Performance Comparison of STPV and Split Louvers in Hot Arid Climates

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Semi-Transparent Photovoltaic System

2.2. Split Louver System

2.3. Summary of Related STPV and Split Louver System Works

3. STPV and Split Louver Bibliometric Overview

4. Research Gap

- Compares the two technologies on equal boundary conditions and climatic inputs.

- Quantifies the outcomes on thermal comfort, climate-based daylight modeling and glare, and overall energy use.

- Synthesizes results in design protocols that encourage the development and implementation of climate-responsive and scalable façade concepts for sustainable building practice in hot climates.

5. Materials and Methods

5.1. Study Location and Climatic Conditions

5.2. Model Office Description

5.3. Proposed Façade Configurations

5.4. Modeling Approach and Metrics

5.4.1. Daylighting Performance Simulation

5.4.2. STPV Energy Output Simulation

5.4.3. Thermal Comfort Modeling

5.4.4. Overall Energy Performance Modeling

6. Results

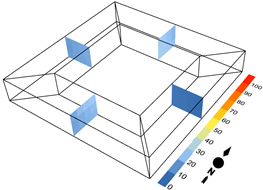

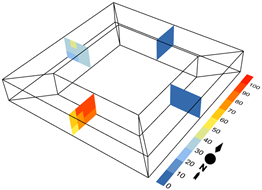

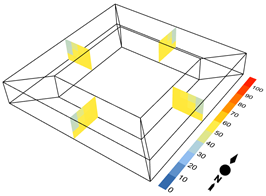

6.1. Daylighting Quantity and Quality Analysis

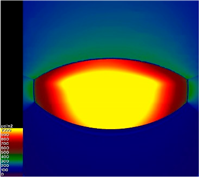

6.2. Thermal Analysis of Selected Efficient Façade Configurations

- The base model failed to maintain adaptive features that are necessary to give an efficient response to different and dynamic climate conditions. In summer, particularly during the solstice period of summer, it has trouble overheating beyond what is considered appropriate for adaptive thermal comfort. The interior of the building is subjected to high operative temperatures and does not meet the 80% comfort threshold. Likewise, in the winter solstice period, when passive solar gain is not well-regulated, the model favors mechanical heating to achieve thermal comfort except when the south wall meets ATC. In general, this design strategy does not fully achieve comfortable conditions 24/7, and the importance of an advanced façade with certain levels of control is confirmed.

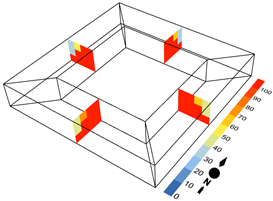

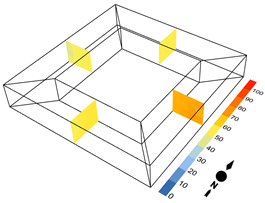

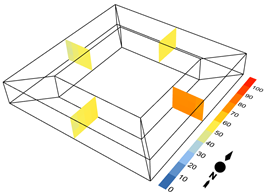

- Configurations 9 and 15 (split louvers and 15 to 20 cm slat depth) are distinctly better in terms of adaptive thermal comfort than the reference model, yearly, and especially during the summer solstice. During the summer solstice, this configuration excels in solar heat gain control, significantly reducing cooling loads. This design effectively regulates solar heat gains and significantly lowers cooling loads throughout the solstice summer. Without lowering thermal comfort, the slats with a 10 cm pitch and 45° angle can block incident solar radiation, which is advantageous for indoor daylighting (as demonstrated in the previous section). The building stays within the 80% comfort criterion owing to the summertime drop in operating temperature, which reduces the need for artificial cooling systems. The system, on the other hand, lowers passive solar gain during the winter solstice, which considerably lowers the inside temperature and increases the need for heating. With an average result of about 50% ATC, this imbalance between heating and cooling performance preserves year-round comfort and offers the best option for both warm areas, where hot days throughout the year predominate.

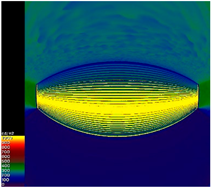

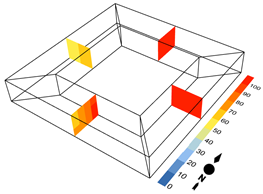

- This model, the STPV 10% and 20%, is a further development of solar energy conversion and thermal comfort. Excellent performance with respect to heat gain during the solstice summer is provided, with 90% of solar radiation being restricted from entering the façade. The low SHGC and high insulative U-value of both the chosen STPV means that direct solar heat is mostly deflected. Such STPV layouts indicate to be very promising for ATC in warm climates with a high cooling efficiency. However, in the winter solstice (Table 7), due to its low SHGC, the STPV 10% configuration restrains passive solar gain and leads to a higher need for mechanical heating. Even though the performance of both STPV 10% and 20% systems is almost identical, an enhancement was observed in the eastern office zone during the winter solstice season.

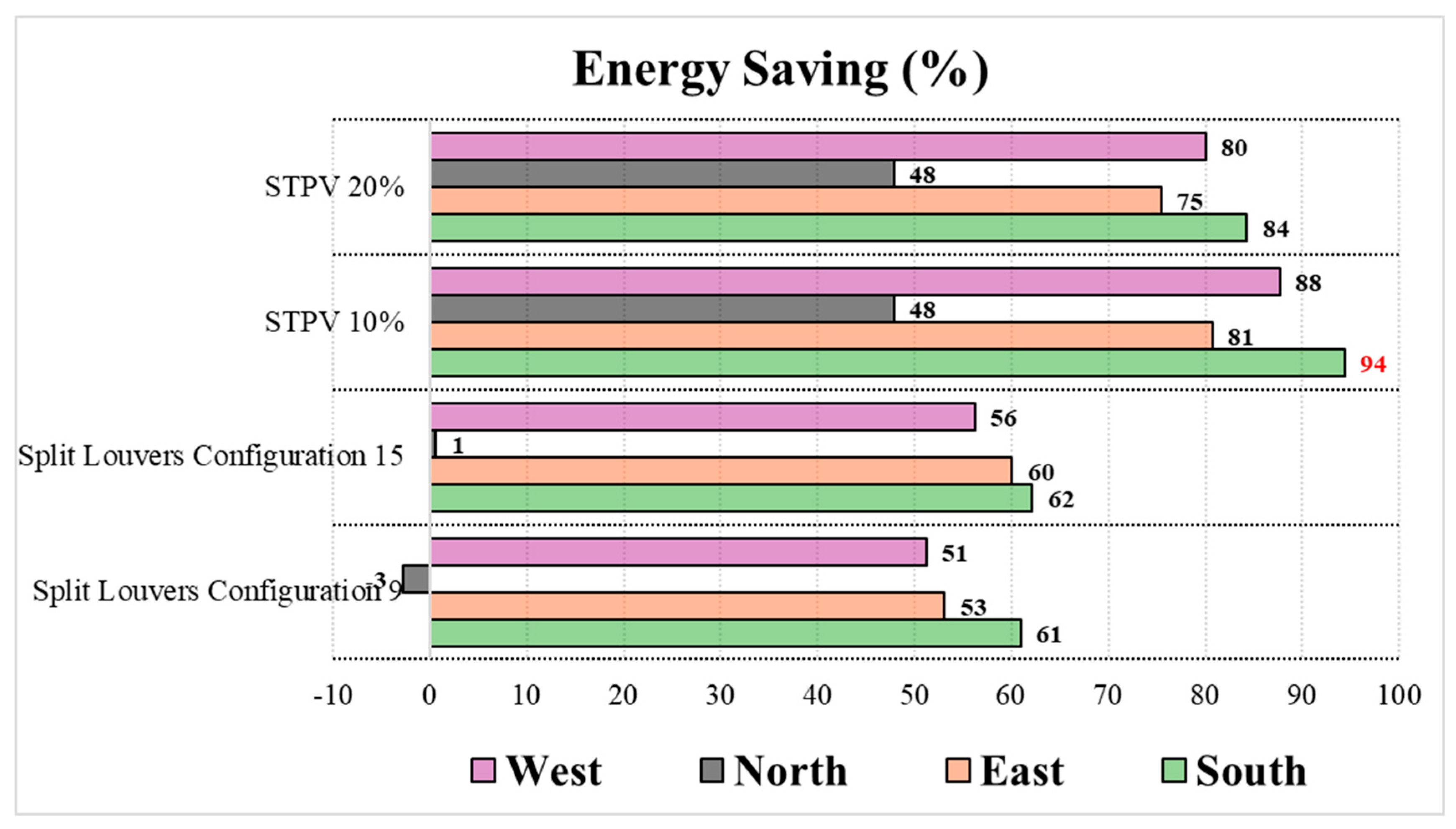

6.3. Energy Analysis of Selected Efficient Façade Configurations

7. Discussion

8. Conclusions

- ▪

- STPV glazing (10–20 VLT) is the only solution sufficiently resilient and superior across performance dimensions in a trio, managing substantial power output that balances the cooling and lighting load; effective annual reduction in solar gain; and accommodation of adequate dynamic daylighting without glare. This dual role offers whole-façade energy savings of 81–94% compared to passive-only alternatives.

- ▪

- Under certain restrictions, the optimal split louver configurations can offer excellent glare management. Parametrically adjusted louvers (15–20 cm depth, 10 cm separation, 45° tilt) minimize peak solar loads and attain near-imperceptible DGP values (DGP ≈ 0.28–0.39) but are less effective than low-transmissivity STPV for removing glare. They preserve, nevertheless, an adequate quality of indoor daylighting and provide good control of solar gains with marked loads in lighting energy consumption (429–530 kWh with respect to 113 kWh for SPV 10%).

- ▪

- On the thermal comfort side, seasonality is asymmetric in both systems: both can adequately achieve control of PMV between −0.5 and +0.5, but winter comfort starts to drop as solar entry becomes over-constrained (and PMV drops to −2), justifying an orientation-informed tuning and hybrid HVAC strategy to counteract the solstice-period under-heating.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| a-Si | Amorphous Silicon |

| ASHRAE | American Society of Heating, Refrigerating, and Air-Conditioning Engineers |

| ATC | Adaptive Thermal Comfort |

| BIPV-DSF | Building Integrated Photovoltaic–Double-Skin Façade |

| CCR | Cell Coverage Ratio |

| CdTe | Cadmium Telluride |

| CIE | International Commission on Illumination |

| DA | Daylight Autonomy |

| DGP | Daylight Glare Probability |

| HVAC | Heating, Ventilation, Air-Conditioning |

| MRT | Mean Radiant Temperature |

| OEC | Overall Energy Consumption |

| PMV | Predicted Mean Vote |

| PV | Photovoltaic |

| SHGC | Solar Heat Gain Coefficient |

| STPV | Semi-Transparent Photovoltaic |

| UDI | Useful Daylight Illuminance |

| UHI | Urban Hear Island |

| VLT | Visible Light Transmittance |

| WPI | Workplane Illuminance |

| WWR | Wall-to-Window Ratio |

References

- Ihara, T.; Gustavsen, A.; Jelle, B.P. Effect of facade components on energy efficiency in office buildings. Appl. Energy 2015, 158, 422–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dabous, S.A.; Ibrahim, T.; Shareef, S.; Mushtaha, E.; Alsyouf, I. Sustainable façade cladding selection for buildings in hot climates based on thermal performance and energy consumption. Results Eng. 2022, 16, 100643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shan, R.; Junghans, L. Multi-objective optimization for high-performance building facade design: A systematic literature review. Sustainability 2023, 15, 15596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghosh, A.; Hafnaoui, R.; Mesloub, A.; Elkhayat, K.; Albaqawy, G.; Alnaim, M.M.; Mayhoub, M. Active smart switchable glazing for smart city: A review. J. Build. Eng. 2024, 84, 108644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghosh, A.; Mesloub, A.; Touahmia, M.; Ajmi, M. Visual comfort analysis of semi-transparent perovskite based building integrated photovoltaic window for hot desert climate (Riyadh, Saudi Arabia). Energies 2021, 14, 1043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alsukkar, M.; Hu, M.; Gadi, M.; Su, Y. A study on daylighting performance of split louver with simplified parametric control. Buildings 2022, 12, 594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Dakheel, J.; Tabet Aoul, K. Building Applications, opportunities and challenges of active shading systems: A state-of-the-art review. Energies 2017, 10, 1672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalwry, H.; Atakara, C. Exploring Energy-Efficient Design Strategies in High-Rise Building Façades for Sustainable Development and Energy Consumption. Buildings 2025, 15, 1062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yaman, M. Different facade types and building integration in energy efficient building design strategies. Int. J. Built Environ. Sustain. 2021, 8, 49–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carlucci, F. A Review of Smart and Responsive Building Technologies and their Classifications. Future Cities Environ. 2021, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hafnaoui, R.; zin Kandar, M.; Ghosh, A.; Mesloub, A. Smart switchable glazing systems in Saudi Arabia: A review. Energy Build. 2024, 319, 114555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mesloub, A.; Alnaim, M.M.; Albaqawy, G.; Elkhayat, K.; Hafnaoui, R.; Ghosh, A.; Mayhoub, M.S. The Daylighting Optimization of Integrated Suspended Particle Devices Glazing in Different School Typologies. Buildings 2024, 14, 2574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mesloub, A.; Albaqawy, G.A.; Kandar, M.Z. The optimum performance of building integrated photovoltaic (BIPV) windows under a semi-arid climate in Algerian office buildings. Sustainability 2020, 12, 1654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alkahtani, M.; Hu, Y.; Alghaseb, M.A.; Elkhayat, K.; Kuka, C.S.; Abdelhafez, M.H.; Mesloub, A. Investigating fourteen countries to maximum the economy benefit by using offline reconfiguration for medium scale pv array arrangements. Energies 2020, 14, 59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mesloub, A.; Ghosh, A. Daylighting performance of light shelf photovoltaics (LSPV) for office buildings in hot desert-like regions. Appl. Sci. 2020, 10, 7959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mesloub, A.; Ghosh, A.; Albaqawy, G.A.; Noaime, E.; Alsolami, B.M. Energy and Daylighting Evaluation of Integrated Semitransparent Photovoltaic Windows with Internal Light Shelves in Open-Office Buildings. Adv. Civ. Eng. 2020, 2020, 8867558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mesloub, A.; Ghosh, A.; Touahmia, M.; Albaqawy, G.A.; Noaime, E.; Alsolami, B.M. Performance analysis of photovoltaic integrated shading devices (PVSDs) and semi-transparent photovoltaic (STPV) devices retrofitted to a prototype office building in a hot desert climate. Sustainability 2020, 12, 10145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alrashidi, H.; Issa, W.; Sellami, N.; Ghosh, A.; Mallick, T.K.; Sundaram, S. Performance assessment of cadmium telluride-based semi-transparent glazing for power saving in façade buildings. Energy Build. 2020, 215, 109585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.; Zhang, L.; Liu, Z.; Wu, Z. Coupled optical-electrical-thermal analysis of a semi-transparent photovoltaic glazing façade under building shadow. Appl. Energy 2021, 292, 116884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, C.; Yang, H. Investigation on the overall energy performance of a novel vacuum semi-transparent photovoltaic glazing in cold regions of China. In Proceedings of the Applied Energy Symposium, Boston, MA, USA, 22–24 May 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Setyantho, G.R.; Park, H.; Chang, S. Multi-criteria performance assessment for semi-transparent photovoltaic windows in different climate contexts. Sustainability 2021, 13, 2198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Yang, H.; Xiang, C. The overall performance of a novel semi-transparent photovoltaic window with passive radiative cooling coating–A comparative study. Energy Build. 2024, 317, 114433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghasaban, M.; Yeganeh, M.; Irani, M. Optimizing daylight, sky view and energy production in semi-transparent photovoltaic facades of office buildings: A comparative study in four climate zones. Appl. Energy 2025, 377, 124707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alsukkar, M.; Hu, M.; Eltaweel, A.; Su, Y. Daylighting performance improvements using of split louver with parametrically incremental slat angle control. Energy Build. 2022, 274, 112444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibrahim, A.; Alsukkar, M.; Dong, Y.; Hu, P. Improvements in energy savings and daylighting using trapezoid profile louver shading devices. Energy Build. 2024, 321, 114649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bagheri Sabzevar, H.; Erfan, Z. Effect of fixed louver shading devices on thermal efficiency. Iran. J. Energy Environ. 2021, 12, 349–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alsukkar, M.; Hu, M.; Alkhater, M.; Su, Y. Daylighting performance assessment of a split louver with parametrically incremental slat angles: Effect of slat shapes and PV glass transmittance. Sol. Energy 2023, 264, 112069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rafati, N.; Hazbei, M.; Eicker, U. Louver configuration comparison in three Canadian cities utilizing NSGA-II. Build. Environ. 2023, 229, 109939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, S.; Cannavale, A.; Prasad, D.; Sproul, A.; Fiorito, F. Numerical simulation study of BIPV/T double-skin facade for various climate zones in Australia: Effects on indoor thermal comfort. In Building Simulation; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Ioannidis, Z.; Rounis, E.-D.; Athienitis, A.; Stathopoulos, T. Double skin façade integrating semi-transparent photovoltaics: Experimental study on forced convection and heat recovery. Appl. Energy 2020, 278, 115647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kapsis, K.; Dermardiros, V.; Athienitis, A. Daylight performance of perimeter office façades utilizing semi-transparent photovoltaic windows: A simulation study. Energy Procedia 2015, 78, 334–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khele, I.; Szabo, M. A review of the effect of semi-transparent building-integrated photovoltaics on the visual comfort indoors. Dev. Built Environ. 2024, 17, 100369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Utaberta, N.; Seghier, T.E. Optimal Semi-Transparent Photovoltaic (STPV) window based on energy performance, daylighting quality, and occupant satisfaction–A case study of private office in Chengdu China. Energy Build. 2024, 319, 114502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaaliche, N.; Alsatrawi, H. Performance investigation of novel semitransparent buildings with integrated photovoltaic windows based on fluid-thermal-electric numerical model in the Persian Gulf region. J. Therm. Anal. Calorim. 2023, 148, 9063–9077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hazarika, P.; Shyam; Kalita, P.; Gaur, A. Annual Energy Analysis of a Building-Integrated Semitransparent Photovoltaic Thermal Façade. J. Sol. Energy Eng. 2025, 147, 034501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, Y.; Gao, M.; Dong, J.; Jia, J.; Zhao, X.; Li, G. Investigation on the daylight and overall energy performance of semi-transparent photovoltaic facades in cold climatic regions of China. Appl. Energy 2018, 232, 517–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roberts, F.; Yang, S.; Du, H.; Yang, R. Effect of semi-transparent a-Si PV glazing within double-skin façades on visual and energy performances under the UK climate condition. Renew. Energy 2023, 207, 601–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, J.; Tao, Q. Impact of shading louvers on wind-driven single-sided ventilation in a multi-storey building. In E3S Web of Conferences; EDP Sciences: Les Ulis, France, 2022; Volume 356, p. 03061. [Google Scholar]

- World Bank Group. Climate Change Knowledge Portal, Climatology in Saudi Arabia. 2021. Available online: https://climateknowledgeportal.worldbank.org/country/saudi-arabia/climate-data-historical (accessed on 1 November 2025).

- Mesloub, A.; Hafnaoui, R.; Abdelhafez, M.H.H.; Seghier, T.E.; Kolsi, L.; Ali, N.B.; Ghosh, A. Multi-objective optimization of switchable suspended particle device vacuum glazing for comfort and energy efficiency in school typologies under hot climate. Case Stud. Therm. Eng. 2024, 61, 105039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Authors and Year | Objective | Climatic Zone/Country | Variables | Main Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| H. Alrashidi et al., 2020 [18] | Investigate energy energy-saving potential of CdTe-STPV in façade buildings | Hot climates | Orientation, Transparency of STPV | Energy saving up to 20%. Trade-off between energy saving and comfort (more artificial light required for low transparency). |

| Jing Wu et al., 2021 [19] | Evaluate performance of STPV under building shadow | Changsha, China | Eave shadow width, Energy generation | Shadow loss of 15.3% in energy generation and reduction in heat gain by 3.28%. |

| Changyu Qiu & Hongxing Yang, 2019 [20] | Investigate vacuum STPV performance in cold regions of China | Harbin, China | Configuration of vacuum PV, Seasonal variations | Vacuum PV glazing improves thermal performance in winter, with 20% higher energy savings. |

| Siliang Yang et al., 2018 [29] | Study effects of BIPV/T double-skin façade on thermal comfort in Australia | Various Australian climates | VLT, operational modes, ventilation | Lower VLT (27%) provided better thermal comfort in hot climates. BIPV/T-DSF maintained indoor comfort without mechanical systems in cool climates. |

| G. R. Setyantho et al., 2021 [21] | Evaluate multi-criteria performance of STPV windows | Mediterranean climate | STPV module types, WWR, window orientations | STPV windows in Mediterranean climate showed higher efficiency (elBI). Lighting consumption is critical for module type selection. |

| Z. Ioannidis et al., 2020 [30] | Study DSF integrating STPV for heat recovery and energy performance | Experimental (outdoor) | Solar radiation, wind speed, convection | Heat recovery index > 30% and total solar utilization efficiency is 30–77%. |

| Konstantinos Kapsis et al., 2015 [31] | Assess daylight performance of STPV in office façades | Various international locations | VLT, Façade configurations | STPV system with 30% transmittance provides sufficient daylight with minimal glare. |

| Issam Khele & Márta Szabó, 2024 [32] | Review impact of STPV on indoor visual comfort and energy efficiency | Global (no specific country) | GHI, window transparency | STPV system reduces indoor illuminance but improves visual comfort and reduces glare. |

| Masoud Ghasaban et al., 2025 [23] | Optimize daylight and energy production in STPV façades | Helsinki, Toronto, Riyadh, Tebessa | Window-to-wall ratio, transparency | Optimal WWR ranged from 43 to 87%, maximizing daylight and minimizing glare. |

| Wanting Wang et al., 2024 [22] | Study CSTPV glazing with passive cooling in improving energy performance | Global (no specific country) | PV glazing, passive cooling | CSTPV reduced heat gain by 15%, improved energy efficiency by 3%, and maintained high-quality indoor lighting (CRI > 96). |

| Chen Zhan et al., 2024 [33] | Optimize CCR for STPV in Chengdu, China | Chengdu, China | CCR, occupants’ satisfaction | Optimal CCR: East 30%, west 10%, north 10%, and south 40%, based on energy, daylight, and satisfaction. |

| Nesrine Gaaliche & Hasan Alsatrawi, 2023 [34] | Investigate STPV performance in Bahrain’s subtropical climate | Bahrain (Persian Gulf region) | PV efficiency, cooling demand | Energy savings of 12% in cooling; maximum energy generation of 248.42 W. |

| Puja Hazarika et al., 2024 [35] | Evaluate BiSPVT façade in Srinagar, India | Srinagar, India | Thermal performance, energy output | Electrical efficiency 18.9%, generated 121.22 kWh/m2 of electrical energy annually. |

| Yuanda Cheng et al., 2018 [36] | Investigate daylight and energy performance of STPV façades in China | Harbin, Beijing, Wuhan, Hong Kong | Transmittance, Orientation, WWR | 43.4% energy savings in Harbin and 66% in Beijing, with additional cooling demand in moderate climates like Kunming. |

| Frank Roberts et al., 2023 [37] | Evaluating BIPV-DSF impact on visual comfort and energy consumption in UK | United Kingdom (UK) | Daylight factor, energy consumption | BIPV-DSF caused 73% drop in daylight illuminance and 8% increase in energy consumption. |

| Muna Alsukkar et al., 2022 [24] | Improve daylight distribution using split louver with parametrically controlled slats | Jordan (hot climate) | Louver slat angles, daylight distribution | Parametrically incremental slat control improved daylight uniformity (up to 0.60) and high percentage coverage (90–100% at noon). Achieved glare-free environment with UDI150–750 lx. |

| Adnan Ibrahim et al., 2024 [25] | Evaluate energy savings and daylighting with trapezoid profile louver shadings | Global (various orientations) | Louver profile, slat length, shading configurations | Energy savings of 40–44% in various orientations. UDI and DA improved significantly for trapezoid profile louvers (92.6% and 67.23%, respectively). |

| H. Bagheri Sabzevar & Z. Erfan, 2021 [26] | Study effect of fixed louver shading devices on thermal efficiency | Global (various orientations) | Louver angles, depth, distance | Reduced thermal energy consumption by 23–32%. Optimization of louver positions and angles led to improved thermal efficiency on east, south, and west façades. |

| Muna Alsukkar et al., 2023 [27] | Investigate daylighting performance of split louvers with various slat shapes | Global (various climates) | Louver slat shapes (flat, curved, oval), PV glazing | Retro-shaped slats enhanced daylight distribution, achieving UDI coverage of >90% throughout day. Uo improved to 0.70, reducing glare. |

| Jianwen Zheng & Qiu-hua Tao, 2022 [38] | Study impact of shading louvers on wind-driven ventilation in multi-storey buildings | Global (various climates) | Louver angle, airflow direction | Shading louvers improved wind-driven ventilation and air quality. Performance varied with airflow direction and louver rotation. |

| Nariman Rafati et al., 2022 [28] | Compare louver configurations for optimal shading and energy performance in Canada | Canada (various cities) | Louver depth, count, latitude | Louvers significantly improved visual comfort and energy performance. Louver depth and count were critical for optimization across different Canadian cities. |

| U-Value (W/m2K) | SHGC (%) | Transmittance VLT (%) | Peak Power (Wp/m2) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| a-Si 10% | 1.6 | 0.10 | 10 | 92 |

| a-Si 20% | 1.6 | 0.14 | 20 | 78 |

| a-Si 30% | 1.6 | 0.17 | 30 | 64 |

| Clear Double Glazing (Air) | 2.68 | 0.70 | 78 | - |

| Radiance | Ambient Bounces | Ambient Divisions | Ambient Sampling | Ambient Accuracy | Ambient Resolution |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Parameter | 6 | 4096 | 64 | 0.1 | 128 |

| Parameters | a-si 10% | a-si 20% | a-si 30% |

|---|---|---|---|

| Max power (Pmax) | 92 W | 78 W | 64 W |

| Open circuit voltage | 144 V | 144 V | 144 V |

| Short circuit current | 1.15 A | 0.97 A | 0.77 A |

| Max power voltage (Vpm) | 99 V | 99 V | 99 V |

| Max power current (Ipm) | 0.93 A | 0.79 A | 0.65 A |

| Panel surface area (m2) | 2.3 m2 | 2.3 m2 | 2.3 m2 |

| Analysis Performance Indicators | Performance Indicators | |

|---|---|---|

| Daylighting | UDI | 300 lx < Dark area (need artificial light) |

| 300 lx–1000 lx (comfortable), at least 50% of the time | ||

| >1000 lx too bright | ||

| WPI | Recommended 300 lx–1000 lx | |

| DGP | 0.35 < imperceptible glare | |

| 0.35–0.40 perceptible glare | ||

| 0.4–0.45 disturbing glare | ||

| >0.45 intolerable glare | ||

| Thermal comfort | PMV |  |

| ATC | >80% of the time | |

| Energy efficiency | OEC | Lower values indicate better performance |

| Split Louver Tilt Angle 15° | Split Louver Tilt Angle 30° | Split Louver Tilt Angle 45° | |

|---|---|---|---|

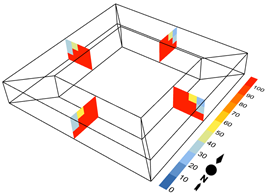

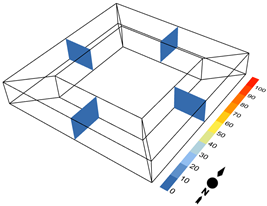

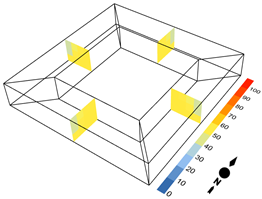

| Louver Depth =10 cm Louver Distance = 10 cm |  |  |  |

| DGP = 0.50 Intolerable Glare | DGP = 0.46 Intolerable Glare | DGP = 0.39 Perceptible Glare | |

| Louver Depth =10 cm Louver Distance = 20 cm |  |  |  |

| DGP = 0.57 Intolerable Glare | DGP = 0.55 Intolerable Glare | DGP = 0.51 Intolerable Glare | |

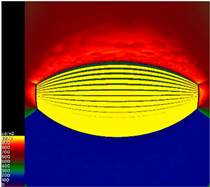

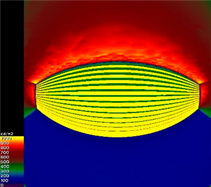

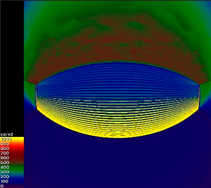

| Louver Depth =15 cm Louver Distance = 10 cm |  |  |  |

| DGP = 0.44 Disturbing Glare | DGP = 0.39 Perceptible Glare | DGP = 0.31 Imperceptible Glare | |

| Louver Depth =15 cm Louver Distance = 20 cm |  |  |  |

| DGP = 0.53 Intolerable Glare | DGP = 0.50 Intolerable Glare | DGP = 0.47 Intolerable Glare | |

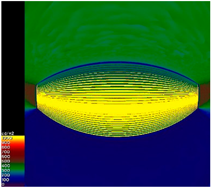

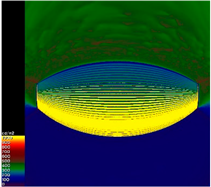

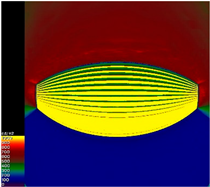

| Louver Depth =20 cm Louver Distance = 10 cm |  |  |  |

| DGP = 0.39 Perceptible Glare | DGP = 0.35 Perceptible Glare | DGP = 0.28 Imperceptible Glare | |

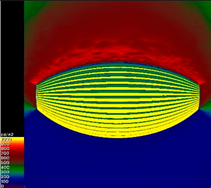

| Louver Depth =20 cm Louver Distance = 20 cm |  |  |  |

| DGP = 0.50 Intolerable Glare | DGP = 0.46 Intolerable Glare | DGP = 0.39 Perceptible Glare | |

| Transmittance (10%) Transmittance (20%) Transmittance (30%) | STPV 10% | STPV 20% | STPV 30% |

|  |  | |

| DGP = 0.21 Imperceptible Glare | DGP = 0.28 Imperceptible Glare | DGP = 0.35 Perceptible Glare |

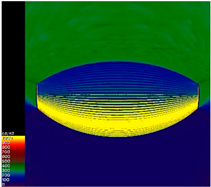

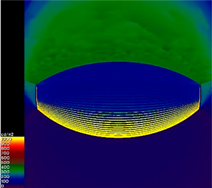

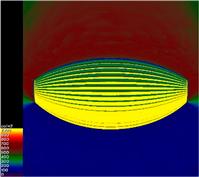

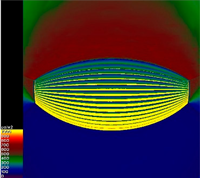

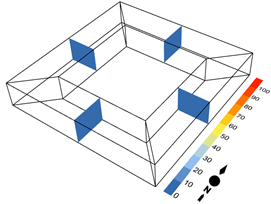

| Yearly (%) | Summer Solstice (%) | Winter Solstice (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Reference model |  |  |  |

| Configuration 09 |  |  |  |

| Configuration 15 |  |  |  |

| Configuration STPV 10% |  |  |  |

| Configuration STPV 20% |  |  |  |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Mesloub, A.; Said Mohamed, M.A.; Doulos, L.T. Performance Comparison of STPV and Split Louvers in Hot Arid Climates. Buildings 2026, 16, 117. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings16010117

Mesloub A, Said Mohamed MA, Doulos LT. Performance Comparison of STPV and Split Louvers in Hot Arid Climates. Buildings. 2026; 16(1):117. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings16010117

Chicago/Turabian StyleMesloub, Abdelhakim, Mohamed Ahmed Said Mohamed, and Lambros T. Doulos. 2026. "Performance Comparison of STPV and Split Louvers in Hot Arid Climates" Buildings 16, no. 1: 117. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings16010117

APA StyleMesloub, A., Said Mohamed, M. A., & Doulos, L. T. (2026). Performance Comparison of STPV and Split Louvers in Hot Arid Climates. Buildings, 16(1), 117. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings16010117