The Last Flemish Primitive: Jan Vercruysse’s Self-Fashioning of Artisthood and National Identity

Abstract

:1. Introduction

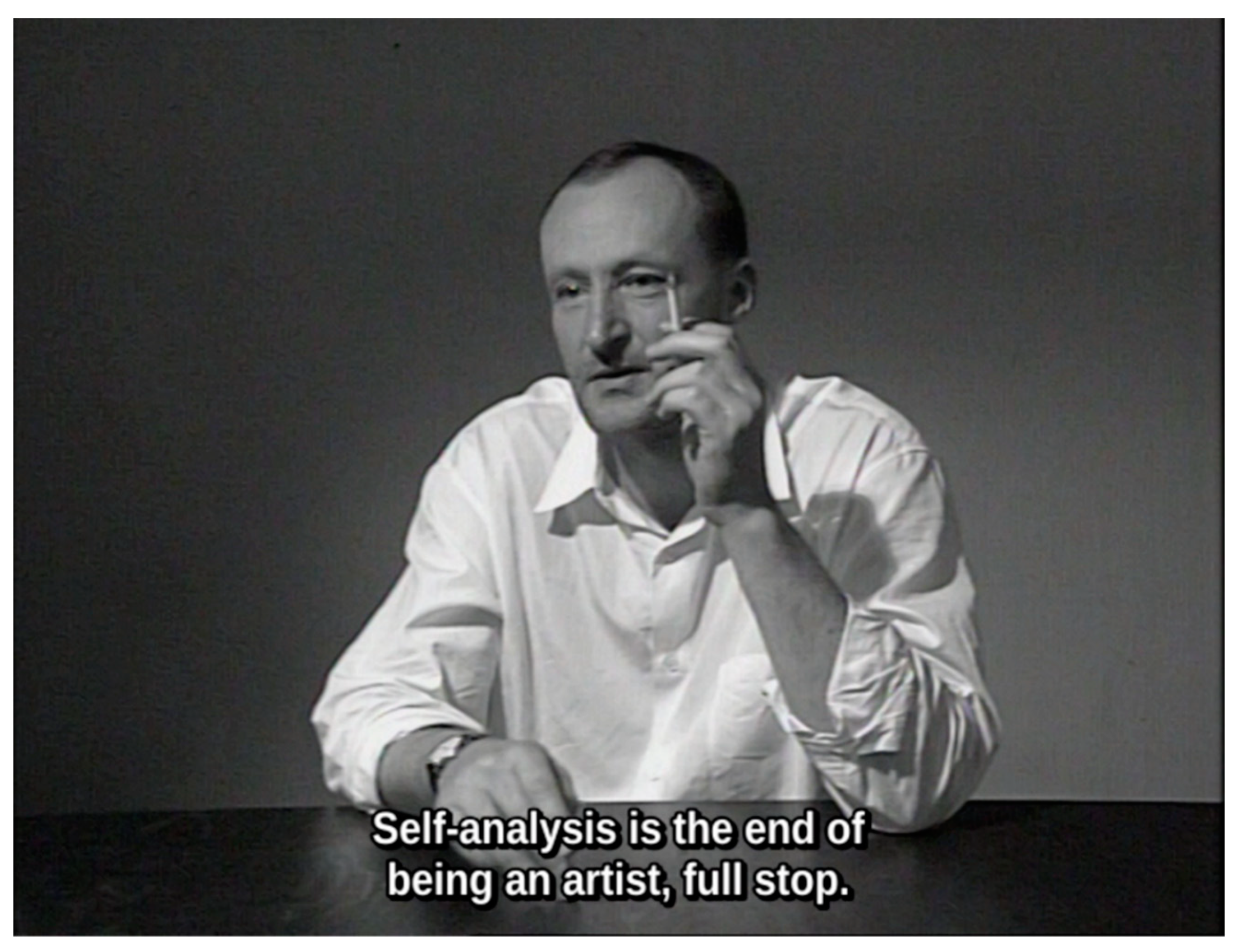

“Vercruysse calls himself the last Flemish Primitive. We are therefore bringing a dead and a living Flemish Primitive into dialogue with each other. If Vercruysse wants to measure up to one of the greatest painters from our part of the world, he will have to prove it now.”1(Vandeckerchove in van Beek 2008) (Figure 1)

2. Constructing the Identity of the Artist

“The artist is an artist only on the condition that he is dual and does not ignore any phenomenon of his dual nature.”

“Even in a self-portrait, of course, we do not see its depicting author, but only the artist’s depiction. Strictly speaking, the author’s image is contradiction in adjecto.”

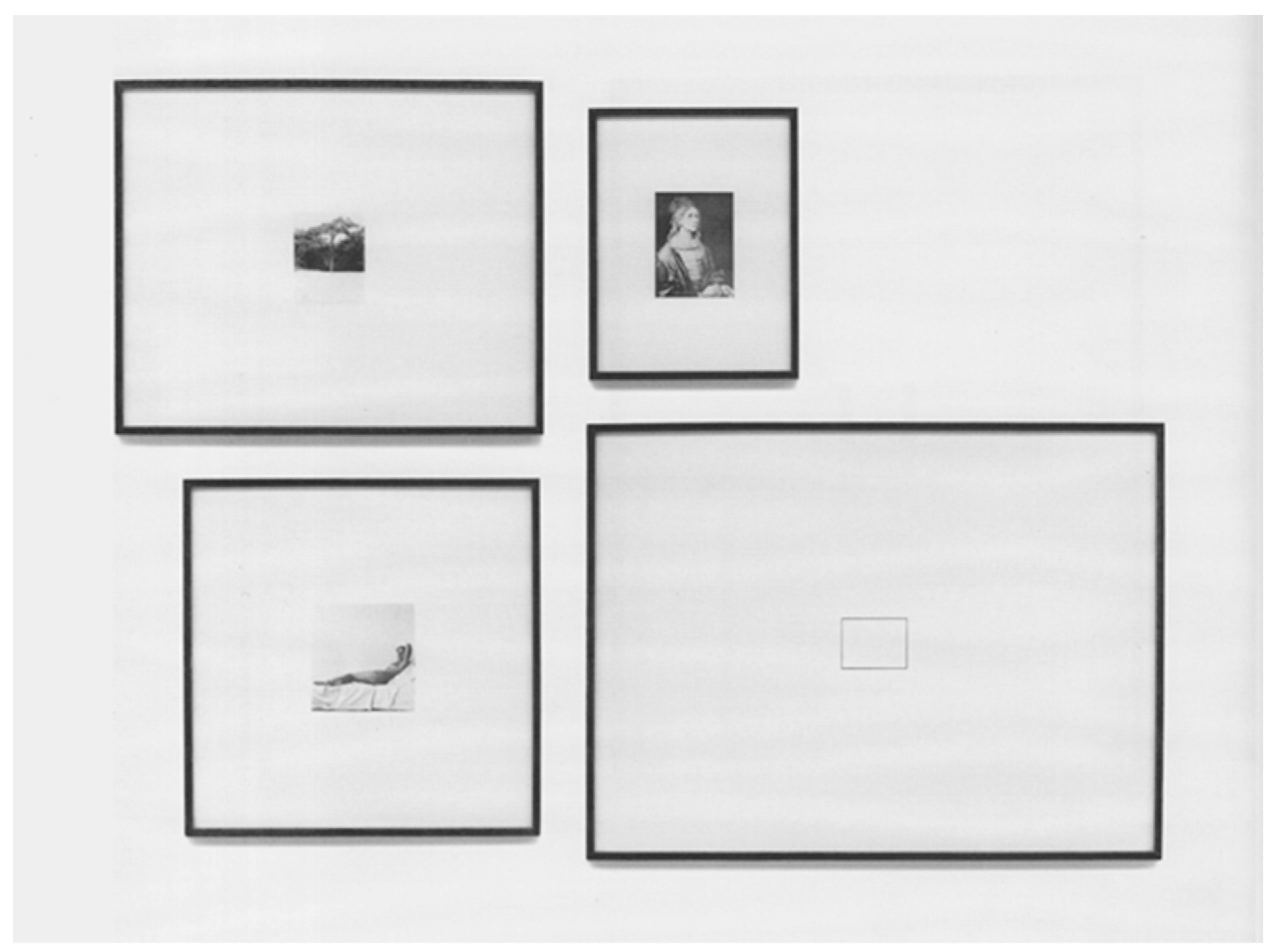

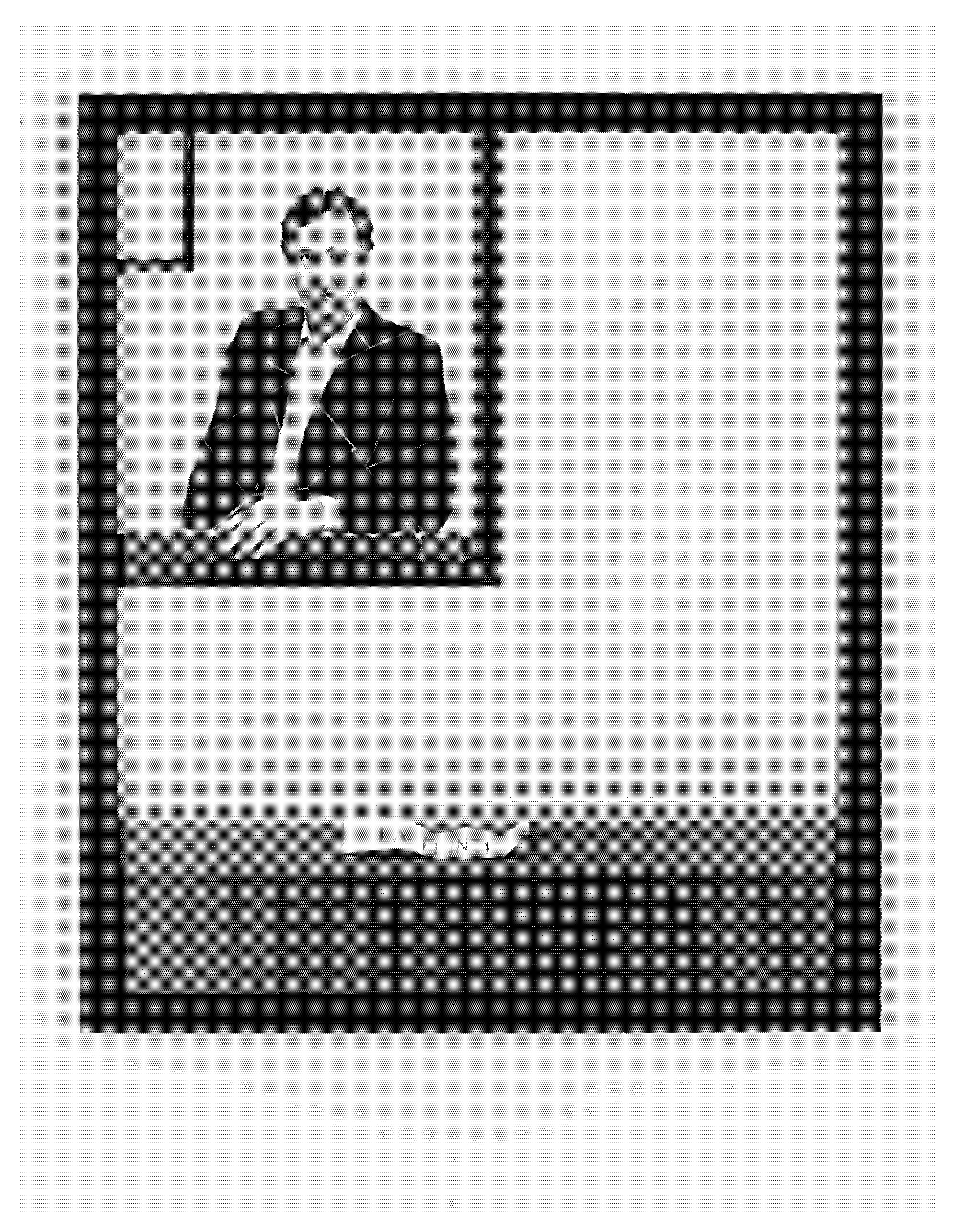

“In a 1983 series of self-portraits, Jan Vercruysse photographed himself in the conventional poses of the Flemish primitive painters. With these works, he not only acknowledges a specific artistic heritage, but some of the conventions associated with the role and métier of the artist.”

“One of the first things we did after Jan had settled in [in Murphy’s apartment in London] was to go to the National Gallery to look at the paintings in the gallery containing the Flemish Masters. On our way out Jan bought the postcard reproduction of Jan van Eyck’s, ‘Portrait of a Man’ and on returning to the house pinned it to the wall above his desk in his room.”

“The Portrait of a Man with a Red Turban has been taken to denote Jan’s status as an artist of the proto-modern kind, rather than an artisan, fully aware of the construct involved in imaging himself and others.”

“The fact that the work uses a photographic image as a material source is then less important as I stress the mise-en-scène—character of artworks and as I think that there is a complete misconception about photography in that all theories profess that all photography always captures “something which has really been there”—trying to make the reality-bound essence of photography: The “Images” I show are as “fictious” as those of a painter—being a “metteur-en-scène”.”

“It [my work] is art because it is at least a reflection on art, because it is formulated in such a way that it can ground itself within the cultural field that calls itself art. […] It is also from this intention that you situate yourself as an artist, that you take up a specific position towards art. It is to the extent that you can make a reflection about the way in which your work criticizes—or commemorates—previous art that you situate yourself.”(Vercruysse in Museum van Hedendaagse Kunst 1979)8

“You expect a portrait to reveal the identity of the person being portrayed. I am not doing that. These works are a game full of false traces, winks and symbols, for the sake of the game, not for the sake of the content. They are composed of elements that are shifted time and again and that could indicate an identity—but do not.”(Vercruysse in Tilroe 1997)10

3. Constructing a Belgian Identity

“As for my anonymous biographer, what do you want me to send you in order to please him? I have no biography. Send him whatever you think will please you. [...] I think that the writer should leave only his works. His life matters little. Get rid of the rags!”

“Jan Vercruysse does not want a portrait photo in this newspaper, no detailed biography, no interview that has been transcribed completely, no explanatory and/or descriptive text for the work he makes (unless he writes the text himself). “Jan Vercruysse, born 1948, lives and works in Belgium” may suffice as a marginal reference to his work.”13

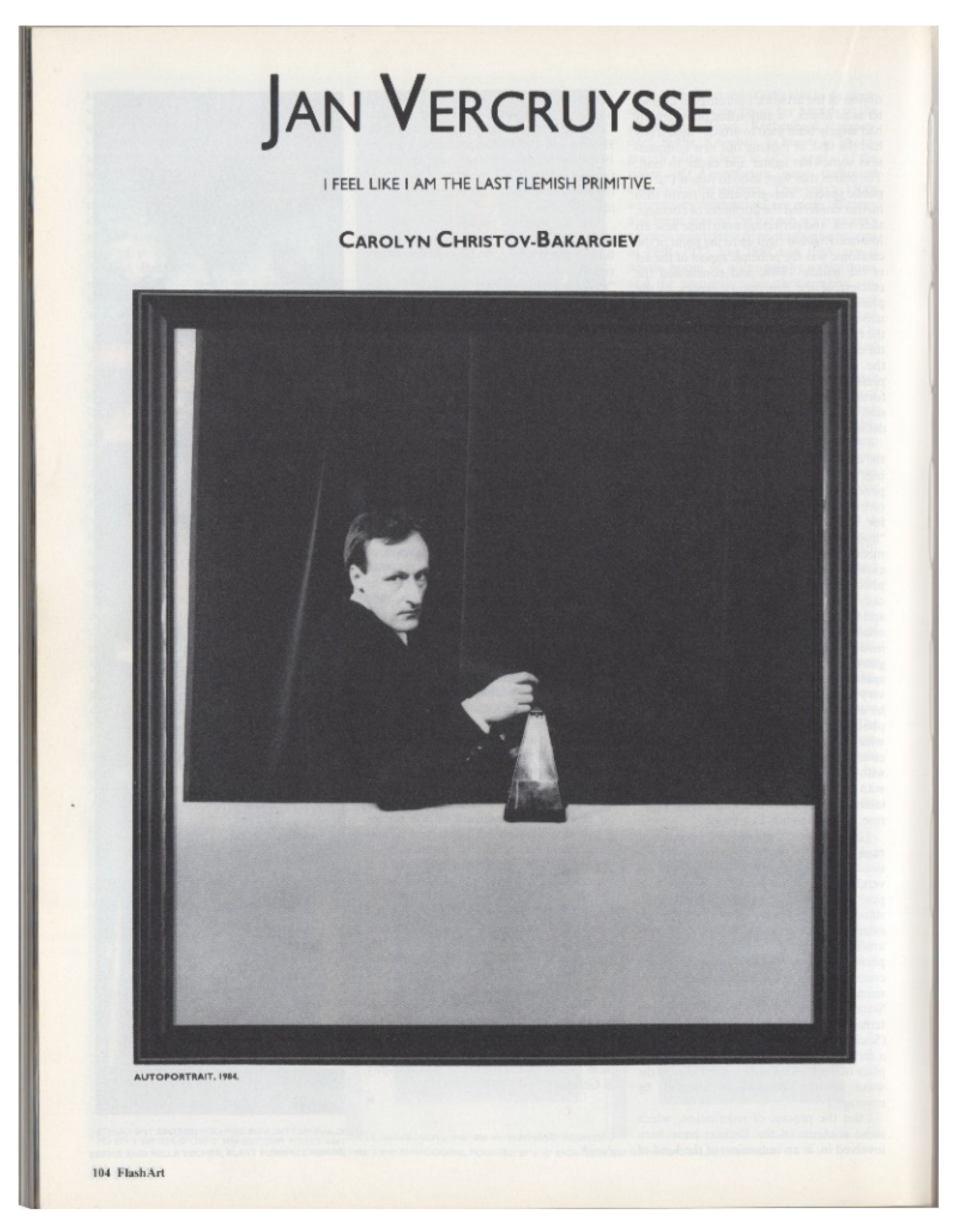

CCB: How did you begin to be involved in art?

JV: What kind of a question is that?

CCB: I know that you studied law at University, that you were a poet, that you did not go to an art academy and that, later, you opened an art gallery in Belgium.

JV: I have forgotten.

(Vercruysse in Christov-Bakargiev 1989, p. 105)

“Vercruysse’s work is the result of deliberate thinking, of a questioning and scanning of art on the whole, the ways of approaching it, its function in society, and its conditions. This results in complex compositions, not always relevant to the spectator. The artist eliminates certain relations and creates in this manner a refined detachment. In this sense he continues the tradition of the Belgian artists Magritte and Broodthaers.”

“Its elaboration of enigma, illusion, and deception is both more extreme and more ancient than those of Vercruysse’s Belgian compatriots and predecessors René Magritte and Broodthaers.”

“Yes, but the misunderstanding is, or would be, that those references to Magritte and twice to Broodthaers, but several times to De Chirico and many times to certain Renaissance paintings, that those would determine the meaning of the content of the work. And that is therefore the risk I took. Which created the misunderstanding that the content of my work would be that reference. Or that historical reference, which is not the case.”

“Broodthaers was certainly the first artist who created a consciousness of the “Belgianness of Belgian Art”—in and through his work. But he did this in a negative way, confirming the international image of the Belgian artist as The Underdog. I always thought that this Belgianness should be turned into a positive force, a positive myth: I have seen too many interesting Belgian artists in the seventies nearly disappear, mainly because they believed themselves that they were the unhappy underdogs.”(Vercruysse in Christov-Bakargiev 1989, p. 105)23

4. (De)Constructing the Belgianness of Flemish Primitives

“What is traditionally called ‘Flemish painting’ is ‘Belgian painting’.”

“But, of course, the political situation of the fifteenth-century did not correspond to the present borders: the realm of the Burgundian dukes had been divided among the Netherlands, Belgium, and France, which allowed patriotic souls in all three countries to claim the glory of early Netherlandish painting for their own. This debate accentuated not only the differences with Italy, but also those among the three northern nations.”

“[…] these masters who so loudly proclaim the Flemish glory were Belgians avant la lettre, Belgians according to the modern formula, faithful to their native aspirations and freely associated with the radiance of the ancient Latin splendor.”

“The Flemish Community is now facing a major challenge. This challenge consists of confirming, promoting and publicizing the identity of our Flemish people. [...] The announcement of our identity implies that the Flemish people become recognizable and recognized beyond our borders, in Belgium, in Europe and in the world.”(Geens quoted in Brams and Pültau 2005)27

“The van Eyck brothers were both born in the small town of Maes-yck-sur-Meuse, “on the borders of German, Flemish and French,—remarks the Count of Laborde—to better show that genius speaks all languages and that art alone is the universal language.””

“The mechanism is one of displacement. If the aim is to define the identity of the artist, his face has become illegible and the identity-definition is displaced […]”

“The only ones who have remained mentally Belgian are the artists. They share the same histories up to and including the most recent ones. They also live in the same art history. You can safely say that I am a Belgian artist. I know Van Eyck. It is mine, in a manner of speaking. Magritte: idem. This separation of image and language in the work of Magritte; a Frenchman would never think that his language does not correspond to the image that he sees. We also live with two cultures, with two languages. Magritte is Belgian; his work can never have been created by a Frenchman. The same for Broodthaers.”(Vercruysse in Decan 2007, p. 73)32

5. Conclusions

“Something everyone always wants to know about every artist is who influenced him, who were his predecessors, his forefathers. And every artist gets a list balanced forcibly on his shoulders. Without argumentation, without justification. To give short shrift to that I said I’m the last Flemish Primitive.”(Vercruysse in Cornelis 2020 [1990])

“What the true artist would certainly do... is circle around, skirt around the truth. Point to it but certainly never formulate it and never divulge it. Because then... if the truth is revealed, then life is at an end. Truth is fatal. And... One of the strengths of art is that art circles it and, as a result, is able to carry on. It is a fire you can burn yourself on, so you have to stay away from it. And you stop everything. If you reveal the truth, you stop everything.”(Vercruysse in Cornelis 2020 [1990])

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

| 1 | Translated by the author from the original: “Vercruysse noemt zichzelf de laatste Vlaamse Primitief. We brengen dus een dode en een levende Vlaamse Primitief met elkaar in dialoog. Als Vercruysse zich wil meten met een van de grootste schilders uit onze contreien, dan moet hij dat nu waarmaken.” |

| 2 | This article is based on extensive research in the personal archives of the artist Jan Vercruysse, held by the Jan Vercruysse Foundation in Brussels. |

| 3 | Translated by the author from the original: “L’artiste n’est artiste qu’à la condition d’être double et de n’ignorer aucun phénomène de sa double nature.” |

| 4 | For a more detailed analysis of the early years of Vercruysse’s career, see (Brams 2012). |

| 5 | Although most scholars agree that this work is a self-portrait by Jan van Eyck, the hypothesis also has its opponents. For a discussion of this debate see (Van Calster 2003), especially pp. 478–83. |

| 6 | The central question of these works is, as Vercruysse has indicated: “How is identity determined? How is the identity of the artist determined?” (Vercruysse in Decan 2007). |

| 7 | “The distinction I made between “light” presence and “strong” presence is based on the distinction between a “sociological” approach and, say, an “ontological” one.” (Vercruysse in Christov-Bakargiev 1989). For a comparison with the Appropriation artists see, for example (Celant 1988). Also significant is the fact that Vercruysse turned down the exhibition Un Art de la Distinction? at the Centre d’art Contemporain de Meymac in 1990, a thematic exhibition departing from the theories of Jean Baudrillard, with among others Sherrie Levine, Jenny Holzer, Jeff Koons, Allan McCollum and Haim Steinbach. Vercruysse turned down the invitation stating that “Je ne fais pas d’examples d’illustrations de strategies ou d’analyses.” [I don’t make illustrations of strategies or analyses.] (Vercruysse 1990). |

| 8 | Translated by the author from the original: “Het is kunst omdat het in ieder geval een reflectie inhoudt over kunst, omdat het op zo’n manier geformuleerd wordt dat het zichzelf kan funderen binnen het culturele veld dat kunst noemt. […] Het is ook vanuit die intentie dat je jezelf als kunstenaar situeert, dat je een specifieke positie inneemt tegenover kunst. Het is in de mate dat je een reflectie kunt maken over op welke manier je werk kritiek inhoudt op—of een herdenken betekent van—voorafgaande kunst, dat je jezelf situeert.” With this description of his work, Vercruysse leans heavily on the Conceptual artist Joseph Kosuth whose work he exhibited in his gallery in 1976 and whose texts he translated into Dutch for the ICC (Internationaal Cultureel Centrum, Antwerp) in the same year. |

| 9 | In a subsidy dossier for a film project in 1983, Jan Vercruysse explains his artistic strategy as follows: “Un des themes de longue durée est l’autoportrait—qui doit être compris comme “portrait de l’artiste” et non comme un portrait “personnel” (d’une personne) […] Ces oeuvres sont faites de, fondées sur le métaphore, l’allégorie, l’association—et la rhétorique […] (Vercruysse 1983). |

| 10 | Translated by the author from the original: “Het zijn geen zelfportretten, zoals ook de foto’s van de vrouwen geen portretten van een persoon zijn. Van een portret verwacht je dat de identiteit van de geportretteerde zichtbaar wordt gemaakt. Daar ben ik niet mee bezig. Deze werken zijn een spel vol valse sporen, knipogen en symbolen, omwille van het spel, niet omwille van de inhoud. Ze zijn samengesteld uit elementen die telkens worden verschoven en die een identiteit zouden kunnen aangeven—maar dat niet doen”. |

| 11 | Translated by the author from the original: “Een waar verhaal, Een niet-waar verhaal, Een echt verhaal, Een niet-echt verhaal, Een fiktief verhaal, Een niet-fiktief verhaal, Een reëel verhaal, Een niet-reëel verhaal.” |

| 12 | Translated by the author from the original: “Quant à mon biographe anonyme, que veux-tu que je t’envoie pour lui être agréable? Je n’ai aucune biographie. Communique-lui, de ton cru, tout ce qui te fera plaisir. […] Je pense que l’Écrivain ne doit laisser de lui que ses œuvres. Sa vie importe peu. Arrière la guenille!” |

| 13 | Translated by the author from the original: “Jan Vercruysse wil geen portretfoto in deze krant, geen uitvoerige, tot in de details opgemaakte levensschets, geen volledig uitgeschreven interview, geen verklarende en/of beschrijvende tekst bij het werk dat hij maakt (tenzij hij de tekst zélf schrijft). “Jan Vercruysse, geb. 1948, woont en werkt in België” mag als randvermelding bij zijn werk volstaan.” |

| 14 | In the work Autoportrait (1982), the artist holds a copy of L’idiot de la famille, Sartre’s biography on Gustave Flaubert. During his lecture “Curating the library” in Antwerp in 2005, Vercruysse presents Sartre’s biography on Charles Baudelaire and Gerrit Borgers’ biography on Paul van Ostaijen as his favourite books. Other biographies included in the library of Jan Vercruysse are, among others: on Arthur Rimbaud (Izambard, Georges. Rimbaud, tel que je l’ai connu. Paris: Le Passeur/Cecofop, 1991; Starkie, Enid. Arthur Rimbaud. Amsterdam: De Arbeiderspers, 1984; Robb, Graham. Arthur Rimbaud. New York: W.W. Norton & co, 2000); Ludwig Wittgenstein (Waugh, Alexander. De Wittgensteins. Geschiedenis van een excentrieke familie. Amsterdam: De Bezige Bij, 2014; Monk, Ray. Ludwig Wittgenstein. The duty of genius. Londen: Vintage, 1991); Marquis de Sade (Pauvert, Jean-Jacques. Markies de Sade in levenden lijve: pornograaf en stilist 1783–1814. Baarn: Uitgeverij de Prom, 1993; Pauvert, Jean-Jacques. Markies de Sade in levenden lijve: een natuurlijke onschuld 1740–1783. Baarn: Uitgeverij de Prom, 199; Sollers, Philippe. Sade Contre l’Être Suprême. Paris: Editions Gallimard, 1996); Casanova (Sollers, Philippe. Casanova l’admirable. Paris: La Librairie Plon, 1998; Roustang, François. Le Bal Masqué de Giacomo Casanova. Paris: Les Editions de Minuit, 1984); Plutarch (Plutarchus. Makers of Rome. Londen: Penguin Classic, 1987; Plutarchus. The rise and fall of Athens: Nine Greek lives. Londen: Penguin, 1990). |

| 15 | It comes as no surprise that Vercruysse admired Pessoa, a poet known for his play with biographical data. In 2005 Vercruysse created the work Places (III.1), in which he incorporates a poem by Alvaro de Campos (heteronym of Pessoa), and as guest lecturer at the Fine Arts Academy in Ghent (KASK) in 2008, he gave a course on Pessoa. |

| 16 | The library of Jan Vercruysse contains a Dutch translation of this essay (Paz 1990). |

| 17 | As René Pingen, in his PhD dissertation on the Van Abbemuseum, described the writings of the French critic Alain Cueff as “abstruse, parallel prose” that instead of clarifying things, edify “clearly an additional barrier” around the work of Jan Vercruysse. (Pingen 2005, p. 477) (My translation). |

| 18 | Translated by the author from the original: “un livre est le produit d’un autre moi que celui que nous manifestons dans nos habitudes, dans la société, dans nos vices.” |

| 19 | The project ran parallel to the much-acclaimed exhibition Chambres d’Amis (from 21 June to 21 September 1986). The aim of the project was to enforce “opportunities abroad for Belgian artists.” To this end, the organization invited three internationally renowned curators Kasper König, Jean-Hubert Martin and Gosse W. Oosterhof, to each make a selection of Belgian contemporary art. Jan Vercruysse was selected by Dutch curator Gosse W. Oosterhof, together with the artists Walter Swennen, Jacques Charlier, Lili Dujourie, Narcisse Tordoir and Luk Van Soom. (Cassiman 1986). |

| 20 | Such as: L’Art en Belgique, Flandre et Wallonie au XXe siècle. Un point de vue (Paris: Musée d’art modern de la ville de Paris, 1990), Kunst in België na 1980 (Brussels: Koninklijke Musea voor Schone Kunsten, 1993), Artists (From Flanders) (Venice: Palazzo Sagredo, 1990), Flemish and Dutch Painting: From Van Gogh, Ensor, Magritte, Mondrian to contemporary artists (Venice: Palazzo Grassi, 1997), among others. |

| 21 | The left image of each depicts a solitary figure (Narcissus), while the right image depicts groups of people (the twelfth and last work of the series is an exception; only one image is reproduced, Jeune Homme Nu Assis au Bord de la Mer by Hippolyte Flandrin (1836) and is accompanied by the caption “ou l’utopie”). For Vercruysse the figure of Narcissus embodies the method or definition of artistic practice. As Liesbeth Decan has pointed out, “art, for Vercruysse, is about a self-conscious artist looking at things and—from that self-awareness—shaping the world.” (Decan 2016, p. 179). |

| 22 | Translated by the author from the original: “Ja, maar het misverstand is of zou zijn dat die verwijzingen naar Magritte en twee keer naar Broodthaers, maar meerdere keren naar De Chirico wat.. en veel keren naar bepaalde Renaissance schilderijen, dat die de betekenis van de inhoud van het werk zou bepalen, en dat is dus het risico dat ik genomen heb en dus… Waardoor het misverstand ontstaan is dat.. de inhoud van mijn werk zou zijn, die verwijzing. Of die historische verwijzing, wat dus niet het geval is”. |

| 23 | Interestingly, in the same issue of Flash Art International in which the interview with Jan Vercruysse appeared, art critic Terry R. Myers (1989) reviewed a show by Belgian artist Leo Copers in New York, thereby affirming the many clichés existing about “Belgian Art”: “The miniscule portion of twentieth-century Belgian art promoted in New York these days is increasingly in danger of being considered initially on the basis its sight-gag potential alone. Visual jokes, historically exemplified in (and for the most part admirably transcended by) the work of Magritte and Broodthaers, for example, have become almost parasitic in the output of many contemporary Belgian artists”, Terry R. Myers, “Leo Copers,” Flash Art International, October 1989, p. 132. |

| 24 | The magazine Vercruysse envisioned was bilingual (Dutch-English). At that time, the only Belgian magazines discussing contemporary art were Kunst & Cultuuragenda (published by the Brussels Palais des Beaux-Arts) and the Brussels based magazine +-0. The magazine Artefactum was founded in 1983. For a discussion on Belgian art criticism in the early 1980s, see (Van Mulders 1984). |

| 25 | Translated by the author from the original: “Ce qu’on appelle par tradition ‘la peinture flamande’, c’est ‘la peinture belge’.” |

| 26 | Translated by the author from the original: “[…] ces maîtres qui proclament si haut la gloire flamande furent des Belges d’avant la lettre, des Belges suivant la formule moderne, fidèles aux aspirations natales et librement associés au rayonnement de l’antique majesté latine.” |

| 27 | Translated by the author from the original: “De Vlaamse Gemeenschap staat nu voor een grote uitdaging. Deze uitdaging bestaat in de bevestiging, de bevordering en de bekendmaking van de identiteit van ons Vlaamse Volk. [...] De bekendmaking van onze identiteit houdt in dat het Vlaamse volk herkenbaar en erkenbaar wordt over onze grenzen, in België, Europa en in de wereld.” |

| 28 | Interestingly, that very same year, Jan Vercruysse was selected to represent Belgium at the Venice Biennial. As a result of the federalization process, since 1972 the task of choosing an artist for the Belgian pavilion is alternated by the Flemish and Walloon communities. Consequently, the exhibition catalogue of Vercruysse’s contribution to the Venice Biennial in 1993 mentions the “Flemish Pavilion” (Padiglione di Fiandra) as opposed to the Belgian pavilion. |

| 29 | Translated by the author from the original: “Les frères van Eyck sont nés tous deux dans la petite ville de Maesyck-sur-Meuse, “sur les confins de l’allemand, du flamand et du français,—remarque le comte de Laborde—pour mieux montrer que le génie parle toutes les langues et que l’art est à lui seul la langue universelle.”” |

| 30 | Belgium has three remaining Federal Cultural Institutions: The Palais des Beaux-Arts (BOZAR), The Belgian National Orchestra, and The Federal Opera House (La Monnaie/De Munt). |

| 31 | On 10 October 1989 Vercruysse was rewarded for his artistic career by the Flemish Community (Vlaamse Gemeenschap), and in 2001 he received the Flemish Culture Price for Visual Arts (Vlaamse Cultuurprijs voor Beeldende Kunst). |

| 32 | Translated by the author from the original: “De enigen die mentaal Belgisch zijn gebleven, zijn de kunstenaars. Zij delen dezelfde geschiedenissen tot en met de meest recente. Zij leven ook in dezelfde kunstgeschiedenis. Van mij mag je gerust zeggen dat ik een Belgisch kunstenaar ben. Van Eyck: ik ken Van Eyck. Dat is van mij, bij wijze van spreken. Magritte: idem. Die ontkoppeling bij Magritte van beeld en taal; een Fransman zou er nooit aan denken dat zijn taal niet overeenstemt met het beeld dat hij ziet. We leven ook met twee culturen, met twee talen. Magritte is een Belg; zijn werk kan nooit door een Fransman gemaakt zijn. Hetzelfde voor Broodthaers.” |

References

- Bakhtin, Michael. 1986. The problem of the Text in Linguistics, Philology, and the Human Sciences: An Experiment in Philosophical Analysis. In Speech Genres and Other Late Essays. Edited by Caryl Emerson and Michael Holquist. Austin: University of Texas Press, pp. 103–31. [Google Scholar]

- Baudelaire, Charles. 1868. De l’essence du rire. Available online: https://fr.wikisource.org/wiki/De_l%E2%80%99essence_du_rire (accessed on 1 November 2021).

- van Beek, Jozefien. 2008. Museum M opent dialoog tussen oude en hedendaagse kunst. De Morgen. Available online: https://www.demorgen.be/nieuws/museum-m-opent-dialoog-tussen-oude-en-hedendaagse-kunst~bc70e320/?referrer=https%3A%2F%2Fwww.google.com.hk%2F (accessed on 22 September 2021).

- Brams, Koen, and Dirk Pültau. 2005. De Mythologisering van de Belgische Kunst. Of hoe de Vlaamse Kunst Belgisch werd. De Witte Raaf. Available online: https://www.dewitteraaf.be/artikel/detail/nl/2914 (accessed on 3 January 2022).

- Brams, Koen. 2012. The Metamorphoses of being an artist. The Shadow Files, 63–73. [Google Scholar]

- Brayer, Marie-Ange. 1990. Côté Musées. Art et Culture, 20–21. [Google Scholar]

- Burke, Seán, ed. 1995. Authorsphip. From Plato to the Postmodern. A Reader. Edingburgh: Edingburgh University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Calster, Paul van. 2003. Of Beardless Painters and Red Chaperons: A fifteenth-Century Whodunit. Zeitschrift für Kunstgeschichte 66: 465–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cassiman, Bart, ed. 1986. Initiatief 86. Gent: Initiatief 85 vzw. [Google Scholar]

- Celant, Germano. 1988. Unexpressionism. Art beyond the contemporary. New York: Rizzoli International Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Chapman, H. Perry. 2013. Self-Portraiture 1400–1700. In A Companion to Renaissance and Baroque Art. Edited by Babette Bohn and James M. Saslow. West Sussex: Wiley-Blackwell, pp. 189–209. [Google Scholar]

- Chevrier, Jean-François, and Jean Sagne. 1984. L’Autoportrait comme mise en scène. Photographies, 47–82. [Google Scholar]

- Christov-Bakargiev, Carolyn. 1989. Jan Vercruysse: I feel like the last Flemish Primitive. Flash Art International, 104–9. [Google Scholar]

- Cornelis, Jef. 2020. Jan Vercruysse 1990. In Jan Vercruysse 1990. Transcript of the film. Edited by Kristien Daem. Brussels: Argos & Jan Vercruysse Foundation. [Google Scholar]

- De Baere, Bart, Norbert De Dauw, and Veerle Van Durme, eds. 1988. Catalogus van de Collectie 1988. Ghent: Museum van Hedendaagse Kunst. [Google Scholar]

- De Dauw, Norbert, and Veerle Van Durme. 1982. Biografische notities en beschrijvingen van werk van 123 kunstenaars. In Museum van Hedendaagse Kunst Gent. Catalogus van de verzameling. Edited by Jan Hoet. Brussels: Societé des expositions du Palais des Beaux-Arts, pp. 539–55. [Google Scholar]

- Deam, Lisa. 1998. Flemish versus Netherlandish: A discourse of Nationalism. Renaissance Quarterly 51: 1–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Decan, Liesbeth. 2007. Jan Vercruysse. Een gesprek met de kunstenaar over zijn ‘Foto-Grafisch’ werk. Cahier Fotografie 1: 70–73. [Google Scholar]

- Decan, Liesbeth. 2016. Conceptual, Surrealist, Pictorial. Photo-Based Art in Belgium (1960s–early 1990s). Leuven: Leuven University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Dompierre, Louise. 1992. Jan Vercruysse: From the Autoportraits to the Tombeaux. In Jan Vercruysse. Toronto: The Power Plant, pp. 9–15. [Google Scholar]

- Edwards, Steve, ed. 1999. Art and its Histories. A Reader. New Haven & London: Yale University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Fierens-Gevaert, Hippolyte. 1928. Histoire de la peinture flamande des origines à la fin du XVe siècle. Brussels: Van Oest. [Google Scholar]

- Flaubert, Gustave. 1859. Lettre à Ernest Feydeau, Croisset, 21 août 1859. Available online: https://flaubert.univ-rouen.fr/jet/public/correspondance/trans.php?corpus=correspondance&id=10363&mot=biographe&action=M (accessed on 1 November 2021).

- Gielen, Pascal. 2008. Kunst in Netwerken. Artistieke Selecties in de Hedendaagse dans en de Beeldende Kunst. Tielt: Lannoo. [Google Scholar]

- Graham, Jenny. 2007. Inventing Van Eyck: The Remaking of an Artist for the Modern Age. New York and Oxford: Berg. [Google Scholar]

- Greenblatt, Stephen. 2005. Renaissance Self-Fashioning. From More to Shakespeare. Chicago and London: The University of Chicago Press. [Google Scholar]

- Gumpert, Lynn. 1986. A Distanced View. ZIEN Magazine, 6–12. [Google Scholar]

- Kremer, Mark. 1993. No Sacrifice, No Good. Over Realisten en Romantici. Kunst & Museumjournaal 5: 27–32. [Google Scholar]

- Krul, Wessel. 2005. Realism, Renaissance and Nationalism. In Early Netherlandish Paintings. Rediscovery, Reception and Research. Edited by Bernhard Ridderbos, Anne van Buren and Henk van Veen. Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press, pp. 252–89. [Google Scholar]

- Lacoue-Labarthe, Philippe. 2014. Portrait de l’artiste, en général. In Écrits sur l’Art. Genève and Paris: Mamco & Les Presses du Réel, pp. 31–75. First published 1976. [Google Scholar]

- Murphy, John. 2018. How I Came to Know Jan Vercruysse… Only This and Nothing More. Available online: https://www.janvercruyssefoundation.com/john-murphy-memoriam (accessed on 1 November 2021).

- Museum van Hedendaagse Kunst, ed. 1979. Aktuele Kunst in België. 19 Portretten. Ghent: Museum van Hedendaagse Kunst. [Google Scholar]

- Myers, Terry R. 1989. Leo Copers. Flash Art International, 132. [Google Scholar]

- Panofsky, Erwin. 1953. Early Netherlandish Painting: Its Origins and Character. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Parent, Béatrice. 1990. Jan Verrcruysse: Le rigueur solitaire. Artstudio, 153–58. [Google Scholar]

- Paz, Octavio. 1990. Het onbekende zelf. Fernando Pessoa. Translated by Willem Brugmans. Leiden: Plantage-Gerards & Scheurs. [Google Scholar]

- Paz, Octavio. 2012. Unkown to himself. In A Centenary Pessoa. Edited by Eugénio Lisboa and L. C. Taylor. Manchester: Carcanet Press, pp. 18–49. [Google Scholar]

- Pingen, René. 2005. Dat museum is een mijnheer. De geschiedenis van het Van Abbemuseum 1936–2003. Eindhoven: Stedelijk Van Abbemuseum. [Google Scholar]

- Pirenne, Henri. 1902. Histoire de Belgique. Brussels: Lamertin. [Google Scholar]

- Poirier, Pierre. 1949. Initiation à la peinture flamande. Paris: La Renaissance du livre. [Google Scholar]

- Proust, Marcel. 2019. Contre Sainte-Beuve. Paris: Folio Essais. [Google Scholar]

- Rimbaud, Arthur. 2015. 15 mai 1871. Charleville, à Paul Demeny. In Rimbaud. Je ne suis pas venu ici pour être heureux. Correspondance. Edited by Jean-Luc Steinmetz. Paris: Flammarion, pp. 64–75. [Google Scholar]

- Sullivan, Bill. 1996. Interview with Jan Vercruysse. Available online: http://www.artnet.com/magazine_pre2000/features/vercruysse/sullivan1-22-97.asp (accessed on 1 November 2021).

- Sulzberger, Suzanne. 1959. La réhabilitation des Primitifs Flamands. 1802–1867. Brussels: Académie Royale de Belgique. [Google Scholar]

- Tazzi, Pier Luigi. 1987. Not Utopia: Jan Vercruysse. Artforum 26: 93–94. [Google Scholar]

- Tilroe, Anna. 1997. Poseren voor een zelfmoord die nooit gebeurt; Gesprek met Jan Vercruysse. NRC. Available online: https://www.nrc.nl/nieuws/1997/12/12/poseren-voor-een-zelfmoord-die-nooit-gebeurt-gesprek-10448925-a255734 (accessed on 3 January 2022).

- Trio, Werner, and Jan Vercruysse. 2006. Personal communication.

- Van Mulders, Wim. 1984. Kunstkritiek: Een bijlhamer? In Biënnale van de kritiek 1984. Edited by Flor Bex. Antwerp: ICC, Internationaal Cultureel Centrum, pp. 8–10. [Google Scholar]

- Van Mulders, Wim. 1990. Jan Vercruysse. Kunst & Cultuuragenda, 60–62. [Google Scholar]

- Vercruysse, Jan. 1983. Melancholie. Film. Extraits du commentaire pour le scénario. Brussels: Jan Vercruysse Foundation, Unpublished material, forthcoming. [Google Scholar]

- Vercruysse, Jan. 1984. Descriptions of Works and of Some Intentions. Brussels: Jan Vercruysse Foundation, Unpublished material, forthcoming. [Google Scholar]

- Vercruysse, Jan. 1990. Letter to Caroline Bissière, 19 April 1990. Brussels: Jan Vercruysse Foundation, Unpublished material, forthcoming. [Google Scholar]

- Verschaffel, Bart. 1998. Pygmalion ou rien. De fotowerken van Jan Vercruysse. De Witte Raaf. Available online: https://www.dewitteraaf.be/artikel/detail/nl/1892 (accessed on 3 January 2022).

- Verschaffel, Jan. 2011. Kunstenaar zijn is ook een kunst. Het ‘eerste werk’ en het oeuvre. In De Zaak van de kunst. Over kennis, kritiek en schoonheid. Gent: A&S Books, pp. 127–38. [Google Scholar]

- Woods-Marsen, Joanna. 1998. Renaissance Self-Portraiture. The Visual Construction of Identity and the Social Status of the Artist. New Haven and London: Yale University Press. [Google Scholar]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Pereira Rodriguez, A. The Last Flemish Primitive: Jan Vercruysse’s Self-Fashioning of Artisthood and National Identity. Arts 2022, 11, 13. https://doi.org/10.3390/arts11010013

Pereira Rodriguez A. The Last Flemish Primitive: Jan Vercruysse’s Self-Fashioning of Artisthood and National Identity. Arts. 2022; 11(1):13. https://doi.org/10.3390/arts11010013

Chicago/Turabian StylePereira Rodriguez, Anton. 2022. "The Last Flemish Primitive: Jan Vercruysse’s Self-Fashioning of Artisthood and National Identity" Arts 11, no. 1: 13. https://doi.org/10.3390/arts11010013

APA StylePereira Rodriguez, A. (2022). The Last Flemish Primitive: Jan Vercruysse’s Self-Fashioning of Artisthood and National Identity. Arts, 11(1), 13. https://doi.org/10.3390/arts11010013