1. Introduction

Refugee camps, initially conceived as temporary safe havens, are designed to offer immediate relief to those fleeing from conflict, persecution, or natural calamities. Yet, as prolonged crises continue to affect millions globally, these camps inevitably evolve into permanent settlements where complex social, cultural, and spatial dynamics necessitate a deeper understanding to improve refugees’ quality of life. The Zaatari Camp in Jordan is a prime example of this evolution. Established in 2012 to accommodate the influx of Syrian refugees escaping a devastating civil war, the camp’s original grid-based layout, initially designed for logistical efficiency, has transformed into spatial arrangements that mirror the inhabitants’ territorial behaviors, cultural identities, and intricate social networks [

1,

2].

The concept of territoriality within refugee camps involves the processes through which individuals and groups assert control, demarcate spaces, and utilize surroundings, influencing access to resources, social interactions, and power dynamics among refugees, host communities, and humanitarian organizations [

3]. This study underscores the pivotal roles of territorial control and spatial organization in revealing critical insights into how refugees adapt their environments to rebuild their lives amid crises.

Prevailing camp planning methodologies traditionally emphasize logistical efficiency and swift aid delivery over the socio-cultural needs of refugees, often resulting in sterile, impersonal environments disconnected from the lived experiences of displaced individuals. Recent scholarly discourse advocates for the integration of socio-cultural factors into camp design, highlighting the necessity for inclusive and adaptive strategies that accommodate refugees’ evolving needs [

4,

5]. This research aims to investigate the influences of territoriality and spatial layout on the transformations observed in Zaatari Camp, focusing on the adaptation processes emerging in response to refugees’ challenges. For Syrian refugees in Zaatari, cultural identity encompasses kinship-based clustering, gendered spatial practices (e.g., segregated courtyards), and symbolic markers (e.g., Arab–Islamic urban forms) that reinforce communal belonging.

Aligning with this perspective, this study integrates theoretical frameworks with empirical observations to address significant gaps in the literature regarding the relationship between spatial patterns and social behaviors in refugee contexts. This line of inquiry echoes [

6] Defensible Space Theory, which suggests that environmental design and layout profoundly affect human behavior and community interaction. By applying Newman’s theory to Zaatari’s distinct setting, this study aims to expand its applicability beyond the original urban context, thereby broadening discussions on refugee camp design.

Research Objectives:

Analyze Cluster Physical Patterns: We investigate how the attributes of defensible space correlate with the emerging cluster physical patterns at Zaatari Camp.

Examine the Role of Territoriality: We explore how the concepts of territoriality influence the clustering of spaces within the camp.

Identify Key Drivers of the Cluster Patterns: We determine which specific attributes of defensible space are most influential in shaping these cluster patterns.

The primary hypothesis of this study posits that the defensible space concept’s attributes significantly influence the development of clustered spatial patterns within Zaatari Camp. To explore this hypothesis further, the following four sub-hypotheses are formulated: the influences of zones of influence, natural surveillance, clearly defined boundaries through territorial markers, and territorial behavior on cluster physical patterns.

This research endeavor aims to expand on these hypotheses through an in-depth examination of Zaatari’s spatial arrangements, deriving findings that spotlight how territoriality, natural surveillance, and boundary demarcation impact refugees’ lived experiences. The study seeks to answer the following critical questions: How do refugees adapt and reinterpret the principles of defensible space to fulfill their immediate socio-cultural needs? What roles do concepts like territoriality, surveillance, and boundaries play in the metamorphosis of rigid grid layouts into organic clusters reflective of the community’s social structures?

By analyzing the spatial patterns resulting from these adaptations in Zaatari Camp, this study will explore how the defensible space principles elucidate these shifts within the context of displaced communities. The significance of this research lies in its potential contribution to both the academic field of refugee studies and the practical sphere of humanitarian camp management. It advances existing scholarship on spatial dynamics within refugee settings by applying Newman’s defensible space theory in a non-Western humanitarian framework. While prior studies have often linked physical environments and community behavior within urban crime prevention contexts [

6,

7], this research seeks to extend that discourse by exploring spatial design’s capacity to cultivate community resilience and cultural identity among displaced populations.

Documenting Zaatari Camp’s adaptations will yield fresh insights into how refugee communities navigate and transform their environments in response to life in limbo. These findings are particularly relevant for humanitarian organizations responsible for camp planning and management. By incorporating refugees’ perspectives into the design process, humanitarian actors can craft nuanced strategies that not only prioritize immediate survival needs, but also longer-term aspirations for community cohesion, cultural expression, and social stability. This research aligns with Sustainable Development Goal 11 (SDG 11), emphasizing the need for inclusive, safe, and sustainable urban environments, even within displacement contexts.

Furthermore, identifying key socio-cultural drivers will provide practical applications for organizations supporting refugees’ integration into local communities and fostering self-reliance. By recognizing the importance of kinship networks and communal living practices, organizations can tailor interventions to empower refugees in shaping their living environments.

In a broader sense, understanding refugee environmental adaptations can inform policy discussions around migration, refugee rights, and humanitarian responses. As organizations deal with the constant influx of displaced peoples, respecting and promoting refugee agency within policy frameworks is imperative. Facilitating a humanitarian response that values socio-cultural contexts in refugee settlements not only enhances the quality of life for affected individuals, but also fosters a sustainable, dignified approach to displacement that upholds human rights and encourages societal integration.

In conclusion, this research aims to significantly enrich the discourse on refugee settlement dynamics by offering actionable insights for academic and practical applications in humanitarian design and policymaking. By focusing on Syrian refugees’ experiences in Zaatari, the study will illuminate the broader implications of spatial dynamics and community interactions, applicable to refugee camps globally. Through inter-disciplinary research synthesis, combined with qualitative and quantitative analyses of spatial maps, surveys, and interviews, this research aspires to present a nuanced understanding of how refugees navigate and transform their environments in pursuit of dignity, community, and identity amid displacement.

2. Literature Review

This literature review explores the complex interplay of territoriality, spatial layout, and refugee agency within the context of camps, presenting a cohesive argument advocating for a deeper understanding of these elements in humanitarian design. As refugee camps transition from temporary shelters to long-term settlements, it becomes critical to investigate how these spaces can reflect not only humanitarian principles, but also the agency and needs of their inhabitants.

2.1. Refugee Agency vs. Humanitarian Design: Spatial Tensions

Refugee camp design reflects the fundamental tensions between humanitarian efficiency and refugee agency. Conventionally, camps prioritize logistical control through standardized layouts aligned with the SPHERE standards and host state policies [

8,

9]. Refs. [

3,

10] critique this paradigm, framing camps as “waiting zones” that institutionalize temporary existence while suppressing opportunities for dignified community life. This biopolitical governance extends to spatial segregation [

11], where rigid designs physically constrain refugee autonomy through movement restrictions and impersonal layouts.

Yet refugees actively subvert these imposed structures. Ref. [

12] observations of shelter modifications and emergent markets reveal how spatial practices foster belonging despite constraints. This aligns with [

13] documentation of citizenship negotiations within camps and [

14] findings in Zaatari Camp, where refugees have transformed gridded layouts into clustered, Arab–Islamic urban patterns through courtyard privatizations and diagonal pathways. Such adaptations exemplify what [

6,

15] identify as socio-cultural resilience expressed through territorial behaviors.

The Grid–Cluster Dichotomy as Manifestation of Tensions

These dynamics crystallize in the physical planning spectrum between grid and cluster layouts.

Grid Layouts: Historically dominant for their logistical efficiency in service distribution, grids now face criticism for impairing social cohesion [

9,

16]. Ref. [

10] notes how their geometric rigidity exacerbates dislocation by negating organic social structures—a pattern initially evident in Zaatari’s original design.

Cluster Layouts: In contrast, decentralized clusters facilitate communal bonds through shared spaces that enable resource pooling and collective decision making [

8,

9]. Zaatari’s shift toward organic clustering reflects this—refugees have reconfigured spaces to embody Arab–Islamic urbanism’s emphasis on privacy [

15] and interdependence [

14], demonstrating the superior adaptability of clustered layouts to long-term settlement needs.

This spatial evolution underscores a critical insight. When refugee agency prevails over rigid humanitarian designs, emergent spatial patterns better accommodate both immediate survival needs and enduring socio-cultural frameworks. The progression from grids to clusters in Zaatari exemplifies how refugee-led adaptations can humanize humanitarian spaces while challenging assumptions about temporariness in camp planning.

Like [

17] findings in informal settlements, Zaatari’s refugee-led spatial modifications reveal how marginalized communities repurpose rigid layouts into socially cohesive environments. Both contexts highlight the necessity of participatory design—where residents’ tacit knowledge of safety, privacy, and communal needs should inform planning.

2.2. Cultural Identity and Spatial Planning of Refugee Camps

The spatial organization of refugee camps evolves dynamically as temporary settlements transition into quasi-permanent communities, with socio-cultural identity formation and temporal pressures continuously reshaping built environments. This dual process—where cultural practices imprint spatial patterns and prolonged displacement forces structural adaptation—reveals camps to be complex, living urban systems rather than temporary holding spaces [

3].

At the heart of this transformation lies cultural identity making through spatial practices. Ref. [

18] seminal comparison of camp and urban refugees demonstrates how spatial segregation can paradoxically strengthen collective identities through shared territorial markers. In Zaatari, this manifests through the deliberate recreation of Syrian socio-cultural patterns—clusters form around mosques and markets [

14], while spatial behaviors reflect the deeply embedded Arab–Islamic principles of privacy and social control [

15]. Such adaptations confirm that cultural identity is not passively preserved but actively rebuilt through daily spatial negotiations.

Time becomes a critical catalyst in this identity formation process. Ref. [

19] study of Sahrawi camps reveals how prolonged displacement triggers material permanence—durable structures emerge alongside nuanced social stratifications that defy the notion of camps as temporary spaces. This mirrors [

10] observations in Dadaab, where decades of occupation have produced intricate territorial claims and urban-like spatial fabrics. Zaatari’s own evolution from a rigid grid layout to organic settlement [

14] exemplifies how temporality forces humanitarian designs to confront their own temporal assumptions, as refugees inevitably reshape spaces to meet their enduring needs.

Crisis moments amplify these spatial negotiations, as seen during COVID-19. Ref. [

20] documents the tension when pandemic restrictions collided with the cultural norms of communal living in camps, forcing improvised adaptations that revealed latent design shortcomings. Such events underscore what [

21] identify as camps’ fundamental duality—simultaneously bound by humanitarian temporality yet evolving toward urban permanence through refugee-led spatial practices.

This synthesis of cultural resilience and temporal pressure suggests that refugee camps follow an inevitable urbanization trajectory, where initial humanitarian designs are gradually overwritten by socio-cultural spatial logics. Understanding this process is crucial for camp planning that accommodates both immediate needs and long-term community formation.

While Zaatari’s refugees have recreated Syrian urban patterns through clustered layouts [

14], Ref. [

22] demonstrate how Jordan’s encampment policies restrict spatial agency compared to urban settlements, where refugees integrate into host cities through informal housing markets. This tension underscores the role of host state policies in mediating socio-cultural adaptations—whether in camps like Zaatari or urban contexts like Amman.

2.3. Spatial Politics in Refugee Camps: Power, Resources, and Vulnerability

The spatial organization of refugee camps constitutes a contested terrain where institutional power, resource control, and social vulnerability intersect. This tripartite framework reveals how humanitarian spaces simultaneously regulate populations while enabling resistance and adaptation.

2.3.1. Institutional Power and Legal Constraints

Biopolitical governance fundamentally shapes camp geographies through spatial control mechanisms. Host states and NGOs operationalize power through deliberate layouts—fencing, restricted zones, and movement limitations create an architecture of containment [

23]. These spatial strategies reflect deeper legal ambiguities regarding land rights, where the indeterminacy of refugee claims systematically diminishes territorial security. The resulting “permanent temporariness” reinforces dependency circuits. Ref. [

23] analysis demonstrates how such spatial governance regimes inhibit refugees’ capacity to establish stable communities through environmental modifications.

2.3.2. Gendered Vulnerabilities in Designed Environments

This institutional spatial order disproportionately impacts vulnerable groups, particularly in its failure to address gendered safety needs. Ref. [

24] documentation of sanitation infrastructure gaps and [

25] research on gender-based violence reveal the following critical paradox: camps designed for universal protection often institutionalize risks for women and children. The neglect of gender-specific spatial needs—from childcare areas to protected bathing facilities—transforms humanitarian spaces into landscapes of compounded vulnerability, where physical design actively undermines social security assurances.

2.3.3. Resource Geographies and Social Stratification

The interplay of power and vulnerability crystallizes in the political economy of resource distribution. As [

26,

27] demonstrate, the spatial allocation of water points, clinics, and aid services does not follow a neutral humanitarian logic, but rather reproduces existing ethnic and kinship hierarchies. In arid regions like Zaatari’s Jordanian desert location, water scarcity exacerbates these dynamics, transforming infrastructure placement into instruments of social control. Refugees navigate these imposed geographies through adaptive territorial claims—such as modifying shelter clusters near resources or establishing informal redistributive networks—yet remain constrained by the fundamental power asymmetries embedded in camp designs.

This triadic analysis reveals refugee camps as inherently political spaces, where spatial configurations materialize institutional power while simultaneously generating sites of vulnerability and resistance. Understanding these dynamics is essential for moving beyond technical planning paradigms to engage with camps as complex socio-political ecologies.

While Zaatari’s water distribution reflects kinship-based hierarchies [

27], Azraq Camp’s evolution of decentralized environmental health services (Behnke et al., 2024) [

28] offers a model for equitable resource governance in protracted displacement. This contrast underscores the potential of localized, refugee-involved management to reduce dependency on top-down aid systems.

2.4. Defensible Space Theory: A Framework for Understanding Spatial Dynamics

Ref. [

6] defensible space theory is operationalized in Zaatari Camp. Refugees create zones of influence (private, semi-private, and leftover spaces) through physical barriers like tents and fences [

14,

15]. Natural surveillance is achieved via clustered shelters around courtyards, enhancing safety [

6]. Territorial markers (e.g., decorated courtyards) and territorial behavior (restricting access to non-clan members) reinforce socio-cultural identity [

14,

15].

This theory articulates spatial configuration principles derived from human behavior concepts that enable individuals to assert control over their surroundings, thus fostering a sense of community and responsibility, even in contexts where land ownership is absent [

6,

29]. The design of spatial patterns within refugee camps speaks to the necessity of a contextual approach, where cultural norms and values are projected through non-professional practices. Depending on the environment and community dynamics, these spatial configurations can yield either positive or negative outcomes [

6,

7,

30,

31,

32,

33,

34].

Ref. [

6] outlines the following four foundational principles that shape safe, controlled environments:

Zone of Influence: This principle emphasizes the creation of zones of influence, transitioning from private to public spheres. This spatial layout facilitates a sense of ownership, with physical configurations generating distinct areas classified as private, semi-private, semi-public, and public. By manipulating these physical patterns, refugees can extend their ownership to outdoor spaces, perceiving public areas as semi-private or private domains. This practice fosters responsibility and community engagement in defending and securing one’s environment. However, as the number of individuals sharing a space increases, control and surveillance tend to diminish [

6,

34].

Natural Surveillance: This principle refers to the design elements that enable residents to observe and monitor public areas, enhancing safety and utility. The orientation of shelters significantly influences residents’ capacity to oversee communal spaces, particularly through strategic placements of windows and doors that face these areas [

6,

34].

Territorial Markers: This component involves clearly defined boundaries that establish the extent of personal or communal areas of influence. These markers can be physical (fences and walls) or symbolic (planting gardens or placing personal items). Residents often cultivate and maintain these marked areas, which fosters feelings of identity, community, and ownership. Clear boundaries enhance security and reinforce communal ties, making it easier for individuals to identify intrusions and maintain their spatial claims [

6,

34].

Territorial Behavior: This principle encompasses the proactive defense of perceived domains, where individuals or groups feel empowered to safeguard their designated spaces. The degree of territorial behavior can significantly influence the overall atmosphere of security within the camp, contributing to a sense of community stability.

In the context of Zaatari Camp, these defensible space principles are operationalized as refugees repurpose communal areas into semi-private courtyards, reflecting cultural norms surrounding privacy and kinship ties [

35]. This adaptation illustrates how spatial configurations not only enable residents to reclaim agency, but also serve to enhance communal resilience and social interactions within the camp.

Overall, understanding defensible space principles is vital for informing the design and layout of refugee camps in ways that honor the agency of residents and support their social and cultural needs, ultimately guiding efforts toward creating environments that promote dignity and community cohesion.

Theoretical Synthesis: Defensible Space in Refugee Contexts. While [

6] defensible space theory was developed for urban crime prevention, its principles—zones of influence, natural surveillance, and territorial markers—are reinterpreted in Zaatari Camp to serve cultural resilience rather than security. Refugees repurpose communal courtyards as semi-private spaces [

14], blending Syrian urban traditions [

36] with humanitarian constraints. This divergence from Western urban norms underscores the need to adapt defensible space theory to non-Western displacement contexts [

35].

2.5. Neighborhood Social Networks and Community Cohesion

The interconnectivity of small settlements plays a vital role in fostering daily social interactions and solidarity. The spatial patterns within a settlement influence social behavior and community bonds, with certain designs encouraging mutual aid and friendship among residents. Ref. [

29] establishes a social–spatial schema theory explaining how neighborhood boundaries often emerge from social interactions rather than simply geographic demarcations.

As community size increases, tensions may arise, leading to the emergence of sub-groups that can undermine collective identity. Understanding these dynamics can inform the design of refugee camps, ensuring that spatial configurations support rather than hinder communal relationships. In Zaatari, the cul-de-sac system and shared zones foster interdependence, mirroring traditional Arab–Islamic neighborhoods [

15,

36]. However, overcrowding leads to leftover spaces, which diminish surveillance and communal cohesion [

14].

2.6. Gaps and Future Research Directions

The existing literature reveals several gaps, particularly in the underrepresentation of cultural practices in spatial designs and the evolving role of digital technologies in camp management. Future research must address these omissions, focusing not only on the physical and social dimensions of refugee camps, but also on integrating sustainable policies that prioritize long-term solutions, including urbanization and integration with host communities.

Additionally, investigations into how humanitarian actors can adapt to emerging patterns of social dynamics, cultural expressions, and technological advancements will be crucial in enhancing the efficacy of refugee camp management in the face of prolonged displacement scenarios.

The literature underscores the importance of recognizing the agency of refugees and the socio-cultural implications of the spatial layouts within camps. It advocates for a paradigm shift in humanitarian design that prioritizes inclusive, adaptive approaches to reinforce dignity and resilience among displaced populations. Through deeper engagement with the principles of defensible space and an understanding of the complex interplay between territoriality and power dynamics, the objectives of this study will contribute significantly to advancing knowledge and improving practices in refugee camp design and management.

2.6.1. Conceptual Framework

The conceptual framework for this study is based on the interplay between territoriality, spatial layout, defensible space principles, and the agency of refugees within the setting of a refugee camp. The framework identifies key components that influence the living conditions and social dynamics of displaced populations, particularly in the Zaatari Camp context. It integrates insights from the literature on refugee camps, humanitarian design, and socio-cultural practices, highlighting how these dimensions coalesce to shape the experiences of refugees and their interactions with the built environment. The framework integrates defensible space principles (zones of influence and natural surveillance) [

6], refugee agency (shelter modifications and market creation) [

14], and cultural resilience (Arab–Islamic spatial patterns) [

15].

The main elements of the conceptual framework are as follows (

Figure 1):

Territoriality: This refers to refugees’ ability to assert control and ownership over their living spaces. It encompasses their efforts to redefine public spaces as semi-private areas.

Spatial Layout: The physical organization of a camp, whether grid or cluster, significantly impacts social interactions, resource access, and community cohesion. This element includes how refugees adapt and reorganize layouts to meet their cultural and social needs.

Refugee Agency: This concept highlights the active role that refugees take in restructuring their environments, negotiating their identity, and fostering social networks within a camp.

Power Dynamics: The influence of humanitarian actors and state policies on the spatial organization and resource distribution within a camp demonstrates the broader socio-political context in which refugees operate.

Defensible Space Theory: This theory posits that physical design and the organization of space can influence the level of crime and the feeling of safety among residents.

Figure 1.

Conceptual framework: refugee agency and defensible space attributes. Source: Researchers.

Figure 1.

Conceptual framework: refugee agency and defensible space attributes. Source: Researchers.

The key attributes of defensible space include the following:

Zone of influence: Areas that are perceived as socially under the control of a specific group of individuals.

Natural surveillance: The ability of residents to observe their surroundings, contributing to a sense of safety.

Boundary demarcations: The physical and symbolic demarcations that designate territory.

Territorial behavior: Actions taken by individuals to assert control and the claiming of a space.

Together, these attributes show the complex relationships that dictate the conditions within refugee camps and reflect the interplay of design, agency, and resilience among displaced populations.

2.6.2. Aligning Hypotheses with Objectives

General Hypothesis: The attributes of the defensible space concept are drivers for the emerging clustered physical patterns at Zaatari Camp.

Sub-Hypothesis 1: Cluster physical pattern is affected by (correlates with) zones of influence.

Sub-Hypothesis 2: Cluster physical pattern is affected by (correlates with) natural surveillance.

Sub-Hypothesis 3: Cluster physical pattern is affected by (correlates with) boundaries defined through territorial markers and physical and symbolic boundaries.

Sub-Hypothesis 4: Cluster physical pattern is affected by (correlates with) territorial behavior.

3. Methodology

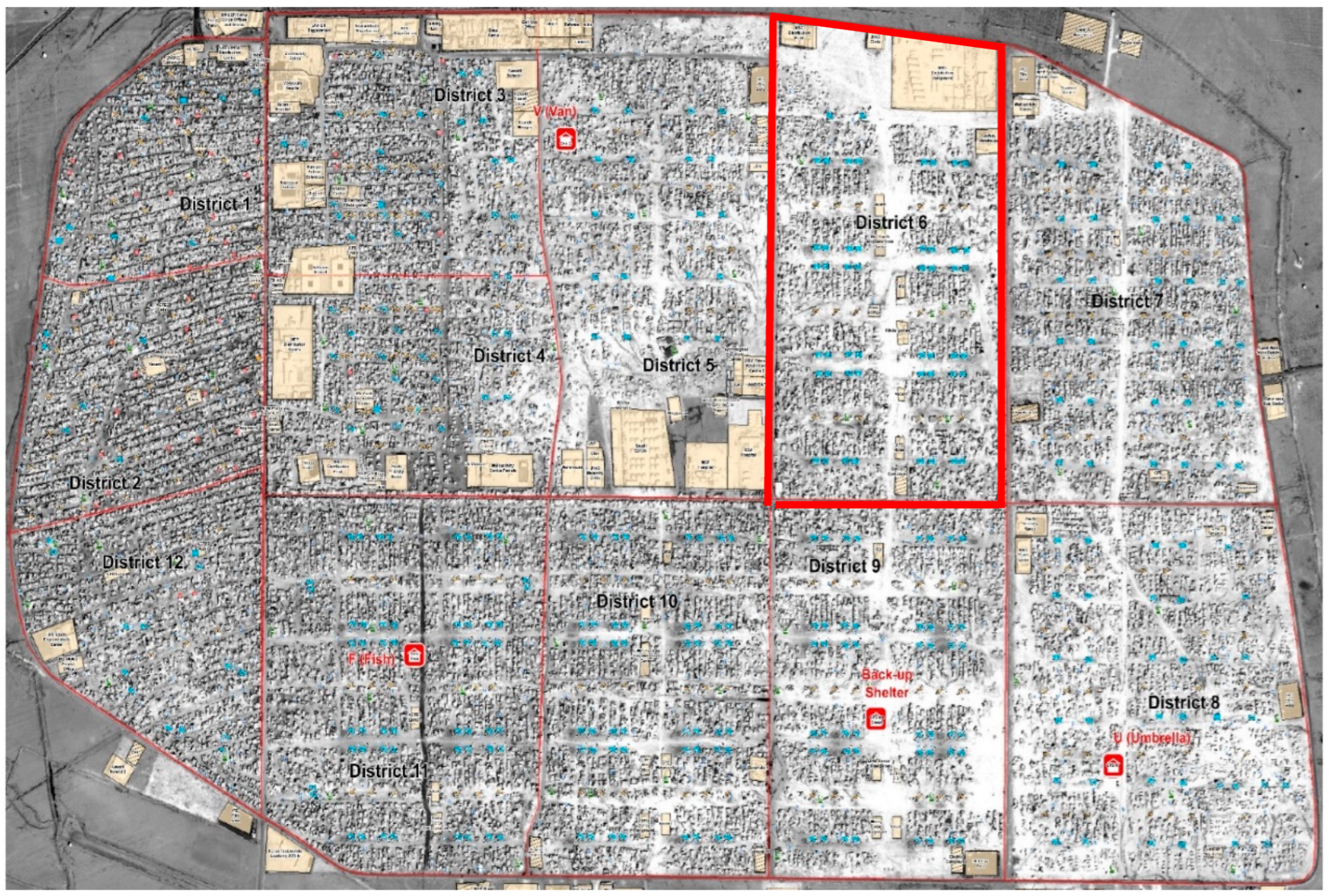

This section details the method used to evaluate how well the defensible space concept fits within the community structure of Zaatari Camp, focusing specifically on district six. A quantitative research design provided a systematic way to gather data from camp residents.

3.1. Data Collection

A structured survey was conducted using a cluster-stratified random sampling method. A total of 102 households from district six completed the structured questionnaires, which focused on key factors such as zones of influence, natural surveillance, and boundary marking.

3.2. Study Area

Zaatari Camp is situated in the Mafraq Governorate of northern Jordan, covering an area of approximately 5.02 km

2. As of the latest count, it hosts about 7975 refugees [

2]. The camp is divided into 12 districts, with district six selected for this study due to its adherence to established UNHCR planning standards, which helped to minimize intervening variables [

1,

37]. This district is characterized by a nearly perfect approximation of its planned capacity (8000 refugees) and actual population (7975), representing a 0.3% variance. This balance makes it an ideal study site, since the district exemplifies compliance with UNHCR standards for the provision of aid, services, safety, and security. The refugees in this district come from diverse origins, further enriching the social dynamics of the community.

Figure 2 shows an aerial photo of the camp, and highlights district six.

3.3. Hypotheses of the Study

3.3.1. General Hypothesis

The primary hypothesis posits that the attributes of the defensible space concept significantly drive the development of cluster patterns within Zaatari Camp.

3.3.2. Sub-Hypotheses

To further explore this primary hypothesis, the following sub-hypotheses are formulated:

Cluster physical patterns are influenced by zones of influence.

Cluster physical patterns are influenced by natural surveillance.

Cluster physical patterns are influenced by clearly defined boundaries through territorial markers.

Cluster physical patterns are influenced by territorial behavior.

3.4. Constructs and Variables

This study measures the independent and dependent constructs associated with physical clustering characteristics and their relationship with defensible space principles.

3.4.1. Independent Construct

Cluster Physical Patterns: The study focuses on understanding two primary community physical layouts, grid and cluster patterns. Clusters that exhibit central spaces are characterized as clustered communities.

3.4.2. Dependent Constructs

Territoriality (Attributes of Defensible Space): Defensible space is operationalized through the following four attributes, as residents can use these to control their environment:

Zones of Influence: This refers to the ability of physical layouts to foster territorial influences perceived as semi-private or private spaces. It was measured using a five-point Likert scale.

Natural Surveillance: This measures the ability of residents to observe public spaces due to the orientation of windows and doors. This was measured through a simple affirmative or negative response format.

Boundaries Demarcation/Territorial Markers: This examines the presence of physical or symbolic boundaries that delineate community spaces. Responses followed a dichotomous format.

Territorial Behavior: This construct is further divided into three subcomponents that reflect residents’ control over their space. It was measured using a Likert scale.

Perceived Privacy Control: Reflects residents’ feelings of privacy within their courtyards.

Perceived Territorial Control: Gauges residents’ perceived ability to prevent intrusions.

Overall Defense: Assesses the capacity to protect courtyards and surrounding clusters.

3.4.3. Confounding Variables

Demographic data were collected, including gender, place of origin, length of stay at the camp, household size, age, education level, and previous housing experience.

3.5. Population of the Study and Sampling Frame

3.5.1. Sampling Technique

The sampling frame had 17 clusters in district six. A stratified sampling technique was utilized to ensure representation from each cluster, with eight households selected from each, culminating in a total sample of 102 subjects.

3.5.2. Sampling Procedure

Houses were randomly selected, starting at Al-Yasmeen Street, choosing every tenth household. If a house was unavailable, the next was approached until the target sample was met.

3.6. Research Instrument

Data were collected via a survey with the following four sections for structured analysis:

Introduction: Explains study aims.

Confounding Variables: Collects demographic data like gender, place of origin, length of stay, educational background, and household composition.

Independent Variables: Assesses the cluster physical patterns, distinguishing between grid and cluster layouts, enabling an understanding of the community’s organization.

Dependent Variables: Measures the attributes of defensible space. It examines the following:

Zones of Influence: Likert-scale questions regarding outdoor space perceptions.

Natural Surveillance: Dichotomous questions assessing design features.

Boundaries Demarcation: Captures both physical and symbolic demarcations.

Territorial Behavior: Constructs assessing privacy, control, and defense strategies.

This structured questionnaire format was vital in obtaining precise, comparable data, allowing for a thorough evaluation of space’s influence on community dynamics.

3.7. Data Analysis

Data were analyzed rigorously using statistical software, involving the following:

Descriptive Statistics: For demographic characteristics and perceptions of defensible space attributes.

Hypothesis testing: We employed multiple linear regression models to assess the relationship between defensible space attributes (independent variables) and cluster patterns (dependent variable). Confounding variables (e.g., household size) were included as covariates. Model fit was evaluated using R2 and F-statistics, with significance thresholds set at p < 0.05

Inferential Statistics: For hypothesis testing using correlation analysis and regression modeling.

Linear regression to test the impacts of defensible space attributes (independent variables: zones of influence, natural surveillance, etc.) on clustering patterns (dependent variable). The model is expressed as follows:

[Y = \beta_0 + \beta_1(X_1) + \beta_2(X_2) + \beta_3(X_3) + \epsilon]

Where (Y) = clustering score, (X_1) = zone of influence, (X_2) = natural surveillance, (X_3) = territorial markers, and (\epsilon) = error term.

Logistic Regression: For binary outcomes (e.g., the presence of territorial markers), with odds ratios reported.

Model Validation: Variance Inflation Factors (VIFs) < 5 confirmed no multicollinearity; residual plots verified homoscedasticity.

We tested for multicollinearity using variance inflation factors (VIF < 5) and confirmed normality via Q–Q plots

3.8. Ethical Considerations

Ethical dimensions were a priority throughout the study. Informed consent was obtained from all participants prior to data collection. The anonymity and confidentiality of the respondents were assured, with data used solely for academic purposes, reflecting the highest ethical standards in conducting research on vulnerable populations.

3.9. Limitations of the Study

Some limitations include the following:

Sampling Bias: While efforts were made to ensure random selection, the inherent constraints of the camp may affect the representativeness of the sample.

Self-Reported Data: The study relies on self-reported measures, which may introduce biases related to personal perception and subjectivity.

This methodology is designed to create a structured framework to analyze the suitability of defensible space concepts in relation to clustered patterns within Zaatari Camp. By integrating diverse constructs, demographic analyses, and a thorough sampling framework, the study aims to provide rich insights that can inform policy and practice in humanitarian design, ultimately enhancing quality of life for refugees.

4. Results

This section presents findings on spatial patterns, defensible space drivers, socio-cultural influences, and hypothesis testing. Descriptive statistics, ANOVA, regression, and chi-square analyses are interpreted.

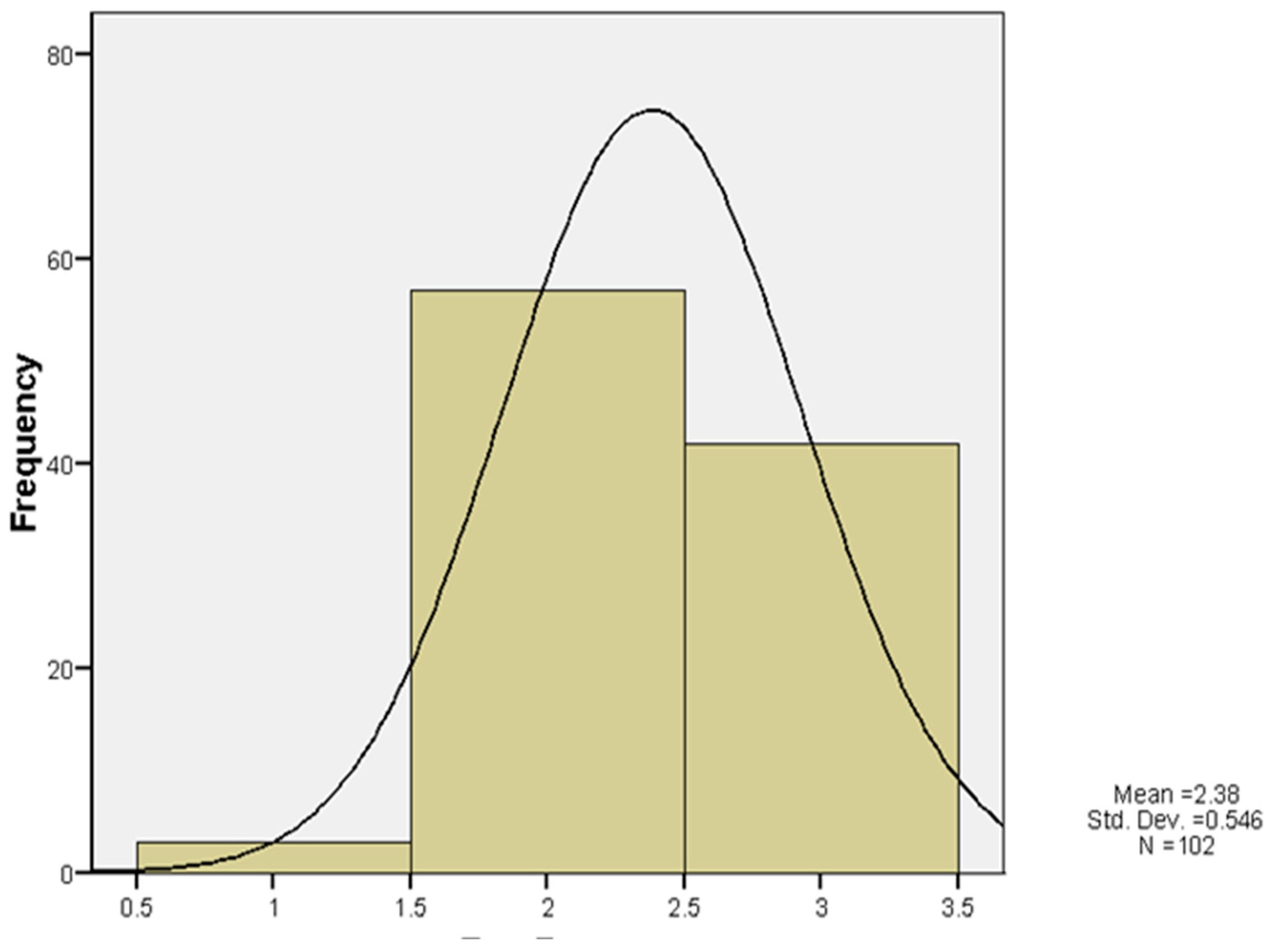

4.1. Descriptive Analysis

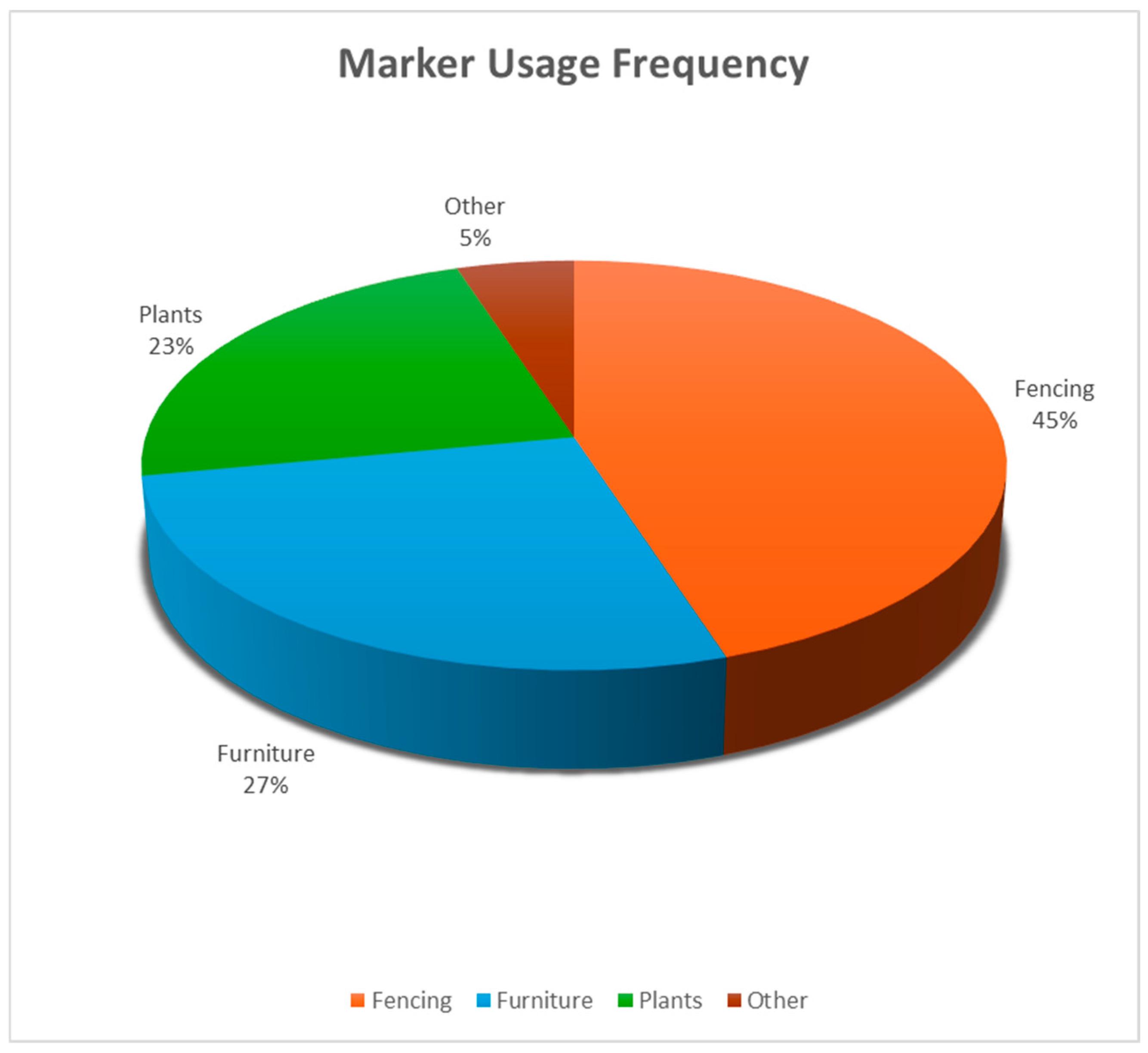

A substantial 72% of households have converted public spaces into semi-private areas, signifying a strong tendency for community-driven space customization. This transformation often uses furniture or plants, emphasizing the importance of personalized space in one’s living environment (

Table 2), see

Figure 3.

- 3.

Defensible Space Drivers:

Zones of Influence: The mean for zones of influence is 3.82 (SD = 0.84) (

Table 3). A large proportion of participants (84%) regard courtyards as home extensions, illustrating a critical perception of outdoor space integration. The positive kurtosis (0.78) reflects a peak distribution of responses around the average value.

Natural Surveillance: With a mean of 1.73 (SD = 0.34) (

Table 3), the observation of spaces, particularly courtyard-facing windows, enhances perceived control, as reported by 74% of respondents. The data display a narrow variance, indicating consensus on surveillance effectiveness.

Boundary Demarcation (Territorial Markers): The mean of boundary demarcation is 1.61 (SD = 0.21) (

Table 3), with a strategy mix that includes fences and plants to create semi-private environments, transforming 68% of public courtyards.

Figure 4 and

Figure 5 illustrate these transformations in detail, primarily using fences (45%), plants (23%), and furniture (27%), reflecting cultural preferences for semi-private spaces and defensible space principles. The data show a slight left-skew, typical in cases of clear dominant behavior or practices.

Perceived Privacy, Territoriality, and Defense (

Table 3): The measures of privacy (mean = 3.30, SD = 1.04), territoriality (mean = 3.61, SD = 0.96), and overall defense (mean = 3.42, SD = 1.01) reflect the community’s inherent strategies in establishing and maintaining control over their spaces, with relatively uniform distributions, as shown by low kurtosis values, indicating stable responses around the mean.

These statistical findings detail the demographic factors, spatial arrangements, and defensible space drivers influencing the community structures in Zaatari Camp. The robust methodology offers insights into social cohesion and space usage, which directly impact community planning and refugee living conditions.

4.2. Spatial Patterns and Defensible Space Drivers—Hypothesis Testing

General Hypothesis: The attributes of the defensible space concept (zones of influence, natural surveillance, boundary demarcation (territorial markers), and territorial behavior) are drivers for the emerging cluster patterns at Zaatari Camp.

4.2.1. Hypothesis 1: Zone of Influence

This hypothesis proposes that the physical clustering of households is significantly influenced by zones of influence. Notably, 84% of the respondents perceive their courtyards as extensions of their homes.

ANOVA Results (Table 4)

Table 4.

ANOVA: zones of influence.

Table 4.

ANOVA: zones of influence.

| Variable | Sum of Squares | Df | Mean Square | F | p | Effect Size (η2) |

|---|

| Space Extension | 12.17 | 3 | 4.06 | 4.36 | 0.006 | 0.12 |

| Stranger Identification | 17.98 | 3 | 5.99 | 7.39 | 0.001 | 0.18 |

| Private Use of Outdoors | 18.79 | 3 | 6.26 | 7.97 | 0.001 | 0.20 |

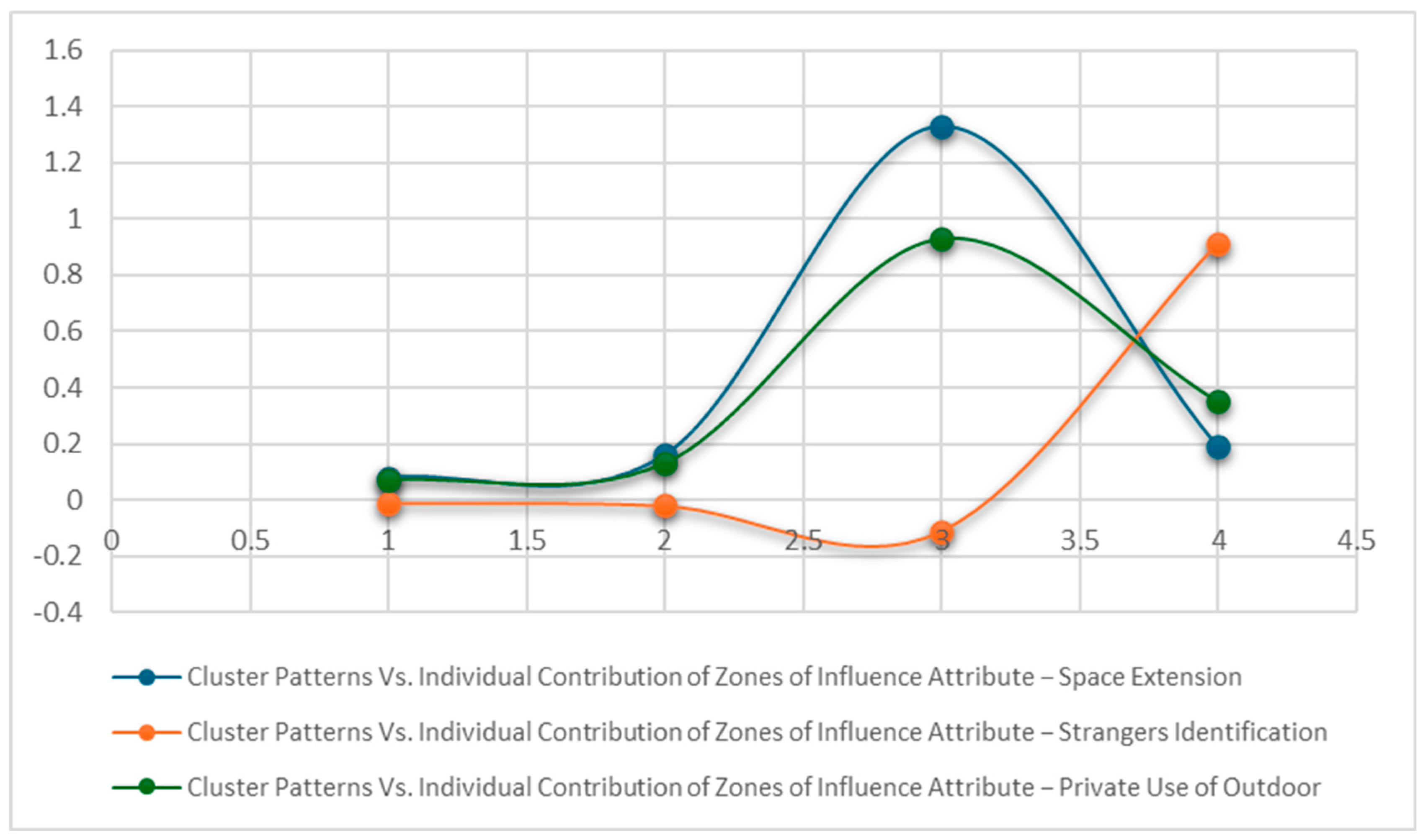

Interpretation: These significant results highlight that clustered households strongly regard courtyards as extensions of their homes, which enhances their territorial control. However, when examining the predictive power through regression analysis, the following is observed:

Regression Analysis (Table 5)

Although significant differences were observed in the ANOVA tests, the regression analysis indicated a weaker relationship overall:

The overall model demonstrated a weak predictive power, with no significant collective effect of zones of influence variables on cluster patterns: F (3, 98) = 1.91, p = 0.13.

Individual variables showed a weak predictive power, see

Table 6. The regression model in

Figure 6 reflects the relationship.

Table 5.

Model Summary—zones of influence.

Table 5.

Model Summary—zones of influence.

| Model | Sum of Squares | Df | Mean Square | F | p |

|---|

| Regression | 1.46 | 3 | 0.49 | 1.91 | 0.13 |

| Residual | 24.89 | 98 | 0.25 | | |

| Total | 26.35 | 101 | | | |

Despite the findings in the ANOVA suggesting notable differences, the regression model indicates that these variables collectively have a weak predictive power regarding cluster patterns (F (3, 98) = 1.91, p = 0.13), suggesting that, while individuals perceive these aspects as influential, they do not significantly contribute to actual variances in community clustering.

Beta coefficients in the regression analysis express the magnitude and direction of the relationship between predictor variables and the dependent variable. The following involves a detailed interpretation of the Beta values from

Table 6:

Space Extension (Beta = 0.16): The positive sign indicates a direct relationship; as the perception of outdoor space as an extension of the home increases, clustering behavior is also expected to increase. This suggests that individuals who consider their external spaces as extensions of their living areas are likely to feel a stronger connection to their community, potentially leading to more clustered living arrangements.

The Beta value of 0.16 indicates that for every one unit increase in the perception of space extension, clustering behavior is expected to increase by 0.16 units. This suggests a relatively moderate effect compared to other variables in the analysis.

- 2.

Stranger Identification (Beta = −0.02): The negative sign implies an inverse relationship; as the ability to identify strangers increases, clustering behavior slightly decreases. However, this effect is minimal and suggests that identifying strangers may not significantly influence how clustered households become.

The Beta value of −0.02 signifies that for every one unit increases in the ability to identify strangers, clustering behavior decreases marginally by 0.02 units. This indicates a very weak effect, suggesting that this factor has little to no practical influence on clustering dynamics.

- 3.

Private Use of Outdoors (Beta = 0.13): This positive Beta value indicates that greater private use of outdoor spaces is associated with increased clustering behaviors. It suggests that, as individuals can utilize their outdoor spaces for private activities, they tend to cluster more with their neighbors.

The Beta value of 0.13 indicates that for every one unit increase in the private use of outdoor spaces, clustering behavior is expected to increase by 0.13 units. This reflects a relatively small but positive association, highlighting that outdoor privacy can contribute to community ties.

Positive Beta values (0.16 for Space Extension and 0.13 for Private Use of Outdoors) indicate a direct relationship with clustering patterns, suggesting that greater perceptions of space and private usage are linked to more clustered households.

A negative Beta value (−0.02 for Stranger Identification) reflects a negligible inverse relationship, suggesting that the ability to identify strangers does not have a meaningful impact on clustering.

Overall, while the directions of these Beta values provide insights into the nature of associations among the variables, their small to moderate magnitudes alongside high p-values indicate that other factors may also play a critical role in shaping clustering behaviors in the community.

Collectively, the regression results for the zones of influence variables indicate the following:

Space Extension emerges as the most promising predictor among the three, but it does not reach statistical significance, meaning that it may not reliably influence clustering patterns.

Stranger Identification shows no appreciable impact on clustering, supported by its low p-value and Beta value indicating very weak effects.

Private Use of Outdoors has a slight positive association, but similarly lacks statistical significance, suggesting that the relationship could be incidental rather than causal.

In summary, while some relationships appear to exist, none of the factors provide a strong predictive power regarding clustering behavior in Zaatari Camp, as indicated by the absence of statistical significance across the measured variables. Future research may need to explore other potential drivers for clustering in this context.

Conclusion: Refugees in clustered patterns perceive outdoor spaces as extensions of their homes, identify strangers more effectively, and use courtyards for private activities. However, these factors collectively do not strongly predict cluster patterns.

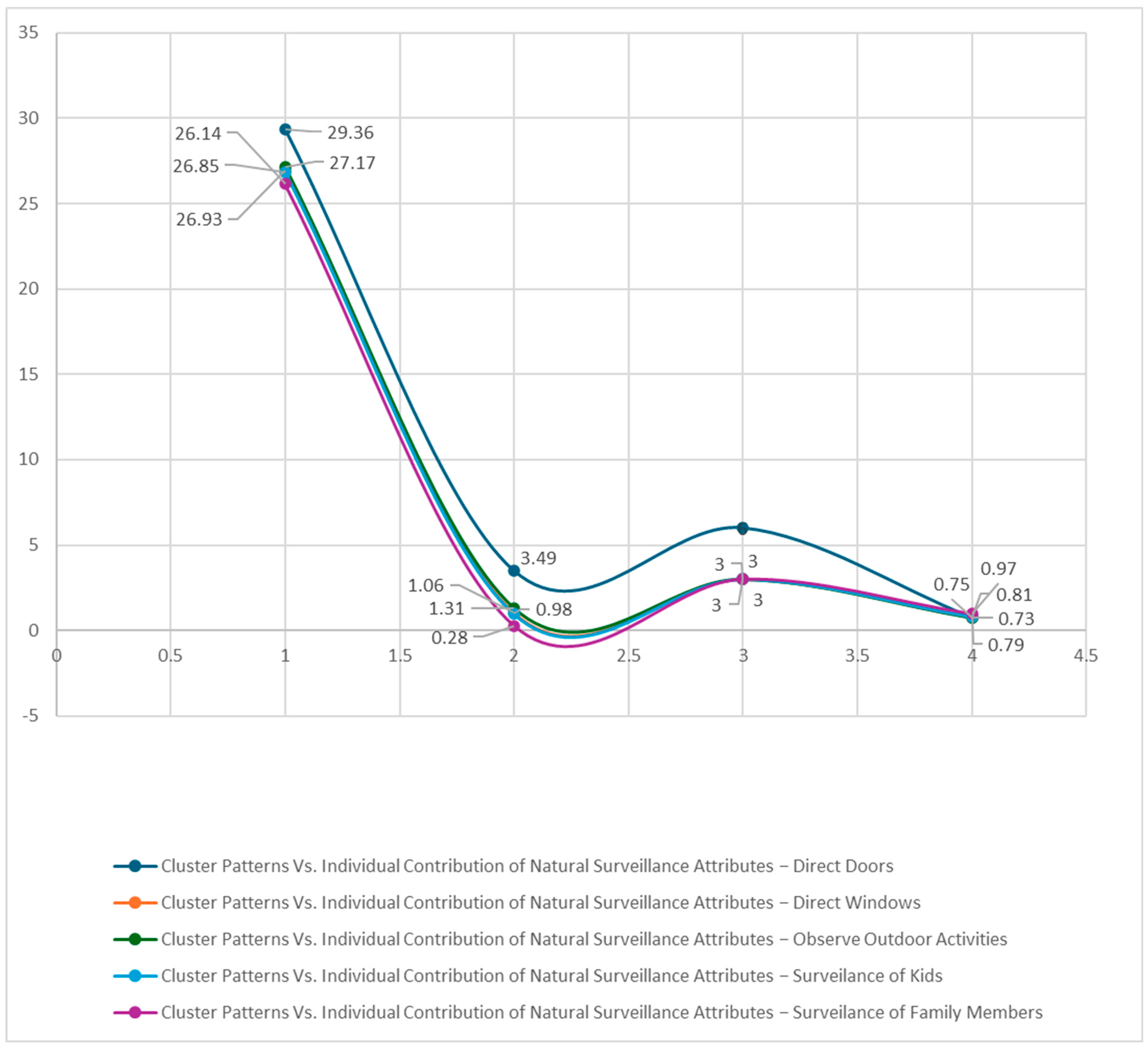

4.2.2. Hypothesis 2: Natural Surveillance

To assess the influence of natural surveillance on cluster patterns, chi-square tests were conducted (

Table 7). This hypothesis posits that natural surveillance significantly affects cluster patterns. The chi-square tests were analyzed, particularly focusing on the visibility provided through architectural features.

Direct Windows (χ2 (3) = 11.34, p = 0.01): This suggests that windows facing courtyards enhance residents’ perceived control over their outdoor spaces, fostering a sense of safety and security.

Observe Outdoor Activities (χ2 (3) = 12.47, p = 0.006): The ability to monitor activities in common areas promotes community surveillance, further supporting safety perceptions.

However, Direct Doors (p = 0.98) and the surveillance of family members lack a significant contribution to the understanding of spatial dynamics.

Table 7.

Chi-square tests on natural surveillance.

Table 7.

Chi-square tests on natural surveillance.

| Variable | Pearson Chi-Square | Df | p |

|---|

| Direct Windows | 11.34 | 3 | 0.01 |

| Observing Outdoor Activities | 12.47 | 3 | 0.006 |

| Direct Doors | 1.23 | 6 | 0.98 |

| Surveillance of Kids | 3.88 | 3 | 0.28 |

| Surveillance of Family Members | 3.88 | 3 | 0.28 |

Nominal Regression Analysis (Table 8 and Table 9):

Examining the overall impact of natural surveillance: The regression model indicates no significant overall effect from natural surveillance attributes (

p = 0.25,

Table 8). The regression model in

Figure 7 reflects the relationship.

Table 8.

Nominal regression—cluster pattern by natural surveillance.

Table 8.

Nominal regression—cluster pattern by natural surveillance.

| −2 Log Likelihood | Chi-Square | Df | p |

|---|

| 25.87 | 21.52 | 18 | 0.25 |

The likelihood ratio tests corroborate that no significant predictors emerged for the attributes examined (

Table 9).

Table 9.

Likelihood ratio—cluster pattern by natural surveillance.

Table 9.

Likelihood ratio—cluster pattern by natural surveillance.

| Variable | −2 Log Likelihood of Reduced Model | Chi-Square | Df | p |

|---|

| Direct Doors | 29.36 | 3.49 | 6 | 0.75 |

| Direct Windows | 26.93 | 1.06 | 3 | 0.79 |

| Observing Outdoor Activities | 27.17 | 1.31 | 3 | 0.73 |

| Surveillance of Kids | 26.85 | 0.98 | 3 | 0.81 |

| Surveillance of Family Members | 26.14 | 0.28 | 3 | 0.97 |

Conclusion: While visibility from direct windows and engagement in monitoring outdoor activities aid in creating community vigilance, these aspects collectively do not significantly contribute to the prediction of clustered patterns.

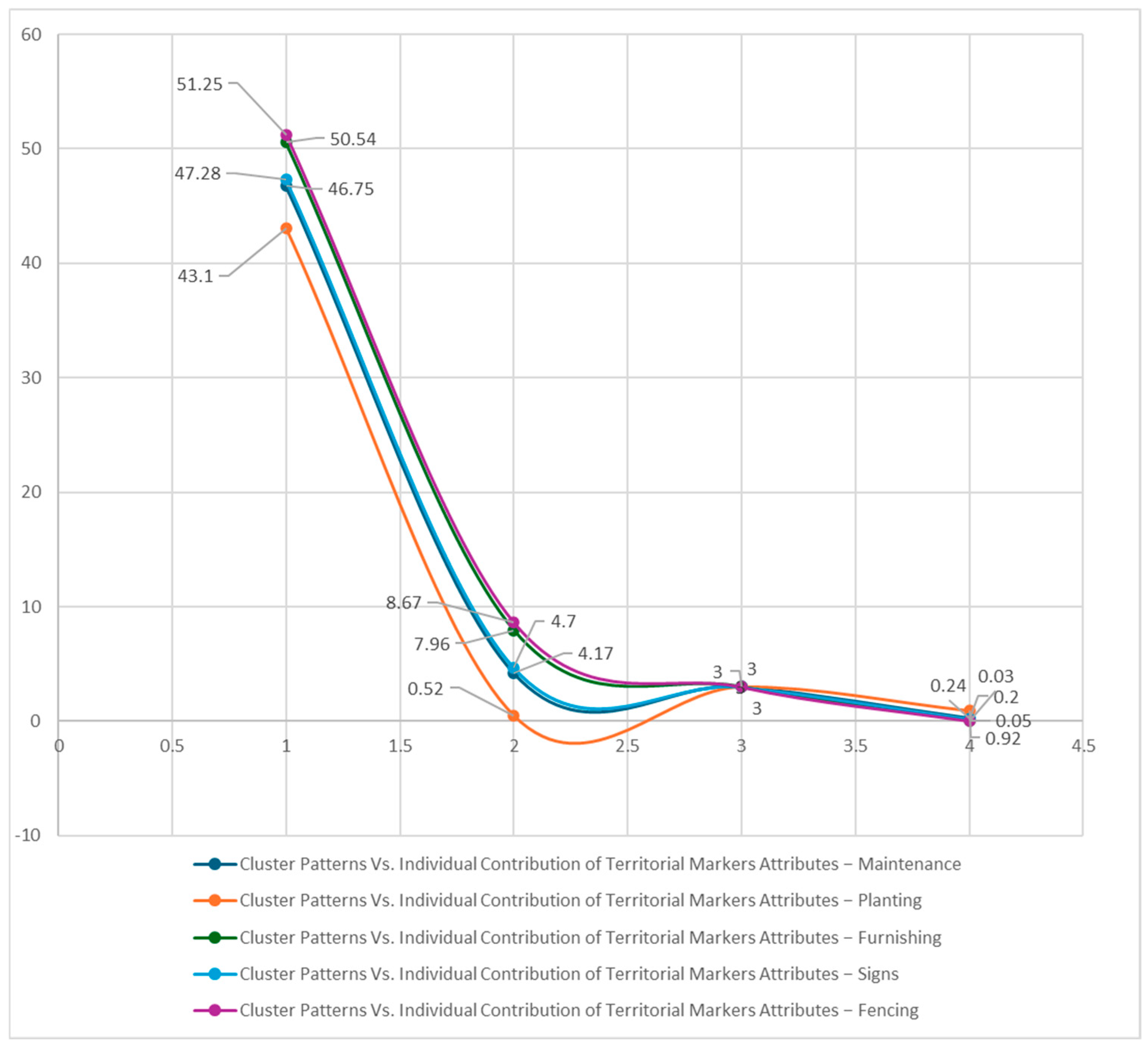

4.2.3. Hypothesis 3: Boundary Demarcation

The impact of boundary demarcation via territorial markers on cluster patterns was examined through chi-square tests (

Table 10), as follows:

The associations for Furnishing (χ2 (3) = 8.03, p = 0.05) and Fencing (χ2 (3) = 8.56, p = 0.04) are significant, indicating that residents utilize physical structures to delineate their space, enhancing their perceived territoriality.

Other markers like maintenance, planting, and signs do not show significant contributions, indicating that not all forms of boundary markers are equally effective.

Table 10.

Chi-square test—boundary demarcation (territorial markers).

Table 10.

Chi-square test—boundary demarcation (territorial markers).

| Variable | Pearson Chi-Square | Df | p |

|---|

| Furnishing | 8.03 | 3 | 0.05 |

| Fencing | 8.56 | 3 | 0.04 |

| Type of Fencing | 8.95 | 6 | 0.18 |

| Maintenance | 5.27 | 3 | 0.15 |

| Planting | 1.15 | 3 | 0.77 |

| Signs | 5.30 | 3 | 0.15 |

Nominal Regression

There was a significant overall effect of territorial markers (χ

2 = 28.06,

p = 0.02) (

Table 11). Territorial markers collectively predicted cluster patterns. However, the regressions model in

Figure 8 reflects the relationship.

Conclusion: Physical boundaries (fencing) and symbolic markers (furnishing) substantively reinforce territorial claims and effectively differentiate cluster patterns within Zaatari Camp, see

Table 12.

4.2.4. Hypothesis 4: Territorial Behavior

The fourth hypothesis explores whether territorial behavior affects cluster patterns. The ANOVA results highlight that there are no significant differences (

p > 0.05) across all assessed attributes (privacy control, territorial control, and defense). This suggests that territorial behaviors do not influence the nature of spatial arrangements within clustered households, see

Table 13.

Regression Analysis (Table 14)

Regression analysis echoes these findings, showing no significant contribution from territorial behavior variables to predicting cluster patterns: F (5, 96) = 0.54,

p = 0.75 (

Table 14).

Table 14.

Regression—territorial behavior.

Table 14.

Regression—territorial behavior.

| Model | Sum of Squares | Df | Mean Square | F | p |

|---|

| Regression | 0.72 | 5 | 0.14 | 0.54 | 0.75 |

| Residual | 25.64 | 96 | 0.27 | | |

| Total | 26.35 | 101 | | | |

Conclusion: Territorial behaviors, including perceived privacy and territorial control, do not significantly influence the spatial arrangements within the camp.

4.2.5. Overall Research Model

When assessing the combined influence of all four hypotheses (zones of influence, natural surveillance, boundary demarcation, and territorial behavior), the overall regression model indicated no significant predictive power, as follows: F (5, 96) = 1.759,

p = 0.12 (

Table 15).

Key Drivers

Zones of Influence emerged as the strongest predictor with F = 9.09,

p = 0.00 (

Table 16).

Natural Surveillance had marginal significance (

p = 0.07) (

Table 16).

The associations for Furnishing (χ2 (3) = 8.03, p = 0.05) and Fencing (χ2 (3) = 8.56, p = 0.04) were significant, indicating that residents utilized physical structures to delineate their space, enhancing their perceived territoriality.

Other markers like Maintenance, Planting, and Signs did not show significant contributions, indicating that not all forms of boundary markers were equally effective.

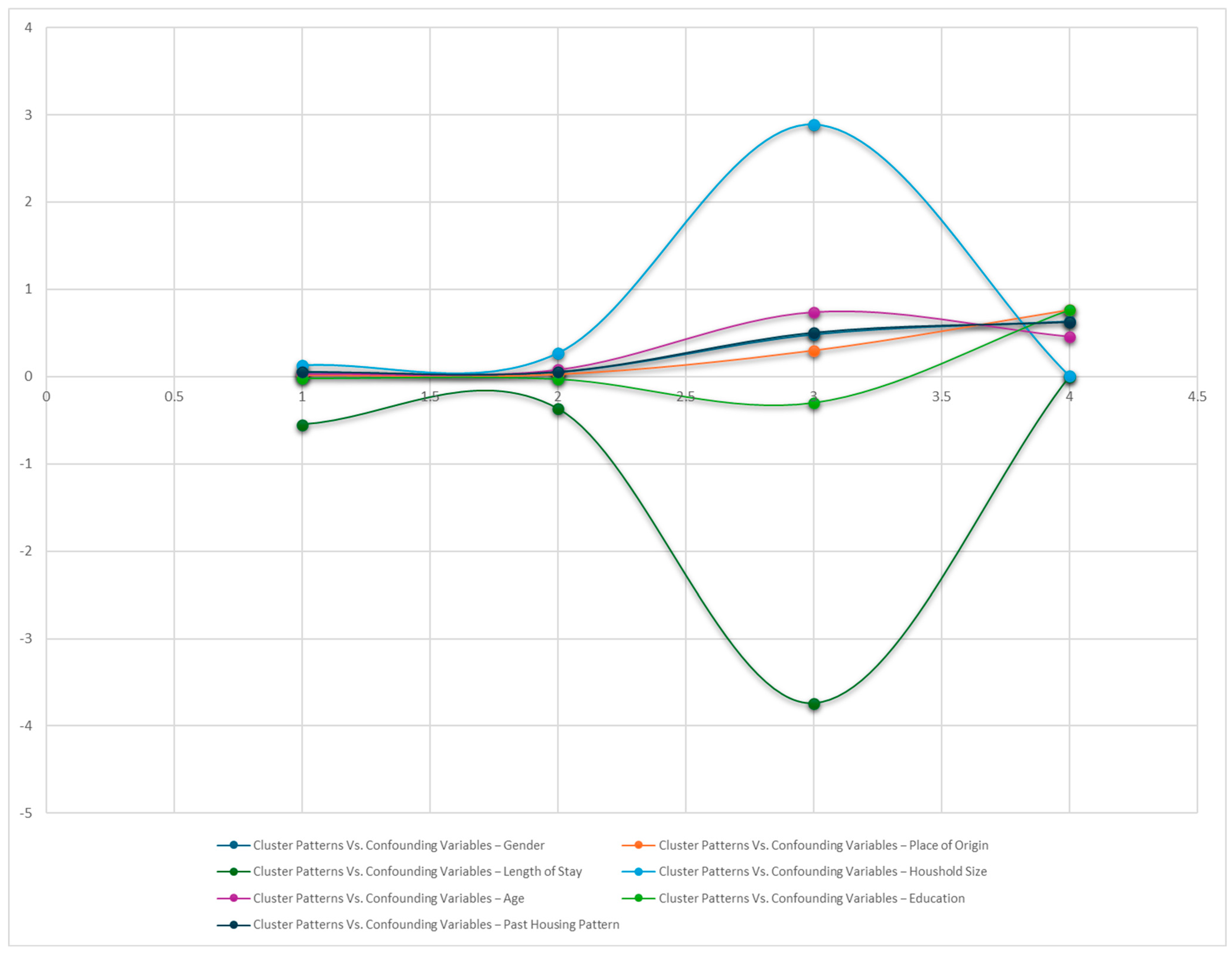

4.2.6. Analysis of Confounding Variables

Analyses of confounding variables indicate notable influences on cluster patterns, as follows:

Significant Confounders (Table 17)

Household size (F (3, 98) = 4.22, p = 0.008) significantly affects cluster patterns. Larger household sizes correlate with denser clustering, potentially impacting social interactions and resource use.

Place of origin and length of stay are also significantly associated with clustering (χ2 = 106.29, p < 0.01 and χ2 = 11.36, p = 0.08, respectively).

Table 17.

ANOVA—confounding variables.

Table 17.

ANOVA—confounding variables.

| Variable | Sum of Squares | Df | Mean Square | F | p |

|---|

| Household Size | 12.68 | 3 | 4.23 | 4.22 | 0.008 |

| Age | 1.28 | 3 | 0.43 | 0.25 | 0.86 |

Non-Significant Confounders (Table 17 and Table 18)

Variants like age, gender, education, and past housing experience do not show significant correlations with clustered patterns.

Table 18.

Chi-square test—confounding variables.

Table 18.

Chi-square test—confounding variables.

| Variable | Pearson Chi-Square | Df | p |

|---|

| Length of Stay | 102.10 | 6 | 0.00 |

| Place of Origin | 106.29 | 9 | 0.00 |

| Gender | 0.45 | 3 | 0.48 |

| Education | 9.57 | 9 | 0.39 |

Regression Model

Overall, the model is significant (

Table 19). Contributing factors in the model are household size and length of stay (

Table 20). However, the regressions model in

Figure 9 reflects the relationship.

Table 20 provides detailed information about the contribution of each individual confounding variable to the regression model.

Beta coefficients indicate the relative influence of each predictor variable in the model, adjusted for variance among variables.

Household Size (Beta = 0.27): This indicates a relatively strong positive effect among the variables, showing that household size is a key factor in predicting clustering.

Length of Stay (Beta = −0.37): The negative value suggests that an increasing duration spent living at the camp is inversely related to clustering, reinforcing the notion of diminished community ties over time.

Conclusion: The regression analysis in

Table 19 and

Table 20 provides critical insights into the contributions of various confounding factors to the patterns observed in Zaatari Camp. The statistically significant influences of Household Size and Length of Stay highlight the importance of these variables in understanding community dynamics, suggesting that larger households tend to cluster more while a longer duration can lead to individualistic spatial arrangements. Conversely, factors such as gender, age, place of origin, education, and past housing experience appear to exert minimal influence on clustering behaviors.

This detailed statistical reporting and interpretation illuminates the interactions between various spatial patterns and the factors influencing clustered community dynamics within Zaatari Camp, providing critical insights for researchers and policymakers in humanitarian settings.

4.3. Major Outcomes

Major Outcomes of the Analysis for all hypothesis testing:

General Hypothesis Validation: The overarching hypothesis that attributes of the defensible space concept (zones of influence, natural surveillance, boundary demarcation, and territorial behavior) influence clustering patterns in Zaatari Camp received mixed support. While some relationships were indicated, not all hypotheses demonstrated a strong predictive power.

Zones of Influence: Significant differences were found in how various cluster patterns perceived outdoor spaces as extensions of homes. While connections were noted (F = 4.36, p = 0.006 for space extension), the regression analyses revealed a weak overall predictive power for clustering patterns related to zones of influence variables (F = 1.91, p = 0.13). Specifically, while Space Extension showed a positive relationship (B = 0.08, p = 0.19), it was not statistically significant.

Natural Surveillance: Chi-square tests highlighted that physical features such as direct windows and the ability to observe outdoor activities were associated with clustering (χ2 = 11.34, p = 0.01, and χ2 = 12.47, p = 0.006, respectively). However, when modeled through regression analysis, no significant overall effect of natural surveillance attributes was found (p = 0.25). This indicates that while visibility may have correlated with clustering, it did not significantly predict it.

Boundary Demarcation: Chi-square tests indicated strong associations for Furnishing (χ2 = 8.03, p = 0.05) and Fencing (χ2 = 8.56, p = 0.04), suggesting that both physical and symbolic markers played roles in reinforcing territorial claims. The nominal regression further supported this view, with an overall significant effect (χ2 = 28.06, p = 0.02), showcasing that boundaries helped to differentiate clustered households.

Territorial Behavior: The ANOVA results indicated no significant differences in perceived privacy, territorial control, or defense strategies across grid and cluster patterns (p > 0.05). Additionally, regression analysis (F = 0.54, p = 0.75) revealed that territorial behavior variables did not effectively predict clustering patterns. This suggests that perceived control over space had a minimal influence on household arrangements.

Overall Research Model: The combined analysis of all hypotheses yielded no significant predictive power (F = 1.76, p = 0.12). Notably, Zones of Influence showed the strongest association among individual contributions (F = 9.09, p = 0.00), whereas other factors such as Natural Surveillance and Territorial Markers exhibited only marginal significance, indicating a weaker contribution to cluster dynamics.

Confounding Variables: Significant influences were found for Household Size (F = 4.22, p = 0.008) and Length of Stay (χ2 = 11.36, p = 0.08) on clustering patterns, emphasizing the importance of these factors in understanding the social composition of the camp. Conversely, other demographic factors like age, gender, and education had minimal predictive power.

Conclusion: This comprehensive analysis reveals that while certain aspects of defensible space contribute to understanding the clustering patterns in Zaatari Camp, many variables exhibit weak or non-significant influences. The most significant findings revolve around how household size and length of stay play critical roles in shaping community dynamics. Consequently, future interventions aimed at fostering social integration and improving community structures should prioritize these factors to enhance living conditions in refugee settings.

6. Conclusions

This comprehensive study provides an in-depth analysis of how defensible space theory can be effectively adapted to meet the unique needs of refugee contexts like Zaatari Camp. It elucidates how refugees interpret and manipulate spatial principles to forge socially cohesive environments, transforming standard grid layouts into dynamic clusters that are better suited to their cultural practices and survival needs. This transformation reflects acts of resilience rather than deviations from standard urban designs, urging planners worldwide to recognize and integrate such organic adaptations into formal planning frameworks.

6.1. Key Contributions

Cultural identity here refers to refugees’ recreation of socio-spatial practices from their regions of origin (e.g., clustered layouts around communal spaces). These adaptations not only reinforce communal bonds, but also enhance safety through natural surveillance and territorial markers, aligning with SDG 11’s goals for inclusive urban environments.

Socio-Cultural Adaptations: Refugees’ spatial modifications are driven primarily by socio-cultural needs rather than mere survival. The reinterpretation of defensible space principles—adapting them to prioritize communal identity and social cohesion over individual ownership—illustrates this central finding. The resultant clustered layouts facilitate communal living and reinforce social ties disrupted by displacement.

Redefining Defensible Space for Refugees: Traditional defensible space principles emphasize individual control and ownership. However, in refugee settings, these principles must be redefined to emphasize communal identity and shared responsibility. Refugee communities at Zaatari employ symbolic markers and shared spaces as tools for reinforcing group identity and sustaining cultural practices, aligning with broader traditions over Western individualism.

Alignment with the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs): The study’s findings directly relate to several SDGs, particularly SDG 11 (Sustainable Cities and Communities), which emphasizes the importance of inclusive, safe, and sustainable urban environments. By prioritizing community cohesion, cultural expression, and resilience among refugees, this research contributes to the broader goal of creating sustainable urban settlements, even amid displacement. Additionally, the attention paid to gender dynamics and safety within the camp aligns with SDG 5 (Gender Equality), advocating for environments that ensure the security and empowerment of vulnerable populations.

6.2. Recommendations for Stakeholders

For Humanitarian Organizations: Engage in participatory design processes that integrate refugee perspectives into camp planning. This ensures that such designs not only prioritize immediate survival needs, but also align with longer-term aspirations for community cohesion, cultural expression, and social stability.

For Policy Makers: Rethink existing policies regarding land rights and camp governance to facilitate greater autonomy for refugees and support their efforts to reclaim agency over their surroundings.

For Designers and Urban Planners: Implement flexible, culturally sensitive designs that encourage organic clustering. This includes developing communal living arrangements that reflect refugees’ cultural norms and values.

Lessons from informal settlements [

17] suggest that modular designs—allowing for incremental upgrades and communal input—could mitigate the tensions in Zaatari between institutional efficiency and refugee needs.

6.2.1. Integration of Socio-Cultural Values

Camp planners must consider the socio-cultural values integral to refugees’ worldviews in all planning aspects. This involves creating decentralized clusters with communal interaction zones, leveraging natural surveillance by orienting dwellings towards communal spaces, and actively engaging refugees in participatory planning efforts to ensure that spatial designs resonate with their cultural realities and needs.

6.2.2. Implications for Future Planning

This study strongly advocates for a context-sensitive approach to refugee camp planning. Traditional urban frameworks should give way to flexible strategies that marry spatial planning with socio-cultural understanding. Adaptive infrastructure capable of evolving with changing conditions can significantly enhance community resilience.

As demonstrated in Azraq Camp [

28], integrating refugee-led environmental health initiatives into camp planning can enhance both sustainability and self-reliance—key priorities for SDG 11.

6.3. Future Research Directions

Future research should aim to broaden the scope beyond Zaatari to include a range of refugee camps across diverse cultural settings. Such studies should consider the following:

Longitudinal Studies: Conducting longitudinal research would provide deeper insight into the dynamic evolution of spatial adaptations over time, shedding light on how temporary adjustments might solidify into permanent structures and practices.

Comparative Analyses: Investigating different camps across various regions will offer comparative insights, highlighting unique and shared adaptations across differing cultural and environmental contexts. This could lead to a better understanding of the universality and context specificity of spatial adaptation strategies.

Participatory Research Methods: Future research should employ participatory methodologies that actively involve refugees in the research process. This will ensure that findings reflect the lived realities of camp residents and that recommendations are grounded in the actual experiences and needs of the communities studied.

Exploration of Gender-Specific Needs: Further studies could explore how spatial adaptations address or fail to meet gender-specific needs in refugee camps, providing insights into how spaces can be designed to ensure safety and accessibility for all genders.

6.4. Study Limitations

This study acknowledges several limitations that may impact the findings. Firstly, its cross-sectional design captures a single time point, which limits our understanding of the ongoing spatial dynamics within Zaatari Camp. Additionally, the cultural diversity among refugee populations may affect the generalizability of the results, highlighting the need for more context-specific analyses.

Moreover, reliance on self-reported data introduces potential biases stemming from personal perceptions. Future research could address this concern by employing mixed methods approaches that incorporate both qualitative and quantitative data, thus enhancing the reliability and depth of the analysis.

In conclusion, the study emphasizes the necessity for holistic and culturally sensitive planning strategies in refugee contexts. By moving beyond traditional urban planning paradigms, humanitarian planners can create responsive interventions that align spatial design with the cultural support systems of refugees. As refugee crises persist, integrating these insights will be crucial for developing more effective, empathetic, and sustainable solutions in global humanitarian efforts.

Specific Limitations

Context-Specific Findings: The focus on Zaatari Camp may limit the applicability of the results to other refugee contexts. Future studies should examine a broader range of camps globally to capture diverse adaptations and cultural nuances.

Self-Reported Data Biases: The dependence on self-reported measures may introduce biases based on individual perceptions. Implementing mixed methods approaches in future research could provide deeper insights into the dynamics of refugee experiences.

Temporal Dynamics: The cross-sectional design restricts the ability to track the evolution of spatial dynamics over time. Longitudinal studies are recommended to capture how adaptations develop and change in response to prolonged displacement.