Abstract

This article is an attempt to define the ambiguous specificity of artistic deflation in the sculpture of the Wroclavian artist Leon Podsiadły. At the outset, the author describes the principle of deflationist art and proposes a method of approach. She then discusses the “imperfections” within Podsiadły’s sculpture, the main manifestations of which include the use of common materials and mundane objects, secondary anti-mastery, and dememorization. These features coexist with well-thought-out composition, the inventiveness of the choice-making artist, and the creative fascination of unconventional artistic qualities, to which deflationist unlearning adds a unique slant. Seen from this perspective, Podsiadły’s deflationist caprice persuasively affirms the elasticity of the oscillation between the optics of modernism and postmodernism that defines his art. This oscillation can be seen, for instance, in those among his sculptures that were inspired by his stay in Africa in 1960s; in his “erotic” compositions; and in his installations of the 2010s in which he used the ready made. His “reductive” artistic experiments testify to a need for ironic distance; they individually gravitate toward the transgressive avant-garde and at the same time respond to the current trend of deskilling in art.

Keywords:

Leon Podsiadły; sculpture; Polish contemporary art; deflation; caprice; irony; modernism; postmodernism 1. Introduction

Deflation in art means the lowering or reduction of artistry. It introduces the principle of anti-mastery and of the de-perfectionalized product, which sanctions mundane materials as the most obvious media for artistic explorations1.

“Reductionist” art represents the paradigm of topical creation, located in postmodern culture, despite the fact that it has its roots in the artistic transgressions of the experimental avant-garde (Cubism and Dadaism), and also earlier in the ancient maxim of embarrassing negation popularized by Diogenes of Sinope2.

Deflationist caprice manifests itself in the work of Wroclavian sculptor Leon Podsiadły (1932–2020), a significant contemporary Polish artist3. His output gives evidence of the oscillation between modernism with its cult of artistic genius and artwork, which is unique in form and content4, and the postmodern affirmation of the anti-masterpiece, the de-sanctioning of talent and of the precision of artisanship in a bid to affirm the everyday and the common5. Podsiadły found freedom by departing periodically throughout his career from the modernist imperative to create perfect, masterful forms, at those times inclining toward the postmodern concept of the caprice. Furthermore, the creative “fall” from mastery can be seen as a condition for his modernist, if uniquely specific, perfection, becoming a necessary source of relief and a frequent point of departure for his creative explorations, sometimes even coexisting within a work alongside a perfect stroke of creativity. The deflationist caprice defines this artist’s contemporary sculpture, which undermines fixed formulas and has an unconventionally singular fascination with what is low, ordinary, natural, and biological. The paradoxical coexistence of modernist perfection and of deflation, which flirts with but never fully attains the category of postmodern anti-art, makes possible the distinctive style of transgression in Podsiadły’s sculpture.

My main goal throughout this study was to examine the artist’s deflationist strategy―so far overlooked by critics and scholars―in his spatial operations, consisting of the transgression and contradiction of conventions. To be able to undertake this task, I will avail myself of the methodological repertoire of modernism, chiefly of elements of contextual analysis. I will also draw from methods of compositional interpretation necessary in descriptions of visual representation. Occasionally, I will use a detailed formal-thematic analysis of chosen “reductionist” works of Podsiadły. The dominant postmodern investigative perspective will allow me to identify, among other features, the intentional stylistic inconsistencies of deflationist art, the relative replaceability of binary formal solutions, and the intertextual play with established artistic tendencies (D’Alleva 2005; Rose 2010).

2. Deflation

Deflation in art is manifested in the following permanent formal properties: technical impoverishment; rejection of conventionally aesthetic features of the work, to make it look uglier and less professional (Markowska 2019, p. 156); the choice of materials and techniques aimed at glorifying the abject (Kristeva 1982)6, the insignificant, and the common, for example, through the use of base materials (organic, destructible, and fragmented), objects of everyday use, and defective scrap (ready made, recycle-bound trash). By mobilizing anti-mastery and anti-authority, the artist expresses freedom as well as―to an extent greater than before―the transience and contextuality of his state and situation. Secondary anti-mastery inclines toward a radical change of the artistic strategy. Rejection of modernist artistry, however, involves making a special effort, the effectiveness of which can be understood as a specific type of success. The definitive nature of this cancelling is often dubious and not always ultimately desired, which adds extra emphasis to the ambiguity of deflation and its transgressive potential. The oscillations between the affirmation of mastery and its negation as well as between the cultivation of perfection and the blessing of incompetence and insignificance (Lascault 2011, pp. 37–52) are both indicative of a new quality of this tendency in contemporary art, which consists in the exploitation of the possibility of unlearning, understood as a different mode of learning. This balancing act allows the artist to learn something new and different than what he was given before to learn; it gives him the freedom to acquire what he wants and what life naturally offers (as, depending on the changing historical and cultural context, life keeps on offering new things, thus expanding the range of artistic exploration). Deflationist dememorization is thus aimed specifically at actual non-schematic existence, which makes it more life affirming and less pragmatic or theoretical.

The rejection of authority and the critique of authorship makes us aware of the unforgiving strictures of original artistic creativity, among them the artist’s compulsion, often cruelly unrealizable, to express his individuality through the bringing into being of artwork that is itself unique and radically autonomous. The ability to produce original work is not always within reach, however. It is often replaced by a refusal to work (Bourdieu 1995, p. 56) or by a reflexive repetition of mundane phenomena, or even of someone else’s work (plagiarism in art and parasitism, both of which are forms of derivative repetition). Another strategy consists of reductions in scale and of visibility, which entails fragmentation and mobility, disqualifying the modernist principle of artwork as a complete whole, immobilized in its representational and uplifting exposition. On the other hand, deskilling―the least visible feature of Podsiadły’s sculpture―ostentatiously rejects the masterly status of craftmanship in the execution and glorifies automatization, which cancels the validity-bestowing position of the creator and the unrepeatability of individual handicraft (Roberts 2010, p. 83)7. This is a consequence of the obliteration of the self-expression of the individual human creator in an era dominated by industrialization, in which the mutually dependent and constitutive roles of the eye and hand of the artist have been dismantled. Deskilling has also brought about a relegation of the virtuoso-like position of artistic creation to the level of the manufacture of desacralized products, thus negating the formerly valued work-prosthesis of modernism.

In Podsiadły’s spatial works, the presence of the above-mentioned manifestations of deflation, as related to contemporary art, is unobtrusive and incomplete; we can detect evidence of his singular fascination as traces within the dominant modernist compositional whole. In the work of this Wroclavian, “[t]he disjunction of the eye and hand from the world of signified elements” (Markowska 2019, p. 156) is dubious and his use of ready made objects manifests the ambiguous potential of the modernist-postmodernist form. The object trouvé, used as a spatial element in accordance with the sanctioned position of “high” art, relates to an artist’s conception and intuition; in agreement with the postmodern multi-vector nature of the artwork, it is connected with the multi-stage and multi-contextual nature of the production of the artifact as coordinated by a number of craftsmen. The process’s heterogeneity strips the object of its original function and rational application. In its final outcome, it leads to the production of a contemporary artwork based on a set of principles unrelated to the original function of the media. This type of artwork is afunctional and devoid of any logical relation to the everyday; it is dynamically changeable, with “vectors” of execution deriving not only from the artist himself, but from the stages of industrial production and from the participation, at various phases of the manufacturing process, of blue collar workers, who are regarded not as artists but as “simple” makers. This does not change the fact that a novel contemporary artwork is thus created―an ambivalent ready made object that testifies to the coexistence of two (discreet) paradigms.

Podsiadły exploits the stylistic transgressiveness of the mundane object by availing himself of deskilling, albeit selectively and never in its pure form. Strategies of deflation allow him to dodge the conventional classification of authorial sculptures as well as break away from modernism, which in the PRL era existed in the form of thematically neutralized state art. These strategies gave him an opportunity―despite the fact that he was probably unaware at the time that they represented the revolutionary paradigm of postmodernism―to experience a necessary freedom in his process of artistic creation. The potential of deflations seems to be important in Podsiadły’s work in that it allows the democratization of art, illustrative of the principle pointed out by John Roberts: “every ready made, anywhere, can have a meaning” (Roberts 2010, p. 83). The resulting artistic freedom makes it possible for the artist to be creative in any place and use anything, unrestrained by the rudimentary and fixed relation, for a given sign8, between the produced meaning (signifié) and the form ascribed to it through its visual representation (signifiant). The democratism of deflation seems to be simple and uses a maximal perspective: Every person is capable of creating whatever they want, however they want, and using whatever they want. Podsiadły’s sculpture consistently stops short of questioning the elite status of art. Repetitions, deflationist automatism, and the rejection of mastery are for him, on the one hand, little more than passing caprice, and on the other, have given him a necessary, if episodic, freedom within a creative practice defined by modernist standards. The “deflationist episode”, as a periodic feature of his career, supplies us with tools that allow us to examine the possibilities and limitations of art and to find out to how far an artist can go in exploring a creative medium in a manner that is iconoclastic toward the established canon9. Deflation was especially attractive to Podsiadły due to its potential for fashioning new forms, and this gave the sculptor the opportunity to consciously express his attitude toward the realities of contemporary life. The cult of form-fashioning, so essential to modernism, thus acquired, for Podsiadły, a new dimension, filled with things that were common, mundane, and naturally related to everyday existence. However, with Podsiadły, the deflationist features of art never became a value that dominated and totally defined his sculpture.

3. The Methodology of Deflation

Considering the methodology with which to capture deflationist art, it is worth noting that deflation intentionally plays with the recipient’s perception of a “reductionist” work of art. Here, we can clearly see a distortion of the traditional conception of mimesis in that the creative operations defined by deskilling can be described neither in terms of imitative reproduction (imitation in an artistic medium) nor as the reproduced object itself (the ordinary object). Based on the practice of appropriation, this type of art does not attempt to ironically prolong the existence of the plagiarized work (as, for example, is the case with Marcel Duchamp’s picture L.H.O.O.Q (Mustachioed Mona Lisa, 1919). Instead, it uses the ambiguity of the everyday object, an object which itself has been fashioned though a multi-vector process of manufacturing ostensibly unrelated to “art”. Deskilling leads to the widening of the artist’s “‘arc of inner vision or perception’ running from the hand to the retina” (D’Alleva 2005, p. 112). This process was part of the body of practices that inspired the methodological shift in art studies postulated by Norman Bryson, a leading representative of reception theory. This new methodological paradigm was critical toward the psychology of art, which focuses attention on the artist, and thereby on isolationism and the exterritoriality of the creative space; reception theory instead affirms the post-structural appreciation of the receiver as well as the social and historical space of the reception process. Thus, instead of limiting the reception of art to the sphere of the relationship between the artist and the work, deflationist artwork encourages the appraisal of the artist–receiver relationship, opening new contextual and conceptual spaces. This opening, however, does not undermine the role of the deflationist artifact itself as the main broadening factor for the experience of reception.

Moreover, deflationist art can be regarded as a consequence of an essential shift in the realm of normative studies, especially those related to Clement Greenberg’s formalism. This shift brought about a discrediting of the cult of perfect form (the modernist idea of the work’s autonomy and stylistic uniqueness) with the aim of stressing the need for a redefinition of aesthetic categories, which is to say, the need for a paradigm shift that would nullify the formal value in favor of discourse about art. Deflationist art deemphasizes the “normative criterion of quality” (Foster 1996, p. 57; italics in the original) in order to prioritize the experience of the receiver. In deflationist art, this change is not one-dimensional, but occurs as an equivalent coexistence of verified values on which a new hierarchy has been imposed. In this way, deflation treats as equally valid the formal value of the artifact and the need for a reexamination of this value’s definition. Deflation does restore the interest in form, but in a form that is not perfect, a form with a reduced criterion of value, shedding light on the need to find an appropriate term for this imperfect form.

Contemporary deflationist art makes a stand against “the institutional autonomy of art” (Foster 1996, p. 52), against what the formalist avant-garde sought to preserve, and what the transgressive avant-garde sought to change. The transgressive avant-garde of the 1960s returned to Russian constructivism and the French Dadaism of Duchamp, which anticipated it and launched the contemporary use of deflation in art. It seems that Podsiadły, with his “reductive” experiments in sculpture, placed himself squarely among the ranks of the transgressive avant-garde as an inheritor of Duchamp’s deflationist proposal. This positioning paved the way for his mature works of deskilling in the era of postmodernity, which began in Poland after 1989.

4. Caprice

It is difficult to ignore the significative proximity of the concepts of caprice (lightness) and deflation (freedom of artistic negation). The whimsical “lightness” (Popiel 2018, p. 107) of deflationist art makes possible a departure from constrictive norms through the insolent nonchalance of transgression. The need for what is “low” and at once light is a permanent feature. Dubbed “goofy carelessness” (Gombrowicz 1986, p. 246), caprice allows one to endure hardships, even traumatic situations, and thus the restrictive system of ideologized reality. Since deflationist lightness tends to be goofy, Podsiadły, in order not to seem ridiculous, created his deflationist curiosities either in hiding or after the era of regime restrictions. Moreover, he always did so periodically, which enabled him to return to consistently modernist work. Reductive artistry in the PRL era was frowned upon by the state and by the artistic establishment, with its practice risking serious repercussions. Restrictions within the Wroclavian PWSSP (State College of Fine Arts) against faculty members regarded as dissenters were indicative of the threat, as faculty regarded as wayward in their artistic pursuits were censured, regardless of the accomplishments of their unique artistry. Podsiadły constantly skirted this line but ultimately managed to stay within institutionally sanctioned boundaries of acceptability, his temporary suspension of serious art (compliant with the officially recognized standards of good taste) running parallel to exemplary academic work and manifesting itself in still-modernist, but nonetheless transgressive experiments performed outside the college classroom.

Deflationist “lightness” in art is based on paradox and is found at the meeting place of contradictions. Goofy lightness coexists with wisdom, and, by generating distance, adds a sense of balance and reasonability. An imperfect work resembles a complement to, or continuation of, a perfect product, but does so in a critical manner, on the basis of an objective valuation of “low” and “high” features of art and by neutralizing the difference between them as constructed according to a given set of values. The opposition between weight and lightness metaphorically captures the tension between modernist sculpture10 and its continuation in postmodernity. Deflationist sculpture affirms the sculptor’s right to play through its use of “light” (mundane) material. The “weighty” effort expended in mastering a noble medium has been replaced by the limiting of artistic effort and the use of a ready made object produced by a “common” artisan. It is impossible to ignore here the antithetic binaries that define modernist and deflationist art and thus anticipate post-modern anti-conventionality (i.e., idea vs. caprice; weight vs. lightness; noble material vs. everyday object; originality vs. appropriation; the seriousness and wisdom of authority vs. prank and play (goofiness); durability and univocal limitation (potentially associated with the violent context of political realities) vs. brittleness and evanescence (connotatively close to freedom)). The modernist freedom to create, attained thanks to masterly effort, is opposed to deflationist artistic freedom as allied to “the subversive doing-nothing” (Markowska 2019, p. 173). Similarly, modernist freedom grounded in the creative use of convention is opposed to a freedom based on the resolute rejection of convention (on the deconstruction of convention through deactivating operations involving lowering and ridicule). Creative freedom is the permanent and shared characteristic that relativizes the exclusion of these binaries; despite its various definitions in relation to different paradigms, it constitutes the necessary point of departure for art.

Podsiadły’s work confirms the existence of the line separating the above tendencies; his creations are also a testimony as to how irresistible the temptation to cross that line may be. Modernist sculpture and deflationist postmodernism are both founded on the principle that freedom is essential to artistic creativity. However, each movement understands the concept of freedom differently, either as remaining within the confines of fixed convention (that of “high” art) or outside it (anticipating the arrival of a new paradigm). The coexistence, in Podsiadły’s work, of both sets of values stems from the fact that each prioritizes artistic freedom, a basic, underlying quality that eases the normative differences between them. It is difficult to ignore the fact that within the context of Podsiadły’s generation, the artist does not wholly conform to the postmodern conception of the uniform world, adjusted thanks to the transversal capacity for transition (transgression) and exchange. Nonetheless, the deflationist manifestations of his creative activity relate to the “complementary projects of the human condition” (i.e., to the model of the ironist corresponding with that of the wanderer) as ascribed to it by the theorists of postmodernism: Italo Calvino (Calvino 1988, chapter “Lightness”, pp. 3–29) and Milan Kundera (Kundera 1984; Kundera 1988, pp. 59–74, 74–78).

5. The Deflationist Caprice of Podsiadły-as-Ironist

According to Calvino, the attitude of an ironist is characterized by lightness of thinking, that is to say, by a distance to oneself, by “calling into doubt the individual ‘I’, the world and the network of mutual connections” (Popiel 2018, p. 123). Lightness―the deflationist reduction of the quality of perceived and represented reality―is possible thanks to self-parody and irony, and especially thanks to a manner of thinking that violates established conventions. Thus understood, the deflationist artist challenges the system with a grotesque-prophetic style, as defined by Witold Gombrowicz, and with humor and the capacity for laughter, which vanquish the sin of seriousness (weightiness). In the spirit of the “grotesque aesthetic of caprice” (Popiel 2018, p. 143), this kind of artist performs acts of denuding disillusionment, and glorifies the destructive power of insignificance. This manner of conduct rejects, if only ostensibly, the model of the modernist artist as prophet. Seriousness and hope are still present in the optics of the grotesque, despite their being complemented by antithetical qualities added by the artist in the creative processes of modification, addition, and compilation. Similarly, the ironic artist of deflation is capable of being inventive, with this power stemming less from production and creation and more from the specific use of the already existing ready made object. The distance deployed by Podsiadły-the-ironist is distinctive and still bears the mark of his individuality. The permanent feature of his creative persona is this critical distance to the aesthetics of modernism, a distance also resulting from the postmodern philosophy of lightness―caprice.

This distance―the intensity of which varies at different stages of Podsiadły’s artistic output―is evident in his form-shaping work. It allows him to use for his material a fragment rather than a whole, an alien element rather than a matching one, and even an object from nowhere, one of suspicious, mundane, and trivial provenance, rather than one of high quality. This distance allows, on the principle of creative experimentation, “reduction”, and de-refinement of the work as possible artistic choices bearing transgressive potential. Ironic deflation incorporates an ill-matching element, one that undermines the modernist principle of the coherent artistic product, which precipitates the reduction of its quality on the principle of ridicule, flippancy, and surprise. The deconstructive potential of irony intensifies the ambiguity of the work and heightens the impression of the carefree spirit of the artist in his interactions with the conventions and limitations of artistic exploration. Paradoxically, Podsiadły’s ironic deflation, despite being inclusive of the function of lowering the work’s value through the whimsical “reduction” of artistry, also plays up artistry by emphasizing its needfulness. However, Podsiadły’s deflation simultaneously suggests its own multi-contextuality, and the possibility of its occurrence in de-refined areas.

Podsiadły’s entire output as a sculptor is characterized by the impossibility of total coherence understood as the defining feature of modernist artwork, and by the abandonment of the assumption that any work can ever totally reach the status of “completeness”. For this reason, in his conception of sculpture, Podsiadły takes into account the necessity of ruptures and interspaces, and of the need to use unconventional solutions to make possible the existence of a work formed from ill-matching elements. The use of lack and incompletion, as a condition for the execution of a sculpture, facilitates the deflationist “reduction” for the sake of the production of the work, in the face of institutional and compositional challenges. Moreover, Podsiadły was partially deaf, a fact that also influenced his work. The partial deafness of the artist necessitates the fragmentary reception of a sequence of sounds, and―metaphorically speaking―familiarizes the artist with the distorted version of the original, with the grotesqueness and consequent facetiousness. In the case of Podsiadły, this means favoring the creative use of imperfection, for which the point of departure is lowering, deficiency, and incoherence. The facetiousness of incomplete sound―and, more generally, of every faulty whole―is suggestive of the deconstructive power of laughter. Laughter exerts an adaptive influence, but also creates a distance toward any sealed formula regarded as perfectly coherent and self-sufficient.

The manifestation of existence, always present in Podsiadły’s radically non-representational sculpture, brings it closer to deflationist art, which has its roots both in, and which coexists with, life, stepping down from the pedestal of seriousness and elitist perfection. Podsiadły thus becomes an artist-ironist through his experimentations with the whimsical lightness of noncanonical artistry. Deflationist lightness manifests itself in, for example, the use of ill-matching materials that loosely gesture toward totality; a piece of crumpled fabric attached to a heavy rock, or an industrial metal grid arbitrarily added to a meticulously polished block of wood. Deflationist “reduction” can thus be seen in the ironic use of new materials that contradict the classicist quality of the fine materials that they accompany. These new materials are mundane, even trashy, and generally of disputable aesthetic quality; as such, they destroy the uniqueness of the traditional shape, which, according to convention, was given physical form by a noble material. The everyday materials suggest the openness of the sculpture, the possibility of its entering into dialogue with mutable contexts and similarly mutable receivers. Juxtapositions of ill-matching media also create the opportunity for the artist’s dialogue with himself to take place. This departure from “high” art opens a vantage point upon new concepts and methods of execution as well as the chance for the artist to reevaluate his own artistic needs and to see the lightness of transgressive explorations in the anti-conventional rejection of genius and nobility.

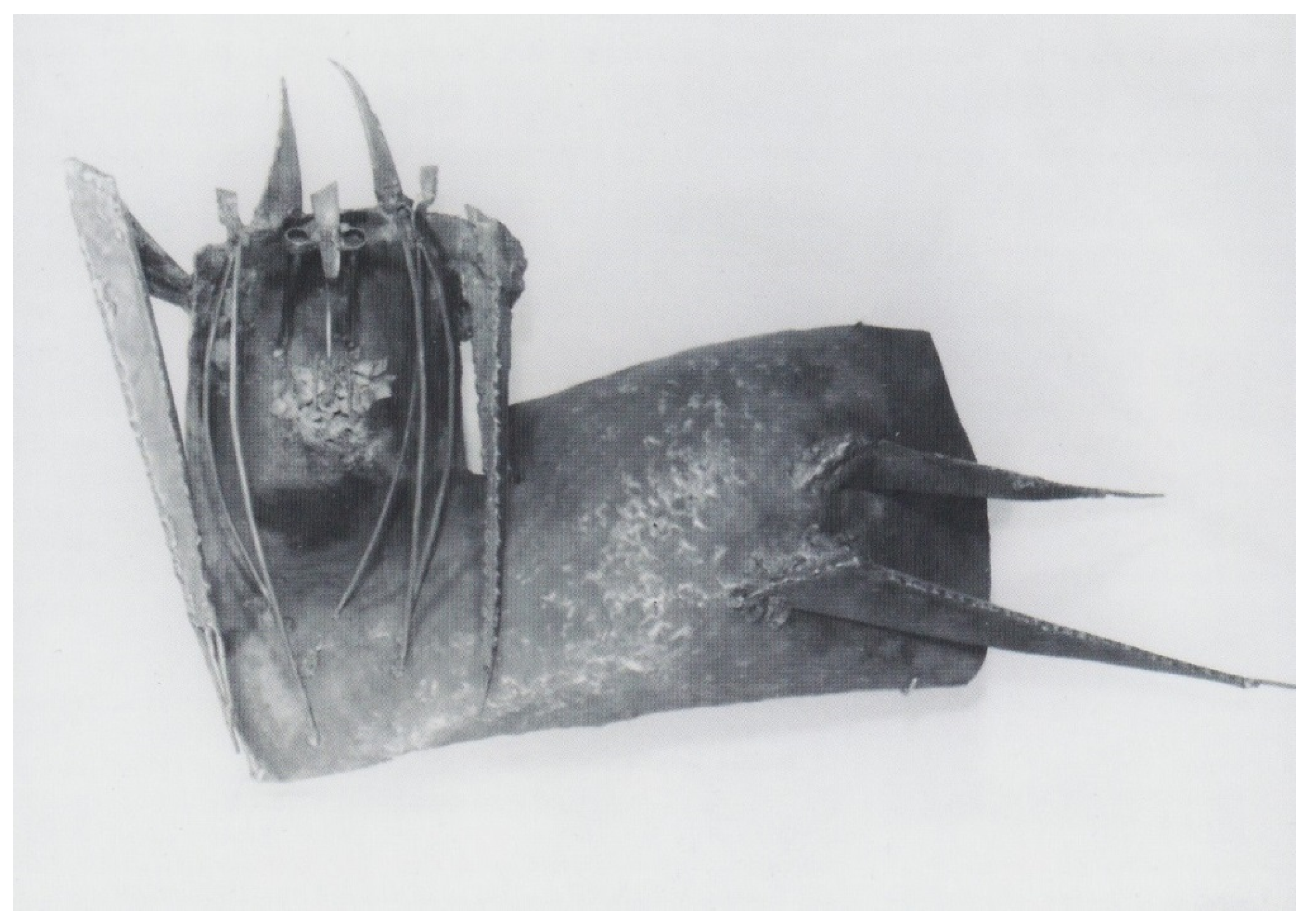

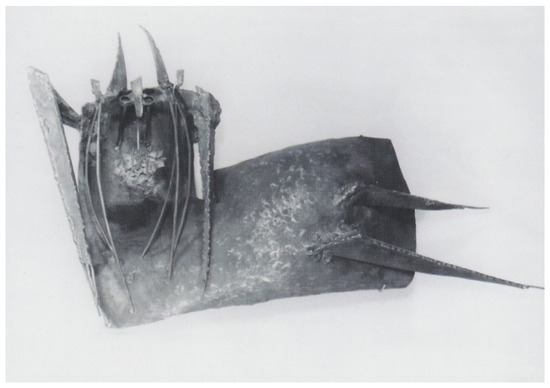

The ease with which Podsiadły avails himself of deflationist transgression is related to his childhood spent in France, a country which represented an artistic environment far more liberal than the one found in Poland at the time. Initially interested in two-dimensional art―drawing, among other art forms―Podsiadły took lessons from watercolor painter Zygmunt Biernacki. When he returned to Poland in 1947, Podsiadły took up technical training, graduating from technical secondary school with a certification in long-distance transmitters (Wąs 2012b, p. 2), a subject much more practical than art, and which guaranteed a steady job. These early experiences did not vanish without a trace, but instead, filtered through the artistic medium, found expressions in his later affirmative approach to the mundane in his deflationist art. Therefore, when encouraged by Jan Chwalczyk, he began his studies at the Wroclavian PWSSP under the tutelage of Borys Michałowki in 1952, and his works reverberated with echoes of his former technical education. His 1959 Nocny gość [Night Visitor] (Figure 1), a sharp angular form fashioned from welded iron sheets, bears not only the influence of the British sculptors Lynn Chadwick and Kenneth Armitage (Jarosz 2014, pp. 78–104; Moore 1981, pp. 76–78), but also testifies to his technical skill in producing clever configurations out of tiny sharp metallic elements and linear arrangements resembling fine electric cables. Such distinctive elements, evident also in Trzy gracje Avanti [Three Graces Avanti], 1958 and Biała dama z Zagórza [The White Lady of Zagórze], 1963 as well as the frequent use of common materials (including metal, corroded steel, worn timber, and fabric) and of other unartistic techniques (for example, pouring cement into holes made in the earth) express Podsiadły’s leaning toward the practical context of common existence. These interests were accompanied by his continuing personal partiality for canonical sculpture that was also explicitly transgressive and went beyond established conventions by pointing out new artistic possibilities (Antoine Bourdelle’s Heracles, 1909, among other works). Podsiadły took notice of sculpture that anticipated his creative peregrinations including those that involved the reduction of conventional artistry, and these predecessors leave their traces in his unique explorations.

Figure 1.

Leon Podsiadły, Nocny gość [Night Visitor], 1959, metal. After: (Wąs 2012a, p. 33). Photo used with the permission of the artist’s family.

At the outset of Podsiadły’s artistic career, we can already observe his pursuit of deflation through his exploration of the anti-classicist use of his materials as well as the exploitation of the potential of ugliness in terms of porosity, roughness, and unevenness of texture. Despite working within the tradition of the minute observation of natural forms for inspiration, a hallmark of modernist sculpture in accordance with the credo of “search for a platform in nature” (Jarosz 2014, p. 83)11, Podsiadły also made consistent adjustments to this attitude through the use of the deflationist conventions of anti-mastery and visual imperfection. Podsiadły’s Master’s Project, completed for his degree (1958) (Figure 2), represents two heavily deformed figures fashioned in a material suggestive of biological decay (rotten tree bark). Here, Podsiadły makes gestures toward structural abstraction by using common, corruptible materials that imply rotting and “vanity” (worthlessness), thus creating the possibility for the piece to be understood in relation to “turpism”12 without fully entering that sphere. In this way, he sought to distance himself from the modernist cult of perfection, understood as the preservation of the traditional aesthetic of shape and expressed in a meticulously fashioned matter as a product of the unique eye–hand–object relation, bearing a stamp of validation conferred by the artist’s creative act.

Figure 2.

Leon Podsiadły, diploma work (Centaur grający na flecie dla Muzy [Centaur Performing on a Flue for the Muse]), 1958, stone. After: Ośrodek Dokumentacji Sztuki Akademii Sztuk Pięknych im. Eugeniusza Gepperta [the E. Geppert Academy of Art and Design] in Wrocław. Photo used with the permission of the artist’s family.

From the very beginning of his artistic career (his Master’s Project and Zwiadowcy [Scouts] of 1964), Podsiadły tended to reject the concept of realistic proportions in his portrayals of the human figure and to deprioritize the presence of man in representational art. At first, this seemed to be a form of modernist experimentation with the media itself, a way of testing form-fashioning possibilities; later, it found its expression in the mundanity of the object-material and the normalcy of the existence surrounding the artist. In Podsiadły’s sculptural explorations, there is a distinct shift away from the universally human and toward the individual, personal, common, and private, as communicated by the use of everyday items, like shovels, strings, etc. Consistently noticeable is the preservation of the modernist principle of focusing on the individual, but now the individual is the artist himself, with a new authenticity and relatability made known to the viewer through the revelation of the desacralized space of the artist’s existence. The focus is on the creative individual in any artistic movement defined by deflation (i.e., in an era of exploring the artistic potential of anti-mastery and of the reduced sanction of artistry).

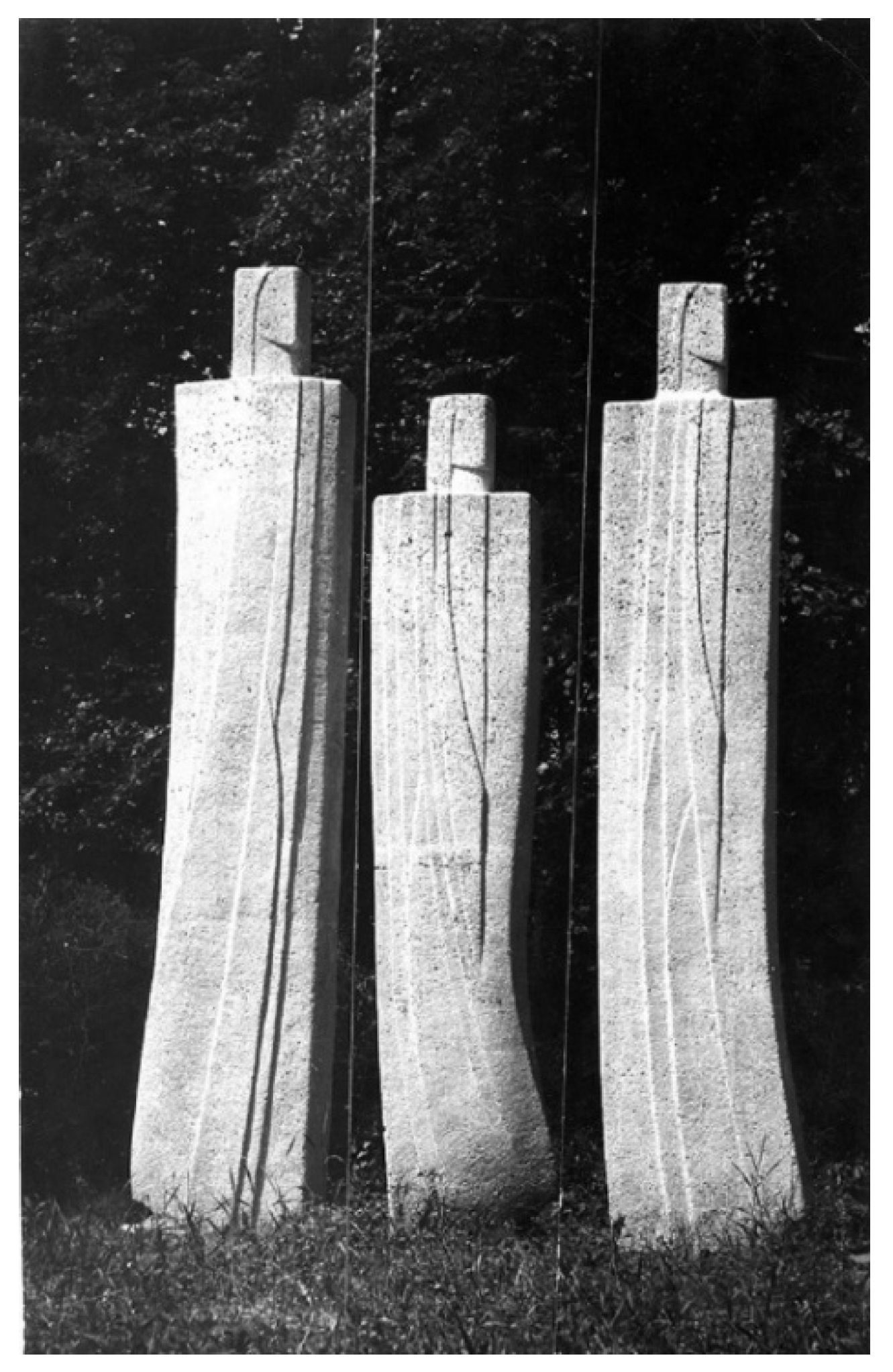

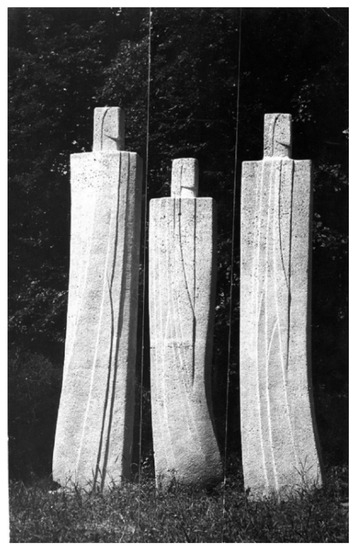

Despite his deflationist excursions, Podsiadły always returned to the paradigm of modernist perfection in sculpture, as testified by, for instance, Figury medytacyjne [Meditating Figures], 1978 (Figure 3), reminiscent of caryatids from Pomnik Czynu Powstańczego [Memorial to the Silesian Uprising], 1949 (Figure 4)13 by the “Nestor” of Polish sculptors Xawery Dunikowski. Podsiadły’s sculptures abound in allusions to this multigenerational modernist, who offered a strongly individualized version of contemporary monumental art. The work of Dunikowski is an idiosyncratic combination of influences from three main periods: the Młoda Polska (Young Poland) movement of the turn of the 20th century, the interwar period of the 1920s and 1930s, and the postwar period following 1945. Dunikowski’s school was one of the three schools of sculpture—alongside the studios of Michałowski and Apolinary Czepelewski (Makarewicz 2006, pp. 83–125)—which operated in the State College of Fine Arts (PWSSP) in Wrocław after World War Two14. Podsiadły’s work is not a literal continuation of the work of this Cracovian master; the nearly two-and-a-half-meter-tall Meditating Figures. Morning are distinctive in their subtle elongation of the radically simplified female figure and their equally simplified representation of faces, too indistinct to qualify for portrait recognition. The generalization of the figure and faces is a significant point of departure from the cubistic geometrization of Dunikowski’s caryatids from the Memorial, which, despite some generalization of the facial area, maintain features identifiable as belonging to idealized versions of representatives of certain social groups15. Similarly, the terseness and finesse of Podsiadły’s human figures are skillful and preserve the spirit of modernist handicraft. Other works by Podsiadły often concentrate on small spatial forms and explore common materials (Wąs 2012b, pp. 5–6), making possible a variety of sculptural explorations, consistently bringing the artist closer to the intensified transgressions as defining features of art.

Figure 3.

Leon Podsiadły, Figury medytacyjne. Poranek [Meditating Figures. Morning], 1978, white concrete with aggregate, Osobowicki Cemetery in Wrocław. After: Ośrodek Dokumentacji Sztuki Akademii Sztuk Pięknych im. Eugeniusza Gepperta [the E. Geppert Academy of Art and Design] in Wrocław. Photo used with the permission of the artist’s family.

Figure 4.

Xawery Dunikowski, Kobieta śląska [Silesian Woman], 1949, granite, pillar decorating sculpture, part of Memorial to the Silesian Uprising (1946–1955), Saint Anne Mountain. Photograph by Karolina Tomczak.

Within Podsiadły’s career, the African period spanning the years 1965–1970 was especially important as relating to his familiarization with the deflationist reduction of artistry. Before Podsiadły’s trip to Africa as a lecturer in sculpture and drawing at the École Nationale des Arts at Métiers, in Conakry, Guinea, he had already started to make steps in the direction of deflation, an inclination that would become more pronounced as a result of the influences he encountered there. The discovery of the artistry-“reducing” properties of plasticine for sculpture inspired Podsiadły’s execution, in this material, of studies for future works (e.g., Ptak [Bird], 1965 (Wąs 2012b, p. 7; Makarewicz 1999, p. 87)), and most probably also the grotesquely-deformed figures of Król [King] and Król Ubu [Ubu King] (two versions of 1965, fireclay). The use of plasticine is significant, because, on one hand, this medium is perfectly plastic (which is especially important in the process of working spatial forms), and, on the other, it serves as the material for nonprofessional spatial objects made by children―hence its deflationist infantility. This experimentation with the elasticity of plasticine, alongside simultaneous, progressive work in clay and increasing skill in the craft of ceramics (participating, for example, in plein air sculptors’ gatherings in Bolesławiec)16, ushered Podsiadły into a phase in which he discovered the potential of the mundane medium, which was developed and transvalued in the reality of Guinea. The African period in his career is reminiscent of the modernist fascination with “virginal” exotic art, associated with the perceived simplicity of stylistic choices (purity of color, clarity of composition, the use of natural materials without further processing, etc.) preserved in non-European cultures. Importantly, the African period also put Podsiadły in touch with “the closeness of this art to existential needs” (Wąs 2012b, p. 7) and to the sphere of the everyday, which Podsiadły construed as a form-fashioning value.

Symptomatically, Podsiadły’s works inspired by his stay in Africa in the second half of the 1960s only appeared a few decades after the conclusion of his journey. This testifies to a process of development, which culminated in his feeling mature enough to transcend the mastery-oriented paradigm in European sculpture. The modernist cult of accomplished craftsmanship, unfavorable to the breaking of established aesthetic convention, did accept the idea of formal transgression, but required that it be limited to the fixed boundaries that were part of contemporary standards for professional art. The delay in the advent of Podsiadły’s African-inspired works also testifies to the fact that increased artistic maturity goes hand in hand with increased need for deflation. The greater the artist’s experience within the strictures of modernism, the greater the impulse to contradict or reject that formula, and the greater the courage to abandon it, if only for a few works produced during a creative episode, a breach in an otherwise perfectly consistent career in modernist art. Another issue relating to Podsiadły’s time in Guinea concerns the anxiety of the Polish art establishment, throughout the PRL period, toward artistic otherness. In the 1960s, the State College of Fine Arts in Wrocław did not tolerate instances of visibly “different” types of talent, or what the College considered to be frivolous treatments of convention. Censure stemming from this intolerance could be meted out in the name of maintaining the ideologized model of artistic creativity as it existed within the communist state whereas in fact, it may have been a more personal rebuke by the College for an artist’s open rejection of the universal formula. The sad case of Antoni Mehl bears a testimony to how unfair and drastic this kind of exclusion could be; Mehl was expelled from the Wroclavian College as a gesture of public ostracism for artistic activities that were criticized as inimical to socialist realism (Jeżewska 1995, p. 6). Another ruling dogma at the college during the PRL era was the modernist paradigm of master-oriented art, neutralized in terms of content and therefore regarded as safe by the authorities. Due to the high level of artistry, which gave it international sanction, this paradigm legitimized the communist regime. Non-modernist deflation was anti-system, and hence unwelcome. An artist who came to disapprove of the constrictiveness and conformity of modernist art would find it safer to express that disapproval privately, through non-public art, or to postpone the creation of such pieces indefinitely. Podsiadły fully expressed his African lesson of distance toward the European formula of modernist “high” art only after the political transformation of 1989.

An untitled work of 2012 (black oak, wire mesh, marble) (Figure 5) is one of several sculptures that bear the mark of Podsiadły’s stay in Africa, characterized by deflationist “reduction” preserved in a frame of formally modernist explorations of anticonventional exotic and basic formal and stylistic solutions. In part executed in wood resembling iroko (black African oak), this sculpture redefines the European model of perfection in the spirit of minimalist artistry and basic values. This can be seen, for example, in the precision of the execution of the marble cubes and the meshing around the slats of wood. The specificity of the African origin of the image, evocative of “the cargo-carrying pirogue, long and noiselessly moving upon a silent river” (Wąs 2012b, p. 8), vanishes; for although the impression that inspires creation (perhaps, for example, the glimpsing of a pirogue) is still valued in its relation to the modernist concept of the fashioning of form, the materials speak equally loudly of the principle of reaching for what is common, and therefore deprived of the status of art. The artist still executes his work in the spirit of contemporary mastery, of the exquisitely carved form. He uses contrasts: between materials (marble vs. porous wood); conventions (new avant-gardist minimalism vs. exotic archaic art); and qualities (refinement vs. natural simplicity, which annuls European schematism). In this way, the receiver is offered, in terms of form-fashioning, a perfect expression of the work’s gesture toward deflationist transgression.

Figure 5.

Leon Podsiadły, untitled, 2012, black oak, wire mesh, marble. Photograph by Stanisław Sielicki. After: (Wąs 2012a, pp. 30–31). Photo used with the permission of the artist’s family.

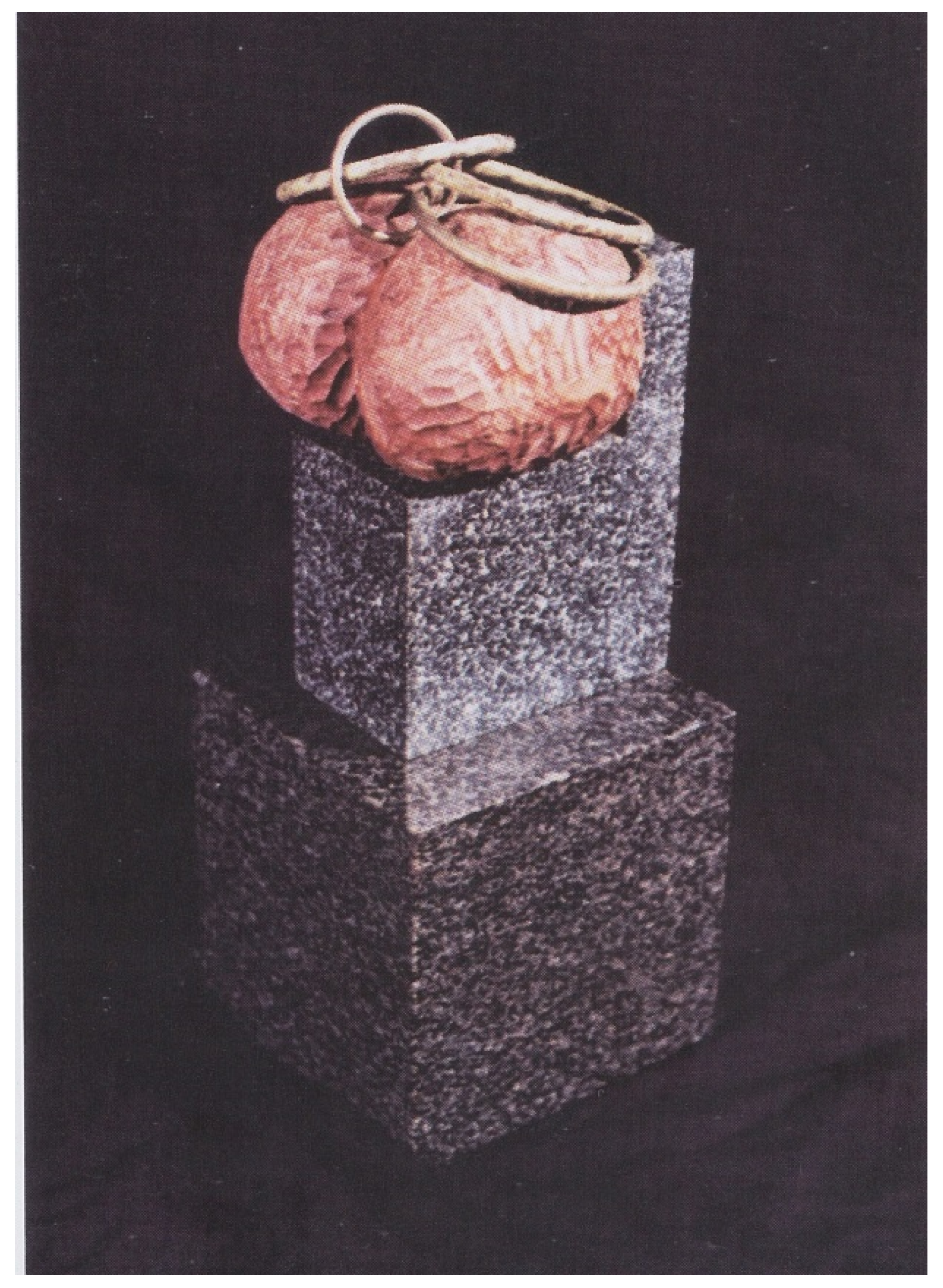

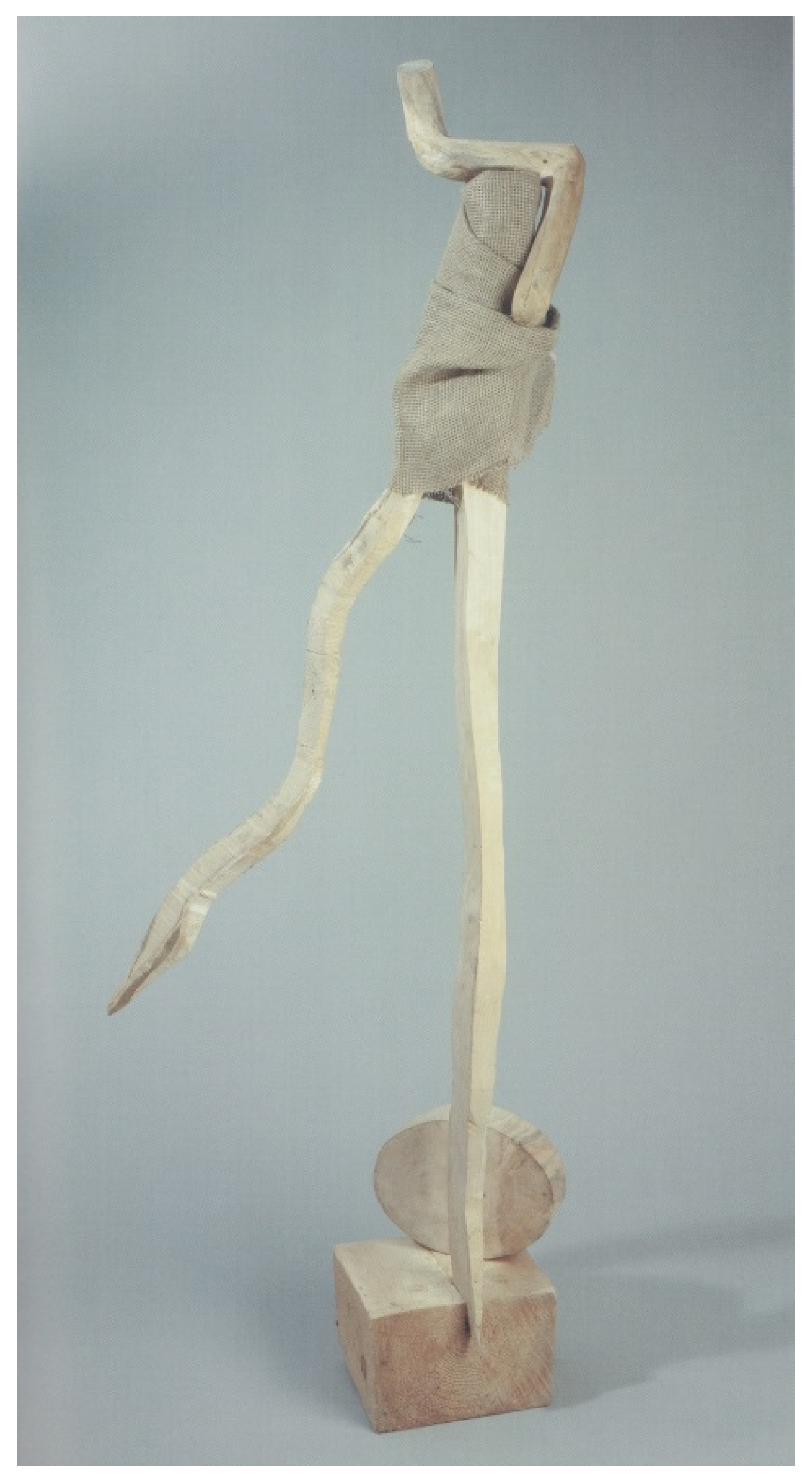

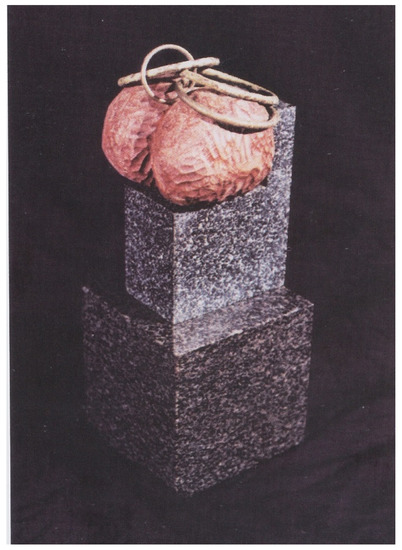

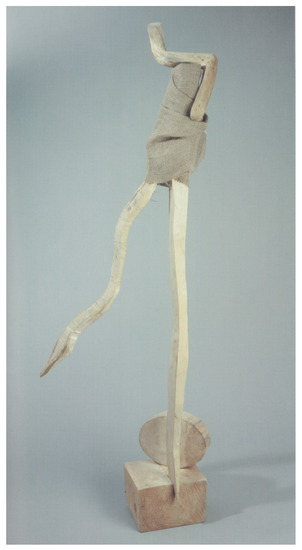

In the installation Alpha Yaya Diallo (2006 or the 1990s17; brass, wood, stone) (Figure 6), identification of the Guinean musician―“a singer and a multi-instrumentalist” (Wąs 2012b, p. 8)―bearing this name, who ostensibly inspired the work, seems to be less important than the more interesting transposition of this inspiration onto a spatial form. The work is exceptional in its antithetical use of the raw unambiguousness of cold marble, arranged in two geometrical steps, and the organic roundness of two adjacent ovals crowned with gilded rings. Once more, Podsiadły is able to achieve substantial expressiveness by taking advantage of the contrasts afforded by the materials themselves: a homogenous surface, smooth and polished; a corrugated surface, concave and convex, impressionistically generating dynamic chiaroscuro effects; neutral non-colors (white, black, and gray); saturated full colors (bright red and golden). Podsiadły retains here the modernist use of metaphor―the “sign”, in the de Saussurean sense. The podium ironically elevates the representation of the African singer’s genitals, adorned with a multiplied crown. The podium exposes this element of the composition, which is difficult to recognize in the finished work, but which relates to the actual figure of the musician. The man has been expressed through his sculptural equivalent with the help of a few solids of questionable artistic quality, thus playfully engaging an established formula. Despite the recognizable representation of these common organic objects, drawn from everyday existence, and the de-sanctioning laughter conveyed through the manner in which the theme has been suggested, we can also see here something that unquestionably belongs to the sphere of the mundane, yet with no use of any one element that would constitute deflationism in its purest form. Imitations of African totem poles are executed in a similar manner, testifying to the European artist’s play with the style of African ritual sculpture (e.g., Paleta idola [The Palette of an Idol], 2012; black oak, linden, steel). The formal conception of another work, entitled Za progiem―radość [Behind the Threshold―Joy], 2012 (wood, fabric) (Figure 7) is another of Podsiadły’s African artistic explorations. Here, Podsiadły completely abandons noble materials and contents himself with wood and a sackcloth bag, a gesture that appreciates the low origin and the organic quality of the material, as is typical of art associated with folklore. The “low” medium has been endowed with positive meaning and there is a suggestion of the joy brought by a departure from the formula of masterly sculpture preserved in a permanent and noble material. The work connotes a dance of joy expressed in an animated nonrepresentational form, a disobliging composition featuring gnarled branches only slightly manipulated by the artist. In these spatial forms, sentimentally hearkening back to the unpretentious context of African reality, Podsiadły reveals his growing and increasingly emboldened fascination with creative reductions of conventional quality.

Figure 6.

Leon Podsiadły, Alpha Yaya Diallo, 2006 or 1990s, brass, wood, stone. Photograph by Stanisław Sielicki. After: (Wąs 2012a, p. 41). Photo used with the permission of the artist’s family.

Figure 7.

Leon Podsiadły, Za progiem―radość [Behind the Threshold―Joy] 2012, wood, fabric. Photograph by Stanisław Sielicki. After: (Wąs 2012a, p. 25). Photo used with the permission of the artist’s family.

In the same year, Podsiadły sculpted ambiguous “erotic” works, in which he used female sensuality in the spirit of feminist-inclined sculpture, reminiscent of, among other artists, Maria Pinińska-Bereś’s pink objects and tiny furniture18. Podsiadły reedits the female stylistic code into a masculine equivalent that is ironically erotic and that deflationistically deconstructs the received formula. These spatial objects (e.g., Halka [The Slip], 2012 (metal, wood, fabric), Figure 8) show female sensuality from the perspective of a male, who leaves his own stylistic stroke in the carelessly prepared wooden slats, juxtaposed for contrast with the delicate pink slip. The editing is based on irony, understood as a drastic juxtaposition of different qualities. This carnivalesque inversion of roles, which reformulates the femininity of modernist sculpture into a sensual sculpture executed by a man, showcases a characteristically Duchampian reduction, a cockeyed quotation of the mimetic qualities found in modernist art. The modern “feminist-inclined” sculpture of Pinińska-Bereś, in its diversionary renditions of the patriarchally-limited female problematic, uses a particular aesthetic, despite the fact that the mawkish beauty of the pink objects found in women’s everyday reality also gives it an ironic expression. Podsiadły’s sculpture, superimposed on Pinińska-Bereś’s pattern, is antithetical in its choice of materials (unpolished wooden slats and wires) and shape (careless juxtaposition of supposedly randomly found pieces of wood put together with the help of a panel of rectangular wire lattice). The slip is the decisive element, introducing femininity into the composition. The deflationist reduction of Podsiadły’s artifact is evident in his transvaluing reinterpretation of the feminist-inclined sculpture of female sculptors of the PRL era, executed on the principle of allusion and anti-aesthetics (the slip is wrinkled and the wood rugged). Podsiadły’s sculpture presents―critically, jokingly, and from the male point of view―cliches (patterns, characteristic motifs) of the sanctioned sculpture of feminizing modernism. Podsiadły attains the irony of distance through his deflationist editing. In addition, he exposes and demystifies existing formulas through the use of cheap materials and by assuming a male, “unlearned” perspective.

Figure 8.

Leon Podsiadły, Halka [The Slip], 2012, metal, wood, fabric. Photograph by Stanisław Sielicki. After: (Wąs 2012a, p. 101). Photo used with the permission of the artist’s family.

Striptease, 2012 (metal, wood, fabric) (Figure 9)―another of Podsiadły’s “erotic” works―is equally perverse and mocking, but at the same time human and devoid of the aesthetic polish that is typical of canonical art. Dadaists, the earliest uncompromising apologists of the reduction of sanctioned aesthetic quality, used the human body and sexuality to express their deepening appreciation of the potential for transcending artistic boundaries and exploring spaces not yet wholly penetrated by art. They also reconsidered nudity, formerly, in the history of art, associated primarily with a feature of ancient deities and heroes or with charming odalisques as represented through the prism of the patriarchal gaze. Thanks to their understanding and practices devoid of prudishness, nudity became an aspect of non-binding mundanity and of release from the conventions of official space. The naked phallus has a power whose source is not only that of critique and deconstruction (Leszkowicz 2012, pp. 256–58); it is also suggestive of mundane nudity that governs private life as a basic biological energy. Podsiadły’s phallus already approximates the transgressive encroachment upon the space of the “low” while at the same time remaining natural and wholly human. The image of this member expressed in a deformed and gnarled piece of wood is still organic and sensual, which is emphasized by the red fabric, awkward and dangling off the edges. Again, a perceptive receiver might here point to the ambiguous sublimation of masculinity represented in a shape that is both defective and subtle through the use of the fabric, which points in the direction of modernist sublimity despite the general reduction of artistic expression.

Figure 9.

Leon Podsiadły, Striptease, 2012, metal, wood, fabric. Photograph by Stanisław Sielicki. After: (Wąs 2012a, p. 102). Photo used with the permission of the artist’s family.

A continuation and partial consequence of the earlier instances of the “reduction” of conventional artistry within Podsiadły’s career are works that belong within the trend of postmodern deflation, exhibited in 2019 (November 7–December 2) at the Entropia Gallery in Wrocław in an exhibition called “On i Ja” [“He and I”]. In this exhibition, Leon Podsiadły showed his work alongside that of his son Dominik (b. 1967), who is an independent visual and multidisciplinary artist19. Installations prepared for this event were the elder Podsiadły’s most distinct expressions of anti-mastery, mundanity, and de-memorization to date. While Podsiadły’s deflationary activities in the communist era focused on the gradual annulment of the convention of differentiation20 (the basis of modernist art) and the inclusion of what was incompatible with modernism’s ethos of exclusivity (anticipating postmodern art), then the appearances of deflation in his art after 1989 display the experimental use and expansion of compositional strategies within postmodern art at large in the late 1960s. These unifying solutions belong to the anti-champion style typical of deflationary art, embedded in the common and characterized by, among other things, the use of everyday materials, repetitions of formal motifs and procedures, and simplified composition. In democratic Poland, this deflationary style is used by the artist more efficiently and more often, but invariably with originality, which underlines his faithfulness to modernist values and the goal of creating something new.

A testimony to the maturity of Podsiadły’s deflation, as manifested after the political transformation in Poland, is found in the installation Razem [Together], 2019 (Figure 10), presented at the above-mentioned exhibition. It is composed of three brooms, all with laminated paper placards, each one of which displays the word “together” in one of three languages: English (together), German (zusammen), and French (ensamble). In deciding to multiply identical objects, Podsiadły ironically refers to conceptualism and jokingly quotes Duchamp’s earlier ready made. He also exploits a category typical of post-modernism, put forward by Italian literary critic Gianfranco Contini, which denotes universal levelling and relates to the equality of beings and the cancellation of hierarchies as features of the postmodern homogenous world (Popiel 2018, p. 121). In a linguistic description of reality, enumeration and syntactical and compositional parallelism are the key elements of the production of the effect of levelling-off21; the equivalent in art is usually provided by the multiplication of identical items. Podsiadły uses this unifying strategy by providing an artistic enumeration that relates to an identical ready made object. This allows him to subversively express his attitude to avant-garde art as well as to the potential of the mundane. He thus succeeds in excluding the modernist metaphysics of the artist’s eye and hand in a superbly effective manner. Only now, in 2019, does Podsiadły seem to accept the idea that deskilling is allowed, but even so permits himself only sporadic and incomplete forays into this area, remaining faithful to modernist experimentation with artistic, yet highly customary, media. He uses a spatial object whose traditional definition undermines the aesthetic value in contemporary art (Markowska 2019, p. 156) due to automation and the affirmation of perishable material, which negates the cultivated durability of the traditional artifact. Thus, on one hand, the artist performs an ostentatious cancellation of the aura of exceptionality clinging to modernist artwork and manifests the antimetaphysics of the relation between (the artist’s) hand and the “handiwork.” On the other hand, he proposes a novel metaphysics of the creative process, grounded through the transgressive modernist transvaluation of experience and a multi-contextual, parallactic22 view on artistic tradition.

Figure 10.

Leon Podsiadły, Razem [Together], 2019, ready made (brooms). Photograph by Andrzej Rerak. Photograph shared courtesy of Entropia Gallery and with the permission of the artist’s family.

The Duchampian Obiekt kinetyczy [Kinetic Object], 2019 (Figure 11), featuring a kinetic object (a moving record player), confirms Podsiadły’s unceasing play with the formulas of pre-WWII avant-garde sculpture and the experiments with spatial forms which, at that time, were regarded as revolutionary. The allusion is suggestive of, among other things, the kinetic sculpture of Naum Gabo and Antoine Pevsner, which in representing the speculative variety of Russian constructivism (Kotula and Krakowski 1985, pp. 273–80) explored the potential of movement as a principle organizing compositions of pure shapes. As Kinetic Object demonstrates, modernist conventions of spatial art are still present in Podsiadły’s creative consciousness in 2019, but are expressed in the work’s distance to them, emphasized through jest and the deconstructing lowness of formal execution. The slight undulation of the wooden stick or twig inserted into the surface of the record player distorts the semiotic relation between the signifié (the meaning of the record player) and the signifiant (the form of this device) (D’Alleva 2005, pp. 28–32), thus subversively changing and singulatively decoding the conventional interpretation of the relationship, which finally produces a novel object-thing of contemporary art. If artistic deflation is deconstructive, then here this power is especially intense, namely as a transformation or/and deformation of the ready made object, already belonging to the realm of the mundane, executed by a still-active artist but now through a mastery-rejecting interference, which distorts the faultless hand-eye correlation as the validating principle of modernist art. It is just this wavy wooden stick, at once from nowhere and everywhere, which makes possible the escapist, and thus liberating, creative irony in relation to the pre-WWII avant-gardes: that of constructivism, with its focus on perfection through emphasis on formal autonomy, and that of Dadaism, with its mocking of the purity of the masterly shape through the irreverent rejection of tradition. Podsiadły also references here the post-war modernist sculpture (Moore’s, Armitage’s, Chadwick’s, minimalism, and conceptualism). He also comments on his own work, existing for many years in relation to all these trends on the basis of masterly repetition and inspiration, but without the especially intense distance, representing creative individuality, which appeared only toward the end of his career. Within the elements of postmodern deflation (which as a rule limits individualism) embodied in Podsiadły’s sculpture created after 1989, a degree of individualism (a trait associated with modernism) is paradoxically still present, at times dominant; the individual characteristics of the artist are even expressed through the anti-master’s composition of everyday materials.

Figure 11.

Leon Podsiadły, Obiekt kinetyczny [Kinetic Object], 2019, ready made (gramophone, twig-wooden stick). Photography by Andrzej Rerak. Photograph shared courtesy of Entropia Gallery and with the permission of the artist’s family.

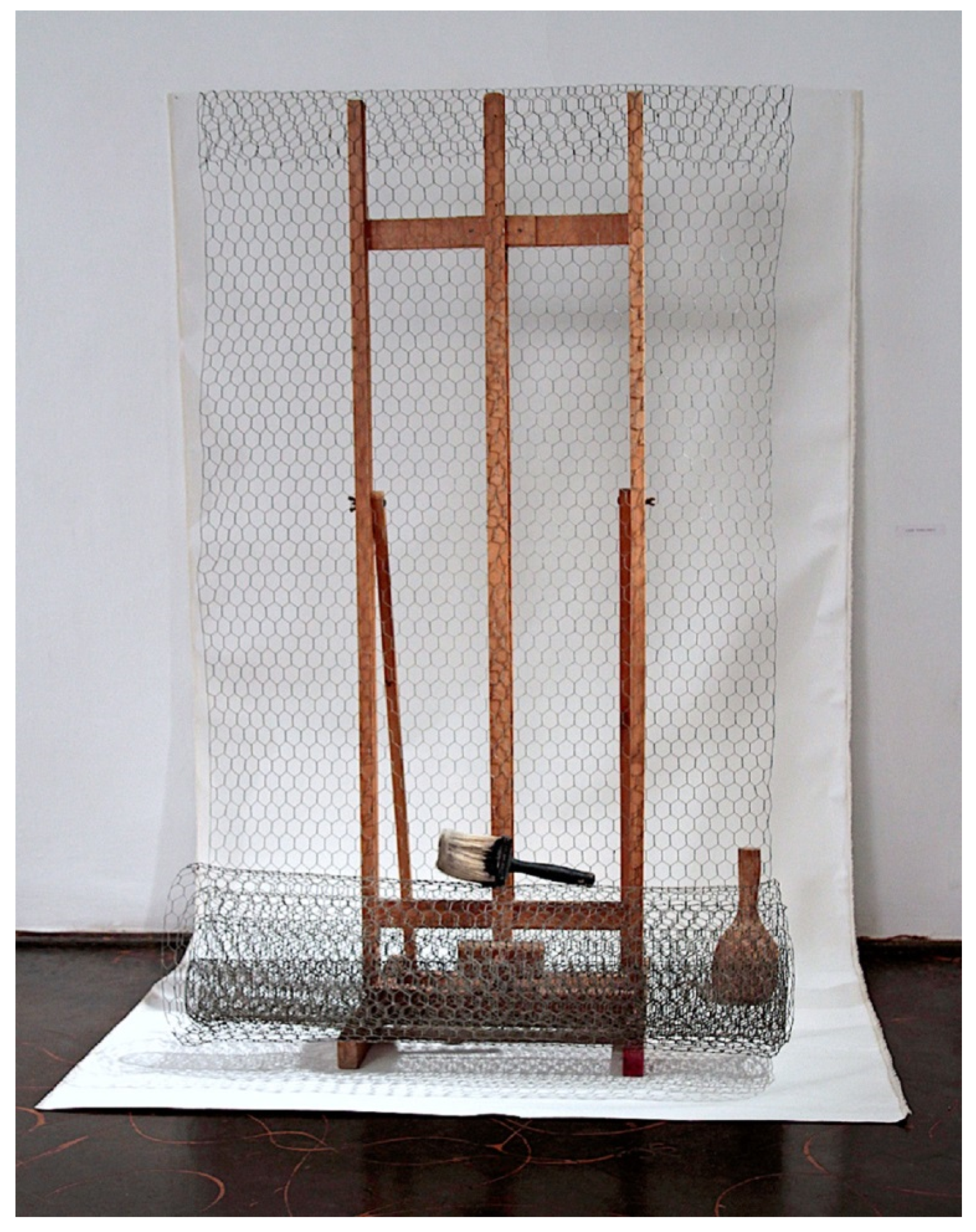

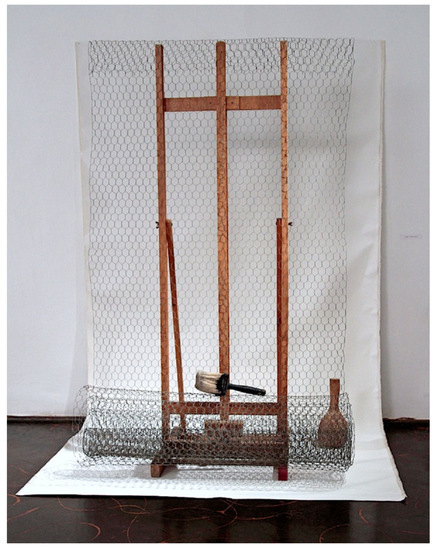

In the installation Sztaluga obiekt [Easel Object], 2012 (Figure 12), displayed in the same exhibition, Podsiadły point-blank and ostentatiously juxtaposes different artistic codes: conceptual, in exposing the minimalist form of an object and in suggesting the unfixed relationship between its form and meaning; and also Dadaistic, with its powerful banalizing gesture of covering an easel with chicken wire, a parodistic reference to the interior of an unimportant utility closet. Podsiadły brings to the fore the object, and at the same time additionally renders it mundane by shoving it into a non-artistic context. Paradoxically, the above-mentioned feature of the artist’s individuality is still visible here, namely in the contradictory juxtaposition of different materials (wood with the frequently-used chicken wire and a mundane object; here, an extra-wide housepainter’s brush from a home-improvement retailer), and also the rejection of their incompatibility with the help of the unifying idea of constructedness (i.e., the bestowal of a compositional arrangement on the participating elements), an act which of itself also grants the items’ semantic weight. Easel and brush remain the two sacred tools of an artist, despite the fact that the easel here has only partially been preserved; the levitating brush is off-putting its suggestion of the aesthetically-void smearing of paint over the walls of some room; the accompanying lone jug, located randomly, it would seem, in the background, is just a modest echo of a classical still-life. Their deformed and incomplete appearance gives art, as it used to be conceived, a new, contemporary context. This context changes art itself in that the art becomes the reflection of its context, according to the universal principle that the medium of art is more responsive than any other human endeavor in conveying the dynamism and multifariousness of historical and cultural space. Currently, art also reflects the process of desacralization (i.e., the affirmation of mundanity and of rendering-common). This most changeable feature of contemporary reality has found its strongest representation in deflationist art. Podsiadły shows this, but he also, subversively, retains a sentimental relationship with the art of bygone times, which ambiguously marks his deflationist works with an indelible stigma of “high” creativity.

Figure 12.

Leon Podsiadły, Sztaluga obiekt [Easel Object], 2012, ready made (easel, brush, chicken wire, jug). Photograph by Andrzej Rerak. Photograph shared courtesy of Entropia Gallery and with the permission of the artist’s family.

In Podsiadły’s deflationist work, postmodernism thus blends with modernism. Despite the ironical penetration of sacred artistic conventions, we can still detect in it the presence of the dominant creative gesture, which towers over what has sustained destruction. The sculptor holds ambiguous authority and mastery over the destabilized formulas. Thus, art continues to be art; it does not turn into an inherent part of the mundane despite the deconstructive sabotage and the desacralizing distance.

6. Self-Aware Oscillations

Deflationist caprice in Leon Podsiadły’s sculpture convinces us of his perpetual oscillation between the perfection of modernist art and the deflation of postmodernism with its reduction of artistic value. The attempt to ascribe to Podsiadły the attitude of the ironist has suggested the similarity of his idea of art to a personality type that dominates our “surfacy” postmodern world. However, Podsiadły’s gradual departure from the idea of perfect modernist art does not, after all, lead to identifying one paradigm with which to define his output. It is a result of the smooth interpenetration of these tendencies, which testifies to their status as cultural constructs, arranging but also blurring those nuances, apertures, and cracks that an analysis of his work identifies as essential. In the work of this sculptor, there is a noticeable difficulty, of which the artist himself may not have been fully aware, in accepting the deflationary dispersion of the metaphysics of hand and handicraft typical of art. The artist’s modernist roots are ultimately too strong, and therefore his departures into the realm of transgression and anti-mastery are revealed as instances of evanescent, if necessary, deflationist caprice. This oscillation between values, themselves relative, testifies to a dominant need within Podsiadły for a lowering of the paradigms of artistry and for the rendering-common of the image of the artist as an elevated being; moreover, it also testifies to the imperative the creative “breath of fresh air”. After all, deflationist art is still creation, and as such, as an echo of the avant-garde cultivation of form-fashioning, it is conditioned by the present-day context of art and contemporary life23.

Funding

The University of Silesia in Katowice funded this publication.

Acknowledgments

All visual materials were used with the permission of Magdalena and Dominik Podsiadły (children of the deceased artist).

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest. The founding sponsors had no role in the study’s design, in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data, in the writing of the manuscript, or in the decision to publish the results.

References

- 3 kobiety. 2011. Maria Pinińska-Bereś, Natalia LL, Ewa Partum [Exhibition Catalogue]. Edited by Ewa Toniak. Warszawa: Zachęta Narodowa Galeria Sztuki. [Google Scholar]

- Antkowiak, Zygmunt. 1985. Pomniki Wrocławia. Wrocław: Zakład Narodowy im. Ossolińskich. [Google Scholar]

- Bourdieu, Pierre. 1995. The Rules of Art. Genesis and Structure of the Literary Field. Translated by Susan Emanuel. Stanford: Stanford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Buchloch, Benjamin Heinz-Dieter. 2014. The Dialectics of Design and Destruction: The Degenerate Art Exhibition (1937) and the Exhibition international du Surréalisme (1938). October 150: 49–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calvino, Italo. 1988. Six Memos for the Next Millennium. Cambridge: Harvard Univ. Press. [Google Scholar]

- D’Alleva, Anne. 2005. Methods and Theories of Art History. London: Laurence King Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Danto, Arthur C. 1997. After the End of Art. Contemporary Art and the Pale of History. Princeton: Princeton University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Dominik Podsiadły. 2020. Wrocławski Kongres Kultury, 30.11.2020―4.12.2020. Available online: https://kongres.kulturawroclaw.pl/kandydaci/dominik-podsiadly/ (accessed on 25 February 2021).

- Dziamski, Grzegorz. 1996a. Awangarda w plastyce. In Od awangardy do postmodernizmu. Encyklopedia kultury polskiej XX wieku. Warszawa: Instytut Kultury, vol. 6, pp. 47–75. [Google Scholar]

- Dziamski, Grzegorz. 1996b. Postmodernizm. In Od awangardy do postmodernizmu. Encyklopedia kultury polskiej XX wieku. Warszawa: Instytut Kultury, vol. 6, pp. 389–402. [Google Scholar]

- Foster, Hal. 1996. The Return of the Real. The Avant-Garde at the End of the Century. Cambridge and London: The MIT Press. [Google Scholar]

- Gazda, Grzegorz. 1996. Awangarda. In Od awangardy do postmodernizmu. Encyklopedia kultury polskiej XX wieku. Warszawa: Instytut Kultury, vol. 6, pp. 21–32. [Google Scholar]

- Gombrowicz, Witold. 1986. Dziennik 1961–1966. Kraków: Wydawnictwo Literackie. [Google Scholar]

- Grubba-Thiede, Dorota. 2016. Nurt figuracji w powojennej rzeźbie polskiej. Warszawa: Polski Instytut nad Sztuką Świata, Toruń: Taco. [Google Scholar]

- Jarosz, Andrzej. 2014. Inspiracje brytyjskie w rzeźbie wrocławskiej. Quart 31: 78–104. [Google Scholar]

- Jeżewska, Maria. 1995. Tata, mama i ja. Rodzina Mehlów [Exhibition Catalogue]. Wrocław: Muzeum Narodowe we Wrocławiu. [Google Scholar]

- Kotula, Adam, and Piotr Krakowski. 1985. Rzeźba współczesna. Warszawa: Wydawnictwa Artystyczne i Filmowe. [Google Scholar]

- Kristeva, Julia. 1982. Powers of Horror. Translated by Leon S. Roudiez. New York: Columbia University Press, [Polish translation: Kristeva, Julia. 2007. Potęga obrzydzenia. Esej o wstręcie. Translated by Maciej Falski. Kraków: Wydawnictwo Uniwersytetu Jagiellońskiego]. [Google Scholar]

- Kundera, Milan. 1984. The Unbearable Lightness of Being. New York: Harper & Row, Publishers, Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Kundera, Milan. 1988. The Art of the Novel. London: Faber & Faber Limited. [Google Scholar]

- Lascault, Gilbert. 2011. Eloge du peu. In Marcel Duchamp. Tradition de la rupture ou rupture de la tradition? Paris: J. Clair, Hermann, pp. 37–52. [Google Scholar]

- Leon Podsiadły. 1977. Od linii do przestrzeni [Exhibition Catalogue]. Strzelin: Galeria “Skalna”. [Google Scholar]

- Leon Podsiadły. 1985. Leon Podsiadły. 1985. Frottage, collage. Czarno-białe i w kolorze [Exhibition Catalogue]. Edited by Jerzy Ryba. Text by Maria Łubieniecka. Wrocław: Galeria na Ostrowie. [Google Scholar]

- Leon Podsiadły. 2006. … piony i pionki…, Andrzej Klimczak-Dobrzaniecki. …tapety, dekoracje…―malarstwo [Exhibition Catalogue]. Wrocław: Galeria Ogniwo. [Google Scholar]

- Leszkowicz, Paweł. 2012. Nagi mężczyzna. Akt męski w sztuce polskiej po 1945 roku. Poznań: Wydawnictwo Naukowe Uniwersytetu im. Adama Mickiewicza. [Google Scholar]

- Makarewicz, Zbigniew. 1986. Wrocławskie rzeźby i rzeźbiarze wrocławscy. Rzeźba Polska 1: 61–82. [Google Scholar]

- Makarewicz, Zbigniew. 1999. Od portretów Antoniego Mehla do antropoidów Christosa Mandziosa. Wrocławska rzeźba figuralna w latach 1945–1999. Rzeźba Polska 8: 70–93. [Google Scholar]

- Makarewicz, Zbigniew. 2006. Bez postumentów. O rzeźbie wrocławskiej. In Wrocław sztuki. Sztuka i środowisko artystyczne we Wrocławiu 1946–2006. Edited by Andrzej Saj and Elżbieta Łubowicz. Wrocław: Agencja Reklamowa i Drukarnia Kontra, pp. 83–125. [Google Scholar]

- Maria Pinińska-Bereś. 1999. 1931–1999 [Exhibition Catalogue]. Edited by Bożena Gajewska and Jerzy Hanusek. Translated by Inter-Text Translations. Kraków: Galeria Sztuki Współczesnej Bunkier Sztuki. [Google Scholar]

- Maria Pinińska-Bereś. 2011. The Space Embodied [Exhibition Catalogue]. Tekst by Izabela Kowalczyk. Translated by Szymon Nowak. Poznań: Galeria Piekary. [Google Scholar]

- Maria Pinińska-Bereś. 2012. Maria Pinińska-Bereś. 2012. Imaginarium cielesności/Imaginarium of Corporeality [Exhibition Catalogue]. Edited by Anna Borowiec and Magdalena Piłakowska. Translated by Szymon Nowak. Sopot: Państwowa Galeria Sztuki. [Google Scholar]

- Markowska, Anna. 2019. Dlaczego Duchamp nie czesał się z przedziałkiem? Kraków: Universitas. [Google Scholar]

- McEvilley, Thomas. 2012. The Triumph of Anti-Art: Conceptual and Performance Art. in the Formation of Post-Modernism. New York: McPherson & Company. [Google Scholar]

- Moore, Henry. 1981. Uwagi o rzeźbie. In Postawy wobec sztuki najnowszej. Edited by Jacek Bukowski. Translated by Wiesław Juszczak. Warszawa: Wydawnictwa Szkolne i Pedagogiczne. [Google Scholar]

- Popiel, Magdalena. 2018. Świat artysty. Modernistyczne estetyki tworzenia. Kraków: Universitas. [Google Scholar]

- Roberts, John. 2007. The Intangibilities of Form: Skill and Deskilling in Art after the Readymade. London: Verso. [Google Scholar]

- Roberts, John. 2010. Art after Deskilling. Historical Materialism 18: 77–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rose, Gillian. 2010. Interpretacja materiałów wizualnych. Krytyczna metodologia badań nad wizualnością. Translated by Ewa Klekot. Warszawa: Wydawnictwa Naukowe PWN. [Google Scholar]

- Sienkiewicz, Marek. 2008. Odnajdywanie przestrzeni. Ph.D. thesis, Akademia Sztuk Pięknych im. Eugeniusza Gepperta we Wrocławiu, Wrocław, Poland. Written under the supervision of Professor Christos Mandzios [typescript]. [Google Scholar]

- Simmel, Georg. 2020. Essays on Art. and Aesthetics. Chicago and London: The University of Chicago Press. [Google Scholar]

- Singerman, Howard. 2009. The Intangibilities of Form: Skill and Deskilling in Art after the Readymade by John Roberts. Art Journal 1: 107–11. [Google Scholar]

- Wąs, Cezary. 2012a. Leon Podsiadły. Wrocław: Akademia Sztuk Pięknych we Wrocławiu im. Eugeniusza Gepperta. [Google Scholar]

- Wąs, Cezary. 2012b. Leon Podsiadły. Available online: https://www.academia.edu/2509501/Leon_Podsiad%C5%82y (accessed on 1 May 2020).

- Wojciechowski, Jan Stanisław. 1997. Nowocześni i ponowocześni. Wokół polskiej rzeźby lat 70. i 80. In Wokół polskiej rzeźby lat 70-tych i 80-tych XX wieku [Exhibition Catalogue]. Edited by Romuald K. Bochyński. Translated by Maria Olejniczak. Orońsko: Centrum Rzeźby Polskiej w Orońsku. [Google Scholar]

| 1 | Selected literature concerning deflation in contemporary art consists of publications that address this topic from a broad perspective (e.g., Roberts 2010, pp. 77–96; Roberts 2007; Danto 1997; Bourdieu 1995, p. 56) and publications that discuss the intentional reduction of artistry in the activity of pre-war avant-garde (Buchloch 2014, pp. 49–62; Lascault 2011, pp. 37–52; Markowska 2019). |

| 2 | According to contemporary research optics, Diogenes of Sinope is regarded as the patron saint of anti-art; see, for instance, McEvilley (2012) (in the chapter entitled “Diogenes of Sinope. Patron Saint of Performance and Conceptual Art”, pp. 9–12). |

| 3 | Leon Podsiadły was a versatile sculptor, drawing artist, and painter. From 1952–1958, he was a student at the State College of Fine Arts (PWSSP) in Wrocław. For many years (1970–2020), he was a professor at that college as well as Dean of the Faculty of Painting, Engravingm and Sculpture (1980–1983) and Head of the Department of Sculpture (1986–1989). Podsiadły co-founded the Wroclavian Group, consisting chiefly of artists from PWSSP. He also taught at the fine arts college École Nationale des Arts at Métiers in Conakry (Guinea) (1965–1970) and at the Institute of Art at Opole University (1993–2002). Podsiadły was the creator of sculptures for public spaces, of open-air and sepulchral sculptures, and of private spatial compositions. His best-known works include Monuments to the Victims from KL Gross-Rosen [Gross-Rosen Concentration Camp] (Wrocław, Wichrów, Piotrowice) in the 1960s, the Monument to the Combat Trail of the Polish Second Army in Trzebnica (1976), and the statue of Nicolaus Copernicus in Wrocław (1974–1977). He also created Odwołany lot [Canceled Flight], 1982, a sculpture inspired by the martial law period; he co-created the Pope’s altar in Wrocław’s Partynice (1983); co-designed (with Mieczysław Zdanowicz) the Monument of Freedom in Wrocław (1979). See (Wąs 2012a, pp. 120–22), and other publications that refer to Podsiadły’s work both individually and in general, among them (Sienkiewicz 2008, pp. 18–19; Makarewicz 2006, pp. 83–125; Makarewicz 1999, pp. 70–93; Wojciechowski 1997, pp. 5–16; Makarewicz 1986, pp. 61–82; Antkowiak 1985, pp. 115–17). Some publications (e.g., exhibition catalogues) that offer a more specific treatment of the artist’s work include (Leon Podsiadły 1977, 1985, 2006). |

| 4 | Modernism refers to the modern period (from the advent of the Enlightenment in the 18th century to the 1960s; prominent in art history from the 1860s to the 1960s/70s). This period sanctioned the autonomy of the rational human subject as cognitively governing the world of objects; it also emphasized the universality and systemic character of beliefs and the possibility of obtaining the truth. Trends in modernist art established the value of the creator’s individual expression, artistic autonomy, elitism, and experimentation. They promoted the idea of the masterpiece as distinguished by anti-mimeticism and the discovery of the novel formal quality as well as the mastery of execution and the unique processing of material. The work of art, produced in the immediate relationship between the artist and the artistic medium, often gravitated toward abstract (avant-garde) forms, preferably perfect in its marking of the separate world of the genius-artist. See, for example, (Dziamski 1996a, pp. 47–75; Gazda 1996, pp. 21–32). |

| 5 | Postmodernism refers to the period that succeeded and revised modernism, and thus to the new tendencies in art, contemporary culture, philosophy, and social life. The term also applies to postmodern artistic trends that rejected the cult of the uniqueness of the creator and creative autonomy in favor of popular art and the patterns of mass culture. The acceptance of the commercial nature of artistic activity has been accompanied by imitation, reproduction, and repetition, which generate unoriginality and eclectic, stylistic pluralism including hybrid forms that distort established conventions. In line with an attitude of inclusiveness toward alien, marginal, and ambiguous qualities, postmodern artists have used mundane materials and industrial products available to “common” people. Moreover, they have questioned traditional definitions of aesthetics, masterfulness, and mastery, and emphasized the potential that lies within the deconstruction of paradigms and methodological anarchy. See, among other publications, (Dziamski 1996b, pp. 389–402). |

| 6 | The abject according to Julia Kristeva refers to what, in physiological terms, could be thought of as a waste-product without a future, useless and revolting. Postmodern art exposes the “bottomless ‘primacy’” and obscene immediacy of the abject (Kristeva 1982, p. 18; qtd Foster 1996, p. 156). A rejection of the abject is transgressive and disruptive of authorial subjectivity, even though, in principle, the rejection of the abject is the very basis for subjectivity (Foster 1996, pp. 153–56). |

| 7 | Interestingly, John Roberts, when analyzing Duchamp’s ready made, confirms the idea that the concept of deskilling consists of linking the artistic object to media of questioned aesthetic value (Roberts 2010, pp. 77–96). On one hand, in accordance with its anti-elitist stance, this link has opened a context for the production and exposure of the artifact, which allowed for freedom in creating and showing the work as well as in its everyday life. On the other hand, the link has initiated the widening of artistic skills and the negotiating of the boundaries of sanctioned crafts including the various modes of penetration of spatial form (sculpture), which have dethroned painting’s dominating position in modernism. |

| 8 | At this point, the text refers to the semiotic definition of a sign proposed by Ferdinand de Saussure as a specific form that represents something else. A sign understood in this way consists of two parts: (1) signifiant (signifier), in other words, the form the sign has taken and (2) signifié (signified), that is, the meaning of the sign (D’Alleva 2005, pp. 28–34). |

| 9 | See (Roberts 2007; Singerman 2009, pp. 107–11). Contemporary strategies, in other words, copying, repetitions, appropriation, simulacra (e.g., according to Jean Baudrillard, copies devoid of the original and reference to a real semiotic basis) are, according to these scholars, regarded as necessary features of the current discourse about art, based on a (re)interpretation of authorship and art’s semiosis, among other ideas. |

| 10 | It is worth recalling that Rodin’s struggle with difficult sculpting matter brings to mind (among other concerns) the modern cult of heavy noble matter, the mastery over which makes possible creative freedom. See Georg Simmel’s essays “Auguste Rodin: Part I”, “Auguste Rodin: Part II”, “Auguste Rodin: Part III” (Simmel 2020, chapter 7 Sculpture, pp. 302–19). |

| 11 | An attitude propagated, among other artists, by Henry Moore. |

| 12 | A movement known in Poland as turpizm, centered around the representation of ugly, macabre, revolting, and distorted objects in art. |

| 13 | This sculpture is located in Góra Świętej Anny (Saint Anne Mountain) in southwestern Poland, about 120 km from Wrocław. |

| 14 | Apart from the three studios mentioned here, Makarewicz also names the school of the painter and ceramist Mieczysław Pawełko, active after the expulsion from the College of Antoni Mehl (Makarewicz 2006, pp. 84–85). |

| 15 | In socialist art, these groups would have been drawn from the working class (i.e., miners, industrial workers, farmers, etc.). |

| 16 | Bolesławiec is a city in southwest Poland internationally renowned for the production of ceramics. |

| 17 | The source texts estimate the possible window of creation as between these two dates (Wąs 2012b, p. 8; Wąs 2012a, p. 41). |