1. Introduction

This research responds to the urban intensification debate in Auckland by questioning the perceived role of urban amenities in promoting quality of urban life at higher densities in four of the city’s suburban neighbourhoods: Takapuna, Kingsland, Albany, and Botany.

Like Auckland, many Pacific-Rim cities in Australia and North America have long imbued compact city principles in to their urban growth management strategies. Cities such as Brisbane, Sydney, Melbourne, Vancouver, and Portland are facing a similar set of development issues related to their growing yet ageing populations and shifting demographics towards smaller households. While a system of common law is in place, governmental and institutional arrangements do differ between the cities [

1]. Unlike Auckland, for example, each of the aforementioned cities has both national, state, and local (city-wide) levels of planning governance, whereas Auckland has national and local only. This changes funding streams and methods for implementation. Despite these structural differences, notable similarities exist between the growth management strategies of these cities including their greenbelt ideology that utilises an urban growth boundary to restrict greenfield development at urban peripheries [

2] as well as the promotion of networks of higher density mixed-use development clustered around walkable town centres.

There have been various waves of higher density housing trends, across many Pacific-Rim cities in Australasia and North America, including Auckland [

3,

4]. However, the quality compact goals of these cities largely exist in contradiction to the dominant post-war ethos of suburbia still prevalent despite the considerable regeneration and redevelopment of their downtowns, waterfronts and other former-industrial land. Resident resistance to suburban intensification across these Pacific-Rim cities has been widely noted [

5,

6]. Writing about traditional aspirational housing ideals both Alves [

3] and Randolph [

4] in Australia, and Smith and Billig in North America, identify a long-standing preference for suburban single-storey detached dwellings. This trend is referred to as the Quarter-Acre Pavlova Paradise in New Zealand [

7]. Alves identifies that research and planning action has been lacking in suburban areas [

3]; transforming and intensifying suburbia, while still maintaining the distinct character and perceived liveability of the suburban model, is the next big challenge for urban planners and designers.

In this research it is argued that a key element in the transition to more urbanised environments is related to the extent to which urban amenities have a role in resident perceptions of quality of urban life. Mulligan and Carruthers identify that “

amenities are key to understanding quality of life because they are precisely what make some places attractive for living and working, especially relative to other places that do not have them and/or are burdened with their opposites, disamenities” [

8] (p. 107).

Urban amenities are understood in this research to mean specific urban facilities that contribute to the urban living experience of residents [

9]; they are linked to the daily life needs of residents in a neighbourhood. Some examples given by Randall include: “

grocers, convenience stores, access to public transit, schools and professional services [doctor or dentist]” [

10] (p. 47). Gottlieb confirms that “

residential amenities may be defined as place-specific goods or services that enter the utility functions of residents directly” [

11] (p. 1413). Both Mathur and Stein [

12] (p. 252) and McNulty

et al. [

13] refer to urban amenities as “quality of life factors” and Howie

et al., confirm that “

urban amenities are generally accepted as being important to a household’s sense of place” [

14] (p. 235). There are both public sector amenities provided by councils, such as parks, public squares and recreational facilities, as well as private sector amenities such as cafés, restaurants, retail and other goods or service providers.

There are two main reasons given in the literature as to why focusing on the role of urban amenities in the delivery of urban intensification is important. Firstly, in an economic sense, it is argued that a diversity of urban amenities attract economic activity to a city in terms of firms and labour wanting to be located in a place of high amenity value [

8,

15,

16,

17]. In other words, “

the provision of amenities generates urban advantages that perpetuate the concentration of economic activity and population in, and in closer proximity to, them” [

18] (p. 40). Mathur and Stein also confirm that “

the emerging literature on amenities seems to indicate that one of the most effective ways to attract knowledge workers in the regions and promote economic development is the creation of amenities” [

12] (p. 265).

In line with economic reasoning, the second broader reasoning is that the accessibility and convenience of urban amenities contribute to quality of urban life experiences [

19,

20,

21,

22]. As society changes and evolves so too do people’s quality of life requirements and aspirations. There are clear linkages acknowledged in the literature between the provision of varied urban amenities and changing lifestyles and aspirations [

1,

23,

24]; demographic changes for example have a direct impact on the spatial configuration of the city and are closely tied to changing lifestyle preferences. Increasing ethnic diversity through globalisation also contributes to urbanism trends as new city residents bring their own understandings of intensification and the relationship between urban amenities and perceived quality of life. There are also issues of affordability and potential new home owners now being priced out of the market; these buyers may turn to higher densities as a way of entering the property market. Internationally, authors such as Clark [

25] have recognised that demographic and ethnographic changes alter the way cities are viewed and experienced and as such, the provision of urban amenities and their integration in to urban areas must also be reconsidered. Randolph [

4] in particular, writing about Australia, highlights the need for planners to understand the amenity requirements for higher density neighbourhoods, particularly if more children are going to be living in these urbanised environments, thus increasing the need for schools, child care facilities, and recreational areas. An example given by Schmitz

et al. is that the increasing number of “work-at-homers” “

often feel isolated in typical suburban communities and would like access to the amenities that are available to downtown office workers” [

26] (p. 6). They consider that options such as the corner coffee shop, lunch bars, a print centre, local gym or recreation area, and retail facilities should be better integrated in to suburban environments. Auckland Council also acknowledges that the city needs “

more housing adjacent to local shops and services, public open spaces and areas with expansive views” [

27] (p. 70). And yet, research into how this might occur and how different amenities are valued by residents is very limited in New Zealand. In this paper, understanding the relationship between urban amenities and perceived quality of life is based on the premise that “

dwellings are important, but so too is the location of the dwelling” [

28] (p. 98).

Whatever the reasons for intensification, the question remains: if suburbia transforms, will these higher density neighbourhoods meet the aspirations and needs of future residents? It is therefore necessary to ask residents about the urban amenities they use and value and the relationships they see between these amenities and their sense of location satisfaction.

2. Method

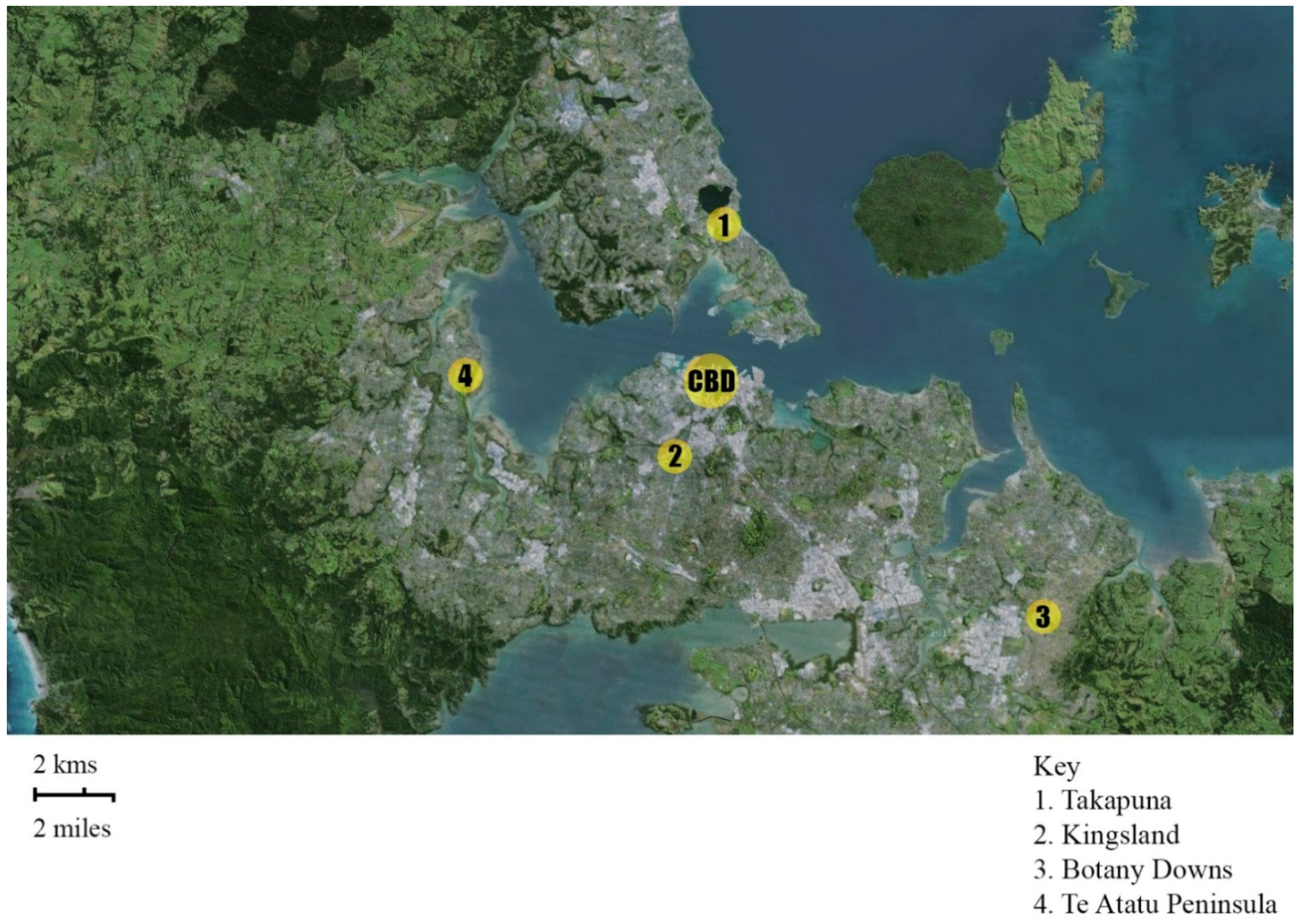

Guided by a constructivist Grounded Theory approach the researcher conducted 57 hour-long face-to-face structured interviews with local residents from four case study neighbourhoods in Auckland: Takapuna, Kingsland, Botany Downs, and Te Atatu Peninsula (see

Figure 1). The structured interviews were recorded and transcribed. The analysis included initial line-by-line manual coding before open and selective coding phases were conducted by the researcher in NVivo. Theoretical coding was the third coding phase in line with Grounded Theory methods.

Figure 1.

The four case study neighbourhoods (Source Google Maps).

Figure 1.

The four case study neighbourhoods (Source Google Maps).

The chosen neighbourhoods represent both inner and outer fringe belt suburbs [

29] that have all experienced strong increases in both rental and owner-occupier medium density developments. They range from being 4.3 to 20 km away from Auckland’s Central Business District (CBD) and are located to the north, west, and south-east of Auckland. Within these neighbourhoods, medium density case study developments were chosen as the locations where direct mailbox dropping would occur to attract the interviewees for the study.

The criteria for selecting the developments within the case study neighbourhoods included: that each of the developments was multi-unit, at a Net Residential Density (NRD) greater than 35 dpHA, and in a location that provided local amenities; for example a town centre. This meant a mix of typologies ranging from three- and five-storey apartment complexes to attached townhouses and units. Developments also had to have been established in their communities for a period of more than three years and accessible for interviews. The developments at 130 Anzac St. in Takapuna, 435 New North Road in Kingsland, and 84 Gunner Drive in Te Atatu required approval from building managers to mail box drop as their mail boxes were concealed within the developments.

2.1. Takapuna

Takapuna is a city fringe suburb in the north of Auckland, 9.6 km from the CBD. It has been extensively considered for intensification by North Shore City Council and Auckland Regional Council. It has also been identified as a key growth area in the Auckland Plan [

30] and the Unitary Plan [

31]. Takapuna was also identified by Fontein [

32] as an area that is well placed for market-led intensification due to its access to a range of amenities; including, transit, employment opportunities, mixed use residential and business land, and natural amenities [

33] (pp. 33–35). Twenty residents from three developments in Takapuna were interviewed. These developments ranged from townhouses with a Net Residential Density (NRD) of 35.8 dpHA to three-storey apartments that were 60.8 dpHA to even higher density five-storey apartments that were 167.9 dpHA (see

Figure 2 and

Table 1).

Figure 2.

Takapuna case study area: interviewees were from the developments shown in orange, the town centre is shown in yellow. Letters correspond to

Table 1. (Source: Google Maps).

Figure 2.

Takapuna case study area: interviewees were from the developments shown in orange, the town centre is shown in yellow. Letters correspond to

Table 1. (Source: Google Maps).

Table 1.

Information about the chosen developments where residents were approached through direct mailbox drops to be interviewed. (The letters in the column “Map #” correspond to the maps in

Figure 2,

Figure 3,

Figure 4 and

Figure 5).

Table 1.

Information about the chosen developments where residents were approached through direct mailbox drops to be interviewed. (The letters in the column “Map #” correspond to the maps in Figure 2, Figure 3, Figure 4 and Figure 5).

| Case Study Neighbourhood | Site | Map # | Development Lot Size (m2) | # Units | NRD (Net Residential Density) (dpHA) | Typology | Storeys | Year Built | Total Number of Mail Drops * | Total Number of Interviews |

|---|

| Takapuna | 130 Anzac St. | A | 7,980 | 134 | 167.9 | Apartments | 5 | 2007 | 234 | 20 |

| 73 Anzac St. | B | 6,910 | 42 | 60.8 | Apartments | 3 | 2005 |

| 7 Killarney St. | C | 4,750 | 17 | 35.8 | Rowhouses | 3 | 2001 |

| Kingsland | 39 Sandringham Rd. | D | 875 | 25 | 285.7 | Apartments | 4 | 2011 | 152 | 13 |

| 435 New North Rd. | E | 3,200 | 90 | 281.3 | Mixed use with Apartments | 6 | 2006 |

| Botany Downs | Armoy Drive development A | F | 7,700 | 59 | 76.6 | Townhouses and Rowhouses | 2 | 2005 | 460 | 14 |

| Armoy Drive development B | G | 29,290 | 153 | 52.2 | Apartments/Units | 2 | 2005 |

| Spalding Rise development | H | 29,990 | 149 | 49.7 | Townhouses and Rowhouses | 2 | 2000–2003 |

| Kirikiri Lane development | I | 11,200 | 128 | 114.3 | Townhouses and Rowhouses | 3 | 2005 |

| Te Atatu Peninsula | 84 Gunner Drive | J | 1,650 | 37 | 224.2 | Mixed use with Apartments | 6 | 2006 | 166 | 10 |

| Vinograd Drive development | K | 24,130 | 93 | 38.5 | Townhouses and Rowhouses | 2 | 2001–2004 |

| Gunner Drive development | L | 4,870 | 18 | 37.0 | Apartments | 2 | 2000 |

| – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | 1,012 | 57 |

2.2. Kingsland

Kingsland is a city fringe suburb, just 4.3 km from the CBD, and one of the top five rental growth suburbs in Auckland [

34]. While it has grown in popularity because of its proximity to a range of urban amenities and access to the CBD, it remains predominantly suburban, made up of single-storey detached dwellings, and a noticeably smaller town centre than the other chosen areas. Medium density housing in the area is increasing; although currently these are largely apartments rather than a mix of medium density typologies such as terraced houses and units. Thirteen residents from two developments were interviewed. These developments were both four-storey apartment buildings at densities of 281.3 and 285.7 dpHA (see

Figure 3 and

Table 1). One was a mixed-use typology with apartments built above the high street shops. In this case it was four storeys on the road side but six storeys on the parallel street where the site contour sloped down.

Figure 3.

Kingsland case study area: interviewees were from the developments shown in orange, the town centre is shown in yellow. Letters correspond to

Table 1. (Source: Google Maps).

Figure 3.

Kingsland case study area: interviewees were from the developments shown in orange, the town centre is shown in yellow. Letters correspond to

Table 1. (Source: Google Maps).

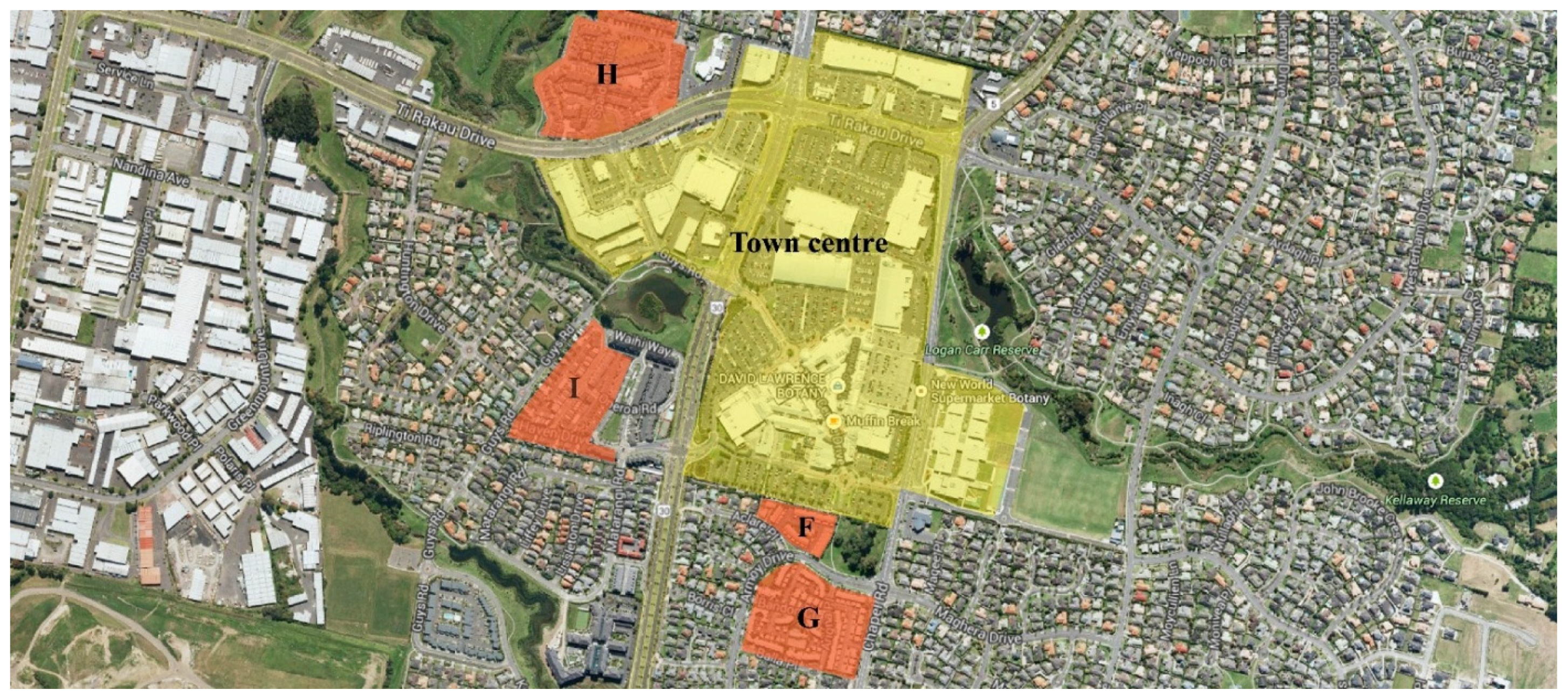

2.3. Botany Downs

Botany Downs is the furthest suburb, at 20 km south-east from Auckland’s CBD, considered in this research. It is an area that has seen considerable growth in the last 5–10 years, frequently in the form of two-storey attached dwellings in large scale, partially gated communities. These developments ranged from 49.7 to 114.3 dpHA (see

Figure 4 and

Table 1). 14 residents were interviewed from four developments in Botany Downs.

Figure 4.

Botany Downs case study area: interviewees were from the developments shown in orange, the town centre is shown in yellow. Letters correspond to

Table 1. (Source: Google Maps).

Figure 4.

Botany Downs case study area: interviewees were from the developments shown in orange, the town centre is shown in yellow. Letters correspond to

Table 1. (Source: Google Maps).

2.4. Te Atatu Peninsula

Te Atatu Peninsula is 15.3 km to the west of Auckland’s CBD. While it is dominated by low density single-storey detached dwellings its popularity and increasing levels of gentrification have seen attached and semi-attached two-storey townhouses develop to the east of the town centre. 10 residents from three development areas were interviewed. Two of the developments range in density from 37 to 38.5 dpHA. However, the third is a six-storey apartment building, with retail on the ground floor, that has been developed on the main street leading in to the town centre. It has a relatively high density of 224.2 dpHA; considerably greater that the surrounding suburban area that measures between 10 and 20 dpHA (see

Figure 5 and

Table 1).

Figure 5.

Te Atatu Peninsula case study area: interviewees were from the developments shown in orange, the town centre is shown in yellow. Letters correspond to

Table 1. (Source: Google Maps).

Figure 5.

Te Atatu Peninsula case study area: interviewees were from the developments shown in orange, the town centre is shown in yellow. Letters correspond to

Table 1. (Source: Google Maps).

Table 1 is a summary of information about the chosen developments across the four case study neighbourhoods including the lot size, number of units, Net Residential Density (NRD), their typology, the number of storeys and the year they were built. It also shows the total number of mail drops conducted and the number of interviews conducted in each area. In total 36 females and 21 males responded to the mail-box letter drops. Interviewees were spread between the ages of 23 and 87; the average age of respondents was 44. Of the 57 interviewees, 26 were owner-occupiers and 31 were renters. The average length of dwelling tenure was three years; the shortest time being one month and the longest 13 years. Seven interviewees lived alone, 25 were couples, six interviewees lived with flatmates, and two lived with extended family members. Seventeen had a least one child living at home, of these 10 had children under seven. Only three had two or more children living at home.

Thirty-six of the interviewees were born in New Zealand and nearly half of these had also spent time living overseas where they were exposed to a range of different lifestyles and housing norms. Of the 21 born overseas, only 11 were from countries where English was not their first language. Countries of origin included The United States of America, Australia, Scotland, England, China, Korea, Malaysia, Vietnam, Singapore, India, Portugal, Bulgaria, Slovakia, Serbia, Jordan, Mozambique, and South Africa. Nineteen of the interviewees had had experience living outside of Auckland in areas ranging from Christchurch and Wellington to rural Otago, Napier, Gisborne, Palmerston North, Tauranga, Rotorua, and Tairua. Despite the geographic, demographic, and socio-economic variations between the case study suburbs and the interviewees, clear patterns emerged among the findings.

Interview questions covered household structure, dwelling tenure, current employment and travel habits as well as housing histories and aspirations. Interviewees were asked about the urban amenities they use, how often, their accessibility, and how they valued them. How residents defined quality of life and their perceptions of urban intensification and density were also explored.

3. Results

3.1. Making Medium Density Housing Choices

All the interviewees, excluding two, had had previous experience living in standalone houses; most often it was the housing norm they had experienced the most. Over half, 58% of the interviewees, had also experienced apartment or townhouse living at some stage prior to their current housing experiences; whether it be as students, while living overseas, or while living in a flatting situation away from their regular family home.

When asked about their process for making housing choices 41 interviewees mentioned proximity to urban amenities and the resultant convenience as one of their main reasons for moving to their current housing. Medium density typologies also played a factor, ease of maintenance in particular was stated as affecting housing choices for 26 of the interviewees. Twelve interviewees mentioned trading-off living in a standalone house for an apartment or townhouse because they found them to be warmer and cleaner than the available standalone housing stock they could rent for a similar price point. Safety, security, proximity to work, affordability, and place attachment created due to proximity to friends and family were other reasons frequently mentioned by interviewees as reasons that had influenced their decision making when deciding to live in their current location.

3.2. Future Housing Aspirations

More than half of interviewees saw themselves continuing to live in the same suburb where they currently resided over the coming five years. Where this was not the case the predominant aspirations held were to look at land on the urban fringe for affordability reasons, or to move to a more rural environment as part of long term lifestyle ambitions. Retirees interviewed were split between moving out of Auckland or to fringe areas where they could live quieter lives or staying in apartment typologies, usually in their current neighbourhood, that would be easy for them to maintain or lock up and leave if they planned to travel. Where this was the case proximity to a range of urban amenities and the ability to walk or use public transport were noted as key location drivers to support their active urban lifestyles.

Twenty-two interviewees mentioned their or their partners proximity to work as part of their decision making process around housing and reasoning for wanting to stay in the same area. This largely came down to the notion that interviewees did not want to be “sitting in traffic half the day”. Place attachment due to family and friends living in the same area was also frequently mentioned as a factor affecting the interviewees’ location aspirations.

When asked about the type of housing they saw themselves living in in five years’ time 26 interviewees saw themselves in medium density typologies, including low rise apartments (of three to five storeys) or terraced housing (similar to their current typologies). Twenty-five saw themselves in low density typologies including single detached dwellings on small or large sections and six were unsure what their housing aspirations were at the present time. Of the 25 interviewees who identified an aspiration for low density typologies, five of them simultaneously discussed medium density options as being an equally likely aspiration they would be happy with. This would shift the total number of those who aspired to medium density housing solutions from 26 to 31 respondents. Typologies at the same or higher densities than their current housing scenarios, namely low rise apartments and terraced housing, were also the notably favoured “back-up” plan for interviewees when they were asked where they might be happy to live if their first choice was not available to them for whatever reason.

The concept of “lifestyle” was used by interviewees as a reason to justify both their low and medium density preferences. Those who wanted standalone houses as their first choice usually spoke about wanting space, peace and quiet, the ability to have pets and a garden, and “the ability to cater for acquisitions which you can’t do in a smaller apartment”. A small number of interviewees who aspired to live in a standalone house did acknowledge that many of the issues they currently had with medium density typologies, particularly related to storage and shared garden space, could be addressed if the apartments or terraced houses were well designed, built from quality materials, and larger than the CBD “shoeboxes” that they currently associated with the idea of “higher density living”.

Those who wanted to live in low rise apartments or terraced houses cited proximity to urban amenities as their main reason for choosing this typology over others, stating that they “like going out and doing things and having everything on our doorstep”. One interviewee commented, “I’ll compromise on smallness… I don’t actually mind the smallness, but I like to be close to the city”. When asked why, the interviewee commented about the liveliness of the city contributing to their quality of life because they were always busy and engaged with what was going on around them.

Other reasoning given for preferring medium density typologies included security and their low maintenance nature. One interviewee commented that they wanted to live “somewhere that is clean, tidy and nice. I really don’t want a garden that gets neglected because I don’t have the time for it. I’d rather not have it at all”. Another interviewee saw living in an apartment as meaning they could pay off their small mortgage and “make a bit of a nest egg” so that they could travel and enjoy their upcoming retirement.

A number of interviewees who saw themselves living in medium density dwellings over the next 5 years, and in some cases longer term, did temper their aspiration with the concern that many apartments currently available were very small and did not always meet their needs; lack of storage, lack of car parking for multi-bedroom apartments, and small kitchens rather than four burner hobs were the most frequently mentioned concerns. One interviewee spoke of wanting to live in “stacked villas”, the villa being a popular traditional standalone housing typology in New Zealand. They wanted a villa on the third or fourth floor; in other words a spatial layout that they were familiar with that had larger shared spaces, more storage, and a larger outside living area than the majority of apartments they had seen previously in Auckland.

Additional reasoning given by those interviewees who stated that they would prefer to live in a standalone house related to their desire to renovate and because they thought that owning a home was part of the “kiwi dream”. Fear that the build quality of apartments would be substandard was also cited as a concern by some interviewees. A further concern was that they thought buying an apartment would disadvantage them financially because the capital gains were perceived to be higher for properties with standalone houses. One interviewee who currently owned their apartment commented that they would eventually like to buy a house “out in the suburbs” but that it “purely would be an investment property and we’d stay living in the apartment”.

3.3. Views about Quality of Life and Urban Amenities

When interviewees were asked directly about how they defined quality of life their responses covered a broad range of issues; the importance of health, income, safety, and broader discussions of freedom, enjoyment and fulfillment were raised. Twenty-four interviewees related their perceptions of quality of life to concepts of neighbourhood and the availability and accessibility of urban amenities. When asked about the perceived role of urban amenities in a neighbourhood, all 57 interviewees linked it to quality of life aspects, in particular to notions of accessibility and the associated convenience or ease this bought to their lives.

When asked to define the term urban amenities seven interviewees thought of them predominantly as being council provided amenities. Examples given included public transport, public pools, community centres, and libraries. Four were unsure of the terms specific meaning. The remaining 43 interviewees thought of urban amenities as all the services and infrastructure they used in their daily lives. One interviewee commenting that “urban amenities would be all of the things that you value in a community and so that would be the open space, the walkways, the park space, the variety of shops or facilities and our proximity to them”.

Food related amenities, such as supermarkets, cafés, and restaurants, were the urban amenities considered to be the most important by interviewees. Supermarkets were specifically mentioned the most frequently. Recreation amenities and public spaces were also favoured. The areas where residents reported using their local amenities daily and usually accessed them by foot (this was weather dependent) were Takapuna and Botany Downs. Te Atatu Peninsula had similar responses for a variety of food and community amenities but many interviewees commented about their needing to drive for retail amenities. While Kingsland residents were positive about their local café and restaurant culture, walkability for urban amenities such as chemists, clothing stores, dairies and supermarkets was questioned by the interviewees who predominantly drove to neighbouring suburbs for these urban amenities because they were not available to them in Kingsland.

4. Discussion

The initial findings on housing choices in Auckland are in line with the work of Haarhoff and Beattie [

35,

36], Mead and McGregor [

37], and Syme

et al. [

5] who all found that residents living in medium density developments in Auckland rated highly the convenience of living in close proximity to the urban amenities that they valued in their daily lives; including shops, cafés and restaurants, schools, their workplaces, public transport, and public spaces (particularly if they were park and recreation facilities). These studies also all identified that the locations of these urban amenities and their convenience was a significant factor for residents in choosing to live where they did.

A surprising change from previous studies, where standalone houses featured prominently as the favoured typology residents saw themselves living in, was the relatively even divide between the aspirations of residents being low density versus medium density typologies. The interviews suggest that the increasing popularity of low rise apartments and terraced housing can be tied to changing lifestyle expectations in the city across a broad spectrum of demographics and lifestages. The shift to favouring similar to higher densities than the interviewees were already living in suggests a disjuncture between the current supply and potential demand for higher density typologies in Auckland’s suburbs.

However, the concern that current medium density typologies did not meet the daily life needs of residents, raises questions about how some interviewees might have responded to questions about their housing aspirations if more medium density typology options were available to them within their current suburban areas. The interviewee responses would suggest that a greater acceptance of medium density typologies may occur if concerns about build quality and lack of storage and kitchen space were addressed.

Furthermore, when questioned about how they defined urban amenities the overwhelming majority of interviewees thought of them as all the services and infrastructure they used in their daily lives. This contrasts with much of the planning policy and strategy in New Zealand as well as international literature where amenities are often considered in silos; for example as “natural amenities”, “entertainment amenities”, or public amenities provided by council. It was therefore found in this research that in order to begin understanding the dynamics of liveability in our current suburban neighbourhoods, “how” residents use and value urban amenities seamlessly across their neighbourhood must be investigated. This means to consider all urban amenities simultaneously as they relate to liveability, whether they be public sector amenities provided by councils, such as parks, public squares and recreational facilities, or private sector amenities such as cafés, restaurants, retail and other goods or service providers. The biggest disjuncture between the findings of this research and current planning policy and strategy in Auckland is just how seamlessly interviewees thought about the spatial relationship between their dwellings and the urban amenities they wanted to live in close proximity to. Current residential zoning, for example, is at odds with this very intimate integration of urban amenities in to the suburban fabric and further research is considerably needed around this issue.