An Evolutionary Game-Based Governance Mechanism for Sustainable Medical and Elderly Care Building Retrofits in Urban Renewal

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Evolutionary Game Applications in Integrated Medical and Elderly Care Collaboration

2.2. Governance, Incentive Mechanisms, and Opportunistic Behavior in the Transformation of Integrated Medical and Elderly Care

2.3. Limitations of Existing Research and Contributions of This Study

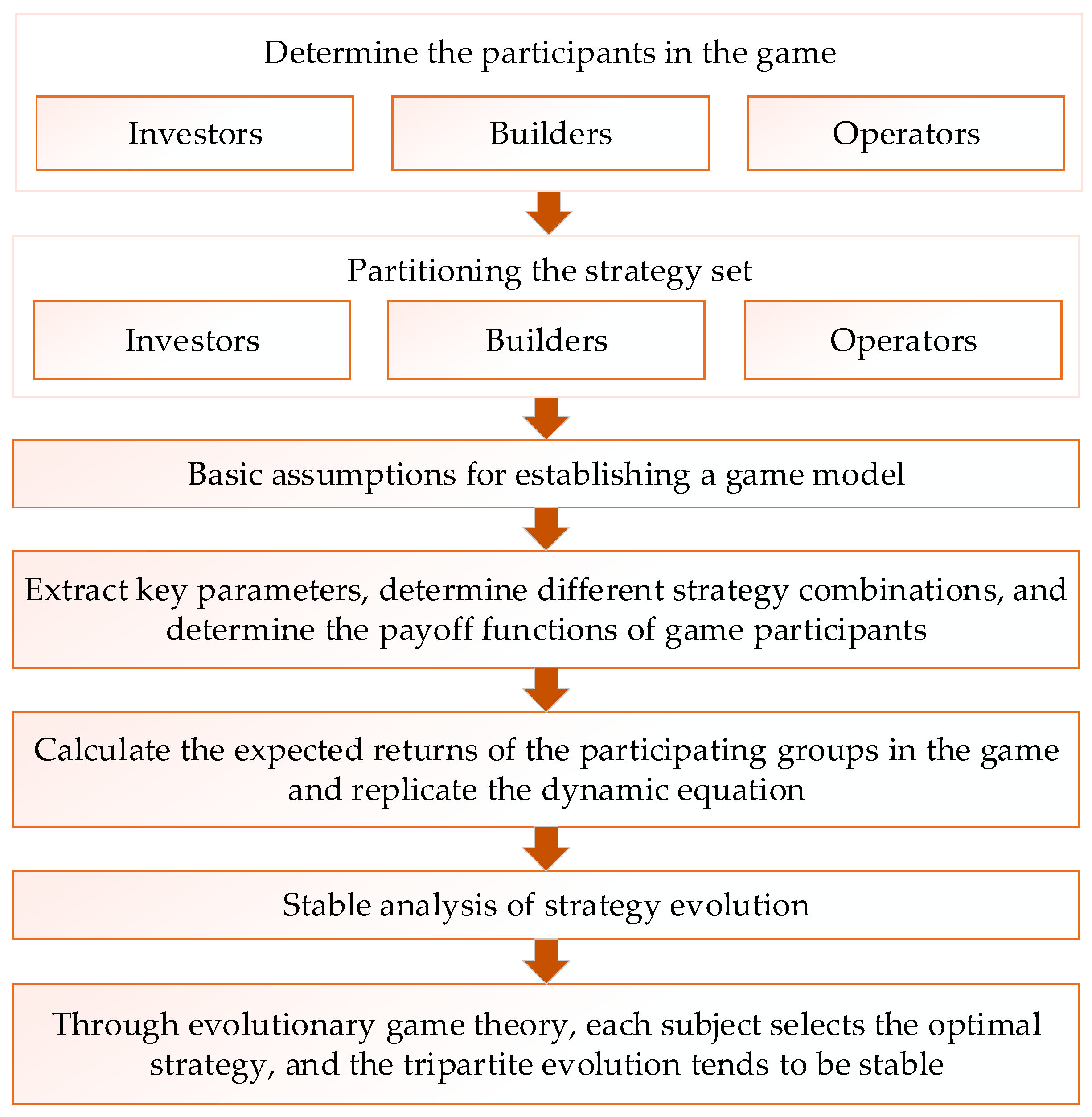

3. Methodology: Evolutionary Game Model for Building Retrofit Governance

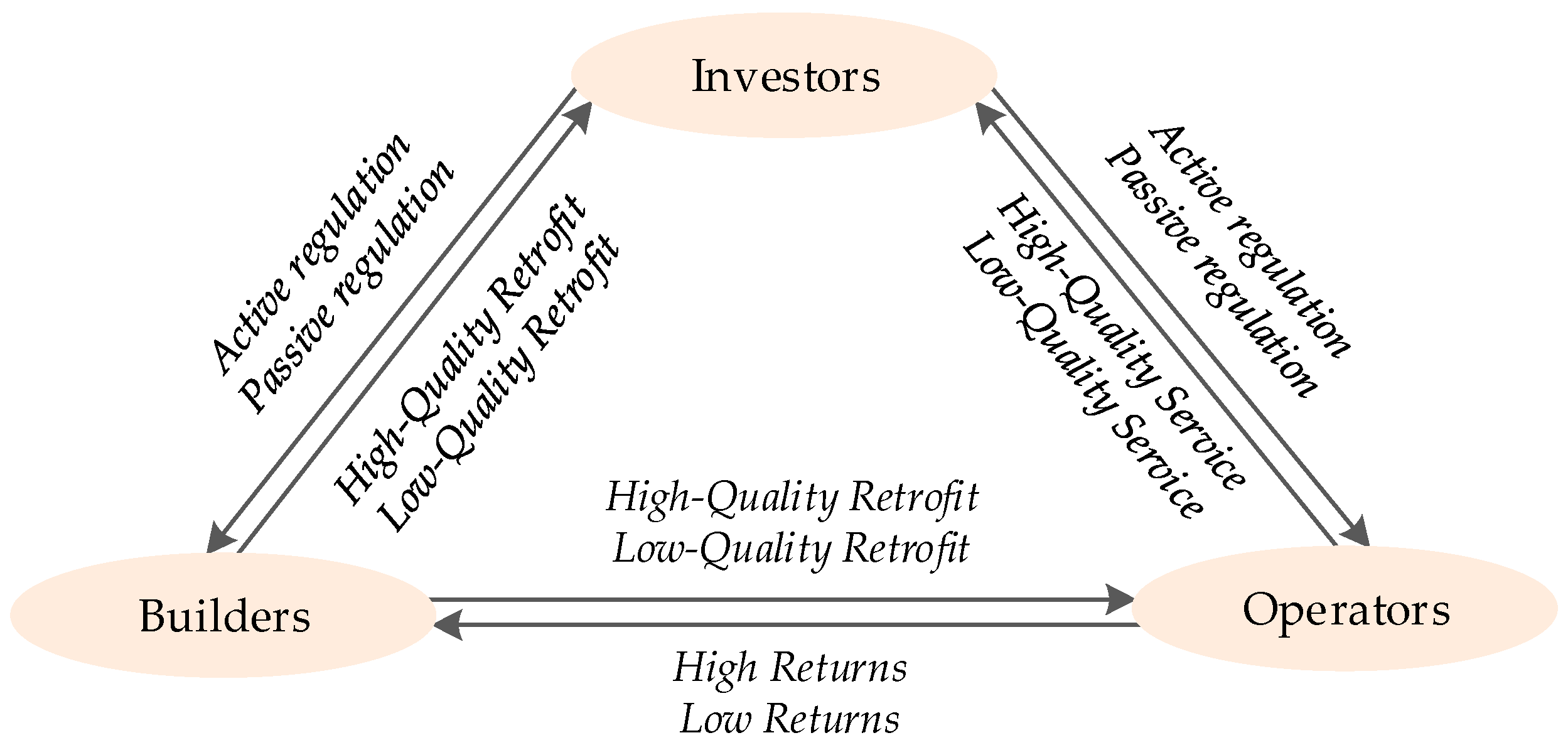

3.1. Determining the Game Players and Methodology

3.2. Model Assumptions

3.3. Construction of the Payoff Matrix

4. Model Analysis and Theoretical Results

4.1. Equilibrium Points Solution

4.2. Evolutionary Stability Strategy Analysis

5. Case Simulation: Medical and Elderly Care Retrofit in Lanzhou

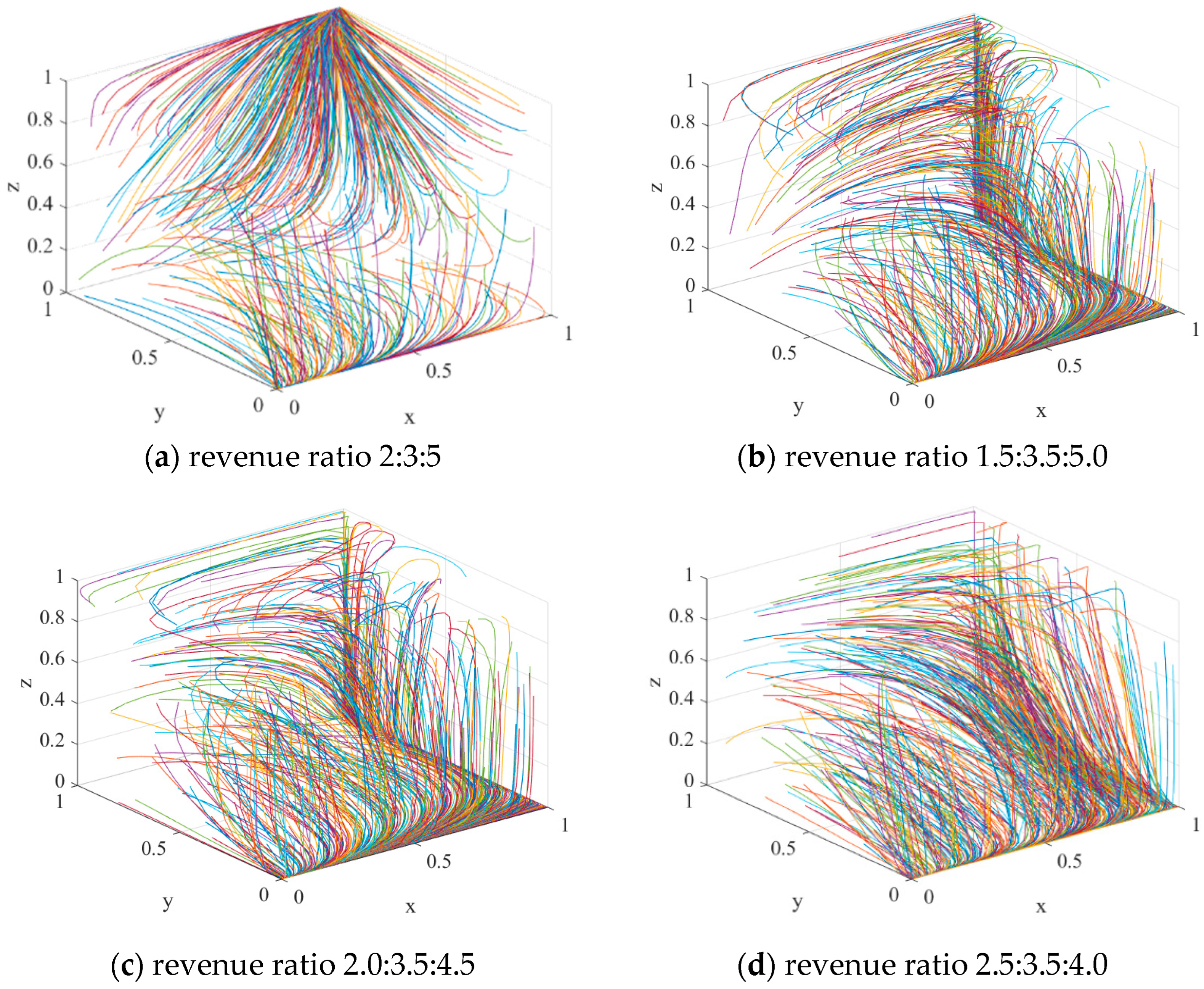

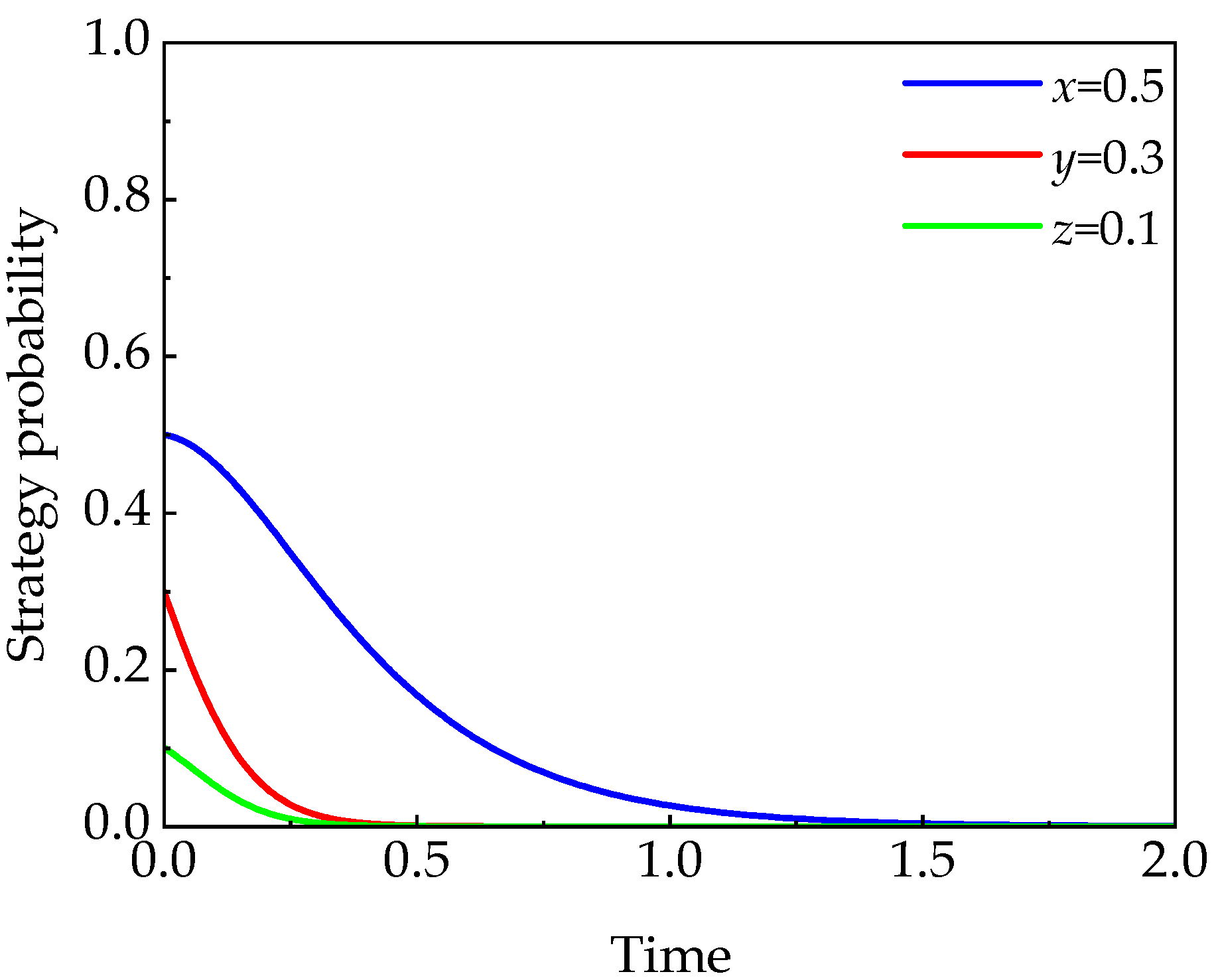

5.1. Parameter Calibration and Initial Simulation Results

5.2. Sensitivity Analysis of Key Policy-Level Parameters

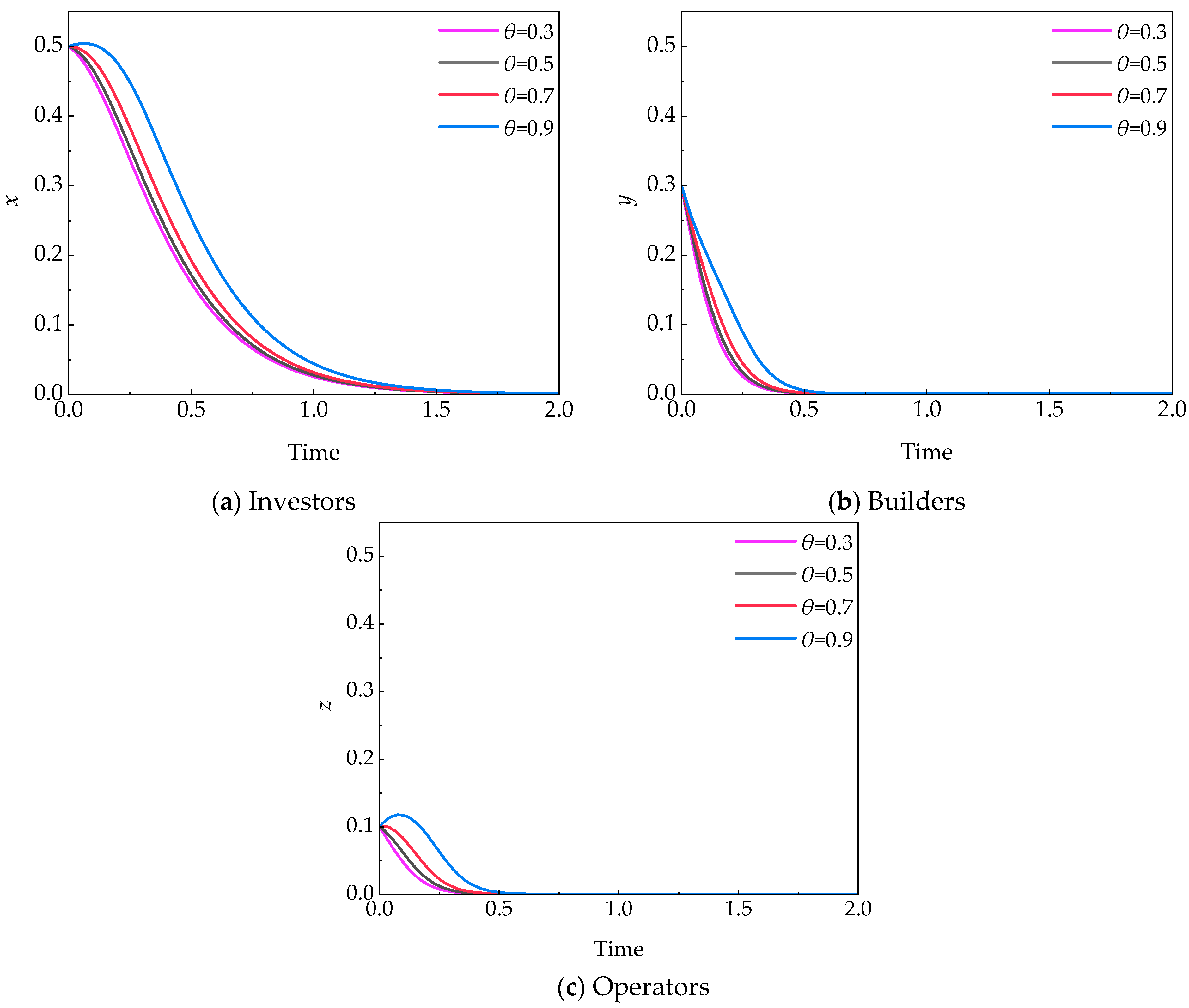

5.2.1. Policy Preference (θ)

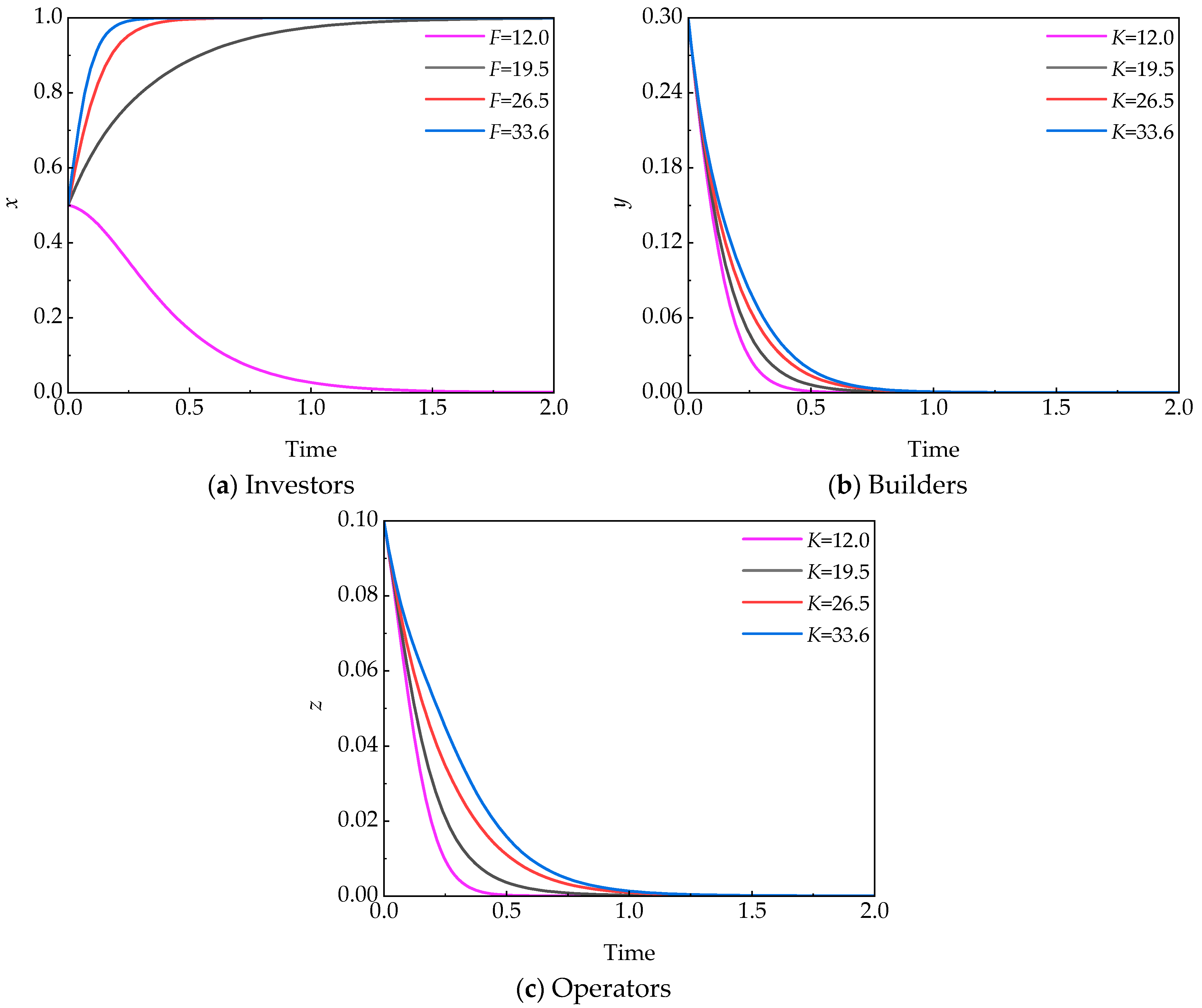

5.2.2. Responsibility Cost (K)

5.3. Sensitivity Analysis of Key Economic Parameters

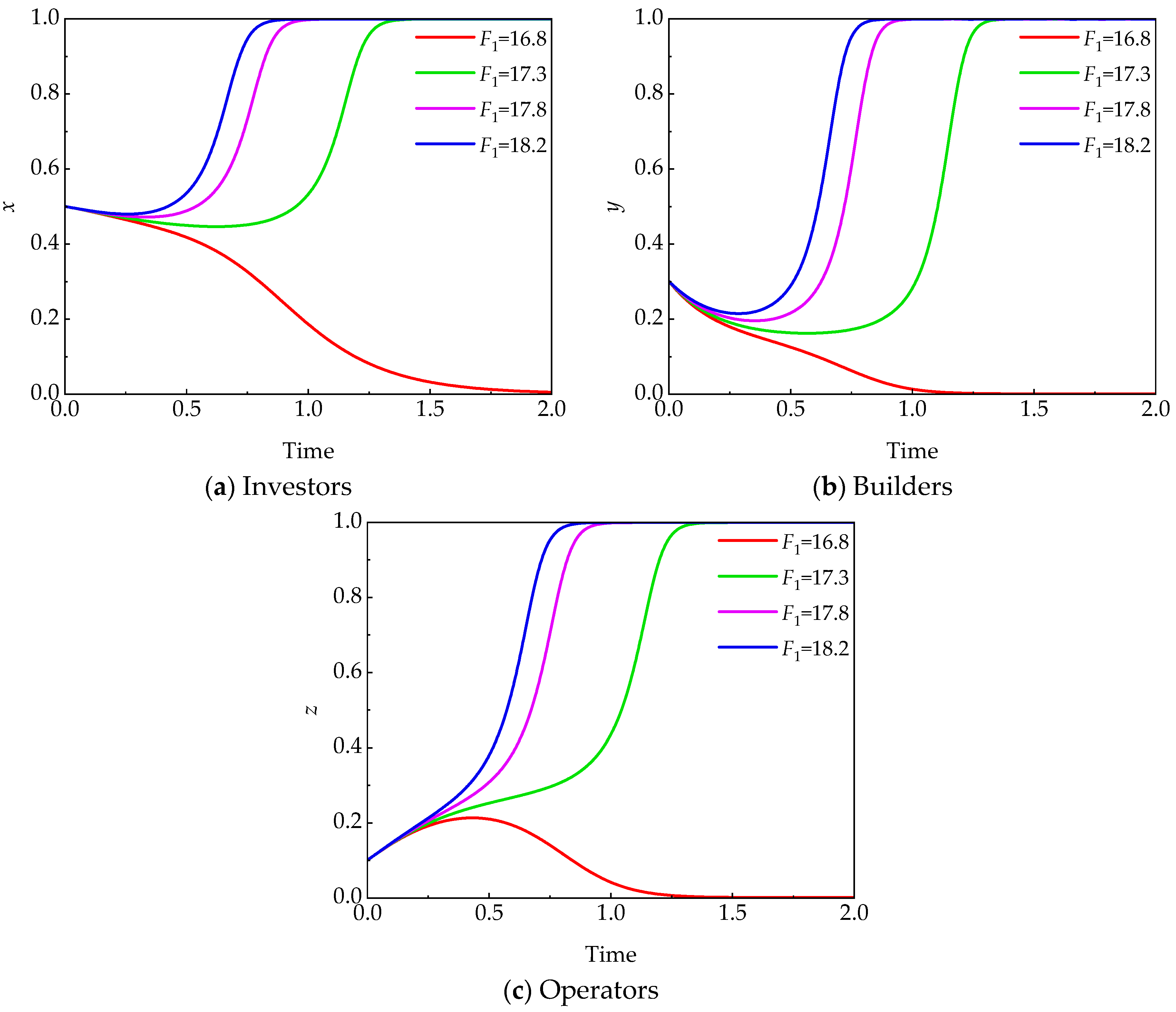

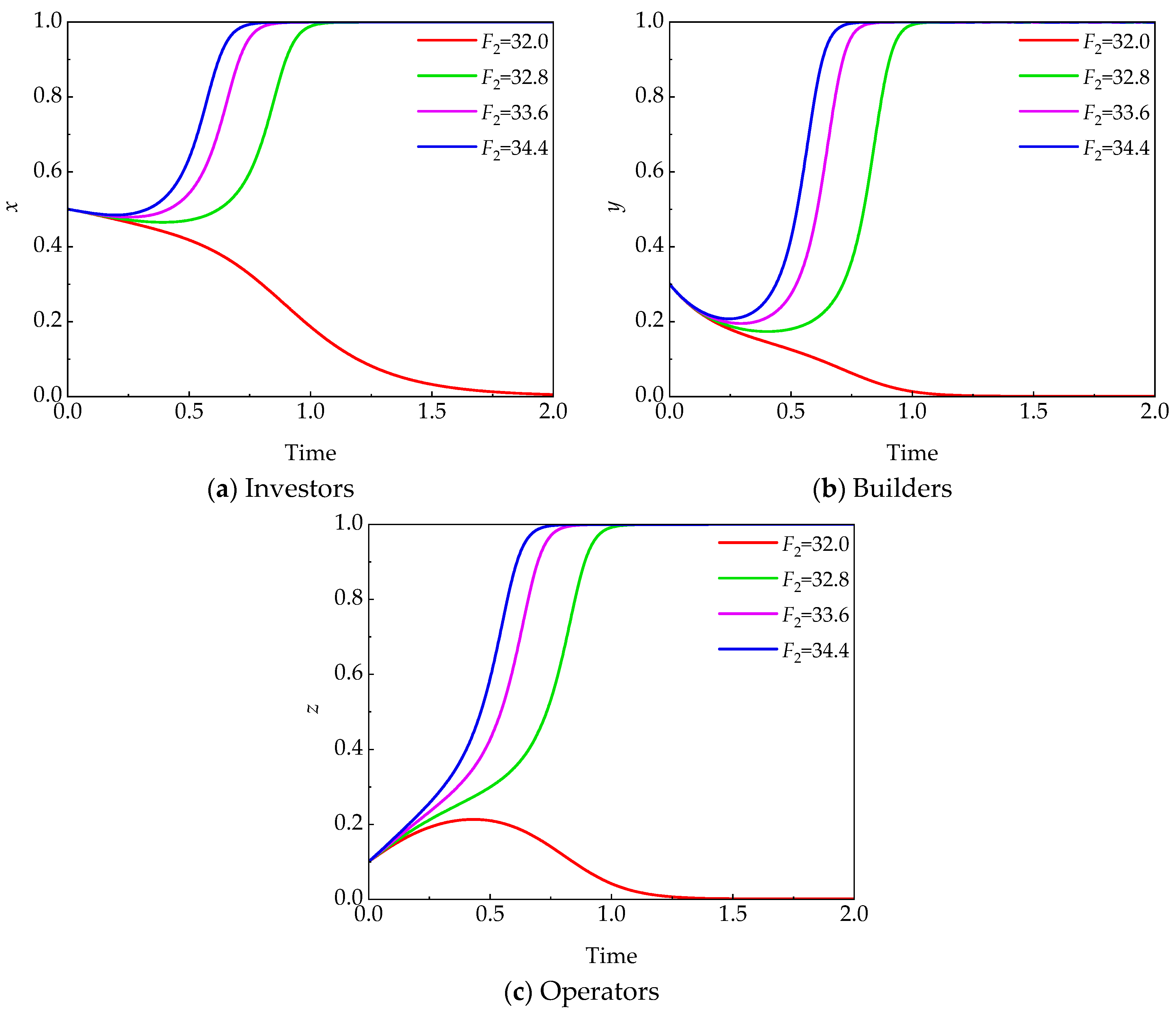

5.3.1. Penalty Cost (Fi)

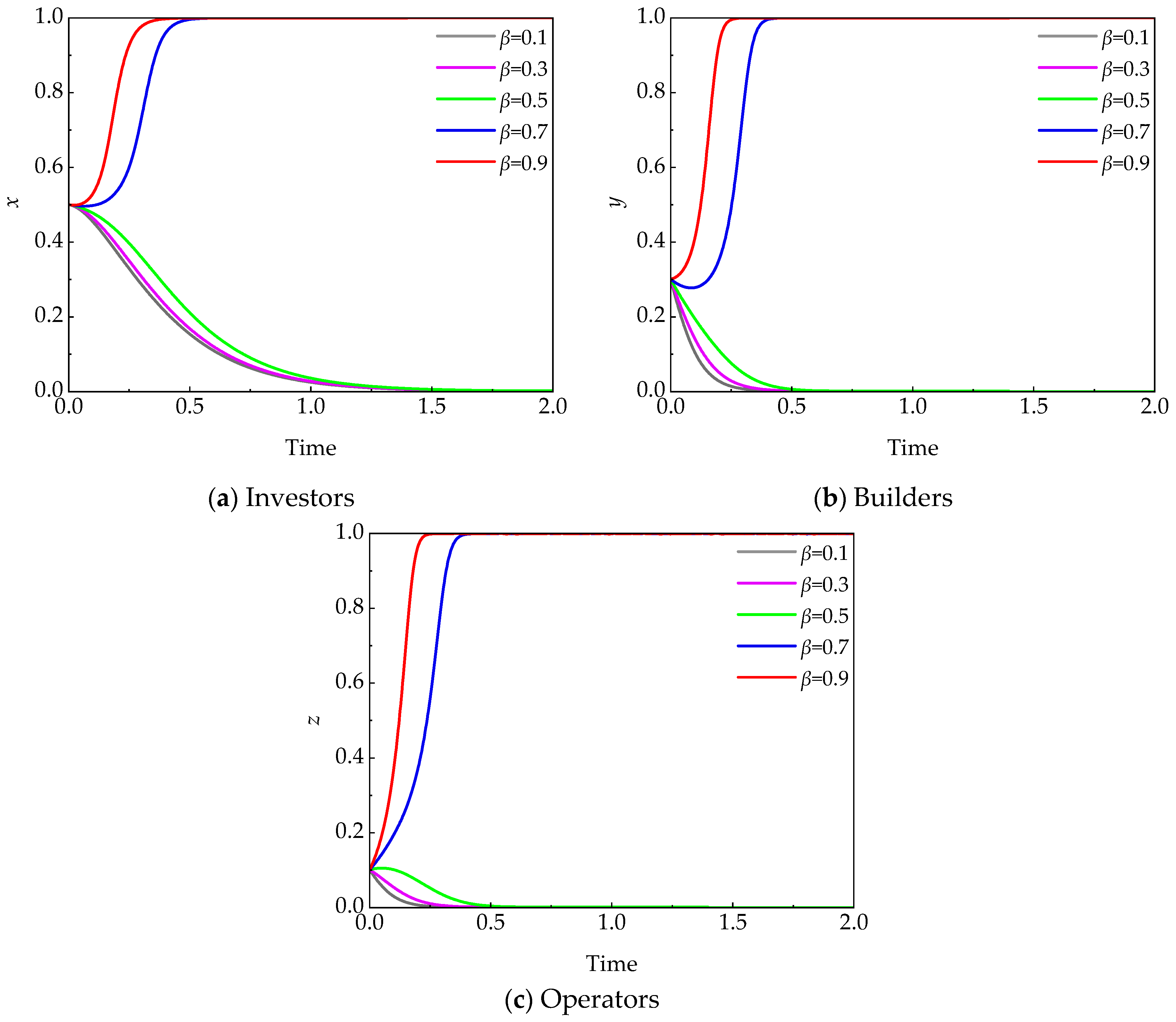

5.3.2. Economic Incentives Coefficient (β)

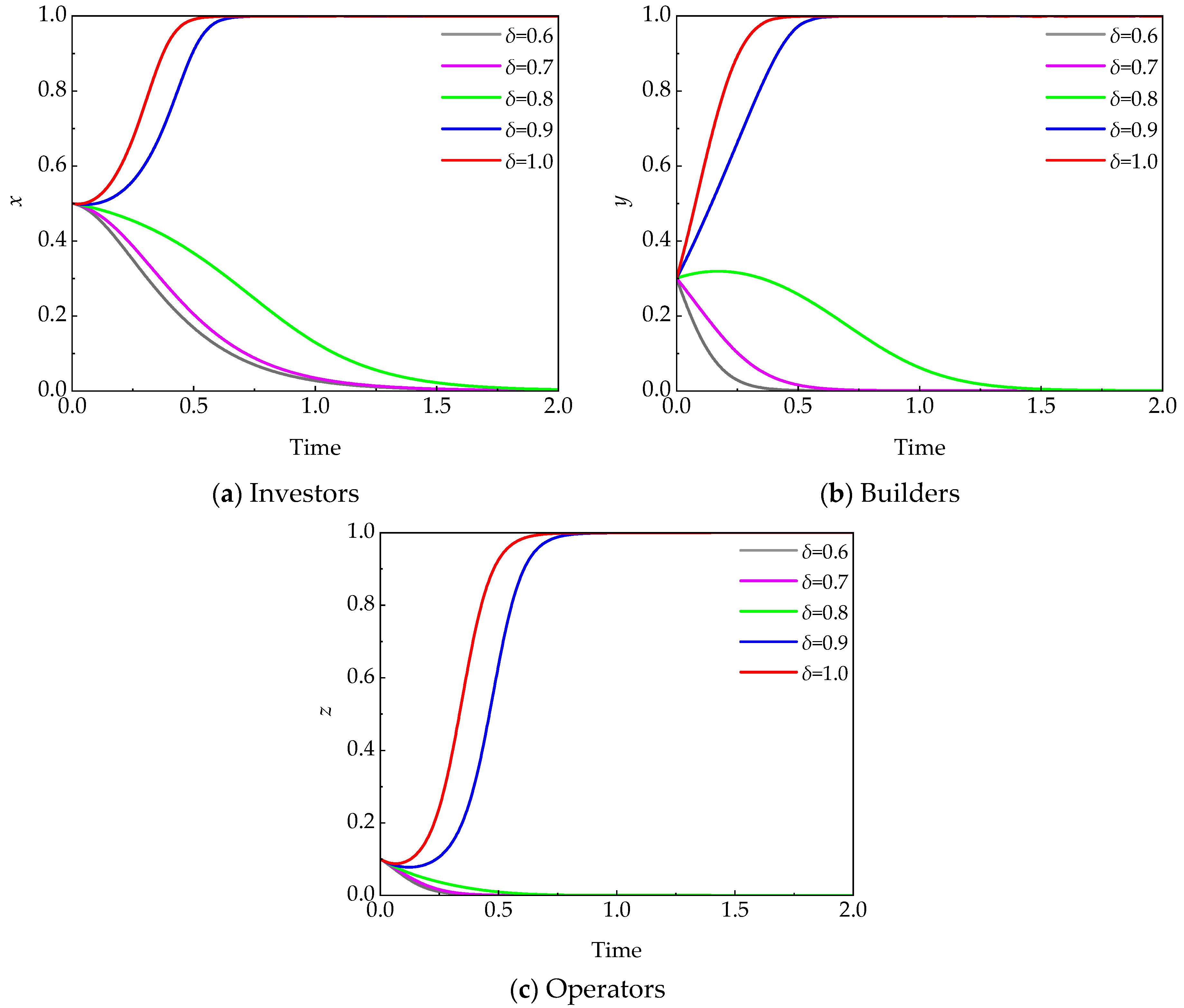

5.3.3. Quality Evaluation Coefficient (δ)

5.4. Sensitivity Analysis of Key Reputation-Related Parameters

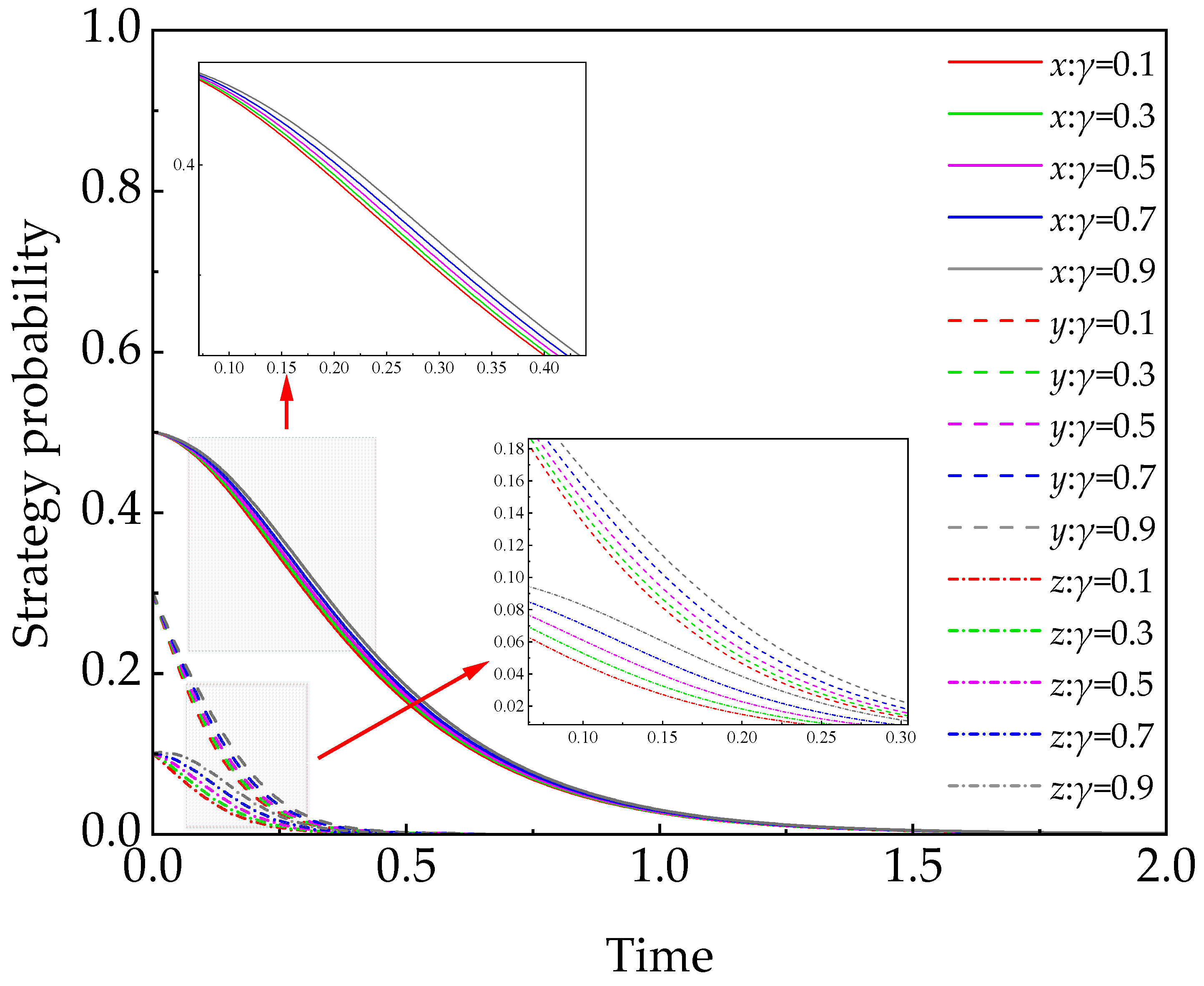

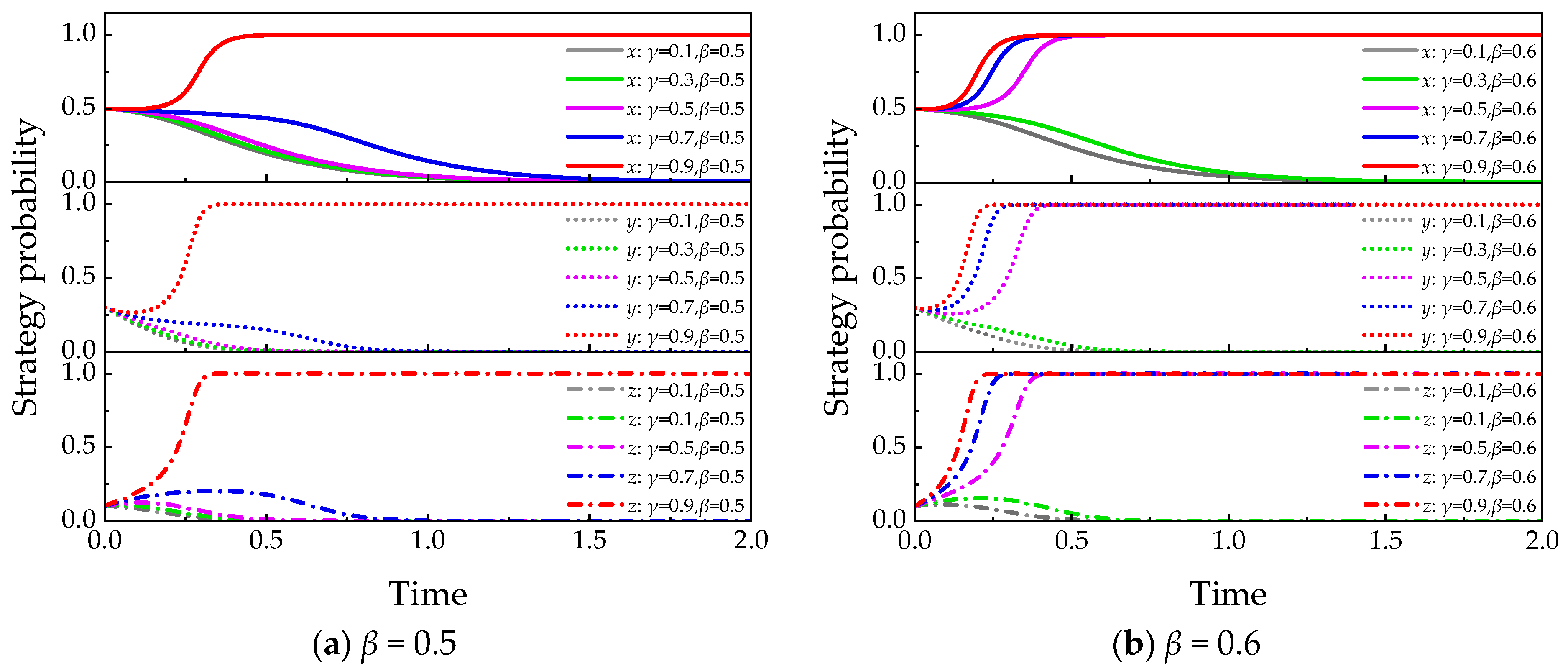

5.4.1. Reputational Incentives Coefficient (γ)

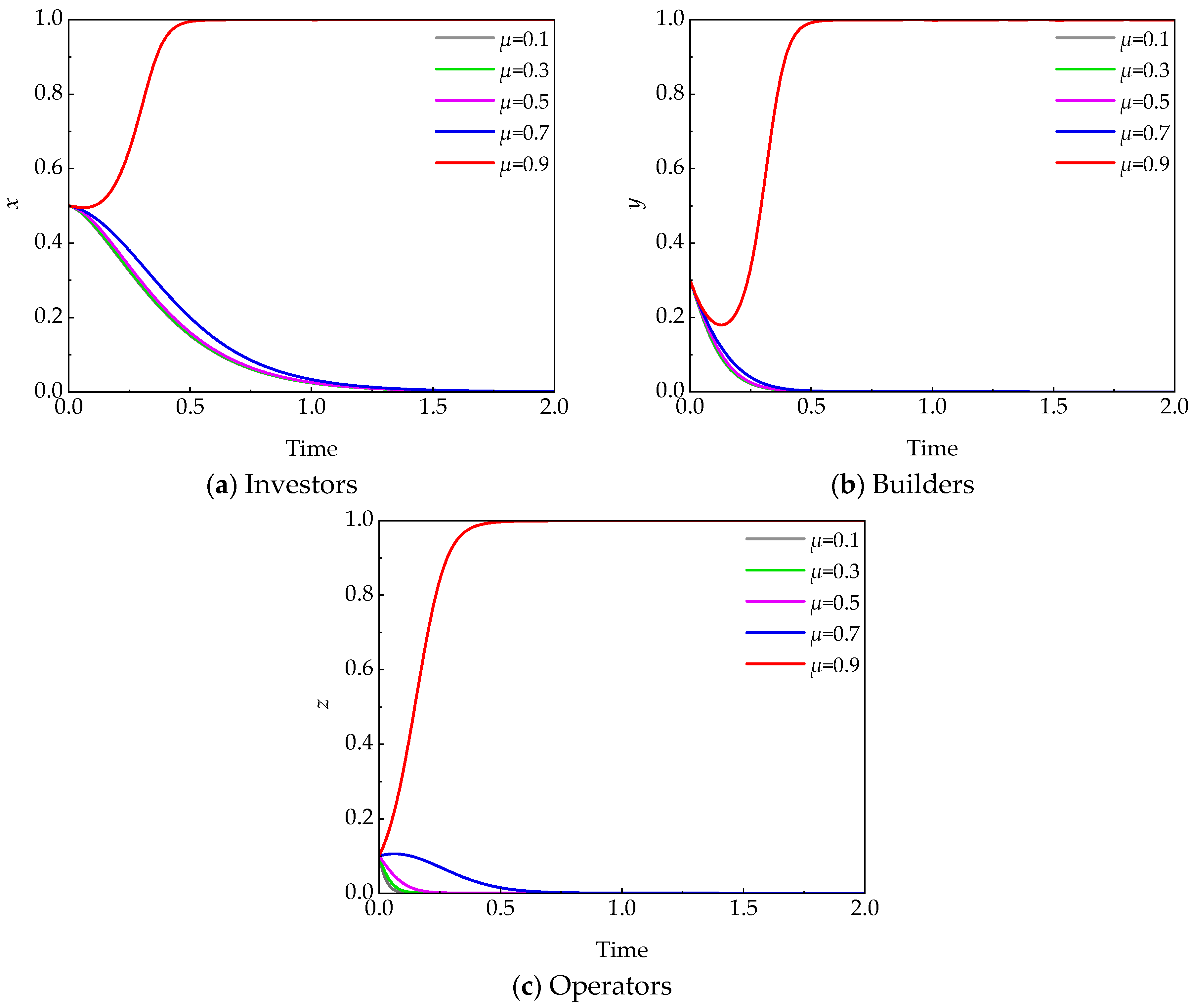

5.4.2. Demand Matching Coefficient (μ)

6. Discussion and Implications

6.1. Building Credible Commitment: A Synergistic Mechanism of Policy Preference and Economic Incentives

6.2. Reconstructing the Investors’ Role: From Passive Responder to Active Value Guardian

6.3. The Builders’ Pivotal Role: Targeted Governance and Trust Building Based on Asset Specificity

6.4. Sustained Motivation for the Operators: Building Dual Market-Based and Reputational Incentives

7. Conclusions

- (1)

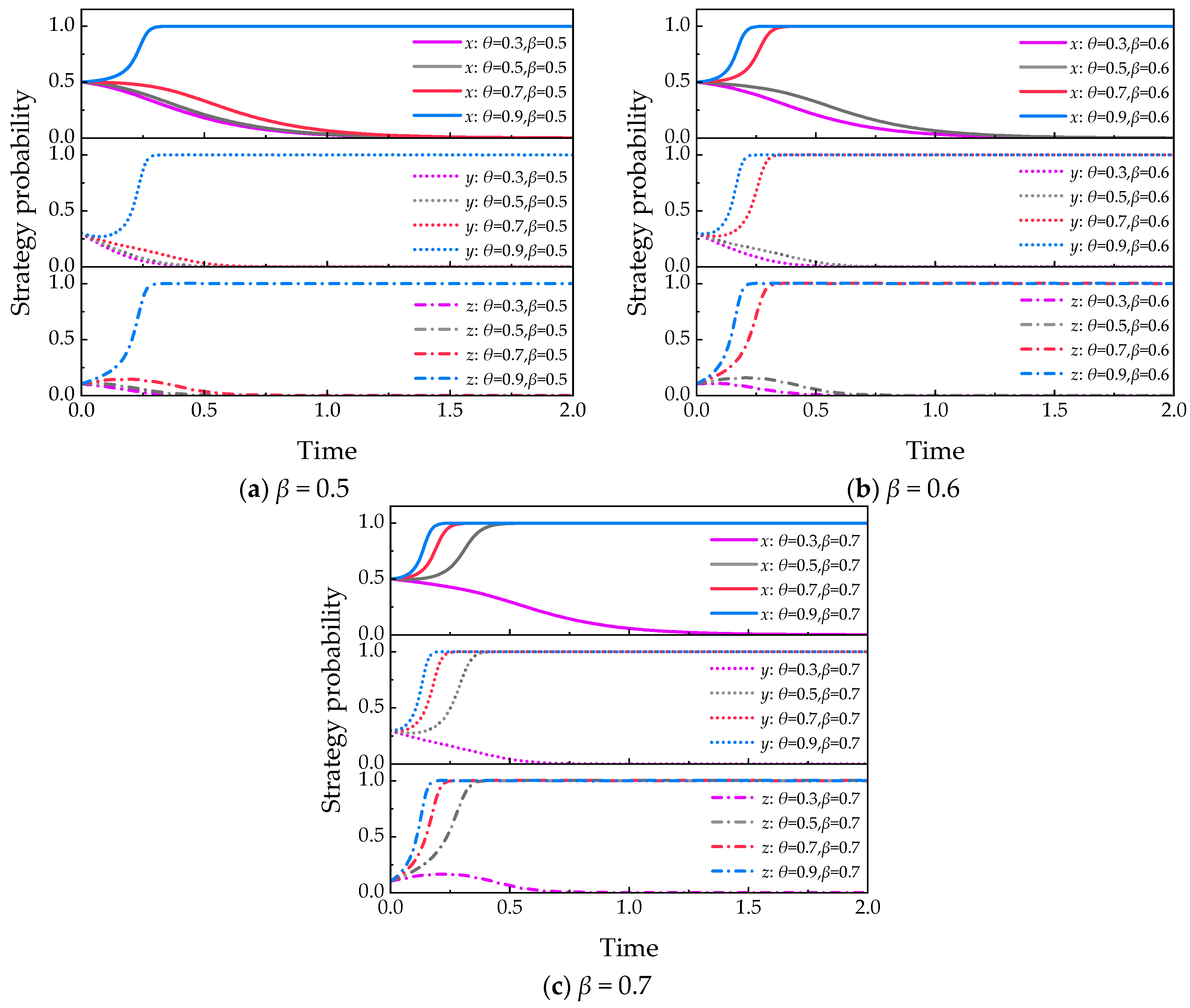

- Policy preferences (θ) alone are insufficient to maintain tripartite cooperation in the model. However, their impact is more significant when combined with economic incentives. As the economic incentive coefficient (β) increases from 0.5 to 0.7, the θ value required to maintain the ideal cooperative state decreases from 0.9 to 0.5, indicating that stronger economic incentives may partially compensate for the inadequacy of policy preferences.

- (2)

- Responsibility costs (K) reaching 12% of total economic benefits can incentivize investors to adopt active regulation. In contrast, its impact on the strategy choices of builders and operators is limited, mainly mitigating rather than reversing their tendency to non-cooperate.

- (3)

- Different agents exhibit varying sensitivities to penalties. In this study, a penalty cost of 17.3 (F1) is sufficient to motivate builders to adopt a cooperative strategy, while operators require a higher penalty cost (F2) of 32.8 to induce cooperative behavior. Meanwhile, the dominant strategy of builders still depends on the strategic choices of investors and operators, illustrating the interdependence among the stakeholders.

- (4)

- Economic incentives play a central role in promoting systemic cooperation. The economic incentive coefficient (β) exhibits a threshold effect (β ≥ 0.7); exceeding this value appears to be a necessary condition for accelerating the evolution of tripartite cooperation.

- (5)

- The higher the quality assessment coefficient (Δ), the greater the likelihood that investors choose active regulation. This suggests that when the quality of retrofit is closely related to investors’ long-term returns, investors may be motivated to maintain or even strengthen regulatory efforts, which in turn can accelerate the formation of tripartite cooperation strategies.

- (6)

- Reputation incentives (γ) alone are insufficient to promote stable tripartite cooperation. However, when combined with economic incentives, they help accelerate the evolution of cooperation and appear to lower the threshold of the economic incentive coefficient (β) required to trigger cooperative behavior.

8. Limitations and Future Research

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Fang, E.F.; Scheibye-Knudsen, M.; Jahn, H.J.; Li, J.; Ling, L.; Guo, H.; Zhu, X.; Preedy, V.; Lu, H.; Bohr, V.A.; et al. A research agenda for aging in China in the 21st century. Ageing Res. Rev. 2015, 24, 197–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UN Department of Economic and Social Affairs Population Division. World Population Prospects. 2024. Available online: https://population.un.org/wpp/ (accessed on 13 July 2025).

- Central People’s Government of the People’s Republic of China. 2024 National Bulletin on the Development of Aging. 2025. Available online: https://www.gov.cn/lianbo/bumen/202507/content_7033724.htm (accessed on 20 July 2025).

- Feng, Z.; Glinskaya, E.; Chen, H.; Gong, S.; Qiu, Y.; Xu, J.; Yip, W. Long-term care system for older adults in China: Policy landscape, challenges, and future prospects. Lancet 2020, 396, 1362–1372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, X.; Giles, J.; Yao, Y.; Yip, W.; Meng, Q.; Berkman, L.; Chen, H.; Chen, X.; Feng, J.; Feng, Z.; et al. The path to healthy ageing in China: A Peking University–Lancet Commission. Lancet 2022, 400, 1967–2006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Han, Z.; Deng, X.; Li, Z.; Huang, X. Mechanism and simulation of intensive use of urban inefficient land based on evolutionary game theory. J. Asian Econ. 2024, 95, 101840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buitelaar, E.; Moroni, S.; De Franco, A. Building obsolescence in the evolving city. Reframing property vacancy and abandonment in the light of urban dynamics and complexity. Cities 2021, 108, 102964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- General Office of the State Council of the People’s Republic of China. Opinions of the General Office of the Central Committee of the Communist Party of China and the General Office of the State Council on Continuing to Promote Urban Renewal Actions. 2025. Available online: https://www.gov.cn/zhengce/202505/content_7023880.htm (accessed on 19 July 2025).

- Yu, T.; Liang, X.; Shen, G.Q.; Shi, Q.; Wang, G. An optimization model for managing stakeholder conflicts in urban redevelopment projects in China. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 212, 537–547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mjörnell, K.; Femenías, P.; Annadotter, K. Retrofit strategies for multi-residential buildings from the record years in Sweden—Rrofit-driven or socioeconomically responsible? Sustainability 2019, 11, 6988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mok, K.Y.; Shen, G.Q.; Yang, J. Stakeholder management studies in mega construction projects: A review and future directions. Int. J. Proj. Manag. 2015, 33, 446–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aaltonen, K.; Kujala, J. A project lifecycle perspective on stakeholder influence strategies in global projects. Scand. J. Manag. 2010, 26, 381–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiang, L.; Tan, Y.; Jin, X.; Shen, G. Understanding stakeholders’ concerns of age-friendly communities at the briefing stage: A preliminary study in urban China. Eng. Constr. Archit. Manag. 2021, 28, 31–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, T.; Shen, G.Q.; Shi, Q.; Lai, X.; Li, C.Z.; Xu, K. Managing social risks at the housing demolition stage of urban redevelopment projects: A stakeholder-oriented study using social network analysis. Int. J. Proj. Manag. 2017, 35, 925–941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhuang, T.; Qian, Q.K.; Visscher, H.J.; Elsinga, M.G.; Wu, W. The role of stakeholders and their participation network in decision-making of urban renewal in China: The case of Chongqing. Cities 2019, 92, 47–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Zhang, J.; Zhao, X. Factors affecting green residential building development: Social network analysis. Sustainability 2018, 10, 1389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ning, X.; Ye, X.; Li, H.; Rajendra, D.; Skitmore, M. Evolutionary game analysis of optimal strategies for construction stakeholders in promoting the adoption of green building technology innovation. J. Constr. Eng. Manag. 2024, 150, 4024037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.D.; Zhang, J.Y.; Shen, G.Q.; Yan, Y.Y. Incentives for green retrofits: An evolutionary game analysis on Public-Private-Partnership reconstruction of buildings. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 232, 1076–1092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chu, X.; Shi, Z.; Yang, L.; Guo, S. Evolutionary game analysis on improving collaboration in sustainable urban regeneration: A multiple-stakeholder perspective. J. Urban Plan. Dev. 2020, 146, 4020046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, X.; Shen, G.Q.; Guo, L. Optimizing incentive policy of energy-efficiency retrofit in public buildings: A principal-agent model. Sustainability 2019, 11, 3442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, G.; Wei, L.; Gu, J.; Zhou, T.; Liu, Y. Benefit distribution in urban renewal from the perspectives of efficiency and fairness: A game theoretical model and the government’s role in China. Cities 2020, 96, 102422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samsura, D.A.A.; van der Krabben, E.; van Deemen, A.M.A. A game theory approach to the analysis of land and property development processes. Land Use Policy 2010, 27, 564–578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, L.; Dzeng, R.J.; Hao, S.; Zhang, C.; Zhang, S.; Tang, L. Exploring Stakeholders in Elderly Community Retrofit Projects: A Tripartite Evolutionary Game Analysis. Sustainability 2024, 16, 8016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Liu, J.; Zheng, Y. Evolutionary game analysis of community elderly care service regulation in the context of “Internet+”. Front. Public Health 2022, 10, 1093451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Z.; Song, X.; Shi, Y. Evolutionary game analysis of behavior strategies of multiple stakeholders in an elderly care service system. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 4263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gao, Y.; Zhu, Z.; Yang, J. An evolutionary game analysis of stakeholders’ decision-making behavior in medical data sharing. Mathematics 2023, 11, 2921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Zhang, X.; Han, Y.; Yu, B.; Liu, H. Evolutionary game model of health care and social care collaborative services for the elderly population in China. BMC Geriatr. 2022, 22, 616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Wang, X. Game analysis of social capital violations and government regulation in public–private partnership risk sharing. Syst. Eng. 2023, 26, 305–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.; Yao, P. Study on the evolutionary game of the three parties in the combined medical and health-care PPP project. Front. Public Health 2023, 11, 1072354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Liu, J.; Zheng, Y. Evolutionary game and stability analysis of elderly care service quality supervision from the perspective of government governance. Front. Public Health 2023, 11, 1218301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, J.; Huang, C.; Li, S.; Xia, Y. Evolutionary game analysis of rural public-private partnership older adult care project in the context of population aging in China. Front. Public Health 2023, 11, 1110082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yue, X.; Durrani, S.K.; Li, R.; Liu, W.; Manzoor, S.; Anser, M.K. Evolutionary game model for the behavior of private sectors in elderly healthcare public–private partnership under the condition of information asymmetry. Bmc. Health Serv. Res. 2025, 25, 181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Yang, X.; Wang, H. Age-friendly regeneration of urban settlements in China: Game and incentives of stakeholders in decision-making. Land Use Policy 2021, 111, 105745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, H.; Guo, H.; Zhang, K.; Liu, Y. Associations between community-based integrated care services and disability trajectories of older adults: Evidence from China. Soc. Sci. Med. 2025, 382, 118387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mitchell, R.K.; Agle, B.R.; Wood, D.J. Toward a theory of stakeholder identification and salience: Defining the principle of who and what really counts. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1997, 22, 853–886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wojewnik-Filipkowska, A.; Węgrzyn, J. Understanding of Public–Private Partnership Stakeholders as a Condition of Sustainable Development. Sustainability 2019, 11, 1194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, K.; Ke, Y.; Sankaran, S. Achieving Social Sustainability in Public–Private Partnership Elderly Care Projects: A Chinese Case Study. Buildings 2025, 15, 3202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farid, H.M.A.; Iram, S.; Shakeel, H.M.; Hill, R. Enhancing stakeholder engagement in building energy performance assessment: A state-of-the-art literature survey. Energy Strateg. Rev. 2024, 56, 101560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, S.; Li, B.; Xing, Z. The governance mechanism of the building material industry (BMI) in transformation to green BMI: The perspective of green building. Sci. Total Environ. 2019, 677, 19–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rana, A.; Sadiq, R.; Alam, M.S.; Karunathilake, H.; Hewage, K. Evaluation of financial incentives for green buildings in Canadian landscape. Renew. Sust. Energy Rev. 2021, 135, 110199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Wang, Z.; Liang, W.; Yang, F.; Wu, G. Green retrofit of existing public buildings in China: A synergy mechanism of state-owned enterprises based on evolutionary game theory. J. Clean. Prod. 2024, 434, 140454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pang, J.; Sen, S.; Shanbhag, U.V. Two-stage non-cooperative games with risk-averse players. Math. Program. 2017, 165, 235–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyapunov, A.M. The general problem of the stability of motion. Int. J. Control. 1992, 55, 531–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friedman, D. Evolutionary Game in Economics. Econometrica 1991, 59, 637–666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, D.; Yang, X.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, J. Dynamic interactions of carbon reduction strategies in the shipping industry considering market cyclicality: A tripartite evolutionary game analysis. Energy 2025, 335, 137963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Liu, J. Evaluation of the excess revenue sharing ratio in PPP projects using principal–agent models. Int. J. Proj. Manag. 2015, 33, 1317–1324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, C.M.; Lee, J.H.; Yim, C.H. A revenue-sharing model of residential redevelopment projects: The case of the Hapdong redevelopment scheme in Seoul, Korea. Urban Stud. 2003, 40, 2223–2237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, J.M. The theory of games and the evolution of animal conflicts. J. Theor. Biol. 1974, 47, 209–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paquin, J.; Gauthier, C.; Morin, P. The downside risk of project portfolios: The impact of capital investment projects and the value of project efficiency and project risk management programmes. Int. J. Proj. Manag. 2016, 34, 1460–1470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, W.S.; Peng, Y.; Webster, C.; Zuo, J. Stakeholders’ willingness to pay for enhanced construction waste management: A Hong Kong study. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2015, 47, 233–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, L.; He, W.J.; Degefu, D.M.; Kong, Y.; Wu, X.; Xu, S.S.; Wan, Z.C.; Ramsey, T.S. Elucidating competing strategic behaviors using prospect theory, system dynamics, and evolutionary game: A case of transjurisdictional water pollution problem in China. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2022, 29, 20829–20843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ministry of Housing and Urban-Rural Development of the People’s Republic of China, Architectural Design Standards of Care Facilities for Elderly. 2023. Available online: http://www.szelec.cc/zb_users/upload/2023/01/202301031672721226192009.pdf (accessed on 20 July 2025).

- Central People’s Government of the People’s Republic of China. Implementation Guidelines for National Standards for the Classification and Evaluation of Elderly Care Institutions. 2023. Available online: https://www.gov.cn/lianbo/bumen/202307/content_6890935.htm (accessed on 2 December 2025).

- Wang, S.; Cao, M.; Chen, X. Optimally combined incentive for cooperation among interacting agents in population games. IEEE Trans. Automat. Contr. 2025, 70, 4562–4577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gazheli, A.; Antal, M.; van den Bergh, J. The behavioral basis of policies fostering long-run transitions: Stakeholders, limited rationality and social context. Futures 2015, 69, 14–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goswami, A.; Parashari, G.S.; Gupta, R. Evolutionary stability of reputation-based incentive mechanisms in p2p systems. IEEE Commun. Lett. 2017, 22, 268–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, Q.; Liu, Y.; Li, Z.; Wu, C. Dynamic reward and penalty strategies of green building construction incentive: An evolutionary game theory-based analysis. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2021, 28, 44902–44915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Habermacher, F.; Lehmann, P. Commitment versus discretion in climate and energy policy. Environ. and Resour. Econ. 2020, 76, 39–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.; Lian, Y.; Zhao, H.; Xia-Bauer, C. Unlocking green financing for building energy retrofit: A survey in the western China. Energy Strateg. Rev. 2020, 30, 100520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williamson, O.E. The economics of governance. Am. Econ. Rev. 2005, 95, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grossman, S.J.; Hart, O.D. The costs and benefits of ownership: A theory of vertical and lateral integration. J. Polit. Econ. 1986, 94, 691–719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moradi, S.; Hirvonen, J.; Sormunen, P. A qualitative and life cycle-based study of the energy performance gap in building construction: Perspectives of finish project professionals and property maintenance experts. Build. Res. Inf. 2024, 52, 564–576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, J.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Chen, L. Strategic interaction among stakeholders on low-carbon buildings: A tripartite evolutionary game based on prospect theory. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2024, 31, 11096–11114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hertin, J.; Berkhout, F.; Gann, D.; Barlow, J. Climate change and the UK house building sector: Perceptions, impacts and adaptive capacity. Build. Res. Inf. 2003, 31, 278–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piñeiro, V.; Arias, J.; Dürr, J.; Elverdin, P.; Ibáñez, A.M.; Kinengyere, A.; Opazo, C.M.; Owoo, N.; Page, J.R.; Prager, S.D.; et al. A scoping review on incentives for adoption of sustainable agricultural practices and their outcomes. Nat. Sustain. 2020, 3, 809–820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lie-Panis, J.; Fitouchi, L.; Baumard, N.; André, J. The social leverage effect: Institutions transform weak reputation effects into strong incentives for cooperation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2024, 121, e1886165175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Stakeholders | Power | Legitimacy | Urgency |

|---|---|---|---|

| Investors | High | High | High |

| Builders | High | High | High |

| Operators | High | High | High |

| Governments | High | High | Low |

| End users | Low | High | High |

| Parameters | Descriptions | Range of Values |

|---|---|---|

| C11 | Base cost under passive regulation | ≥0 |

| C12 | Additional cost incurred under active regulation | ≥0 |

| C21 | Base cost of implementing a low-quality retrofit | ≥0 |

| C22 | Additional cost required for a high-quality retrofit | ≥0 |

| C31 | Base cost of providing low-quality service | ≥0 |

| C32 | Additional cost required for high-quality service | ≥0 |

| R1 | Investors’ benefits when builders and operators adopt high-quality strategies | ≥0 |

| R21 | Revenue obtained from a low-quality retrofit | ≥0 |

| R22 | Revenue obtained from a high-quality retrofit | ≥0 |

| R31 | Revenue obtained from low-quality service | ≥0 |

| R32 | Revenue obtained from high-quality service | ≥0 |

| F1 | Penalty imposed by the investors for low-quality retrofit | [35% × R22, 50% × R22] |

| F2 | Penalty imposed by the investors for low-quality service | [40% × R32, 50% × R32] |

| K | Investors’ responsibility costs under passive regulation when project losses occur [39] | ≥0 |

| Q | Social and environmental benefits generated by the project | Fixed value |

| P | Policy benefits generated by policy preference, P = θQ | ≥0 |

| S | Accumulated brand benefits from the project [41] | ≥0 |

| α | Investors’ penalty intensity for low-quality behavior by builders and operators [40] | [0, 1] |

| β | The strength of economic incentives from investors for promoting high-quality practices by builders and operators [18] | [0, 1] |

| γ | The strength of reputational incentives from investors when builders and operators adopt high-quality behavior [42] | [0, 1] |

| θ | The investors’ policy preference [18] | [0, 1] |

| δ | Quality evaluation coefficient reflecting the effectiveness of the builders’ retrofit | [0.6, 1] |

| μ | Matching the coefficient between market demand and service supply | [0.6, 1] |

| I0 | Total project investment | >0 |

| R | Total economic benefits, R = 0.2 I0 | >0 |

| n | Number of successfully completed projects | [0, 20] |

| Builders | Operators | Investors | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Active Regulation (x) | Passive Regulation (1 − x) | ||

| High-quality retrofit (y) | High-quality service (z) | −C11 − C12 + R1 + S + θQ | −C11 + R1 + S |

| −C21 − C22 + (1 + γ)(βR22 + θQ) | −C21 − C22 + R22 | ||

| −C31 − C32 + (1 + γ)(βR32 + θQ) | −C31 − C32 + R32 | ||

| Low-quality service (1 − z) | −C11 − C12 + S | −C11 − K | |

| −C21 − C22 + δ(1 + β)R22 | −C21 − C22 + ΔR22 | ||

| −C31 + R31 − αF2 | −C31 + R31 − αF2 | ||

| Low-quality retrofit (1 − y) | High-quality service (z) | −C11 − C12 + S | −C11 − K |

| −C21 + R21 − αF1 | −C21 + R21 − αF1 | ||

| −C31 − C32 + μ(1 + β)R32 | −C31 − C32 + μR32 | ||

| Low-quality service (1 − z) | −C11 − C12 | −C11 − K | |

| −C21 + R21 − αF1 | −C21 + R21 − αF1 | ||

| −C31 + R31 − αF2 | −C31 + R31 − αF2 | ||

| Equilibrium Points | Eigenvalues | Eigenvalue Sign | Stability | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| λ1 | λ2 | λ3 | |||

| E1(1,1,1) | C12 − θQ | −ΔB | −ΔO | −, −, − | ESS |

| E2(1,1,0) | C12 – S − K | ΔO | ×, +, + | Saddle point/Unstable point | |

| E3(1,0,1) | C12 − S − K | ΔB | ×, +, + | Saddle point/Unstable point | |

| E4(1,0,0) | C12 − K | ×, −, − | ESS/Saddle point | ||

| E5(0,1,1) | −C12 + θQ | +, ×, × | Saddle point/Unstable point | ||

| E6(0,1,0) | −C12 + S + K | ×, +, × | Saddle point/Unstable point | ||

| E7(0,0,1) | −C12 + S + K | ×, ×, + | Saddle point/Unstable point | ||

| E8(0,0,0) | K − C12 | ×, −, − | ESS/Saddle point | ||

| Agents | Parameters | Range | Initial Value | Source |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Investors | C11 | - | 16 | Case data |

| C12 | 2% × I0 | 16 | Case data | |

| R1 | 20% × R | 32 | Case data | |

| θ | [0, 1] | 0.5 | [18] | |

| P | θQ | 40 | Case data | |

| K | 50% × θQ | 12 | [39] | |

| n | [0, 20] | 10 | Case data | |

| S | nQ × 1% | 8 | [41] | |

| Builders | C21 | - | 16 | Case data |

| C22 | 3.5% × I0 | 28 | Case data | |

| R21 | - | 20 | Case data | |

| R22 | 30% × R | 48 | Case data | |

| F1 | [35% × R22, 50% × R22] | 16.8 | Case data | |

| δ0 | [0.6, 1] | 0.6 | Policy document | |

| Operators | C31 | - | 16 | Case data |

| C32 | 3% × I0 | 24 | Case data | |

| R31 | - | 50 | Case data | |

| R32 | 50% × R | 80 | Case data | |

| F2 | [40% × R32, 50% × R32] | 32 | Case data | |

| μ | [0.6, 1] | 0.6 | Policy document | |

| Global | α | [0, 1] | 0.2 | [40] |

| β | [0, 1] | 0.3 | [18] | |

| γ | [0, 1] | 0.3 | [42] | |

| Q | Fixed value | 80 | Case data | |

| R | Fixed value | 160 | Case data |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Yin, X.; Yuan, D.; Wang, S.; He, J.; Wang, X. An Evolutionary Game-Based Governance Mechanism for Sustainable Medical and Elderly Care Building Retrofits in Urban Renewal. Buildings 2026, 16, 138. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings16010138

Yin X, Yuan D, Wang S, He J, Wang X. An Evolutionary Game-Based Governance Mechanism for Sustainable Medical and Elderly Care Building Retrofits in Urban Renewal. Buildings. 2026; 16(1):138. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings16010138

Chicago/Turabian StyleYin, Xiangyan, Dongliang Yuan, Shuren Wang, Jun He, and Xinyu Wang. 2026. "An Evolutionary Game-Based Governance Mechanism for Sustainable Medical and Elderly Care Building Retrofits in Urban Renewal" Buildings 16, no. 1: 138. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings16010138

APA StyleYin, X., Yuan, D., Wang, S., He, J., & Wang, X. (2026). An Evolutionary Game-Based Governance Mechanism for Sustainable Medical and Elderly Care Building Retrofits in Urban Renewal. Buildings, 16(1), 138. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings16010138