The Horse and the Lion in Achaemenid Persia: Representations of a Duality

Abstract

:1. The Horse

There is nothing mortal that accomplishes a course more swiftly than do these messengers, by the Persians’ skilful contrivance. It is said that as many days as there are in the whole journey, so many are the men and horses that stand along the road, each horse and man at the interval of a day’s journey. These are stopped neither by snow nor rain nor heat nor darkness from accomplishing their appointed course with all speed. The first rider delivers his charge to the second, the second to the third, and thence it passes on from hand to hand, even as in the Greek torch-bearers’ race in honour of Hephaestus. This riding-course is called angarēion by the Persians.7

He [Cyrus] experimented to find out how great a distance a horse could cover in a day when ridden hard but so as not to break down, and then he erected post-stations at just such distances and equipped them with horses and men to take care of them; at each one of the stations he had the proper official appointed to receive the letters that were delivered and to forward them on, to take in the exhausted horses and riders and send on fresh ones. They say, moreover, that sometimes this express does not stop all night, but the night-messengers succeed the day-messengers in relays […] it is at all events undeniable that this is the fastest overland travelling on earth.12

As a horseman I am a good horseman (asabâra uvâsabâra amiy). As a bowman, I am a good bowman both afoot and on horseback (asabâra). As a spearman I am a good spearman both afoot and on horseback (asabâra).49

[Cyrus was] the most devoted to horses (φιλιππότατος) and the most skilful in managing horses […] when he was of suitable age, he was the fondest of hunting and, more than that, the fondest of incurring danger in his pursuit of wild animals.50

when he saw a deer spring out from under cover, he forgot everything that he had heard and gave chase… somehow his horse in taking a leap fell upon its knees and almost threw him over its head. However, Cyrus managed, with some difficulty, to keep his seat, and his horse got up.54

one of the horses that were being led in the procession and [gives] orders to one of the macebearers to have it led away for him wherever he should direct. And to those who saw it, it seemed to be a mark of great honour, and as a consequence of that event many more people paid court to that man.92

Within the enclosure, and lying on the approach to the tomb itself, was a small building put up for the Magians, who were guardians of Cyrus’ tomb, from as long ago as Cambyses, son of Cyrus, receiving this guardianship from father to son. To them was given from the king a sheep a day, an allowance of meal and wine and a horse each month, to sacrifice to Cyrus.97

2. The Lion

In times past, they used to go out hunting so often that the hunts afforded sufficient exercise for both men and horses. However, since Artaxerxes and his court became the victims of wine, they have neither gone out themselves in the old way nor taken the others out hunting.179

3. An Afterthought and Conclusions: The Horse, the Lion, and the Persians’ Two Modes of Life

Soft lands breed soft men; wondrous fruits of the earth and valiant warriors grow not from the same soil.180

This is your case, men of Persia: obey me and you shall have these good things and ten thousand others besides with no toil and slavery; but if you will not obey me, you will have labours unnumbered, like the toil of yesterday. Now, therefore, do as I bid you, and win your freedom […] All this is true; wherefore now revolt from Astyages with all speed.181

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| BM | The British Museum, London |

| EHAM | Erebuni Historical and Archaeological Museum-Reserve, Yerevan |

| IAM | Istanbul Archaeology Museums (İstanbul Arkeoloji Müzeleri) |

| INM | Iran National Museum (Mūze-ye Irān-e Bāstān), Tehran |

| IrMus | Iraq Museum, Bagdad |

| JPGM | J. Paul Getty Museum and Villa, Los Angeles |

| Louvre | Musée du Louvre, Paris |

| MMA | The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York |

| OIM | Oriental Institute Museum, Chicago |

| PFS | Persepolis Fortification Sealings |

| 1 | Diod. 15.10.3: κατὰ γάρ τινα κυνηγίαν ἐφ’ ἅρματος ὀχουμένου τοῦ βασιλέως δύο λέοντας ἐπ’ αὐτὸν ὁρμῆσαι, καὶ τῶν μὲν ἵππων τῶν ἐν τῷ τεθρίππῳ δύο διασπάσαι, τὴν δ’ ὁρμὴν ἐπ’ αὐτὸν ποιεῖσθαι τὸν βασιλέα· καθ’ ὃν δὴ καιρὸν ἐπιφανέντα τὸν Τιρίβαζον τοὺς μὲν λέοντας ἀποκτεῖναι, τὸν δὲ βασιλέα ἐκ τῶν κινδύνων ἐξελέσθαι; trans. Oldfather (LCL series); (Almagor 2018, pp. 218–19). |

| 2 | Curt. Ruf. 8.1.14–16; cf. Hdt. 3.32.1. |

| 3 | For reasons of space, the discussion is not intended to be comprehensive. |

| 4 | See (Littauer and Crouwel 1979, pp. 24–26; Kelekna 2009, pp. 93–94; Gheorghiu 1993). The theory that horse riding was as early as the fourth millennium has been contested and debated; for which, see (Zarins 1978, pp. 4–11; Anthony et al. 1991; Anthony and Brown 2000; Levine 1999; Drews 2004, pp. 12–26: “occasional riding”). The practice came from the outside into Iran, where the native equid was the Equus hemionus onager; for which, see (Littauer and Crouwel 1979, pp. 23–24; Kelekna 2009, pp. 24, 43; Potts 2014, p. 49). Note the manner in which the hybrid hemionos is used to symbolize Cyrus the Great in Herodotus (1.55, 1.91; cf. 3.151); see (Asheri et al. 2007, pp. 115, 157). |

| 5 | “Nomadism” designates the life of seasonal migratory herders, periodically moving between grazing territories and pasture lands; for which, Arist. Polit. 1.1256a; Hippocr. De aer. 18; see (Potts 2014, pp. 2–3; Almagor 2014, p. 4). |

| 6 | A text from Mari: see (Durand 1998, pp. 2.484–2.488, text 732; Drews 2004, p. 42). |

| 7 | Hdt 8.98: τούτων δὲ τῶν ἀγγέλων ἐστὶ οὐδὲν ὅ τι θᾶσσον παραγίνεται θνητὸν ἐόν· οὕτω τοῖσι Πέρσῃσι ἐξεύρηται τοῦτο. λέγουσι γὰρ ὡς ὁσέων ἂν ἡμερέων ᾖ ἡ πᾶσα ὁδός, τοσοῦτοι ἵπποι τε καὶ ἄνδρες διεστᾶσι κατὰ ἡμερησίην ὁδὸν ἑκάστην ἵππος τε καὶ ἀνὴρ τεταγμένος· τοὺς οὔτε νιφετός, οὐκ ὄμβρος, οὐ καῦμα, οὐ νὺξ ἔργει μὴ οὐ κατανύσαι τὸν προκείμενον αὐτῷ δρόμον τὴν ταχίστην. ὁ μὲν δὴ πρῶτος δραμὼν παραδιδοῖ τὰ ἐντεταλμένα τῷ δευτέρῳ, ὁ δὲ δεύτερος τῷ τρίτῳ· τὸ δὲ ἐνθεῦτεν ἤδη κατ᾽ ἄλλον καὶ ἄλλον διεξέρχεται παραδιδόμενα, κατά περ ἐν Ἕλλησι ἡ λαμπαδηφορίη τὴν τῷ Ἡφαίστῳ ἐπιτελέουσι. τῶν ἵππων καλέουσι Πέρσαι ἀγγαρήιον. Cf. Hdt. 3.126.2: ἀγγελιηφόρος (v.l. ἀγγαρήιος); trans. Godley (LCL series). |

| 8 | See Hesych. s.v. A 374b, Suda s.v. α 164–65. The origin of the word is most probably the Akkadian word agru(m) (LU.ḪUN.GA; LU.A.GAR, pl. Old Babylonian agrū, New Babylonian agrūtu), “a hired man, hireling”, in relation with igru(m), “hire, rent, wage”, later specifically understood as a messenger and by derivation, the Aramaic iggartā (Almagor 2018, p. 153). |

| 9 | Cf. Hdt. 7.43: Xerxes sacrifices to Athena of Ilium in the “citadel of Priam” (Hall 1989, pp. 21–25). |

| 10 | See (Sparkes 1971). |

| 11 | See (Almagor 2021). |

| 12 | Xen. Cyr. 8.6.17–18: σκεψάμενος γὰρ πόσην ἂν ὁδὸν ἵππος καθανύτοι τῆς ἡμέρας ἐλαυνόμενος ὥστε διαρκεῖν, ἐποιήσατο ἱππῶνας τοσοῦτον διαλείποντας καὶ ἵππους ἐν αὐτοῖς κατέστησε καὶ τοὺς ἐπιμελομένους τούτων, καὶ ἄνδρα ἐφ᾽ ἑκάστῳ τῶν τόπων ἔταξε τὸν ἐπιτήδειον παραδέχεσθαι τὰ φερόμενα γράμματα καὶ παραδιδόναι καὶ παραλαμβάνειν τοὺς ἀπειρηκότας ἵππους καὶ ἀνθρώπους καὶ ἄλλους πέμπειν νεαλεῖς. ἔστι δ᾽ ὅτε οὐδὲ τὰς νύκτας φασὶν ἵστασθαι ταύτην τὴν πορείαν, ἀλλὰ τῷ ἡμερινῷ ἀγγέλῳ τὸν νυκτερινὸν διαδέχεσθαι. […] ὅτι γε τῶν ἀνθρωπίνων πεζῇ πορειῶν αὕτη ταχίστη […]. Xenophon’s description may in fact be an elaboration of Herodotus (~”they say”, φασί); trans. Miller (LCL series). See (Almagor 2021). |

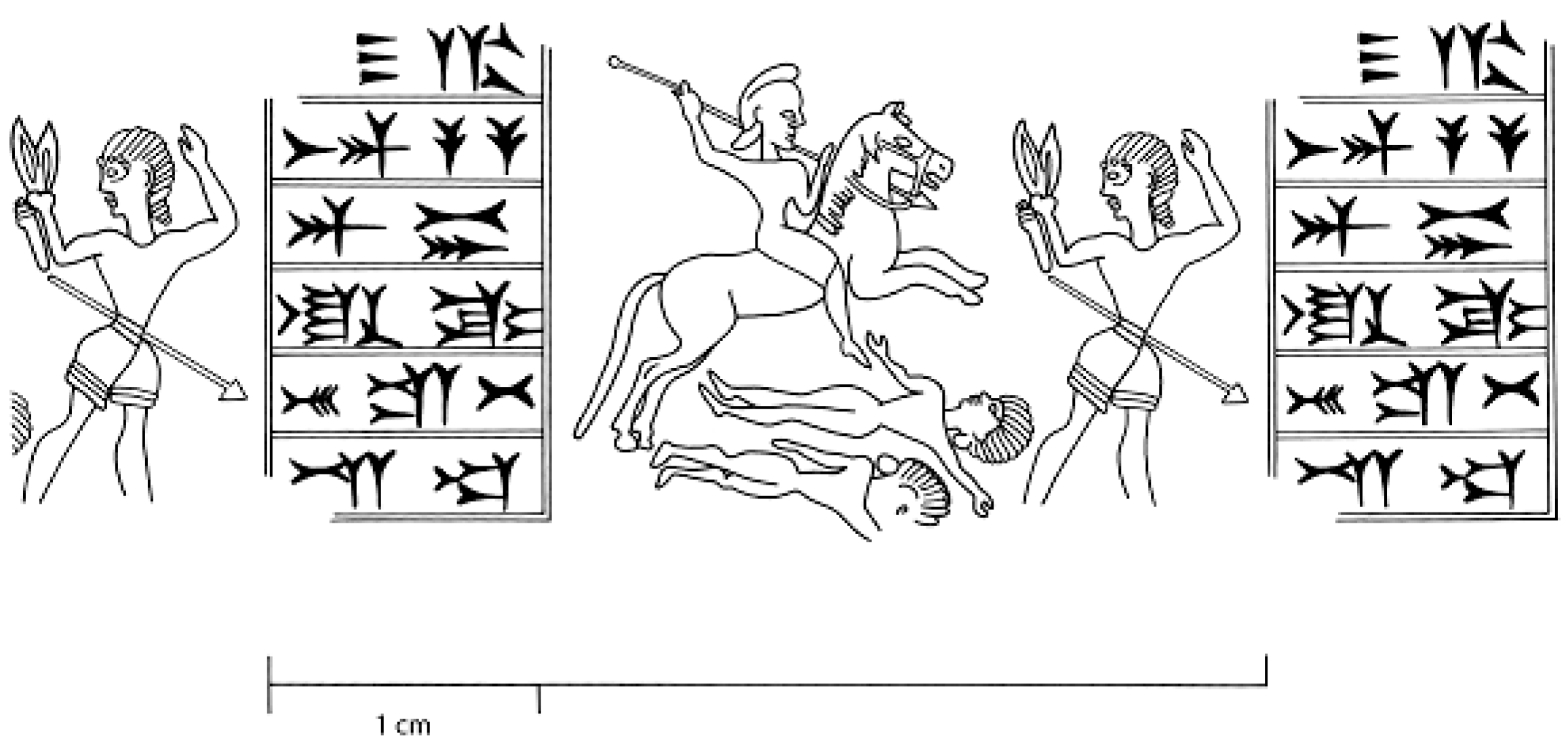

| 13 | |

| 14 | See (Kelekna 2009, p. 3). |

| 15 | Cf. Plat. Apol. 20a, 25b, Rep. 3.413d, Leg. 2.666e; cf. Gorg. 516ab; Xen. Mem. 4.1.3. |

| 16 | On the Achaemenid cavalry, see (Tuplin 2010). |

| 17 | Xen. Cyr. 6.2.16, 7.1.3, 8, 19, 26, 28, 31, 37, 39–40, 46, also 6.2.18, 7.1.22, 27, 48–49; cf. Hdt. 1.80; Polyaen. 7.6.6. |

| 18 | Hdt. 6.29. |

| 19 | Hdt. 9.20, 22–23, 32 and 71. |

| 20 | Xen. Anab. 1.7.11, 1.8.5–1.8.6, 9, 21, 24–25, 1.9.31. |

| 21 | Diod. 17.19–21; Arr. Anab. 1.14.4, 1.15.2 and 4. |

| 22 | Diod. 17.33.6, 34.3; Arr. Anab. 2.8.5, 10, 9.1, 11.2–11.3 and 7–8. |

| 23 | Diod. 17.58.2–4, 59.2–8, 60.4–6, 61.3; Arr. Anab. 3.11.3–8, 3.14.1–15.2. Other sporadic mentions of Persian cavalry units include Hdt. 8.113; Xen. Anab. 3.4.35, 4.3.3, 12, 17, 22–23, 6.5.7, Hell. 3.2.15, 3.4.13–14, 22–24, 4.1.17, 4.8.19, Cyr. 6.2.4, 7; Polyaen. 7.14.2–3, 7.21.6–7, 7.28.2, also 5.16.2. |

| 24 | Hdt. 6.112–13. |

| 25 | |

| 26 | See (Potts 2014, p. 89). |

| 27 | See (Frye 1984, p. 40): “[…] the movement of peoples beginning about 1000 BC was the result, in large measure, of a great expansion in the use of the horse […]”. See (Linder 1981; Potts 2014, p. 119): “It seems certain that the horse made some of the groups […] more mobile, though the evidence pertaining to non-military matters remains sparse”. According to one view, nomadic pastoralism was predominant in prehistoric and Bronze Age southwestern and south-central Iran (Alizadeh 2008). Yet, cf. the reasonable rejection of this opinion by (Potts 2014, pp. 8–46). |

| 28 | Daoi: Arr. Anab. 3.11.37, Curt. Ruf. 4.12.5; Mardians: Arr. Anab. 3.11.5, 3.13.1; Dropicans (i.e., Derbicans): Curt. Ruf. 3.2.7; Sagartians: Hdt. 7.85. The evidence is assembled in (Potts 2014, pp. 88–119). |

| 29 | Cf. Yasht 13.88-89. Cf. Yasna 50.6 (raiθī-, “charioteer” [i.e., of my tongue]). See (Benveniste 1932, p. 133; Kellens 1974, pp. 231–32). |

| 30 | See (Gershevitch 1959, pp. 69–70). |

| 31 | See Yasna 2.5, 6.4, 57.27-8, 62.8, 65.12, 70.6; Yasht 2.9, 5.11, 13, 79, 8.38, 10.52, 66, 76, 125, 136, 17.1, 4, 12, 21, 23, 19.51–2. |

| 32 | See Yasna 11.2, 40.3, 65.4; Yasht, 5.4, 11, 101, 10.3, 11, 20, 47, 13.7, 15.12, 19.76. |

| 33 | |

| 34 | See Yasna 8.19, 44.18, 50.7 (Ahura Mazda); Yasht 5.86, 98, 130, 9.7, 12, 16, 20, 24, 28, 10.3, 17.12, 18.5, 19.67. See (Tuplin 2010, p. 129, n. 115). |

| 35 | DPd, 8 (trans. Kent); cf. DSf.11; DSp.3, DZc.4: “possessed of good charioteers, of good horses”. It is followed in the unauthentic AmH, 6–9 (Ariaramnes’ inscription from Ecbatana/Hamadan): “This country Persia which I hold, which is possessed of good horses, of good men”. |

| 36 | Hdt. 1.188.1–2, 5.49.7, 5.52.6; Ctesias, FGrH 688 F 37; Tibullus, 3.7.140; Strabo 1.3.1, 15.3.4; Curt. Ruf. 5.2.9; Paus. 10.31.7; Nicander, Theriaca 890; Ath. 2.45a–b; Ael. VH 12.40; Ausonius, Ordo Urbium Nobilium 20.29; Nonnus Dionys. 23.277; Suda, s.v. Χοάσπειον ὕδωρ, χ 366 Adler (Weissbach 1899; Tuplin 2010, p. 128). Plut. Art. 12.6 with (Almagor 2018, pp. 117–18). |

| 37 | DSs, 5 (trans. Kent). The name of Darius’ own father is composed of a horse stem: Hystaspes (OPers. Vištāspa): DB 1.2–4, 2.93–4, 97, DNa.12–13, DSa.2, Hdt. 1.183, 209–11, an Avestan name: Yasna 12.7, 23.2, 26.4, 28.7, 46.14, 51.16, 53.2. |

| 38 | See (Drews 2004, p. 116). |

| 39 | See (Briant 2002, pp. 14, 19–20). Xen. Cyr. 4.3.4–23, esp. 10–20 on the introduction of horse riding among the Persians as part of the new establishment of the cavalry by Cyrus the Great. Cf. Cyr. 8.6.10. |

| 40 | Anshan, the name of western Elamite region, was at one point separated from Elam and identified later within the Fars/Parsa (Persia) province, homeland of the Achaemenids. See (Hansman 1972, pp. 107, 108 + n. 60; Potts 2005). |

| 41 | PFS *93; See (Garrison and Root 1996, pp. 6–7, figure 2a; Garrison 2011). The cylinder seal is preserved in impressions on a series of clay tablets from the Persepolis Fortification archive. |

| 42 | Cf. the descriptions of a land in Fars/Persia as suitable for horses: Arr. Ind. 40.3, cf. Diod. 19.21.2–3; Strab. 15.3.1. |

| 43 | |

| 44 | |

| 45 | Hdt. 3.106, 7.40; cf. Arist. HA 9.632; Diod. 17.110.6; Strab. 11.13.7, 11.14.9; Arr. Anab. 7.13.1; Suda, s.v. Νίσαιον, ν 425 Adler. On the plain, see (Hanslik 1936, p. 712; Ghirshman 1954, p. 94; Herzfeld 1968, pp. 15–16; Gabrielli 2006, pp. 26–27). |

| 46 | Polyb. 10.27.1: “Media is the most notable principality in Asia, both in the extent of its territory and the number and excellence of the men and also of the horses it produces” (trans. Paton, LCL series), also 5.44.1. |

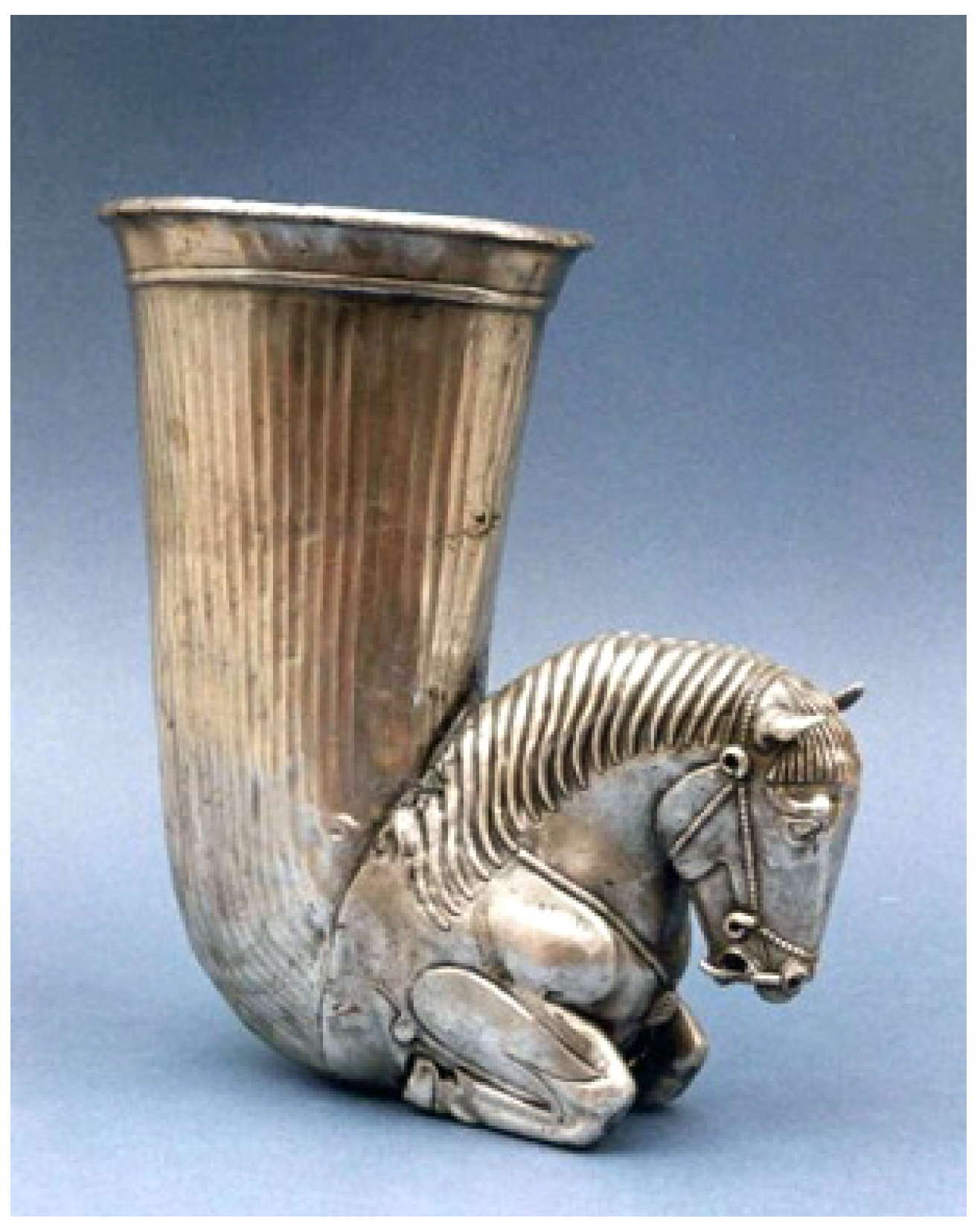

| 47 | See, however (Potts 2014, pp. 72–73). |

| 48 | See (Radner 2003). |

| 49 | DNb, 41–44 (Kent trans.); for this association between kingdom and a horse, also see Xen. Cyr. 8.3.35–50. |

| 50 | Xen. Anab. 1.9.5–6, trans. Brownson (LCL series); also Anab. 1.2.7: Cyrus partook in hunting “whenever he wished to give himself and his horses exercise”. Cf. 1.8.3, 15. The motif is found also in Cyrus’ letter to the Spartans (Plut. Art. 6.4), sent to solicit their assistance in his bid for the throne against his brother Artaxerxes II; among the monarchic traits which Cyrus finds lacking in his brother is the ability to keep a place on his horse during the hunt or on his throne in trouble (ἐκεῖνον δ’ ὑπὸ δειλίας καὶ μαλακίας ἐν μὲν τοῖς κυνηγεσίοις μηδ’ ἐφ’ ἵππου ἐν δὲ τοῖς κινδύνοις μηδ’ ἐπὶ τοῦ θρόνου καθῆσθαι). The recurrence of the theme is regardless of the question whether Plutarch invented this detail, inspired by Xenophon (Mossman 2010, p. 151) or whether, conversely, Plutarch took it from an earlier author (most probably Ctesias); see (Almagor 2018, pp. 110–12). |

| 51 | Cf. Ctesias FGrH 688 F 13.17. The later author Ptolemaeus Hephaistion (Photios, Bibl. cod. 190, 148b Bekker) produced another horse-related story concerning Darius, namely, that he was exposed by his mother and was fed on mares-milk by a horse guardian, Spargapises; for the latter name, see Hdt. 1.211. |

| 52 | ἐν ἄγρῃ θηρῶν ἀποθρώσκοντα ἀπ᾽ ἵππου στραφῆναι τὸν πόδα. καί κως ἰσχυροτέρως ἐστράφη. |

| 53 | παιδεύουσι δὲ τοὺς παῖδας… τρία μοῦνα, ἰχνεύειν καὶ τοξεύειν καὶ ἀληθίζεσθαι. See (Asheri et al. 2007, p. 170) for a suggestion that this triad may arise from a miscomprehension of royal formulae of glorification (as horsemen and archers). Cf. Strabo (15.3.18) who adds (from Polycleitus of Larissa?) the use of spears as a component in the Persian education. |

| 54 | Xen. Cyr. 1.4.8, trans. Miller (LCL series); for his age, see 1.4.5. |

| 55 | Diog. Laert. 3.37; cf. Apul. Apol. 25; Amm. Marc. 23.6.32; see (Schleiermacher 1836, pp. 328–36; Shorey 1933, p. 415; Smith 2004). Cf. the surveys in (Denyer 2001, pp. 14–26; Gribble 1999, pp. 260–61; Archie 2015, pp. 36–44). |

| 56 | Hdt. 1.27, 79–80 claims that the Lydian cavalry was excellent (Tuplin 2010, p. 172). |

| 57 | Ael. Nat. Anim. 16.25 (ὡς μή ποτε ἐν τῷ πολέμῳ δείσωσι … τὸν τῶν ξιφῶν πρὸς τὰς ἀσπίδας δοῦπον); cf. Xen. Anab. 1.8.18. |

| 58 | The horses were first used (before the second millennium bce) for drawing chariots of war or wagons and for transport as paired draught animals. See (Littauer and Crouwel 1979, pp. 13, 22–23, 28–31, 33, 41–43, 56–59, 65–68, 82–86; Drews 2004, pp. 4, 23–25, 38, 40–48, 53, 55; Kelekna 2009, pp. 45–52, 73–76, 95–99). Evidence for riding, both figured and textual, substantially increases from the ninth century bce, especially in Assyria (Littauer and Crouwel 1979, pp. 134–39. See (Frye 1984, p. 39): “true nomads could hardly exist without the use of horses primarily for riding, and this suggests that nomadism is a relatively late and sophisticated development of a pastoralism based on the use of wagons to follow the herds” (Downs 1961). |

| 59 | Cf. Deinon ap. Ath. 12.514a–b: “Whenever the king dismounts from his chariot, he does not leap down, nor is he supported by hands, but a golden stool is always put down for him, and treading on it he descends”. Cf. Heracleides ap. Ath. 12.514c: “when [the king] came to the end of the courtyard, he mounted a chariot, but sometimes a horse; he was never seen outside the palace on foot”. |

| 60 | See especially Hdt. 7.41, cf. 7.83. Cf. Aristoph. Acharn. 69–70; Xen. Hell. 3.1.13, Cyr. 3.1.40, 6.4.11; cf. Aesch. Pers. 1000–1; see also (Hall 1989, pp. 95–96). |

| 61 | |

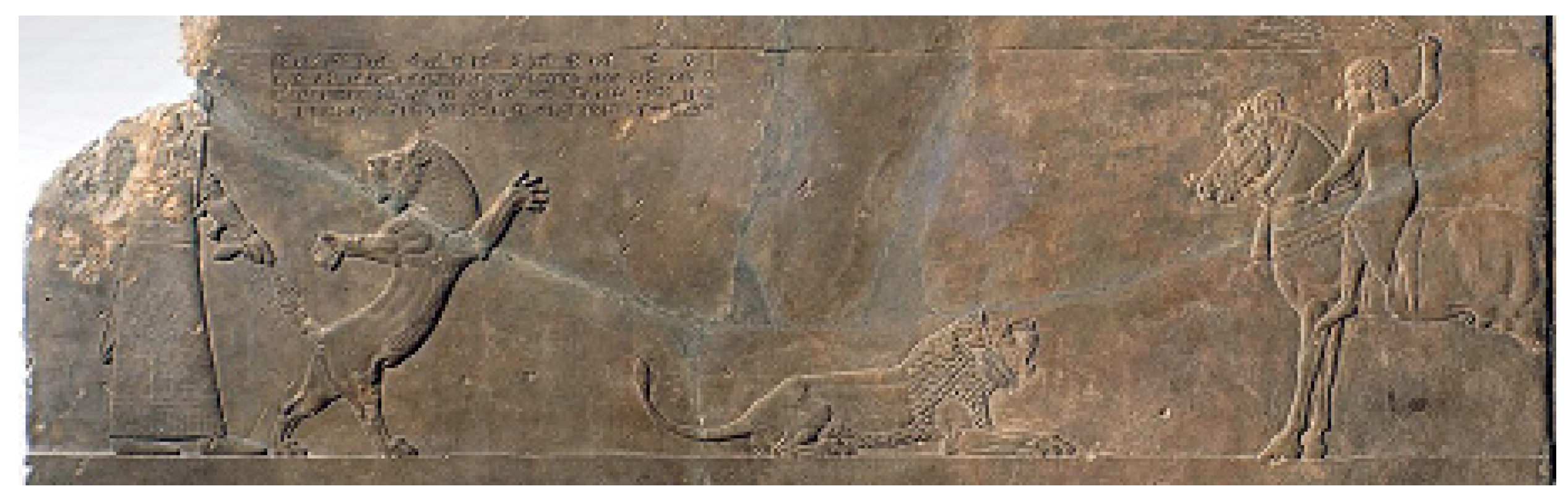

| 62 | BM inv. no. 124534 (Grayson 1991, no. 0.101.23.29). |

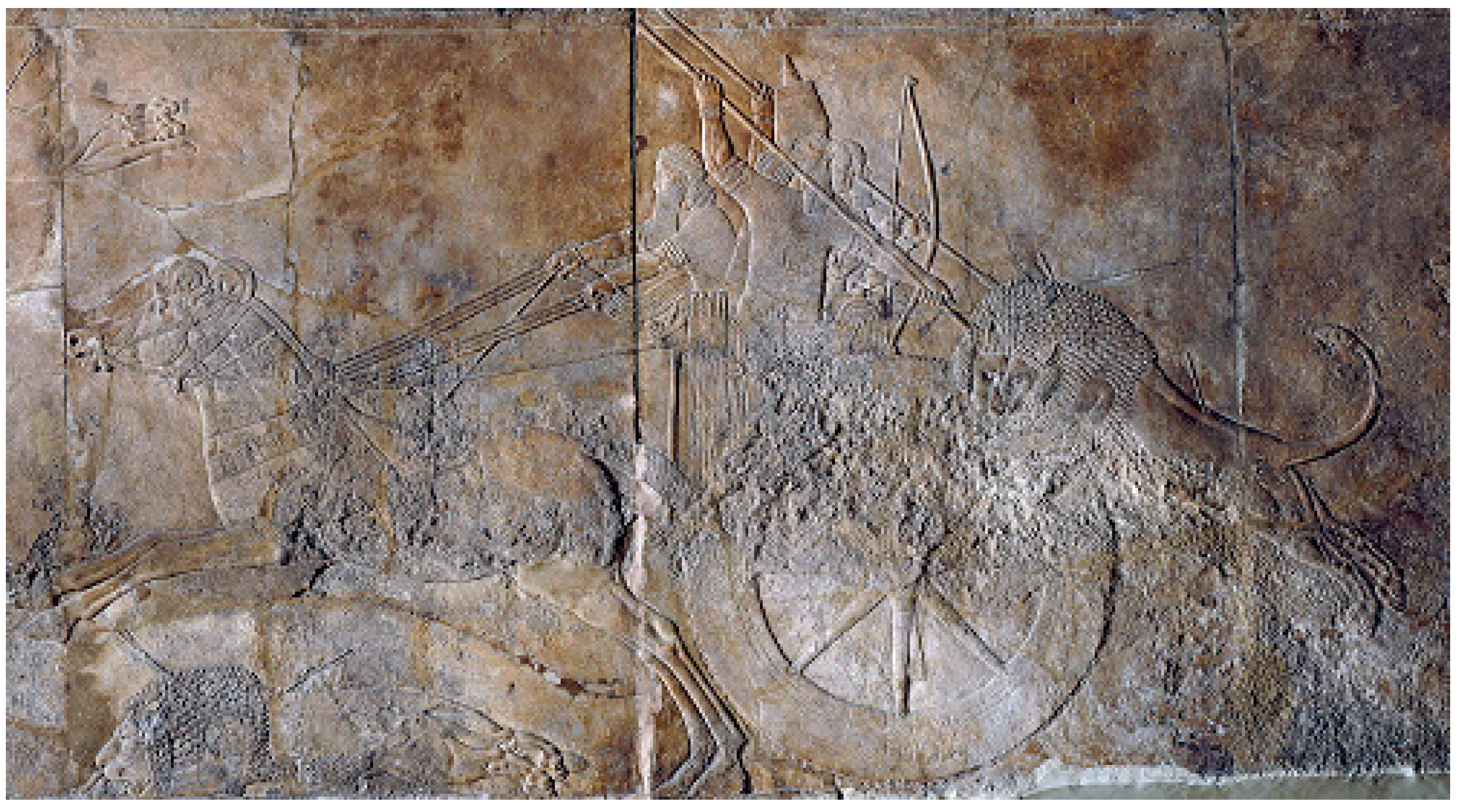

| 63 | BM inv. nos. 124850–51 and 54 (reg. no. 1856,0909.15); cf. BM inv. no. 124858 (Room C, Panel 5; preparation of chariot); see (Barnett 1976, p. 38, pl. 11; Weissert 1997, p. 340) (who even shows the existence of a topos of “Lion Hunt by Chariot (in the Plain)”). |

| 64 | BM inv. no. 89132 (reg. no. 1835,0630.1); see (Frankfort 1939, p. 221, pl. 37d; Curtis and Tallis 2005, no. 398). |

| 65 | See (Stronach 2009, p. 233, n. 35): “prolonged Achaemenid excavations at the site have so far failed to produce additional evidence for the existence of equestrian royal figures”. See (Tuplin 2010, pp. 104–5). This is grounded in an ideological difference between the Assyrian and the Persian images of power. |

| 66 | Ctesias relates (FGrH 688 F 14.38) that after the suppression of the revolt of Inarus the Egyptian Sarsamas (in all probability Arsames) was appointed to be the satrap of Egypt. For the date of the rebellion’s suppression see (Kahn 2008). The last dated letter in his correspondence is from 407 bce. See (Allen et al. 2014) (available online: http://blogs.bodleian.ox.ac.uk/wp-content/uploads/sites/116/2013/10/Vol-2-intro-25.1.14.pdf, accessed on 9 May 2021). A commentary is available as volume 3. |

| 67 | See (Root 1979, pp. 129–30; 2002, p. 207). |

| 68 | DB 4.71, 73, 77, 90; Elamite version DB El. 3.85: battikarum; cf. DNa.41. |

| 69 | As proposed by (Boardman 2000, pp. 134, 165, 243, n. 28). |

| 70 | Bodleian Library Oxford, Pell Aram. I–XV. |

| 71 | See (Stronach 2009, p. 230): “it is probably legitimate to conclude that Arshama was not in the habit of commissioning equestrian statues. Moreover, any specific bent of this kind, even on the part of a high-born Persian, would probably have attracted unfavorable royal notice”. For a discussion on this letter, see (Driver 1965, pp. 32, 71–74; Tuplin 2014, pp. 100–7). The small iconography had other ways of circulating and was visible to a different public. |

| 72 | See (Herzfeld 1929, p. 11): “ein prachtvoller Pferdekopf”; see (Stronach 1978, pp. 57, 61–62, 73–74, pl. 33; Root 2002, p. 206). |

| 73 | As (Kawami 1986, p. 266), has shown convincingly, the fragment may belong to a sculpture of a goat and not to a horse. |

| 74 | One may point at an interesting opposite parallel: in reality, the ancient Israelites had war and chariot horses (cf. 2 Samuel 8: 3–4, 1 Kings 10: 28–29, 1 Chronicles 18: 3–4); this did not prevent them from still maintaining the prohibition, from the time before they wielded power, not to hold nor to breed horses (Deut. 17:16); see (Kelekna 2009, pp. 99–100). |

| 75 | See (Moorey 1985, p. 34): “thus, the taste for metal vessels of this form may be ultimately Iranian, as some of the favoured animals might indicate”. |

| 76 | MMA acc. no. HAS 60-881; see (Dyson 1961, p. 537, fig. 10; Muscarella 1988, p. 24). |

| 77 | Respectively, INM inv. nos. 6700 and 8485; see (Curtis and Tallis 2005, p. 227, nos. 410, 411). |

| 78 | MMA acc. no. 47.100.87; for the provenance, see (Muscarella 1980, p. 30; Simpson et al. 2010, p. 434). |

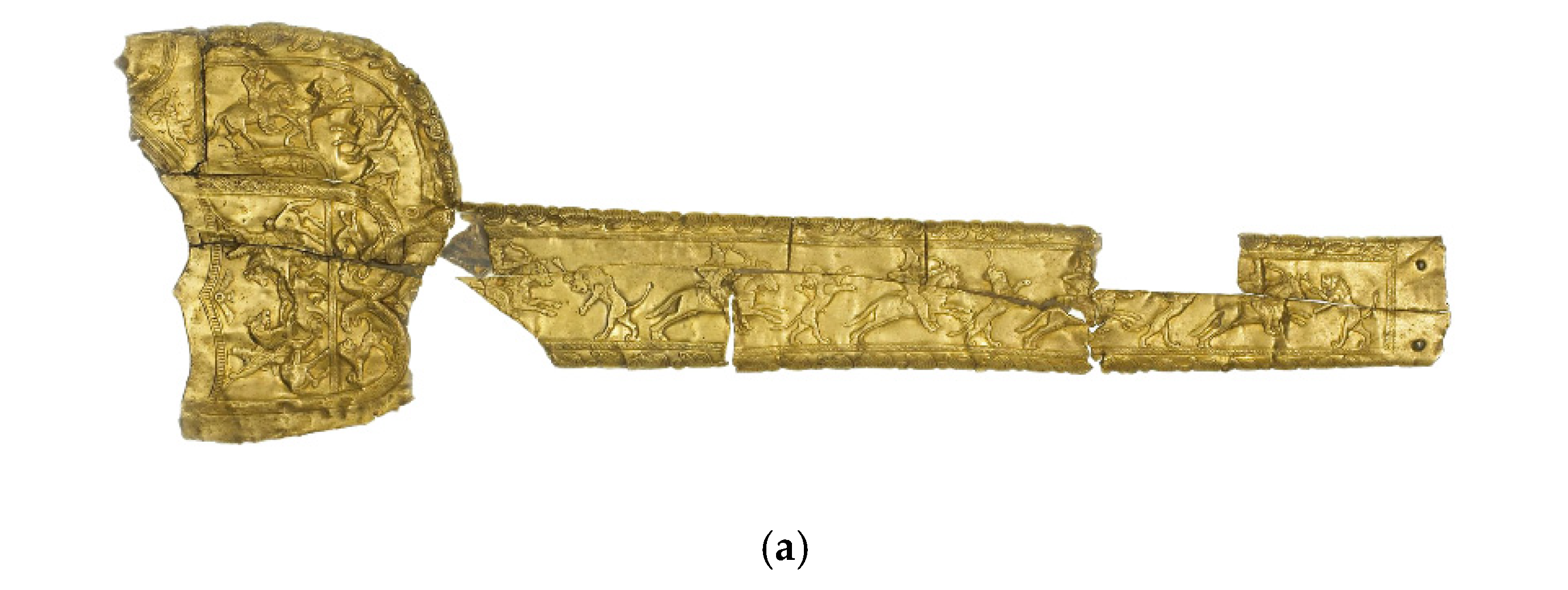

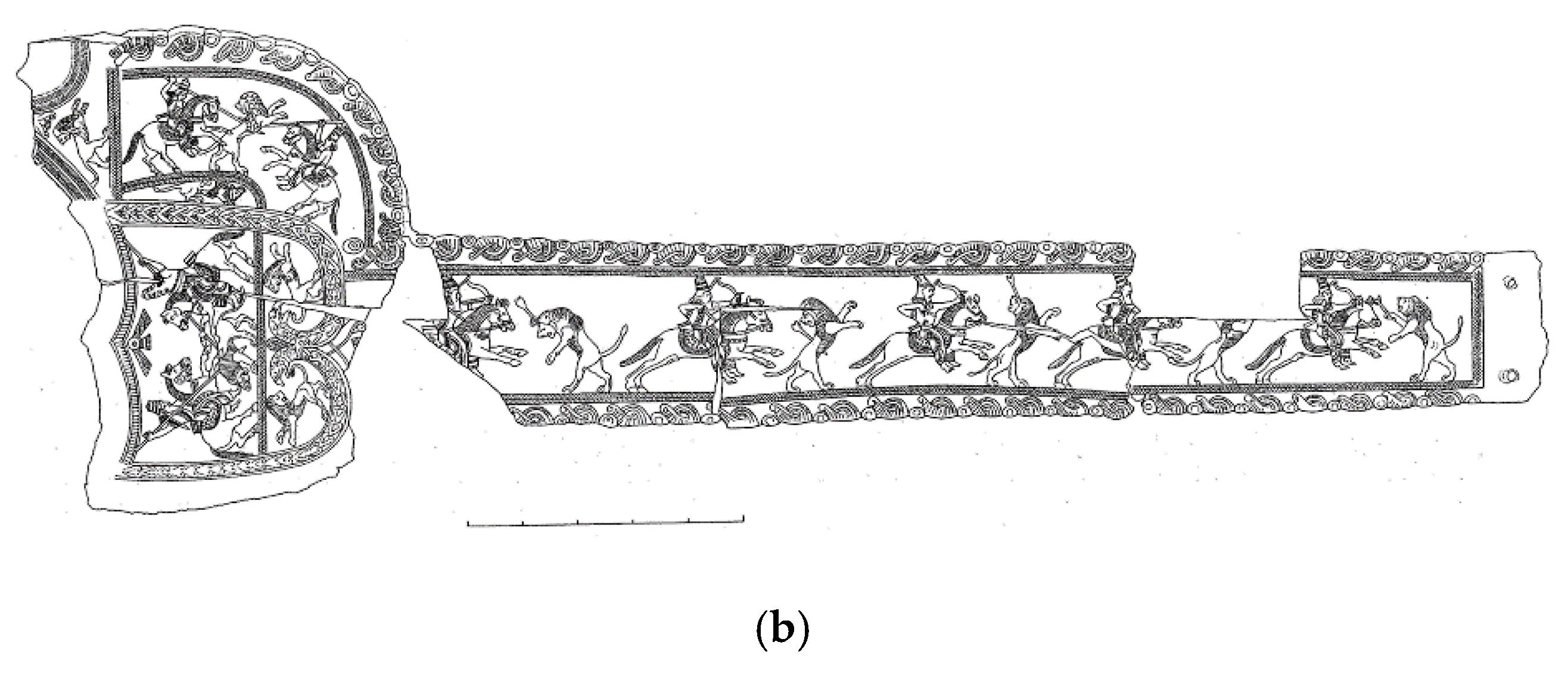

| 79 | EHAM inv. no. 19; see (Treister 2015, pp. 27–39). |

| 80 | EHAM inv. no. 20; see (Stronach 2009, pp. 226, 230, fig. 11), who rightly dismisses the assertion of (Farkas 1974, p. 76), that there was no Persian horse and rider motif “until Greek artists created it”; see (Treister 2015, pp. 39–65, 95–99). |

| 81 | |

| 82 | Orontes, satrap of Armenia after 401 bce? This is speculative, as admitted by (Treister 2015, pp. 61, n. 137 and 64; Stronach 2009, p. 226): “a person of rank”. |

| 83 | See (Kelekna 2009, p. 78): “metal items were not always strictly utilitarian. Designed to celebrate the nomadic lifestyle, many horse and chariot trappings and belt accessories […] were now rendered in bronze, silver, and gold”. |

| 84 | Hdt. 7.196; Xen. Cyr. 8.3.25, Eq. 8.6; Strab. 11.13.7. |

| 85 | In the first seal impression, there are two mounted horsemen, in the second, one. Respectively, seal 18: (Schmidt 1957, p. 25, pl. 6, PT4 976, PT4 805) and seal 34 (Schmidt 1957, p. 31, pl. 10, PT6 179, PT6 40; Root 2002, p. 207). |

| 86 | BM inv. no. 117760 (reg. no. 1890,0308.5); see (Curtis and Tallis 2005, p. 226, no. 409). |

| 87 | See (Dalton 1964, p. xvi; Curtis and Tallis 2005, pp. 47–48). For the date, see (Allen 2005, p. 98; Boardman 2006). |

| 88 | BM inv. no. 124098 (reg. no. 1931,0408.1); see (Curtis and Tallis 2005, p. 226, no. 408; Stronach 2009, p. 225) (who argues that the figurine “was intended to represent a notable personage—perhaps, in this case, a local satrap”). |

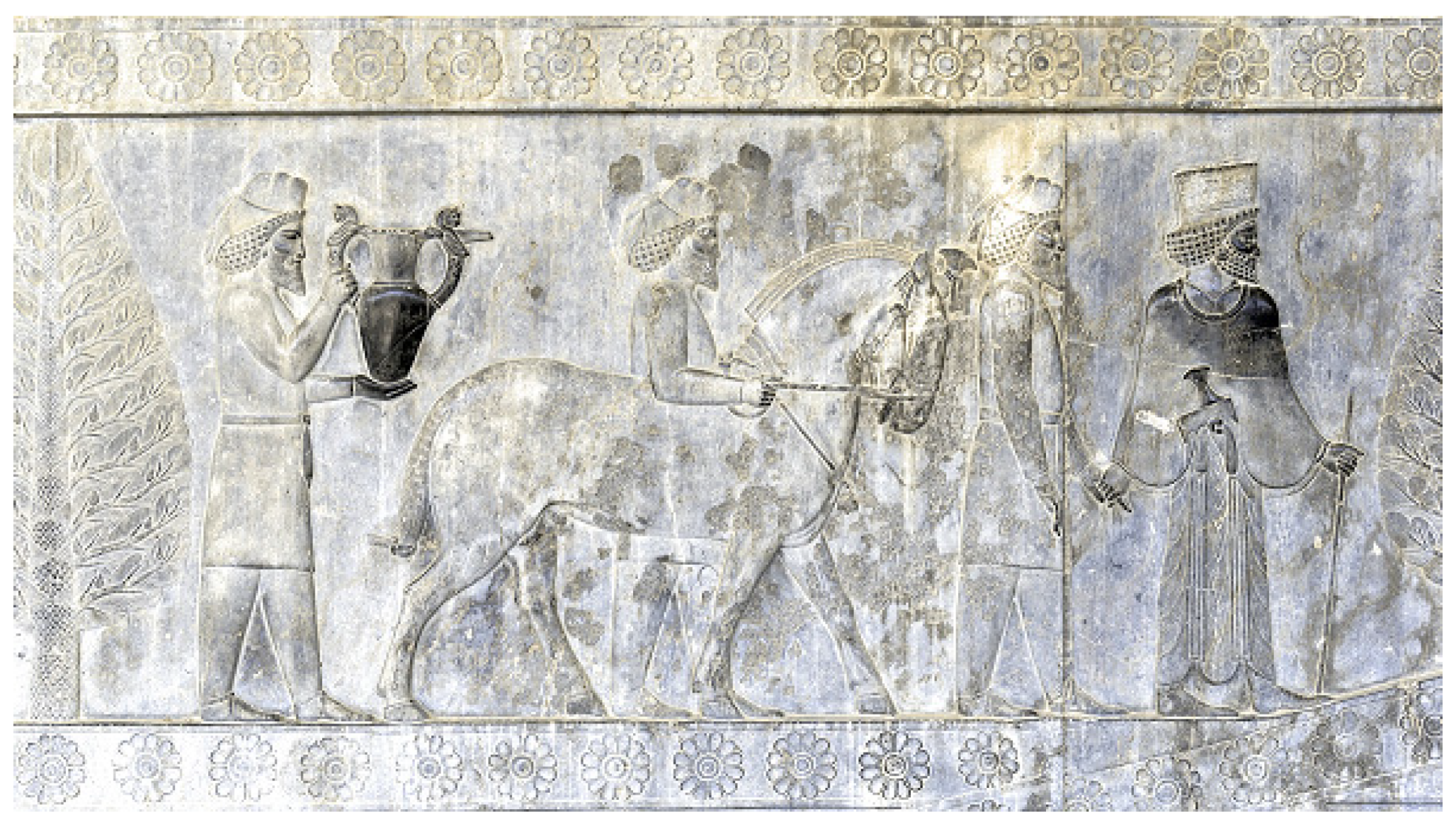

| 89 | For example, delegations identified as Armenians (No. 3), Cappadocians (No. 9), Scythians (No. 11), Sagartians (No. 16), Sogdians (No. 17) and Thracians (No. 19) bring horses, while dignitaries or guards introduce free horses and/or horse-drawn chariots; BM inv. nos. 118842–43 (reg. nos. 1818,0509.1–2); see (Schmidt 1953, pls. 29, 35, 37, 42, id. 1957, pl. 52; Barnett 1957, p. 61, pls. 15.3, 16.4, 17.1, 18.1; Walser 1966, pp. 74–75, pls. 10, 36, 39; Afshar and Lerner 1979; Mitchell 2000, p. 51, pl. 22.a–b; Curtis and Tallis 2005, p. 70, no. 25; Gabrielli 2006, pp. 5–34). |

| 90 | PF inv. nos. 1668–69, 1675, 1765, 1784–87, 1793, 1942; cf. PFa 24, 29; see (Briant 2002, pp. 426, 457, 1023). |

| 91 | Cf. Luc. Quom. hist. consc. 39 on the Nisaean horse. |

| 92 | Xen. Cyr. 8.3.23, trans. adapted from Miller (LCL series). |

| 93 | Est. 6:7–9: “For the man whom the king delights to honor, let a royal robe be brought which the king has worn, and a horse on which the king has ridden, which has a royal crest placed on its head. Then let this robe and horse be delivered to the hand of one of the king’s most noble princes that he may array the man whom the king delights to honor. Then parade him on horseback through the city square, and proclaim before him: ‘Thus shall it be done to the man whom the king delights to honor!’”. |

| 94 | Xen. Cyr. 4.3.22–23: “it will be considered improper for anyone to whom I provide with a horse to be seen going anywhere on foot” (αἰσχρὸν εἶναι, οἷς ἂν ἵππους ἐγὼ πορίσω, ἤν τις φανῇ πεζῇ ἡμῶν πορευόμενος), trans adapted from Miller, LCL series. |

| 95 | See Xen. Anab. 4.5.35; Cyr. 8.3.12, 24; Paus. 3.20.4; Philost. VA 1.31; cf. Hdt. 1.216, on the Massagetae, and also (Briant 2002, pp. 94–96, 245–46, 281) on Hdt. 1.189–90; see (Boyce 1975, pp. 122, 151). Cf. a Persian sacrifice of a horse to water at the river Strymon (Hdt. 7.113), cf. Tac. Ann. 6.37 (Parthian). |

| 96 | Yasna 1.11, 4.16, 7.12, 16.4, 22.24, 25.4, 68.22, Yasht 10.13, 90, 125, 136, 6.1, 4, 6–7, 12.34, 13.81; cf. ṚgVeda 1.162 (horse sacrifice); Yasht 10.52, 66, 68, 76 (Mithras); Just. 1.10.5; see (Aalto 1975, pp. 8–9; Frye 1984, p. 55; Kelekna 2009, pp. 113–15). |

| 97 | Arr. Anab. 6.29.7: εἶναι δὲ ἐντὸςτοῦ περιβόλου πρὸς τῇ ἀναβάσει τῇ ἐπὶ τὸν τάφονφερούσῃ οἴκημα σμικρὸν τοῖς Μάγοις πεποιημένον, οἳ δὴ ἐφύλασσον τὸν Κύρου τάφον ἔτι ἀπὸ Καμβύσου τοῦ Κύρου, παῖς παρὰ πατρὸς ἐκδεχόμενος τὴν φυλακήν. καὶ τούτοις πρόβατόν τε ἐς ἡμέραν ἐδίδοτο ἐκ βασιλέως καὶ ἀλεύρων τε καὶ οἴνου τεταγμένα καὶ ἵππος κατὰ μῆνα ἐς θυσίαν τῷ Κύρῳ; trans. Robson (LCL series). One may note that according to Ctesias (FGrH 688 F 15.51), “Cyrus” is the name by which Persians call the sun; cf. Plut. Art. 1.3 (Κῦρον γὰρ καλεῖν Πέρσας τὸν ἥλιον); Hesych., s.v. Kuros (K-4700 L). |

| 98 | See (Taqizadeh 1938, pp. 13–16). |

| 99 | Strab. 11.14.9: ὁ σατράπης τῆς Ἀρμενίας τῷ Πέρσῃ κατ’ ἔτος δισμυρίους πώλους τοῖς Μιθρακίνοις ἔπεμπεν. |

| 100 | For the identification of Mithras with the sun, see Strab. 15.3.13: τιμῶσι δὲ καὶ ῞Hλιον, ὃν καλοῦσι Μίθρην; Suda, s.v. Μίθρου, μ 1045 Adler: Μίθραν νομίζουσιν εἶναι οἱ Πέρσαι τὸν ἥλιον καὶ τούτῳ θύουσι πολλὰς θυσίας. See (Gnoli 1979; Briant 2002, pp. 251–52). At first, however, the sun was not associated with Mithras: see Yasna 1.11. |

| 101 | See Strab. 11.13.8. |

| 102 | Cf. Assyrian records of Median horse tribute (Luckenbill 1926, p. i.786, no. 795; Starr 1990, no. 66.2–5, 71.3–5; Roaf 1995, pp. 59–61; Radner 2003, pp. 45, 54). |

| 103 | See (Tuplin 2010, pp. 153–56). |

| 104 | See (Tuplin 2010, pp. 138–39), who assumes that the tribute “represents an equine resource for military purposes”, but readily admits (n. 158) that the “levying of white horses might reflect a different agenda”. |

| 105 | IrMus inv. no. IM 23.477; see (Watanabe 2002, p. 42). |

| 106 | See (Frankfort 1954, p. 78). |

| 107 | |

| 108 | See (Watanabe 2002, pp. 42–56). For different explanations, see (Root 2002, p. 198): “this related in part to the simple reason that the lion was observable as a powerful and beautiful wild animal” and on p. 200: “the lion maintained a special place, respected for its lack of fear and therefore associated with royalty”. |

| 109 | See (Pritchard 1969, pp. 585–86, lines 3, 14, 43, 71; Cornelius 1989, pp. 58–59; Watanabe 2000; Strawn 2005, pp. 152, 161, 174–84) for more references. The theme was most popular in Egypt. The ferocity of the lion was believed to be absorbed by the hero who overcame it. |

| 110 | |

| 111 | |

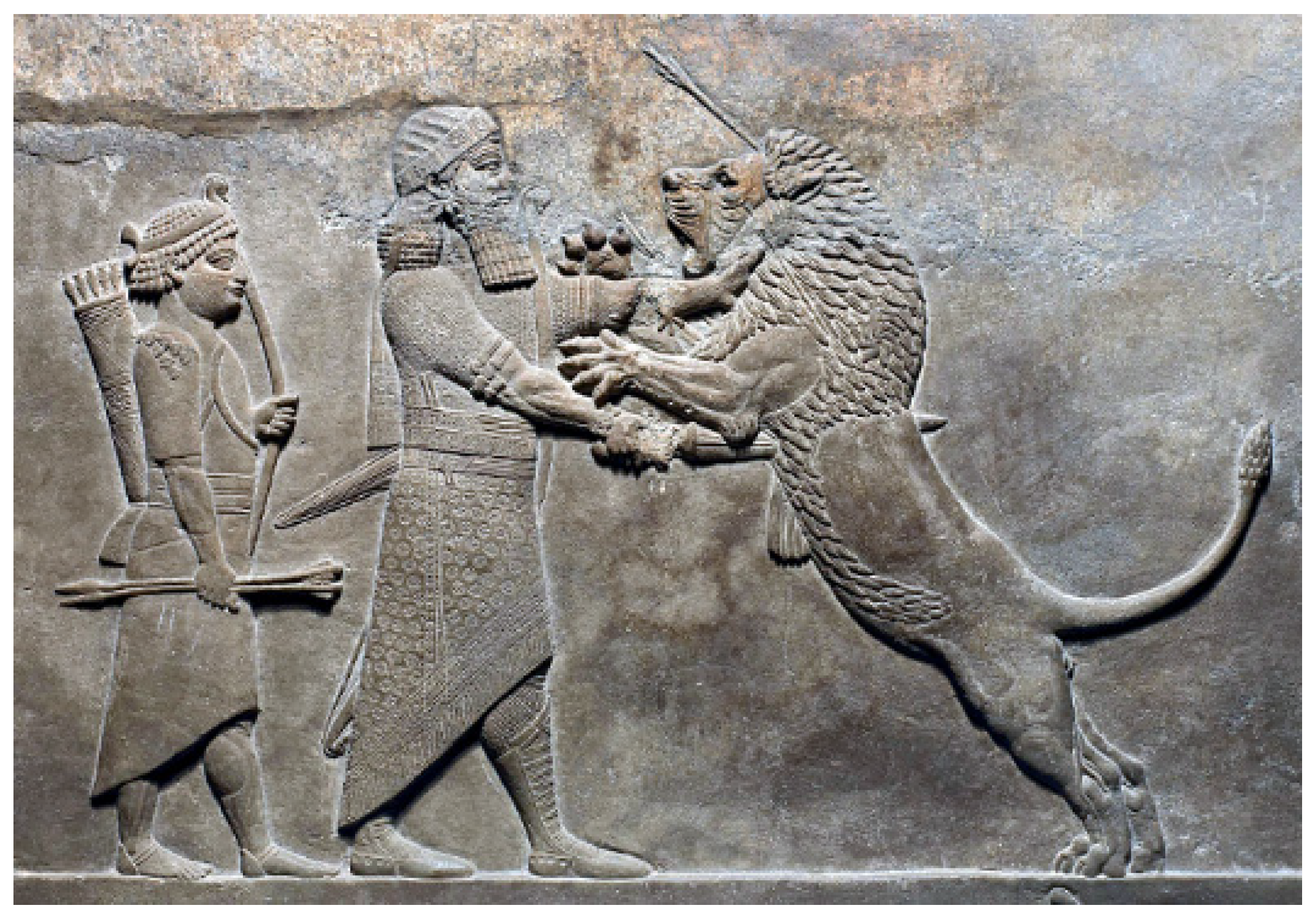

| 112 | BM inv. no. 124579; see (Curtis and Reade 1995, no. 5). |

| 113 | BM inv. no. 84672 (reg. no. 1851,0902.191); cf. BM reg. nos. 84672, K 391; see (Sachs 1953). |

| 114 | Collon 1995, n. 188, see (Weissert 1997, p. 356; Reade 1998, p. 77). |

| 115 | |

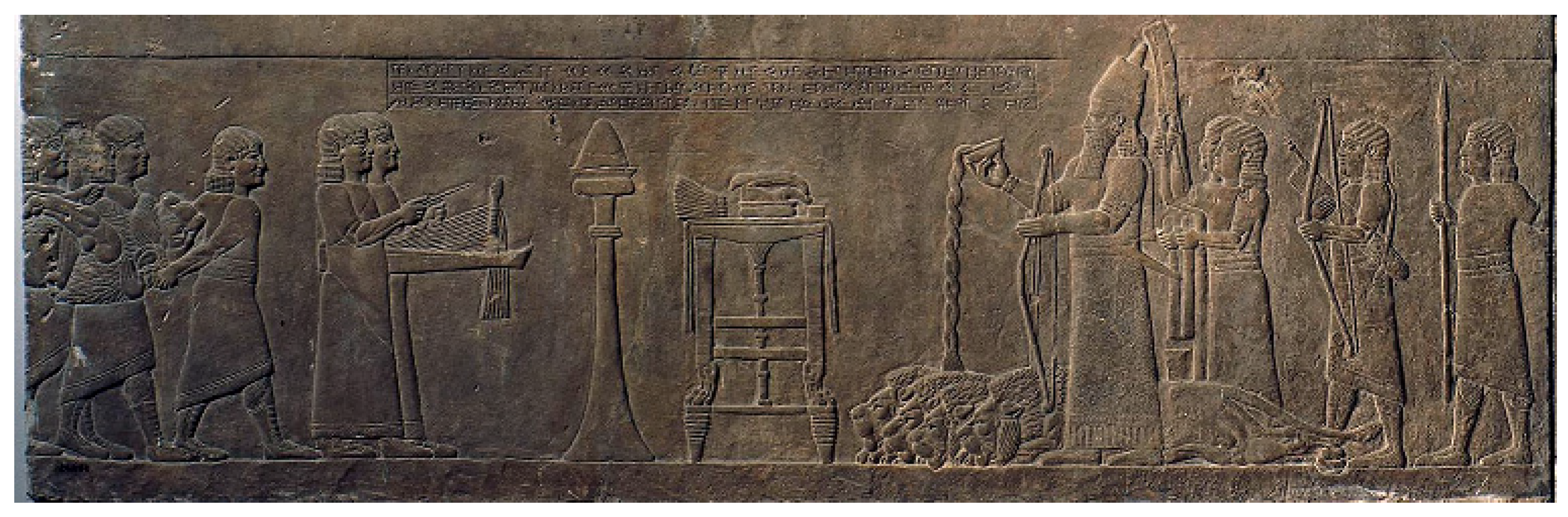

| 116 | BM inv. no. 124886 (reg. no. 1856,0909.51: central register from Room S of the North Palace); see (Frankfort 1954, pl. 108b; Barnett 1976, p. 54, pl. 57; Curtis and Reade 1995, Nos. 28–29; Strawn 2005, pp. 163–65). |

| 117 | Louvre inv. no. AO 19903 (Nineveh, North Palace, Room S). |

| 118 | BM inv. no. 124874 (reg. no. 1856,0909.48: top register from Room S of the North Palace); cf. BM inv. no. 124875 (Nineveh, North palace, Room S, Panel 11: Ashurbanipal on horseback killing lion with spear); see (Frankfort 1954, pl. 113; Barnett 1976, p. 51, pl. 49). |

| 119 | See (Strawn 2005, nn. 170–71). |

| 120 | BM inv. no. 124886 (reg. no. 1856,0909.51: lower register from Room S of the North Palace); see (Frankfort 1954, pl. 108b; Barnett 1976, p. 54, pl. 57; Curtis and Reade 1995, Nos. 28–29; Strawn 2005, pp. 163–65). |

| 121 | See (Schmitt 1988, p. 29). |

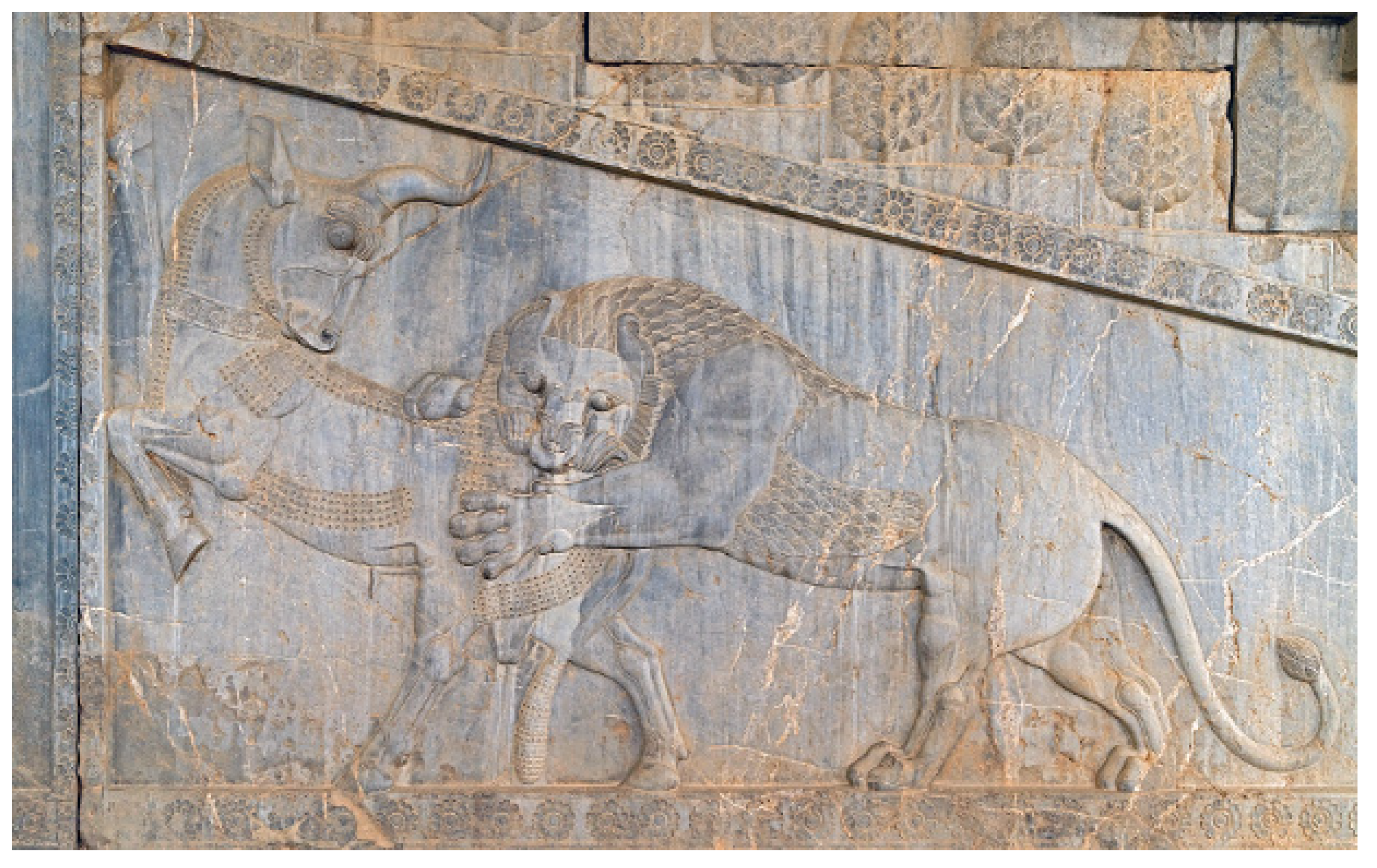

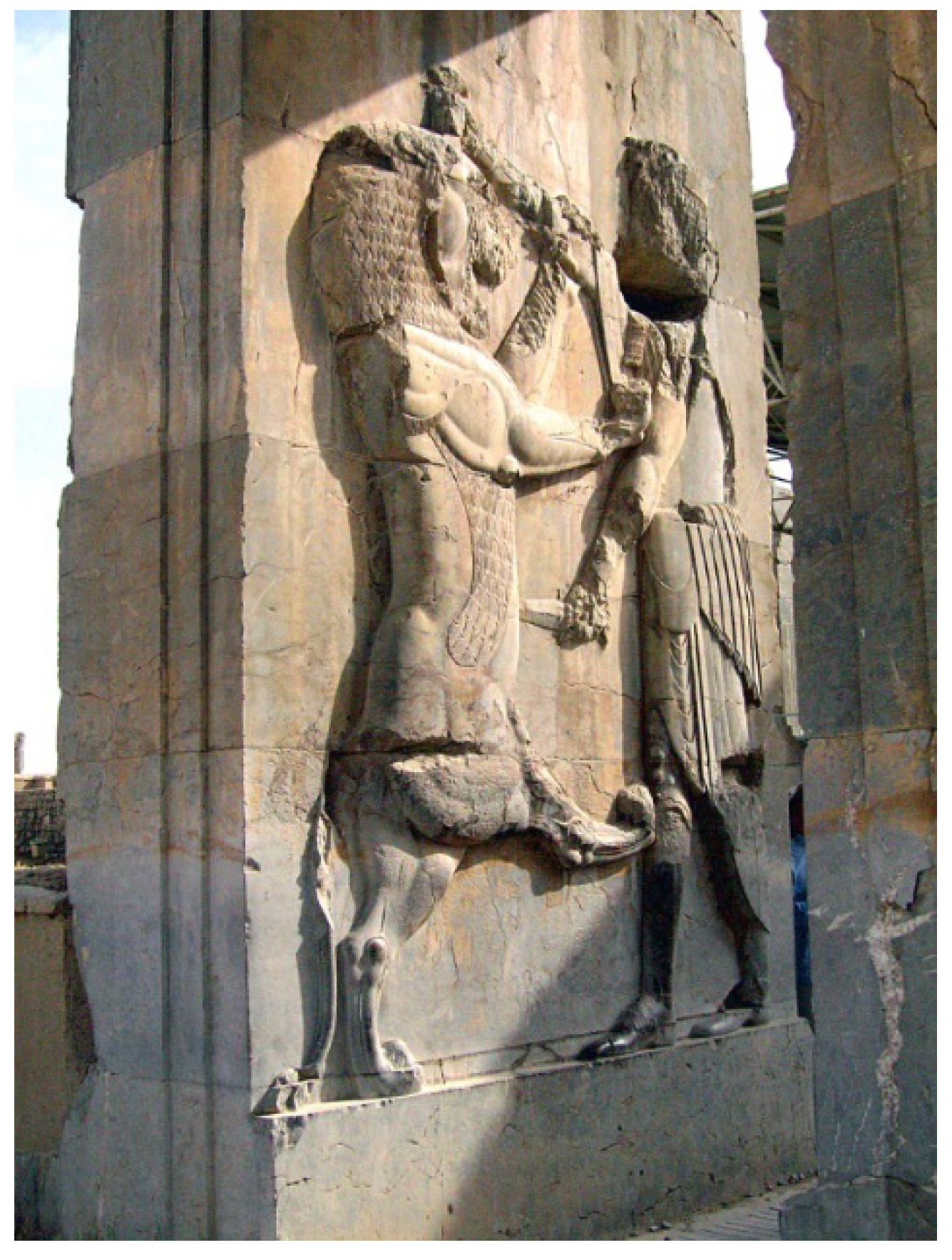

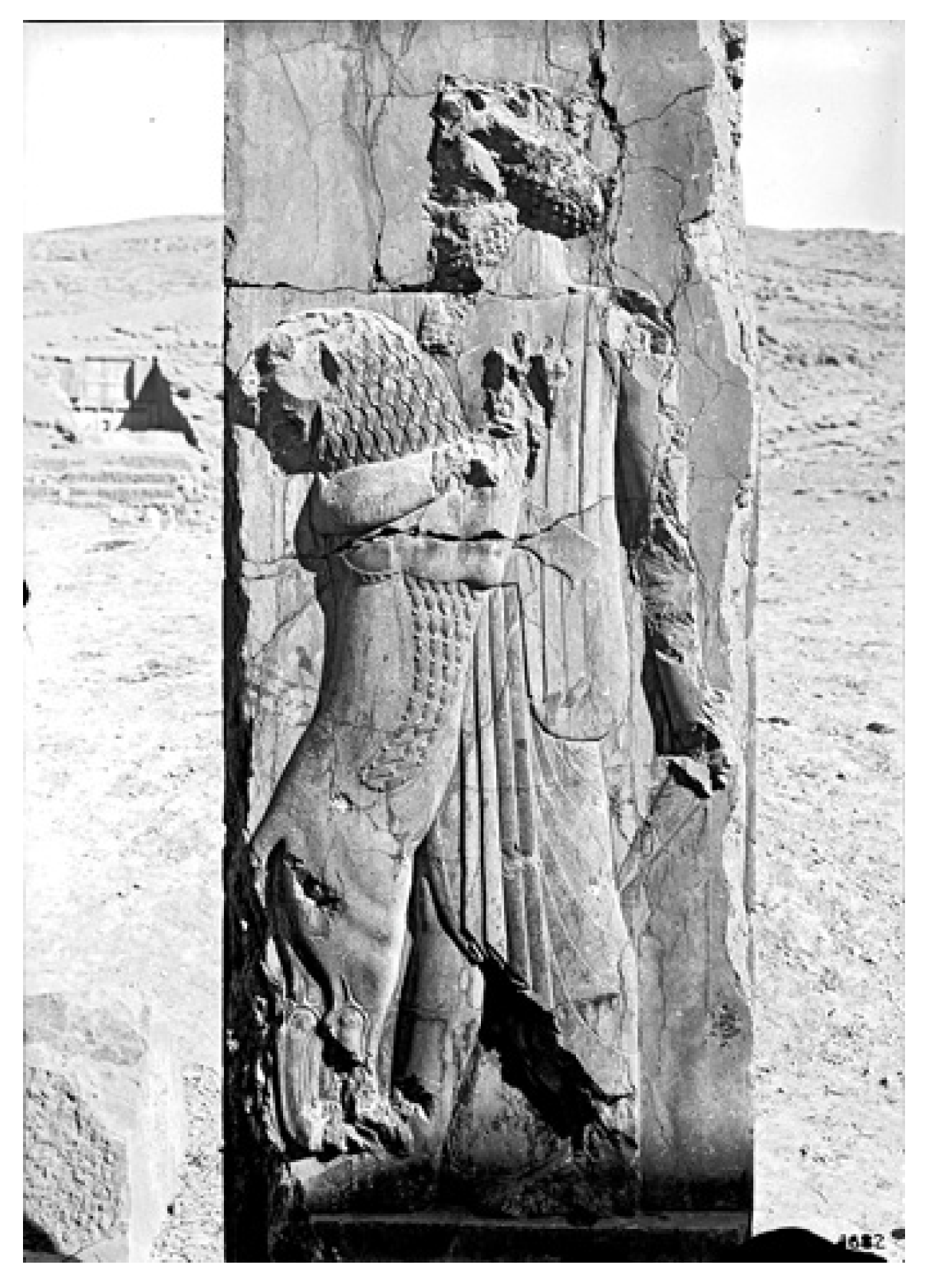

| 122 | |

| 123 | OIM reg. no. A27903 (acc. no. 2953: black limestone cylinder seal; unknown provenance (mod. Iraq); Akkadian, ca. 3rd mill. bce): depicting Ishtar-Inanna with foot on back of lion; see (Seidl 1989, p. 139; Watanabe 2002, pp. 90–91; Collins 2009, pp. 23–24). |

| 124 | Louvre inv. nos. Sb 54-Sb 6617; see (André-Salvini 1992). |

| 125 | A guardian lion also originally appeared on a votive foundation bolder dedicated by Puzur-Inshushinak, designed to protect a building, now in fragments (Louvre inv. no. Sb 6, 177). Only the nose and a claw of the lion at the left side remain (Amiet 1966, pp. 223–29). |

| 126 | Cf. Vorderasiatisches Museum, Berlin, VA 1392, 1408–56. See (Strawn 2005, p. 224): “the lion lends its protective force to the entirety of the city”. |

| 127 | INM inv. no. 1392; see (Curtis and Tallis 2005, p. 98, no. 85). |

| 128 | INM inv. no. 1321; see (Curtis and Tallis 2005, p. 121, no. 118). |

| 129 | Louvre inv. no. Sb 2716; see (Amiet 1966, pp. 524–25; Root 2002, p. 200). |

| 130 | Central register of Ashurbanipal’s hunting relief (BM inv. nos. 124886–87). |

| 131 | BM inv. no. 124874; see (Almagor forthcoming). |

| 132 | See (Curtis and Reade 1995, no. 28–29). According to (Razmjou 2018, p. 353), Ashurbanipal’s lion hunting had such a strong symbolism, that the lions may actually stood in for his enemies in Elam. |

| 133 | OIM reg. no. A24077 (acc. no. 2110: grey limestone statue; Persepolis, Persia; Achaemenid, ca. 550–330–bce); see (Schmidt 1957, p. 70, pl. 36; Root 2002, p. 200). |

| 134 | See (Strawn 2005, p. 225). |

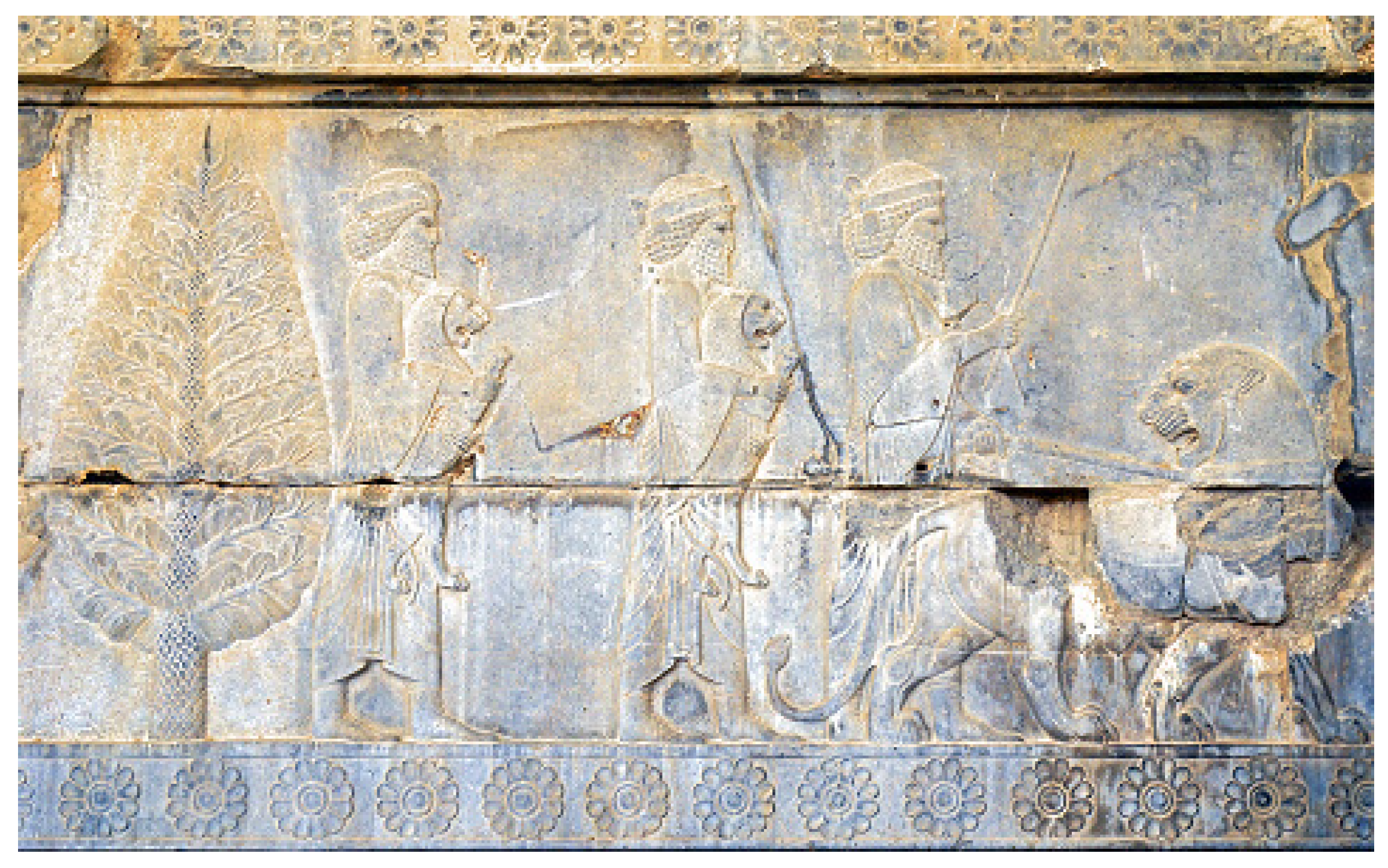

| 135 | See (Schmidt 1953, pl. 19) (Apadana, eastern stairway); cf. ibid. pls. 20 (eastern stairway, southern section), 53 (northern stairway), 61 (northern stairway, west wing), 62 (Council Hall, main stairway), 66 (main stairway, east wing), 69 (main stairway, west wing), 126 (Tachara, Palace of Darius), 153a (western stairway, southern end), 159 (Palace of Xerxes), 161 (western stairway, southern flight), 166 (eastern stairway), 169a (eastern stairway), and 203d (Palace H). |

| 136 | OIM reg. no. A73100 (fragment of west portion of façade); see (Schmidt 1953, pl. 203). |

| 137 | For example, Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, acc. no. 48.1318 (decorated bronze shield boss; Khorsabad; 8th cent. bce); see (Hartner 1965, p. 1). |

| 138 | See (Root 2002, pp. 201–3). |

| 139 | See (Hartner and Ettinghausen 1964, pp. 161–64; Hartner 1965, pp. 15–16): in the starry heaven of c. 4000 bce, Lion was at Zenith and Taurus invisible below the horizon. |

| 140 | |

| 141 | See (Strawn 2005, pp. 224–25). |

| 142 | See (Schmidt 1953, pl. 142a) (Tachara, Palace of Darius, western doorway in the north wall of the main hall). |

| 143 | MMA acc. no 61.100.10; see (Marcus 1994, p. 11) (interpreting the ornaments as “symbols of security, providing women with personal protection (magical and physical) both in daily life and in the underworld)”; see (Root 2002, pp. 198–9; Muscarella 2004, p. 707, fig. 11). Sixty such pins have been excavated, mostly in the so-called Burned Building II. |

| 144 | INM inv. no. 2351; see (Schmidt 1957, p. 77, fig. 14B; Curtis and Tallis 2005, p. 147, no. 190). Cf. the striding lion gold plaque in the BM. inv. no. 132108. |

| 145 | IMN old inv. no. PT5 642; see (Schmidt 1957, p. 69, pl. 33; Cahill 1985, p. 384, fig. 2). |

| 146 | IMN old inv. no. PT5 10 (green chert tripod bowl with leonine legs; Treasury (Hall 39, Persepolis; Achaemenid, ca. 550–330 BCE); Schmidt 1957, p. 89, pl. 55.3 (intended for ritualistic purposes?). |

| 147 | |

| 148 | See (Schmidt 1953, pl. 115a) (south jamb of the southern doorway in the western wall, Throne Hall, Persepolis). |

| 149 | See (Schmidt 1953, pl. 147a) (Tachara, Palace of Darius, Persepolis, east jamb of southern doorway of room 16) and pl. 147d (Tachara, Palace of Darius, Persepolis, west jamb of southern doorway of room 5). |

| 150 | See (Root 1979, pp. 304–8; Kuhrt 2007, p. 2.546). See (Allen 2005, p. 77) on this transformation into an Achaemenid theme. |

| 151 | See (Root 1979, p. 304; Allen 2005, p. 77; Kuhrt 2007, p. 2.546). Yet, see (Wiesehöfer 2001, pp. 24, 220). |

| 152 | As persuasively suggested by (Root 1979, pp. 305–7). Cf. DNa 4.43-47: “The Persian man has gone forth far”. See (Barnett 1957, p. 77 n. 2): “[t]he theme of the lion hunt, treated by the Assyrians as a major subject of narrative art, has shrunk at Persepolis to a formal and unconvincing, almost heraldic single combat between the Persian king, typifying good, and a lion, bull or monster, typifying evil” (Seyer 2007). |

| 153 | See (Schmidt 1957, p. 32, no. 37, pl. 11, PT 383; p. 37, no. 59, pl. 13, PT6 168). |

| 154 | |

| 155 | See (Schmidt 1957, pp. 7, 19, no. 3, pl. 3, PT4 860, PT4 331, p. 21, no. 6, pl. 4, PT4 749, PT4 862, p. 22, no. 8, pl. 5, PT4 471, PT4 549a [two heroes against two lions], p. 23, no. 10, pl. 5, PT4 769, no. 12, pl. 5, PT4 979). |

| 156 | |

| 157 | Louvre inv. no. AO 19862 (Palace of Sargon II, Throne Room, façade N); see (Beyer 1990, fig. 23). |

| 158 | Louvre inv. no. AO 19861. |

| 159 | |

| 160 | See (Schmidt 1953, pl. 28b) (Apadana, Tribute Procession, Eastern Stairway; there is a parallel scene in the northern stairway, but the upper panel is missing). |

| 161 | BM inv. no. 123923 (reg. no. 1897,1231.22); see (Dalton 1964, pp. 9–11, no. 22, pl. 9; Stronach 1998; Curtis and Tallis 2005, p. 233, no. 431). |

| 162 | Cf. MMA acc. no. 1984.383.25. |

| 163 | |

| 164 | BM inv. nos. 124579 and 124532; see (Curtis and Reade 1995, Nos. 5–6). |

| 165 | See (Boardman 1970, pp. 314–16, pls. 889, 924, 929). Cf. BM inv. no. 89583 (reg. no. N.1082: cylinder seal; S-E Palace, Nimrud; Achaemenid, ca. 550–330 bce): a rider aims a spear at a rampant lion; BM inv. no. 89816 (reg. no. 1869,0122.10: fragmentary cylinder seal; unknown provenance (Asia); Achaemenid, ca. 5th cent. bce): a rider turning back in his saddle to aim an arrow (the so-called “Parthian shot”). |

| 166 | |

| 167 | Reliefs of hunting scenes (of a stag and a boar) on one of the long sides of a fourth-century bce marble sarcophagus have been recently (1998) discovered within a plundered tumulus at Çan, between Ilion and Dascyleum; see (Sevinç et al. 2001). |

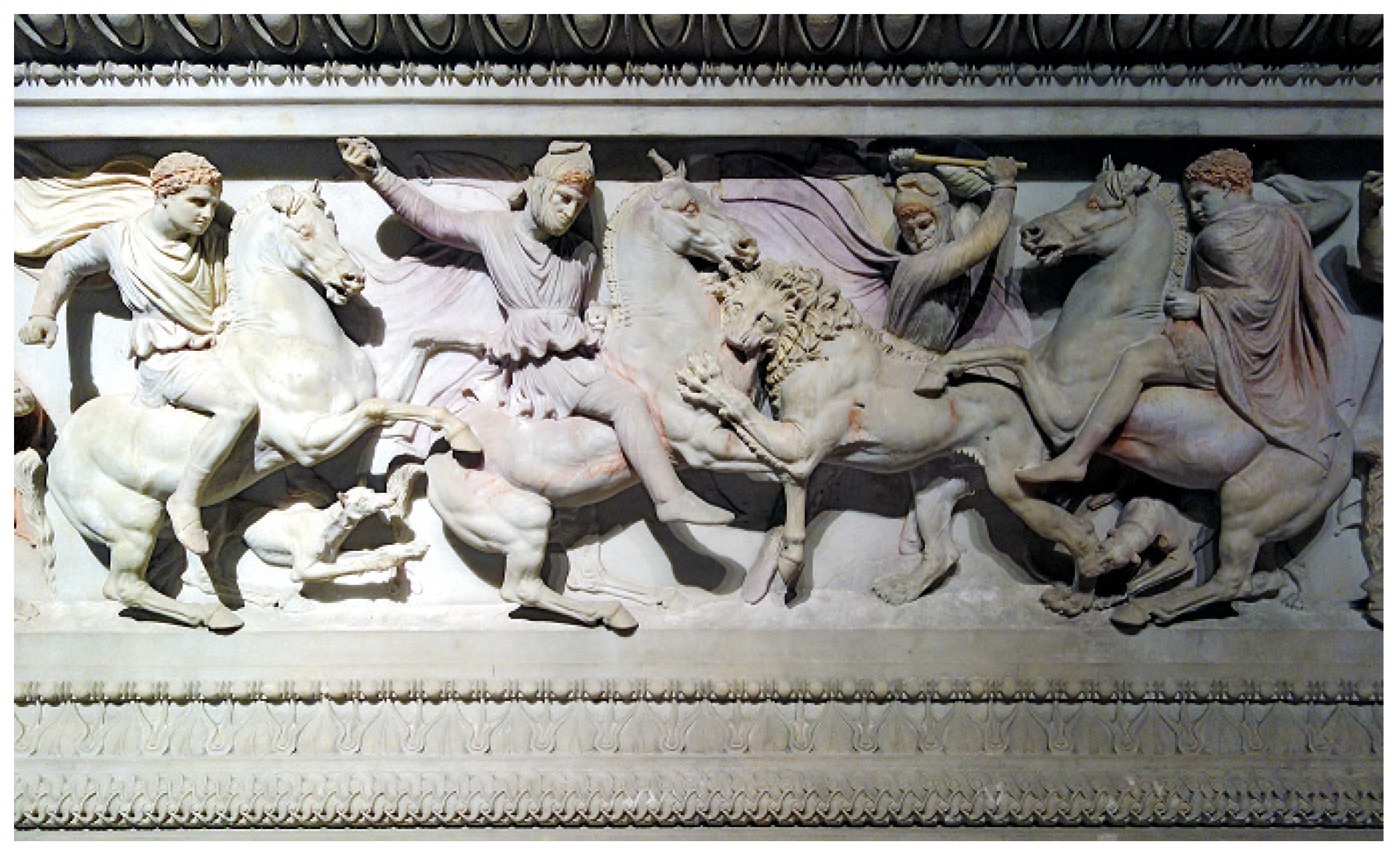

| 168 | IAM inv. no. 72; see (Anderson 1985, pp. 70, 78–79; Lane-Fox 1996, pp. 138, 142; Barringer 2001, pp. 200–1; Palagia 2000, pp. 167, 175–84, 191–99). The Macedonian lion hunting, however, was probably practiced prior to the conquest of Persia; see (Hull 1964, pp. 101–2; Anderson 1985, p. 80; Briant 1991; Lane-Fox 1996, pp. 137–39, 143). |

| 169 | Diod. 2.8.6: ἡ Σεμίραμις ἀφ’ ἵππου πάρδαλιν ἀκοντίζουσα, καὶ πλησίον αὐτῆς ὁ ἀνὴρ Νίνος παίων ἐκ χειρὸς λέοντα λόγχῃ. |

| 170 | See (Briant 2002, p. 207). |

| 171 | Diod. 2.7.1, 3–4, 2.8.5. It is set by Jacoby as part of his lengthy FGrH 688 F 1b. |

| 172 | He was certainly in Babylonia: as Parysatis’ physician (FGrH 688 F 27.69), he most probably accompanied her during her sojourn there (Plut. Art. 19.10); cf. the constant allusions to Babylon in his Indica: F 45bα, 45.29. See (Almagor 2012, pp. 19–20). |

| 173 | See (Briant 2002, p. 297). |

| 174 | Plut. Them. 29.6 (καὶ κυνηγεσίων βασιλεῖ μετέσχε); see (Frost 1980, pp. 220–23; Marr 1998, pp. 226–28; Keaveney 2003, pp. 39–87). |

| 175 | See (Llewellyn-Jones 2013, p. 131). |

| 176 | The Macedonians king boasts to have allegedly killed a large number of beasts, following the Mesopotamian practice noted above: (Curt. Ruf. 8.1.19: 4000); cf. Lysimachus who hunted a huge lion (ib. 8.1.15, cf. Justin, 15.3.7-8), and Perdiccas who captured lion cubs (Ael. VH 12.39). |

| 177 | See (Llewellyn-Jones 2013, p. 130). |

| 178 | See Xen. Cyr. 1.4.14. |

| 179 | Xen. Cyr. 8.8.12 (Ἀλλὰ μὴν καὶ ἐπὶ θήραν πρόσθεν μὲν τοσαυτάκις ἐξῇσαν ὥστε ἀρκεῖν αὐτοῖς τε καὶ ἵπποις γυμνάσια τὰς θήρας· ἐπεὶ δὲ Ἀρταξέρξης ὁ βασιλεὺς καὶ οἱ σὺν αὐτῷ ἥττους τοῦ οἴνου ἐγένοντο, οὐκέτι ὁμοίως οὔτ’ αὐτοὶ ἐξῇσαν οὔτε τοὺς ἄλλους ἐξῆγον ἐπὶ τὰς θήρας), trans. adapted from Miller (LCL series). |

| 180 | Hdt. 9.122: …φιλέειν γὰρ ἐκ τῶν μαλακῶν χώρων μαλακοὺς γίνεσθαι· οὐ γὰρ τι τῆς αὐτῆς γῆς εἶναι καρπόν τε θωμαστὸν φύειν καὶ ἄνδρας ἀγαθοὺς τὰ πολέμια, trans. Godley (LCL series). |

| 181 | Hdt. 1.126: ἄνδρες Πέρσαι, οὕτω ὑμῖν ἔχει. βουλομένοισι μὲν ἐμέο πείθεσθαί ἔστι τάδε τε καὶ ἄλλα μυρία ἀγαθά, οὐδένα πόνον δουλοπρεπέα ἔχουσι, μὴ βουλομένοισι δὲ ἐμέο πείθεσθαι εἰσὶ ὑμῖν πόνοι τῷ χθιζῷ παραπλήσιοι ἀναρίθμητοι. νῦν ὦν ἐμέο πειθόμενοι γίνεσθε ἐλεύθεροι… ὡς ὦν ἐχόντων ὧδε, ἀπίστασθε ἀπ᾽ Ἀστυάγεος τὴν ταχίστην, trans. adapted from Godley (LCL series). |

| 182 | On which see recently (Pelling 2019, pp. 92–93). |

| 183 | Another manner in which Herodotus recounts the unnatural progression of the Persians from one mode of life to another is through the fantastic portent just at the moment Xerxes’ army was about to cross into Europe: a horse gives birth to a hare (7.57). While playing with the notion of hybridity, which symbolizes Cyrus the Great and the Persians (see above), Herodotus also commented this way on the metamorphosis of the Persians into restless imperialists moving from one place to another (cf. the use of a hare to denote the similar transition of the Spartans towards imperialism in Plut. Cim. 16.5). |

| 184 | See the expression Pârsa utâ Mâda (DB 1.41, 1.46–47, 2.18, 2.81–82, 3.29–30, 3.77). Cf. Esther 1:3, 14, 1:13, cf. 10:2, Medes and Persians: Daniel 5:23, 6:8, 12, 15, 8:20. See, however (Stronach 2009, p. 222). |

| 185 | Persons in alternate Persian and Median clothing in the Persepolis reliefs: see (Schmidt 1953, pp. 83–84, 107, 141, 225, 228, 240, 243, 280, pls. 22, 53, 64–65, 85–86, 96–101, 134–35, 161, 163–65, 185c–d, 203a, 204a, 205; Roaf 1983, pp. 29–30, 41, 83, 85, 103–14, 124, 140–41, 145, 149; Root 1979, p. 282). |

| 186 | This is the Median robe (Μεδίκη στολή). See (Schoppa 1933, pp. 46–48; Schmidt 1953, pl. 35; Shahbazi 1978, pp. 498–99; Moorey 1985, pp. 23–26). It was an upper garment/ coat with long, false sleeves, called Kandys; see (Widengren 1956, pp. 235, 237–38). A purple robe: cf. Xen. Cyr. 8.3.10; Pollux 7.58; possibly Strabo, 15.3.19; cf. Hdt. 3.20, 9.109 with (Thompson 1965, p. 122). Trousers were also part of the “Median” costume (cf. Hdt. 1.71, 7.64; Xen. Anab. 1.5.8), as well as a belted skirt. |

| 187 | This is the royal or Persian robe (presumably from an Elamite origin), the two-piece red or purple loose pleated garment. See (Schoppa 1933, p. 47; Schmidt 1953, p. 163; 1970, p. 80; Goldman 1964; Walser 1966, p. 72; Moorey 1985, p. 24). It was most probably the purple tunic (χιτών) with the white middle (μεσόλευκος): cf. Hdt. 7.61; Xen. Anab. 1.5.8, Cyr. 1.3.2, 8.3.13 (together with Median articles of clothing); Ephippus ap. Ath. 12.537e [Alexander]; called Sarapis in Elamite and Persian: Hesychius, s.v. “Sarapis”, Photius, Lexicon, s.v. “Sarapis”. Cf. Plut. Alex. 51.5 with (Collins 2012, pp. 387–90). See also Diod. 17.77.5–6, Curt. Ruf. 3.3.17. Cf. Duris ap. Ath, 12.535e [Pausanias]. Ancient authors appear to confuse the Median and the Persian robes, erroneously deeming the former as more luxurious and the latter simpler: cf. Hdt. 1.71, 1.135; Xen. Cyr. 2.4.5, 8.1.40–41, 8.3.3, influencing the Alexander historians (cf. Plut. Alex. 45.2, De Fort. Alex. Magn. 329f–330a). Some modern scholars also conflate the two: cf. Schmidt 1953, p. 168 n. 38. Others believe that there was indeed a transition from an Elamite/Persian dress to a Median one in the early fifth century bce: see (Sekunda 2010, pp. 255–64). |

| 188 | See (Thompson 1965, p. 123): “while the [Median dress] was well adapted to the way of life pursued by nomad warriors and hunters, the Persian robe did not share this advantage, being full and voluminous”. |

| 189 | Hdt. 1.135, 6.112; Ctesias (FGrH 688 F 1b.2.23.1–4: the Median effeminate decadence of Sardanapalus); Xen. Cyr. 8.8.15; Strabo 11.13.9. |

References

- Aalto, Pentti. 1975. The Horse in Central Asian Nomadic Cultures. Studia Orientalia 46: 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Afshar, Ahmad, and Judith Lerner. 1979. The Horses of the Ancient Persian Empire at Persepolis. Antiquity 53: 44–47. [Google Scholar]

- Albenda, Pauline. 1972. Ashurnasirpal II Lion Hunt Relief BM 124534. Journal of Near Eastern Studies 31: 167–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albenda, Pauline. 1974. Lions on Assyrian wall reliefs. Journal of the Ancient Near Eastern Society 6: 1–27. [Google Scholar]

- Alizadeh, Abbas. 2008. Prehistoric Mobile Pastoralism in Southwestern Iran. In Nomads, Tribes, and State in the Ancient Near East. Edited by Jeffrey Szuchman. Chicago: Chicago University Press, pp. 129–46. [Google Scholar]

- Allen, Lindsay. 2005. The Persian Empire: A History. London: The British Museum Press. [Google Scholar]

- Allen, Lindsay, John Ma, Christopher J. Tuplin, and David G. K. Taylor. 2014. The Arshama Letters from the Bodleian Library, Volume 2 Part 1: Edition of the Egyptian Aramaic Documents in the Bodleian Library. Available online: http://blogs.bodleian.ox.ac.uk/wp-content/uploads/sites/116/2013/10/Vol-2-intro-25.1.14.pdf (accessed on 9 May 2021).

- Almagor, Eran. 2012. Ctesias and the Importance of his Writings Revisited. Electrum 19: 9–40. [Google Scholar]

- Almagor, Eran. 2014. Hold Your Horses: Characterization through Animals in Plutarch’s Artaxerxes, Part II. Ploutarchos 11: 3–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almagor, Eran. 2018. Plutarch and the Persica. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Almagor, Eran. 2021. The Royal Road from Herodotus to Xenophon (Via Ctesias). In Aršāma and His World: The Bodleian Letters in Context. Edited by Christopher J. Tuplin and John Ma. Oxford: Oxford University Press, pp. 147–85. [Google Scholar]

- Almagor, Eran. forthcoming. Hunting and Leisure Activities. In A Companion to the Achaemenid Persian Empire. Edited by Bruno Jacobs and Robert Rollinger. Malden: Wiley-Blackwell.

- Amiet, Pierre. 1966. Elam. Auvers-sur-Oise: Archee. [Google Scholar]

- Anderson, John Kinlich. 1985. Hunting in the Ancient World. Berkeley: University of California Press. [Google Scholar]

- André-Salvini, Béatrice. 1992. The Monuments of Puzur-Inshushinak. In The Royal City of Susa: Ancient Near Eastern Treasures in the Louvre. Edited by Prudence Oliver Harper, Joan Aruz and Françoise Tallon. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, pp. 87–91. [Google Scholar]

- Anthony, David. W., and Dorcas R. Brown. 2000. Eneolithic Horse Exploitation in the Eurasian Steppes: Diet, Ritual and Riding. Antiquity 74: 75–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anthony, David W., Dimitri Y. Telegin, and Dorcas R. Brown. 1991. The Origin of Horseback Riding. Scientific American 265: 94–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Archie, Andre. 2015. Politics in Socrates’ Alcibiades: A Philosophical Account of Plato’s Dialogue Alcibiades Major. New York: Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Asheri, David, Alan Brian Lloyd, and Aldo Corcella, eds. 2007. A Commentary on Herodotus: Books I–IV. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Barnett, Richard D. 1957. Persepolis. Iraq 19: 55–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barnett, Richard D. 1976. Sculptures from the North Palace of Ashurbanipal at Nineveh (668–627 B.C.). London: British Museum. [Google Scholar]

- Barringer, Judith M. 2001. The Hunt in Ancient Greece. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Benveniste, Émile. 1932. Les classes sociales dans la tradition avestique. Journal Asiatique 221: 117–34. [Google Scholar]

- Beyer, Dominique. 1990. Le palais de Sargon II, roi d’Assyrie. Le Monde de la Bible 67: 19–21. [Google Scholar]

- Boardman, John. 1970. Greek Gems and Finger Rings: Early Bronze Age to Late Classical. London: Thames and Hudson. [Google Scholar]

- Boardman, John. 2000. Persia and the West. An Archaeological Investigation of the Genesis of Achaemenid Art. London: Thames and Hudson. [Google Scholar]

- Boardman, John. 2006. The Oxus Scabbard. Iran 44: 115–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boyce, Mary. 1975. A History of Zoroastrianism. Leiden: Brill, vol. 1. [Google Scholar]

- Briant, Pierre. 1991. Chasses royales macédoniennes et chasses royales perses: Le thème la chasse au lion sur la chasse de Vergina. DHA 17: 211–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Briant, Pierre. 2002. From Cyrus to Alexander. Winona Lake: Eisenbrauns. [Google Scholar]

- Cahill, Nicholas. 1985. The Treasury at Persepolis: Gift-Giving at the City of the Persians. American Journal of Archaeology 89: 373–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collins, Paul. 2009. Assyrian Palace Sculptures. Austin: University of Texas Press. [Google Scholar]

- Collins, Andrew W. 2012. The Royal Costume and Insignia of Alexander the Great. American Journal of Philology 133: 371–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Collon, Dominique. 1995. Ancient Near Eastern Art. Berkeley: University of California Press. [Google Scholar]

- Cornelius, Izak. 1989. The Lion in the Art of the Ancient Near East: A Study of Selected Motifs. Journal of Northwest Semitic Languages 15: 53–85. [Google Scholar]

- Cremer, Marielouise. 1984. Zwei neue graeco-persische Stelen. Epigraphica Anatolica 3: 87–99. [Google Scholar]

- Curtis, John E., and Julian E. Reade, eds. 1995. Art and Empire: Treasures from Assyria in the British Museum. Exhibition Catalogue. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art. [Google Scholar]

- Curtis, John E., and Nigel Tallis, eds. 2005. Forgotten Empire: The World of Ancient Persia. London: The British Museum Press. [Google Scholar]

- Dalton, Ormonde Maddock. 1964. Treasure of the Oxus with Other Examples of Early Oriental Metal-Work, 3rd ed. London: The British Museum Press. [Google Scholar]

- Denyer, Nicholas. 2001. Plato: Alcibiades. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Downs, James F. 1961. The Origin and Spread of Riding in the Near East and Central Asia. American Anthropologist 63: 1193–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drews, Robert. 2004. Early Riders. The Beginnings of Mounted Warfare in Asia and Europe. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Driver, Godfrey R. 1965. Aramaic Documents of the Fifth Century B.C. Oxford: Clarendon Press. [Google Scholar]

- Durand, Jean-Marie. 1998. Documents Epistolaires du Palais de Mari. Paris: Cerf, vol. 2. [Google Scholar]

- Dyson, Robert H., Jr. 1961. Excavating the Mannaean Citadel of Hasanlu; and New Light on Several Millennia of Persian Azerbaijan. Illustrated London News 239: 534–37. [Google Scholar]

- Farkas, Ann. 1974. The Horse and Rider in Achaemenid Art. Persica 4: 57–76. [Google Scholar]

- Frankfort, Henri. 1939. Cylinder Seals. London: Macmillan. [Google Scholar]

- Frankfort, Henri. 1954. The Art and Architecture of the Ancient Orient. London: Penguin Books. [Google Scholar]

- Frost, Frank J. 1980. Plutarch’s Themistocles: A Historical Commentary. Princeton: Princeton University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Frye, Richard Nelson. 1984. The History of Ancient Iran. Munich: Beck. [Google Scholar]

- Gabrielli, Marcel. 2006. Le Cheval dans l’Empire Achéménide. Istanbul: Ege Yayinlari. [Google Scholar]

- Garrison, Mark B. 2011. The Seal of “Kuras the Anzanite, Son of Sespes” (Teispes), PFS 93*: Susa—Ansan—Persepolis. In Elam and Persia. Edited by Javier Álvarez-Mon and Mark B. Garrison. Winona Lake: Eisenbrauns, pp. 375–405. [Google Scholar]

- Garrison, Mark B., and Margaret Cool Root. 1996. Persepolis Seal Studies. An Introduction with Provisional Concordances of Seal Numbers and Associated Documents on Fortification Tablets 1–2087. Leiden: Brill. [Google Scholar]

- Gershevitch, Ilya. 1959. The Avestan Hymn to Mithra. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Gheorghiu, Dragoş. 1993. A First Representation of a Domesticated Horse in the 5th Millennium B.C. in Eastern Europe? Ceramic Evidence. In The History of the Knowledge of Animal Behavior. Edited by Liliane Bodson. Liège: Université de Liège, pp. 95–115. [Google Scholar]

- Ghirshman, Roman. 1954. Iran from the Earliest Times to the Islamic Conquest. Harmondsworth: Penguin Books. [Google Scholar]

- Gnoli, Gherardo. 1979. Sol Persice Mithra. In Mysteria Mithrae. Edited by Ugo Bianchi. Leiden: Brill, pp. 725–40. [Google Scholar]

- Goldman, Bernard. 1964. Origin of the Persian Robe. Iranica Antiqua 4: 133–52. [Google Scholar]

- Graf, David F. 1994. The Persian Royal Road System. Achaemenid History 8: 167–89. [Google Scholar]

- Grayson, Albert Kirk. 1991. Assyrian Rulers of the Early First Millennium BC, I: 1114–859 BC, Royal Inscriptions of Mesopotamia., Assyrian Periods, 2. Toronto: University of Toronto Press. [Google Scholar]

- Gribble, David. 1999. Alcibiades and Athens: A Study in Literary Presentation. Oxford: Clarendon Press. [Google Scholar]

- Hall, Edith. 1989. Inventing the Barbarian. Oxford: Clarendon Press. [Google Scholar]

- Hanslik, Rudolf. 1936. Nisaîon pedíon. Realencyclopädie der classischen Altertumswissenschaft 17: 712–13. [Google Scholar]

- Hansman, John. 1972. Elamites, Achaemenians and Anshan. Iran 10: 101–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartner, Willy. 1965. The Earliest History of the Constellations in the Near East and the Motif of the Lion-Bull Combat. Journal of Near Eastern Studies 24: 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartner, Willy, and Richard Ettinghausen. 1964. The Conquering Lion, the Life Cycle of a Symbol. Oriens 17: 161–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herzfeld, Ernst. 1929. Bericht über die Ausgrabungen von Pasargadae, 1928. Archäologische Mitteilungen aus Iran 1: 4–16. [Google Scholar]

- Herzfeld, Ernst. 1941. Iran in the Ancient East. New York and London: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Herzfeld, Ernst. 1968. The Persian Empire: Studies in Geography and Ethnography of the Ancient Near East. Wiesbaden: Steiner. [Google Scholar]

- Hull, Denison Bingham. 1964. Hounds and Hunting in Ancient Greece. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. [Google Scholar]

- Justi, Ferdinand. 1895. Iranisches Namenbuch. Marburg: Olms. [Google Scholar]

- Kahn, Dan’el. 2008. Inaros’ rebellion against Artaxerxes I and the Athenian Disaster in Egypt. Claasical Quarterly 58: 424–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kawami, Trudy S. 1986. Greek Art and Persian Taste: Some Animal Sculptures from Persepolis. American Journal of Archaeology 90: 259–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keaveney, Arthur. 2003. The Life and Journey of Athenian Statesman Themistocles (524–460 B.C.?) as a Refugee in Persia. Lewiston, Queenston and Lampeter: Edwin Mellen Press. [Google Scholar]

- Kelekna, Pita. 2009. The Horse in Human History. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Kellens, Jean. 1974. Les Noms-Racines de l’Avesta. Wiesbaden: Dr. Ludwig Reichert Verlag. [Google Scholar]

- Kinnier-Wilson, James V. 1972. The Nimrud Wine Lists, A Study of Men and Administration at the Assyrian Capital in the Eighth Century B.C. London: British School of Archaeology in Iraq. [Google Scholar]

- Kuhrt, Amélie. 2007. The Persian Empire: A Corpus of Sources from the Achaemenid Period. London: Routledge, vol. 2. [Google Scholar]

- Lane-Fox, Robin. 1996. Ancient Hunting: From Homer to Polybius. In Human Landscapes in Classical Antiquity. Edited by Graham Shipley and John Salmon. London: Routledge, pp. 119–53. [Google Scholar]

- Levine, Marsha. 1999. The Origins of Horse Husbandry on the Eurasian Steppe. In Late Prehistoric Exploitation of the Eurasian Steppe. Edited by Marsha Levine, Yuri Rassamakin, Aleksandr Kislenko and Nataliya Tatarintseva. Cambridge: McDonald Institute for Archaeological Research, pp. 5–58. [Google Scholar]

- Linder, Rudi Paul. 1981. Nomadism, Horses and Huns. Past and Present 92: 3–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Littauer, Mary Aiken, and Joost H. Crouwel. 1979. Wheeled Vehicles and Ridden Animals in the Ancient Near East. Leiden: Brill. [Google Scholar]

- Llewellyn-Jones, Lloyd. 2013. King and Court in Ancient Persia. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Luckenbill, Daniel David. 1926. Ancient Records of Assyria and Babylonia. Chicago: Chicago University Press, vol. 1. [Google Scholar]

- Marcus, Michelle I. 1994. Dressed to Kill: Women and Pins in Early Iran. Oxford Art Journal 17: 3–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marr, John L. 1998. Plutarch: Life of Themistocles. Warminster: Aris & Phillips. [Google Scholar]

- Mayrhofer, Manfred. 1977. Zum Namengut des Avesta. Vienna: Verlag der Österreichischen Akademie der Wissenschaften. [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell, Terence C. 2000. The Persepolis Sculptures in the British Museum. Iran 38: 49–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moorey, Peter Roger Stuart. 1985. The Iranian Contribution to Achaemenid Material Culture. Iran 23: 21–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mossman, Judith M. 2010. A Life Unparalleled: Plutarch’s Artaxerxes. In Plutarch’s Lives: Parallelism and Purpose. Edited by Noreen Humble. Swansea: CPW, pp. 145–68. [Google Scholar]

- Muscarella, Oscar White. 1980. Excavated and Unexcavated Achaemenian Art. In Ancient Persia: The Art of an Empire. Edited by Denise Schmandt-Besserat. Malibu: Undena, pp. 23–42. [Google Scholar]

- Muscarella, Oscar White. 1988. Bronze and Iron: Ancient Near Eastern Artifacts in the Metropolitan Museum of Art. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art. [Google Scholar]

- Muscarella, Oscar White. 2004. The Hasanlu Lion Pins Again. In A View from the Highlands: Archaeological Studies in Honour of Charles Burney. Edited by Antonio Sagona. Leuven: Peeters, pp. 693–710. [Google Scholar]

- Palagia, Olga. 2000. Hephaestion’s Pyre and the Royal Hunt of Alexander. In Alexander the Great in Fact and Fiction. Edited by Albert Brian Bosworth and Elizabeth J. Baynham. Oxford: Oxford University Press, pp. 167–206. [Google Scholar]

- Pelling, Christopher Brendan Reginald. 2019. Herodotus and the Question Why. Austin: University of Texas Press. [Google Scholar]

- Porada, Edith. 1965. The Art of Ancient Iran: Pre-Islamic Cultures, rev. ed. New York: Greystone Press. [Google Scholar]

- Potts, Daniel T. 2005. Cyrus the Great and the Kingdom of Anshan. In Birth of the Persian Empire. Edited by Vesta Sarkhosh Curtis and Sarah Stewart. London: I. B. Tauris in association with The London Middle East Institute at SOAS and The British Museum, vol. 1, pp. 1–27. [Google Scholar]

- Potts, Daniel T. 2014. Nomadism in Iran: From Antiquity to the Modern Era. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Pritchard, James B. 1969. Ancient Near Eastern Texts Relating to the Old Testament, 3rd ed. Princeton: Princeton University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Radner, Karen. 2003. An Assyrian View on the Medes. In Continuity of Empire (?): Assyria, Media, Persia. Edited by Giovanni B. Lanfranchi, Michael Roaf and Robert Rollinger. Padova: Sargon Editrice e Libreria, pp. 37–64. [Google Scholar]

- Razmjou, Shahrokh. 2018. Propaganda and Symbolism: Representations of the Elamites at the Time of Ashurbanipal. In The Elamite World. Edited by Javier Álvarez-Mon, Gian Pietro Basello and Yasmina Wicks. London: Routledge, pp. 340–60. [Google Scholar]

- Reade, Julian E. 1998. Assyrian Sculpture, 2nd ed. London: The British Museum Press. [Google Scholar]

- Roaf, Michael. 1983. Sculptures and Sculptors at Persepolis. Iran 21: 1–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roaf, Michael. 1995. Media and Mesopotamia: History and Architecture. In Later Mesopotamia and Iran: Tribes and Empires, 1600–539 BC: Proceedings of a Seminar in Memory of Vladimir G. Lukonin. Edited by John E. Curtis. London: The British Museum Press, pp. 54–66. [Google Scholar]

- Root, Margaret Cool. 1979. The King and Kingship in Achaemenid Art. Leiden: Brill. [Google Scholar]

- Root, Margaret Cool. 2002. Animals in the Art of Ancient Iran. In A History of the Animal World in the Ancient Near East. Edited by Billie Jean Collins. Leiden: Brill, pp. 169–209. [Google Scholar]

- Sachs, Abraham J. 1953. The Late Assyrian Royal-Seal Type. Iraq 15: 167–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schleiermacher, Friedrich Daniel Ernst. 1836. Introductions to the Dialogues of Plato. Translated by William Dobson. Cambridge: Pitt Press. [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt, Erich F. 1953. Persepolis I: Structures, Reliefs, Inscriptions. Chicago: Chicago University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt, Erich F. 1957. Persepolis II: Contents of the Treasury and Other Discoveries. Chicago: Chicago University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt, Erich F. 1970. Persepolis III: The Royal Tombs and Other Monuments. Chicago: Chicago University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Schmitt, Rüdiger. 1988. Achaimenideninschriften in griechischer literarischer Überlieferung. In A Green Leaf: Festschrift for J.P. Asmussen (=Acta Iranica 28). Edited by Jacques Duchesne-Guillemin, Werner Sundermann and Fereydun Vahman. Leiden: Brill, pp. 17–38. [Google Scholar]

- Schoppa, Helmut. 1933. Die Darstellung der Perser in der Griechischen Kunst bis zum Beginn des Hellenismus. Coburg: Tageblatt-Haus. [Google Scholar]

- Seidl, Ursula. 1989. Die Babylonischen Kudurru-Reliefs. Fribourg and Göttingen: Universitätsverlag Freiburg Schweiz/Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht. [Google Scholar]

- Sekunda, Nicholas Victor. 2010. Changes in Achaemenid Royal Dress. In The World of Achaemenid Persia. History, Art and Society in Iran and the Ancient Near East. Edited by John E. Curtis and St John Simpson. London: I. B. Tauris, pp. 255–72. [Google Scholar]

- Sevinç, Nurten, Körpe Reyhan, Tombul Musa, Rose Charles Brian, Strahan Donna, Kiesewette Henrike, and Wallrodt John. 2001. A New Painted Graeco-Persian Sarcophagus from Çan. Studia Troica 11: 383–420. [Google Scholar]

- Seyer, Martin. 2007. Der Herrscher als Jäger. Untersuchungen zur Königlichen Jagd im Persischen und Makedonischen Reich vom 6.-4. Jahrhundert v. Chr. Sowie unter den Diadochen Alexanders des Großen. Vienna: Phoibos. [Google Scholar]

- Shahbazi, Alireza Shapour. 1978. New Aspects of Persepolitan Studies. Gymnasium 85: 487–500. [Google Scholar]

- Shorey, Paul. 1933. What Plato Said. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. [Google Scholar]

- Simpson, St John, Michael R. Cowell, and Susan La Niece. 2010. Achaemenid Silver, T.L. Jacks and the Mazanderan Connection. In The World of Achaemenid Persia, Proceedings of a Conference at the British Museum, September 29–October 1. Edited by John E. Curtis and St John Simpson. London and New York: I. B. Tauris, pp. 429–44. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, Nicholas D. 2004. Did Plato Write the “Alcibiades I?”. Apeiron 37: 93–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sparkes, Brian A. 1971. The Trojan Horse in Classical Art. Greece & Rome 18: 54–70. [Google Scholar]

- Starr, Ivan. 1990. Queries to the Sungod: Divination and Politics in Sargonid Assyria. Helsinki: Helsinki University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Strawn, Brent A. 2005. What Is Stronger than a Lion. Fribourg and Göttingen: Universitätsverlag Freiburg Schweiz/Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht. [Google Scholar]

- Stronach, David. 1978. Pasargadae. Oxford: Clarendon Press. [Google Scholar]

- Stronach, David. 1998. On the Date of the Oxus Gold Scabbard and Other Achaemenid Matters. Bulletin of the Asia Institute 12: 231–48. [Google Scholar]

- Stronach, David. 2009. Riding in Achaemenid Iran: New Perspectives. Eretz-Israel 29: 216–37. [Google Scholar]

- Stronach, David. 2011. A Pipes Player and a Lyre Player: Notes on Three Achaemenid or Near-Achaemenid Silver Rhyta Found in the Vicinity of Erebuni, Armenia. In Strings and Threads: A Celebration of the Work of Anne Draffkorn Kilmer. Edited by Wolfgang Heimpel and Gabriella Frantz-Szabó. Winona Lake: Eisenbrauns, pp. 251–74. [Google Scholar]

- Taqizadeh, Sayyed Hasan. 1938. Old Iranian Calendars. London: Royal Asiatic Society. [Google Scholar]

- Thompson, Georgina. 1965. Iranian Dress in the Achaemenian Period: Problems Concerning the Kandys and Other Garments. Iran 3: 121–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Treister, Mikhail Y. 2015. A Hoard of Silver Rhyta of the Achaemenid Circle from Erebuni. Ancient Civilizations from Scythia to Siberia 21: 23–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tuplin, Christopher J. 2010. All the King’s Horses. In Search of Achaemenid Persian Cavalry. In New Perspectives on Ancient Warfare. Edited by Garrett Fagan and Matthew Trundle. Leiden: Brill, pp. 100–182. [Google Scholar]

- Tuplin, Christopher J. 2014. The Arshama Letters from the Bodleian Library, Volume 3: Commentary. Available online: http://blogs.bodleian.ox.ac.uk/wp-content/uploads/sites/116/2013/10/Volume-3-Commentary-24.12.13.pdf (accessed on 9 May 2014).

- Walser, Gerold. 1966. Die Völkerschaften auf den Reliefs von Persepolis. Berlin: Mann. [Google Scholar]

- Watanabe, Chikako E. 1992. A Problem in the Libation Scene of Ashurbanipal. In Cult and Ritual in the Ancient Near East. Edited by His Imperial Highness Prince Takahito Mikasa. Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz, pp. 91–104. [Google Scholar]

- Watanabe, Chikako E. 2000. The Lion Metaphor in the Mesopotamian Royal Context. Topoi Supplement 2: 399–409. [Google Scholar]

- Watanabe, Chikako Esther. 2002. Animal Symbolism in Mesopotamia: A Contextual Approach. Vienna: Institut für Orientalistik der Universität Wien. [Google Scholar]

- Weissbach, Franz Heinrich. 1899. Choaspes (1). Realencyclopädie der Classischen Altertumswissenschaft 3: 2354–55. [Google Scholar]

- Weissert, Elnathan. 1997. Royal Hunt and Royal Triumph in a Prism Fragment of Ashurbanipal (82-5-22,2). In Assyria 1995. Proceedings of the 10th Anniversary Symposium of the Neo-Assyrian Text Corpus Project. Edited by Simo Parpola and Robert McCray Whiting. Helsinki: Helsinki University Press, pp. 339–58. [Google Scholar]

- Widengren, Geo. 1956. Some Remarks on Riding Costume and Articles of Dress among Iranian Peoples in Antiquity. Arctica: Studia Ethnographica Upsaliensia 11: 228–76. [Google Scholar]

- Wiesehöfer, Josef. 2001. Ancient Persia. Translated by Azizeh Azodi. London: I. B. Tauris. [Google Scholar]

- Wiseman, Donald J. 1952. A New Stela of Aššur-naṣir-pal II. Iraq 14: 24–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zarins, Juris. 1978. The Domesticated Equidae of Third Millennium B.C. Mesopotamia. Journal of Cuneiform Studies 30: 3–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Almagor, E. The Horse and the Lion in Achaemenid Persia: Representations of a Duality. Arts 2021, 10, 41. https://doi.org/10.3390/arts10030041

Almagor E. The Horse and the Lion in Achaemenid Persia: Representations of a Duality. Arts. 2021; 10(3):41. https://doi.org/10.3390/arts10030041

Chicago/Turabian StyleAlmagor, Eran. 2021. "The Horse and the Lion in Achaemenid Persia: Representations of a Duality" Arts 10, no. 3: 41. https://doi.org/10.3390/arts10030041

APA StyleAlmagor, E. (2021). The Horse and the Lion in Achaemenid Persia: Representations of a Duality. Arts, 10(3), 41. https://doi.org/10.3390/arts10030041