Hedgehogs and Hedgehog-Head Boats in Ancient Egyptian Religion in the Late 3rd Millennium BCE

Abstract

:1. Introduction

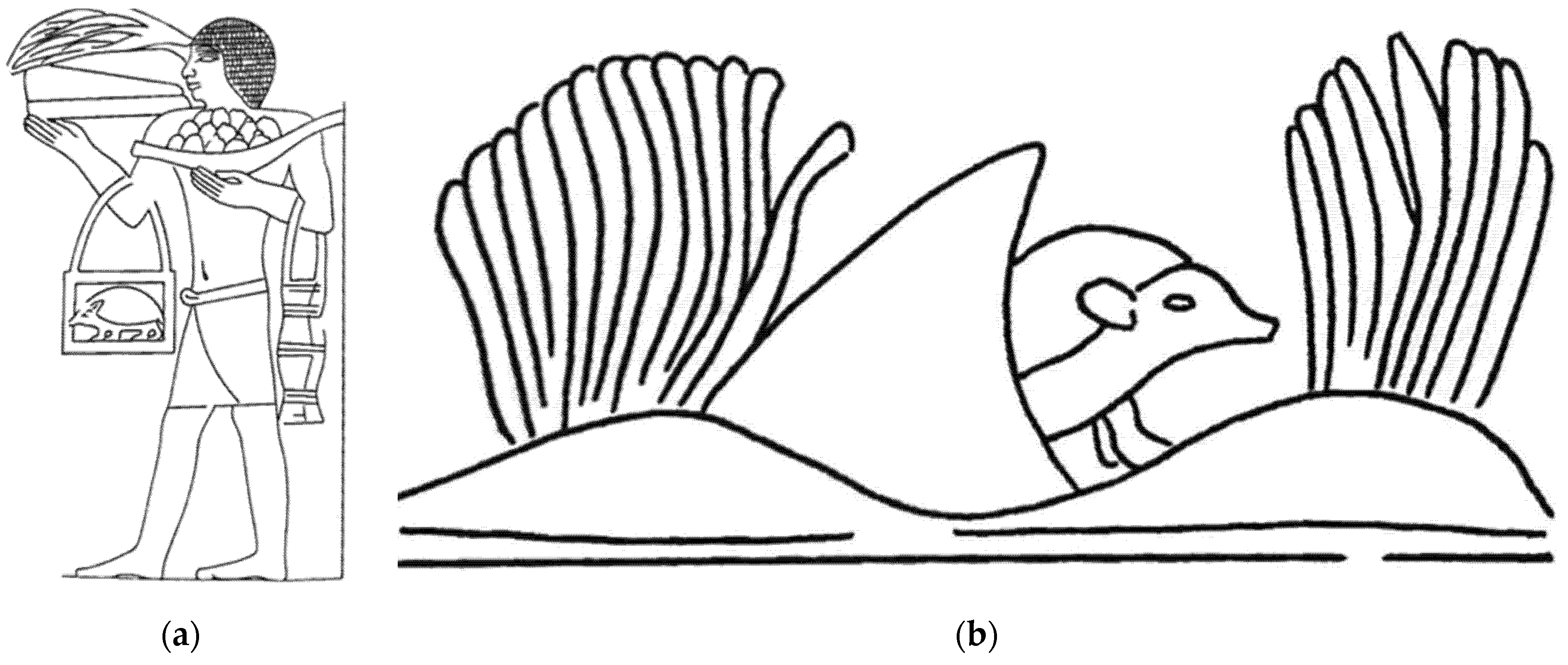

2. Hedgehogs in Ancient Egypt

3. A Note on Votive Practices

4. Hedgehog-Head Boats in the Round and in Relief

4.1. Hedgehog-Head Boat Votive Objects

4.2. Hedgehog-Head Boats in Old Kingdom Funerary Art

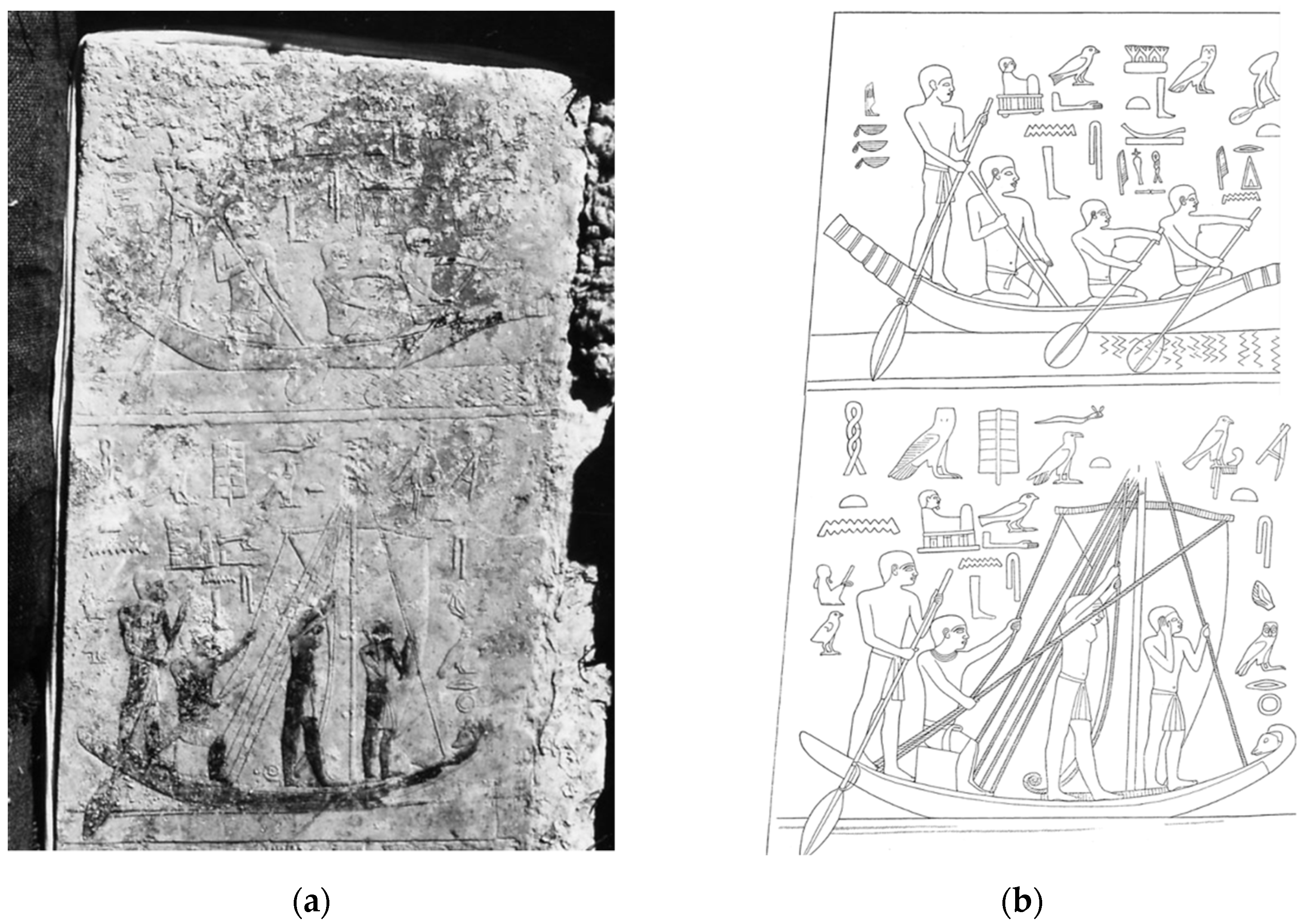

- Hedgehog-head boat being hewn in the shipyard (A)

- Hedgehog-head boat under sail (B)

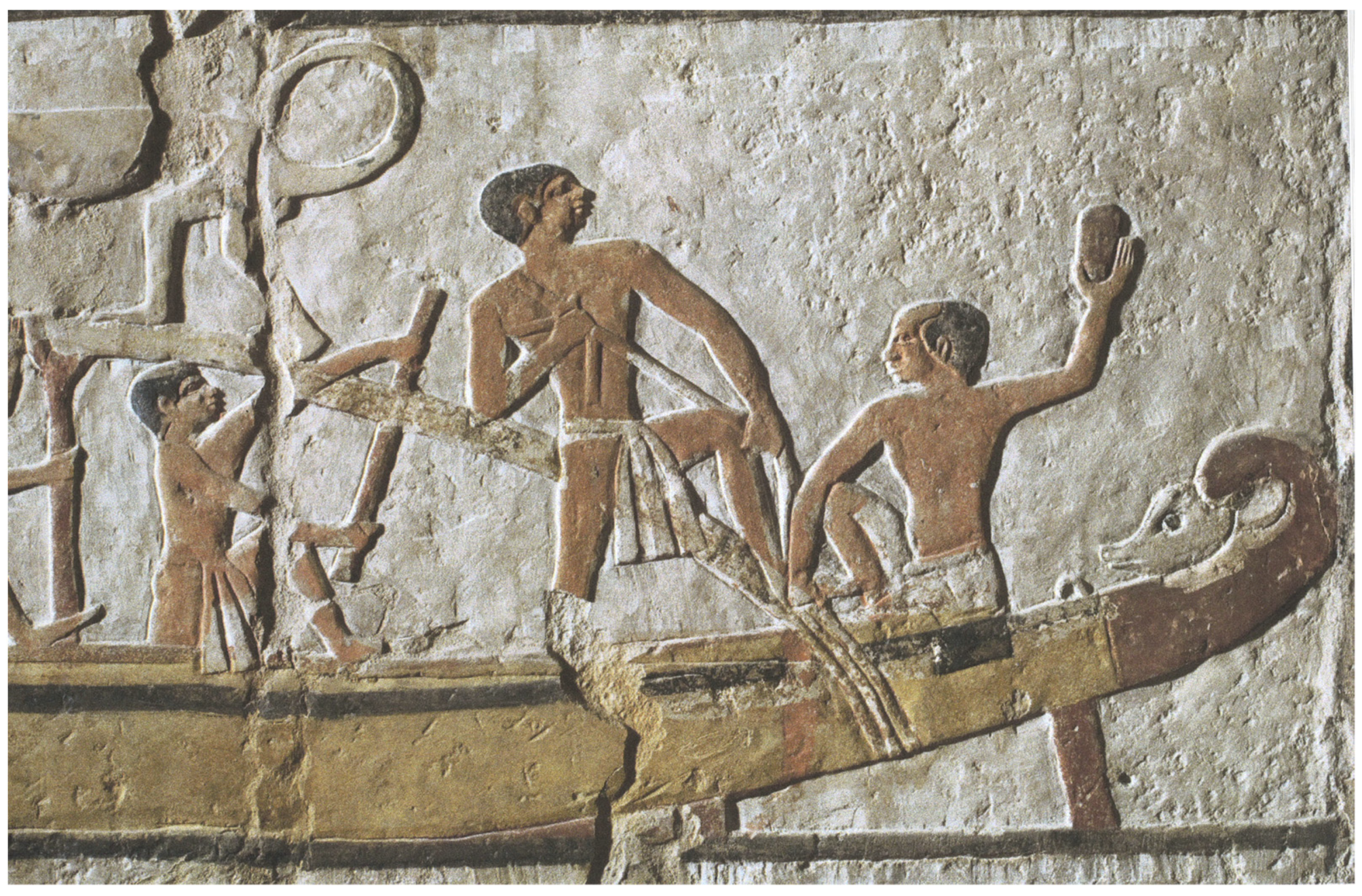

- Hedgehog-head boat being rowed (C)

- Hedgehog-head boat in papyrus-thicket hunting scenes (D)

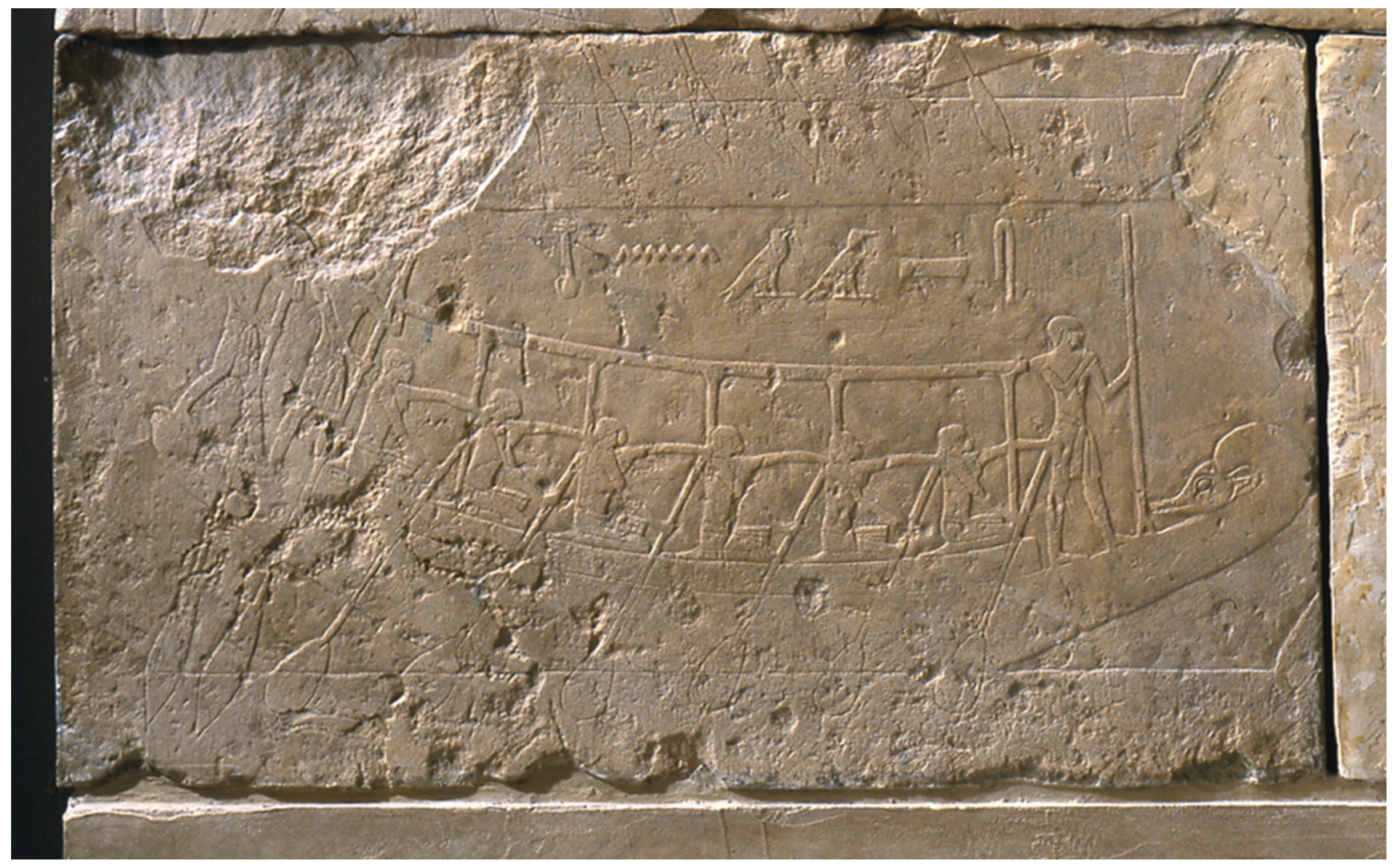

- Hedgehog-head boat as transport vessel (including for offerings) (E)

| Tomb | Theme(s) | Location | Date | Select References23 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Meresankh III (G 7530) | C | Giza | 4th Dynasty | Der Igel no. 46; Dunham and Simpson (1974), pp. 11–12, pl. 3b, 5a. |

| Merib (G 2100-I) | B | Giza (now Berlin ÄM 1107) | 4th–5th Dynasty | Der Igel no. 47; Zorn and Bisping-Isermann (2011), figs 56, 58 (cf. Priese 1984, p. 33 [modern colour reproduction]). |

| Seneb | B | Giza (now Cairo JE 51297) | 4th–5th Dynasty | Der Igel no. 63; Junker (1941), pp. 61–62, fig. 14b, pl. 4a. |

| Iyneferet | D | Giza (now Karlsruhe, Badisches Landesmuseum H 532/1050) | 5th Dynasty | Der Igel no. 66; Schürmann (1983), pl. 6a–b. |

| Nefer [I] (G 4761) | B | Giza | 5th Dynasty | Der Igel no. 59; Junker (1943), p. 59, fig, 14, pp. 61–63, fig. 16. |

| Nesutnefer (G 4970) | C | Giza | 5th Dynasty | Der Igel no. 50; Kanawati (2002), p. 41, pl. 1a, 15, 52, 54. |

| Senenu [I] | E | Giza | 5th Dynasty (?) | Handoussa and Brovarski (2021), p. 156, fig. 70, pl. 180. Giza Archives ID: CBE_VI-105 (context); CBE_VI-107 (detail). |

| Seshathotep [Heti] (G 5150) | C | Giza | 5th Dynasty | Der Igel no. 49; Junker (1934), p. 186 fig. 32; Kanawati (2002), p. 23, pl. 44. |

| Seshemnefer [I] (G 4940) | B | Giza | 5th Dynasty | Der Igel no. 51; Kanawati (2001), pp. 57–58, pl. 34a, 41, 44–45. |

| Kapunisut [Kai] (G 1741) | E | Giza | 5th Dynasty | Tomb only partially published (Giza Archives ID: MFAB_AA2128 (Context); MFAB_AAW3131 [detail]). |

| Kaninisut [I] (G 2155) | B | Giza (now KHM Vienna ÄS 8006) | 5th Dynasty | Der Igel no. 48; Junker (1931), pl. 8; Junker (1934), pl. 9a–b. |

| Akhetmehu (G 2375) | D | Giza | 6th Dynasty | Scene unpublished (Giza Archives ID: A5798_NS; noted in Woods 2015, p. 1903 n. 30) |

| Akhethotep | D, C | Saqqara (now Louvre E 10958) | 5th Dynasty | Der Igel no. 60, no. 65; Ziegler (1993), pp. 79, 132, 137–38, 199. |

| Iymery | C | Saqqara | 5th Dynasty | Tomb unpublished. Tomb owner seated and facing the hedgehog prow, which Harpur notes is an unusual variation. |

| Iyneferet [Shanef] (reused by Idut) | B | Saqqara | 5th Dynasty | Kanawati and Abdel-Raziq (2003), p. 17, pl. 35. |

| Wa’ti | B | Saqqara | 5th Dynasty | Tomb unpublished. Hedgehog-head boat under sail at the south end of the east wall. |

| Nefer and Kahay | A, B | Saqqara | 5th Dynasty | Der Igel no. 52–52a; Moussa and Altenmüller (1977), pp. 26–27, pls 1, 16, 19; Harpur and Scremin (2010), details 169, 177, 195; pp. 310–11 (context photograph 4), 625 (context drawing 72). |

| Niakhkhnum and Khnumhotep | C, C, C, E | Saqqara | 5th Dynasty | Der Igel no. 54; Moussa and Altenmüller (1977), pp. 12, 47, 52, 90f., 106, 109, pls 6, 8, 12, 30, 41, abb. 11. |

| Raemka (D 3) | C | Saqqara (now MMA 08.201.1) | 5th Dynasty | Der Igel no. 58; Hayes (1953), pp. 99–100, fig. 56. |

| Khnumhotep (D 49) | D | Saqqara (now Berlin ÄM 14101) | 5th Dynasty | Der Igel no. 64, pl. 4 (detail); Vandier (1964), pl. 34, fig. 435 (context). |

| Ty (reused by Hemet-Re) (C 15) | C | Saqqara (now Cairo CG 1700, CG 1696) | 5th Dynasty | Shoaib (2014), pp. 12–13, figs 1–2 (context), 16. |

| Ty (D 22) | C, E | Saqqara | 5th Dynasty | Der Igel no. 53–53a; Épron et al. (1939), pls 19, 24, 49. |

| […] | C | Saqqara (?) (now Baltimore WAG 22.87) | 5th Dynasty | Der Igel no. 55; Steindorff (1946), p. 78, no. 263, pl. 50. |

| Irukaptah [Khenu] | C | Saqqara | 5th–6th Dynasty | Der Igel no. 61; McFarlane (2000), p. 51, pls 2a, 2c, 17, 47–48; Harpur and Scremin (2017), p. 64 (detail 72), 68 [detail 78], 179, 181 (details 72, 78). |

| Pernedju | E (?) | Saqqara (now Private Collection) | 6th Dynasty | Galán (2000), pp. 148–50, fig. 2. |

| Fetekty (LS 1) | B | Abusir | 5th Dynasty | Der Igel no. 56; Bárta (2001), pp. 81–85, figs 3.10–3.12. |

| Pepiankh Heri-ib (D 2) | B | Meir | 6th Dynasty | Der Igel no. 62; Kanawati (2012), pl. 82. |

| Khunes | A (?) | Zaweit el-Maiyitin | 5th–6th Dynasty | Der Igel no. 69; Varille (1938), p. 15, fig. 5. Note in this possible example that the head is not yet modelled. |

| Kakhent [I] and Iufi (A 2) | C | El-Hamammiya | 5th–6th Dynasty | Der Igel no. 57; El-Khouli and Kanawati (1990), p. 41, pls 10a, 11a–b, 44. |

| Kakhent [II] (A 3) | A | El-Hamammiya | 5th–6th Dynasty | El-Khouli and Kanawati (1990), p. 66, pl. 69. |

| Owner | Theme(s) | Location | Date | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ankhwedjas | E | Giza (now Louvre E 25369) | 5th–6th Dynasty | Der Igel no. 67; Vandier (1957), p. 149f., pl. 11; Mostafa (1982), pl. 31. |

| Sekhentiuikai | C | Abydos (now Cairo CG 1353) | 6th Dynasty (?) | Der Igel no. 68; Borchardt (1937), pp. 24–25; Mostafa (1982), pl. 30. |

| Owner | Theme(s) | Location | Date | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unknown | B | East of Borg el-Hamam, Wadi Hilal. | 4th–6th Dynasty (?) | ‘Beyond the Borg el-Hamam—the Khufu site’, fig. 9 (https://egyptology.yale.edu/expeditions/current-expeditions/elkab-desert-survey-project/beyond-borg-el-hamam-khufu-site; accessed on 4 January 2022). |

- A small boat with six crew (Figure 6a), with a single steering oar, and rowed among a convoy of ships ferrying an enclosed naos ‘to Sais’, in the entrance portico. The same scene is mirrored on the eastern and western portico walls (Moussa and Altenmüller 1977, pp. 6–8).

- A larger boat with a decorated deck house (Figure 6b; compare Figure 7), rowed by at least ten men, with two steering oars, and carrying the tomb owner and lector priests, located near the false-door. A hieroglyphic caption accompanying the scene captures the speech of the pilot in the boat behind: ‘Keep to starboard! Do not push into our ḥnt’ (Moussa and Altenmüller 1977, p. 91).

- A small boat with a covered canopy and without crew (Figure 6c), which occurs among a list of boats in association with the magazine for sacred oils, and among other boats with decorated prows, including a hare, long-horned and short-horned cattle, and lotus blooms (cf. Altenmüller 1976, p. 29).

5. On the Name of Hedgehogs and the Hedgehog-Head Boat

6. Linking the Two Spheres: Hedgehogs and Hedgehog-Head Boats in Art and Religious Practice

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| Baltimore WAG | Walters Art Museum (formally Gallery), Baltimore. |

| Berlin ÄM | Ägyptisches Museum und Papyrussammlung, Berlin. |

| Cairo CG | Catalogue General, Cairo Museum. |

| Cairo JE | Journal d’Entrée, Cairo Museum. |

| Gardiner | Enumerated sign-list in Gardiner, Alan H. 1957. Egyptian Grammar. Oxford. |

| Hannig I | Hannig, Rainer. 2003. Ägyptisches Wörterbuch I: Altes Reich und Erste Zwischenzeit. Kulturgeschichte der Antiken Welt 98. Mainz. |

| Hannig II | Hannig, Rainer. 2006. Ägyptisches Wörterbuch II: Mittleres Reich und Zweite Zwischenzeit, 2 vols. Kulturgeschichte der Antiken Welt 112. Mainz. |

| LD | Lepsius, Carl Richard. 1897–1913. Denkmäler aus Aegypten und Aethiopien. Leipzig. |

| LGG | Leitz, Christian (ed.) 2002–2003. Lexikon der ägyptischen Götter und Götterbezeichnungen. Orientalia Lovaniensia Analecta 110–116, 129. 8 vols. Leuven. |

| KHM | Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna. |

| MMA | Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York. |

| Paris BnF | Bibliothèque nationale de France, Paris. |

| Wb | Erman, Adolf, and Hermann Grapow (eds). 1926–1961. Wörterbuch der Aegyptischen Sprache. 7 vols. Berlin. |

| 1 | A small number of slate palettes (Petrie’s so-called ‘pelta’ palettes) dating to the mid-4th Millennium BCE (Naqada I through to Naqada IIc–d periods) have been proposed to represent stylised hedgehog-heads by Brovarski (2015), although none of the diagnostic features of hedgehog representation (such as spines or a pointed snout) can be discerned. That they have a zoomorphic form remains questionable. With thanks to Matthew George for discussing the interpretation of these palettes with me. |

| 2 | With thanks to Yvonne Harpur for this observation. |

| 3 | This can be compared to the representation of insects, such as butterflies and grasshoppers (e.g., Evans and Weinstein 2019; Evans and Nazari 2015; Evans 2015, with bibliography). |

| 4 | As Forshaw (2014, p. 30) notes concerning P. Ebers, magical incantations (‘utterances’) were probably expected to accompany most prescriptions including during their preparation, even though they are not specifically listed against every remedy (cf. Popko et al. 2021, pp. 38, 44–46). |

| 5 | Although a curious example of a representation of a swaddled (possibly mummiform) hedgehog with a sun-disc at the Hibis Temple at Kharga Oasis is discussed below (overview: Lippert 2012). |

| 6 | Her name perhaps meaning ‘Praising Isis’ (Sherbiny and Bassir 2014, pp. 174–76), although other readings of the name are possible (Lippert 2012, pp. 789–90). |

| 7 | It is interesting to note that the so-called ‘hedgehog-headdress’ worn by ‘Abaset in the tomb at Fama has been painted with a bright blue pigment (Shaikh Al Arab 2019, p. 89, fig. 5, pp. 91–92), which Shaikh Al Arab suggests imitated lapis lazuli. Another tempting possibility is that this colour referenced the blue hues of faience, of which almost all vessels in the shape of hedgehogs were fashioned from by this period in Pharaonic history. However, because this blue pigment is used extensively elsewhere in the tomb, including in the headdresses of other deities such as the scarab headdress of the god Khepri, it is problematic to argue such a direct connection. |

| 8 | Locusts and grasshoppers, more generally, are associated with periods of agricultural collapse (Latchininsky et al. 2011), and their possible proliferation may have indexed ecological changes at the end of the 3rd Millennium BCE (cf. on beetles: Bárta and Bezděk 2008; on representations of ecological change in this period: Burn 2021). As such, one possible interpretation of a hedgehog hunting invertebrates could be that of a visual metaphor for agricultural prosperity. However, it is also worth noting Evans and Weinstein’s (2019) observation that negative illustrations of invertebrates are often lacking in the artistic corpus for the 3rd Millennium BCE, and ancient Egyptian artists fashioned decorative pendants and other bodily adornments with images of locusts. |

| 9 | However, hedgehogs also seem to have acquired an association with being a ‘sinister and baneful creature’ in ancient Greece (overview: Mackay 2016; cf. in Judaic traditions: Foster 2002, p. 298). |

| 10 | Some theophoric (‘oracular’) personal names given to children may be speculative evidence of the latter (Vittmann 2013, p. 2; Baines 1987, pp. 95–97). |

| 11 | In some places, like Tell Ibrahim Awad, models of shrines themselves were also dedicated (van Haarlem 1998a). |

| 12 | E.g., objects fashioned with iconographic associations with kingship (e.g., falcons, mace-heads, and statues of kings), which perhaps pertained to state-required or state-sponsored ritual (e.g., McNamara 2008; Wengrow 2006, p. 134), may not have been originally dedicated in the same event (nor in the same period) as those which seem to relate to ‘private’ concerns (e.g., Kopp 2020, p. 22; Bussmann 2019, p. 77). |

| 13 | When a hedgehog’s spines are modeled in art of this period, which is not always the case, they can be carved (e.g., in Mereruka, Saqqara: Kanawati et al. 2010, pl. 39 [b]), or indicated in paint through a stippling effect or with brush strokes (e.g., in Khnumhotep II, Beni Hassan: Kanawati and Evans 2014, pl. 36 [b]). An example from the 6th Dynasty tomb of Mehu is described below. |

| 14 | With thanks to Liam McNamara for permission to consult this example in person, and for sharing his thoughts about the object’s possible date and identification. |

| 15 | Votive modeled boats without zoomorphic prows are attested elsewhere, including among the shrine deposits at Elephantine (e.g., Kopp 2018, pp. 107–8, pl. 13 [b–d]; Dreyer 1986, pp. 121–27, figs 35–36, pl. 40), Tell Ibrahim Awad (van Haarlem 2019, p. 53), and Saqqara North (Yoshimura et al. 2005, pp. 371, 373, fig. 9, pl. 52b). An exceptional example from Tell Ibrahim Awad of a ‘company of baboons’ on a boat is unlikely to be related to hedgehog-head boat votives (van Haarlem 2019, p. 53; Belova and Sherkova 2002, pp. 165–77). |

| 16 | 41 were originally published by Dreyer in 1986, to which 6 further examples can be added from more recent publications of material from the temple (Kopp 2018, pp. 106–107, abb. 51, pl. 12d–g, 13a). |

| 17 | In the case of Dahshur, the valley temple of the Bent Pyramid appears to have served the local community as a cult-centre in later periods, including the popular worship of the deceased king Sneferu (Bussmann 2019, p. 77; cf. Kemp 2006, pp. 207–209) and such practices have also been documented at Abusir (Morales 2006). |

| 18 | Droste zu Hülshoff (1980, p. 27 n. 1) notes especially: Aristotle (Historia animalium, 9.6), Plutarch (De sollertia animalium, 28), and Pliny (Historia Naturalis, 8.56). |

| 19 | An exceptional example occurs in the 6th Dynasty tomb of Pepiankh Heri-ib at Meir (Blackman 1924, pl. 16), in which a boat under sail is depicted with hedgehog-heads facing inwards at both prow and stern. |

| 20 | A further example may be a petroglyph from Rod el-Air, Serabit el-Khadim, in South Sinai (Tallet 2012, pl. 58 [doc. 97]), of a boat with a square deckhouse and an animal on a standard that could conceivably be a hedgehog, although Tallet (2012, p. 93) proposed this animal to be an Egyptian mongoose (Herpestes ichneumon). It is difficult to identify the mongoose in Egyptian art with any certainty (cf. Evans 2010b); despite the pointed ears and rounded body that make a hedgehog identification tempting, the length of tail suggests another creature. A further possibility is that the creature on this boat is the jackal- or fox-like Wepwawet, also known to appear on standards emerging from its den (Evans 2011, pp. 104–6, fig. 1). With thanks to Julien Cooper for the reference to the South Sinai corpus. |

| 21 | Kaemsekhem (G 7660), which was included by Altenmüller (2000, p. 4 [Dok. 3]), is excluded here because a hedgehog-head ship cannot be confirmed in this tomb (cf. LD II, 32; ‘G 7660’, http://giza.fas.harvard.edu/sites/1271/full/ [accessed on 5 January 2022]). |

| 22 | I am indebted to Yvonne Harpur for sharing her notes concerning hedgehogs and hedgehog-head boats that occur in tombs at Giza and Saqqara and elsewhere, including the unpublished tombs of Iymery and Wa’ti at Saqqara. |

| 23 | References to Droste zu Hülshoff’s (1980) catalogue are provided in the first instance (abbreviated ‘Der Igel no. [X]’), followed by select references to images of the scenes with hedgehog-head boats, particularly those post-dating Droste zu Hülshoff (1980). In the case of partially published or unpublished tombs from Giza, references to their corresponding photographic ID from the Digital Giza project (giza.fas.harvad.edu) have been provided. |

| 24 | A possible further example is from the tomb of Khunes at Zaweit el-Maiyiten (Varille 1938, p. 15, fig. 5), although in this case the head of the hedgehog is not (yet) modeled. The scene is very similar to that found in Nefer and Kahay at Saqqara (Harpur and Scremin 2010, p. 463, n. 293). |

| 25 | I thank Yvonne Harpur for this observation, which cannot be made out in Altenmüller’s (1998, pl. 69) publication of the scene. The Oxford Expedition to Egypt’s publication of photographic scene details from the tomb of Mehu is forthcoming. |

| 26 | The dating of the tomb of Seneb is unresolved, but it probably falls between the end of the 4th Dynasty and the end of the 5th Dynasty (overview: Woods 2011). |

| 27 | The examples from El-Hamammiya, Zaweit el-Maiyitin, and Meir (noted in Table 1) can be compared to a contemporaneous scene in the 6th Dynasty tomb of Ibi at Deir el-Gebrawi, with two ships under sail in convoy but without a hedgehog-head boat (Davies 1901, pl. 19). |

| 28 | Comparable marsh fowling scenes that may have once included hedgehog-head boats occur in the 5th Dynasty tombs of Werirni (A 25) at el-Sheikh Said (Davies 1901, pl. 5), and possibly also Niankhpepy (Tomb 14) at Zaweit el-Maiyitin (Varille 1938, pl. 5), but in both of these examples the front part of the boat is destroyed. With thanks to Yvonne Harpur for this observation. |

| 29 | |

| 30 | The scene of ships in convoy from the tomb chapel of Irukaptah at Saqqara, which includes a hedgehog-head boat, can be compared with that of the 6th Dynasty official Remni at Saqqara, for example, even though the latter does not include a hedgehog-head boat (Kanawati 2009, pp. 37–38, pl. 38a, 52). A simpler expression of this motif is found on the fragmentary false-door of Pernedju from Saqqara (now in Private Collection) studied by Galán (2000, pp. 148–50); in the case of Pernedju, the choice to place this scene prominently in association with his false-door may be connected to his professional connection to royal boats as ‘Scribe of the Crew’ and ‘Scribe of the enrolment of the boat’s crew’, but contra Galán (2000, p. 150) all of these boat-types are associated with vessels found in non-royal contexts and are probably not royal property. |

| 31 | More generally on the status of Old Kingdom officials in the 5th–6th Dynasties and the boats they may have owned, see Kessler (1987, p. 67f.). |

| 32 | In an early 17th century CE study of ancient Egyptian language by Kircher (1636, p. 165), the word ⲡⲓⲫⲩⲛⲟⲥ is proposed as the Coptic word for hedgehog (followed by the Latin Erinacius), probably to be understood as the definite article ⲡ (p-) followed by a word ⲫⲩⲛⲟⲥ, the etymology of which remains obscure. One possibility is a further combination of definite article ⲡ (p-) plus ὕν(ν)ις (hún(n)is), the Greek word for ‘ploughshare’, proposed to be etymologically connected with the word for ‘hog’ (ὗς) by Plutarch, because its action resembles the rooting of a hog’s snout. It is also possible that Kircher misread ⲡⲓⲫⲩⲛⲟⲥ in a written source for ⲡⲓⲭⲩⲛⲟⲥ, ⲡⲓⲭⲓⲛⲟⲥ, or ⲡⲓⲉⲭⲓⲛⲟⲥ, all of which could be hypothetically analysed as Coptic versions of the ancient Greek name for hedgehog, ἐχῖνος (ekhînos). As the word is not yet known to be attested in extant Coptic language sources, these restorations are speculative. Moreover, Kircher incorrectly paired the word with the Arabic name for a jerboa (يربوع, yarbūʻ), even though the Arabic word for hedgehog (قُنْفُذ, qunfuḏ) is otherwise well attested at this time. With thanks to Michael Zellmann-Rohrer for these remarks on the possible etymology of ⲡⲓⲫⲩⲛⲟⲥ and Kircher’s (mis-)translations of Coptic and Arabic. |

| 33 | On faunal nomenclature: Vernus and Yoyotte (2005, pp. 76–89). A recent study that considers methodological and epistemological issues of zoological categories in past societies: Brémont et al. (2020). On animals in ancient Egyptian art and language: e.g., Thuault (2019); the collected articles in Porcier et al. (2019); Gerke (2017); Evans (2010a, 2015); McDonald (2014); Arnold (2010), cf. earlier Arnold (1994), Houlihan (2002); Osborn and Osbornová (1998). |

| 34 | It is important to note that the actual transcription is ḥ-t-n (cf. Junker 1941, p. 64), although the displacement of hieroglyphic signs within words, especially in Old Kingdom captions, is not unusual. |

| 35 | The possibility that Mnjw, in this instance, could also be the name of the figure close to the caption (e.g., see Mjn.w [sic] in Scheele-Schweitzer 2014, p. 370 [1203]) cannot be wholly excluded, also noted by Altenmüller (2000, p. 7). However, mnjw is extremely common as a word for ‘herdsman’ in Old Kingdom tombs in comparable contexts. |

| 36 | A comparable use of this sign occurs on the north wall of the 4th Dynasty tomb of Rahotep at Meidum (Petrie 1892, pl. 14). |

| 37 | Although see also Altenmüller (2007, pp. 19–20), who draws a hypothetical link between hedgehog-head boats and Khnum through references to Khnum as a ‘ferryman’ in the Pyramid and Coffin Texts; none of these passages make use of the lexeme ḥnt(j). |

| 38 | In addition to the examples collected by Droste zu Hülshoff (1980, pp. 81–92), an exceptional example can be added of a live hedgehog being supported in the palm of an offering bearer in the 6th Dynasty tomb of Kagemni at Saqqara (Harpur and Scremin 2006, p. 241 [379]). This was later re-carved into a covered vessel, but its snout, legs, and curved back are all unmistakable in the relief when closely examined. |

| 39 | I thank Yvonne Harpur for the observation that hedgehogs do not occur among visual or tabulated scenes of offerings in Old Kingdom tombs. On live (and ‘fattened’) gazelles being brought to the tomb and their appearance in offering lists, see e.g., Strandberg (2009, p. 120f.). Fitzenreiter (2009) cautions against overinterpreting the absense (or perhaps even avoidance) of certain animals represented for consumption in Old Kingdom funerary reliefs. In addition to the numerous scenes that reference ritual butchery, the tethering stone in the 6th Dynasty chapel of Mereruka at Saqqara is possibly architectural evidence of this occurring within the tomb chapel (described in Kanawati et al. 2010, p. 39). |

| 40 | See recently, e.g., Thuault (2020), Roth (2017). While falling well outside of the scope of this study, there is an intriguing reference in Aristotle (Historia animalium, 9.6) to some hedgehogs as οἱ δ’ ἐν ταῖς οἰκίαις τρεφóμενοι (‘those kept in the houses’), without further elaboration (trans. Mackay 2016, p. 236, n. 39). Kitchell (2017, p. 191) has proposed that hedgehogs may have been used as ‘pest control’ in ancient houses. |

| 41 | Albeit, rarely attested and primarily in the New Kingdom; e.g., oDeM 1646 (l. [Frg. 4, x+2]); tomb of Seti I (KV 17), Book of the Heavenly Cow (l. 58). |

References

- Adams, Barbara. 1974. Ancient Hierakonpolis. Warminster: Aris and Phillips. [Google Scholar]

- Alexanian, Nicole, and Tomasz Herbich. 2014–2015. The workmen’s barracks south of the Red Pyramid at Dahshur. Mitteilungen des Deutschen Archäologischen Instituts, Abteilung Kairo 70–71: 13–23. [Google Scholar]

- Alexanian, Nicole, Robert Schiestl, and Stephan J. Seidlmayer. 2015. The necropolis of Dahshur: Fourth excavation report spring 2007. Annales du Service des Antiquités de l’Égypte 86: 15–26. [Google Scholar]

- Altenmüller, Hartwig. 1976. Das Ölmagazin im Grab des Hesire in Saqqara (QS 2405). Studien zur Altägyptischen Kultur 4: 1–29. [Google Scholar]

- Altenmüller, Hartwig. 1998. Die Wanddarstellungen im Grab des Mehu in Saqqara. Archäologische Veröffentlichungen, Deutsches Archäologisches Institut, Abteilung Kairo 42. Mainz: Philipp von Zabern. [Google Scholar]

- Altenmüller, Hartwig. 2000. Die Nachtfahrt des Grabherrn im Alten Reich: Zur Frage der Schiffe mit Igelkopfbug. Studien zur Altägyptischen Kultur 28: 1–26. [Google Scholar]

- Altenmüller, Hartwig. 2002a. Der Himmelsaufstieg des Grabherrn: Zu den Szenen des zSS wAD in den Gräbern des Alten Reiches. Studien zur Altägyptischen Kultur 30: 1–42. [Google Scholar]

- Altenmüller, Hartwig. 2002b. Funerary boats and boat pits of the Old Kingdom. Archív Orientální 70: 269–90. [Google Scholar]

- Altenmüller, Hartwig. 2005. Licht und Dunkel, Tag und Nacht: Programmatisches aus der Dekoration der Gräber des Alten Reiches. In Texte und Denkmäler des ägyptischen Alten Reiches. Edited by Stephan J. Seidlmayer. Berlin: Achet, Dr. Norbert Dürring, pp. 9–26. [Google Scholar]

- Altenmüller, Hartwig. 2007. Zur Herkunft und Bedeutung der Schiffe mit Igelkopfbug. Bulletin of the Egyptian Museum 4: 13–22. [Google Scholar]

- Andrews, Carol. 1994. Amulets of ancient Egypt. London: The British Museum Press. [Google Scholar]

- Arnold, Dorothea. 1994. An Egyptian bestiary. The Metropolitan Museum of Art Bulletin 52: 7–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arnold, Dorothea. 2010. Falken, Katzen, Krokodile: Tiere im Alten Ägypten; aus den Sammlungen des Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, und des Ägyptischen Museums Kairo. Zürich: Museum Rietberg. [Google Scholar]

- Aufrère, Sydney, and Marguerite Erroux-Morfin. 2001. Au sujet du hérisson. Aryballes et preparations magiques à base d’extraits tires de cet animal. In Encyclopédie Religieuse de l’Univers Végétal Croyances Phytoreligieuses de l’Égypte Ancienne. Edited by Sydney Aufrère. Montpellier: Université Paul Valéry, Montpellier 3, vol. 2, pp. 521–33. [Google Scholar]

- Baines, John. 1987. Practical religion and piety. Journal of Egyptian Archaeology 73: 79–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baines, John. 1991. Society, morality, and religious practice. In Religion in Ancient Egypt: Gods, Myths, and Personal Practice. Edited by John Baines, Leonard H. Lesko and David P. Silverman. Ithaca: Cornell University Press, London: Routledge, pp. 123–200. [Google Scholar]

- Baines, John. 2001. Egyptian letters of the New Kingdom as evidence for religious practice. Journal of Ancient Near Eastern Religions 1: 1–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baines, John. 2006. Display of magic in Old Kingdom Egypt. In Through a Glass Darkly: Magic, Dreams & Prophecy in Ancient Egypt. Edited by Kasia Szpakowska. Swansea: Classical Press of Wales, pp. 1–32. [Google Scholar]

- Baines, John. 2017. How can we approach Egyptian personal religion of the third millennium? In L’individu Dans la Religion Égyptienne: Actes de la Journée D’études de L’équipe EPHE (EA 4519) “Égypte Ancienne: Archéologie, Langue, Religion”, Paris, 27 Juin 2014. Edited by Christiane Zivie-Coche and Yannis Gourdon. Montpellier: Université Paul-Valéry Montpellier 3, pp. 13–36. [Google Scholar]

- Bárta, Miroslav. 2001. Abusir V: The Cemeteries at Abusir South I. Excavations of the Czech Institute of Egyptology. Praha: Set Out. [Google Scholar]

- Bárta, Miroslav, and Aleš Bezděk. 2008. Beetles and the decline of the Old Kingdom: Climate change in ancient Egypt. In Chronology and Archaeology in Ancient Egypt (the Third Millennium B.C.). Edited by Hana Vymazalová and Miroslav Bárta. Prague: Czech Institute of Egyptology, Faculty of Arts, Charles University in Prague, pp. 214–22. [Google Scholar]

- Belova, Galina A., and Tatiana A. Sherkova. 2002. Ancient Egyptian temple at Tell Ibrahim Awad: Excavations and Discoveries in the Nile Delta / Дpeвнeeгипeтский хpaм в Тeлль Ибpaгим Aвaдe: Pacкoпки и Oткpытия в Дeльтe Нилa. Moscow: Aletheia. [Google Scholar]

- Berger, Michael A. 1992. Predynastic animal-headed boats from Hierakonpolis and Southern Egypt. In The Followers of Horus: Studies Dedicated to Michael Allen Hoffman. Edited by Renée Friedman and Barbara Adams. Oxford: Oxbow Books, pp. 107–20. [Google Scholar]

- Blackman, Aylward M. 1924. The Rock Tombs of Meir. Part IV: The Tomb-Chapel of Pepi’onkh the Middle Son of Sebekḥotpe and Pekhernefert (D, No. 2). Archaeological Survey of Egypt 25. London and Boston: Egypt Exploration Fund. [Google Scholar]

- Borchardt, Ludwig. 1937. Denkmäler des Alten Reiches (außer den Statuen) im Museum von Kairo, Nr. 1295-1808. Teil 1: Text und Tafeln zu Nr. 1295–1541. Catalogue Général des Antiquités Égyptiennes du Musée du Caire. Berlin: Reichsdruckerei. [Google Scholar]

- Brass, Michael. 2018. Early North African cattle domestication and its ecological setting: A reassessment. Journal of World Prehistory 31: 81–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Brémont, Axelle, Yoan Boudes, Simon Thuault, and Meyssa Ben Saad. 2020. Appréhender les catégories zoologiques en anthropologie historique: Enjeux méthodologiques et épistémologiques. Anthropozoologica 55: 73–93. [Google Scholar]

- Brodie, Edmund. 1977. Hedgehogs use toad venom in their own defense. Nature 268: 627–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brodie, Edmund, Edmund Brodie Jr., and Judith Johnson. 1982. Breeding the African hedgehog in captivity. International Zoo Yearbook 22: 195–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brodrick, Mary, and Anna A. Morton. 1899. The tomb of Pepi Ankh (Khua), near Sharona. Proceedings of the Society of Biblical Archaeology 21: 26–33. [Google Scholar]

- Brovarski, Edward. 2015. Petrie’s pelta palettes. In Lotus and Laurel: Studies on Egyptian Language and Religion in Honour of Paul John Frandsen. Edited by Rune Nyord and Kim Ryholt. Copenhagen: Museum Tusculanum Press, pp. 45–54. [Google Scholar]

- Buchholz, Hans-Günter. 1965. Echinos und Hystrix: Igel und Stachelschwein in Frühzeit und Antike. Berliner Jahrbuch für Vor- und Frühgeschichte 5: 66–92. [Google Scholar]

- Budjaj, Aymane, Guillermo Benítez, and Juan Manuel Pleguezuelos. 2021. Ethnozoology among the Berbers: Pre-Islamic practices survive in the Rif (northwestern Africa). Journal of Ethnobiology and Ethnomedicine 17: 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burn, John W. 2021. A River In ‘Drought’? Environment and Cultural Ramifications of Old Kingdom Climate Change. BAR International Series 3036; Oxford: BAR Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Burton, Maurice. 1957. Hedgehog self-anointing. Proceedings of the Zoological Society of London 129: 452–53. [Google Scholar]

- Bussmann, Richard. 2006. Der Kult im frühen Satet-Tempel von Elephantine. In Archäologie und Ritual: Auf der Suche nach der Rituellen Handlung in den Antiken Kulturen Ägyptens und Griechenlands. Edited by Joannis Mylonopoulos and Hubert Roeder. Wien: Phoibos Verlag, pp. 25–36. [Google Scholar]

- Bussmann, Richard. 2011. Local traditions in early Egyptian temples. In Egypt at Its Origins III: Proceedings of the Third International Conference “Origin of the State: Predynastic and Early Dynastic Egypt”, London, UK, 27 July–1 August 2008. Edited by Renée F. Friedman and Peter N. Fiske. Leuven: Peeters, pp. 747–62. [Google Scholar]

- Bussmann, Richard. 2013. The social setting of the temple of Satet in the third millennium. In The First Cataract of the Nile—One Region, Diverse Perspectives. Edited by Stephan Seidlmayer, Dietrich Raue and Philipp Speiser. Mainz: Zabern, pp. 21–34. [Google Scholar]

- Bussmann, Richard. 2015. Changing cultural paradigms: From tomb to temple in the 11th Dynasty. In Proceedings of the Tenth International Congress of Egyptologists, Rhodes, Greece, 22–29 May 2008. Edited by Panagiotis Kousoulis and Nikolaos Lazaridis. Leuven: Peeters, pp. 971–85. [Google Scholar]

- Bussmann, Richard. 2017. Personal piety: An archaeological response. In Company of images: Modelling the Imaginary World of Middle Kingdom Egypt (2000-1500 BC), Proceedings of the International Conference of EPOCHS Project, London, UK, 18–20 September 2014. Edited by Gianluca Miniaci, Marilina Betrò and Stephen Quirke. Leuven: Peeters, pp. 71–91. [Google Scholar]

- Bussmann, Richard. 2019. Practice, meaning and intention: Interpreting votive objects from ancient Egypt. In Perspectives on Lived Religion: Practices–Transmission–Landscape. Papers on archaeology of the Leiden Museum of Antiquities 21. Edited by Nico Staring, Huw Twiston Davies and Lara Weiss. Leiden: Sidestone Press, pp. 73–84. [Google Scholar]

- Ciałowicz, Krzysztof M. 2006. From residence to early temple: The case of Tell el-Farkha. In Archaeology of Early Northeastern Africa: In Memory of Lech Krzyżaniak. Edited by Karla Kroeper, Marek Chłodnicki and Michał Kobusiewicz. Poznan: Archaeological Museum, pp. 917–34. [Google Scholar]

- Cooper, Julien, and Dorian Vanhulle. 2019. Boats and routes: New rock art in the Atbai desert. Sudan & Nubia 23: 3–12. [Google Scholar]

- Creasman, Pearce Paul. 2013. Ship timber and the reuse of wood in ancient Egypt. Journal of Egyptian History 6: 152–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Creasman, Pearce Paul, and Noreen Doyle. 2015. From pit to procession: The diminution of ritual boats and the development of royal burial practices in pharaonic Egypt. Studien zur Altägyptischen Kultur 44: 83–101. [Google Scholar]

- Davies, Norman de Garis. 1901. The rock tombs of Sheikh Saïd. London: Egypt Exploration Fund. [Google Scholar]

- Davies, Norman de Garis. 1953. The temple of Hibis in el Khārgeh Oasis Part III: The decoration. Publications of the Metropolitan Museum of Art Egyptian Expedition 17. Edited by Ludlow S. Bull and Lindsley F. Hall. New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art. [Google Scholar]

- De Dominicis, Danilo. 2019. Unguentari a forma di riccio nel Mediterraneo tra Naukratis e l’Etruria. In Atti del XVII Convegno di Egittologia e Papirologia: Siracusa, 28 Settembre–1 Ottobre 2017. Edited by Anna Di Natale and Corrado Basile. Siracusa: Istituto internazionale del papiro—Museo del papiro “Corrado Basile”, pp. 99–110. [Google Scholar]

- Dreyer, Günter. 1986. Elephantine VIII: Der Tempel der Satet. Die Funde der Frühzeit und des Alten Reiches. Archäologische Veröffentlichungen, Deutsches Archäologisches Institut, Abteilung Kairo 39. Mainz: Philipp von Zabern. [Google Scholar]

- Droste zu Hülshoff, Vera von. 1980. Der Igel im Alten Ägypten. Hildesheimer Ägyptologische Beiträge 11. Hildesheim: Gerstenberg. [Google Scholar]

- Dunham, Dows, and William K. Simpson. 1974. The Mastaba of Queen Mersyankh III. G 7530-7540: Based upon the Excavations and Recordings of the Late George Andrew Reisner and William Stevenson Smith. Museum of Fine Arts—Harvard University Expedition. Giza Mastabas 1. Boston: Museum of Fine Arts. [Google Scholar]

- El Awady, Tarek. 2009. Abusir XVI: Sahure. The Pyramid Causeway: History and Decoration Program in the Old Kingdom. Excavations of the Czech Institute of Egyptology. Prague: Czech Institute of Egyptology, Faculty of Arts, Charles University in Prague. [Google Scholar]

- El-Khouli, Ali, and Naguib Kanawati. 1990. The Old Kingdom Tombs of el-Hammamiya. Australian Centre for Egyptology: Reports 2. Sydney: The Australian Centre for Egyptology. [Google Scholar]

- Épron, Lucienne, François Daumas, Henri Wild, and Georges Goyon. 1939. Le Tombeau de Tî: Dessins et Aquarelles. Le Caire: Institut français d’archéologie orientale. [Google Scholar]

- Esposito, Serena. 2018. Riverboats and seagoing ships: Lexicographical analysis of nautical terms from the sources of the Old Kingdom. In Stories of Globalisation: The Red Sea and the Persian Gulf from Late Prehistory to Early Modernity. Edited by Andrea Manzo, Chiara Zazzaro and Diana Joyce De Falco. Leiden: Brill, pp. 30–52. [Google Scholar]

- Evans, Linda. 2010a. Animal Behaviour in Egyptian Art: Representations of the Natural World in Memphite Tomb Scenes. Australian Centre for Egyptology: Studies 9. Oxford: Aris & Phillips. [Google Scholar]

- Evans, Linda. 2010b. Otter or mongoose? Chewing over evidence in wall scenes. In Egyptian Culture and Society: Studies in Honour of Naguib Kanawati 1. Edited by Alexandra Woods, Ann McFarlane and Susanne Binder. Le Caire: Conseil Suprême des Antiquités, pp. 119–29. [Google Scholar]

- Evans, Linda. 2011. The shedshed of Wepwawet: An artistic and behavioural interpretation. Journal of Egyptian Archaeology 97: 103–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evans, Linda. 2015. Invertebrates in ancient Egyptian art: Spiders, ticks, and scorpions. In Apprivoiser le sauvage/Taming the Wild. Edited by Magali Massiera, Bernard Mathieu and Frédéric Rouffet. Montpellier: Université Paul Valéry Montpellier, vol. 3, pp. 145–57. [Google Scholar]

- Evans, Linda, and Philip Weinstein. 2019. Ancient Egyptians’ atypical relationship with invertebrates. Society & Animals 27: 716–32. [Google Scholar]

- Evans, Linda, and Vazrick Nazari. 2015. Butterflies of ancient Egypt. Journal of the Lepidopterists’ Society 69: 242–67. [Google Scholar]

- Fakhry, Ahmed. 1942. Baḥria Oasis. The Egyptian Deserts. Bulâq: Service des Antiquités de l’Égypte. [Google Scholar]

- Fakhry, Ahmed. 1961. The Valley Temple, Part II: The Finds. The monuments of Sneferu at Dahshur 2. Cairo: General Organisation for Government Printing Offices, Antiquities Department of Egypt. [Google Scholar]

- Fernández Pichel, Abraham I. 2017. La representación zoomorfa de las divinidades egipcias: Yuxtaposición y complementariedad. Polis: Revista de Ideas y Formas Políticas de la Antigüedad Clásica 29: 31–54. [Google Scholar]

- Fitzenreiter, Martin. 2009. On the yonder side of bread and beer: The conceptualization of animal based food in funerary chapels of the Old Kingdom. In Desert Animals in the Eastern Sahara: Statues, Economic Significance, and Cultural Reflection in Antiquity. Edited by Heiko Reimer, Frank Förster, Michael Herb and Nadja Pöllath. Cologne: Heinrich-Barth Institute, pp. 309–40. [Google Scholar]

- Forshaw, Roger. 2014. Before Hippocrates. Healing practices in ancient Egypt. In Medicine, Healing and Performance. Edited by Effie Gemi-Iordanou, Stephen Gordon, Robert Matthew, Ellen McInnes and Rhiannon Pettitt. Oxford: Oxbow, pp. 25–41. [Google Scholar]

- Foster, Benjamin. 2002. Animals in Mesopotamian literature. In A History of the Animal World in the Ancient Near East. Edited by Billie Jean Collins. Leiden: Brill, pp. 271–28. [Google Scholar]

- Galán, José M. 2000. Two Old Kingdom officials connected with boats. Journal of Egyptian Archaeology 86: 145–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gardiner, Alan H. 1923. The Eloquent Peasant. Journal of Egyptian Archaeology 9: 5–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gardiner, Alan H. 1969. The Admonitions of an Egyptian Sage from a Hieratic Papyrus in Leiden (Pap. Leiden 344 recto). Reprinted with Additions and Corrections. Leipzig: J. C. Hinrichs. [Google Scholar]

- Gerke, Sonja. 2017. All creatures great and small—The ancient Egyptian view of the animal world. In Classification from Antiquity to Modern Times: Sources, Methods, and Theories from an Interdisciplinary Perspective. Edited by Tanja Pommerening and Walter Bisang. Berlin and Boston: De Gruyter, pp. 67–100. [Google Scholar]

- Germond, Philippe. 2014–2015. En marge de trois petites représentations de hérissons au Musée d’art et d’histoire de Genève. Bulletin de la Société d’Égyptologie de Genève 30: 35–46. [Google Scholar]

- Ghalioungui, Paul. 1987. The Ebers papyrus: A New English Translation, Commentaries and Glossaries. Cairo: Academy of Scientific Research and Technology. [Google Scholar]

- Graff, Gwenola. 2009. Les peintures sur vases de Nagada I—Nagada II: Nouvelle approche sémiologique de l’iconographie prédynastique. Egyptian Prehistory Monographs 6. Leuven: Leuven University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Gundacker, Roman. 2019. Ist Hcjw-mw ‘Wasserzauber’ ein ‘Älteres Kompositum’? Untersuchungen zu einem terminus technicus der ägyptischenlingua magica. Lingua Aegyptia 27: 77–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Handoussa, Tohfa, and Edward Brovarski. 2021. The Abu Bakr Cemetery at Giza. Wilbour Studies in Egyptology and Assyriology 5. Atlanta: Lockwood Press. [Google Scholar]

- Harpur, Yvonne. 1980. zSS wAD scenes of the Old Kingdom. Göttinger Miszellen 38: 53–61. [Google Scholar]

- Harpur, Yvonne. 1987. Decoration in Egyptian Tombs of the Old Kingdom: Studies in Orientation and Scene Content. Photographs by Paolo J. Scremin. Studies in Egyptology. London and New York: Kegan Paul International. [Google Scholar]

- Harpur, Yvonne, and Paolo Scremin. 2006. The Chapel of Kagemni: Scene Details. Egypt in Miniature 1. Reading and Oxford: Oxford Expedition to Egypt. [Google Scholar]

- Harpur, Yvonne, and Paolo Scremin. 2008. The Chapel of Ptahhotep: Scene Details. Egypt in Miniature 2. Reading and Oxford: Oxford Expedition to Egypt. [Google Scholar]

- Harpur, Yvonne, and Paolo Scremin. 2010. The Chapel of Niankhkhnum and Khnumhotep: Scene Details. Egypt in Miniature 3. Reading and Oxford: Oxford Expedition to Egypt. [Google Scholar]

- Harpur, Yvonne, and Paolo Scremin. 2017. The Chapel of Irukaptah Scene Details and the Chapel of Neferherenptah: Scene Details. Egypt in Miniature 6–7. Reading and Oxford: Oxford Expedition to Egypt. [Google Scholar]

- Hayes, William C. 1953. The Scepter of Egypt: A Background for the Study of the Egyptian Antiquities in the Metropolitan Museum of Art, I. From the Earliest Times to the End of the Middle Kingdom. New York: Harper; Metropolitan Museum of Art. [Google Scholar]

- Hoath, Richard. 2009. A Field Guide to the Mammals of Egypt. Cairo and New York: American University in Cairo Press. [Google Scholar]

- Hornung, Erik, and Elisabeth Staehelin. 1976. Skarabäen und Andere Siegelamulette aus Basler Sammlungen. Mainz: Philipp von Zabern. [Google Scholar]

- Houlihan, Patrick F. 2002. Animals in Egyptian art and hieroglyphs. In A History of the Animal World in the Ancient Near East. Edited by Biller Jean Collins. Leiden: Brill, pp. 97–143. [Google Scholar]

- Huyge, Dirk. 2002. Cosmology, ideology, and personal religious practice in ancient Egyptian rock art. In Egypt and Nubia: Gifts of the Desert. Edited by Renée Friedman. London: British Museum Press, pp. 192–206. [Google Scholar]

- Ikram, Salima. 1995. Choice Cuts: Meat Production in Ancient Egypt. Orientalia Lovaniensia Analecta 69. Leuven: Peeters. [Google Scholar]

- Jones, Dilwyn. 1988. A Glossary of Ancient Egyptian Nautical Titles and Terms. Studies in Egyptology. London and New York: Kegan Paul International. [Google Scholar]

- Jones, Dilwyn. 1995. Boats. Egyptian Bookshelf. London: British Museum Press. [Google Scholar]

- Junker, Hermann. 1931. The Offering Room of Prince Kaninisut [English Edition]. Collections of the Museum of Fine Arts, Vienna 14. Vienna: Kunsthistorisches Museum. [Google Scholar]

- Junker, Hermann. 1934. Gîza II: Bericht über die von der Akademie der Wissenschaften in Wien auf gemeinsame Kosten mit Dr. Wilhelm Pelizaeus Unternommenen Grabungen auf dem Friedhof des Alten Reiches bei den Pyramiden von Gîza. Die Maṣṭabas der Beginnenden V. Dynastie auf dem Westfriedhof. Akademie der Wissenschaften in Wien, Philosophisch-Historische Klasse 70 (3). Wien: Hölder-Pichler-Tempsky. [Google Scholar]

- Junker, Hermann. 1940. Gîza IV: Bericht über die von der Akademie der Wissenschaften in Wien auf Gemeinsame Kosten Mit Dr. Wilhelm Pelizaeus Unternommen Grabungen auf dem Friedhof des Alten Reichs bei den Pyramiden von Gîza. Die Maṣṭaba des KAjmanx (Kai-em-anch). Österreichische Akademie der Wissenschaften, Denkschriften der Philosophisch-Historischen Klasse 71 (1). Wien and Leipzig: Hölder-Pichler-Tempsky. [Google Scholar]

- Junker, Hermann. 1941. Gîza V: Bericht über die von der Akademie der Wissenschaften in Wien auf Gemeinsame Kosten mit Dr. Wilhelm Pelizaeus Unternommen Grabungen auf dem Friedhof des Alten Reichs bei den Pyramiden von Gîza. Die Maṣṭabas des Cnb (Seneb) und die Umliegenden Gräber. Österreichische Akademie der Wissenschaften, Denkschriften der Philosophisch-Historischen Klasse 71 (2). Wien: Hölder-Pichler-Tempsky. [Google Scholar]

- Junker, Hermann. 1943. Gîza VI: Bericht über die von der Akademie der Wissenschaften in Wien auf Gemeinsame Kosten mit Dr. Wilhelm Pelizaeus Unternommen Grabungen auf dem Friedhof des Alten Reichs bei den Pyramiden von Gîza. Die Maṣṭaba des Nfr (Nefer), Kdfjj (Kedfi), Kꜣhjf (Kahjef) und die westlich Anschließenden Grabanlagen. Österreichische Akademie der Wissenschaften, Denkschriften der Philosophisch-Historischen Klasse 72 (1). Wien: Hölder-Pichler-Tempsky. [Google Scholar]

- Kanawati, Naguib. 2001. Tombs at Giza. Volume I: Kaiemankh (G4561) and Seshemnefer I (G4940). Australian Centre for Egyptology: Reports 16. Warminster: Aris & Phillips. [Google Scholar]

- Kanawati, Naguib. 2002. Tombs at Giza. Volume II: Seshathetep/Heti (G5150), Nesutnefer (G4970) and Seshemnefer II (G5080). Australian Centre for Egyptology: Reports 18. Warminster: Aris & Phillips. [Google Scholar]

- Kanawati, Naguib. 2009. The Teti Cemetery at Saqqara. Volume IX: The tomb of Remni. Australian Centre for Egyptology: Reports 28. Warminster: Aris and Phillips. [Google Scholar]

- Kanawati, Naguib. 2012. The Cemetery of Meir. Volume I: The Tomb of Pepyankh the Middle. Australian Centre for Egyptology: Reports 31. Oxford: Aris & Phillips. [Google Scholar]

- Kanawati, Naguib, Alexandra Woods, Sameh Shafik, and Effy Alexakis. 2010. Mereruka and His Family, Part III.1-2: The Tomb of Mereruka. Australian Centre for Egyptology: Reports 29–30. Oxford: Aris and Phillips. [Google Scholar]

- Kanawati, Naguib, and Linda Evans. 2014. Beni Hassan. Volume I: The Tomb of Khnumhotep II. Australian Centre for Egyptology: Reports 36. Oxford: Aris and Phillips. [Google Scholar]

- Kanawati, Naguib, and Mahmoud Abdel-Raziq. 2003. The Unis Cemetery at Saqqara. Volume II: The Tombs of Iynefert and Ihy (Reused by Idut). Australian Centre for Egyptology: Reports 19. Warminster: Aris & Phillips. [Google Scholar]

- Kawai, Nozomu. 2011. An early cult centre at Abusir-Saqqara? Recent discoveries at a rocky outcrop in north-west Saqqara. In Egypt at Its Origins III: Proceedings of the Third International Conference “Origin of the State: Predynastic and Early Dynastic Egypt”, London, UK, 27 July–1 August 2008. Edited by Renée F. Friedman and Peter N. Fiske. Leuven: Peeters, pp. 801–28. [Google Scholar]

- Kees, Hermann. 1921. Studien zur Aegyptischen Provinzialkunst. Leipzig: Hinrichs. [Google Scholar]

- Kemp, Barry J. 2006. Ancient Egypt: Anatomy of a Civilization, 2nd Revised ed. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Kessler, Dieter. 1987. Zur Bedeutung der Szenen des täglichen Lebens in den Privatgräbern (1): Die Szenen des Schiffsbaues und der Schiffahrt. Zeitschrift für ägyptische Sprache und Altertumskunde 114: 59–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kircher, Athanasius. 1636. Lingua Aegyptiaca Restituta. Rome: L. Grignani for sumptibus Hermanni Scheus. [Google Scholar]

- Kitchell, Kenneth F. 2017. ‘Animal Literacy’ and the Greeks: Philoctetes the Hedgehog and Dolon the Weasel. In Interactions between Animals and Humans in Graeco-Roman Antiquity. Edited by Thorsten Fögen and Edmund Thomas. Berlin and Boston: De Gruyter, pp. 183–204. [Google Scholar]

- Kopp, Peter. 2013. Votive aus dem Schutt: Der Satet-Tempel auf Elephantine und die Stadterweiterung der 6. Dynastie. In Sanktuar und Ritual: Heilige Plätze im Archäologischen Befund. Edited by Iris Gerlach and Dietrich Raue. Rahden: VML, Marie Leidorf, pp. 307–20. [Google Scholar]

- Kopp, Peter. 2018. Elephantine XXIV: Funde und Befunde aus der Umgebung des Satettempels. Grabungen 2006–2009. Archäologische Veröffentlichungen, Deutsches Archäologisches Institut, Abteilung Kairo 104. Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz. [Google Scholar]

- Kopp, Peter. 2020. Elephantine IX: Der Tempel der Satet. Die Funde des Späten Alten bis Neuen Reichs. Archäologische Veröffentlichungen, Deutsches Archäologisches Institut, Abteilung Kairo 41. Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz. [Google Scholar]

- Kremler, Joylene. 2016. The persistence of style: Frog votive figures from Elephantine. Mitteilungen des Deutschen Archäologischen Instituts, Abteilung Kairo 72: 127–34. [Google Scholar]

- Lacovara, Peter. 2015. The Menkaure valley temple settlement revisited. Bulletin of the Egyptological Seminar 19: 447–54. [Google Scholar]

- Landström, Björn. 1970. Ships of the Pharaohs: 4000 Years of Egyptian Shipbuilding. Architectura Navalis. London: Allen & Unwin. [Google Scholar]

- Lankester, Francis D. 2013. Desert Boats: Predynastic and Pharaonic era Rock-Art in Egypt’s Central Eastern Desert. Distribution, Dating and Interpretation. BAR International Series 2544; Oxford: Archaeopress. [Google Scholar]

- Lankester, Francis D. 2016. Predynastic Egyptian rock art as evidence for early elites’ rite of passage. Afrique: Archéologie & Arts 12: 81–92. [Google Scholar]

- Lashien, Miral. 2009. The so-called pilgrimage in the Old Kingdom: Its destination and significance. The Bulletin of the Australian Centre for Egyptology 20: 87–106. [Google Scholar]

- Latchininsky, Alexandre, Gregory Sword, Michael Sergeev, Maria Marta Cigliano, and Michel Lecoq. 2011. Locusts and grasshoppers: Behavior, ecology, and biogeography. Psyche: A Journal of Entomology 2011: 578327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lehner, Mark, and Zahi Hawass. 2017. Giza and the Pyramids: The Definitive History. London: Thames & Hudson. [Google Scholar]

- Leonard, Albert. 2000. Why a Hedgehog? In The Archaeology of Jordan and Beyond. Edited by Lawrence E. Stager, Joseph A. Greene and Michael D. Coogan. Leiden: Brill, pp. 310–16. [Google Scholar]

- Lippert, Sandra L. 2012. Stachelschwein, Igel und Schmetterlingspuppe. In ‘Parcourir L’éternité’: Hommages à Jean Yoyotte 2. Edited by Christiane Zivie-Coche and Ivan Guermeur. Turnhout: Brepols, pp. 777–99. [Google Scholar]

- Luiselli, Maria M. 2012. Die ‘persönliche Frömmigkeit’ in der Ägyptologie: Definition(en), Themen, Terminologie, Forschungsansätze, Ausblicke. In Persönliche Frömmigkeit: Funktion und Bedeutung Individueller Gotteskontakte im Interdisziplinären Dialog; Akten der Tagung am Archäologischen Institut der Universität Hamburg (25–27 November 2010). Edited by Wiebke Friese, Anika Greve, Kathrin Kleibl and Kristina Lahn. Münster: Lit, pp. 37–50. [Google Scholar]

- Mackay, E. Anne. 2016. The baneful hedgehog of ancient Greece. In Rich and Great: Studies in Honour of Anthony J. Spalinger on the Occasion of his 70th Feast of Thoth. Edited by Renata Landgráfová and Jana Mynářová. Prague: Charles University, Faculty of Arts, pp. 233–37. [Google Scholar]

- Mark, Samuel. 2013. Graphical reconstruction and comparison of royal boat iconography from the causeway of the Egyptian king Sahure (c. 2487–2475 BC). International Journal of Nautical Archaeology 42: 270–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maydana, Sebastián F. 2021. Bringing the desert to the Nile: Some thoughts on a predynastic terracotta model. Archéo-Nil 31: 61–80. [Google Scholar]

- McDonald, Angela. 2014. Animals in Egypt. In Oxford Handbooks Online. Edited by Gordon Lindsay Campbell. Glasgow: University of Glasgow. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McFarlane, Ann. 2000. The Unis Cemetery at Saqqara. Volume I: The Tomb of Irukaptah. Australian Centre for Egyptology: Reports 15. Warminster: Aris & Phillips. [Google Scholar]

- McNamara, Liam. 2008. The revetted mound at Hierakonpolis and early kingship: A re-interpretation. In Egypt at Its Origins II: Proceedings of the International Conference “Origin of the State. Predynastic and Early Dynastic Egypt”, Toulouse, France, 5–8 September 2005. Edited by Béatrix Midant-Reynes and Yann Tristant. Leuven: Peeters, pp. 901–36. [Google Scholar]

- Meyer, Gudrun. 1990. Das Hirtenlied in den Privatgräbern des Alten Reiches. Studien zur Altägyptischen Kultur 17: 235–84. [Google Scholar]

- Mogensen, Maria. 1921. Le mastaba égyptien de la Glyptothèque Ny Carlsberg. Copenhague: Gyldendalske Boghandel—Nordisk Forlag. [Google Scholar]

- Morales, Antonio J. 2006. Traces of official and popular veneration to Nyuserra Iny at Abusir: Late Fifth Dynasty to Middle Kingdom. In Abusir and Saqqara in the Year 2005: Proceedings of the Conference Held in PRAGUE (June 27 July 5, 2005). Edited by Miroslav Bárta, Filip Coppens and Jaromír Krejčí. Prag: Czech Institute of Egyptology, Faculty of Arts, Charles University in Prague, pp. 311–41. [Google Scholar]

- Mostafa, Maha M. F. 1982. Untersuchungen zu Opfertafeln im Alten Reich. Hildesheimer Ägyptologische Beiträge 17. Hildesheim: Gerstenberg. [Google Scholar]

- Moussa, Ahmed M., and Hartwig Altenmüller. 1977. Das Grab des Nianchchnum und Chnumhotep. Archäologische Veröffentlichungen, Deutsches Archäologisches Institut, Abteilung Kairo 21. Mainz: Zabern. [Google Scholar]

- Ogdon, Jorge R. 1987. Studies in ancient Egyptian magical thought III: Knots and ties. Notes on ancient ligatures. Discussions in Egyptology 7: 29–36. [Google Scholar]

- Ogdon, Jorge R. 1989. Studies in ancient Egyptian magical thought IV: An analysis of the ‘technical’ language in the anti-snake magical spells of the Pyramid Texts (PT). Discussions in Egyptology 13: 59–71. [Google Scholar]

- Osborn, Dale J., and Helmy Ibrahim. 1980. The Contemporary Land Mammals of Egypt (Including Sinai). Chicago: Field Museum of Natural History. [Google Scholar]

- Osborn, Dale J., and Jana Osbornová. 1998. The Mammals of Ancient Egypt. The Natural History of Egypt 4. Warminster: Aris & Phillips. [Google Scholar]

- Parkinson, Richard B. 2002. Poetry and Culture in Middle Kingdom Egypt: A Dark Side to Perfection. Athlone Publications in Egyptology and Ancient Near Eastern Studies. London and New York: Continuum. [Google Scholar]

- Parkinson, Richard B. 2012. The Tale of the Eloquent Peasant: A Reader’s Commentary. Lingua Aegyptia, Studia Monographica 10. Hamburg: Widmaier. [Google Scholar]

- Petrie, W. M. Flinders. 1892. Medum. London: Nutt. [Google Scholar]

- Petrie, W. M. Flinders. 1901. Diospolis Parva: The Cemeteries of Abadiyeh and Hu 1898–99. London: Egypt Exploration Fund. [Google Scholar]

- Petrie, W. M. Flinders, Edward R. Ayrton, Charles T. Currelly, and Arthur E. Weigall. 1902–1904. Abydos. Memoir of the Egypt Exploration Fund 22; 24; 25. London: Egypt Exploration Fund. [Google Scholar]

- Pinch, Geraldine. 1993. Votive Offerings to Hathor. Oxford: Griffith Institute; Ashmolean Museum. [Google Scholar]

- Pinch, Geraldine, and Elizabeth A. Waraksa. 2009. Votive practices. In UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology. Edited by Jacco Dieleman and Willeke Wendrich. Available online: http://digital2.library.ucla.edu/viewItem.do?ark=21198/zz001nfbgg (accessed on 20 November 2021).

- Popko, Lutz, Ulrich Johannes Schneider, and Reinhold Scholl. 2021. Papyrus Ebers: Die größte Schriftrolle zur Altägyptischen Heilkunst. Darmstadt: Wbg Edition. [Google Scholar]

- Porcier, Stéphanie, Salima Ikram, and Stéphane Pasquali. 2019. Creatures of Earth, Water, and Sky: Essays on Animals in Ancient Egypt and Nubia. Leiden: Sidestone. [Google Scholar]

- Priese, Karl-Heinz. 1984. Die Opferkammer des Merib. Berlin: Ägyptisches Museum. [Google Scholar]

- Quack, Joachim F. 2002. Some Old Kingdom execration figurines from the Teti Cemetery. The Bulletin of the Australian Centre for Egyptology 13: 149–60. [Google Scholar]

- Quibell, James E., and Frederick W. Green. 1900–1902. Hierakonpolis. British School of Archaeology in Egypt and Egyptian Research Account 4–5. London: Bernard Quaritch. [Google Scholar]

- Quirke, Stephen. 2015. Exploring Religion in Ancient Egypt. Blackwell Ancient Religions. Chichester and Malden: Wiley Blackwell. [Google Scholar]

- Reeve, Nicholas. 1994. Hedgehogs. London: Poyser. [Google Scholar]

- Roth, Ann Macy. 2011. Objects, animals, humans, and hybrids: The evolution of early Egyptian representations of the divine. In Dawn of Egyptian Art. Edited by Diana Craig Patch. New York and London: Metropolitan Museum of Art, pp. 194–201. [Google Scholar]

- Roth, Ann Macy. 2017. Fear of hieroglyphs: Patterns of suppression and mutilation in Old Kingdom burial chambers. In Essays for the Library of Seshat: Studies Presented to Janet H. Johnson on the Occasion of her 70th Birthday. Edited by Robert Ritner. Chicago: The Oriental Institute of the University of Chicago, pp. 291–310. [Google Scholar]

- Rushdy, Mahmud. 1911. Some notes on the hedgehog. Annales du Service des Antiquités de l’Égypte 11: 181–82. [Google Scholar]

- Scheele-Schweitzer, Katrin. 2014. Die Personennamen des Alten Reiches: Altägyptische Onomastik Unter lexikographischen und Sozio-Kulturellen Aspekten. Philippika 28. Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz. [Google Scholar]

- Schürmann, Wolfgang. 1983. Die Reliefs aus dem Grab des Pyramidenvorstehers Ii-Nefret. Karlsruhe: C. F. Müller. [Google Scholar]

- Seidlmayer, Stephan J. 1997. Stil und Statistik: Die Datierung dekorierter Gräber des Alten Reiches—ein Problem der Methode. In Archäologie und Korrespondenzanalyse: Beispiele, Fragen, Perspektiven. Edited by Johannes Müller and Andreas Zimmermann. Espelkamp: Marie Leidorf, pp. 17–51. [Google Scholar]

- Shaikh Al Arab, Walid. 2019. The hedgehog goddess Abaset. Papyrologica Lupiensia 28: 81–102. [Google Scholar]

- Sherbiny, Hend, and Hussein Bassir. 2014. The representation of the hedgehog goddess Abaset at Bahariya Oasis. Journal of the American Research Center in Egypt 50: 171–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shoaib, Waheid M. 2014. Unpublished chapel of Ty in the Egyptian Museum (CG 1380, 1696, 1699, 1700–01). Journal of the American Research Center in Egypt 50: 1–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Snedegar, Keith. 2008. Astronomy in Sub-Saharan Africa. In Encyclopaedia of the History of Science, Technology, and Medicine in Non-Western Cultures. Edited by Helain Selin. Berlin and Heidelberg: Springer. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spieser, Cathy. 2001. Serket, protectrice des enfants à naître et des défunts à renaître. Revue d’Égyptologie 52: 251–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steindorff, George. 1946. Catalogue of the Egyptian Sculpture in the Walters Art Gallery. Baltimore: Walters Art Gallery. [Google Scholar]

- Stephens, Michael Allen. 2012. A Categorisation and Examination of Egyptian Ships and Boats from the Rise of the Old to the End of the Middle Kingdoms. BAR International Series 2358; Oxford: Archaeopress. [Google Scholar]

- Strandberg, Åsa. 2009. The Gazelle in Ancient Egyptian Art: Image and Meaning. Uppsala Studies in Egyptology 6. Uppsala: Uppsala University. [Google Scholar]

- Tallet, Pierre. 2012. La Zone Minière Pharaonique du Sud-Sinaï—I: Catalogue Complémentaire des Inscriptions du Sinaï. Mémoires publiés par les membres de l’Institut français d’archéologie orientale 130. Le Caire: Institut français d’archéologie orientale. [Google Scholar]

- Tavares, Ana. 2014. Prickly protection: Sailing in a hedgehog boat. AERAgram 15: 36. [Google Scholar]

- Tavares, Ana, Daniel Jones, Freya Sadarangani, and Hanan Mahmoud. 2014. Excavations east of the Khentkawes Town in Giza: A preliminary site report. Bulletin de l’Institut Français d’Archéologie Orientale 114: 519–61. [Google Scholar]

- Thuault, Simon. 2019. Animal categorisation during the Old Kingdom: Lexicography, hieroglyphs and iconography. In Old Kingdom Art and Archaeology 7: Proceedings of the International Conference; Università degli studi di Milano, Milan, Italy, 3–7 July 2017. Edited by Patrizia Piacentini and Alessio Delli Castelli. Milano: Pontremoli, pp. 322–31. [Google Scholar]

- Thuault, Simon. 2020. L’iconicité des hiéroglyphes égyptiens: La question de la mutilation. Zeitschrift für ägyptische Sprache und Altertumskunde 147: 106–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tjusi, Asuka. 2016. The depiction of Muslims in the miracles of Anba Barsauma al-Uryan. In Studies in Coptic Culture: Transmission and Interaction. Edited by Mariam Ayad. Oxford: American University in Cairo Press, pp. 65–77. [Google Scholar]

- Tooley, Angela M. 1995. Egyptian Models and Scenes. Shire Egyptology 22. Princes Risborough: Shire Publications. [Google Scholar]

- van Haarlem, Willem. 1996. A remarkable ‘hedgehog-ship’ from Tell Ibrahim Awad. Journal of Egyptian Archaeology 82: 197–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Haarlem, Willem. 1998a. Archaic shrine models from Tell Ibrahim Awad. Mitteilungen des Deutschen Archäologischen Instituts, Abteilung Kairo 54: 183–85. [Google Scholar]

- van Haarlem, Willem. 1998b. The excavations at Tell Ibrahim Awad (Eastern Nile Delta): Recent results. In Proceedings of the Seventh International Congress of Egyptologists, Cambridge, UK, 3–9 September 1995. Edited by Chris Eyre. Leuven: Peeters, pp. 509–13. [Google Scholar]

- van Haarlem, Willem. 2019. Temple Deposits in Early Dynastic Egypt: The Case of Tell Ibrahim Awad. BAR International Series 2931; Oxford: BAR Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- van Walsem, René. 2005. Iconography of Old Kingdom Elite Tombs: Analysis and Interpretation, Theoretical and Methodological Aspects. Mededelingen en Verhandelingen van het Vooraziatisch-Egyptisch Genootschap “Ex Oriente Lux” 35. Dudley: Peeters. [Google Scholar]

- van Walsem, René. 2006. Sense and sensibility: On the analysis and interpretation of the iconography programmes in four Old Kingdom elite tombs. In Dekorierte Grabanlagen im Alten Reich: Methodik und Interpretation. Edited by Martin Fitzenreiter and Michael Herb. London: Golden House Publications, pp. 277–332. [Google Scholar]

- Vandier, Jacques. 1957. Le groupe et la table d’offrandes d’Ankhoudjès. Revue D’égyptologie 11: 145–55. [Google Scholar]

- Vandier, Jacques. 1964. Manuel D’archéologie Égyptienne, Tome IV: Bas-Reliefs et Peintures—Scènes de la vie Quotidienne. Paris: Éditions A. et J. Picard et Cie. [Google Scholar]

- Vanhulle, Dorian. 2018a. Preliminary observations on some Naqadian boat models: A glimpse of a discrete ideological process in pre-pharaonic arts. In Desert and the Nile: Prehistory of the Nile Basin and the Sahara. Papers in Honour of Fred Wendorf. Edited by Jacek Kabaciński, Marek Chłodnicki, Michał Kobusiewicz and Małgorzata Winiarska-Kabacińska. Poznań: Poznań Archaeological Museum, pp. 289–312. [Google Scholar]

- Vanhulle, Dorian. 2018b. Boat symbolism in predynastic and early dynastic Egypt: An ethno-archaeological approach. Journal of Ancient Egyptian Interconnections 17: 173–87. [Google Scholar]

- Varille, Alexandre. 1938. La Tombe de Ni-Ankh-Pepi à Zâouyet el-Mayetîn. Mémoires publiés par les membres de l’Institut français d’archéologie orientale 70. Le Caire: Institut français d’archéologie orientale. [Google Scholar]

- Vassilika, Eleni. 1995. Egyptian Art. Fitzwilliam Museum Handbooks. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Verner, Miroslav. 1992. Funerary boats of Neferirkare and Raneferef. In The Intellectual Heritage of Egypt: Studies Presented to László Kákosy by Friends and Colleagues on the Occasion of His 60th Birthday. Edited by Ulrich Luft. Budapest: Chaire d’Égyptologie, pp. 587–602. [Google Scholar]

- Vernus, Pascal, and Jean Yoyotte. 2005. Bestiaire des Pharaons. Paris: Agnès Viénot; Perrin. [Google Scholar]

- Vinson, Steve. 1994. Egyptian Boats and Ships. Shire Egyptology 20. Princes Risborough: Shire Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Vittmann, Günther. 2013. Personal names: Function and significance. In UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology. Edited by Elizabeth Frood, Jacco Dieleman and Willeke Wendrich. Available online: http://digital2.library.ucla.edu/viewItem.do?ark=21198/zz002dwqr7 (accessed on 20 November 2021).

- Webb, Virginia. 1978. Archaic Greek faience: Miniature Scent Bottles and Related Objects from East Greece, 650–500 B.C. Warminster: Aris and Phillips. [Google Scholar]

- Wegner, Josef. 2017. A royal boat burial and watercraft tableau of Egypt’s 12th Dynasty (c.1850 BCE) at South Abydos. International Journal of Nautical Archaeology 46: 5–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weiss, Lara. 2012. Individuum und Gemeinschaft: Methodologische Überlegungen zur Persönlichen Frömmigkeit. In Sozialisationen: Individuum—Gruppe—Gesellschaft: Beiträge des Ersten Münchner Arbeitskreises Junge Aegyptologie (MAJA 1), 3. bis 5.12.2010. Edited by Gregor Neunert, Kathrin Gabler and Alexandra Verbovsek. Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz, pp. 187–205. [Google Scholar]

- Wendorf, Fred, and Romuald Schild. 2001. Conclusions. In Holocene Settlement of the Egyptian Sahara, Volume 1: The Archaeology of Nabta Playa. Edited by Fred Wendorf and Romuald Schild. New York: Kluwer Academic/Plenum, pp. 648–75. [Google Scholar]

- Wengrow, David. 2006. The Archaeology of Early Egypt: Social Transformations in North-East Africa, 10,000 to 2650 BC. Cambridge World Archaeology. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Wildung, Dietrich. 2011. Tierbilder und Tierzeichen im Alten Ägypten. Berlin and München: Deutscher Kunstverlag. [Google Scholar]

- Wilkinson, Toby. 1999. Early Dynastic Egypt. London and New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Woods, Alexandra. 2011. zšš wꜣḏ scenes of the Old Kingdom revisited. In Old Kingdom, New Perspectives: Egyptian Art and Archaeology 2750-2150 BC. Edited by Nigel Strudwick and Helen Strudwick. Oxford: Oxbow Books, pp. 314–19. [Google Scholar]

- Woods, Alexandra. 2015. Five significant features in Old Kingdom spear-fishing and fowling scenes. In Proceedings of the Tenth International Congress of Egyptologists. Edited by Panagiotis Kousoulis and Nikolaos Lazaridis. Leuven: Peeters, pp. 1897–910. [Google Scholar]

- Yoshimura, Sakuji, Nozomu Kawai, and Hiroyuki Kashiwagi. 2005. A sacred hillside at northwest Saqqara: A preliminary report on the excavations 2001–2003. Mitteilungen des Deutschen Archäologischen Instituts, Abteilung Kairo 61: 361–402. [Google Scholar]

- Yoyotte, Jean. 1960. Les pèlerinages dans l’Égypte ancienne. In Les Pèlerinages: Égypte Ancienne, Israël, Islam, Perse, Inde, Tibet, Indonésie, Madagascar, Chine, Japon. Anonymous Editor. Paris: Éditions du Seuil, pp. 17–74. [Google Scholar]

- Ziegler, Christiane. 1993. Le Mastaba D’akhethetep: Une Chapelle Funéraire de l’Ancien Empire. Paris: Editions de la Réunion des Musées Nationaux. [Google Scholar]

- Zorn, Olivia. 2009. Die Opferkammer des Merib. Sokar 19: 38–45. [Google Scholar]

- Zorn, Olivia, and Dana Bisping-Isermann. 2011. Die Opferkammern im Neuen Museum Berlin. Berlin: Michael Haase. [Google Scholar]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Hamilton, J.C.F. Hedgehogs and Hedgehog-Head Boats in Ancient Egyptian Religion in the Late 3rd Millennium BCE. Arts 2022, 11, 31. https://doi.org/10.3390/arts11010031

Hamilton JCF. Hedgehogs and Hedgehog-Head Boats in Ancient Egyptian Religion in the Late 3rd Millennium BCE. Arts. 2022; 11(1):31. https://doi.org/10.3390/arts11010031

Chicago/Turabian StyleHamilton, Julia Clare Francis. 2022. "Hedgehogs and Hedgehog-Head Boats in Ancient Egyptian Religion in the Late 3rd Millennium BCE" Arts 11, no. 1: 31. https://doi.org/10.3390/arts11010031

APA StyleHamilton, J. C. F. (2022). Hedgehogs and Hedgehog-Head Boats in Ancient Egyptian Religion in the Late 3rd Millennium BCE. Arts, 11(1), 31. https://doi.org/10.3390/arts11010031