Towards an Enhanced Business Case Development for Public–Private Partnership (PPP) Projects: A Comparative Study of China and New Zealand

Abstract

1. Introduction

- What are the factors that are critical to the success of the PPP business case?

- Based on the critical factors identified, what are the useful and workable policies and management interventions for enhanced business case development processes?

2. Literature Review

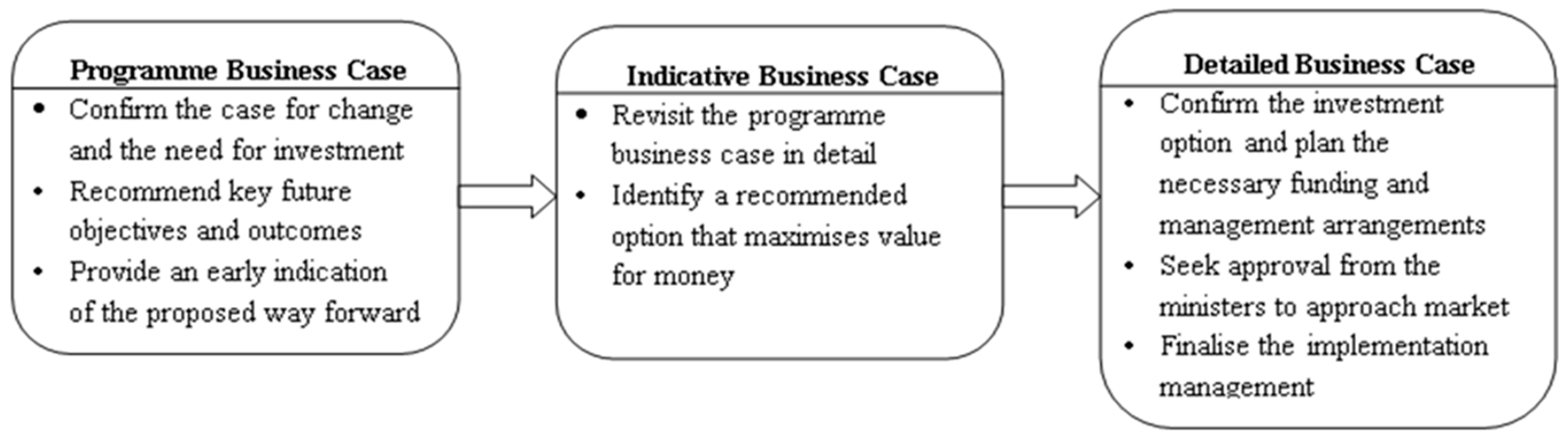

2.1. PPP Business Case Development Stage

2.2. Critical Factors Affecting the Successful Development of PPP Business Case

2.3. PPP Practices and Policies

2.3.1. PPPs in China

2.3.2. PPPs in New Zealand

3. Research Methods

4. Results and Discussion

4.1. Contextual Factors

4.1.1. Political Champion

The government tends to use strong administrative power, rather than a rigorous business case framework to push PPP forward. Lacking a systematic thinking, the sustainability of China’s PPPs remains a question mark.

Decisions in infrastructure take long time to make. You can have change of politicians during the decision-Making process. That creates some problems. The market did reflect a level of nervousness that due to change of political power, contracting arrangements changed as a result.

4.1.2. Enabling Legal and Regulatory Frameworks

The provisions are sometimes contradictory to each other. Different sectors have varied approaches and procedures. Local governments even have their own requirements. This brings about lots of confusions to the market. When inconsistencies occur, how to interpret the priorities of relevant provisions?

4.2. Procedural Factors

4.2.1. Sound Service Need Analysis

It is common to see the construction of a project has commenced whilst the service need not being adequately confirmed. It also happens to PPP projects. Some local governments just want to get a PPP built without asking: “Do we really need it? Whether the option is cost effective”.

4.2.2. Robust Procurement Option Analysis

The “surname” of Public-Private Partnerships is “Public”. The goal of PPPs is to achieve benefits for general public. You build a characteristic town PPP project. Will the local community gain better access to facilities? Will they have more job opportunities? Will their well-beings improve due to the town’s development?

At the current stage, we shall at least have a comparison so that our decisions-making can be grounded in reasons. We can mainly adopt a qualitative method, assisted with the PSC. It is a progressive process from a general appraisal to a systematic and comprehensive evaluation. It is a balance we are seeking.

The long-term nature of the contract means that they (the private sector) have an opportunity to earn revenues that can be used to offset project costs. Say you have a school PPP. They might build a recreational center open to the public to generate more revenue, and at the same time, the facilities will be fully utilized, and the adjacent communities also benefit.

4.2.3. Articulated Affordability Analysis

Compared to traditional procurement, the affordability of PPPs is about cost of finance and efficiency differentials. The current capital asset management guidance and practices require care for affordability. If analysis shows PPPs are unaffordable, possible remedies like adopting a different design can help to close the gap.

4.3. Capability-Related Factors

4.3.1. Strong Public Sector Capability

In terms of providing output specification, it is very difficult with [the public sector] have been used to. They are happy with the concept of it but find it very hard to do in practice. How to specify the outcomes through setting up a series of KPIs?

Some consultancy firms’ areas of expertise are not in PPPs. They know PPPs are very popular and decide to transform their business. Some of them learn the basics about PPPs and go ahead working on projects. I highly doubt the quality of their professional services.

4.3.2. Public Sector Commitment and Credibility

When we initiate a PPP program, it is crucial that we adhere consistently to our stated intentions. Any commitments made during the market sounding process must be rigorously upheld. If we deviate from these promises or demonstrate uncertainty, it creates anxiety within the market and undermines stakeholder confidence.

We indicate to people at the time we are going to detailed business case. That is prior to being approved as a PPP. The market knows that we are undertaking a serious investigation as opposed to a preliminary one. We are careful with what we publicize so people don’t have to run around.

As a construction contractor, we frequently experience frustrations in our dealings with public sector clients. They often lack what we refer to as the ‘contract spirit’, meaning commitments outlined in contracts are not consistently respected. When disputes arise, we encounter considerable obstacles; we cannot even pursue legal action effectively, since, under current Civil Law, these public sector bodies are often not recognized as fully accountable legal entities.

4.4. Organisational Factors

4.4.1. Streamlined Institutional Arrangements

PPPs would be difficult where there are many local boards involved in the decision making, such as the current practices with the education sector. The Ministry of Education is responsible for the provision of school assets. But the school boards take charge of the maintenance based on its annual maintenance fund. The fragmentation of procuring power makes it difficult to take a whole of life perspective towards capital asset delivery.

In the health sector, we’ve got multiple DHBs (District Health Boards). When it comes to PPPs, we need centralized power to make decisions, rather than many DHBs as we’ve got.

4.4.2. Effective Governance Structures

The project steering committee was formulated at the outset. They meet monthly. The core project team meet every week. Any existing or potential barriers can be addressed in time. The Treasury PPP team holds their [the project team] hands to make sure they are on the right track.

4.5. Comparative Analysis and Recommendations

5. Conclusions

5.1. Implications

5.2. Limitations and Future Research

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- New Zealand Infrastructure Commissions. The New Zealand PPP Framework: A Blueprint for Future Transactions. Available online: https://tewaihanga.govt.nz/our-work/project-support/guidance/public-private-partnerships-ppps (accessed on 1 December 2024).

- Department of Infrastructure and Regional Development. National Public Private Partnership Policy Framework. Available online: https://www.infrastructure.gov.au/sites/default/files/migrated/infrastructure/ngpd/files/National-PPP-Policy-Framework-Oct-2015.pdf (accessed on 15 November 2024).

- Tang, L.Y.; Shen, G.Q.P.; Skitmore, M.; Wang, H. Procurement-Related Critical Factors for Briefing in Public-Private Partnership Projects: Case of Hong Kong. J. Manag. Eng. 2015, 31, 04014096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, C.A.; Flanagan, J. Making Sense of Public Sector Investments: The ’five-case Model’ in Decision Making; Radcliffe Medical: Radcliffe, UK, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Tang, L.; Shen, Q.; Skitmore, M.; Cheng, E.W. Ranked critical factors in PPP briefings. J. Manag. Eng. 2012, 29, 164–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, L.; Zhang, L. An analysis of the application and feasibility of BOT financing mode in Hangzhou—A case study of Hangzhou Bay Bridge. Mod. Bus. Trade Ind. 2009, 21, 83–85. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Robinson, H.; Carillo, P.; Anumba, C.; Patel, M. Governance and Knowledge Management for Public-Private Partnerships; Wiley-Blackwell: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, J.X.; Love, P.E.D.; Smith, J.; Regan, M.; Davis, P.R. Life Cycle Critical Success Factors for Public-Private Partnership Infrastructure Projects. J. Manag. Eng. 2015, 31, 3–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rockart, J.F. The changing role of the information systems executive: A critical success factors perspective. Sloan Manag. Rev. 1982, 24, 3–13. [Google Scholar]

- Chileshe, N.; Njau, C.W.; Kibichii, B.K.; Macharia, L.N.; Kavishe, N. Critical success factors for Public-Private Partnership (PPP) infrastructure and housing projects in Kenya. Int. J. Constr. Manag. 2022, 22, 1606–1617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Debela, G.Y. Critical success factors (CSFs) of public–private partnership (PPP) road projects in Ethiopia. Int. J. Constr. Manag. 2022, 22, 489–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osei-Kyei, R.; Chan, A.P. Review of studies on the Critical Success Factors for Public–Private Partnership (PPP) projects from 1990 to 2013. Int. J. Proj. Manag. 2015, 33, 1335–1346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ng, S.T.; Wong, Y.M.; Wong, J.M. Factors influencing the success of PPP at feasibility stage—A tripartite comparison study in Hong Kong. Habitat Int. 2012, 36, 423–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, L.; Shen, Q.; Cheng, E.W.L. A review of studies on Public-Private Partnership projects in the construction industry. Int. J. Proj. Manag. 2009, 28, 683–694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raisbeck, P.; Tang, L.C. Identifying design development factors in Australian PPP projects using an AHP framework. Constr. Manag. Econ. 2013, 31, 20–39. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, T.T.; Wang, Y.; Wilkinson, S. Identifying critical factors affecting the effectiveness and efficiency of tendering processes in Public-Private Partnerships (PPPs): A comparative analysis of Australia and China. Int. J. Proj. Manag. 2016, 34, 701–716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robinson, H.S.; Scott, J. Service delivery and performance monitoring in PFI/PPP projects. Constr. Manag. Econ. 2009, 27, 181–197. [Google Scholar]

- Chou, J.S.; Leatemia, G.T. Critical Process and Factors for Ex-Post Evaluation of Public-Private Partnership Infrastructure Projects in Indonesia. J. Manag. Eng. 2016, 32, 05016011. [Google Scholar]

- Association for Project Management. What Is a Business Case? Available online: https://www.apm.org.uk/resources/what-is-project-management/what-is-a-business-case/ (accessed on 15 November 2024).

- Herman, B.; Siegelaub, J.M. Is this really worth the effort? The need for a business case. In Proceedings of the PMI® Global Congress 2009—North America, Orlando, FL, USA, 10–13 October 2009; Project Management Institute: Newtown Square, PA, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- The New Zealand Treasury—2011a—Better Business Cases for Capital Proposals: Quick Reference Guide; National Infrastructure Unit: Wellington, UK, 2011.

- Flanagan, J.; Nicholls, P. Public Sector Business Cases Using the Five Case Model: A Toolkit; HM Treasury: London, UK, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- The New Zealand Treasury. The New Zealand Treasury—2011b—Better Business Cases for Capital Proposals Toolkit: Detailed Business Case; The New Zealand Treasury: Wellington, New Zealand, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- The New Zealand Treasury. The New Zealand Treasury—2011c—Better Business Cases for Capital Proposals Toolkit: Indicative Business Case; The New Zealand Treasury: Wellington, New Zealand, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- The New Zealand Treasury. The New Zealand Treasury—2011d—Better Business Cases for Capital Proposals Toolkit: Programme Business Case; The New Zealand Treasury: Wellington, New Zealand, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- The New Zealand Treasury. The New Zealand Treasury—2015—Public Private Partnership Programme: The PPP Procurement Process: A Guide for Public Sector Entities; The New Zealand Treasury: Wellington, New Zealand, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Garvin, M.J. Enabling development of the transportation public-private partnership market in the United States. J. Constr. Eng. Manag. 2010, 136, 402–411. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, T.T.; Wilkinson, S. Critical Factors Affecting the Viability of Using Public-Private Partnerships for Prison Development. J. Manag. Eng. 2015, 31, 05014020. [Google Scholar]

- Van de Hurk, M.; Hueskes, M. Beyond the financial logic: Realizing valuable outcomes in public-private partnerships in Flanders and Ontario. Environ. Plan. C Politics Space 2017, 35, 784–808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hueskes, M.; Verhoest, K.; Block, T. Governing public-private partnerships for sustainability: An analysis of procurement and governance practices of PPP infrastructure Projects. Int. J. Proj. Manag. 2017, 35, 1184–1195. [Google Scholar]

- Carrillo, P.; Robinson, H.; Foale, P.; Anumba, C.; Bouchlaghem, D. Participation, barriers, and opportunities in PFI: The United Kingdom experience. J. Manag. Eng. 2008, 24, 138–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, A.P.C.; Lam, P.T.I.; Chan, D.W.M.; Cheung, E.; Ke, Y. Potential obstacles to successful implementation of public-private partnerships in Beijing and the Hong Kong special administrative region. J. Manag. Eng. 2010, 26, 30–40. [Google Scholar]

- Chou, J.S.; Pramudawardhani, D. Cross-country comparisons of key drivers, critical success factors and risk allocation for public-private partnership projects. Int. J. Proj. Manag. 2015, 33, 1136–1150. [Google Scholar]

- Dabarera, G.K.M.; Perera, B.A.K.S.; Rodrigo, M.N.N. Suitability of public-private-partnership procurement method for road projects in Sri Lanka. Built Environ. Proj. Asset Manag. 2019, 9, 199–213. [Google Scholar]

- Agarchand, N.; Laishram, B. Sustainable infrastructure development challenges through PPP procurement process: Indian perspective. Int. J. Manag. Proj. Bus. 2017, 10, 642–662. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, X.; Han, J. Highway project value of money assessment under PPP mode and its application. J. Adv. Transp. 2018, 2018, 1802671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsukada, S. Adoption of shadow bid pricing for enhanced application of “value for money” methodology to PPP programs. Public Work. Manag. Policy 2015, 20, 248–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, Z.; Ke, Y.; Lin, J.; Yang, Z.; Cai, J. Spatio-temporal dynamics of public private partnership projects in China. Int. J. Proj. Manag. 2016, 34, 1242–1251. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Y.; Xu, E.; Zhang, Z.; He, S.; Jiang, X.; Skitmore, M. Why Are PPP Projects Stagnating in China? An Evolutionary Analysis of China’s PPP Policies. Buildings 2024, 14, 1160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, C.-Y.; Chen, S. Transitional Public-Private Partnership Model in China: Contracting with Little Recourse to Contracts. J. Constr. Eng. Manag. 2016, 142, 05016011. [Google Scholar]

- Meng, X.; Zhao, Q.; Shen, Q. Critical success factors for transfer-operate-transfer urban water supply projects in China. J. Manag. Eng. 2011, 27, 243–251. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, T.T.; Shi, C.Y. Barriers to Knowledge Transfer in Public-Private Partnership (PPP) Projects. Proj. Manag. Technol. 2016, 14, 25–28. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- He, J.W.; Liu, T.T. Critical Factors Affecting the Dispute Negotiation in Public-Private Partnership (PPP) Projects. J. Civ. Eng. Manag. 2017, 34, 125–131. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- National Development and Reform Commission—2015—Measures for the Administration of Concession for Infrastructure and Public Utilities. Available online: https://faolex.fao.org/docs/pdf/chn189775.pdf (accessed on 25 November 2024). (In Chinese).

- Wu, J.; Liu, J.X.; Jin, X.H.; Sing, M.C.P. Government accountability within infrastructure public-private partnerships. Int. J. Proj. Manag. 2016, 34, 1471–1478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomczak, M. Public-Private Partnerships and the Development of Public Assembly Facilities, with Particular Consideration of the Private Sector: The Vector Arena in Auckland City; Research project (MPlan), University of Auckland: Auckland, New Zealand, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, T.; Wilkinson, S. Using public-private partnerships for the building and management of school assets and services. Eng. Constr. Archit. Manag. 2014, 21, 206–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bloomberg, L.; Volpe, M. Completing Your Qualitative Dissertation: A Roadmap from Beginning to End; Sage Publications: Los Angeles, CA, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Hancock, B. An Introduction to Qualitative Research; University of Nottingham: Nottingham, UK, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Amaratunga, D.; Baldry, D.; Sarshar, M.; Newton, R. Quantitative and qualitative research in the built environment: Application of “mixed” research approach. Work Study 2002, 51, 17–31. [Google Scholar]

- Denzin, N.K.; Lincoln, Y.S. The Landscape of Qualitative Research; Sage Publications: Los Angeles, CA, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Jamali, D. Success and failure mechanisms of public private partnerships (PPPs) in developing countries: Insights from the Lebanese context. Int. J. Public Sect. Manag. 2004, 17, 414–430. [Google Scholar]

- Abdel Aziz, A.M. Successful Delivery of Public-Private Partnerships for Infrastructure Development. J. Constr. Eng. Manag. 2007, 133, 918–931. [Google Scholar]

- Jefferies, M.; Gameson, R.; Rowlinson, S. Critical success factors of the BOOT procurement system: Reflections from the Stadium Australia case study. Eng. Constr. Archit. Manag. 2002, 9, 352–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, B.; Akintoye, A.; Edwards, P.J.; Hardcastle, C. Critical success factors for PPP/PFI projects in the UK construction industry. Constr. Manag. Econ. 2005, 23, 459–471. [Google Scholar]

- Dulaimi, M.F.; Alhashemi, M.; Ling, F.Y.Y.; Kumaraswamy, M. The execution of public-private partnership projects in the UAE. Constr. Manag. Econ. 2010, 28, 393–402. [Google Scholar]

- Marques, R.C. Is arbitration the right way to settle conflicts in PPP arrangements? J. Manag. Eng. 2018, 34, 05017007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, J.; Hu, Y.; Feng, Z. Factors influencing early termination of PPP projects in China. J. Manag. Eng. 2018, 34, 05017008. [Google Scholar]

- Kweun, J.Y.; Wheeler, P.K.; Gifford, J.L. Evaluating highway public-private partnerships: Evidence from US value for money studies. Transp. Policy 2018, 62, 12–20. [Google Scholar]

- Vining, A.R.; Boardman, A.E. Public—Private partnerships: Eight rules for governments. Public Work. Manag. Policy 2008, 13, 149–161. [Google Scholar]

- Almarri, K.; Abu-Hijleh, B. Critical success factors for public private partnerships in the UAE construction industry—A comparative analysis between the UAE and the UK. J. Eng. Proj. Prod. Manag. 2017, 7, 21–32. [Google Scholar]

| Characteristic | Category | China | New Zealand | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | % | Interviewee Code | N | % | Interviewee Code | ||

| Role of organisation in PPPs | National coordinating authority | 1 | 4% | CN1 | 2 | 9% | NN1-NN2 |

| Central government department/agency | 2 | 8% | CG1-CG2 | 8 | 36% | NG1-NG8 | |

| Local government | 4 | 17% | CL1-CL4 | 3 | 14% | NL1-NL3 | |

| Construction contractor | 4 | 17% | CC1-CC4 | 2 | 9% | NC1-NC2 | |

| Operator/facility manager | 2 | 8% | CO1-CO2 | 1 | 5% | NO1 | |

| Financier | 4 | 17% | CF1-CF2 | 2 | 9% | NF1-NF2 | |

| Advisors (commercial/legal) | 3 | 12% | CA1-CA5 | 4 | 18% | NA1-NA4 | |

| Researchers | 4 | 17% | CR1-CR4 | ||||

| Designation | Upper management | 6 | 25% | 8 | 36% | ||

| Middle management | 8 | 33% | 10 | 46% | |||

| Professionals | 10 | 42% | 4 | 18% | |||

| Years of experience with PPPs | More than 15 years | 3 | 12% | 4 | 18% | ||

| 10–15 years | 8 | 33% | 6 | 27% | |||

| 5–10 years | 4 | 17% | 2 | 9% | |||

| Less than 5 years | 9 | 38% | 10 | 46% | |||

| Interview Questions | Discussion Areas or Probes | Purpose |

|---|---|---|

| Based on your work/research experience in relation to PPPs, how do you perceive the performance of business case development in PPP projects? [4,22] | A robust case for change that represents strategic synergy | To gain an understanding of the current practices of business case development in PPP projects |

| Optimised value for money | ||

| Commercial viability | ||

| Financial affordability | ||

| Management achievability | ||

| Costs and durations of business case development | ||

| What are the key issues/concerns encountered in the business case development of PPP projects? What are the initiatives taken to address the issues/concerns emerged? How would you evaluate their effectiveness? [18,32,52,53,54,55,56] | Political and social support | To identify critical factors influencing the successful development of business cases in PPP projects |

| Legal and regulatory frameworks | ||

| Service need | ||

| Value for money assessment | ||

| Public sector capacity and commitment | ||

| Governance Structures | ||

| Given the nature of your profession, could you identify additional strategies | Open-ended questions | To recommend policies and management interventions for an enhanced business case development process |

| Category | Critical Factor | Recommendations |

|---|---|---|

| Contextual factors | Political champion |

|

| Enabling legal and regulatory framework |

| |

| Procedural factors | Sound service need analysis |

|

| Robust procurement option analysis |

| |

| Articulated affordability analysis |

| |

| Public sector commitment and credibility |

| |

| Organisational factors | Streamlined institutional arrangements |

|

| Effective governance structures |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Liu, T.; Fong, P.S.W. Towards an Enhanced Business Case Development for Public–Private Partnership (PPP) Projects: A Comparative Study of China and New Zealand. Buildings 2025, 15, 1154. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15071154

Liu T, Fong PSW. Towards an Enhanced Business Case Development for Public–Private Partnership (PPP) Projects: A Comparative Study of China and New Zealand. Buildings. 2025; 15(7):1154. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15071154

Chicago/Turabian StyleLiu, Tingting, and Patrick S. W. Fong. 2025. "Towards an Enhanced Business Case Development for Public–Private Partnership (PPP) Projects: A Comparative Study of China and New Zealand" Buildings 15, no. 7: 1154. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15071154

APA StyleLiu, T., & Fong, P. S. W. (2025). Towards an Enhanced Business Case Development for Public–Private Partnership (PPP) Projects: A Comparative Study of China and New Zealand. Buildings, 15(7), 1154. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15071154