frontally holds objects in both hands.31 The objects are curved and may represent a bow and/or a shield. The similarity of the two stamps, each only preserved in one example of each object class, suggests a shared iconographic environment between the two objects. When the rocchetto was in use for the production of textiles, the warrior rocchetto was likely used in combination with other stamped rocchetti, surrounding the warrior with real or mythological animals, vegetal motifs, and palmettes, recalling the images of the fertility deity that appeared on both phases of the monumental decoration and the helmeted warrior appearing with the fertility deity on the kantharoi.

Figure 7.

Impasto rocchetto head and drawing illustrating a repeating warrior stamp, ca. 675/650–535 BCE (Image: Poggio Civitate Project).

While stamps with concentric circles are derived from a longstanding local Italic tradition, the stamps that echo motifs present on the monumental decoration of the site reflect new traditions, influenced by the contemporary Mediterranean koine, implemented by the local elite to communicate their unique political messages and concerns. The elite of Poggio Civitate introduced this iconography through the decoration on monumental architecture and banqueting wares to communicate and reinforce their aristocratic position, solidifying their authority over the non-elite members of the community.

4. Elite Iconography in Monumental Architecture and Banqueting Wares

The three structures of the Orientalizing Complex had identical roofing systems and a unified decorative program. Lateral sima bearing feline-faced waterspouts directed water off the roof (Figure 8). A female face antefix covered the exposed end of the terminal cover tiles.32 Along the ridgepole of the roof were acroteria composed of triangular lotuses and palmettes with curving volutes.33 OC1/Residence had an additional cut-out acroterion, now fragmentary, potentially depicting a feline; other structures in the complex also preserved evidence of fragmentary cut-out animal statuary.34 An additional acroterion found near the OC1/Residence was composed of two volutes which terminate in feline heads that bite a human male figure standing in the center. This composition suggests the Master of Animals motif, consistent with other Etruscan depictions of a male figure attacked by the animals that accompany the female fertility deity, Potnia Theron, or the ‘Mistress of Animals’.35 The ‘Mistress of the Animals’ is also recalled in other elements of the Orientalizing Complex’s decorative program including the lotuses, stylized volutes, and, most obviously, the repeating female and feline faces of the eaves. The representation of this fertility goddess at Poggio Civitate reflects her popularity in Etruria, where she first appears in elite burial contexts on imported luxury goods in the 7th century BCE.36 The adoption of her iconography into elite representation reflects the political concerns of the familial members of the aristocratic governing body which utilize the symbolic fertility and sexuality of the ‘Mistress of Animals’ to propagate their familial line.37

Figure 8.

Orientalizing Complex Roofing Elements dating to 675/650–600 BCE, depicting alternating female heads and feline waterspouts as reconstructed in the Antiquarium di Poggio Civitate Museo Archeologico (Image: Poggio Civitate Project).

A similar iconographic message was included on objects found within and to the north-east of the OC1/Residence structure of the complex. A large banqueting service, including bronze cauldrons and drinking vessels with decorative images echoing those on the monumental architecture, was recovered.38 The drinking vessels included imported cups from eastern Greece and a larger body of locally made vessels that could support a dining service for hundreds of banquet attendees. The locally made vessels included impasto wares most likely used for the non-elite members of the community, alongside fine wares of kantharoi and kyathoi for entertaining the community’s elites, bearing depictions of the ‘Mistress of Animals’. The fertility divinity grasps or is flanked by pairs of animal familiars including birds and felines, or holds two long braids pulled forward over her shoulder.

An attachable finial fragment that would have been attached to cups of this style was recovered in the form of a lotus palmette, an element of eastern iconography that frequently accompanies images of the fertility deity.39 Lotus palmettes are included on similar bucchero cups from examples from outside of Poggio Civitate with some examples positioned over the genitalia of the figure, creating a strong association between lotus palmettes and the fertility deity.40 It is therefore possible that the representation of a lotus palmette may have been understood as a reference to the fertility divinity in other contexts, invoking references to her fertility and fecundity.41 Two examples also display the goddess in combination with a decorative finial representing a helmeted warrior, linking her through this male companion with martial prowess (Figure 9).42 The incorporation of the images of the female fertility deity controlling animals into both the monumental decoration and these small-scale materials reflects the concerns of the elite community members for expressing their aristocratic authority and identity in widespread media.

Figure 9.

Decorative finial fragment with fertility deity and warrior dating to the Orientalizing Phase, 675/650–600 BCE (Image: Poggio Civitate Project).

The decorative program of the structure echoes the message of aristocratic authority from the previous phases, but was re-imagined to suit a more advanced roofing system technique.43 Gorgon head antefixes were situated at the ends of the terminal cover tiles along the exterior of the building’s roof. A larger decorative plaque featuring a similar gorgon face was affixed to the end of the ridgepole beam.44 The representation of the Gorgon’s iconography on the roof serves an apotropaic function, protecting the complex from the ‘evil eye’.45 The interior of the building utilized a lateral sima similar to that found on the Orientalizing Complex, featuring feline waterspouts flanked by rosettes and a female head applique, again a ‘Mistress of Animals’ motif.

Acroteria featuring enthroned human figures, animals, and mythological creatures were attached to the apex of the Archaic building’s roof (Figure 10).46 A minimum of 14 human figures, male and female, were placed along the roof, seated on four-legged stools, and with hands posed to hold attributes that no longer survive.47 The figures preserve trace elements of paint indicating that textile patterns originally decorated the clothing of the figures. At least seven of the male figures wore distinctive peaked hats, earning them the moniker of the “cowboy statues”. There were at least two other male types, one that wore a helmet and one with no headdress. The animal acroteria included horses, boars, rams, and lions, alongside mythological animals including sphinxes, hippocamps, griffons, and a possible centaur.48 The attachment points of the statues to the ridgepole tiles suggest that the human figures were positioned facing out from the roof, while the animal statues were faced laterally, so that their full profiles would have been visible. The position occupied by the statues on the roof is difficult to definitely determine due to the later destruction of the building. It is possible that the animal figures flanked the human ones along the roof line connecting with the presentation of the Master of Animals flanked by felines along the building’s lateral sima.

Figure 10.

Reconstruction of the Archaic Complex, 600–535 BCE, depicting the possible arrangement of acroteria, as proposed by Evan Baston (Image: Poggio Civitate Project).

Four types of frieze plaques adorned the building and depicted images of elite activities: a competitive horse race, a banquet scene, a procession of seated figures on a two wheeled cart, and a series of seated and standing figures holding attributes of religious and social authority. While a variety of interpretations have been presented for the scenes on the frieze plaques, the current excavators have proposed that the plaques can be read as a sequential scene of an elite marriage.49 A bride arrives in the procession scene along with her attendants, who carry with them the elements of textile production to set up in her new household, feasts at a celebration of the marriage, witnesses a public spectacle to mark the event, the horserace, and takes her place amongst her new family, who bear formal attributes representing their authority, on the seated and standing figures plaque.

The frieze plaques present not only representations of Etruscan textiles but also reference their manufacture. The banquet frieze plaque presents couples reclining on couches draped with long textiles.50 Ceramic and butchered bone found throughout both the Orientalizing and Archaic phases evidence that banqueting was practiced at Poggio Civitate51 and textiles, as represented on the plaque, would have been an important element of these contexts in the form of garments, tents, and coverings. Further, the textile production objects carried by attendants following the two-wheeled cart in the procession frieze plaque demonstrate the social importance of textile manufacture among elites (Figure 11). The first attendant balances a container on her head that can be interpreted as a cista, which frequently held cleaned and carded wool to be spun into fibers or yarn.52 The attendant on the right carries an object with two staked, spoked elements, possibly representing a yarn swift, an object which aids in the winding of yarn or the stringing of a loom.53 The presence of textiles and objects integral to textile production on the decoration of this monumental complex speaks to the central importance that the large-scale production of textiles held in the development and reinforcement not of only elite identity but also of community practices.54

Figure 11.

Illustrated reconstruction of the terracotta Procession frieze plaque type that decorated the Archaic Complex, 600–535 BCE (Image: Poggio Civitate Project).

The destruction and erosion of the Archaic Complex has obscured the interior spaces, making it difficult to determine what role the building served. While numerous functions have been suggested, it now seems likely, as stated above, that the Archaic Complex combined the residential, industrial, and production functions of the three separate structures of the Orientalizing Complex and additionally provided the community with a defensible semi-public gathering space.55 As a whole, the decorative program featuring ancestor figures (acroteria and frieze plaques), the Mistress of the Animals (sima), and gorgoneia (antefixes, plaques) expressed the power of the aristocratic ruling family through its connection to past generations, future procreation, and apotropaically afforded protection to assure the secure passage of power to subsequent generations. The size and elaborate decorative program of the monumental Archaic Complex afforded the members of the elite ruling classes a visible embodiment of their control over local resources and other social classes.56 Furthermore, these components collectively broadcasted messages of elite identity to other social classes on the hill and in the surrounding satellite communities that fell under the aristocratic control of Poggio Civitate.

The cohesive iconography of the monumental architecture, banquet wares, and rocchetti dispersed across the site suggests that the non-elite craftsmen tasked with creating the monumental decoration were utilizing similar iconographic messages in the creation of moveable objects used for the community activities of banqueting and textile production. That iconography echoing elite messages appears on moveable objects created and used by the non-elites of Poggio Civitate, illustrates their reception and replication of the ideology associated with the aristocratic iconographic tradition.

5. The Role of the Artisans of Poggio Civitate in the Transfer of Elite Iconography to Non-Elite Textile Tools

Non-elite artisans involved in the creation of products utilized for elite activities, such as monumental decoration and ceramic banqueting wares, were also tasked with producing textile tools and their decoration. A locally produced fenestrated finial fragment found on the floor surface of the OC2/Workshop revealed fragments of terracotta within the center of the finial fragment (Figure 12).57 The small fragments of terracotta preserved shallow impressions with a sunburst design, indicating that the fenestrations were created by utilizing a stamping tool normally used to place decorative designs on fine wares, impasto wares, and textile production artifacts as a punch to create the fenestrations. The object testifies that craftsmen were likely producing varieties of ceramic wares within the same space and had access to the molds and tools used to add decorative elements, and therefore possessed a role in the creation of the iconography itself.

Figure 12.

PC19920024, an Orientalizing fenestrated impasto vessel fragment and associated fragments found within the finial preserving stamped designs, 675/650–600 BCE (Image: Poggio Civitate Project).

Mapping the concentrations, mentioned above, of the recovery locations of spindle whorls and loom weights found to date at the site, completed by Cutler et al., has shown that distinct areas across the site were utilized for textile production. The objects are densely concentrated in the area north of the OC2/Workshop, suggesting that a fiber-based workshop functioned at an industrial scale alongside the ceramic, metal, glass, ivory, and animal processing activities taking place within the OC2/Workshop structure.58 The same distribution pattern is revealed when spindle whorls with a diameter of 1.5 cm or greater are mapped across the site and concentrate in OC2/Workshop. When, however, spindle whorls with a diameter of 1.5 cm or less are mapped they concentrate within the area of OC1/Residence.59 Whorls of a smaller diameter are better suited for the production of finer threads. This suggests that while thread production was occurring across the site, utilitarian thread was produced by non-elite laborers in the workshop while finer thread was produced within the elite residence, as reflected by the status of these craftworkers emulating the visuals known from the bronze tintinnabulum from the Arsenale Militare necropolis at Bologna, and the Verucchio throne. 60 An additional cluster of textile production objects was recovered in the northern corner of the Archaic Complex. This group of spindle whorls may have been in storage and utilized for periodic production of community textiles, such as used at banquets or religious events.61 This evidence suggests that the elites controlled access to stored production objects. It is tantalizing to imagine that in this period too it was the elites, likely women as demonstrated by grave goods and visual representations throughout Etruria, resident in the Archaic Complex who produced finer quality textiles and mediated the access of non-elites to these stored tools.

The women responsible for the creation of textiles at Poggio Civitate are frequently not visible in the archaeological record, but a single impasto rocchetto from the site may provide a glimpse in the form of an inscription on the shaft of the object. Four letters form the word RIXA, an Etruscan word not elsewhere attested (Figure 13).62 In contrast to the stamps, the inscription would not be visible while the rocchetto was in use. The linguistic similarity of the word to feminine personal names suggests that this rocchetto preserves the name of an Etruscan woman, potentially the woman who used the tool.63 While it is not possible to know the extent that Etruscan women possessed the functional literacy to inscribe their name onto the object, it is inviting to imagine that the rocchetto was a personalized object of an Etruscan woman producing textiles for consumption by the community.

Figure 13.

Orientalizing impasto rocchetto fragment with RIXA inscription, 675/650–600 BCE (Image: Poggio Civitate Project).

In non-elite spaces of production, the use of rocchetti with images that echo those displayed by the monumental architecture indicates that non-elite textile producers sought to replicate the iconography selected by elites into the community, perhaps trying to identify themselves with elite weaving women. This replication is archaeologically visible within a series of poorly preserved domestic structures found to the south and west of the Piano del Tesoro. These structures preserve evidence of domestic production contemporary with at least EPOC4 and the Orientalizing Complex.64 The significantly thinner walls and smaller interior areas of the structures distinguishes them from elite counterparts.65 The objects found within the structures evidence daily domestic activities such as quotidian ceramic production, meat processing, and textile production.66

Fifteen spindle whorls and thirty-one rocchetti were recovered from within these light-frame domestic structures, along with one loom weight.67 The textile production objects indicate the production of coarse thread and textiles; no lighter spindle whorls consistent with those recovered in the OC1/Residence were recovered.68 Four rocchetti preserve stamped decoration, two decorated with patterns of concentric circles, one with a curving volute vegetal pattern, and one with a striding quadruped.69 The presence of these artifacts indicates the incorporation of elite iconography into non-elite contexts, illustrating the spread of such images throughout the community. Furthermore, these decorations, though present here in the singular vegetal rocchetto example, represents a broader pattern at the site of elite visual themes, such as those displayed by the monumental architecture, circulating throughout Poggio Civitate’s female population by means of moveable textile production objects.

As objects for textile production have been found in all domestic and public areas of Poggio Civitate, children would have been exposed to the production processes from a young age. As they accompanied caregivers working with family or community members, children learned the technical production processes through watching, interacting, and imitating those at work, both men and women.70 Limited, direct evidence of this claim is represented by a conical impasto spindle whorl recovered within an Archaic light-framed, non-elite domestic structure located to the southwest of the Archaic complex.71 The spindle whorl is fluted, which aided in securing the yarn to the whorl during the act of spinning. The wider, perpendicular convex face preserves a series of impressions encircling the central hole that appear to have been made by pressing a fingernail into this surface before firing (Figure 14). The small size of the impressions suggests that a child may have been responsible for creating the decoration on the surface of the whorl and thus was in attendance for at least a portion of the production process of the object.

Figure 14.

Archaic impasto Spindle whorl with possible fingernail impressions, 600–535 BCE (Image: Poggio Civitate Project).

While the spindle whorl is not definitive, textile production objects appear as grave goods for children in Italy as young as two to three years old, indicating that children began to learn the specialized skills necessary to produce fibers from a young age.72 Technical education most likely began with age-appropriate tasks such as spinning or tablet weaving before later learning more physically demanding tasks such as working a warp weighted loom. Exposure to women knowledgeable about the process and the physical body movements was fundamental to learning the techniques of textile working and facilitated a range of social interactions not only between adult artisans and children but also between artisans.73

The social interactions occurring around the production of textiles most likely facilitated elements of social and political education during long sessions of textile production. Mythological and ethnographic evidence point to the recitation of mythological stories during weaving sessions as a possible form of education, entertainment, and a memorization technique for the patterning and physical moments of textile production.74 A material expression of this education at Poggio Civitate are the rocchetti and their stamped decoration, which were likely encountered by children tasked at a young age with the organizing of threads and small tablet weaves. As children learned how to use the tools necessary to create textiles, they very likely learned the meaning of the decoration they possessed.

It is inviting to imagine that the iconography of the rocchetti and their echoing of the aristocratic messages presented on the monumental architecture of the site played an important role in the local political education for the members of the community of all social classes and age groups. The spread of motifs through elite and non-elite contexts reinforced the identity of the elite members of the community but also reinforced the social formation resulting from the established aristocracy. The non-elite employment of elite iconography on small-scale, moveable, and quotidian objects asserted their inclusion in the community and their relationship to the monumental spaces that displayed community values, such as the emphasis on fertility and proliferation.

6. Conclusions

The archaeological record at Poggio Civitate indicates that industrialized production was occurring within spaces controlled by the aristocratic elite. The monumental complexes that housed this production displayed iconographic themes linking the aristocracy to images of a fertility deity, attesting the authority of aristocratic ancestors, and securing their aristocratic position in the future. Decorated objects such as drinking vessels and stamped rocchetti echoed the iconographic environment established by the elites and circulated those images within the non-elite community. Though the elites controlled the iconography of their buildings and banqueting wares, the decoration of textile production tools was particularly driven by the artisans and the women of the community who educated future non-elite generations. The social interactions focused around the use of rocchetti provided the technical education needed for learning the specialized skills to produce textiles but also provided a venue for the social and political education of young community members. The iconographic link between the decoration and the monumental narratives served to reinforce the social order of the community and the hierarchical identities of its members. The decoration on rocchetti allow a glimpse into the economic and social importance of textile production at Poggio Civitate and points to the role of women in circulating images relating to narratives displayed on monumental architecture.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

Notes

| 1 | All cataloged objects and excavation documentation are publicly available on the archaeological database OpenContext (https://opencontext.org, accessed on 3 January 2022). All objects are referred to by an accession number composed of the prefix “PC” for objects found at Poggio Civitate followed by the year of excavation and a four-digit number recording the sequential order of cataloged objects. All material evidence is referred to by this catalog number throughout the following paper. |

| 2 | PC20150043, PC20150049, and PC20150066. |

| 3 | (Tuck 2017, p. 232). |

| 4 | (Tuck 2017, p. 232; 2021, pp. 16–18; Tuck et al. 2016, pp. 109–34). |

| 5 | (Nielsen and Tuck 2001). |

| 6 | For a discussion of the development of elite domestic architecture at the site see (Tuck 2017). |

| 7 | (Nielsen and Phillips 1977, p. 100; Nielsen 1994). |

| 8 | PC19850033 and PC19700129 |

| 9 | (Gleba 2008, p. 140). |

| 10 | (Gleba 2008, p. 140). |

| 11 | (Gleba 1999, 2000, 2008, p. 141). |

| 12 | (Gleba 2008, pp. 138, 140). |

| 13 | (Dohan 1942) first suggested that rocchetti could be used as weights. (Ræder Knudsen 2002) addressed their potential use in the creation of the decorative borders on the surviving textiles at Verucchio. Gleba has argued this use for the evidence from Poggio Civitate in (Gleba 2000, p. 79) and (Cutler et al. 2020) suggests that the rocchetti at Poggio Civitate are indicative of a tablet woven textile workshop. |

| 14 | (Tuck et al. 2009; Tuck et al. 2016). |

| 15 | (Nielsen 1984; Phillips 1994; Tuck 2014). |

| 16 | One notable exception is PC20090211, discussed below, a rocchetto with an epigraphic inscription placed on the shaft of the object, most likely a personal name. (Tuck and Wallace 2011). |

| 17 | (Gleba 2008, p. 148). |

| 18 | (Gleba 2008, p. 147). For example: PC19670541. |

| 19 | (Gleba 2008, p. 148). There is evidence for the same stamp used on more than one type of ceramic objects. Such as PC19700171 and PC19720008, a fragment of an impasto vessel and an impasto rocchetti head that each preserve a stamp of a quadruped facing right. (Phillips 1994, p. 31). |

| 20 | (Gleba 2008, p. 148). |

| 21 | (Phillips 1994) presents a selection of the stamps on ceramic wares at Poggio Civitate as evidence for the local production of ceramic at Poggio Civitate. |

| 22 | For extensive bibliography on stamped decoration in Etruria see (Gleba 2008, p. 148). |

| 23 | The term “impasto” throughout this paper refers to objects that are composed of locally produced clay. PC19710594, PC19720285, and PC19680113. |

| 24 | PC19690093, PC19710238. |

| 25 | PC19690090. |

| 26 | (Fullerton 1982). |

| 27 | PC19700207; PC19710084; (Phillips 1994, pp. 33–34). |

| 28 | PC20180009. |

| 29 | PC19710486, PC19760097, PC19720075, PC19840045, PC19870065, PC19930035, PC19930093, PC19960039. |

| 30 | PC19690022. (Phillips 1970, p. 22; 1994, p. 33). |

| 31 | (Phillips 1994, p. 33). |

| 32 | (Nielsen 1987; Winter 2009; Wikander and Tobin 2017). PC19850083. |

| 33 | (Rystedt 1983). |

| 34 | PC19680475. |

| 35 | (Winter 2009, pp. 52–54; Rystedt 1983). |

| 36 | (Damgaard Anderson 1993). |

| 37 | (Tuck 2006). |

| 38 | (Glennie et al. 2021; Tuck 2021, p. 89–91) |

| 39 | (Valentini 1969, pp. 421–22). |

| 40 | Such as on a bucchero kyathos handle from Chiusi that positions a lotus palmette over the female figure’s genitalia. (Tuck 2006, p. 133; Valentini 1969, pp. 423–24). |

| 41 | (Tuck 2006, p. 132). |

| 42 | PC19720279, PC19720320. (Glennie et al. 2021, p. 46; Tuck et al. 2016). |

| 43 | (Tuck and Glennie 2020). |

| 44 | (Neils 1976). |

| 45 | (Glennie et al. 2021, p. 48; Howe 1954). |

| 46 | (Newland 1994) provides a comprehensive catalog of the sculptural fragments. |

| 47 | (Edlund-Berry 1993, p. 178). Edlund-Berry calculates this number based on the number of hands and feet recovered. (O’Donoghue 2013) establishes the minimum number on the roof to be 7 based on the number of identifiable hat peaks. |

| 48 | (Newland 1994, pp. 12–27). |

| 49 | (Tuck 2021, pp. 120–25). |

| 50 | (Small 1971; Cutler et al. 2020, p. 26). |

| 51 | (Kansa and MacKinnon 2014). |

| 52 | (Tuck 2021, p. 121) contra (Gantz 1974, p. 6). Gantz suggests that this item is a folded campstool similar to those used by the figures on the seated figures plaque. |

| 53 | (de Grummond 2008, p. 126; Tuck 2021, p. 121). |

| 54 | (Gleba 2008, pp. 169–71). |

| 55 | (Phillips 1993, pp. 79–83) suggests that the Archaic Complex was a sanctuary or a meeting hall for the northern Etruscan league. (Cristofani 1975) suggests that the complex served as a palazzo. (Turfa and Steinmayer 2002) emphasize the defensive works introduced to the complex and interpret the structure as a fortress. (de Grummond 1997, pp. 36–38) posits that the complex served as an open forum for the community. |

| 56 | (O’Donoghue 2013, p. 280). |

| 57 | PC19920024. |

| 58 | (Cutler et al. 2020, p. 20). |

| 59 | (Tuck 2021, p. 152). |

| 60 | (Morigi Govi 1971; Gleba 2016, p. 238; Meyers 2016, p. 314; von Eles 2002). |

| 61 | (Cutler et al. 2020, p. 19; Tuck 2021). |

| 62 | PC20090211. |

| 63 | (Tuck and Wallace 2011). |

| 64 | (Tuck 2021, pp. 77–78). |

| 65 | (Tuck 2021, p. 77). |

| 66 | (Tuck 2021, p. 77). |

| 67 | (Tuck et al. 2013, pp. 295–96). |

| 68 | (Tuck 2021, p. 79; Tuck et al. 2013, p. 296). |

| 69 | Striding quadruped: PC20130051. Vegetal decoration: PC20120132. Two rocchetti preserve concentric circle stamps: PC 20120129 and PC20130093. |

| 70 | (Foxhall 2012, p. 195). |

| 71 | PC20190069. |

| 72 | (Lipkin 2013, p. 23; Foxhall 2012, pp. 197–99). |

| 73 | (Foxhall 2012, p. 197). |

| 74 | (Tuck 2006, p. 543) on singing as a memorization technique. For women singing while working in Greek and Roman sources see (Pantelia 1993; Tuck 2009; Heath 2011). |

References

- Cristofani, Mauro. 1975. Considerazioni su Poggio Civitate (Murlo, Siena). Prospettiva 1: 9–17. [Google Scholar]

- Cutler, Joanne, Bela Dimova, and Margarita Gleba. 2020. Tools for Textiles: Textile Production at the Etruscan Settlement of Poggio Civitate, Murlo in the Seventh and Sixth Centuries BC. Papers of the British School at Rome 88: 1–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Damgaard Andersen, Helle. 1993. The Etruscan Ancestral Cult: Its Origin and Development and the Importance of Anthropomorphization. Rome: L’Erma di Bretschneider. [Google Scholar]

- de Grummond, Nancy Thomson. 1997. Poggio Civitate: A Turning Point. Etruscan Studies 4: 23–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Grummond, Nancy Thomson. 2008. Etruscan Women. In From the Temple and the Tomb: Etruscan Treasures from Tuscany. Edited by Patrick Gregory Warden. Dallas: Meadows Museum, pp. 115–41. [Google Scholar]

- Dohan, Edith Hall. 1942. Italic Tombs in the University Museum. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press. [Google Scholar]

- Edlund-Berry, Ingrid. 1993. The Murlo Cowboy: Problems of Reconstruction and Interpretation. In Deliciae Fictiles: Proceedings of the First International Conference on Central Italic Architectural Terracottas at the Swedish Institute in Rome, Italy, 10–12 December 1990. Edited by Eva Rystedt, Charlotte Wikander and Örjan Wikander. Stockholm: Svenska Institutet i Rom, pp. 117–21. [Google Scholar]

- Foxhall, Lin. 2012. Family Time: Temporality, Gender and Materiality in Ancient Greece. In Greek Notions of the Past in the Archaic Period and Classical Eras. Edited by John Marincola, Lloyd Llewellyn-Jones and Calum Maciver. Edinburgh Leventis Studies 6. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, pp. 183–206. [Google Scholar]

- Fullerton, Mark. 1982. The Terracotta Sphinx Akroteria from Poggio Civitate (Murlo). Mitteilungen des deutschen archäologischen Instituts, Römische Abteilung 89: 1–26. [Google Scholar]

- Gantz, Timothy Nolan. 1974. The Procession Frieze from the Etruscan Sanctuary at Poggio Civitate. Mitteilungen des Deutschen Archäologischen Instituts, Römische Abteilung 81: 1–14. [Google Scholar]

- Gleba, Margarita. 1999. Textile Production in Etruria: The Case of Poggio Civitate (Murlo). Master’s thesis, Bryn Mawr College, Bryn Mawr, PA, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Gleba, Margarita. 2000. Weaving at Poggio Civitate (Murlo). Etruscan Studies 7: 105–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gleba, Margarita. 2008. Textile Production in Pre-Roman Italy. Ancient Textiles Series; Oxford: Oxbow Books, vol. 4. [Google Scholar]

- Gleba, Margarita. 2016. Etruscan Textiles in Context. In A Companion to the Etruscans. Edited by Sinclair Bell and Alexandra Ann Carpino. Blackwell Companions to the Ancient World. Hoboken: John Wiley & Sons, Incorporated, vol. 143, pp. 237–46. [Google Scholar]

- Glennie, Ann, Katherine Kreindler, and Anthony Tuck. 2021. Drunk with Power: Wine Drinking Vessels, Inebriation, Sexuality, and Politics at Poggio Civitate (Murlo). Studi Etruschi 83: 35–68. [Google Scholar]

- Heath, John. 2011. Women’s Work: Female Transmission of Mythical Narrative. Transactions of the American Philological Association 141: 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howe, Thalia Phillies. 1954. The origin and function of the Gorgon-head. American Journal of Archæology 58: 209–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kansa, Sarah Whitcher, and Michael MacKinnon. 2014. Etruscan Economics: Forty-Five Years of Faunal Remains from Poggio Civitate. Etruscan Studies 17: 63–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lipkin, Sanna. 2013. Textile Making in Central Tyrrhenian Italy-Questions Related to Age, Rank, and Status. In Making Textiles in Pre-Roman and Roman Times: People, Places, Identities. Edited by Margarita Gleba and Judit Pásztókai-Szeöke. Ancient Textiles Series; Oxford: Oxbow Books, vol. 13, pp. 19–29. [Google Scholar]

- Meyers, Gretchen. 2016. Tanaquil: The Conception and Construction of an Etruscan Matron. In A companion to the Etruscans. Edited by Sinclair Bell and Alexandra Ann Carpino. Blackwell Companions to the Ancient World. Ancient History. Chichester: Wiley/Blackwell. [Google Scholar]

- Morigi Govi, Cristiana. 1971. Il tintinnabulo della “Tomba degli ori” dall’arsenale militare di Bologna. ArchCl 23: 51–54. [Google Scholar]

- Neils, Jennifer. 1976. The Terracotta Gorgoneia of Poggio Civitate (Murlo). Mitteilungen des Deutschen Archäologischen Instituts, Römische Abteilung 83: 1–29. [Google Scholar]

- Newland, Danielle. 1994. The Akroterial Sculpture and Architectural Terracottas from the Upper Building at Murlo. Ph.D. dissertation, Bryn Mawr College, Bryn Mawr, PA, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Nielsen, Erik. 1984. Speculations on an Ivory Workshop of the Orientalizing Period. In Crossroads of the Mediterranean: Papers Delivered at the International Conference on the Archaeology of Early Italy, Haffenreffer Museum Brown University, 8–10 May 1981. Edited by Tony Hackens, Nancy Holloway and Robert Ross Holloway. Providence: Brown University Press, pp. 333–48. [Google Scholar]

- Nielsen, Erik. 1987. Some Preliminary Thoughts on Old and New Terracottas. Opuscula Romana 15: 91–119. [Google Scholar]

- Nielsen, Erik. 1994. Interpreting the Lateral Sima at Poggio Civitate. Madison: The University of Wisconsin Press. [Google Scholar]

- Nielsen, Erik, and Kyle Meredith Phillips Jr. 1977. Bryn Mawr College Excavations in Tuscany, 1975. American Journal of Archaeology 81: 85–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nielsen, Erik, and Anthony Tuck. 2001. An Orientalizing Period Complex at Poggio Civitate (Murlo): A Preliminary View. Etruscan Studies 8: 35–63. [Google Scholar]

- O’Donoghue, Eóin. 2013. The Mute Statues Speak: The Archaic Period Acroteria from Poggio Civitate (Murlo). European Journal of Archaeology 16: 268–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pantelia, Maria. 1993. Spinning and Weaving: Ideas of Domestic Order in Homer. The American Journal of Philology 114: 493–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phillips, Kyle Meredith, Jr. 1970. “Bryn Mawr College Excavations in Tuscany, 1969. American Journal of Archaeology 75: 257–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phillips, Kyle Meredith, Jr. 1993. In the Hills of Tuscany: Recent Excavations at the Etruscan Site of Poggio Civitate (Murlo, Siena). Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Museum of Archaeology. [Google Scholar]

- Phillips, Kyle Meredith, Jr. 1994. Stamped Impasto Pottery Manufactured at Poggio Civitate. In Murlo and the Etruscans: Art and Society in Ancient Etruria. Edited by Richard De Puma and Jocelyn Penny Small. Madison: University of Wisconsin Press, pp. 29–46. [Google Scholar]

- Ræder Knudsen, Lise. 2002. La tessitura con le tavolette nella tomba 89. In Guerriero e sacerdote. Autorità e comunità nell’età del ferro a Verucchio. La Tomba del Trono. Edited by Patrizia von Eles. Florence: Quaderni di Archeologia dell’Emilia Romagna 6, pp. 220–34. [Google Scholar]

- Rystedt, Eva. 1983. Acquarossa IV: Early Etruscan Akroteria from Acquarossa and Poggio Civitate (Murlo). Stockholm: Paul Astrom. [Google Scholar]

- Small, Jocelyn Penny. 1971. The Banquet Frieze from Poggio Civitate (Murlo). Studi Etruschi 39: 25–61. [Google Scholar]

- Tuck, Anthony. 2006. The Social and Political Context of the 7th Century Architectural Terracottas from Poggio Civitate (Murlo). In Deliciae Fictiles III: Architectural Terracottas in Ancient Italy: New Discoveries and Interpretations: Proceedings of the International Conference Held at the American Academy in Rome, Italy, 7–8 November 2002. Edited by Ingrid Edlund-Berry, John Kenfield and Giovanna Greco. Oxford: Oxbow Books, pp. 130–35. [Google Scholar]

- Tuck, Anthony. 2009. Stories at the Loom: Patterned Textiles and the Recitation of Myth in Euripides. Arethusa 42: 151–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tuck, Anthony. 2014. Manufacturing at Poggio Civitate: Elite Consumption and Social Organization in the Etruscan Seventh Century. Etruscan Studies 17: 121–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tuck, Anthony. 2017. The Evolution and Political Use of Elite Domestic Architecture at Poggio Civitate (Murlo). Journal of Roman Archaeology 30: 227–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tuck, Anthony. 2021. Poggio Civitate (Murlo). Cities and Communitites of the Etruscans; Austin: University of Texas Press. [Google Scholar]

- Tuck, Anthony, and Ann Glennie. 2020. The Archaic Aristocracy: The Case of Murlo (Poggio Civitate). Annali della Fondazione per il Museo “Claudio Faina” 27: 515–42. [Google Scholar]

- Tuck, Anthony, and Rex Wallace. 2011. An Inscribed Rocchetto from Poggio Civitate (Murlo). Studi Etruschi 74: 197–202. [Google Scholar]

- Tuck, Anthony, Ann Glennie, Katherine Kreindler, Eóin O’Donoghue, and Cara Polsini. 2016. 2015 Excavations at Poggio Civitate and Vescovado di Murlo (Provincia di Siena). Etruscan Studies 19: 87–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tuck, Anthony, Jason Bauer, Katherine Kreindler, Theresa Huntsman, Steve Miller, Susanna Pancaldo, and Christina Powell. 2009. Center and Periphery in Inland Etruria: Poggio Civitate and the Etruscan Settlement in Vescovado di Murlo. Etruscan Studies 12: 215–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tuck, Anthony, Katherine Kreindler, and Theresa Huntsman. 2013. Excavations at Poggio Civitate (Murlo) During the 2012–13 Seasons: Domestic Architecture and Selected Finds from the Civitate a Property Zone. Etruscan Studies 16: 287–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turfa, Jean MacIntosh, and Alwin Steinmayer Jr. 2002. Interpreting Early Etruscan Structures: The Question of Murlo. Papers of the British School at Rome 70: 1–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valentini, Giovanna. 1969. Il motivo dell Potnia Theron sui vasi di bucchero. Studi Etruschi 37: 413–42. [Google Scholar]

- von Eles, Patrizia. 2002. Guerriero e sacerdote. Autorità e comunità nell’età del ferro a Verucchio. La Tomba del Trono. Florence: Quaderni di Archeologia dell’Emilia Romagna 6. [Google Scholar]

- Wikander, Örjan, and Fredrik Tobin. 2017. Roof-Tiles and Tile-Roofs at Poggio Civitate (Murlo): The Emergence of Central Italic Tile Industry. Stockholm: Svenska Institutet I Rom. [Google Scholar]

- Winter, Nancy. 2009. Symbols of Wealth and Power: Architectural Terracotta Decoration in Etruria and Central Italy, 640–510 B.C. Ann Arbor: Published for the American Academy in Rome by the University of Michigan Press. [Google Scholar]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).