1. Introduction

The building sector is one of the principal energy consumers, accounting for approximately 30% of the total worldwide consumption [

1]. It contributes significatly to greenhouse gas emissions, with 39% of global pollution [

2]. This motivates researchers and engineers to study alternatives solutions to reduce energy consumption and environmental pollution [

3]. Numerous studies were conducted on buildings’ physics, energy efficiency, and comfort, in order to improving human health, and building‘s environmental impact. However, choosing the most suitable ecological and efficient technologies depends on many criteria. One of the most studied fields are construction materials and their impact on building energy efficiency due to their composition and properties [

4]. But, beyond the materials thermal and hygrometric performance, techno-economic analysis is required for an effective adoption of alternative ecological solutions [

5]. Investment costs, energy returns, sustainability, non-complex implementation procedures, and local availability of materials are the decisive factors [

6,

7].

All of these challenges’ answers can be found in the integration of local and bio-based materials derived from renewable biomass, which generate very few pollutant gases throughout their life cycle [

8,

9]. The use of vegetal fibers stores atmospheric CO

2, providing many advantages in thermal, mechanical, and hygrometric performance [

10,

11]. Significant potential has been observed for enhanced composites with plant fibers, which improve the mechanical stability and reduce shrinkage cracking while simultaneously reducing thermal conductivity. Ghavami et al. [

12] demonstrated that adding 4% of natural fibers to clay soil helps eliminate shrinkage cracking and increases the ductility of the material. However, mechanical efficiency depends heavily on the type of the used fiber. Yetgin et al. [

13] observed that, in the case of straw, high water absorption reduces the density of the material and lead to a decrease in compressive and tensile strength, despite a significant reduction in shrinkage. Other studies [

14] showed an optimal threshold of approximately 1.5% barley straw, which improved compressive strength by 10 to 20% and increased ductility. The effect can become negative at higher fiber contents.

Biobased materials offer higher thermal performance than conventional insulation materials [

15]. The porosity and fibrous composition of the biobased materials reduce heat transfer through walls, promoting summertime thermal comfort by smoothing ambient temperature fluctuations. In addition to their ability to regulate internal humidity despite extreme variation of outdoor humidity, biobased materials absorb and release moisture limiting condensation risks and discomfort [

16]. Aguerata et al. [

17] demonstrated that for 25 cm cob timber-framed walls with 6% fibers, a low thermal conductivity of 0.2 W/m/K ensures a stable indoor environment, although with a possible risk of mold development in cold climate zones with high precipitation. This can be resolved by rain screens or other moisture management solutions. Fekkar et al. [

18] used natural materials derived from argan nutshell waste with different grain sizes and percentages, showing an increase in thermal properties and a slight decrease in flexural strength which remained acceptable. Several studies conducted on raw earth materials confirmed the improvement of thermal comfort [

19] and the reduction in the carbon footprint [

20]. Beyond the good properties of individual materials, the performance of composite systems differs significantly due to interfacial effects and coupled transfer mechanisms. The work of Schade et al. [

21] highlights the importance of investigating material properties, material layout and interface behavior in composite organic–inorganic walls. These composites lead to enhanced performances due to their interfacial interconnections if well-studied [

22].

Condensation phenomenon is a very important issue to address needing analysis in order to define the favorable conditions to its occurrence. It can deteriorate the thermal performance of the envelopes, reduce their durability and promote mold growth in case of accumulation [

23,

24]. Other than materials properties, climate conditions, rain, wind, and solar radiation are the important influencing agents on wall behavior [

25]. The choice of materials and their composition govern the wall’s thermal inertia, thus heat transfer influences vapor migration and moisture accumulation in the wall. It was demonstrated that fiber dosage influences heat and moisture transfer [

26]. Several studies showed that these interconnections, in addition to the microstructure of the bio-based materials, make the behavior of humidity, its diffusivity and accumulation, hard to predict [

27].

Simultaneous study of thermal, hygric, and structural aspects, aiming to optimize the materials’ conception, their compositions, fiber and water content, for a good compromise between insulation, mechanical stability, and hygric regulation, securing the durability and perennity of the constructions. This is the context where this work fits by testing several formulations, measuring and evaluating their thermal and hygrometric performance, and identifying risky scenarios. Bio-based materials made from raw earth and fibers are the subject of this study, where they are used not only as insulation, but also as structural elements and multilayer composites, ensuring thermal comfort, humidity regulation, and mechanical strength. These materials based on cob are a result of the European CobBauge project, a project with the goal of proposing biosourced materials for low environmental impact constructions. Tests were carried out on the developed materials and the different formulations, ending with the selection of the optimal ones, ensuring distinct roles of insulation and mechanical stability. The study also includes the characterization of the response of selected materials when subjected to different temperature and humidity gradients, thereby addressing the question of coupling and reciprocal influence between them. The expected results focus on identifying the safest and efficient configurations from a hygrothermal perspective. This will contribute to a better understanding of the transfer mechanisms in earth and fiber materials and their rational integration into low-carbon construction systems.

2. Cob Context: Preparation and Characterization

This work focuses on the use of a dual-layer cob composite, respecting the structural and thermal performance of buildings and also providing a thinner wall rather than a single thick layer of cob. The first layer, mainly composed of soil and a low percentage of fibers, ensures the structural role of building walls, characterized by its ability to support loads. The second cob layer, characterized by high thermal resistance, uses high percentage of fibers, within 25% to 50%. Various mixes of soils/fibers were tested, integrating different types of fibers such as hemp straw, flax straw, wheat straw, and reed in order to develop the desired materials. The used soils are extracted from Normandy in France and characterized by different distributions of particles’ fraction and size. The diameter of the particles is lower than 2 mm. These soils and fibers were chosen for their availability locally, which is an important criterion for the CobBauge project, reducing transportation, and thus having less environmental impact. Several formulations are studied, with the objective of developing the two materials with the required mechanical and thermal performances. Material selection was guided by several criteria, including compressive strength and thermal conductivity. An important characterization axis is related to the water content influencing the mixes’ ductility. When it increases, the state of the soil changes from fragile, to plastic, to a viscous liquid. Based on the Atterberg’s limits [

28,

29], the liquid limit, which is the transition between the liquid to plastic state, is obtained between 20% and 50%. The plastic limit, which is the transition from the solid to plastic state, is measured between 16% and 28%. The index of plasticity was also determined, ranging from 13% to 20%.

Table 1 shows the different mixes of soil, fibers, and water contents constituting the structural and insulation Cob samples. The preparation procedure of the samples consists of mixing the soil of each sample with water as a first step; this mixture is preserved for 3 days before adding fibers, then kept in 20 ± 2 °C and 50 ± 5% relative humidity one day before molding the samples. They were kept for 2 days in ambient conditions, removed from molds, and put in the oven at a temperature of 40 °C.

2.1. Thermal Properties

A test bench was built in the laboratory with the aim of realizing thermal diffusivity measurements of the several cob mixes. These tests allowed us to identify the influence of fibers’ quantity and distribution in the mixes. Fine instrumentation by micro thermocouples was used to determine local heat transfer for various cob mixes based on Fourier’s law. The test area was thermally insulated, so that heat circulated only through the sample, which was placed between a heating plate at the bottom and a cooling one at the top.

The structural samples had a density ranging between 1107 kg/m

3 and 1583 kg/m

3, which is higher than the insulation samples’ density that is less than 700 kg/m

3, as shown in

Figure 1. This difference can be explained by the difference in fiber content which means a difference in porosity created by the link between the fibers and the soil. As the percentage of fibers increases, more voids in the mixes appear, which explains the light density of the insulation mixes due to their high levels of porosity.

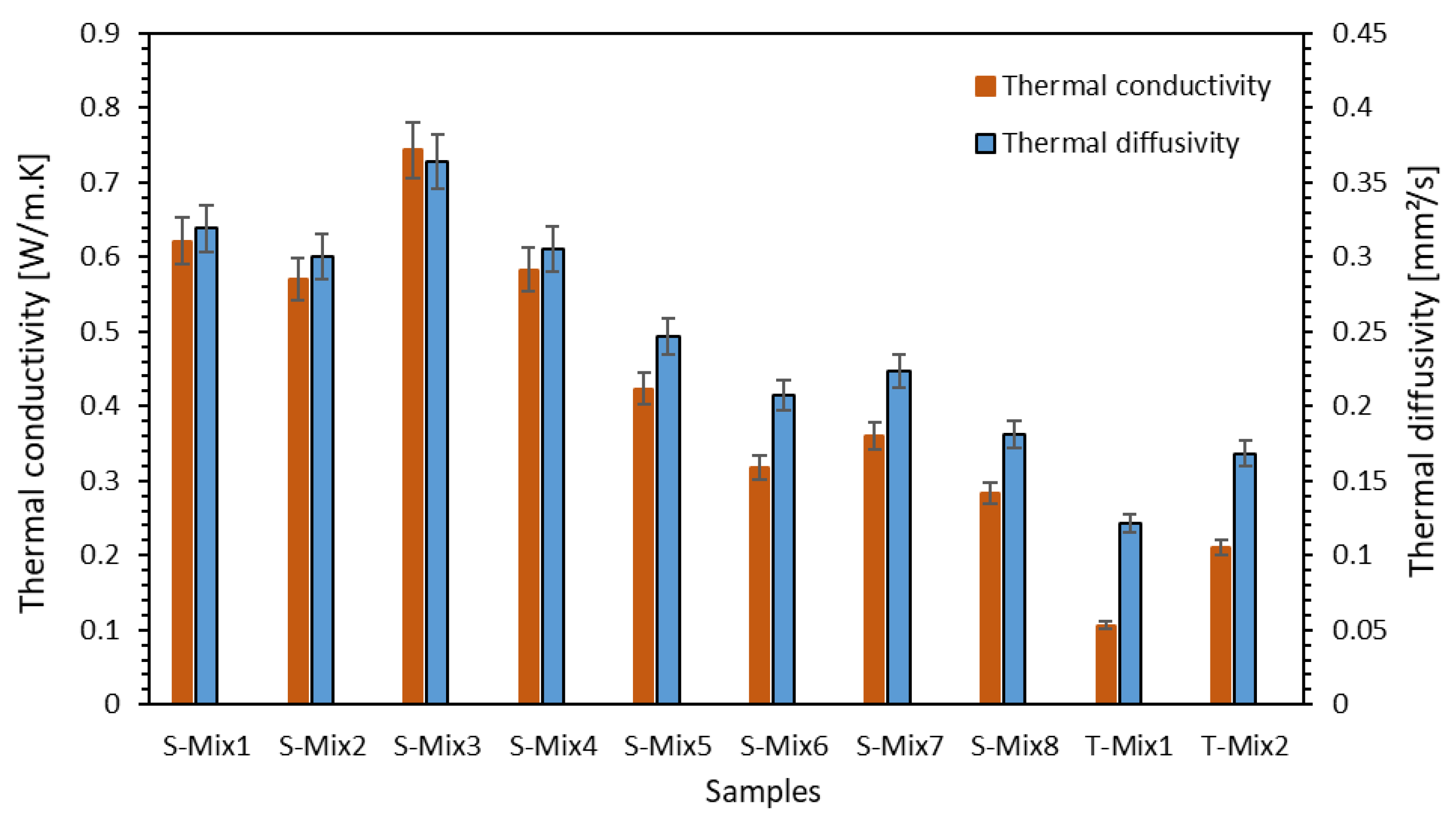

The measured thermal diffusivity and thermal conductivity representing the material‘s dynamic heat transfer from the hot side to the cold one, are shown in

Figure 2. The results highlight a correlation between the mixes’ compositions and their thermal performance. For the structural samples, S-Mix3 represents the highest diffusivity with 0.363 mm

2/s diffusivity, due to its low fiber and water content, promoting a denser and more continuous matrix, thus more thermal conductivity. The mixes with wheat straw are less conductive, as S-Mix8 is the least-conductive structural sample, with 5% fiber content and 31% water content, causing more porosity and thus lower density.

Increasing the number of fibers and decreases thermal conductivity. This demonstrates impact of the integration of vegetable fibers and the trapped air in the pores in the insulation performance. Also, the microstructure and pores connections are modified depending on the type of fibers used. This is confirmed by the insulation samples, characterized by 25% fibers and a significant water content, presenting low thermal conductivity and diffusivity and high specific heat capacity, which is coherent with their role as lightweight insulation materials.

Two samples were selected and used in the rest of this work because of their lowest average thermal conductivity and highest thermal resistance: the structural sample S-Mix8 and insulation sample T-Mix1. The sample S-Mix8 is constituted of French sub-soil, wheat straw fiber content (5%) and water content (31%). The insulation material T-Mix1 is 25% reed and 131.3% water content.

2.2. Environmental Impact and Benefits of Using Raw Earth

The building sector and construction materials are one of the principal sources of CO

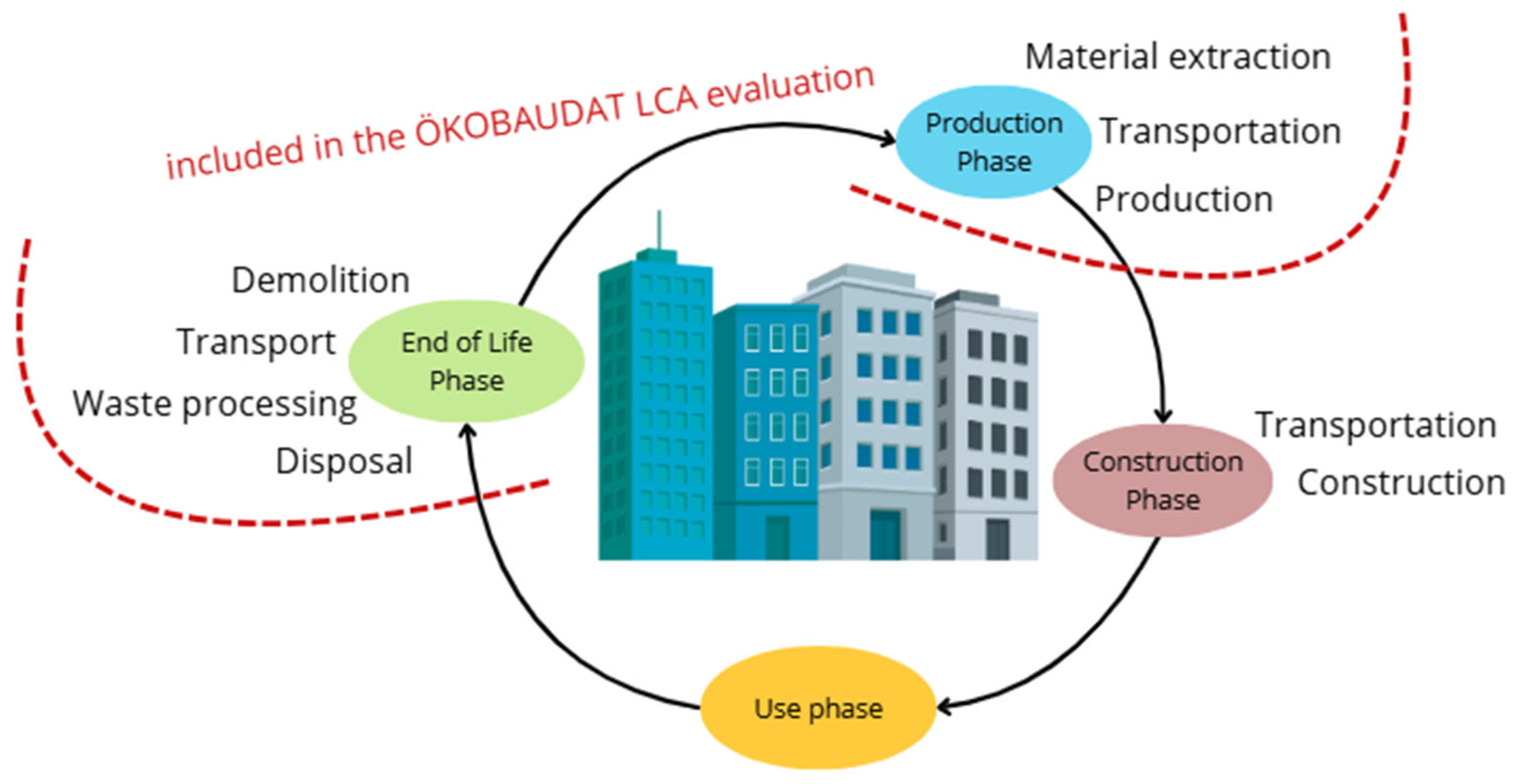

2 emissions. It becomes necessary to define alternative solutions to reduce gas emissions throughout building life cycle, starting from the materials extraction, production process, construction, operation, and finally demolition, waste transport, and treatment (

Figure 3).

The environmental impact evaluation is based on the ÖKOBAUDAT database [

30], a European reference for construction materials and their life cycle. Because the mixes studied in this work are not cited in this reference, equivalent materials were chosen for their physical and structural similarities to determine greenhouse gas emission values approximative to the structural and insulation materials.

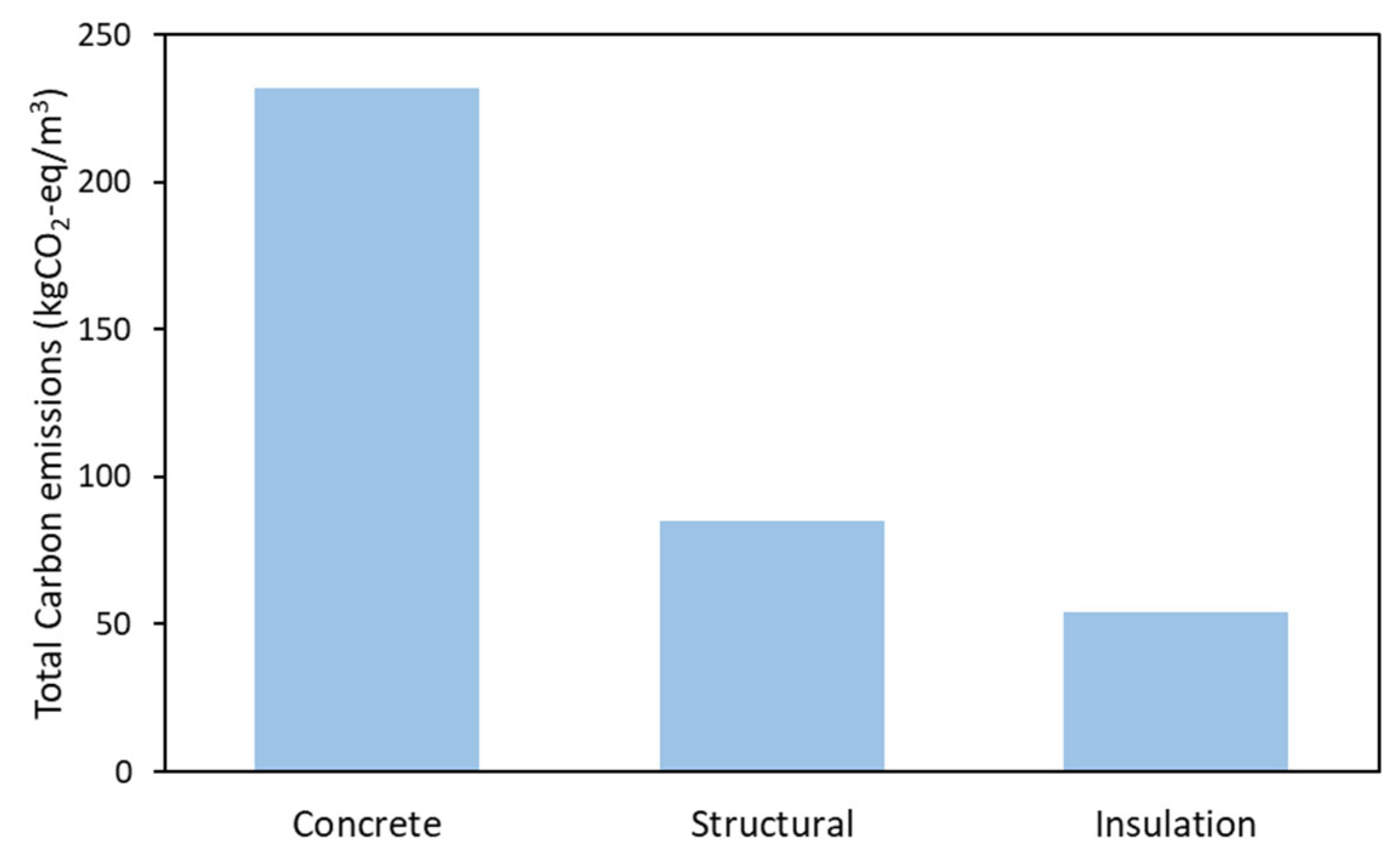

As a comparative reference, building concrete presents total emissions of 0.101 kgCO2-eq/kg, including 0.089 kgCO2-eq/kg for fabrication and 0.013 kgCO2-eq/kg for elimination, as mentioned in the database, which corresponds to approximately 232 kgCO2-eq/m3 for 2300 kg/m3 density. This high carbon impact is due to the fabrication of cement and the embodied energy associated with high-temperature firing.

For the structural material developed in this work, the closest material found in the database was compressed earth blocks. This unfired material has a total climate impact approximative to 0.057 kgCO2-eq/kg, resulting from the fabrication procedure (0.054 kgCO2-eq/kg) and elimination (0.003 kgCO2-eq/kg), which is minimal due to the local availability of raw earth, with very little industrial energy use. When this value is compared to the density of the structural material, a total impact per m3 is estimated to 85 kgCO2-eq/m3, with a reduction of nearly 65% in comparison with concrete.

Figure 3.

Life cycle assessment system boundaries and considered phases based on EN 15804 [

31].

Figure 3.

Life cycle assessment system boundaries and considered phases based on EN 15804 [

31].

The insulation material, mixed with a high percentage of fibers, has a light density matching the lightweight clay brick’s properties (0.180 kgCO2-eq/kg in the database) and a fiber composition close to the straw bale for construction material (0.096 kgCO2-eq/kg). Thus, the insulation material is situated between these two materials, with an estimation of an environmental impact close to 54 kgCO2-eq/m3, representing a reduction of approximately four times in comparison with concrete.

The results in

Figure 4 confirm the environmental benefits of these biosourced materials in terms of reducing CO

2 emissions due to the absence of firing; local availability, needing less transportation; and low embodied energy of the production processes, which demonstrate the growing interest in integrating raw earth materials into construction.

3. Experimental Setup on Moisture Transfer

The literature review shows the importance of using numerical modeling of coupled heat and moisture transfer for the use of bio-based materials in the building. In order to validate these theoretical models, various experimental tests were performed. In this work, experiments to evaluate the water transfer were carried out on 7 cm cubic cob sample enrolled with aluminum tape. This allows for one-dimensional moisture transfer between the two compartments. The samples are dried at first and stabilized in the oven at a fixed temperature of 23 °C. Preconditioning is used to provide the same initial state for all the tests. It relies on leaving the sample in the ambience until the variation in relative humidity inside is less than during 24 h.

The experimental setup is presented in

Figure 5, where four different samples were tested using four cup devices at the same time, allowing for simultaneous testing under identical and controlled ambient temperature and relative humidity. Each device is composed of an upper and a lower compartment, with the biosourced sample placed between both chambers, as shown in

Figure 6. In the upper chamber, the temperature can be regulated through a heating cartridge, while in the lower chamber, the relative humidity can be regulated through the use of various saturated saline solutions presented in

Table 2. The difference in water vapor pressure between the two sides leads to a migration of the vapor from the wet compartment to the dry one. Once the saline solution is introduced, local temperature and relative humidity through the sample are measured until a steady state is reached, which is relative humidity variation of less than 4% for 24 h (as the accuracy of hygrometers is set to

. Each test lasts around 5 days in order to verify the stabilization condition. Each specimen is equipped with embedded temperature sensors and humidity sensors connected to an NI acquisition system, which enables measurements of real-time display and records within a time lap of 600 s. A user LabView interface, as shown in

Figure 5, is developed to display temperature and relative humidity evolution during the tests.

3.1. Samples Instrumentation

The test bench is instrumented as shown in

Figure 6, where 8 hygrometer sensors are used. Two hygrometers are set in the lower and upper surface of the cob mix, and two internal hygrometers are set from each side, with 2 cm depth and 2 cm distance from each other. Eight K-type thermocouples

are instrumented adjacent to each hygrometer to allow for local temperature measurement. In addition, the humidity-controlled room, which is the bottom compartment, is equipped with a glass cup in which the saline solution is introduced, and a hygrometer of

RH is placed to measure the room relative humidity, in addition to a K-type thermocouple

and a pressure transducer HD 9408T (

adjacent to the sample bottom surface to measure pressure. Meanwhile, the temperature-controlled room is equipped with a heat cartridge 25 Ω of

to allow for temperature variation.

3.2. Measurements Reproducibility Verification

The experimental tests were repeated to confirm the reliability of the obtained measurements. The results shown in

Figure 7a,b are the ones obtained in the tests on the structural sample using NaCl solution in the equilibrium state, which was noted in the two compartments after approximately 5 days, in which the ambient relative humidity stabilized at 68% in the bottom ambience RHbottom. Fluctuations were observed in the obtained results, leading to a statistical analysis performed on the stabilized portion of the signal in order to confirm their reliability. The average relative humidity for the sensor RHs2 for the first test was 65.72%, against 66.63% for the second test, with a maximum standard deviation of 1.18%. For RHi2, an average of 56.48% for the first test was calculated, against 57.92% for the second test, with a maximum standard deviation of 3.073%. These fluctuations are consistent with the intrinsic noise level of RH sensors. A smoothing filter was applied to highlight the physical trend and is presented in

Figure 7a. Tests 1 and 2 show a good agreement, with a maximum mean deviation of 3.7% for RH and 0.148 °C for temperature, confirming the reproducibility of the measurement process. The temperature is homogeneous throughout the sample due to the imposed isothermal boundary conditions.

3.3. Impact of Thermal Gradients on Hygric Diffusion: Experimental Results

In order to analyze the influence of temperature on the moisture migration within the material, experimental tests were conducted on the structural material, allowing us to understand and visualize how temperature governs the partial water vapor in the humidity source, monitor the moisture transfer inside the material under the combined effects of temperature and moisture gradients, and investigate the material’s ability to transport moisture.

In the bottom compartment of the experimental setup, saline solution was used to ensure a stable supply of humidity. The solution consists of a mix of 10 mL of water with 30 g of . The temperature in the bottom compartment was controlled, starting with 25 °C and increased with a step of 5 °C. At the top compartment, the temperature was fixed at 25 °C and the relative humidity was not controlled. At each step, an observation and acquisition of measurements of the humidity’s natural diffusion was realized.

The measurements in

Figure 8 for the compartment ambiences highlight the hygrothermal dynamics caused by the imposed conditions. In the lower side, the relative humidity initially increases to approximately 65% as a result of the presence of the saline solution. During the first period of the test (Zone1), with both compartments at the same temperature 25 °C, an increase in relative humidity was also observed in the upper compartment as vapor migrated from the lower compartment and the material gradually desorbed. When the temperature of the lower compartment increases, it causes an increase in saturated vapor pressure in the lower part, leading to a decrease in the relative humidity at the bottom side, and thus RH increased at the top by moisture migration, progressively reversing the RH levels between the two sides, starting from when the temperature at the bottom reaches 35 °C. In the following zones (4 and 5), when the lower temperatures were raised to 40 °C and then 45 °C, the thermal gradients became more pronounced, causing a more marked effect on relative humidity. RH continues to decrease at the bottom, while the vapor at the top side was at a lower temperature, which increases the measured relative humidity. The difference between the two compartments reaches nearly 40%, illustrating an inversed relative humidity gradient, from the top to the bottom, while heat moved from the bottom to the top.

Figure 9 represents the variations in temperature and relative humidity inside and on the surfaces of the sample. The lower surface’s relative humidity increases in the first, due to the source of humidity. While the temperature at the bottom ambience is increased in steps. The measured relative humidity shows a decrease, which can be explained by the increase in the saturated vapor pressure. At 2 cm from the bottom surface, RH increases progressively until it exceeds the measured RH at the bottom surface. As mentioned above, starting from 35 °C, the relative humidity levels in the ambiences reverse, which caused the appearance of maximum RH inside the material, at 2 cm. The area located at 2 cm remains cooler than the lower surface while receiving an increasing amount of vapor, making that its saturated vapor pressure is lower than that of the heated surface. This explains the higher internal relative humidity in this location. At 5 cm, the relative humidity also increases over time, showing the progression of the humidity within the sample, but remains lower than that of the bottom surface. This is due to the distance from the source of moisture and the influence of conditions on the top compartment, which was initially drier. The same trend is followed by the relative humidity measurements in the top surface, with nearly combined curves. However, when the lower temperature reaches 45 °C, there is a slight increase in relative humidity at 5 cm. At this stage, the increase in temperature at the bottom greatly intensifies the moisture migration of vapor through the material, enabling the vapor to reach the 5 cm area more efficiently.

These results show that the studied material acts as a humidity buffer, allowing water vapor migration at a certain rate consistent with its resistance to water vapor diffusion, causing no surface or interstitial condensation in the conditions studied.

Figure 10 and

Figure 11 show that in all of the measured positions, the partial vapor pressure never exceeds the local saturated vapor pressure corresponding to the local temperature, indicating that the water vapor remains in the vapor phase, without transitioning to the liquid phase and condensing.

The overall results clearly show that moisture dynamics in the material are governed by temperature. Despite the bottom surface being the source of humidity, the distribution of the measured relative humidity within the material does not depend solely on the water content introduced but also reflects the evolution of temperature via the saturated water vapor. The moisture starts spreading and gradually increases inside of the material as the temperature at the bottom rises. When the temperature of the heated side increases, the saturated vapor pressure increases, and thus the relative humidity decreases. At the same time, the water vapor is transported to the colder area, increasing its relative humidity, creating reverse gradients and internal location of moisture accumulation. Furthermore, the system never reaches conditions favorable to condensation, as the vapor remains undersaturated in the material.

4. Numerical Modeling

The modeling of hygrothermal behavior is based on the EN ISO 13788 standard [

32], allowing for the observation of the heat and moisture diffusion through materials, making it possible to identify the risks of interstitial condensation. The equations defined in the standard and employed in the present calculations are detailed in

Appendix A.

Temperature and partial water vapor profiles enable the evaluation of interstitial condensation risk, where the temperature profile controls the saturated vapor pressure distribution within the wall and partial water vapor shows the real vapor diffusion. When the partial water vapor exceeds the saturated water vapor at a certain point, a risk of condensation is identified, where the vapor quantity that is present locally exceeds the maximum that the temperature can sustain without condensation.

The boundary conditions adopted are consistent with the standard EN ISO 13788 [

32], where the exterior and interior ambiences resistances are equal, respectively, to 0.04 m

2.K/W and 0.13 m

2.K/W.

4.1. Studied Materials’ Hygrothermal Parameters

The two mixes chosen for this study are based on raw earth, designed for distinct roles in the building’s envelope (

Figure 12). S-Mix8, known as the structural material, ensures mechanical resistance because of its important solid fraction and a reduced porosity. Its thermal conductivity is higher than the second mix T-Mix1, with 2.29 W/m/K against 0.10 W/m/K, which promotes more thermal diffusivity. S-Mix8′s vapor permeability is higher, with 3.35 × 10

−11 kg/m/s/Pa vs. 3.14 × 10

−11 kg/m/s/Pa for T-Mix1, which means that vapor circulates more easily through the structural material. The second mix, T-Mix1, plays the role of insulation, with less density and more porosity due to a higher presence of fibers. Its low thermal conductivity makes it capable of reducing heat loss. In terms of humidity management, its porosity favors an important sorption capacity, allowing it to adsorb and release moisture depending on climatic variations.

4.2. Validation of the Modeling Results

Validation of the capacity of the numerical predictions is conducted basing on the measurements in order to evaluate the wall behavior subjected to the real thermal and hygric gradients. The same experimental indoor and outdoor conditions were considered. The saline solution placed at the base was modeled imposing a relative humidity corresponding to the equilibrium measure obtained in the experimental procedure. The thermal and hygrometric properties of the structural material were used. The numerical calculations were then run for each temperature level imposed at the lower compartment, allowing for a comparison between the model and the experiment.

Figure 13 shows the comparison between the model’s calculated heat flux according to Fourier’s law and the experiment flux obtained from the temperature measurements by the sensors, allowing for the estimation of the real heat flux. Good agreement is observed between the two, with a maximum absolute error of 0.3 W/m

2.

Figure 14 shows that the comparison of the model’s hygric flux and the experimental one also presents good agreement, with a maximum error of 0.06 mg/m

2/s.

For lower and upper compartments of 25 °C, there is an important hygric flux due to the important humidity gradient, with a gap of 29% between both ambiences. However, for the lower compartment temperature of 30 °C, temperature gradient occurs inside the material, and the top RH increase is observed at the same time, due to the moisture diffusivity, as mentioned in the experimental section. This explains why, at 30 °C, the moisture flux is close to that of 25 °C, as the slight increase in temperature is compensated by the reduction in the humidity gradient. From 35 °C to 45 °C, the thermal gradient is intensified, and therefore the hygric flux is increased, also due to the increase in the saturated vapor pressure with temperature.

5. Hygrothermal Analysis Under Real Climatic Conditions

While experimental tests characterize the material’s response under controlled thermal and hygrometric conditions, the numerical study is a complementary analysis where it is possible to compare earth formulations and walls configurations under conditions reflecting the outdoor and indoor real climate.

5.1. Joint Analysis of Heat and Moisture Fluxes Under Variations in Temperature and Humidity

Numerical calculations were realized in order to understand the hygrothermal behavior of building envelopes with internal insulation, as shown in

Figure 15, by varying exterior climatic conditions with a fixed interior temperature of 20 °C and 50% relative humidity. The exterior temperatures were varied from 0 °C to 50 °C in order to assess the transition from a building in a heating period to a building in a period with exterior heat gain, as is the case in summer. Likewise, the exterior relative humidity was varied from 30% to 90%, representing dry and humid climates.

Figure 16a,b show that heat and hygric fluxes respectively for different RH and outside temperatures. Heat flux between inside building at 20 °C and the outside with temperature varied from 0 °C to 50 °C, shows a heat loss to the exterior for 0 °C and 10 °C. No heat flux for 20 °C due to no thermal gradient between the two ambiences. A heat gain to the exterior due to the increase in temperature starting from 30 °C. The heat flux remains identical for all the exterior relative humidities cases studied. However, the hygric flux presents a more dynamic behavior, because it depends on the partial vapor pressure, itself controlled by both the relative humidity level and the temperature through saturated vapor pressure.

At low temperatures under 20 °C, the hygric flux remains negative for all the exterior relative humidities, which are varied from 30% to 90%. This is due to the low saturated vapor pressure at the exterior; thus, the exterior partial vapor remains inferior to the interior one, directing the hygric flux from the interior to the exterior ambience. At 20 °C, the hygric flux remains negative when under 50% relative humidity, then there is no flux when the exterior RH is 50% equal to the interior, and then it becomes positive when it exceeds 50%. This demonstrates that when there is no heat flux, the hygric flux is governed only by the relative humidity gradient. For higher exterior temperatures, the increase in the saturated vapor pressure will cause the increase in the partial vapor pressure at the exterior ambience, even for moderate relative humidities, which then directs the hygric flux from the exterior to the interior, with an increased intensity with the increase in temperature and relative humidity. This can be explained by the hot humid climate, where the exterior ambience is hotter and retains more vapor, thus humidifying the building’s envelopes and interior ambiences. These results show the influence of the different gradients of temperature and relative humidity, where they can act in parallel or in opposition, conditioning the migration of humidity in walls.

5.2. Influence of Material Layout on the Risk of Interstitial Condensation

Three different cases were studied in this section, with the main goal of identifying conditions that are favorable to interstitial condensation, which is a sensitive phenomenon that can have negative consequences on building envelopes, causing the degradation of thermal performance, structural durability, and occupants’ comfort and health. In this context, a study through numerical calculations on three different configurations was realized, starting with a study on the structural material alone, and then a dual-layer cob composite with the structural material and the insulation material, checking the two possible dispositions, one with the structural material on the inside and the other with the insulation as the interior layer (

Figure 17).

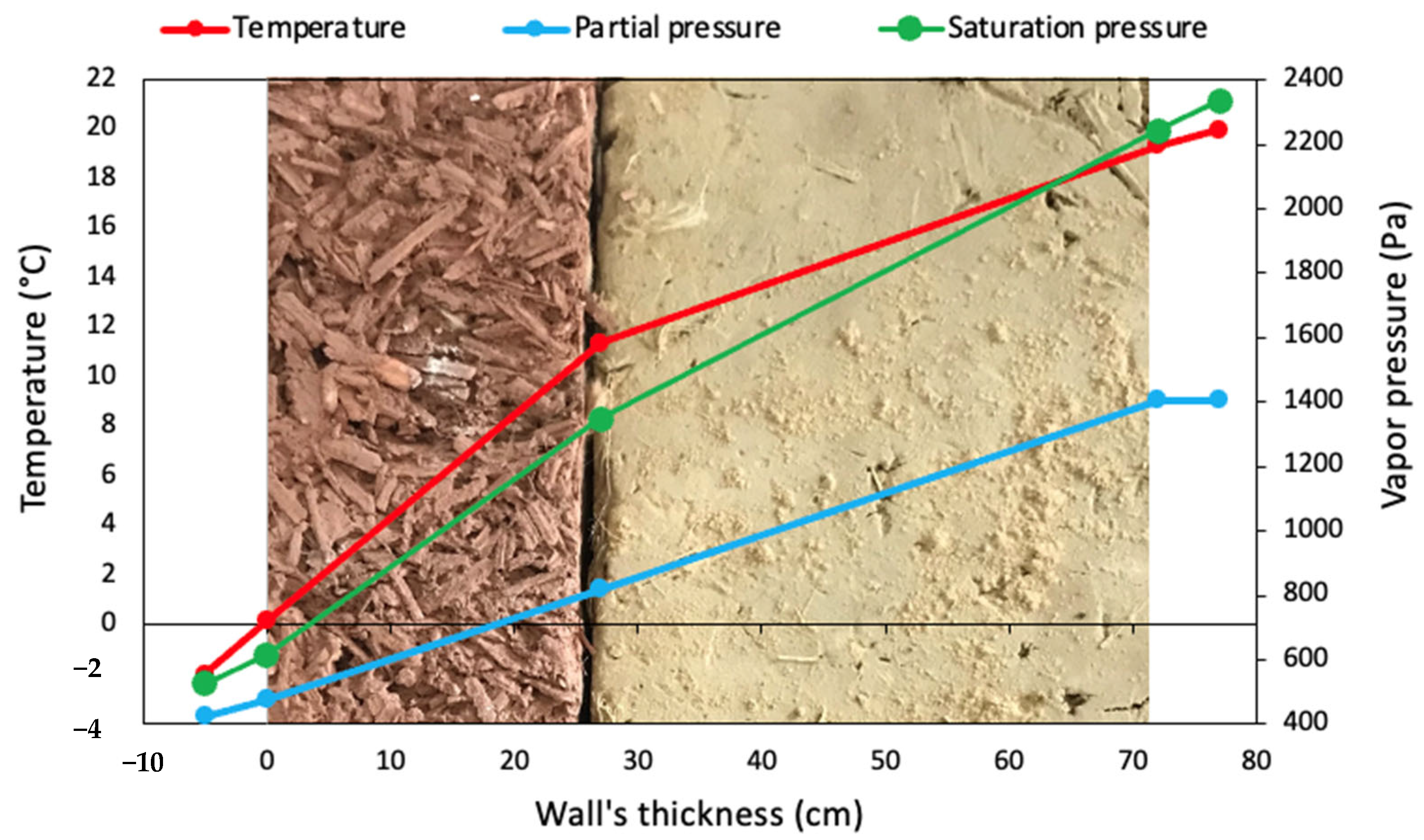

For the structural material alone, preliminary tests were performed on the temperature and relative humidity conditions from the experimental tests realized and mentioned above and were evaluated in order to assess any condensation risk, but no risk was detected, confirming the conclusions drawn from the obtained measurements. However, real winter conditions were also tested on a structural wall of 72 cm thickness, with harsh, cold temperatures, where Tint = 20 °C and Rhint = 60%, and for the exterior conditions, RH was fixed at 80%, with the variation in Text from −2 °C to −10 °C. A risk of condensation was identified until the exterior temperature reached −10 °C, where there is an intersection between Psat and Pv curves in the internal side.

Figure 18 represents the case where external conditions are equal to −2 °C and 80%, with no risk of condensation.

For the case of the double-layer cob wall, specifically the disposition where the insulation is positioned as the interior layer with 45 cm structural and 27 cm insulation, the risk of condensation is present when Tint = 20 °C and RHint = 60%, Text= −2 °C, and starting from RHext = 60%.

Figure 19 shows the case when RHext = 80%, where the partial vapor pressure clearly exceeds the saturated vapor pressure in the zone of the interface between the two materials.

As for the case where the insulation is positioned as the exterior layer with 45 cm structural and 27 cm insulation, no condensation is detected for the same harsh winter conditions, where RHext = 80% and Text = −2 °C.

Figure 20 shows that the partial water vapor never exceeds the saturated water vapor throughout the thickness of the wall, eliminating any risk of condensation.

These results show that for the configuration where the insulation is the exterior layer, the wall better manages humidity and limits the interstitial condensation risk. This behavior can be explained by the response of the different properties of the two materials. The insulation has low thermal conductivity, reducing the loss of heat from the interior to the exterior, maintaining a higher temperature inside the wall. Thus, because the temperature is decreasing more progressively in this case, the saturated vapor pressure remains high through the wall, never encountering the partial vapor pressure. On the other hand, when the structural material is placed on the outside, the wall temperature decreases more rapidly, causing a drop in Psat and an intersection with the partial vapor pressure. The excess of vapor condenses into liquid, increasing the water content of the material and influencing its thermal and mechanical properties. It is also important to take into consideration the hygric properties of these materials, where the insulation has higher sorption capacity, which allows it to absorb a part of the vapor and limits the hygric flux due to its reduced permeability in comparison with the structural material.

Figure 21a represents a comparison between the total heat fluxes of the three configurations studied. The configuration with the structural material alone presents the higher value due to its higher conductivity with no insulation layer, which means less total thermal resistance. Insulation on the external is the best-performing configuration in terms of thermal resistance, reducing the temperature gradient before heat transfer reaches the structural layer. This can be observed also through the layers’ fluxes, where each layer transports a flux proportional to its conductivity and exposition to the thermal gradient.

For the hygric fluxes,

Figure 21b shows an equal value for the double-layer configurations, which is due to the standard’s assumptions [

32], where the vapor pressures are imposed conditions identical for all the configurations. The structural layer alone shows a higher flux due to its low resistance in comparison with the double-layer configurations. The layers’ fluxes show higher values for internal insulation, promoting saturation conditions based on the Glaser method at the interface between the two materials. Conversely, external insulation reduces thermal and hygric fluxes, maintaining the structural layer at a higher temperature, eliminating condensation risks at the interface. These results thus confirm that the disposition of layers influences the hygrothermal stability of building envelopes.

6. Conclusions

This work sheds light on the thermo-hygric behavior of bio-based earthen materials mixed with fibers, as well as their use in both structural and insulating walls for low-carbon buildings. Experimental characterization enabled the selection of two optimized formulations based on thermal diffusion, structural and insulation material, each exhibiting a specific role for layered building envelopes. Thermal characterization showed that the insulating material exhibited a thermal conductivity of 0.106 W/m/K, compared to 0.24 W/m/M for the structural material. Moisture transfer experiments highlighted the influence of temperature on water vapor migration and internal moisture distribution, demonstrating the need to control water transfer to ensure the durability of earth–fiber matrices.

The numerical calculations carried out made it possible to supplement and generalize experimental observations by evaluating the behavior of single-layer and double-layer configurations. External insulation using the lightweight earthen mix is the most effective and safest arrangement, ensuring stable heat fluxes and eliminating the risk of condensation in the interfaces. In contrast, the internal insulation configuration leads to condensation at an exterior temperature of −2 °C, despite a low exterior relative humidity of 60%.

Overall, the combined insights from thermal testing, moisture transfer experiments, and hygrothermal modeling confirm the potential of earth–fiber materials for the design of walls with low environmental impact, while highlighting and providing actionable guidelines for a rigorous approach to designing robust, energy efficient, and moisture-related safe earthen wall envelopes.