Flexural Performance of Glued Laminated Timber Beams Reinforced by the Cross-Section Increasing Method

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Experimental Overview

2.1. Experimental Grouping

2.1.1. Adhesive Reinforcement Test Piece

2.1.2. Reinforcement of Specimens by Adhesive–Nail Combination Method

2.1.3. Material Properties

2.1.4. Test Piece Design

2.2. Material Testing

2.2.1. Test Piece Design and Production

2.2.2. Results of Tensile and Compressive Tests

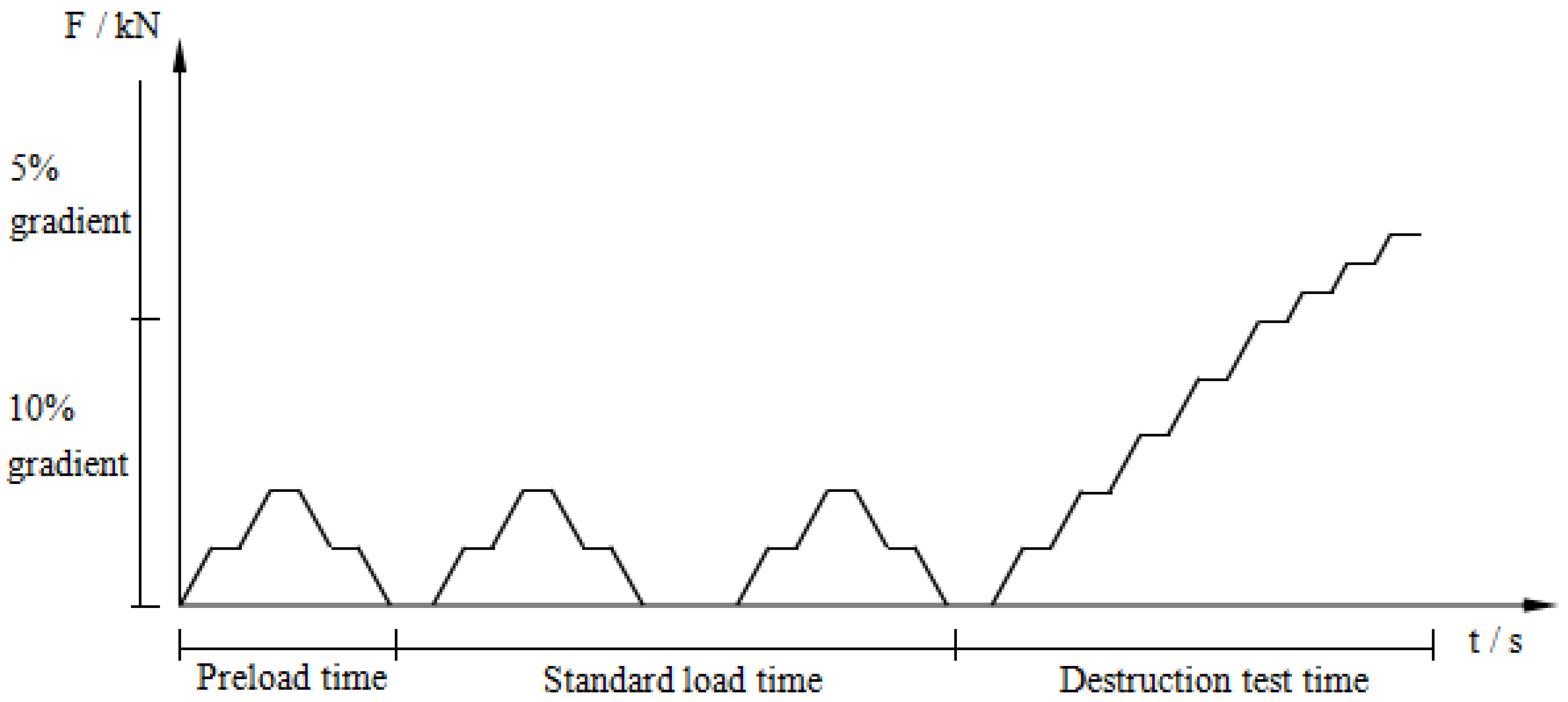

2.3. Loading System

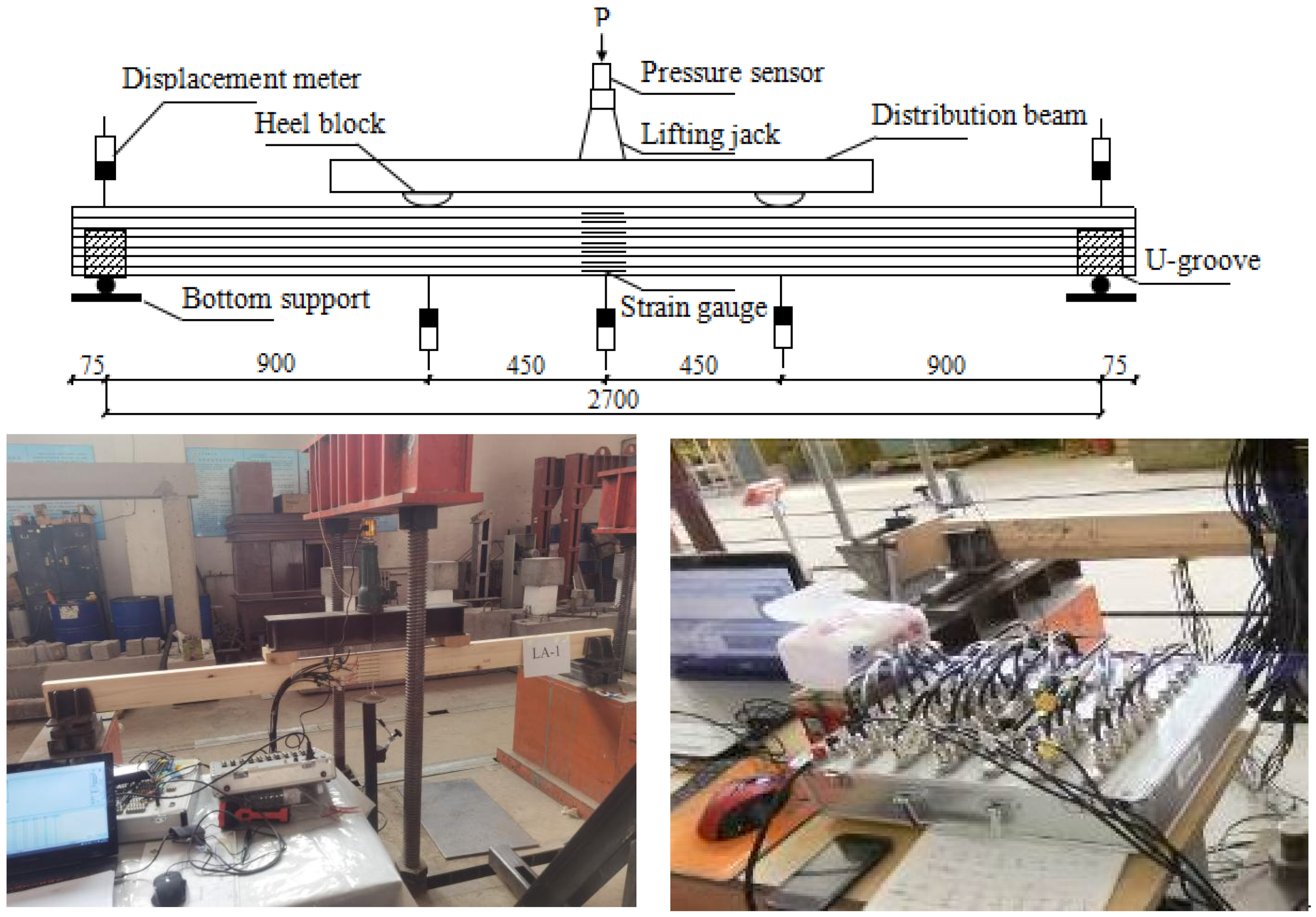

2.4. Layout of Measurement Points and Data Collection

2.4.1. Layout of Measurement Points

2.4.2. Data Collection

3. Analysis of Experimental Results

3.1. Analysis of Experimental Phenomena

- (1)

- Tear failure at the bottom of the beam

- (2)

- Beam bottom tensile failure

3.2. Analysis of Experimental Data

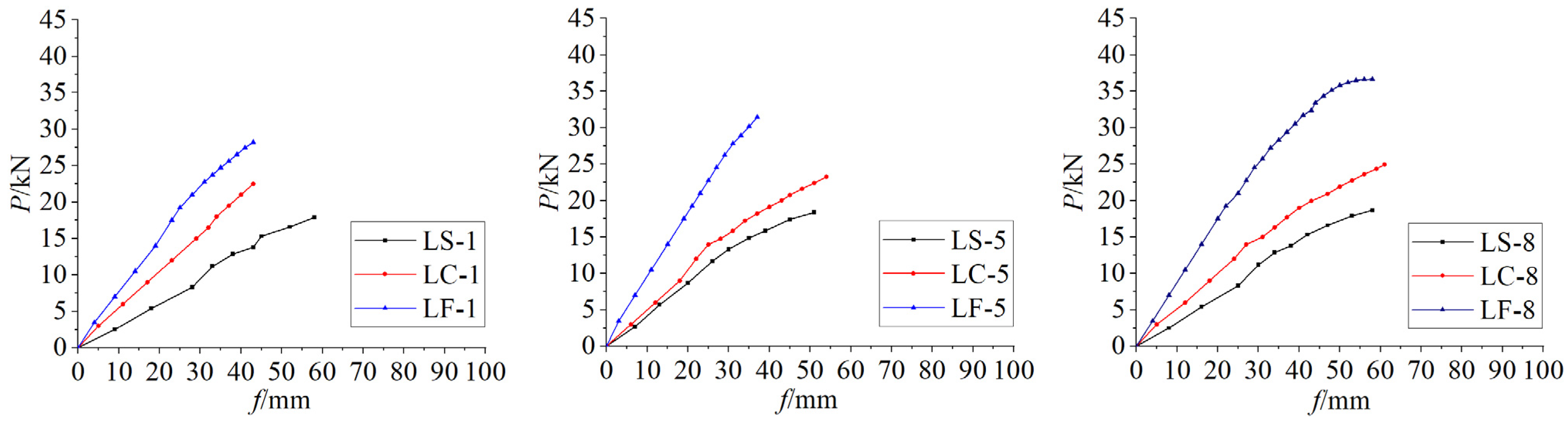

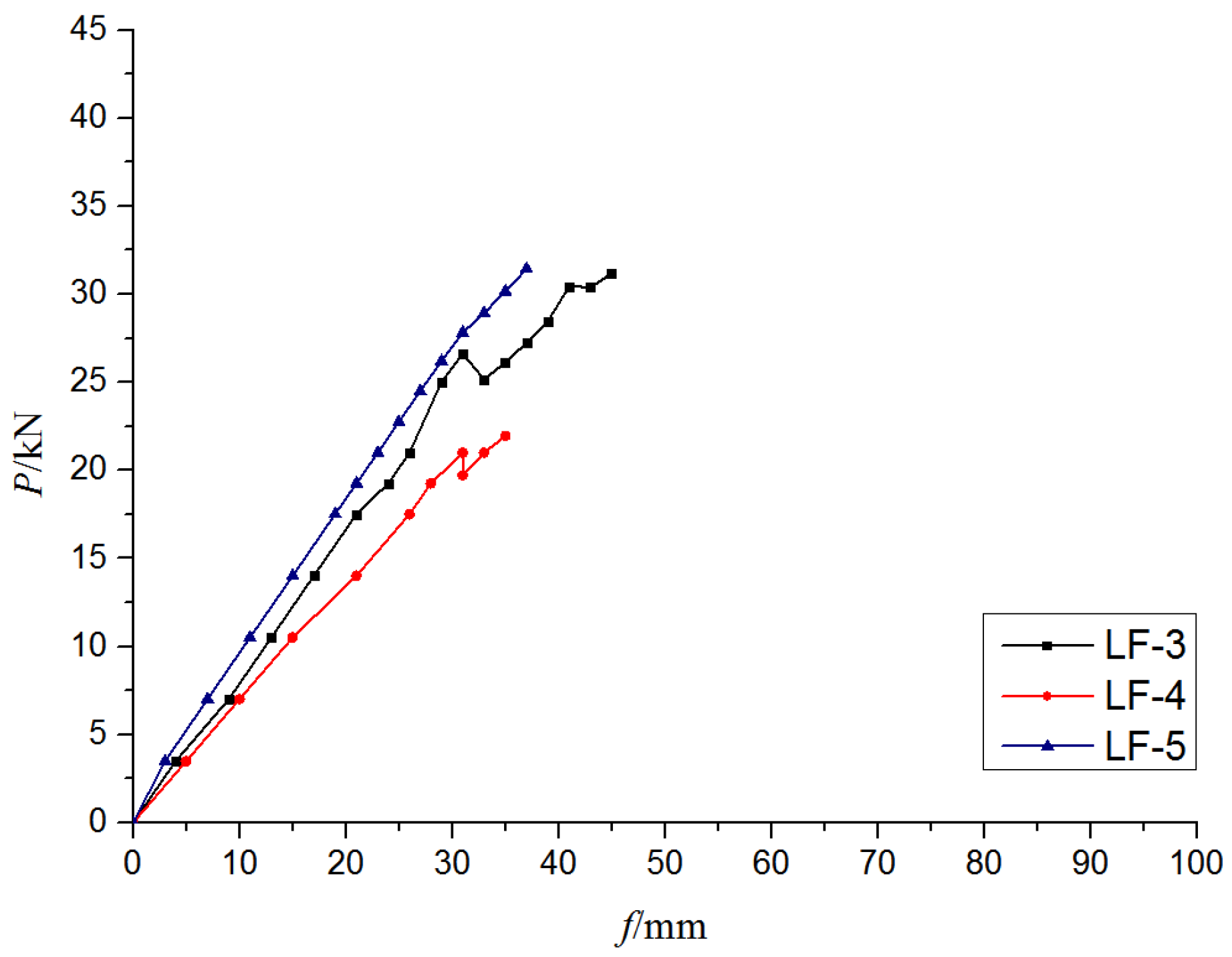

3.3. Load–Deflection Relationship Curve

3.3.1. Comparison of Curves of Specimens with Different Cross-Sectional Heights

3.3.2. Comparison of Curves for Two Reinforcement Methods

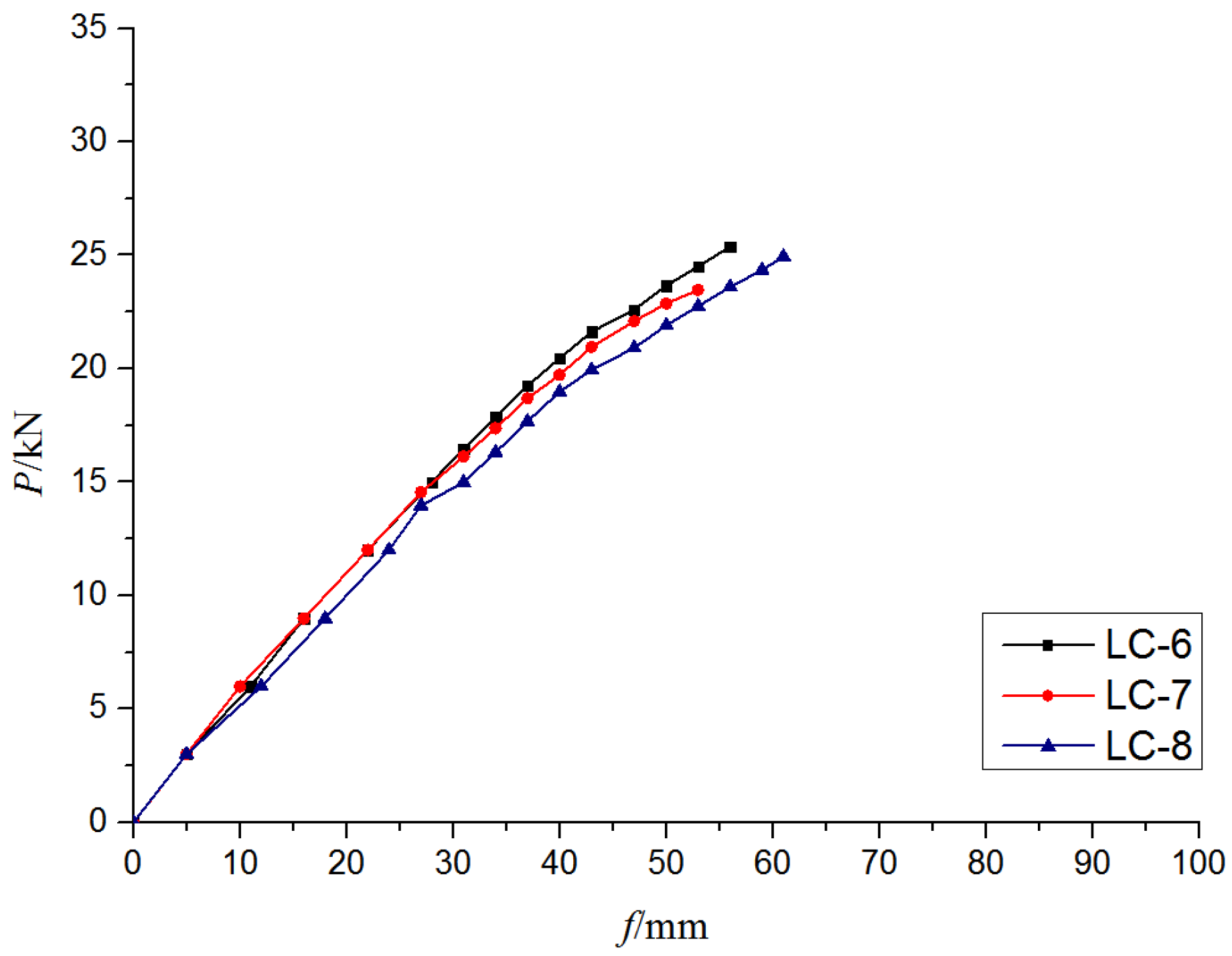

3.3.3. Comparison of Self-Tapping Screw Arrangement Methods

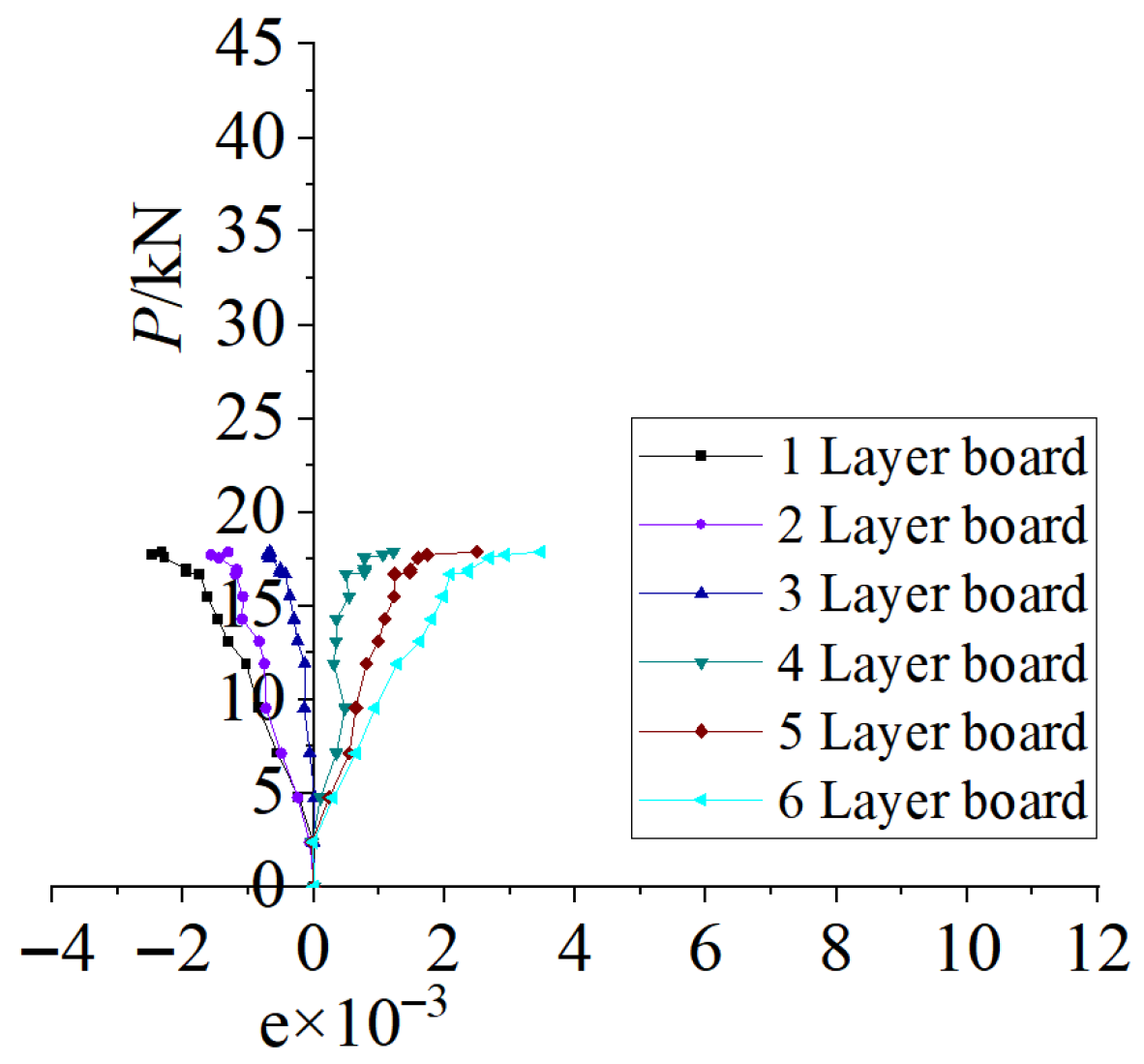

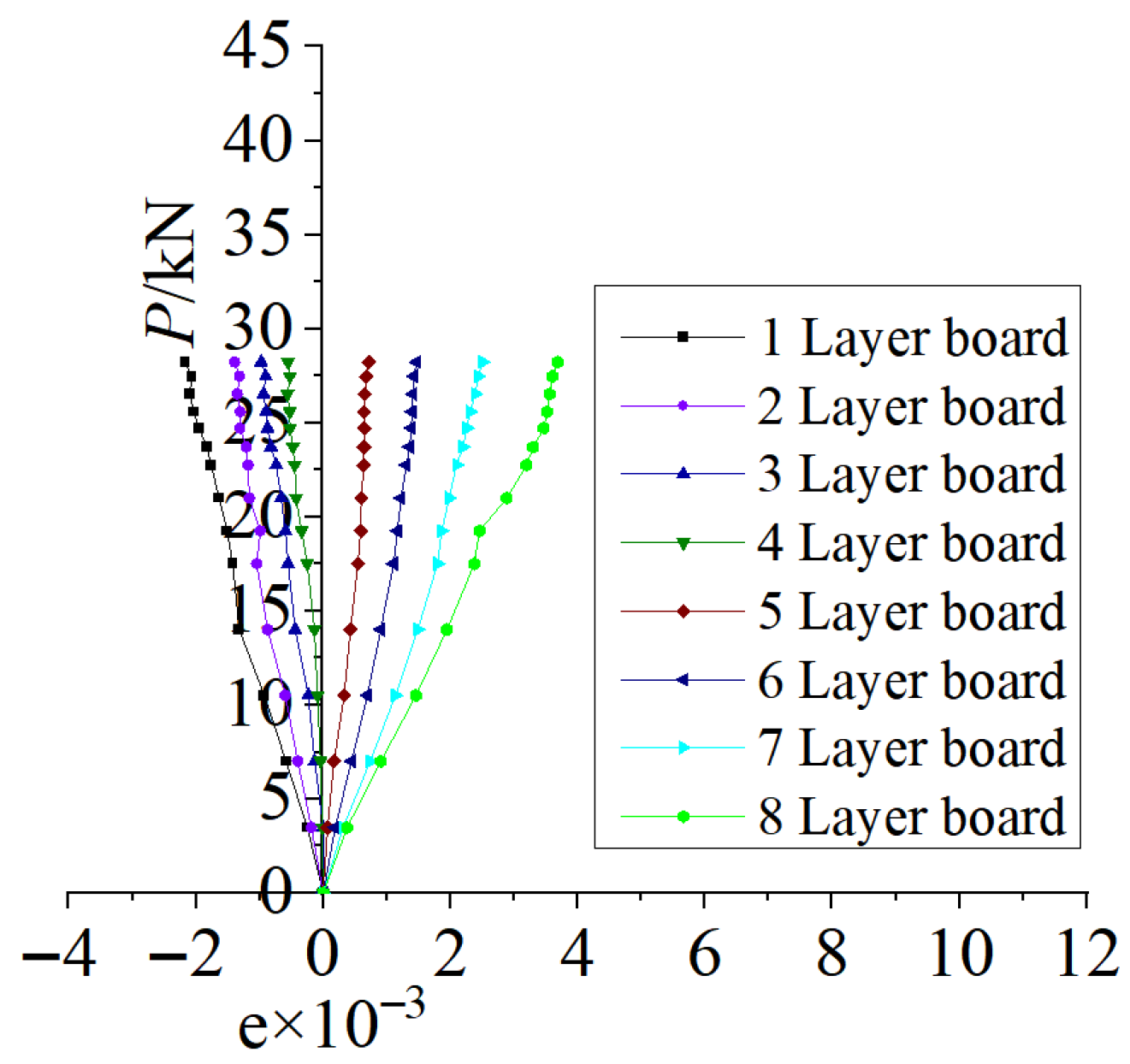

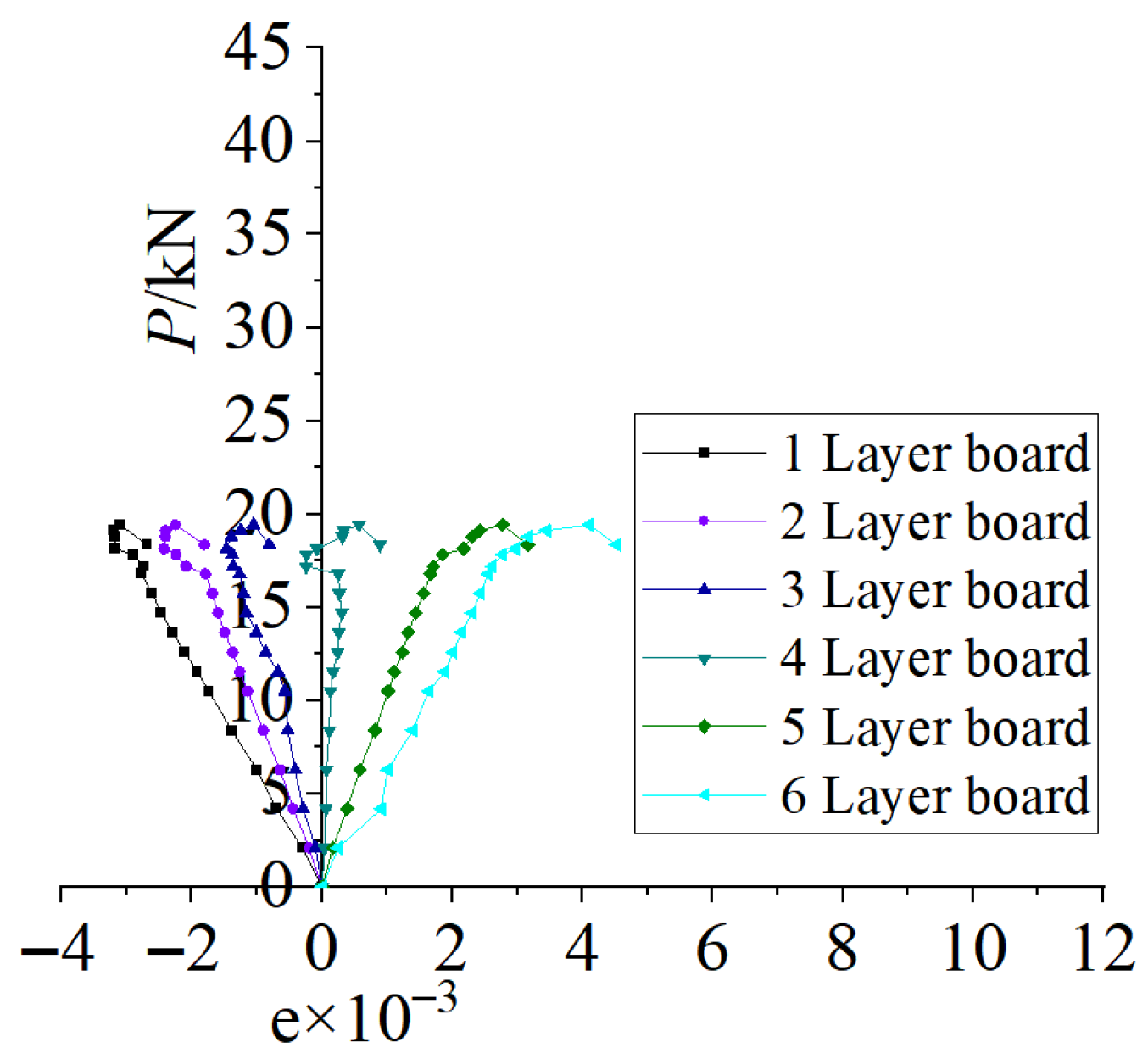

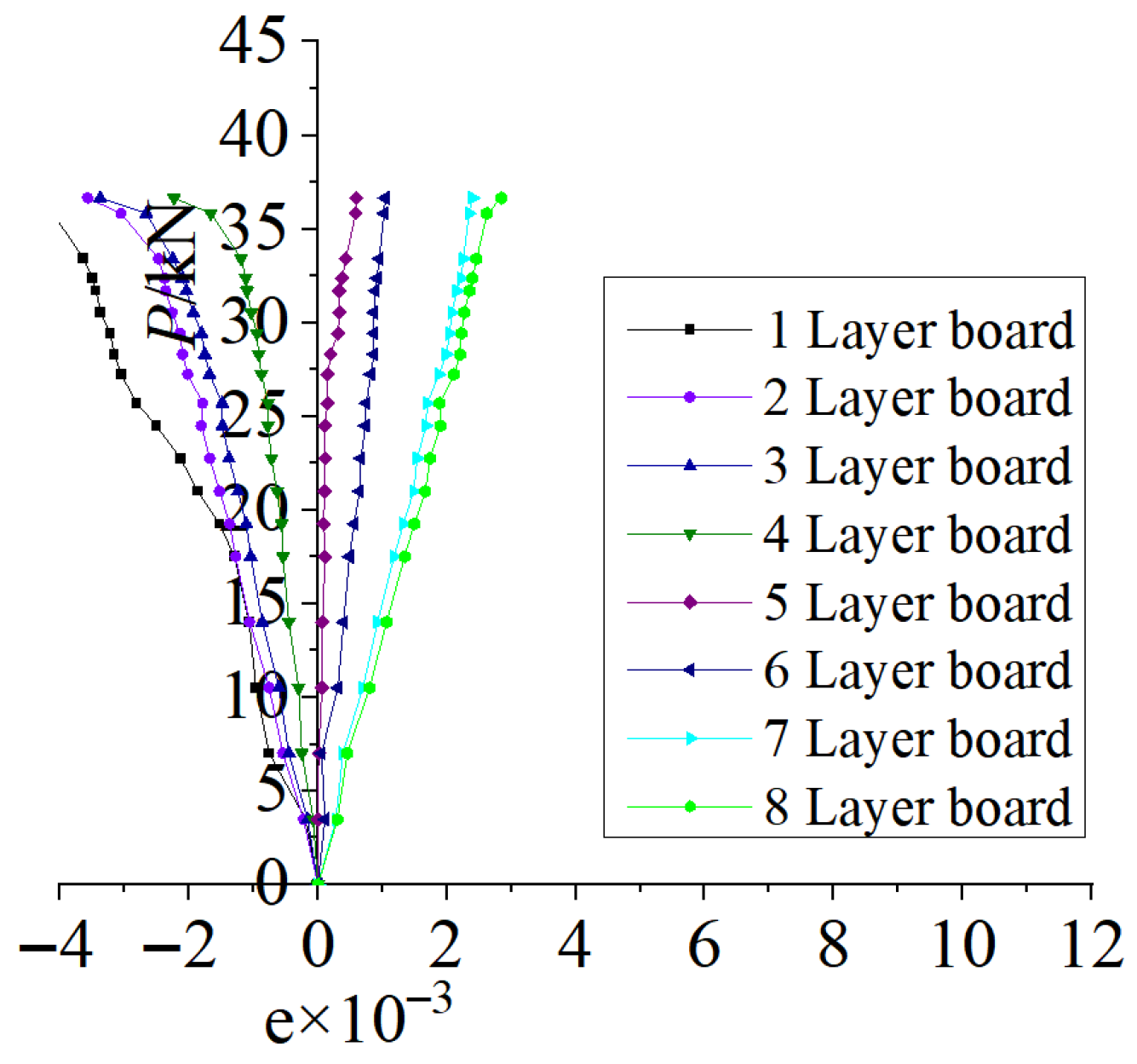

3.3.4. Comparison of Load–Strain Curve

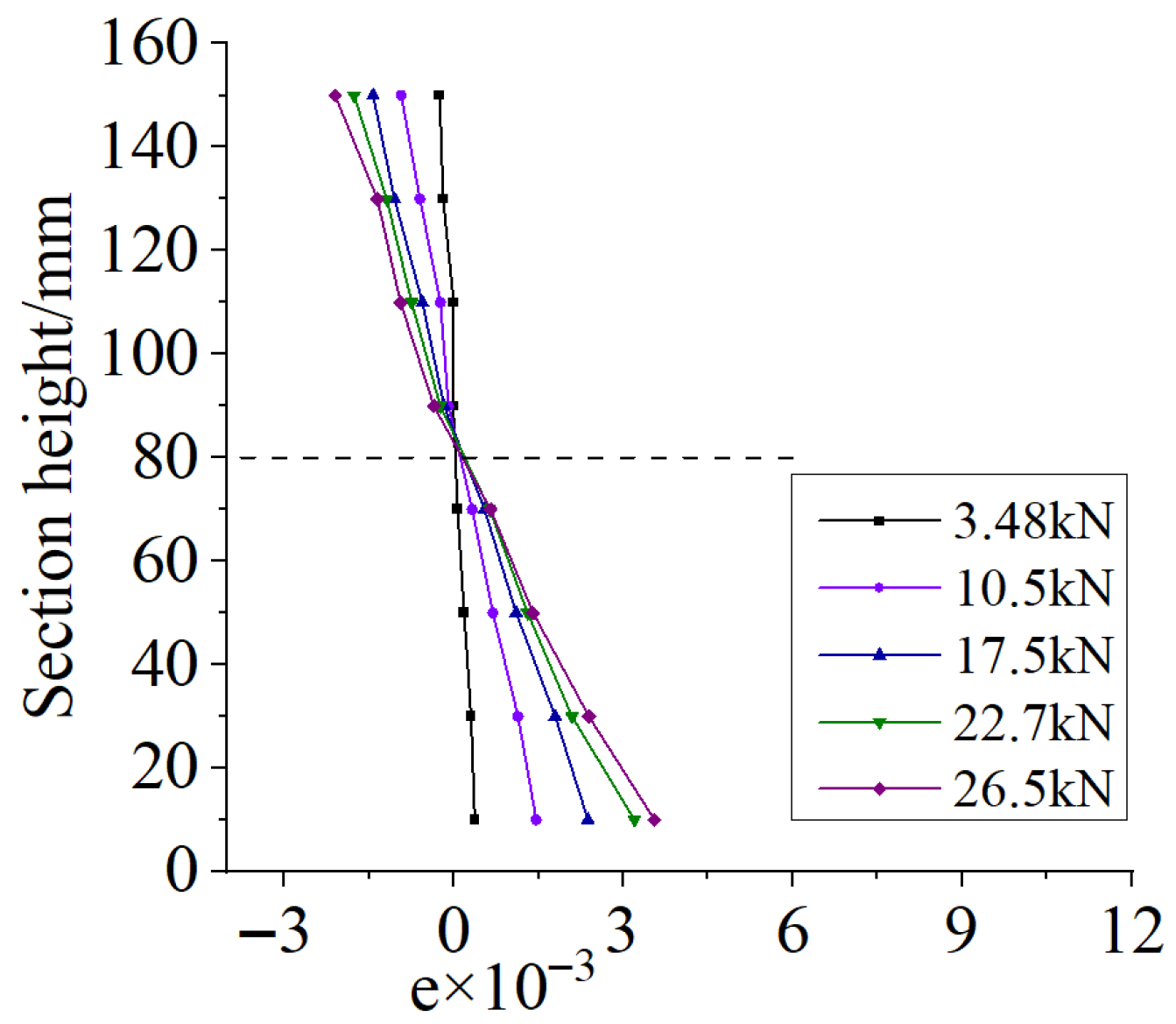

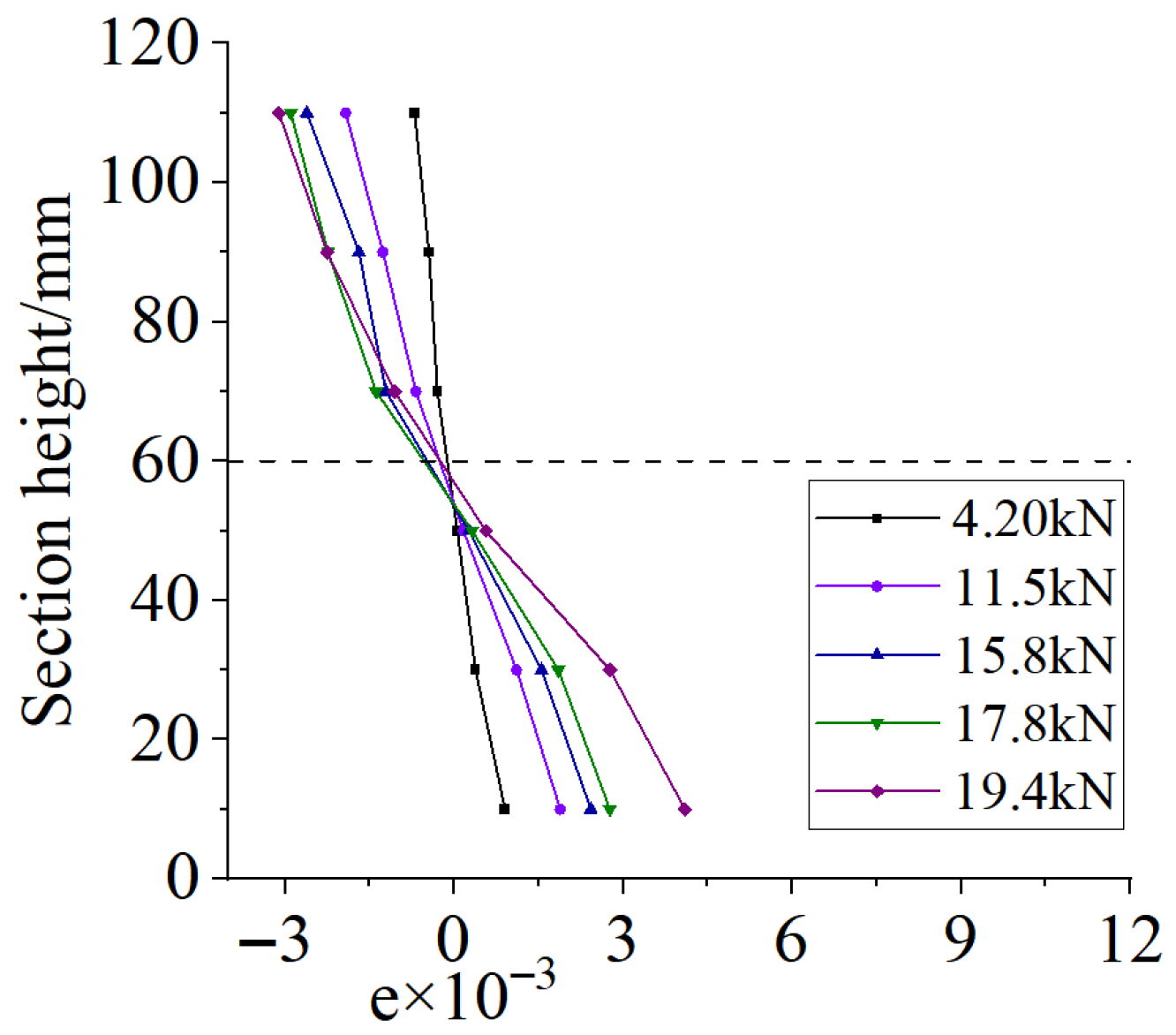

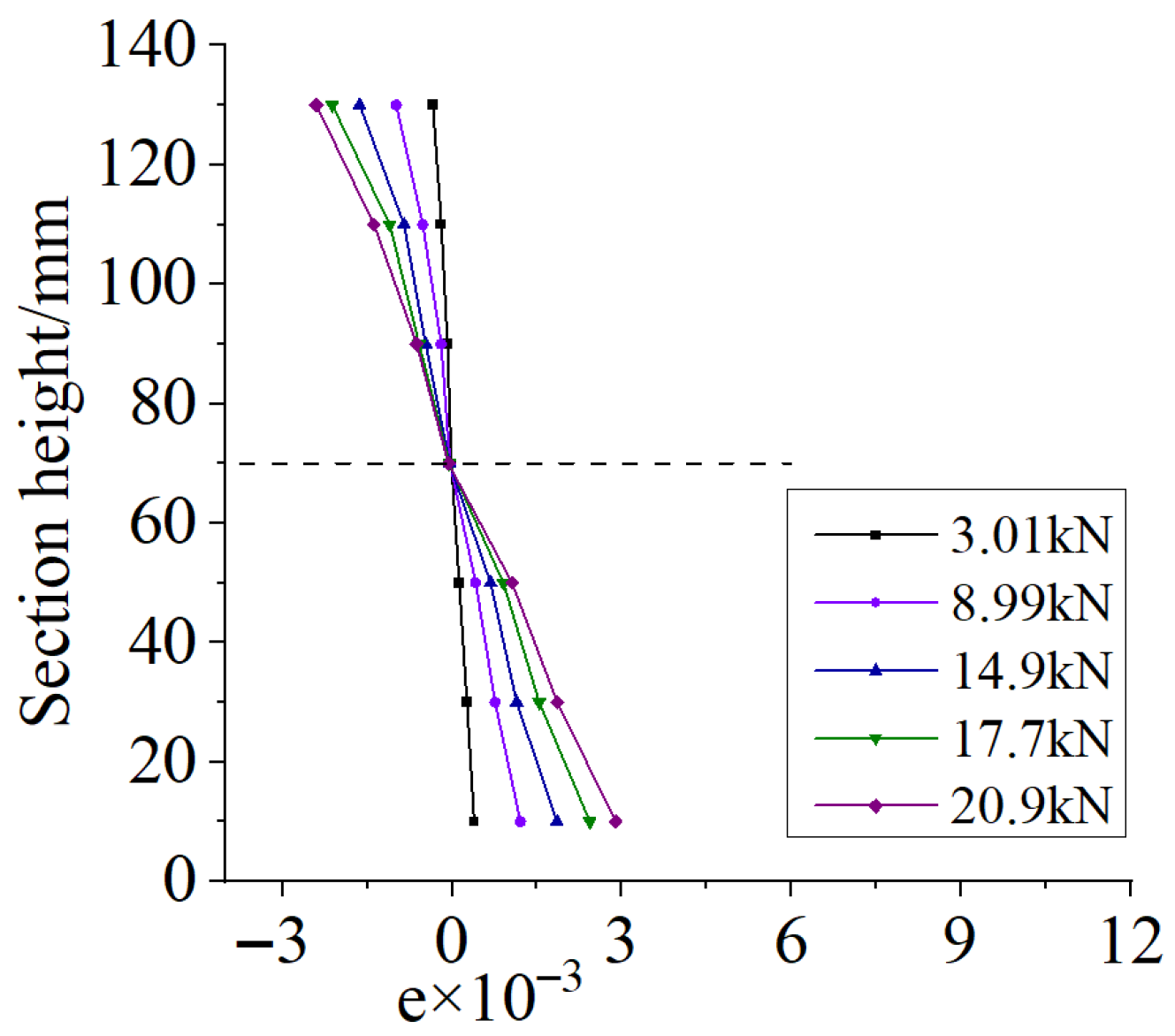

3.3.5. Comparison of Strain Relationship Curves at Mid-Span Section

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

- (1)

- Within the same group, compared to specimens reinforced with half-standard compressive stress, specimens reinforced with standard compressive stress adhesive showed 3.88–5.71% higher ultimate load, indicating that manufacturing quality affects mechanical properties.

- (2)

- Ultimate load and flexural stiffness of reinforced beams are proportional to section height. Compared with single-layer reinforced specimens, double-layer specimens showed 9.21–24.63% higher ultimate load and 33.64–43.44% higher bending stiffness. The cross-section increasing method effectively improves insufficient capacity and excessive deformation.

- (3)

- After self-tapping screws were inserted, ultimate load increased by 9.21–11.16%, indicating fuller stress development. Screws improve laminate connectivity, limit adhesive layer shear failure, and suppress crack propagation.

- (4)

- Mid-span strain remains essentially linear in both single-layer and double-layer reinforced specimens, supporting use of the plane section assumption.

- (5)

- Based on ultimate load and screw quantity considerations (8 long, 10 short) and fiber damage, 120 mm screws at 25 mm spacing and 90° angle are recommended as the optimal arrangement.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Wu, C.; Xue, J.; Song, D.; Zhang, Y. Seismic Performance Evaluation of a Roof Structure of a Historic Chinese Timber Frame Building. Int. J. Archit. Herit. 2022, 16, 1474–1495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, S.; Sun, X.; Wang, W.; Zhou, B.; Sun, X.; Sun, J.; Wang, X. The Reaction-to-fire Performance of Wood Covered with A Transparent Film: A Potential Method for the Preservation of Chinese Wooden Historical Buildings. Int. J. Archit. Herit. 2023, 17, 1778–1790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Zhu, E.; Pan, J.; Wu, G. Energy-Dissipation Performance of Typical Beam-Column Joints in Yingxian Wood Pagoda: Experimental Study. J. Perform. Constr. Facil. 2015, 30, 04015028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Yang, F.; Zhang, J.L.; Zhang, Y.N.; Gao, Y. Ancient Commercial Buildings Seismic Performance Analysis and Study of Protection. Appl. Mech. Mater. 2013, 2545, 1965–1969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takuya, M.; Soei, K.; Satoshi, W.; Inoue, M. Environmental and Economic Evaluation of Wooden and Reinforced Concrete Non-residential Buildings III. A comparative analysis of LCA and eco-efficiency indicator based on input-output method. Mokuzai Gakkaishi 2021, 67, 7–13. [Google Scholar]

- Kevin, A.; Adam, R.P. Comparative Cradle-to-Grave Life Cycle Assessment of Low and Mid-Rise Mass Timber Buildings with Equivalent Structural Steel Alternatives. Sustainability 2021, 13, 3401. [Google Scholar]

- Paletto, A.; Becagli, C.; Geri, F.; Sacchelli, S.; De Meo, I. Use of Participatory Processes in Wood Residue Management from a Circular Bioeconomy Perspective: An Approach Adopted in Italy. Energies 2022, 15, 1011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, H.; Liu, Y.; Meng, Y.; Huang, H.; Sun, C.; Shao, Y. A Comparison of the Energy Saving and Carbon Reduction Performance between Reinforced Concrete and Cross-Laminated Timber Structures in Residential Buildings in the Severe Cold Region of China. Ecol. Environ. Conserv. 2017, 9, 1426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laitinen, M.; Ilgın, H.E.; Karjalainen, M.; Saari, A. Low-Carbon Emissions and Cost of Frame Structures for Wooden and Concrete Apartment Buildings: Case Study from Finland. Buildings 2024, 14, 1194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bravo, T.P.; Gattas, J.M.; Bravo, F.; Astroza, R.; Maluk, C. Experimental assessment of modal properties of hybrid CFRP-timber panels. Constr. Build. Mater. 2024, 438, 137075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Konstantinos, S.; Anastasios, S.; Solomon, T. Displacement-Based Seismic Design and Assessment of Friction-Dissipating Light-Timber Frames Coupled with a Self-Centering CLT Wall. J. Perform. Constr. Facil. 2024, 38. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, T.; Di, J.; Zuo, H. Long-Term Loading Experimental Research of Prestressed Glulam Beams Based on Creep Influence. Sustainability 2022, 14, 9937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakalarz, M.M.; Kossakowski, P.G. Application of Transformed Cross-Section Method for Analytical Analysis of Laminated Veneer Lumber Beams Strengthened with Composite Materials. Fibers 2023, 11, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saad, K.; Lengyel, A. Strengthening Timber Structural Members with CFRP and GFRP: A State-of-the-Art Review. Polymers 2022, 14, 2381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yi, J.; Zhu, B.; He, G.; Zhou, Y. Experimental study on stiffness degradation of CFRP reinforced glued laminated timber beams. J. Cent. South Univ. For. Technol. 2021, 41, 165–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, B. Experimental Study on the Flexural Performance of Glued Laminated Timber Beams Strengthened by Adhesive Enlarging Section Method. Master’s Thesis, Northeast Forestry University, Harbin, China, 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Xue, W.; Guo, N. Bending performance of steel plate reinforced laminated timber beams. J. Jilin Univ. (Eng. Ed.) 2017, 47, 468–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asa, P.; Feghali, E.C.; Steixner, C.; Tahouni, Y.; Wagner, H.J.; Knippers, J.; Menges, A. Embraced wood: Circular construction method for composite long-span beams from unprocessed reclaimed timber, fibers and clay. Constr. Build. Mater. 2024, 416, 135096, Corrigendum to Constr. Build. Mater. 2024, 424, 135939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leibnitz, O.; Dreimol, C.H.; Stucki, S.; Sanz-Pont, D.; Keplinger, T.; Burgert, I.; Ding, Y. Renewable wood-phase change material composites for passive temperature regulation of buildings. Next Mater. 2024, 2, 100132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dan, B.; Felix, H. Structural design using reclaimed wood—A case study and proposed design procedure. J. Clean. Prod. 2023, 420, 138316. [Google Scholar]

- Munandar, W.A.; Purba, R.H.; Christiyanto, A. Exploratory study on the utilization of recycled wood as raw material for cross laminated timber. IOP Conf. Ser. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2019, 669, 012011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Group | Beam Number | Sectional Dimension/mm | Reinforcement Section Height/mm | Reinforcement Materials | Number of Layers | Compression Stress During Adhesive Bonding/N/mm2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LS | LS1 | 50 × 120 | —— | —— | 7 | 0.8 |

| LS2 | 50 × 120 | —— | —— | 7 | 0.4 | |

| LC | LC1 | 50 × 140 | 20 | Douglas fir | 7 | 0.8 |

| LC2 | 50 × 140 | 20 | Douglas fir | 7 | 0.4 | |

| LF | LF1 | 50 × 160 | 40 | Douglas fir | 8 | 0.8 |

| LF2 | 50 × 160 | 40 | Douglas fir | 8 | 0.4 |

| Group | Beam Number | Sectional Dimension/mm | Reinforcement Section Height/mm | Number of Layers | Vertical Anchoring Depth of Self-Tapping Screws/mm |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Reinforcement Materials | Self-Tapping Screw Insertion Angle | Self-Tapping Screw Spacing/mm | |||

| LS | LS5 | 50 × 120 | —— | 7 | 85 |

| —— | 45° | 250 | |||

| LS8 | 50 × 120 | —— | 7 | 100 | |

| —— | 90° | 250 | |||

| LC | LC3 | 50 × 140 | 20 | 7 | 70 |

| Douglas fir | 45° | 200 | |||

| LC4 | 50 × 140 | 20 | 7 | 85 | |

| Douglas fir | 45° | 200 | |||

| LC5 | 50 × 140 | 20 | 7 | 85 | |

| Douglas fir | 45° | 250 | |||

| LC6 | 50 × 140 | 20 | 7 | 100 | |

| Douglas fir | 90° | 200 | |||

| LC7 | 50 × 140 | 20 | 7 | 120 | |

| Douglas fir | 90° | 200 | |||

| LC8 | 50 × 140 | 20 | 7 | 120 | |

| Douglas fir | 90° | 250 | |||

| LE | LF3 | 50 × 160 | 20 | 8 | 70 |

| Douglas fir | 45° | 200 | |||

| LF4 | 50 × 160 | 20 | 8 | 85 | |

| Douglas fir | 45° | 200 | |||

| LF5 | 50 × 160 | 20 | 8 | 85 | |

| Douglas fir | 45° | 250 | |||

| LF6 | 50 × 160 | 20 | 8 | 100 | |

| Douglas fir | 90° | 200 | |||

| LF7 | 50 × 160 | 20 | 8 | 120 | |

| Douglas fir | 90° | 200 | |||

| LF8 | 50 × 160 | 20 | 8 | 120 | |

| Douglas fir | 90° | 250 |

| Camphor Pine | Douglas Fir | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tensile Strength/MPa | Modulus of Elasticity/MPa | Compressive strength/MPa | Modulus of Elasticity/MPa | Tensile Strength/MPa | Modulus of Elasticity/MPa | Compressive Strength/MPa | Modulus of Elasticity/MPa |

| 107.43 | 12,263.0 | 47.73 | 11,462.7 | 91.24 | 10,920.2 | 46.47 | 11,219.0 |

| Camphor Pine | Douglas Fir | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Standard Deviation of Tensile Strength | Coefficient of Variation in Tensile Strength/% | Standard Deviation of Tensile Modulus of Elasticity | Coefficient of Variation in Tensile Modulus of Elasticity/% | Standard Deviation of Tensile Strength | Coefficient of Variation in Tensile Strength/% | Standard Deviation of Tensile Modulus of Elasticity | Coefficient of Variation in Tensile Modulus of Elasticity/% |

| 20.25 | 18.85 | 2362.87 | 19.27 | 13.40 | 14.68 | 879.99 | 8.06 |

| Camphor Pine | Douglas Fir | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Standard Deviation of Compressive Strength | Coefficient of Variation in Compressive Strength/% | Standard Deviation of Compressive Modulus of Elasticity | Coefficient of Variation in Compressive Modulus of Elasticity/% | Standard Deviation of Compressive Strength | Coefficient of Variation in Compressive Strength/% | Standard Deviation of Compressive Modulus of Elasticity | Coefficient of Variation in Compressive Modulus of Elasticity/% |

| 3.16 | 6.62 | 1574.01 | 13.73 | 2.51 | 5.4 | 1577.55 | 13.69 |

| Group | Beam Number | Failure Mode of the Specimen | Ultimate Load of the Specimen/kN | Mid-Span Deflection of the Specimen/mm | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Test Value | Average Value | Test Value | Average Value | |||

| LS | LS-1 | ① | 23.45 | 22.99 | 60 | 50.5 |

| LS-2 | ① | 22.54 | 41 | |||

| LS-5 | ② | 24.95 | 25.24 | 53 | 60.66 | |

| LS-8 | ② | 23.47 | 56 | |||

| LC | LC-1 | ① | 27.95 | 27.22 | 82 | 80 |

| LC-2 | ① | 26.49 | 78 | |||

| LC-3 | ② | 30.99 | 30.25 | 81 | 83.66 | |

| LC-4 | ② | 29.40 | 85 | |||

| LC-5 | ② | 27.63 | 86 | |||

| LC-6 | ② | 30.79 | 91 | |||

| LC-7 | ② | 31.57 | 80 | |||

| LC-8 | ② | 31.12 | 79 | |||

| LF | LF-1 | ① | 35.91 | 35.12 | 55 | 53.5 |

| LF-2 | ① | 34.33 | 52 | |||

| LF-3 | ② | 39.86 | 39.36 | 66 | 71.2 | |

| LF-4 | ② | 39.19 | 78 | |||

| LF-5 | ② | 40.92 | 73 | |||

| LF-6 | ② | 39.47 | 61 | |||

| LF-7 | ② | 37.37 | 70 | |||

| LF-8 | ② | 39.40 | 79 | |||

| Group | LS | LC | LF | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Reinforcement method | Adhesive | Adhesive and nail | Adhesive | Adhesive and nail | Adhesive | Adhesive and nail |

| Average ultimate load/kN | 16.10 | 18.5 | 22.13 | 24.60 | 27.58 | 30.12 |

| Average deflection at mid-span/mm | 56 | 54.5 | 44.5 | 52.63 | 41.5 | 49.33 |

| Average bending stiffness/kN·m2 | 124.56 | 147.07 | 204.02 | 181.5 | 272.66 | 260.34 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Wang, T.; Wang, X.; Guo, N.; Wu, M.; Wu, Z.; Liang, M. Flexural Performance of Glued Laminated Timber Beams Reinforced by the Cross-Section Increasing Method. Buildings 2026, 16, 82. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings16010082

Wang T, Wang X, Guo N, Wu M, Wu Z, Liang M. Flexural Performance of Glued Laminated Timber Beams Reinforced by the Cross-Section Increasing Method. Buildings. 2026; 16(1):82. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings16010082

Chicago/Turabian StyleWang, Tong, Xuetong Wang, Nan Guo, Mingtao Wu, Ziyang Wu, and Mingyang Liang. 2026. "Flexural Performance of Glued Laminated Timber Beams Reinforced by the Cross-Section Increasing Method" Buildings 16, no. 1: 82. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings16010082

APA StyleWang, T., Wang, X., Guo, N., Wu, M., Wu, Z., & Liang, M. (2026). Flexural Performance of Glued Laminated Timber Beams Reinforced by the Cross-Section Increasing Method. Buildings, 16(1), 82. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings16010082