1. Introduction

In recent decades, contemporary housing in Serbia has undergone dynamic and multi-layered transformations driven by increasing economic, social and technological changes [

1,

2,

3,

4,

5]. Intensive residential construction, particularly in larger cities, has expanded and diversified the housing stock, while simultaneously producing inconsistencies in spatial quality, organisation and everyday usability due to dominant market priorities and economic constraints. In the context of this study, spatial quality is understood as the degree to which the spatial organisation of the dwelling, its layout, relationships between functional zones, availability of daylight, circulation logic, and potential for everyday use and adaptation, supports residents’ daily activities, comfort, and long-term satisfaction. Current practice exhibits a wide range of architectural solutions, from simplified rational layouts to apartments with functional deficiencies that directly affect users’ quality of life.

In architectural discourse and practice in Serbia, housing quality has traditionally been assessed through normative and technical indicators such as floor area, daylighting, ventilation and energy efficiency, while the lived experience of residents seldom becomes a subject of systematic investigation [

6,

7,

8]. It is within this experiential layer of use, perception and evaluation that everyday dwelling patterns emerge, revealing frequent shortcomings such as insufficient spatial flexibility, limited adaptability, unclear relations between functional zones, inadequately positioned kitchens, reduced privacy and lack of storage space [

9,

10]. These phenomena should be understood not as isolated errors, but as indicators of a broader discrepancy between design intentions and actual user needs.

Over the past three decades in Serbia, certain shifts have emerged, when compared to the period of post-war and socialist construction, that have significantly influenced the quality of dwelling organisation. These developments indicate a loss of continuity with concepts that previously ensured higher levels of spatial functionality and comfort [

11]. Identifying genuine user preferences, shaped not solely by market factors but also by the complex qualitative characteristics of housing units, is important for assessing current demands in the housing sector and, consequently, for a wide range of decision makers in the fields of housing policy, urban planning and architecture.

Similar processes of transformation in housing provision, spatial standards, and user experience are observed in other Central and Eastern European countries, particularly within post-socialist contexts such as the Czech Republic, Poland, and Croatia [

1,

12,

13,

14]. These parallels indicate that the issues identified in contemporary housing in Serbia are not isolated phenomena, but part of broader post-socialist transformations and global trends in housing design, which makes the results of this study relevant beyond the national context.

The conceptual point of departure of this paper is grounded in understanding spatial characteristics of the dwelling as a fundamental aspect of housing quality, and dwelling satisfaction as its key subjective indicator, examined within the context of post-socialist transformation in Serbia.

The research presented in this paper is focused on the empirical examination of how residents of Serbia perceive, evaluate and interpret the space of their dwellings, with the aim of determining how functional and perceptual characteristics of space influence the quality of everyday living. Particular emphasis is placed on the subjective experience of comfort, privacy, spatial organisation and flexibility, specifically on the relationship between designed and experienced spatial values.

To address the research objectives and to empirically examine the relationship between spatial characteristics of dwellings and residents’ subjective evaluations, a structured questionnaire was developed as the primary research instrument.

The questionnaire used in the study comprised several thematic sections: basic demographic information of the respondents, objective characteristics of the dwelling, perception of daylighting, ventilation and room organisation, as well as emotional aspects of living in the home and preferences regarding dwelling type. This structure allows for the integration of quantitative and qualitative insights and enables the identification of patterns indicating the relationship between functional solutions and users’ subjective satisfaction.

The research hypothesis is formulated in exploratory terms and examines whether residents of Serbia tend to evaluate dwellings from the period of socialist construction differently from more recently built apartments, particularly with regard to spatial organisation, functionality, and comfort, without presupposing the direction of such differences.

2. Background and Literature Review

The spatial characteristics of the dwelling represent one of the key determinants of housing quality, as they directly shape everyday patterns of space use, perceptual impressions and the long-term experience of the home. Contemporary research confirms that housing quality is not defined solely by technical or material parameters but primarily by spatial organisation, the relations between zones and the clarity of spatial structure. Studies by Brkanić Mihić et al. [

12,

15] demonstrate that spaciousness, legibility and an adequate hierarchy of rooms constitute the basis of a positive user experience, with rational spatial configuration identified as a crucial factor of satisfaction, often more important than dwelling size or finishing quality. Along similar lines, earlier research on principles of residential spatial organisation [

11] indicates that optimal housing models rely on clearly defined functional axes, well-established relations between private and shared zones, and opportunities for spatial adaptation throughout the household life cycle.

Dwelling satisfaction refers to residents’ subjective evaluation of how physical and functional attributes of the dwelling meet their needs [

16], and is often treated as a key indicator of quality of life and residential behaviour [

17,

18]. Unlike broader concepts of housing or residential satisfaction [

19,

20,

21], which include neighbourhood and social context, dwelling satisfaction focuses on the evaluation of the dwelling space itself and its qualitative attributes [

22,

23].

Dwelling satisfaction is used predominantly in architectural studies and post-occupancy evaluations, and is typically measured through the physical, spatial and functional characteristics of the home. Dwelling satisfaction is commonly assessed through indicators related to spatial layout, functional adequacy, construction quality, thermal and acoustic comfort, daylighting, privacy and maintenance [

18]. Empirical research in this field predominantly relies on quantitative survey methods, using structured questionnaires and Likert-type scales to capture residents’ subjective evaluations and to enable statistical analysis of relationships between spatial characteristics and perceived housing quality [

16,

20,

23,

24,

25]. Some studies additionally apply mixed methods, combining survey data with qualitative interviews or spatial analyses in order to capture contextual and cultural factors influencing the perception of residential space [

26,

27]. This methodological spectrum reflects the multidimensional nature of dwelling satisfaction, linking subjective assessments with the physical characteristics of the dwelling and with broader social and spatial-environmental factors.

In post-socialist European countries, the transition from a centrally planned to a market economy, accompanied by a comprehensive reform of housing systems and the mass privatisation of socially owned dwellings, has influenced the need to modify the quality and patterns of use of the inherited socialist housing stock. This has occurred both through planned processes of rehabilitation and upgrading, and through spontaneous individual spatial interventions undertaken by new homeowners [

1,

2,

3,

4,

5]. At the same time, influenced by market logic and by sustainability challenges, approaches to planning and design have been redefined within new models of residential construction [

28,

29]. Research on housing satisfaction in the post-socialist European context is often oriented towards comparative analyses of multi-family housing complexes from the socialist and post-socialist periods [

13,

30]. Previous, relatively scarce studies on housing satisfaction in Serbia have addressed factors of quality in contemporary residential complexes [

31], residential preferences in urban and suburban areas [

32,

33], or have focused on specific social groups, such as young people [

34] or social housing beneficiaries [

35].

Despite the significance of housing-related issues for contemporary architectural practice, previous research in Serbia has predominantly focused on typological and normative aspects of residential construction [

6,

7], whereas empirical insights into user perception, everyday spatial experience and residential comfort have been considerably less frequent [

8,

36,

37]. Although some authors have recently emphasised the importance of spatial flexibility and the adaptability of dwellings to contemporary needs [

9], systematic investigations of user attitudes towards spatial quality are still at an early stage. In the regional and international context, comparable approaches have been identified in studies conducted in Croatia [

12,

14], Iran [

38], Iraq [

39] and China [

40], as well as in works addressing perceptions of urban housing and residential attractiveness [

10,

41]. For the purpose of facilitating the evaluation of residential units, a general model for systematic assessment based on spatial indicators has been developed, whereby users determine the desirability of specific spatial characteristics of the dwelling [

15], marking a turning point in the formal incorporation of user participation into the assessment of residential space. Furthermore, authors of theoretical review papers have highlighted the significance of the relationship between user perception and spatial design factors, examined jointly under the concept of ‘Domestic Environmental Experience Design’ [

42,

43,

44,

45]. In addition, Korean studies introduce the concept of SDA (Spatial Design Adequacy) for evaluating prospective residents’ satisfaction, likewise analysing the relationship between designed spatial elements and user perception [

46]. It is precisely within this discontinuity between design standards and user experience that the need for new empirical research on contemporary housing in Serbia becomes evident.

Characteristics of the Housing Stock in Serbia

According to data from the most recent 2022 Census of Population, Households and Dwellings [

47], the Republic of Serbia has a total of 3,613,352 dwellings, of which 72.7% are occupied. Of the total number, 58.2% are located in urban settlements and 41.8% in other settlements. Regional distribution shows that the largest share of dwellings is found in the Šumadija and Western Serbia Region (28.1%), followed by the Vojvodina Region (24.7%), the Belgrade Region (24.0%), and the smallest share in the Southern and Eastern Serbia Region (23.2%). Approximately one-third of all dwellings (33.2%) are located in the largest urban centres, Belgrade, Novi Sad and Niš, of which Belgrade accounts for about one-quarter of the national housing stock (24%), while the remaining two cities represent 5.4% and 3.8%, respectively. In these urban centres, urban-type housing is dominant—87% in Novi Sad, 81.7% in Belgrade, and 72.7% in Niš.

As much as 98.9% of all dwellings in Serbia are privately owned, with only 0.54% in public (state) ownership. The most common form of dwelling tenure is ownership (87.3%), followed by rental (6.4%) and occupancy based on kinship (6.0%). The proportion of rental-based dwelling use is slightly higher in the Belgrade Region compared to other regions, at 9.1%, as is dwelling use based on kinship, which accounts for 6.8%.

The average floor area of an occupied dwelling at the national level is 78.4 m2, comprising 72.3 m2 in urban settlements and 89.2 m2 in other settlements. By region, the largest average dwelling sizes are found in the Vojvodina Region—85.4 m2 (79.6 m2 in urban settlements), whereas in the Belgrade Region these dwellings are significantly smaller—67.5 m2 (63.9 m2 in urban settlements). Within the overall structure of dwellings by usable floor area, those measuring 61–80 m2 predominate (23.7%), followed by 51–60 m2 (16.1%) and 41–50 m2 (14.8%). Considering the structure in terms of the number of rooms (including the living room), two-room apartments are most common in urban settlements in Serbia (37.3%), followed by three-room apartments (28.6%), one-room apartments (15.9%) and four-room apartments (11.6%). In the Belgrade Region, more than one-third of the housing stock (37.9%) in urban settlements consists of dwellings measuring between 41 and 60 m2, while regionally the most common are apartments smaller than 40 m2 (21.9%). In terms of the number of rooms, two-room apartments dominate, accounting for 40.9% of urban dwellings, followed by three-room apartments (27.5%) and one-room apartments (19.1%).

The average number of occupants per dwelling at the national level is 2.5. More than three-quarters of occupied dwellings provide households with more than 20 m2 of living space per person, with approximately 37% of dwellings offering more than 40 m2 per occupant. Conversely, in the Belgrade Region, 12.5% of urban dwellings provide less than 15 m2 of available space per person.

The total number of residential buildings recorded in the Republic of Serbia is 2,261,051, of which approximately 38.5% are located in urban settlements. As many as 96.1% of these buildings are single-family houses, while only 3.9% are multi-family residential buildings with three or more dwellings. This pronounced prevalence of single-family housing, exceeding 90% in both urban and other settlements, is observed across all regions except for the Belgrade Region, where single-family houses account for 77.3% of urban buildings, with multi-family residential buildings comprising 22.7%.

Approximately one-third of all residential buildings at the national level were constructed between 1961 and 1980. Some 24.4% were built between 1981 and 2000, while 19.3% date from the period 1919–1960. Following 2000, 10.7% of residential buildings were constructed, for 9.9% the construction period is unknown, and only 2.6% were built before 1919. Regarding the age of the housing stock, certain regional differences are observed, as well as differences according to settlement type. For example, the housing stock built after 2000 accounts for 24.2% of residential buildings in urban settlements of the Belgrade Region, almost equal to the share of buildings from 1961–1980 (24.2%) and 1981–2000 (24.9%). In contrast, in the Vojvodina Region, approximately one-fifth of residential buildings in other settlements were constructed before 1945.

The available statistical data on the housing stock in Serbia provide only a general and partial insight into the characteristics and quality of dwellings, covering their tenure, size and spatial structure, occupancy density, housing typology and age, as well as several other technical indicators not addressed here. Although significant, these data may create an impression of a “higher standard” of housing conditions in Serbia compared to comparative EUROSTAT statistics across various indicators of housing quality and deprivation [

48]. It should be noted, however, that EUROSTAT provides predominantly aggregated indicators and is limited in terms of detailed building stock characteristics, whereas more granular and spatially explicit data are available through specialised EU research databases, such as those developed within the HOTMAPS and MODERATE project consortia. The methodological limitations of the national Census undoubtedly underscore the necessity for systematic monitoring of the population’s actual housing needs through experiential and in-depth research, particularly in light of current sustainability challenges, which increasingly shape the normative framework for housing development in Serbia [

49].

3. Materials and Methods

The research methodology is based on established approaches in housing quality assessment and survey-based residential studies, which combine quantitative evaluation of spatial characteristics with residents’ subjective perceptions [

12,

15]. Survey research and Likert-scale-based questionnaires are commonly applied in studies of dwelling satisfaction and post-occupancy evaluation, as they allow for the systematic quantification of residents’ subjective assessments of spatial and functional attributes [

16,

23,

28]. The study is based on quantitative research methods, aimed at collecting and statistically analysing data on respondents’ perceptions and attitudes regarding the residential space in which they live. The primary data collection instrument was a structured questionnaire, consisting mainly of closed-ended questions, with a smaller number of open-ended questions that allowed for additional qualitative insights into respondents’ personal experiences, opinions and comments. The selection of questionnaire variables was guided by previous research on housing quality and dwelling satisfaction, with a focus on spatial, functional and perceptual attributes that have been identified as key determinants of users’ evaluation of residential space [

12,

15,

16]. Particular emphasis was placed on variables related to spatial organisation, natural lighting, ventilation, adaptability, privacy and overall comfort, as these aspects are consistently recognised in the literature as central to the subjective assessment of dwelling quality.

The questionnaire was conducted online in October 2025, employing the Google Forms platform. The selected time frame reflects a cross-sectional research design aimed at capturing residents’ perceptions at a specific moment, rather than monitoring longitudinal changes. Given the exploratory nature of the study and the focus on stable spatial characteristics of dwellings, the one-month data collection period is considered methodologically sufficient. Similar time frames have been applied in comparable survey-based housing studies focusing on user perception and dwelling satisfaction.

A total of 450 respondents participated in the study, selected through a random sampling method. The questionnaire was distributed via social media, the researchers’ professional contacts, and academic communication channels, with the aim of capturing a diverse sample of respondents in terms of age, educational background and regional characteristics. This mode of survey administration ensured broad accessibility while simultaneously adhering to fundamental ethical principles regarding voluntary participation, anonymity and data confidentiality. It should be emphasized that the sampling method used, based on online distribution, may limit the full representativeness of the results in relation to the population of the entire country, particularly with regard to older age groups, residents of rural areas, and individuals with limited access to digital platforms.

For closed-ended questions, measurement was conducted using a Likert-type scale, ranging from 1 (‘strongly disagree’ or ‘very dissatisfied’) to 5 (‘strongly agree’ or ‘very satisfied’). Depending on the type of question, the collected data included ordinal and nominal variables. Data analysis was performed using IBM SPSS Statistics software, version 23. The internal consistency of the measurement scale was assessed using Cronbach’s alpha coefficient, which yielded a value of 0.79, indicating satisfactory reliability of the instrument employed.

In the first part of the data analysis, descriptive statistical methods were applied to summarise and present the distribution of responses. To test the research hypothesis and examine relationships between variables, non-parametric tests were employed, namely Spearman’s rank correlation coefficient and the Chi-square test of independence. In cases where the assumptions of the Chi-square test were not met due to small expected frequencies in the cells, Fisher’s exact test was used. Additionally, the Monte Carlo simulation method with 10,000 sampled tables was applied to provide a more precise estimation of the significance level. The applied analytical procedures were selected in accordance with the exploratory character of the research and the predominantly ordinal nature of the collected data. The aim of the analysis was to identify dominant tendencies and relational patterns between objective dwelling characteristics and subjective perceptions, rather than to establish causal relationships or predictive models, which would require a different research design and a larger sample.

Questionnaire Description

The survey was clearly structured into four thematic sections and a concluding question, providing a coherent flow for respondents and enabling the analysis of different levels of housing perception.

The first section of the questionnaire covered basic demographic and social information about the respondents, including sex, age, level of education, current activity, city or region of residence, type of dwelling (apartment, house, co-living) and ownership status (owner, tenant, shared use). These data allow for a basic descriptive analysis of the sample structure and the potential identification of patterns that may be associated with the level of dwelling satisfaction.

The second section focused on the physical and spatial characteristics of the dwellings, including the number of rooms, total area, lighting, floor level, presence of terraces, degree of spatial adaptation, and a basic assessment of functional organisation. This segment provides insight into the actual living conditions and their relationship with the subjective evaluations presented in the following section of the questionnaire.

The third section comprised a set of statements regarding various aspects of dwelling quality, which respondents rated on a scale from 1 to 5. The ratings concerned the level of comfort, natural lighting, ventilation, adaptability of space, noise protection, thermal comfort, and ease of maintenance. This provided a quantitative basis for assessing overall dwelling satisfaction, as well as for comparing results across different types of buildings and construction periods. Together, these sections enabled the examination of relationships between objectively defined dwelling characteristics and residents’ subjective evaluations of housing quality.

The fourth section contained open-ended questions, allowing respondents to freely express their observations regarding the advantages and disadvantages of their dwellings, as well as their personal experience of the space they inhabit. These responses constitute a valuable qualitative corpus for a deeper understanding of user perception and the identification of themes that the quantitative part of the study cannot fully capture.

At the end of the questionnaire, a concluding question was posed concerning the preference for future housing—the choice between newly constructed dwellings and renovated apartments from the socialist construction period. This question, as an indicator of respondents’ value orientations, provides a basis for testing the research hypothesis and for understanding the deeper reasons shaping the perception of contemporary housing quality in Serbia.

4. Results

4.1. Demographic Profile of Respondents

Based on the sample of 450 respondents who participated in the study, a diverse yet demographically identifiable structure of participants was established, providing relevant insight into housing perceptions within the urban context of Serbia. Despite certain limitations in representativeness, the sample’s size and diversity ensure an adequate level of reliability for both descriptive and comparative analyses.

4.1.1. Sex and Age of Respondents

According to the collected responses, women comprised 68.2% of the sample, men 31.3%, and 0.4% of respondents identified as another gender. This distribution indicates a slightly higher participation of female respondents, which is common in studies related to housing habits and perceptions of living space quality, but it does not compromise the balance of the sample or significantly affect the overall validity of the results. Previous research indicates that gender differences in survey participation may occur, with women often exhibiting higher response rates in self-administered and web-based surveys. [

50].

The age structure shows that the largest proportion of respondents falls within the 20 to 39-year-old category (49.3%), while a slightly smaller but comparable share comprises individuals aged 40 to 64 (48.2%). The older population, aged over 65, accounts for 2.4%. This distribution indicates the predominance of the active population in the working and family life cycle, which is also the group most directly exposed to changes in the housing market and contemporary models of residential construction. However, the relatively small share of respondents aged over 65 represents a limitation of the sample, as perceptions of housing quality among older residents, often shaped by long-term dwelling experience and different patterns of space use, may be underrepresented. This imbalance is partly attributable to the online mode of survey distribution and should be taken into account when interpreting age-related differences in housing perception.

4.1.2. Educational Structure

Regarding education, the sample is dominated by respondents with higher education. Approximately half of the participants (48.9%) hold a university degree, while 35.1% have completed postgraduate studies (master’s or doctoral). Respondents with secondary education account for 8.2%, those with vocational college education 7.6%, and the share of individuals with primary education is negligible (0.2%). This educational profile indicates a predominantly academic and professionally active population, which is somewhat expected given the distribution of the survey through digital and professional networks.

4.1.3. Current Activity Status

Analysis of current activity status shows that 81.3% of respondents are employed, while 8.2% are self-employed. Smaller groups include the unemployed (3.6%), retirees (3.3%), and pupils/students (1.8%). Other categories, such as individuals primarily engaged in household activities, entrepreneurs, and independent artists, are each represented by less than 1%.

4.1.4. Place of Residence

The majority of respondents are from Belgrade, accounting for 78.7% of the sample, followed by Novi Sad (6.7%) and Niš (5.8%). A smaller number of participants come from other cities and municipalities, such as Valjevo, Kraljevo, Kragujevac, and several smaller towns across Serbia, none of which individually exceed 1% of the sample. This territorial distribution confirms the urban-centric nature of the study, as most respondents reside in large urban centres with a more developed real estate market and higher residential density.

4.1.5. Type and Tenure of Housing

When it comes to the type of housing, 86.4% of respondents live in apartments in multi-family buildings, while 12.4% reside in individual houses. Shared forms of housing, such as co-living spaces, are present among 1.1% of respondents, indicating a still modest but gradual trend of alternative housing forms emerging in urban areas. It should be noted that residents of single-family houses are underrepresented in the sample relative to their share in the national housing stock in Serbia. Consequently, the findings of this study primarily reflect the perceptions and experiences of apartment dwellers in urban contexts, and should be interpreted with this limitation in mind.

The housing status shows that 61.8% of participants own or co-own their apartment, 26.0% live in an apartment or house owned by family members, while 12.2% are tenants. This structure confirms the long-standing dominance of the ownership model as a key form of housing security in post-socialist Serbia, while simultaneously reflecting the presence of more flexible forms of housing tenure.

4.2. Physical and Typological Characteristics of Dwellings

Analysis of the physical and typological characteristics of apartments includes data on the period of construction, spatial size, layout, floor level, duration of residence, and the degree of space adaptation. This information provides insight into the actual living conditions and how the existing housing stock is utilized and adjusted to household needs. It enables an understanding of the relationship between building age, apartment size, and patterns of space use, which serves as an important framework for interpreting perceptual indicators of housing quality in the following sections.

4.2.1. Year of Construction

The largest share of respondents lives in buildings constructed after 2000 (36.4%), corresponding to the contemporary period of intensive private development, characterized by a higher volume of construction, smaller average apartment sizes, and increased population density. Next are buildings from the period 1975–1990 (28.4%), representing the final phase of socialist housing construction, notable for rational layouts and clear functional organization. Buildings from 1951–1974 (21.6%) include typical examples of Yugoslav modernism, whose spatial quality is still recognized today through better lighting, proportions, and clearly defined residential zones. A smaller share of respondents lives in buildings from 1991–2000 (6.0%), while 5.8% reside in buildings older than 1950, which belong to the older urban stock and are often reconstructed or adapted (

Figure A1b).

4.2.2. Household Size and Composition

The household structure shows that almost one-third of respondents (28.9%) live in two-person households, 27.3% in three-person households, while four-person households account for 22.9% of the sample. Single-person households represent 13.8%, and households with five or more members constitute 7.1%. This distribution confirms the predominance of small and medium-sized households, which aligns with contemporary urban patterns and demographic trends of decreasing family size (

Figure A1a).

When it comes to apartment size, the largest share of respondents (33.1%) live in apartments measuring between 61 and 80 m

2, 31.1% in apartments of 41 to 60 m

2, while a slightly smaller portion (26.9%) reside in spaces larger than 80 m

2. Apartments up to 40 m

2 account for 8.9% of the sample. These data indicate the predominance of medium-sized units, which in urban areas of Serbia most often correspond to the needs of smaller family households, while larger apartments are less common. (

Figure A1c).

4.2.3. Structure and Floor Level

According to the apartment structure, the most common are two-and-a-half-room apartments (31.8%) and two-room apartments (25.3%), while three-room apartments account for 15.6% of the sample. Smaller units, such as studios, one-room, and one-and-a-half-room apartments, are represented in 16.9% of cases, whereas larger apartments (four rooms or more) comprise approximately 10.4%. This structure indicates a prevalence of more compact units that balance functionality and cost-efficiency, which is characteristic of the urban housing stock in Serbia.

In terms of floor level, more than half of the respondents (52.2%) live between the first and fourth floors, 29.3% on higher floors (fifth floor and above), 7.8% on the ground floor, while 10.7% are respondents living in individual houses. This distribution confirms that the majority of residents occupy multi-story apartment buildings, within the typical multi-family structures that dominate the contemporary urban context (

Figure A1d).

4.2.4. Length of Residence and Space Adaptations

Data on length of residence show that 38.4% of respondents have lived in their current dwelling for less than five years, 24.0% between five and ten years, while 19.3% have resided in the same space for ten to twenty years. The longest continuity of residence, over twenty years, applies to 18.2% of participants. These data indicate the dynamism of the housing market, as well as the presence of a group of long-term residents, which allows for reliable comparisons of experiences between older and newer dwellings (

Figure A1e).

When it comes to adaptations, 41.6% of respondents reported having made certain interventions in their space over time, while 58.4% did not alter the original layout (

Figure A1f). The most common types of adaptations include closing or glazing balconies (9.6%) and relocating interior walls (11.6%), with some respondents also mentioning enlarging rooms at the expense of balconies, converting living rooms into bedrooms, or combining the kitchen and dining area into a single space. These interventions reflect a pronounced need among residents to enhance everyday comfort, daylight access, and functional usability through minor spatial modifications, indicating the limited flexibility of most existing housing typologies.

Among the descriptive responses, there are also individual but noteworthy examples that illustrate creative ways of adapting the space to everyday needs:

“Enclosing the balcony and expanding the living room to gain more light and space for the dining area.”

“Converting the basement into a workspace and creating a small terrace with greenery.”

“An interior wall was moved to create an additional room.”

“Closing a door in the living room to achieve a more peaceful furniture arrangement.”

“Kitchen relocated to the living room, and the previous space converted into a children’s room.”

Such responses confirm that users do not perceive space as static, but as an adaptable framework meant to accommodate changing life needs, raising questions about the flexibility and long-term usability of apartments.

4.2.5. Use of Terraces

Regarding the use of terraces and balconies, 49.3% of respondents reported using them ‘fully according to their intended purpose,’ 18.1% ‘mostly according to their intended purpose,’ while 14.2% indicated that the terrace is used for other purposes (such as storage). A smaller number of respondents (6.4%) rated its use as minimal, and 11.9% stated that the terrace is not in use. These data indicate that terraces, although formally part of the residential space, often lose their original recreational function in practice and become secondary spaces for storage, drying laundry, or extending interior rooms. Such usage patterns reveal the complex relationship between the functional and perceived value of semi-outdoor spaces in contemporary housing.

4.3. Perception and Experience of Housing

The results of this segment of the study provide insight into the subjective evaluation of space and daily housing experience, through assessments of various aspects of spatial quality and through open-ended comments from respondents. By combining quantitative and qualitative data, it is possible to understand not only the physical conditions of housing but also the emotional and perceptual dimensions of the relationship to the home space, which reflect actual habits, satisfaction, and user expectations.

4.3.1. Natural Lighting and Ventilation

The highest average scores were given for the possibility of ventilating the space (4.36) and the amount of natural light in the apartment (4.16). These results indicate that most respondents perceive their apartments as sufficiently lit, pleasant, and well-ventilated, which is also reflected in individual comments, such as: ‘Sunny side, pleasant temperature during the day’ or ‘The apartment has plenty of light and is easy to ventilate.’ However, kitchen lighting (3.56) shows that some respondents recognize the problem of insufficient natural light in auxiliary areas, especially in smaller units of newer buildings, where direct connection with the outside space is often compromised.

4.3.2. Spatial Organization and Comfort

Functionality of room layout was rated highly, with an average score of 4.17, while spaciousness and overall comfort received a score of 3.99. However, spatial flexibility and adaptability were rated lower, with 3.57 for the possibility of rearranging furniture and 3.02 for overall space adaptability. This pattern indicates that most apartments meet basic functional needs but fall short in long-term adaptability, highlighting the limited flexibility of contemporary housing typologies. Storage space received a score of 3.43, confirming that lack of storage remains one of the most pronounced limitations of modern housing. In their comments, respondents frequently pointed out inadequate relationships between circulation areas and usable space, with examples such as: ‘Inadequate room layout, unnecessarily large hallway’ or ‘Noise, poor layout, and difficulties maintaining comfort, especially in the living room.’

4.3.3. Privacy, Quality, and Maintenance

Ability for privacy for all household members received an average rating of 3.98, suggesting that most apartments provide a satisfactory level of personal space, although some comments indicate compromised privacy due to room connectivity via the living room or lack of additional circulation in larger apartments. The quality of materials and finishing was rated 3.62, reflecting moderate satisfaction and notable differences between newer and older buildings: older buildings are recognized for stability and durability, while newer ones receive more comments on poor finishes and faster material wear. Aspects of thermal comfort and space maintenance were rated relatively high, with average scores of 3.81 for heating and cooling capability and 4.10 for ease of maintenance.

Overall satisfaction with housing is 3.97, which can be interpreted as a moderately positive attitude among respondents, reflecting high ratings for functional and physical conditions of the space while retaining critical assessments regarding adaptability, material quality, and acoustic comfort. These findings confirm that housing in Serbia continues to exhibit an ambivalent relationship between functional fulfillment and the emotional experience of home, where quality of life is determined not solely by spatial parameters but also by the space’s ability to support stability, privacy, and a sense of long-term comfort (

Figure A2).

4.4. Qualitative Insights and Interpretations

Open-ended questions in the survey allowed respondents to freely describe the advantages and disadvantages of their apartments, as well as to express their personal relationship with their living space. Analysis of the descriptive responses identified several recurring themes that complement the quantitative findings and provide deeper insight into the everyday perception of housing quality in the urban context of Serbia.

The most frequently highlighted advantages relate to good natural lighting, a functional layout, and a pleasant orientation of the apartment, mentioned in more than two-thirds of respondents’ answers. Comfort, ventilation, and energy efficiency are cited as additional benefits by approximately half of the participants. More than two-thirds of respondents emphasize that the apartment has abundant natural light and good ventilation, with comments often including phrases such as: ‘the apartment receives enough light throughout the day,’ ‘dual orientation allows for easy ventilation,’ or ‘large windows provide a sense of openness.’ About one-third of respondents also highlight a quiet orientation of the apartment as an important condition for acoustic comfort and privacy.

On the other hand, the most frequently observed drawbacks include a lack of natural light and ventilation (around 35% of respondents), poor acoustic and thermal insulation (about 30%), as well as insufficient storage space and inadequate room layout (approximately 40%). About one-fifth of participants also report limited possibilities for adaptation and reconfiguration, further highlighting the issue of low spatial flexibility in contemporary apartments. Common comments include: ‘not enough closets,’ ‘hallway takes up too much space,’ ‘kitchen lacks natural ventilation,’ or ‘noise from neighboring apartments reduces privacy.’ A particular concern is the connection of bedrooms through the living room and the loss of privacy in open-plan new constructions, which users often identify as compromising intimacy and disrupting the internal spatial hierarchy.

The category of adaptations and improvisations occupies a significant place in the qualitative responses. Many participants report minor or major interventions in which they altered the original spatial organization, ranging from enclosing balconies and expanding living rooms to combining the kitchen and dining area or creating new rooms with partitions. Such interventions demonstrate a high degree of user engagement in shaping the space, but also indicate insufficient flexibility in contemporary apartments. Comments frequently emphasize that adaptations were ‘necessary for functionality’ or ‘essential to accommodate the needs of children.’

A significant number of comments also address the quality of construction and materials, with respondents clearly distinguishing between older and newer buildings. Older apartments are described as ‘better designed,’ ‘more airy,’ and ‘durable,’ whereas newer ones are often characterized as ‘too cramped’ or ‘built with low-quality materials.’ One participant notes: ‘The old apartment has a rational layout and good insulation, while the new construction feels more confined and is finished poorly.’

In a smaller number of comments, social-emotional aspects of housing emerge, such as relationships with neighbors, a sense of community belonging, and identification with the place. Some respondents note that ‘proximity to green spaces and the presence of neighborly solidarity’ contribute more to quality of life than the apartment’s size itself, while others highlight the ‘isolation in new residential complexes.’

5. Analysis and Interpretation of Results

Previous insights indicate that housing comfort is determined not solely by physical dimensions and technical standards, but primarily by the quality of spatial organization and the adaptability of the space to household needs. Respondents most frequently highlight natural light, quietness, and a sense of privacy as key indicators of satisfaction, while the aesthetic and material characteristics of the dwelling are perceived as secondary. These findings set the stage for a deeper statistical analysis of the interrelations between physical, typological, and perceptual parameters of housing quality, which follows in the next section of the chapter.

Based on the results presented in the previous chapter, it can be observed that respondents most positively evaluate the lighting, functionality, and overall comfort of older apartments, whereas newer housing stock performs better in aspects of thermal comfort and maintenance. These initial observations indicate that spatial quality has a longer-term influence on the perception of satisfaction than material-technical factors, which constitutes the main hypothesis that is further analytically tested.

These findings are consistent with observations reported in international literature on housing quality and dwelling satisfaction. Similar patterns, where spatial organisation and adaptability outweigh purely technical parameters, have been identified in post-socialist contexts such as Croatia and Poland, as well as in studies conducted in Asia and the Middle East [

12,

14,

15,

38,

39,

40]. In these studies, rational layouts, access to natural light, and flexibility of space are repeatedly highlighted as core determinants of long-term residential satisfaction, regardless of construction period or technological advancement. This correspondence supports the relevance of the present findings within broader global discussions on housing design standards and user-oriented residential quality.

Analysis is organized into three segments: physical and spatial relations, perceptual and emotional indicators, and a summary interpretation of the results in relation to the hypothesis.

5.1. Analysis of the Relationships Between Physical Characteristics and the Perception of Dwelling Quality

This segment examines the relationship between the objective physical characteristics of dwellings (construction period, area, layout, length of occupancy, adaptations) and subjective indicators of satisfaction (comfort, lighting, functionality, adaptability). The aim is to identify which variables most strongly influence the perception of dwelling quality and to what extent spatial organization outweighs technical and material parameters.

5.1.1. Relationship Between the Construction Period and the Perception of Dwelling Quality

This relationship allows for examining the differences between three main groups of dwellings: those from the period 1951–1990, after 2000, and before 1950. The construction period of the apartment shows a significant impact on the perception of lighting, thermal comfort, and ease of maintenance, while differences in functionality and adaptability are less pronounced.

A statistically significant negative correlation was found between the building’s construction period and residents’ perception of natural lighting in the kitchen using Spearman’s correlation (rs = −0.123,

p < 0.01) and further confirmed by Fisher’s Exact Test (Monte Carlo method) (

p = 0.028), with a significant negative linear trend (

p = 0.009). Respondents living in apartments built after 2000 show, on average, a substantially lower level of satisfaction with kitchen lighting (3.3) compared to those in older housing stock (3.6–3.8) (

Figure 1b). Although residents of buildings from the 1991–2000 period display a high average level of satisfaction with this aspect, this category also shows a notable proportion of dissatisfied and very dissatisfied respondents (cumulatively about 26%) (

Figure 1a).

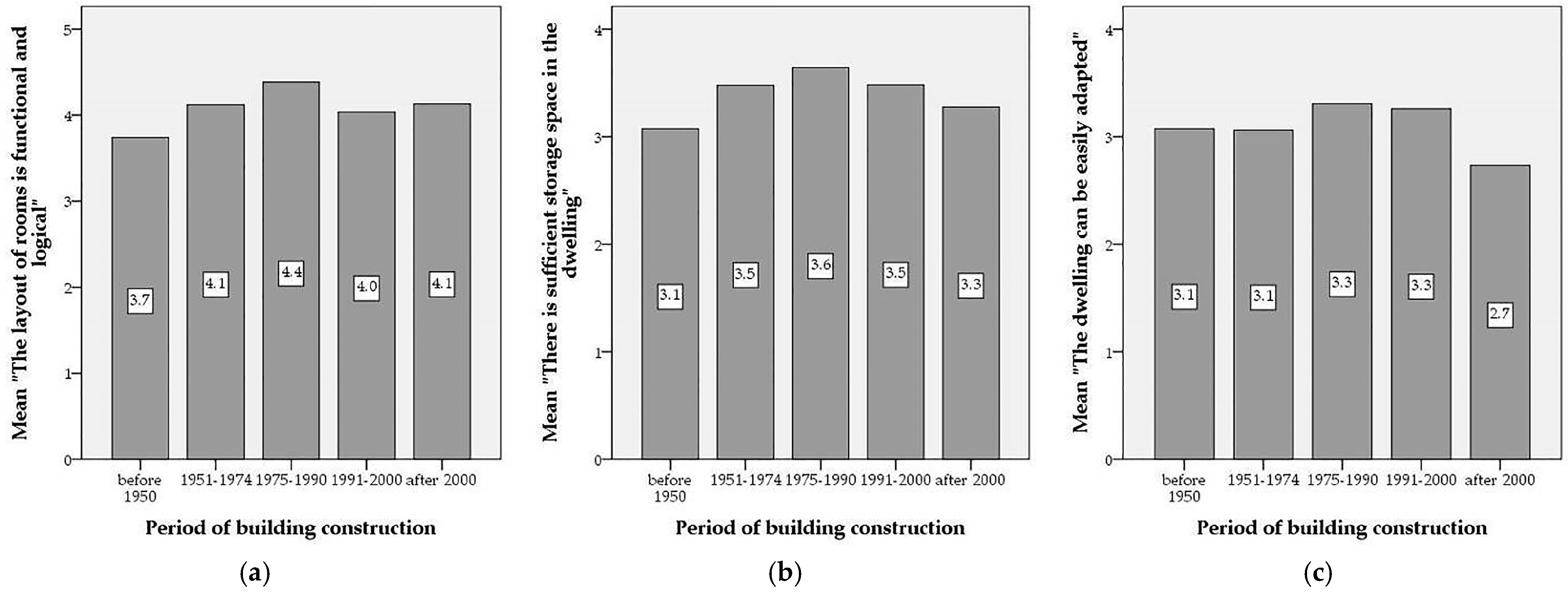

Although Spearman’s correlation and the Chi-square test of independence did not reveal a statistically significant relationship between the dwelling’s construction period and several examined aspects of spatial-functional quality, it can be observed that respondents living primarily in newer socialist-era housing (1975–1990) show, on average, slightly higher levels of satisfaction with the overall functional characteristics of the dwelling (4.4), available storage space (3.6), and the ease of dwelling adaptability (3.3) compared to respondents in other categories (

Figure 2a–c).

On the other hand, as expected, newer housing stock (post-2000) showed higher levels of resident satisfaction with the material-technical aspects of dwellings, such as the ease of maintenance and heating/cooling.

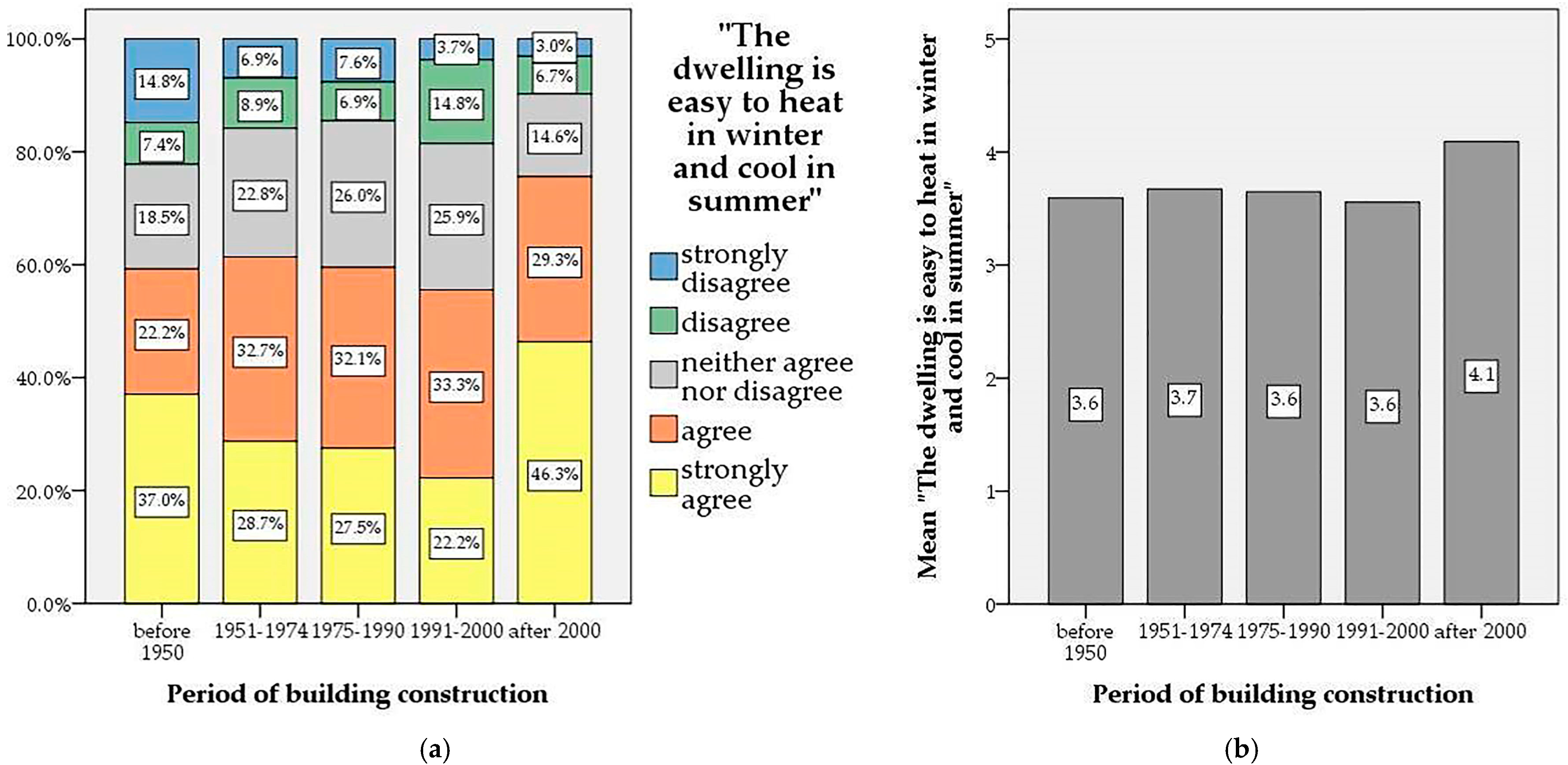

A statistically significant positive correlation was found between the construction period of the dwelling and residents’ perception of its thermal comfort, using Spearman’s correlation (rs = 0.156,

p < 0.01) and additionally Fisher’s Exact test (Monte Carlo method) (

p = 0.043), with a significant linear trend (

p = 0.001). Residents living in dwellings built after 2000 reported a notably higher average level of satisfaction with this aspect (4.1) compared to those residing in older housing stock (3.6–3.7) (

Figure 3b). Conversely, the highest level of dissatisfaction was observed among occupants of the oldest housing stock (pre-1950), consistent with its very low energy efficiency (

Figure 3a).

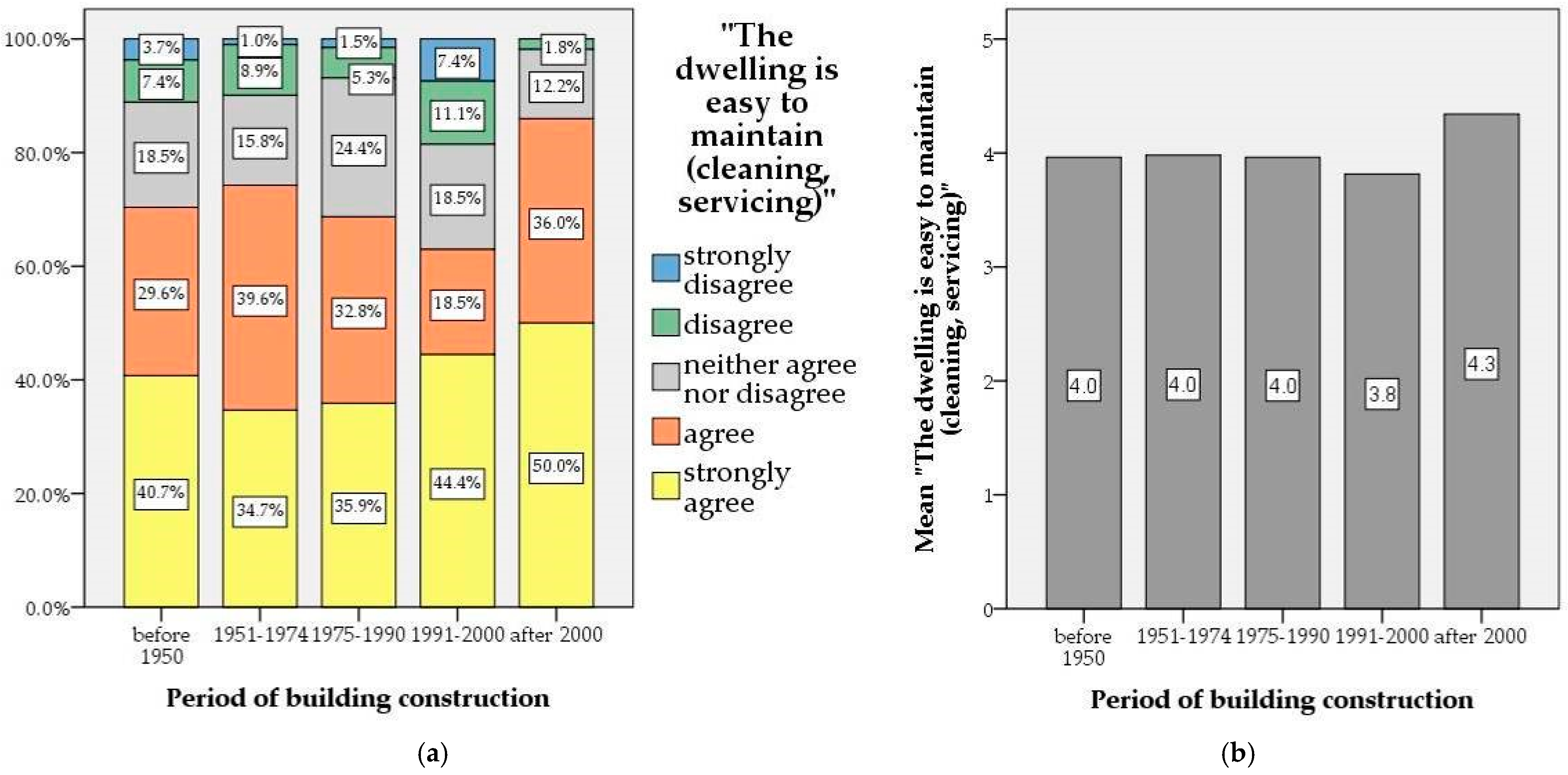

Similarly, a positive correlation was found between the construction period of the dwelling and the perception of ease of maintenance, using Spearman’s correlation (rs = 0.149,

p < 0.01) and additionally Fisher’s Exact test (Monte Carlo method) (

p = 0.002), with a significant linear trend (

p = 0.001). The average rating for this aspect among residents of apartments built after 2000 is 4.3, while in other categories it ranges from 3.8 to 4.0. Interestingly, apartments constructed between 1991 and 2000 received the lowest average rating (3.8) and the highest reported overall dissatisfaction (18.5%), which may indicate a lower quality of materialization in early post-socialist housing stock (

Figure 4a,b).

Dwellings from the early post-socialist period (1991–2000) stand out with lower maintenance ratings (3.8) and the highest proportion of dissatisfied residents (18.5%), indicating transitional construction quality during that period. Older apartments receive higher scores for functionality and lighting, while new construction leads in technical and energy-related aspects, confirming the hypothesis regarding the lasting value of the spatial logic of socialist-era housing. Comparable conclusions have been drawn in studies of post-socialist housing in Croatia and other Central and Eastern European countries, where apartments from the socialist period are often assessed as spatially more legible and adaptable than newer developments [

12,

14,

15]. Similar tendencies have also been reported in housing studies from Asian and Middle Eastern contexts, where compact contemporary apartments frequently demonstrate reduced flexibility and daylight access due to market-driven densification and regulatory constraints [

38,

39,

40].

The observed difference between general and localized lighting indicates that perceived light quality is related to typological structure and construction period. Newer apartments, particularly those built after 2000, more often feature reduced openings and more complex internal layouts, leading to decreased natural light availability in secondary areas, especially kitchens and dining rooms.

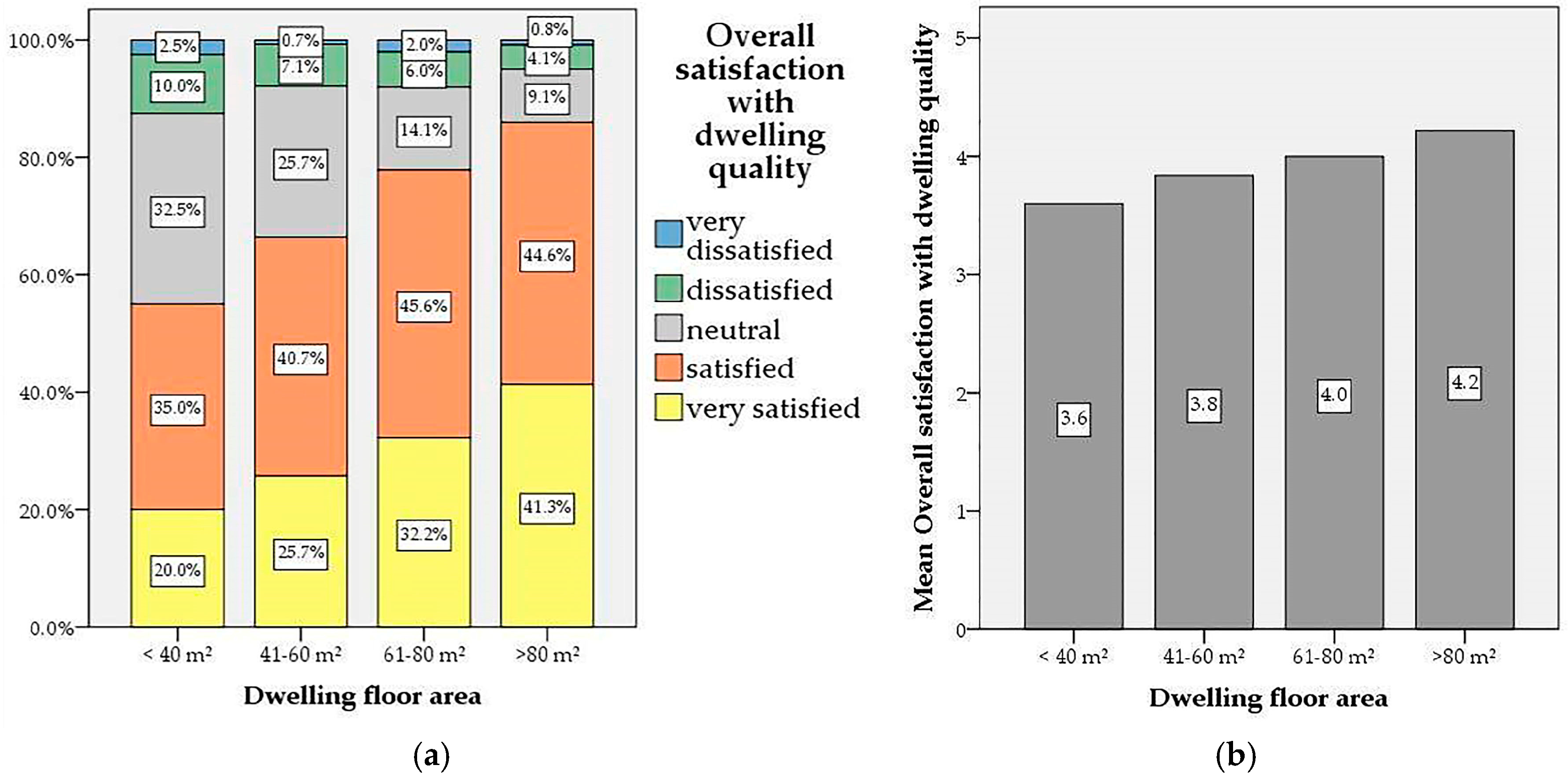

5.1.2. Relationship Between Dwelling Size and Perceived Comfort

The analysis results indicated that dwelling size affects both the overall level of residents’ satisfaction with dwelling quality and several spatial aspects of their perception of residential comfort. A small positive Spearman correlation was identified between the variables of overall satisfaction with dwelling quality and its size (rs = 0.209,

p < 0.01) (see

Figure 5a,b). Simultaneously, significant positive correlations were observed between dwelling size and variables such as room spaciousness (rs = 0.379,

p < 0.01), privacy for household members (rs = 0.358,

p < 0.01), apartment adaptability (rs = 0.304,

p < 0.01), and adequacy of storage space (rs = 0.211,

p < 0.01) (see

Figure 6a–d). The statistical significance of these positive relationships was also confirmed using the Chi-square test of independence (and Fisher’s Exact test).

When considering the above variables together with the building’s construction period, the following specific characteristics can be observed for smaller or medium-sized dwellings (up to 60 m2):

The average satisfaction rating of respondents regarding the ease of adapting these 41–60 m2 is lower for units built in the 1991–2000 and post-2000 periods (2.3 in both cases) compared to apartments from earlier construction periods (2.6–2.9), and especially compared to those from the 1975–1990 period (2.9);

The adequacy of storage space in 41–60 m2 apartments is rated lower for units built before 1950 (2.2) and for those constructed after 2000 (3.1), compared to apartments from the socialist and early post-socialist periods (3.4–3.7). Moreover, the quality of storage areas is also rated lower in 61–80 m2 apartments built after 2000 (3.1) compared to units from earlier periods (3.7–4.0);

In contrast, household privacy is rated higher in newer apartments (after 2000) with an area up to 40 m2 (3.5) compared to units from earlier periods (2.3–3.3), which aligns with the current trend of subdividing apartment layouts to provide separate bedrooms at the expense of space for daily activities.

Apartment size remains one of the most important factors of satisfaction, but the area alone does not guarantee quality. Spatial organization, the relationships between zones, flexibility, and adaptability to household needs are decisive.

Analytically, the observed correlation between the perception of functionality and the sense of comfort indicates that the spatial organization of the apartment also has an emotional dimension. Users associate rational and clear layouts with comfort and stability at home, while a lack of flexibility or storage space induces frustration and a sense of spatial limitation.

5.1.3. Relation Between the Perception of Comfort and the Quality of Materials

The perception of the quality of materials and finishing in residential buildings is positively correlated with several factors of perceived housing quality and residential comfort, with a particularly strong positive impact on overall satisfaction with the apartment quality (rs = 0.596, p < 0.01), ease of heating/cooling the apartment (rs = 0.495, p < 0.01), and maintenance (rs = 0.329, p < 0.01), as well as on predominantly spatial and functional aspects such as room spaciousness (rs = 0.374, p < 0.01) and privacy (rs = 0.365, p < 0.01). However, the average subjective rating of material and finishing quality is not directly related to the construction period of the apartment (ratings are almost uniform across categories), which does not allow for conclusions about the influence of this variable on the perception of housing quality for apartments with different spatial-functional characteristics.

The analysis of the relationships between the apartment’s construction period and residents’ perceptions of various aspects of apartment quality did not reveal a large number of statistically significant associations. No effect of the construction period on overall satisfaction with apartment quality was identified. Overall resident satisfaction with apartment quality and various aspects of residential comfort is primarily influenced by the apartment’s size (and layout). However, a slightly higher level of satisfaction was observed among respondents living in newer socialist-era housing (1975–1990) regarding general functional characteristics, available storage space, and ease of adaptation, compared to respondents in other categories. Conversely, in the newer housing stock (post-2000), average ratings for natural kitchen lighting, adaptability of apartments, and adequacy of storage space were lower (

Table 1). This pattern of findings suggests that the perception of housing quality in the contemporary Serbian context does not strictly depend on the building’s age, but rather on the relationship between spatial organization, apartment size, and adaptability. In other words, apartments from the socialist construction period retain a reputation for spatially rational typologies precisely because they offer a balance between functionality and flexibility of space.

Based on the previously presented indicators, it can be observed that users highly value the stability of basic physical conditions but also recognize the limitations of new constructions in terms of material quality and finishing. Although newer apartments are perceived as easier to maintain and more energy-efficient, respondents frequently report a sense of reduced durability and superficiality in construction, indicating a gap between technical standards and the perceived quality of space.

5.2. User Patterns and Spatial Adaptation

This section examines the active role of users in shaping and adapting space, that is, how apartments are used, modified, and transformed according to the real needs of households. The aim is to demonstrate that contemporary apartments often require adaptations, as they lack sufficient spatial flexibility or reserve capacity for changes over time. The essence of this section is to emphasize that the quality of a home is not exhausted by its designed dimensions and layout, but is shaped through use, adaptation, and personalization of the space.

5.2.1. Relationship Between Adaptations and the Perception of Comfort

This relationship illustrates how active interventions in the living space affect the perceived quality. Apartment adaptations, i.e., adjustments of the residential space to the individual needs of the occupants, showed significant dependence on the variables of building construction period as well as the duration of residence in the current apartment. The Chi-square test of independence indicated a strong and statistically significant association between the variable of apartment adaptation and the building construction period, χ

2(4, N = 450) = 44.89,

p < 0.001, as well as a significant association with the duration of residence in the current apartment, χ

2(3, N = 450) = 18.70,

p < 0.001. It can be concluded that older apartments are generally modified and adapted to occupants’ needs to a greater extent, and that longer residence periods also result in more frequent adaptations, which aligns with changing spatial requirements as well as household size and composition (

Figure 7a,b).

Although no statistically significant association was found between adaptation and apartment size, it is observed that larger apartments are adapted to a greater extent compared to smaller ones −47.1% (>80 m2), 42.3% (61–80 m2), 38.6% (41–60 m2), and 32.5% (<40 m2). When examined by apartment size, a relative uniformity in the types of applied adaptations can be observed, with a high proportion of interventions such as moving interior walls, closing/glazing balconies, and combinations of multiple intervention types. Additionally, in apartments smaller than 40 m2, a common form of adaptation (7.5%) involves converting the living/dining/kitchen area into a bedroom.

Fisher’s exact test (Monte Carlo) showed a significant association between the building’s construction period and the use of terraces/balconies according to their intended purpose, p = 0.016, with a significant linear trend (p = 0.004). According to user reports, the average rating for terrace/balcony use according to its intended purpose is notably higher in apartments built after 1975 (4–4.1) compared to apartments from earlier periods (3.4).

Considering the construction period of the apartments, it can be observed that converting living spaces or terraces into bedrooms is frequently applied in apartments from the socialist period (1951–1990) as well as in new constructions (post-2000), while room expansions at the expense of terraces are particularly common in early socialist period apartments (around 27%). On the other hand, apartments from the early post-socialist period (1991–2000) show a higher incidence of combined types of interventions (around 30%), whereas in the oldest housing stock (pre-1950), internal wall modifications (around 34%) and combined interventions (around 26%) are most prevalent.

The Chi-square test of independence did not reveal a statistical dependence between the implementation of apartment adaptations and respondents’ satisfaction with the quality of the apartment, or with various aspects of perceived residential comfort. A significant association of the adaptation variable was observed only with respondents’ perception of the ease of apartment adaptability, χ2(4, N = 450) = 21.34, p < 0.001.

5.2.2. Relation Between Length of Residence and Dwelling Satisfaction

Tests conducted did not confirm a significant relationship between length of residence and perception of comfort, indicating that emotional attachment to the home does not necessarily correlate with the duration of occupancy. Similarly, Spearman’s correlation and the Chi-square test of independence did not reveal a statistically significant relationship between the period of residence in the current apartment and respondents’ perception of housing comfort, functionality, or overall satisfaction with the quality of the apartment.

5.3. Emotional and Perceptual Aspects of the Dwelling

This section provides interpretative depth to the study, as it relates to the sense of belonging, identification with space, and preferences for future housing. It thus brings the discussion back to the broader framework of the hypothesis: why older apartments are perceived as ‘higher quality’ and how this perception transcends purely functional and technical parameters.

5.3.1. Relation Between Ownership Type and Dwelling Perception

The Chi-square test of independence showed a statistically significant association between housing tenure and overall satisfaction with the apartment, χ

2(8, N = 450) = 22.08,

p = 0.005, confirmed by Fisher’s Exact Test (Monte Carlo,

p = 0.002). The highest average satisfaction score was recorded among apartment owners (4.1), slightly lower among occupants due to kinship (apartments owned by family members) (3.9), and lowest among tenants (3.5). This indicates that high satisfaction among owners stems not only from the qualitative aspects of the apartment but also from the sense of long-term stability, identification, and autonomy in the space (see

Figure 8).

5.3.2. The Relationship Between Future Housing Preferences and the Perception of the Current Space

An investigation of preferences for purchasing a potential future apartment, with the offered options being: 1—a newly built apartment (after 2000), 2—a well-adapted apartment from the socialist period (1950–1990), 3—undecided, and 4—no significant difference, yielded highly indicative results for the initial research hypothesis.

A Chi-square test revealed a highly statistically significant association of this variable with the building construction period, χ

2(12, N = 450) = 90.22,

p < 0.001, further confirmed by Fisher’s Exact test (Monte Carlo method) (

p = 0.000). It can be concluded that the majority of respondents living in apartments built before 1950 (74.1%), as well as those from both socialist periods (68.3% and 67.9%, respectively) and the early post-socialist period (70.4%), expressed a preference for well-adapted apartments from the socialist period. At the same time, approximately 30.5% of respondents living in newly constructed apartments after 2000 also expressed a preference for this type of apartment (

Figure 9a).

Particularly noteworthy is the statistically significant association of this variable with respondents’ housing status, χ

2(6, N = 450) = 18.35,

p = 0.005, which indicates a strong preference among tenants and family-based occupants for well-adapted apartments from the socialist period (67.3% and 63.2%, respectively). This can be partially interpreted as reflecting their greater objectivity in evaluating apartment quality and their richer user experience (

Figure 9b).

As shown by the descriptive results presented in the previous chapter, natural lighting, ventilation, and acoustic protection are recognized as key factors of subjective comfort, often more important than the number of rooms or total floor area. These findings indicate that the perception of home quality goes beyond technical parameters and intertwines emotional and sensory experiences of living. The ambivalent attitude of users toward contemporary housing, simultaneously satisfaction with basic comfort conditions and awareness of limitations in flexibility and privacy, confirms the complexity of the relationship between functional and emotional quality of space. Such findings align with international research that increasingly emphasizes the integration of emotional, sensory, and experiential dimensions into housing quality assessment frameworks, reflecting a shift in global housing design standards toward user-centered and experience-based evaluation models [

42,

43,

44,

45,

46].

6. Discussion

The discussion represents the final step in testing the initial hypothesis, according to which older housing stock, particularly apartments from the socialist construction period, achieves a more balanced relationship between spatial organization, functionality, and everyday comfort compared to newer housing developments. This chapter interprets the findings obtained through the analysis of relationships between physical characteristics, perceptions of quality, and emotional aspects of housing. The aim is not only to confirm or refute the hypothesis but also to understand the causes of these perceptions, their social grounding, and possible implications for contemporary architectural practice and housing policy.

6.1. Spatial and Functional Quality Across Construction Periods

The research results indicate that the perception of housing quality is not directly linked to the construction period, but rather to spatial organization and typological patterns of apartments. It was found that higher levels of resident satisfaction with apartment quality and various aspects of housing comfort are directly conditioned by larger apartment size, as also demonstrated in previous studies on housing satisfaction among young people in Serbia [

34]. However, this study highlights a number of subtler relationships between user satisfaction and characteristics of housing space in the post-socialist context. The data suggest that apartments from the 1950–1990 period consistently achieve higher ratings for natural lighting, ventilation, and functional layout, while newly constructed apartments receive higher average scores for thermal comfort, energy performance, and ease of maintenance. This relationship indicates that the qualitative experience of home is not primarily based on technical standards, but on a spatial logic that enables usability and comfort over an extended period. These results confirm that the spatial design principles characteristic of socialist housing, such as dual-aspect orientation, rational relationships between circulation and usable areas, and moderate, clearly defined spatial zones, still provide an optimal framework for contemporary housing needs. Although newer apartments are more energy-efficient and often equipped with modern installations, their reduced area and fragmented room organization limit spatial flexibility and individual adaptation. This perception is not a result of nostalgia for the past but a rational assessment of spatial structure and the quality of life it affords. The “socialist apartment” model is therefore seen not ideologically, but as functionally optimal, achieving a balance between privacy, lighting, and ventilation, directly influencing the daily sense of comfort. These insights indicate that housing quality cannot be reduced to measurable technical parameters but arises from the durability of spatial logic and its capacity to maintain functional and emotional equilibrium over time.

6.2. User Patterns and Spatial Adaptation

One of the key findings of the study relates to the active role of residents in maintaining and enhancing the quality of their housing. The results indicate that longer periods of occupancy are associated with more frequent spatial interventions by users, reflecting their changing needs, which confirms the importance of spatial flexibility for the long-term sustainability of housing. Apartments from the 1975–1990 period proved particularly suitable for adaptations, as they combine rational layouts and clearly defined spatial units with the possibility of achieving new functional qualities through partitioning or merging rooms. In contrast, newer apartments, often reduced to minimal floor areas, exhibit a lower degree of adaptability because their organization is designed at the limit of spatial capacity, without reserve potential to accommodate changing household needs. These findings suggest that housing quality is not a fixed but a dynamic category, shaped through daily use and the residents’ relationship with the space. The role of the user does not end at the moment of moving in but continues throughout the home’s life cycle, where every intervention, moving walls, enclosing terraces, or merging rooms, represents a form of personalization and appropriation of space. In this sense, adaptability is not only a technical but also an emotional parameter, reflecting the space’s capacity to respond to changes in life rhythms, family structure, and personal habits of the occupants.

6.3. Emotional and Perceptual Aspects of the Home

Analysis of the perceptual and emotional dimensions of housing shows that satisfaction with space arises not only from its functional organization but also from the subjective values that residents associate with the concept of ‘home.’ This is evidenced by the higher overall satisfaction with apartment quality reported among homeowners. Moreover, most respondents emphasize a sense of calm, light, and privacy as key indicators of housing quality, while technical standards, energy efficiency, or material fittings play a secondary role. These findings confirm that housing in the contemporary Serbian context is still experienced as an emotionally grounded category—a space of security, continuity, and personal identification. Notably, even among residents of newly built apartments, there is a pronounced preference for apartments from the socialist construction period, indicating the existence of a collective model of the ‘good apartment’ transmitted across generations. This model is based on spatial rationality, clarity of organization, and the possibility of privacy, values that surpass technical advancements and changes in the housing market logic. In this sense, the home functions as a complex emotional framework, where daily routines, memories, and social interactions intersect. Consequently, housing quality is determined not only by the architect but also by the resident through usage, adaptation, and emotional investment in the space. This approach opens the possibility of rethinking architecture as a means of shaping social relationships, rather than merely a technical discipline of spatial design.

The obtained results confirm that housing quality in the contemporary Serbian context cannot be measured solely by technical and economic parameters; rather, the crucial factors are the relationship between spatial structure, emotional stability, and the potential for long-term usability of the space. The older housing stock demonstrates that the fundamental principles of rational planning, clear zoning hierarchy, adequate lighting, spatial efficiency, and adaptability, remain the cornerstone of good design. These insights indicate the need for contemporary housing policy, urban planning, and architectural practice to refocus on user experiences and actual patterns of daily life. Based on the empirical findings, three directions for future action can be identified:

improvement of micro-apartment design through more flexible typologies,

redefining minimum spatial standards in accordance with actual living needs, and

incorporating perceptual and emotional parameters into the evaluation of housing quality.

On a broader level, the study shows that residential architecture has the potential to contribute not only to spatial but also to social quality of life. To the extent that it enables a sense of belonging, security, and mutual respect, it becomes a means of creating community and a sustainable urban environment, where space connects rather than separates people.

7. Conclusions

The study aimed to examine the perception of housing in the urban context of Serbia by linking physical, functional, and emotional parameters of spatial quality. Particular emphasis was placed on testing the hypothesis that older types of apartments, especially those from the socialist construction period (1950–1990), still achieve a higher level of spatial and functional quality compared to new developments, despite technical obsolescence and lower energy standards. The analysis focused on a comparative evaluation of dwellings from different construction periods, examining how spatial organisation, adaptability, lighting and perceived comfort relate to residents’ overall assessment of housing quality.

Based on the quantitative and qualitative analysis of the collected data, the following key insights can be identified:

Spatial organisation emerged as the dominant factor in housing quality assessment, outweighing material finishes and technical equipment across all respondent groups. Regardless of the construction period, respondents consistently valued a rational layout, dual orientation, lighting, and ventilation of the space more than the material characteristics of the building.

Older housing stock consistently elicits a positive experience. Apartments from the period 1950–1990 were rated as more functional, better lit, and more pleasant for daily living, confirming the long-term sustainability of their typological solutions, particularly in terms of room layout, natural lighting and perceived usability of shared and circulation spaces.

Newly constructed housing offers technical advantages but lacks spatial flexibility. Although respondents positively evaluate the thermal comfort and ease of maintenance of newer apartments, their reduced floor area and fragmented room layout limit the potential for spatial flexibility and long-term adaptation.

Residents actively shape the quality of their housing. More than 40% of respondents reported carrying out minor or major adaptations of their living space, confirming that tailoring the home to actual needs is a key mechanism for achieving comfort and emotional stability.

The emotional dimension of housing retains lasting significance. Most respondents associate housing quality with a sense of peace, light, stability, and belonging, confirming that the ‘home’ transcends material boundaries and functions as a psychological and social framework for life.

The results confirm the initial hypothesis that a positive perception of housing quality in Serbia remains associated with apartments from the socialist construction period. Their advantage does not stem from technical execution quality, but from a spatial logic that enables better natural lighting, clarity of layout, and adaptability. Consequently, the main research objectives were achieved: empirically demonstrating the relationship between the physical characteristics of space and the subjective perception of housing quality, and confirming the importance of architectural spatial organization as a key factor in everyday comfort. The hypothesis is thus confirmed in a partially modified form: while older housing stock exhibits higher spatial quality, newer apartments achieve better technical performance, indicating that the optimal model of contemporary housing must integrate these two dimensions—spatial rationality and technical efficiency. This finding underscores the central role of spatial configuration as a lasting determinant of housing quality, regardless of construction period or technological advancement.

Based on the empirical findings of the study, several practical recommendations for contemporary housing design and housing policy can be formulated:

Housing design should take into account minimum spatial standards that ensure spatial adaptability and explicitly integrate emotional aspects into the assessment of housing quality, rather than relying solely on quantitative or technical performance indicators.

Minimum spatial standards should prioritise functional layout over mere floor area, ensuring a clear room organisation, sufficient circulation space, and the possibility of multiple functional uses within individual rooms.

Adaptability should be treated as a core design criterion, enabling future spatial modifications without major structural interventions, in response to changing household structures and life cycles.

Natural lighting and dual orientation should be systematically integrated as key determinants of residential quality, given their strong influence on perceived comfort and everyday usability.

Emotional aspects of dwelling, such as the sense of privacy, stability, and belonging, should be explicitly considered in housing design, alongside technical and regulatory requirements.

Housing policies and design guidelines should be informed by post-occupancy and user-based research, rather than relying exclusively on normative standards or market-driven optimisation.

This research represents a contribution to the empirical knowledge base on contemporary housing in Serbia by providing a systematic insight into users’ perceptions of the spatial strengths and shortcomings of the existing housing stock. By linking quantitative survey results with qualitative interpretations, the study enables a clearer understanding of how objectively defined spatial characteristics influence the subjective experience of dwelling. The findings allow for comparability with similar studies in post-socialist contexts and support the development of design standards and housing policies grounded in user experience rather than solely in normative or market-driven criteria. By systematically linking user perception with objectively defined spatial characteristics, the study provides an empirical framework that can directly inform both architectural design practice and housing policy development.