Visitors’ Interactions with the Exhibits and Behaviors in Museum Spaces: Insights from the National Museum of Bahrain

Abstract

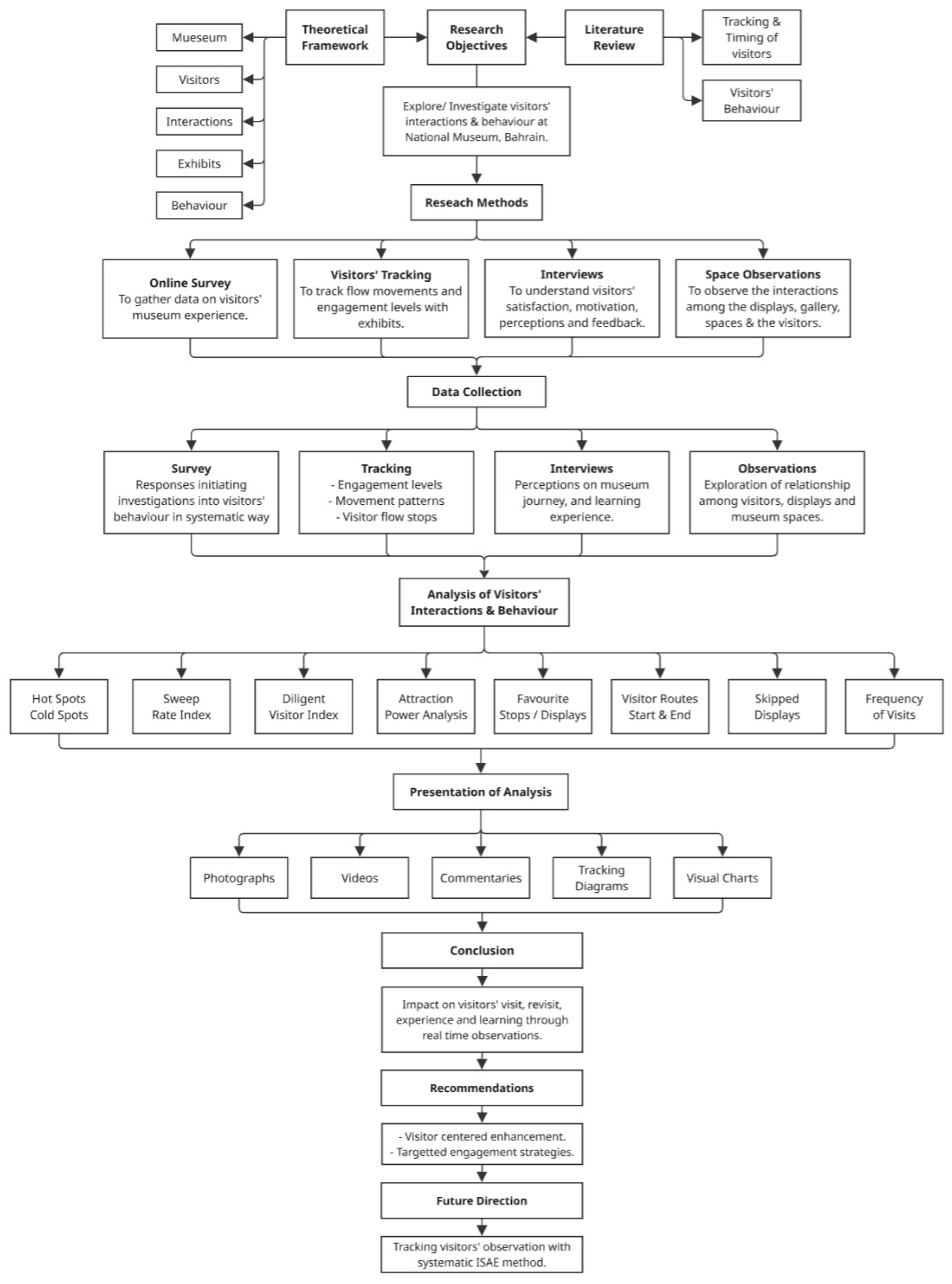

1. Introduction

- To ascertain the ways in which the visitors engage in the hall and gallery spaces at the National Museum of Bahrain.

- To identify exhibits that effectively capture visitor attention in these spaces.

- To identify the areas that experience low engagement.

- To provide actionable recommendations for the redesign of the interior and enhanced visitor experiences at the Bahrain National Museum.

2. Theoretical Framework

3. Literature Review

3.1. Visitor Behavior in Museum Spaces

3.2. Tracking and Timing of Visitors at the Museum

4. Materials and Methods

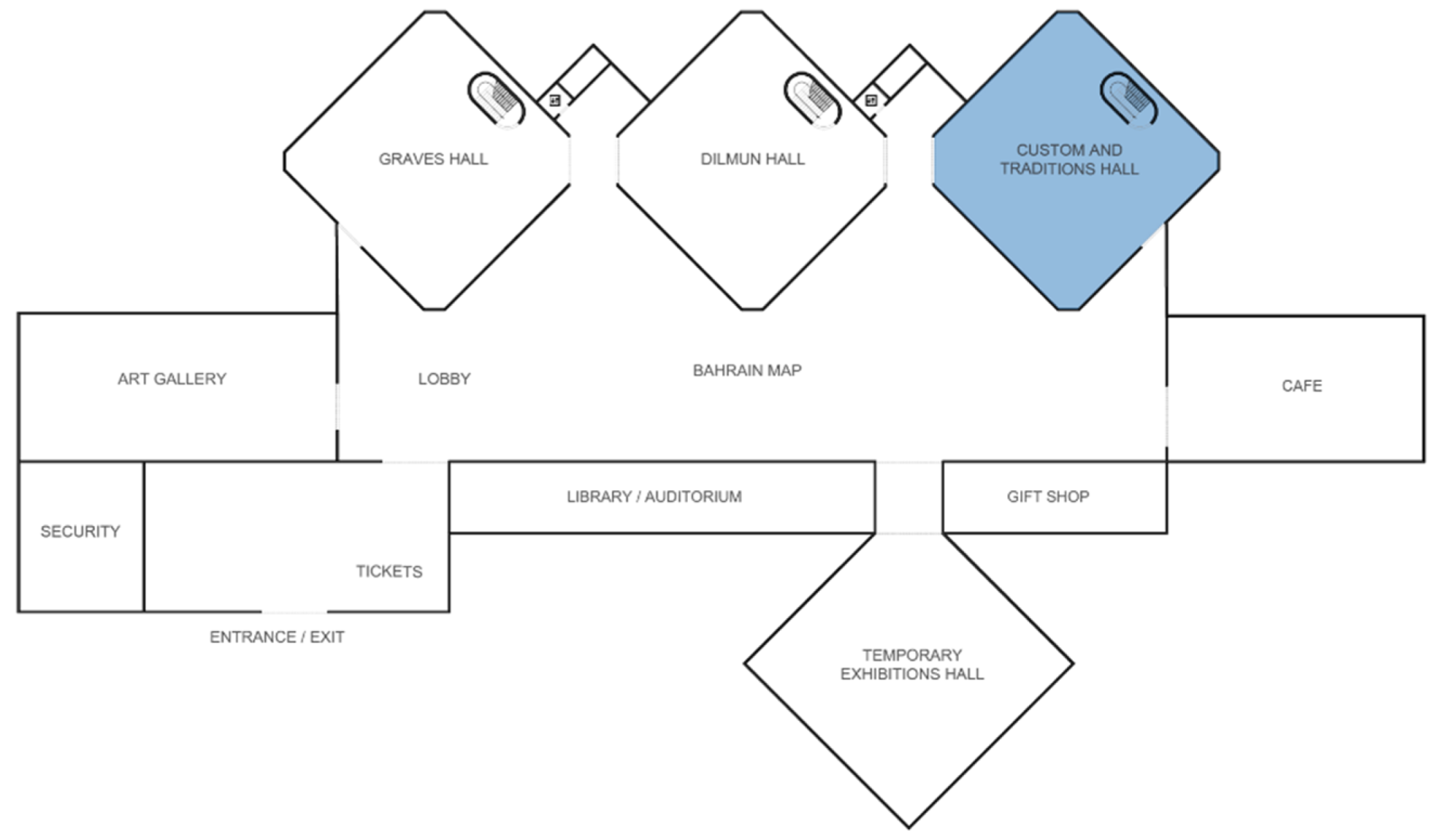

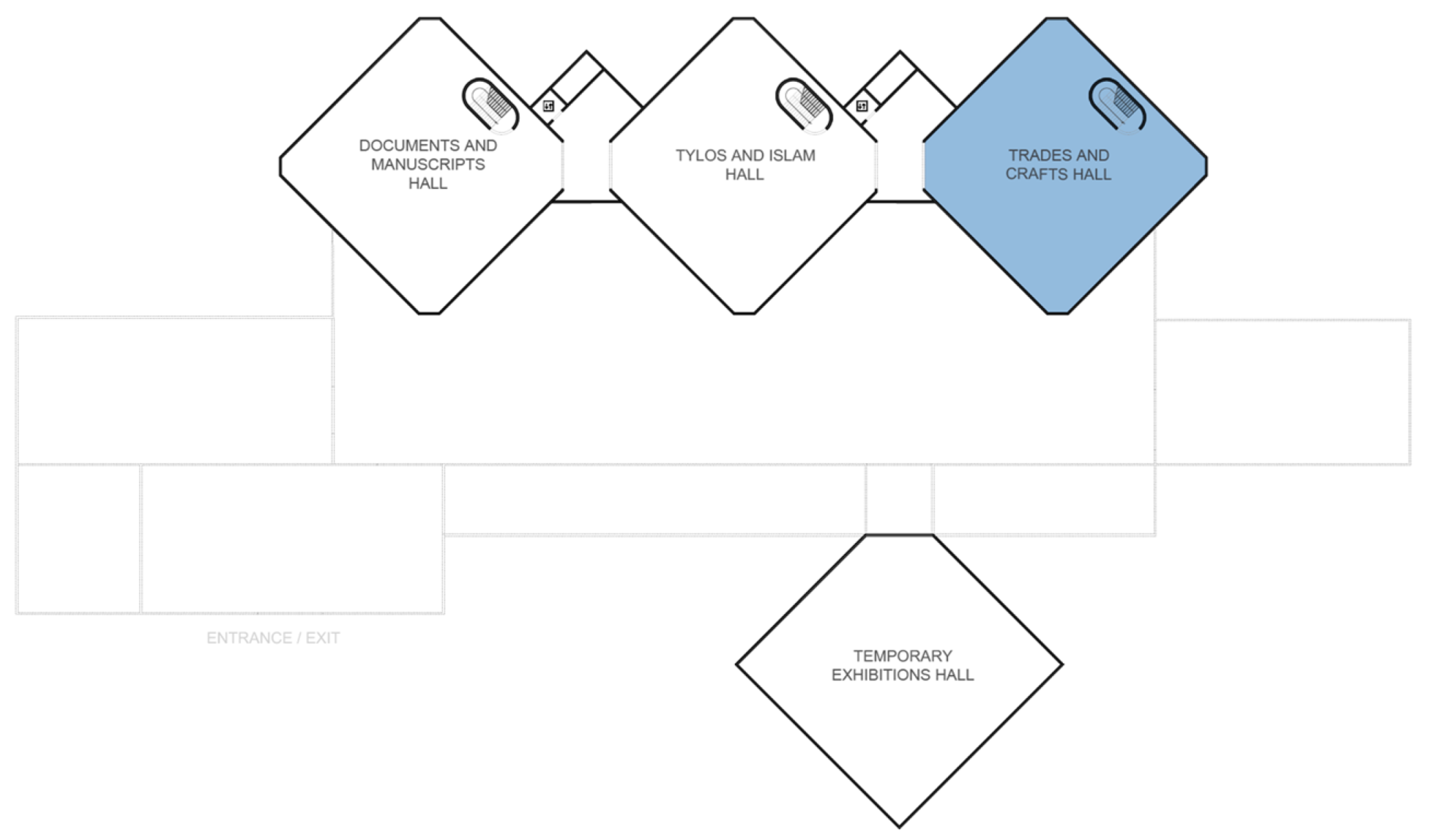

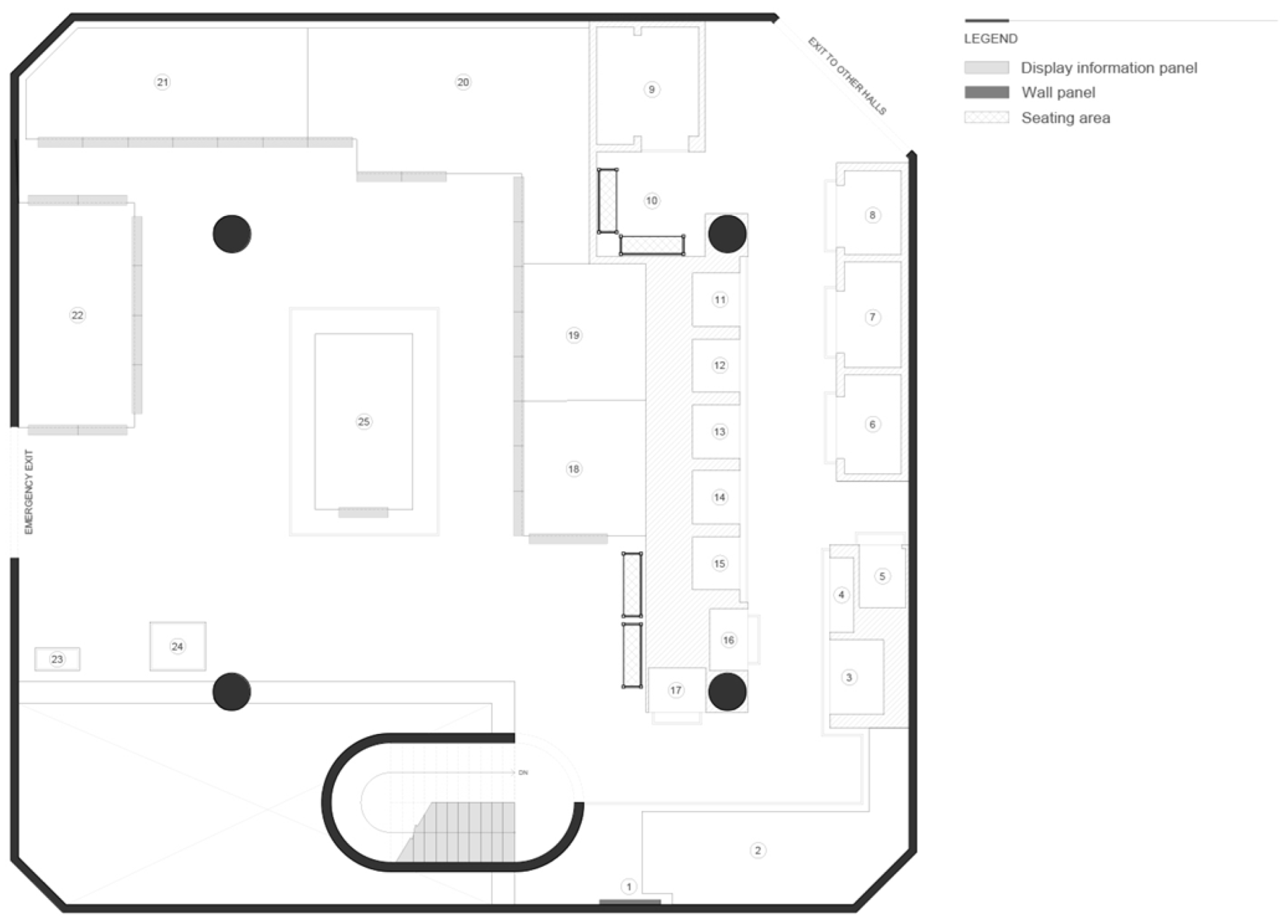

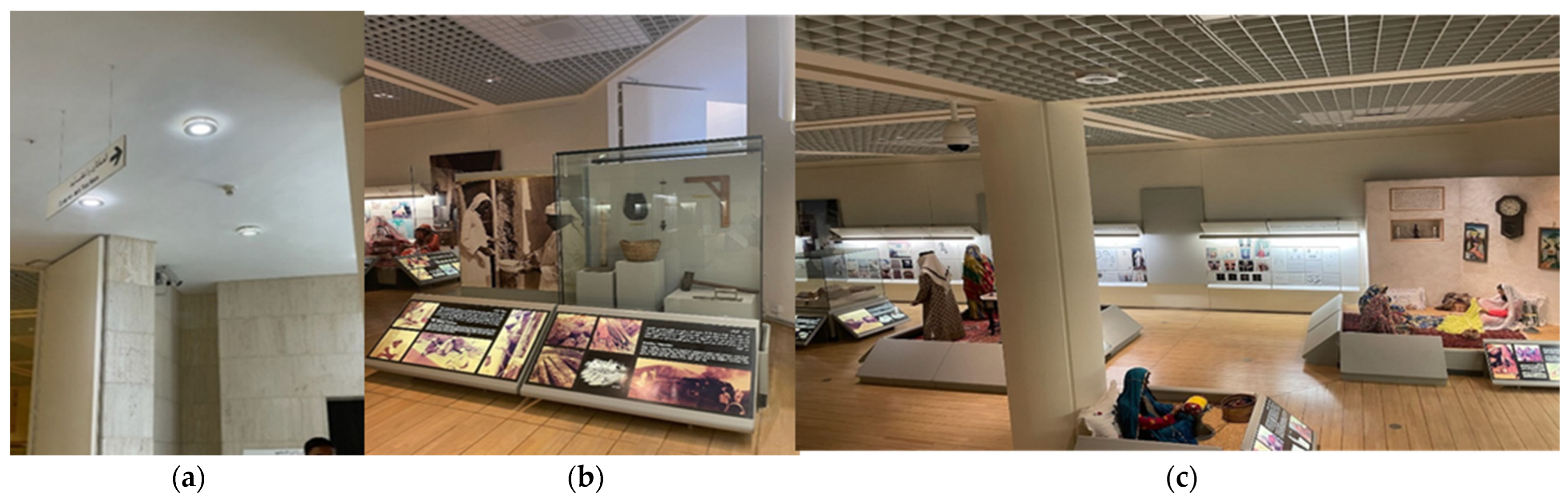

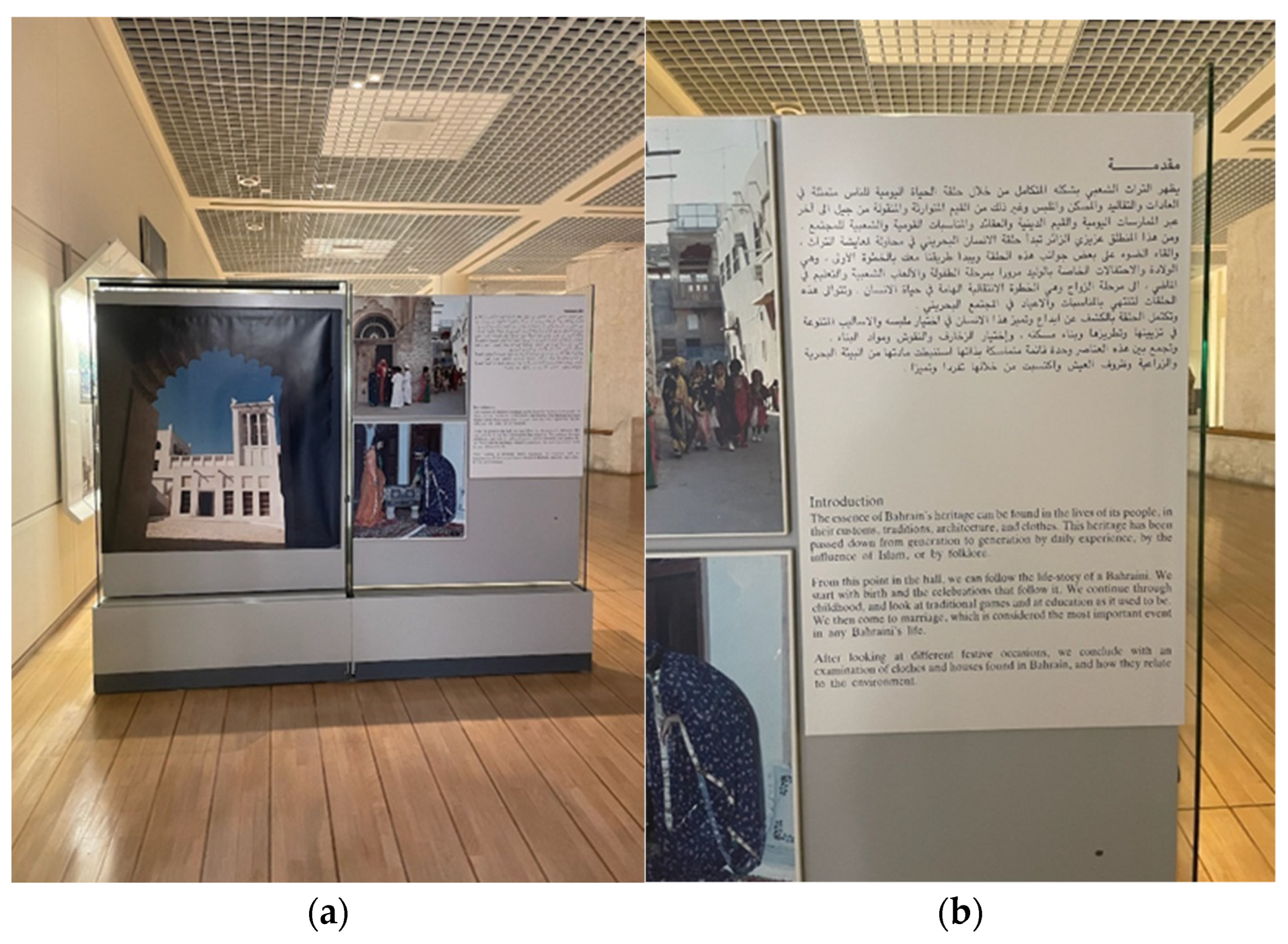

The Case Study: National Museum of Bahrain

5. Results

5.1. Findings from Online Survey

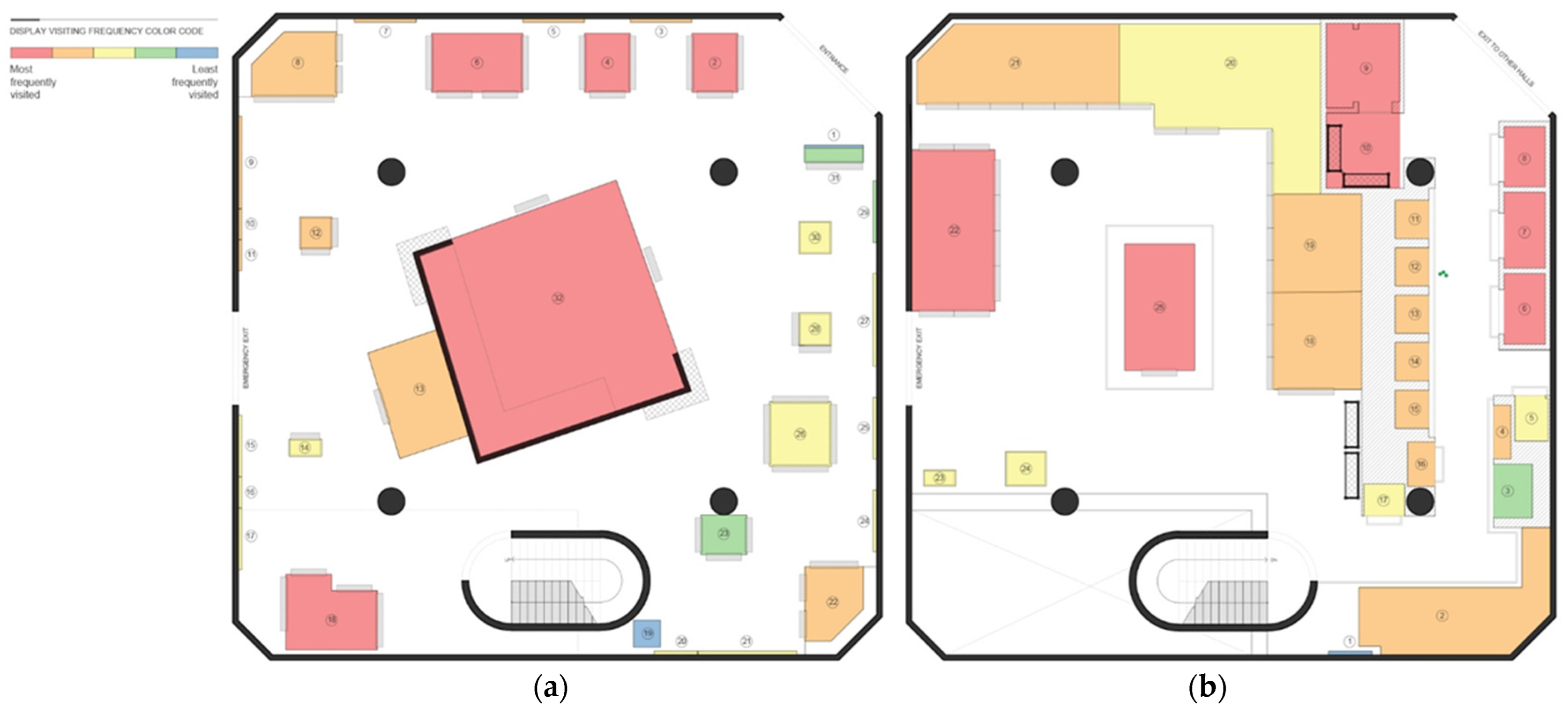

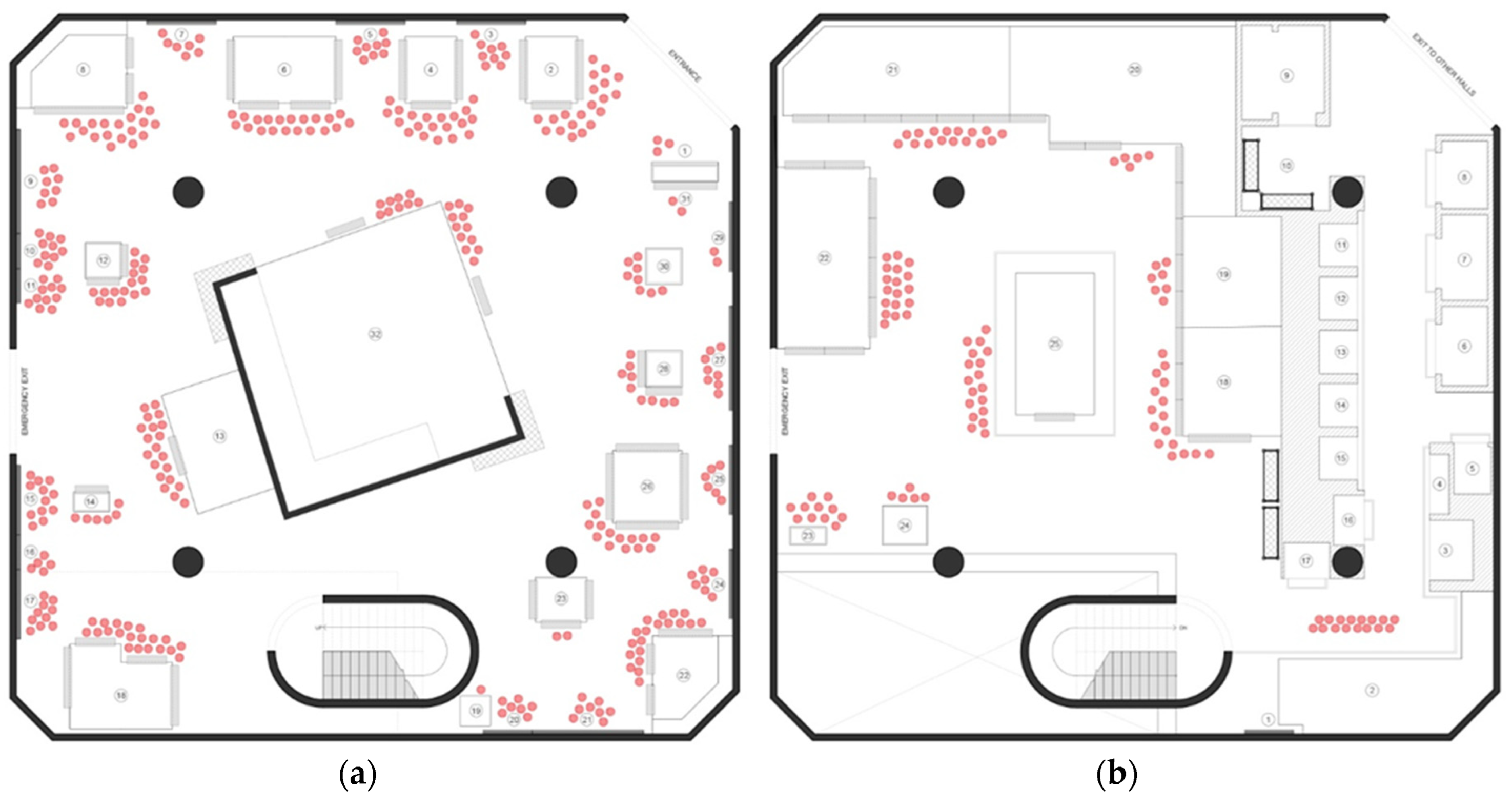

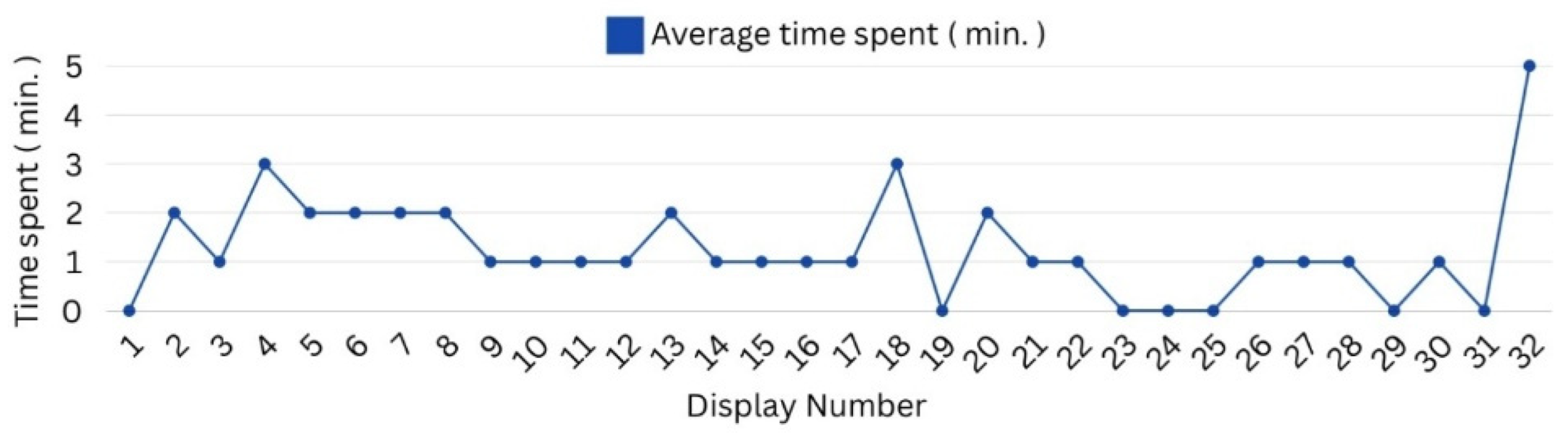

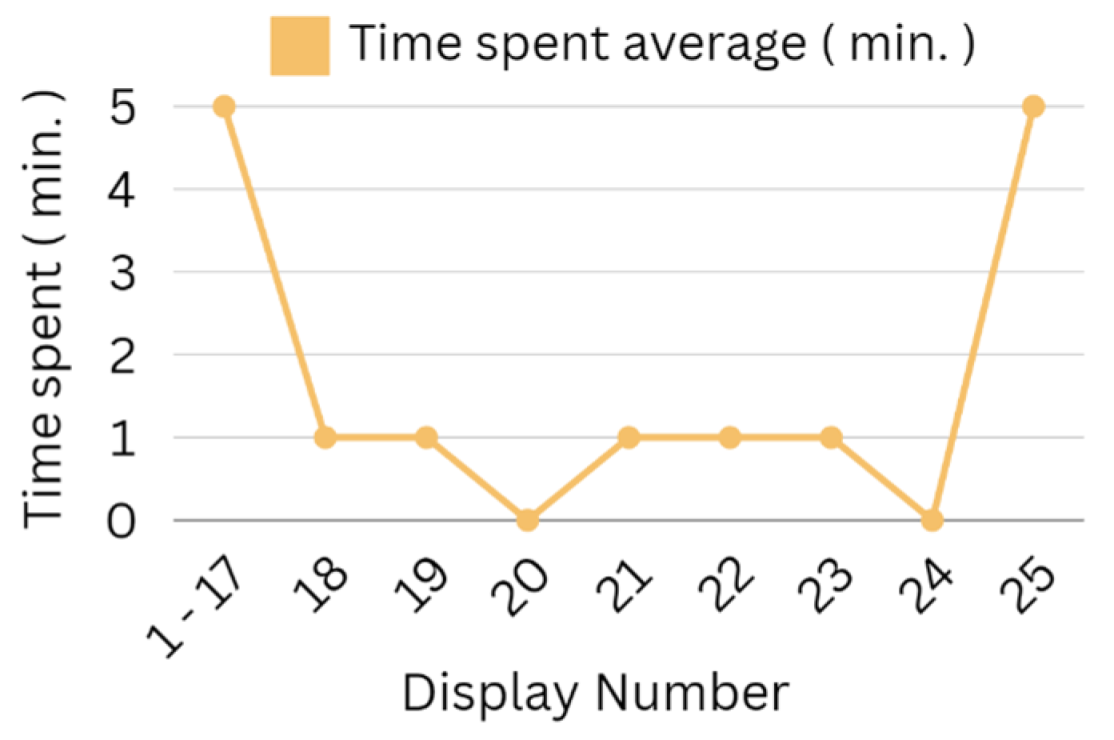

5.2. Findings from Tracking of Visitors

= [534 + 470] sq mt/45 min

= 1004 sq mt/45 min.

= 22.31 sq mt/min

= 76/86 × 100 = 88.37%

5.3. Visitor Experience at the Bahrain National Museum Through Their Interviews

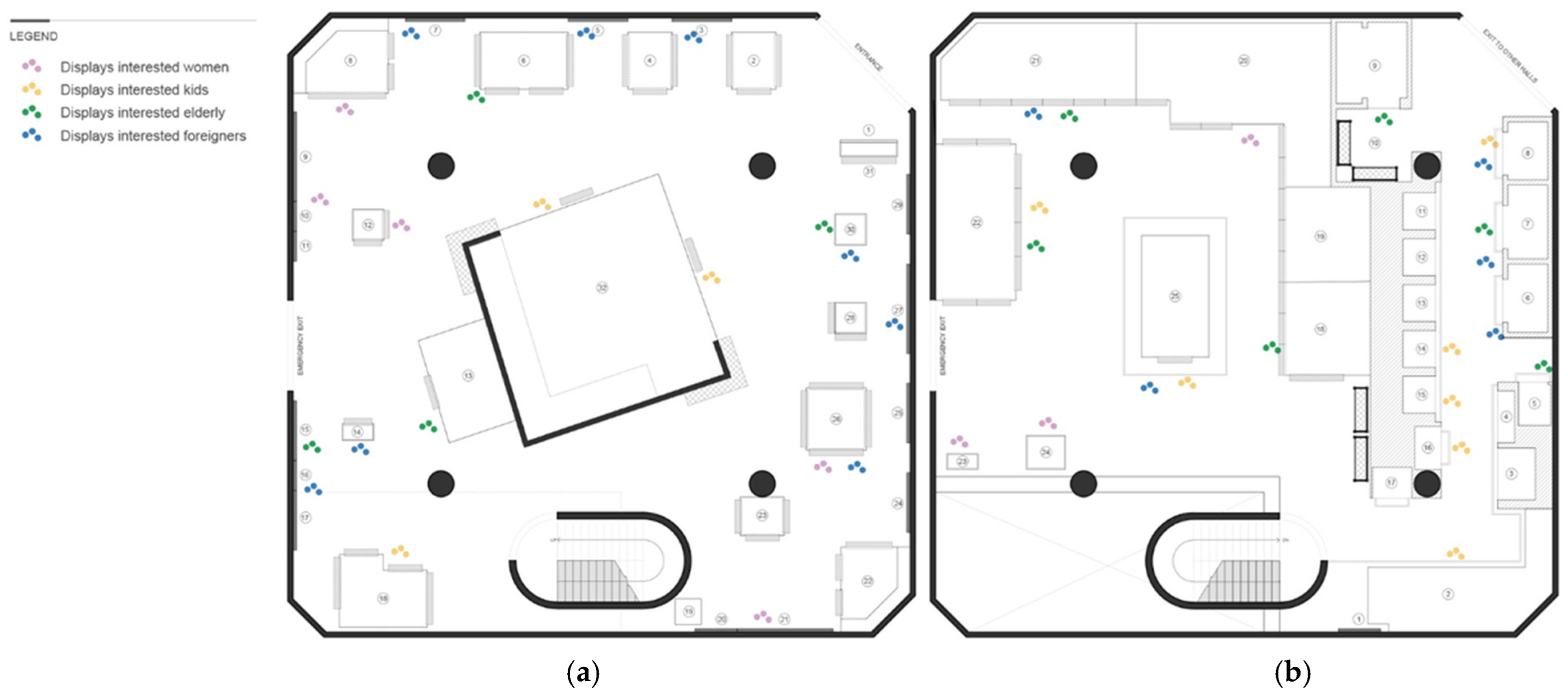

5.4. Visitor Experience at the Bahrain National Museum Through Their Space Observations

6. Discussion

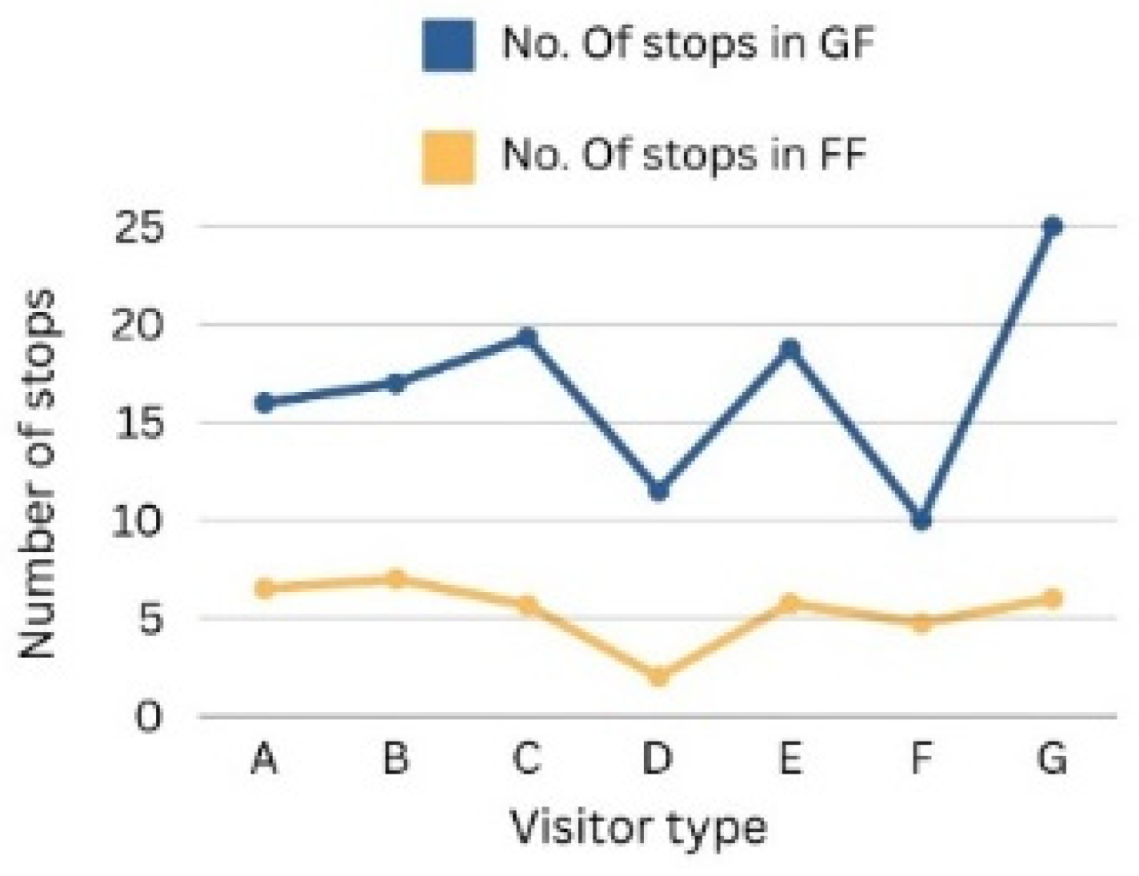

6.1. Visitors’ Engagement in the Hall and Gallery Spaces at the National Museum of Bahrain

6.2. Exhibits That Effectively Capture Visitor Attention

6.3. The Areas That Experience Low Engagement

7. Conclusions and Recommendation

7.1. Visitors’ Engagement and Patterns

7.2. Areas of Improvement for Enhancing Engagement of Visitors

- Regular assessments across all galleries should be prioritized to ensure adaptive and visitor-centered enhancements.

- Understanding visitor behavior and engagement patterns is essential for designing more interactive, educational, and enjoyable experiences.

- Real-time observation of visitor interactions will provide curators with valuable insights to refine exhibit layouts, programming, and interpretation methods.

- Establishing formal feedback channels—currently absent—will ensure that the museum remains relevant to the visitors and allow them to express their preferences and suggest improvements.

7.3. Limitation of the Study

7.4. Recommendations for Improvement

- Improving signage and providing clearer directions can help visitors navigate through both floors of the museum more effectively. Employing visible and engaging markers or digital guides can ensure visitors know all available exhibits.

- Developing comprehensive self-guided tools, such as audio guides, mobile apps, and detailed maps, can assist visitors in navigating the museum independently.

- Organizing exhibits in a more intuitive sequence that naturally leads visitors through all areas can help prevent missed sections. The central staircase should be considered in the exhibit flow to avoid premature exits.

- Incorporating visual and interactive elements to draw visitors to all museum areas can ensure a more complete exploration of exhibits. Materials aimed at younger audiences can significantly improve engagement for families. Interactive elements can include touchscreens, hands-on activities, and storytelling sessions designed for children.

- Understanding the demographics of visitors, such as the influx of international tourists on weekends and local families during the week, can inform targeted engagement strategies to meet diverse visitor needs.

- Provide robust interpretive materials, including multilingual descriptions and interactive kiosks, that can meet visitor demands for more information and enhance the educational experience.

- Provide accessible labels to wheelchair users and children while also considering those with poor eyesight or limited mobility by using bold, high-contrast text that remains legible even in dim lighting for conservation purposes. Labels should be visible to multiple viewers simultaneously, readable from a distance, and concise enough to enhance rather than overshadow the experience of observing the object.

- Adjusting lighting, ensuring consistent temperature control, improving acoustics, and clearly distinguishing seating areas can enhance overall visitor comfort and engagement.

- Collect visitor feedback during tracking studies to enhance engagement, improve wayfinding, and refine exhibit design based on visitor insights and comparisons with other museums.

7.5. Future Research

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Falk, J.H.; Dierking, L.D. The Museum Experience Revisited; Left Coast Press: Walnut Creek, CA, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

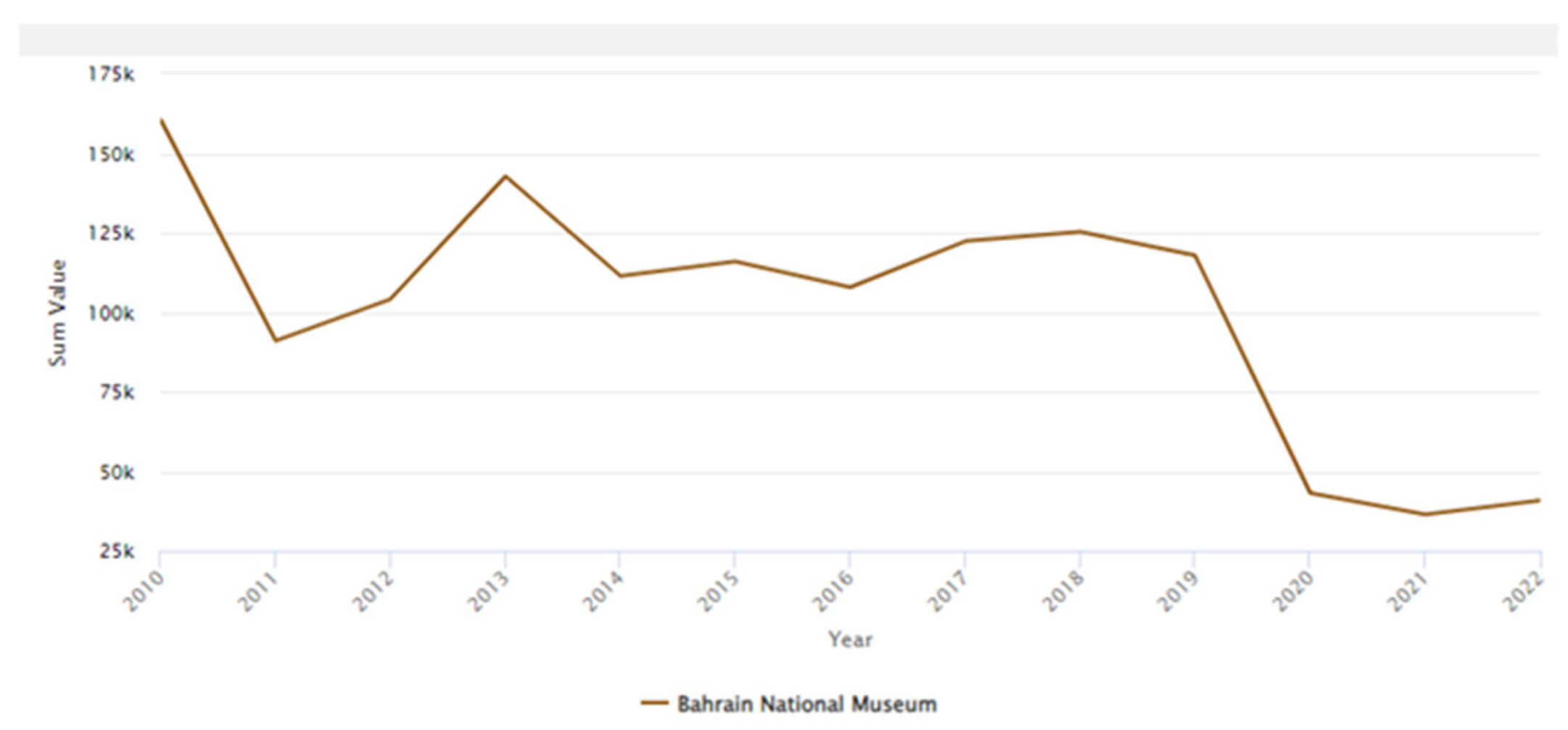

- Information & eGovernment Authority. Visitors of Heritage Landmarks (BACA). Available online: https://www.data.gov.bh/explore/dataset/01-visitors-of-heritage-landmarks-baca-1/analyze/?disjunctive.heritage_landmarks&sort=-year&refine.heritage_landmarks=Bahrain+National+Museum (accessed on 22 February 2025).

- Vom Lehn, D. Embodying experience: A video-based examination of visitors’ conduct and interaction in museums. Eur. J. Mark. 2006, 40, 1340–1359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tzortzi, K. Museum architectures for embodied experience. Mus. Manag. Curatorship 2017, 32, 491–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hijazi, A.N.; Baharin, H. The Effectiveness of Digital Technologies Used for the Visitor’s Experience in Digital Museums. A Systematic Literature Review from the Last Two Decades. Int. J. Interact. Mob. Technol. 2022, 16, 142–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bitgood, S. Museum Visitor Studies: Understanding Visitor Behavior; Routledge: London, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- International Council of Museums (ICOM). ICOM Museum Definition. 2022. Available online: https://icom.museum/en/ (accessed on 2 February 2025).

- Falk, J.H.; Dierking, L.D. The Museum Experience; Routledge: London, UK, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Falk, J.H. Identity and the Museum Visitor Experience; Routledge: London, UK, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Serrell, B. Paying Attention: Visitors and Museum Exhibitions; American Association of Museums: Washington, DC, USA, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Hein, G.E. Learning in the Museum; Routledge: London, UK, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Falk, J.H.; Dierking, L.D. Learning from Museums: Visitor Experiences and the Making of Meaning; Rowman & Littlefield: Lanham, MD, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Bitgood, S. An Attention-Value Model of Museum Visitors. Visit. Stud. 2010, 13, 33–47. [Google Scholar]

- Falk, J.H.; Storksdieck, M. Using the contextual model of learning to understand visitor learning from a science center exhibition. Sci. Educ. 2005, 89, 744–778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Canter, D. The Psychology of Place; Architectural Press: London, UK, 1977. [Google Scholar]

- Bitgood, S. Attention and Value: Keys to Understanding Museum Visitors; Left Coast Press: Walnut Creek, CA, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Falk, J.H. Assessing the impact of exhibit arrangement on visitor behavior. Visit. Stud. 1993, 6, 15–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robinson, E.S. The Behaviour of the Museum Visitor; American Museum of Natural History: New York, NY, USA, 1928. [Google Scholar]

- American Association of Museums. Museum Standards and Best Practices; American Association of Museums: Washington, DC, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Kaplan, R.; Kaplan, S. The Experience of Nature: A Psychological Perspective; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Falk, J.H.; Dierking, L.D. The Museum Experience Revisited; Routledge: London, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Falk, J.H.; Storksdieck, M.; Dierking, L.D. Exploring the Role of Free-Choice Learning in Public Understanding of Science. Sci. Educ. 2008, 92, 1059–1075. [Google Scholar]

- Wojciechowski, R.; Walczak, K.; White, M.; Cellary, W. Building virtual and augmented reality museum exhibitions. In Proceedings of the Ninth International Conference on 3D Web Technology, Monterey, CA, USA, 5–8 April 2024; pp. 135–144. [Google Scholar]

- Bitgood, S. Social Design in Museums: The Psychology of Visitor Studies; MuseumsEtc: Edinburgh, UK, 2011; Volume 1. [Google Scholar]

- Leinhardt, G.; Crowley, K.; Knutson, K. Learning Conversations in Museums; Lawrence Erlbaum Associates: Mahwah, NJ, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Hooper-Greenhill, E. Studying Visitors. In A Companion to Museum Studies; Macdonald, S., Ed.; Blackwell: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2006; pp. 362–376. [Google Scholar]

- Olesen, A.R.; Holdgaard, N. Why Play in Museums? A Review of the Outcomes of Playful Museum Initiatives. J. Mus. Educ. 2024, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serrell, B. Exhibit Labels: An Interpretive Approach, 2nd ed.; Rowman & Littlefield: Lanham, MD, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Chiozzi, G.; Andreotii, L. Behaviour vs. Time: Understanding How Visitors Utilise the Milan Natural History Museum. Curator 2001, 44, 153–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bitgood, S.; Shettel, H.H. An overview of visitor studies. J. Mus. Educ. 1996, 21, 6–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serrell, B. Paying Attention: The Duration and Allocation of Visitors’ Time in Museum Exhibitions. Curator Mus. J. 1997, 40, 108–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crane, V. (Ed.) . Informal Science Learning: What the Research Says About Television, Science Museums, and Community-Based Projects; Research Communications Ltd.: Dedham, MA, USA, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Melton, A. Problems of Installation in Museums of Art; AAM Monograph, New Series No. 14; American Association of Museums: Washington, DC, USA, 1935. [Google Scholar]

- Melton, A. Distribution of Attention in Galleries in a Museum of Science and Industry. Mus. News 1936, 14, 6–8. [Google Scholar]

- Bitgood, S.C.; Loomis, R.J. Environmental Design and Evaluation in Museums. Environ. Behav. 1993, 25, 683–697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelly, L.; Gordon, P. Developing a community of practice: Museums and reconciliation in Australia. In Museums, Society, Inequality; Sandell, R., Ed.; Routledge: London, UK, 2002; pp. 153–174. [Google Scholar]

- Bitgood, S.; Patterson, D.; Benefield, A. Exhibit Design and Visitor Behavior: Empirical Relationships. Environ. Behav. 1998, 20, 474–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yalowitz, S.; Bronnenkant, K. Tracking and Timing: Unlocking Visitor Behavior. Visit. Stud. 2009, 12, 47–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Australian Museum Audience Research Centre. Visitors to the Australian Museum Use Social Media. 2010. Available online: https://australian.museum/blog-archive/museullaneous/visitors-to-the-australian-museum-use-social-media/ (accessed on 10 February 2025).

- Loomis, R.J. Museum Visitor Evaluation: New Tool for Management; American Association for State and Local History: Nashville, TN, USA, 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Bishop, K.; Marshall, N.; Rahmat, H.; Thompson, S.; Steinmetz-Weiss, C.; Corkery, L.; Tietz, C.; Park, M. Behavior Mapping and Its Application in Smart Social Spaces. Encyclopedia 2024, 4, 171–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.; Lee, S. Optimizing Museum Layout Using Visitor Tracking Data. J. Mus. Manag. Curatorship 2020, 35, 150–165. [Google Scholar]

- Falk, J.H.; Dierking, L.D. The Museum Experience: Enduring Concepts, Revised Edition; Left Coast Press: Walnut Creek, CA, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, J.; Park, M.; Choi, Y. Enhancing Visitor Engagement through Real-Time Tracking and Data Analytics. Mus. Stud. J. 2021, 45, 220–235. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, A.; Jones, B. Data-Driven Design: Utilizing Visitor Behavior Insights to Improve Museum Exhibits. Int. J. Cult. Policy 2022, 28, 75–89. [Google Scholar]

- Bollo, A.; Pozzolo, L. Analysis of Visitor Behaviour Inside the Museum: An Empirical Study. 2005. Available online: http://neumann.hec.ca/aimac2005/PDF_Text/BolloA_DalPozzoloL.pdf (accessed on 10 February 2025).

- Bitgood, S. An Analysis of Visitor Circulation: Movement Patterns and the General Value Principle. Curator Mus. J. 2006, 49, 463–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hooper-Greenhill, E. Museums and the Interpretation of Visual Culture; Routledge: London, UK, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Tzortzi, K. Museum Space: Where Architecture Meets Museology; Routledge: London, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Ferguson, M.; Walby, K.; Piché, J. Tour Guide Styless and Penal History Museums in Canada. Int. J. Tour. Res. 2016, 18, 477–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hood, M.G. Staying away: Why people choose not to visit msuseums. Mus. News 1983, 61, 50–57. [Google Scholar]

- Serrell, B. Exhibit Labels: An Interpretive Approach; Rowman & Littlefield: Lanham, MD, USA, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Roppola, T. Designing for the Museum Visitor Experience; Routledge: London, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar]

| Visitor Group Number | Visitor Type | Number of Visitors | Weekday | Weekend | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Morning | Afternoon | Morning | Afternoon | |||

| 1 | Family–Local | 3 | ✓ | |||

| 2 | Family–Local | 4 | ✓ | |||

| 3 | Family–Foreigner | 5 | ✓ | |||

| 4 | Family–Foreigner | 4 | ✓ | |||

| 5 | Family–Foreigner | 4 | ✓ | |||

| 6 | Family–Foreigner | 2 | ✓ | |||

| 7 | Individual–Foreigner | 1 | ✓ | |||

| 8 | Individual–Foreigner | 1 | ✓ | |||

| 9 | Individual–Foreigner | 1 | ✓ | |||

| 10 | Individual–Local | 1 | ✓ | |||

| 11 | Individual–Local | 1 | ✓ | |||

| 12 | Group–Foreigner | 2 | ✓ | |||

| 13 | Group–Foreigner | 3 | ✓ | |||

| 14 | Group–Foreigner | 3 | ✓ | |||

| 15 | Group–Foreigner | 2 | ✓ | |||

| 16 | Group–Local | 4 | ✓ | |||

| 17 | Group–Local | 2 | ✓ | |||

| 18 | Group–Local | 2 | ✓ | |||

| 19 | Group–Local | 3 | ✓ | |||

| 20 | Tourist group | 18 | ✓ | |||

| 21 | Tourist group | 20 | ✓ | |||

| Respondent Number | Background | Category | Duration of Interview (Minutes) | Visit to Museum | When the Interview Was Conducted |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Local | Family | 1.24 | 1 | End of journey in GF hall |

| 2 | Foreigner | Family | 4.00 | 1 | Middle of GF journey |

| 3 | Local | Group | 1 | 2 | End of journey in GF hall |

| 4 | Local | Individual | 1.10 | 1 | End of journey in GF hall |

| 5 | Foreigner | Group | 3.50 | 1 | End of journey in GF hall |

| 6 | Foreigner | Individual | 3.25 | 1 | End of journey in GF hall |

| 7 | Local | Individual | 10.00 | 1 | End of journey |

| 8 | Local | Family | 24 | 2 | End of journey |

| 9 | Foreigner | Family | 1 | 1 | Middle of GF journey |

| 10 | Local | Family | 2 | 1 | Beginning of the first hall |

| 11 | Foreigner | Individual | 1 | 1 | End of journey |

| 12 | Foreigner | Group | 0.20 | 1 | End of journey |

| 13 | Local | Group | 0.40 | 1 | End of journey |

| 14 | Foreigner | Group | 3.10 | 1 | End of journey |

| 15 | Foreigner | Group | 4.27 | 1 | Middle of GF journey |

| 16 | Foreigner | Family | 2.20 | 1 | End of GF hall |

| 17 | Foreigner | Individual | 1.37 | 1 | End of journey |

| 18 | Foreigner | Individual | 6.05 | 2 | End of journey |

| 19 | Foreigner | Group | 2.30 | 3 | End of journey |

| Category of Exhibits | Classification Criteria | Description |

|---|---|---|

| Size | Small, Medium, Large, Very Large | Based on 2D and 3D space occupied by the display (for this study only) |

| Goal Served | educational, entertainment | Classified based on whether the display serves purely educational purpose or edutainment purpose or both |

| Dimension | 2D, 3D | 2D: panels, photographs, paintings, and images; 3D: can be viewed from multiple angles |

| Interaction method | Read only, marginally engaging, interactive | Read only: Relies on textual/ static visual content; marginally engaging: uses senses beyond just reading; interactive: engages multiple senses and encourages participation |

| Visitors type | Individuals, family and Groups | Individuals: Local, individual–Foreigner; Family–Local, Family–Foreigners; Group–Local, Group–Foreigners, Group–Tourists |

| stopping behaviour | Visitors’ engagement duration | A stop in this study is defined as standing in front of the display for at least one minute including reading, observing, interacting. Time talking on phone or doing any other unrelated activity is excluded. Less than one minute stop is mentioned as ZERO in the notes. |

| Attraction Power | Power of display to attract | Done for each display, calculated as: No of visitors who stopped/no of visitors tracked |

| sweep Rate Index | visitors’ movement, slow/fast | Calculated for entire gallery; since accurate sizes of small, medium, large, very large displays with adjacent spaces were not known |

| Diligent Visitors | stopping by more than 50% displays | Stops considered as minimum one minute |

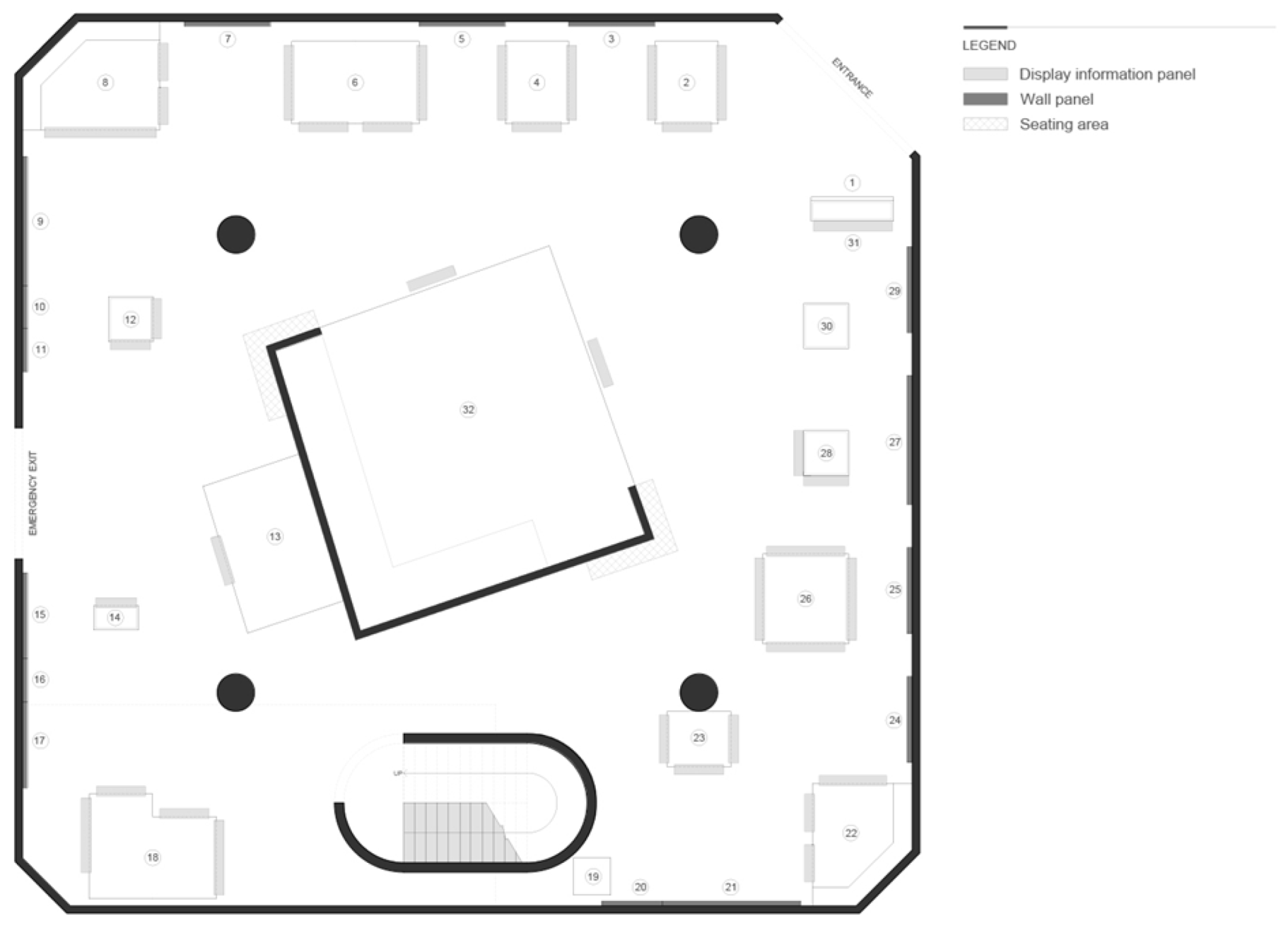

| Display Number | Description | Description | Size of the Display | Type of Exhibit | Integration of Technology | Interaction Mode |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ground Floor | ||||||

| Display 1 | Introduction panel | a short introduction explaining the flow of the exhibits | small | 2D (text & images) | None | Reading material |

| Display 2 | Birth display | model of a mother with her baby crip along with panels explaining the rituals following the birth of a child | medium | 3D + 2D (text & images) | None | Visual interaction |

| Display 3 | Childhood information panel | panels describing the ceremonies and treatments for children | small | 2D (text & images) | None | Reading material |

| Display 4 | Child teething celebration display | 3d model of the tradition of nanoon (child’s teething celebration) | medium | 3D + 2D (text & images) | None | Visual interaction |

| Display 5 | Children games information panel | description of traditional children’s games with supporting images | small | 2D (text & images) | None | Reading material |

| Display 6 | Education display | model of a school and a teacher learning the Qur’an | large | 3D + 2D (text & images) | Background sound | Visual interaction |

| Display 7 | Education & marriage information panel | a panel explaining the government schools system, and a panel about finding a marriage partner and the gift prepared for a bride | small | 2D (text & images) | None | Reading material |

| Display 8 | Wedding display | 3d model of a bride’s good luck party | large | 3D + 2D (text & images) | Background sound | Visual interaction |

| Display 9 | Wedding information panel | panels describing wedding ceremonies | medium | 2D (text & images) | None | Reading material |

| Display 10 | Women beauty information panel | panels describing women beauty tools and techniques | small | 2D (text & images) | None | Reading material |

| Display 11 | The Family information panel | panel describing the family and the social values | small | 2D (text & images) | None | Reading material |

| Display 12 | Bride jewelry display | model of a bride with her traditional jewellery, cloths, and henna party | small | 3D + 2D (text & images) | None | Visual interaction |

| Display 13 | The baraha display | model of men’s outdoor gathering area (Baraha) | large | 3D + 2D (text & images) | None | Visual interaction |

| Display 14 | Healing by Qura’an display | display of tools used to treat the evil eye and curing by the holy word of Qur’an | small | 3D + 2D (text & images) | None | Visual interaction |

| Display 15 | Medicine information panel | description of folk medicine with supporting images and graphs | small | 2D (text & images) | None | Reading material |

| Display 16 | Arabic time information panel | description of Arabic time with supporting images and graphs | small | 2D (text & images) | None | Reading material |

| Display 17 | Festivities information panel | description of traditional festivities with supporting images | small | 2D (text & images) | None | Reading material |

| Display 18 | Heyya Beyya display | model of kids festivities before Al-Adha Eid celebration with a song in the background | large | 3D + 2D (text & images) | Background sound | Visual interaction |

| Display 19 | Safe box display | display of a safe box used to keep valuables | small | 3D + 2D (text & images) | None | Visual interaction |

| Display 20 | Fashion information panel | description of traditional fashion with supporting images | small | 2D (text & images) | None | Reading material |

| Display 21 | Embroidery information panel | description of traditional embroidery with supporting imagrs | medium | 2D (text & images) | None | Reading material |

| Display 22 | Making kurar display | model of women making Kurar (Gold threads) | large | 3D + 2D (text & images) | None | Visual interaction |

| Display 23 | Budleh lace embroidery display | model of a woman maing lace embroidery | medium | 3D + 2D (text & images) | None | Visual interaction |

| Display 24 | Women’s costumes information panel | description of women traditional costumes with supporting images | small | 2D (text & images) | None | Reading material |

| Display 25 | Men’s costumes information panel | description of men traditional costumes with supporting images | small | 2D (text & images) | None | Reading material |

| Display 26 | Costumes display | model of a man and a woman in their traditional costumes | large | 3D + 2D (text & images) | None | Visual interaction |

| Display 27 | Architecture information panel | description of traditional architecture with supporting images and plans | medium | 2D (text & images) | None | Reading material |

| Display 28 | Palm branch houses display | model of a Kubbar (Bahraini winter houses made of stones and palm) and palm branch dwellings | small | 3D + 2D (text & images) | None | Visual interaction |

| Display 29 | Architecture information panel | description of traditional architecture with supporting images and plans | small | 2D (text & images) | None | Reading material |

| Display 30 | Seyadi house display | 3D model of Seyadi’s house | small | 3D + 2D (text & images) | None | Visual interaction |

| Display 31 | Building material display | display of building tools with information about building profission and materials | small | 2D (text & images) | None | Reading material |

| Display 32 | Old house display | a model of part of a bahraini house in real scale showing the courtyard and with surrounding walls and other details | very large | 3D + 2D (text & images) | None | Visual interaction |

| Display Number | Description | Description | Size of the Display | Type of Exhibit | Integration of Technology | Interaction Mode |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| First Floor | ||||||

| Display 1 to 17 | Various crafts shops | model of popular markets and variety of shops showing different crafts and professions | very large | 3D | None | Visual interaction |

| Display 18 | Weaving pottery | model of a man using a manual weaving machine | large | 3D + 2D (text & images) | None | Visual interaction |

| Display 19 | Pottery making display | model of a man doing different types of pottery | large | 3D + 2D (text & images) | None | Visual interaction |

| Display 20 | Village house display | model showing men and women doing various house chores | very large | 3D + 2D (text & images) | None | Visual interaction |

| Display 21 | Palm leaves product making display | model of men producing products by weaving palm leaves | very large | 3D + 2D (text & images) | None | Visual interaction |

| Display 22 | Sea trades display | model of men doing various sea trades like fishing, pearling, and types of baots | very large | 3D + 2D (text & images) | None | Visual interaction |

| Display 23 | Types of pearls display | display of various pearls sizes and colors | small | 3D + 2D (text & images) | None | Visual interaction |

| Display 24 | Pearl selling tools | display of tools used by pearl sellers | small | 3D + 2D (text & images) | None | Visual interaction |

| Display 25 | Diving display | model of traditional baots and iniature divers and fishermen | very large | 3D + 2D (text & images) | None | Visual interaction |

| Visitor | Category | Floor | Start Point | End Point | Time of Journey | Displays Visited | Displays Skipped | Pattern | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Individual- foreigner [Visitor no: 9] | Ground Floor | RightTurn: Display 2 | Display: 32 | 20 min | 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17, 18, 23, 21, 22, 24, 25, 26, 28, 27, 29, 30, 31, 32 | 1, 19, 20 | Regular Flow pattern, visit through 91% displays | Figure 8a |

| First Floor | Left Turn: Display 18 | Display: 10 | 18, 19, 20, 21, 22, 23, 24, 25, 17, 2, 3, 16, 4, 5, 15, 14, 13, 6, 12, 11, 7, 8, 9, 10 | 1 | Regular Flow pattern, Visit through 96% displays | Figure 8b | |||

| 2 | Family- Foreigner [Visitor no: 4] | Ground Floor | Right turn: Display 2 | Display: 18 | 17 min | 2, 3, 4, 32, 6, 7, 8, 12, 13, 18 | 1, 5, 7, 9, 10, 11, 14, 15, 16, 17, 19, 20, 21, 22, 23, 24, 25, 26, 27, 28, 29, 30, 31 | Irregular Flow Pattern, visit through 19% displays | Figure 8a |

| First Floor | Left Turn: Display 25 | Display: 9 | 25, 22, 21, 20, 19, 18, 2, 3, 16, 15, 14, 13, 6, 7, 8, 10, 9 | 1, 17, 3, 4, 5, 11, 12, 23, 24 | Irregular Flow Pattern, visit through 64% displays | Figure 8b | |||

| 3 | Group–Local [Visitor No: 16] | Ground Floor | Left Turn: Display 30 | Display: 18 | 15 min | 30, 27, 28, 25, 26, 32, 6, 7, 8, 9, 12, 13,1 4, 18 | 1, 31, 29, 9, 10, 11, 2, 3, 4, 5, 15, 16, 17, 19, 20, 21, 22, 23, 24 | irregular flow pattern, visit through 40% displays | Figure 8a |

| First Floor | Left Turn: Display 25 | Display: 9 | 25, 22, 21, 20, 19, 18, 2, 3, 16, 15, 14, 13, 12, 11, 10, 9 | 1, 23, 24, 17, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8 | irregular flow pattern, visit through 60% displays | Figure 8b | |||

| 4 | Group–Tourist [Visitor No: 21] | Ground Floor | Right Turn: Display 2 | Display: 23 | 30 min | 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16, 18, 20, 21, 22, 244, 25, 26, 27, 28 | 11, 29, 30, 31, 1 | Regular flow pattern, visit through 84% displays | Figure 8a |

| First Floor | Left Turn: Display 18 | Display: 9 | 18, 19, 20, 21, 22, 23, 24, 25, 2, 17, 3, 16, 4, 15, 5, 14, 13, 6, 12, 11, 7, 8, 10, 9 | 1 | Regular flow pattern, visit through 96% displays | Figure 8b |

| Visitors Type | Displays Favoured on Ground Floor | Topics of Displays | Displays Favoured on First Floor | Topics of Displays |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Women | 8, 10, 12, 21, 26 | Wedding, Beauty, Bridal, Costumes, embroidery | 20, 23, 24 | Village house, Pearls, Pearl Tools |

| Kids | 32, 18 | Heyya Beyya (Kid’s activities), Old House display | 22, 25, 2, 16, 15, 14, 2, 8 | Sea Trade, diving, Crafts and Profession |

| Elderly Locals | 13, 15, 30, 6 | Seyadi House, men’s outdoor, Folk Medicine, Education | 9, 21, 18, 5, 7 | Crafts and Professions, Weaving |

| Foreigners | 3, 5, 7, 30, 27, 26, 16, 14 | Childhood ceremony, games, schools, Seyadi House, Architecture | 21, 22, 6, 7, 8, 25 | Palm product, Sea Trade, Diving, Crafts and Professions |

| Visitor Group Number | Visitor Type | No. of Stops in GF (Out of 32 Stops) | Average | No. of Stops in FF (Out of 9 Stops) | Average | No. of Total Stops | Percentage of Exhibits Stopped at | Average Percentage of Total Exhibits Stopped at |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Family–Local | 15 | 12.5 | 6 | 5.5 | 21 | 51.2% | 44% |

| 2 | Family–Local | 10 | 5 | 15 | 36.6% | |||

| 3 | Family–Foreigner | 14 | 17 | 6 | 7 | 20 | 48.8% | 60% |

| 4 | Family–Foreigner | 12 | 5 | 17 | 41.5% | |||

| 5 | Family–Foreigner | 10 | 8 | 18 | 43.9% | |||

| 6 | Family–Foreigner | 32 | 9 | 41 | 100.0% | |||

| 7 | Individual–Foreigner | 20 | 19.3 | 0 | 5.6 | 20 | 48.8% | 61% |

| 8 | Individual–Foreigner | 8 | 9 | 17 | 41.5% | |||

| 9 | Individual–Foreigner | 30 | 8 | 38 | 92.7% | |||

| 10 | Individual–Local | 10 | 11.5 | 0 | 2 | 10 | 24.4% | 33% |

| 11 | Individual–Local | 13 | 4 | 17 | 41.5% | |||

| 12 | Group–Foreigner | 20 | 18.75 | 9 | 5.75 | 29 | 70.7% | 61% |

| 13 | Group–Foreigner | 13 | 3 | 16 | 39.0% | |||

| 14 | Group–Foreigner | 20 | 4 | 24 | 58.5% | |||

| 15 | Group–Foreigner | 22 | 7 | 29 | 70.7% | |||

| 16 | Group–Local | 10 | 10 | 5 | 4.75 | 15 | 36.6% | 36% |

| 17 | Group–Local | 0 | 9 | 9 | 22.0% | |||

| 18 | Group–Local | 20 | 5 | 25 | 61.0% | |||

| 19 | Group–Local | 10 | 0 | 10 | 24.4% | |||

| 20 | Tourist group | 25 | 25 | 6 | 6 | 31 | 75.6% | 76% |

| 21 | Tourist group | 25 | 6 | 31 | 75.6% |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Al Khalifa, H.E.; Jiwane, A.V. Visitors’ Interactions with the Exhibits and Behaviors in Museum Spaces: Insights from the National Museum of Bahrain. Buildings 2025, 15, 1324. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15081324

Al Khalifa HE, Jiwane AV. Visitors’ Interactions with the Exhibits and Behaviors in Museum Spaces: Insights from the National Museum of Bahrain. Buildings. 2025; 15(8):1324. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15081324

Chicago/Turabian StyleAl Khalifa, Haifa Ebrahim, and Anamika Vishal Jiwane. 2025. "Visitors’ Interactions with the Exhibits and Behaviors in Museum Spaces: Insights from the National Museum of Bahrain" Buildings 15, no. 8: 1324. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15081324

APA StyleAl Khalifa, H. E., & Jiwane, A. V. (2025). Visitors’ Interactions with the Exhibits and Behaviors in Museum Spaces: Insights from the National Museum of Bahrain. Buildings, 15(8), 1324. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15081324