The House that Lars Built. The Architecture of Transgression

Abstract

:- We are deemed the ultimate evil.

- All the icons that have had and always will have an impact on the world

- are for me an extravagant art. The noble rot.

- Les hommes ne répresentent apparemment dans le processus morphologique,

- q’une étape intermédiaire entre les singes et les grands édifices.

1. Introduction: The Hut—The Tower—The Labyrinth

The journey through the Nietzschean maze is associated with the spirit of music, and hence also with the Dionysian transgressiveness. I allude to the famous study Die Geburt der Tragödie aus dem Geiste der Musik (The Birth of Tragedy Out of the Spirit of Music), published in 1872, where Nietzsche introduces a distinction between the Apollonian and the Dionysian—in other words, between the glory of passivity (contemplation) and the glory of activity (intoxication). Thus, on the one hand, we have a dream-like world, immersed in harmony and brightness—” the fully wise calm of the god of images” (Nietzsche [1872] 2009, p. 12), while on the other, we have the domain of musical ecstasy and transgression, the “piercing scream” of generations (ibid., p. 20), “the exuberant fecundity of the world will” (ibid., p. 58).“THE GREEK GENIUS FOREIGN TO US.—Oriental or modern, Asiatic or European: compared with the ancient Greeks, everything is characterised by enormity of size and by the revelling in great masses as the expression of the sublime, whilst in Paestum, Pompeii, and Athens we are astonished, when contemplating Greek architecture, to see with what small masses the Greeks were able to express the sublime, and how they loved to express it thus. In the same way, how simple were the Greeks in the idea which they formed of themselves! How far we surpass them in the knowledge of man! Again, how full of labyrinths would our souls and our conceptions of our souls appear in comparison with theirs! If we had to venture upon an architecture after the style of our own souls—(we are too cowardly for that!)—a labyrinth would have to be our model. That music which is peculiar to us, and which really expresses us, lets this be clearly seen! (for in music men let themselves go, because they think there is no one who can see them hiding behind their music).” (Nietzsche 1911, p. 149)8

2. Jack’s Iterology

- This is the melancholy Dane

- That built all the houses that lived in the lane

- Across from the house that Jack built.

Jack: “God created both the lamb and the tiger. The lamb represents innocence, and the tiger represents savagery. Both are perfect and necessary. The tiger lives on blood (…) and that is also the artist’s nature.”

Verge: “You read Blake like the devil reads the Bible. After all, the poor lamb didn’t ask to die in order to become even the greatest art.”

3. The Aestheticisation of Crime and the Sacred Transgression

The literary (and cinematic) technique of defamiliarisation, used to evoke the desired “difficulty”, may, for example, lie in employing a surprising narrator. In this context, Shklovsky points to Leo Tolstoy’s Kholstomer, a story narrated by a horse (Shklovsky [1917] 1965, p. 13) (it is a splendid text, indeed, not only because of that daring strategy). We can also assume that defamiliarisation happens to be caused by the aesthetics of the abject, by turpistic images painfully cutting into our memory and consciousness. The artistic bizarreness is inevitably connected with the transgression, otherness, being in a state of liminality, and, last but not least, with the domain of the uncanny.“The technique of art is to make objects ‘unfamiliar’, to make forms difficult, to increase the difficulty and lengh of perception because the process of perception is an aesthetic end in itself and must be prolonged. Art is a way of experiencing the artfulness of an object, the object is not important” (Shklovsky [1917] 1965, p. 12).

4. Bataille’s “Upturned Eye”—Reconciling Eros and Thanatos

- The market value of suffering and death had become superior

- to that of pleasure and sex, Jed thought,

- and it was probably for this reason that Damien Hirst had, a few years earlier,

- replaced Jeff Koons at the top of the art market.

- Beauty will be convulsive, or will not be at all.

To Bataille, the architecture of the human body, with its outwardly limited form, seems hellish: “Man’s revolt against prison is a rebellion against his own form, against the human figure”, says Hollier ([1974] 1989, p. ix). Only by way of transgression may one experience the feeling of the blissful “formlessness”. Here, the wings of Icarus—the son of Daidalos, who built the Cretan Labyrinth—that melt in Bataillean “rotten sun” (Soleil pourri), serve as the best metaphoric parallel (see: Bataille [1930] 1986a, p. 58).“The slaughterhouse relates to religion in the sense that temples of times past… had two purposes, serving simultaneously for prayers and for slaughter… Nowadays, the slaughterhouse is cursed and quarantined like a boat with cholera abroad… The victims of this curse are neither butcher nor the animals, but those fine folks who have reached the point of not being able to stand their own unseemliness, an unseemliness corresponding in fact to a pathological need for cleanliness” (Hollier [1974] 1989, pp. 12–13).

“In order to achieve the most sublime sweetness and the greatest wines, nature has provided us with various methods. The three most common forms of decomposition are frost… dehydration… and a fungus with the enticingly mysterious name, the noble rot”.

“Nature herself is violent, and however reasonable we may grow, we may be mastered anew by a violence no longer that of nature but that of a rational being who tries to obey but succumbs to stirrings within himself which he cannot bring to heel” (Hollier [1974] 1989, p. 40).

5. Great Edifices and Miserable Ruins

One could say that such cinematic productions partake in a kind of ritual, that is—the social ritual of scandal. (For, it is the skandalon, the “stone of stumbling”, of disgust, that is so much expected by the viewer, whoever wants to be confirmed in his/her “just” indignation). Indeed, it is difficult to dispute Frey’s conclusion that von Trier deliberately plays with his viewers’ expectations, and that he retains his “carefully cultivated reputation”—an echo of Howard Becker’s theory of reputation is present here—”as eccentric, exotic, volatile, or as ‘particularly difficult’ to work with” (Frey 2016, p. 20). Von Trier’s “rebellious, artistic habitus” (ibid., p. 24), has been ultimately affirmed by his controversial statement at the Cannes conference, and then, by his wearing a t-shirt emblazoned with the phrase ‘persona non grata’ at the Berlinale 2014. His latest provocative statements do not really contribute much to that, metaphorically speaking, well-varnished canvas. Even when, in an interview for the “Irish Times”, he comments on the public’s reaction at the premiere of The House that Jack Built, in such a way: “That is fine with me… It is important that a film divides. I am disappointed that it was only 100 people that vomited. I would have liked 200 people to vomit” (see: Clarke 2018).“Speaking roughly and simply, extreme cinema is an international production trend of graphically sexual or violent ‘quality’ films that often stoke critical and popular controversy. Indeed, the trend is distinctive insofar as institutional incentives anticipate a controversial response. Premiering at glamorous film festivals among cultural sophisticates, playing at upmarket cinemas, and featuring in the ‘world cinema’, ‘independent’, or ‘arthouse’ sections at video stores and online streaming services, these productions depend on (offering) culturally inscribed boundaries between art and exploitation.” (Frey 2016, p. 7).

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- à Kempis, Thomas. 1998. The Different Motions of Nature and Grace. In Thomas à Kempis, The Imitation of Christ. Wheaton: Christian Classics Ethereal Library, pp. 90–92. First published [ca. 1400]. Available online: http://www.ccel.org/ccel/kempis/imitation.html (accessed on 17 June 2020).

- Bataille, Georges. 1986. Formless. In Visions of Excess. Selected Writings, 1927–1939. Translated and Edited by Allan Stoekl. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, pp. 31–43. First published 1929. [Google Scholar]

- Bataille, Georges. 1986a. Rotten Sun. In Visions of Excess. Selected Writings, 1927–1939. Translated and Edited by Allan Stoekl. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, pp. 57–58. First published 1930. [Google Scholar]

- Bataille, Georges. 1986b. The Use of Value of D. A. F. Sade. An Open Letter to My Current Comrades. In Visions of Excess. Selected Writings, 1927–1939. Translated and Edited by Allan Stoekl. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, pp. 91–104. First published 1930. [Google Scholar]

- Bataille, Georges. 1986. Erotism: Death and Sensuality. Translated by Mary Dalwood. San Francisco: City Light Books. First published 1957. [Google Scholar]

- Bataille, Georges. 1988. Inner Experience. Translated by Leslie A. Boldt. New York: State University of New York Press. First published 1943. [Google Scholar]

- Bataille, Georges. 1994. On Nietzsche. Translated by Bruce Boone. New York: Paragon House. First published 1945. [Google Scholar]

- Bataille, Georges. 1929. Architecture. Documents: Doctrines, Archéologie, Beaux-Arts, Ethnographie 2: 117. [Google Scholar]

- Bois, Yve-Alain, and Rosalind Krauss. 1997. Formless: A User’s Guide. New York: Zone Books. [Google Scholar]

- Breton, André. 1960. Nadja. Translated by Richard Howard. New York: Grove Press, Paris: Gallimard. First published 1928. [Google Scholar]

- Clarke, Donald. 2018. Lars Von Trier: ‘I Am Disappointed only 100 People Vomited’. The Irish Times, December 7. Available online: https://www.irishtimes.com/culture/film/lars-von-trier-i-am-disappointed-only-100-people-vomited-1.3719920(accessed on 16 June 2020).

- Collinson, Paul. 2019. Heidegger’s Hut. Dreaming of the Middle Ages, and the Absolute—A Visual Essay. Available online: https://www.academia.edu/38091838/Heideggers_Hut_Dreaming_of_the_Middle_Ages_and_the_Absolute_a_visual_essay (accessed on 15 June 2020).

- Durham, Scott. 1998. Phantom Communities. The Simulacrum and the Limits of Postmodernism. Stanford: Stanford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Dyer, Richard. 2007. Pastiche. New York and London: Routledge, Available online: http://www.columbia.edu/itc/film/gaines/historiography/Dyer.pdf (accessed on 12 November 2020).

- Franke, William. 2013. Dante and the Sense of Transgression: The Trespass of the Sign. London and New York: Bloomsbury Academic. [Google Scholar]

- Freud, Sigmund. 1959. The Uncanny. In Collected Papers. Edited by Joan Riviere. Translated by Alix Strachey. New York: Basic Books, vol. 4, pp. 368–407. First published 1919. [Google Scholar]

- Frey, Mattias. 2016. Extreme Cinema: The Transgressive Rhetoric of Today’s Art Film Culture. New Brunswick and London: Rutgers University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Fried, Gregory. 2014. The King Is Dead: Heidegger’s ‘Black Notebooks’. Los Angeles Review of Books, September 13. Available online: https://lareviewofbooks.org/article/king-dead-heideggers-black-notebooks/(accessed on 14 June 2020).

- Fried, Gregory, ed. 2019. Confronting Heidegger: A Critical Dialogue on Politics and Philosophy. London: Rowman and Littlefield Int. [Google Scholar]

- Gilbey, Ryan. 2017. Lars von Trier Negotiating for Cannes Return after 2011 Nazi Comments Ban. The Guardian, March 9. Available online: https://www.theguardian.com/film/2017/mar/09/lars-von-trier-cannes-return-nazi-comments-ban(accessed on 15 June 2020).

- Halliwell, James O. 1842. The Nursery Rhymes of England, Collected Principally from Oral Tradition. London: The Percy Society, Available online: https://books.google.pl/books/about/The_Nursery_Rhymes_of_England_Collected.html?id=gs1swgEACAAJ&redir_esc=y (accessed on 15 June 2020).

- Halliwell, James O. 1849. Popular Rhymes and Nursery Tales: A Sequel to the Nursery Rhymes of England. London: John Russell Smith Ltd., Available online: https://archive.org/details/popularrhymesnur00hallrich/page/6 (accessed on 15 June 2020).

- Hassan, Ihab. 1985. The Culture of Postmodernism. Theory, Culture Society 2: 119–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassan, Ihab. 2003. Beyond Postmodernism: Towards an Aesthetic of Trust. Angelaki. Journal of the Theoretical Humanities 8: 3–11. Available online: https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/09697250301198 (accessed on 12 November 2020).

- Hegel, Georg W. F. 1975. Architecture. In Aesthetics. Lectures on Fine Art. Translated and Edited by Thomas Malcolm Knox. Oxford: Oxford Univeristy Press and Clanderon Press, vol. 2, pp. 630–700. First published 1835. [Google Scholar]

- Heidegger, Martin. 2013. Nature, History, State: 1933–1934. Translated and Edited by Gregory Fried, and Richard Polt. London and New York: Bloomsbury Academic. First published 1933–1934. [Google Scholar]

- Hollier, Denis. 1989. Against Architecture: The Writings of Georges Bataille. Translated by Betsy Wing. Cambridge and London: The MIT Press. First published 1974. [Google Scholar]

- Houellebecq, Michel. 2011. The Map and the Territory. Translated by Gavin Bowd. London: William Heinemann Ltd. and The Random House Group. First published 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Jakobson, Roman. 2002. Two Aspects of Language and Two Types of Aphasic Disturbances. In Roman Jakobson and Morris Halle, Fundamentals of Language. Berlin and New York: Mouton de Gruyter, pp. 67–96. First published 1956. [Google Scholar]

- Jenks, Chris. 2003. Transgression. London and New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Jung, Carl G. 1967. The Relation between the Ego and the Unconscious. In Collected Works of C.G. Jung, Volume 7: Two Essays in Analytical Psychology. Translated and Edited by Gerhard Adler, and Richard F. C. Hull. Princeton: Princeton University Press, pp. 123–244. First published 1916. [Google Scholar]

- Jung, Carl G. 2014. Crime and the Soul. In The Collected Works of C.G. Jung: Complete Digital Edition, vol. 18: The Symbolic Life. Miscellaneous Writings. Edited by Herbert Read, Michael Fordham and Gerhard Adler. Translated by Richard F. C. Hull. Princeton: Princeton University Press, pp. 343–46. First published 1932. [Google Scholar]

- Jung, Carl G. 1997. Five Chapters from ‘Aion’. In Selected Writings. Introduction by Robert Coles. New York: Book-of-the-Month-Club, pp. 285–355. First published 1951. [Google Scholar]

- Jung, Carl G. 1989. Memories, Dreams, Reflections. Edited by Aniela Jaffé. Translated by Richard, and Clara Winston. New York: Random House. First published 1962. [Google Scholar]

- Laugier, Marc-Antoine. 1753. L’essai sur l’architecture. Paris: Chez Duchesne, Available online: https://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/bpt6k856908/f20.item.zoom# (accessed on 12 November 2020).

- Laugier, Marc-Antoine. 1755. An Essay on Architecture. London: T. Osborne and Shipton, Available online: https://archive.org/stream/essayonarchitect00laugrich?ref=ol#page/12/mode/2up (accessed on 12 November 2020).

- Lentricchia, Frank, and Jody McAuliffe. 2003. Crimes of Art and Terror. Chicago and London: The University of Chicago Press. [Google Scholar]

- Nietzsche, Friedrich. 2009. The Birth of Tragedy Out of the Spirit of Music. Translated by Ian Johnston Arlington. Virginia: Richer Resources Publications. First published 1872. [Google Scholar]

- Nietzsche, Friedrich. 2005. Ecce Homo: How to Become What You Are. In The Anti-Christ, Ecce Homo, Twilight of the Idols, and Other Writings. Edited by Aaron Ridley and Judith Norman. Translated by Judith Norman. New York: Cambridge University Press, pp. 69–151. First published 1908. [Google Scholar]

- Nietzsche, Friedrich. 1911. The Dawn of Day. Translated by John McFarland Kennedy. New York: The MacMillan Company, Available online: http://www.gutenberg.org/files/39955/39955-pdf.pdf (accessed on 15 June 2020).

- Ozick, Cynthia. 1997. Dostoyevsky’s Unabomber. The New Yorker, February 24—March 3. Available online: https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/1997/02/24/dostoyevskys-unabomber(accessed on 17 June 2020).

- Panofsky, Erwin. 2018. Studies in Iconology: Humanistic Themes in the Art of the Renaissance. New York: Routledge. First published 1939. [Google Scholar]

- Parkes, Graham. 2005. Introduction. In Friedrich Nietzsche, Thus Spoke Zarathustra: A Book for Everyone and for Nobody. Translated by Graham Parkes. Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press, pp. ix–xxxiii. [Google Scholar]

- Pollio, Marcus Vitruvius. 1914. Vitruvius. Ten Books on Architecture [De Architectura]. Translated by Morris H. Morgan. Cambridge: Harvard University Press. First published 1465, 30–20 BC. Available online: https://archive.is/LflcC (accessed on 12 November 2020).

- Porębski, Mieczysław. 1972. Obraz otaczający: Architektura. In Mieczysław Porębski, Ikonosfera [Iconosphere]. Warszawa: PIW, pp. 151–69. [Google Scholar]

- Roger, Philippe. 1995. A Political Minimalist. In Sade and the Narrative of Transgression. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 76–99. [Google Scholar]

- Sharr, Adam. 2006. Heidegger’s Hut. Cambridge: The MIT Press. [Google Scholar]

- Sherman, Josepha. 2015. Storytelling: An Encyclopedia of Mythology and Folklore. London and New York: Routledge, vol. 1–3. [Google Scholar]

- Shklovsky, Victor. 1965. Art as Technique. In Russian Formalist Criticism: Four Essays. Edited by Lee T. Lemon and Marion J. Reiss. Lincoln and London: University of Nebraska Press, pp. 3–24. First published 1917. [Google Scholar]

- Spicer, Jack. 1998. The House that Jack Built: The Collected Lectures. Edited by Peter Gizzi. Middletown: Wesleyan University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Telegraph Reporters. 2018. PETA Defends Lars von Trier’s ‘Realistic’ Baby Duck Mutilation Scene. The Telegraph, May 18. Available online: https://www.telegraph.co.uk/films/2018/05/18/peta-defends-lars-von-triers-realistic-baby-duck-mutilation/(accessed on 18 June 2020).

- The Einstein Couple. 2018. The Einstein Couple’s Facebook Site, an Entry of September 26. Available online: https://www.facebook.com/theeinsteincouple/ (accessed on 17 June 2020).

- Lars von Trier, director. 2018. The House that Jack Built. The screenplay by Lars von Trier. Available online: https://subslikescript.com/movie/The_House_That_Jack_Built-4003440 (accessed on 15 June 2020).

- Turner, Victor. 1991. The Ritual Process. Structure and Anti-Structure. New York: Cornell University Press and Ithaka. First published 1969. [Google Scholar]

- von Goethe, Johann Wolfgang. 1827. Gesang der Geister über den Wassern. In Goethe’s Werke. Stuttgart and Tübingen: J. G. Gotta, pp. 58–59. First published 1779. [Google Scholar]

- Welchman, John C. 2009. Global Nets: Appropriation and Postmodernity. In Appropriation. Edited by David Evans. Cambridge: The MIT Press, London: Whitechapel Gallery, pp. 194–204. [Google Scholar]

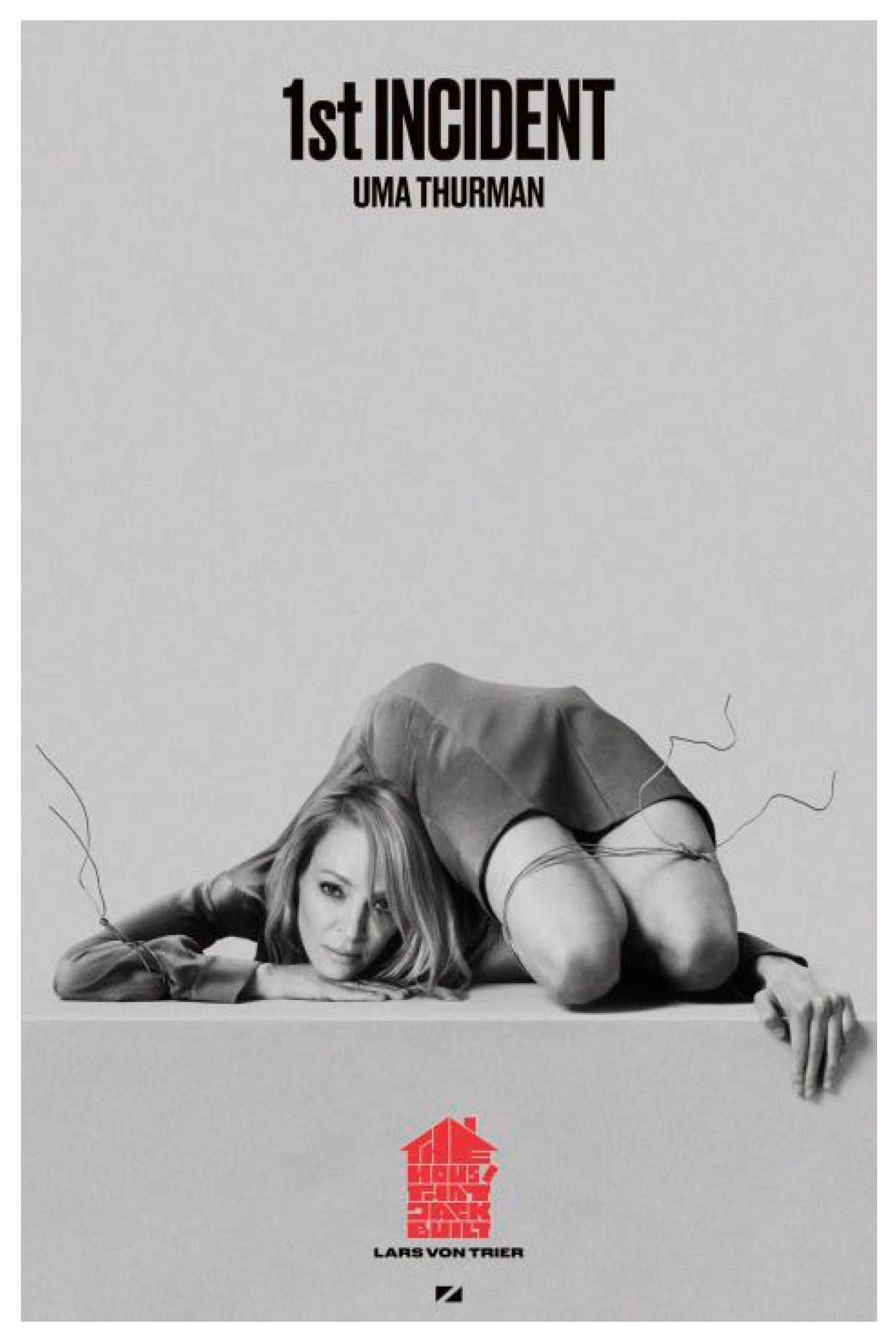

| 1 | (Lars von Trier 2018). The House that Jack Built. Directed by Lars von Trier. Zentropa [Denmark], 2018, 153 min. Screenplay: Lars von Trier. Story by: Lars von Trier and Jenle Hallund. Art director: Simone Grau Roney. Producer: Louise Vesth. Director of photography: Manuel Alberto Claro. Music by: Victor Reyes. Starring: Matt Dillon, Bruno Ganz, Uma Thurman, Siobhan Fallon Hogan, Sofie Gråbøl, Riley Keough, Jeremy Davies. This and other quotations are taken from the script. Available online: https://subslikescript.com/movie/The_House_That_Jack_Built-4003440 (accessed on 15 June 2020). |

| 2 | The text had been published earlier, in 1932, in London’s “Sunday Referee”. Here is one of its most interesting passages: “It is a terrible fact that crime seems to creep up on the criminal as something foreign that gradually gains a hold on him so that eventually he has no knowledge from one moment to another of what he is about to do” (Jung [1932] 2014, p. 343). |

| 3 | Gregory Fried, in an essay—written for Los Angeles Review of Books—concerning Heidegger’s Schwarze Hefte (Black Notebooks), investigates how the philosopher’s anti-semitism was intertwined with his concept pf Being. There we read e.g.: “The Jews represent, for Heidegger, a global force that uproots Being from its historical specificity, its belonging to peoples rooted in time and place. As such, Jews are just another representative of Platonic universalism, or liberalism on the grand scale” (Fried 2014). See also: (Fried 2019). |

| 4 | “The German word unheimlich is obviously the opposite of heimlich, heimisch, meaning “familiar,” “native,” “belonging to the home” (Freud [1919] 1959, p. 370). |

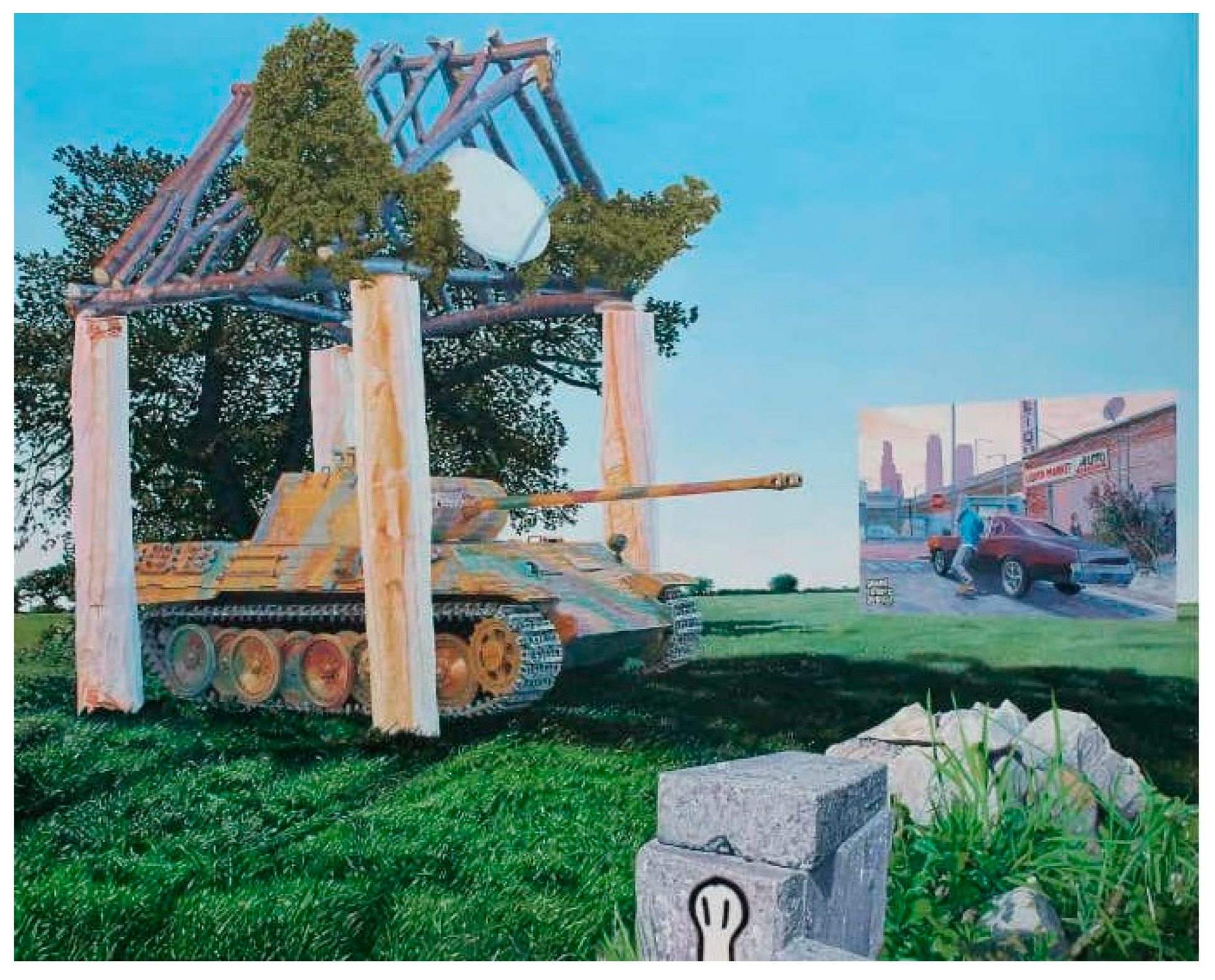

| 5 | In this context, it is worth mentioning that one of Ronald B. Kitaj’s emblematic paintings is entitled The Apotheosis of Groundlessness (1964). I discuss […]. |

| 6 | A scholar (an interpreter), by dint of the “synthetic intuition”, is able to read/uncover the “intrinsic meaning of content, constituting the world of ‘symbolical values’” (Panofsky [1939] 2018, pp. 14, 15). (The expression “symbolical values” was borrowed by Panofsky from Ernst Cassirer). According to Panofsky, iconological interpretation—of the highest degree—needs to be oriented toward the “history of cultural symptoms or ‘symbols’ in general”, and give a suitable “insight into the manner in which, under varying historical conditions, essential tendencies of the human mind were expressed by specific themes and concepts” (Panofsky [1939] 2018, p. 15). |

| 7 | Roman Jakobson in his Fundamentals of Language (1956), draws a distinction between metonymy (metonymic function, as characteristic for Realist prose), and metaphor (metaphoric function, as predominant in Romantic and Symbolic poetry). (It is based on another distinction: the principle of contiguity versus the principle of similarity). Jakobson applies this division to the sphere of visual arts, in which, as he writes “metonymical orientation of cubism, where the object is transformed into a set of synecdoches” gives place to “patently metaphorical attitude” of Surrealist painters (Jakobson [1956] 2002, p. 92). In the context of this article’s topic, it is worth mentioning that a Polish scholar, Mieczysław Porębski—referring to Jakobson’s thought—draws a similar dichotomy between metonymies and metaphors present in the “language” of architecture. In his view, for example, “a paleolithic cave”, as a symbol of a “Mother’s womb” (uterus), may also be read as “the underground kingdom of metonymy” (“podziemne królestwo metonimii”); for rituals celebrated within a cave are always “rites of participation”. Whereas, a Sumerian Ziggurat may serve as an example of an architectural metaphor—“a metaphor piling up into the sky” (“spiętrzająca się w niebo metafora”). According to Porębski, that is because the tower—the Tower of Babel narrative is especially significant here—is not conducive to communication, but rather to “a separating ritual of transfiguration” (“rytuał transfiguracji”). See: (Porębski 1972, pp. 164–65). |

| 8 | The similar metaphor appears in the aphorism no. 230: “‘UTALITARIAN’—At the present time men’s sentiments on moral things run in such labyrinthic paths that, while we demonstrate morality to one man by virtue of its utility, we refute it to another on account of this utility” (Nietzsche 1911, p. 198). The topos of the labyrinth is also present, among others, in Nietzsche’s poetry, namely: his Klage der Ariadne (Lament of Ariadne), inserted in his Dio-nysos-Dithyramben, written in 1888 and first published in 1891. |

| 9 | “Individuation means becoming an ‘in-dividual’, and, in so far as ‘individuality’ embraces our innermost, last, and incomparable uniqueness, it also implies becoming one’s own self. We could therefore translate individuation as ‘coming to selfhood’ or ‘self-realization” (Jung [1916] 1967, p. 173). The self—as Jung explains elsewhere—is far wider than what is enclosed in one’s “conscious personality” (ego): “Clearly, then, the personality as a total phenomenon does not coincide with the ego, that is with the conscious personality, but forms an entity that has to be distinguished from the ego (…). I have suggested calling the total personality which, though present, cannot be fully known, the self. The ego is, by definition, subordinate to the self and is related to it like a part to the whole” (Jung [1951] 1997, p. 289). |

| 10 | In the second chapter of De architectura, entitled: The Origin of the Dwelling House, Vitruvius writes: “Therefore it was the discovery of fire that originally gave rise to the coming together of men, to the deliberative assembly, and to social intercourse. So, as they kept coming together in greater numbers into one place, finding themselves naturally gifted beyond the other animals in not being obliged to walk with faces to the ground, but upright and gazing upon the splendour of the starry firmament (…), they began in that first assembly to construct shelters” (Pollio [1465, 30–20 BC] 1914). |

| 11 | “The man is willing to make himself an abode which covers but not buries him. Some branches broken down in the forest are the proper materials for his design. He chuses four of the strongest, which he raises perpendicularly and which he disposes into a square. Above he puts four others across, and upon these he raises some that incline from both sides. This kind of roof is covered with leaves put together, so that neither the sun nor the rain can penetrate therein; and now the man is lodged. (…) Such is the step of simple nature: It is to the imitation of her proceedings, to which art owes its birth. The little rustic cabin that I have juft described, is the model upon which all the magnificences of architecture have been imagined, it is in coming near in the execution of the simplicity of this first model, that we avoid all essential defects, that we lay hold on true perfection. Pieces of wood raised perpendicularly, give us the idea of columns. The horizontal pieces that are laid upon them, afford us the idea of entablatures. In fine the inclining pieces which form the roof give us the Idea of the pediment” (Laugier 1755, pp. 10–12). Laugier on Greek/Roman architecture: “Architecture owes all that is perfect in it to the Greeks, a free nation, to which it was reserved not to be ignorant of anything in the arts and sciences. The Romans, worthy of admiring, and capable of copying the most excellent models that the Greeks helped them to, were desirous thereto to join their own, and did no less than shew the whole universe, that when perfection is arrived at, there only remains to imitate or decay” (ibid., pp. 3–4). Laugier refers to Maison Carrée in Nîmes as such the perfect example, and in the same place he writes: “Do not let us lose sight of our little rustic cabin. I can see nothing therein, but columns, a floor or entablature; a pointed roof whose two extremities each of them forms what we call a pediment. As yet there is no arch, still less of an arcade, no pedestal, no attique, no door, even nor window. I conclude then with saying, in all the order of architecture, there is only the column, the entablature, and the pediment that can essentially enter into this composition. If each of these three parts are found placed in the situation and with the form which is necessary for it, there will be nothing to add; for the work is perfectly done” (ibid., p. 13). |

| 12 | Jung in his memoirs writes: “I had to achieve a kind of representation in stone of my innermost thoughts and of knowledge I had acquired” (Jung [1962] 1989, p. 223). |

| 13 | As Paul Collinson—an eminent English painter and intellectual—writes in his essay accompanying his painting entitled Heidegger’s Hut: “The Classical is the default of the megalomaniac and totalitarian” (Collinson 2019, p. 4). See also e.g. an interesting study by Adam Sharr: (Sharr 2006). It is worth noting that in this painting Collinson quotes the form of a “hut” as imagined by Charles-Dominique-Joseph Eisen. Eisen’s engraving served as a frontispiece to the second edition of Laugier’s Essay on Architecture. |

| 14 | In painterly tradition, Dante is usually depicted in a red, hooded mantle. That is how he was depicted by, among others: Domenico di Michelino, Sandro Botticelli, William Blake, Jean-Léon Gérôme, William-Adolphe Bouguereau, Gustave Doré, Ilya Repin, or Hans Makart. |

| 15 | See e.g.,: “My body my temple//This temple it tells/‘Step intoo the house that Jack built’”. (Metallica, Load album, 1996, lyrics: James Hetfield). |

| 16 | According to a dictionary entry: “Cumulative rhymes, also known as cumulative verses, and cumulative tales are closely related forms of storytelling. Cumulative rhymes add a line or two with each new verse, after repeating the information presented in the earlier verses. As a result, each new verse is longer than the previous one. The subject of a cummulative rhyme may be serious and created for adults, as in some Hebrew chants, or silly and aimed at both adults and children. Cumulative tales are simple stories with repetitive phases. The tales unwind and then rewind and repeat, with new elements added with each repetition. The rhythmic structure of these tales is very appealing, especially for children.” Entry; “Cumulative Rhymes and Tales” (Sherman 2015, p. 104). James Orchard Halliwell, in his classic anthology of 1842, quotes the whole text of “The House that Jack Built” tale. Here, after Halliwell, I am giving the first and last passages of the rhyme: “1. This is the house that Jack built. 2. This is the malt, That lay in the house that Jack built. 3. This is the rat, That ate the malt, That lay in the house that Jack built. 4. This is the cat That kill’d the rat That ate the malt That lay in the house that Jack built.” […] 11. This is the farmer sowing his corn, That kept the cock that crow’d in the morn, That wake’d the priest all shaven and shorn, That married the man all tattered and torn, That kissed the maiden all forlorn, That milk’d the cow within the crumpled horn, That tossed the dog, That worried the cat, That killed the rat, That ate the malt, That lay in the house that Jack built.” See: (Halliwell 1842, pp. 161–63). |

| 17 | A certain scene featuring an animal raised controversy among the viewers. The case was, though, examined by PETA (People for Ethical Treatment of Animals). On 17th of May 2018 PETA issued a statement, in which they said that the disturbing scene was “created using movie magic” (Telegraph Reporters 2018). |

| 18 | The screenplay was authored by Jacek Borcuch and Szczepan Twardoch. Krystyna Janda was awarded at 2019 Sundance Film Festival for the role of Maria Linde. |

| 19 | Therefore, I cannot fully accept the analogy drawn by Cynthia Ozick in her article entitled Dostoyevsky’s Unabomber, namely—the label of “a philosophical murderer” she gives both to Crime and Punishment’s protagonist and a real killer—Ted Kaczynski. As she writes: “Both are élitists. Both are idealists. Both are murderers”. In my view, concerning Kaczynski—whose bombs killed several people—only the last expression is true (Ozick 1997). |

| 20 | One of Bataille’s indecent pseudonyms. |

| 21 | It is the continuity that would end “our discontinuous mode of existence as defined and separate individuals” (Bataille [1957] 1986, p. 18). |

| 22 | “This flight headed towards the summit (which is the constitution of knowledge—dominating the realms themselves) is only one of the paths of the ‘labyrinth’. However we can now in no way avoid this path which we must follow from attraction to attraction in search of ‘being’” (Bataille [1943] 1988, p. 86). |

| 23 | “[…] Around me extends the void, the darkness of the real world—I exist, I remain blind, in anguish (…) If I envisage my coming into the world (…) a single chance decided the possibility of this self which I am” (Bataille [1943] 1988, p. 69). In the same passage, dedicated to death—as, “in a sense, an imposture”—we read: “It is by dying, without possible evasion, that I will perceive the rupture which constitutes my nature and in which I have transcended ‘‘what exists” (...). The self-that-dies (...) truly perceives what surrounds it to be a void and itself to be a challenge to this void...” (ibid., p. 71). |

| 24 | “A dictionary begins when it no longer gives the meaning of words, but their tasks. Thus formless is not only an adjective having a given meaning, but a term that serves to bring things down in the world, generally requiring that each thing have its form. What it designates has no rights in any sense and gets itself squashed everywhere, like a spider or an earthworm. In fact, for academic men to be happy, the universe would have to have shape. All of philosophy has no other goal: it is a matter of giving a frock coat to what is, a mathematical frock coat. On the other hand, affirming that the universe resembles nothing and is only formless amounts to saying that the universe is something like a spider or spit” (Bataille [1929] 1986, p. 31). |

| 25 | Later in the text, Bataille writes: “Transgression is complementary to the profane world, exceeding the limits but not destroying it” (Bataille [1957] 1986, p. 67). A similar thought may be found in Chris Jenks: “To transgress is to go beyond the bounds or limits set by a commandment or law or convention, it is to violate or infringe. However to transgress is also more than this, it is to announce or even laudate the commandment, the law or the convention. Transgression is deeply reflexive act of denial and affirmation” (Jenks 2003, p. 3). |

| 26 | Philippe Roger describes de Sade as “a political minimalist”, stating that it is inappropriate to link his oeuvre (solely) with “the excess of evil”. As he remarks: “[…] While his contemporaries use fiction as a transparent veil and a coded convention to convey and promote ideas, Sade ‘fictionalizes’ ideology to stir, displace, shock. Ambiguity prevails in all of his political declarations” (Roger 1995, p. 80). And further we read: “[…] Cruelty is not violence, and even less it is politically motivated or state-sponsored violence” (ibid., p. 82). |

| 27 | Chris Jenks, in the aforementioned study on Transgression points out the importance of, as he says: “Kojève’s intervention”; that is, to the profound impact that the Russian-French philosopher had on the poststructuralist movement. Among those who attended Alexandre Kojève’s Sorbonne lectures (1933–1939)—dedicated mostly to the Hegelian Phenomenology of Spirit—was Bataille, as well as, for example: André Breton, Raymond Queneau, and Jacques Lacan (Jenks 2003, p. 61). |

| 28 | “The storming of the Bastille is symbolic of this state of affairs: it is hard to explain this mass movement other than through the people’s animosity (animus) against the monuments that are its real masters.” See: (Hollier [1974] 1989, pp. ix–x). |

| 29 | “The museum is what the Terror invented to replace the king, to replace the irreplacible”. See: (Hollier [1974] 1989, p. xiii). In the same place Bataille writes: “The origin of the modern museum would thus be linked to the development of the guillotine.” See: (ibid., p. xiii). |

| 30 | The notion of habitus used here is closely connected to the one conceptualised and described by Pierre Bourdieu in La Distinction. Critique sociale du judgement (Paris: Minuit, 1979), or in Le Sens pratique (Paris: Seuil, 1980). |

| 31 | As Howard Becker writes, in his already classic study on Art Worlds, first published in 1982: “The romantic myth of the artist suggests that people with such gifts cannot be subjected to the constraints imposed on other members of society; we must allow them to violate rules of decorum, propriety, and common sense everyone else must follow on risk of being punished.” See: (Frey 2016, p. 14). |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2020 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Stępnik, M. The House that Lars Built. The Architecture of Transgression. Arts 2020, 9, 127. https://doi.org/10.3390/arts9040127

Stępnik M. The House that Lars Built. The Architecture of Transgression. Arts. 2020; 9(4):127. https://doi.org/10.3390/arts9040127

Chicago/Turabian StyleStępnik, Małgorzata. 2020. "The House that Lars Built. The Architecture of Transgression" Arts 9, no. 4: 127. https://doi.org/10.3390/arts9040127

APA StyleStępnik, M. (2020). The House that Lars Built. The Architecture of Transgression. Arts, 9(4), 127. https://doi.org/10.3390/arts9040127