Deformation Mechanism and Adaptive Measure Design of a Large-Buried-Depth Water Diversion Tunnel Crossing an Active Fault Zone

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Characteristics of the Active Fault Zone

3. Geostress Field of the Engineering Area

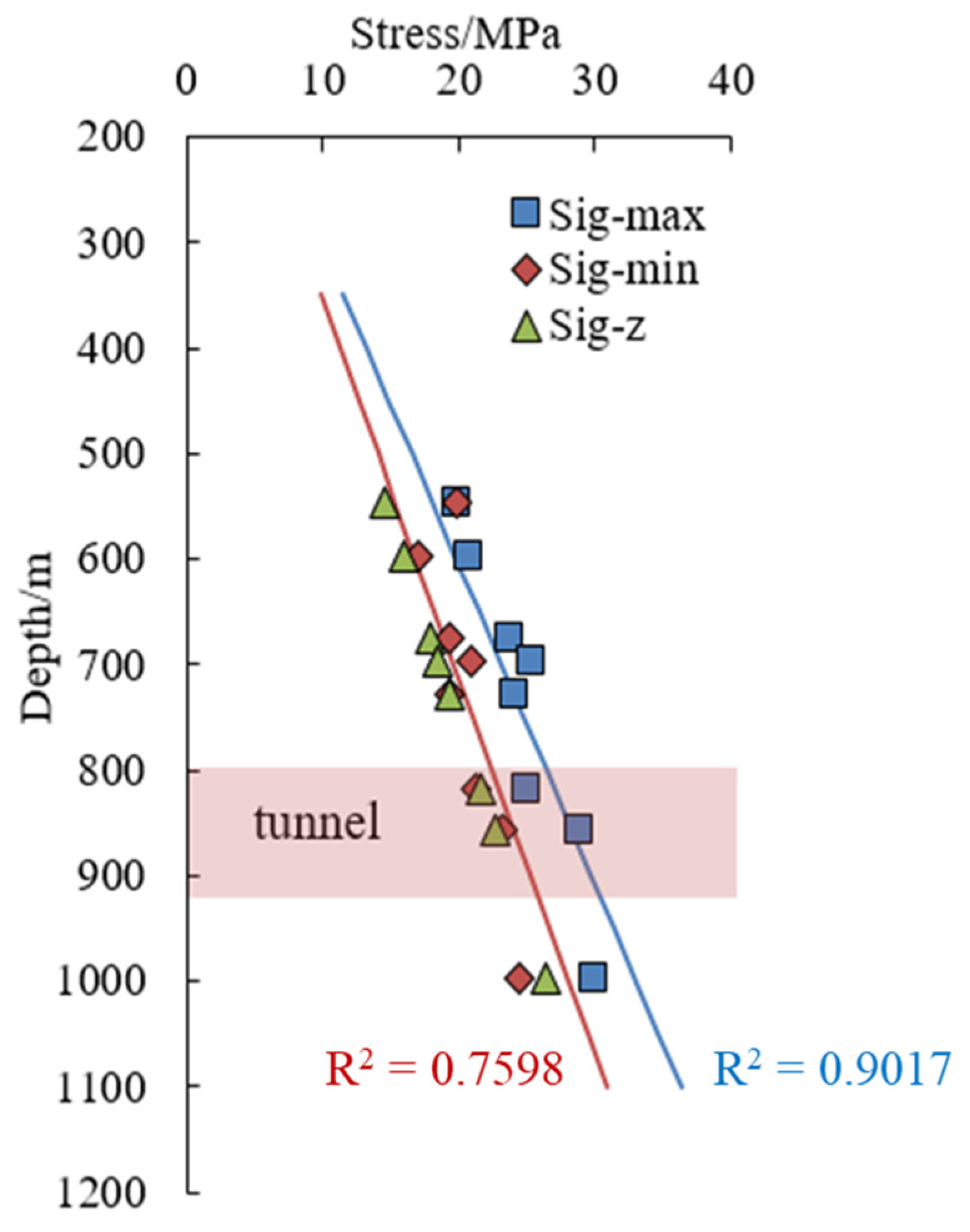

3.1. Geostress Test Data

3.2. Geostress Regression

4. Response Characteristics of Lining Structure Under Active Fault Dislocation

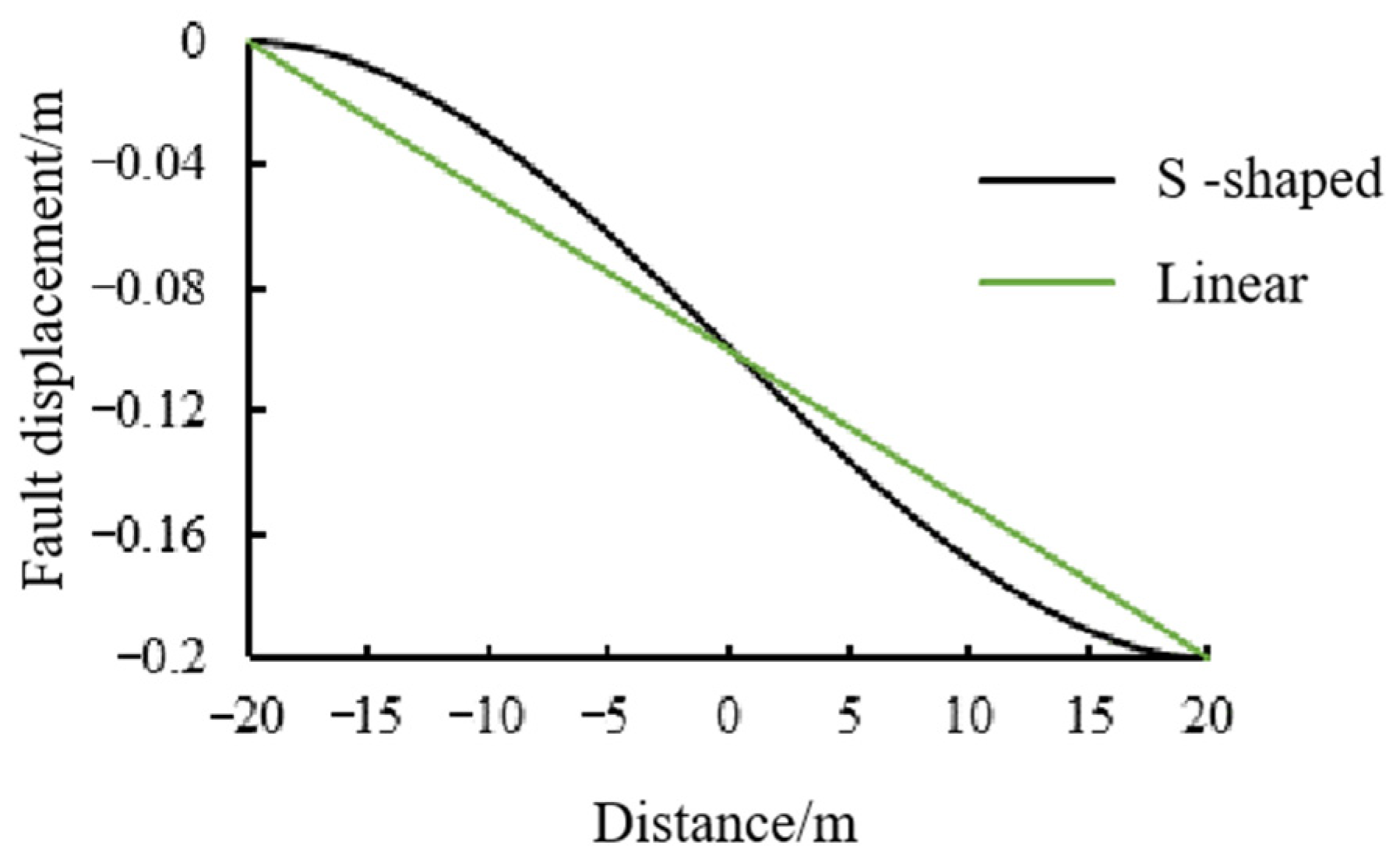

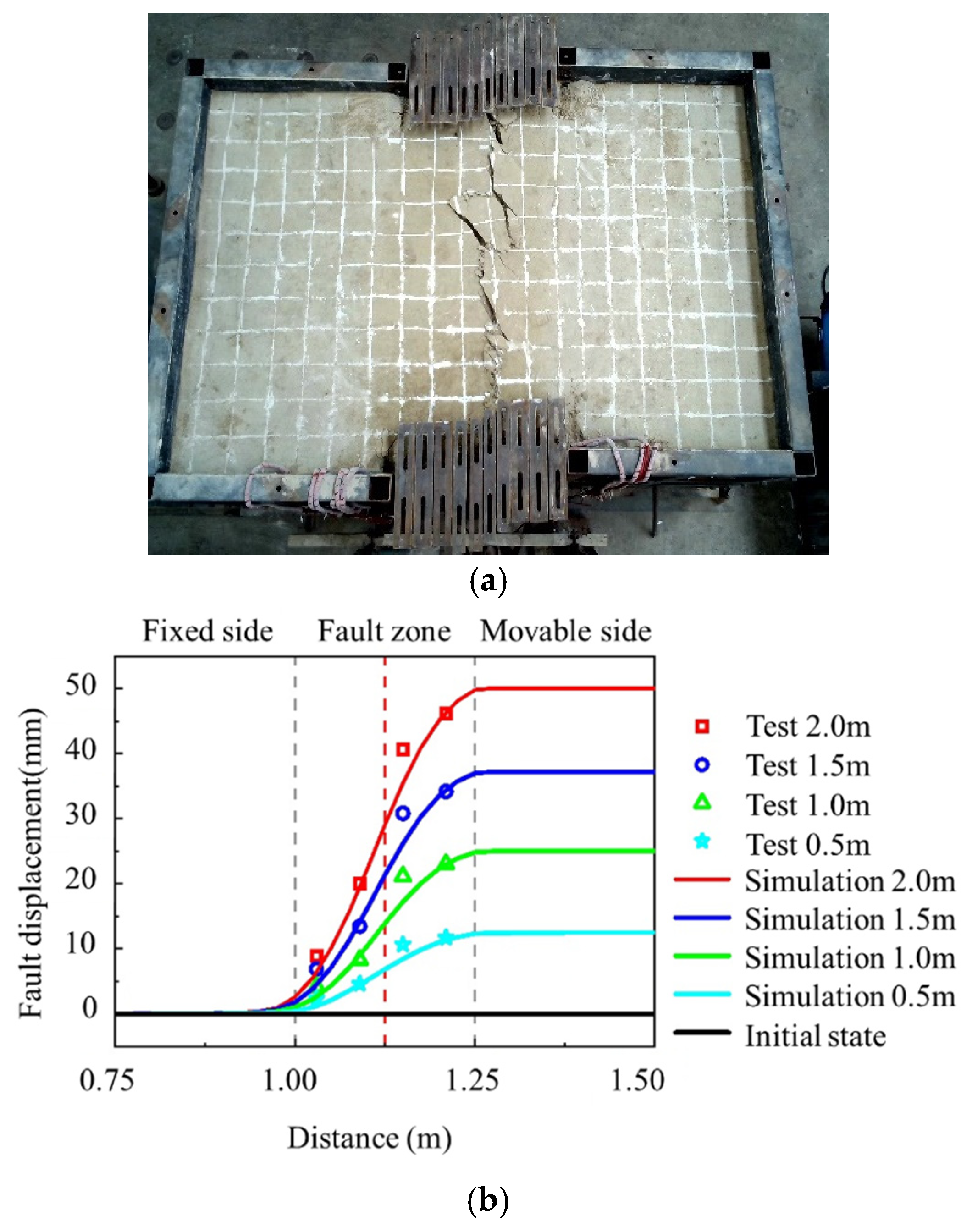

4.1. Considerations on Deformation Mode of Active Fault Zone

4.2. Numerical Modeling

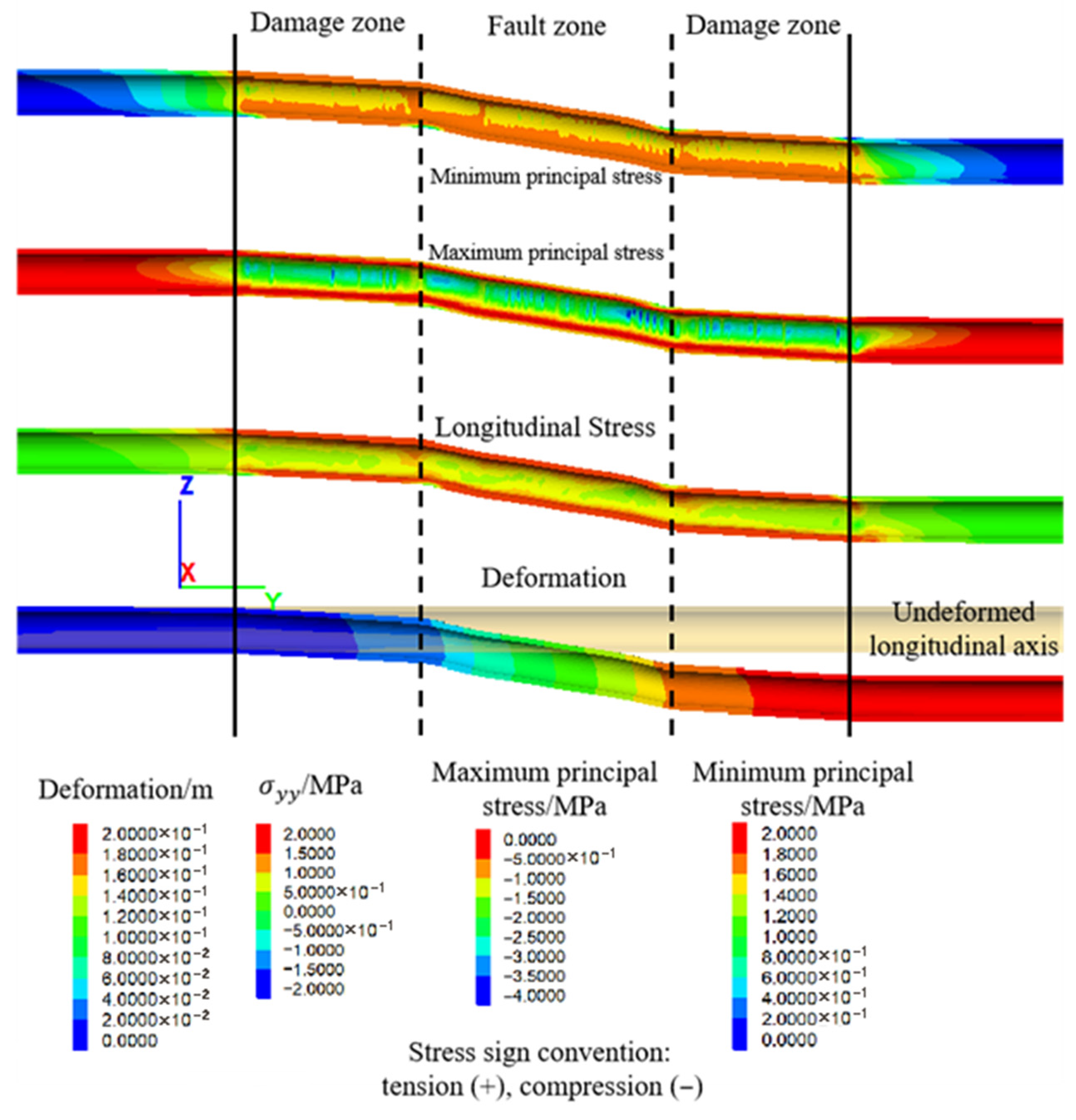

4.3. Response Characteristics of the Tunnel

- Deformation

- 2.

- Longitudinal stress

- 3.

- Service state of lining

- Damage-compression refers to the condition where the compressive stress in the element has exceeded the material’s peak compressive strength, and the strength evolution transitions from the strengthening phase to the weakening phase. The slight damage strain for C30 concrete can be set at 1500 × 10−6 [25].

- Failure-compression refers to the condition where an element in the compression-shear state experiences a compressive strain that exceeds the ultimate compressive strain of concrete. The ultimate compressive strain for C30 concrete can be set at 3.0 times the peak strain, which is equivalent to 4500 × 10−6 [25].

- Damage-tensile force occurs when the tensile strain of an element surpasses the material’s peak tensile strain. The peak tensile strain for C30 concrete can be taken as 10 × 10−6 [25].

- Failure-tensile force occurs when the tensile strain of an element exceeds the material’s ultimate tensile strain. The ultimate tensile strain for concrete can be set as 4~10 times the peak tensile strain. Therefore, the ultimate tensile strain for C30 concrete is 40 × 10−6 [26].

- Basically intact conditions refer to those where the compressive and tensile strains in the element do not reach the aforementioned threshold values.

5. Consideration of the Adaptive Measure Design

5.1. Conceptual Design

5.2. Estimation of Tunnel Hinged Design Parameters

- (1)

- Estimation method

- (2)

- Estimation results

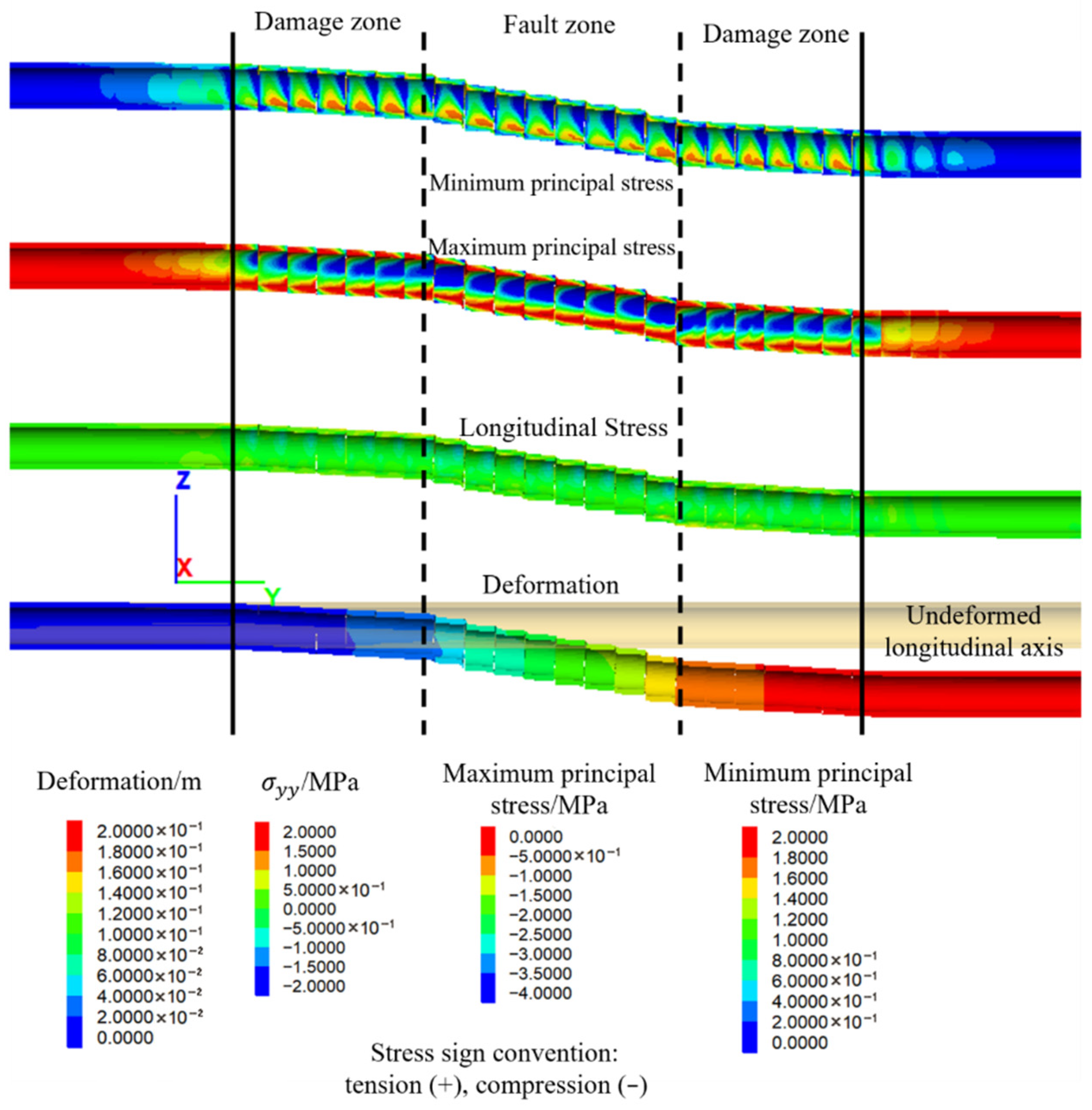

6. Lining Response Characteristics at the Proposed Hinged Design

- (1)

- Deformation

- (2)

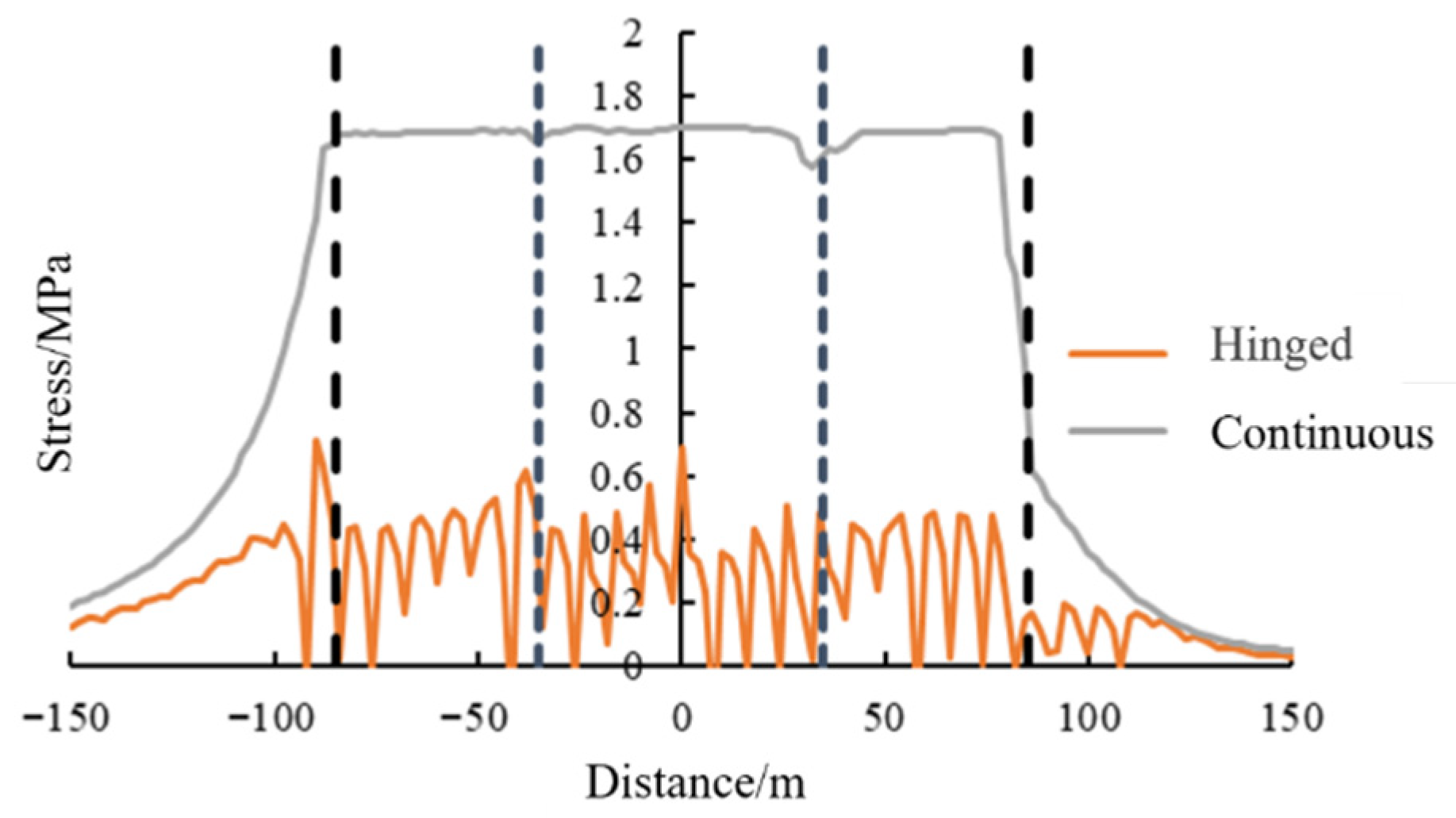

- Longitudinal stress

- (3)

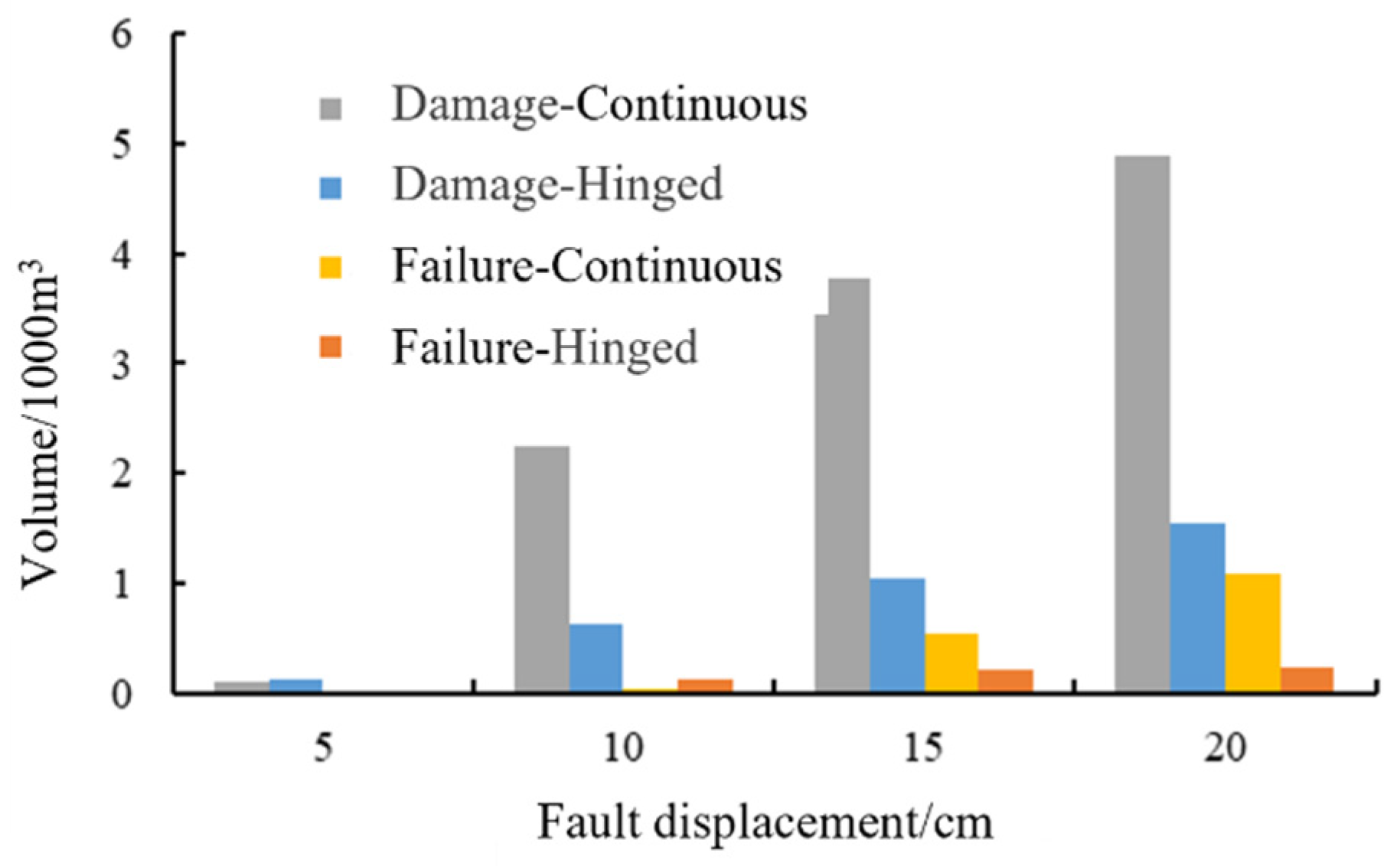

- Service state of lining

7. Conclusions

- (1)

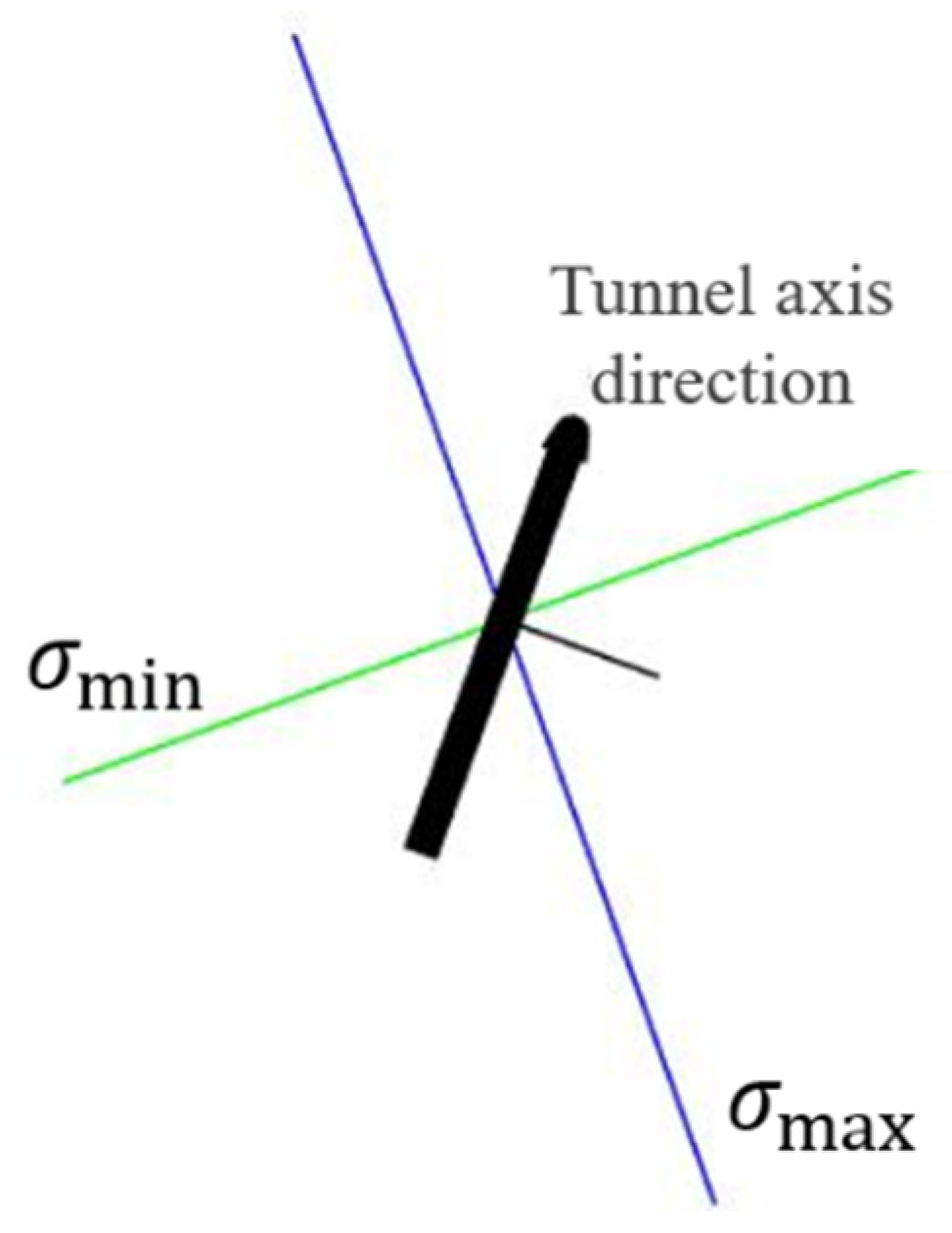

- For the section where the tunnel crosses Tongcheng River Fault, the azimuth angle of the maximum principal stress is approximately 340°. The maximum horizontal principal stress is around 23 MPa, the minimum horizontal principal stress is about 18 MPa, and the vertical stress is approximately 18 MPa. The angle between the horizontal maximum principal stress and the tunnel axis is 35°, and the horizontal stress component is about 20 MPa in the direction of the tunnel axis. The horizontal stress component is about 21 MPa in the direction of the vertical tunnel axis, and the vertical stress component is about 18 MPa.

- (2)

- A serviceability-based performance evaluation framework for tunnel lining is established, defining five distinct states: Damage-compression, Failure-compression, Damage-tensile, Failure-tensile, and Basically intact. By correlating numerical strain responses with explicit engineering safety criteria, this approach translates abstract mechanical behavior into actionable and interpretable indicators of structural condition.

- (3)

- In the absence of anti-dislocation measures, the relative deformation of the tunnel under the action of a normal fault is primarily characterized by the convergence between the crown and the invert, with the greatest degree of convergence occurring within the fault zone. The maximum principal stress in the crown and invert is concentrated in the fault zone and its adjacent affected zone, where the stress is significantly elevated. Under dislocation conditions, most of the lining in the fault zone and the affected zone is in a damaged state. Extensive damage zones appear in the sidewalls and crown of the lining within the fault zone, while the central sidewall in the affected zone also exhibits significant damage. Tensile failure of the lining mainly exhibited in the side wall is the dominant failure mode of lining.

- (4)

- A method for estimating hinged segment parameters based on the S-shaped fault dislocation mode is first proposed. This method recognizes that the required joint width is primarily controlled by the relative rotation between adjacent lining segments rather than axial extension, and it accounts for the strain capacity of the joint-filling material to prevent damage under expected deformation. Based on this approach, an initial design is established with a fortification segment length of 6 m and a hinge width of 2–4 cm. Parameter sensitivity analyses show that the required joint width is influenced by factors such as fault dislocation magnitude, segment length, and fault zone width. Considering these variations, the hinge width is ultimately recommended as 5 cm.

- (4)

- Following the implementation of the hinged structure with the proposed design parameters, the lining’s anti-dislocation performance is significantly enhanced. Under a fault dislocation of 20 cm, the hinged design reduces the volume of damaged lining elements by 79.09% and that of failed elements by 69.07%. It also lowers the maximum tensile stress at the tunnel crown by 58.82%, effectively mitigating stress concentration and substantially improving the overall stress state. The relative deformation, stress levels, and extent of lining damage within the fault zone are all markedly reduced, confirming the effectiveness of the hinged design in accommodating fault movement.

- (5)

- Future work will further optimize the fault-adaptive hinged lining design by investigating the effects of varying segment lengths, joint widths, hinge filling materials, and fortification ranges. It should be noted that this study focuses solely on the quasi-static response to tectonic fault dislocation and does not consider seismic dynamic loading. However, active fault zones may experience both long-term creep and sudden earthquake-induced slip, and their combined effects could significantly alter structural behavior. Therefore, we will investigate coupled seismic–tectonic loading scenarios to further validate the adaptability of hinged tunnel systems in seismically active regions.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Xu, X.; Guo, T.; Liu, S.; Yu, G.; Chen, G.; Wu, X. Discussion on Issues Associated with Setback Distance from Active Fault. Seismol. Geol. 2016, 38, 477–502. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Xue, Y.; Kong, F.; Yang, W.; Qiu, D.; Su, M.; Fu, K.; Ma, X. Main Unfavorable Geological Conditions and Engineering Geological Problems along Sichuan—Tibet Railway. Chin. J. Rock Mech. Eng. 2020, 39, 445–468. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, X.; Fu, P.; Yin, J.; Liu, Y. In-situ Stress Characteristics and Active Tectonic Response of Xianglushan Tunnel of Middle Yunnan Water Diversion Project. Chin. J. Geotech. Eng. 2021, 43, 130–139. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Wang, W.; Ren, Q. General Introduction to the Effect of Active Fault on Deeply Buried Tunnel. Earthq. Eng. Eng. Vib. 2006, 26, 175–180. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Chen, P.; Geng, P.; Chen, J.; Gu, W. The seismic damage mechanism of Daliang tunnel by fault dislocation during the 2022 Menyuan Ms6.9 earthquake based on unidirectional velocity pulse input. Eng. Fail. Anal. 2023, 145, 107047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, Q.P.; Peng, J.M.; Ng, C.W.; Shi, J.W.; Chen, X.X. Centrifuge and numerical modelling of tunnel intersected by normal fault rupture in sand. Comput. Geotech. 2019, 111, 137–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghadimi, C.A.; Tahghighi, H. Numerical finite element analysis of underground tunnel crossing an active reverse fault: A case study on the Sabzkouh segmental tunnel. Geomech. Geoengin. 2019, 14, 155–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Huang, D. Centrifuge Test of Deformation Characteristics of Overburden Clay Subjected to Normal and Reverse Fault Rupture. Rock Soil Mech. 2017, 38, 189–194. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Baziar, M.H.; Nabizadeh, A.; Lee, C.J.; Hung, W.Y. Centrifuge modeling of interaction between reverse faulting and tunnel. Soil Dyn. Earthq. Eng. 2014, 65, 151–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, G.; Zhang, Y.; Ren, J.; Xiao, M. Seismic response analysis of tunnel through fault considering dynamic interaction between rock mass and fault. Energies 2021, 14, 6700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaheri, M.; Ranjbarnia, M.; Dias, D. 3D numerical investigation of segmental tunnels performance crossing a dip-slip fault. Geomech Eng 2020, 23, 351–364. [Google Scholar]

- Sabagh, M.; Ghalandarzadeh, A. Numerical modelings of continuous shallow tunnels subject to reverse faulting and its verification through a centrifuge. Comput. Geotech. 2020, 128, 103813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, Z.; Wang, Z.; Zhao, M.; Du, X. Structural damage assessment of mountain tunnels in fault fracture zone subjected to multiple strike-slip fault movement. Tunn. Undergr. Space Technol. 2020, 104, 103527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramesh, A.; Rashiddel, A.; Hajihassani, M.; Dias, D.; Kiani, M. Interaction of segmental tunnel linings and dip-slip Faults—Tabriz subway tunnels. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 7866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, Y.M.; Xin, C.L.; Shen, Y.S.; Huang, Z.M.; Gao, B. The seismic response mechanisms of segmental lining structures applied in fault-crossing mountain tunnel: The numerical investigation and experimental validation. Soil Dyn. Earthq. Eng. 2021, 151, 107001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Li, X.; Yang, Y.; Liu, Y.; Ma, M. Structural stress characteristics and joint deformation of shield tunnels crossing active faults. Appl. Sci. 2022, 12, 3229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, S.; Zeng, Y.; Fan, L.; Wang, G.; Xun, Z.; Chen, G. Numerical investigation on the dynamic response of fault-crossing tunnels under strike-slip fault creep-slip and subsequent seismic shaking. Buildings 2023, 13, 1163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Li, X.; Sang, Y.; Lin, L. Experimental study on normal fault rupture propagation in loose strata and its impact on mountain tunnels. Tunn. Undergr. Space Technol. 2015, 49, 417–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, T.; Geng, P.; Li, P.; Wang, Q.; Wang, L. Deformation and failure of overburden soil subjected to normal fault dislocation and its impact on tunnel. Eng. Fail. Anal. 2022, 142, 106747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asadi, S.; Javan, M.; Bohloli, B.; Mutabashiani, S. Experimental, Numerical and Analytical Investigation the Initiation and Propagation of Hydraulic Fracturing (Case Study: Sarvak Lime Stone). World Appl. Sci. J. 2013, 22, 637–646. [Google Scholar]

- Klee, G.; Bunger, A.; Meyer, G.; Rummel, F.; Shen, B. In Situ Stresses in Borehole Blanche-1/South Australia Derived from Breakouts, Core Discing and Hydraulic Fracturing to 2 km Depth. Rock Mech. Rock Eng. 2011, 44, 531–540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Zhang, Y.; Guo, Q.; Zhao, S. New integrated analysis method to analyze stress regime of engineering area. Chin. J. Geotech. Eng. 2011, 33, 1562–1568. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, G. Investigating the Mechanism of Fault Failure and Faulting Resistance Measures for a Water Conveyance Tunnel Subjected to Active Faults. Ph.D. Thesis, University of the Chinese Academy of Sciences, Beijing, China, 2022. (In Chinese). [Google Scholar]

- GB/T 50218–2014; Standard for Engineering Classification of Rock Mass. Ministry of Housing and Urban-Rural Development of the People’s Republic of China: Beijing, China, 2014.

- GB 50010-2010; Code for Design of Concrete Structures. Ministry of Housing and Urban-Rural Development of the People’s Republic of China: Beijing, China, 2010.

- DL/T 5057-2009; Design Specification for Hydraulic Concrete Structures. National Energy Administration of the People’s Republic of China: Beijing, China, 2009.

| Chainage | Overburden Depth (m) | Tunnel Axis Azimuth (°) | Maximum Principal Stress Azimuth (°) | Angle Between Maximum Principal Stress and Tunnel Axis (°) | Principal Stress Magnitude (MPa) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Maximum Horizontal Principal Stress | Minimum Horizontal Principal Stress | Vertical Stress | |||||

| K96 + 709~K96 + 778 | 1076.4~1129.2 | 15 | 340 | 35 | 22.77~23.89 | 17.39~18.25 | 17.93~18.81 |

| Stratum | Surrounding Rock Classification | Density (kg·m−3) | Uniaxial Compressive Strength (MPa) | Elastic Modulus (GPa) | Poisson’s Ratio | Tensile Strength (MPa) | Friction Angle (°) | Cohesion (MPa) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| S3s | III | 2.65 × 103 | 80 | 7 | 0.28 | 1.0 | 45 | 1.0 |

| S1ln | IV | 2.65 × 103 | 25 | 4 | 0.3 | 0.7 | 35 | 0.7 |

| Damage zone | IV2 | 2.5 × 103 | 10 | 1.2 | 0.33 | 0.5 | 30 | 0.5 |

| Fault zone | V | 2.4 × 103 | 8 | 1 | 0.35 | 0.3 | 24 | 0.3 |

| Elastic Modulus (GPa) | Poission’s Ratio | Density (kg/m3) | Peak/Residual Cohesion (MPa) | Peak/Residual Friction Angle (°) | Peak/Residual Tension Strength (MPa) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 30 | 0.2 | 2500 | 3.16/0.25 | 54.9/46 | 2.0/0 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Zhang, G.; Guan, G.; Cui, Z.; Yan, T.; Zhang, M.; Li, J. Deformation Mechanism and Adaptive Measure Design of a Large-Buried-Depth Water Diversion Tunnel Crossing an Active Fault Zone. Buildings 2026, 16, 4. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings16010004

Zhang G, Guan G, Cui Z, Yan T, Zhang M, Li J. Deformation Mechanism and Adaptive Measure Design of a Large-Buried-Depth Water Diversion Tunnel Crossing an Active Fault Zone. Buildings. 2026; 16(1):4. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings16010004

Chicago/Turabian StyleZhang, Guoqiang, Guoxing Guan, Zhen Cui, Tianyou Yan, Maochu Zhang, and Jianhe Li. 2026. "Deformation Mechanism and Adaptive Measure Design of a Large-Buried-Depth Water Diversion Tunnel Crossing an Active Fault Zone" Buildings 16, no. 1: 4. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings16010004

APA StyleZhang, G., Guan, G., Cui, Z., Yan, T., Zhang, M., & Li, J. (2026). Deformation Mechanism and Adaptive Measure Design of a Large-Buried-Depth Water Diversion Tunnel Crossing an Active Fault Zone. Buildings, 16(1), 4. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings16010004