A Comparative Study of the Spatial Features of Chinese and Korean Academies: A Case Study of BaiLuDong Academy and Tosan Academy

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Research Review and Research Subjects

2.1. Research Review

- China

- 2.

- Korea

- 3.

- Research Gap

2.2. Research Subjects

- China’s BaiLuDong Academy

- 2.

- Tosan Academy in Korea

3. Materials and Methods

4. Comparative Analysis of Chinese and Korean Academies

4.1. The Site Selection of Academies—The Unique Ecological Wisdom of East Asian Confucianism

4.1.1. To Express One’s Emotions Through Mountains and Rivers

- BaiLuDong Academy

- 2.

- Tosan Academy

4.1.2. Feng Shui Treasures

- China’s BaiLuDong Academy

- 2.

- Tosan Academy in Korea

4.1.3. Unity of Nature and Humanity

4.2. The Architectural Space of Academies—A Physical Manifestation of Confucian Ritual Thought

- China’s BaiLuDong Academy

- 2.

- Tosan Academy in Korea

4.3. The Landscape of the Academy—Confucian Concept of Natural Ecology

4.3.1. Landscape Spatial Morphological Characteristics

4.3.2. Water Features

4.3.3. Plants

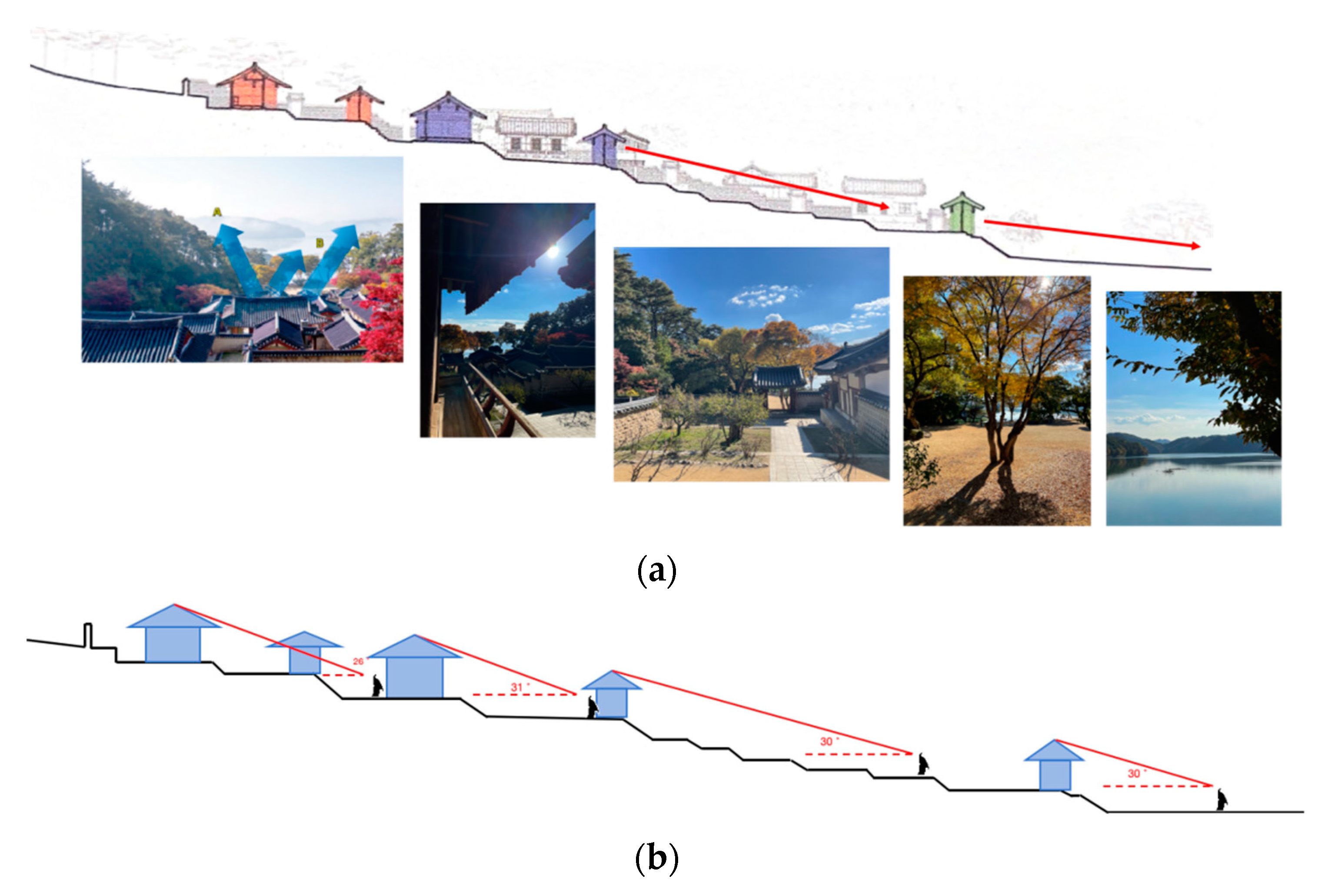

4.3.4. Viewing Mode

4.4. The Decorations of the Academy

4.4.1. Plaques

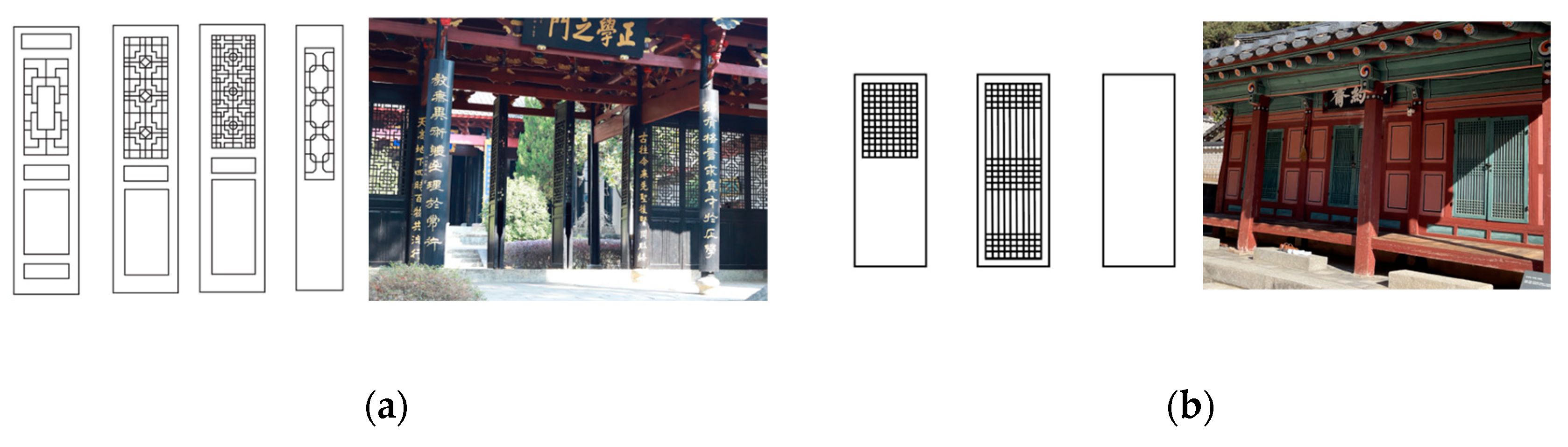

4.4.2. Door Patterns

4.4.3. Column Bases

4.4.4. Roof Decoration

4.4.5. Materials and Colors

5. Discussion

- (1)

- Architectural Spatial Organization: Ritual Order, User Needs, and Local Adaptation

- (2)

- Differences in Landscape Spatial Organization: Philosophical Perceptions of Nature

- (3)

- Architectural Ornamentation: Expressions of Hierarchy and Social Order

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Deng, H.; Huang, Y. Academies: A Cultural Heritage for Scholars. China Cult. Herit. 2014, 10–21+8. [Google Scholar]

- Hong, Y. The Mission of Teaching and the Establishment of Learning: A Study of Southern Song Academies and Neo-Confucianism. Ph.D. Thesis, Hunan University, Changsha, China, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Deng, H. History of Chinese Academies; Dongfang Publishing Center: Beijing, China, 2004; Volume 110. [Google Scholar]

- Deng, H. The Development of Northern Song Academies and the Strengthening of Their Educational Functions. J. Henan Univ. (Soc. Sci. Ed.) 1996, 48–52. [Google Scholar]

- Zeng, H.; Wang, X. A Study on the Inner Spirit and Historical Evolution of Academy Culture. J. Hunan Univ. (Soc. Sci. Ed.) 2023, 37, 34–40. [Google Scholar]

- Wan-ki, C.; Jong-seop, K. Seowon of Korea; Daewonsa Temple: Seoul, Republic of Korea, 1991; pp. 20–28. [Google Scholar]

- Zheng, W. The History of Korean Academies and the Compilation of Academy Chronicles. J. Hunan Univ. (Soc. Sci. Ed.) 2007, 11–12. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, H. Yi Hwang’s Perception of Rural Communities and His Neo-Confucian Community Ideal as Seen through Letters. J. Korean Stud. 2023, 52, 83–112. [Google Scholar]

- Deng, H.; Zhao, W. Korean Academies in Historical Perspective and Their “Outstanding Universal Value”: A Preliminary Discussion on Korea’s World Heritage Nomination. Univ. Educ. Sci. 2019, 59–65+126. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, S. Annals of Chinese Academies Through the Ages; Jiangsu Education Press: Nanjing, China, 1995; pp. 30–61. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, Y. The End of Classical Academies and Their Impact on Modern Chinese Universities. Ph.D. Thesis, Southwest University, Chongqing, China, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, J.; Zhang, Z. A Brief Discussion on the Relationship Between Academy Funding and Academy Development. J. Nanchang Norm. Univ. 2021, 126–129. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, S. Culture and Architecture of Chinese Academies; Hubei Education Press: Wuhan, China, 2002; pp. 38–59. [Google Scholar]

- Li, H.; Deng, H.; Pan, J. Zhu Xi, academies, and the tradition of private lectures. Jiangxi Educ. Res. 1988, 61–67+39. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, C.; Li, H.; Wang, H.; Zhuang, Z. A Comparative Study of “Learning and Practice Spaces” between Buddhist Monasteries and Academies. Shanxi Archit. 2024, 16–19. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, S. Academy Architecture and Traditional Cultural Thought—Exam Paper on Architecture. Cent. China Archit. 1990, 31–36. [Google Scholar]

- Wan, S. The Semantic Structure and Commemorative Characteristics of Chinese Academy Architecture. Huazhong Archit. 2006, 78–81. [Google Scholar]

- Xin, L.; Wei, Z. Interpretation of Ritual Culture Space in Academies Based on Space Syntax—A Case Study of Yuelu Academy. Urban Archit. 2022, 127–130. [Google Scholar]

- Yan, J. The Characteristics of Carving and Mural Art in Chen Clan Academy of Guangzhou. J. Fine Arts 2016, 117–122. [Google Scholar]

- Meng, X.; Wu, Z.; Zou, Y. The Educational Function and Enlightenment of Traditional Academy Garden Landscapes. J. Beijing Jiaotong Univ. (Soc. Sci. Ed.) 2016, 147–152. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, G.; Chen, Y. Analysis of the Historical Development and Landscape Creation of Ancient Academy Gardens in Jiangxi. Urban Archit. 2021, 182–184+189. [Google Scholar]

- Yuan, J.; Hu, M.; Wang, L. Exploration of the Characteristics and Design Techniques of Plant Landscapes in Ancient Academy Gardens. Guangdong Landsc. Archit. 2018, 55–58. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Z. Protection and World Heritage Application of Educational Cultural Heritage: Reflections on the Rising Trend of East Asian Confucian Educational Cultural Heritage Applications. China Cult. Herit. 2020, 48–57. [Google Scholar]

- Wei, Z. Value, Dilemmas, and Paths: Exploring the Protection and Inheritance of China’s Academy Intangible Cultural Heritage. J. Yangtze Univ. (Soc. Sci. Ed.) 2024, 24–30. [Google Scholar]

- Kang, P. Recognition of Trees and Cultural Transformation in China and Korea—Focusing on the Pagoda Tree and Zelkova Tree. Daegu Hist. Rev. 2015, 118, 113–142. [Google Scholar]

- An, D. The Development Patterns of Sarim’s Academy Activities in Danseong-hyeon from the 18th to 19th Century. Daedong Korean Class. Lit. 2024, 79, 47–78. [Google Scholar]

- Jong-hee, C.; Young-sook, M.; Dong-hyun, K. Landscape Preservation and Management Plan for Namgye Academy in Hamyang, a World Heritage Candidate. J. Korean Inst. Tradit. Landsc. Archit. 2013, 31, 128–135. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, S.-H. Seowon: The Architecture of Korea’s Private Academies. Hollym Int. Corp. 2005, 49–62. [Google Scholar]

- Seok-ha, J. A Comparative Study on the Layout Characteristics of Hyanggyo and Academy Architecture in the Joseon Dynasty. J. Archit. Inst. Korea Fed. 2005, 7, 101–107. [Google Scholar]

- Sang-hae, L. An Archaeological Study on the Architectural Attributes of Sungyang Academy. Poeun Stud. 2019, 24, 73–107. [Google Scholar]

- Ki-seok, L. A Study on the Spatial Analysis of Academy Architecture in the Joseon Dynasty—Focusing on the Comparison between Dosan Academy and Byeongsan Academy. Korean Inst. Spat. Des. 2021, 16, 73–87. [Google Scholar]

- Jae-mok, C. Toegye’s Philosophy and the Metaphor of the ‘Mirror’. Yangming Stud. 2009, 24, 265–311. [Google Scholar]

- Jong-hyun, C. A Study on the Construction Ideology of Dosan Seodang as Reflected in Classical Literature. J. Korea Inst. Urban Des. 2005, 6, 85–111. [Google Scholar]

- Byung-gi, H. The Establishment of Dosan Seodang and Toegye’s Theory of Learning. Andong Stud. 2014, 13, 162–185. [Google Scholar]

- Jae-mo, J. The Introduction of Pavilion Structures and the Realization of the Main Hall in Joseon Dynasty Academies. Korean Acad. Stud. 2022, 15, 349–377. [Google Scholar]

- Sung-ho, L.; Young-hoon, K. A Study on the Pavilion Structures of Academies and Hyanggyo—Focusing on Gyeongsangnam-do and Gyeongsangbuk-do. J. Archit. Inst. Korea Fed. 2006, 2, 273–278. [Google Scholar]

- Deok-su, C.; Jung-hae, P. A Study on the Feng Shui Environment of Simgok Academy. J. Ind. Promot. Res. 2023, 8, 163–174. [Google Scholar]

- Qi, Y. Development and Prosperity: A Study on the Cultural Development History of Bailudong Academy. Mod. Commun. 2017, 58+57. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, J. Zhu Xi’s Renovation of Bailudong Academy and the Revival of Neo-Confucianism. J. Hunan Univ. (Soc. Sci.) 2024, 115–123. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, K. Lushan World Heritage Application Documentation; Baihuazhou Literary and Art Publishing House: Nanchang, China, 2020; pp. 21–75. [Google Scholar]

- Li, S. The Dissemination and Development of Zhu Xi’s Philosophy in the Goryeo Period. J. Nanchang Univ. (Humanit. Soc. Sci.) 2013, 44, 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Kwang-woo, L. The Changing Patterns of Korean and Chinese Academies through School Regulations from the 16th to the 19th Century. Korean Acad. Stud. 2022, 14, 43–106. [Google Scholar]

- Young-hoon, L.; Jong-sang, S. A Study on the Characteristics and Historical Significance of Academy Landscaping in the Joseon Dynasty. J. Korean Tradit. Landsc. Archit. 2023, 41, 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Seung-woo, L. Korean Culture: The Spatial Hierarchy and Architectural Culture of Dosan Academy. Korean Thought Cult. 2008, 41, 359–381. [Google Scholar]

- Myung-ja, K. A Visit to Dosan Academy in the Early 18th Century and Its Significance through the “Simwonrok”. Toegye Stud. Confucian Cult. 2013, 53, 51–84. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, S.; Liu, S. The Harmony of Ritual and Music: An Overview of Academy Architecture; Haitian Publishing House: Shenzhen, China, 2021; pp. 120–121. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, Q. Academies and Mountain Forest Culture. Xungen 2006, 26–29. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, H. The Historical Evolution of Academies and the Value Orientation of the Scholar-Officials. J. Hunan Univ. (Soc. Sci.) 2007, 5–11. [Google Scholar]

- Rao, J. Lushan’s Peach Blossom Land and Its Cultural Formation and Accumulation. J. Jiujiang Univ. 2008, 9–11. [Google Scholar]

- Ji-eun, K. The Social History of Academies: The Emergence of Commoner-Class Confucian Scholars and Social Embellishment—Focusing on the Case of Jangsan Academy. J. Korean Acad. Stud. 2024, 19, 351–371. [Google Scholar]

- Jong-ho, L. Toegye Yi Hwang’s Acceptance of Natural Beauty and His Aesthetics of Landscape. Toegye Stud. Confucian Cult. 2007, 41, 219–261. [Google Scholar]

- Jae-bin, Y. The Pictorial Representation of Dosan Academy in the 18th Century and Its Meaning—Focusing on the Paintings of Dosan Academy by Kang Se-hwang and Jeong Seon. J. Toegye Stud. 2016, 139, 147–197. [Google Scholar]

- Dong-wook, K. Toegye’s Architectural Perspective and Dosan Seodang. J. Archit. Hist. Korean Soc. Archit. Hist. 1996, 5, 18–38. [Google Scholar]

- Rui-xi, Z.; Jia-bi, S. (Eds.) Five Records of Bailudong Academy, Volume 1; Compiled by the Bailudong Academy Ancient Records Compilation Committee; Zhonghua Book Company: Beijing, China, 1995; pp. 157–491. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, J. The Construction of Zhejiang Academies; China Architecture & Building Press: Beijing, China, 2022; pp. 203–204. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, Z.; Zhang, S.; Peng, Y. Ecological Wisdom in Architectural Heritage—A Case Study of the Wind Environment in the Bailudong Academy Complex. South. Archit. 2023, 49–57. [Google Scholar]

- Seong-dae, P.; Dong-hwan, S. Toegye’s Perception of Feng Shui Reflected in Toegye’s Historic Sites. J. Korean Stud. 2012, 345–378. [Google Scholar]

- Yeon-ho, K. A Study on the Location of Dosan Seodang and the Layout of Dosan Academy. J. Toegye Stud. 2008, 3, 1–41. [Google Scholar]

- Tan, T. On the View of Nature in the I Ching. J. Yunnan Agric. Univ. (Soc. Sci.) 2017, 50–55. [Google Scholar]

- Jiang, M. Landscape and Living Environment of Traditional Academies in Southern China; China Architecture & Building Press: Beijing, China, 2022; p. 107. [Google Scholar]

- Deng, K. A Study on the Educational Function of Traditional Academy Architecture in Jiangxi Province. Master’s Thesis, Nanchang University, Nanchang, China, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, Z. Sacred and Enlightenment: A Probe into the Religious Spirit of Yuelu Academy’s Culture. Acad. Forum 2016, 39, 115–119. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, L. A Brief History of Chinese Academies: The Evolution and Content of Academies in the Song, Yuan, Ming, and Qing Dynasties; Educational Science Publishing House: Beijing, China, 1981; p. 156. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, G.; Li, H. Bailudong Academy; Hunan University Press: Hunan, China, 2013; pp. 164–165. [Google Scholar]

- Gao, F. The History, Present, and Future of Bailudong Academy. Chin. Tradit. Dwell. 2009, 104–109. [Google Scholar]

- Chai, J. A Study on the Stone Deer Carvings at Bailudong Academy. Master’s Thesis, Jiangxi Normal University, Nanchang, China, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, M. A Comparative Study on Spatial Morphology of Traditional Academies in Fujian and Jiangxi Based on Space Syntax. Master’s Thesis, Hebei University of Engineering, Hebei, China, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Park, K.-S. A Study on Dosan Seodang. Korean Stud. Rev. 2011, 39, 263–289. [Google Scholar]

- Kwon, K. A Study on the Development Process of Dosan Seowon. Master’s Thesis, Kyungil University Graduate School, Gyeongsangbuk-do, Republic of Korea, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, F.; Liu, Y.; Xu, Y. An Analysis of the Landscape Characteristics of Northern Song Dynasty Academy Gardens. Huazhong Archit. 2011, 113–115. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, J.-Y. The Educational Life and Meta-Education of Toegye Yi Hwang. Princ. Educ. Res. 2004, 9, 213–249. [Google Scholar]

- Zhong, X. A Brief Analysis of the Architectural Environment of Bailudong Academy. Archit. Cult. 2013, 50–52. [Google Scholar]

- Jaegang, J. “The Existential Aspects of the Imagery of Seodang and Seowon in Toegye’s Poetry”. Daedong Hanmunhak 2008, 28, 239–269. [Google Scholar]

- Won-ho, L.; So-hyun, L.; Hyun-sil, S. The Value of Plants in Joseon Dynasty Seowon through O.U.V (Outstanding Universal Value). In Proceedings of the Korea Contents Association Conference, Seoul, Republic of Korea, 12–13 October 2013; pp. 133–134. [Google Scholar]

- ICOMOS. Evaluation of Nominations of Cultural and Mixed Properties to the World Heritage List: Seowon, Korean Neo-Confucian Academies (No. 1498). Advis. Body Eval. Rep. 2019, 1498, 184. [Google Scholar]

- Lei, H. Artistic Value and Cultural Interpretation: A Study on the Cultural Value of Jin Merchants’ Plaques and Couplets. J. Beijing Inst. Graph. Commun. 2023, 22–30. [Google Scholar]

- Chu, J. A Study on the Art Symbolism of the Chinese Traditional Auspicious Swastika Pattern. Master’s Thesis, Hunan University of Technology, Hunan, China, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Luo, B. The Philosophy of ‘Unity of Heaven and Humanity’ and Traditional Chinese Architecture. J. Hubei Univ. Econ. (Humanit. Soc. Sci. Ed.) 2008, 26–27. [Google Scholar]

- Young-Soon, P.; Hyun-Jung, L.; Kyung-mi, L.; Jung-ah, H. A Comparative Study on Decorative Patterns in Traditional Palace Architecture of Korea, China, and Japan. J. Korean Soc. Des. Cult. 2004, 17, 311–322. [Google Scholar]

- Ju, W. The Influence of Chinese Traditional Thought on Traditional Residential Architecture and Furniture during Korea’s Joseon Period. Art Res. 2009, 64–70. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, J.; Li, Y. A Study on the Daily Life of Students in Ming and Qing Academies. Lantai World 2015, 137–138. [Google Scholar]

| Data Source | Edition | Year |

|---|---|---|

| Chinese Text Project | Newly Revised BaiLuDong Academy Gazetteer | 1592 |

| Online | Jiangxi Gazetteer | 1732 |

| Book | Xingzi County Gazetteer | 1990 |

| Chinese Text Project | BaiLuDong Academy Ancient Gazetteer | Qing |

| Book | Five Types of BaiLuDong Academy Gazetteers | 1995 |

| Yeungnam University Institute of Ethnic Culture | Tosan Academy Architectural Survey Report | 1991 |

| Kyemyung University Tosan Library | Collected Writings of Toegye | 1600 |

| World Heritage Integrated Management Center for Korean Seowon | Master’s Handwritten Notes | 1550–1570 |

| Kansong Museum of Art | Tosan Academy Map | 1735 |

| Academy | Type | Contents |

|---|---|---|

| BaiLuDong Academy | Trees | Trident maple, Osmanthus, Michelia, Acer truncatum, Goldenrain tree, Chinese juniper, Pine, Bamboo, Camellia, Magnolia, Firmiana, Prunus mume (Plum blossom), Liquidambar, Metasequoia, Lohan pine, Waxberry, Banana, Pittosporum, Chinese tallow tree, Mahogany, Cockspur coral tree, Sophora japonica |

| Shrubs | Golden bamboo, Podocarpus, Poplar, Loropetalum, Calycanthus, Privet, Pittosporum tobira, Chinese hibiscus, Red camellia, Chinese fringe flower, Prunus mume, Cotoneaster, Redbud, Hibiscus, White hibiscus, Wintergreen, Sea holly | |

| Herbs | Red-leaf vinegarweed, Wheatgrass, Narcissus, Dandelion, White clover, Spiderwort, Acanthus, Water banana, Alpinia, Globe amaranth, Cymbidium | |

| Tosan Academy | Trees | Plum tree (30), Maple (17), Crape myrtle, Willow, Ginkgo, Persimmon, Papaya tree, Forsythia, Cherry blossom, Camphor, Golden pine, Red bean fir |

| Shrubs | Peony, Chinese peony, Prunus mume, Wintersweet, Hibiscus, Yellow poplar, Fragrant olive | |

| Herbs | Artemisia, White peony |

| Plaque | ||

|---|---|---|

| BaiLuDong |  |  |

| Tosan |  |  |

| BaiLuDong |  |  |

| Name | Picture | Details |

|---|---|---|

| BaiLuDong Academy |  |   |

|   | |

| Tosan Academy |  | |

| Roof Decoration | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| BaiLuDong |  |  |  |

|  |  | |

| Features | Animal motifs: Fish, White Tiger, Bat; Plant motifs: Orchid, Lotus, etc. | ||

| Tosan |  |  |  |

| —— |  | —— | |

| Features | Floral motifs such as chrysanthemum and orchid were used, while no animal motifs were found. | ||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zhu, Y.; Choi, K.-R. A Comparative Study of the Spatial Features of Chinese and Korean Academies: A Case Study of BaiLuDong Academy and Tosan Academy. Buildings 2025, 15, 1311. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15081311

Zhu Y, Choi K-R. A Comparative Study of the Spatial Features of Chinese and Korean Academies: A Case Study of BaiLuDong Academy and Tosan Academy. Buildings. 2025; 15(8):1311. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15081311

Chicago/Turabian StyleZhu, Yirui, and Kyung-Ran Choi. 2025. "A Comparative Study of the Spatial Features of Chinese and Korean Academies: A Case Study of BaiLuDong Academy and Tosan Academy" Buildings 15, no. 8: 1311. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15081311

APA StyleZhu, Y., & Choi, K.-R. (2025). A Comparative Study of the Spatial Features of Chinese and Korean Academies: A Case Study of BaiLuDong Academy and Tosan Academy. Buildings, 15(8), 1311. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15081311