The Space for Preservation and Dilapidation of Historical Houses in Modlimowo Village in the Light of Post-Dependence Studies and Historical Politics after 1945

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

3.1. Muddelmow Village (Modlimowo)

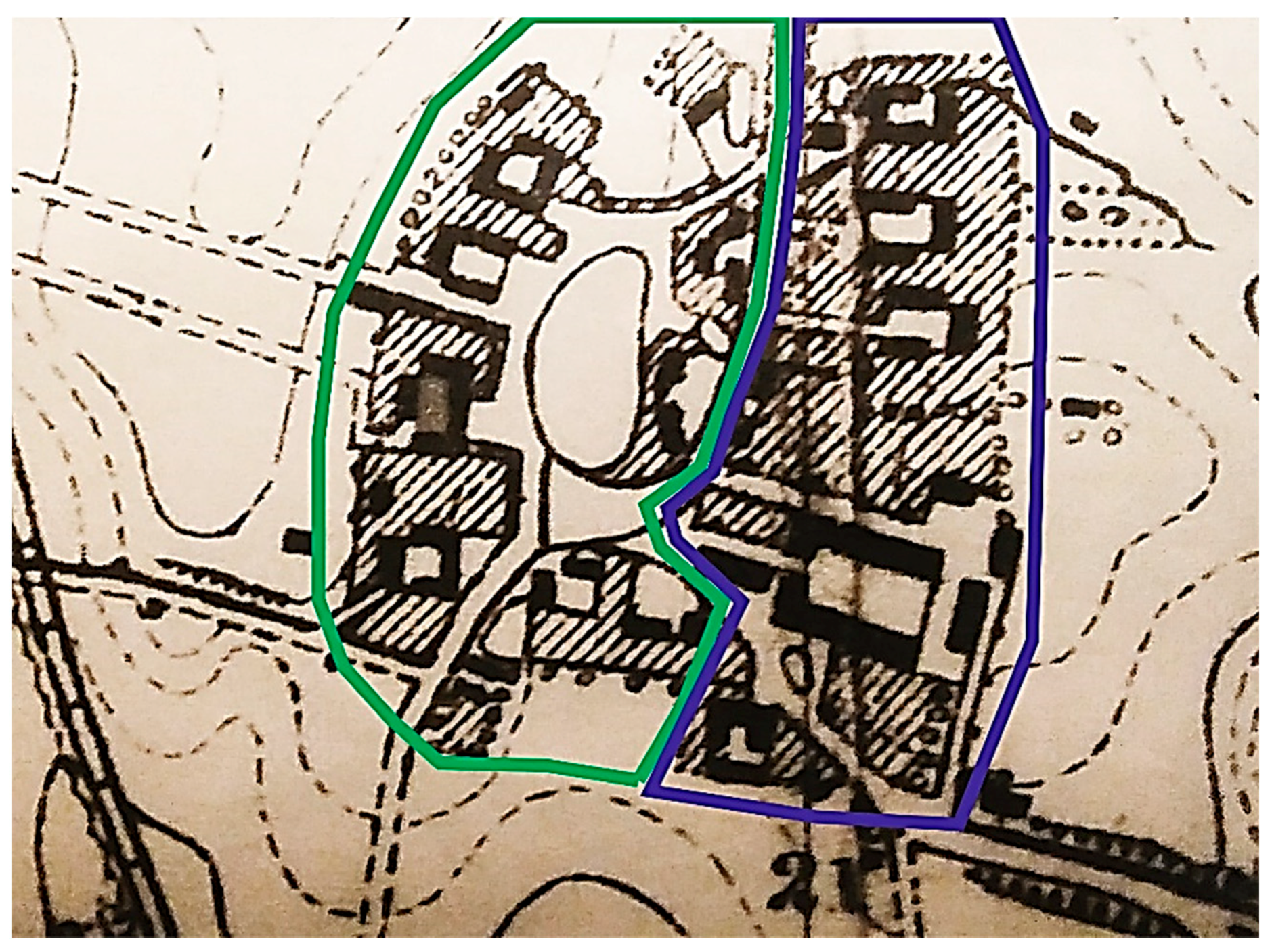

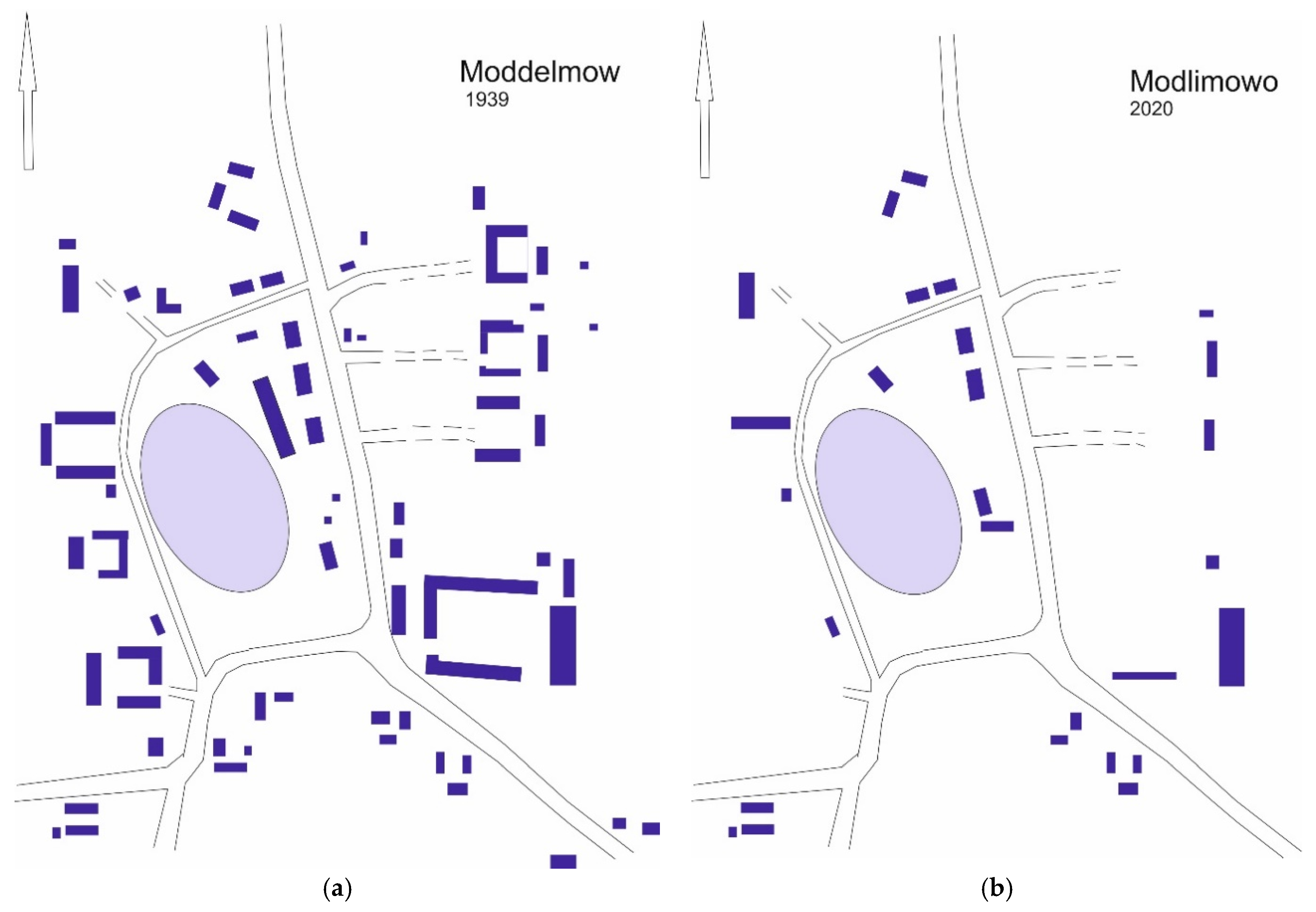

3.2. Spatial Arrangement of the Grange

3.3. Manor and Grange Courtyard in the Modlimowo Village

4. Discussion

4.1. Dilapidated Spatial Arrangement of the Modlimowo Village in the Light of Post-Dependent Discourse

4.1.1. The Degradation of the Grange Architecture in the Village of Modlimowo as a Result of Political and Economic Decisions

4.1.2. Post-Memory Processes

5. Conclusions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Brencz, Andrzej. 2002. Rola niemieckiego dziedzictwa kulturowego w procesie transformacji społeczno-kulturowych na pograniczu zachodnim (na przykładzie środkowego Nadodrza). In Studia Etnologiczne i Antropologiczne. Poznań: Uniwersytet im. Adama Mickiewicza, vol. 6, pp. 161–74. [Google Scholar]

- Glaser, Barney G., and Anselm Leonard Strauss. 2009. Odkrywanie Teorii Ugruntowanej. Strategie Badania Jakościowego. Kraków: Zakład Wydawniczy Nomos. [Google Scholar]

- Halbwachs, Maurice. 1992. On Collective Memory. Chicago and London: University of Chicago Press. First published 1925. [Google Scholar]

- Hirsch, Marianne. 2011. Żałoba i postpamięć. In Teoria Wiedzy O Przeszłości Na Tle Współczesnej Humanistyki. Antologia. Poznań: Wydawnictwo Poznańskie, pp. 247–80. [Google Scholar]

- Konecki, Krzysztof. 2000. Studia Z Metodologii Badań Jakościowych. Teoria Ugruntowana. Warszawa: Wydawnictwo Naukowe PWN. [Google Scholar]

- Kwaśniewski, Krzysztof. 1987. Autochtonizm i autochtonizacja. In Ruch Prawniczy, Ekonomiczny i Socjologiczny. Poznań: Wydział Prawa i Administracji UAM, vol. 1, p. 223. [Google Scholar]

- Lavabre, Marie-Claire. 2012. Circulation, Internationalization, Globalization of the Question of Memory. Journal of Historical Sociology 25: 262–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niezabitowska, Elżbieta. 2014. Metody I Techniki Badawcze W Architekturze. Gliwice: Wydawnictwo Politechniki Śląskiej, p. 137. [Google Scholar]

- Nycz, Ryszard. 2011. Kultura Po Przejściach, Osoby Z Przeszłością. Polski Dyskurs Postzależnościowy. Konteksty I Perspektywy Badawcze. Kraków: Universitas, vol. 1, pp. 5–26. [Google Scholar]

- Przybyłowska, Ilona. 1978. Wywiad swobodny ze standaryzowaną listą poszukiwanych informacji i możliwości jego zastosowania w badaniach socjologicznych. In Przegląd Socjologiczny. Łódź: Łódzkie Towarzystwo Naukowe, vol. 30, pp. 54–68. [Google Scholar]

- Ubertowska, Aleksandra. 2013. Praktykowanie postpamięci. Marianne Hirsch i fotograficzne widma z Czernowitz. In Teksty Drugie. Gdańsk: Uniwersytet Gdański, vol. 4, p. 269. [Google Scholar]

| 1 | Researcher associated with the Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique who developed theories by P. Nora, H. Rouso, E. Durkheim, and M. Halbwachs. The system she has introduced the described mechanisms used by national historical politics to shape social space. (Lavabre 2012), M.-C. Lavabre, Paradigmes de la memoire, https://doi.org/10.4000/transcontinentales.756. |

| 2 | For more information about the Polish Post-Dependence Study Centre (CBDP), see: http://www.cbdp.polon.uw.edu.pl/. The CBDP has published 8 volumes on the subject of dependency, which were particularly useful for the studies. These include: Culture after the ordeal, people with a past. Polish post-dependency discourse—contexts and research perspectives. Vol. 1, ed. Ryszard Nycz, Universitas, Krakow 2011, ISBN: 97883-242-1317-7; (After) the partitions, (After) about the war, (After) about the PRL. Polish post-dependency discourse in the past and today. Vol. 3, ed. Hanna Gosk, Ewa Kraskowska, Universitas. |

| 3 | Since 2017, the village is a part of the Cerkwica Village District, Karnice Commune, County of Gryfice. |

| 4 | PGR—State-owned Agricultural Enterprise—a form of socialist land ownership in Poland in 1949–1993; a farm owned by the state. |

| The contexts of the process of spatial degradation of the Modlimowo village in the time period 1945–2019 | The reasons for the spatial degradation of the Modlimowo village in the time period 1945–2019 | The picture of the spatial degradation of the Modlimowo village in the time period 1945–2019 |

| 1. The context of historical politics | ||

| The context of the political transformation in Central Europe after 1945. | 1. Breaking down the cultural continuity in the Polish Recovered Territories. | The Modlimowo village underwent multi-level spatial degradation. The process of indigenisation that began after the war and consisted in building a new identity in a culturally alien area brought irreversible changes to the spatial arrangement of the village. The breakup of the relationship between material and spiritual culture, fostered over generations in the Recovered Territories, was reflected in the changes that occurred in the village. |

| 2. The process of selective adaptation of the foreign cultural heritage by the new inhabitants of the village. | Many valuable architectural monuments were pulled down, and many priceless works of art were destroyed or stolen. Houses and the entire spatial layout of farms and their facilities in the village were misused or used not in accordance with their intended purpose, which led to their destruction. | |

| 3. Attempts by the new inhabitants of the village to impose their patterns of meaning to unrelated, different forms of culture found in the Recovered Territories. | Whole spatial systems were degraded. The historical layout of the architectural forms of the village was repeatedly reconstructed and underwent many irreversible changes. Numerous historic buildings in the village were demolished, and those that were kept were assigned new functions, inconsistent with their original purpose. | |

| 4. The elimination of the landed gentry class from social life in Poland. | As a result, not only land estates, but also the culturally shaped architectural spaces of historical palaces were irreversibly destroyed. The estate in Modlimowo ceased to fulfil its historical role. The village, which had previously been working for the estate, thus upholding its status, was forced into a new historical context. | |

| 5. The process of the nationalisation of the village spatial structures, built over centuries. | Historic buildings that were taken over and managed by state institutions were often subject to irreversible transformations, both in terms of their functional aspects, as well as their original structure and layout. The Modlimowo estate was transformed into a State Agricultural Enterprise and completely reconstructed. Nationalised farms underwent far-reaching transformations and their division, based on ownership, was changed. As a result, the spatial structure of Modlimowo was deprived of cohesion. | |

| The context of the political and social changes in the late 1980s and early 1990s in Central Europe. | The political transformation in Poland did not occur in tandem with economic changes, for which society was not adequately prepared and was mostly left to its own devices. Some of the inhabitants left the Modlimowo village and moved to cities, leaving their homes. The economic problems of the inhabitants of Modlimowo were reflected in the spatial order of the village, or rather, total lack thereof. | The degradation of individual houses and entire spatial systems was continuing. The abandoned houses could not find new owners for a long time, and consequently fell into a state of dilapidation. |

| The context of the dissolution process of the State Agricultural Enterprises (PGR), which was completed in 1995. | The employees of the State Agricultural Enterprises lost their jobs almost overnight and were left with no future prospects. The poor economic condition of the families who previously worked in such institutions was aggravated by the severely limited opportunities to retrain and take up new employment. The so-called “PGR children” were socially and economically excluded, left without any effective aid from the state. | The palace building was parcelled out among former PGR employees, who were unable to carry out ongoing repairs and take proper care of the technical condition of the buildings. The economic and social motivations of the new tenants accelerated the process of degradation of the technical infrastructure of the estate and palace buildings. The owners of independent farms were facing a difficult economic situation, which forced them to postpone building repairs. As a result, all buildings in the village fell into a state of dilapidation. |

| The context of the privatisation of the State Agricultural Enterprises (PGR), which began in the early 1990s. | Changes in the agricultural policy and Poland’s accession to the European Union were reflected in the way farm buildings were used in the village. Mass breeding of livestock was introduced and became widespread. A large-scale pig farm was established in the village. The introduction of this type of agricultural production, characterised by a high level of nuisance, had an impact on the image of the village of Modlimowo. | The apartments created in the divided palatial space were sold to the previous tenants. The new tenants did not hurry with renovations either, as a result of which the appalling condition of the building continued to aggravate.The pig farm, located on the premises of the historic estate, in the very centre of the village, not only spoiled the cultural landscape, but also completely destroyed the image of the Modlimowo village. People were leaving, and the depopulation of the village continued. It was only after the closure of the poorly managed and controversial animal farm in 2017 that the inhabitants could finally breathe a sigh of relief. The decision also attracted new residents and visitors, looking for a place for summer and weekend relaxation. |

| 2. The context of the post-memory phenomenon | ||

| The context of spatial and temporal frames of collective memory. | Disruptions in the development of the social awareness of the repatriates, as well as the lack of the need to build and maintain a national identity in the newly settled areas, resulted in a negative attitude towards those spaces. The feeling of alienation and misunderstanding of the existing material relics of a foreign culture contributed to their serious neglect during the process of adaptation to a new place. Memories and longing for the abandoned home, which was completely different and did not resemble the current place of residence, were passed onto successive generations of inhabitants of Modlimowo. The new inhabitants did not feel a need for the creation and preservation of the cultural environment which they inherited. | The places, objects, and spaces of the Modlimowo village did not appeal to the new inhabitants. The village, with its unknown and never well-understood history, could not relate to its new inhabitants the processes in which it was formed with all its prosperity. The houses seemed too big to the new settlers, the objects and equipment too fancy and superfluous. In fact, the new inhabitants never even learnt the actual purpose of many devices. It was difficult to transfer one’s old habits to new spaces. In addition, the turbulent geopolitical situation in this area made it impossible to live a peaceful life there. All relics of a foreign culture were subconsciously destroyed. That process started right after re-settlement was started, and has been ongoing ever since. |

| The context of the relationship between family and land. | The relationship between family and land is especially important for peasant families. The new, post-war inhabitants of the Modlimowo village were unable to establish such relationships with the new land. The memory of their homeland, which they had to leave, prevented them from becoming attached to the new, strange land. Successive generations cultivated this aversion. | In Modlimowo, a few families decided to take over and run an independent farm, but the vast majority took up employment on state-managed farms, which were part of the State Agricultural Enterprises. The latter felt released from the obligation to take care of the property. As a result, the need to care for the cultural heritage or create one’s own identity never arose. |

| 3. The context of post-dependence traumas | ||

| The context of mentality. | The socialist realism of the post-war era took a toll on several generations of Poles. The radical indoctrination, a general feeling of fear and helplessness, as well as the difficult living conditions in the post-war Polish countryside must have had a destructive impact on the mentality of subsequent generations. Under such circumstances, higher values, such as law and order or the aesthetic qualities of the inhabited place, no longer mattered. | The lack of care for one’s immediate surroundings led to their destruction. For decades, houses, objects, and spaces were merely used, without any attempts to improve their condition. The current picture of the village of Modlimowo is a result of the post-war decades of neglect, omissions, and bad decisions. |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Rek-Lipczyńska, A. The Space for Preservation and Dilapidation of Historical Houses in Modlimowo Village in the Light of Post-Dependence Studies and Historical Politics after 1945. Arts 2021, 10, 6. https://doi.org/10.3390/arts10010006

Rek-Lipczyńska A. The Space for Preservation and Dilapidation of Historical Houses in Modlimowo Village in the Light of Post-Dependence Studies and Historical Politics after 1945. Arts. 2021; 10(1):6. https://doi.org/10.3390/arts10010006

Chicago/Turabian StyleRek-Lipczyńska, Agnieszka. 2021. "The Space for Preservation and Dilapidation of Historical Houses in Modlimowo Village in the Light of Post-Dependence Studies and Historical Politics after 1945" Arts 10, no. 1: 6. https://doi.org/10.3390/arts10010006

APA StyleRek-Lipczyńska, A. (2021). The Space for Preservation and Dilapidation of Historical Houses in Modlimowo Village in the Light of Post-Dependence Studies and Historical Politics after 1945. Arts, 10(1), 6. https://doi.org/10.3390/arts10010006