A Bronze Reliquary for an Ichneumon Dedicated to the Egyptian Goddess Wadjet

Abstract

:Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Websites

| 1 | (Fischer 1986). |

| 2 | (Gardiner 1969, p. 31, §23) and (Goldwasser 2002). |

| 3 | (Shalomi-Hen 2019, p. 373) and (Richter 2019). |

| 4 | (Thuault 2017). |

| 5 | |

| 6 | |

| 7 | |

| 8 | |

| 9 | |

| 10 | |

| 11 | |

| 12 | |

| 13 | (Broze 2006). |

| 14 | (Collection de feu Omar Pacha Sultan 1929, cat. no. 81 and p. 81), where the leonine deity is identified as “Sekhmet.” I thank the present owner for permission to publish this object and for providing me with the photographs. |

| 15 | (Meeks 1986). |

| 16 | (Dolzani 1989). |

| 17 | https://www.newscientist.com/article/2106866-five-wild-lionesses-grow-a-mane-and-start-acting-like-males/ (accessed on 23 September 2021). |

| 18 | |

| 19 | |

| 20 | |

| 21 | |

| 22 | (Lashien 2020). |

| 23 | (Leitz 2018). |

| 24 | |

| 25 | |

| 26 | Inter alia, (Inconnu-Bocquillon 2001; Richter 2010), for the polyvalence of interlocking mythologies woven into the core myth; and (Étienne 2000, pp. 25–6), for a concise summary. |

| 27 | (Louarn 2020), for the significance in this myth of goddesses “behaving as men,” as an expression of a breach of the normative to express “the other,” and thereby inspire fear. |

| 28 | (Lippert 2012), for the pairings of lions and cats. |

| 29 | (Vandier 1967). |

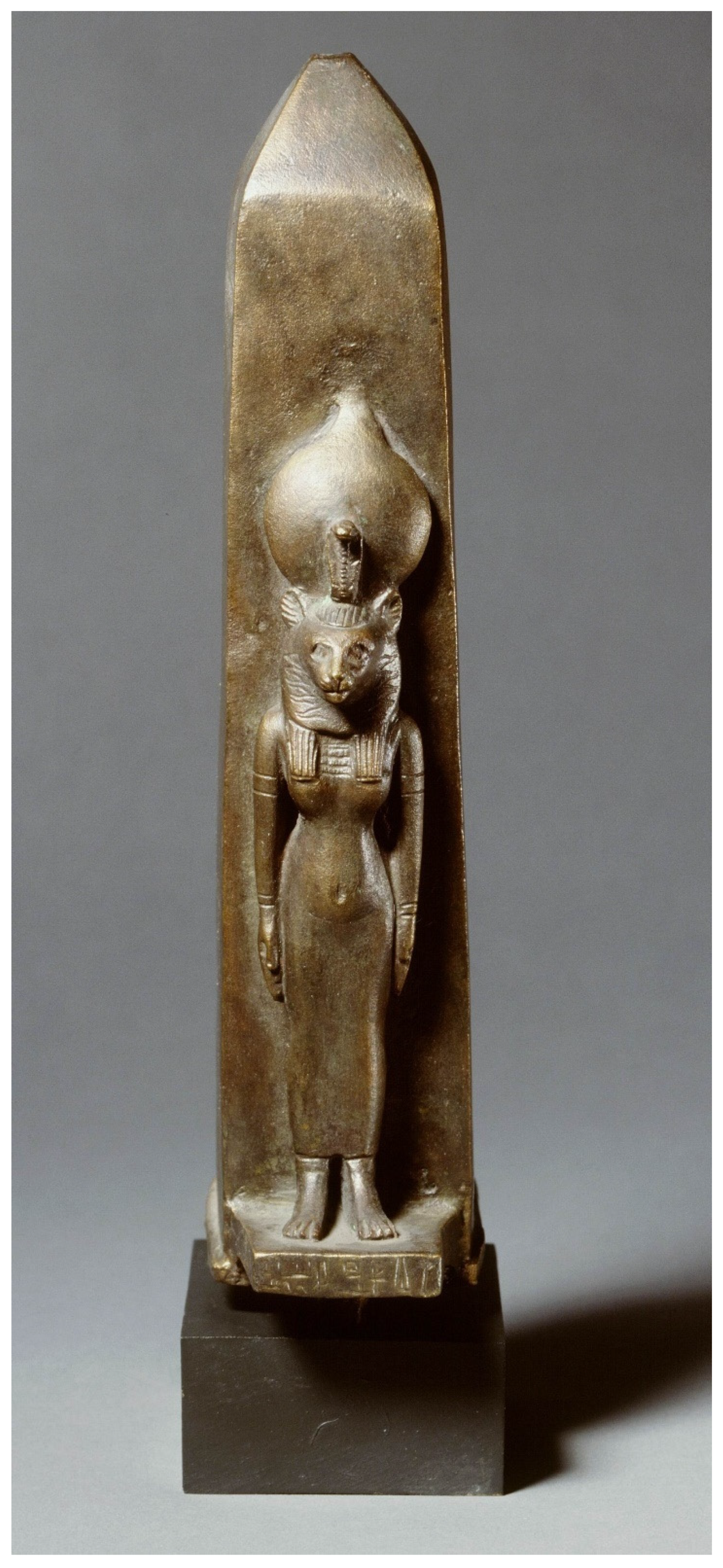

| 30 | Leiden, Rijksmuseum van Oudheden, F 1953/5.2: https://www.rmo.nl/collectie/collectiezoeker/collectiestuk/?object=13099 (accessed on 24 September 2021) incorrectly identifies this image as Sakhmet, apparently ignoring the inscription on the base. That error is corrected in the catalogue entry by (Schneider and Raven 1981, pp. 134–35, no. 137). |

| 31 | |

| 32 | (Hartung 2018). |

| 33 | |

| 34 | (Töpfer 2018). |

| 35 | |

| 36 | |

| 37 | |

| 38 | |

| 39 | |

| 40 | |

| 41 | (Evans 2010); and (Evans 2016). |

| 42 | |

| 43 | |

| 44 | (Fischer-Elfret 1986, col. 907; Delhez 2013); and (Brunner-Traut 1980, col. 122), suggesting a link between “Leto” and “Uto,” an alternate reading of one of the names of Wadjet. |

| 45 | Pompeii Regio VI.12.2, one of the framing elements of the mosaic depicting a battle between Alexander the Great and his Persian adversary, Naples, The National Archaeological Museum, 9990: (Versluys 2002, pp. 267–68); Il Museo archeologico nazionale 1984, 46 [upper left-hand corner]. |

| 46 | (Lippert 2012), for the pairing of the shrew mouse and ichneumon. |

| 47 | |

| 48 | |

| 49 | |

| 50 | |

| 51 | (Vadas 2020, p. 96); and (Graindorge 1996). |

| 52 | (Bothmer 1949). |

| 53 | |

| 54 | (Davies 2007). |

| 55 | |

| 56 | |

| 57 | Berlin, Ägyptisches Museum und Papyrussammlung 13144: http://www.smb-digital.de/eMuseumPlus?service=ExternalInterface&module=collection&objectId=591642&viewType=detailView (accessed on 24 September 2021); (Roeder 1956, Volume 1: 291,f and 2: plate 42,2) and (Bothmer 1949). |

| 58 | |

| 59 | (Kessler 2005). |

| 60 | (Ikram 2015); and (Flossmann-Schütze 2017). |

| 61 |

References

- Ballet, Pascale. 2011. De Per Ouadjyt à Bouto (Tell el-Fara’in): Un grand centre urbain du delta égyptien de la fin de la basse époque à l’antiquité tardive. Comptes Rendus des Séances de l’Académie des Inscriptions & Belles-Lettres 155: 1567–89. [Google Scholar]

- Bedier, Shafa. 1994. Ein Stiftungsdekret Thutmosis’ III. aus Buto. In Aspekte Spätägyptischer Kultur: Festschrift für Erich Winter Zum 65. Geburtstag. Edited by Minas Martina and Jürgen Zeidler. Mainz: Philipp von Zabern, pp. 35–50. [Google Scholar]

- Bell, Lanny. 2002. Divine kingship and the theology of the obelisk cult in the temples of Thebes. In 5. Ägyptologische Tempeltagung: Würzburg, 23–26 September 1999. Edited by Beinlich Horst, Jochen Hallof, Holger Hussy and Christiane von Pfeil. Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz, pp. 17–46. [Google Scholar]

- Bianchi, Robert Steven. forthcoming. A group of vessels in the shape of horned, African ruminants. Beitrage zur Sudanarchologie, unpublished.

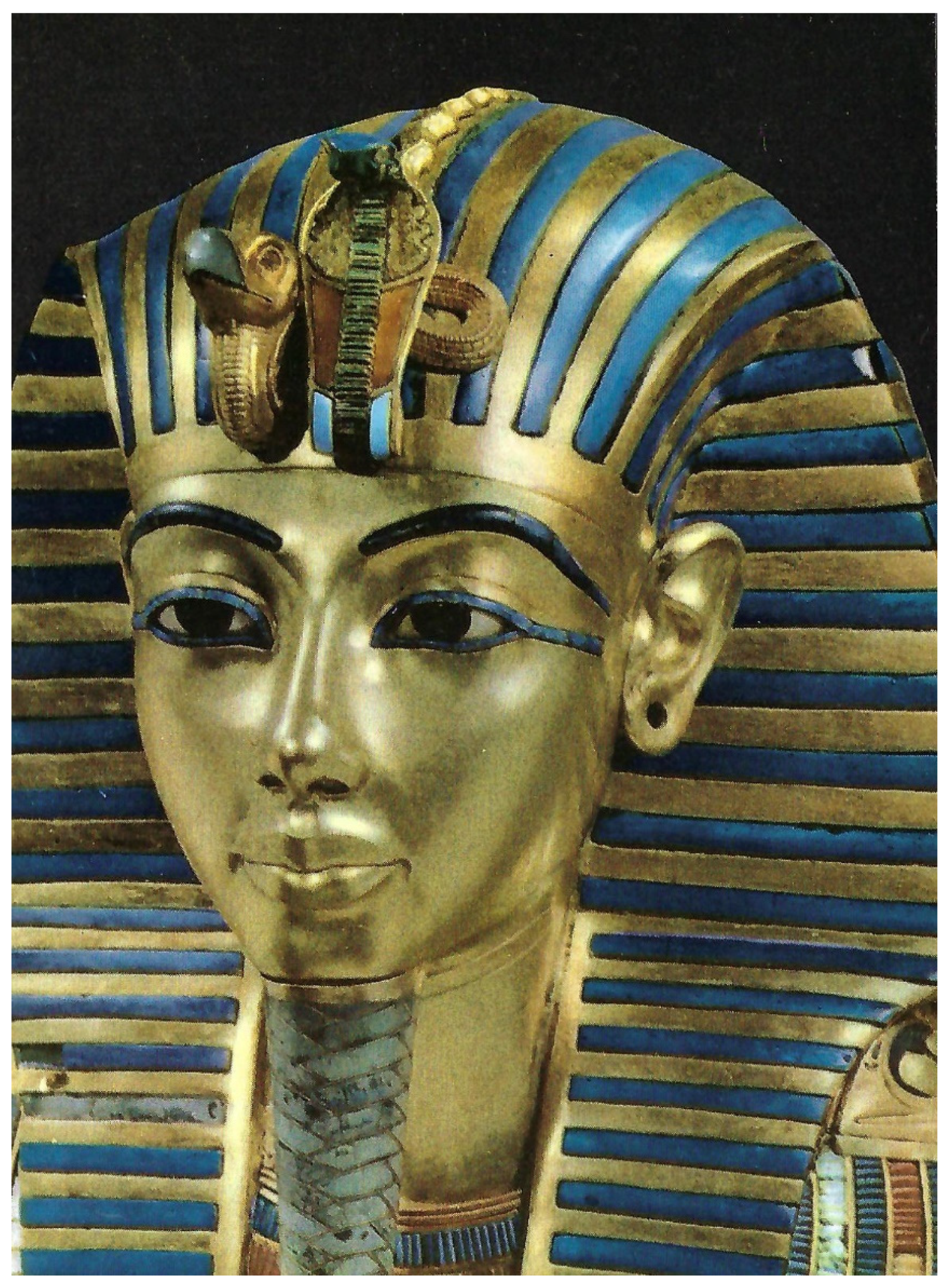

- Bosse-Griffiths, Kate. 1973. The Great Enchantress in the little golden shrine of Tut’ankhamūn. Journal of Egyptian Archaeology 59: 100–8. [Google Scholar]

- Bothmer, Bernard V. 1949. Statuettes of WAD.t as ichneumon coffins. Journal of Near Eastern Studies 8: 121–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brentjes, Burchard. 1967. Schleichkatzen (Viverridae) und Marder (Mustelidae) in der Kultur des alten Orients. Saugetierkundliche Mitteilungen 15: 304–17. [Google Scholar]

- Broze, Michèle. 2006. Dessiner les dieux en Égypte ancienne: Créer avec l’image et créer avec les mots. In Sphinx: Les Gardiens de l’Égypte. Edited by Warmenbol Eugène. Brussels: Mercator, pp. 123–31. [Google Scholar]

- Brunner-Traut, Emma. 1980. Ichneumon. In Lexikon der Ägyptologie III: Horhekenu—Megebr. Edited by Helck Wolfgang and Wolfhart Westendorf. Wiesbaden: Otto Harrassowitz, cols., pp. 122–33. [Google Scholar]

- Bussmann, Richard. 2019. Practice, meaning and intention: Interpreting votive objects from ancient Egypt. In Perspectives on Lived Religion: Practices—Transmission—Landscape. Edited by Staring Nico, Huw Twiston Davies and Lara Weiss. Leiden: Sidestone Press, pp. 73–84. [Google Scholar]

- Cauville, Sylvie. 2007. Dendara: Le Temple d’Isis. 2 vols. Cairo: Institut Français d’Archéologie Orientale. [Google Scholar]

- Collection de feu Omar Pacha Sultan, le Caire: Catalogue Descriptif: I. Art Egyptien. II. Art Musulman. 1929. Paris: Librairie de France.

- Cooney, Kathlyn M. 2021. Coffin Commerce: How a Funerary Materiality Formed Ancient Egypt. Cambridge Elements: Elements in Ancient Egypt in Context. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Coulon, Laurent. 2011. Les uræi gardiens du fétiche abydénien: Un motif osirien et sa diffusion à l’époque saïte. In La XXVIe Dynastie, Continuités et Ruptures: Actes du Colloque International Organisé les 26 et 27 Novembre 2004 à l’Université Charles-de-Gaulle—Lille 3; Promenade Saïte Avec Jean Yoyotte. Edited by Devauchelle Didier. Paris: Cybele, pp. 85–108. [Google Scholar]

- Davies, Sue. 2007. Bronzes from the Sacred Animal Necropolis at North Saqqara. In Gifts for the Gods: Images from Egyptian Temples. Edited by Hill Marsha and Deborah Schorsch. New Haven, London and New York: Yale University Press, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, pp. 174–87. [Google Scholar]

- Delhez, Julien. 2013. Considérations d’Hérodote sur la loutre, la mangouste-ichneumon et la musaraigne. Research Antiquae 10: 131–56. [Google Scholar]

- Desroches Noblecourt, Christiane. 1996. Les déesses et le sema-taouy. In Studies in Honor of William Kelly Simpson. Edited by Manuelian Peter Der. Boston: Department of Ancient Egyptian, Nubian and Near Eastern Art, Museum of Fine Arts, vol. 1, pp. 191–97. [Google Scholar]

- Di Biase-Dyson, Camilla. 2014. Multiple dimensions of interpretation: Reassessing the magic brick Berlin ÄMP 15559. Studien zur Altägyptischen Kultur 43: 93–107. [Google Scholar]

- Di Biase-Dyson, Camilla, and Gaëlle Chantrain. 2021. Metaphors of sensory experience in ancient Egyptian texts. Emotion, personality, and social interaction. In The Routledge Handbook of the Senses in the Ancient Near East. Edited by Naumann Kiersten and Allison Thomason. Oxfordshire: Routledge, pp. 603–35. [Google Scholar]

- Dolzani, Claudia. 1989. Aspetti e problemi del culto degli animali nella religione egiziana. In Akten des Vierten Internationalen Ägyptologen Kongresses München 1985. Band 3: Linguistik, Philologie, Religion, 231–240. Edited by Schoske Sylvia. Hamburg: Busk, p. 3. [Google Scholar]

- Étienne, Marc. 2000. Heka: Magie et Envoûtement Dans l’Égypte Ancienne. Les Dossiers du Musée du Louvre 57. Paris: Réunion des Musées Nationaux. [Google Scholar]

- Evans, Linda. 2010. Otter or mongoose? Chewing over evidence in wall scenes. In Egyptian Culture and Society: Studies in Honour of Naguib Kanawati. Edited by Woods Alexandra, Ann McFarlane and Susanne Binder. Cairo: Conseil Suprême des Antiquités, vol. 1, pp. 119–29. [Google Scholar]

- Evans, Linda. 2016. Beasts and beliefs at Beni Hassan: A preliminary report. Journal of the American Research Center in Egypt 52: 219–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fischer, Henry George. 1986. L’écriture et L’art de l’Égypte Ancienne: Quatre Leçons sur la Paléographie et L’épigraphie Pharaoniques. Essais et Conférences. Paris: Presses Universitaires de France. [Google Scholar]

- Fischer-Elfret, Hans-Werner. 1986. Uto. In Lexikon der Ägyptologie VI: Stele-Zypresse. Edited by Helck Wolfgang and Wolfhart Westendorf. Wiesbaden: Otto Harrassowitz, cols, pp. 906–11. [Google Scholar]

- Flossmann-Schütze, Mélaine. 2017. Études sur le cadre de vie d’une association religieuse dans l’Égypte gréco-romaine: L’exemple de Touna el-Gebel. In Proceedings of the XI International Congress of Egyptologists, Florence Egyptian Museum, Florence, 23–30 August 2015. Edited by Rosati Gloria and Maria Cristina Guidotti. Oxford: Archeopress, pp. 203–8. [Google Scholar]

- Gamelin, Th. 2021. Divinités et génies ailés en Égypte ancienne—Protecteurs et dispensateurs de vie. Kasion 6: 57–92. [Google Scholar]

- Gardiner, Alan H. 1969. Egyptian Grammar: Being an Introduction to the Study of Hieroglyphs. Oxford: Clarendon Press. [Google Scholar]

- Goldwasser, Orly. 2002. Prophets, Lovers and Giraffes: Wor(l)d Classification in Ancient Egypt. Classification and Categorization in Ancient Egypt 3, Göttinger Orientforschungen, 4. Reihe: Ägypten 38. Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz. [Google Scholar]

- Graindorge, Catherine. 1996. La quête de la lumière au mois de Khoiak: Une histoire d’oies. Journal of Egyptian Archaeology 82: 83–105. [Google Scholar]

- Hartung, Ulrich. 2018. Buto I: The city’s early history. Egyptian Archaeology 53: 30–32. [Google Scholar]

- Hastings, Elizabeth Anne. 1997. The Sculpture from the Sacred Animal Necropolis at North Saqqāra 1964–1976. Egypt Exploration Society, Excavation Memoir 61. London: Egypt Exploration Society. [Google Scholar]

- Hornung, Erik. 1992. Idea into Image: Essays on Ancient Egyptian Thought. Translated by Elizabeth Bredeck. New York: Timken. [Google Scholar]

- Houston, Stephen, and Andréas Stauder. 2020. What is a hieroglyph? L’Homme: Revue Française D’Anthropologie 233: 9–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ikram, Salima. 2015. Speculations on the role of animal cults in the economy of ancient Egypt. In Apprivoiser le Sauvage/Taming the Wild. Edited by Magali Massiera, Bernard Mathieu and Frédéric Rouffet. Montpellier: Université Paul Valéry Montpellier 3, pp. 11–227. [Google Scholar]

- Inconnu-Bocquillon, Danielle. 2001. Le Mythe de la Déesse Lointaine à Philae. Bibliothèque D’étude 132. Le Caire: Institut Français D’archéologie Orientale. [Google Scholar]

- Jacco, Dieleman. 2019. The Greco-Egyptian magical papyri. In Guide to the Study of Ancient Magic. Edited by David Frankfurter. Guide to the study of ancient magic. Religions in the Graeco-Roman world. Leiden: Brill, vol. 189, pp. 283–321. [Google Scholar]

- James, Thomas Garnet Henry. 1982. The wooden figure of Wadjet with two painted representations of Amasis. Journal of Egyptian Archaeology 68: 156–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kessler, Dieter. 2005. Tierische Missverständnisse: Grundsätzliches zu Fragen des Tierkultes. In Tierkulte im Pharaonischen Ägypten und im Kulturvergleich. Edited by Fitzenreiter Martin. London: Golden House, pp. 33–67. [Google Scholar]

- Kilany, Engy El, and Heba Mahran. 2015. What lies under the chair! A study in ancient Egyptian private tomb scenes. Part I: Animals. Journal of the American Research Center in Egypt 51: 243–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurth, Dieter. 1990. Der Sarg der Teüris: Eine Studie Zum Totenglauben im Römerzeitlichen Ägypten. Aegyptiaca Treverensia: Trierer Studien Zum Griechisch-Römischen Ägypten 6. Mainz am Rhein: Philipp von Zabern. [Google Scholar]

- Kwiecinski, Jakub M. 2019. Depictions of crocodiles and scorpions in Predynastic and early Dynastic Egypt: The case of the Abydos flint animals. Göttinger Miszellen 257: 97–107. [Google Scholar]

- Lashien, Miral. 2020. Donkeys in the Old and Middle Kingdoms according to the representations and livestock counts from private tombs. Études et Travaux 33: 121–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leitz, Christian. 2018. Einige Bezeichnungen für kleine und mittelgroße Säugetiere im Alten Ägypten. Bulletin de l’Institut Français d’Archéologie Orientale 118: 241–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lippert, Sandra Luisa. 2012. Stachelschwein, Igel und Schmetterlingspuppe. In “Parcourir l’éternité”: Hommages à Jean Yoyotte. Edited by Zivie-Coche Christiane and Ivan Guermeur. Turnhout: Brepols, vol. 2, pp. 777–99. [Google Scholar]

- Lloyd, Alan B. 1982. The inscription of Udjaḥorresnet: A collaborator’s testament. Journal of Egyptian Archaeology 68: 166–80. [Google Scholar]

- Louarn, Adrien. 2020. Agir en mâle, étant une femme. Égypte Nilotique et Méditerranéenne 13: 311–17. [Google Scholar]

- Meeks, Dimitri. 1986. Zoomorphie et image des dieux dans l’Égypte ancienne. In Corps des Dieux. Edited by Malamoud Charles and Jean-Pierre Vernant. T emps de la réflexion 7. Paris: Gallimard, pp. 171–91. [Google Scholar]

- Rashwan, Hany. 2019. Ancient Egyptian image-writing: Between the unspoken and visual poetics. Journal of the American Research Center in Egypt 55: 137–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richter, Barbara A. 2010. On the heels of the Wandering Goddess: The myth and the festival at the temples of the Wadi el-Hallel and Dendera. In 8. Ägyptologische Tempeltagung: Interconnections between Temples, Warschau, 22–25 September 2008. Edited by Dolińska Monika and Horst Beinlich. Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz, pp. 155–86. [Google Scholar]

- Richter, Barbara A. 2019. Gods, priests, and bald men: A new look at Book of the Dead 103 ("being beside Hathor"). In The Book of the Dead, Saite through Ptolemaic Periods: Essays on Books of the Dead and Related Materials. Edited by Mosher Malcolm Jr. Prescott: Malcolm Mosher Jr., pp. 519–40. [Google Scholar]

- Roeder, Günther. 1956. Ägyptische Bronzefiguren. 2 vols. Mitteilungen aus der Ägyptischen Sammlung 6. Berlin: N.p. At head of title: Staatliche Museen zu Berlin. [Google Scholar]

- Rowland, Joanne, Salima Ikram, Geoffrey J. Tassie, and Lisa Yeomans. 2013. The sacred falcon necropolis of Djedhor(?) at Quesna: Recent investigations from 2006–2012. Journal of Egyptian Archaeology 99: 53–84. [Google Scholar]

- Sainte Fare Garnot, Jean. 1937. Le lion dans l’art égyptien. Bulletin de l’Institut Français d’Archéologie Orientale 37: 75–91. [Google Scholar]

- Schneider, Hans D., and Maarten J. Raven. 1981. De Egyptische Oudheid: Een Inleiding aan de Hand van de Egyptische Verzameling in Het Rijksmuseum van Oudheden to Leiden. ‘s-Gravenhage: Staatsuitgeverij. [Google Scholar]

- Shalomi-Hen, Racheli. 2019. The two kites and the Osirian revolution. In Old Kingdom Art and Archaeology 7: Proceedings of the International Conference; Università Degli Studi di Milano 3–7 July 2017. Edited by Piacentini Patrizia and Alessio Delli Castelli. Milano: Pontremoli, vol. 1, pp. 372–77. [Google Scholar]

- Shaw, Ian, and Paul Nicholson. 1995. British Museum Dictionary of Ancient Egypt. London: British Museum Press. [Google Scholar]

- Sweeney, Deborah, Christian Herrmann, Ido Koch, Yuval Gadot, Manfred Oeming, and Oded Lipschits. 2018. A triad amulet from Tel Azekah. Israel Exploration Journal 68: 129–49. [Google Scholar]

- Szpakowska, Kasia. 2011. Demons in the dark: Nightmares and other nocturnal enemies in ancient Egypt. In Ancient Egyptian Demonology: Studies on the Boundaries between the Demonic and the Divine in Egyptian Magic. Edited by Kousoulis Panagiotis. Leuven: Peeters, Departement Oosterse Studies. pp. 63–76. [Google Scholar]

- Thuault, Simon. 2017. Research on Old Kingdom "dissimilation graphique": World-view and categorization. In Proceedings of the XI International Congress of Egyptologists, Florence Egyptian Museum, Florence, 23–30 August 2015. Edited by Rosati Gloria and Maria Cristina Guidotti. Oxford: Archeopress, pp. 633–37. [Google Scholar]

- Töpfer, Susanne. 2018. The body of the king and of the goddess: Materiality in and through manuals for Pharaoh from Tebtunis. In The Materiality of Texts from Ancient Egypt: New Approaches to the Study of Textual Material from the Early Pharaonic to the Late Antique Period. Edited by Hoogendijk Francisca A.J. and Steffie van Gompel. Leiden and Boston: Brill, pp. 35–42. [Google Scholar]

- Vadas, Réka. 2020. “The beautiful place of kyphi and wine”: The laboratory at Esna temple. Égypte Nilotique et Méditerranéenne 13: 93–132. [Google Scholar]

- Vandier, Jacques. 1967. Ouadjet et l’Horus léontocéphale de Bouto: À propos d’un bronze du Musée de Chaalis. Monuments et Mémoires de la Fondation Eugène Piot 55: 7–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Velde, H. Te. 1980. A few remarks upon the religious significance of animals in ancient Egypt. Numen 27: 76–82. [Google Scholar]

- Vernus, Pascal, and Jean Yoyotte. 2005. Bestiaire des Pharaons. Paris: Agnès Viénot, Perrin. [Google Scholar]

- Versluys, Miguel J. 2002. Aegyptiaca Romana: Nilotic Scenes and the Roman Views of Egypt. Religions in the Graeco-Roman World 144. Leiden and Boston: Brill. [Google Scholar]

- Yoyotte, Jean. 1988. Des lions et des chats: Contribution à la prosopographie de l’époque libyenne. Revue D’égyptologie 39: 155–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ziegler, Christiane. 1979. À propos du rite des quatre boules. Bulletin de l’Institut Français d’Archéologie Orientale 79: 437–39. [Google Scholar]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Bianchi, R.S. A Bronze Reliquary for an Ichneumon Dedicated to the Egyptian Goddess Wadjet. Arts 2022, 11, 21. https://doi.org/10.3390/arts11010021

Bianchi RS. A Bronze Reliquary for an Ichneumon Dedicated to the Egyptian Goddess Wadjet. Arts. 2022; 11(1):21. https://doi.org/10.3390/arts11010021

Chicago/Turabian StyleBianchi, Robert Steven. 2022. "A Bronze Reliquary for an Ichneumon Dedicated to the Egyptian Goddess Wadjet" Arts 11, no. 1: 21. https://doi.org/10.3390/arts11010021

APA StyleBianchi, R. S. (2022). A Bronze Reliquary for an Ichneumon Dedicated to the Egyptian Goddess Wadjet. Arts, 11(1), 21. https://doi.org/10.3390/arts11010021