Semantic Network Simulation vs. Traditional Brainstorming: Enhancing Architectural Design Conflict Resolution and Innovation

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Related Theoretical Research

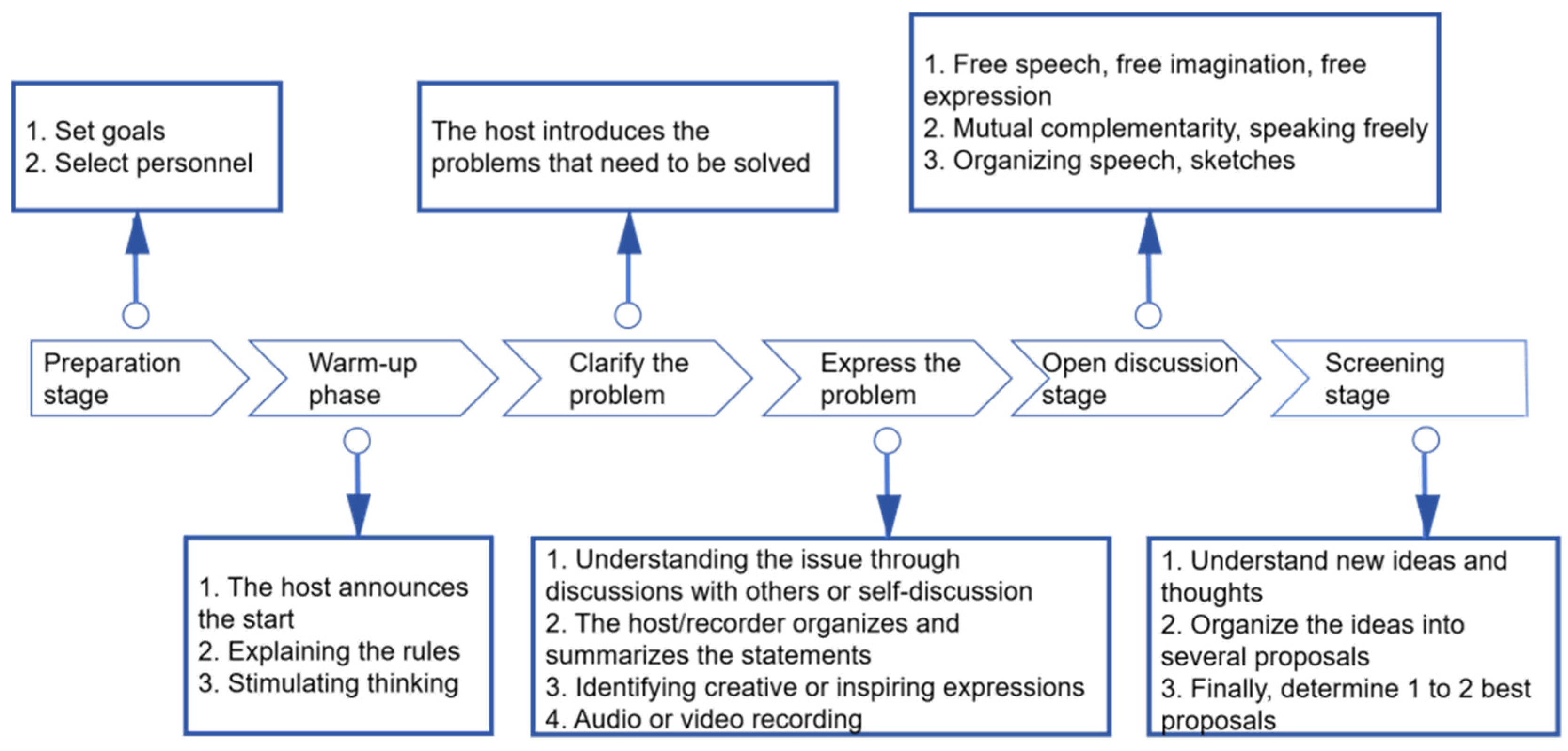

2.1. Traditional Brainstorming in Architectural Design

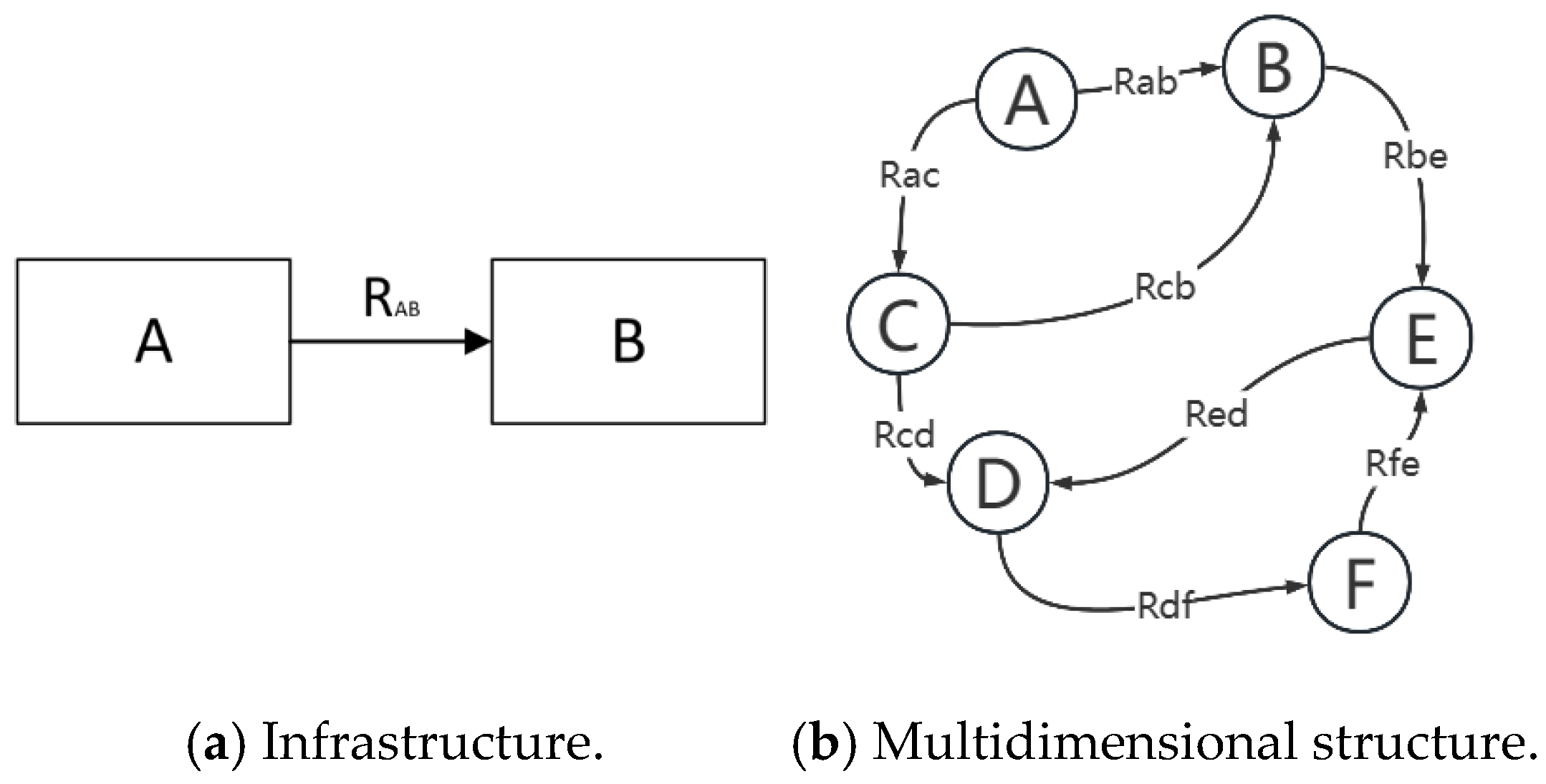

2.2. Elements and Structure of Semantic Networks

2.3. The Role and Significance of Semantic Network Simulation

2.4. Comparative Analysis of Two Research Methods

2.5. SN Simulation Step-by-Step Diagram

3. Materials and Methods

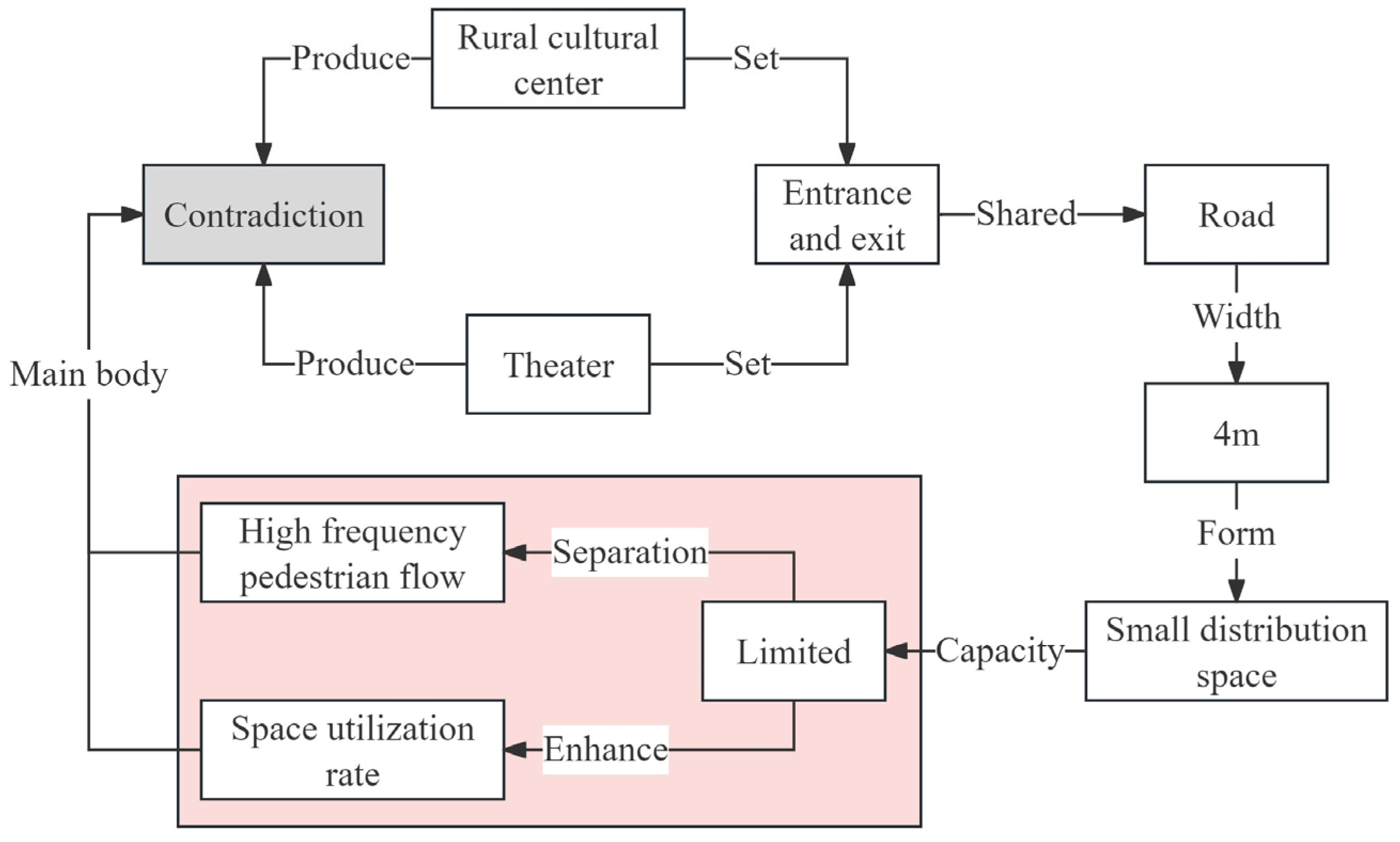

3.1. Experimental Tasks

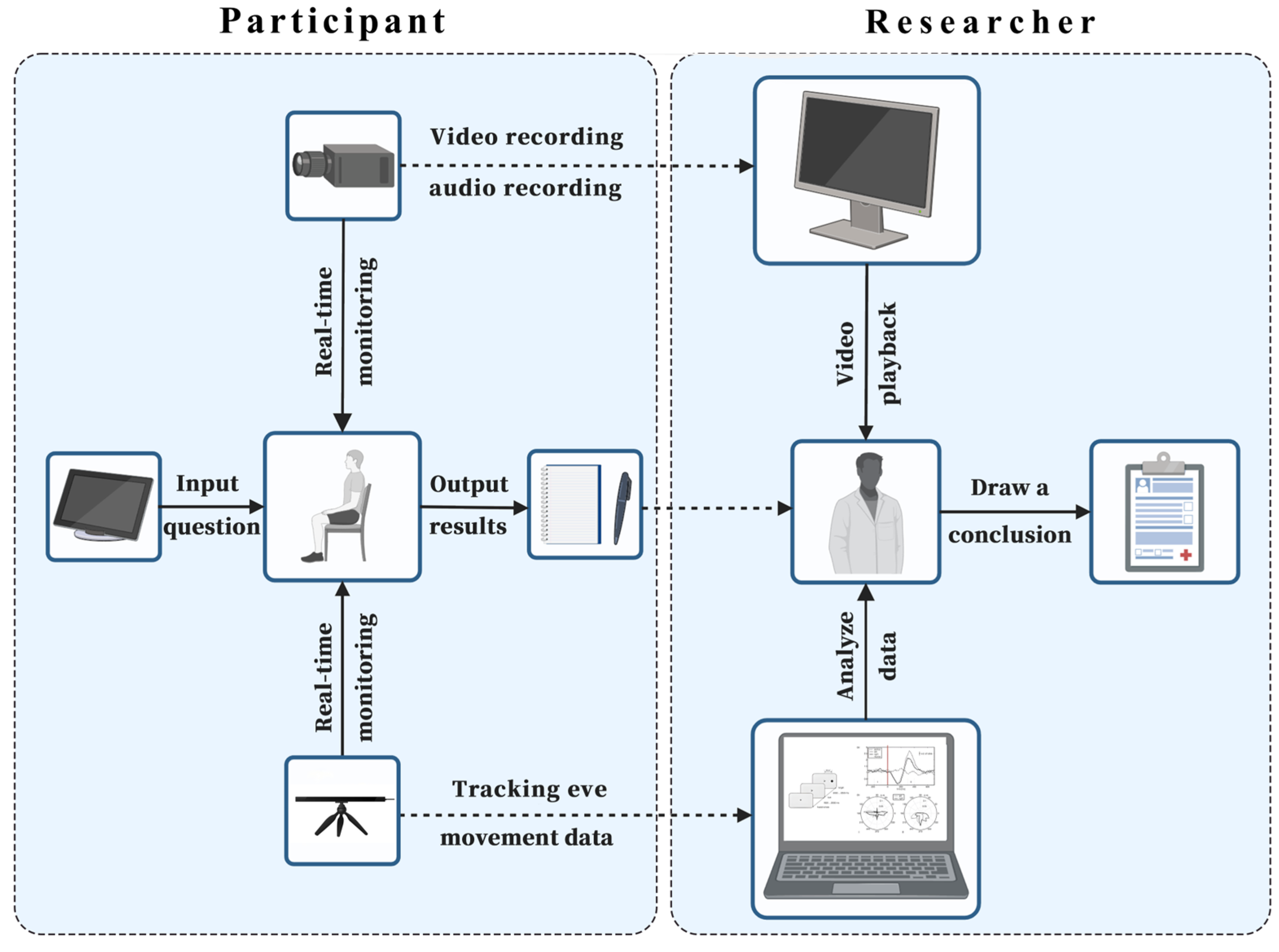

3.2. Experimental Design

3.2.1. Participants

3.2.2. Experimental Equipment and Environment

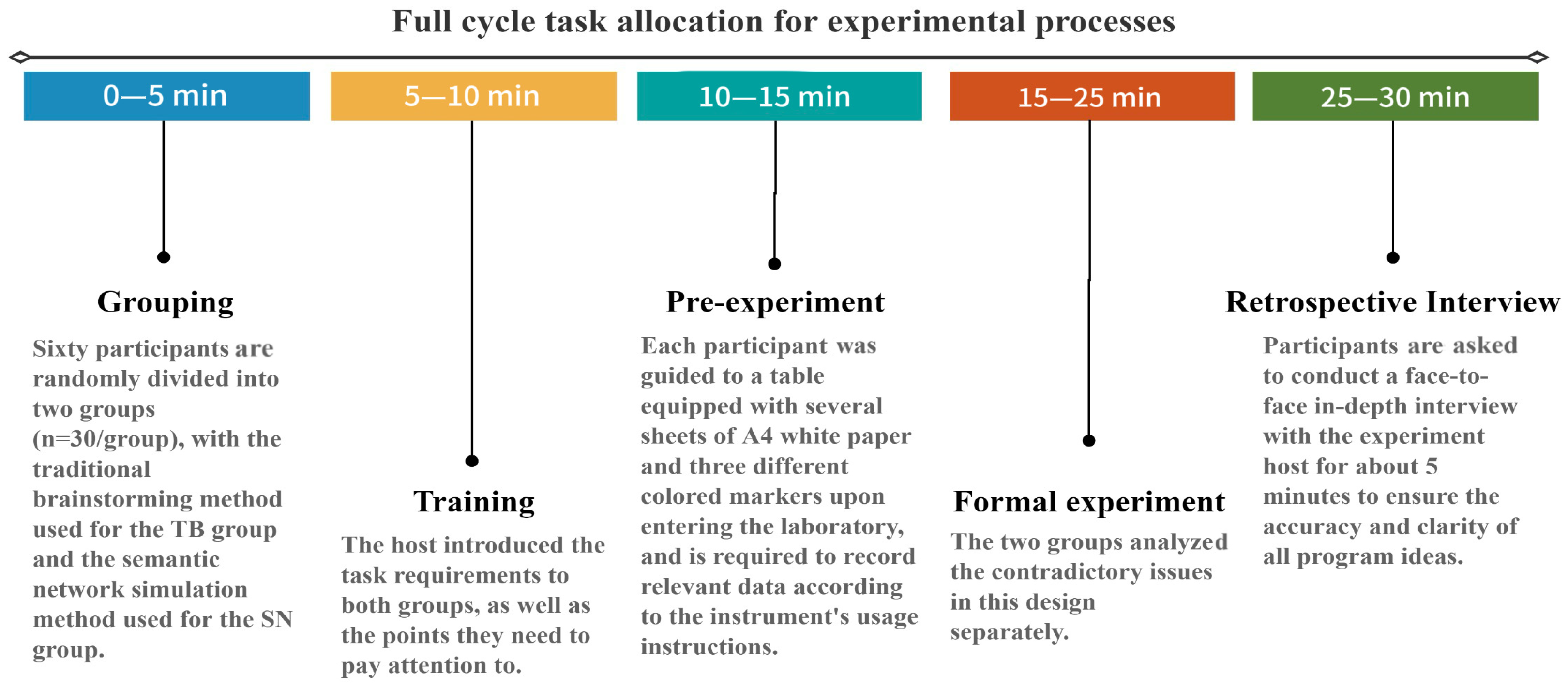

3.2.3. Experimental Procedures

3.3. Data Measurement

3.3.1. Eye Movement Index Measurement

3.3.2. Evaluation of Outcome Indicators

- (1)

- For the SN group: Effective cognitive units = the number of logical closed loops of “conflict–constraint–solution” in semantic network nodes (instead of isolated node count), which must meet the dual criteria of “clear node attributes + complete relationship links”;

- (2)

- For the TB group: Through experimental recording transcription, sketch annotation text, and retrospective interview records, “clearly categorizable design concepts + corresponding logical explanations” are extracted as effective cognitive units. Two independent coders identified these units following the same “logical closed-loop” standard as the SN group.

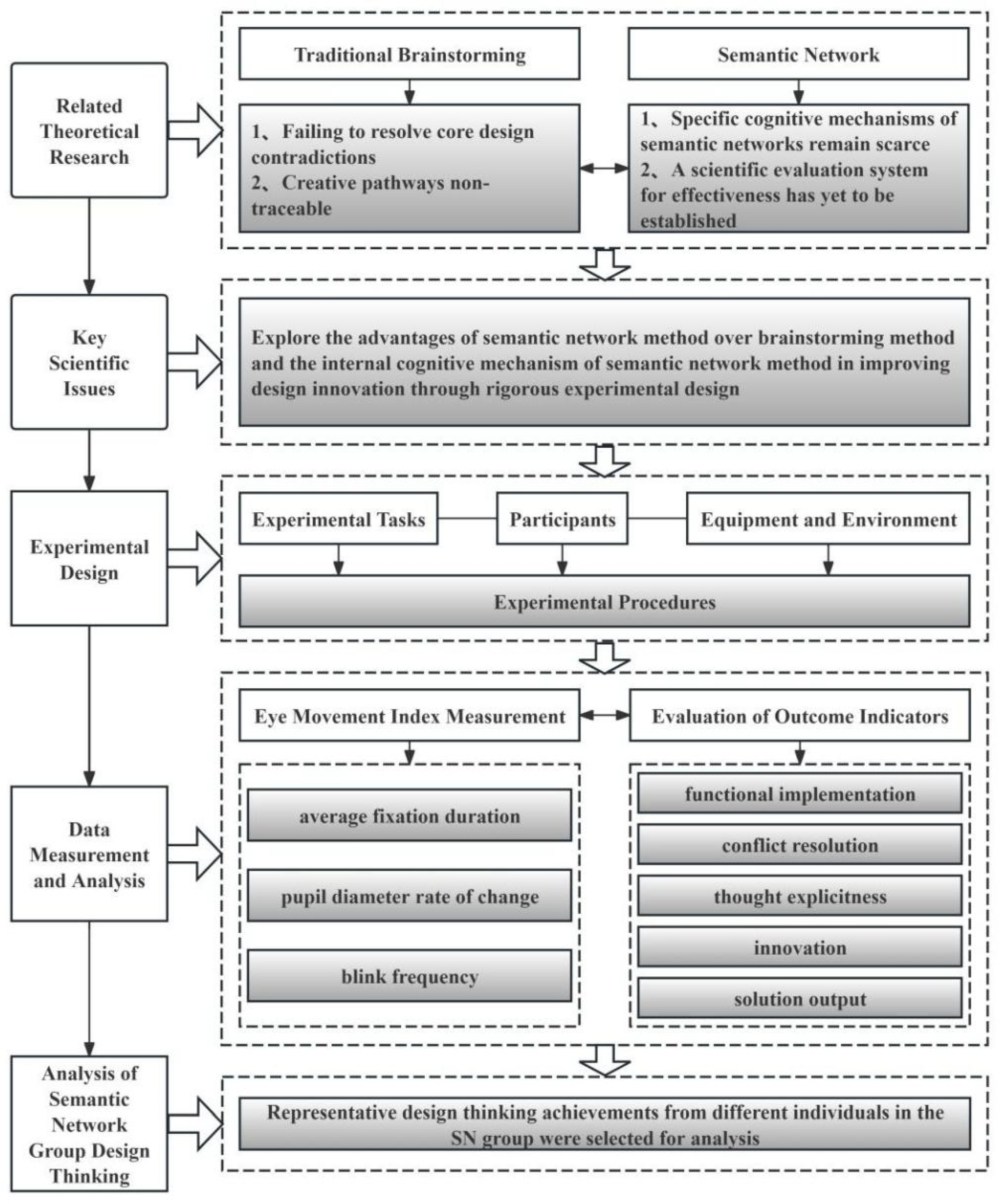

3.4. Research Approach and Framework

4. Experimental Results

4.1. Time Allocation of Thinking Process and Cognitive Characteristics

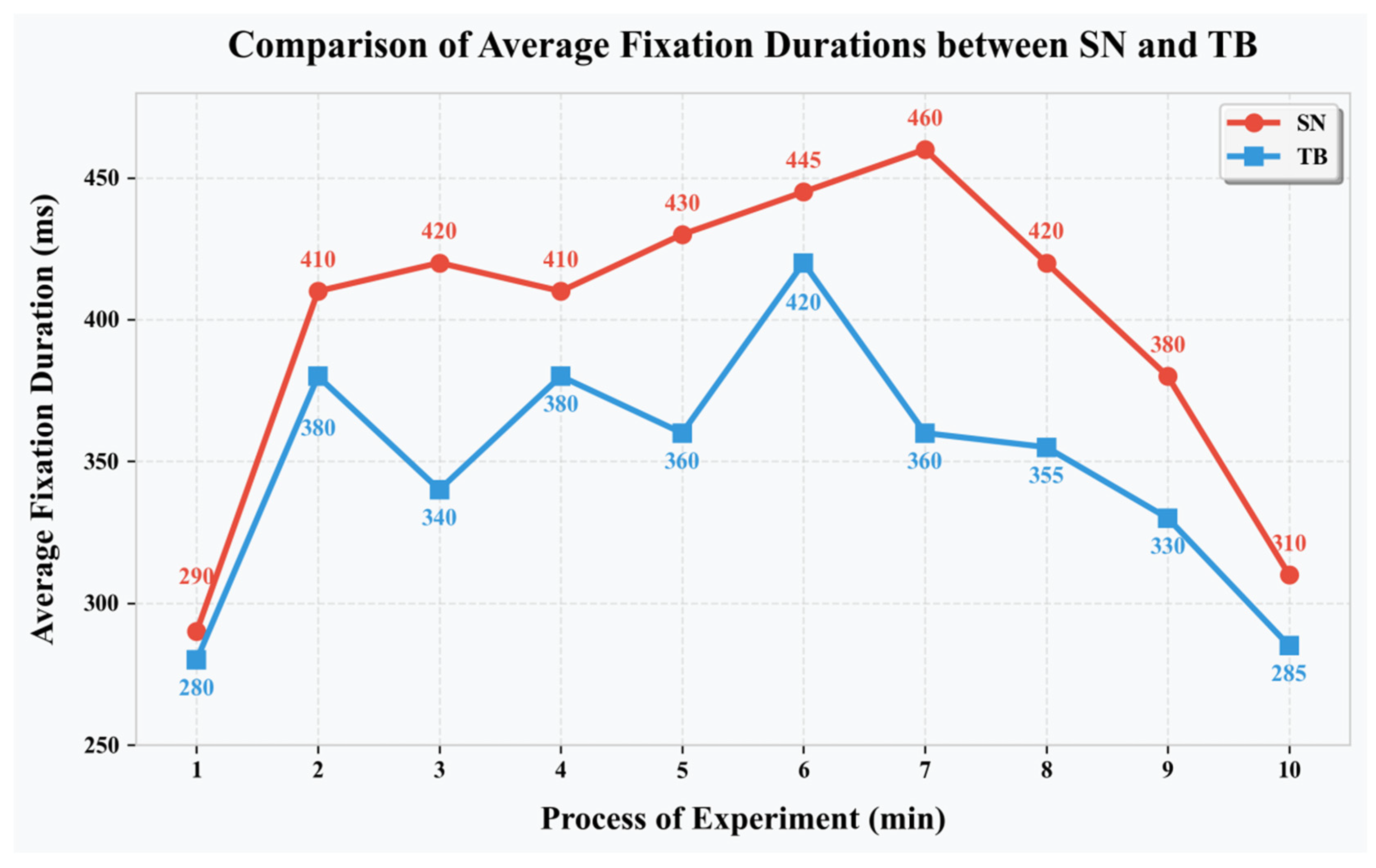

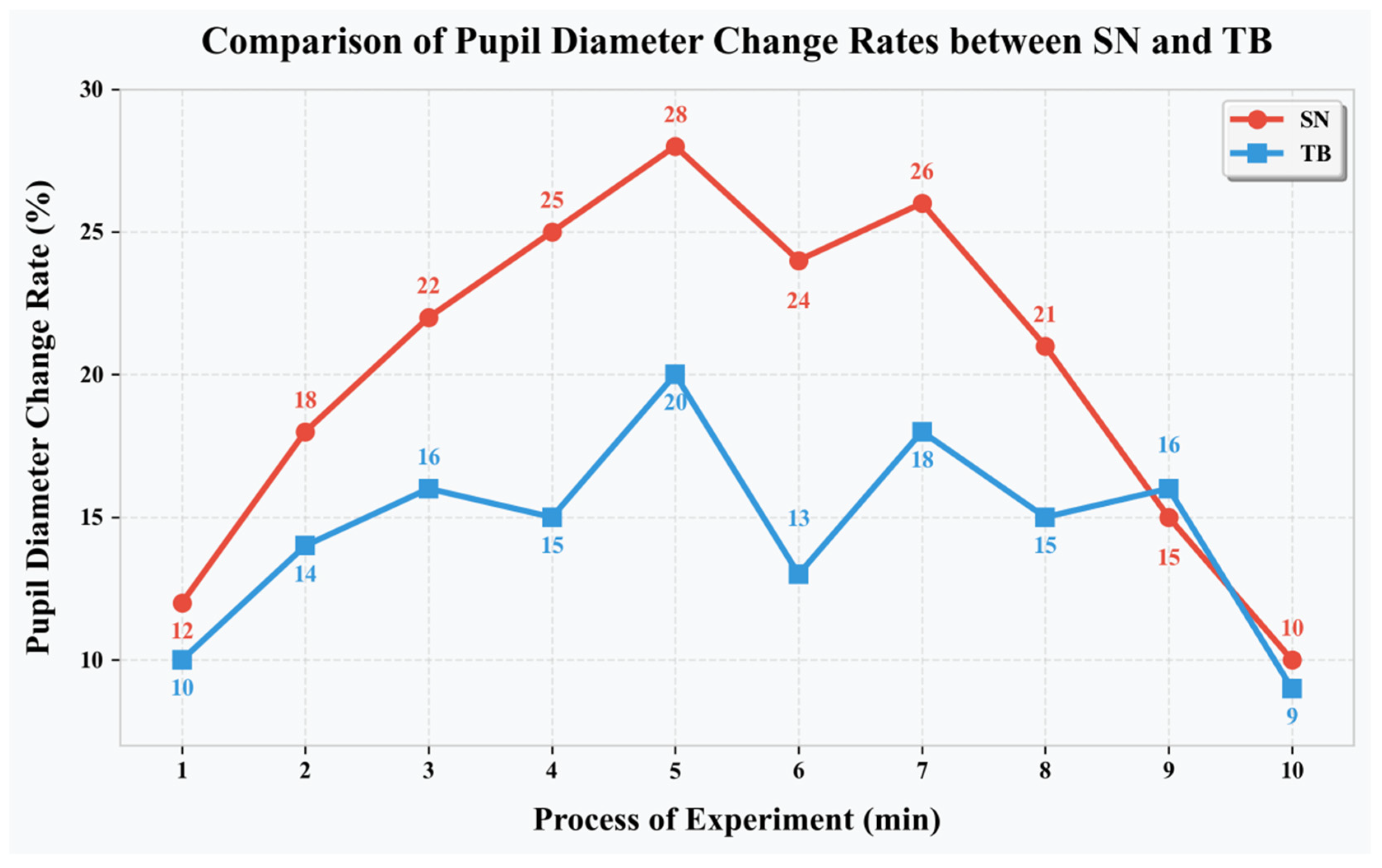

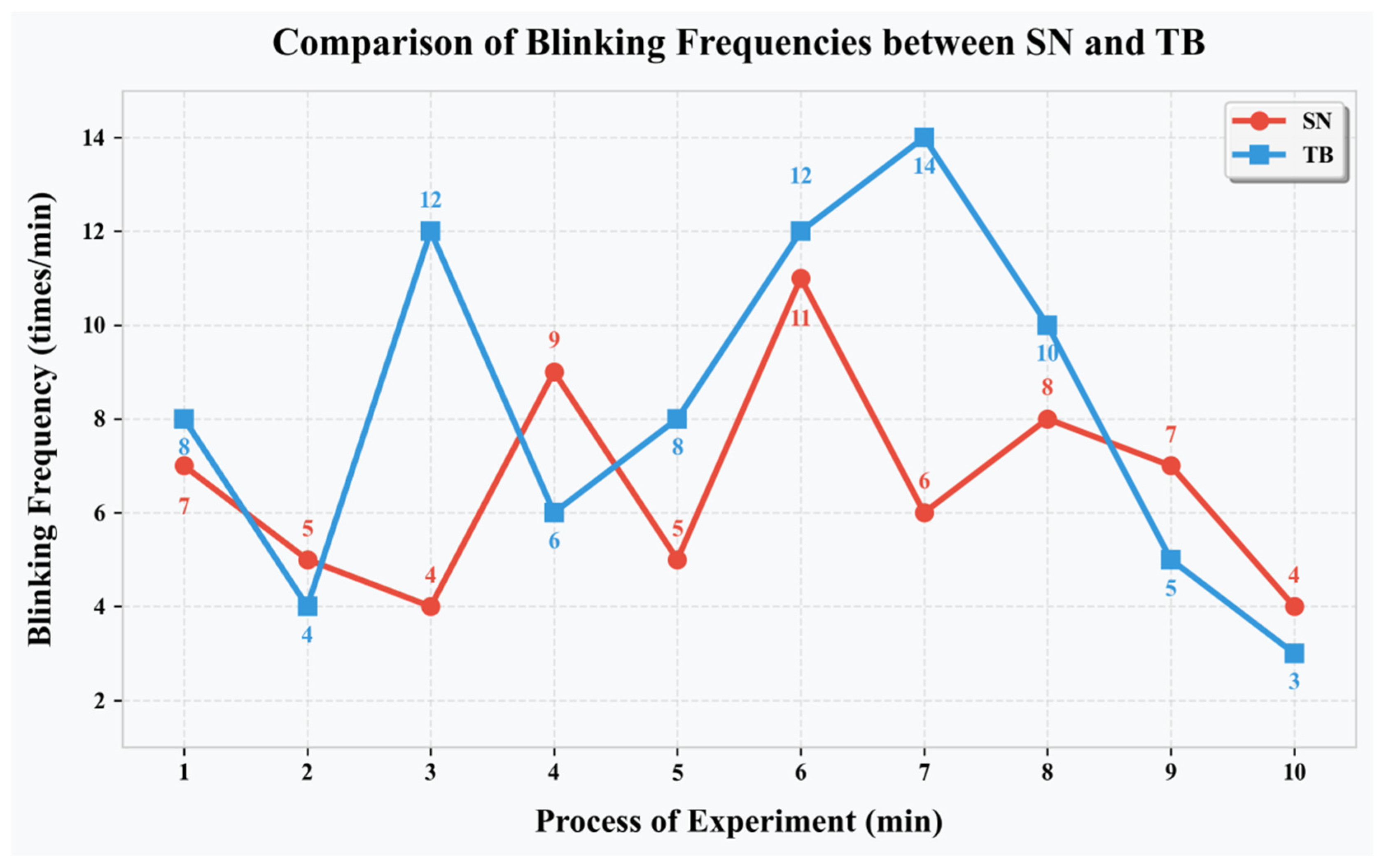

4.2. Quantitative Analysis of Eye Movement Indicators

4.3. Results of the Two Groups in Different Evaluation Dimensions

4.3.1. Test of Validity and Reliability

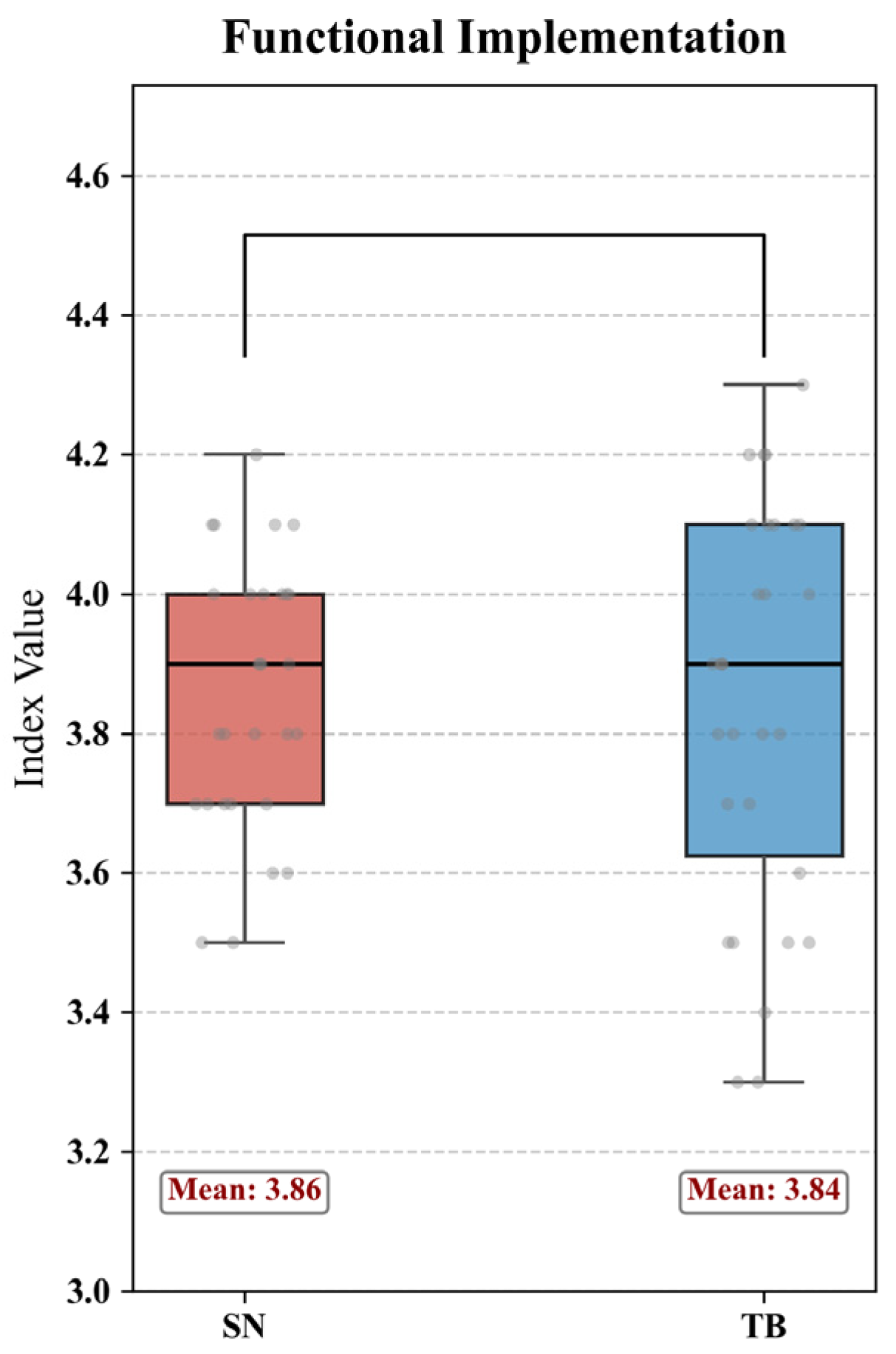

4.3.2. Comparative Analysis of Functional Implementation

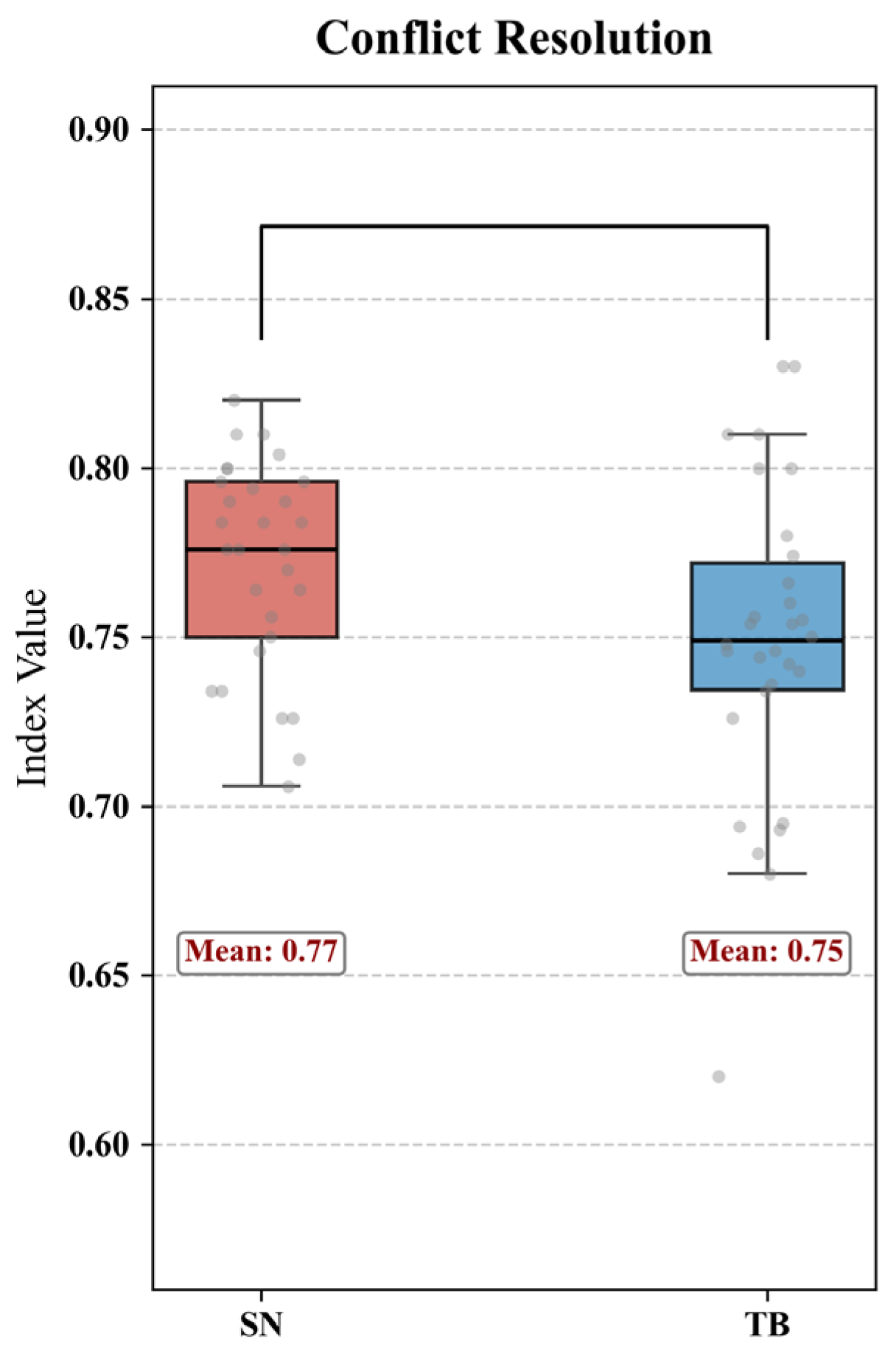

4.3.3. Comparative Analysis of Conflict Resolution

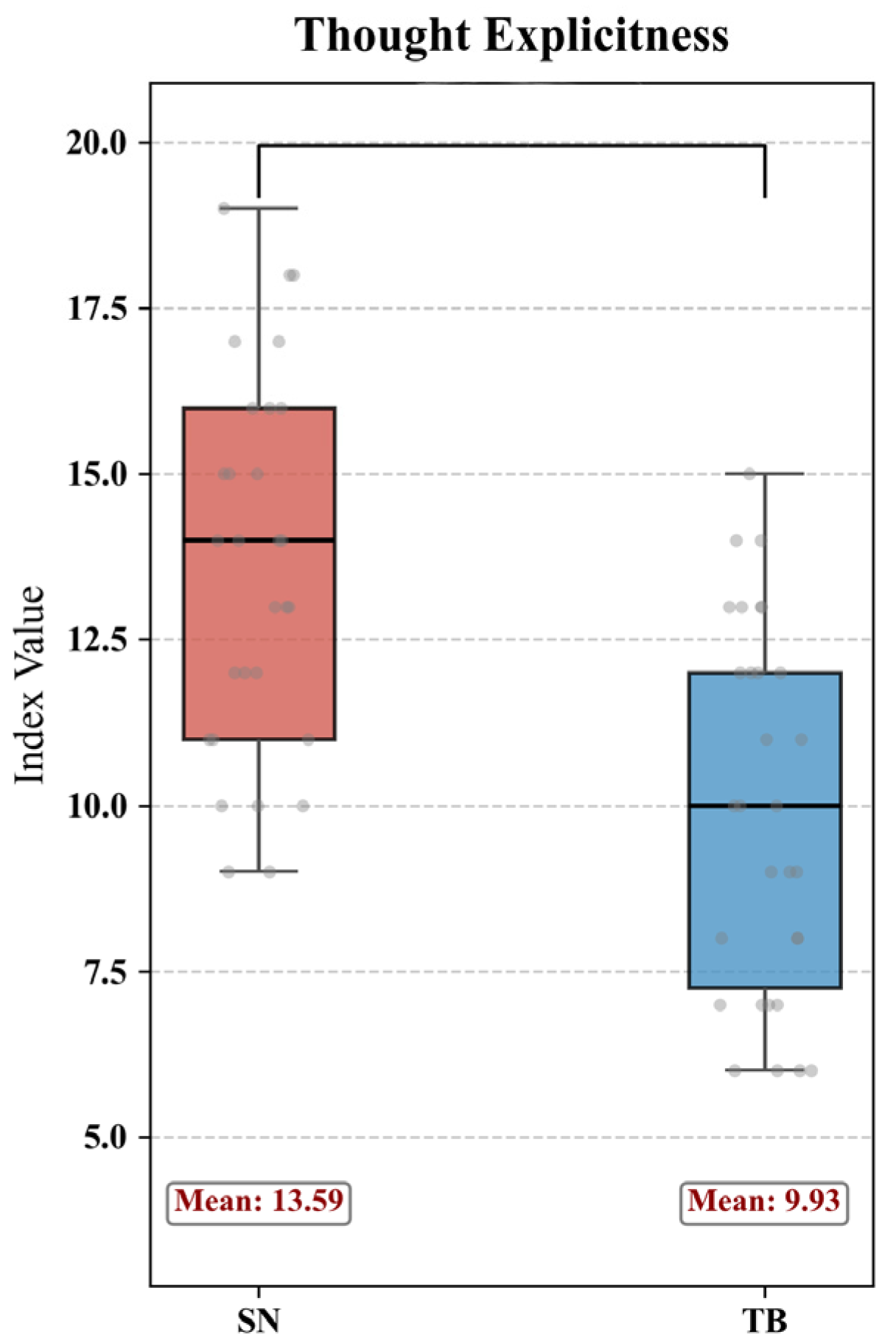

4.3.4. Comparative Analysis of Thought Explicitness

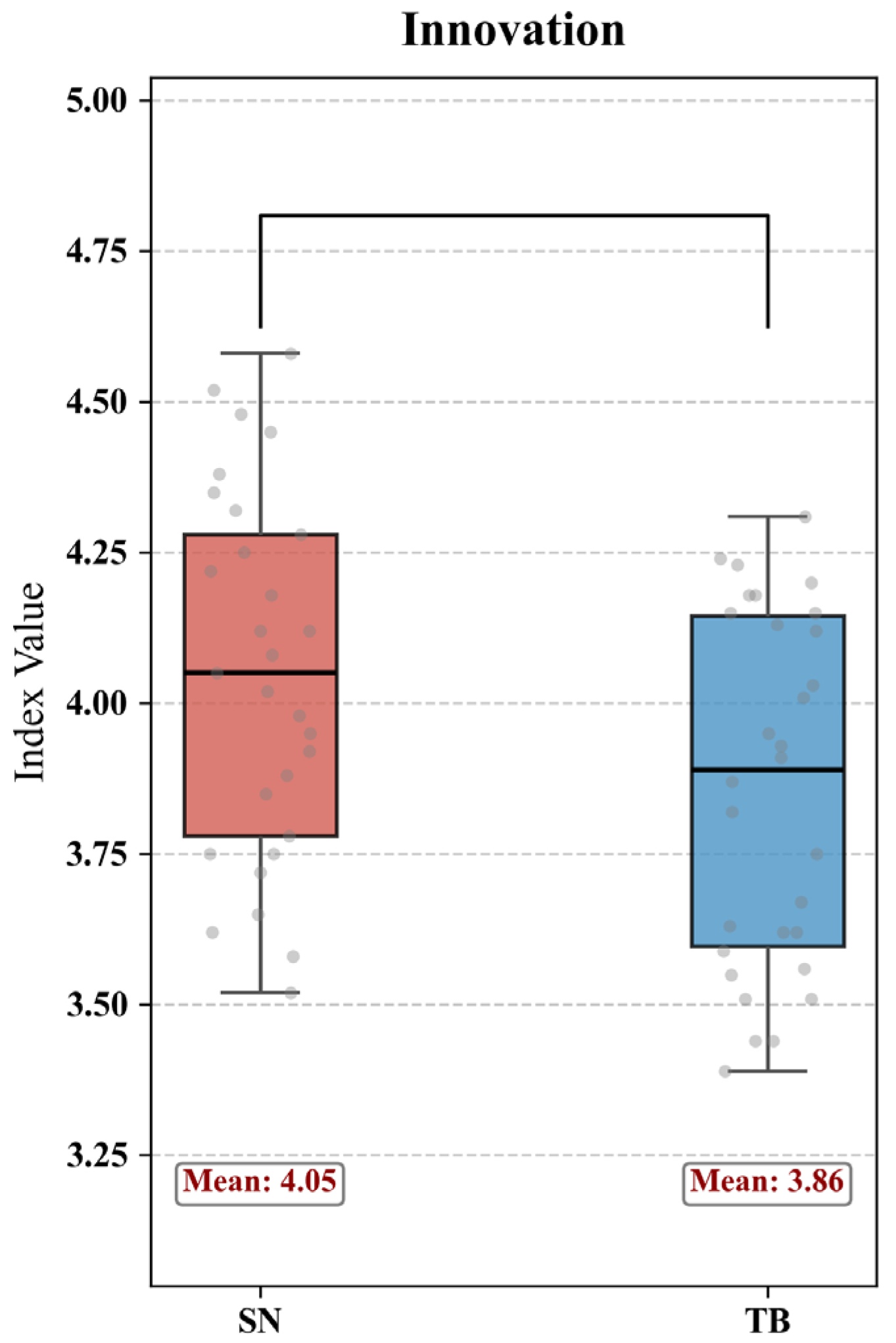

4.3.5. Comparative Analysis of Innovation

- (1)

- SN group representative innovation: A participant decomposed the “4 m road width constraint” and “pedestrian–vehicle conflict” into core nodes, then introduced cross-domain nodes from “traffic engineering” (dynamic lane allocation) and “landscape design” (semi-permeable green belts). The solution involved a dumbbell-shaped road widening at key sections (3 m to 5 m) and sensor-controlled movable bollards that separate pedestrian and vehicle flows during peak hours, while integrating the bollards with landscape plants to maintain spatial openness. This scheme was rated highly for novelty and effectiveness by experts, as it addressed multiple conflicts without increasing land use.

- (2)

- TB group representative innovation: Most solutions focused on local adjustments, such as shifting the cultural center entrance slightly or adding signposts for pedestrian guidance. For example, one participant proposed a curved pedestrian path along the road edge to avoid vehicle interference, which was rated moderately for novelty and effectiveness due to its reliance on conventional spatial adjustment without cross-domain breakthroughs.

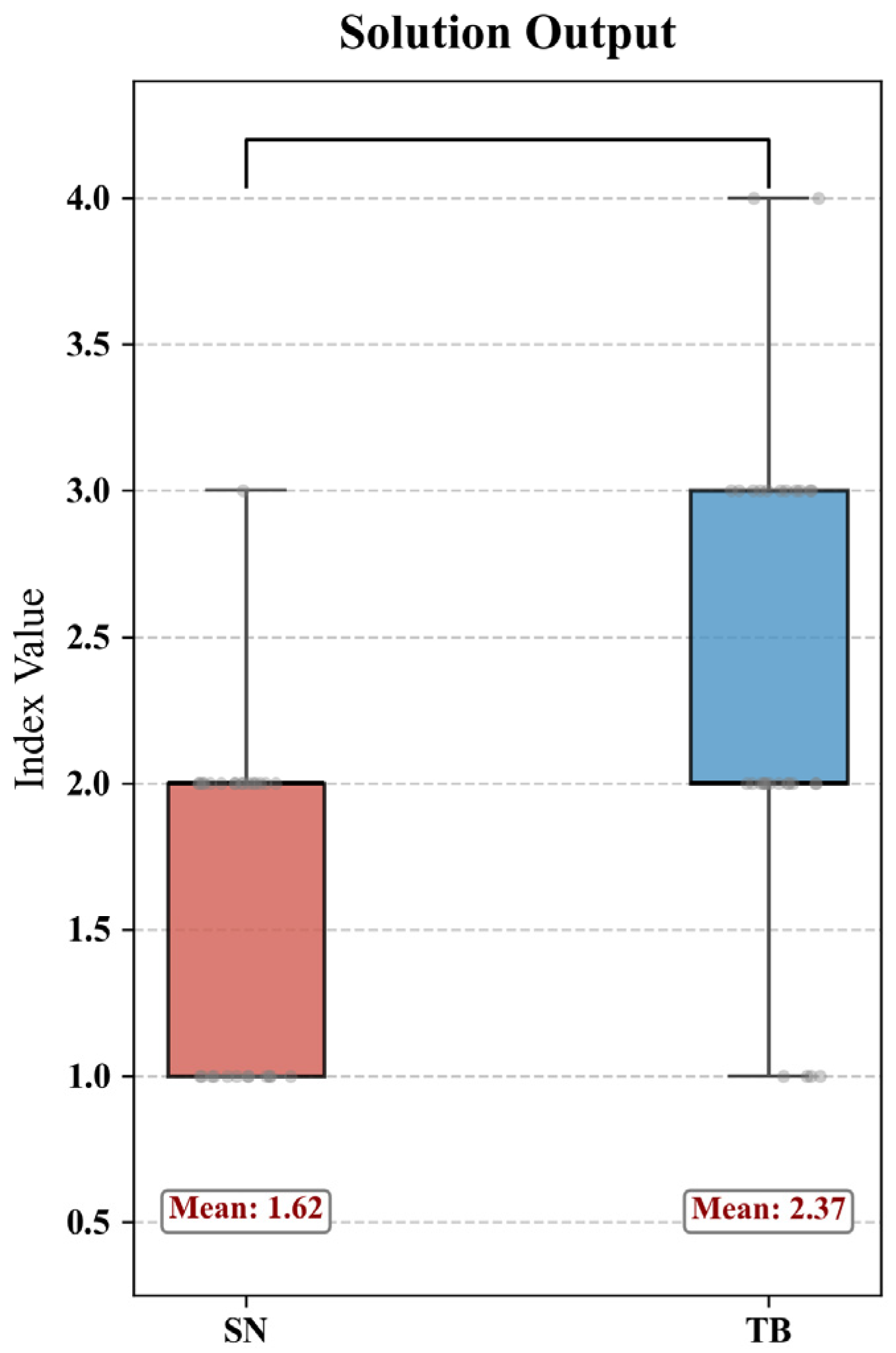

4.3.6. Comparative Analysis of Solution Output

- (1)

- SN group output: Each participant generated 1–2 focused solutions with complete logical chains. For instance, a participant’s solution included three core modules: “constraint node (4 m road) → conflict node (peak congestion) → solution node (time-sharing access + sensory guidance)”, with detailed descriptions of node relationships and implementation paths.

- (2)

- TB group output: Participants generated 2–3 solutions with broader coverage but shallower depth. For example, one participant proposed “entrance relocation”, “road narrowing on one side”, and “pedestrian overpass” within 10 min. However, the “pedestrian overpass” scheme lacked cost and land use considerations, and the “road narrowing” scheme conflicted with fire access requirements. Although the number of proposals appeared to be higher, their actual innovation level was lower than that in the SN group.

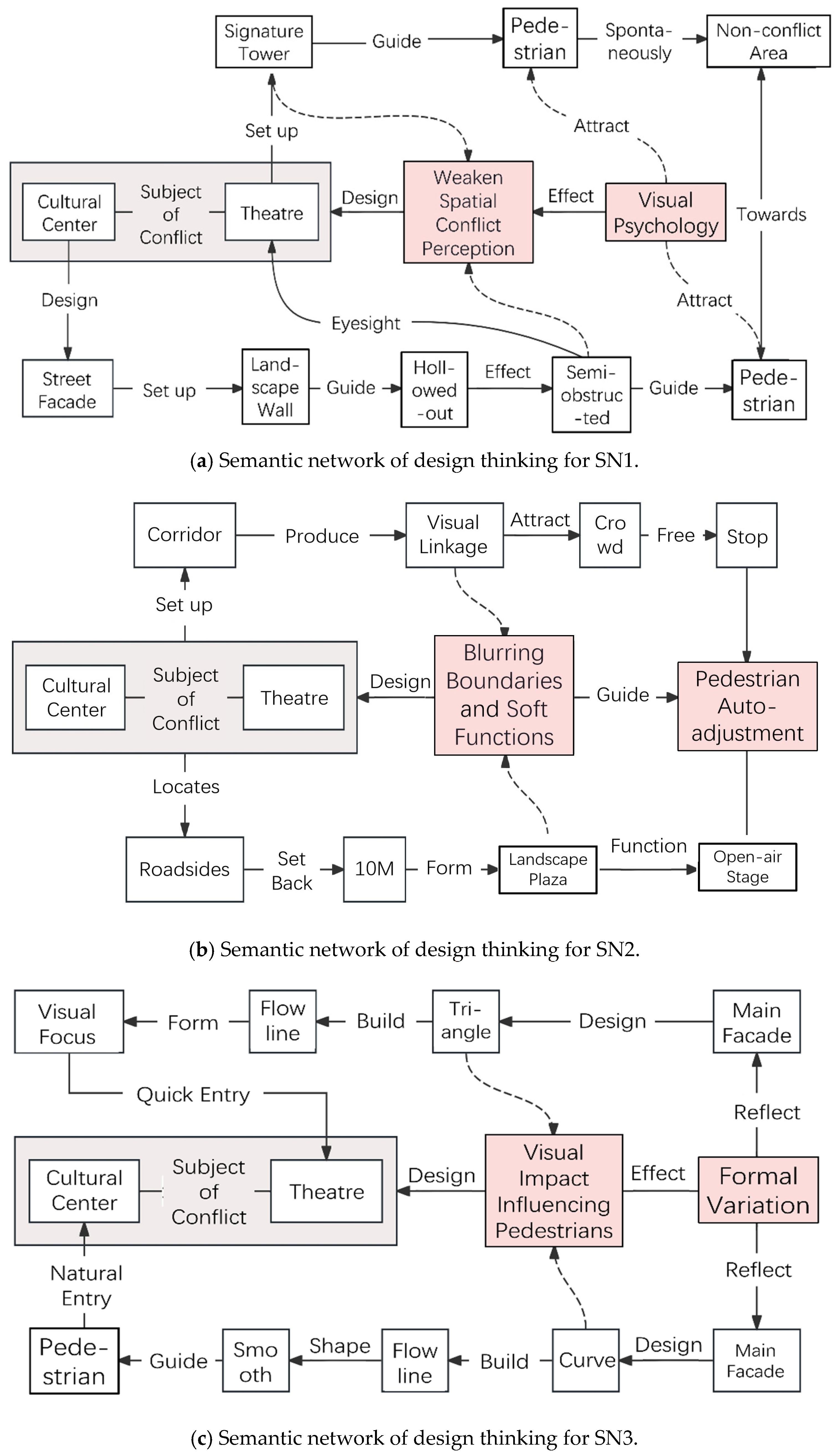

4.4. Design Thinking Deduction Path of Different Individuals in SN Group

4.4.1. Common Cognitive Framework

- (1)

- Unified essence recognition in SN1–SN5 precisely identifies the conflict’s root cause as “the 4 m wide single roadway with dual building entrances/exits,” categorizing it into three distinct dimensions: pedestrian traffic congestion, spatial flow entanglement, and dynamic–static zone conflicts. Crucially, they avoid attributing road narrowing to excessive building volume or traffic chaos to user behavior. This consistency stems from design constraints: fixed roadway width and restricted access locations inherently dictate the singular core direction for conflict resolution.

- (2)

- Implicit consensus on objective constraints, though not explicitly stated, is embedded in the aforementioned individual design philosophies. These principles—preserving cultural facilities ‘openness, avoiding excessive land use, and implementing low-cost solutions—aim to resolve conflicts rather than forcibly fragment spaces. Alternative approaches eschew physical barriers like walls or enclosed partitions that would restrict openness. Instead, they prioritize minor renovations over large-scale demolitions, align with limited budgets, and bypass complex urban signage systems. By leveraging users’ familiar sensory logic (e.g., audiovisual cues), these designs demonstrate a strong emphasis on local context.

- (3)

- The design approach for resolving logical closed-loop commonalities in SN1–SN5 follows a closed-loop logic of “contradiction identification → strategy derivation → design implementation → effect validation”. The process first identifies “what cannot be done” before deducing “what can be done”. After implementation, each solution is validated to address three types of sub-contradictions, ensuring the scheme’s integrity.

4.4.2. Divergent Thinking: Strategic Path Dimensions

- (1)

- The core strategic differences in conflict resolution categorize SN1–SN5 design philosophies into two major schools: Spatial Reconstruction and Sensory Guidance. Their fundamental distinctions lie in conflict resolution approaches: The Spatial Reconstruction School initiates through physical space transformation, resolving conflicts via spatial morphology adjustments. SN2 expands outward through plaza development and soft space distribution, while SN4 optimizes internal road structures with dumbbell-shaped widening and green belts for physical separation. This approach’s key logic involves altering spatial carriers to make users adapt to optimized environments. The Sensory Guidance School focuses on behavioral cues, directing flows through sensory signals. SN1 employs visual barriers (scenic walls) and directional signage (sign towers) to reduce conflict perception, enabling natural flow. SN3 conveys functional signals through architectural forms, guiding users intuitively. SN5 utilizes natural and artificial soundscapes, along with tactile contrasts between wood and stone, to trigger subconscious behavioral responses, allowing users to autonomously choose paths based on sensory differentiation. This approach’s core logic involves maintaining spatial carriers while using cues to actively avoid conflicts.

- (2)

- In decision-making priorities in design, when balancing spatial efficiency and experiential quality, participants demonstrated distinct preferences. The first priority was efficiency, focusing on addressing functional issues like congestion and safety before considering experience. For SN4, the green belt primarily served as a physical barrier to crowd flow, with landscape value being secondary. The second priority was experience, where SN1’s perforated landscape wall not only controlled foot traffic but also enhanced the entrance ambiance through light effects, while SN5’s acoustic design guided crowd flow and created a tranquil atmosphere via natural water sounds. SN2 adopted a balanced approach, equally emphasizing plaza dispersal and landscape experience, effectively resolving crowd flow issues while providing activity space, achieving equilibrium between functionality and user experience.

5. Discussion

5.1. Analysis of Eye Movement Data Reveals Cognitive Processes in Two Groups

- (1)

- Node Deconstruction Phase (1–4 min)

- (2)

- Cross-domain Association Phase (5–7 min)

- (3)

- Cognitive Integration Phase (8–10 min)

5.2. Discussion on the Intrinsic Cognitive Mechanism of Semantic Networks

5.2.1. The Innovative Advantages of Semantic Networks

5.2.2. The Significance of Simulating and Stimulating Thinking by Semantic Networks

5.2.3. Integrating Methodological Advantages into Architectural Design

5.2.4. The Connection Between Semantic Networks and Existing Practice

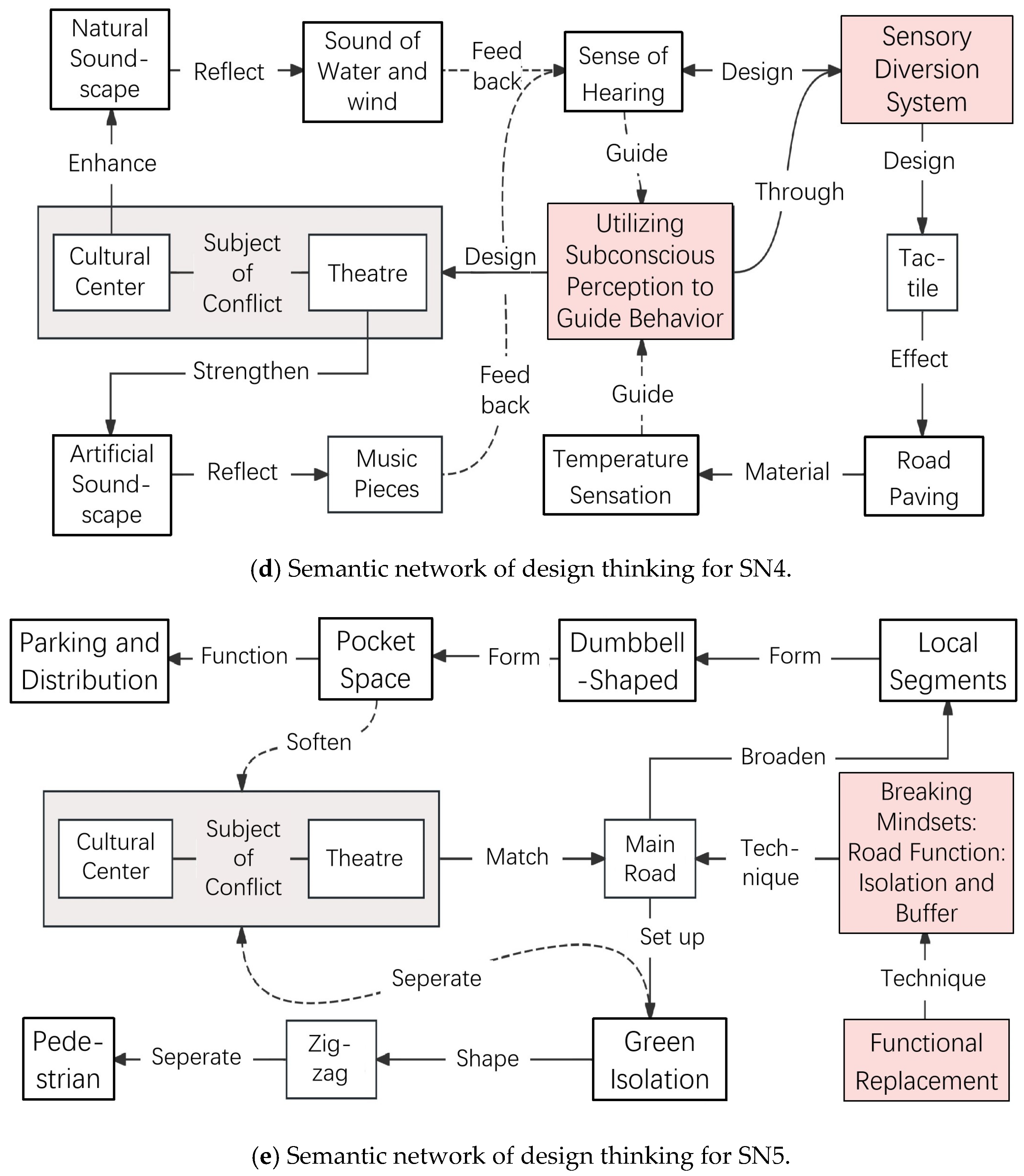

5.3. Practical Extension: Implications for Human–AI Collaborative Design

- (1)

- Structured Input for AIGC: The “conflict–constraint–solution” node–edge structure of SN provides explicit, machine-interpretable cognitive frameworks for AIGC. For example, in the rural cultural center design task, SN decomposes core constraints (4 m road width), conflicts (pedestrian–vehicle congestion), and cross-domain solution nodes (traffic engineering strategies) into structured data. This enables AIGC to generate proposals aligned with functional requirements and design logic, avoiding superficial symbolic splicing.

- (2)

- Traceable Thinking for Human–AI Interaction: SN’s explicit node relationship chains (e.g., “road width constraint → dynamic lane allocation solution”) record the evolution of design thinking. When AIGC generates initial schemes, designers can use SN to trace the logical connections between AI-generated elements, modify conflicting nodes, and optimize solution paths, overcoming the “black-box” limitation of AIGC.

- (3)

- Synergy with Experimental Findings: The eye-tracking data in this study show that SN enhances cross-domain association and logical integration, which aligns with the demand for structured cognitive support in human–AI collaboration. SN’s ability to make implicit thinking explicit complements AIGC’s strengths in rapid idea generation, forming a “human–SN–AIGC” collaborative model: designers use SN to define core constraints and logical frameworks, AIGC expands creative possibilities within the framework, and SN further optimizes and verifies the feasibility of AI-generated ideas.

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Grobman, Y.J.; Weisser, W.; Shwartz, A.; Ludwig, F.; Kozlovsky, R.; Ferdman, A.; Perini, K.; Hauck, T.E.; Selvan, S.U.; Saroglou, S.; et al. Architectural Multispecies Building Design: Concepts, Challenges, and Design Process. Sustainability 2023, 15, 15480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Touny, A.S.; Ibrahim, A.H.; Mohamed, H.H. An Integrated Sustainable Construction Project’s Critical Success Factors (ISCSFs). Sustainability 2021, 13, 8629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Labuda, I.; Dzwierzynska, J. Inventive Methods in Conceptual Architectural Design. Educ. Sci. 2026, 16, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahmawati, Y.; Pradipto, E.; Mustaffa, Z.; Saputra, A.; Mohammed, B.S.; Utomo, C. Enhancing Students’ Competency and Learning Experience in Structural Engineering through Collaborative Building Design Practices. Buildings 2022, 12, 501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boonyoung, N.; Kamonmarttayakul, K.; Phumdoung, S. Comparison of Modified Hybrid Brainstorming with a Conventional Brainstorming Program to Enhance Nurses’ Innovative Idea Generation. J. Contin. Educ. Nurs. 2021, 52, 72–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Awamleh, Z. Behaviour setting transformation methodology, filling in the gaps of the conventional architectural design process. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. B Biol. Sci. 2024, 379, 20230292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zuo, H.; Jing, Q.; Song, T.; Sun, L.; Childs, P.; Chen, L. WikiLink: An Encyclopedia-Based Semantic Network for Design Creativity. J. Intell. 2022, 10, 103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yuan, S.-T.D.; Hsieh, P.-K. Using association reasoning tool to achieve semantic reframing of service design insight discovery. Des. Stud. 2015, 40, 143–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calvillo, D.P. Rapid recollection of foresight judgments increases hindsight bias in a memory design. J. Exp. Psychol. Learn. Mem. Cogn. 2013, 39, 959–964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seeber, I.; de Vreede, G.J.; Maier, R.; Weber, B. Beyond Brainstorming: Exploring Convergence in Teams. J. Manag. Inf. Syst. 2017, 34, 939–969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maksoud, A.; Elshabshiri, A.; Alzaabi, A.S.H.H.; Hussien, A. Integrating an Image-Generative Tool on Creative Design Brainstorming Process of a Safavid Mosque Architecture Conceptual Form. Buildings 2024, 14, 843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paulus, P.; Nakui, T. Facilitation of group brainstorming. In The IAF Handbook of Group Facilitation; Schuman, S., Ed.; Jossey-Bass: San Francisco, CA, USA, 2005; pp. 103–114. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, M.; Shealy, T.; Milovanovic, J.; Gero, J. Neurocognitive feedback: A prospective approach to sustain idea generation during design brainstorming. Int. J. Des. Creat. Innov. 2022, 10, 31–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peirce, C.S. Collected Papers of Charles Sanders Peirce; Harvard University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1974. [Google Scholar]

- Quillan, M.R. Semantic Memory. In Semantic Information Processing; Minsky, M., Ed.; The MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1968. [Google Scholar]

- Gero, J.S.; Jiang, H.; Williams, C.B. Design cognition differences when using unstructured, partially structured, and structured concept generation creativity techniques. Int. J. Des. Creat. Innov. 2013, 1, 196–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheligeer, C.; Yang, J.; Bayatpour, A.; Miklin, A.; Dufresne, S.; Lin, L.; Bhuiyan, N.; Zeng, Y. A Hybrid Semantic Networks Construction Framework for Engineering Design. J. Mech. Design 2022, 145, 041405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carlgren, L.; Elmquist, M.; Rauth, I. Design Thinking: Exploring values and effects from an innovation capability perspective. Des. J. 2014, 17, 403–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, F.; Jia, X.; Zhao, X.; Li, J. A Method for Inspiring Radical Innovative Design Based on Cross-Domain Knowledge Mining. Systems 2024, 12, 102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, B.; Hu, J.; Zeng, J.; Wang, R. Traffic Safety Improvement via Optimizing Light Environment in Highway Tunnels. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 8517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beaty, R.E.; Silvia, P.J. Why do ideas get more creative across time? An executive interpretation of the serial order effect in divergent thinking tasks. Psychol. Aesthet. Creat. Arts 2012, 6, 309–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jang, S.H.; Oh, B.; Hong, S.; Kim, J. The effect of ambiguous visual stimuli on creativity in design idea generation. Int. J. Des. Creat. Innov. 2018, 7, 70–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toh, C.A.; Miller, S.R. Choosing creativity: The role of individual risk and ambiguity aversion on creative concept selection in engineering design. Res. Eng. Des. 2016, 27, 195–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taura, T.; Yamamoto, E.; Fasiha, M.Y.N.; Goka, M.; Mukai, F.; Nagai, Y.; Nakashima, H. Constructive simulation of creative concept generation process in design: A research method for difficult-to-observe design-thinking processes. J. Eng. Des. 2012, 23, 297–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, Y.; Benami, O. Creative patterns and stimulation in conceptual design. Artif. Intell. Eng. Des. Anal. Manuf. 2010, 24, 191–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, X.; Li, Z. Use of electroencephalography (EEG) for comparing study of the external space perception of traditional and modern commercial districts. J. Asian Archit. Build. Eng. 2020, 20, 840–857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Wang, S.; Xu, M. The Function of Color and Structure Based on EEG Features in Landscape Recognition. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 4866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Z.Q.; Liu, L.; Xu, Z. A review on evaluation methods of creative thinking. Adv. Psychol. Sci. 2019, 9, 165–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Yang, L.; Wang, T.; Xiao, R.; Song, L.; Xie, W.; Wang, Z.; Wu, Y.; Su, R.; Ma, H.; et al. Structured diary introspection training: A kind of critical thinking training method can enhance the Pro-C creativity of interior designers. Think. Ski. Creat. 2024, 52, 101–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, M.X.; Li, F.L.; Chang, H.M. Hotspots and trends in critical thinking research over the past two decades: Insights from a bibliometric analysis. Heliyon 2023, 9, e16934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kerimbayev, N.; Nurym, N.; Akramova, A.; Abdykarimova, S. Educational Robotics Develpoment of Computational thinking in collaborative online learning. Educ. Inf. Technol. 2023, 28, 14987–15009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tang, Z.; Wang, Y.; Chen, W. Assessment and Application of Multi-Source Precipitation Products in Cold Regions Based on the Improved SWAT Model. Remote Sens. 2024, 16, 4132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bassier, M.; Vermandere, J.; Geyter, S.D.; Winter, H.D. GEOMAPI: Processing close-range sensing data of construction scenes with semantic web technologies. Autom. Constr. 2024, 158, 105454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Randall, C.; Lawrence, S. Psychometric Properties of Four 5-Point Likert Type Response Scales. Educ. Psychol. Meas. 1987, 47, 27–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, A.K.; Pardheev, C.G.V.S.; Choudhuri, S.; Das, S.; Garg, A.; Maiti, J. A novel classification approach based on context connotative network (CCNet): A case of construction site accidents. Expert Syst. Appl. 2022, 202, 117281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, D.; Onstein, E.; La Rosa, A.D. A Semantic Approach for Automated Rule Compliance Checking in Construction Industry. IEEE Access 2021, 9, 129648–129660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, L.; Kenett, Y.N.; Zhuang, K.; Sun, J.; Chen, Q.; Qiu, J. Connector hubs in semantic network contribute to creative thinking. J. Exp. Psychol. Gen. 2025, 154, 391–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mullen, B.; Johnson, C.; Salas, E. Productivity loss in brainstorming groups: A meta-analytic intSNration. Basic. Appl. Soc. Psychol. 1991, 12, 3–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Irakleous, P.; Christou, C.; Pitta-Pantazi, D. Mathematical imagination, knowledge and mindset. ZDM Math. Educ. 2021, 54, 97–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demirkan, H.; Afacan, Y. Assessing creativity in design education: Analysis of creativity factors in the first-year design studio. Des. Stud. 2011, 33, 262–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldschmidt, G.; Smolkov, M. Variances in the impact of visual stimuli on design problem solving performance. Des. Stud. 2006, 27, 549–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Obamiro, K.; Jessup, B.; Allen, P.; Baker-Smith, V.; Khanal, S.; Barnett, T. Considerations for Training and Workforce Development to Enhance Rural and Remote Ophthalmology Practise in Australia: A Scoping Review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 8593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, A.; Lu, S. Functional design framework for innovative design thinking in product development. CIRP J. Manuf. Sci. Technol. 2020, 30, 105–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.L.; Fu, B.; Li, L.Q. Design and Function Realization of Nuclear Power Inspection Robot System. Robotica 2020, 39, 165–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magistretti, S.; Bianchi, M.; Calabretta, G.; Candi, M.; Dell’eRa, C.; Stigliani, I.; Verganti, R. Framing the multifaceted nature of design thinking in addressing different innovation purposes. Long Range Plan. 2021, 55, 102163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Danko, D.G.; Georgi, V.G. Dynamic semantic networks for exploration of creative thinking. AI EDAM 2024, 38, e12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.D.; Li, J.Q.; Che, X.; Wu, E.H. Cross-supervised semantic segmentation network based on differentiated feature extraction. J. Softw. 2025, 36, 5851–5870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abraham, A. Creativity or creativities? Why context matters. Des. Stud. 2021, 78, 101060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silvia, P.J. Review of Group genius: The creative power of collaboration. Psychol. Aesthet. Creat. Arts 2007, 1, 254–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schotter, E.R.; Leinenger, M. Reversed preview benefit effects: Forced fixations emphasize the importance of parafoveal vision for efficient reading. J. Exp. Psychol. Hum. Percept. Perform. 2016, 42, 2039–2067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Orchard, L.N.; Stern, J.A. Blinks as an index of cognitive activity during reading. Integr. Physiol. Behav. Sci. 1991, 26, 108–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hugo-Burrows, M. Converting tacit knowledge into explicit knowledge in organisations. Commun. J. Commun. Stud. Afr. 2022, 21, 61–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, D.W.; Berry, P.C.; Block, C.H. Does Group Participation When Using Brainstorming Facilitate or Inhibit Creative Thinking? Adm. Sci. Q. 1958, 3, 23–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aeschbach, S.; Mata, R.; Wulff, D.U. Measuring individual semantic networks: A simulation study. PLoS ONE 2025, 20, e0328712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shi, G.; Zhang, Z.; Gao, D.; Lin, J.; Xie, X.; Liu, D. Knowledge-guided semantic computing network. Neurocomputing 2021, 426, 70–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Dimension | Semantic Network Simulation | Traditional Brainstorming |

|---|---|---|

| Core Definition | A cognitive tool that deconstructs design problems into conceptual nodes and stimulates innovation through cross-domain associations and relationship optimization. | A creative method that generates ideas through free discussion and sketching in a non-judgmental environment, prioritizing quantity and diversity. |

| Working Mechanism |

|

|

| Key Characteristics | Structured and explicit thinking. High innovation depth. Strong conflict resolution capability. Moderate efficiency in scheme output. | Unstructured and implicit thinking. Wide innovation breadth. Weak systematic conflict resolution. High efficiency in scheme output. |

| SN Simulation Step | Equivalent Standard Design Workflow | Key Architectural Behavior |

|---|---|---|

| Node Extraction | Design Problem Analysis and Constraint Identification | Listing site conditions, code requirements, and core contradictions (standard in conceptual design). |

| Relationship Mapping | Scheme Logic Sorting | Organizing the causal relationship between spatial strategies and design goals. |

| Cross-domain Association | Interdisciplinary Collaboration Integration | Referencing non-architectural technologies for spatial solutions. |

| Scheme Derivation | Conceptual Semantic Network Sketch | Translating logical relationships into draft (core design output). |

| Stage | Class | TB Group Requirements | SN Group Requirements |

|---|---|---|---|

| Process stage | Program design | Individual independent ideas (identify the core conflict to be resolved) | Individual independent ideas (identify the core conflict to be resolved) |

| Export phase | Outcome requirements | The necessity of hand-drawn sketches and oral expression | Drawing semantic network thinking structure diagram and sketch to assist explanation |

| Program narrative | Describe in words or speech the conflicts and thinking points of each solution | Mark the resolved contradiction nodes, relationship chains, and other information in the network |

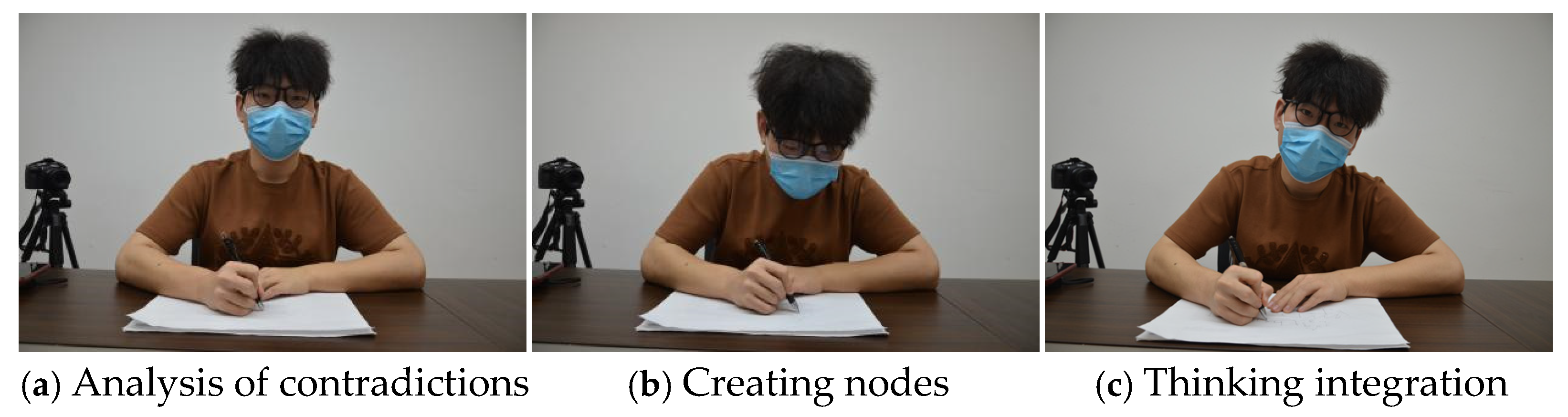

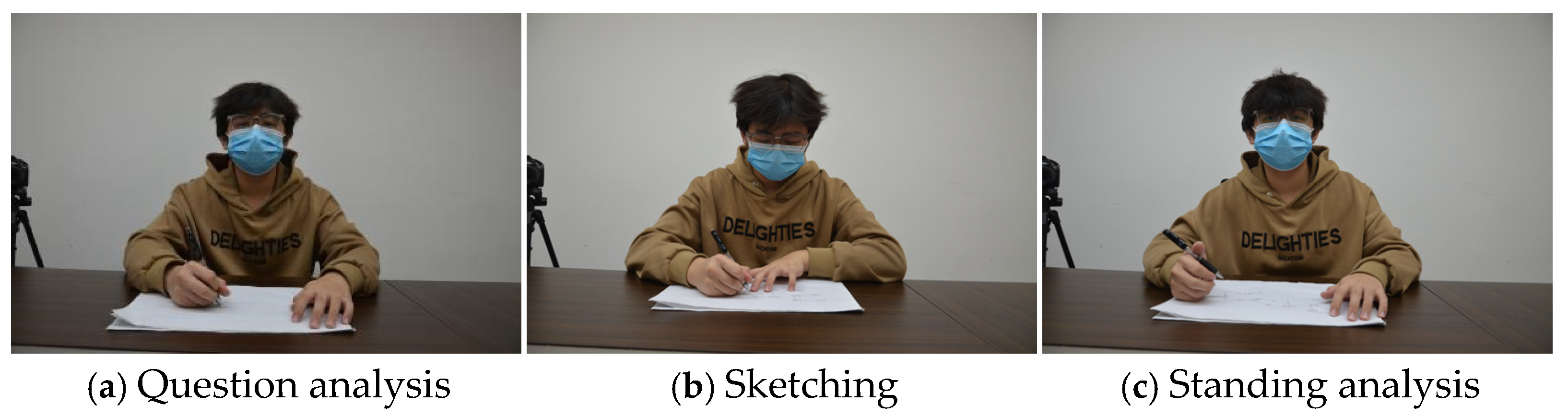

| Group | Cognitive Characteristics | Corresponding Period |

|---|---|---|

| SN group | Analysis of contradictions | 1–2 min |

| Creating nodes | 3–4 min | |

| Knowledge reorganization | 5–6 min | |

| Thinking integration | 7–8 min | |

| Standing analysis | Other time | |

| TB group | Question analysis | 1–2 min |

| Sketching | 3–5 min | |

| Details improved | 6–8 min | |

| Standing analysis | Other time |

| Minute | Average Fixation Duration (ms) | Pupil Diameter Change Rate (%) | Blinking Frequency (Times/min) | Cognitive Characteristics | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SN | TB | SN | TB | SN | TB | SN | TB | |

| 1 | 290 | 280 | +12 | +10 | 7 | 8 | Problem analysis | Analysis of the topic |

| 2 | 410 | 380 | +18 | +14 | 5 | 4 | Identifying core conflict | Analyze functional requirements |

| 3 | 420 | 340 | +22 | +16 | 4 | 12 | Create key nodes | Sketch concept |

| 4 | 410 | 380 | +25 | +15 | 9 | 6 | Node relationship thinking | Sketching |

| 5 | 430 | 360 | +28 | +20 | 5 | 8 | Cross-domain links | Compare sketch schemes |

| 6 | 445 | 420 | +24 | +13 | 11 | 12 | Standing analysis | Details deepen |

| 7 | 460 | 360 | +26 | +18 | 6 | 14 | Knowledge reconstruction | Standing analysis |

| 8 | 420 | 355 | +21 | +15 | 8 | 10 | Optimizing details | Description perfected |

| 9 | 380 | 330 | +15 | +16 | 7 | 5 | Final program review | Feasibility assessment |

| 10 | 310 | 285 | +10 | +9 | 4 | 3 | Outputs | Outputs |

| Bimodal Mixing/Random Consistence | ICC Group Correlation Coefficient | 95% CI |

|---|---|---|

| Single measurement ICC (C, 1) | 0.534 | 0.321–0.720 |

| Average ICC (C, K) | 0.775 | 0.587–0.885 |

| Designation | Kappa | Standard Error (Null Hypothesis) | z | p | Standard Error | 95% CI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Consistency of thought explicitization count | 0.892 | 0.035 | 25.49 | <0.001 | 0.033 | 0.825–0.959 |

| KMO Price | 0.838 | |

|---|---|---|

| Bartlett Sphericity Test | Approximate Chi-square | 246.778 |

| df | 6 | |

| p | 0.000 *** | |

| Groupings (Mean ± Standard Deviation) | t | p | Cohen’s d | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SN (n = 30) | TB (n = 30) | ||||

| Functional implementation | 3.86 ± 0.19 | 3.84 ± 0.29 | 0.267 | 0.79 | 0.069 |

| Conflict resolution | 0.77 ± 0.03 | 0.75 ± 0.05 | 2.279 | 0.026 ** | 0.589 |

| Thought explicitness | 13.57 ± 2.79 | 9.93 ± 2.79 | 5.045 | 0.000 **** | 1.303 |

| Innovation | 4.04 ± 0.30 | 3.86 ± 0.29 | 2.466 | 0.017 ** | 0.637 |

| Solution output | 1.60 ± 0.56 | 2.37 ± 0.81 | −4.261 | 0.000 **** | 1.100 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Dong, J.; Wang, Z. Semantic Network Simulation vs. Traditional Brainstorming: Enhancing Architectural Design Conflict Resolution and Innovation. Buildings 2026, 16, 609. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings16030609

Dong J, Wang Z. Semantic Network Simulation vs. Traditional Brainstorming: Enhancing Architectural Design Conflict Resolution and Innovation. Buildings. 2026; 16(3):609. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings16030609

Chicago/Turabian StyleDong, Jun, and Zijia Wang. 2026. "Semantic Network Simulation vs. Traditional Brainstorming: Enhancing Architectural Design Conflict Resolution and Innovation" Buildings 16, no. 3: 609. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings16030609

APA StyleDong, J., & Wang, Z. (2026). Semantic Network Simulation vs. Traditional Brainstorming: Enhancing Architectural Design Conflict Resolution and Innovation. Buildings, 16(3), 609. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings16030609