Art and the City: Contemporary Art Galleries Districts in Paris from the End of the 19th Century until Today

Abstract

:1. Introduction

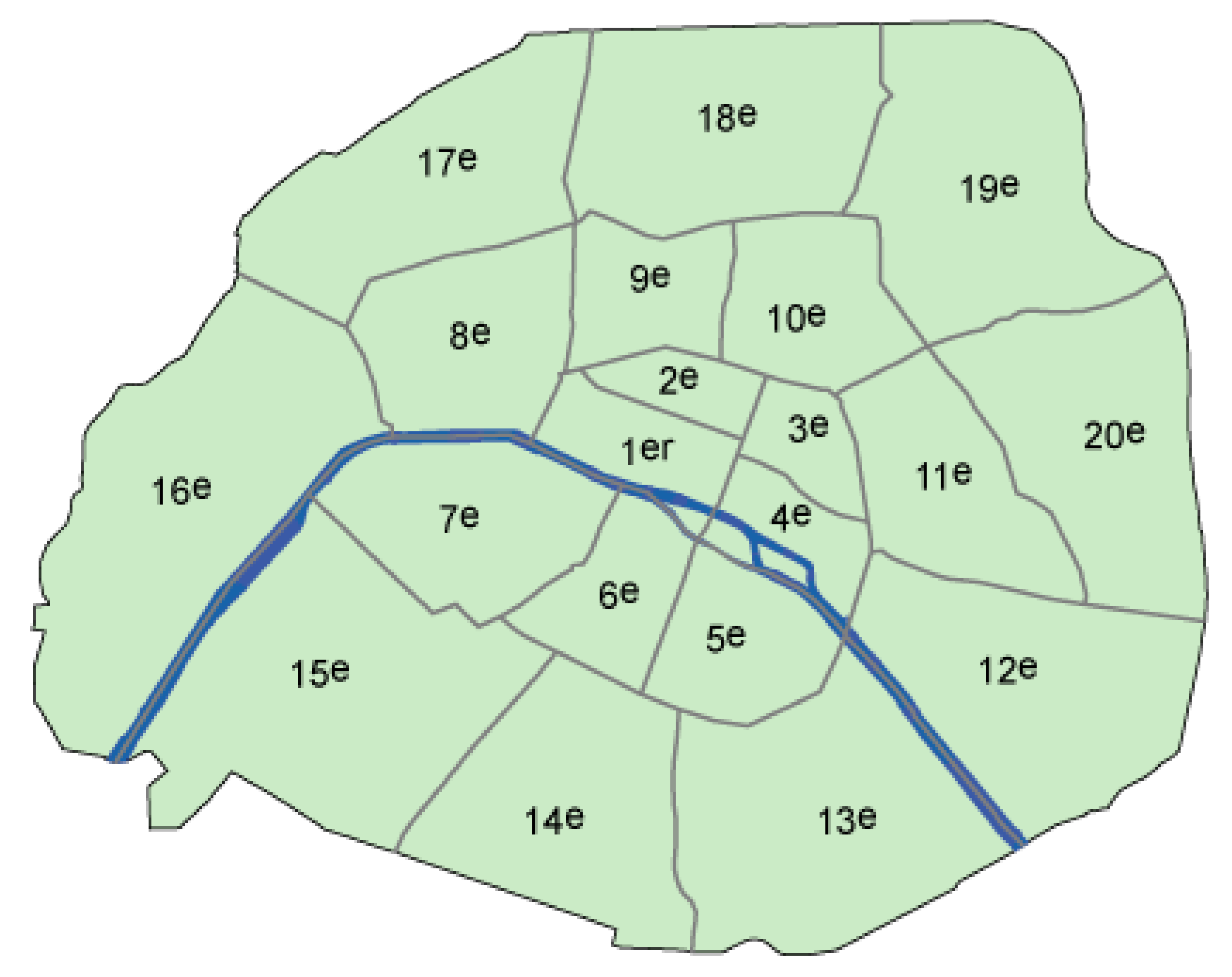

2. The Long Presence of French Galleries in the 8th Arrondissement of Paris

Ambroise Vollard: 37, 39 and 6 rue Lafitte, Paris 9ème (1893–1914)

Daniel-Henry Kahnweiler: 28 rue Vignon, Paris 9ème (1907–1914)/29bis rue d’Astorg, Paris 8ème (1920–1940)

A l’étoile scellée: 11 rue du Pré-aux-Clercs, Paris 7ème (1952–1956)

Galerie Cahiers d’art: 14 rue du Dragon, Paris 6ème (1934–1970)

Jeanne Bucher: 3 and 5 rue du cherche-Midi, Paris 6ème (1925–1932)/other places (1932–1935)/9ter boulevard du Montparnasse, Paris 6ème (1936–1960)

Daniel Cordier 5: 8 rue de Duras, Paris 8ème (1956–1959)/8 rue de Miromesnil 75008, Paris, 8ème (1959–1964)

Denise René: 124 rue la Boétie, Paris 8ème (1944–19776)

Louis Carré: 10 avenue de Messine, Paris 8ème (1940–1966)

Alphonse Chave: 13 rue Isnard, Vence, Alpes Maritimes (1947–1975)

Galerie de France: 3 rue du Faubourg Saint-Honoré, Paris 8ème (1942–1981)

Before the Marais (especially the section in the 3rd arrondissement more than in the 4th) started booming and asserting itself as the new scene of contemporary art in Paris, it was indeed the 8th arrondissement and not the Saint-Germain-des-Prés neighborhood that remained dominant after dislodging the 9th at the turn of the century. It is true that this urban Right Bank area, north of the Seine, was now in competition with the Left Bank galleries, but our figures clearly show that it had emphatically not lost its predominance.Iris Clert: 3 rue des Beaux-Arts, Paris 6ème (1956–1961)/28 rue du Faubourg Saint-Honoré, Paris 8ème (1961–1971)/3 rue Duphot, Paris 1er (1971–1979)/Le C.A.R.A.T, 19 rue Madeleine Michelis, Neuilly-sur-Seine (1980–1986)

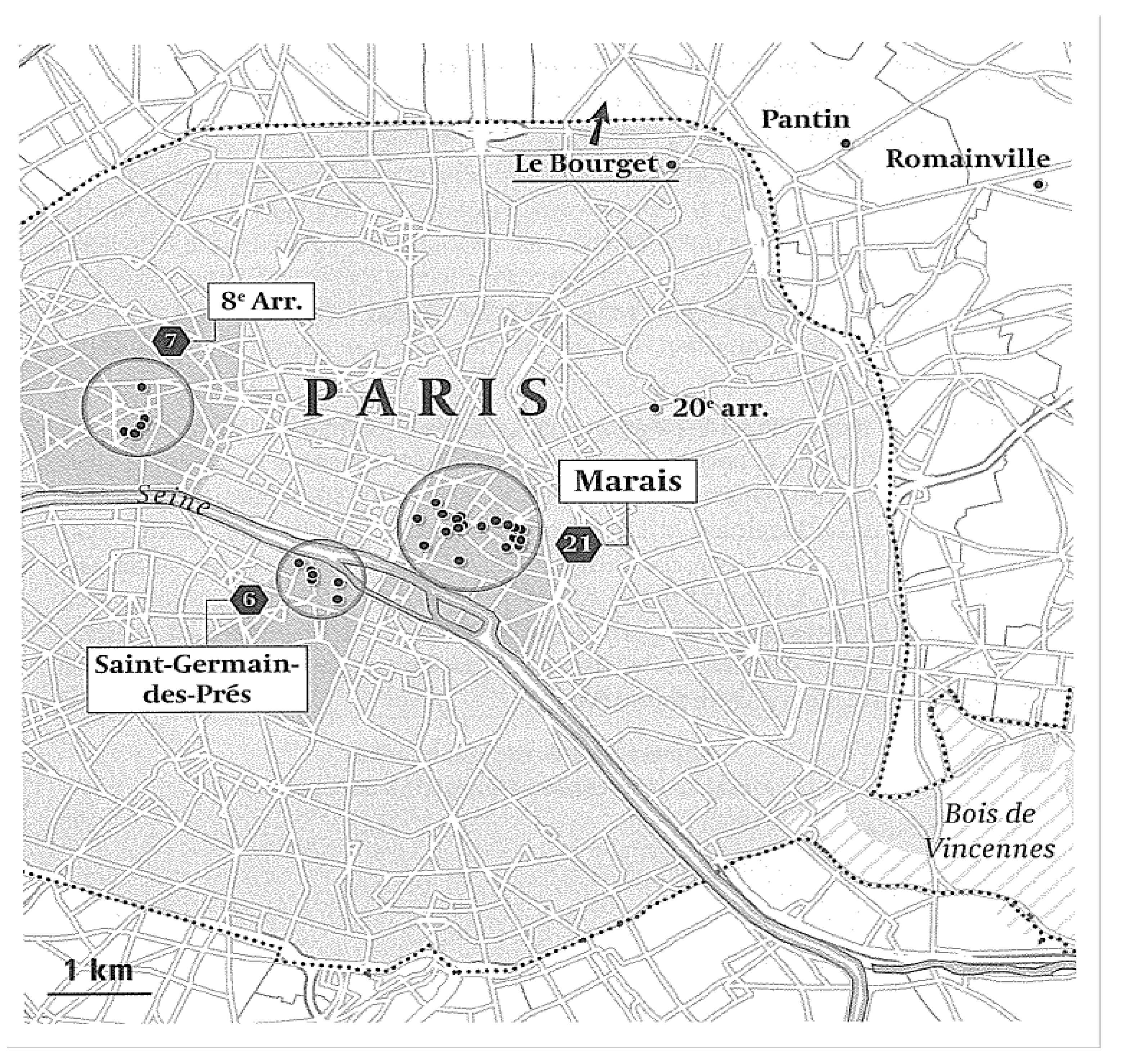

3. The Marais: Advent and Development of the Area as of the 1970s

Tatiana Debroux shows how the Marais neighborhood thrived during the 1970s and 1980s: “The 1975 map and even more the 1986 one saw the embryo of what today is the main concentration of galleries, members (of the CPGA), at the junction of the 4th and 3rd arrondissements, connected by the rue Quincampoix. In 1994 in the Saint-Merri neighborhood, and even more in 2016 in the Archives neighborhood, the proportion of members was between 10 and 20% out of a total that had greatly increased. The emergence and then the consolidation of the 3rd arrondissement pointed to the creation of a third pole of Parisian galleries, in comparison with that of the 8th (relatively very diminished) and of the Left Bank (of comparable importance).”“Left bank: 40%Beaubourg-Marais: 29%Right bank: 19%Bastille: 8%Other neighborhoods: 4%”.

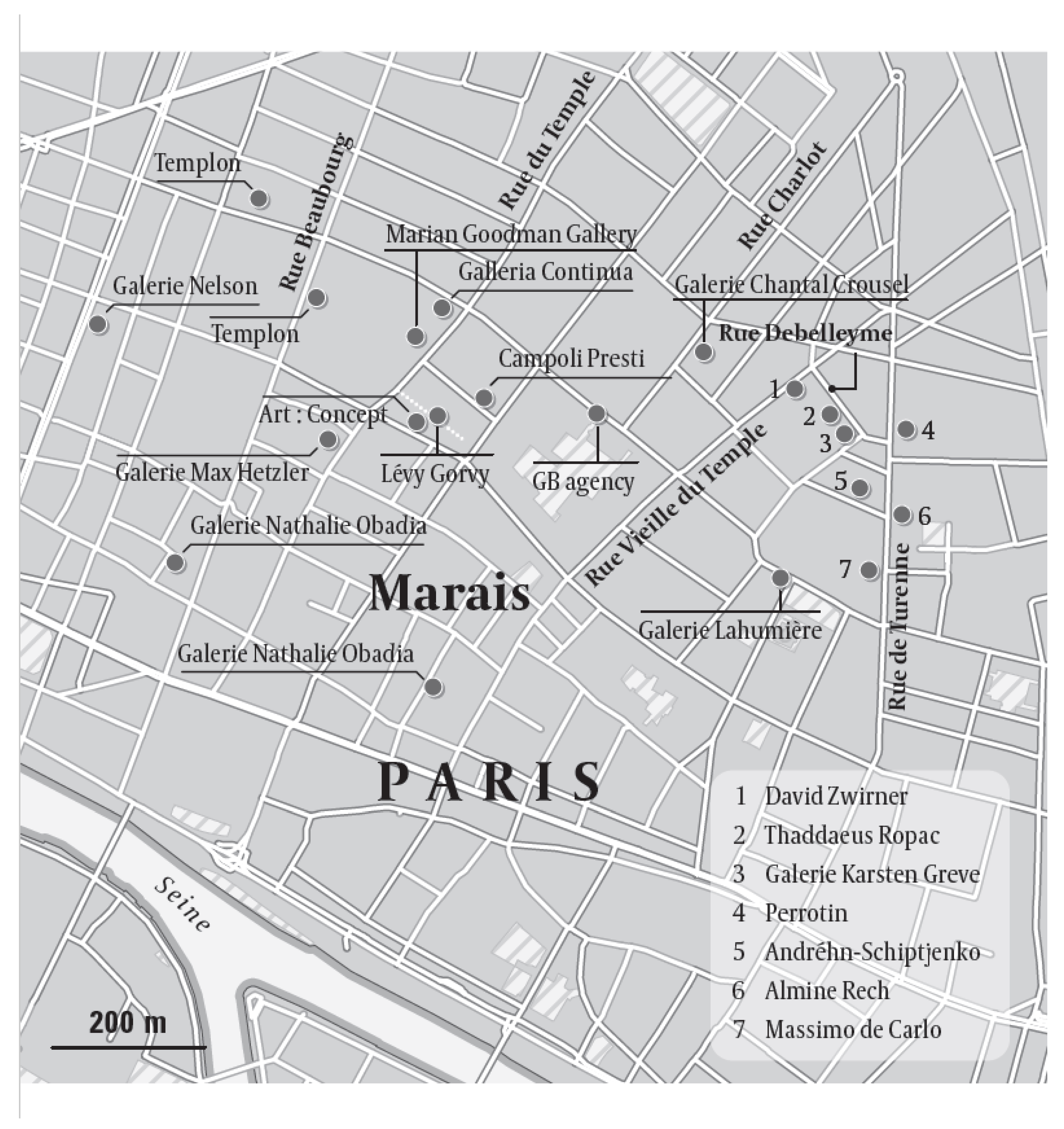

4. The Triumph of the Marais: The Dominant District of Contemporary Galleries

In light of the amazing success of these galleries, it would be a mistake to assume that the choice of setting up in the Marais was obvious. Still today, even if this parcel of urban space takes the lead in welcoming many galleries, its drawback in relation to the 8th arrondissement is its lack of luxury hotels patronized by the wealthy clientele passing through Paris, but also because it is farther from the more bourgeois areas (Pinçon and Pinçon-Charlot 1992, 1996, 2016) where most often the French collectors live—that is, the 16th, 8th, 7th, and 17th arrondissements (at least the western half of this latter district). The neighborhood’s image, plus the mass effect, draw potential buyers to the Marais. As this person working in a Marais gallery that was previously located in the 8th and dealing in historical contemporary art said, “When collectors enter this gallery in such a beautiful space in the heart of the Marais, one of the first things they say is ‘this is so far from everything! When are you going back to the 8th? It’s really so much more central.’ But you know here, as in most contemporary galleries, if you look at their client database they almost all live in the 8th, 16th, or 7th arrondissements.”“This new gallery neighborhood, inescapable today, is an outgrowth of the radical transformation of this part of Paris, one that was largely absent from the capital’s artistic geography. In 1977, the opening of the major cultural institution that is the Pompidou Center and its promises in terms of cultural clientele, along with better real estate opportunities than in the older gallery areas, account for the fact that several of them quickly settled in the neighborhood, then were joined by many other galleries in the following years. At the moment, the 3rd arrondissement caters to 42% of the galleries belonging to the Committee (Professionnel des Galeries d’art), outstripping the 6th arrondissement (20%) and the 8th arrondissement, which had long been the dominant area but now accounts for only 11.5% of the members of the CPGA in 2016” (Debroux 2017, pp. 153–55). It must not be forgotten that these figures reflect all of the members of the Comité professionnel des Galeries d’Art and not only those galleries offering contemporary art.”

The Marais area clearly overshadows12 the others, as this district alone weighs more than all the other gallery places combined, and the gap between it and the next in line, the Saint-Germain-des-Prés neighborhood, is enormous.Number of galleries by neighborhood among those participating in the 2019 FIAC:Marais (3rd or 4th arrondissement): 28Saint-Germain-des-Prés (6th arrondissement): 88th arrondissement: 4Belleville (20th arrondissement): 49th arrondissement: 213th arrondissement: 118th arrondissement: 1

Today, accounting for the implantation of contemporary galleries in Paris means highlighting the incontestable role of the Marais area. For established galleries there is virtually no longer any question—the Marais is where you have to open shop, with two slight (at least in numerical terms) exceptions: The mammoth Gagosian gallery of US origin has set up in the heart of the very bourgeois 8th arrondissement, around the corner from the auctioneers Christie’s and Sotheby’s. It met up with the important Lelong gallery, established on rue de Téhéran, which opened a second space nearby, on avenue Matignon, in 2018, consolidating its foothold in the neighborhood. In Saint-Germain-des-Prés there are only Kamel Mennour, with three spaces close by—the last of which opened in 2020 (and one small annex avenue Matignon); the gallery Georges-Philippe and Nathalie Vallois (which also opened a second space in the same neighborhood in 2016); and Loevenbruk. The “Rive Gauche” sign has become atypical and looks like a determined statement (Bourdieu and Delsaut 1975).Number of galleries by neighborhood, among those participating in Art Basel in 2019:Marais (3rd and 4th arrondissements): 22Saint-Germain-des-Prés (6th arrondissement): 48th arrondissement: 413th arrondissement: 1(NB: All the other arrondissements that were previously geographically and economically peripheral if one considers the galleries accepted at the FIAC less selectively were no longer represented).

5. Changes in Gallery Space within and outside the Marais Neighborhood

6. Conclusions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| 1 | This does not mean that there are no real contemporary art galleries in France outside of the Paris region, but that there is no other city with a real contemporary gallery scene. Although intuitively one might think that the size of the city affects the existence of art galleries, in France, four names come up, and they are often in very small cities: Catherine Issert in Saint-Paul-de-Vence (a village near Nice, on the French Riviera) and Pietro Sparta in Chagny (a small town in Burgundy). Ceysson & Bénétière are located in Saint-Etienne (where it started out) but also, recently, in Lyon and in Paris, i.e., a medium-sized city, a major national center, and the French capital) by far the most populous city of the country), respectively (this same gallery is present in Luxemburg, too, and even in New York). For several years, the gallery of Italian origin, Continua, has had a space in Les Moulins, in the “département” of Seine-et-Marne, in the outer reaches of Paris. Coming from the small city of San Gimigniano, Italy, the gallery has also set up in Beijing, China, and in Havana, Cuba. More recently, it opened in Rome and Sao Paolo in 2020, and then in the center of Paris early in 2021 (in the Marais neighborhood). |

| 2 | Annex 8, pp. 515–17, Raymonde Moulin, has a map of Paris painting galleries at the end of the 19th c. (Moulin 1967). |

| 3 | Aspects of the spatial analysis of Paris contemporary art galleries from 1945 to 1970 also figure in chapter 5, “la mosaïque des galeries parisiennes,” in Julie Verlaine’s book. (Verlaine 2012). |

| 4 | “Galeries du 20e S. France 1905–1970” exhibition, Paris, Centre Pompidou, Musée National d’Art Moderne, from 22 May 2019 to March 2020. |

| 5 | The previous brochure does not mention this gallery’s arrondissement; we have added it. |

| 6 | The gallery owner continued well beyond this date. |

| 7 | In 1966, Alain Blondel and three partners created a tiny gallery that for several years first specialized in early-20th-c. art: the Quatre-Vents gallery was first located in the street of the same name in Paris 6th. The following year they set up very nearby and took the name Gallery of Luxembourg. From there they went to the Halles-Beaubourg neighborhood and launched into programming contemporary art. |

| 8 | This is to be understood as “the Right Bank” in the traditional meaning of the conservative “Paris bourgeois”, situated north of the Seine (Pinçon and Pinçon-Charlot 2016). The Marais, although also located on the Right Bank, clearly constitutes a distinct social space. |

| 9 | There are far more galleries paying dues to the Maison des Artistes than those carrying contemporary art; many sell works more in phase with the “chromos” market (Couture 1981), a more commercial art made for a majority taste than contemporary art as such. |

| 10 | The number rose to 848 for France as a whole. |

| 11 | Notice the astonishing definition of the Bastille neighborhood, at the intersection of the 3rd and 11th arrondissements, extending to zones that have nothing to do with it and really belong to a category of “others.” The choice of Bastille without extensions epitomizes the “wrong turn,” according to David Halle and Elisabeth Tiso (Halle and Tiso 2014): galleries that choose a good neighborhood at the wrong time, or in this case, a neighborhood that turns out to have been a bad choice. |

| 12 | Considering the list of participants in the second Paris fair, ArtParis, in terms of prestige, the numbers show a greater dissemination in the city of Paris of participating Parisian galleries, but it is precisely because the definition of contemporary art is looser (Quemin 2002), and the overwhelming majority of galleries accepted would not be considered contemporary by the FIAC selection committee or by that of other fairs equally recognized on the international contemporary art scene. |

| 13 | In the fall of 2021, this gallery owner left her space on rue du Bourg-Tibourg, slightly off-center from this part of Le Marais, for avenue Matignon but keeping her main space on rue du Cloître Saint-Merri, almost at the corner of rue Beaubourg. |

| 14 | In its January 2018 issue, the arts review Beaux-arts Magazine announced the implantation of 10 galleries that would become Komunuma. However, a few days before the inauguration, only five galleries were listed, and since the site has opened, it has only hosted four galleries. |

References

- Ansaloni, Claudia. 2018. The Grand Paris of Contemporary Art. Master’s thesis, Bologna University, Bologne, Italy. [Google Scholar]

- Bourdieu, Pierre. 1979. La Distinction. Critique Sociale du Jugement. Paris: Minuit. [Google Scholar]

- Bourdieu, Pierre, and Yvette Delsaut. 1975. Le couturier et sa griffe. Contribution à une théorie de la magie. Actes de la Recherche en Sciences Sociales 1: 7–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Citerni, Francesco. 2018. A New Gallery in Paris Suburbs: Galerie Thaddaeus Ropac in Pantin. Master’s thesis, Bologna University, Bologne, Italy. [Google Scholar]

- Couture, Francine. 1981. Le Marché des Chromos à Montréal. Ph.D. Thesis, Ecole des Hautes Etudes en Sciences Sociales, Paris, France. [Google Scholar]

- Debroux, Tatiana. 2017. Une histoire spatiale des membres du CPGA (1947–2017). In Le Comité Professionnel des Galeries d’Art, 70 Ans d’Histoire 1947–2017. Directed by Verlaine Julie. Paris: Hazan, pp. 150–56. [Google Scholar]

- Dufrêne, Bernadette. 2000. La Création de Beaubourg. Grenoble: Presses Universitaires de Grenoble. [Google Scholar]

- Grafmeyer, Yves, and Jean-Yves Authier. 2008. Sociologie Urbaine. Paris: Armand Colin. [Google Scholar]

- Halle, David, and Elisabeth Tiso. 2014. New York’s New Edge. Contemporary Art, the High Line and Urban Megaprojects on the Far West Side. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press. [Google Scholar]

- Misdrahi Flores, Marian. 2013. L’évaluation des Pairs et les Critères de la Qualité au Conseil des Arts et des Lettres du Québec. Le Cas des Arts Visuels Contemporains. Doctoral thesis in sociology, Université de Montréal, Montréal, QC, Canada. [Google Scholar]

- Molotch, Harvey, and Mark Treskon. 2009. Changing Art: SoHo, Chelsea and the Dynamic Geography of Galleries in New York City. International Journal of Urban and Regional Research 33: 517–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moulin, Raymonde. 1967. Le Marché de la Peinture en France. Paris: Minuit. [Google Scholar]

- Moulin, Raymonde. 1992. L’Artiste, l’Institution et le Marché. Paris: Flammarion. [Google Scholar]

- Moulin, Raymonde, and Alain Quemin. 1993. La certification de la valeur de l’art. Experts et expertises. Mondes de l’art 48: 1421–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Doherty, Brian. 2008. White Cube. L’Espace de la Galerie et son Idéologie. Paris: JRP/Ringier. [Google Scholar]

- Patry, Sylvie, ed. 2014. Paul Durand-Ruel. Le Pari de l’Impressionnisme. Paris: Réunion des Musées Nationaux. [Google Scholar]

- Pinçon, Michel, and Monique Pinçon-Charlot. 1992. Quartiers Bourgeois, Quartiers d’Affaires. Paris: Payot. [Google Scholar]

- Pinçon, Michel, and Monique Pinçon-Charlot. 1996. Grandes Fortunes. Dynasties Familiales et Formes de Richesse en France. Paris: Payot. [Google Scholar]

- Pinçon, Michel, and Monique Pinçon-Charlot. 2016. Sociologie de la Bourgeoisie. Paris: La découverte. [Google Scholar]

- Quemin, Alain. 1997. Les Commissaires-Priseurs. La Mutation d’une Profession. Paris: Anthropos-Economica. [Google Scholar]

- Quemin, Alain. 2002. L’art Contemporain International. Entre les Institutions et le Marché. Nimes; Jacqueline Chambon. Saint-Romain-au-Mont-d’Or: Artprice. [Google Scholar]

- Quemin, Alain. 2013a. Les Stars de l’Art Contemporain. Notoriété et Consécration dans les Arts Visuels. Paris: CNRS Editions. [Google Scholar]

- Quemin, Alain. 2013b. International Contemporary Art Fairs in a “Globalized” Art Market. European Societies 15: 162–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quemin, Alain. 2021. Le Monde des Galeries. Art Contemporain, Structure du Marché et Internationalisation. Paris: CNRS Editions, 470p. [Google Scholar]

- Rodríguez Morató, Arturo, and Matías I. Zarlenga. 2018. Culture-led urban regeneration policies in the Ibero-American space. International Journal of Cultural Policy 24: 628–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saint-Raymond, Léa. 2011. La Galerie Beaubourg, un Électron Libre de 1973 à 1993? Master’s Thesis in art history, Université Paris-IV, Paris, France. [Google Scholar]

- Velthuis, Olav. 2002. Talking Prices. Contemporary Art, Commercial Galleries and the Construction of Value. Ph.D. dissertation, Erasmus Universiteit, Rotterdam, The Netherlands. [Google Scholar]

- Verlaine, Julie. 2012. Les Galeries d’Art Contemporain à Paris de la Libération à la Fin des Années 1960. Une Histoire Culturelle du Marché de l’Art. Paris: Editions de la Sorbonne. [Google Scholar]

- Verlaine, Julie. 2016. Une Histoire d’Art Contemporain. Paris: Flammarion. [Google Scholar]

- Verlaine, Julie, ed. 2017. Le Comité Professionnel des Galeries d’Art. 70 ans d’histoire 1947–2017. Paris: Hazan. [Google Scholar]

- Zukin, Sharon. 1982. Loft Living: Culture and Capital in Urban Change. New Brunswick: Rutgers University Press. [Google Scholar]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Quemin, A. Art and the City: Contemporary Art Galleries Districts in Paris from the End of the 19th Century until Today. Arts 2022, 11, 20. https://doi.org/10.3390/arts11010020

Quemin A. Art and the City: Contemporary Art Galleries Districts in Paris from the End of the 19th Century until Today. Arts. 2022; 11(1):20. https://doi.org/10.3390/arts11010020

Chicago/Turabian StyleQuemin, Alain. 2022. "Art and the City: Contemporary Art Galleries Districts in Paris from the End of the 19th Century until Today" Arts 11, no. 1: 20. https://doi.org/10.3390/arts11010020

APA StyleQuemin, A. (2022). Art and the City: Contemporary Art Galleries Districts in Paris from the End of the 19th Century until Today. Arts, 11(1), 20. https://doi.org/10.3390/arts11010020