Performance of Cementitious Materials Subjected to Low CO2 Concentration Accelerated Carbonation Curing and Further Hydration

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Raw Materials and Specimens

2.1.1. Raw Materials

2.1.2. Preparation of Experimental Specimens

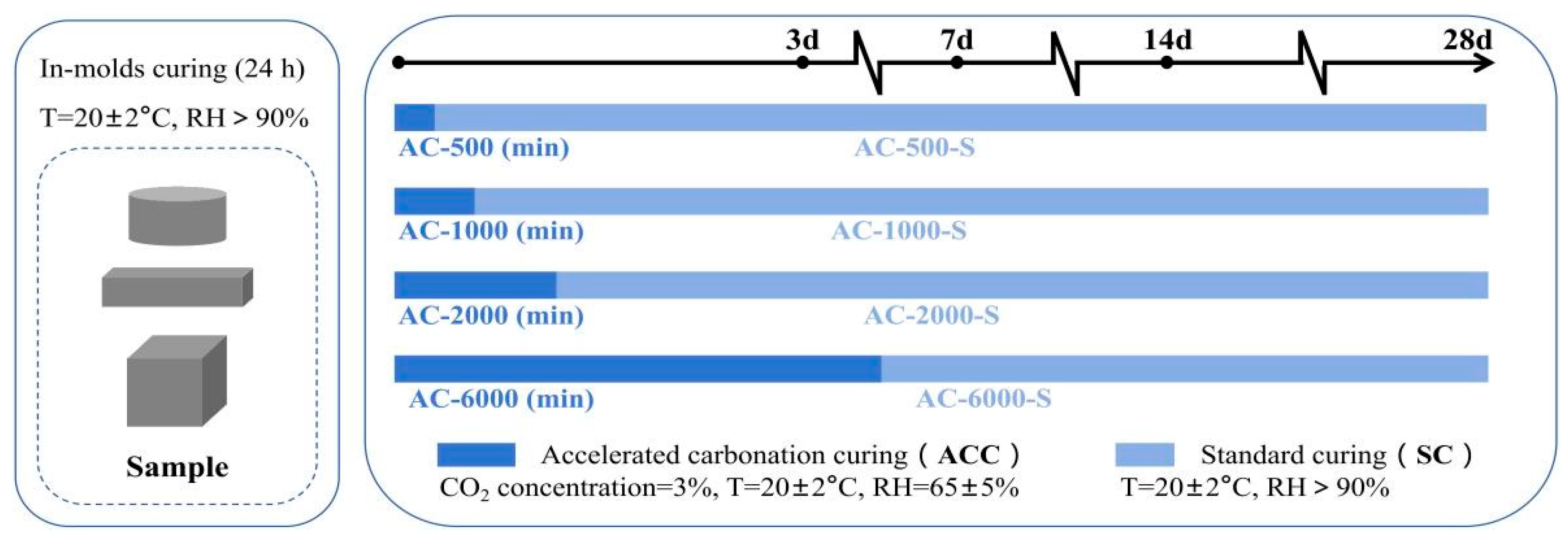

2.1.3. Specimen Curing Regime

- Accelerated carbonation curing (ACC)

- 2.

- Standard curing after accelerated carbonation curing (ACC−SC)

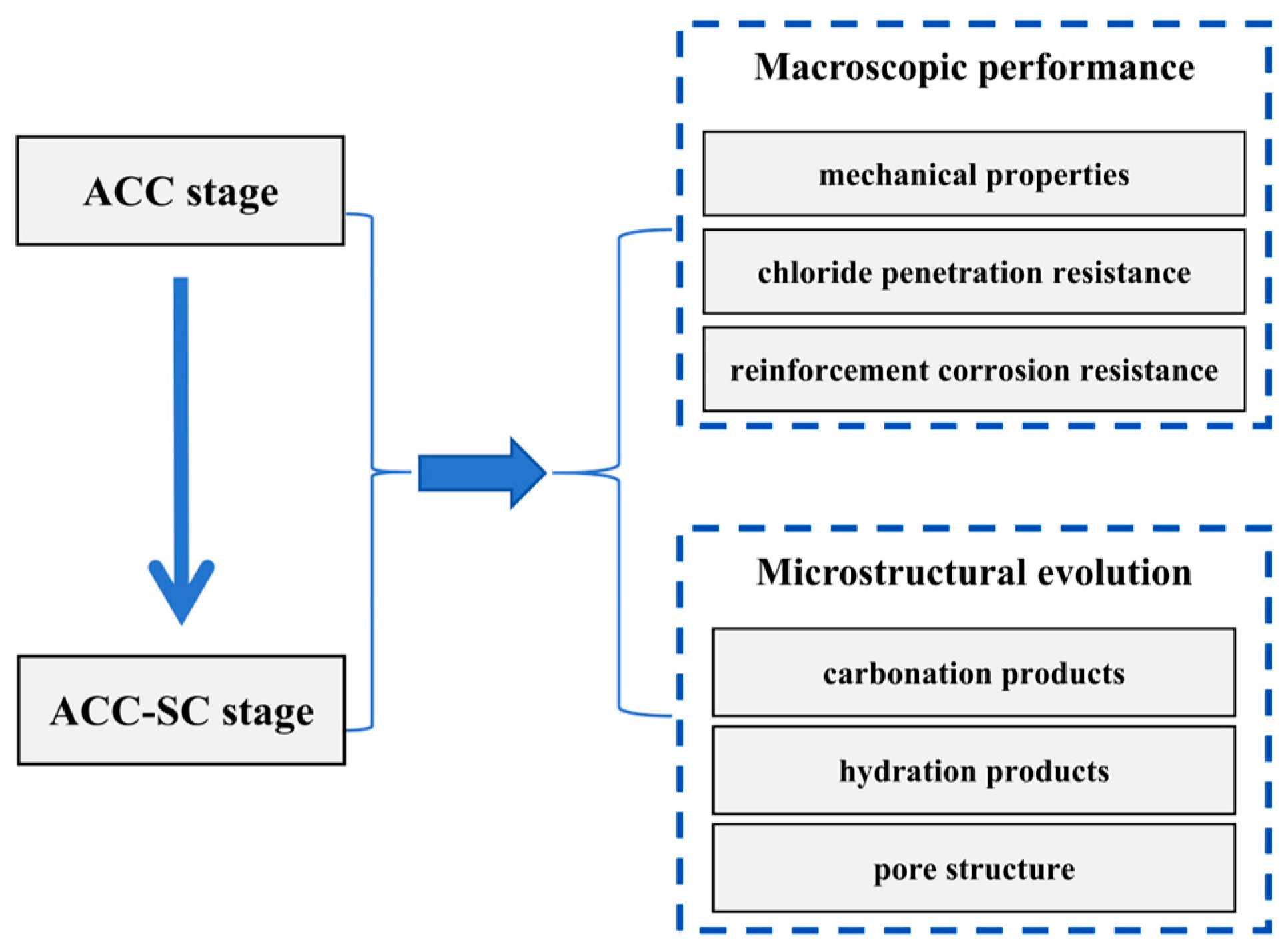

2.2. Test Methods

2.2.1. Mechanical Properties

2.2.2. Chloride Ion Penetration Resistance

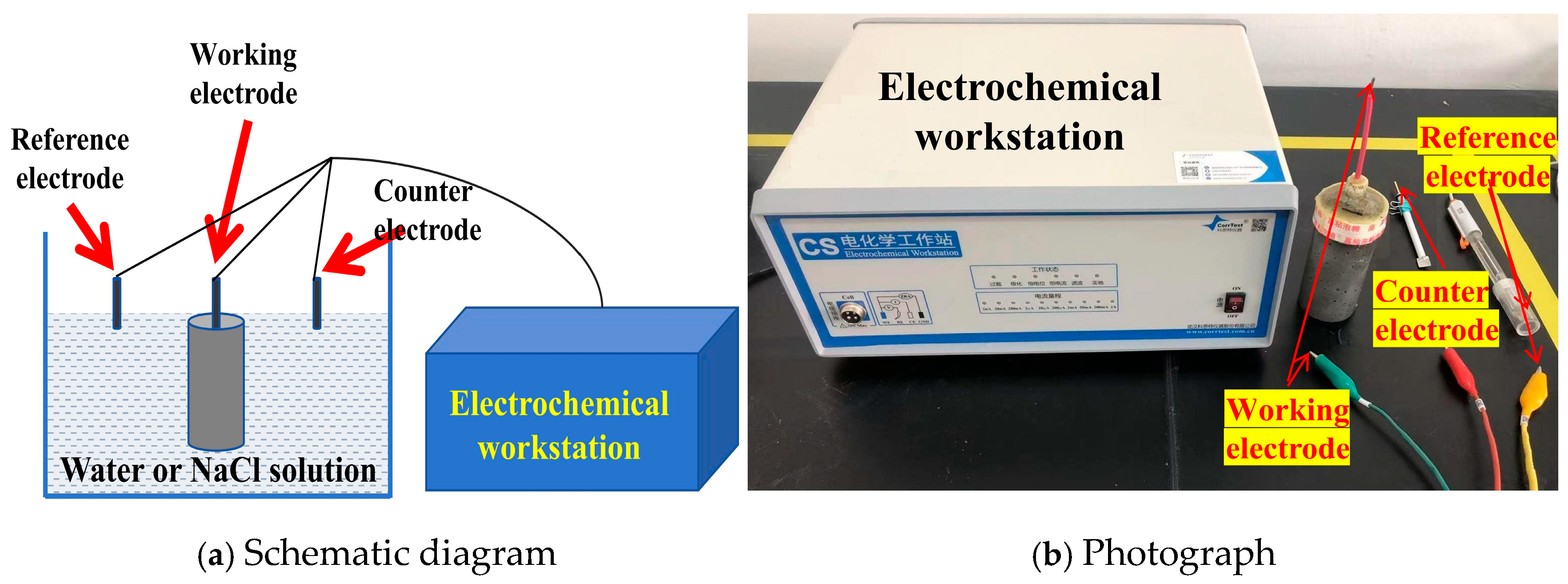

2.2.3. Corrosion Resistance of Embedded Steel Bars

- Preparation of reinforced cement mortar specimens

- 2.

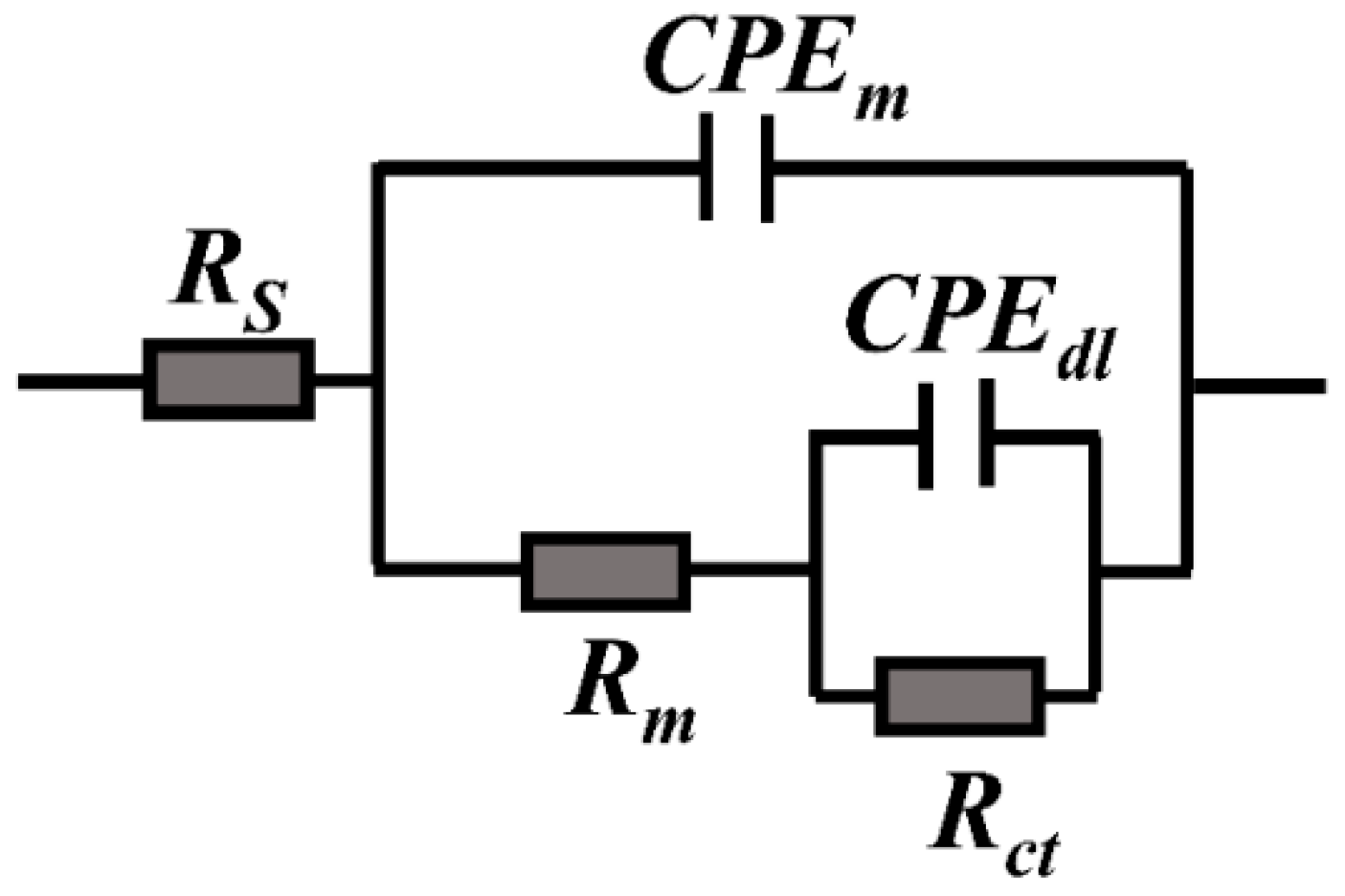

- Electrochemical impedance testing

2.2.4. Microstructural Experiments

3. Results and Analysis

3.1. Compressive and Flexural Strength

3.2. Results of the Electrical Flux

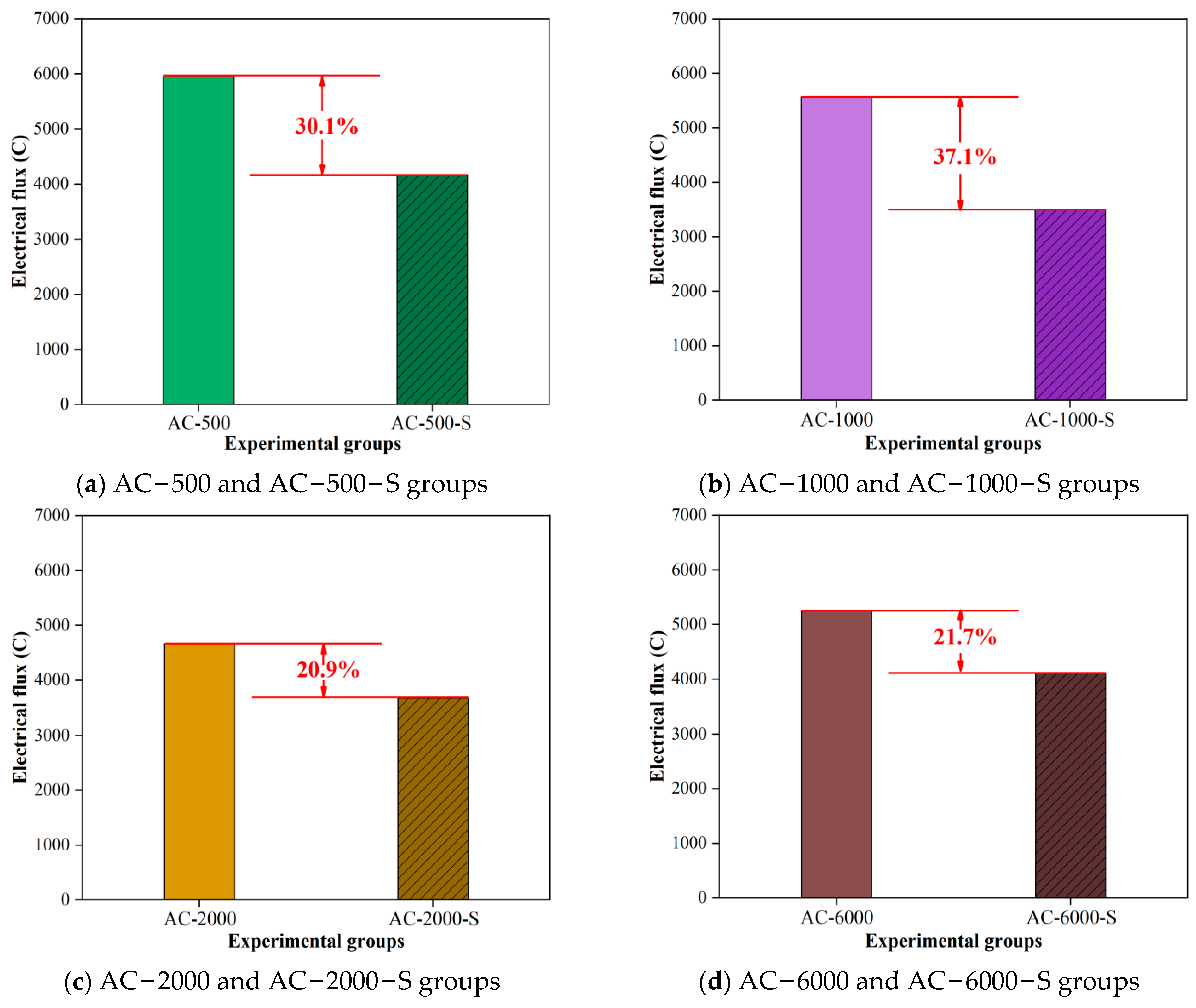

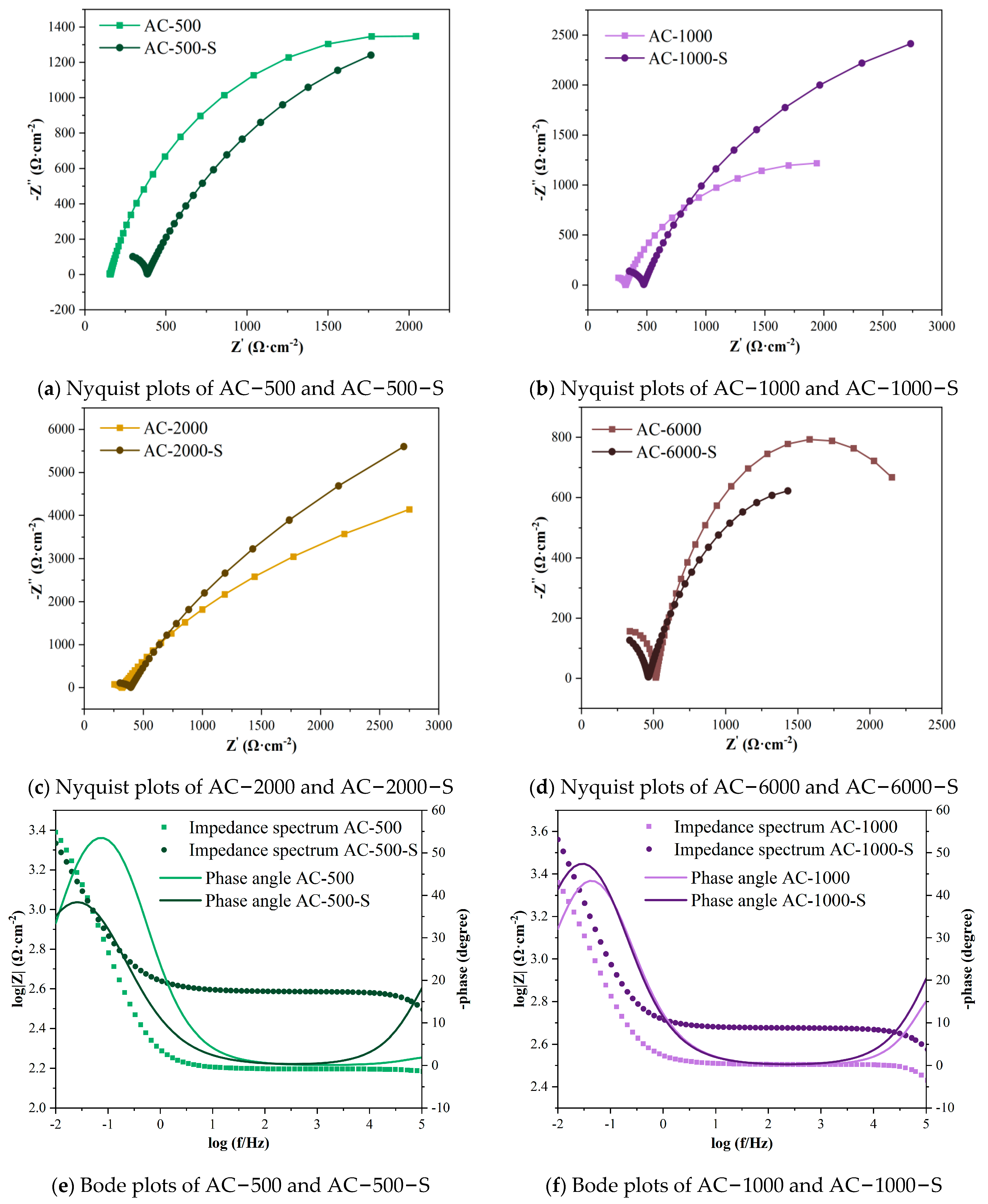

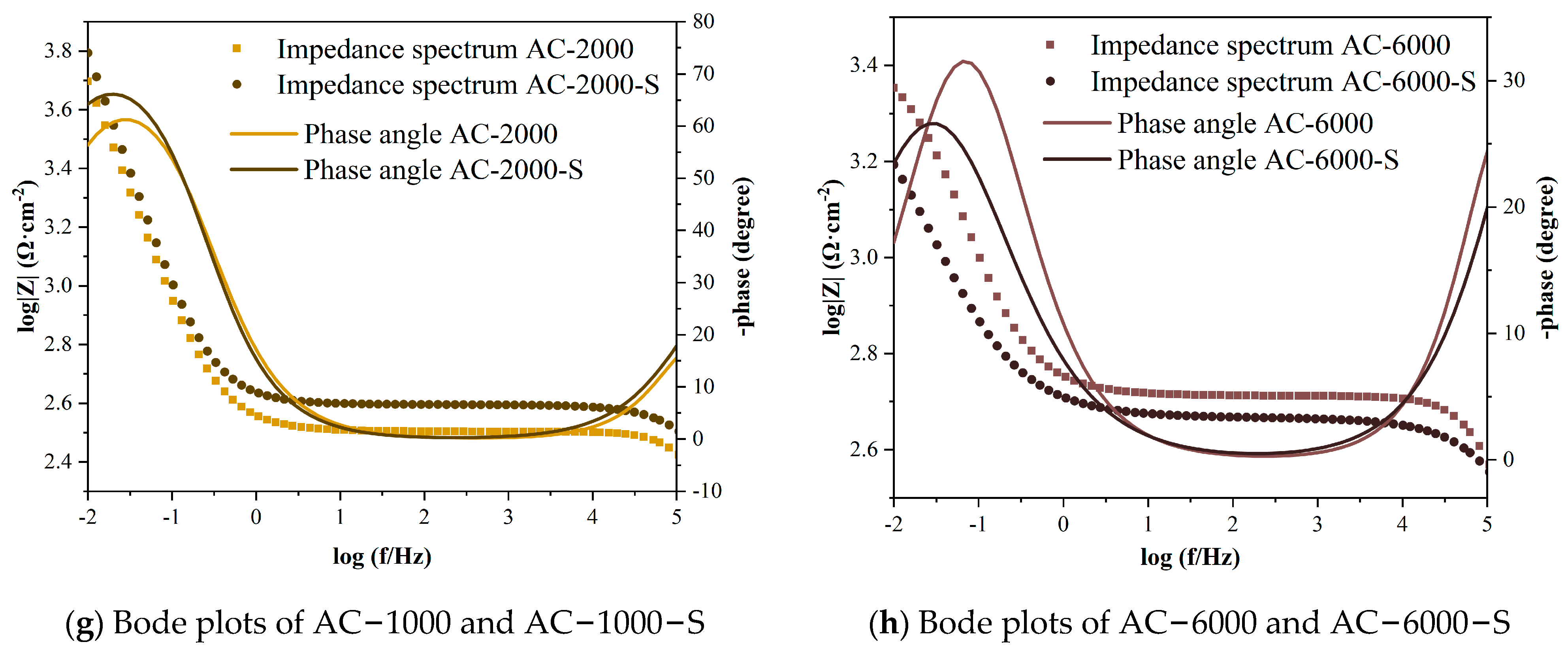

3.3. Results of Electrochemical Tests

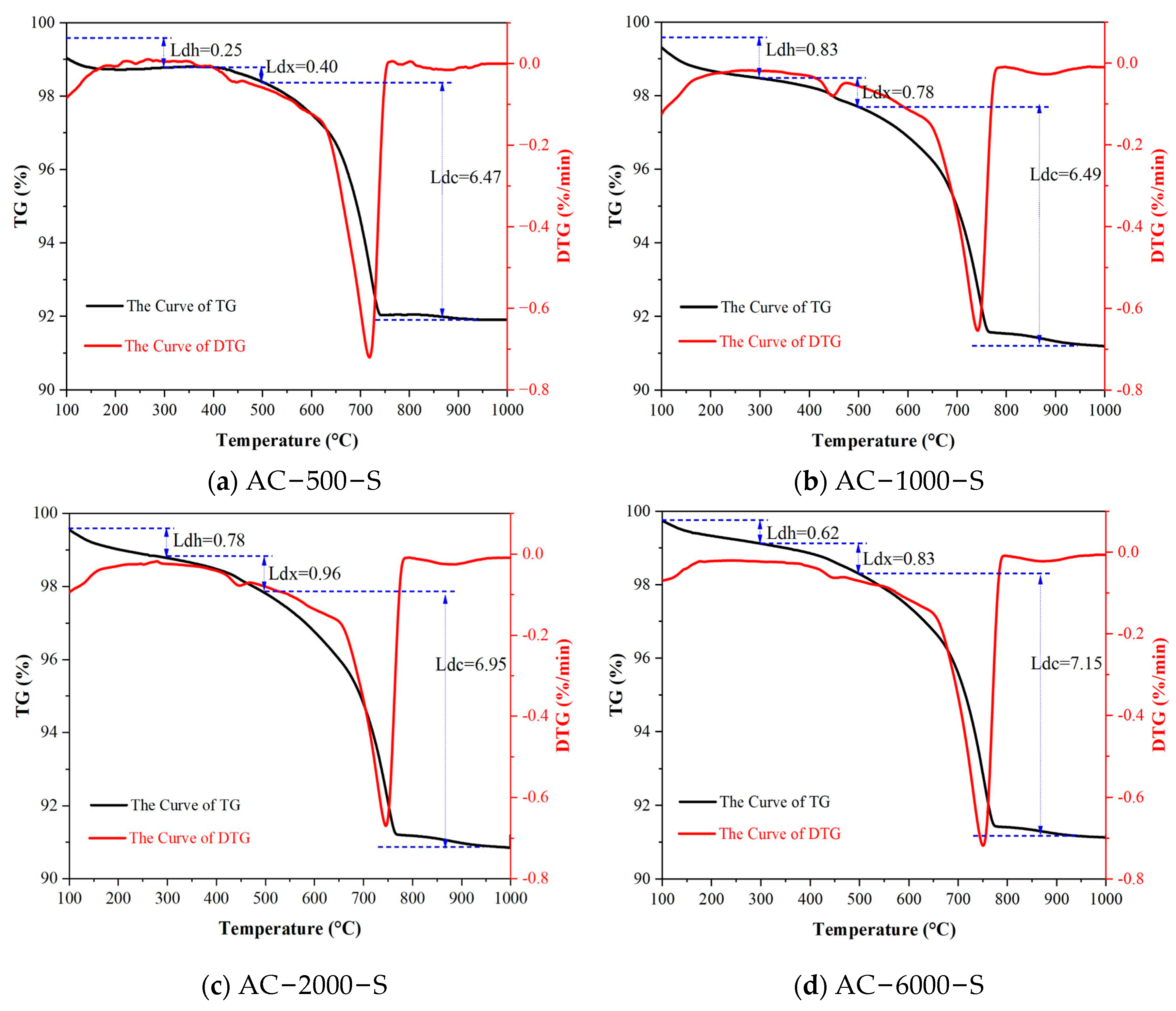

3.4. TGA

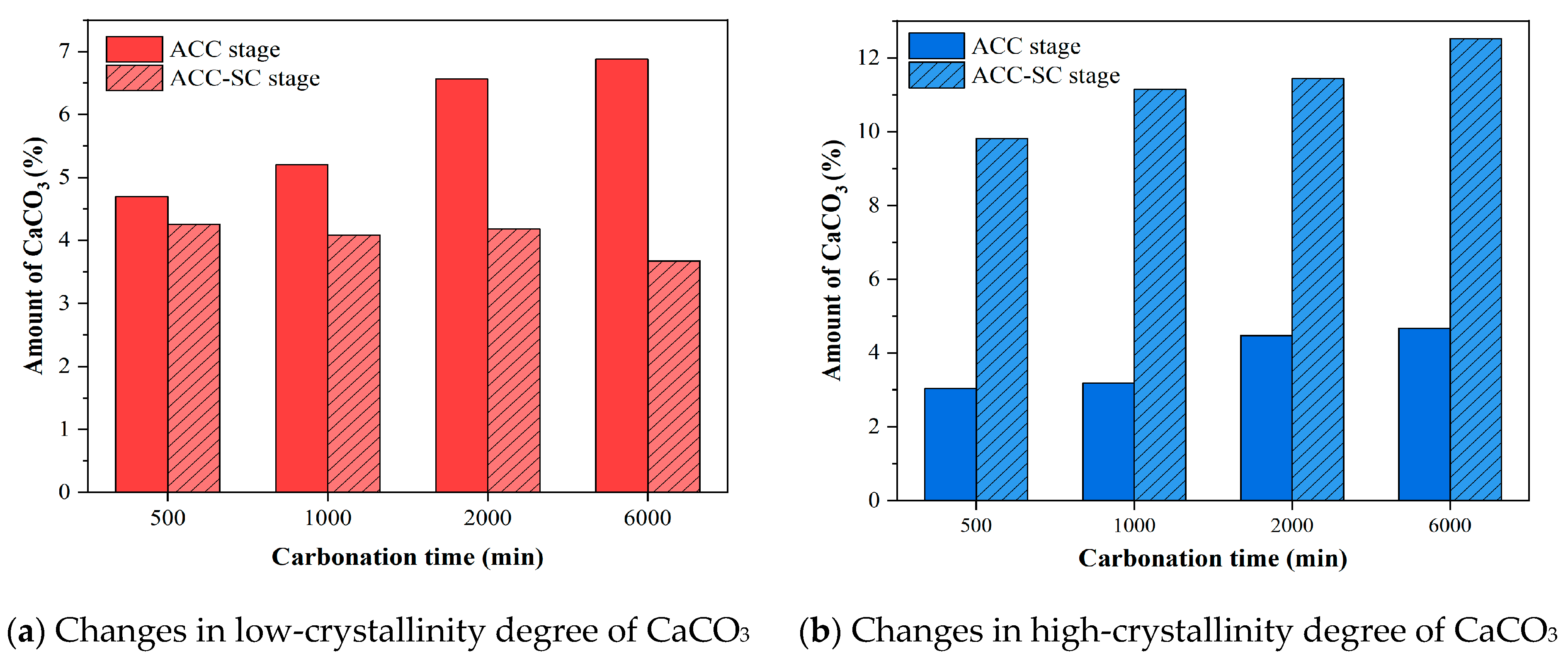

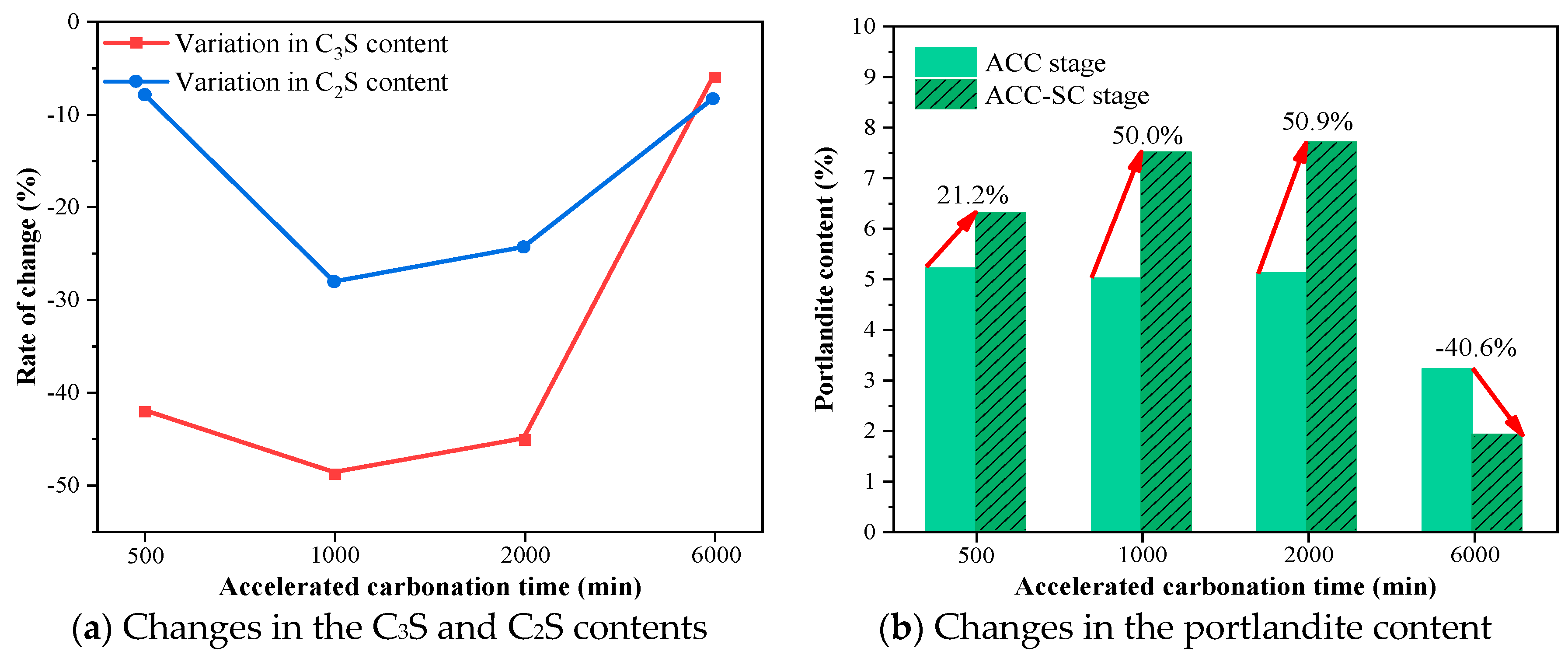

3.5. XRD

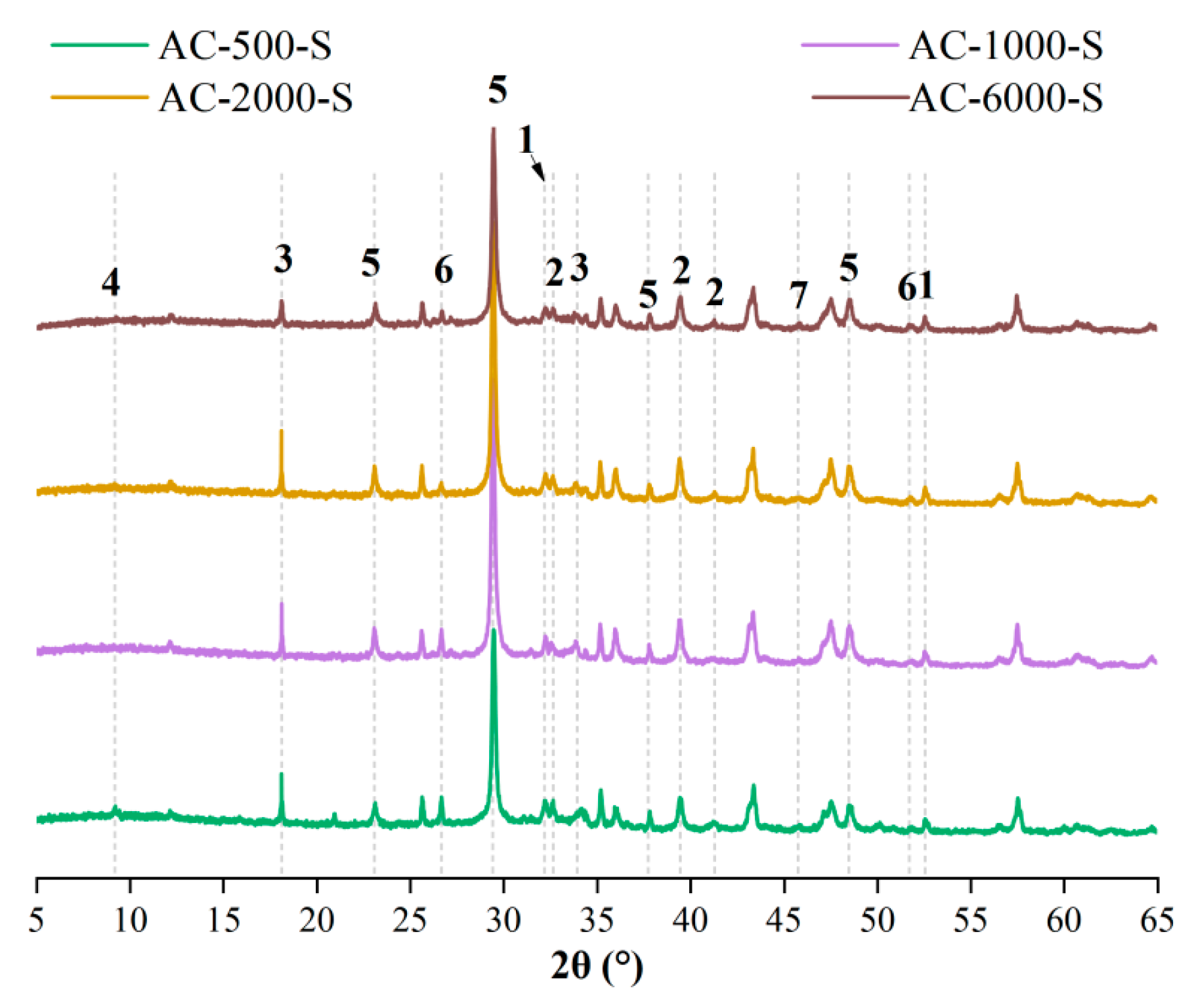

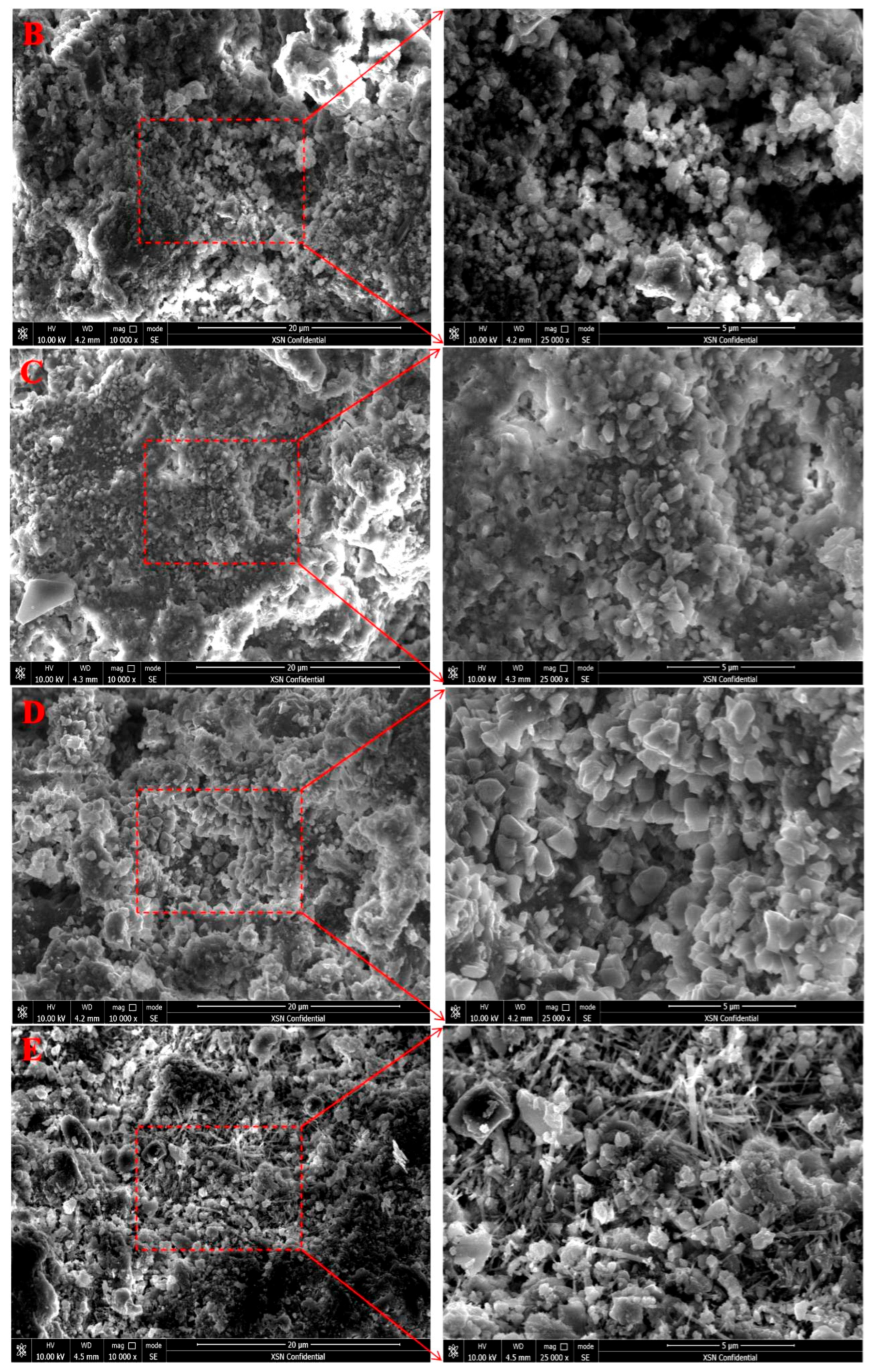

3.6. Microscopic Morphology Changes

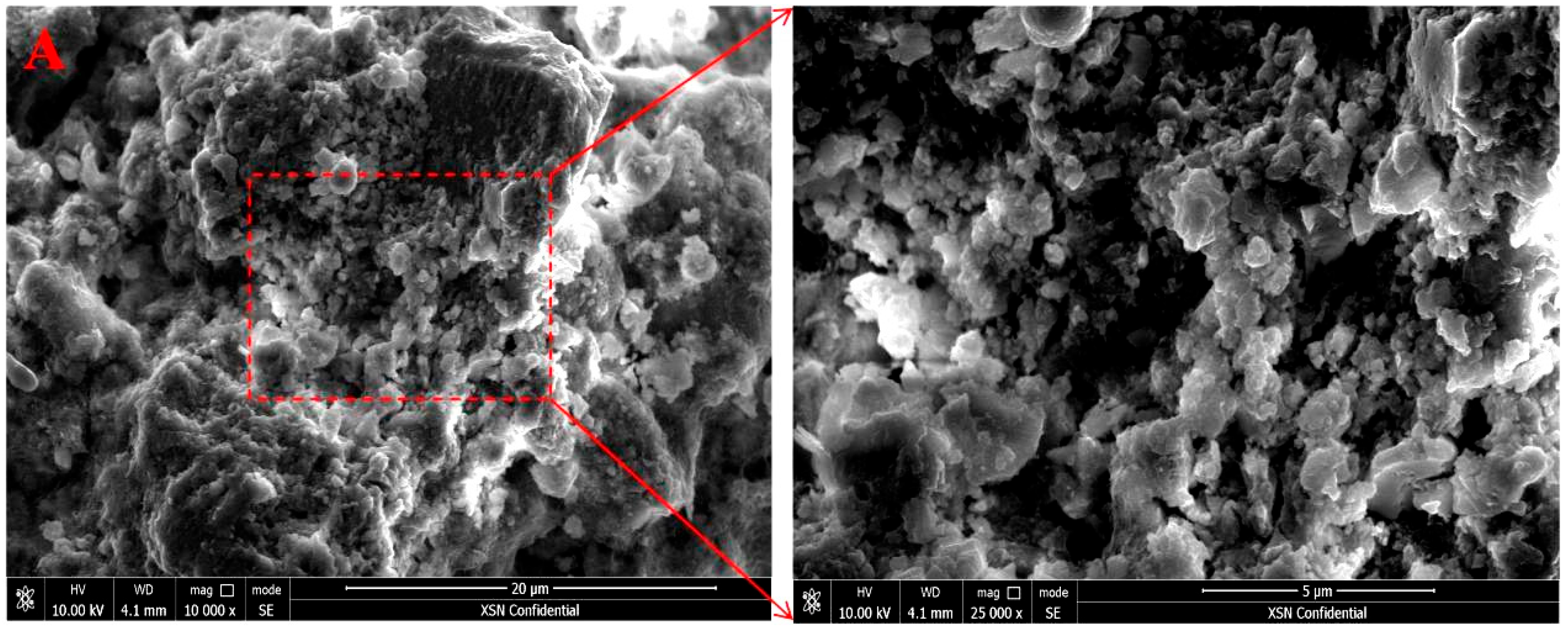

3.7. Pore Structure Changes

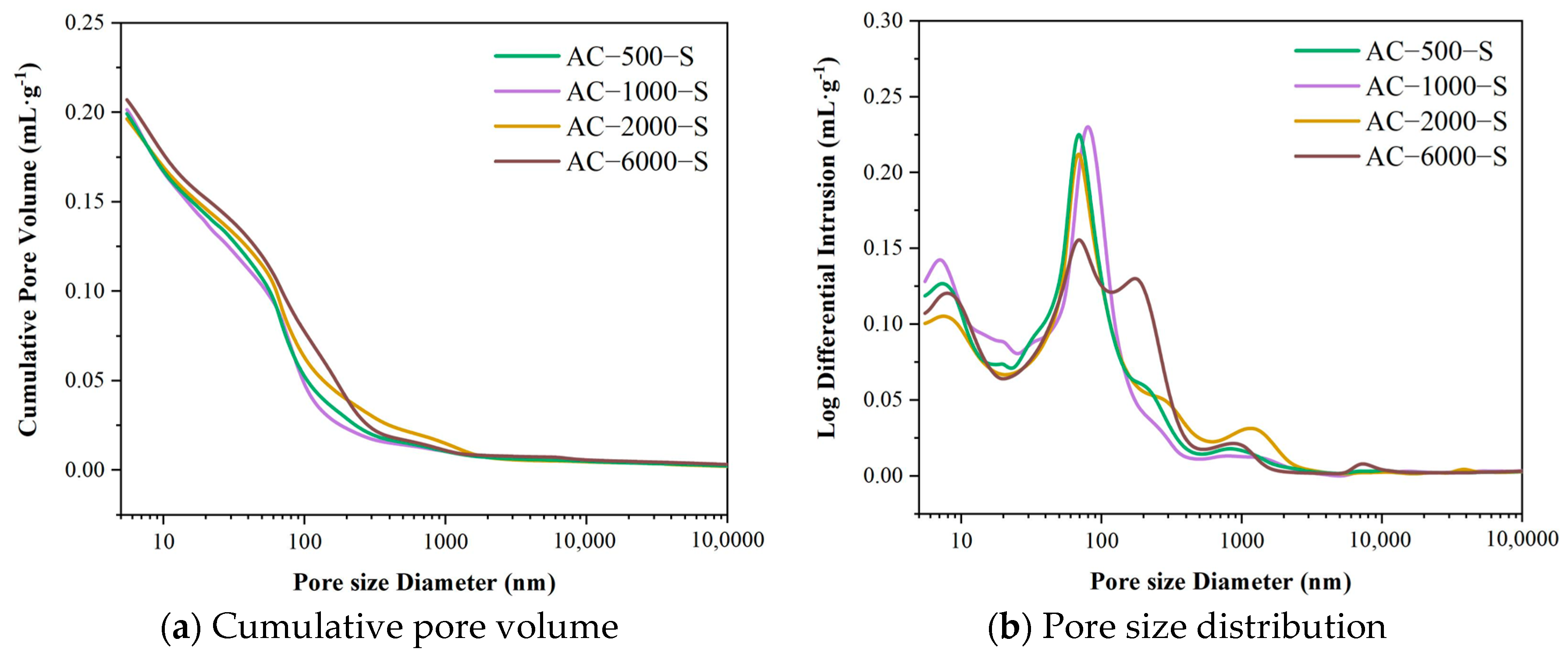

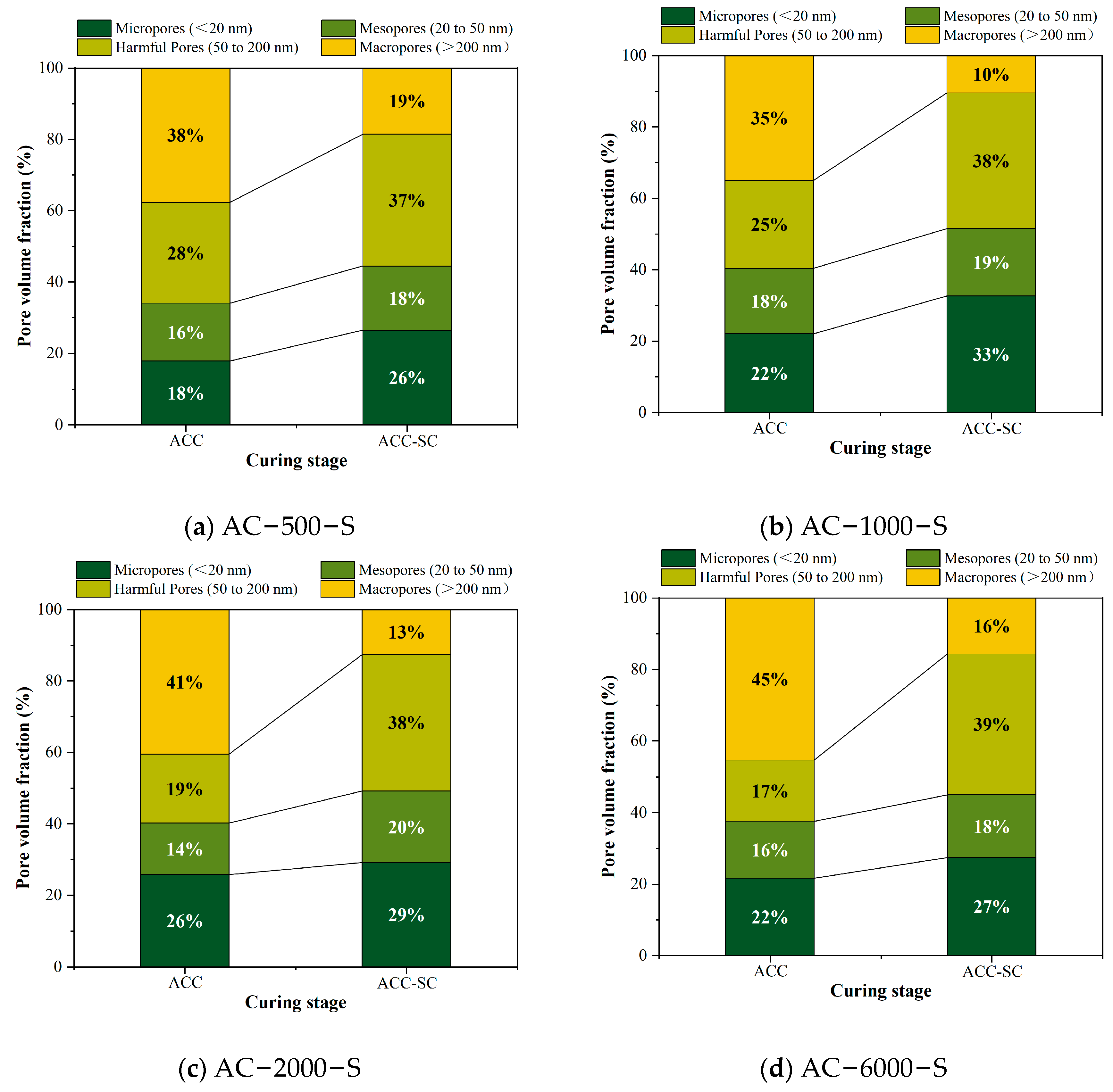

3.7.1. Pore Structure of Specimens in the ACC–SC Stage

3.7.2. Comparative Analysis of Pore Structures Between the ACC–SC and ACC Stages

3.8. Research Limitations

4. Application Scenarios

5. Conclusions and Recommendations

- (1)

- Under accelerated carbonation curing for 2000 min in 3% CO2, the early performance of the cement paste showed the most significant improvement, with compressive and flexural strengths increasing by 28.3% and 7.7% compared to the standard curing group. The electrical flux and electrochemical results also demonstrated the strongest resistance to chloride ion penetration and protective capacity for the reinforcement. As hydration continued, the group with the most notable performance enhancement occurred at an early carbonation curing time of 1000 min, with compressive and flexural strengths increasing by 16.6% and 12.9%. The electrical flux value decreased by over 40% compared to the ACC stage, and the impedances of the cement paste and reinforcement increased by 141.5% and 124.1%.

- (2)

- The TG results indicate that during the ACC−SC stage, the mass proportions of C-S-H and CH at a depth of 1 mm from the surface of the specimens first increased and then decreased with the extension of early carbonation time, with turning points for C-S-H and CH occurring at carbonation durations of 1000 min and 2000 min, respectively. Under subsequent standard curing conditions, sufficient moisture provided favorable conditions for the continued crystallization of CaCO3, resulting in a maximum increase of 250.7% in the content of high-crystallinity CaCO3 in the cement mortar subjected to carbonation curing.

- (3)

- The density of cement mortar cured with 3% CO2 carbonation does not exhibit a linear relationship with carbonation curing time. As the early carbonation curing time increases, the Ca/Si ratio at the surface of the further hydrated cement mortar gradually decreases, while the proportions of micropores and mesopores gradually increase until the carbonation curing time exceeds 1000 min. This process also confirms that the transition in the crystallinity of CaCO3 does not adversely affect the optimization of the microstructure of the specimens.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Guo, X.; Li, Y.; Shi, H.; She, A.; Guo, Y.; Su, Q.; Ren, B.; Liu, Z.; Tao, C. Carbon reduction in cement industry-An indigenized questionnaire on environmental impacts and key parameters of life cycle assessment (LCA) in China. J. Clean. Prod. 2023, 426, 139022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, S.A.; John, V.M.; Pacca, S.A.; Horvath, A. Carbon dioxide reduction potential in the global cement industry by 2050. Cem. Concr. Res. 2018, 114, 115–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, C.; Li, B.; Guo, M.-Z.; Hou, S.; Wang, S.; Gao, Y.; Wang, X. Effects of early-age carbonation curing on the properties of cement-based materials: A review. J. Build. Eng. 2024, 84, 108495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.; Seo, J.; Park, S.; Lee, H.K. Effect of accelerated carbonation curing on thermal evolution of hydrates in calcium sulfoaluminate cement. Constr. Build. Mater. 2024, 416, 135201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Zhang, Z.-Y.; Zheng, Y.; Zhang, X.; Wang, X.; Yin, X. Comparison of magnesium oxysulfate (MOS) cement and reactive magnesia cement (RMC) under different curing conditions: Physical properties, mechanisms, and environmental impacts. Constr. Build. Mater. 2023, 405, 133317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Van den Heede, P.; Zhang, C.; Shi, X.; Wang, L.; Li, J.; Yao, Y.; Lothenbach, B.; De Belie, N. Carbonation of blast furnace slag concrete at different CO2 concentrations: Carbonation rate, phase assemblage, microstructure and thermodynamic modelling. Cem. Concr. Res. 2023, 169, 107161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Z.; Zhang, Z.; Huang, J.; Yu, K.; Zhong, G.; Chen, F.; Chen, X.; Yang, W.; Wang, Y. Effects of temperature, humidity and CO2 concentration on carbonation of cement-based materials: A review. Constr. Build. Mater. 2022, 346, 128399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drouet, E.; Poyet, S.; Le Bescop, P.; Torrenti, J.-M.; Bourbon, X. Carbonation of Hardened Cement Pastes: Influence of Temperature. Cem. Concr. Res. 2019, 115, 445–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, T.; Gao, X. Effect of Carbonation Curing Regime on Strength and Microstructure of Portland Cement Paste. J. CO2 Util. 2019, 34, 74–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Z.; Zhang, J.; Qin, L.; Chen, T.X.; Gao, X.J. Study on the Early Volume Stability of Cement-Based Materials During CO2 Curing. J. Build. Eng. 2024, 95, 110354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dixit, A.; Geng, G.; Du, H.; Pang, S.D. The Role of Age on Carbon Sequestration and Strength Development in Blended Cement Mixes. Cem. Concr. Compos. 2022, 133, 104644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, S.; Huang, G.; Zhang, W.; Sha, X.; Liu, G.; Lin, R.-S.; Chen, L. Enhancing Cement-Based Materials Hydration and Carbonation Efficiency with Pre-Carbonated Lime Mud. J. CO2 Util. 2024, 88, 102928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, D.; Cai, X.; Jaworska, B. Effect of Pre-Carbonation Hydration on Long-Term Hydration of Carbonation-Cured Cement-Based Materials. Constr. Build. Mater. 2020, 231, 117122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, M.; Hong, S.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, J.; Hou, D.; Dong, B. Compositions and Microstructures of Hardened Cement Paste with Carbonation Curing and Further Water Curing. Constr. Build. Mater. 2021, 267, 121724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhan, B.J.; Xuan, D.X.; Poon, C.S.; Shi, C.J. Mechanism for Rapid Hardening of Cement Pastes Under Coupled CO2-Water Curing Regime. Cem. Concr. Compos. 2019, 97, 78–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, S.; Assaggaf, R.A.; Maslehuddin, M.; Al-Amoudi, O.S.B.; Adekunle, S.K.; Ali, S.I. Effects of Carbonation Pressure and Duration on Strength Evolution of Concrete Subjected to Accelerated Carbonation Curing. Constr. Build. Mater. 2017, 136, 565–573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bersisa, A.; Moon, K.-Y.; Kim, G.M.; Cho, J.-S.; Park, S. Microstructural Characterization of CO2-Cured Calcium Sulfoaluminate Cement. Dev. Built Environ. 2024, 19, 100518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leemann, A.; Winnefeld, F.; Münch, B.; Tiefenthaler, J. Accelerated Carbonation of Recycled Concrete Aggregates and Its Implications for the Production of Recycling Concrete. J. Build. Eng. 2023, 79, 107779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaddah, F.; Ranaivomanana, H.; Amiri, O.; Rozière, E. Accelerated Carbonation of Recycled Concrete Aggregates: Investigation on the Microstructure and Transport Properties at Cement Paste and Mortar Scales. J. CO2 Util. 2022, 57, 101885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, R.; Shangguan, F.; Cui, Z. Research on low-carbon development strategies in steel industry: Review and prospect. China Metall. 2025, 35, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, J. Quantitative Analysis of the Factors Influencing Carbon Emissions in the Cement Industry. Environ. Sci. Manag. 2025, 50, 52–55+88. [Google Scholar]

- Cheng, J. Reflections on Establishing Green and Eco-Friendly Ready-Mix Concrete Mixing Plant. Oper. Manag. 2022, 6, 174–175+179. [Google Scholar]

- Auroy, M.; Poyet, S.; Le Bescop, P.; Torrenti, J.-M.; Charpentier, T.; Moskura, M.; Bourbon, X. Comparison Between Natural and Accelerated Carbonation (3% CO2): Impact on Mineralogy, Microstructure, Water Retention and Cracking. Cem. Concr. Res. 2018, 109, 64–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Li, S.; Hu, M.; Geng, Y.; Meng, S.; Jin, L. Early age accelerated carbonation of cementitious materials surface in low CO2 concentration condition. Constr. Build. Mater. 2024, 445, 137975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GB/T 17671-2021; Test Method of Cement Mortar Strength (ISO Method). China Standard Press: Beijing, China, 2021.

- GB/T 50082-2009; Standard for Test Methods of Long-Term Performance and Durability of Ordinary Concrete. China Standard Press: Beijing, China, 2009.

- Pan, X.; Shi, C.; Hu, X.; Ou, Z. Effects of CO2 Surface Treatment on Strength and Permeability of One-Day-Aged Cement Mortar. Constr. Build. Mater. 2017, 154, 1087–1095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, S.; Suh, H.; Kim, G.; Liu, J.; Li, P.; Bae, S. Microstructural phase evolution and strength development of low-lime calcium silicate cement (CSC) paste incorporating ordinary Portland cement under an accelerated carbonation curing environment. Constr. Build. Mater. 2024, 411, 134248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, H.; Ju, Y.; Lyu, H.; Liu, T.; Han, D.; Li, Y. Compressive Strength Development and Microstructure Evolution of Mortars Prepared Using Reactivated Cementitious Materials During CO2 Curing. Dev. Built Environ. 2024, 18, 100397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Effects of Sufficient Carbonation on the Strength and Microstructure of CO2-Cured Concrete. J. Build. Eng. 2023, 76, 107311. [CrossRef]

- Wu, S.; Liu, Q.; Li, L.; Kang, W.; Tiong, M.; Huang, T. Quantitative Characterization of Recycled Cementitious Materials Before and After Carbonation Curing: Carbonation Kinetics, Phase Assemblage, and Microstructure. Constr. Build. Mater. 2024, 421, 135596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, B.; Li, G.; Zhang, J.; Liu, Y.; Xing, F.; Hong, S. Non-Destructive Tracing on Hydration Feature of Slag Blended Cement with Electrochemical Method. Constr. Build. Mater. 2017, 149, 467–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, Y.; Dong, S.; Zheng, D.; Wang, J.; Zhang, X.; Du, R.; Song, G.; Lin, C. Multifunctional Inhibition Based on Layered Double Hydroxides to Comprehensively Control Corrosion of Carbon Steel in Concrete. Corros. Sci. 2017, 126, 166–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balusamy, T.; Nishimura, T. In-situ monitoring of local corrosion process of scratched epoxy coated carbon steel in simulated pore solution containing varying percentage of chloride ions by localized electrochemical impedance spectroscopy. Electrochim. Acta 2016, 199, 305–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saremi, M.; Mahallati, E. A Study on Chloride-Induced Depassivation of Mild Steel in Simulated Concrete Pore Solution. Cem. Concr. Res. 2002, 32, 1915–1921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pane, I.; Hansen, W. Investigation of Blended Cement Hydration by Isothermal Calorimetry and Thermal Analysis. Cem. Concr. Res. 2005, 35, 1155–1164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Usama, M.; Gardezi, H.; Jalal, F.E.; Rehman, M.A.; Javed, N.; Janjua, S.; Iqbal, M. Optimization of Biochar and Fly Ash to Improve Mechanical Properties and CO2 Sequestration in Cement Mortar. Constr. Build. Mater. 2023, 392, 131956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, D.; Shi, C.; Farzadnia, N.; Jia, H.; Zeng, R.; Wu, Y.; Lao, L. A Quantitative Study on Physical and Chemical Effects of Limestone Powder on Properties of Cement Pastes. Constr. Build. Mater. 2019, 204, 58–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bentz, D.P.; Ferraris, C.F.; Jones, S.Z.; Lootens, D.; Zunino, F. Limestone and Silica Powder Replacements for Cement: Early-Age Performance. Cem. Concr. Compos. 2017, 78, 43–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, X.; Chen, Z.; Chen, P.; Wang, L.; Qian, P.; Wang, S.; Wang, J. Pre-Carbonation of Ca(OH)2 for Producing Properties-Optimized CaCO3 Through Controlling Magnetic Field and Its Influence on the Performance of Mortars. Constr. Build. Mater. 2025, 469, 140496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, J.-F.; Xia, Y.-N.; Ju, L.-Y.; Yang, H.; Wang, Z.-Q.; Jin, J.-Y.; Zou, Y.-C.; Liao, Y.-C. Physico-mechanical performance and micro–mechanism analysis on urban sludge modified with a low carbon binder. Acta Geotechnica 2025, 20, 5585–5601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, B.; He, P.; Liu, J.; Peng, Z.; Song, B.; Hu, X. Microstructure of Portland cement paste subjected to different CO2 concentrations and further water curing. J. CO2 Util. 2021, 53, 101714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kupwade-Patil, K.; Palkovic, S.D.; Bumajdad, A.; Soriano, C.; Büyüköztürk, O. Use of silica fume and natural volcanic ash as a replacement to Portland cement: Micro and pore structural investigation using NMR, XRD, FTIR and X-ray microtomography. Constr. Build. Mater. 2018, 158, 574–590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, F.; Yu, S.; Sun, W.; Xia, W.; Hou, D.; Wang, M. Mix proportion design based on particle compact packing theory and research on the resistance of metakaolin to chloride salt erosion in UHPC cementitious system. Constr. Build. Mater. 2024, 447, 137982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Y.; Li, W.; Jin, M.; Liu, J.; Zhang, J.; Huang, J.; Lu, C.; Zeng, H.; Wang, J.; Zhao, H.; et al. Influences of leaching on the composition, structure and morphology of calcium silicate hydrate (C-S-H) with different Ca/Si ratios. J. Build. Eng. 2022, 58, 105017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cuesta, A.; Santacruz, I.; De la Torre, A.G.; Dapiaggi, M.; Zea-Garcia, J.D.; Aranda, M.A.G. Local structure and Ca/Si ratio in C-S-H gels from hydration of blends of tricalcium silicate and silica fume. Cem. Concr. Res. 2021, 143, 106405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Han, Y.; Shi, T.; Lv, B.; Zhang, F.; Zhou, X. An innovative method for preparing nano steel slag powder and analysis of carbonation reaction mechanism toward enhanced CO2 sequestration. Mater. Lett. 2026, 403, 139411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Item | SiO2 | Fe2O3 | Al2O3 | CaO | MgO | Na2O | SO3 | K2O | Loss |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chemical Composition (%) | 22.33 | 3.45 | 4.68 | 65.67 | 1.55 | 0.41 | 1.50 | 0.18 | 0.23 |

| Specific Surface Area (m2·kg−1) | Water Consumption for Standard Consistency (%) | Setting Time (min) | Compressive Strength (MPa) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Initial Setting | Final Setting | 3 d | 28 d | ||

| 340 | 23.9 | 180 | 230 | 27.2 | 47.4 |

| Specimens | Water–Cement Ratio | Cement | Standard Sand | Water |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| cement mortar | 0.5 | 450 | 1350 | 225 |

| cement paste | 1200 | / | 600 |

| Set Concentration (%) | Critical Concentration (%) | Temperature (°C) | Humidity (%) | Gas Injection Flow Rate (SCCM) | Data Acquisition Time Interval (min) | Total Gas Injection Duration (d) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3.0 | 2.5 | 20 ± 2 | 65 ± 5 | 1000 | 1 | 7 |

| Carbonation Time (min) | C3S | C2S | Portlandite | Ettringite | Calcite | Vaterite |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 500 | 7.3 | 10.5 | 6.3 | 18.1 | 4.0 | 0.3 |

| 1000 | 6.3 | 9.2 | 7.5 | 25.3 | 4.5 | 0.2 |

| 2000 | 5.6 | 9.3 | 7.7 | 23.4 | 4.5 | 0.2 |

| 6000 | 6.3 | 9.9 | 1.9 | 22.3 | 3.3 | 0.0 |

| Group | Element Atomic (%) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ca | Si | Ca/Si | O | C | |

| AC−500−S | 37.26 | 4.64 | 8.0 | 52.65 | 4.49 |

| AC−1000−S | 29.34 | 10.52 | 2.8 | 51.52 | 6.87 |

| AC−2000−S | 28.66 | 8.13 | 3.5 | 52.46 | 9.03 |

| AC−6000−S | 25.54 | 7.31 | 3.5 | 51.03 | 13.82 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Jiang, J.; Chen, X.; Li, L.; Yan, W.; Zhang, M.; Gang, Z.; Ma, Q.; He, J.; Dai, X. Performance of Cementitious Materials Subjected to Low CO2 Concentration Accelerated Carbonation Curing and Further Hydration. Buildings 2026, 16, 187. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings16010187

Jiang J, Chen X, Li L, Yan W, Zhang M, Gang Z, Ma Q, He J, Dai X. Performance of Cementitious Materials Subjected to Low CO2 Concentration Accelerated Carbonation Curing and Further Hydration. Buildings. 2026; 16(1):187. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings16010187

Chicago/Turabian StyleJiang, Jingyi, Xu Chen, Lei Li, Wenlong Yan, Meng Zhang, Zheng Gang, Qiangqiang Ma, Jingran He, and Xiaodi Dai. 2026. "Performance of Cementitious Materials Subjected to Low CO2 Concentration Accelerated Carbonation Curing and Further Hydration" Buildings 16, no. 1: 187. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings16010187

APA StyleJiang, J., Chen, X., Li, L., Yan, W., Zhang, M., Gang, Z., Ma, Q., He, J., & Dai, X. (2026). Performance of Cementitious Materials Subjected to Low CO2 Concentration Accelerated Carbonation Curing and Further Hydration. Buildings, 16(1), 187. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings16010187