Abstract

Absurdity in art creates bizarre juxtapositions that expose, and question conflicted, even dangerous, aspects of life which have become normalized. Absurd art appears in troubled times, subverting moments of extreme contradiction in which it appears impossible to think differently. For example, Dada (1917–1923) used nonsense to reflect the nonsensical brutality of WW1. The power to unsettle in this form of art rests in disrupting the world of the viewer and positioning them as interlocutors in a new framing. Absurdity in art reveals the absurdity that is inherent in life and its institutions, breaking the illusion of control. It can help us to comprehend the ‘incomprehensible’ in other species and spheres of life. In the challenge of anthropogenic climate change, how might the absurd capture the strangeness of current times in which a gap is widening between the earth we live ‘in’ and the earth we live ‘from’? This article explores qualities of the absurd in art as a possible way in which to grasp and reimagine ourselves beyond the anthropocentric, focusing on the work of the artists John Newling (b. 1952, UK) and Helen Mayer (1927–2018, US) and Newton Harrison (b. 1932, US), known as ‘The Harrisons’.

1. Introduction

The Anthropocene is a moment in geological time when human activity negatively influences the planet’s climate and ecosystems. It is dangerous, not well understood and unpredictable. It demands a critical reimagining of human existence on the Earth, operating on the edge of what is conceivable to the human mind. As the pace of the environmental crisis escalates, it has become increasingly important to question habits of thought and open up the incomprehensible and unimaginable sphere of other species and forms of life (Latour 2020; Haraway 2016; Tsing 2015; Stengers 2017).

I propose the absurd in art as one possible approach to this reimagining. The absurd acknowledges the extreme contradictions of situations in everyday life, interrogating these through wit and subversion. In creating strange, if not bizarre juxtapositions, the absurd parodies existing reality, rather than constructing alternative realities. Importantly, absurd art positions the viewer/spectator as an interlocutor in a process of thinking and questioning the world (Adès 1974). An influential historical example is the play Ubu Roi 1896, by the Paris-based playwright Alfred Jarry (1873–1907). The play parodies Macbeth, using nonsense to mock and bewilder its audiences and flouting the conventions of theatre of the time. Jarry’s point was to reveal the power and greed of the bourgeoisie in late 19th century Paris (Jarry 1951). His work is considered a precursor to other movements in absurd art, including Dada, Surrealism and the Theatre of the Absurd1 that then influenced Fluxus (1960–present) (Friedman 1998) (Kaprow 2003)2.

The article explores the following three questions: How does the absurd in art disrupt anthropocentric thinking? How does the absurd support the imagining of an alternative quality of relations between human beings and living systems, displacing the expectation of control with an openness to the implausible and serendipitous? As a form of art, how might the absurd work alongside other forms of representations such as Zalasiewicz’ thought experiment (outlined below) in the domain of science?

There are three underpinning premises to the article. Firstly, the absurd is different from irony. Where both concepts address the paradoxical, irony, even in its extreme form of sarcasm, is weaker. The absurd emerges at a point of rupture, where life appears to have become nonsensical, not just paradoxical. In exploring irony in postmodernism, Stuart Jeffries points to the work of the American conceptual artist Jenny Holzer (b. 1950). Her work is critical of rampant consumerism. This manifests through a series of ironic public statements such as, “Enjoy yourself because you cannot change anything anyway” (Jeffries 2021, p. 4). Holzer allows her critical statements to appear on objects of consumption, such as baseball caps, T shirts, skateboards and she has even worked for the luxury brand, BMW. Jeffries shows us, through this example, that irony can become appropriated. In contrast, the absurd upholds a tension between the nonsense of the world and the nonsense of the artwork. In this way the artwork and human world mirror each other and are exposed as equally ridiculous. A new situation is created through the tension that draws us in as interlocutors, provoking us to think deeply. The particular form and dynamic that absurd art offers in the face of an intolerable reality is therefore significant as one of many possible responses to the current crisis.

Secondly, despite the growth and importance of social and political activism in the environmental crisis, this article and its underpinning examples are not concerned with activism per se, but with the conditions that expose us to the nonsensical in what we have come to accept as ordinary and everyday. The absurd provokes critical thought and reflection rather than action or activism, though action may follow from its insights.

Thirdly, absurd art does not set out to ‘do good’ in the world. While absurd artists make work that addresses problematic aspects of social/political existence, they expose us to life ‘as found’, revealing inconsistencies and contradictions, at times uncomfortably so.

The article opens with the context, a detailed account of a vivid image of the Anthropocene. This image is a thought experiment of the paleontologist, Jan Zalasiewicz (2020), who uses scientific data to bring into appearance a world that we have struggled to imagine, but one, he argues, in which we need to take immediate action. Human beings are caught in a paradox, in which we are dependent upon the earth but are increasingly destroying its living systems. Bruno Latour, a philosopher of science, challenges the arts to join the sciences and to offer new representations that help us to metabolize the terror of environmental devastation. He draws attention to powerful metaphors that position us outside of the conditions on which all biological life depends. ‘The Blue Planet’ or ‘The Blue Marble’ have alienated human beings from the thin skin of atmosphere and soil on which all organic life depends. This skin is known to the geological sciences as the ‘critical zone’ (Latour 2020, p. 13)3.

Not all approaches to the making of art in the current crisis are absurd, nor should they be. The article references several approaches that range from the critical as spectacle to storytelling, instruction, deep observation, and practices of care. These, in the main, open contemporary art to issues that are beyond art, issues of colonization, globalization and exploitation. They do not necessarily address the strange, incomprehensible worlds that lie beyond human control but nonetheless constitute life on earth, disrupting human rationality (Gasparin et al. 2020).

Absurdity is increasingly referenced as a way to think about the current crisis (Okri 2021; Gasparin et al. 2020; e-Flux Journal 2019). It is evident, albeit subtly so, in the work of a few artists who are currently addressing environmental issues. These include Katie Paterson’s Future Library 2014–2114, in which the forests that will support a new anthology of books in 100 years have recently been planted4; Mary Mattingly’s Owns Up 2013, a commitment to living with bare essentials by turning personal belongings into sculptural objects5; Simon Starling’s Autoxylopyrocycloboros 2006, a four-hour entropic voyage made across Loch Long on a small wooden steamboat, fueled by wood cut piece-by-piece from its own hull6. These are environmental and absurd works by artists a generation or two younger than the artists I will focus on: John Newling (b. 1952, UK)7 and Helen Mayer (1927–2018, US) and Newton Harrison (b. 1932, US), known as ‘The Harrisons’8. Newling and the Harrisons are selected because they are internationally renowned as artists in the field of environmental art. As an artist researcher I have closely followed their work over several years through research, critical writing and project co-ordination. This aspect of the absurd in their work and its possible relevance to the present has increasingly intrigued me9. The work of Zalasiewicz is a particularly vivid counterpoint coming from the sciences, and functions differently, a point that I will address in the conclusions.

2. Context

“…this human-driven Earth is being pushed hard and variously”(Zalasiewicz 2020, p. 43)

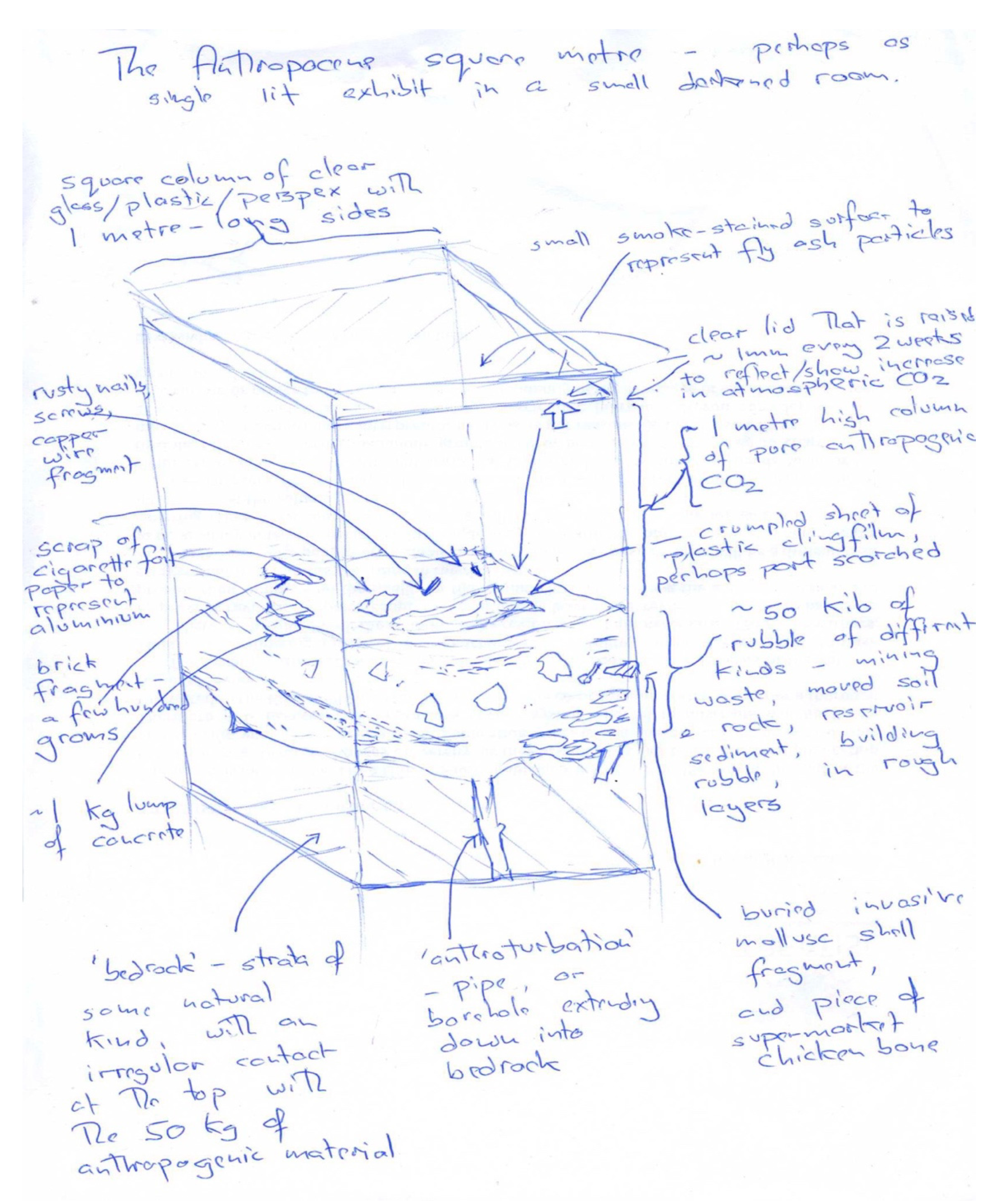

Imagine the thin skin of the Earth as a square meter cube. Imagine adding a series of ingredients to the cube that represent commonly found materials that now make up Earth, man-made materials such as concrete, brick, plastic, alongside soil and natural minerals. Calculate each ingredient in approximate proportion to their presence on Earth, understanding that different materials will present themselves distinctively—plastic is now found almost everywhere and concrete might be concentrated in some places more than others. Minerals and chemicals follow a similar complex, erratic pattern.

This is a thought experiment developed by Jan Zalasiewicz, a field geologist and paleontologist (Figure 1). It forms a vivid representation of the way in which human culture is altering the constitution of the Earth, its physical make-up, and its dynamic processes, creating the era known as the Anthropocene. Zalasiewicz’ method is to draw on data in a series of calculations related to each material: concrete, plastics, brick and iron, offering a way to see the pace of change in the environment from the perspective of the deep time frame of paleontology. He notes moments in which change has suddenly escalated. One such spike coincides with the Industrial Revolution in the mid to late 19th century, with the rise of coal mining to support new industries and another in the mid-20th century around 1948 in support of post-war recovery and new forms of industrial growth (Zalasiewicz 2020, pp. 36–43).

Figure 1.

Zalasiewicz, The Anthropocene Square Meter, 2019. Sketch. (Zalasiewicz 2020, p. 37) (courtesy of the scientist).

Time concentrates the effects of human behaviors. The amount of concrete produced since World War Two (WW II) to the present is a difference of a third of a billion in the 1950s to 30 billion tons a year currently, creating an overall total of approximately 500 billion. This may be represented in the square meter cube by a kilo sized lump or, alternatively, a 2mm layer covering its surface. The story of plastic, a relatively new material in the paleontologist’s timescale, is even more challenging. In the 1950s, approximately 2 million tons of plastic was produced per year. In the 1970s, this increased to 50 million tons per year and now stands at 300 million tons per year, with a total presence of 8 billion tons (Zalasiewicz 2020, p. 39). Plastic does not disappear and frequently presents itself in the form of pyro-plastic pebbles. They look like pebbles, but they float, another possible addition to the meter cube.

A second area of the same proportions above the first cube might represent the scale of atmospheric carbon dioxide on the Earth’s surface. This rivals the mass of concrete in the soil. We now know that atmospheric carbon dioxide is growing, if thought of as a pure layer of gas, at one millimeter a fortnight, with the result that oceans are becoming more acidic, and heat is increasingly trapped, making the Earth warmer and expanding the seas at a rate 3 mm per year.

What does Zalasiewicz’s representation offer us?

…the square metre is, in the end, just a device to show that this human-driven Earth is being pushed hard and variously…As it is increasing from decade to decade, and indeed from year to year, we have yet to see its full effects… we have no idea where these are… the technosphere is taking on a life of its own acting as an emergent system with its own dynamics.(Zalasiewicz 2020, p. 43)

This experiment is arguably more than a device. It produces a vivid and daunting image of uncertainty, an experience that poses an unspoken, uncomfortable question: What now?

3. Alienation and the Myth of Progress

Latour describes our times in terms of an existential crisis as significant as that described by Galileo in the 17th century when, through the invention of the telescope, he represented to our senses Copernicus’ observation, made some hundred years before, that the Earth revolved around the Sun. This invention led the West to question its belief in the centrality of human beings in the world and affected all aspects of society. As a device, it was key to changing perception. We have adjusted to this existential crisis, only to move to a new one, using this change to imagine ourselves outside of the Earth, building cultures based on reason and a mastery over the earth’s resources that have alienated us from the systems on which our lives depend (Latour 2020; Arendt 1978).

Latour characterizes this predicament as a gap between two modalities of living. We live ‘from’ a world that is out of reach and ‘in’ a world in which we are never quite at home. The world we live ‘from’ is increasingly generated elsewhere through practices of colonization, industrialization, hypermobility, and technology. The world we live ’in’ is supported by forms of governance in Nation States that create a false sense of security and a paralyzing thoughtlessness about the future. We have become beneficiaries of things that are made possible elsewhere, beyond what we feel able or equipped to be responsible for (Charbonnier 2020; Latour 2020). In the process, we have also come to tolerate the decadence of a situation in which personal progress and ambition comes at the cost of the suffering of others. Such contradictions and, more importantly, the way in which they have become accepted as normal, increasingly appear to be nonsensical.

Moments of upheaval, such as the current crisis of the environment, attacks the fabric of society in a shaking up of the cosmic order. It is perhaps in the widening gaps and abrasive contradictions between nature and human life that the sense of something being absurd arises, a loss of meaning, the feeling of life becoming ‘at odds,’ even ridiculous. Latour calls upon the arts to support a radical and now urgent rethinking.

Latour challenges the arts to turn the entropy of fear and anxiety into new energy. What might this mean to artists?We don’t have the right imagination nor the psychological makeup to metabolize the flood of terrifying news pouring in every day. How to cultivate emotional resources without the arts? Changes in cosmology cannot be registered without changes in representation10—in all tenors of the word.(Latour 2020, pp. 7–8)

4. What Now?: The Place of Absurd Art

Latour and Zalasiewcz reveal how powerfully the human imagination tells stories that we act upon, building worlds and ways of living. Zalasiewcz is a co-author of the article The Business School in the Anthropocene: Parasite logic and pataphysical reasoning for a working earth (Gasparin et al. 2020) that explores Jarry’s concept of pataphysics to challenge human-centered ways of thinking about the Anthropocene in the sciences. They define pataphysics as, “a science that subjects dominant modes of rationality to a divergent thinking of the absurd and proposing playful forms of reasoning” (Gasparin et al. 2020, p. 385). Ben Okri (b. 1959), the Nigerian poet and writer, commenting on COP 26, Glasgow, Scotland, compares the emergence of Camus and absurdism during WWII with the current crisis in both needing a new philosophy to answer the extreme truths of the times (2021). A relatively recent editorial of e-flux, the international journal for the arts organization e-flux, explores the creative power of language and image to generate attitudes and behaviors in public life. Writing in October 2019 at the height of Donald Trump’s manipulation of public media, they connect the political moment in the early 21st century with Dada, a form of absurd art that emerged in 1917 at the height of World War One (WWI).

Even by 1919, Dada was in full swing. Now, just as then, the perversion of autocratic power triggers a kind of absurdist, perverse artistic response.(e-Flux journal 2019)

This comment suggests a relationship between extreme politics and radical, avant-garde forms of art. Dada, as one of many iterations of absurd art, called into question every aspect of society and the traditional values on which these were based, including art. The artists, such as Marcel Duchamp (1887–1968), Jean Arp (1886–1966), Francis Picabia (1879–1953) and its founder Tristan Tzara (1896–1963), initially parodied everything through an aggressive form of nihilism and then satire and buffoonery. The point of Dada’s irreverence was to reveal the absurdity of the horror of existence at that time, by means of the absurd. The artists reacted to the senselessness of WWI, a war which was described by political leaders at the time as a noble cause (Adès 1974; Arp 1974; Brotchie and Gooding 1991; Douglas 2021).

In facing the very real possibility of a sixth extinction, what relevance could the absurd hold in the present?…there is no other moment in history of this troubled [20th] century which has linked ideas of revolutionary political change so closely to the operations of magical transformation in art and poetry and sought to subvert familiar social relations and received ideas in every sphere by subjecting them to rigorously witty and fantastic interrogations.(Brotchie and Gooding 1991, p. 12)

5. Criticism as Spectacle Versus Absurdity in Art

In the same e-flux issue, Iliana Fokianaki, the Greek curator, researcher, and writer, explores two artworks exhibited at the 2019 Venice Biennale, one of the most important global platforms for contemporary art in current times. The Chinese artist Ai Wei Wei recreated a photograph depicting the death of Aylan Kurdi, a three-year-old child refugee washed up on a Turkish shore in September 2015. Christoph Büchel, a Swiss artist, moored a boat, which had caused the death of many migrants when it capsized, next to a café at the same event (Barca Nostra). Whilst both these works might appear to present aspects of the absurd, such as using techniques of surprise or shock to disrupt complacency in relation to the plight of migrants, they are not actually absurd artworks. What might be the difference and why is it important?

Both works transgress codes of respect towards the dead, Fokianaki argues. Both artists hold sufficient cultural capital within the institution of art to be able to amplify the effect of a real-life tragedy. Their access to public attention places them in danger, unintentionally, of exploiting tragedy to enhance their own self-image, a transgression of ethical responsibility towards other human beings (Fokianaki 2019). Unlike absurd art, I would add, their sphere of critique does not extend in both directions, to the world outside of art and to those of the art institution, as occurs in Dada and Jarry’s Ubu Roi. Büchel, and Ai Wei Wei certainly exposes the politics and misery of migration, but as a spectacle. We, the audience, are positioned as witnesses to the pain and distress of others without responsibility, effectively as voyeurs or consumers of the work11. To reveal the absurd in life, the absurd in art also satirizes itself, in some sense balancing power and creating a space in which to participate in meaning making. I will return to this point.

6. Questioning Art While Questioning Culture: Characteristics and Examples of Absurd Art

Absurdity in art reflects one absurd situation or encounter in terms of another. When Man Ray studded a flat iron with tacks and presented this as an artwork [Cadeau (Gift) 1921], Duchamp responded with an even more subversive gesture by proposing that the ironing board should be made of a Rembrandt (Girst 2014, p. 185). This exchange may appear to some as violent, even nihilistic, reducing the work of art to the value of ordinary objects and vice versa. An alternative reading might focus on the humor at the heart of the exchange. The ‘combat’ between the two positions questions what art could be. We become suspended in the uncertainty, without being reconciled one way or the other, drawn to think through the issues from a fresh perspective.

The work of the contemporary artist John Newling shares some of the qualities of the absurd in Dada. It is situated in ordinary everyday experiences in ways that unnerve what we assume to be normal, creating sparks of insight. Newling describes himself as making art with a social purpose and has increasingly addressed ecological issues. He sees the social and ecological as inextricably linked and uses one to interrogate the other.

7. The Preston Market Mystery Project 2006 John Newling

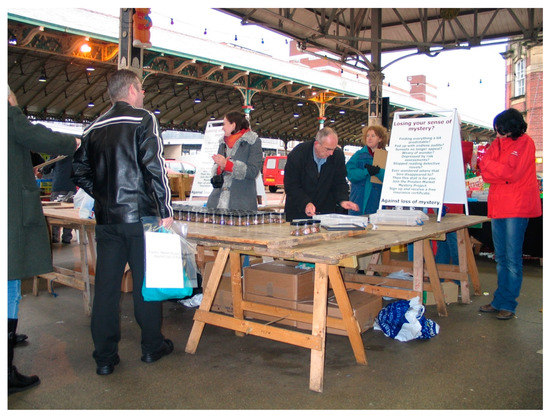

In 2006, Newling took a market stall that he ‘mis-appropriated’ in several ways. Alongside stalls engaged in transactions of fruit and vegetables, he inverted the relationship between buyer and seller, inviting members of the public to offer their experiences of mysteries, however they defined these, in exchange for certificates that insured against the loss of mystery and a jar of 2p coins (Newling 2008) (Figure 2). He was curious as to whether others shared his concern that a sense of mystery and wonder was becoming lost in a world focused on trying to secure certainty. Visitors to the market responded to this seemingly bizarre activity by recounting mysteries of all kinds, from the inexplicable loss of a key or to an unexpected recovery from serious illness. They were willing to participate in an apparently nonsensical, absurd form of exchange.

Figure 2.

The Preston Market Mystery Project: The Insurance Stall, November 2006 (Newling 2008) (Courtesy of the artist).

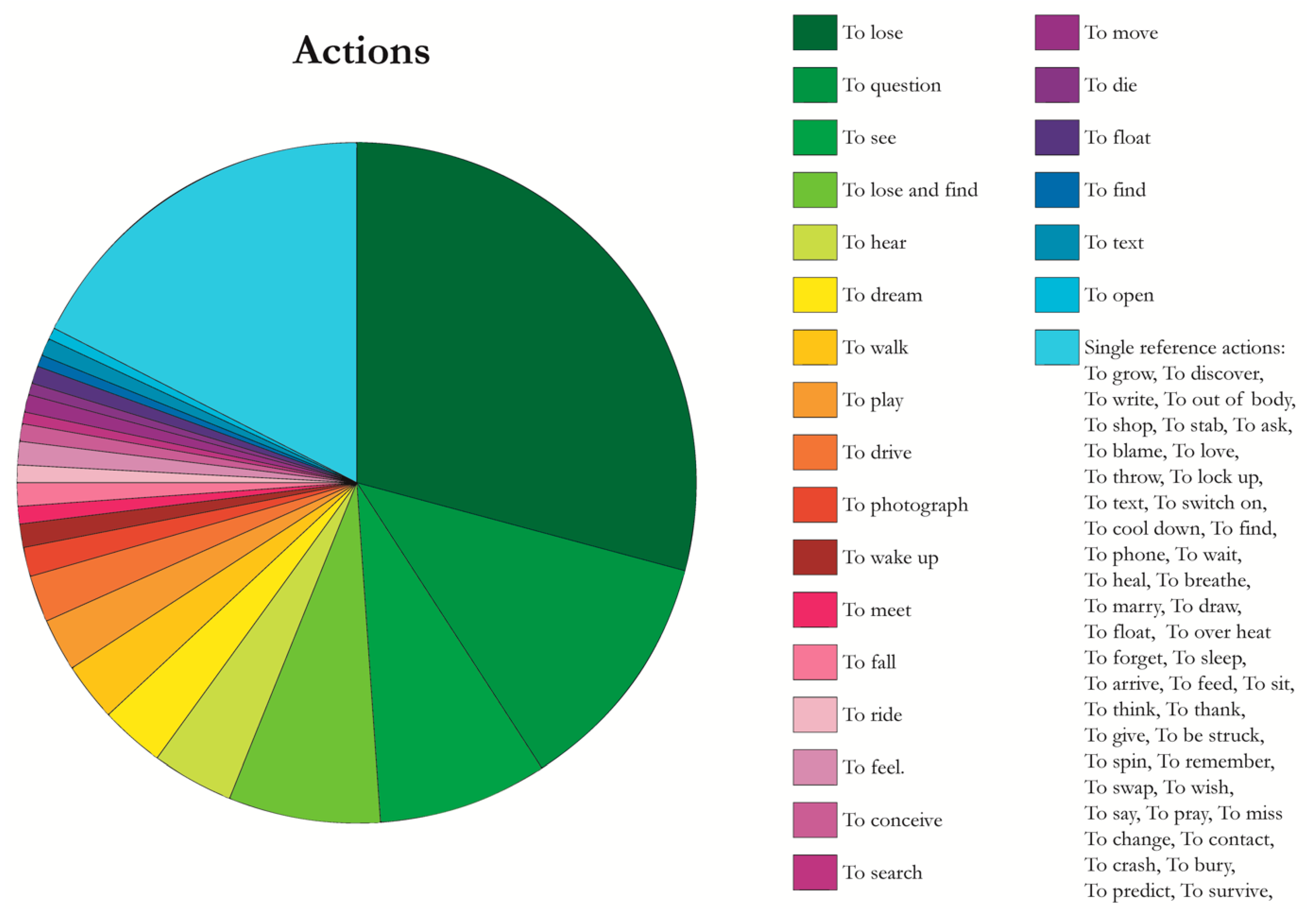

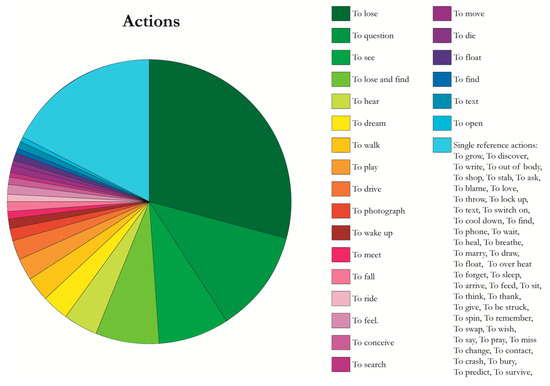

Following this, Newling converted the marketplace into a place of worship and public proclamation. He read the collected mysteries as if they were liturgical texts, from a spot-lit golden lectern assembled at the five key entrances into the market. It is important to point out that the readings were an act of care, not mockery. The performance lasted well into the night. Later in the process, the market also became a banqueting hall for a few individuals whose contributions had stood out, some 40 contributors who, through correspondence beforehand, had explored the peculiarities of their mysteries. Other members of the public were encouraged to view this ritual meal from a distance. The fourth aspect of the work involved an unlikely but careful analysis of the mysteries in terms of actions, deploying the methods of social science analysis, such as anonymizing the contributors and presenting ‘data’ in various configurations, lists as well as pie charts (Figure 3). The results were published as free newspapers and presented back to the public for their engagement and interpretation.

Figure 3.

The Preston Market Mystery Project: The Propositional Stalls (analysis of mysteries) (Newling 2008) (Courtesy of the artist).

Mysteries break the threads of certainty that we have come to expect as a mode of being. Losing something is the dominant single activity reflected in the pie charts, but an almost equal proportion of the chart represents a wide range of other actions, forty-five in total that were only mentioned once, including ‘to grow’, ‘to discover’, to ‘out of body’ and ‘to shop’. In Newling’s playful handling, the market’s primary function as a place of monetary exchange is flipped and takes on questions of human belief and value. It is not only the cultural institution of the market that is critically targeted in the work, but also institutions of religion, ritual conventions as well as scientific method. The pie chart, normally a reductive simplification of human experience, reveals instead an astonishing complexity of beliefs and understandings of mystery.

Participation was carefully framed and guided at all four stages. The work is a form of call and response, of leading (the provocation of the market stall) and following through (offering personal stories of mysteries)12. This rhythm was sustained throughout the work. Without the willingness of people to participate, there would be no work of art. In this way, instituted practices that manage risk to make us feel comfortable in the social sphere, such as the insurance industry, the church and the market, are exposed and questioned through a dialogue between artists and participants willing to give time to the process.

In later works, Newling extends his questioning of the normal and socially accepted, into materials. With characteristic irreverence, he composted copies of TS Eliot’s The Wasteland13 (Eliot’s Soil and Eliot’s Notebooks 2018, Turner Contemporary), transforming a canonical work of literature into the commonplace medium of soil that he then used as a medium of growth for new life. In a suite of works about value, he grew, harvested, stripped, polished, and assembled cabbage walking sticks (Coin, Note and Eclipse 2011–2012; A Garden of Walking Sticks 2011–2013; Blanket 2012). He tended a lemon tree for 688 days as a work of art. On its demise, he celebrated the first dead tree to be ‘collected’ as an artwork, relishing the nonsense it made of the art market (The Lemon Tree and Me 2009–2010 in Newling 2015) (Figure 4). His materials are increasingly ‘natural’, in line with an emergent trope in ecology art, but they are not simply instrumental to making a work. Newling painstakingly positions the natural and man-made in opposition to each other and in conflict. He parodies human behaviors in relation to the natural world through implicit questions such as: Can a dead tree be collectable as an artwork? Can an artwork support growth and organic life? The absurdity of tending to a lemon tree for 688 days gives us hope and helps us to reimagine our relationship with nature. This leads to a more fundamental question: What is at stake in this relationship between humans and other living systems?

Figure 4.

John Newling (b. 1952) The Lemon Tree and Me (2010). (Courtesy of the artist).

8. Metabolizing Fear in the Environmental Crisis

Newling’s approach is part of an exponentially developing interest in art and ecology. Exhibition making has also grown, e.g.,: Radical Nature, Barbican London, 2009; A Museum as an Ecosystem, Taipei Biennale, 201914; Critical Zones, ZKM, Karlsruhe, Germany, 202015 that opens this article; and the current Back to Earth initiative, Serpentine Galleries, London, 2020, are a handful of relatively recent examples. I will focus on the curatorial approaches of the last two.

Critical Zones draws together scientists and artists collaborating on current research projects, alongside historians and philosophers of art and science, a co-operative effort that is astonishingly rich and unprecedented. Back to Earth, at the Serpentine Gallery in London, has invited artists to respond to the climate emergency by proposing artworks that could take form as a campaign, a methodology or an intervention. The project is ongoing and multi-sited. Both initiatives predate the COVID 19 lockdowns in their planning stages. Both address the complex and messy realities of contemporary life and offer a rich diversity of ways to meet the challenge of addressing the fear that the environmental crisis has provoked (Latour 2020, p. 13). The Serpentine initiative is artist-focused through questions of extinction: What are we losing? How do we understand global change on a massive scale? How can an individual understand themselves in relation to collective responsibility? The initiative is inspired by the activist artist Gustav Metzger (1926–2017), who saw this time as a wakeup call. Artists needed to use their skills and experience to raise awareness and support the taking of responsibility16.

The range of artistic approaches, as reflected in the Serpentine’s 2021 publication Remember Nature, is striking. The book contains 140 different artists’ ideas17. These include personal experiences such as Manthia Diawara’s moving account of the collision between indigenous and Western lifestyles on a beach in Senegal (entry 85) or Carolina Caycedo’s encounter in Berlin with Pedro Juan, a spiritual leader of an indigenous people in the Sierra Nevada, Colombia, exploring the implications of a major multi-purpose dam on native land (entry 23). Other contributions involve ‘practical’ instructions for rethinking the present, such as Black Quantum Futurism’s Collective that invites us to explore home through different spatial–temporal relationships by means of a traditional water clock (entry 19); or Katherine Hamnett’s bold cross and bones drawing that carries the instruction CLEAN UP OR DIE (entry 72). Agnes Denes, in her 1969 manifesto, advocates “questioning, reasoning, analyzing, dissecting and re-examining” (entry 3) while Jasleen Kaur (entry 60) offers “a recipe for grounding elders”, a practice of care in seven lines involving a grandfather, a wool shawl, bare feet in contact with grass or mud and Glaswegian sunshine. Alison Knowles, a Fluxus artist, offers two lines: “Diversify/turn bean into being” and then lists 29 varieties of bean to develop her point (entry 8) (Obrist and Stasinopoulos 2021).

This collection of artists’ ideas addresses fear with hope and, from time-to-time, with humor. The artists use instructions to encourage experimentation, following the curators’ invitation. The contribution of Latai Taumoepeau, the Australian contemporary artist, who addresses race and colonialism, helped me to identify an important quality of absurdist tactics resonant of the work of Newling. Her work takes form as simple instructions in eight lines for planting bananas (entry 76). In the subtext, she comments that she does not mind that her instruction is read as abstract or even absurd. The Back to Earth invitation had immediately taken her on a journey to the Philippine Island Nations that have been at the front line of the Climate Change crisis for 30 years. It evoked ‘bananas’. If people wanted to ignore, discuss or even ridicule her instruction, she comments, with some irony, then their response is no different from experiences of colonization as exploitation and abandonment. Through this work I understood the importance of mutuality in the way the absurd creates agency. Experiences of the ridiculous or nonsensical are unpredictable and instantly recognizable, in the same way as getting a joke, but in this we act co-operatively, from a shared ground. Taumoepeau points to a situation of discrepant power in which only one side of the juxtaposition is considered absurd and at the cost of the another. Her work, while not thought of as absurd art in the sense of sharing insight from a place of equality, nonetheless makes a powerful point with minimal means.

Let me try to exemplify the quality of mutuality in another of the Harrisons’ works, Green Heart of Holland 1994–2001.

9. Helen Mayer and Newton Harrison

“Moments when reality no longer appears seamless, and the cost of belief has become outrageous”18.

When they started working together more than fifty years ago, Helen, a poet, senior academic in education and feminist, and Newton, an established visual artist, made the commitment to only make work that addressed environmental well-being. The Green Heart of Holland work resulted from an invitation from the Cultural Council of Southern Holland19. They note, with some amusement, that, as artists, they were contracted to save the Green Heart of Holland, an area of farmland of some 800 square kilometers, rich in wildlife and highly significant to the rural origins of cultural identity of the Netherlands, an unexpected and unusual call from a government body. The Green Heart is surrounded by the major cities of Amsterdam, Den Haag, Rotterdam, Utrecht, Dordrecht, Leerdam and Haarlem, known as the Randstad. It was now under threat from a proposed 230-billion-dollar development to create homes for 600,000 people that would invade the Green Heart and wipe out its precious ecological properties (Harrison and Harrison 2016, pp. 254–67).

What is important here is the shift that occurred as the Harrisons’ knowledge of the issues progressed. The initial impulse of the Dutch was to come at the problem from a human centered perspective: How many houses could comfortably be developed in the available space? The Harrisons reframed this question as, “What is the best way for an urban continuum to end and an ecological continuum to begin? Is there a way for this mutual beginning and ending to give advantage to both?” (Harrison and Harrison 2016, p. 261).

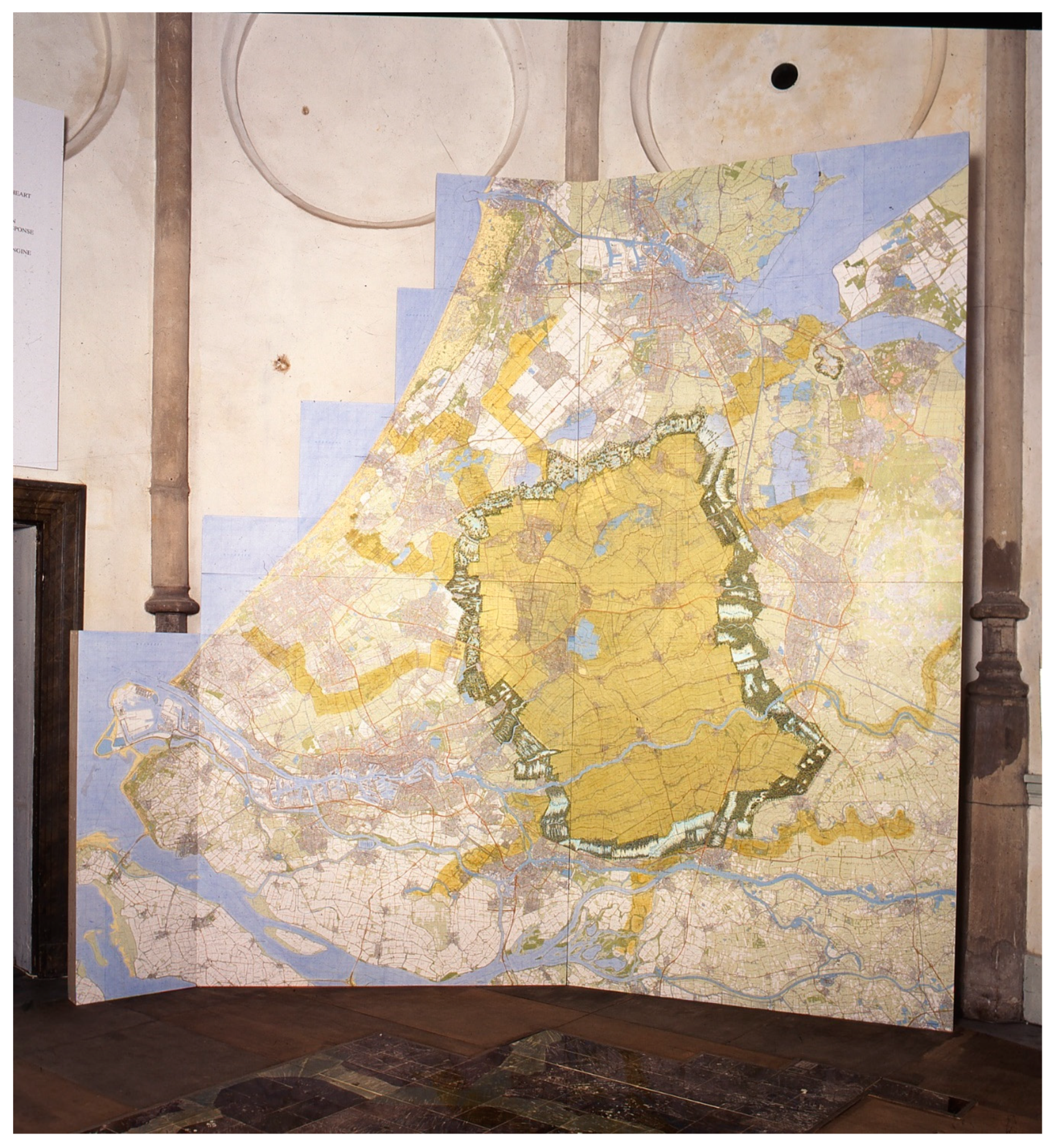

The Harrisons expressed a new proposal of a 2.4 square meter map of the Green Heart and the Randstad. They also printed the map backwards. In their public exhibition in a small chapel in Gouda, they placed both maps side by side, each offering different possibilities. The backwards map on the right not only accommodated a third of the proposed number of houses, but it also exposed the consequences of a thoughtless drift into the Green Heart. It broke the country into three parts and the Green Heart disappeared as an ecological niche (Figure 5). The Harrisons used ‘backwards’ printing because they believed the Dutch were designing their country backwards. Their reframing of the core question exposed this version of events as unnecessarily damaging to people and the environment alike (Douglas and Fremantle 2016b).

Figure 5.

Map of the Netherlands printed backwards and broken into three parts (Harrison and Harrison p. 259) (Courtesy of the artist Newton Harrison).

The counterpoint was a ‘forwards’ map, exhibited to the left of the first map. This preserved the Green Heart through the creation of a boundary biodiversity ring of 1–2 kilometers, and a series of biodiversity corridors leading out from the Green Heart into the developed, industrialized areas surrounding the cities of the Randstad. The second map shows how the required number of houses could be sensitively distributed in the spaces between corridors, allowing for even more development than had initially been requested, without diluting the unique character of each of the Randstad cities (Figure 6). The floor below the maps was made of Delft tiles imprinted with images from Google Maps of the area at a scale that allowed visitors to identify and stand on the ‘spot’ that they lived (Figure 7).

Figure 6.

Map of the Netherlands printed forwards with the proposal embedded (Harrison and Harrison, p. 259) (Courtesy of the artist Newton Harrison).

Figure 7.

Installation in Jerusalem Chapel, Gouda, The Netherlands (Harrison and Harrison 2016, p. 255) (Courtesy of the artist).

The Harrisons juxtapose two conflicted realities, one addressing the needs of nature through biodiversity and the other the needs of culture through housing. The contradictions are embodied in the same space in a stark and uncompromising way. The juxtaposition reveals the assumed inevitability of progress over nature to be nonsensical. It discloses new potentials that could be acted upon in quite practical ways. The Harrisons were not offering a solution to a problem, but a proposition. This is evident in the way they presented the work to the Dutch public in the form of an installation of architectural scale in which both perspectives confront the viewer in the same level of detail, effectively, as alternatives for careful consideration. The scale and imagery of the floor tiles invited inhabitants of the region to see themselves within the issues and as part of the decision-making process.

The Harrisons conceptualize this approach through the notion of conversational drift (Adcock 1992). Their work raises a discourse that is never completed and not in their control, but one that gathers momentum as it moves. Conversation drift frequently takes form as poetic text combined with large scale images.

The work first opened

in a small chapel in Gouda

where many groups came

and talked of this or that concern.

Many voted

most with favorable comment.

Thereafter

the work moved to exhibition spaces

in Delft and Zoetemeer

and other places.

There were many press articles

videos television presentations

by ourselves and by others on the team.

Of course

We could not know where

in this conversational mass

our Green Heart Vision would drift

in time and space

And then land.(Harrison and Harrison 2016, p. 265)

They later comment, in an almost disinterested way, that through a change of government, the project was stalled. Six years later, its principals were revisited and five years after that a drawing appeared in a pamphlet that was remarkably close to their original concept. The pamphlet argued that the Green Heart was one of the most critical spaces needing to be maintained in Northwest Europe, and this pleased them (Harrison and Harrison 2016, p. 267). In being presented as something of an aside, these remarks suggest that the outcome of the work, while significant, was not the most important aspect. It was the unfolding discourse and its unpredictability that would outlast the immediate situation of the work. They acknowledge the absurdity of asking artists (and not planners) to save the Green Heart, and they use the backwards printing of the map as an aesthetic form of absurdity.

10. To Recapitulate and Conclude

This article proposes the absurd in art as a possible approach of coping with the current environmental crisis. It is an exploratory attempt to address Latour’s challenge to artists to create new representations along with the emotional resources for us to cope with the terror of environmental change. It poses three questions. The first is concerned with how the absurd in art disrupts anthropocentric thinking. Drawing on histories of the absurd, including Jarry, Dada and Fluxus alongside examples in contemporary art, mainly of John Newling and the Harrisons, I show how absurd art appears in troubled times, subverting moments of extreme contradiction in which it appears impossible to think differently. It creates bizarre juxtapositions that expose and question conflicted, even dangerous, aspects of life which have become normalized. The power to unsettle in this form of art rests in disrupting the world of the viewer or spectator, positioning them as interlocutors in a new framing of events. Absurd art allows us to see the absurdity that is inherent in life and its institutions. It breaks open the possibility for us to see ourselves as part of a world that is unfathomable, beyond our control or comprehension. Newling and the Harrisons, among other artists, expose human systems and values to scrutiny and confront us with the stark truth that the way we think and what we value are currently undermining our capacity to survive. Their work manifests subtle forms of the absurd, although they may not violently attack systems of communication or create nonsense in the manner of earlier forms of absurd art. They are nonetheless anarchic in the way they harness the power of aesthetic experience to destabilize and question the authority of anthropocentric belief and rationality at moments of seeming paralysis.

The second question concerns imagining an alternative quality of relations between human beings and living systems that displace control with an openness to the implausible and serendipitous. The Harrisons give voice to an ecosystem under threat, flipping the normal hierarchy of value in which human development outrides any other consideration, creating a proposition that acknowledges co-dependency within natural systems. Newling gives a dead tree a place in art collecting, and composts highly valued artwork, again inverting the normal hierarchy of value upheld by the institution of art. Through these playful, and at times implausible, means they expose narrow self-interest to scrutiny.

The third question considers how the absurd in art functions alongside other knowledge domains such as the sciences. Newton Harrison shares Latour’s observation that artists are important to climate challenge.

Why Artists?

The term ‘representation’ is used in science to mean ‘standing in for’ in the way that Zalasiewiecz’ meter cube stands in for the Earth. Latour suggests that, although the sciences are imagined as abstract and without form, this is not the case. What the sciences do is reattribute life and meaning to things that are otherwise thought to be inert, bringing them into the realm of human attention and understanding. They do so through scientific papers that are, in fact, forms. It is through form that ways of knowing, ontologies, come to exist. In this way, the ‘inert’ is given the power to act (Coccia 2021). Zalasiewiecz’ meter cube works in this way. Art functions in a very similar way, bringing aspects of life into appearance in ways that provoke thinking and help us make life meaningful (Arendt 1978).Why not artists? Art is the court of the last resort—and our best hope. The evidence is overwhelming, and many people are indeed overwhelmed. But case after case that we have looked at all over the world, these issues have been looked at locally—we saw a crying need to find ways to talk about the problem at the scale at which it is occurring. That can be terrifying and discouraging, but for us it opens the door to creative possibilities.(Harrison and Harrison 2012)

Latour’s insight into form as a creative practice that is shared across all ways of knowing the world, is refreshing and frees us, allowing us to see the connections between art and science. He defines form building in terms of careful description, and foregrounds the arts as particularly well placed to describe the birth of a new kind of Earth.

Latour suggests that it is through form that the inert, as it appears to us humans, is able to speak. Deep observation and description and practices of care and attention characterize many artistic practices that address environmental collapse. Others reveal the world in its human-centered narratives of power and belief. If we apply Latour’s insight on form to absurdity in art, it enables the inert to ‘speak’ at particular moments of crisis and in a particular way, by means of the ridiculous. Absurd art displaces function with uselessness, logic with nonsense, control with serendipity and chance. We are drawn into a dialogue with situations that we assume to be ordinary, but are revealed to be beyond our normal ways of understanding the world. This larger world has other interests that are given agency in absurd art, such as the well-being of the web of life in the Harrisons’ work and the lemon tree/soil/composting in that of John Newling.…we are stripped of the capacity to describe because we are not where we thought we were …for this reason the arts in general—poetry, visual arts, theatre, cinema become so essential in this period.(Latour in Coccia 2021)

11. Coda

In commenting on earlier versions of this paper, Dr. Nil Gulari, researcher in Design and Business, succinctly summarized the significance of absurdity as both disruptive and transformative.

The practice of absurd art is very important as it amplifies a tragedy while retaining the love for life. It provides an exit, an imagination or a powerful will to invert this tragedy by harnessing the intrinsic power of absurdity. It drives hope and ideas for moving forward from the tragedy, increasing our response-ability, in Haraway’s sense (2016) (Gulari 2021).

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Acknowledgments

I would like to thank Jo Macdonald, Nil Gulari and Chris Fremantle for critical support in the development of the article and Gill Fremantle for kindly copy editing the text. Professors Helena Elias, Cristina Cruzero and Claudia Madera gave me the opportunity to test earlier versions at their conference What will it be? University of Lisbon November 2019.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

Notes

| 1 | Piepenbring, Dan. 2015. An inglorious Slop-pail of a play. 8 September 2015 The Paris Review. Available online: https://www.theparisreview.org/blog/2015/09/08/an-inglorious-slop-pail-of-a-play/ (accessed on 23 November 2021). |

| 2 | Dada and Jarry are by no means the only instance of absurdity in art. This can be traced back in the West to Classical Greece with Aristophanes, in particular The Frogs written around 405 BC. Dada directly influenced later developments in the Theatre of the Absurd of Beckett (1906–1989), Ionesco (1909–1994), Camus (1913–1960) and Artaud (1896–1948) and, later, the Fluxus movement, founded in 1960 in the United States by the Lithuanian/American artist George Maciunas (1931–1978) that continues today. |

| 3 | Zalasiewicz’ thought experiment is published in Critical Zones (Latour and Weibel 2020). |

| 4 | Future Library 2014-2114. Available online: http://katiepaterson.org/portfolio/future-library/ (accessed on 23 November 2021). |

| 5 | Owns Up 2013. Available online: https://art21.org/watch/new-york-close-up/mary-mattingly-owns-up/ (accessed on 23 November 2021). |

| 6 | Autoxylopyrocycloboros 2006. Available from https://www.themoderninstitute.com/artists/simon-starling/works/autoxylopyrocycloboros-2006/72 (accessed on 23 November 2021). |

| 7 | John Newling. Available online: https://www.john-newling.com (accessed on 23 November 2021). |

| 8 | The Harrison Studio. Available online: https://theharrisonstudio.net (accessed on 20 October 2021); The Center for the Study of the Force Majeure. Available online: http://www.centerforforcemajeure.org (accessed on 20 October 2021). |

| 9 | I supported the development of the Harrisons’ Greenhouse Britain 20069 in its early stages and co-convened The Deep Wealth of this Nation Scotland 2017–2019. I have written several articles on their work, some co-authored such as (Douglas and Fremantle 2016a, 2016b). Similarly with John Newling, I have written on this work extensively, most recently with Mark Hope in Ecologies of Value (Douglas 2020). |

| 10 | It is very clear from the diversity of approaches in Critical Zones that representation does not carry a narrow meaning as in ‘representational art’. Latour acknowledges in his subclause, “in all tenors of the word”. |

| 11 | I am grateful to Jo Macdonald, artist researcher, for supporting me in thinking through this difference. |

| 12 | I am drawing on Arendt’s notion of action in public life as composed of two activities: ‘leading/ beginning/ setting something in motion’ and ‘following through’ (Arendt 1998, p. 189) as particularly resonant of the way Newling works with participation. |

| 13 | TS Eliot’s The Wasteland (1922) is a modernist poem and part of the canon of English Literature. |

| 14 | Both curated by Francesco Manacorda, the latter in collaboration with the artist Wu Mali. |

| 15 | Curated by Latour and Weibel. |

| 16 | Back to Earth 2014-present. Available online: https://www.serpentinegalleries.org/whats-on/back-to-earth/ (accessed on 23 November 2021). |

| 17 | The book is unpaginated. I reference the examples through the numbering the publication uses for each entry. |

| 18 | Harrison and Harrison 1995. |

| 19 | The Harrisons’ work begins with an invitation from individuals and occasionally governments to look at particular experiences of environmental change in places under stress, including deforestation (The Serpentine Lattice 1993), rising temperatures (Peninsula Europe1-IV 2001–2011)), sea level rise (Greenhouse Britain 2005–2007), and glacial melt (Tibet is the High Ground 2007–2016) among others (Harrison and Harrison 2016). |

References

- Adès, Dawn. 1974. Dada and Surrealism. London: Thames and Hudson. [Google Scholar]

- Adcock, Craig. 1992. Conversational Drift. Helen Mayer and Newton Harrison. Art Journal 51: 35–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arendt, Hannah. 1998. The Human Condition. Chicago and London: University of Chicago Press. [Google Scholar]

- Arendt, Hannah. 1978. The Life of the Mind. San Diego, New York and London: Harcourt, Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Arp, Jean Hans. 1974. Collected French Writings. Poems Essays Memoirs. Edited by Marcel Jean. Translated by Joachim Neugroschel. London: Calder & Boyars. [Google Scholar]

- Brotchie, Alastair, and Mel Gooding. 1991. A Book of Surrealist Games. London: Redstone Press. [Google Scholar]

- Charbonnier, Pierre. 2020. "Where is your Freedom now?" How the Moderns became Ubiquitous. In Critical Zones: The Science and Politics of Landing on Earth. Edited by Bruno Latour and Peter Weibel. Cambridge: MIT Press, Karlsruhe: ZKM Center for Art and Media, pp. 76–79. [Google Scholar]

- Coccia, Emanuele. 2021. An Interview with Bruno Latour. Asymtote. Available online: https://www.asymptotejournal.com/interview/an-interview-with-bruno-latour/ (accessed on 28 July 2021).

- Douglas, Anne. 2021. Dada and the Absurd: Pedagogies of Art and Survival. In Knowing from Inside: Design for a Curriculum. Edited by Tim Ingold. London: Bloomsbury Press, pp. 189–211, in press. [Google Scholar]

- Douglas, Anne, and Mark Hope. 2020. Art in Co-relationship with Nature. In Ecology Works John Newling. Contributing authors Richard Davey, Anne Douglas, Mark Hope, Jonathan Casciani, John Newling and Jonathan Watkins. 2020. Edited by Aaron Juneau. Nottingham: Beam Editions, pp. 115–20. [Google Scholar]

- Douglas, Anne, and Chris Fremantle. 2016a. What poetry does best: the Harrisons’ poetics of being and acting in the world. In The Time of the Force Majeure. Edited by Helen Mayer Harrison, Newton Harrison, Petra Kruse and Kai Reschke. New York: Prestel, pp. 455–46. [Google Scholar]

- Douglas, Anne, and Chris Fremantle. 2016b. Inconsistency and Contradiction: Lessons in Improvisation in the work of Helen Mayer Harrison and Newton Harrison. In Elemental: An Arts and Ecology Reader. Edited by James Brady. Manchester: The Gaia Project, pp. 153–81. [Google Scholar]

- e-Flux Journal. 2019. Editorial. e-Flux Journal. October, p. 103. Available online: https://www.e-flux.com/journal/103/ (accessed on 21 December 2019).

- Fokianaki, iLiana. 2019. Narcissistic Authoritarian Statism, Part 1: The Eso and Exo Axis of Contemporary Forms of Power. e-Flux Journal. October, p. 301. Available online: https://www.e-flux.com/journal/103/ (accessed on 21 December 2019).

- Friedman, Ken. 1998. The Fluxus Reader. London: Academy Editions. [Google Scholar]

- Gasparin, Marta, Steven D. Brown, William Green, Andrew Hugill, Simon Lilley, Martin Quinn, Christophe Schinckus, Mark Williams, and Jan Zalasiewicz. 2020. The Business School in the Anthropocene: Parasitic Logic and Pataphysical Reasoning for a working Earth. Academy of Management Learning and Education 19: 385–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Girst, Thomas. 2014. The Duchamp Dictionary. London: Thames and Hudson. [Google Scholar]

- Gulari, Nil.Melehat. 2021. Audencia Business School, Nantes, France. Personal communication. [Google Scholar]

- Haraway, Donna Jeanne. 2016. Staying with the Trouble. Making Kin in the Chthulucene. Durham and London: Duke University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Harrison, Helen Mayer, and Newton Harrison. 1995. HELEN MAYER AND NEWTON HARRISON Nobody told us when to stop thinking (1987). In Theories and Documents of Contemporary Art. A Sourcebook of Artists’ Writings. Edited by Kristine Stiles and Peter Selz. Berkeley and London: University of Chicago Press, pp. 566–69. [Google Scholar]

- Harrison, Helen Mayer, and Newton Harrison. 2012. Introduction to the Center for the Study of the Force Majeure; Santa Cruz: University of California. Available online: http://www.centerforforcemajeure.org/#introduction (accessed on 29 October 2021).

- Harrison, Helen Mayer, and Newton Harrison. 2016. The Time of the Force Majeure. New York: Prestel. [Google Scholar]

- Jarry, Alfred. 1951. Ubu Roi. Translated by Toi B. Wright. London: Gaberbocchus Press. [Google Scholar]

- Jeffries, Stuart. 2021. Everything, All the Time, Everywhere: How We Became Postmodern. London: Verso Books. [Google Scholar]

- Kaprow, Allan. 2003. Essays on the Blurring of Art and Life. Edited by Jeff Kelley. Berkeley and London: University of California Press. [Google Scholar]

- Latour, Bruno. 2020. Seven Objections to Landing on Earth. In Critical Zones: The Science and Politics of Landing on Earth. Edited by Bruno Latour and Peter Weibel. Karlsruhe: ZKM Center for Art and Media, pp. 12–19. [Google Scholar]

- Latour, Bruno, and Peter Weibel, eds. 2020. Critical Zones: The Science and Politics of Landing on Earth. Cambridge: MIT Press, Karlsruhe: ZKM Center for Art and Media. [Google Scholar]

- Newling, John. 2008. The Preston Market Mystery Project. Preston: Harris Museum and Art Gallery. [Google Scholar]

- Newling, John. 2015. The Lemon Tree and Me. Nottingham: J.B.N. Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Obrist, Hans Ulrich, and Kostas Stasinopoulos, eds. 2021. 140 Artists’ Ideas for Planet Earth. Dublin: Penguin Random House UK. [Google Scholar]

- Okri, Ben. 2021. Artists Must Confront the Climate Crisis—We Must Write as If These are the Last Days. London: The Guardian, November 12, Available online: https://www.theguardian.com/profile/ben-okri (accessed on 15 November 2021).

- Stengers, Isablle. 2017. Another Science is Possible: A Manifesto for Slow Science. Cambridge: Polity Press. [Google Scholar]

- Tsing, Anna Lowenhaupt. 2015. The Mushroom at the End of the World. On the Possibility of Life in Capitalist Ruins. Princeton: Princeton University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Zalasiewicz, Jan. 2020. The Anthropocene Square Meter. In Critical Zones: The Science and Politics of Landing on Earth. Edited by Bruno Latour and Peter Weibel. Cambridge: MIT Press, Karlsruhe: ZKM Center for Art and Media, pp. 36–43. [Google Scholar]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).