Redefining Project Management: Embracing Value Delivery Offices for Enhanced Organizational Performance

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Research Background

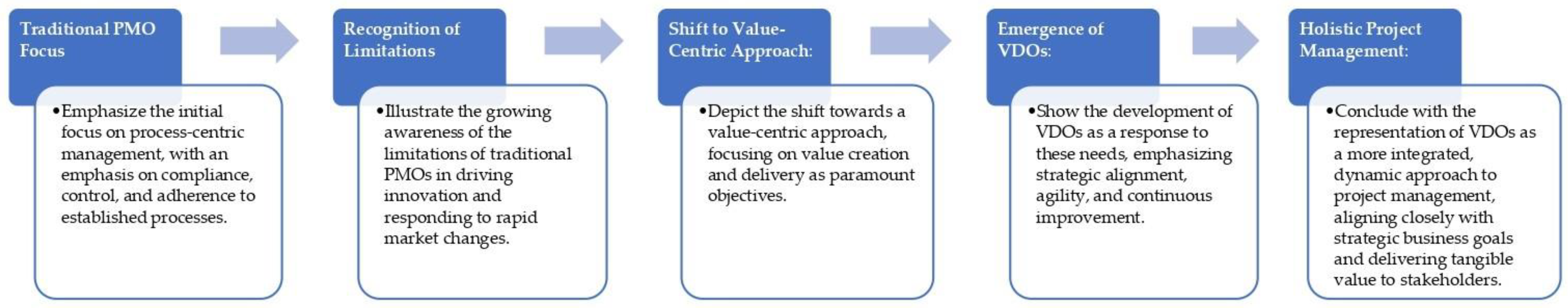

2.1. Overview of Project Management Offices (PMOs) and Their Traditional Role

2.2. Introduction to the Concept of the Value Delivery Office (VDO) and Its Emergence

2.3. Gaps and Limitations in Existing Research

3. Theoretical Framework

3.1. Exploring Theories and Models of Value Creation

- Economic Value: This aspect of value creation focuses on the tangible, monetary benefits generated by projects. Economic value theory emphasizes measurable outcomes like return on investment (ROI), cost savings, and revenue enhancement, which are traditional metrics of project success [35].

- Functional Value: This pertains to the practical and utilitarian aspects of project outcomes. Functional value is measured in terms of the utility, quality, and efficiency that projects deliver, contributing to the operational effectiveness of an organization.

- Social Value: This dimension addresses the impact of projects on society and communities. Social value creation involves considerations like corporate social responsibility (CSR), ethical practices, and community engagement, reflecting a broader societal impact beyond the organization’s immediate objectives [36].

- Perceived Value: This concept relates to stakeholders’ perceptions of the value delivered by projects. Perceived value is subjective and can significantly influence stakeholder satisfaction and loyalty [37]. It underscores the importance of aligning project outcomes with stakeholder expectations and experiences.

- Cultural Value: This encompasses the values, beliefs, and norms influenced by organizational culture. Projects aligned with cultural values foster a sense of belonging and purpose among team members, enhancing motivation and engagement [38].

- Personal Value: Personal value refers to the individual benefits and satisfaction derived by stakeholders, including employees, customers, and other partners [39]. It highlights the importance of addressing individual needs and preferences in project management.

- Strategic Value: Strategic value involves aligning projects with the long-term goals and vision of the organization [40]. It ensures that project outcomes contribute to the broader strategic objectives, facilitating sustainable growth and competitive advantage.

- Intrinsic Value: Intrinsic value refers to the inherent worth of project outcomes, independent of external measures [41]. This includes aspects like innovation, knowledge creation, and skill development, which may not have immediate tangible benefits but are crucial for long-term organizational resilience.

- Sustainable Value: This value refers to the creation of value through practices that ensure long-term benefits for both the organization and society. It emphasizes a balance between economic growth and the environmental and social aspects of operations [42]. This approach integrates principles of sustainability into value creation, considering factors like environmental stewardship, social responsibility, and economic viability. Sustainable value is about creating a positive impact that lasts beyond immediate gains, ensuring that the organization’s activities contribute to a healthier environment and society, while also being economically profitable. Table 2 summarizes the various theories and models of value creation.

3.2. How Value Creation Theories Underpin the Transition from PMOs to VDOs

- Economic and Functional Value: The emphasis on economic and functional value in VDOs aligns projects more directly with tangible business outcomes. Unlike PMOs, where the focus may be predominantly on adherence to process and budget, VDOs prioritize projects based on their potential to drive economic growth and functional efficiency, ensuring a more direct correlation between project execution and business performance.

- Social and Cultural Value: The consideration of social and cultural values in VDOs reflects a broader understanding of a project’s impact. VDOs extend the scope of project management to include societal benefits and alignment with organizational culture, thus fostering projects that not only benefit the business but also resonate with wider community values and internal organizational ethos.

- Perceived and Personal Value: By recognizing perceived and personal value, VDOs ensure that projects are closely aligned with stakeholder expectations and individual needs. This focus enhances stakeholder engagement and satisfaction, a crucial aspect often overlooked in traditional PMO settings, where the emphasis might be more on meeting predefined metrics than on stakeholder-centric outcomes.

- Strategic and Intrinsic Value: The integration of strategic and intrinsic value in the VDO framework ensures that projects are not just aligned with immediate business needs but also contribute to the long-term strategic goals and intrinsic worth of the organization. This approach facilitates innovation and long-term sustainability, moving beyond the often short-term, task-oriented focus of conventional PMOs.

4. Research Methodology

4.1. Data Collection Methods and Analysis Techniques

4.1.1. Data Collection Methods

Qualitative Data Collection

- Document Analysis: Reviewing organizational policies, historical project reports, and VDO implementation roadmaps.

- Observational Research: Examining meeting records and value-delivery tracking systems.

- Performance Evaluation: Analyzing pre- and post-transition project outcomes.

- Project Managers and PMO Leaders: Providing perspectives on governance, reporting structures, and strategic planning.

- Senior Executives: Offering insights into the organizational benefits and challenges of shifting to VDOs.

- Operational Staff: Assessing changes in project execution, collaboration, and performance measurement.

Quantitative Data Collection

- Project efficiency (measured by budget adherence and schedule compliance).

- Stakeholder satisfaction (assessed using Likert-scale feedback).

- Value realization (using ROI and performance-based KPIs).

Sampling Strategy

4.1.2. Analysis Techniques

Qualitative Analysis

- Eight Project Managers—To understand project-level execution challenges.

- Six Senior Executives—To explore strategic decision-making and governance shifts.

- Six Operational Staff Members—To assess workflow changes and adaptation to VDO structures.

“Our previous PMO structure was too rigid. With the VDO model, we now have greater flexibility to align projects with real business needs.”(Senior Project Manager, Construction Firm.)

“The biggest challenge was the mindset shift—moving from process adherence to value measurement.”(Executive Director, IT Services.)

Integrative Approach

- Qualitative data (interviews and case studies) provided in-depth insight into the organizational shift from PMOs to VDOs.

- Quantitative survey data validated qualitative themes by measuring scalability, impact, and statistical significance.

- Document analysis (internal project reports, financial data, and performance dashboards) cross-checked reported findings with actual organizational records.

4.1.3. Ensuring Validity and Reliability

- Pilot Testing: The survey instrument is pilot-tested with a small sample of respondents to ensure the clarity and relevance of the questions. Adjustments are made based on feedback to improve the instrument’s validity.

- Inter-Coder Reliability: Multiple coders are used in the thematic analysis of qualitative data to enhance reliability. Inter-coder reliability is assessed to ensure consistency in the coding process.

- Member Checking: Participants in the qualitative study are given the opportunity to review and confirm the accuracy of the transcriptions and interpretations of their interviews, ensuring the credibility of the findings.

5. Findings and Discussions

5.1. Key Findings Related to the Organizational Structure of Value Delivery Offices (VDOs)

- Integrated Organizational Structure: One of the most significant findings is that VDOs adopt a more integrated organizational structure compared to the often-siloed structure of traditional PMOs. This aligns with PMI’s emphasis on strategic alignment and cross-functional collaboration. This integrated structure allows VDOs to enhance agility and responsiveness to market dynamics [12].

- Centers of Excellence (CoEs): The establishment of specialized CoEs within VDOs emerged as a critical structural innovation. These CoEs—focused on areas such as Innovation, Business Analysis, and Agile Project Management—serve as hubs of expertise, providing guidance, best practices, and support to project teams. This finding reinforces PMI’s advocacy for knowledge management and continuous improvement but adds depth by illustrating how CoEs are specifically tailored to address the unique challenges of value-driven project management. For example:

- ○

- Innovation Center of Excellence: This CoE nurtures innovative ideas and approaches, ensuring that projects contribute to the organization’s innovative capabilities. This aligns with the recent literature on innovation management in project contexts [47].

- ○

- Business Analysis Center of Excellence: This unit offers expertise in analyzing business needs and ensuring that project outcomes align with these needs, addressing a gap often observed in traditional PMOs [48].

- ○

- Agile PMO Unit: Dedicated to implementing and promoting agile methodologies, this CoE enhances flexibility and responsiveness, reflecting the growing emphasis on agility in project management [49].

- Retention of Operational PMO Functions: While VDOs emphasize value delivery and strategic alignment, they often retain certain operational aspects of traditional PMOs. This hybrid approach ensures that projects adhere to established standards and methodologies while incorporating agile and innovative practices. This finding aligns with PMI’s recognition of the need for balance between structure and flexibility but provides new insights into how VDOs achieve this balance in practice.

- Focus on Value Streams: A defining characteristic of VDOs is their emphasis on value streams rather than merely project outputs. This approach ensures that projects contribute significantly to the organization’s value chain, enhancing overall business performance. This finding resonates with PMI’s Value Delivery Framework but extends it by demonstrating how VDOs operationalize value streams through specific structural and procedural adaptations.

- Contribution to Existing Knowledge: These findings collectively indicate a fundamental shift in the organizational structure and approach of VDOs compared to traditional PMOs. While the existing literature and methodologies, such as those from PMI, have highlighted the importance of strategic alignment, agility, and value delivery, this study provides empirical evidence of how these principles are implemented in practice. Specifically, the study contributes to the literature by the following means: (1) Demonstrating how VDOs operationalize cross-functional integration and strategic alignment in ways that go beyond traditional PMO structures. (2) Highlighting the role of specialized CoEs in fostering innovation, business analysis, and agile practices within a value-driven framework. (3) Illustrating how VDOs balance operational rigor with strategic flexibility, addressing a key challenge identified in both academic and practitioner literature. (4) Providing a detailed understanding of how value streams are prioritized and managed within VDOs, offering actionable insights for organizations seeking to enhance their project management practices.

- Operational and Traditional PMO Units: While emphasizing value delivery and strategic alignment, VDOs often retain certain aspects of traditional PMOs, especially in handling operational aspects of project management [50]. These units ensure that projects adhere to established standards and methodologies while also incorporating the agile and innovative practices endorsed by VDOs.

- Emphasis on Value Streams: VDOs are characterized by their focus on value streams rather than just project outputs [51]. This approach ensures that projects are not only completed efficiently but also contribute significantly to the organization’s value chain, enhancing overall business performance.

5.2. Role of Change Management in Transitioning from PMO to VDO

- Facilitating Cultural Shift: One of the primary roles of change management in the transition to VDOs is to facilitate a cultural shift within the organization. Moving from a PMO to a VDO often requires changes in mindset, attitudes, and behaviors, particularly in terms of prioritizing value delivery over traditional project metrics. Change management initiatives help in cultivating a culture that embraces innovation, agility, and continuous improvement, which are essential for the success of VDOs.

- Stakeholder Engagement and Communication: Effective communication and engagement strategies are vital in managing the transition. Change management involves keeping all stakeholders informed about the reasons for the transition, the benefits of VDOs, and the impact on their roles and responsibilities. Regular communication, workshops, and training sessions help in aligning stakeholders with the new approach and in addressing any concerns or resistance.

- Managing Transition Process: Change management plays a pivotal role in planning and overseeing the transition process. This includes setting realistic timelines, defining milestones, and establishing metrics to measure the progress of the transition. It also involves identifying and mitigating risks associated with the change, ensuring a smooth and orderly shift from PMO to VDO.

- Training and Skill Development: The study highlights the importance of training and skill development as part of change management. As VDOs often require new skills and competencies, particularly in areas like agile methodologies, business analysis, and innovation management, providing targeted training programs is crucial for equipping employees with the necessary tools to thrive in a VDO environment.

- Continuous Improvement and Feedback Loops: Change management in the context of VDOs is an ongoing process. Establishing feedback mechanisms to continuously gather insights from employees and stakeholders about the transition is essential. This feedback is used to make iterative improvements so that the VDO remains aligned with organizational goals and responsive to evolving project management needs.

5.3. Linking Results to Literature Review and Theoretical Framework

5.4. Methodological Foundations and Implications for Practice

5.5. Alignment of Findings with Research Objectives

5.5.1. Objective 1: Understanding the Challenges in PMOs That Necessitate a Shift to VDOs

- Rigid Governance Structures—PMOs focus heavily on compliance and process adherence, limiting adaptability. One project manager stated, “Our PMO was compliance-focused, leaving little room for adapting to changing business needs.”

- Limited Value Measurement—Traditional PMOs prioritize schedule and budget adherence but fail to measure the strategic impact of projects.

- Slow Decision-Making—Hierarchical decision-making slows down response times, reducing the ability to pivot based on emerging opportunities.

- Survey data (n = 120) confirmed these issues, with 78% of respondents agreeing that PMOs do not effectively measure project value beyond cost and time constraints.

5.5.2. Objective 2: Identifying Key Characteristics of an Effective VDO

- Value-Driven Performance Metrics—VDOs prioritize business impact over process compliance.

- Decentralized Governance—Decision-making is distributed across Value Delivery Teams (VDTs) for greater agility.

- Strategic Business Integration—Unlike PMOs, VDOs align projects directly with enterprise value goals.

- Hybrid Governance Models—Organizations blend PMI, PRINCE2, and Agile methodologies to create flexible project structures.

- Survey validation showed that 81% of organizations reported improved strategic alignment after implementing a VDO.

5.5.3. Objective 3: Assessing the Impact of VDOs on Project Performance

- Stakeholder Satisfaction increased by 24%.

- Project Success Rate improved by 18%.

- Innovation Adoption increased by 29%, reflecting better adaptability to market changes.

- Qualitative feedback further reinforced these results, with executives stating that VDOs facilitated faster decision-making and better resource optimization.

5.5.4. Objective 4: Introducing the VDMM for Guiding VDO Adoption

- Value Seeker—No formalized value measurement exists.

- Initiator—VDO structures exist, but metrics remain process-focused.

- Optimizer—Organizations align project goals with value-based performance metrics.

- Innovator—Advanced analytics and AI-driven performance assessments support project governance.

- Leader—A fully embedded VDO framework continuously evolves based on real-time value tracking.

- Survey analysis revealed that only 12% of organizations have reached the “Leader” maturity level, underscoring the need for more structured adoption strategies.

5.6. Explanation of the Value Delivery Maturity Model

- Value Seeker: This is the initial stage where organizations begin to recognize the importance of value delivery beyond traditional project management metrics. In this phase, there is an emerging awareness of the need for change, but structured approaches to value delivery are not yet fully established [57]. Organizations at this stage are exploring opportunities and starting to align their project management practices with broader business objectives.

- Value Initiator: At this stage, organizations start to implement basic frameworks for value delivery. There is a shift from traditional project management to more value-oriented practices, although these might still be in their infancy [58]. Initiatives at this stage often include setting up basic structures for VDOs and beginning to integrate value considerations into project selection and execution.

- Value Optimizer: Organizations in the Value Optimizer stage have established and are refining their value delivery processes [59]. There is a more systematic approach to integrating value into all project management activities, with established metrics for assessing value delivery. This stage is characterized by enhanced coordination between different units within the VDO and the broader organization.

- Value Innovator: This advanced stage is marked by a proactive approach to value creation. Organizations at this level not only deliver value efficiently but also innovate ways to enhance value delivery. This involves leveraging new technologies, methodologies, and strategic thinking to continuously improve and expand value delivery capabilities.

- Value Leader: The final stage of the VDMM is where organizations become leaders in value delivery. Here, value-oriented practices are deeply ingrained in the organizational culture and strategy [14]. These organizations are recognized for their exceptional ability to consistently deliver high value, set trends in project management, and influence best practices in their industry or sector.

5.7. Practical Implications for Organizations Considering the Shift to VDOs

- Organizational Culture and Mindset Change: One of the foremost implications is the need for a cultural and mindset shift within the organization [61]. Transitioning to a VDO requires moving beyond a focus on process compliance and project completion metrics to a broader emphasis on value creation and delivery. This shift requires organizations to adopt a culture focused on innovation, flexibility, and alignment with strategic goals.

- Enhanced Stakeholder Engagement: Adopting a VDO approach demands a more robust engagement with stakeholders [56]. Organizations must ensure that they understand and align with stakeholder needs and expectations, as the success of VDOs is heavily reliant on delivering tangible value to these stakeholders. This involves a more dynamic and interactive relationship with clients, partners, and internal teams.

- Resource Allocation and Training: The transition to VDOs often requires reallocation of resources and significant investment in training and development. Organizations need to equip their teams with the necessary skills and knowledge in areas such as agile methodologies, value assessment, and strategic project management. This investment is crucial for building the capabilities required to operate effectively in a VDO framework.

- Revised Metrics and Performance Indicators: Moving to a VDO model also implies a need to revise existing project management metrics and performance indicators. Success in a VDO is measured not just by project completion within time and budget but also by the value delivered to the organization and its stakeholders. This requires the development of new metrics that can effectively capture and quantify value delivery.

- Structural and Operational Adjustments: Organizations need to be prepared for structural and operational adjustments. This includes setting up new units or modifying existing ones, establishing Centers of Excellence for innovation and agile practices, and integrating these units seamlessly within the organization. The structural change also involves redefining roles and responsibilities to align with the VDO model [62].

- Long-term Strategic Focus: The shift to a VDO demands a long-term strategic focus, aligning project management with the organization’s strategic goals. Projects under a VDO are selected and managed based on their contribution to strategic objectives, requiring a more forward-looking and strategic approach to project management [54].

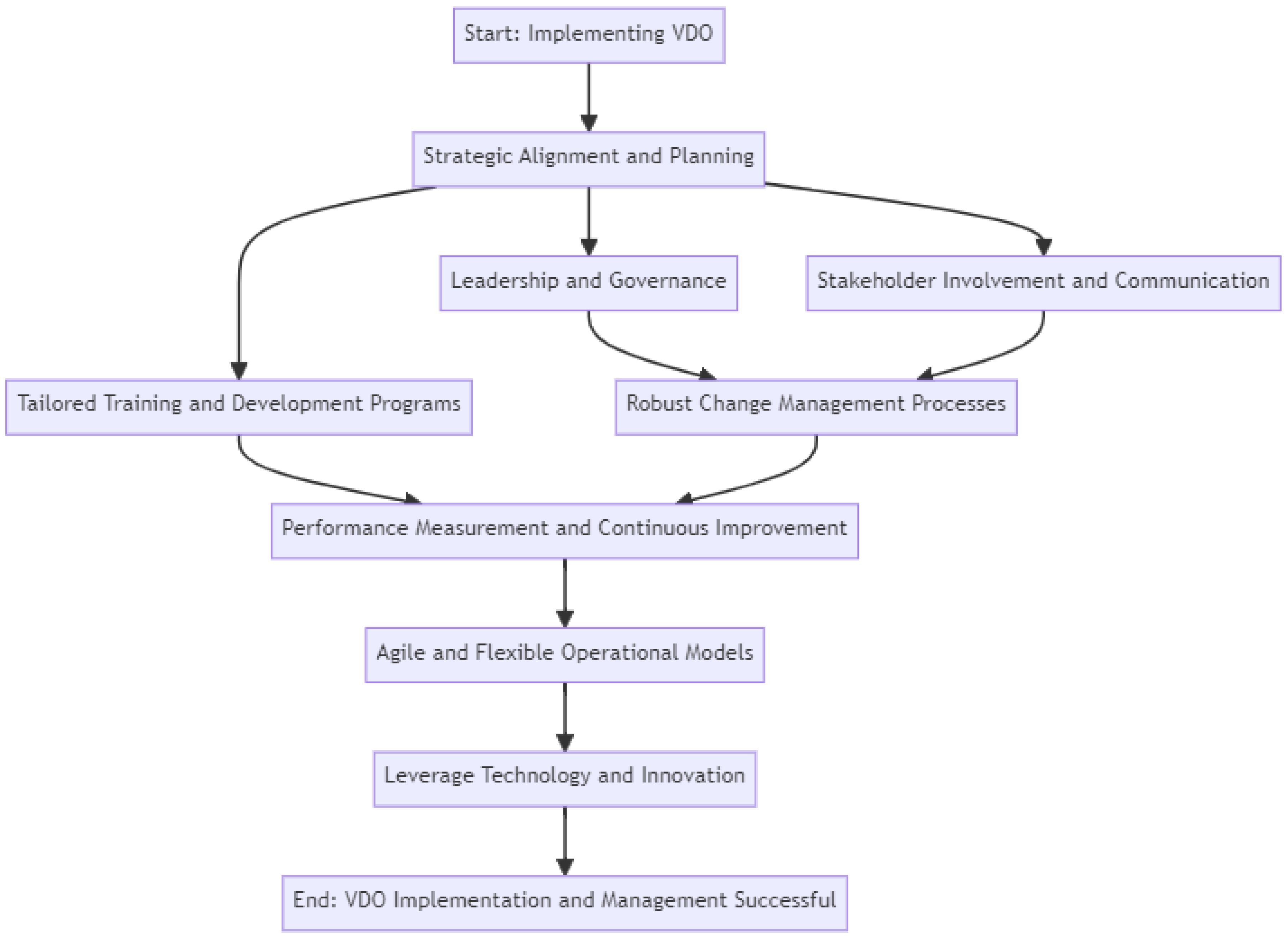

5.8. Recommendations for Implementing and Managing VDOs Effectively

- Strategic Alignment and Planning: Begin by ensuring that the VDO’s objectives are tightly aligned with the organization’s overall strategic goals. Develop a clear plan that outlines how the VDO will operate within the organization, including its role, responsibilities, and the value it is expected to deliver.

- Leadership and Governance: Establish strong leadership and governance structures for the VDO. This includes appointing leaders who understand both the traditional aspects of project management and the innovative aspects of value delivery. Leadership should also be responsible for setting the vision for the VDO and ensuring that it is effectively communicated and embraced throughout the organization.

- Stakeholder Involvement and Communication: Engage stakeholders early and continuously throughout the transition process. Keep communication channels open to ensure that feedback is received and acted upon. This involvement helps in managing expectations and mitigating resistance to change.

- Tailored Training and Development Programs: Invest in comprehensive training and development programs to equip staff with the necessary skills and knowledge. Focus on areas such as value assessment, agile methodologies, and strategic thinking. Ensure that the training is tailored to meet the specific needs of the VDO and its team members.

- Robust Change Management Processes: Implement robust change management processes to guide the transition. This includes managing the cultural shift, addressing resistance, and ensuring that the organization is ready to adopt new ways of working. Change management should be seen as an ongoing process, not a one-time event.

- Performance Measurement and Continuous Improvement: Develop new metrics and key performance indicators (KPIs) that are aligned with value delivery. Regularly review and adjust these metrics to ensure they remain relevant and effectively measure the performance of the VDO. Foster a culture of continuous improvement where feedback is actively sought and used to refine processes and approaches.

- Agile and Flexible Operational Models: Adopt an agile and flexible operational model within the VDO. This allows for quick adaptation to changes in the business environment and ensures that the VDO remains responsive to the evolving needs of the organization and its stakeholders.

- Leverage Technology and Innovation: Utilize technology and innovation to enhance the capabilities of the VDO. This includes adopting project management tools, data analytics, and other technological solutions that aid in value assessment and delivery.

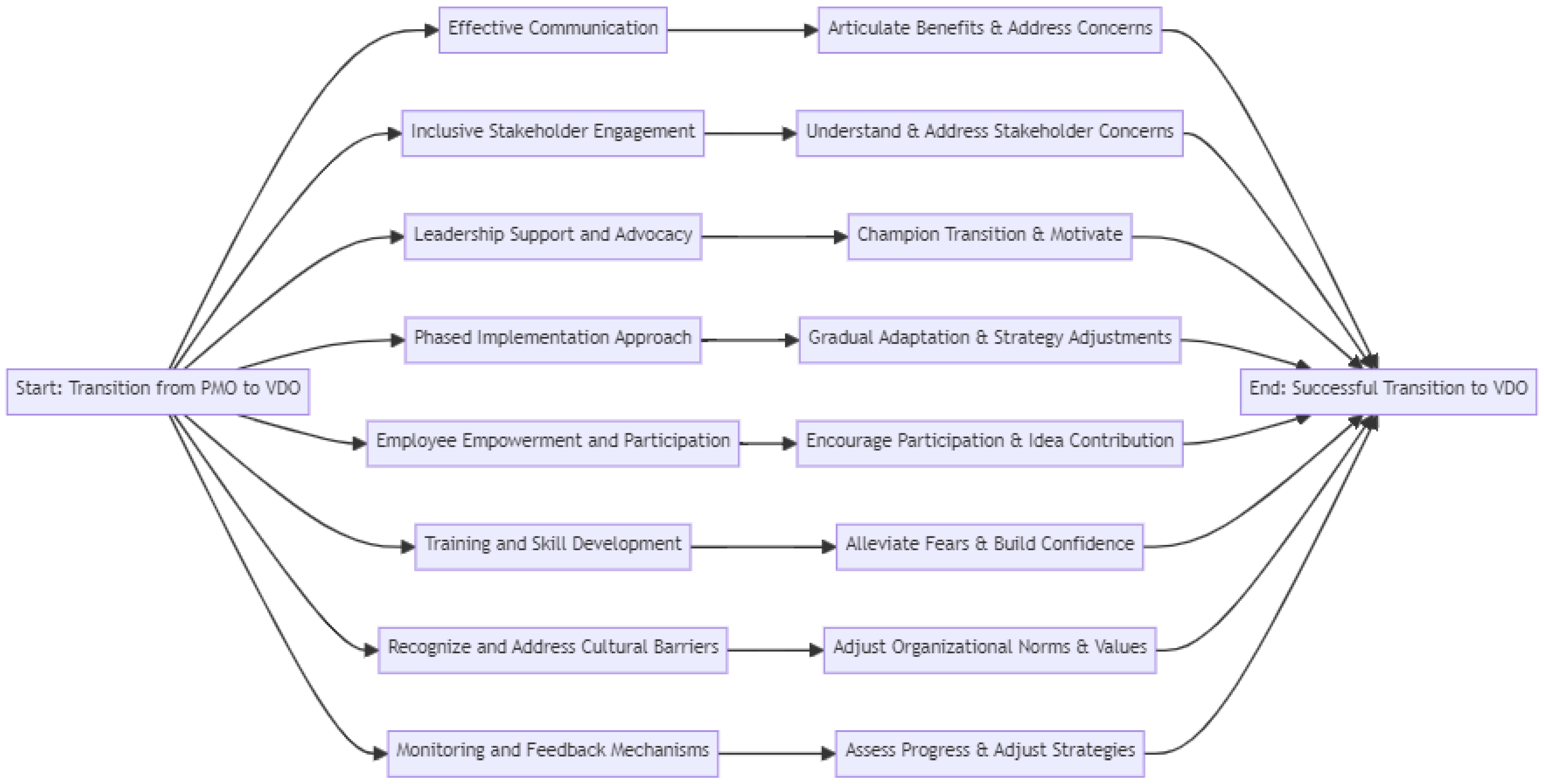

5.9. Strategies for Overcoming Resistance and Challenges During the Transition

- Effective Communication: Clear and consistent communication is vital in managing resistance to change (Sexton, 2014) [64]. Articulate the benefits of transitioning to a VDO, and address concerns transparently. Use a variety of communication channels to reach all levels of the organization and ensure that the message is understood and embraced.

- Inclusive Stakeholder Engagement: Involve stakeholders from all levels of the organization in the transition process (Choi et al., 2023) [55]. This inclusion helps in understanding their perspectives and addressing their concerns directly. Stakeholder engagement should be seen as an ongoing process, not just a one-time consultation.

- Leadership Support and Advocacy: Strong support and advocacy from the leadership are critical in overcoming resistance (Prabhu, 2017) [65]. Leaders should champion the transition, demonstrating commitment and setting an example for the rest of the organization. Their active involvement can inspire confidence and motivate others to embrace the change.

- Phased Implementation Approach: Implement the VDO in phases rather than all at once. A phased approach allows for gradual adaptation and provides opportunities to adjust the strategy based on feedback and initial outcomes. It also helps in managing the scale and complexity of the change (Grocholski, 2022) [66].

- Employee Empowerment and Participation: Empower employees by involving them in decision-making processes related to the transition (Gomez et al., 2015) [67]. Encourage their participation in VDO-related initiatives and provide opportunities for them to contribute ideas. This empowerment can foster a sense of ownership and reduce resistance.

- Training and Skill Development: Offer comprehensive training programs to develop the skills and knowledge required in a VDO environment. Focus on areas where employees might feel uncertain or unprepared. Effective training can alleviate fears and build confidence in the new system.

- Recognize and Address Cultural Barriers: Acknowledge and address any cultural barriers that might impede the transition. This includes adjusting organizational norms, values, and behaviors to align with the principles of a VDO. Creating a culture that is open to change is essential for overcoming resistance.

- Monitoring and Feedback Mechanisms: Establish mechanisms for monitoring the transition process and gathering feedback. Regularly assess progress, identify areas of resistance, and adjust strategies accordingly. Actively seeking and responding to feedback demonstrates a commitment to addressing concerns and improving the process.

5.10. Strategic Implications of Observed Improvements

5.11. Implementation Challenges and Industry-Specific Adaptations for VDMM

6. Limitations and Future Research Directions

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Bredillet, C.; Tywoniak, S.; Tootoonchy, M. Grasping the Dynamics of Co-Evolution Between PMO and PfM: A Box-Changing Multilevel Exploratory Research Grounded in a Routine Perspective. 2015. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/281653230 (accessed on 24 December 2024).

- Nejatyan, E.; Sarvari, H.; Hosseini, S.A.; Javanshir, H. Determining the Factors Influencing Construction Project Management Performance Improvement through Earned Value-Based Value Engineering Strategy: A Delphi-Based Survey. Buildings 2023, 13, 1964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ansari, R.; Shakeri, E.; Raddadi, A. Framework for Aligning Project Management with Organizational Strategies. J. Manag. Eng. 2015, 31, 04014050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nejatyan, E.; Sarvari, H.; Hosseini, S.A.; Javanshir, H. Deploying Value Engineering Strategies for Ameliorating Construction Project Management Performance: A Delphi-SWARA Study Approach. Buildings 2024, 14, 2291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarvari, H.; Chan, D.W.; Alaeos, A.K.; Olawumi, T.O.; Aldaud, A.A. Critical success factors for managing construction small and medium-sized enterprises in developing countries of Middle East: Evidence from Iranian construction enterprises. J. Build. Eng. 2021, 43, 103152. [Google Scholar]

- Sarvari, H.; Asaadsamani, P.; Olawumi, T.O.; Chan, D.W.; Rashidi, A.; Beer, M. Perceived barriers to implementing building information modeling in Iranian Small and Medium-Sized Enterprises (SMEs): A Delphi survey of construction experts. Archit. Eng. Des. Manag. 2024, 20, 673–693. [Google Scholar]

- Gheni Hussien, I.; Saeed Rasheed, Z.; Asaadsamani, P.; Sarvari, H. Perceived Critical Success Factors for Implementing Building Information Modelling in Construction Small-and Medium-Sized Enterprises. CivilEng 2025, 6, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plantinga, H.; Voordijk, H.; Dorée, A. Clarifying strategic alignment in the public procurement process. Int. J. Public Sect. Manag. 2020, 33, 791–807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salameh, H. A Framework to Establish a Project Management Office. In European Journal of Business and Management www.iiste.org ISSN (Vol. 6, Issue 9). 2014. Available online: https://www.iiste.org (accessed on 2 December 2024).

- Golestanizadeh, M.; Sarvari, H.; Cristofaro, M.; Chan, D.W. Effect of applying business intelligence on export development and brand internationalization in large industrial firms. Adm. Sci. 2023, 13, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Blooshi, K.; Mohammed, H.; Al Awadhi, K.Y.; Carreiras, P.; Al Mansoori, M.H.; Al Ameri, W.; Al Houqani, M.S.; ALwedami, A.; Saleh, R.H.; Alsaeedi, A.A.; et al. Transformation Management Office as a Vehicle to Accelerate Digital Transformation. In Proceedings of the Abu Dhabi International Petroleum Exhibition and Conference, Abu Dhabi, United Arab Emirates, 15–18 November 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riis, E.; Hellström, M.M.; Wikström, K. Governance of Projects: Generating value by linking projects with their permanent organization. Int. J. Proj. Manag. 2019, 37, 652–667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Project Management Institute. A Guide to the Project Management Body of Knowledge (PMBOK® Guide)–Seventh Edition and the Standard for Project Management; Project Management Institute: Pennsylvania, PA, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Alshehri, A. Value Management Practices in Construction Industry: An Analytical Review. Open Civ. Eng. J. 2020, 14, 10–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malvik, T.O.; Johansen, A.; Torp, O.; Olsson, N.O.E. Evaluation of Target Value Delivery and Opportunity Management as Complementary Practices. Sustainability 2021, 13, 7997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khalife, S.; Emadi, S.; Wilner, D.; Hamzeh, F. Developing Project Value Attributes: A Proposed Process for Value Delivery on Construction Projects. In Proceedings of the 30th Annual Conference of the International Group for Lean Construction, IGLC 2022, Edmonton, AB, Canada, 25–31 July 2022; pp. 913–924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karasu, T.; Aaltonen, K.; Haapasalo, H. The interplay of IPD and BIM: A systematic literature review. Constr. Innov. 2023, 23, 640–664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, D.W.; Sarvari, H.; Golestanizadeh, M.; Saka, A. Evaluating the impact of organizational learning on organizational performance through organizational innovation as a mediating variable: Evidence from Iranian construction companies. Int. J. Constr. Manag. 2024, 24, 921–934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, C.X.; Wells, W.G. An exploration of project management office features and their relationship to project performance. Int. J. Proj. Manag. 2004, 22, 523–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monteiro, A.; Santos, V.; Varajão, J. Project Management Office Models—A Review. Procedia Comput. Sci. 2016, 100, 1085–1094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, R.; Keil, M.; Kasi, V. Identifying and overcoming the challenges of implementing a project management office. Eur. J. Inf. Syst. 2009, 18, 409–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Izmailov, A.; Korneva, D.; Kozhemiakin, A. Effective Project Management with Theory of Constraints. Procedia Soc. Behav. Sci. 2016, 229, 96–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Otra-Aho, V.; Arndt, C.; Bergman, J.; Hallikas, J.; Kaaja, J. Impact of the PMOs’ Roles on Project Performance. Int. J. Inf. Technol. Proj. Manag. 2018, 9, 41–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fey, S.; Kock, A. Meeting challenges with resilience—How innovation projects deal with adversity. Int. J. Proj. Manag. 2022, 40, 941–950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Müller, R.; Glückler, J.; Aubry, M. A relational typology of project management offices. Proj. Manag. J. 2013, 44, 59–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, N.L.; Pearson, J.M.; Furumo, K. Is Project Management: Size, Practices and the Project Management Office. J. Comput. Inf. Syst. 2007, 47, 52–60. [Google Scholar]

- Augustine, S.; Cuellar, R.; Scheere, A. From PMO to VMO_ Managing for Value Delivery; Berrett-Koehler Publishers: San Francisco, CA, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Brady, T.; Davies, A. Building project capabilities: From exploratory to exploitative learning. Organ. Stud. 2004, 25, 1601–1621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKay, J.; Marshall, P.; Arumugam, S.; Grainger, N. Setting a research agenda for IT Project Management Offices. In Proceedings of the Annual Hawaii International Conference on System Sciences, Wailea, HI, USA, 7–10 January 2013; pp. 4364–4373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Golestanizadeh, M.; Sarvari, H.; Chan, D.W.; Banaitienė, N.; Banaitis, A. Managerial opportunities in application of business intelligence in construction companies. J. Civ. Eng. Manag. 2023, 29, 487–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aubry, M.; Müller, R.; Hobbs, B.; Blomquist, T. Project management offices in transition. Int. J. Proj. Manag. 2010, 28, 766–778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tillmann, P.A.; Eckblad, S.; Whitney, F.; Koefoed, N. Rethinking Project Delivery to Focus on Value and Innovation in the Public Sector. In Proceedings of the 30th Annual Conference of the International Group for Lean Construction, IGLC 2022, Edmonton, AB, Canada, 25–31 July 2022; pp. 107–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sefton, L.; Tierney, L. Pay-for-Performance in the Massachusetts Medicaid Delivery System Transformation Initiative. J. Healthc. Qual. 2023, 45, 38–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Klotz, L.E.; Horman, M.; Bodenschatz, M. A lean modeling protocol for evaluating green project delivery. Lean Constr. J. 2007, 3. [Google Scholar]

- Matinheikki, J.; Artto, K.; Peltokorpi, A.; Rajala, R. Value Creation in the Project Front-End Through Managing the Development of a Multi-Organizational Network; University of Edinburgh: Edinburgh, UK, 2015; Available online: https://research.aalto.fi/en/publications/value-creation-in-the-project-front-end-through-managing-the-deve (accessed on 20 November 2024).

- Babaei, A.; Locatelli, G.; Sainati, T. Local community engagement as a practice: An investigation of local community engagement issues and their impact on transport megaprojects’ social value. Int. J. Manag. Proj. Bus. 2023, 16, 448–474. [Google Scholar]

- Lukito, R.; Christian Efrata, T.; Padmawidjaja, L.; Radianto, W.E.D. The Impact of Perceived Quality and Perceived Value On Customer Satisfaction and Loyalty. Glob. Conf. Bus. Soc. Sci. Proceeding 2022, 14, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osaghae, E.; Olatunji, O.A. Key drivers of value amongst multicultural teams in construction projects. Int. J. Constr. Manag. 2023, 38, 1581–1588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asiedu, R.; Iddris, F. Value Co-Creation Approach to Management of Construction Project Stakeholders. J. Constr. Dev. Ctries. 2022, 27, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toljaga-Nikolić, D.; Obradović, V.; Todorović, M. The Role of Sustainable Project Management in Value co-Creation. Value Co-Creat. Proj. Soc. 2022, 53–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tvedt, I.M.; Tommelein, I.D.; Klakegg, O.J.; Wong, J.M. Organizational values in support of leadership styles fostering organizational resilience: A process perspective. Int. J. Manag. Proj. Bus. 2023, 16, 258–278. [Google Scholar]

- Sádaba, S.M.; Pérez-Ezcurdia, A.; Testorelli, R.; Moreno-Monsalve, N.; Delgado-Ortiz, M.; Rueda-Varón, M.; Fajardo-Moreno, W.S. Sustainable Development and Value Creation, an Approach from the Perspective of Project Management. Sustainability 2022, 15, 472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sage, D.; Dainty, A.; Brookes, N. A critical argument in favor of theoretical pluralism: Project failure and the many and varied limitations of project management. Int. J. Proj. Manag. 2014, 32, 544–555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salwan, P.; Patankar, A.; Shandilya, B.; Iyengar, S.; Thakur, M.S. The interplay of knowledge management, operational and dynamic capabilities in project phases. VINE J. Inf. Knowl. Manag. Syst. 2023, 53, 923–940. [Google Scholar]

- Bhattacharjee, B.; Seetharaman, A.; Maddulety, K. Scaling Agile P3O-VMO for Banking—Global Capability Centre. In Proceedings of the CONECCT 2023—9th International Conference on Electronics, Computing and Communication Technologies, Bangalore, India, 14–16 July 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ebbesen, J.B.; Hope, A. Re-imagining the Iron Triangle: Embedding Sustainability into Project Constraints. PM World J. 2013, 2, 1–13. [Google Scholar]

- Richard, E.E.; Davis, J.R.; Paik, J.H.; Lakhani, K.R. Sustaining open innovation through a “Center of Excellence”. Strategy Leadersh. 2019, 47, 19–26. [Google Scholar]

- Vartiak, L.; Jankalova, M. The business excellence assessment. Procedia Eng. 2017, 192, 917–922. [Google Scholar]

- Zare Khafri, A.; Sheikh Aboumasoudi, A.; Khademolqorani, S. The Effect of Innovation on the Company’s Performance in Small and Medium-Sized Businesses with the Mediating Role of Lean: Agile Project Management Office (LAPMO). Complexity. 2023, 2023, 4820636. [Google Scholar]

- Cesarotti, V.; Gubinelli, S.; Introna, V. The evolution of Project Management (PM): How Agile, Lean and Six Sigma are changing PM. J. Mod. Proj. Manag. 2019, 7, 162–189. [Google Scholar]

- Oke, A.E. Project Value: A Measure of Project Success. In Measures of Sustainable Construction Projects Performance; Emerald Publishing Limited: Leeds, UK, 2022; pp. 61–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gordon, A.; Pollack, J. Managing healthcare integration: Adapting project management to the needs of organizational change. Proj. Manag. J. 2018, 49, 5–21. [Google Scholar]

- Alnuaimi, A.; Joslin, R. Analysing the Impact of PMO Culture on PMO Success. In Proceedings of the 10th IPMA Research Conference “Value Co-Creation in the Project Society”, Belgrade, Serbia, 19–21 June 2022; pp. 278–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Budayan, C.; Dikmen, I.; Birgonul, M.T. Alignment of project management with business strategy in construction: Evidence from the Turkish contractors. J. Civ. Eng. Manag. 2015, 21, 94–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, Y.; Pessoa, M.V.P.; Bonnema, G.M. Perspectives on Modeling Energy and Mobility Transitions for Stakeholders: A Dutch Case. World Electr. Veh. J. 2023, 14, 178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muzalev, S.; Shnaider, V.; Vasilchuk, O.; Pimenov, D. Possibilities of using the stakeholder approach in the implementation of reactive control. In Proceedings of the AIP Conference Proceedings, Albuquerque, NM, USA, 14 September 2022; Volume 2636. [Google Scholar]

- Khalife, S.; Hamzeh, F. How to navigate the dilemma of value delivery: A value identification game. In Proceedings of the 31st Annual Conference of the International Group for Lean Construction (IGLC31), Lille, France, 26 June–2 July 2023; pp. 663–673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, V.; Kruger, N. The value architecture framework for success of ICT type projects. In Proceedings of the ICISDM ‘17: Proceedings of the 2017 International Conference on Information System and Data Mining, Charleston, SC, USA, 1–3 April 2017; pp. 88–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cha, H.S.; O’Connor, J.T. Optimizing Implementation of Value Management Processes for Capital Projects. J. Constr. Eng. Manag. 2005, 131, 239–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almatrodi, I.M. The Power/Knowledge of Consultants and Project Management Office in Enterprise System Implementation: A Case Study of a Saudi Arabian University. Ph.D. Thesis, University of East Anglia, Norwich, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Samanta, U.; Mani, V.S. Successfully Transforming to Lean by Changing the Mindset in a Global Product Development Team. In Proceedings of the IEEE 10th International Conference on Global Software Engineering, ICGSE 2015, Ciudad Real, Spain, 13–16 July 2015; pp. 135–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Križaić, V. System adjustments through vector organization and technology. In Proceedings of the InCreative Construction Conference, Budapest, Hungary, 29 June–2 July 2019; pp. 440–445. [Google Scholar]

- Kendall & Rollins. Advanced Project Portfolio Management and the PMO: Multiplying ROI at Warp Speed. 2003. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/237497431_Advanced_Project_Portfolio_Management_and_the_PMO_Multiplying_ROI_at_Warp_Speed (accessed on 8 February 2025).

- Sexton, S. The Use of Organisational Communication to Facilitate the Implementation of Change by Reducing Employee Resistance. Bachelor’s Thesis, National College of Ireland, Dublin, Ireland, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Prabhu, U. Overcoming resistance to change: A personal perspective. Why Hosp. Fail. Between Theory Pract. 2017, 123–128. [Google Scholar]

- Grocholski, E. The relevance of agile change management in a dynamic business environment. Sci. Int. Empir. Rev. 2022, 1, 169–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomez, B.; Ba, M.; William, E.; Rohrer, G. Understanding leadership and empowerment in the workplace. Eur. Sci. J. 2015, 11, 342–365. [Google Scholar]

| Research Objective | Research Question(s) | Corresponding Method(s) |

|---|---|---|

| 1. Identify and analyze the limitations of traditional PMOs. | What are the main limitations of traditional PMOs in contemporary project environments? | Literature Review, Qualitative Interviews |

| 2. Explore the concept and operational framework of VDOs. | What constitutes the Value Delivery Office (VDO) framework, and how does it differ from the PMO model? | Literature Review, Qualitative Interviews, Case Studies |

| 3. Examine the role of VDOs in enhancing value creation and delivery within organizations. | How do VDOs contribute to enhanced value creation and strategic alignment within organizations? | Qualitative Interviews, Quantitative Surveys, Case Studies |

| 4. Provide empirical evidence illustrating the transition from PMOs to VDOs. | What are the practical experiences, successes, and challenges organizations face when transitioning from PMOs to VDOs? | Case Studies, Qualitative Interviews |

| 5. Offer actionable insights and recommendations for transitioning to a VDO framework. | What practical strategies and recommendations can organizations implement when transitioning from PMOs to VDOs? | Mixed-methods analysis (Synthesis of Interviews, Surveys, and Case Studies) |

| Value Type | Description |

|---|---|

| Economic | Focuses on the monetary aspects of value, such as cost-benefit analysis, ROI, and financial gains. |

| Functional | Relates to the practical and utilitarian benefits of a product or service, like usability and efficiency. |

| Social | Encompasses the social aspects of value, including community benefits, social responsibility, and reputation. |

| Perceived | Involves the customer’s or stakeholder’s perception of value, which can influence their decision-making and satisfaction. |

| Cultural | Pertains to value derived from cultural significance, heritage, or alignment with cultural norms and values. |

| Personal | Refers to individual personal preferences, experiences, and emotional connections that create value. |

| Strategic | Involves long-term planning and strategic benefits that align with organizational goals and objectives. |

| Intrinsic | Relates to the inherent or self-evident value of something, often tied to ethical, moral, or philosophical beliefs. |

| Sustainable | Balances economic success with environmental and social responsibility, aiming for long-term benefits and positive societal impact. |

| Change Management Strategies | Impact on VDOs | Examples/Evidence |

|---|---|---|

| Stakeholder Engagement | Enhances buy-in and support for VDO initiatives | Case study of a tech company’s VDO rollout |

| Communication Planning | Facilitates clearer understanding of VDO objectives | Survey results showing improved alignment |

| Training and Development | Builds capability for VDO-related tasks and roles | Implementation of VDO training programs |

| Resistance Management | Reduces barriers to change and promotes adaptability | Example of handling change resistance |

| Feedback and Continuous Improvement | Allows for refinement of VDO processes and strategies | Feedback loop incorporated into VDO process |

| Stage | Description | Key Characteristics | Examples |

|---|---|---|---|

| Initiation | Early development of VDO | Ad-hoc practices, low integration with business strategy | Small startup with informal VDO |

| Inspiration | Structuring of VDO processes | Formalizing procedures, increasing awareness and engagement | Growing business establishing VDO |

| Ideation | Established VDO framework | Clear roles and responsibilities, alignment with strategy | Established company with defined VDO roles |

| Implementation | Advanced VDO implementation | Performance metrics, continuous improvement processes in place | Large corporation with performance tracking for VDO |

| Optimization | Continuous refinement and adaptation | Proactive value creation, strategic innovation through VDO | Industry-leading firms with adaptive VDO strategies |

| Implication for Organizations | Strategies/Recommendations |

|---|---|

| Need for Cultural Change | Develop a change management plan; promote a culture of innovation and agility. |

| Enhanced Stakeholder Engagement | Implement stakeholder mapping and regular communication channels. |

| Requirement for Skilled Personnel | Invest in training programs; recruit or develop talent with VDO-specific skills. |

| Integration of Technology | Adopt technology platforms that support VDO operations and reporting. |

| Alignment with Business Strategy | Ensure VDO objectives are aligned with the overall business strategy. |

| Managing Organizational Resistance | Develop a comprehensive plan to address and mitigate resistance to change. |

| Continuous Improvement and Adaptation | Establish mechanisms for ongoing feedback, learning, and adaptation. |

| Measuring and Reporting Value Delivery | Define clear metrics for value delivery and establish regular reporting processes. |

| Continuous Improvement and Adaptation | Establish mechanisms for ongoing feedback, learning, and adaptation. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Moghaddasi, S.; Kordani, K.; Sarvari, H.; Rashidi, A. Redefining Project Management: Embracing Value Delivery Offices for Enhanced Organizational Performance. Buildings 2025, 15, 1176. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15071176

Moghaddasi S, Kordani K, Sarvari H, Rashidi A. Redefining Project Management: Embracing Value Delivery Offices for Enhanced Organizational Performance. Buildings. 2025; 15(7):1176. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15071176

Chicago/Turabian StyleMoghaddasi, Saeed, Kambiz Kordani, Hadi Sarvari, and Amirreza Rashidi. 2025. "Redefining Project Management: Embracing Value Delivery Offices for Enhanced Organizational Performance" Buildings 15, no. 7: 1176. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15071176

APA StyleMoghaddasi, S., Kordani, K., Sarvari, H., & Rashidi, A. (2025). Redefining Project Management: Embracing Value Delivery Offices for Enhanced Organizational Performance. Buildings, 15(7), 1176. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15071176