Abstract

In the 1970s, choreographer Lucinda Childs developed a reductive form of abstraction based on graphic representations of her dance material, walking, and a specific approach towards its embodiment. If her work has been described through the prism of minimalism, this case study on Calico Mingling (1973) proposes a different perspective. Based on newly available archival documents in Lucinda Childs’s papers, it traces how track drawing, the planimetric representation of path across the floor, intersected with minimalist aesthetics. On the other hand, it elucidates Childs’s distinctive use of literacy in order to embody abstraction. In this respect, the choreographer’s approach to both dance company and dance technique converge at different influences, in particular modernism and minimalism, two parallel histories which have been typically separated or opposed.

Keywords:

reading; abstraction; minimalism; technique; collaboration; embodiment; geometric abstraction; modernism 1. Introduction

On the 7 December 1973, at the Whitney Museum of American Art, four women performed Calico Mingling, the latest group piece by Lucinda Childs. The soles of white sneakers, belonging to Susan Brody, Judy Padow, Janice Paul and Childs, resonated on the wood floor of the Madison Avenue, building with a sustained tempo. A slightly athletic impulse drove their steps, each change of direction accompanied by a loose arm movement. For 15 min they repeated pathways in straight and curved lines, forward and backward, and intersected in an increasingly complex manner. Seated directly on the floor or on chairs, an audience of approximately 200 people delimited the 36-foot square area where the dancers performed.

Importantly, Calico Mingling was one of the first works that Childs choreographed for her own dance company. During the 1960s, the choreographer had developed most of her pieces for the Judson Dance Theater, a heterogenous group of dancers, musicians and visual artists who contributed collaboratively to one another’s works. Emancipating herself from what was originally designed as a workshop, in 1973 she formed a non-profit organization and, a few months later, bought a loft at 541 Broadway in New York’s SoHo neighborhood, where her dance studio would be located for the next 30 years. For the next decades, hiring professional dancers in order to rehearse, create, dance, and tour her pieces constituted the horizon of Childs’s imagining, dreaming, and developing her minimalist pieces.

The historical and practical significance of this turn, shifting from a community of fellows to professional dancers, has rarely been examined. Like Trisha Brown, Judith Dunn, or David Gordon, Lucinda Childs chose the company to organize her collaborative work with performers. This new framework introduced a split from her previous practice of dance—she choreographed mostly solos—as well as from members of the same generation who chose different modalities of organization.1 Embedded in a new social and material context (the company and the dance studio), Childs developed what could be described as a reductive form of abstraction based on a graphic representation of her dance material, walking, and a specific approach towards its embodiment. The argument presented here draws upon a cache of newly available archival documents in Lucinda Childs’ papers, donated in 2016 to the Centre national de la danse in Pantin.2

One typically applies the prism of minimalism when describing Childs’s pieces danced in silence. The community of visual artists, choreographers, directors, and composers of her generation, mostly working in New York City, attracted the attention of critics and historians who were likewise trying to capture Childs’ choreographic style of the 1970s.3 This article proposes a different perspective than what those previous efforts have yielded. It examines the intersection of track drawing, the planimetric representation of path across the floor, with minimalist aesthetics. Such a genealogy sheds light on the complex visual history of a form of representation associated with baroque dance and abstract expressionism. On the other hand, this article elucidates Childs’ distinctive use of literacy to embody abstraction in the framework of her company. Her approach resonates with that of Hanya Holm, the modern dance “pioneer” with whom the choreographer studied from 1955 to 1959. In this respect, Childs’ early minimalism sits at the crux of different tendencies of abstraction, which escape both the national frame of American minimalism, and the common split between modern and post-modern dance, where it has been usually confined.

2. A 40 Square Foot Dance

At the beginning of Calico Mingling, four dancers enter the performance area and line up horizontally in pairs, spaced about four feet apart. Forty square feet4 are required to perform the dance. This space corresponds to the extension of the four dance phrases of the piece: in depth, a straight and a semi-circular path of six steps; in width, one semi-circular path of six steps. Danced in unison on a steady pulse of six counts, Calico Mingling could be described as a fairly minimal march requiring tight spatial and temporal precision. In the first part of this essay, I will explore the relation of this piece to the different sites where it has been imagined, rehearsed, and performed. Departing from the casual and cool representation of the pedestrian, Childs’ quartet explores the architecture where the company worked for the first time. The company itself emerges as a tool of exploration, chiefly in the embodiment of choreography by her dancers and in the type of movement perception that this alternative space induces for the public.

In 1973, Childs remarked that “nothing is necessarily extraneous to dance, including the professionally trained dancer’s susceptibility to the influence of the movement of nonprofessionals” (Childs 1973, p. 51). By this statement, she distances herself from a certain representation of the ordinary by “professionally trained dancers” omnipresent in the discourse and works of critics and choreographers in and around the Judson Dance Theater.5 The performance of the newly formed company, filmed by Babette Mangolte a few months after the Concert of Dance at the Whitney Museum of American Art,6 did not emphasize the casual, prosaic, cool, and banal dimension of walking. It was a stringent piece, with Susan Brody, Nancy Fuller, Judy Padow, and Childs7 expressing the requisite concentration. With Calico Mingling, a point of emphasis emerges in the technical abilities of the professional dancers as applied to pedestrian movement. Maintaining the integrity of the geometric design involves a set of complex and discrete adjustments, such as balancing an individual step’s length in order to find a common standard, calibrating the centre and diameter of each circle in order to travel across the half of it in six steps, or equalizing the length of steps forward and backward, the latter being naturally shorter than the other.

These are not skills drawn from embodied knowledge formed in the process of professional training. They are developed in relation to choreographic demands that, for Calico Mingling, were new at the time. The company responds to the challenge of reductive abstraction by becoming an organizational strategy. For several years, Brody, Fuller, Padow, and Childs would be working together on a regular basis to adapt to a different choreographic horizon of expectations and to apply this geometry to movement.8 In this way, the company permits a sustained activity over time and increases the division of labor between the dancers, who perform the work, and the choreographer, who designs it. Combining the specific functions of each profession, the company allows for a technically organized cooperation required by Childs’ group dances from Calico Mingling onward.9

However, the spatial and rhythmical precision of the piece is not merely mechanical. On the contrary, Childs focuses on the minute adjustments made to complete the movement and exposes how a dancer’s postural individuality is supported by the choreographic material. Based on motion into space, the piece approaches walking as a motor action.10 While the choreography’s main focus is the progression of the body as a whole via weight transference, performers focus on adjusting their balance. Arms and shoulders swing symmetrically in opposition with the movement of the legs and spine forward and backward (Padow), emphasize the contralateral movement of the legs (Brody and Fuller), or give a slight momentum to each turn (Childs). Left unchoreographed, the upper body express dancers’ postural idiosyncrasy through their “shadows” and “pre-movements”.11 In this respect, Calico Mingling reconciles choreography and performance, structure and individuality, the company at once developing its repertory and the skills of its dancers. In 1968, the choreographer Yvonne Rainer compared “energy equality and ‘found’ movement” in performance, with the “factory fabrication” of minimalist sculptures (Rainer [1968] 1995, p. 263). I would argue that the steady pulse, pedestrian vocabulary, and geometric design of Calico Mingling operates, more, as a craftswomanship, which few artists claimed at the time.

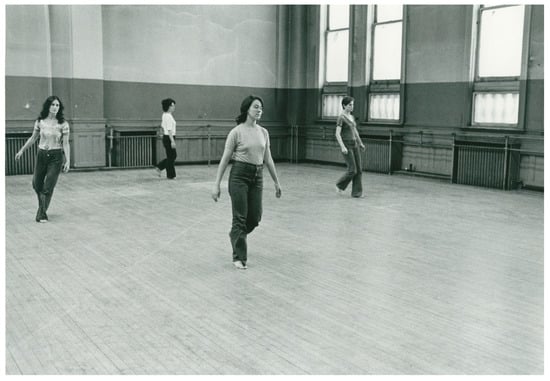

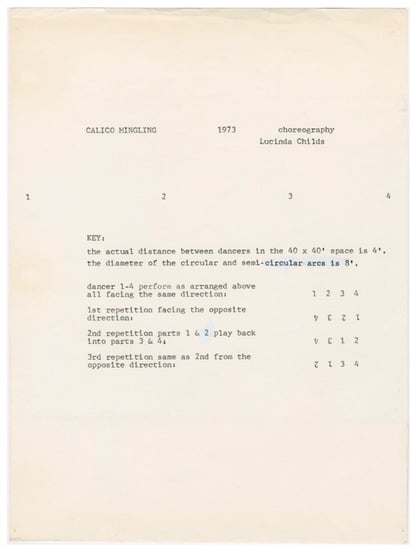

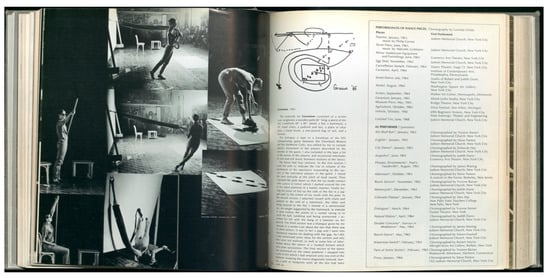

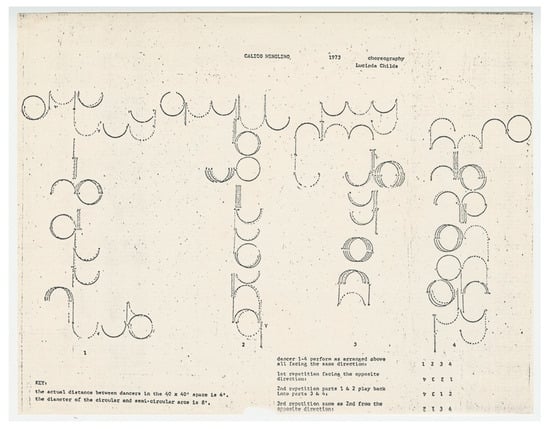

Primarily, the choreographer’s craft in Calico Mingling concerns the designing of paths. It involves a perception of space related to action—what can be done in the dance studio’s architecture with four dancers walking. The studio in which the piece was created and rehearsed, on the second floor of the Judson Memorial Church, measured approximately 36 by 59 feet (Figure 1). By the 1970s, the 36 foot square, situated on 541 Broadway, had become a downtown choreographic standard, which George Maciunas considers as the building “for the dancers” (Kostelanetz 2003, p. 78).12 In 1974, Frances Alenikoff, Trisha Brown, Lucinda Childs, David Gordon, and Valda Setterfield bought lofts in this steel structure industrial building—wider than the standard 25 foot buildings in SoHo—where they would subsequently live and work. The dimension of paths in Calico Mingling, as well as in Childs’ other pieces of the 1970s that are danced in silence, derive from this framework. In the quartet, the choreographic phrases of the piece are repeated at four reprises, with changing directions and places, according to a scheme (Figure 2). This “arrangement”13 of the dance material requires a specific design in order to fit into the room. Childs describes it as “splicing [the paths] to avoid the threat of obliteration through collision and yet remain as a piece within the confines of the same space” (Childs 1975, pp. 33–36). Calico Mingling’s composition revolves in a parameter formed by the changing distances between the dancers in motion within these 36 square feet. The staging of the piece in alternative spaces alludes to this transaction between the movement and the architecture. At the Witney Museum, the spectators stand or sit all around a 40 square foot square reproducing the dimension of the studio. Perception itself becomes more grounded and mobile when the audience is situated at the same level as the performers. The choreographer alludes to this new way of accommodating the audience and notices that “each member observes from his individual point of view” (Childs 1975, pp. 33–36). In this respect, Calico Mingling maps out the contours of a new ecology of attention where the choreography, the architecture, and the performance of the piece overlap.

Figure 1.

Babette Mangolte, Calico Mingling (1973), with Susan Brody, Lucinda Childs, Janice Paul, and Judy Padow at The Judson Memorial Church, New York, gelatine silver print, 7.8” × 9.9”, Fonds Lucinda Childs—Médiathèque du Centre national de la danse © 1973 Babette Mangolte, all rights of reproduction reserved.

Figure 2.

Lucinda Childs, Compositional chart for Calico Mingling (1973), typescript, 14” × 8.5”, Fonds Lucinda Childs—Médiathèque du Centre national de la danse.

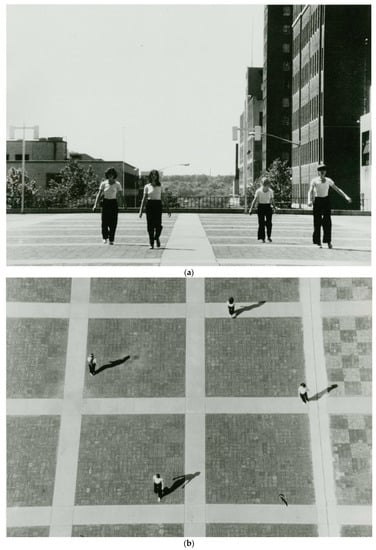

The semi-public studio is the place where dances are rehearsed and, eventually, performed. When muscular and rhythmical memory is embodied, its topography could be installed almost anywhere through a series of discrete landmarks.14 Babette Mangolte’s film of the piece, shot at Robert Moses Plaza at Fordham University in Manhattan, exemplifies this relation of the dance to the site where it is performed.15 It alternates a wide shot featuring the four dancers performing the dance (Figure 3a) and a bird’s-eye view showing the paths across the floor (Figure 3b). The topographic dimension of Calico Mingling is emphasized by the design of the square itself, a grid made of concrete. Instead of diving immediately into the semiotics of this pattern, one should pay attention to how the floor was used by the company in order to dance. In a lecture given in 2014, Lucinda Childs addressed this question (Childs et al. 2014), emphasizing that its serial structure provided regular landmarks that allowed the dancers to measure their positions and paths. The abstract formalism of the pattern was transformed through body measurements into an area for dancing, and provided stable points of reference on which dancers could rely during the dance. Childs’ remark focuses attention on the operation she had actually been doing: choreographing and rehearsing the piece with her company in a dance studio and then implementing it on a site chosen together with Babette Mangolte—embodying first and placing oneself later. In this respect, paths are the enduring reality of her work, and the grid only facilitates their set up.

Figure 3.

(a,b) Babette Mangolte, Calico Mingling (1973), with Susan Brody, Lucinda Childs, Nancy Fuller, and Judy Padow at The Robert Moses Plaza, Fordham University, Manhattan, New York, 1974, gelatine silver print, 7.8” × 9.9”, Fonds Lucinda Childs—Médiathèque du Centre national de la danse © 1973 Babette Mangolte, all rights of reproduction reserved.

Until the recent recreation of the piece,16 the 16 mm film was one of the rare documents of Childs’s first quartet. While the company has restaged several pieces of the 1970s, Calico Mingling’s main vehicle remained the film. Childs’ and Mangolte’s collaboration directly questioned the possibility of touring, inconceivable in 1974 for a Downtown company.17 In its montage and sound mixing, it balances in a unique way the distant—topography, ambient sound of the road traffic, siren calls, singing of a bird, and children’s voices—with the close—shadow and pre-movement of the performers, actual shadow of their silhouette on the floor, and echoes of their footsteps on the ground. This dialectic alludes to what it means to tour, i.e., to bring an audience close to dance pieces produced far away. The film not only offered the possibility to show the dance in theatres and museums when the company could not travel, but also induced the spatial dynamic that binds together the embodied memory of a dance company and a site.

3. From Floor Plan to Path

Lucinda Childs claimed on many occasions that “there is no such thing as Lucinda Childs’ technique.”18 Even if this assumption can be questioned, she stresses a major shift in her approach to dance. In the United States, the second generation of modern choreographers in the 1920s and 1930s considered dance techniques as the core of dance practices. Their respective exercises and studies, through which dancers would master bodily movement, were considered their syllabus. In 1973, Childs proposed that dance could be created by other means, and Calico Mingling was the site of her first intent to test this proposition. I will argue that writing, drawing, and reading challenged the centrality of techniques in her studio work, proposing another path toward embodying movement.

In 1973, Lucinda Childs organized her dances using mostly floor plans. The floor plan has a longstanding connection to dance notation, dating back to the XVIIth and XVIIIth centuries with Pierre Beauchamp’s and Raoul-Auger Feuillet’s influential scoring systems.19 The ballet masters of the Baroque and Classical era subjected paths to a refined semiotics and terminology. The “floor plan” or “track drawing”, i.e., the graphic representation or map, echoed the “floor pattern”, the drawing or trace made by the dancer’s feet on the floor, while the actual movement of the dancer’s body in space was called “the path.” In a series of typical baroque resonance, scoring dance and dancing were assimilated through the paradigm of the designo, which had metaphysical significance.20

Floors plans appear at several occasions during the development of modern dance, garnering critical remarks. In a specific account, John Martin reproached its flatness (Martin [1933] 1989, pp. 52–55). Using a typical modernist argument, he maintained that track drawing did not take in account the specificity of dance’s spatiality, which is simultaneously “horizontal” and “vertical”. How would one score a jump if there is no way to indicate height, for example? His polemic argument echoed the emphasis of weight, the verticality of the plumb line, as a major factor of movement in modern notation systems.21 For this reason and to this day, perspectives of positivist history still dismiss track drawing as a means of dance literacy and argue instead for more proficient systems for scoring movement.22 Instead, I propose to approach floor plans as an historically situated representation of human movement.

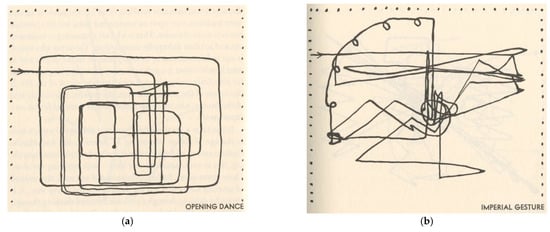

In spite of this critical prejudice against floor plans as generative tools or recording devices, Arch Lauterer promoted their use as the architect, scenographer, light designer, festival director, and pedagogue who collaborated with Graham, Humphrey, Holm, and Weidman. His approach to track drawing had a fundamental influence on the development of Lucinda Childs’ graphic technique. In order to design sets and lighting, Lauterer drew floor plans to map the area where dancers moved and analyzed the directional force of the pieces (Figure 4). Positioned between the field of dance and architecture, he valued the reduction of movement to one single dimension suitable to his specific need. Published in Martha Graham, The early years (Armitage [1937] 1985), his method was briefly presented by the critic Edith J.R. Isaacs:

Figure 4.

Arch Lauterer, floor plan for (a) Opening Dance (1937) and (b) Imperial Gesture (1937) of Martha Graham, black and white print, 2”× 2”, in (Armitage [1937] 1985, pp. 42–43).

Up at Bennington on the open floor of the Armory […], Arch Lauterer this summer followed the lines of some of Martha Graham’s best-known dances and of the newest dance, “Immediate Tragedy”. The sketches were made in half darkness and while Mr. Lauterer was watching the dance, without the opportunity to check his line against the dancer’s movement. Yet even in this way, they make a portrait both of the dancer and the dance that is clear and free and modern. They point the way ahead.(Armitage [1937] 1985, p. 48)

Within his floor plans, Lauterer captured a hidden dimension of the dances without seeing what he was doing, led only by the tactile stimuli of the pen on the paper. Isaacs describes these sketches as “portraits” and not maps, plans, or even landscapes. They represent something other than composition—the means by which dance organizes in space and time—since “[he didn’t have] the opportunity to check his line against the dancer’s movement”. They partake of a new sensibility, one that spans from automatic writing to drippings, and considers inscriptions as processes of the unconscious.23 Like a psychic medium, Lauterer “follows the lines […] in half darkness”. His track drawings do not represent space as a principle of regulation, but as matter where the distance between objects is consumed and absorbed. The mingled, thick black line renders “ecstasy”, the abstract configuration of energy and space as experienced by the dancer and the spectator.24

In 1973, Lucinda Childs published her first article dedicated to her work, in Artforum (Figure 5), borrowing practices of the floor plan to represent her previous solos at the Judson Dance Theater. Her encounter with the light designer’s ideas reaches back to 1961–1963 when she studied at Sarah Lawrence College. Lauterer had directed the theatre department of Sarah Lawrence from 1943 to 1945, and had a close relationship with Bessie Schönberg, who led the dance department for almost forty years; both worked with the Graham Company where Schönberg danced between 1927 and 1931 after arriving from Germany. Obviously, Martha Graham, The early years was included in the syllabus, and Lucinda Childs read the book as part of her curriculum.25 Like Lauterer, Childs’s first drawings published in Artforum do not specify scale. They offer a global view of movement in space and a sense of the dancer’s path. In the final layout, they are associated with photographic documentation by Peter Moore and Hans Namuth. The immediate though imprecise sense of location and visualization provided by the article lies in the back and forth between photographs and drawings. The photographs depict the space in which the dance was originally performed as well as some elements on the choreographic material, while the free hand sketches hinge on the irregular courses of the performer. The floor plans are less concerned with accuracy than with a kinaesthetic experience of walking. Childs would rapidly deviate from this subjective approach of pictoriality; however, she retains a decisive lesson from Lauterer: Track drawing provides a different vision of a piece and recasts perception.

Figure 5.

(Childs 1973, pp. 54–55), black and white print, 10.6” × 10.6” © Artforum.

We can follow the influence of Lauterer’s approach to space in Calico Mingling, which premiered in December 1973. The dance is based on a floor plan photocopied in multiples (Figure 6). It represents the phrases performed by each dancer in four separate columns. In these documents, tools such as rulers, squares, templates, and compasses supplement the free-hand drawing. Information is added in the margins, including title and scale, that gives the drawing a technical aspect seemingly in line with the minimalist aesthetic. The article in Artforum and the document made for the company propose very different reading experiences. While “A Portfolio” depicted the path as a continuous line, Calico Mingling’s floor plan tracks movement through a series of discontinuous lines adjacent or superposed. Created for the internal use of the company, this new convention makes deciphering difficult for an ordinary reader. One wonders where the movement starts and what directions it follows. Meanwhile, the social reality in and for which it was made—the studio practice of the dance company at the beginning of the 1970s—has dramatically evolved.26 Facing the difficulty of examining these inscriptions as part of a specific and situated dance and choreographic process, I adopted a multidisciplinary approach where literacy studies and anthropology supplement art history: material analysis of the documents combined with participant observation and interviews with the dancers and the choreographer.

Figure 6.

Lucinda Childs, reduction for Calico Mingling (1973), photocopy, 8.5” × 11”, Fonds Lucinda Childs-Médiathèque du Centre national de la danse.

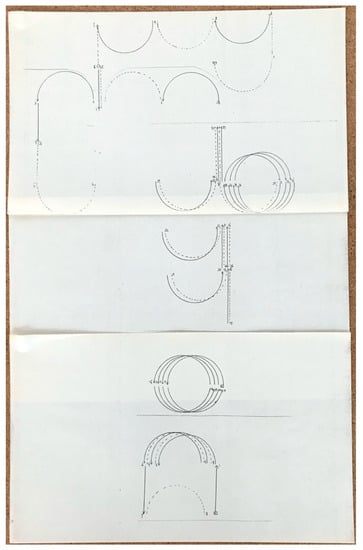

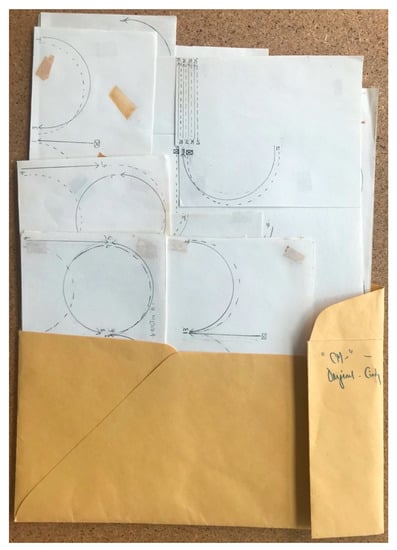

In the company vernacular, this floor plan was called a “reduction.” It was created by miniaturizing the “master” drawing (Figure 7)—which comprised four large strips, each one 10.5 inches long, representing each dancer’s path—with the use of a Xerox photocopier. The surviving documents, carefully archived by the choreographer in the creation folder dedicated to the piece, allow us to reconstitute the seven stages through which the master was reformatted. First, the different patterns were traced with graphite on 26 cut outs (Figure 8). Photocopied, pasted on sheets of legal format paper, and photocopied again, each dancer’s floor plan was then spread across three pages (Figure 7). The floor plans were reduced twice and assembled in a final layout (Figure 6).

Figure 7.

Lucinda Childs, master score for dancer 3, Calico Mingling (1973), photocopy, 10.5” × 10½”, Fonds Lucinda Childs—Médiathèque du Centre national de la danse.

Figure 8.

Lucinda Childs, cut-outs for Calico Mingling (1973), graphite on paper, 12.7” × 9” × 0.1”, Fonds Lucinda Childs—Médiathèque du Centre national de la danse.

From this description, it is clear that Childs invested a great deal of energy in making this artefact, which the performers were expected to dance with, literally. The floor plan, with a path divided into 40 segments, is represented from the performer’s point of view. He/she is meant to follow it, holding the master or its reduction in hand, walking from each point to the next, in six steps, in unison, with the other performers. Once we recognize this orientation to the dancer’s experience, we can begin to understand its seemingly illegible abstract elements. For example, continuous lines represent the direction forward and broken lines backward. Every segment of the floor plan corresponds to a measure of six beats. The dance phrase is organised in five sections of eight measures. Each section is separated from the other and placed arbitrarily one on top of the other. In this respect, the vertical layout does not represent a spatial continuity but a succession. To visualize the path, one should be physically walking in the studio; at the end of each section (measures 8, 16, 24, 32, and 40), his/her eyes go to the next section situated above and continue reading and dancing from his/her previous position. A little check box at the beginning of each section facilitates the reading.27 A similar spatial distortion appears in the path of the performers. Juxtaposed on the paper, they get closer or deviate, and those spatial dynamics are not rendered on the map.

The contents of Calico Mingling’s creation folder invite us to reconsider what we usually understand as a “score”, “reading”, and “dancing”. “Reading” does not match with the common representation of the practice—a relaxed, abandoned, or neutralized body sitting or lying. Instead, dancers should be physically walking while looking at the page. The floor plan does not show a general image of the dance that could be contemplated but a processual experience where the body follows the instruction and enters progressively into the dance. Most importantly, in the final reduction (Figure 6), the numbers associated with the floor plan’s master have shrunk to such a degree that they have become unreadable. This disappearance testifies that the document’s being made to work with the dancer’s memory, as the dancer already knew part of the dance phrase. The reduction provided an overhead view that complimented their muscular memory. Dance studies tend to oppose “dancer’s memory” and “scores” or “archives”.28 Our survey indicates the opposite by focusing on the professional culture of the company, which made possible the embodiment of Calico Mingling. Rehearsing the piece in the Lucinda Childs’ Company involved a distributed system of representations29, including the internal memory of the dancers, the reduction they held in their hands (Figure 6), and the master (Figure 7) (which is too big to dance with) left on the floor. It is the coordination of these external and internal representations that facilitated the course of rehearsals.

A final aspect of the Lucinda Childs Dance Company’s literacy should be highlighted. The reduction has been described until now as an aid for dancers’ memorization, as challenged by repetition and the variation of similar patterns and phrases. However, reading participates in Calico Mingling’s embodiment in a more subtle way. It helped acclimate the dancers technically through a honing of skill. Working with a reduction, a trained dancer can be simultaneously “in” and “out” of the page. This double focus creates a specific state of awareness, which is exemplified in the film of Babette Mangolte. Dancers are simultaneously fully physically present and mentally engaged in the process of counting. If their enduring energy could be compared with other choreographic approaches of the time, such as Yvonne Rainer’s “neutral doer” (Rainer [1968] 1995, p. 270), I would argue that in Childs’ work, it is manifest in the way her piece was incorporated. Dancers’ movements were shaped by the system they rehearsed with. Providing a set of floor plans as a resource for action to facilitate the course of the work, Childs founded a technique—not a codified movement vocabulary, but a method to practice and perform movement.

4. Tecknik and Techniques

Beyond the works of a choreographer, a dance company is a social reality, one made by dancers, their habits, skills, and techniques, that allows the group to put itself into motion. Our survey of Lucinda Childs’ archives demonstrates how literacy plays a distinctive role not only in the composition of a piece (the choreographer’s craft), but in the embodiment of the dance. In the final section of this paper, I will historicize the literacy of Childs’s company, specifically as marked by the approaches of choreographer Hanya Holm, and more broadly by other dance artists of the German diaspora, in 1930s New York.

Lucinda Childs’ frequent use of scores with her company demonstrates the influence of a model of studio work that the choreographer learned from her training with Hanya Holm between 1955 and 1961. In 1930, Mary Wigman tasked Holm with opening a school in New York following Wigman’s highly successful first United States tour. Because of allegations of Wigman’s association with the government of the Third Reich in 1936, the Wigman School was renamed after Holm.30 Holm taught in New York until 1983; her studio was part of an active German diaspora operating in the city, together with Irmgard Bartenieff, Franziska Boas, Irma Otte-Betz, and Bessie Schönberg, among others.31 It was at Holm’s studio where Labanotation, the dance notation system, developed from the 1920s by the Austro-Hungarian choreographer Rudolf Laban, was Americanized. In 1939, Helen Priest, Eve Gentry, Janey Price, and Ann Hutchinson Guest began to teach this system of movement notation in Holm’s studio.32 From 1940 onward, their approach was promoted and disseminated through the Dance Notation Bureau (DNB), a non-profit organization based in New York City that teaches kinetography and preserves choreographic works through Labanotation.33

When Childs entered Holm’s school as a teenager, Labanotation as such was not taught, but a Wigmano-Labanian approach to movement deeply influenced the curriculum.34 Occasionally, during class, dancers would individually decipher movements using scores or cut-outs. Typically, kinetography uses the dancer’s body as the point of reference so that he/she can read and move with the score in his/her hands. The timeline is arranged vertically on the page and read from bottom to top; this layout is quite unusual, especially in dance literacy. Importantly, this approach mirrors the one that Childs employed in creating the reduction and master of Calico Mingling. While her use of signs is totally different from Labanotation,35 she retained the way it oriented the dancer’s body with the score in her hands, as well as the letter format of the paper; the cut-outs that allow their manipulation; and the time flow organised vertically on the page, which appears as a palimpsest in Child’s reduction for Calico Mingling.

Childs’ unusual position regarding dance techniques also resonates with a distinguishing feature of Holm’s teaching. In the Weimar Republic, Technik was a method for experiencing and structuring movement.36 During class, students worked with analytical concepts such as body directions, levels, or transferences of weight.37 On the contrary, in Ballet and American Modern Dance Companies, students exercised through codified movement vocabularies. Childs’ assumption of not having a “technique” echoes how Americans perceived Ausdruckstanz (expressionist dance). While Childs did not develop a syllabus and approached an increasingly large range of styles—from pedestrian to classical and baroque—she relied on a Technik to analyze, submit, and embody those vocabularies, and this was literacy. If her eclecticism has been described through the lens of postmodernism,38 I would rather situate it at the intersection of modernism and American postmodern dance.

Lucinda Childs’ first quartet stands at the crux of two parallel histories, which have been either separated or opposed.39 From the one side, her graphic technique corresponds to repetition, seriality, and modularity—methods that American minimalism developed during the 1960s and 1970s. This well-known narrative explains distinguishing features of her work, and corresponds with the network of artists, composers, and directors with whom she collaborated at the time. However, it proves helpless when one tries to understand how her dance company actually worked in order to embody reductive abstraction. Investigating dance literacy reveals a complementary narrative revolving around Holm and the German diaspora. I would argue that there is much to gain by accounting for this complexity and acknowledging the diverse influences that shaped her as an artist throughout the years.40 Instead of imagining her trapped in between two narratives (modernism and postmodernism), we could regard Childs’ work from the longstanding development of modern dance as a bridge between different generations and areas. While the historiography spanning the 1930s to the 1990s, written in the context of the World War II and Cold War, insisted on national frames, movements, and tendencies, the current situation invites us to revise the canon, and reveal the tensions of her work. I would advocate for taking this risk.

Funding

This research was funded by the Ph.D. Fellowship of the Institut National d’Histoire de l’Art (INHA), and the Aides à la mobilité Aires Culturelles 2018 of the École des hautes études en sciences sociales (EHESS).

Acknowledgments

My profound thanks to the editor of this Special Issue, Juliet Below and Elise Archias, and the anonymous peer-reviewers. The ideas developed in this article have been presented during the 108th College Art Association Annual Conference in the panel “Dancing in the Archives: Choreographer’s drawings as resources for the art historians (19th-20th centuries)” chaired by Pauline Chevalier (INHA). They’ve benefited from the exchanges with my PhD supervisor Béatrice Fraenkel (EHESS), and co-supervisor, Carrie Lambert-Beatty (Harvard University), from the teaching of Noëlle Simonet in kinetography Laban at the Conservatoire National Supérieur de Musique et de Danse de Paris, and from the research program “Chorégraphie. Écriture et dessin, signe et image dans les processus de creation et de transmission chorégraphique (XVe-XXIe siècle)” at the INHA. My knowledge of Lucinda Childs’ archives has been made possible through the generosity and time of the choreographer who hosted me at Martha’s Vineyard (Massachusetts), from the department Heritage, Audio-Visual and Publishing of the Centre national de la danse, notably Juliette Riandey and Laurent Sebillotte, from dancer Ruth Childs, and former members of the dance company, in particular Ty Boomershine.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

References

- Armitage, Merle. 1985. Martha Graham: The Early Years. New York: Da Capo. First published 1937. [Google Scholar]

- Audinet, Gérard, and Jérôme Godeau. 2012. Entrée des Médiums: Spiritisme et art d’Hugo à Breton. Paris: Paris-Musées. [Google Scholar]

- Auslander, Philip. 1999. Liveness: Performance in a Mediatized Culture. New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Banes, Sally. 2011. Terpsichore in Sneakers: Post-Modern Dance. Middletown: Wesleyan University Press. First published 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Banes, Sally, and Susan Manning. 1989. Terpsichore in Combat Boots. TDR: The Drama Review 33: 13–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bochner, Mel. 1995. Serial Art, Systems, Solipsism. In Minimal Art, A Critical Anthology, 1995th ed. Edited by Gregory Battcock. New York: Dutton, pp. 92–102. First published 1967. [Google Scholar]

- Burt, Ramsey. 2006. Judson Dance Theater. Performative Traces. London and New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Caroso, Fabritio. 1986. Courtly Dance of the Renaissance. A New Translation and Edition of the Nobilita di Dame (1600). Edited by Julia Sutton. Toronto: Dove Edition. First published 1600. [Google Scholar]

- Childs, Lucinda. 1973. Lucinda Childs: A Portfolio. Artforum 11: 50–56. [Google Scholar]

- Childs, Lucinda. 1975. Notes ’64-’74. TDR: The Drama Review 19: 33–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Childs, Lucinda, Elisabeth Lebovici, Natasa Petrešin-Bachelez, and Patricia Falguières. 2014. Lucinda Childs. Ph.D. dissertation, School for Advanced Studies in the Social Sciences, Paris, France. [Google Scholar]

- Franko, Mark. 2015. Dance as text: Ideologies of the Baroque Body. Oxford: Oxford University Press. First published 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Franko, Mark. 1995. Dancing Modernism/Performing Politics. Bloomington and Indianapolis: Indiana University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Gentry, Eve. 1992. The “Original” Hanya Holm Company. Edited by Robert P. Cohan. Choreography and Dance 2: 9–40. [Google Scholar]

- Glon, Marie. 2014. Les Lumières Chorégraphiques: Les Maîtres de Danse Européens au Coeur d’un Phénomène Éditorial (1700–1760). Ph. D. thesis, Histoire et civilisations, École des Hautes Etudes en Sciences Sociales, Paris, France. [Google Scholar]

- Glissant, Édouard. 1990. Philosophie de la Relation. Paris: Éditions Gallimard. [Google Scholar]

- Godard, Hubert. 2002. Le geste et sa perception. In La Danse au XXe Siècle. Edited by Isabelle Ginot and Marcelle Michel. Paris: Larousse, pp. 236–41. [Google Scholar]

- Goodwin, Charles. 1994. Professional Vision. American Anthropologist 96: 606–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodwin, Charles. 2018. Co-Operative Action. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Goody, Jack. 1977. The Domestication of the Savage Mind. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Hutchins, Edwin. 1995. How a Cockpit Remembers Its Speeds. Cognitive Science 19: 265–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hutchins, Edwin. 1996. Cognition in the Wild. Cambridge: MIT Press. [Google Scholar]

- Hutchinson Guest, Ann. 1989. Choreo-Graphics: A Comparison of Dance Notation Systems from the Fifteenth Century to the Present. New York: Gordon & Breach. [Google Scholar]

- Kiss, Dora. 2016. Saisir le Mouvement: Écrire et lire les Sources de la Belle Danse (1700–1797). Paris: Classiques Garnier. [Google Scholar]

- Kostelanetz, Richard. 2003. SoHo: The Rise and Fall of an Artists’ Colony. New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Laban, Rudolf. 1950. The Mastery of Movement, 4th ed.Revised by Lisa Ullmann. Alton: Dance Books Ltd. [Google Scholar]

- Lamarra Graham, Amanda Jane. 2014. The Myth of Movement: Lucinda Childs and Trisha Brown Dancing on the New York City Grid, 1970–1980. Ph.D. dissertation, University of Rochester, New York, NY, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Lambert-Beatty, Carrie. 2008. Being Watched: Yvonne Rainer and the 1960′s. Boston: MIT Press. [Google Scholar]

- Latour, Bruno, and Steve Woolgar. 1979. Laboratory Life: The Social Construction of Scientific Facts. Beverly Hills: Sage Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Lista, Marcella, and Liz Kotz. 2017. Minimalismes. A Different Way to Move. Berlin: Hatje Cantz. [Google Scholar]

- Lu, Mei-Chen. 2009. The Dance Notation Bureau. Dance Chronicle 32: 291–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manning, Susan. 1993. Ecstasy and the Demon: Feminism and Nationalism in the Dances of Mary Wigman. Los Angeles: University of California Press. [Google Scholar]

- Martin, John. 1989. The Modern Dance. Princeton: Princeton Book Company, Publishers. First published 1933. [Google Scholar]

- Partsch-Bergsohn, Isa. 1994. Modern Dance in Germany and the United States: Crosscurrents and Influences. Chur: Harwood Academic Publishers. [Google Scholar]

- Phelan, Peggy. 1993. Unmarked: The Politics of Performance. New York: Psychology Press. [Google Scholar]

- Phillips, Victoria. 2020. Martha Graham’s Cold War. The Dance of American Diplomacy. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Pouillaude, Frédéric. 2009. Le Désoeuvrement Chorégraphique. Paris: Vrin. [Google Scholar]

- Rainer, Yvonne. 1995. A Quasi-Survey of Some Minimalist Tendencies in the Quantitatively Minimal Dance Activity Midst the Plethora, or an Analysis of Trio A. In Minimal Art, A Critical Anthology, 1995th ed. Edited by Gregory Battcock. New York: Dutton, pp. 263–73. First published 1968. [Google Scholar]

- Rondeau, Corinne. 2013. Lucinda Childs. Temps/Danse. Pantin: Centre national de la danse. [Google Scholar]

- Schang, Augustin. 2017. 537 Broadway: Performance and Building. Performance Art Journal 39: 53–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sorell, Walter. 1969. Hanya Holm: The Biography of an Artist. Middletown: Wesleyan University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Van Imschoot, Myriam. 2005. Rests in Piece: On Scores, Notation, and the Trace in Dance. Multititudes. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| 1 | The 1970s correspond to seminal projects such as the dance collective Grand Union (Yvonne Rainer, Becky Arnold, Douglas Dunn, David Gordon, Barbara Dilley, Steve Paxton, among others), or Contact Improvisation, a technique led by anarchist ideals, and organised in a radically decentralised manner by a network of practitioners (Steve Paxton, Nancy Stark Smith, Lisa Nelson, among others) and its magazine, Contact Quarterly. |

| 2 | Fonds Lucinda Childs—Médiathèque du Centre national de la danse, call number: 11 CHIL 1/1-8—25 CHIL/1513. The archive includes two mains subcategories: 1. The Personal Papers: Folders with notes, drawings, and inscriptions of various sorts developed for choreographic pieces and collaborations, photographs, films, posters, and clippings. 2. The Lucinda Childs Dance Company archives: Administrative material related to the Company productions and touring, as well as Childs’ freelance projects with ballets, theatre, opera, and film. More information and an inventory are provided by the Centre national de la danse: http://inventaire.cnd.fr/archives-en-ligne/ead.html?id=CND_CHIL&c=CND_CHIL_e0000018 (accessed on 19 November 2020). |

| 3 | See (Burt 2006, pp. 52–87), (Lista and Kotz 2017, pp. 158–93), (Rondeau 2013), and (Lamarra Graham 2014, pp. 87–143). Even if there is much to write in order to precisely describe the relationships and discussions that Childs develops with artists, composers, and choreographers in the frame of what is usually called “minimalism”, we will not touch this question in this article. |

| 4 | The 40 square foot dimension is specified in several documents related to Calico Mingling. In (Childs 1975, pp. 33–36), the choreographer mentions that “the audience is seated on all sides of thirty-six by forty-foot square space”, which indicates that the dimension could be marginally adapted depending the site where the piece was performed. |

| 5 | Task based performances have attracted most of the attention of critics and scholars in the discussion about the Judson Dance Theater. Among the most recent and thorough analysis, Ramsey Burt proposes a general semiotics of the “allegories of the ordinary”, granting dancers “through their refusal to normative aesthetics expectations, […] to create a context in which embodied experiences could become a site of resistance” (Burt 2006, p. 21). Carrie Lambert-Beatty proposes instead an anthropological approach of this compositional technic, less attentive to normativity and transgression than long term historical change upon perception of time (Lambert-Beatty 2008, pp. 93–98). However, both historians share a similar chronology, ranging from 1961 to 1970, and the centrality of Steve Paxton’s and Yvonne Rainer’s works. Since Lucinda Childs never used this compositional technic, her work remains marginal in the historiography of the period. Burt and Lambert-Beatty, as Banes before them, have a difficulty to address the stakes of the next decades, guided by a teleological narrative culminating during the late 1960s with the politization of what they approached as the core of the Judson Dance Theater. Our investigation proposes a series of shifts—from dance pieces to company labour, from semiotics to crafts—in order to write a different narrative and revisit this crucial moment of post-World War II American dance history. |

| 6 | Childs and Mangolte remember that the shooting took place a couple of months after the performance at the Witney Museum. I have not found any evidence of the exact date of the shooting. |

| 7 | For the shooting, Nancy Fuller replaced Janice Paul who performed at the Witney Museum; she subsequently worked for the company until 1976. |

| 8 | Padow remained in the company until 1978, Brody and Fuller until 1976. |

| 9 | At the opposite end, the Judson Dance Theater social organization was characterized by affinities, interdisciplinarity, and a low level of technicality influenced by the deskilling avant-garde strategy of John Cage. |

| 10 | It could have been choreographed as a gesture of the legs and stylised as such. |

| 11 | Rudolf Laban labels as “shadow movements”, “the tiny muscular movements such as the raising of the brow, the jerking of the hand or the tapping of the foot, which have none other than expressive value. They are usually done unconsciously and often accompany movement of purposeful action” (Laban 1950, pp. 10–11). The “pré-mouvement” is described by Hubert Godard as “an attitude towards weight and gravity before one actually moves, on the only fact of standing. The expressive value of the movement will be produced by it” (Godard 2002, p. 237, tr. by the author). |

| 12 | For an account on 537–541 Broadway Cooperative created by George Maciunas, see (Kostelanetz 2003, pp. 78–84) and (Schang 2017). |

| 13 | Childs explicitly borrows the minimalist vocabulary to describe the organization of space in Calico Mingling. “Arrangement” was opposed to “composition” by the visual artist Mel Bochner to assert the difference between minimalism and modernism. “The word ‘arrangement’ is preferable to ‘composition’. ‘Composition’ usually means the adjustment of the parts, i.e., their size, shape, color, or placement, to arrive at the finished work, whose exact nature is not known beforehand [as Morandi’s bottles or De Kooning’s women]. ‘Arrangement’ implies the fixed nature of the parts and a preconceived notion of the whole [as in Sol LeWitt’s structures]” (Bochner [1967] 1995, p. 100). In this respect, one can understand why Childs insists that in Calico Mingling “each phrase regardless of the reordering in space, is repeated exactly in each situation” (Childs 1975). |

| 14 | The principle of the landmarks was experimented for the first time in Street Dance (1964). Childs pointed out architectural features and details on signposts or the sidewalk too small for the audience to see. |

| 15 | For an historical account on the construction of the square see (Lamarra Graham 2014, pp. 87–90). |

| 16 | In September 2017 at the Batie Festival, Geneva, Calico Mingling was recreated by Ruth Childs assisted by Ty Boomershine. The piece was danced by Ruth Childs, Anne Delahaye, Anja Schmidt, Pauline Wassermann, and Stéphanie Bayle. |

| 17 | Until the 1970s, most of the international tours were organised under the guidance of the State Department, such as the Merce Cunningham Dance Company international tour of 1963–1964 or the numerous tours of the Martha Graham Dance Company as explored by Victoria Phillips in her recent Martha Graham’s Cold War: The Dance of American Diplomacy (Phillips 2020). Dance pieces were branded under the label “modern dance” in the frame of Cold War propaganda, an implausible designation for Downtown companies, which in turn foreclosed possibilities of touring. However, touring in Western Europe increased over the following decade through a new emerging network of theatres, dance festivals, and biennales. The Lucinda Childs Dance Company toured internationally from 1978 onward, and Dance was its first international production for theatre. |

| 18 | Discussion with the author during summer 2015 and statement reported by the former dancer of the company Ty Boomershine in November 2019. |

| 19 | See the recent research on this system and its use (Glon 2014; Kiss 2016). |

| 20 | The development of track drawing in the late Renaissance is bound to Neo-Platonism. Body movements mirror the dance of all celestial bodies to the music of spheres. See, among others, the introduction of Julia Sutton to Fabritio Caroso, Nobilità di Dame, (Caroso [1600] 1986) and the political background provided by (Franko [1987] 2015). |

| 21 | For instance, Rudolf Laban considered weight as one of the four major factors of movement. |

| 22 | For instance, (Hutchinson Guest 1989) discusses “the apparent advantages and disadvantages of the different systems”. One of her argument against Beauchamp-Feuillet is based on the absence of difference between steps and leg movements, which is described by Laban as a change, or absence of change, in the distribution of weight. |

| 23 | In 1933, André Breton wrote his famous article about automatic writing, “Le message automatique”, Max Ernest started experimentations with drippings in 1941 and influenced Jackson Pollock who developed action painting from 1944. For the long history of unconscious writing and drawing see (Audinet and Godeau 2012). |

| 24 | Ecstasy was part of 1920s and 1930s modern dance vocabulary, part of a primitivist approach to abstraction. |

| 25 | This point was confirmed by Lucinda Childs in an interview with the author recorded at the Centre national de la danse in 2016. |

| 26 | The Lucinda Childs Dance Company ceased operating in 2000. Between 2013 and 2019, the company was recreated under the umbrella of the independent production company Pomegranate Art. Today, Childs’ repertory is transmitted by the choreographer, former members of the company, and Ruth Childs, her niece. Childs also works as a freelance choreographer for ballets, independent companies, theatre, and opera. |

| 27 | The checkbox is visible on the Figure 7. |

| 28 | The discussion about the forms and status of memory in dance and performance led to strong controversies between the 1990s and 2010s. In the United States see the opposite points of view of (Phelan 1993) and (Auslander 1999), in Europe, (Van Imschoot 2005) and (Pouillaude 2009), among others. |

| 29 | The description of such “systems” has been one of the major contributions of literacy studies and anthropology in order to approach “distributed cognition”. Instead of taking the individual agent as its unit of analysis, these approaches are interested by the socio-technical framework where humans and non-humans interact. Among major contributions see (Goody 1977), (Latour and Woolgar 1979), (Hutchins 1995; 1996), and (Goodwin 1994; 2018). In this article, I propose to adapt this method to an historical research. |

| 30 | For a general account on Holm’s career see (Sorell 1969). |

| 31 | For the history of this diaspora see (Partsch-Bergsohn 1994) and (Manning 1993, pp. 255–85). |

| 32 | Eve Gentry gives a precise account of this early development of Labanotation in New York (Gentry 1992, pp. 17–21). Additional information can be found in Hanya Holm Papers, (S) *MGZMD 136, Jerome Robbins Dance Division, The New York Public Library for the Performing Arts. |

| 33 | For a short history of the Dance Notation Bureau, see (Lu 2009) and their website: http://dancenotation.org (accessed on 19 November 2020). |

| 34 | This specific point is stressed by (Gentry 1992, pp. 9–40) and in the interview conducted by the author with Lucinda Childs in 2016. Hanya Holm papers at the New York Public Library give an approximate idea of what was taught during this period in her school. (Manning 1993, pp. 271–73) analyses the evolution of Holm’s teaching of the 1940s and 1950s. I prefer to nuance her idea that Ausdruckstanz (expressionist dance) was “domesticated” by American modern dance. |

| 35 | Floor plans are employed marginally in the kinetography of Laban. |

| 36 | About this distinction, see (Manning 1993, p. 91). |

| 37 | (Gentry 1992, p. 17) reports the following discussion with Holm when she started teaching around 1940: “[Holm] said shaking her head: ‘What do you want to teach?’ ‘In this first lesson I want to teach body directions, levels, and transferences of weight.’ I knew the right answer; I had learned them in Hanya’s theory class. ‘All right! All you need to do is keep in mind the germ, the basic idea. Don’t plan sequences! They can disintegrate—fall apart. You give your students the concept. You will see what they are ready to do. Then you can suggest the right actions, and they will not forget it!’ In those few words, Hanya gave the key for creative thinking and creative teaching—a limitless source of imagination and action. I learned to teach ideas—concepts—not things.” |

| 38 | (Banes [1987] 2011) introduces a succession of styles from analytic, to metaphorical, metaphysical, and content orientated, which characterized postmodern dance’s evolution from the 1960s to the 1990s. |

| 39 | On this aspect, see the controversy between (Banes [1987] 2011), on one side, and (Banes and Manning 1989), and (Franko 1995), on the other. |

| 40 | We could be guided by the concept of “Relation” developed by the poet and philosopher Édouard Glissant: “La pensée de la Relation, à laquelle il faut revenir, en fin de cette liste, comme à toutes splendeurs qui à la fois relient, relaient, et relatent. Elle ne confond pas des identiques, elle distingue entre des différents, pour mieux les accorder. […] Dans la Relation, ce qui relie est d’abord cette suite des rapports entre les différences, à la rencontre les unes des autres” (Glissant 1990, p. 72). |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).