Benchmarking Automated Machine Learning for Building Energy Performance Prediction: A Comparative Study with SHAP-Based Interpretability

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. The Demands for Building Energy Management

1.2. Physical vs. Data-Driven Building Energy Performance Modeling

1.3. Automated Machine Learning and Its Potential for Building Energy Performance Estimation

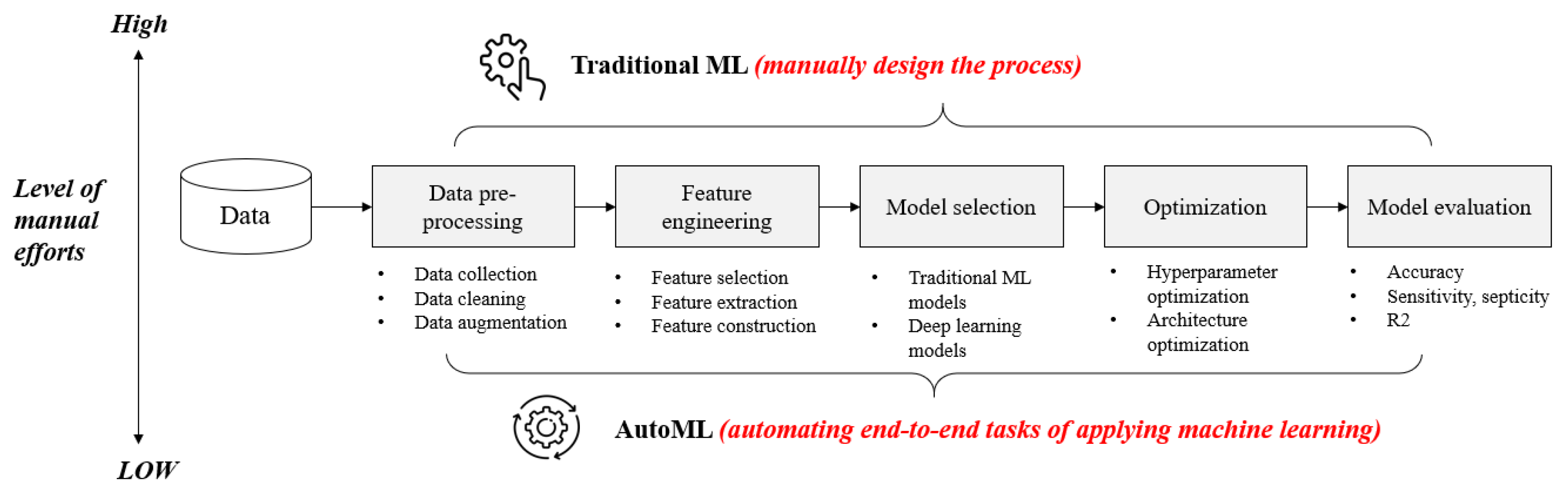

1.3.1. Traditional Machine Learning vs. Automated Machine Learning

1.3.2. AutoML for Building Energy Research

1.4. Research Gaps and Objectives

- 1.

- To conduct a review of AutoML applications in building energy research;

- 2.

- To benchmark AutoML performance for early-stage building energy prediction;

- 3.

- To enhance model transparency through Explainable Artificial Intelligence (XAI) techniques.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Review of AutoML for Building Energy Research

2.2. Benchmark Validation of AutoML for Building Energy Performance Prediction

2.2.1. Pre-Training Module

2.2.2. Traditional ML Module

2.2.3. AutoML Module

2.2.4. Model Evaluation Module

2.2.5. Results Presentation Module

2.3. AutoML with Interpretation to Support Transparent ML Decision-Making

2.4. Building Energy Consumption Dataset

3. Results

3.1. Results of Review for AutoML in Building Energy Research

3.1.1. Overview

3.1.2. Thematic Analysis

| Ref | Year | Application Area | Input | Output | AutoML Framework | Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [41] | 2025 | Energy consumption estimation | Total floor area, perimeter, Relh2, NPI, Vxcount, Builtrate, number habitable rooms, number heated rooms, lighting description | Energy consumption | Auto-sklearn | R2 score of 0.828 |

| [45] | 2025 | Cooling load estimation | Cooling water flow rate, chilled water flow rate, cooling water supply temperature, cooling water return temperature, chilled water return temperature, chilled water supply temperature | Cooling power | Auto-Gluon | MAP is 16.2% when compared to the predicted and the real. |

| [48] | 2024 | Energy consumption estimation, thermal comfort estimation | Window type, type of external wall insulation material, thickness of external wall insulation material, type of roof insulation material, thickness of roof insulation material, type of ground insulation material, thickness of ground insulation material. | Energy consumption, life cycle cost, thermal comfort hours | H2O | Accuracy reaches 97.43% and 96.44% for energy consumption prediction and thermal comfort time, respectively. |

| [46] | 2024 | Cooling load | Outdoor air temperature, humidity, rainfall, UV index | Cooling load | Auto-Gluon | The proposed method can achieve a coefficient of variation of less than 10% for long-term predictions on the test dataset. |

| [49] | 2024 | End-use intensity, thermal comfort hours ratio optimization | Location (External wall, lounge, office, consultation room & treatment room), phase change material (PCM) thickness. | End-use intensity, thermal comfort hours ratio | H2O | Optimized thermal comfort when using PCM. |

| [47] | 2024 | Cooling load estimation | Time variables, historical cooling load | Cooling load | Auto-Gluon, FLAML, TPOT, H2O | The proposed approach can improve the existing AutoML accuracy between 4.24% and 8.79%. |

| [21] | 2023 | Energy demand estimation | Yearly energy consumption data, building data (size, category), and weather data | Energy demand prediction | Auto-Gluon | AutoML-based methods achieve lower errors when predicting energy demand after the implementation of energy efficiency measures. |

| [12] | 2023 | Heating, cooling, and electrical load estimation | Cooling load, outdoor temperature, and outdoor air relative humidity. | Heating, cooling, and electrical loads | AutoWeka, H2O, TPOT, AutoGluon, FLAML, and AutoKeras | AutoML improved overall accuracy by 1.10% to 18.66%. |

| [13] | 2023 | Heating and cooling load | Relative compactness, surface area, wall area, roof area, overall height, orientation, glazing area percentage, glazing area distribution | heating load, cooling load | H2O, TPOT | R2 of 0.9965 and RMSE of 0.602 kWh/m2 for heating load prediction, and R2 of 0.9899 and RMSE of 0.973 kWh/m2 for cooling load prediction. |

3.2. Benchmark the Feasibility of AutoML to Estimate Building Energy Performance: A Case Study

3.2.1. Data Exploration

3.2.2. AutoML Performance

3.2.3. Comparison of Model Predictions

3.3. Explanation of the Prediction Based on AutoML-SHAP

3.3.1. Comparative Analysis of AutoML-SHAP and Feature Importance Analysis

3.3.2. Dependency Plot for the Best-Performed Automl Model

4. Discussion

4.1. Current Findings

4.2. Research Implications

4.3. Limitations and Future Directions

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Pérez-Lombard, L.; Ortiz, J.; Pout, C. A review on buildings energy consumption information. Energy Build. 2008, 40, 394–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santamouris, M.; Vasilakopoulou, K. Present and future energy consumption of buildings: Challenges and opportunities towards decarbonisation. e-Prime-Adv. Electr. Eng. Electron. Energy 2021, 1, 100002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, Y.; Zhang, L. Data-driven estimation of building energy consumption with multi-source heterogeneous data. Appl. Energy 2020, 268, 114965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EIA. Global Energy Consumption Driven by More Electricity in Residential, Commercial Buildings; Energy Information Administration: Washington, DC, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Piracha, A.; Chaudhary, M.T. Urban Air Pollution, Urban Heat Island and Human Health: A Review of the Literature. Sustainability 2022, 14, 9234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dalla Mora, T.; Peron, F.; Romagnoni, P.; Almeida, M.; Ferreira, M. Tools and procedures to support decision making for cost-effective energy and carbon emissions optimization in building renovation. Energy Build. 2018, 167, 200–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dubin, F.S. Energy-efficient building design: Innovative HVAC, lighting, energy-management control, and fenestration. Appl. Energy 1990, 36, 11–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simpeh, E.K.; Pillay, J.-P.G.; Ndihokubwayo, R.; Nalumu, D.J. Improving energy efficiency of HVAC systems in buildings: A review of best practices. Int. J. Build. Pathol. Adapt. 2022, 40, 165–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Guo, M.; Chen, Z.; Chen, Z.; Ji, Y. Physical energy and data-driven models in building energy prediction: A review. Energy Rep. 2022, 8, 2656–2671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oh, K.; Kim, E.-J.; Park, C.-Y. A Physical Model-Based Data-Driven Approach to Overcome Data Scarcity and Predict Building Energy Consumption. Sustainability 2022, 14, 9464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mugnini, A.; Coccia, G.; Polonara, F.; Arteconi, A. Performance Assessment of Data-Driven and Physical-Based Models to Predict Building Energy Demand in Model Predictive Controls. Energies 2020, 13, 3125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Tian, X.; Zhao, Y.; Lu, J. Automated machine learning-based building energy load prediction method. J. Build. Eng. 2023, 80, 108071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, C.; Li, S.; Reddy Penaka, S.; Olofsson, T. Automated machine learning-based framework of heating and cooling load prediction for quick residential building design. Energy 2023, 274, 127334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quan, S.J. Comparing hyperparameter tuning methods in machine learning based urban building energy modeling: A study in Chicago. Energy Build. 2024, 317, 114353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villano, F.; Mauro, G.M.; Pedace, A. A Review on Machine/Deep Learning Techniques Applied to Building Energy Simulation, Optimization and Management. Thermo 2024, 4, 100–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karmaker, S.K.; Hassan, M.M.; Smith, M.J.; Xu, L.; Zhai, C.; Veeramachaneni, K. AutoML to Date and Beyond: Challenges and Opportunities. ACM Comput. Surv. 2021, 54, 175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bahri, M.; Salutari, F.; Putina, A.; Sozio, M. AutoML: State of the art with a focus on anomaly detection, challenges, and research directions. Int. J. Data Sci. Anal. 2022, 14, 113–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, H.; Yu, K.; Xie, F.; Liu, M.; Sun, S. Automated machine learning with interpretation: A systematic review of methodologies and applications in healthcare. Med. Adv. 2024, 2, 205–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Truong, A.; Walters, A.; Goodsitt, J.; Hines, K.; Bruss, C.B.; Farivar, R. Towards Automated Machine Learning: Evaluation and Comparison of AutoML Approaches and Tools. In Proceedings of the 2019 IEEE 31st International Conference on Tools with Artificial Intelligence (ICTAI), Portland, OR, USA, 4–6 November 2019; pp. 1471–1479. [Google Scholar]

- He, X.; Zhao, K.; Chu, X. AutoML: A survey of the state-of-the-art. Knowl.-Based Syst. 2021, 212, 106622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biessmann, F.; Kamble, B.; Streblow, R. An Automated Machine Learning Approach towards Energy Saving Estimates in Public Buildings. Energies 2023, 16, 6799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alkhulaifi, N.; Bowler, A.L.; Pekaslan, D.; Triguero, I.; Watson, N.J. Exploring Automated Feature Engineering for Energy Consumption Forecasting with AutoML. In Proceedings of the 2024 IEEE International Conference on Systems, Man, and Cybernetics (SMC), Kuching, Malaysia, 6–10 October 2024; pp. 2993–2998. [Google Scholar]

- Li, D.; Qi, Z.; Zhou, Y.; Elchalakani, M. Machine Learning Applications in Building Energy Systems: Review and Prospects. Buildings 2025, 15, 648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khalil, M.; McGough, A.S.; Pourmirza, Z.; Pazhoohesh, M.; Walker, S. Machine Learning, Deep Learning and Statistical Analysis for forecasting building energy consumption—A systematic review. Eng. Appl. Artif. Intell. 2022, 115, 105287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michailidis, P.; Michailidis, I.; Minelli, F.; Coban, H.H.; Kosmatopoulos, E. Model Predictive Control for Smart Buildings: Applications and Innovations in Energy Management. Buildings 2025, 15, 3298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elbeltagi, E.; Wefki, H.; Abdrabou, S.; Dawood, M.; Ramzy, A. Visualized strategy for predicting buildings energy consumption during early design stage using parametric analysis. J. Build. Eng. 2017, 13, 127–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Chan, I.Y.; Dong, Z.; Samuel, T.A. Unraveling Trust in Collaborative Human-Machine Intelligence from Neurophysiological Perspective: A Review of EEG and fNIRS Features. Adv. Eng. Inf. 2025, 67, 103555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, Z.Q.; Shah, K.W.; Gupta, M. Autonomous Mobile Robots Inclusive Building Design for Facilities Management: Comprehensive PRISMA Review. Buildings 2024, 14, 3615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Dong, Z.; Chan Isabelle, Y.S. Biometric Evaluation and Immersive Construction Environments: A Research Overview of the Current Landscape, Challenges, and Future Prospects. J. Constr. Eng. Manag. 2025, 151, 03125005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Popat, S.; Starkey, L. Learning to code or coding to learn? A systematic review. Comput. Educ. 2019, 128, 365–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bower, I.; Tucker, R.; Enticott, P.G. Impact of built environment design on emotion measured via neurophysiological correlates and subjective indicators: A systematic review. J. Environ. Psychol. 2019, 66, 101344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gray, R. Why do all systematic reviews have fifteen studies? Nurse Author Ed. 2020, 30, 27–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Edison, H.; Khanna, D.; Rafiq, U. How Many Papers Should You Review? A Research Synthesis of Systematic Literature Reviews in Software Engineering. In Proceedings of the 2023 ACM/IEEE International Symposium on Empirical Software Engineering and Measurement (ESEM), New Orleans, LA, USA, 26–27 October 2023; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Bassi, A.; Shenoy, A.; Sharma, A.; Sigurdson, H.; Glossop, C.; Chan, J.H. Building Energy Consumption Forecasting: A Comparison of Gradient Boosting Models. In Proceedings of the 12th International Conference on Advances in Information Technology, Bangkok, Thailand, 29 June–1 July 2021; p. 27. [Google Scholar]

- Dai, Z.; Huang, W. Improving energy management practices through accurate building energy consumption prediction: Analyzing the performance of LightGBM, RF, and XGBoost models with advanced optimization strategies. Electr. Eng. 2025, 107, 12583–12605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoon, H.I.; Lee, H.; Yang, J.-S.; Choi, J.-H.; Jung, D.-H.; Park, Y.J.; Park, J.-E.; Kim, S.M.; Park, S.H. Predicting Models for Plant Metabolites Based on PLSR, AdaBoost, XGBoost, and LightGBM Algorithms Using Hyperspectral Imaging of Brassica juncea. Agriculture 2023, 13, 1477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feurer, M.; Eggensperger, K.; Falkner, S.; Lindauer, M.; Hutter, F. Auto-sklearn 2.0: The next generation. arXiv 2020, arXiv:2007.04074. [Google Scholar]

- Erickson, N.; Mueller, J.; Shirkov, A.; Zhang, H.; Larroy, P.; Li, M.; Smola, A. Autogluon-tabular: Robust and accurate automl for structured data. arXiv 2020, arXiv:2003.06505. [Google Scholar]

- LeDell, E.; Poirier, S. H2O automl: Scalable automatic machine learning. In Proceedings of the AutoML Workshop at ICML, Virtual, 18 July 2020; p. 24. [Google Scholar]

- Hutter, F.; Kotthoff, L.; Vanschoren, J. Automated Machine Learning: Methods, Systems, Challenges; Springer Nature: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Sheng, Y.; Arbabi, H.; Ward, W.O.C.; Álvarez, M.A.; Mayfield, M. City-scale residential energy consumption prediction with a multimodal approach. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 5313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garrett, A.; New, J.R. Suitability of ASHRAE Guideline 14 Metrics for Calibration; Oak Ridge National Laboratory (ORNL): Oak Ridge, TN, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Malinverno, L.; Barros, V.; Ghisoni, F.; Visonà, G.; Kern, R.; Nickel, P.J.; Ventura, B.E.; Šimić, I.; Stryeck, S.; Manni, F. A historical perspective of biomedical explainable AI research. Patterns 2023, 4, 100830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Liang, Q.; Hancock, J.T.; Khoshgoftaar, T.M. Feature selection strategies: A comparative analysis of SHAP-value and importance-based methods. J. Big Data 2024, 11, 44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, Z.; Zhang, J.; Xiao, F.; Chen, Z.; Xu, K.; So, P.M.; Lau, K.T. An AI-enabled optimal control strategy utilizing dual-horizon load predictions for large building cooling systems and its cloud-based implementation. Energy Build. 2025, 330, 115352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Zhao, X.; Qin, S.J. Dynamically engineered multi-modal feature learning for predictions of office building cooling loads. Appl. Energy 2024, 355, 122183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Lu, J.; Huang, J.; Zhao, Y. End-to-end data-driven modeling framework for automated and trustworthy short-term building energy load forecasting. Build. Simul. 2024, 17, 1419–1437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, Y.; Chen, P. Energy retrofitting of hospital buildings considering climate change: An approach integrating automated machine learning with NSGA-III for multi-objective optimization. Energy Build. 2024, 319, 114571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, H.; Zhang, L.; Yang, H.; Shi, Y. Optimizing thermal comfort and energy efficiency in hospitals with PCM-Enhanced wall systems. Energy Build. 2024, 323, 114740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alshammari, T.; Ramadan, R.A.; Ahmad, A. Temporal Variations Dataset for Indoor Environmental Parameters in Northern Saudi Arabia. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 7326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zucchini, N.; Capozzella, E.; Giuffrè, M.; Mastronardi, M.; Casagranda, B.; Crocè, S.L.; de Manzini, N.; Palmisano, S. Advanced Non-linear Modeling and Explainable Artificial Intelligence Techniques for Predicting 30-Day Complications in Bariatric Surgery: A Single-Center Study. Obes. Surg. 2024, 34, 3627–3638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mörth, M.; Heinz, A.; Heimrath, R.; Edtmayer, H.; Mach, T.; Kaisermayer, V.; Gölles, M.; Hochenauer, C. Grey-Box Model for Efficient Building Simulations: A Case Study of an Integrated Water-Based Heating and Cooling System. Buildings 2025, 15, 1959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shirzadi, N.; Lau, D.; Stylianou, M. Surrogate Modeling for Building Design: Energy and Cost Prediction Compared to Simulation-Based Methods. Buildings 2025, 15, 2361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cruz, G.G.; Kor, A.-L.; Jawad, N.; Georges, J.-P. Exploring the Costs of Automation: A Comparative Study on the Energy Consumption and Performance of Open-Source Automated Machine and Deep Learning Libraries. In Proceedings of the International Sustainable Ecological Engineering Design for Society (SEEDS) Conference 2025, Loughborough, UK, 3–5 September 2025. [Google Scholar]

| Criteria | Physical-Driven Modeling | Data-Driven Modeling |

|---|---|---|

| Nature of analysis | “white-box” | “black-box” |

| Knowledge | Intensive | Less intensive |

| Setting time | High | Low |

| Analysis approach | Use of simulation software, such as EnergyPlus and DesignBuilder | Machine learning, deep learning. |

| ID | Variables | Types | Explanations | Value Range |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Walls | Categorical | Represents the type of wall construction. Four categories: Brick, aluminum plate, glass curtain, and steel curtain. | [‘Single wall’, ’Double wall’, ‘Double red brick wall with air gap’] |

| 2 | Roof | Categorical | Represents the type of roof construction. Two categories: type 1 and type 2. | [‘Floor slab 15 cm’, ‘Floor slab 20 cm’] |

| 3 | SOG | Categorical | Represents the type of slab-on-grade construction. Two categories: type 1 and type 2. | [‘Ground Floor 15 cm’, ‘Ground Floor 20 cm’] |

| 4 | Length | Numerical (number) | Represents the building shape dimension. | Min. 10.0 m Max. 30.0 m |

| 5 | Depth | Numerical (number) | Represents the building shape dimension. | Min. 10.0 m Max. 30.0 m |

| 6 | Height | Numerical (number) | Represents the building shape dimension. | Min. 3.0 m Max. 15.0 m |

| 7 | Orientation | Numerical (degree) | Represents the building orientation angle. | Min. 0° Max. 360ᵒ |

| 8 | South | Numerical (percentage) | Represents the windows-to-wall ratio in the south direction. | Min. 0% Max. 80% |

| 9 | East | Numerical (percentage) | Represents the windows-to-wall ratio in the east direction. | Min. 0% Max. 80% |

| 10 | North | Numerical (percentage) | Represents the windows-to-wall ratio in the north direction. | Min. 0% Max. 80% |

| 11 | West | Numerical (percentage) | Represents the windows-to-wall ratio in the west direction. | Min. 0% Max. 80% |

| 12 | U-Value | Numerical (number) | Glass U values. | Min. 0 Max. 1.2 (Default) |

| 13 | SHGC | Numerical (number) | Glass Solar Heat Gain Coefficient. | Min. 0 Max. 1.0 |

| 14 | VT | Numerical (number) | Glass visual transmittance. | Min. 0 Max. 1.0 |

| 15 | Heating_SP | Numerical (number) | Heating set points. | Min. 18° Max. 28ᵒ |

| 16 | Cooling_SP | Numerical (number) | Cooling set points. | Min. 18° Max. 26ᵒ |

| 17 | pEUI | Numerical (number) | Energy use for the project is based on molded site energy, which represents the summation of heating, cooling, lighting, and equipment energy consumed in one year, measured in KWh. |

| Feature | Mean | St.D. | Min. | Med. | Max. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Length | 20.012 | 5.735 | 10.000 | 20.020 | 30.000 |

| Depth | 20.078 | 5.776 | 10.000 | 20.205 | 30.000 |

| Height | 9.466 | 3.171 | 4.000 | 9.460 | 15.000 |

| Orientation | 179.935 | 104.749 | 0.000 | 180.000 | 360.000 |

| South | 0.398 | 0.232 | 0.000 | 0.400 | 0.800 |

| East | 0.398 | 0.231 | 0.000 | 0.400 | 0.800 |

| North | 0.398 | 0.231 | 0.000 | 0.400 | 0.800 |

| West | 0.399 | 0.231 | 0.000 | 0.400 | 0.800 |

| UValue | 0.619 | 0.341 | 0.010 | 0.630 | 1.200 |

| SHGC | 0.499 | 0.285 | 0.010 | 0.500 | 0.990 |

| VT | 0.502 | 0.287 | 0.010 | 0.500 | 0.990 |

| Heating_SP | 9.988 | 1.419 | 8.000 | 10.000 | 12.000 |

| Cooling_SP | 22.966 | 3.163 | 18.000 | 23.000 | 28.000 |

| pEUI | 51,612.500 | 27,344.366 | 6903.000 | 45,336.500 | 214,820.000 |

| Models | R2 | RMSE | MAE |

|---|---|---|---|

| StackedEnsemble_AllModels_1_AutoML_1_20250716_112613 | 0.989 | 4.754 | 2.296 |

| StackedEnsemble_BestOfFamily_1_AutoML_1_20250716_112613 | 0.981 | 4.917 | 2.448 |

| GBM_1_AutoML_1_20250716_112613 | 0.979 | 5.297 | 2.832 |

| GBM_5_AutoML_1_20250716_112613 | 0.975 | 5.358 | 2.993 |

| GBM_grid_1_AutoML_1_20250716_112613_model_1 | 0.973 | 5.440 | 3.033 |

| GBM_2_AutoML_1_20250716_112613 | 0.954 | 5.508 | 3.170 |

| GBM_3_AutoML_1_20250716_112613 | 0.948 | 5.659 | 3.282 |

| GBM_grid_1_AutoML_1_20250716_112613_model_2 | 0.937 | 5.660 | 3.233 |

| XGBoost_3_AutoML_1_20250716_112613 | 0.922 | 5.757 | 3.646 |

| DeepLearning_grid_1_AutoML_1_20250716_112613_model_1 | 0.916 | 5.888 | 2.918 |

| Model | R2 for Test Set | R2 for Validation Test |

|---|---|---|

| ExtraTreesMSE_BAG_L2 | 0.994 | 0.982 |

| WeightedEnsemble_L3 | 0.993 | 0.983 |

| CatBoost_BAG_L2 | 0.993 | 0.979 |

| LightGBM_BAG_L2 | 0.993 | 0.981 |

| RandomForestMSE_BAG_L2 | 0.992 | 0.981 |

| XGBoost_BAG_L2 | 0.992 | 0.980 |

| NeuralNetFastAI_BAG_L2 | 0.992 | 0.982 |

| LightGBMXT_BAG_L2 | 0.992 | 0.978 |

| CatBoost_BAG_L1 | 0.992 | 0.982 |

| WeightedEnsemble_L2 | 0.992 | 0.982 |

| LightGBMXT_BAG_L1 | 0.986 | 0.970 |

| LightGBM_BAG_L1 | 0.983 | 0.970 |

| NeuralNetFastAI_BAG_L1 | 0.975 | 0.957 |

| ExtraTreesMSE_BAG_L1 | 0.941 | 0.924 |

| RandomForestMSE_BAG_L1 | 0.935 | 0.919 |

| KNeighborsDist_BAG_L1 | 0.761 | 0.743 |

| KNeighborsUnif_BAG_L1 | 0.759 | 0.740 |

| Model | R2 Score |

|---|---|

| standard_scaler_random_forest | 0.9138 |

| standard_scaler_gradient_boosting | 0.9315 |

| standard_scaler_linear_regression | 0.8645 |

| standard_scaler_ridge | 0.8645 |

| standard_scaler_lasso | 0.8645 |

| standard_scaler_elastic_net | 0.7671 |

| standard_scaler_svr | 0.655 |

| Model | R2 | RMSE | MAE |

|---|---|---|---|

| Linear Regression | 0.880 | 9.364 | 6.671 |

| Random Forest | 0.934 | 6.964 | 4.545 |

| Naive Bayes | 0.711 | 7.467 | 9.896 |

| XGBoost | 0.966 | 5.013 | 3.454 |

| LightGBM | 0.973 | 4.447 | 2.745 |

| AdaBoost | 0.478 | 19.520 | 17.354 |

| H2O | 0.982 | 3.653 | 2.057 |

| AutoGluon | 0.993 | 2.280 | 1.116 |

| AutoSklearn | 0.947 | 6.235 | 3.855 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Tang, Z.; Chen, J.; Cheng, J. Benchmarking Automated Machine Learning for Building Energy Performance Prediction: A Comparative Study with SHAP-Based Interpretability. Buildings 2026, 16, 185. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings16010185

Tang Z, Chen J, Cheng J. Benchmarking Automated Machine Learning for Building Energy Performance Prediction: A Comparative Study with SHAP-Based Interpretability. Buildings. 2026; 16(1):185. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings16010185

Chicago/Turabian StyleTang, Zuyi, Jinyu Chen, and Jiayu Cheng. 2026. "Benchmarking Automated Machine Learning for Building Energy Performance Prediction: A Comparative Study with SHAP-Based Interpretability" Buildings 16, no. 1: 185. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings16010185

APA StyleTang, Z., Chen, J., & Cheng, J. (2026). Benchmarking Automated Machine Learning for Building Energy Performance Prediction: A Comparative Study with SHAP-Based Interpretability. Buildings, 16(1), 185. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings16010185